Abstract

Aims

Intracoronary administration of autologous bone marrow cells (BMCs) leads to a modest improvement in cardiac function, but the effect on myocardial viability is unknown. The aim of this randomized multicenter study was to evaluate the effect of BMC therapy on myocardial viability in patients with decreased left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) after acute myocardial infarction (AMI) and to identify predictive factors for improvement of myocardial viability.

Methods and Results

One-hundred one patients with AMI and successful reperfusion, LVEF ≤45%, and decreased myocardial viability (resting Tl201-SPECT) were randomized to either a control group (n=49) or a BMC group (n=52). Primary endpoint was improvement of myocardial viability 3 months after AMI. Baseline mean LVEF measured by radionuclide angiography was 36.3 ± 6.9%. BMC infusion was performed 9.3 ± 1.7 days after AMI. Myocardial viability improved in 16/47 (34%) patients in the BMC group compared to 7/43 (16%) in the control group (p = 0.06). The number of non-viable segments becoming viable was 0.8 ± 1.1 in the control group and 1.2 ± 1.5 in the BMC group (p = 0.13). Multivariate analysis including major post-AMI prognostic factors showed a significant improvement of myocardial viability in BMC vs. control group (p=0.03). Moreover, a significant adverse role for active smoking (p=0.04) and a positive trend for microvascular obstruction (p=0.07) were observed.

Conclusions

Intracoronary autologous BMC administration to patients with decreased LVEF after AMI was associated with improvement of myocardial viability in multivariate –but not in univariate – analysis. A large multicenter international trial is warranted to further document the efficacy of cardiac cell therapy and better define a group of patients that will benefit from this therapy.

Keywords: Myocardial infarction, Cells, Smoking

Introduction

More than 7 years ago, an initial report on the clinical application of mononucleated bone marrow-derived cells (BMCs) in patients with acute myocardial infarction (AMI) opened up a new era of regenerative cardiology and brought with it great enthusiasm[1].Since then, numerous clinical trials have been carried out with the aim of assessing the efficacy and safety of stem cell therapy. Improvement of left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) was shown in REPAIR-AMI study[2]but the benefit was transient in BOOST,[3,4]while other trials were unsuccessful[5–7].Although randomized trials reported mixed results, meta-analyses have shown a significant improvement in cardiac function assessed by LVEF after cell therapy[8].Some of the discrepancies between these large trials could be explained by differences in criteria for patient selection. There is some evidence to suggest that BMC-based therapy is more effective at improving LVEF after AMI in patients with decreased LVEF and in patients whose treatment is delayed at least 5 days after AMI[2,8].Lifestyle may also affect clinical outcome following cell therapy. Indeed, smoking habit is a major factor contributing to reduced number and function of circulating progenitor cells in patients with coronary artery disease[9].Most of clinical trials have focused on changes in ejection fraction to evaluate the efficiency of cell therapy. However, it has been shown that myocardial viability represents a reliable parameter for prediction of recovery of cardiac function after revascularization[10].We carried out a prospective randomized open label blinded endpoint evaluation (PROBE) study to assess the efficacy of mononucleated autologous BMC intracoronary injection in patients with AMI and low LVEF. Our primary objective was to evaluate the effect of BMC therapy on myocardial viability and to identify predictive factors for improvement of myocardial viability.

Methods

Patient selection

Patients admitted to the University Hospitals of Créteil, Grenoble, Lille, Montpellier, Nantes and Toulouse, between December 2004 and January 2007, with an ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) were screened for inclusion in the BONAMI trial. Screening criteria were: age 18–75 years, a successful percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) with bare metal stent implantation performed on the culprit lesion during the 24 h after the onset of symptoms, and LVEF <50% assessed by echocardiography. The main exclusion criteria are listed in Supplementary material online. The ethics review board of Nantes University Hospital approved the protocol, and the study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All subjects gave informed consent.

