Abstract

Background:

Even with high coverage of vaccination programs, Bordetella pertussis is still reported in various countries. It causes a high rate of mortality and morbidity in infants while it could be asymptomatic in adults. At the present study, we are going to evaluate the frequency of B. pertussis among received specimens.

Methods:

This cross-sectional study was performed on 138 children under one year who were suspected to have whooping cough from October 2008 to March in 2011. Nasopharyngeal dacron and rayon swabs and sera were used for PCR and serology respectively.

Results:

The mean age of the subjects was 1.9± 0.9 months. PCR was positive in 12 cases; ELISA was in agreement with PCR results except in one case that showed the specific antibody at borderline limit.

Conclusion:

The rate of reported positive results showed that pertussis not only is still present in the community, but the number of the asymptomatic cases who are able to transmit the disease may be considerable.

Keywords: Whooping cough, B. pertussis, PCR, ELISA.

INTRODUCTION

Pertussis is a severe disease in children and has remained one of the 10 causes of death in infants in the entire world. Reports show occurrence of about 10 million infected cases with almost 400,000 pertussis-related deaths annually [1-3]. Whooping cough usually manifests in wide spectrum of signs from asymptomatic presentation to a mild coughing illness in adolescents and adults who have partial immunity due to past vaccination or a full spectrum of symptoms in unimmunized patients. Hence, infection cannot be accurately diagnosed by just clinical presentations. Laboratory tests need to be used for confirmation of the diagnosis in those patients with suggestive clinical signs and symptoms or those having a history of exposure to the infected patients. However, negative tests cannot be accepted as a definitive result for excluding whooping cough. Therefore, it is necessary to apply improved laboratory diagnosis tests [1].

Diagnosis of whooping cough is often delayed in adults and older children, because of the lack of classic symptoms and also low awareness of some physicians. Late diagnosis of infection results in remaining of the patient among the community and transmission of infection for several weeks. ELISAs test, based on the rise of antibody titers is one of the main diagnostic procedures in unvaccinated cases. It uses specific B. pertussis proteins as antigens, with increases in IgA or IgG antibody titers to pertussis toxin (PT), filamentous hemmaglutinin (FHA). The greatest sensitivity and specificity is reported to be achieved for the serological diagnosis of B. pertussis infection by measuring of the antibody titer of PT [4]. It was also mentioned that only humoral responses to pertussis toxin were shown to be consistent among vaccinated and unvaccinated patients [5].

The use of PCR for the diagnosis of pertussis is increasingly being used since it provides sensitive and rapid results [6-9]. CDC and World Health Organization (WHO) have now included a positive PCR in lab definition of pertussis (Bamberger 2008). European Research Program for Improved Pertussis Strain Characterization and Surveillance has also insisted on the application of real-time PCR in order to have more sensitive results than isolation method to diagnosis B. pertussis, even after the initiation of antibiotic therapy. However, it is believed that the newer molecular technique has not provided satisfactory results in the older population who have less typical symptoms and often late clinical presentation [10, 11].

In our study, we determined the prevalence of B. pertussis among infants suspected to have whopping cough by PCR.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients:

This cross-sectional study was performed in children less than six months old who were suspected to have whooping cough and were re-ferred from physicians or other private clinical laboratories during October 2008 to March in 2011. The patients were asked for their vaccination history and tested for the rise of specific antibody by PCR method. Totally, 138 specimens (93 male and 45 female patients) were examined.

Specimens:

Nasopharyngeal dacron and rayon swabs (at restrict condition for respiratory sampling) and sera were used for PCR and serology respectively.

ELISA:

The immunity of the infants to whooping cough and their vaccination history was checked before sampling. ELISA was applied solely for unvaccinated children. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays was applied by the commercial kit (IBL International, GmbH, Hamburg, Germany). This kit was able to detect bordetella antigen containing pertussis toxin (PT) and filamentary haemagglutinine (FHA) to indicate recent Bordetella infection by determination of IgM and IgA antibodies. The procedure was followed as indicated by the manufacturer. According to the manufacturer’s classification, values of <16 U⁄ml, 16–24 U⁄ml and >24 U⁄ml were considered as negative, equivocal and positive, respectively.

DNA extraction and PCR protocols:

DNA extraction was performed in an identical manner for all patients. The samples were extracted by High Pure PCR Template preparation kit (Roche Co.). B. pertussis PCR kit (DNA Technology, Russia) was applied to detect the specific genome in the patients samples. The kit was specific signal based method. This kit had specific primers for amplification 417 base pair of template. Five µl of template, 10 µl PCR buffer, 10 µl mixture (containing specific primers and dNTP, 2.5 U taq polymerase) were mixed and amplified according to the kit guideline. The applied PCR kit was constructed in a format of competitive PCR with internal control. Provided specific primers could also amplify a product with 560 base pair as internal control as well as the specific product to ensure of proper extraction and removal of any expected inhibitors. The kit also contained specific probes labeled by fam and hex for specific and internal products respectively. These probes enabled us to increase the sensitivity and reduce contamination rate that are detected by the fluorescence detector [3].

