Abstract

The first theoretical structural model of newly reported Cry1Ab16 δ-endotoxin produced by Bacillus thuringiensis AC11 was predicted using homology modeling technique. Cry1Ab16 resembles the Cry1Aa protein structure by sharing a common three domains structure responsible in pore forming and specificity determination along with few structural deviations. The main differences between the two is in the length of loops, absence of α7b, α9a, α10b, α11a and presence of additional β12b, α13 components while α10a is spatially located at downstream position in Cry1Ab16. A better understanding of the 3D structure shall be helpful in the design of domain swapping and mutagenesis experiments aimed at improving toxicity.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s12088-011-0191-5) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Insecticidal crystal protein, Cry toxins, α-Helical bundle, Receptor insertion, Third-party annotation

Insecticidal crystal protein (ICP) produced by the soil bacterium Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) belongs to a large toxin family with a target spectrum spanning insects, nematodes, flatworm, protozoa and until now is considered harmless to mammals [1]. The mode of action of Cry toxins is still a matter of hypotheses; the Cry1A series of toxins are produced as inactive protoxins within Bt sporangia and after ingestion by a susceptible insect larva, protoxins are proteolytically cleaved to a core toxin fragment that binds to four different types of high affinity receptor sites on the insect gut membrane. Receptor binding phenomenon induces the conformational changes in the toxin necessary for its membrane insertion. The inserted toxin disturbs the cellular electrolyte balance by creating pores in the cell membrane, leading to cell lysis and finally to larval death [2, 3]. Crystal structures of the active toxins in solutions have been analyzed for Cry1Aa [4], Cry2A [5], Cry3A [6], Cry3B [7], Cry4Ba [8], and Cry4Aa [9] by X-ray diffraction crystallography and Cry11Bb [10], Cry5Aa [11], and Cry5Ba [12] has been predicted by homology modeling method. These reports have supported the three domains hypothesis [4] reveling domain I to be consisting of α-helical bundle, domain II of antiparallel β sheets and domain III made up of β sandwich. Hitherto Cry1 toxins have extensively used in studies of lepidopteron insect control and have attracted less attention and fewer efforts have been focused on Cry1Ab member’s structural studies. Since for a comprehensive understanding of mechanisms underlying toxicity it is imperative to have three-dimensional structural information of all the prevalent Cry family members. Here, a model for structure of the Cry1Ab16 toxin based on the hypothesis of structural similarity [4] is reported. This model shall provide further initiation into the domain-mutagenesis experiments among Cry toxins for improving their toxicity.

Materials and Methods

The model coordinates were developed essentially by generating alignments among target sequence (AAK 55546) with existing PDB entries. Alignment of those structure sequence that showed amino acid and secondary structure similarity where directly used in homology modeling program MODELLER 9VB [13]. The resulted preliminary model was validated with PROCHECK [http://nihserver.mbi.ucla.edu/SAVES/Info.php], WHAATIF [http://swift.cmbi.ru.nl/servers/html/index.html] ProSA [https://prosa.services.came.sbg.ac.at] and RAMPAGE [http://mordred.bioc.cam.ac.uk/] servers. Possible outliers and side chains static constrain were minimized by refining the model with Summa’s server [http://silvio.cs.uno.edu/proteinrefinementserver/]. Potential deviations were calculated with SUPERPOSE web server (http://wishart.biology.ualberta.ca/cgi-bin/) for root mean square deviation (RMSD).

Results and Discussion

The structural model of the Cry1Ab16 core toxin was obtained comprising of 605 (68–673) amino acids out of 1155 long primary structure. As a general practice using multiple template alignment in modeling information is preferred to avoid biased folding and generation of atomic clashes and highly strained bond length and angles in target molecule. The secondary structure based alignment of each domain (I, II and III) found to be reliable and few manual corrections are to be incorporated within the possible limits of flanking domains to adjust the gaps and aligning the conserved block elements. The sequence identity for each template and their sequence alignment is shown in Table 1 and Figs. 1 and 2.

