Abstract

Background

Functional dyspepsia (FD) is a heterogeneous disease, and categorized into postprandial distress syndrome (PDS) and epigastric pain syndrome (EPS). However, many FD patients have overlap of both PDS and EPS. The present study was designed to examine whether FD could be categorized based on the presence of concomitant gastrointestinal symptoms.

Methods

A web survey comprised of the Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale (GSRS), Rome III criteria of FD, and demographic information was sent to public participants who have no history of severe illness. Factor and cluster analyses were conducted to identify sub-categories of FD based on GSRS.

Key Results

A total of 8038 participants completed the survey. A total of 563 participants met the criteria for FD, whereas 6635 participants did not have dyspepsia symptoms. The remainder had either organic disease (377) or uninvestigated dyspepsia (463). The cluster analysis categorized participants as constipation predominant (cluster C), diarrhea predominant (cluster D), or having neither diarrhea nor constipation (cluster nCnD). Cluster C and D were significantly associated with the presence of FD [odds ratio (OR) 2.57, 95% confidence interval (CI) 2.06–3.21; OR 2.80; 95% CI 2.27–3.45, respectively]. In FD, especially in PDS cases, the scores of upper gastrointestinal symptoms were higher in cluster C or D than in cluster nCnD.

Conclusions & Inferences

The severity of dyspepsia symptoms is associated with the presence of bowel symptoms especially in PDS. This novel categorization of FD based on concomitant constipation or diarrhea may improve classification of patients.

Keywords: cluster analysis, constipation, diarrhea, dyspepsia, factor analysis

INTRODUCTION

Functional dyspepsia (FD) is a common clinical syndrome characterized by chronic and recurrent gastroduodenal symptoms in the absence of any organic or metabolic disease that is likely to explain the symptoms.1,2 FD is a heterogeneous condition consisting of different subgroups. According to Rome III criteria of FD, FD is divided into two subgroups: postprandial distress syndrome (PDS) and epigastric pain syndrome (EPS), to distinguish between meal-induced symptoms and meal-unrelated symptoms believed to be pathophysiologically and clinically relevant.1,3 Although it has been postulated that symptom subgroups could be used to identify more homogenous subgroups that would respond to targeted medical therapy, up to half of FD patients have overlap of both PDS and EPS.4 In addition, to the best of our knowledge, there is no evidence that PDS or EPS should be treated differently.

Overlap among functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGIDs) is extremely common. Specifically, dyspepsia and bowel symptoms, such as diarrhea and constipation, often coexist.5 A recent meta-analysis reported that the prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) among participants of dyspepsia was 37% compared with 7% in those without dyspepsia.6 In addition, the prevalence of esophageal symptoms, such as heartburn, is also high in FD patients, although esophageal reflux symptoms may co-exist, but are not consider typical FD symptoms in the Rome III criteria.1 Savarino et al.7 showed that patients with functional heartburn had more frequent postprandial fullness, bloating, early satiety, and nausea than patients with non-erosive reflux disease (NERD). These recent studies reinforce the concept that FGIDs extend beyond the boundaries suggested by the anatomical location of symptoms.

Although subclasses of FD based on symptom clusters have been proposed,1,8 subclustering based on bowel symptoms or esophageal symptoms has not been investigated. The aim of this study was to use factor and cluster analyses to determine whether FD could be characterized based on the presence of concomitant other gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms, including bowel symptoms and esophageal symptoms.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study participants

The protocol for this study was approved by the ethics committee of Tokyo Ekimae Building Clinic (TEC-0801, September 24, 2008). We conducted a web-based cross-sectional study. Participants were solicited from a list of public participants who are invited previously to participate in the clinical studies conducted by the Tokyo Ekimae Building Clinic with informed consent. No participants in the list have a severe chronic or life-threating illness such as malignancy or systemic autoimmune diseases, and a serious mental illness, such as major depression or schizophrenia. Participants who used prescribed medicines or over-the-counter (OTC) drugs were not excluded from the present study. The questionnaires were comprised of items including the Japanese version of the Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale (GSRS)9 and the Rome III criteria of FD;1 in addition, prior receipt of upper GI screening examination was elicited. If either of the latter two were identified, the presence/absence of structural disease was also abstracted. The Japanese version of GSRS questionnaire is a validated, self-administered questionnaire that includes 15 questions, which assess severity of GI symptoms, including esophageal reflux symptoms, dyspepsia symptoms, and bowel symptoms, using a 7-point Likert scale.10 Demographic information, such as age, gender, smoking habit, alcohol habit, height, and weight, were also obtained, and body mass index (BMI) (weight height−2) was calculated. Smoking was categorized into ‘none’, ‘light’ (1–15 cigarettes day−1), and ‘heavy’ (>16 cigarettes day−1) according to a number of cigarettes consumed per day. Alcohol intake was also categorized into ‘none’, ‘light’ (1–3 days week−1), and ‘heavy’ (4–7 days week−1) according to a number of days of alcohol consumption per week.