Data collection Analysis procedure:

The analyzed results were expressed by the SPSS software (Version 16) in percentage.

RESULTS

A paroxysmal cough was observed at the sampling in all positive cases. IgM and IgA ELISA were positive in 11 cases. The result of ELISA test showed the rise of specific antibody at equivocal limit in one case that had been vaccinated a few days before sampling. Vaccination history was being asked from each patient at the sampling time. All those ELISA positive cases had no vaccination history.

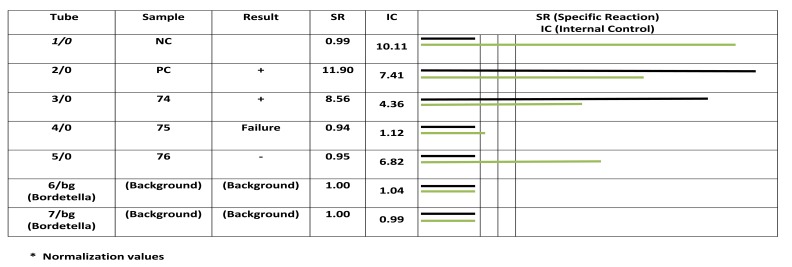

On the other hand PCR was positive in all ELISA positive including the case with borderline limit result (Fig. 1). The mean age of the subjects was 1.9 ± 0.9 months, eight were male and the rest were female.

Fig. (1).

Analyzing PCR product by fluorescence detector. Rows 1, and 2 are negative and positive controls respectively, row 3 to 5 are patient’s samples. Rows 6 and 7 are background. Column 6 shows emitted signals of each reaction. Black and white colors represents specific and competitive. The results of sample 198, 200 and 201 are positive, failure and negative. Sample number 200 shows an inhibition that is due to improper extraction that must be repeated after new extraction or re-sampling.

DISCUSSION

Analyzed data revealed that despite the high coverage of vaccination in recent years in Iran, pertussis is still observed in some cases. It means infection persists in the community in asymptomatic people.

Detected antibody in infants could be maternal antibodies or rise of antibody level due to vaccination [11] after two months old. Vaccination program in Iran are at age 2, 4, 6 and 18 months with a booster at 4 to 6 years old. It is recommended that the vaccination be repeated ten years after last vaccination. Unfortunately, reports show that most people do not repeat it after primary school. Reported data from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) surveillance from 1990–2003 confirmed incidence of pertussis has been increased with a nearly tenfold rise among adolescents [12], especially in persons aged 10–19 years and over 20 years [13]. Panahi (et al. 2007) has also studied those patients with prolonged cough who were referred to Zanjan hospital (a city in western part of Iran) and reported that 18.7% of the adults were infected with B. pertussis [14]. Therefore, it shows an unexpected high frequency rate of pertussis in adolescents which could be an alarm for public health system.

There is no accurate report of pertussis incidence in Iran, since most laboratories do not run a diagnostic test for it or if they do, the diagnostic procedure is not accurate. On the other hand, applying culture and isolation method is faced with some problems [15-17]. Some of the most encountered influential parameters would be delayed or improper techniques of specimen collection and inappropriate specimen transportation [4]. In this situation, the yield of culture is decreased specially in those laboratories that are not prepared, while requested specimens should be immediately plated onto selective and specific media [1]. Therefore, PCR has been applied more frequently in suspected infants since it provides more rapid and sensitive result than culture.

The Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends the use of PCR to support the diagnosis of pertussis in those with 2 or more weeks of coughing [12]. However, there is a variation in the sensitivity of the different PCR assays, because of the different DNA purification techniques, PCR primers, reaction conditions, and product detection methods [18]. However Ghanaie (et al. 2011) has reported PCR can be considered as a helpful tool for whooping cough criteria, since duration of coughing was longer in those children with a positive PCR than in those with a negative one [19].

In this study we applied PCR method to diagnosis whooping cough by using confirmed protocols. Applied protocols were proved to have sufficient stability and reproducibility of the results than the home made protocols. Real time PCR method has recently been reported with a high sensitivity ratio [20]. However, our PCR signal based method had high agreement with ELISA in results in our study, since all these positive cases had no vaccination history [21].