Study design and treatment randomization

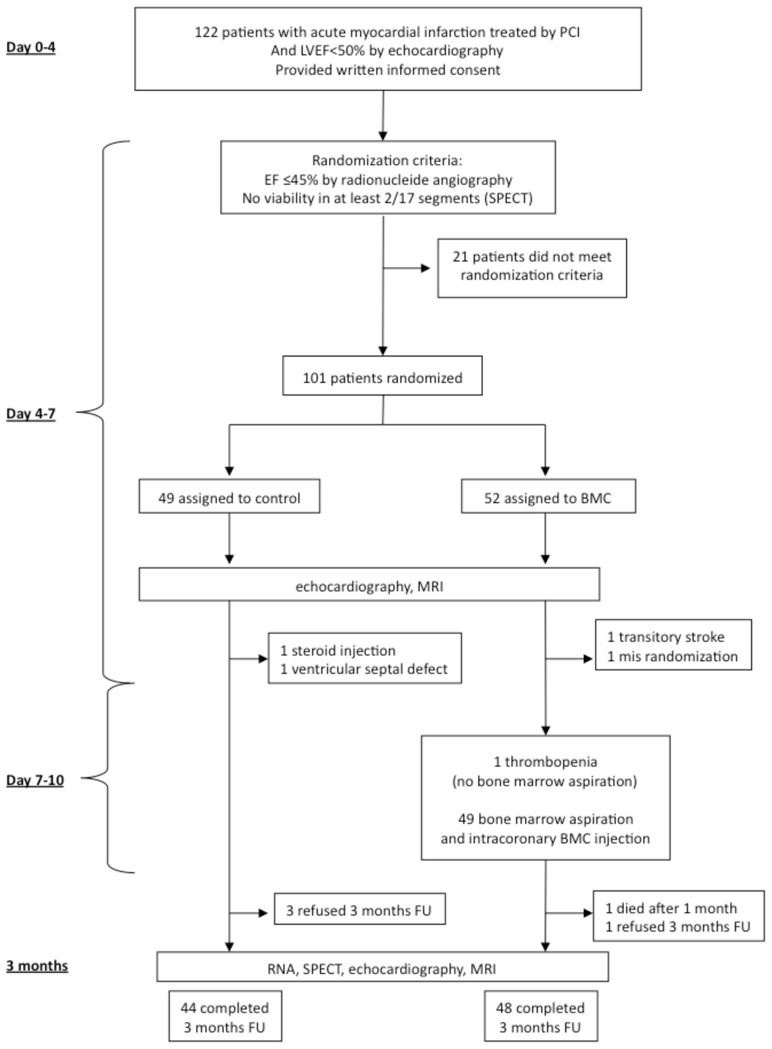

The study design is shown in Figure 1. Day 0 was defined as the day of occurrence of STEMI. Screened patients underwent radionuclide angiography (RNA) and resting 4 h thallium-201-gated-single-photon-emission computed tomography (SPECT) between day 1 and day 4. Randomization criteria were defined as follows: LVEF ≤45% assessed by RNA and absence of myocardial viability in at least 2/17 contiguous segments by SPECT. The Center of Clinical Research University Hospital Nantes provided consecutively numbered sealed envelopes for all participant centers. Patients were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to either the control group or BMC group using permuted-block randomization stratified according to center, diabetes status and time to PCI after the onset of AMI (≤12 or >12 h) on day 4–7. We used a stratified randomization model because diabetes is known to impact on BMC[11]and late reperfusion influences the prognosis after AMI. In addition, baseline echocardiography and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) were performed on day 4–7 in both groups.

Figure 1.

Patient enrolment and outcomes.

PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction; SPECT: single-photon-emission computed tomography; RNA: radionuclide angiography; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; FU: follow-up.

Neither bone marrow aspiration nor sham injection was performed in the control group. In the BMC group, bone marrow aspiration and intracoronary BMC injection were performed from day 7–10. Three months after STEMI, echocardiography, SPECT, RNA, cardiac MRI and coronary angiography were repeated.

Harvest and transfer of bone marrow cells

Bone marrow harvest (50 mL) and cell preparation, flow cytometry analysis of BMCs, and cell administration were performed according to standard procedures and are described in Supplementary material online.

Cardiac imaging

Three independent core imaging laboratories, blinded to treatment assignment, performed all measurements (prime investigator of the RNA and SPECT core lab: D. Agostini, MD, Caen; echo: Th. Le Tourneau, MD, PhD, Lille; IRM: J.P. Beregi, MD, Lille, France).

Doppler echocardiography

Images were recorded prospectively and analyzed offline at the core echo laboratory of the study in a blinded fashion. Left ventricular (LV) volumes and LVEF were calculated using the Simpson’s biplane method in apical 4- and 2- chamber views. LV volumes were indexed to body surface area.

Radionuclide angiography and single-photon-emission computed tomography

RNA was carried out in all patients to determine LVEF at rest (measured by Multiple Gated Acquisition scan). Thallium-201 SPECT imaging was performed according to a rest-redistribution protocol, using a standard camera to assess myocardial viability. Left ventricular segmentation in 17 segments as defined by the American Heart Association was used for all analyses. The activity of each LV segment was expressed as the mean activity of all pixels belonging to this sector divided by the highest value of pixel activity in the myocardium. Each segment was defined as viable (uptake > 60%), non-viable (uptake <50%), or equivocal (uptake 50–60%) (see Supplementary material online).

Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging

Cardiac MRI was performed for evaluating infarct size and the presence of microvascular obstruction using late contrast-enhanced images acquired 10 min after injection of 0.2 mmol/kg Gd-DTPA (Dotarem, Guerbet, France). LV function, volumes and regional contractility were also assessed (see Supplementary material online).

Coronary angiography

Patients underwent coronary angiography to assess the degree of restenosis in the stented segment of the infarct-related artery (IRA) at 3 months follow-up (see Supplementary material online).

Endpoints

The primary endpoint - improvement of myocardial viability - was defined as a gain of at least 2/17 viable segments 3 months after STEMI, assessed by resting 4 h thallium-201-gated-SPECT. As prespecified, major cardiovascular (CV) risk factors (age, gender, dyslipidemia, cigarette smoking, hypertension, diabetes), and post-MI prognostic factors (time to PCI, LVEF, infarct size, microvascular obstruction) were also tested for their association with improvement of myocardial viability 3 months after BMC administration. Secondary prespecified endpoints included changes in LVEF evaluated by RNA, MRI, and echocardiography; changes in LV end-diastolic and end-systolic volumes (EDV and ESV) at the time of and 3 months after AMI; infarct size by MRI; and binary restenosis by coronary angiography. Improvement of myocardial viability was also assessed on a segment-by-segment basis, counting the number of non-viable segment becoming viable.

