<LEAP> highlights the findings and application of Cochrane reviews and other evidence pertinent to the practice of physical therapy. The Cochrane Library is a respected source of reliable evidence related to health care. Cochrane systematic reviews explore the evidence for and against the effectiveness and appropriateness of interventions—medications, surgery, education, nutrition, exercise—and the evidence for and against the use of diagnostic tests for specific conditions. Cochrane reviews are designed to facilitate the decisions of clinicians, patients, and others in health care by providing a careful review and interpretation of research studies published in the scientific literature.1 Each article in this PTJ series summarizes a Cochrane review or other scientific evidence resource on a single topic and presents clinical scenarios based on real patients to illustrate how the results of the review can be used to directly inform clinical decisions. This article focuses on a patient with mild to moderate Parkinson disease. Can treadmill training improve the gait of individuals with Parkinson disease?

Parkinson disease (PD) affects 1 to 1.5 million people in the United States and is the second most common neurodegenerative disorder behind Alzheimer disease.2 People with PD must exhibit 2 or more of the following symptoms: rest tremor, rigidity, bradykinesia, and postural instability.3 Parkinson disease is mainly the result of the degeneration of dopaminergic neurons in the basal ganglia, specifically the substantia nigra pars compacta, and is commonly treated with levodopa, a pharmaceutical intervention.3 However, as the disease progresses, levodopa becomes less effective at managing symptoms, and additional non-dopaminergic pathways play a role in the debilitating motor symptoms of PD.3,4

People with PD often experience increased gait impairments as the disease progresses and symptoms become more severe.5 Impairments include hypokinesia (decreased step length with decreased speed), decreased coordination, festination (decreased step length with increased cadence), freezing of gait (the inability to produce effective steps at the initiation of gait or the complete cessation of stepping during gait), and difficulty with dual tasking during gait.6–8 Coupled with these gait impairments are an increased risk and rate of falling. Increased probability of falls not only increases the risk of injury such as hip fracture, but also affects an individual's independence and ability to interact within the community. Additionally, fear of falling has psychological consequences and can lead to self-isolation and depression.9

The physical therapist can play an important role in the life of an individual with PD as it becomes clearer how exercise can benefit those with PD.10 Gait impairments may be related to impaired functioning of the basal ganglia, which are responsible for the internal cueing of the rhythmic movement of gait, as well as other well-learned movements that require little cognitive attention during performance.6 Auditory cues, such as a metronome or music during dance exercise, and visual cues, such as horizontal lines on a floor, provide external cues that draw cognitive attention to the motor task. Increased attention to the task may help to compensate for the deficiencies associated with internally cued movements.11

Treadmill training also is thought to provide an external cue to improve gait function in those with PD, although exact mechanisms are debated (eg, somatosensory cue versus visual cue).12,13 In addition to Mehrholz and colleagues' Cochrane review,14 other reviews have reported treadmill training as an effective intervention for those with PD.13 One advantage of treadmill training is that it is generally accessible, as many physical therapy clinics have at least one treadmill and local fitness centers often have several treadmills. Although it has been reported that treadmill training improves gait function, it is important to consider the safety of treadmill training for those with PD.

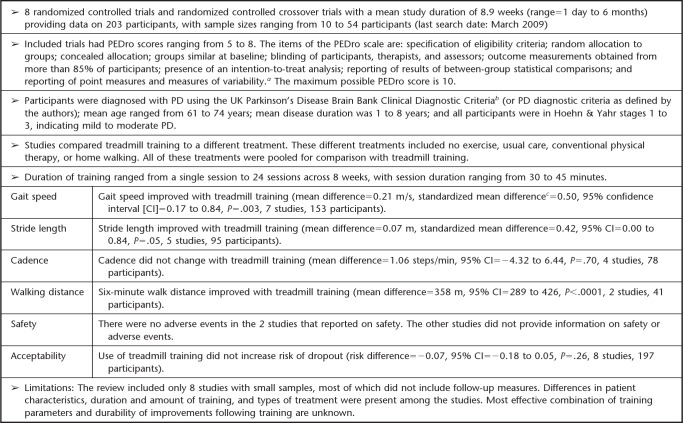

Mehrholz et al14 conducted a Cochrane review to assess the effectiveness of treadmill training in improving gait function of patients with PD. Primary outcomes were walking speed and stride length. Secondary outcomes were cadence and walking distance, as well as the acceptability and safety of treadmill training. The results of the review are summarized in the Appendix.