Definition of FD cases and non-dyspepsia controls

Based on Rome III criteria, participants were defined as having dyspepsia when they have one or more of symptoms, such as postprandial fullness, early satiation, or epigastric pain or burning for at least 6 months prior to the survey. Participants without dyspepsia symptoms were defined as a ‘non-dyspepsia’ control group. Participants with dyspepsia who had undergone the upper GI examination and had no evidence of structural disease in the stomach and duodenum were defined as ‘FD’ cases. Participants with dyspepsia who had not undergone upper GI examination were classified as ‘uninvestigated dyspepsia’. Participants with dyspepsia who had undergone upper GI examination and had structural disease were classified as ‘organic disease’ patients.

The FD subjects with postprandial fullness or early satiation were defined as those with PDS, whereas FD subjects with epigastric pain or burning were defined as those with epigastric pain syndrome (EPS). Using these definitions, FD subjects were subcategorized into three groups as follows: subjects with PDS alone, subjects with EPS alone, and subjects with both PDS and EPS.

Statistical analysis

Exploratory factor analysis was conducted in all web responders to identify the latent pathologic conditions, named ‘symptom factors’, and to reduce the dimensionality of subsequent analyses. Principal factor method with Varimax rotation was used. Subsequently, a non-hierarchical k-means cluster analysis for a three-cluster solution was performed using the symptom factor scores derived from the preceding factor analysis. Three ‘symptom clusters’ were extracted. The differences in the prevalence of FD between three symptom clusters were evaluated using univariable and multivariable logistic regression. In the multivariable model, age, gender, smoking, alcohol use, and BMI were included. The differences of the symptom factor scores between three symptom clusters in FD cases were examined using one-way anova and Tukey’s post hoc analysis. The differences of life-style characteristics between three symptom clusters were examined for each gender separately, as participant characteristics were significantly different between men and women. The differences between the three symptom clusters in age and BMI were examined using one-way anova and Tukey’s post hoc analysis. The differences between the three symptom clusters in smoking and alcohol habits were examined using Fisher’s exact test.

All statistical analyses were conducted using the spss Statistics version 18.0 for Windows software (SPSS Japan, Tokyo, Japan; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The data in the tables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Two-sided P-values were considered as statistically significant at a level of 0.05.