Statistical analysis

The baseline characteristics were recorded for each treatment arm and compared using Student’s t test and Fisher’s exact test. Categorical variables were presented as count and percent, continuous variables as mean and standard deviation, median with interquartile ranges. Association of BMC injection with the primary endpoint was assessed by a Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test adjusted for stratification factors (diabetes status and time to PCI after the onset of STEMI (≤12 or >12 h)). Univariate analysis of major CV risk and post-MI prognosis factors was performed on the primary endpoint, except for diabetes and time to PCI as they were stratification randomization parameters. In a second step, CV risk factors (age, gender, tobacco status, hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes), time to PCI after the onset of AMI (≤12 or >12 h) and the presence of microvascular obstruction at MRI were introduced into a multivariate logistic regression analysis (odds ratio with 95% CI). Mann-Whitney and Wilcoxon signed rank tests were used to assess secondary endpoints.

Safety of BMC administration was analyzed using prespecified clinical endpoints and included major adverse cardiovascular events (MACEs) defined as death, re-hospitalization for heart failure, and ischemic events. Other clinical events were assessed as a post-hoc analysis. Only the first event for each patient was included in the analysis.

All analyses were performed using SAS 9.1 statistical software. p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. This study was registered with clinicaltrials.gov: number NCT00200707.

Results

Enrolment and baseline characteristics

A total of 122 patients with successfully reperfused STEMI by PCI and stent implantation within 24 h of the onset of chest pain gave written informed consent and was enrolled in the study. Twenty-one patients were excluded before randomization (Figure 1) because they did not meet the randomization criteria. Forty-nine of the remaining patients were randomly assigned to the control group and 52 to the BMC group. Both groups were well matched with respect to baseline characteristics, procedural characteristics of reperfusion therapy, and concomitant pharmacological therapy during the study (Table 1). Baseline recordings were obtained 4 ± 2 days after myocardial infarction for RNA, 5.3 ± 2.6 days for SPECT, 7 ± 2.2 days for echocardiography, and 7.1 ± 2.3 days for MRI. There were no significant differences in baseline parameters including EDV, ESV, LVEF, microvascular obstruction, and infarct size between the two groups (Table 1). Moreover, 71.8% of patients presented at least one segment with microvascular obstruction assessed by MRI after reperfusion therapy. The mean number of segments with microvascular obstruction was 2.4 ± 2.1 and was similar in both groups (p = 0.94).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the control group and patients who received intracoronary injection of bone marrow mononucleated cells (BMCs).

| Baseline characteristic | Control (n=49) | BMC (n=52) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean ± SD | 55 ± 11 | 56 ± 12 | 0.72 |

| Male, n (%) | 44 (89.8) | 42 (80.8) | 0.20 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2), mean ± SD | 26 ± 3.8 | 26 ± 3.4 | 0.66 |

| Risk factors, n (%) | |||

| Hypertension | 17 (34.7) | 18 (34.6) | 0.58 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 17 (34.7) | 24 (46.2) | 0.24 |

| Diabetes | 9 (18.4) | 11 (21.2) | 0.73 |

| Current smoker (tobacco in the last 3 months before AMI) | 26 (53.1) | 28 (53.8) | 0.94 |

| Family history of CAD | 22 (44.9) | 17 (32.7) | 0.21 |

| Previous history, n (%) | |||

| Atrial fibrillation | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | - |

| Ventricular arrhythmia | 0 (0) | 2 (3.8) | 0.49* |

| Supraventricular arrhythmia | 0 (0) | 1 (1.9) | 0.33* |

| Stroke | 0 (0) | 2 (3.8) | 0.23* |

| Peripheral arterial occlusive disease | 2 (4.1) | 1 (1.9) | 0.61* |

| Heart failure | 1 (2.0) | 1 (1.9) | 0.74* |

| MI treatment, % | |||

| Time to revascularization (<12 h) | 75.5 | 75.0 | 0.95 |

| Infarct-related artery (LAD) | 95.7 | 91.8 | 0.68* |

| TIMI flow 2–3 after PCI | 100 | 97.9 | 0.46 |

| At admission | |||

| Killip, % | 0.72* | ||

| 1 or 2 | 93.3 | 95.8 | |

| 3 or 4 | 6.7 | 4.2 | |

| Heart rate (bpm), mean ± SD | 83 ± 17 | 83 ± 17 | 0.95 |

| Mean systolic arterial pressure (mmHg), mean ± SD | 126 ± 22 | 125 ± 35 | 0.94 |

| Mean diastolic arterial pressure (mmHg), mean ± SD | 79 ± 14 | 81 ± 19 | 0.49 |

| Mean LVEF, % (RNA) ± SD | 37.0 ± 6.7 | 35.6 ± 7.0 | 0.29 |

| LVEF <30%, n (%) | 40 (85.1) | 41 (82) | 0.68 |

| Cardiac imaging, mean ± SD | |||

| EDV (echo), mL/m2 | 56.9 ± 13.1 | 57.9 ± 15.6 | 0.72 |

| ESV (echo), mL/m2 | 34.6 ± 10.0 | 36.6 ± 12.9 | 0.40 |

| LVEF (echo), % | 39.8 ± 7.0 | 38.1 ± 7.9 | 0.26 |

| Infarct size (MRI), % | 39.4 ± 10.0 | 40.1 ± 11.9 | 0.83 |

| Microvascular obstruction (MRI), # segment | 2.38 ± 2.1 | 2.42 ± 2.2 | 0.94 |

| # patients with MVO (%) | 32/42 (76.2) | 29/43 (67.4) | 0.47 |

| Non-viable segments (SPECT), # segment | 4.6 ± 2.5 | 5.6 ± 2.7 | 0.10 |

| Treatments at 3 months follow-up, n (%) | Control (n=43) | BMC (n=47) | p value |