Take-Home Message

Mehrholz et al14 reviewed 8 studies that included 203 participants with PD in Hoehn & Yahr stages 1 to 3 (Hoehn & Yahr staging ranges from 0 to 5; stage 1 indicates unilateral PD symptoms, and stage 3 indicates bilateral symptoms with balance impairment). These studies compared treadmill training with all other treatment approaches, and analyses focused on the effects of training on gait parameters measured immediately upon completion of the intervention. Mehrholz et al concluded that treadmill training is safe for and accepted by people with PD, as no adverse events were reported and the use of treadmill training did not increase participant dropout rates. However, most of the studies did not directly report on adverse events or safety. They further concluded that treadmill training can improve gait speed, stride length, and walking distance, with moderate effect sizes, but that treadmill training does not alter cadence among those with mild to moderate PD (see Appendix for details).

The studies varied considerably in terms of number of sessions of treadmill training provided, length of each session, and specific treadmill training parameters used. Most of the studies included no follow-up. The few studies that did include follow-up tracked participants for periods of 1 to 5 months after intervention. The results should be interpreted while keeping in mind the heterogeneity in the interventions delivered, the small number of studies included in the review and their relatively small sample sizes, and the lack of follow-up measures to determine how long gait improvements may last following treadmill training.

Case #8: Applying Evidence to a Patient With PD

Can treadmill training help this patient?

Mr. Walker is an 82-year-old man who lives at home with his wife. He was diagnosed with idiopathic PD 5 years ago and takes 100 mg of Stalevo (Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corp, East Hanover, New Jersey) 4 times daily to treat his PD. He is in Hoehn & Yahr stage 2.5 and has moderately severe motor symptoms of PD, as indicated by his score of 32 on the motor subscale of the Movement Disorder Society Unified Parkinson Disease Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS-III, range of possible scores=0–132, with higher scores indicating greater severity of motor symptoms)17 when assessed on medication at his initial evaluation. Mr. Walker uses a single-point cane for community ambulation.

At initial evaluation, utilizing a GAITRite walkway (CIR Systems Inc, Havertown, Pennsylvania), he had a gait speed of 1.1 m/s, a stride length of 1.21 m, a cadence of 110 steps/min, and a 6-minute walk distance of 393 m. He also reported freezing of gait and had a score of 10 on the Freezing of Gait Questionnaire (FOGQ), a 6-item scale with scores ranging from 0 to 24, with higher scores indicating greater frequency or duration of freezing episodes.18,19

Mr. Walker had a summary score of 43 on the Parkinson's Disease Questionnaire (PDQ-39),20,21 a PD-specific measure of quality of life (range of scores=0–100, with higher scores indicating greater negative impact of PD on quality of life). He was referred for physical therapy after reporting a noticeable reduction in gait speed, an increase in frequency of freezing episodes, and increased difficulty ambulating in the community for sustained periods of time. Mr. Walker had no history of cardiovascular or musculoskeletal conditions that would be contraindications for treadmill training.

How do we apply the results of the Cochrane Systematic Review to Mr. Walker?

Mr. Walker was similar in many ways to the participants in the studies reviewed by Mehrholz et al14 in that he had mild to moderate idiopathic PD, did not have dementia, was not depressed, and had no conditions that would contraindicate treadmill training. As such, he appeared to be an appropriate candidate to initiate treadmill training. Mr. Walker completed 20 minutes of treadmill training in the clinic on the day of initial evaluation, walking at the same speed as his preferred overground gait speed. He was able to operate the treadmill controls independently and demonstrated no difficulties with walking safely on the treadmill. He held the handrails at all times and utilized the treadmill safety stop key with the tether and clip. These safety precautions were particularly important, given Mr. Walker's history of freezing of gait and the possibility of freezing episodes occurring during treadmill walking. Mr. Walker's wife also was familiar with the safe operation of the treadmill, and the couple indicated that they had a treadmill at home. Mr. Walker stated that he would like to utilize his treadmill at home.