RESULTS

Participant characteristics

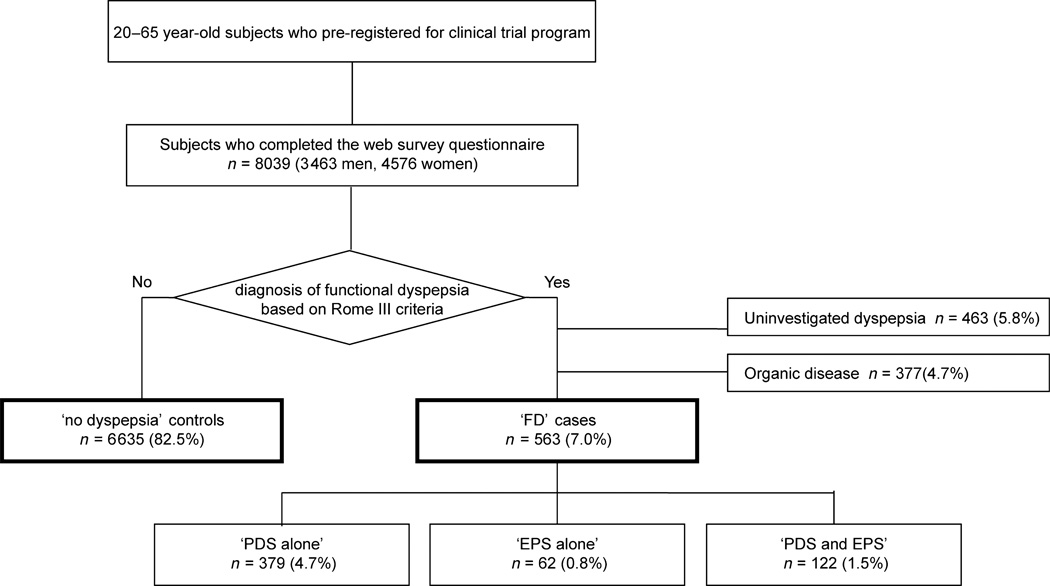

A total of 8038 participants (3462 men and 4576 women; mean age 40.8 ± 9.7 years) completed the questionnaire. A total of 563 participants were defined as FD cases, whereas 6635 participants without dyspepsia symptoms were identified as non-dyspepsia controls. A total of 463 participants were classified as uninvestigated dyspepsia, and 377 had organic disease (Fig. 1). Participant characteristics are shown in Table 1. Mean age was higher in FD cases than in non-dyspepsia controls. There was greater proportion of women among FD cases than among non-dyspepsia controls. Alcohol consumption and smoking was greater in FD than in non-dyspepsia. BMI was lower in FD than in non-dyspepsia. BMI was especially lower in ‘PDS alone’ group (22.1 ± 3.7 kg m−2) than in non-dyspepsia (22.7 ± 3.9 kg m−2, P = 0.003). This suggests that participants with PDS alone may avoid food because it precipitates their symptoms.

Figure 1.

The study population.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics

| All (n = 8038) |

Non-dyspepsia (n = 6635) |

FD (n = 563) |

Uninvestigated dyspepsia (n = 463) |

Organic disease (n = 377) |

P value (non-dyspepsia vs FD) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||||

| Mean ± SD (years) (Mean ± SD) | 40.8 ± 9.7 | 40.9 ± 9.8 | 42.8 ± 7.8 | 34.4 ± 9.0 | 44.0 ± 8.7 | <0.001* |

| 20–29 [No. (%)] | 1028 | 842 (12.7) | 21 (3.7) | 148 (32.0) | 17 (4.5) | |

| 30–39 [No. (%)] | 2639 | 2183 (32.9) | 157 (27.9) | 199 (43.0) | 100 (26.5) | |

| 40–49 [No. (%)] | 2894 | 2372 (35.7) | 282 (50.1) | 80 (17.3) | 160 (42.4) | |

| 50–59 [No. (%)] | 1201 | 999 (15.1) | 90 (16.0) | 33 (7.1) | 79 (21.0) | |

| 60–65 [No. (%)] | 276 | 239 (3.6) | 13 (2.3) | 3 (0.6) | 21 (5.6) | |

| Gender [No. (%)] | ||||||

| Men | 3462 | 2920 (44.0) | 228 (40.5) | 142 (30.7) | 172 (45.6) | 0.111† |

| Women | 4576 | 3715 (56.0) | 335 (59.5) | 321 (69.3) | 205 (54.4) | |

| Smoking habit [No. (%)] (number of consumptions per day) | ||||||

| None (0) | 5924 | 4947 (74.6) | 392 (69.6) | 332 (71.7) | 253 (67.1) | 0.037† |

| Light (1–15) | 1062 | 848 (12.8) | 85 (15.1) | 74 (16.0) | 55 (14.6) | |

| Heavy (>16) | 1052 | 840 (12.7) | 86 (15.3) | 57 (12.3) | 69 (18.3) | |

| Alcohol habit [No. (%)] (number of days of consumption per week) | ||||||

| None (0) | 2743 | 2281 (34.4) | 181 (32.1) | 159 (34.3) | 122 (32.4) | <0.001 |

| Light (1–3) | 2956 | 2482 (37.4) | 178 (31.6) | 186 (40.2) | 110 (29.2) | |

| Heavy (4–7) | 2339 | 1872 (28.2) | 204 (36.2) | 118 (25.5) | 145 (38.5) | |

| BMI (kg m−2) (Mean ± SD) | 22.6 ± 3.9 | 22.7 ± 3.9 | 22.2 ± 3.8 | 21.7 ± 3.9 | 22.6 ± 4.5 | 0.008* |

BMI, body mass index; FD, functional dyspepsia.

Analyzed by unpaired Student’s t-test.

Analyzed by Pearson’s Chi-squared test.

The differences between FD cases and non-dyspepsia controls in the average scores of the 15 GI symptom assessed by GSRS were compared using unpaired Student’s t-test. All of the 15 GI symptoms were significantly more severe in FD cases than in non-dyspepsia controls (See Table S1 online). Scores in participants with uninvestigated dyspepsia or organic disease were also higher than in non-dyspepsia. These results showed that not only upper GI symptoms, but also bowel symptoms and esophageal symptoms were more severe in participants with dyspepsia.