| Aspirin/clopidogrel | 43 (100) | 47 (100) | 0.73 |

| Beta-blockers | 43 (100) | 46 (97.9) | 0.34 |

| ACE inhibitors/angiotensin II receptor | 90.7 (39) | 95.7 (45) | 0.42 |

| Statins | 43 (100) | 47 (100) | 0.70 |

| Diuretics | 12 (28.0) | 17 (36.2) | 0.40 |

| Aldosterone antagonists | 17 (39.6) | 11 (23.4) | 0.10 |

| Anticoagulants | 9 (20.9) | 7 (14.9) | 0.46 |

AMI: acute myocardial infarction; MI: myocardial infarction; CAD: coronary artery disease; LAD: left anterior descending artery; TIMI: thrombolysis in myocardial infarction; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; SD: standard deviation; LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction; EDV: end-diastolic volume; ESV: end-systolic volume; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; MVO: Microvascular obstruction; SPECT: resting 4 h thallium-201-gated-single-photon-emission computed tomography; ACE: angiotensin-converting enzyme.

Fisher’s exact.

Forty-four patients completed the follow-up in the control group and 48 in the BMC group. In the control group, two patients were withdrawn from the study before day 7 (one patient required injections of steroids for angioneurotic edema and the other because of a post-MI ventricular septal defect that might have interfered with recovery of cardiac function). Three further patients refused to complete the 3-month follow-up. In the BMC group, two patients were excluded before bone marrow aspiration because of a transient ischemic attack and a randomization error; one patient did not have bone marrow aspiration because of thrombopenia induced by a GP2b3a inhibitor. Of the remaining 49 patients in the BMC group, one died 1-month post-MI and one refused to complete the 3-month follow-up.

Characterization of the cell therapy product

Bone marrow aspiration and intracoronary cell injection were performed on the same day for each patient, at a mean of 9.3 ± 1.7 days after PCI. The mean delay between BMC preparation and intracoronary injection was 5 h 28 min ± 1 h 30 min. The injected cell number was 98.3 ± 8.7 × 106 autologous mononucleated BMCs, with a mean percentage of viable cells of 98.4 ± 1.1% (Table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics of the cell therapy product.

| Characteristic | n | Mean ± SD |

|---|---|---|

| Number of mononucleated cells (× 106) | 49 | 98.3 ± 8.7 |

| Viability of cells (%) | 49 | 98.4 ± 1.1 |

| Surface markers (FACS analysis) | ||

| CD34+/CD45+ (%) | 43 | 1.2 ± 0.4 |

| CD34+/CD133+/CD45+ (%) | 42 | 1.1 ± 0.4 |

| CD34+/KDR+ (%) | 36 | 0.02 ± 0.01 |

| CD34+/CXCR4+/CD45+ (%) | 43 | 1.1 ± 0.4 |

| Colony forming unit capacity | ||

| Hematopoietic colonies (CFU/1 × 105 BMCs) | 38 | 84.3 ± 63.8 |

CFU: colony-forming units; BMCs: bone marrow cells.

Myocardial viability

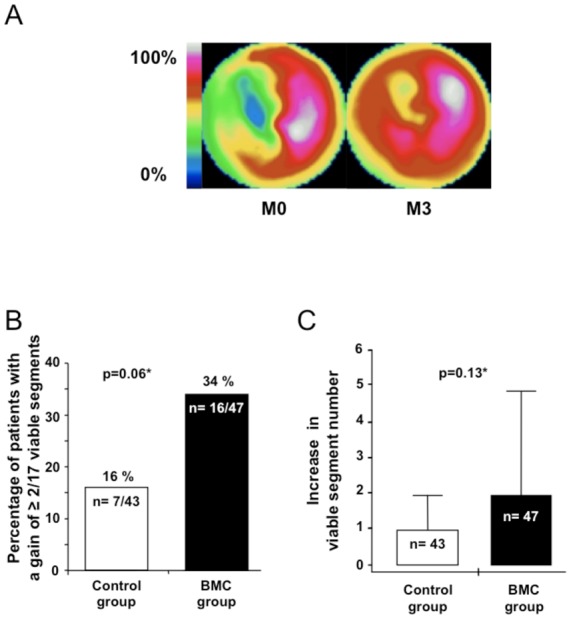

To analyze the primary end-point of improvement of myocardial viability (Figure 2A), SPECT images were obtained from 43 and 47 patients in the control and BMC groups, respectively.

Figure 2.

SPECT myocardial viability at baseline and 3 months after myocardial infarction. (A) Cardiac polar map example of myocardial viability improvement using SPECT from baseline to 3 months. Baseline evaluation revealed a large viability defect in the ventricular septum from the apex to the base. Evaluation, after 3 months, showed an improvement in myocardial viability of the septum from the apex to the base segments. (B) percentage of patients in the control and BMC groups with an increase of ≥2/17 viable segments. (C) Increase in viable segment number/patient (median with interquartile ranges). *Adjusted for diabetes and time to revascularization (≤12 or >12 h).

