Abstract

Lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM) is a rare disease characterised by proliferation of abnormal smooth muscle-like cells (LAM cells) leading to progressive cystic destruction of the lung, lymphatic abnormalities and abdominal tumours. It affects predominantly females and can occur sporadically or in patients with tuberous sclerosis complex.

This review describes the recent progress in our understanding of the molecular pathogenesis of the disease and LAM cell biology. It also summarises current therapeutic approaches and the most promising areas of research for future therapeutic strategies.

Keywords: LAM cells, lymphangioleiomyomatosis, tuberous sclerosis complex

Lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM) is a rare multisystem disorder affecting predominantly young females in their reproductive years. It is characterised by progressive cystic destruction of the lung, lymphatic abnormalities and abdominal tumours (e.g. angiomyolipomas) [1–5]. The main feature of the disease is the proliferation of abnormal smooth muscle-like cells (LAM cells), leading to the formation of thin-walled cysts in the lungs and cystic structures (i.e. lymphangioleiomyoma) in the axial lymphatics. LAM is also characterised by high prevalence of angiomyolipomas (AMLs), benign tumours which involve primarily the kidneys, composed of smooth muscle cells and adipocytes together with incomplete blood vessels [1–5].

LAM arise sporadically in otherwise healthy females and in about 30% of females with tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC), an autosomal dominant syndrome characterised by hamartoma formation in multiple organ systems, cerebral calcifications, seizures and cognitive defects [6–9]. In the past decades, the finding that LAM lesions in patients with TSC (TSC-LAM) and sporadic LAM (S-LAM) are histologically identical was consistent with the hypothesis that these diseases may share common genetic and pathogenetic mechanisms. In this review, we will focus on current concepts of the molecular pathogenesis of LAM and the rationale of currently available and experimental treatment.

PATHOGENESIS

Pathology of LAM lesions and characterisation of LAM cells

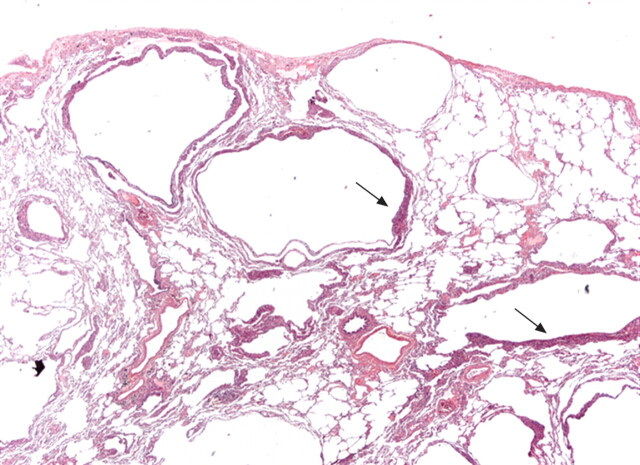

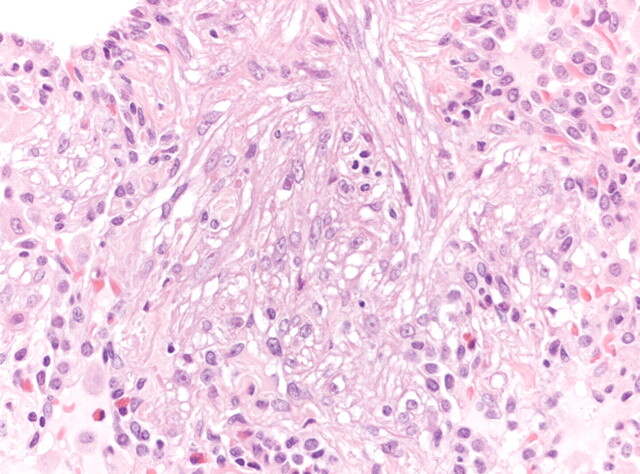

Lung lesions in LAM are characterised by lung nodules or small cell clusters of LAM cells near cystic lesions and along pulmonary bronchioles, blood vessels and lymphatics (figs 1 and 2). LAM cells consist of two types of cell subpopulations: myofibroblast-like spindle-shaped cells expressing smooth muscle-specific proteins, such as α-actin, desmin and vimentin, and epithelioid-like cells, which express glycoprotein gp100, a marker of melanoma cells and immature melanocytes showing immunoreactivity with human melanoma black 45 (HMB45) monoclonal antibody [10–12]. Although the significance of gp100 expression by LAM cells is still uncertain, it appears to correlate inversely with the expression of proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA), a marker of DNA synthesis and cell proliferation [13]: the spindle-shaped cells forming the core of the nodules show low gp100 expression and high PCNA expression while epithelioid cells in the periphery of the nodule exhibit the reverse pattern. Thus, the spindle-shaped cells may represent the proliferative element of LAM lesions [14].