Factor analysis

Factor analysis revealed that the 15 items could be reduced to three GI symptom factors, namely factor EGD (esophagogastroduodenal symptoms), factor C (constipation), and factor D (diarrhea) (Table 2). Factor EGD mainly reflects the severity of upper GI symptoms, such as heartburn, abdominal pains, and abdominal distension. Factor C reflects constipation-related symptoms. Factor D reflects diarrhea-related symptoms.

Table 2.

Factor loading of the severity of 15 gastrointestinal symptoms (n = 8038)

| Factor EGD |

Factor C | Factor D | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heartburn | 0.718 | 0.139 | 0.132 |

| Acid regurgitation | 0.701 | 0.092 | 0.165 |

| Abdominal pains | 0.681 | 0.157 | 0.150 |

| Sucking sensations in the epigastrium | 0.651 | 0.200 | 0.166 |

| Nausea and vomiting | 0.591 | 0.169 | 0.228 |

| Abdominal distension | 0.555 | 0.335 | 0.181 |

| Eructation | 0.498 | 0.233 | 0.218 |

| Borborygmus | 0.396 | 0.314 | 0.276 |

| Increased flatus | 0.306 | 0.399 | 0.280 |

| Feeling of incomplete evacuation | 0.251 | 0.624 | 0.307 |

| Urgent need for defecation | 0.237 | 0.192 | 0.668 |

| Increased passage of stools | 0.227 | 0.064 | 0.835 |

| Loose stools | 0.209 | 0.088 | 0.818 |

| Hard stools | 0.188 | 0.772 | 0.047 |

| Decreased passage of stools | 0.161 | 0.820 | 0.010 |

Bold values indicate the loading values of higher than 0.5 for each symptom factor.

Factor EGD: the severity of upper gastrointestinal symptoms.

Factor C: the severity of constipation-related symptoms.

Factor D: the severity of diarrhea-related symptoms.

To examine potential associations between demographic factors (exposure variables) and the three symptom factors (outcome variables), linear regression analyses were performed (See Table S2 online). Younger age was associated with increased scores of all three symptom factors. Factor EGD and factor C scores were greater in women, whereas factor D scores were greater in men. Smoking was associated with factor EGD score in a dose-dependent manner. Heavy smoking was also associated with factor D score. Heavy alcohol consumption positively associated with factor EGD and factor D scores; conversely it was inversely correlated with factor C score. BMI was inversely associated with factor C score.

Cluster analysis

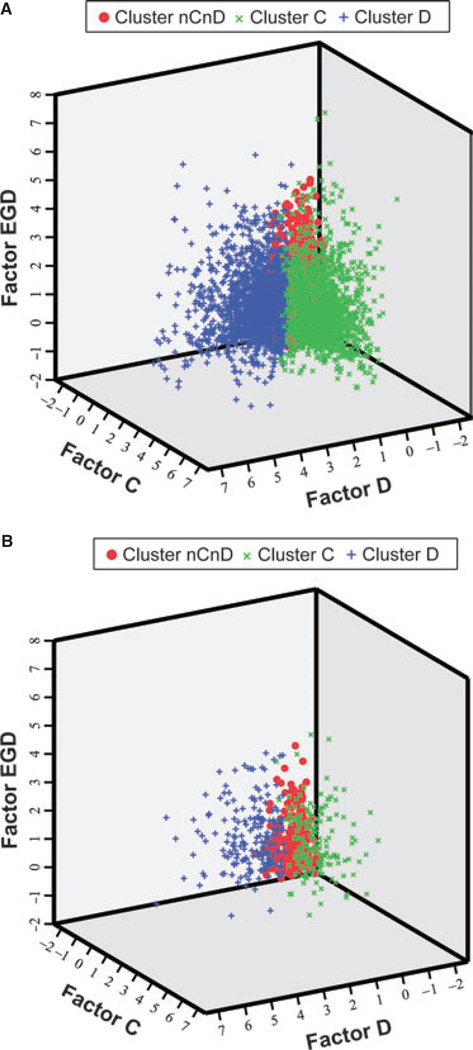

Cluster analysis based on the three symptom factor scores showed that FGIDs could be categorized into three clusters, namely cluster nCnD (non-constipation and non-diarrhea), cluster C (constipation), and cluster D (diarrhea). Cluster C was characterized by high scores of factor C (factor EGD 0.31; factor C 1.31; factor D −0.38). Cluster D was characterized by high scores of factor D (factor EGD 0.28; factor C −0.08; factor D 1.34). Cluster nCnD was not associated with any of the three symptom factors (factor EGD −0.22; factor C −0.43; factor D −0.39). The scores of the three symptom factors are plotted on the 3D coordinate systems to illustrate the distribution of three clusters in Fig. 2.