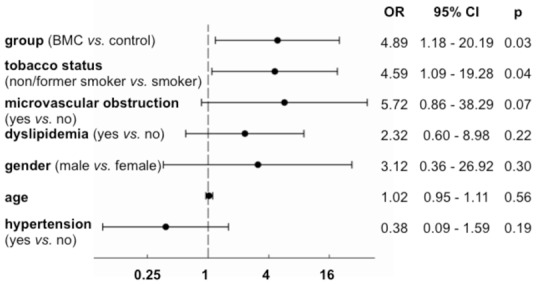

At 3 months after BMC infusion, 7/43 (16%) patients in the control group compared to 16/47 (34%) patients in the BMC group improved their myocardial viability (p=0.06) (Figure 2B). The same trend was observed when improvement of viability was defined as a gain of at least three viable segments (3/43, 7% in the control group vs. 10/47, 21% in the BMC group, p=0.07). Univariate analysis of CV risk factors and major post-MI prognosis factors showed that smoking status at the time of AMI was the only significant factor related to viability (Table 3, p=0.02). In a multivariate logistic regression analysis (Figure 3), including CV risk factors, time to PCI and the presence of microvascular obstruction on MRI, BMC infusion was significantly associated with improvement of myocardial viability (p=0.03). Improvement of myocardial viability was also more likely to occur among non-smokers (p=0.04) and a positive trend was observed in patients with microvascular obstruction (p=0.07).

Table 3.

Univariate analysis of major cardiovascular risk and post-MI prognosis factors on myocardial viability improvement (≥ 2 non-viable segments becoming viable on SPECT) in patients from the control and Bone Marrow Cell groups.

| Odds ratios | 95% confidence interval | p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group (BMC vs. Control) | 2.654 | 0.967 | 7.286 | 0.06 |

| Hypertension (yes vs. no) | 0.956 | 0.354 | 2.579 | 0.93 |

| Dyslipidemia (yes vs. no) | 2.05 | 0.785 | 5.353 | 0.14 |

| Age | 1.038 | 0.984 | 1.095 | 0.17 |

| Gender (male vs. female) | 0.644 | 0.174 | 2.379 | 0.51 |

| Tobacco status (non/former smoker vs. smoker) | 3.840 | 1.389 | 10.615 | 0.01 |

| LVEF at baseline (echo) | 1.043 | 0.970 | 1.122 | 0.26 |

| LVEF at baseline (RNA) | 1.007 | 0.935 | 1.084 | 0.86 |

| LVEF at baseline (MRI) | 1.019 | 0.954 | 1.088 | 0.58 |

| Infarct size (MRI) | 0.973 | 0.925 | 1.024 | 0.29 |

| Microvascular obstruction (yes vs. no) | 1.302 | 0.373 | 4.548 | 0.68 |

| # segments with MVO (MRI) | 1.102 | 0.861 | 1.411 | 0.44 |

BMC: Bone marrow cell; LVEF: Left ventricular ejection fraction; RNA: Radionuclide angiography; MI, Myocardial infarction; MRI: Magnetic resonance imaging; MVO: Microvascular obstruction.

Figure 3.

Multivariate logistic regression analysis for improvement of at least 2 non-viable segments becoming viable (n = 77). OR: Odds ratio; CI: Confidence interval; p: p-value.

Changes in viability were also analyzed on a segment-by-segment basis. A mean of 0.8 ± 1.1 non-viable segments became viable in the control group and 1.2 ± 1.5 in the BMC group (p = 0.13) (Figure 2C). The number of viable segments that worsened by becoming non-viable was low and similar in both groups (0.3 ± 0.7 in the control group vs. 0.2 ± 0.5 in the BMC group; p=0.90).