Figure 1.

Surgical lung biopsy showing several thin-walled rounded cysts of varying dimensions. The LAM cells form small plaques in the wall of the cysts (arrows) (haematoxylin–eosin, 20×). Figure courtesy of A. Cavazza.

Figure 2.

Surgical lung biopsy showing LAM cells. Note the spindle-to-epithelioid morphology, the large amount of eosinophilic cytoplasm and the bland nuclei (haematoxylin–eosin, 200×). Figure courtesy of A. Cavazza.

LAM cells also express oestrogen and progesterone receptors and LAM may worsen during pregnancy [10, 11], suggesting that cell proliferation may be modulated by hormonal factors [15–17]. The HMB45-positive LAM cell phenotype also includes the muscular elements of AMLs [18] where they are combined with dysplastic blood vessels and adipocytes [19, 20]. In the axial lymphatics, LAM cells form chaotic clumps of cells, leading to thickening of lymphatic walls, obliteration of the vessel lumen and cystic dilatation.

Although the origin of LAM cells remains unclear, recent data indicate that they can metastasize, suggesting similarities between migrating LAM cells and either mesenchymal stem cells [13, 14] or migrating cancer stem cells [21]. Indeed, LAM cells have been found in the blood, chylous fluids, and urine of some LAM patients [22], demonstrating that LAM cells can leave primary lesions and disseminate through blood or lymph vessels. A LAM cell lesion of recipient origin was detected after single-lung transplantation in a patient with LAM [23]. Identical TSC2 gene mutations in pulmonary LAM cells and AMLs of TSC patients with LAM have also been reported [24]. Lesions with identical mutations of the tumour suppressor TSC2 gene in the lymph nodes of patients with LAM were also found [23, 25].

Genetic and molecular pathogenesis

Mutations in the tuberous sclerosis genes TSC1 and TSC2 are considered to be the cause of LAM, with TSC2 mutations arising more frequently than TSC1 mutations (the majority of LAM, and ∼60% of TSC cases) [21, 26, 27]. The current accepted model for LAM is consistent with Knudson's “two-hit” hypothesis of tumour development [28]: an initial mutation in either TSC1 or TSC2 is followed by a second hit represented by loss of heterozygosity, causing the loss of function of either TSC1 or TSC2 gene products. S-LAM develops due to two acquired mutations (usually in TSC2), while patients with TSC-LAM have one germline mutation (again usually in TSC2) and one acquired mutation [10]. These findings clarify why LAM is frequent in patients with TSC, while S-LAM is a particularly rare disease.

The protein products of TSC1 and TSC2, whose names are derived from characteristic phenotypic features of patients with TSC, are hamartin and tuberin, respectively [29, 30]. Hamartin is a 130-kDa protein containing a potential trans-membrane domain near its N-terminus, a coiled-coil domain, an interaction site with tuberin and ezrin-radixin-moesin (ERM) family-binding domain [31, 32]. Its C-terminal domain binds to neurofilament L (NF-L) in cortical neurons [33].

Tuberin is a 198-kDa protein that interacts with hamartin through its N-terminus [31, 34]. Tuberin also has a region of homology with the Rap 1 GTPase–activating protein (Rap1GAP) [30, 35]. Finally, tuberin contains multiple potential phosphorylation sites for different kinases such as protein kinase B (Akt/PKB) [30, 35–40]. The many and varied domains in hamartin and tuberin reflect the important role for the two proteins in the transduction of signals from cell membrane-associated receptors. Tuberin is involved in the cell cycle and in cell growth and proliferation [41]. Hamartin is thought to have a role in the reorganisation of the actin cytoskeleton by inducing an increase in the levels of Rho-GTP and by binding activated ERM proteins [42]. Thus, absence of hamartin causes loss of focal adhesions and detachment from substrate.