A visit was made to the Walkers' home to evaluate the treadmill and observe Mr. Walker's use of the device to ensure that he could use it safely. Mrs. Walker also participated in this session and agreed to supervise Mr. Walker's treadmill sessions. Mr. Walker was instructed to walk on his treadmill for 20 minutes per day, 4 or 5 days per week, and gradually build up to 30 minutes per session as tolerated, utilizing a treadmill speed matched to his overground gait speed. Training at preferred overground speed was selected based on recent work suggesting that this may be a more effective approach than higher-intensity treadmill training for people with PD.22 Mr. Walker was instructed to rest at any time as needed during training sessions. Follow-up visits were made once every 2 weeks and always at the same time of day to reevaluate Mr. Walker's overground gait speed (assessed using a stopwatch to time a 10-m walk) and adjust his treadmill training speed accordingly. He continued to walk 30 minutes per day, 4 to 5 days per week, at his current overground speed for a period of 6 weeks. There were no adverse events associated with his treadmill training.

How well do the outcomes of the intervention provided to Mr. Walker match those suggested by the systematic review?

As predicted by the results of the systematic review, Mr. Walker demonstrated increases in walking speed, stride length, and walking distance, but no change in cadence, following the 6-week period of treadmill training. Upon completion of training, Mr. Walker had a gait speed of 1.21 m/s (an increase of 0.11 m/s from the initial evaluation), a stride length of 1.30 m (an increase of 0.1 m), a cadence of 112 steps/min (a change of only 2 steps/min), and a 6-minute walk distance of 464 m (an increase of 71 m). The magnitudes of these changes were generally in keeping with the effect sizes noted in the systematic review and exceeded the minimal clinically important differences for older adults of 0.1 m/s for gait speed and 50 m for the 6-minute walk.23 Additional measures were: MDS-UPDRS-III score improved to 29 (a 9% change), FOGQ score improved to 7 (a 30% change), and PDQ-39 score improved to 32 (a 25% change). These latter measures were not addressed in the systematic review, but other studies and reviews have shown improvements in motor symptoms and quality of life with treadmill training.13,24 There was no change in Hoehn & Yahr stage for Mr. Walker, who remained at stage 2.5 after treadmill training.

Can you apply the results of the systematic review to your own patients?

The systematic review results applied well to Mr. Walker. The review included participants with PD in Hoehn & Yahr stages 1.5 to 3 who were able to walk independently. The common feature of all of there viewed studies was the use of treadmill training, with or without body weight support, to improve walking performance. The review has several limitations, such as the exclusion of individuals with cognitive impairments, depression, and other conditions that some patients with PD (but not Mr. Walker) may have. As such, the generalizability of these results to all individuals with PD may be limited. The availability of a treadmill for use in training also is a requirement for implementation of an intervention and may be a limiting factor in some settings, although treadmills are widely available in physical therapy clinics and local fitness centers.

What can be advised based on the results of this systematic review?

Based on the results of this systematic review, we can conclude that treadmill training is safe and appropriate for some individuals with mild to moderate PD. These individuals must have the cognitive and physical ability to utilize the treadmill, must understand and use the necessary safety precautions, and have adequate supervision as needed. Treadmill training can be expected to result in improvements in gait speed, stride length, and walking distance. Treadmill training does not appear to influence cadence, but this finding should not be viewed negatively. The maintenance of cadence following treadmill training, in conjunction with increased stride length, results in faster gait speed, which is a positive outcome. The review does not include information to support or refute the effects of treadmill training on other aspects of gait, such as dual task walking and decreased coordination. In addition, treadmill training may not address reduced arm swing, which is commonly seen in people with PD, as armswing is limited during treadmill training through use of handrails. Furthermore, generalizability of treadmill training may be limited, as the studies that were reviewed excluded individuals with a history of cognitive, depressive, cardiovascular, or orthopedic conditions.

With regard to the specific parameters for treadmill training, additional work is warranted to determine the ideal combinations of intensity, frequency, and duration. There are no obvious differences between studies that do and do not utilize body weight support, although use of a harness for safety purposes rather than for body weight support may be useful for some individuals. Finally, more work is needed to determine the durability of the effects of treadmill training and whether the benefits of training are related to the treadmill itself and the cueing it provides12,25 or whether they are simply related to the amount of walking practice that is afforded through treadmill training. It may be that the external cues provided by the treadmill provide unique benefits that could not be obtained through practice of overground walking. Alternatively, perhaps the cueing provided by the treadmill is not critical, and a similar amount of overground walking practice would yield results comparable to those obtained with treadmill training.

Appendix.

Appendix.