LV function and remodeling

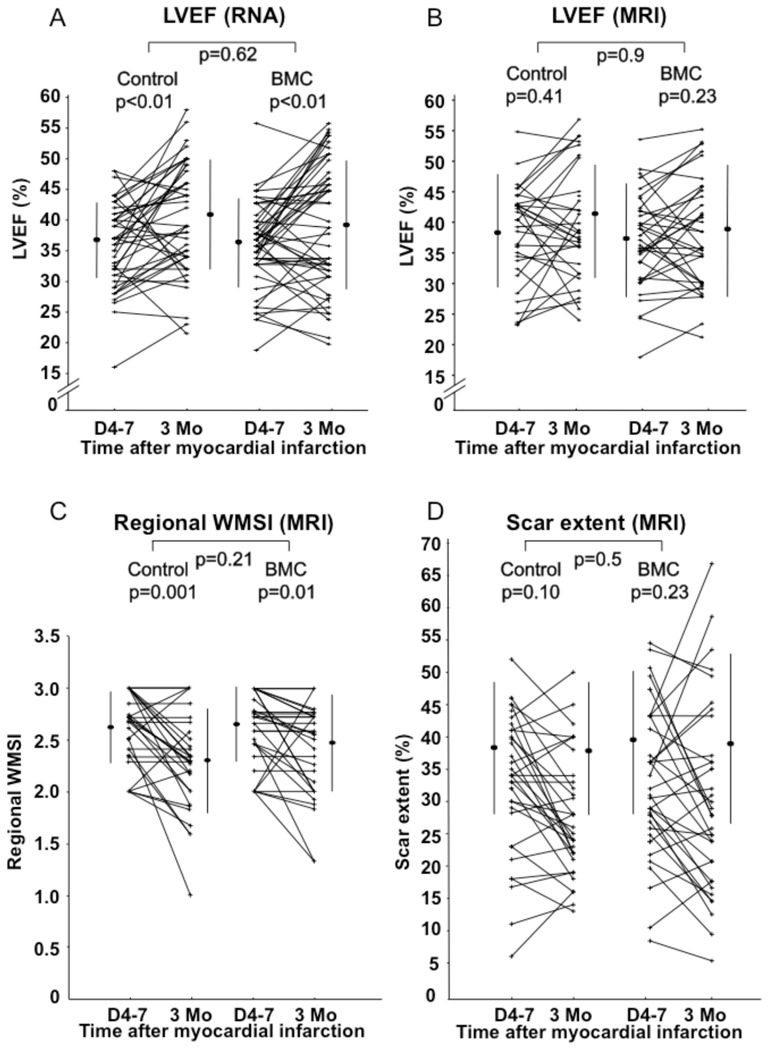

Among the prespecified secondary endpoints, LVEF measured by RNA significantly increased from a mean of 37.0 ± 6.7% at baseline to 41.3 ± 9.0% at 3 months in the control group, compared to 35.6 ± 7.0% at baseline to 38.9 ± 10.3% at 3 months in the BMC group, with a mean increase of 4.3% (p = 0.001) in the control group and 3.3% (p = 0.009) in the BMC group (Figure 4A). At 3 months, LVEF did not differ significantly between BMC and control groups (p = 0.62). MRI observed a similar pattern with improvement of LVEF within groups (LVEF from baseline to 3 months: 38.7 ± 9.2% to 40.9 ± 10.2% in the control group, vs. 37 ± 9.8% to 38.9 ± 9.7% in the BMC group), albeit with no difference between groups (p = 0.9, Figure 4B). Global wall motion score index (WMSI) on MRI decreased significantly in both groups (from 1.74±0.37 to 1.33±0.34 in control group, p=0.001; from 1.79±0.40 to 1.22±0.40 in BMC group, p<0.001), and there was no difference between groups (p=0.11). Regional WMSI also decreased significantly in both groups (from 2.62+0.34 to 2.29+0.50 in control group, p=0.001; from 2.64+0.36 to 2.46+0.46 in BMC group, p=0.01) and there was no difference between groups (p=0.21, Figure 4C). Left ventricular volumes were similar between groups at 3 months (see Supplementary material online).

Figure 4.

Evaluation of left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) and scar extent at baseline and 3 months. (A) LVEF evaluated by radionuclide angiography. (B) LVEF evaluated by MRI. (C) Regional wall motion score index (WMSI) on cardiac MRI. (D) Scar extent evaluated by MRI.

Infarct size

Infarct size measured as the scar extent on MRI did not significantly change in the control group and in the BMC group between baseline and 3 months follow up (from 39.1 ± 10% to 38.3 ± 10.5% in the control group, and from 40.1 ± 11.9% to 39.3 ± 13.4% in the BMC group). Changes were similar between control and BMC groups (p = 0.5, Figure 4D).

Safety

One patient in the BMC group died from sudden death one month after STEMI. An implantable cardioverter-defibrillator was inserted for primary prevention within the 3-month follow-up in one patient in the control group and four in the BMC group (p = 0.36, Fisher’s exact). There were no significant differences in MACEs between the groups (Table 4). The rate of coronary artery restenosis at 3 months follow-up was similar in both groups (p = 0.88).

Table 4.

Major adverse cardiac events.

| Control | BMC | P-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Death | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1.9 | 0.51* |

| Binary restenosis | 11 | 22.4 | 12 | 23 | 0.88 |

| Re-hospitalization for heart failure | 2 | 4.1 | 4 | 7.7 | 0.68* |

| Ischemic events | 2 | 4.1 | 6 | 11.5 | 0.27* |

| Thrombosis | 2 | 4.1 | 3 | 5.8 | 0.83* |

| Arrhythmia | 2 | 4.1 | 2 | 3.8 | 0.67* |

| Pericarditis | 2 | 4.1 | 2 | 3.8 | 0.67* |

| Other | 2 | 4.1 | 3 | 5.8 | 0.80* |

Fisher’s exact

Discussion

This multicenter, randomized, controlled trial addressed the effect of intracoronary injection of BMCs performed 9 days after AMI in addition to optimal “state-of-the-art” reperfusion and pharmacological therapy on myocardial viability at 3 months. BMC infusion was associated with significant improvement in myocardial viability 3 months after AMI in a multivariate analysis including major post-MI prognostic factors, whereas there was a strong trend towards improvement in univariate analysis. Importantly, non-smoking status was associated with greater improvement of myocardial viability and a trend was observed in patients with presence of microvascular obstruction. The statistical discordance between results of univariate and multivariate statistical analyses suggest that BMC infusion efficacy is modulated by patient risk factors such as smoking status and microvascular obstruction. Identification of those factors will be pivotal to better define a group of patients that will benefit from cardiac cell therapy.

As improvement of systolic function might result from recovery of stunned myocardium, we used myocardial viability as primary endpoint to assess the efficacy of cell therapy. Myocardial viability is a cornerstone for preservation/improvement of LV function, or limitation of LV remodeling after PCI. Myocardial viability can be assessed by different methods namely echocardiography, SPECT/PET and MRI. These methods are often used in combination in daily practice as they provide complementary information. Rest-redistribution thallium 201-SPECT was chosen to evaluate changes in myocardial viability since it provides a good estimate of myocyte cellular membrane integrity. This technique is widely used and available in most centers, with a reproducible quantitative assessment of viability expressed as % of thallium intake for each myocardial segment. The commonly described mechanisms for cell therapy efficacy, including myocardial regeneration, salvage, and local perfusion should lead to improvement of myocardial viability as a primary event that would later translate into improvement of LVEF and/or limitation of LV remodeling. Indeed, 34% (16/47) of patients treated with autologous BMC had improved myocardial viability compared to the control group (16%, 7/43), although this was only statistically significant in multivariate analysis.

