Abstract

Objective

The aim of this study was to investigate the treatment of zygomatic bone and zygomatic arch fractures without other facial fractures.

Patients and Methods

A 10 year (2000–2010) retrospective study involving 310 patients admitted and treated for zygomatic bone and zygomatic arch fractures at the department of oral and maxillofacial surgery was done. The data collection protocol included: age, gender, site, type of fracture. Other data presented included clinical diagnosis, radiographic examination findings as well as preoperative and postoperative imaging for evaluation of the fracture. Descriptive statistics was performed with SPSS version 16.

Results

The ages of the patients ranged from 10 to 76 years old, mean age was 32.33 years. 237(80.6%) of the patients were males and 73 (19.4%) were females (Table 1). According to the site of fracture, the patients were divided into three groups: group A, with zygomatic bone fracture, group B with zygomatic arch fracture and group C with co-existing zygomatic bone and zygomatic arch fracture. Regarding the site of fracture 57.7% of the patients had fractures of the zygomatic bone, 13.8% had fractures of the zygomatic arch and 28.4% had fractures of both zygomatic bone and zygomatic arch.

The treatment of both fractures was: closed reduction for isolated zygomatic arch fractures; open reduction and internal rigid fixation through a coronal incision was performed in comminuted arch fractures and displaced fractures.

Conclusion

In this study, the majority of the patients were young adult men; road traffic accidents were the leading cause of fractures. According to the site of fracture, various modalities of treatment were used and all the patients achieved satisfactory results without any complications after operation.

Keywords: Treatment, Fracture, Zygomatic arch, Evaluation

Introduction

Fracture of the zygomatic bone is a common fracture of the facial skeleton; the zygomatic bone forms the most anterolateral projection one on each side of the middle face.

The zygomatic bone is attached to the maxilla at the zygomaticomaxillary (ZM) suture and alveolus forming the zygomaticomaxillary buttress. Zygomaticomaxillary suture line extends to the inferior orbital rim; laterally, the zygomatic bone attaches to the zygomatic process of the temporal bone to form the zygomatic arch. Various terms have been ascribed to malar eminence fracture including tripod fracture and zygomatic fracture.

The zygomaticomaxillary region (ZM) is the third most commonly fractured facial area.

The majority of the zygomaticomaxillary fractures occur in men. These injuries are most commonly seen in the second to third decades of life and are most associated with road traffic accidents.

The pattern of fractures can manifest as isolated fracture, in combination with middle third fracture or with internal orbital fracture; however, in this study we focused only on the modality used in the treatment of zygomatic bone and zygomatic arch fractures. The treatment was divided into closed reduction, open reduction and internal fixation with miniplate and screws. Various approaches to the zygomatic maxillary complex have been well described in literature; these include: coronal, eyebrow, upper eye lid, transconjunctival and infraciliary lower eye lid, and maxillary vestibular approaches.

The approach to the zygomaticomaxillary complex is dictated by the degree of injury and need for exposure for open reduction and internal fixation.

Patients and Methods

Over a 10 year period (2000–2010), 310 patients with zygomatic bone and zygomatic arch fractures were treated at a hospital and school of stomatology. Retrospective study was conducted to analyze the data. The data collection protocol included: age, gender, site and type of fracture and treatment were used (Tables 1 and 2). Other data presented includes clinical diagnosis, radiographic examination findings as well as preoperative and postoperative imaging for the evaluation of the treatment (Figs. 1, 2, 3).

Table 1.

Distribution of zygomatic bone and arch fractures by Age

| Age | Male | Female | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| <19 | 45 | 12 | 57 |

| 20–29 | 62 | 13 | 75 |

| 30–39 | 79 | 21 | 100 |

| 40–49 | 35 | 26 | 61 |

| 50–59 | 08 | 01 | 09 |

| 60–69 | 07 | 00 | 07 |

| >69 | 01 | 00 | 01 |

| Total | 273 | 73 | 310 |

Table 2.