Table 1.

The percentage identity score of Cry1Ab16 sequence verses Cry1Aa (1ciy:A); Cry3Aa (1dlc:A); Cry8ea1 (2qkg:A). The comparative scores were read out of secondary structure alignments using SAS software (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/thornton-srv/databases/cgi-bin/sas)

| Sl no. | Smith–Waterman Score | % identity | a.a. overlap | Seq. length | Z-score | E value | PDB code | Protein name |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | – | – | – | 606 | – | – | – | Cry 1Ab16 |

| 2. | 3337 | 87.8 | 580 | 577 | 4015.0 | 7.9e-217 | 1ciy:A | Cry 1Ab1 |

| 3. | 1254 | 36.4 | 563 | 584 | 1500.3 | 9.2e-77 | 1dlc:A | Cry 3Aa |

| 4. | 1305 | 38.0 | 600 | 589 | 1438.8 | 2.5e-73 | 2qkg:A | Cry8ea1 |

| 5. | 1150 | 34.7 | 585 | 589 | 1296.6 | 2e-65 | 1ji6:A | Cry3bb1 |

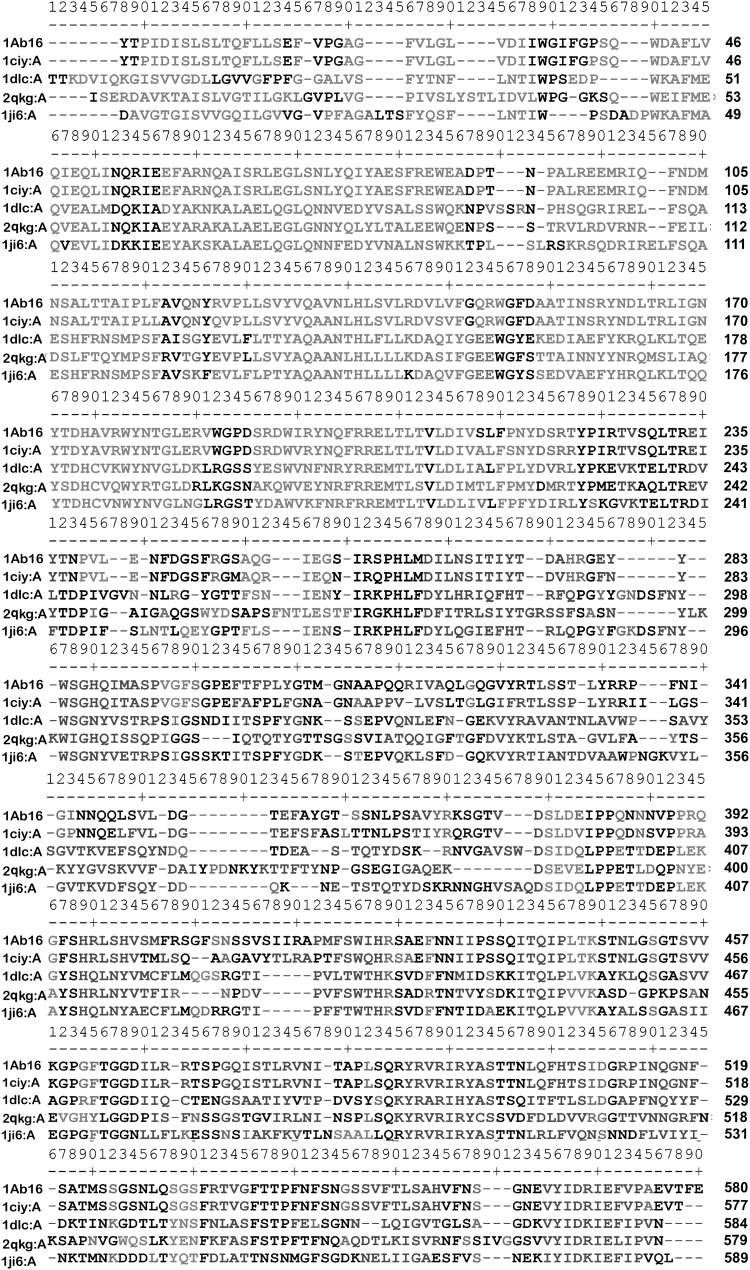

Fig. 1.