Interestingly, the patients included in our study corresponded to the subgroup of patients who demonstrated the best improvement of LVEF after BMC therapy in the post-hoc analysis of the REPAIR-AMI trial[12]: they had a marked alteration of LVEF (<45%) and were treated after the 5th day post-STEMI. The time of BMC administration (9.3 ± 1.7 days) was in accordance with clinical data on patients with acute MI showing maximum blood mobilization of endothelial progenitor cells from 7 to 10 days post-AMI[13].Despite a nearly two-fold greater increase in viable segments in the BMC group compared to control patients, no difference was observed in LVEF with any imaging method including RNA, echocardiography, and MRI. There is a complex relation between viability and contractility after STEMI, with contractile dysfunction related not only to the balance between necrosis and viability, but also to the extent of metabolic damage in viable myocytes,[14]and the awakening of hibernating/stunned myocardium after coronary revascularization of the myocardial risk area. Hence, recovery of contractility in some but not all regions with preserved metabolic viability might be observed[15].Interestingly, the strong trend towards improvement in myocardial viability observed in this study may be placed alongside restoring microvascular function,[16]as microvascular obstruction measured by MRI has been associated to worse clinical outcome[17,18].

Although the mechanisms involved in improving myocardial viability after intracoronary infusion of BMC are not understood, risk factors such as smoking or microvascular obstruction may represent important modulators. Smoking is known to increase oxidative stress, a well-established stimulus for apoptotic cell death,[19,20]and CD34+endothelial progenitor cells have been shown to be very sensitive to apoptosis induction,[9]which may have interfered with recovery of myocardial viability in smokers. Moreover, analysis of individual risk factors indicates that smoking is a factor that contributes to reduced numbers of circulating progenitor cells[9].

Study limitations

The design of our study did not include a placebo group, as the goal of the study was to evaluate the efficacy of the whole procedure, including intracoronary injection and BMC administration. Sham injection was not performed in the control group to compare the effect of BMC therapy to the “state-of-the-art” treatment of patients with STEMI. One could argue that the BMC group may have been influenced by the cell application method (e.g., post-conditioning potentially influencing viability). Nevertheless, repeated brief episodes of inflation-deflation of the angioplasty balloon reduced infarct size only when performed immediately after re-opening of the culprit coronary artery[21].In our trial, the intracoronary cell therapy procedure was performed 9.3 ± 1.7 days after the IRA has been reopened. We also acknowledge our study has a short-term follow-up; however, long-term effects of BMC therapy are controversial[4]and our aim was to investigate short-term effect on myocardial viability in an effort to better understand the underlying mechanisms of cardiac cell therapy after AMI.

Conclusion

Intracoronary autologous BMC administration to patients with decreased LVEF after AMI was associated with improvement of myocardial viability in multivariate –but not in univariate – analysis. The results of our multivariate analysis generate hypotheses about the potential role of active smoking and microvascular obstruction in cardiac cell therapy efficacy that should be taken into account for designing large international trials that will address the clinical relevance of BMC administration.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported in part by a PHRC (Programme Hospitalier de Recherche Clinique) from the French Department of Health, and grants from the Association Française contre les Myopathies and the Fondation de France. There was no relationship with industry.

The authors thank all hematologists, surgeons, echocardiographers, radiologists, nuclear physicians, and research technicians involved in the study.

Footnotes

Supplementary material is available at European Heart Journal online.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Clinical Trial Registration Information: URL: http://www.clinicaltrials.gov. Unique identifier NCT00200707.