Distribution of zygomatic bone and arch fractures by site

| Group name | Fracture site | Frequency | Percent within group | Percent-overall |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bone fracture (Group A) | Left zygomatic bone fracture | 95 | 53.1 | 30.6 |

| Right Zygomatic bone fracture | 66 | 36.9 | 21.3 | |

| Bilateral zygomatic bone fracture | 9 | 5.0 | 2.9 | |

| Comminuted fracture of zygomatic bone | 5 | 2.8 | 1.6 | |

| Multiple fracture of zygomatic bone | 4 | 2.2 | 1.3 | |

| Total Group A | 179 | 100 | 57.7 | |

| Arch fracture (Group B) | Left zygomatic arch fracture | 24 | 55.8 | 7.7 |

| Right zygomatic arch fracture | 15 | 34.9 | 4.8 | |

| Right lateral zygomatic arch fracture | 4 | 9.3 | 1.3 | |

| Total Group B | 43 | 100 | 13.8 | |

| Bone and arch fracture (Group C) | Right zygomatic bone and arch fracture | 45 | 51.1 | 14.5 |

| Left zygomatic bone and arch fracture | 39 | 44.3 | 12.6 | |

| Bilateral zygomatic bone and arch fracture | 3 | 3.4 | 1.0 | |

| Multiple zygomatic bone and arch fracture | 1 | 1.1 | 0.3 | |

| Total Group C | 88 | 100 | 28.4 | |

| Grand total | 310 | – | 100 | |

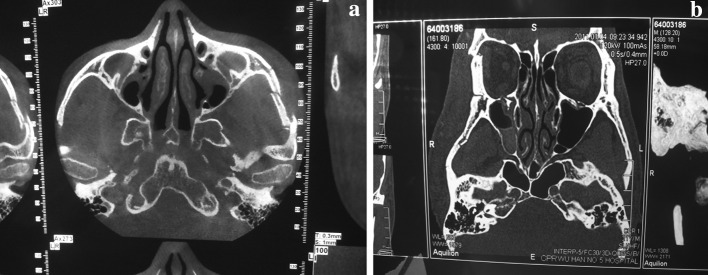

Fig. 1.

Preoperative view of different patients with zygomatic bone and arch fracture: a axial CT scan demonstrating a segmental fracture of zygomatic arch left side, b a coronal CT scan demonstrates the fronto-zygomatic bone and orbito-zygomatic bone fracture

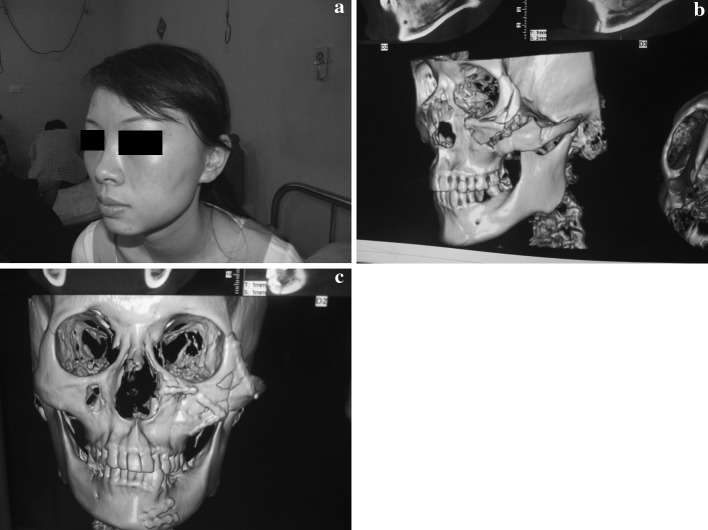

Fig. 2.

Preoperative view of patient with zygomatic bone fracture: a before operation showing asymmetry of the face of patient, b preoperative 3D-CT view of zygomatic bone fracture and c The postoperative 3D- reconstructed CT image showing fixation with screws and miniplates of zygomatico maxillary complex

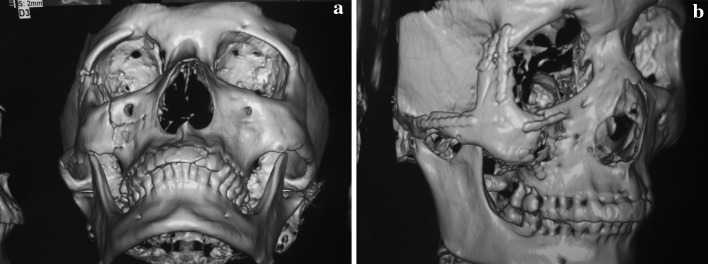

Fig. 3.