Figure 2.

Distribution of cluster nCnD, cluster C, and cluster D. The 3D spatial distribution of overall 8038 participants (A) and 563 functional dyspepsia participants (B) with three symptom factor scores derived from factor analysis showed that the three symptom clusters were well separated.

Based on the result of cluster analysis, FD cases and non-dyspepsia controls could be categorized into three clusters. Among 6635 non-dyspepsia controls, 4101 (61.8%) were categorized to cluster nCnD, 1218 (18.4%) were to cluster C, and 1316 (19.8%) were to cluster D. On the other hand, among 563 FD cases, 217 (38.5%) were categorized to cluster nCnD, 160 (28.4%) were to cluster C, and 186 (33.0%) were to cluster D. Multivariable logistic regression analysis revealed that both cluster C and D were significantly associated with the presence of FD (Table 3). Association between cluster C and FD were almost same level as association between cluster D and FD, suggesting that constipation and diarrhea were equally contributed to the onset of FD.

Table 3.

Relationship between the three symptom clusters and diagnosis of FD

| Non-dyspepsia (n = 6635) | FD (n = 563) | Univariable analysis* | Multivariable analysis† | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. (%) | No. (%) | Odds ratio (95% CI) | Odds ratio (95% CI) | |

| Cluster nCnD (n = 4318) | 4101 (95.0) | 217 (5.0) | Ref. | Ref. |

| Cluster C (n = 1378) | 1218 (88.4) | 160 (11.6) | 2.48 (2.00–3.08) | 2.57 (2.06–3.21) |

| Cluster D (n = 1502) | 1316 (87.6) | 186 (12.4) | 2.67 (2.18–3.28) | 2.80 (2.27–3.45) |

CI, confidence interval; FD, functional dyspepsia.

Analyzed by univariable logistic regression model.

Analyzed by multivariable logistic regression model with adjustment for cluster C, cluster D, age, gender, smoking habit, alcohol habit, and body mass index.