Treadmill Training for Patients with Parkinson Disease (PD): Cochrane Review Results14

a Herbert R, Moseley A, Sherrington C. PEDro: a database of randomized controlled trials in physiotherapy. Health Infor Manag. 1998;28:186.

b Hughes AJ, Daniel SE, Kilford L, Lees AJ. Accuracy of clinical diagnosis of idiopathic Parkinson's disease: a clinico-pathological study of 100 cases. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1992;55:181–184.

c The standardized mean difference is the difference in mean outcome between groups divided by the standard deviation of the outcome.15 A standardized mean difference of 0.2 represents a small effect, 0.5 represents a moderate effect, and 0.8 represents a large effect.16

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant TL1 RR024995.

References

- 1. The Cochrane Library. Available at: http://www.thecochranelibrary.com/view/0/index.html Accessed March 14, 2012

- 2. Nussbaum RL, Ellis CE. Alzheimer's disease and Parkinson's disease. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1356–1364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fahn S. Description of Parkinson's disease as a clinical syndrome. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003;991:1–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Perry EK, McKeith I, Thompson P, et al. Topography, extent, and clinical relevance of neurochemical deficits in dementia of Lewy body type, Parkinson's disease, and Alzheimer's disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1991;640:197–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gray P, Hildebrand K. Fall risk factors in Parkinson's disease. J Neurosci Nurs. 2000;32:222–228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Morris M, Iansek R, Galna B. Gait festination and freezing in Parkinson's disease: pathogenesis and rehabilitation. Mov Disord. 2008;23:S451–S460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Plotnik M, Giladi N, Hausdorff JM. Bilateral coordination of gait and Parkinson's disease: the effects of dual tasking. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2009;80:347–350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yogev G, Plotnik M, Peretz C, et al. Gait asymmetry in patients with Parkinson's disease and elderly fallers: when does the bilateral coordination of gait require attention? Exp Brain Res. 2007;177:336–346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bloem BR, Hausdorff JM, Visser JE, Giladi N. Falls and freezing of gait in Parkinson's disease: a review of two interconnected, episodic phenomena. Mov Disord. 2004;19:871–884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Goodwin VA, Richards SH, Taylor RS, et al. The effectiveness of exercise interventions for people with Parkinson's disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mov Disord. 2008;23:631–640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Morris ME, Iansek R, Matyas TA, Summers JJ. Stride length regulation in Parkinson's disease: normalization strategies and underlying mechanisms. Brain. 1996;119(pt 2):551–568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bello O, Marquez G, Camblor M, Fernandez-Del-Olmo M. Mechanisms involved in treadmill walking improvements in Parkinson's disease. Gait Posture. 2010;32:118–123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Herman T, Giladi N, Hausdorff JM. Treadmill training for the treatment of gait disturbances in people with Parkinson's disease: a mini-review. J Neural Transm. 2009;116:307–318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mehrholz J, Friis R, Kugler J, et al. Treadmill training for patients with Parkinson's disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(1):CD007830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Higgins JPT, Green S; Cochrane Collaboration Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell; 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 2nd ed. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1988 [Google Scholar]

- 17. Goetz CG, Tilley BC, Shaftman SR, et al. Movement Disorder Society–sponsored revision of the Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS): scale presentation and clinimetric testing results. Mov Disord. 2008;23:2129–2170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Giladi N, Shabtai H, Simon ES, et al. Construction of freezing of gait questionnaire for patients with Parkinsonism. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2000;6:165–170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Giladi N, Tal J, Azulay T, et al. Validation of the freezing of gait questionnaire in patients with Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2009;24:655–661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jenkinson C, Peto V, Fitzpatrick R, et al. Self-reported functioning and well-being in patients with Parkinson's disease: comparison of the short-form health survey (SF-36) and the Parkinson's Disease Questionnaire (PDQ-39). Age Ageing. 1995;24:505–509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jenkinson C, Fitzpatrick R, Peto V, et al. The Parkinson's Disease Questionnaire (PDQ-39): development and validation of a Parkinson's disease summary index score. Age Ageing. 1997;26:353–357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. American Academy of Neurology Low intensity treadmill exercise is best to improve walking in Parkinson's. Available at: http://www.aan.com/press/index.cfm?fuseaction=release.view&release=932 Accessed February 17, 2012

- 23. Perera S, Mody SH, Woodman RC, Studenski SA. Meaningful change and responsiveness in common physical performance measures in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:743–749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Herman T, Giladi N, Gruendlinger L, Hausdorff JM. Six weeks of intensive treadmill training improves gait and quality of life in patients with Parkinson's disease: a pilot study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2007;88:1154–1158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bello O, Fernandez-Del-Olmo M. How does the treadmill affect gait in Parkinson's disease? Curr Aging Sci. 2011. July 15 [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]