CT scan view: a before operation, b after operation showing anatomic reduction and fixation of fracture using screws and miniplates

Patients presenting with zygomatic bone and zygomatic arch fractures will frequently exhibit ecchymosis, edema and tenderness in the overlying soft tissues. Zygomaticomaxillary complex fracture can affect mastication through impingement by a depressed zygomatic arch on the temporalis muscle and coronoid process of the mandible; this can result in trismus and pain with mastication. For radiographic examination CT scan provides better resolution of the fractures and a three dimensional anatomy is better appreciated. Descriptive statistics was performed and data with SPSS version 16.

Results

The ages of the patients ranged from 10 to 76 years old, mean age 32.33 years. 237(80, 6%) were males and 73(19.4%) females were recorded during the study period giving a male: female ratio of 3:1. Patients in the 30-40 years age group were most often involved (Table 1).The etiology of most of the trauma recorded was road traffic accidents.

In this study patients were divided into three groups according to the site of fracture: GroupA patients with zygomatic bone fracture (left, right bilateral, comminuted, multiple).

GroupB with zygomatic arch fracture (left, right, bilateral) and groupC with zygomatic bone and zygomatic arch fracture.

Regarding the results in group A patient with zygomatic bone fracture were divided into: left zygomatic bone (53. 1%), right zygomatic bone fracture (36. 9%), bilateral zygomatic bone fracture (5.0%), left comminuted fracture of zygomatic bone (2.8%) and multiple fracture (2.2%). For groupA, the total percentage of patients with zygomatic bone fracture was 57.7%. For the group B, with zygomatic arch fracture, the sub-divisions were: right zygomatic arch fracture (34.9%), right lateral zygomatic arch fracture (9.3%), left zygomatic arch fracture (55.8). The total percentage of patients of with zygomatic arch fracture was 13.8%. GroupC, comprising both zygomatic bone and zygomatic arch fracture the sub-divisions included: right zygomatic bone and zygomatic arch fracture(51.1%), left zygomatic bone and zygomatic arch fracture 44.3%, bilateral zygomatic bone and zygomatic arch fracture 3.4%, multiple Zygomatic bone and zygomatic arch fracture 1.1%. The total percentage in this group was 28.4% (Table 2).

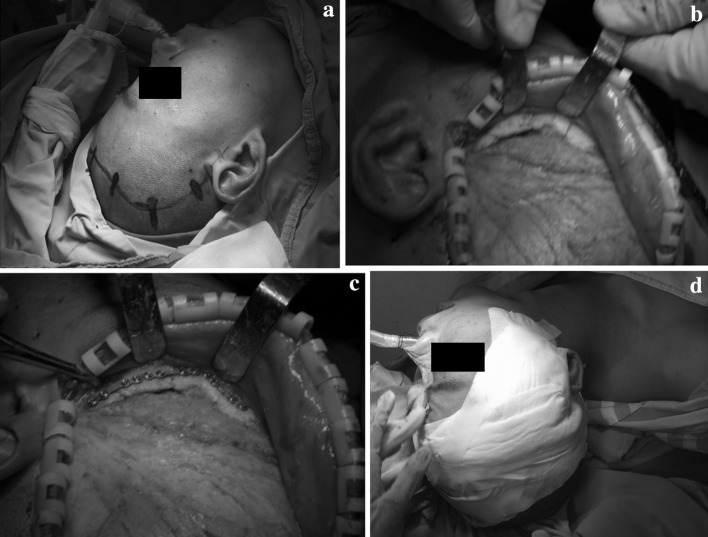

The treatment modalities were done into open reduction and internal fixation and closed reduction of all patients admitted in the unit (Fig. 4). Patients treated by open reduction and internal fixation with miniplate and screws constituted a percentage of 90.6%. Closed reduction constituted a percentage of 9.4%.

Fig. 4.

Hemi-coronal approach of zygomatic arch fracture: a preoperative design, b exposition and reduction of the fracture, c fixation using miniplates and screws

The treatment of most patients with the zygomatic bone and zygomatic arch were achieved without any complication. Clinical examination were performed at 4, 6 and 24 weeks postoperatively with the aim of detecting early osteosynthesis failures and early adverse reactions during biodegradation.