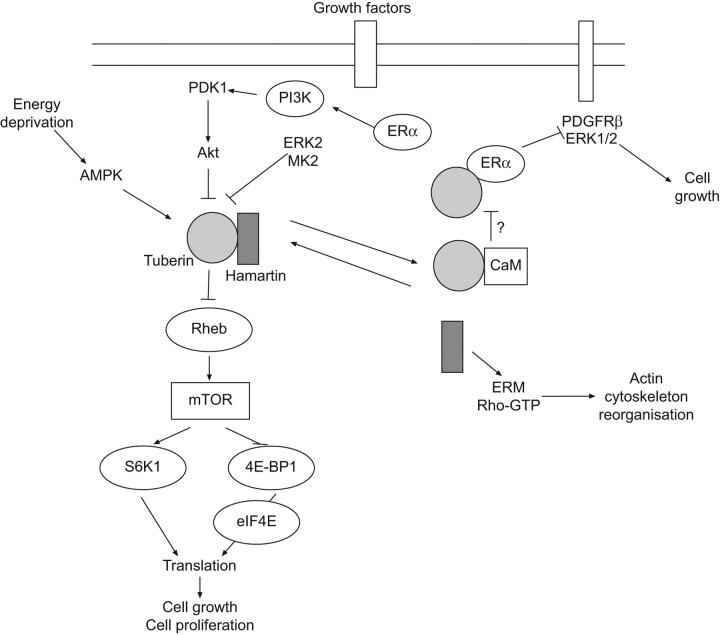

Many studies demonstrated that hamartin and tuberin are closely associated in vivo [43–46]. A major role of the hamartin–tuberin complex is the inhibition of a kinase known as the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), a central regulator of cell growth [47]. mTOR realises its effects through two main mechanisms. First, it stimulates the phosphorylation and activation of S6K, leading to ribosomal assembly. Secondly, mTOR enhances phosphorylation of 4E-BP1, a protein that binds and activates the eukaryotic translation initiation factor eIF4E, permitting protein synthesis to begin [48]. Hamartin–tuberin complex maintains mTOR in a deactivated state through tuberin's ability to stimulate GTP hydrolysis by Ras homologue expressed in brain (Rheb) [49–52]. Indeed, mutations in both hamartin and tuberin have been shown to enhance Rheb activity [53, 54].

Several kinases can inactivate the hamartin–tuberin complex, thus increasing mTOR activity and cell growth. Among these is Akt/PKB, a cytosolic kinase recruited to the membrane upon ligation of membrane receptor tyrosine kinases, such as the insulin receptor. Akt/PKB phosphorylates tuberin, thereby promoting dissociation of the hamartin–tuberin complex (fig. 3) [55, 56]. However, tuberin can also be phosphorylated by extracellular signal-regulated kinase 2 (ERK2) and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)-activated protein kinase 2, resulting in inactivation of hamartin–tuberin complex [57, 58]. In contrast, under conditions of energy deprivation, an AMP-activated protein kinase (AMP kinase) phosphorylates tuberin on a site that leads to increased activity of the hamartin–tuberin complex and consequent inactivation of mTOR [59].

Figure 3.

Schematic representation of the signalling transduction pathways involving the tuberous sclerosis proteins, hamartin and tuberin. The main pathway involved in lymphangioleiomyomatosis pathogenesis is mediated by Akt, whose activation inhibits hamartin–tuberin complex, leading to mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) activation and thus to cell growth and proliferation. Arrows indicate activating or facilitating influences; flat-headed lines indicate inhibitory influences. ERK2: extracellular signal-regulated kinase 2; MK2: mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)-activated protein kinase 2; Rheb: Ras homologue expressed in brain; ERα: oestrogen receptor α; PDGFRβ: platelet-derived growth factor receptor β; CaM: calmodulin; ERM: ezrin-radixin-moesin.

Although its role remains uncertain, oestrogen may be involved in pathogenesis of LAM by interaction with signalling events in LAM cells. Tuberin has been found to interact directly with the intracellular oestrogen receptor alpha (ERα) through a C-terminal domain, resulting in growth inhibition due to a reduction in oestrogen-induced activation of a platelet-derived growth factor receptor β and extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2) signalling pathway [60]. Moreover, there are different nongenomic oestrogen-activated signalling pathways dependent on ERα, which may be involved in the pathogenesis of LAM. Among these, the phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)–Akt signalling cascade [61] and a pathway leading to tuberin degradation induced by dephosphorylation have been recognised [62]. Recently, the binding between calmodulin and tuberin has been hypothesised to have a role in tuberin's effects on oestrogens-mediated signalling [63, 64], and oestrogens have been shown to enhance survival of LAM-like cells and metastasis to the lung [65].