Previous researches showed that antibody responses to FHA are not specific to B. pertussis in unvaccinated cases, because it occurs following other Bordetella species; moreover, these antibodies may be cross-reacting epitopes to other bacteria including H. influenzae and M. pneumoniae. Thus, the best sensitivity and specificity for the serological diagnosis of B. pertussis infection is by ELISA measurement of IgM and IgA antibodies to PT in unimmunized cases [4].

CONCLUSION

The rate of reported positive results showed that pertussis not only is still present in the community, but the number of the asymptomatic, cases who are able to transmit the disease may be considerable.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors like to thank all the physicians, especially those who consulted us on the agreement of results with the clinical presentation of examined patients.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Declared none.

REFERENCES

- 1. Bamberger ES, Srugo I. What is new in pertussis? Eur J Pediatr. 2008;167:136–9. doi: 10.1007/s00431-007-0548-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Crowcroft NS, Stein C, Duclos P, et al. How best to estimate the global burden of pertussis? Lancet Infect Dis. 2003;3:413–8. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(03)00669-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tan T, Trindade E, Skowronski D. Epidemiology of pertussis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2005. pp. S10–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4. Mattoo S, Cherry JD. Molecular pathogenesis, epidemiology, and clinical manifestations of respiratory infections due to Bordetella pertussis and other Bordetella subspecies. Clin Microbiol Rev . 2005;18:326–82. doi: 10.1128/CMR.18.2.326-382.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tozzi AE, Celentano LP, Ciofi degli Atti ML, et al. Diagnosis and management of pertussis. CMAJ. 2005;172:509–15. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1040766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. André P, Caro V, Njamkepo E, et al. Comparison of serological and real-time PCR assays to diagnose Bordetella pertussis infection in 2007. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46:1672–7. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02187-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Probert WS, Ely J, Schrader K, et al. Identification and evaluation of new target sequences for specific detection of Bordetella pertussis by real-time PCR. Clin Microbiol. 2008;46:3228–31. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00386-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Van Kruijssen AM, Templeton K, van der Plas RN, et al. Detection of respiratory pathogens by real-time PCR in children with clinical suspicion of pertussis. Eur J Pediatr. 2007;166:1189–91. doi: 10.1007/s00431-006-0378-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wendelboe AM, Van Rie A. Diagnosis of pertussis: a historical review and recent developments. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2006;6:857–64. doi: 10.1586/14737159.6.6.857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Riffelmann M, Wirsing von König CH, Caro V, et al. Nucleic Acid amplification tests for diagnosis of Bordetella infections. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:4925–9. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.10.4925-4929.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hanlon M, Nambiar R, Kakakios A, et al. Pertussis antibody levels in infants immunized with an acellular pertussis component vaccine, measured using whole-cell pertussis ELISA. Immunol Cell Biol. 2000;78:254–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1711.2000.00910.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Greenberg DP. Pertussis in adolescents increasing incidence brings attention to the need for booster immunization of adolescents. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2006;24:721–8. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000172905.08606.a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Edwards K, Freeman DM. Adolescent and adult pertussis: disease burden and prevention. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2006;18:77–80. doi: 10.1097/01.mop.0000192520.48411.fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Panahi M, Mobaien AR, Karami A, et al. Frequency of pertussis among adults with prolonged cough. Scientific Med J. 2011;10:395–401. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Holberg-Petersen M, Jenum PA, Mannsåker T, et al. Comparison of PCR with culture applied on nasopharyngeal and throat swab specimens for the detection of Bordetella pertussis. Scand J Infect Dis. 2011;43:221–4. doi: 10.3109/00365548.2010.538855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cengiz AB, Yildirim I, Ceyhan M, et al. Comparison of nasopharyngeal culture, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and serological test for diagnosis of pertussis. Turk J Pediatr. 2009;51:309–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Greenberg DP, von König CH, Heininger U. Health burden of pertussis in infants and children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2005;24:S39–43. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000160911.65632.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Forsyth KD, Wirsing von Konig CH, Tan T, et al. Prevention of pertussis: recommendations derived from the second Global Pertussis Initiative roundtable meeting. Vaccine. 2007;25:2634–42. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ghanaie RM, Karimi A, Sadeghi H, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of the World Health Organization pertussis clinical case definition. Int J Infect Dis. 2010;14:1072–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2010.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lanotte P, Plouzeau C, Burucoa C, et al. Evaluation of four commercial real-time PCR assays for detection of Bordetella spp. in nasopharyngeal aspirates. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49:3943–6. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00335-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cherry JD, Grimprel E, Guiso N, et al. Defining pertussis epidemiology clinical, microbiologic and serologic perspectives. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2005;24:S25–34. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000160926.89577.3b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]