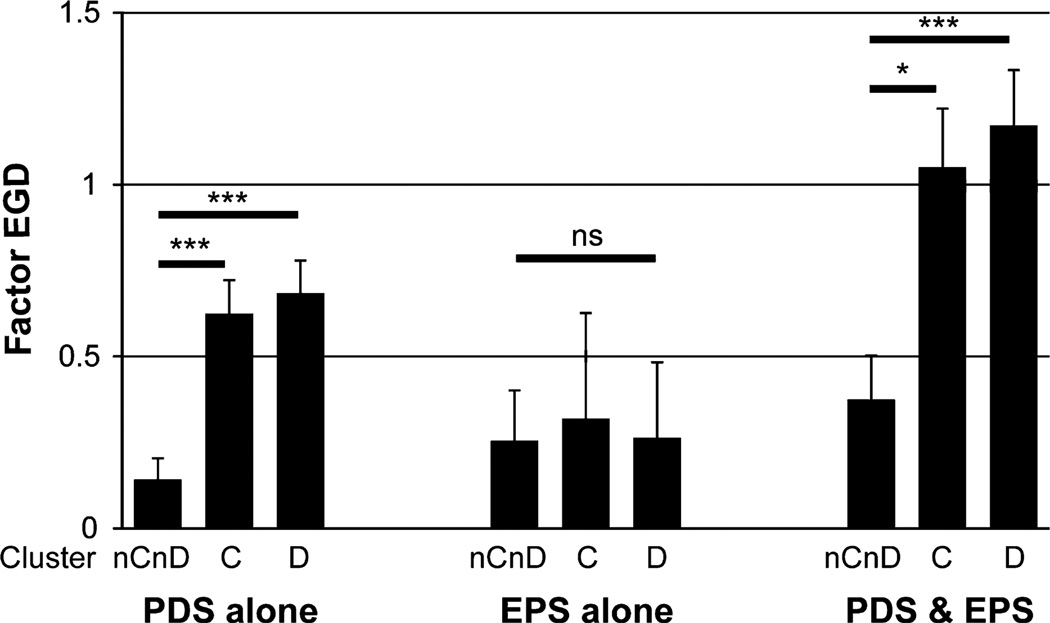

The prevalence of PDS or EPS was similar among the three symptom clusters: 217 FD participants in cluster nCnD were 146 (67.3%) with PDS alone, 26 (12.0%) with EPS alone, and 45 (20.7%) with both PDS and EPS; 160 in cluster C were 113 (70.6%) with PDS alone, 16 (10.0%) with EPS alone, and 31 (19.3%) with both PDS and EPS; 186 in cluster D were 120 (64.5%) with PDS alone, 20 (10.8%) with EPS alone, and 46 (24.7%) with both PDS and EPS. This illustrates that overlap of constipation or diarrhea was not associated with the presence/absence of PDS or EPS. In ‘PDS alone’ and ‘PDS and EPS’ groups, factor EGD score was higher in cluster C or D than in cluster nCnD. These results showed that upper GI symptoms, such as reflux or dyspepsia, were more severe in participants with bowel symptoms than without bowel symptoms especially in participants with PDS. On the other hand, in ‘EPS alone’ group, factor EGD score was not significantly different among the three symptom clusters (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Associations between upper gastrointestinal symptoms and the three symptom clusters in each subgroup of functional dyspepsia. ***P < 0.001, *P < 0.05 significant difference using one-way anova and Tukey’s post hoc analysis. EPS, epigastric pain syndrome; ns, not significant; PDS, postprandial distress syndrome.

Demographic factors in FD cases were significantly different between the three clusters (See Table S3 online). As there was a greater proportion of women in cluster C, subsequent analyses were examined for each gender separately. In both genders, alcohol consumption was associated with cluster nCnD and cluster D, but not with cluster C. In women, lower BMI was associated with cluster C.

DISCUSSION

This population based, large-scale cross-sectional study was conducted to identify GI symptom clusters in FGIDs. Cluster analysis in the present study revealed that all FGIDs, including FD, could be subcategorized based on concomitant bowel symptoms. As IBS is classified as constipation predominant IBS (IBS-C), diarrhea predominant IBS (IBS-D), and mixed IBS (IBS-M) in Rome III criteria,11 FD could be categorized into three clusters: absence of bowel symptoms (cluster nCnD), constipation predominant (cluster C), and diarrhea predominant (cluster D). Esophageal reflux symptoms, postprandial distress, and epigastric pain symptoms could not be separated using factor analysis, suggesting that overlaps between functional esophageal disorders, PDS, and EPS occur frequently. Classification of FD based on concomitant lower GI symptoms is a novel concept and may improve our ability to discriminate between subgroups of FD. Recent study showed that psychosocial factors, such as anxiety, depression, and somatization are also important variables for subgrouping FD.12 Classification of FD based on a combination of bowel symptoms and psychosocial factors would be a promising alternative for gastroduodenal symptom-based classification as proposed by the Rome III criteria.

In the present study, FD was more prevalent in participants with bowel symptoms (cluster C or cluster D) than those without bowel symptoms (cluster nCnD). This result is consistent with the observed high frequency of overlap between FD and IBS. Moreover, concomitant bowel symptoms were associated with demographic factors, such as gender, alcohol consumption, and BMI, among FD participants. These results suggest that the etiology of dyspepsia symptoms may differ among participants classified as cluster nCnD, cluster C, and cluster D. Corsetti et al.13 showed that FD-IBS overlap is more prevalent among women and is associated with a greater weight loss, overall symptom severity, and with hypersensitivity to distention than FD alone. The present study confirmed that FD with constipation is more prevalent among women, and is associated with lower BMI among women. On the other hand, these associations were not observed in FD with diarrhea (See Table S3 online).