Amino acid sequence alignment of the Cry1Ab16 including those of genuine δ endotoxins. The sequence displayed are from Cry1Aa (1ciy:A); Cry3Aa (1dlc:A); Cry8ea1 (2qkg:A); Cry3bb1 (1ji6:A). All sequences were obtained from PDB database. The sequential number above represents the number of amino acids. The residues highlighted in red color represent helix; those in blue represent strand; in green represent turn; and those in black represent coil and are generated using SAS software (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/thornton-srv/databases/cgi-bin/sas)

Fig. 2.

The two-dimensional structure annotation showing sequential arrangements of helices and sheets in Cry1Ab16 toxin molecule using the PDB sum (www.ebi.ac.uk/pdbsum/)

The validation of model for artifacts and errors is evaluated with webs based PROCHECK and WHATIF. Another program, ProSA evaluates the model by parsing its coördinates and energy using a distance based pair potential by capturing the solvent exposed protein residues. This program consists of sufficiently large database of natural structures, which it deploys in the validation of experimental and computational models [14]. The results are displayed in form of Z-score and plot of residues energy. The Z-score shows overall model quality and provides deviations from the random conformation. It also checks whether the Z-score of the protein is within the range of similar proteins (NMR and X-ray derived structures). Result in Fig. 3a shows the plot location of the Z-score. The value −10.09 is among native conformation and overall residues energy of developed structure is found to be largely negative. The Ramachandran plot showed that most of the residues (~91.2%) have Φ and Ψ angles in the favored regions and additionally ~7.1% is in allowed region, still some proline and glycine residues (1.7%) fall in outlier region (Fig. 3b). Most bond lengths, bond angles, and torsion angles were among values expect for a naturally folded protein. Structural comparison of the Cry1Aa toxin with the Cry1Ab16 model shows correspondence with the general Cry toxin model (a α + β structure with three domains, Fig. 3a) and their superimposed Cα backbone traces showed low RMSD (1.14Ǻ). This low value show that final developed structure is similar to Cry1Aa (Fig. 4a). This condition is anticipated since both the sequence has a high homology. The few differences observed between them were in length of the loops of domains II and III absence of α7b, α9a, α10b, α11a and presence of additional β12b, α13 components. The component α10a is located spatially at different position (Table 2). This RMSD after optimal superposition between model and the native structure is frequently used as a means of correctness determination, In general the accuracy of the backbone trace of structure model has a profound impact on the ability to accurately predict near natural state of protein structure, including the side chain placement and later refining it into natural state like protein structure [15].

Fig. 3.

Evaluation of Cry1Ab16 model a on ProSA server. The plot indicating nearness of developed model with the native structures. The Z-score of evaluated model is shown as large black dot. b Ramachandren plot analysis showing placement of its residues in deduced model. General plot statistics are: 551 (91.2%) residues in favored regions; 43 (7.2%) of residues were in allowed regions; the outlier residues totals to 10 (1.7%) only. The plot was generated using RAMPAGE web server (http://mordred.bioc.cam.ac.uk/)

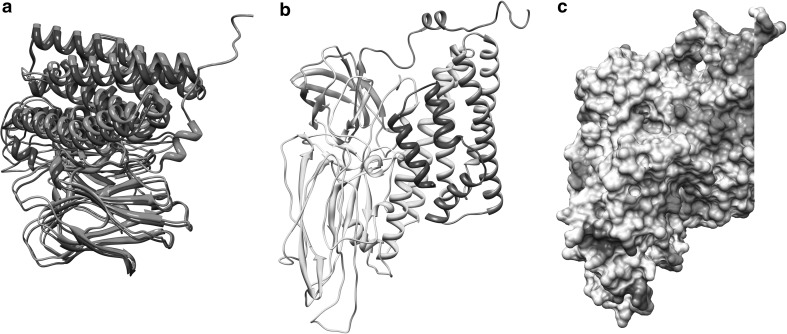

Fig. 4.