Discussion

The present study recorded more fractures of the zygomatic bone 57.7% than those of the zygomatic arch 13.8% or combined zygomatic bone and arch 28.4%. This was probably because of the predominant role of road traffic accidents, in which most impacts to the face were most likely frontal. Fractures were less frequent in children and adults over 70 years of age. However, all 310 patients, treated with open reduction and internal fixation and closed reduction, gave good results with satisfactory cosmetic outcomes.

According to many authors, as per literature documented, the techniques used for the treatment of zygomatic bone and arch fracture wary. American and European maxillofacial surgeons are engaged in debates as to whether the reduction of a displaced, and or fractured zygoma should be open or closed.

Various approaches have been described by many authors regarding the evaluation and treatment of zygomatic bone and arch fractures. Skeen (1900) categorized zygomatic fractures as those of the arch, body, or the sutural disjunction. He was the first to describe an internal approach to the zygomatic arch via a gingivobuccal sulcus incision. Gillie’s method remains in use today for elevation of the zygomatic arch. Adams recognized the need for greater stabilization in more comminuted fractures and was one of the first to document internal wire fixation. This technique described by Adams remained the mainstay of treatment at many institutions for years. A study performed by Dingman and Natving demonstrated that many zygoma fractures treated with a closed reduction technique and then later re-examined were more severe than they had appeared clinically. They concluded that most displaced fractures of zygoma should be treated by open reduction and internal fixation.

Many recent studies showed that young surgeons have adopted new techniques for the treatment of zygomatic fractures as compared to the Gillies method, i.e., the bone –hook elevation. Two studies examining large number of zygomatic fractures over a recent 10 years period reported treating approximately 80% of displaced zygomatic complex fractures with open reduction and internal fixation (Zingg et al. and Covington et al.) While the older literature reported about 50%. Rohrich and Wantumulla reinforced the study in a retrospective review of patients with zygomatic complex fractures treated by various methods of fixation at a large urban trauma center.

Knight and North described a classification system of zygoma fractures, hoping to better determine the prognosis and treatment of these injuries. Group I encompassed fractures with no significant displacement. While fracture lines may be evident on imaging, their recommendation was observation and soft diets.

Group II fractures include isolated arch fractures, fractures reduction is indicated when trismus or esthetic deformities are present. Unrotated body fractures, medially rotated body fractures, laterally rotated body fractures and complex fractures (defined as the presence of additional fracture lines across the main fragment) belong to groups III, IV, V and VI, respectively. Knight and North defined these groups by their stability after reduction. They found that 100% of the group IV and group V fractures were stable after a Gillies reduction, and no fixation was required. However, 100% of group IV, 40% of group III, and 70% of group VI were unstable after reduction and required some form of fixation.

A study by Pozatek et al. concurred with the findings of Knight and North except for group V fractures. This group was found to be unstable in 60% of cases. Lund found that all group III fractures were stable after reduction, disagreeing with the findings of Knight and North. It now seems apparent that displaced fractures require open reduction and fixation. In 1990, Manson and Colleagues proposed a method of classification based on the pattern of segmentation and displacement. Fractures that demonstrated little or no displacement were classified as low energy injuries. Incomplete fractures of one or more articulations may be present. Middle energy fractures demonstrated complete to moderate displacement comminution may be present. High energy injuries were characterized by comminution in the lateral orbit and lateral displacement with segmentation of zygomatic arch. Zingg and Colleagues, in a review of 1,025 zygomatic fractures, classified these injuries into three categories A, B, C. Type A fracture were incomplete low- energy fractures with fracture of only one zygomatic pillar: the zygomatic arch, lateral wall, or infraorbital rim. Type B: fracture were designated complete monofragment fractures with fracture and displacement along all four articulations. Type C multifragment fractures included fragment of the zygomatic body. Although all three notes as the amount of displacement and comminution increases the role of open reduction and internal fixation increases.