When FD subjects were subcategorized into ‘PDS alone’, ‘EPS alone’, and ‘PDS and EPS’ groups, a significant association between these three groups and the three symptom clusters was not observed. However, the association between the severity of upper GI symptoms (factor EGD score) and concomitant bowel symptoms among PDS participants differed from the association among participants with EPS alone. Some previous studies also demonstrated that FD-IBS overlap patients have worse quality of life than FD-alone and IBS-alone patients.14,15 Results of the present study revealed that FD participants with bowel symptoms have greater symptoms severity than those without bowel symptoms especially in PDS, but not in EPS alone. This suggests that while PDS might be associated with the bowel symptoms, EPS without PDS might be independent of the presence/absence of bowel symptoms. Patients with constipation or diarrhea tend to have a general motor disturbance throughout the GI tract, including abnormal colonic transit and delayed gastric emptying, especially in patients with concomitant FD and IBS.16–18 GI motility disorders are likely to induce symptoms of PDS rather than those of EPS.19 The other study showed that patients with both FD and IBS are associated with hypersensitivity to distention of the stomach using gastric barostat.13 Gastric hypersensitivity was more prevalent when patients suffered from both EPS and PDS.20 These previous reports also support that concomitant constipation or diarrhea is associated with PDS, but not EPS alone.

Criticisms of the present study include possible differences between web-survey responder population and general population (generalizability). Web-based assessment may select participants from comparatively young and socially advantaged groups characterized by high literacy, and high internet access.21 In the present study, mean age in FD cases were older than that in non-dyspepsia controls. This might be because our population contains a higher proportion of young people (<40 years old) than general population. This participant bias might affect the prevalence of FD, as FD was more prevalent in those with lower household income, lower educational levels, larger household membership, and those who were unemployed.22–25 However, a previous study showed that participation bias is thought to have little effect on associations with putative risk factors.21 In addition, web-based survey has advantages related to the speed and cost of data collection.21 Therefore, it would be a powerful tool for studying characteristics of diseases and overlaps of the other disorders in FGIDs.

The disadvantage of the k-means cluster analysis is that the number of clusters must be supplied as a parameter. In the present study, we selected a three-cluster solution, as the results in three-cluster solution were the most understandable not only for gastroenterologists but also general practitioners. This categorization of FD can be determined just by the presence/absence of constipation or diarrhea which can be obtained from medical history taking. Whether treatments for bowel symptoms would improve dyspepsia symptoms in FD patients with constipation or diarrhea has not been examined26, warranting future research.

In conclusion, GI symptoms, including FD, can be categorized into three clusters based on the presence and type of bowel symptoms, suggesting differences in etiology between FD patients with constipation, with diarrhea, or neither. Constipation and diarrhea contribute almost equally to the presence of FD. PDS patients with bowel symptoms have greater symptoms severity than those without bowel symptoms. This categorization of FD is easy to use for general practice, and may improve classification of patients and identify subgroups that have differing pathophysiology or who may respond differently to treatment.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by a Health and Labour Sciences Research Grant for Research on Health Technology Assessment (Clinical Research Promotion No. 47 to HS) and a grant from the Smoking Research Foundation (to HS), the Keio Gijuku Academic Development Fund (to HS), the Grant from the JSPS Bilateral Joint Projects with Belgium (to HS), Grant-in-Aid for JSPS Fellows DC2 (to JM), the Keio University Grant-in-Aid for Encouragement of Young Medical Scientists (to JM), and the Graduate School Doctoral Student Aid Program, Keio University (to JM).

Footnotes

The preliminary results of this communication were presented and awarded at the 2st Meeting of Japan-Functional Dyspepsia Research Society (J-FD) held in Tokyo, November 14, 2009.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

HS & YF designed the research study. HS & YF conducted the web survey and collected the data. JM, HS & KA analyzed and interpreted the data. JM & HS drafted the article. KA & JMI revised the manuscript. TT & TH supervised and approved to be published.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no competing interests.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article:

Table S1. Average scores of 15 gastrointestinal symptoms.

Table S2. Associations between demographic factors and symptom factor scores (n = 8038).

Table S3. Difference of life-style characteristics between three symptom clusters in FD cases.