Complete protomer structure of the Cry1Ab16 toxin. a Superposition Cα backbone of Cry1Aa1 (blue) and Cry1Ab16 (pink) molecules. Images are generated using UCF chimera (http://www.cgl.ucsf.edu/chimera). b Ribbon diagram showing three-dimensional three domain oligomer structure. c Surface electrostatic potential representation of Cry1Ab16 toxin

Table 2.

The comparison among three domain structural components of Cry1Aa (1ciy:A) and Cry1Ab16 toxin molecules

| Cry1Aa | Cry1Ab16 | Cry1Aa | Cry1Ab16 | Cry1Aa | Cry1Ab16 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Domain I | Domain II | Domain III | ||||||

| α1 | Pro35–Ser48 | Pro70–Ser83 | α8a | Pro271–Glu274 | Pro306–Asn310 | α11a | Leu475–Lys477 | – |

| α2a | Aln54–Ile63 | Aln89–Trp100 | α8b | Ala284–Gln289 | Ser318–Ser325 | β13a | Ser486–Val488 | Ser522–Val524 |

| α2b | Pro70–Ile84 | Pro105–Gly119 | β2 | Asp298–His310 | Ile334–His341 | β13b | Ile498–Arg 501 | Ile534–Arg 537 |

| α3 | Glu90–Ala119 | Arg128–Ala154 | β3 | Phe313–Trp316 | Glu343–His345 | β14 | Gly505–Asn513 | Gly541–Asn549 |

| α4 | Pro124–Leu148 | Pro159–Phe183 | β4 | Gly318–Pro325 | Glu348–Leu418 | β15 | Tyr522–Ser530 | Tyr558–Ser566 |

| α5 | Gln154–Trp182 | Arg189–Trp217 | α9a | Val326–Phe328 | – | β16 | Leu534–Ile540 | Leu570–Ile576 |

| α6 | Ala186–Val218 | Ala221–Val253 | β5 | Val348–Ser351 | Gly353–Ser359 | β17 | Arg543–Phe550 | Arg579–Phe586 |

| α7a | Ser223–Thr239 | Ser258–Tyr285 | β6 | Ile357–Arg367 | Arg384–Ala387 | α12a | Ser562–Ser564 | Ser598–Ser600 |

| α7b | Leu241–Tyr250 | – | β7 | Leu380–Leu383 | Tyr394–Leu401 | β18 | Arg566–Gly569 | Arg602–Gly605 |

| β1a | Glu266–Thr269 | Ile302–Thr304 | β8 | Gly385–Phe390 | Val417–Ala424 | β19 | Ser580–His588 | Ser616–His624 |

| β9 | Thr400–Tyr402 | Ala434–Tyr436 | β20 | Val569–Pro605 | Val632–Pro641 | |||

| α10a | Ser410–Asp412 | Ser441–Glu447a | α13 | – | Leu652–Ala658 | |||

| α10b | Pro423–Gly426 | – | ||||||

| β10 | His429–Val434 | His463–Met470 | ||||||

| β11 | Phe452–His456 | Pro486–His492 | ||||||

| β12a | Thr471–Pro474 | Thr507–Pro510 | ||||||

| β12b | – | Thr515–Leu517 | ||||||

– Similar component not present

aComponents in italics are spatially present at downstream sites

Domain I is composed of N terminal 234 (70–304) amino acid residues folded into a bundle of amphipathic helices and consist of nine α-helices and two small β-strands (Fig. 4b). This feature is believed to be highly conserved among the Cry toxins [4] and it has been proposed that it is involved in ‘pore-formation’ analogy with the helical bundle pore forming structures of colicin A toxin [16] and diphtheria toxin [17]. Evidence from several studies has shown that the central helix (α5) is specifically involved in the ‘pore’ formation process [18, 19].