Conclusion

This study on zygomatic bone and zygomatic arch fractures showed that the majority of the patients were young adult men. Road traffic accidents were the leading cause of zygomatic bone and zygomatic arch fractures. According to the site of fracture, various modalities of treatment were used and all patients achieved satisfactory results without any complications after operation. My advice for management of zygomatic bone and zygomatic arch is as below:

The patient with zygomatic bone fracture should be treated early Early anatomic repair with stable reduction maximizes the functional and cosmetic results and rigid internal fixation optimizes this results.

The surgeon should take care of tissues during the management of fracture in order to ensure the best possible scar formation.

Bibliography

- 1.Balle V, Christensen PH. Treatment of zygomatic fractures: a follow-up study of 105 patients. Clin Otolaryngol. 1982;7(6):411–416. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2273.1982.tb01405.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bosniak Sl, Tizes Br. Trimalar fractures: diagnosis and treatment. Adv Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 1987;6:403–414. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Covington DS, Wainwrright DJ, Teichgraeber Jf, et al. Changing patterns in the epidemiology of zygoma fractures: 10 year review. J Trauma. 1994;37:243–248. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199408000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dingman Ro, Natvig P. Surgery of facial fractures. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1976. pp. 218–220. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Evans BG, Evans GR. MOC_PSSM CME article: zygomatic fractures. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;121(1 suppl):1–11. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000294655.16607.ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fasola AO, Nyako EA, Obiechina AE, et al. Trends in the characteristic of maxillofacial fractures in Nigeria. J Oral Maxillofacial Surg. 2003;61:1140–1143. doi: 10.1016/S0278-2391(03)00671-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Duman H, Zor F, Sengezer M. Hook elevation in reducing the isolated zygomatic arch fractures: is it really a simple and an effective method? Euro J Plast Surg. 2006;28:408–411. doi: 10.1007/s00238-005-0802-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kovacs AF, Ghahremani M. Minimization of zygomatic complex fracture treatment. J Maxillofac Surg. 2001;30:380. doi: 10.1054/ijom.2001.0131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Knight JS, North JF. The classification of malar fracture: analysis of displacement as a guide to treatment. Br J Plast Surg. 1961;13:325. doi: 10.1016/S0007-1226(60)80063-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kelley P, Hopper R, Gruss J (2007) Evaluation and treatment of zygomatic fractures. Plast reconstruct Surg 120 (7 suppl) 2: 5S–15S [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Kleuk G, Kovacs A. Etiology and pattern of facial fractures in the United Arab Emirates. J Craniofac Surg. 2003;14:78–84. doi: 10.1097/00001665-200301000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kovacs AF, Ghahremani M. Minimization of zygomatic complex fracture treatment. J Maxillofac Surg. 2001;30:380. doi: 10.1054/ijom.2001.0131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mahood S, Keith DJ, Lello GE. When can patients blow their nose and fly after treatment for fractures of zygomatic complex: the need for a consensus. Injury. 2003;34:908–911. doi: 10.1016/S0020-1383(03)00057-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Matsmedi MH. An assessment of maxillofacial fractures: a five–year study of 237 patients. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;61:61–64. doi: 10.1053/joms.2003.50049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nam IW. Clinical studies on treatment of fractures of zygomatic bone. Taehan chikkwa Uisa Hyophoe Chi. 1990;28:563–570. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rowe NL, Williams JL. Maxillo-facial injuries. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1994. pp. 473–491. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rajesh P, Rai AB. A Comparison between radiography and ultrasonography in the diagnosis of zygomatic arch fracture. Indian J Dent Res. 2003;14(2):75–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rodriguez-Vegas JM, Casado Perez C. Inexpensive custom-made external splint for isolated closed zygomatic arch fractures. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;113(5):1517–1518. doi: 10.1097/01.PRS.0000118255.77597.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Obuekwe O, Owotade F, Osaiyuwu O. Etiology and pattern of zygomatic complex fractures: a retrospective study. J Natl Med Assoc. 2005;97(7):992–996. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pozatelk ZW, Kaban LB. Fractures of zygomatic complex: an evaluation of surgical management with special emphasis on the eye brow approach. J Oral Surg. 1973;31:141–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Strong EB, Sykes JM. Zygoma complex fractures. Facial Plast Surg. 1998;14(1):105–115. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1085306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zingg M, Laedrach K, Chen J, et al. Classification and treatment of zygomatic fractures: a review of 1,025 cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1992;50(8):778–790. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(92)90266-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]