Please note: Wiley-Blackwell are not responsible for the content or functionality of any supporting materials supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the corresponding author of the article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Tack J, Talley NJ, Camilleri M, et al. Functional gastroduodenal disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1466–1479. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.11.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Okumura T, Tanno S, Ohhira M. Prevalence of functional dyspepsia in an outpatient clinic with primary care physicians in Japan. J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:187–194. doi: 10.1007/s00535-009-0168-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Geeraerts B, Tack J. Functional dyspepsia: past, present, and future. J Gastroenterol. 2008;43:251–255. doi: 10.1007/s00535-008-2167-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tack J, Talley NJ. Gastroduodenal disorders. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:757–763. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Talley NJ, Dennis EH, Schettler-Duncan VA, Lacy BE, Olden KW, Crowell MD. Overlapping upper and lower gastrointestinal symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome patients with constipation or diarrhea. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:2454–2459. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07699.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ford AC, Marwaha A, Lim A, Moayyedi P. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome in individuals with dyspepsia. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:401–409. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Savarino E, Pohl D, Zentilin P, et al. Functional heartburn has more in common with functional dyspepsia than with non-erosive reflux disease. Gut. 2009;58:1185–1191. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.175810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Piessevaux H, De Winter B, Louis E, et al. Dyspeptic symptoms in the general population: a factor and cluster analysis of symptom groupings. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2009;21:378–388. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2009.01262.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Svedlund J, Sjodin I, Dotevall G. GSRS – a clinical rating scale for gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome and peptic ulcer disease. Dig Dis Sci. 1988;33:129–134. doi: 10.1007/BF01535722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hongo M, Fukuhara S, Green J. Shokaki-ryoiki ni okeru QOL -nihongo ban GSRS niyoru QOL hyouka. Shindan to Chiryo. 1999;87:731–736. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Longstreth GF, Thompson WG, Chey WD, Houghton LA, Mearin F, Spiller RC. Functional bowel disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1480–1491. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.11.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Van Oudenhove L, Holvoet L, Vandenberghe J, Vos R, Tack J. Do we have an alternative for the Rome III gastroduodenal symptom-based subgroups in functional gastroduodenal disorders? A cluster analysis approach. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2011;23:730–738. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2011.01703.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Corsetti M, Caenepeel P, Fischler B, Janssens J, Tack J. Impact of coexisting irritable bowel syndrome on symptoms and pathophysiological mechanisms in functional dyspepsia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:1152–1159. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.30040.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaji M, Fujiwara Y, Shiba M, et al. Prevalence of overlaps between GERD, FD and IBS and impact on health-related quality of life. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;25:1151–1156. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2010.06249.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee HJ, Lee SY, Kim JH, et al. Depressive mood and quality of life in functional gastrointestinal disorders: differences between functional dyspepsia, irritable bowel syndrome and overlap syndrome. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2010;32:499–502. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2010.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Manabe N, Wong BS, Camilleri M, Burton D, McKinzie S, Zinsmeister AR. Lower functional gastrointestinal disorders: evidence of abnormal colonic transit in a 287 patient cohort. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2010;22:293–e82. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2009.01442.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Caballero-Plasencia AM, Valenzuela-Barranco M, Herrerias-Gutierrez JM, Esteban-Carretero JM. Altered gastric emptying in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Eur J Nucl Med. 1999;26:404–409. doi: 10.1007/s002590050404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stanghellini V, Tosetti C, Barbara G, et al. Dyspeptic symptoms and gastric emptying in the irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:2738–2743. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.07062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shindo T, Futagami S, Hiratsuka T, et al. Comparison of gastric emptying and plasma ghrelin levels in patients with functional dyspepsia and non-erosive reflux disease. Digestion. 2009;79:65–72. doi: 10.1159/000205740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kindt S, Caenepeel P, Bisschops R, Vos R, Tack J. Association of postprandial distress syndrome and epigastric pain syndrome with putative pathophysiological abnormalities in functional dyspepsia. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:A73. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heiervang E, Goodman R. Advantages and limitations of web-based surveys: evidence from a child mental health survey. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2011;46:69–76. doi: 10.1007/s00127-009-0171-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Drossman DA, Li Z, Andruzzi E, et al. U.S. householder survey of functional gastrointestinal disorders. Prevalence, sociodemography, and health impact. Dig Dis Sci. 1993;38:1569–1580. doi: 10.1007/BF01303162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tougas G, Chen Y, Hwang P, Liu MM, Eggleston A. Prevalence and impact of upper gastrointestinal symptoms in the Canadian population: findings from the DIGEST study. Domestic/International Gastroenterology Surveillance Study. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:2845–2854. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01427.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moayyedi P, Forman D, Braunholtz D, et al. The proportion of upper gastrointestinal symptoms in the community associated with Helicobacter pylori, lifestyle factors, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Leeds HELP Study Group. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:1448–1455. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.2126_1.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Minocha A, Wigington WC, Johnson WD. Detailed characterization of epidemiology of uninvestigated dyspepsia and its impact on quality of life among African Americans as compared to Caucasians. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:336–342. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00391.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Suzuki H, Hibi T. Overlap syndrome of functional dyspepsia and irritable bowel syndrome - are both diseases mutually exclusive? J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2011;17:360–365. doi: 10.5056/jnm.2011.17.4.360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.