As like other Cry toxins, domain II of the Cry1Ab16 toxin, consists of three Greek key anti parallel β sheets arranged in a β prism topology, each one ending in exposed loop regions. It is comprised by residues 306–517(Fig. 4), one helix and 11 β-strands. These loops are thought to participate in receptor binding and hence in determining the specificity of the toxin. Ge et al. [20] managed to alter toxicity in Cry1Ac by exchanging the 332–450 amino acids in domain II with equivalent segment in Cry1Aa. A similar approach is still to be done in Cry1Ab16.

Domain III composed of residues 522–658 and showed highly conserved residues. Calculation of amphiphilicity with the Hoops and Woods value, indicated that α1, α2 (a & b), α3, α6, are well exposed and available for interaction, but helix α1 seems to be packed with domain II. This condition of α1 may cause it to show certain degree of displacement in post receptor binding phenomenon [21]. The possibility of regions outside domain II being involved in receptor recognition was evaluated by mutagenesis study in domain III loop of Cry1Ac [22].

The Coulombic surface charge distribution pattern in the model corresponds to negatively charged patch along β4 and β13 of domains II and III (Fig. 4c). While data of Gazit et al. [23] relates well with domain I, who initially suggested that α4 and α5 insert into the lumen receptor in an antiparallel helical hairpin manner. It is possible that according to the surface electrostatic potential of helices 4 and 5, there is a neutral region in the middle of the helices which shows, if the umbrella model is correct that both helices cross the membrane with their polar sides exposed to the solvent, as it has been suggested by the results of mutagenesis experiments in case of the Cry1Ac toxin [23].

Kumar and Aronson [24] demonstrated that mutation in the base of helix 3 and the loop between α3 and α4 that cause alterations on the balance of negative charged residues may cause loss of toxicity. Mutations in helices α2, α6 and the surface residues of α3 have no important effect on toxicity; meanwhile, helices α4 and α5 seem to be very sensitive to mutations. Helix α1 probably does not play an important part in toxin activity after cleavage of the protoxin. It is possible that mutations aimed to an increase in amphilicity in these helices will improve the pore forming activity of Cry1Ab type of toxins. Also, chemical modifications of four Arg or seven Tyr residues resulted in greatly reduced toxicity and binding in Cry1A toxin [25].

It is presumed that additional and dislocated components may have some implications in specificity of the Cry1Ab16 toxin. Mutations in defined regions of the Cry1Aa toxin have been identified (equivalent to residues in the β6-β7 loop of Cry1Ab16), as essential for binding to the membrane of midgut cells of Bombyx mori [20, 26]. In the Cry1Ab16 model, this region is longer than their counterparts. Loop β2-β3 seems also to be able to modulate the toxicity and specificity in Cry1C [27]. The dual specificity of Cry2Aa for Lepidoptera and Diptera has been mapped to residues that correspond in the Cry1Ab16 theoretical model to α sheet 1, strand β6, and loop between β6 and β7. This loop probably interacts with the receptor through both hydrophobic and electrostatic interactions; that probably also helps in receptor binding by providing more mobility to glycine and other like residues that may interact through salt bridges with the receptor.

Loop β4–β5 is hydrophilic, and the charged residues at the tip of the loop are probably important determinants of insect specificity. Presence of aromatic amino acids within and adjoining vicinity of apical loops 2 and 3 of domain II has been postulated for protein–protein, protein–legend interactions and have been reported to tend to interact specifically with the outer envelope of lipid membrane [28] these residues were proposed to interact with hydrophobic lipids tails. The exposed loop architecture has structural affinity for binding to a glycoprotein receptors of the target insect membrane [29]. Several studies in Cry1Ac [4] and Cry1Aa [30, 31] showed that mutation in conserved block residues led to decreased toxicity and alter channel properties. Similar alterations in case of Cry1Ab16 of conserved block residues may also causes altered toxin properties.