References

- 1.Strauer BE, Brehm M, Zeus T, Kostering M, Hernandez A, Sorg RV, Kogler G, Wernet P. Repair of infarcted myocardium by autologous intracoronary mononuclear bone marrow cell transplantation in humans. Circulation. 2002;106:1913–1918. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000034046.87607.1c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schachinger V, Erbs S, Elsasser A, Haberbosch W, Hambrecht R, Holschermann H, Yu J, Corti R, Mathey DG, Hamm CW, Suselbeck T, Assmus B, Tonn T, Dimmeler S, Zeiher AM. Intracoronary bone marrow-derived progenitor cells in acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1210–1221. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa060186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wollert KC, Meyer GP, Lotz J, Ringes-Lichtenberg S, Lippolt P, Breidenbach C, Fichtner S, Korte T, Hornig B, Messinger D, Arseniev L, Hertenstein B, Ganser A, Drexler H. Intracoronary autologous bone-marrow cell transfer after myocardial infarction: the BOOST randomised controlled clinical trial. Lancet. 2004;364:141–148. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16626-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meyer GP, Wollert KC, Lotz J, Steffens J, Lippolt P, Fichtner S, Hecker H, Schaefer A, Arseniev L, Hertenstein B, Ganser A, Drexler H. Intracoronary bone marrow cell transfer after myocardial infarction: eighteen months’ follow-up data from the randomized, controlled BOOST (BOne marrOw transfer to enhance ST-elevation infarct regeneration) trial. Circulation. 2006;113:1287–1294. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.575118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Janssens S, Dubois C, Bogaert J, Theunissen K, Deroose C, Desmet W, Kalantzi M, Herbots L, Sinnaeve P, Dens J, Maertens J, Rademakers F, Dymarkowski S, Gheysens O, Van Cleemput J, Bormans G, Nuyts J, Belmans A, Mortelmans L, Boogaerts M, Van de Werf F. Autologous bone marrow-derived stem-cell transfer in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2006;367:113–121. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67861-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lunde K, Solheim S, Aakhus S, Arnesen H, Abdelnoor M, Egeland T, Endresen K, Ilebekk A, Mangschau A, Fjeld JG, Smith HJ, Taraldsrud E, Grogaard HK, Bjornerheim R, Brekke M, Muller C, Hopp E, Ragnarsson A, Brinchmann JE, Forfang K. Intracoronary injection of mononuclear bone marrow cells in acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1199–1209. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tendera M, Wojakowski W, Ruzyllo W, Chojnowska L, Kepka C, Tracz W, Musialek P, Piwowarska W, Nessler J, Buszman P, Grajek S, Breborowicz P, Majka M, Ratajczak MZ. Intracoronary infusion of bone marrow-derived selected CD34+CXCR4+ cells and non-selected mononuclear cells in patients with acute STEMI and reduced left ventricular ejection fraction: results of randomized, multicentre Myocardial Regeneration by Intracoronary Infusion of Selected Population of Stem Cells in Acute Myocardial Infarction (REGENT) Trial. Eur Heart J. 2009;30:1313–1321. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martin-Rendon E, Brunskill SJ, Hyde CJ, Stanworth SJ, Mathur A, Watt SM. Autologous bone marrow stem cells to treat acute myocardial infarction: a systematic review. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:1807–1818. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vasa M, Fichtlscherer S, Aicher A, Adler K, Urbich C, Martin H, Zeiher AM, Dimmeler S. Number and migratory activity of circulating endothelial progenitor cells inversely correlate with risk factors for coronary artery disease. Circ Res. 2001;89:E1–E7. doi: 10.1161/hh1301.093953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Senior R, Kaul S, Lahiri A. Myocardial viability on echocardiography predicts long-term survival after revascularization in patients with ischemic congestive heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;33:1848–1854. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00102-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dimmeler S, Zeiher AM. Vascular repair by circulating endothelial progenitor cells: the missing link in atherosclerosis? J Mol Med. 2004;82:671–677. doi: 10.1007/s00109-004-0580-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dill T, Schachinger V, Rolf A, Mollmann S, Thiele H, Tillmanns H, Assmus B, Dimmeler S, Zeiher AM, Hamm C. Intracoronary administration of bone marrow-derived progenitor cells improves left ventricular function in patients at risk for adverse remodeling after acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: results of the Reinfusion of Enriched Progenitor cells And Infarct Remodeling in Acute Myocardial Infarction study (REPAIR-AMI) cardiac magnetic resonance imaging substudy. Am Heart J. 2009;157:541–547. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shintani S, Murohara T, Ikeda H, Ueno T, Sasaki K, Duan J, Imaizumi T. Augmentation of postnatal neovascularization with autologous bone marrow transplantation. Circulation. 2001;103:897–903. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.6.897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beygui F, Le Feuvre C, Helft G, Maunoury C, Metzger JP. Myocardial viability, coronary flow reserve, and in-hospital predictors of late recovery of contractility following successful primary stenting for acute myocardial infarction. Heart. 2003;89:179–183. doi: 10.1136/heart.89.2.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Panza JA, Dilsizian V, Laurienzo JM, Curiel RV, Katsiyiannis PT. Relation between thallium uptake and contractile response to dobutamine. Implications regarding myocardial viability in patients with chronic coronary artery disease and left ventricular dysfunction. Circulation. 1995;91:990–998. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.91.4.990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Erbs S, Linke A, Schachinger V, Assmus B, Thiele H, Diederich KW, Hoffmann C, Dimmeler S, Tonn T, Hambrecht R, Zeiher AM, Schuler G. Restoration of microvascular function in the infarct-related artery by intracoronary transplantation of bone marrow progenitor cells in patients with acute myocardial infarction: the Doppler Substudy of the Reinfusion of Enriched Progenitor Cells and Infarct Remodeling in Acute Myocardial Infarction (REPAIR-AMI) trial. Circulation. 2007;116:366–374. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.671545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu KC, Zerhouni EA, Judd RM, Lugo-Olivieri CH, Barouch LA, Schulman SP, Blumenthal RS, Lima JA. Prognostic significance of microvascular obstruction by magnetic resonance imaging in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1998;97:765–772. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.8.765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hombach V, Grebe O, Merkle N, Waldenmaier S, Hoher M, Kochs M, Wohrle J, Kestler HA. Sequelae of acute myocardial infarction regarding cardiac structure and function and their prognostic significance as assessed by magnetic resonance imaging. Eur Heart J. 2005;26:549–557. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dimmeler S, Zeiher AM. Reactive oxygen species and vascular cell apoptosis in response to angiotensin II and pro-atherosclerotic factors. Regul Pept. 2000;90:19–25. doi: 10.1016/s0167-0115(00)00105-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li AE, Ito H, Rovira, Kim KS, Takeda K, Yu ZY, Ferrans VJ, Finkel T. A role for reactive oxygen species in endothelial cell anoikis. Circ Res. 1999;85:304–310. doi: 10.1161/01.res.85.4.304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Staat P, Rioufol G, Piot C, Cottin Y, Cung TT, L’Huillier I, Aupetit JF, Bonnefoy E, Finet G, Andre-Fouet X, Ovize M. Postconditioning the human heart. Circulation. 2005;112:2143–2148. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.558122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.