Finally, evidence presented here, based on the identification of structural equivalent residues of Cry1Ab16 toxin through homology modeling show that, due to high amino acid homology, absence and presence of structural components few of which are at different positions, Cry1Ab16 shares a common three-dimensional structure. This is the first model of a Cry1Ab16 protein and major challenge still is for its crystallization and verification of predicted structural variations.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgment

The author is grateful to ICAR for RAship. Infrastructure, computational facility and encouragements by Director of NBAIM are duly acknowledged.

References

- 1.Schnepf E, Crickmore N, Rie J, Lereclus D, Baum J, Feitelson J, Zeigler DR, Dean DH. Bacillus thuringiensis and its pesticidal crystal proteins. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62:772–806. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.3.775-806.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hofmann C, Vanderbruggen H, Hofte H, Rie J, Jansens S, Mellaert H. Specificity of Bacillus thuringiensis delta-endotoxins is correlated with the presence of high-affinity binding sites in the brush border membrane of target insect midgets. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:7844–7848. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.21.7844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Knowles BH, Ellar DJ. Colloid osmotic lysis is a general feature of the mechanism of action of Bacillus thuringiensis delta-endotoxins with different insect specificities. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1987;924:509–518. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(87)90167-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grochulski P, Masson L, Borisova S, Pusztai-Carey M, Schwartz JL, Brousseau R, Cygler M. Bacillus thuringiensisCryIA(a) insecticidal toxin: crystal structure and channel formation. J Mol Biol. 1995;254:447–464. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morse RJ, Yamamoto T, Stroud RM. Structure of Cry2Aa suggests an unexpected receptor binding epitope. Structure. 2001;9:409–417. doi: 10.1016/S0969-2126(01)00601-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li J, Carroll J, Ellar DJ. Crystal structures of insecticidal δ-endotoxin from Bacillus thuringiensis at 2.5 Å resolution. Nature. 1991;353:815–821. doi: 10.1038/353815a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Galitsky N, Cody V, Wojtczak A, Ghosh D, Luft JR, Pangborn W, English L. Structure of the insecticidal bacterial endotoxin Cry3Bb1 of Bacillus thuringiensis. Acta Crystallogr Sect D. 2001;57:1101–1109. doi: 10.1107/S0907444901008186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boonserm P, Davis P, Ellar DJ, Li J. Crystal structure of the mosquito-larvicidal toxin Cry4Ba and its biological implications. J Mol Biol. 2005;348(2):363–382. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boonserm P, Mo M, Angsuthanasombat C, Lescar J. Structure of the functional form of the mosquito larvicidal Cry4Aa toxin from Bacillus thuringiensis at a 2.8 Angstrom Resolution. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:3391–3401. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.9.3391-3401.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gutierrez P, Alzate O, Orduz SA. Theoretical model of the tridimensional structure of Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. medellin Cry11Bb toxin deduced by homology modeling. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2001;96:357–364. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762001000300013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Min ZX, Qui XL, Zhi DX, Xiang WF. The theoretical three-dimensional structure of Bacillus thuringiensis Cry5Aa and its biological implications. Protein J. 2009;28:104–110. doi: 10.1007/s10930-009-9169-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xia LQ, Zhao XM, Ding XZ, Wang FX, Sun YJ. The theoretical 3D structure of Bacillus thuringiensis Cry5Ba. J Mol Model. 2008;14:843–848. doi: 10.1007/s00894-008-0318-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sali A, Potterton L, Yuan F, Vlijmen H, Karplus M. Evaluation of comparative protein modeling by MODELLER. Proteins. 1995;23:318–326. doi: 10.1002/prot.340230306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wiederstein M, Sippl MJ. ProSA-web: interactive web service for the recognition of errors in three-dimensional structures of proteins. Nucleic Acid Res. 2007;35:407–410. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wallner B, Elofsson A. Identification of correct regions in protein models using structural, alinement and consensus information. Protein Sci. 2006;15:900–913. doi: 10.1110/ps.051799606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parker MW, Pattus F, Tucker AD, Tsernoglou D. Structure of the membrane-pore-forming fragment of colicin A. Nature. 1989;337:93–96. doi: 10.1038/337093a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Choe S, Bennett MJ, Fujii G, Curmi PMG, Kantardjieff KA, Collier RJ, Eisenberg D. The crystal structure of diphtheria toxin. Nature. 1992;357:216–222. doi: 10.1038/357216a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu D, Aronson AI. Localised mutagenesis defines regions of the Bacillus thuringiensis δ-endotoxin involved in toxicity and specificity. J Biol Chem. 1992;26:2311–2317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gazit E, Shai Y. Structural and functional characterization of the α5 segment of Bacillus thuringiensis δ-endotoxin. Biochemistry. 1993;32:3429–3436. doi: 10.1021/bi00064a029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ge AZ, Sivarova NI, Dean DH. Location of the Bombyx mori specificity domain of Bacillus thuringiensis δ-endotoxin protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:4037–4041. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.11.4037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Segura C, Guzman F, Patarroyo ME, Orduz S. Activation pattern and toxicity of the Cry1Ab17Bb toxin of Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. Medellin. J Invertebr Pathol. 2000;76:56–62. doi: 10.1006/jipa.2000.4945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aronson AI, Wu D, Zhang C. Mutagenesis of specificity and toxicity regions of a Bacillus thuringiensis protoxin gene. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:4059–4065. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.14.4059-4065.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gazit E, La Rocca P, Sansom MSP, Shai Y. The structure and organization within the membrane of the helices composing the pore forming domain of Bacillus thuringiensis δ-endotoxin are consistent with an “umbrella-like” structure of the pore. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:12289–12294. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.21.12289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kumar ASM, Aronson AI. Analysis of mutations in the pore-forming region essential for insecticidal activity of a Bacillus thuringiensis δ-endotoxin. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:6103–6107. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.19.6103-6107.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cumming CE, Ellar DJ. Chemical modification of Bacillus thuringiensis activated δ-endotoxin and its effect on toxicity and binding to Manduca sexta midgut membranes. Microbiol. 1994;140:2737–2747. doi: 10.1099/00221287-140-10-2737. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lu H, Rajamohan F, Dean DH. Identification of amino acid residues of Bacillus thuringiensis δ-endotoxin CryIA(a) associated with membrane binding and toxicity to Bombyx mori. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:5554–5559. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.17.5554-5559.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smith GP, Ellar DJ. Mutagenesis of two surface exposed loops of the Bacillus thuringiensis CryIC δ-endotoxin affects insecticidal specificity. Biochem J. 1994;302:611–616. doi: 10.1042/bj3020611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bressanelli S, Stiasny K, Allison SL, Stura EA, Duquerroy S, Lescar J, Heinz FX, Rey FA. Structure of a flavivirus envelope glycoprotein in its low-pH-induced membrane fusion conformation. EMBO J. 2004;23:728–738. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Griffitts JS, Haslam SM, Yang T, Garczynski SF, Mulloy B, Morris H, Cremer PS, Dell A, Adang MJ, Aroian RV. Glycolipids as receptors for Bacillus thuringiensis crystal toxin. Science. 2005;307:922–925. doi: 10.1126/science.1104444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen XJ, Lee MK, Dean DH. Site-directed mutations in a highly conserved region of Bacillus thuringiensis δ-endotoxin affect inhibition of short circuit current across Bombyx mori midgets. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:9041–9045. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.19.9041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schwartz JL, Potvin L, Chen XJ, Brousseau R, Laprade R, Dean DH. Single-site mutations in the conserved alternating-arginine region affect ion channels formed by CryIAa, a Bacillus thuringiensis toxin. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:3978–3984. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.10.3978-3984.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.