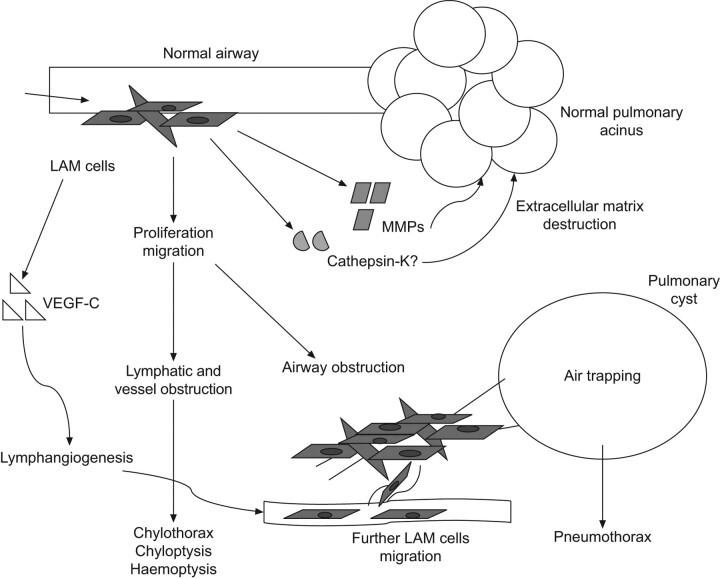

Altered metabolism of extracellular matrix can be involved in pathogenesis of LAM contributing to cell migration and dissemination in a manner similar to protease-mediated invasion of malignant tumours [66]. Spindle-shaped LAM cells express membrane type 1 matrix metalloproteinase (MT1 MMP) and matrix metalloproteinase 2 (MMP-2), which is activated by MT1 MMP [67, 68]. These proteinases degrade extracellular matrix proteins thus facilitating cell migration. The observation that cleavage of insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-binding proteins by MMP-1 can promote human airway smooth muscle growth [69] suggested the hypothesis that MMPs may also enhance LAM cell growth via inactivation of IGF-binding proteins [14]. Recently, strong expression of cathepsin-K, a protease produced normally by human osteoclasts, has been demonstrated in spindle- and epithelioid-shaped cells of LAM [70]. Cathepsin-K is a papain-like cysteine protease [71], with high matrix (collagen, elastin)-degrading activity which may significantly contribute, together with metalloproteinases to the progressive structural damage and remodelling of pulmonary parenchyma [72]. Moreover, the finding of cathepsin-K immunoexpression in the spindle- and epithelioid smooth muscle and adipocyte-like cells in renal AMLs confirms the phenotypic identity of these morphologically heterogeneous cells and their relationship with the cellular elements composing the pulmonary LAM.

Origins of LAM lesions

LAM cells proliferate along lymphatics where they are divided into fascicles or bundles by channels lined by lymphatic endothelial cells. LAM cells have been hypothesised to be involved in lymphangiogenesis by producing vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-C [73]. The recruitment of lymphatic channels by LAM cells may account for their ability to metastasise to distant sites and facilitate further invasion of lung tissue [74]. Obstruction and damage of lymphatics may be the mechanism involved in development of chyloptysis and chylothorax. Besides, proliferation of LAM cells along lymphatic channels puts them in proximity to both airways and blood vessels. Obstruction of blood vessels causes focal areas of haemorrhage while the cystic changes in the pulmonary parenchyma might be the result of the constrictive effect of bundles of LAM cells on airways, leading to airflow obstruction and air trapping [75, 76]. The degradation of the supporting architecture of the pulmonary interstitium due to MMPs and cathepsin-K produced by LAM cells is considered an alternative or coexisting mechanism for cyst development (fig. 4) [68–70]. Cathepsin-K overproduction and/or the disregulation of mTOR pathway in osteoclasts may be an alternative mechanism for bone loss that has been observed in patients with LAM [70], although oestrogen deficiency has been hypothesised to be a possible cause for the abnormal bone mineral density in these patients [77].

Figure 4.

Possible mechanisms of lung cysts formation in lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM). VEGF: vascular endothelial growth factor; MMP: matrix metalloproteinase. Adapted from [76] with permission from the publisher.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

Pneumothorax, progressive dyspnoea and chylous pleural effusions are the main clinical manifestations of LAM [1–4, 78]. Dyspnoea is the most common symptom (over 70% of patients) and the result of airflow obstruction and cystic destruction of the lung parenchyma. Over 50% of patients have a history of pneumothorax in their clinical course. Pneumothorax is often the first manifestation and recurrences are common [4]. Chylous pleural effusions are less common, but tend to recur after simple aspiration [4, 79]. Other respiratory symptoms are cough, chyloptysis and haemoptysis (table 1). As described above, haemoptysis and chyloptysis may be the result of LAM cell obstruction of pulmonary blood vessels and lymphatics, respectively. Extrapulmonary manifestations of LAM are AMLs, which occur mostly in the kidneys, chylous ascites, abdominal lymphadenopathy and large cystic lymphatic masses termed lymphangioleiomyomas [80, 81]. AMLs are benign tumours that occur in ∼80% of patients with TSC-LAM and in ∼40% of those with S-LAM [5]. These tumours may vary in size from 1 mm to more than 20 cm in diameter, leading to complete disruption of the normal kidney architecture [79, 82–84]. AMLs are asymptomatic in most cases, however multiple and large masses are more likely to cause haemorrhage and symptoms such as haematuria and flank pain [80, 85].

Table 1. Symptoms and clinical manifestations in lymphangioleiomyomatosis.

| Patients % | |

| Dyspnoea | 87 |

| Cough | 51 |

| Chest pain | 34 |

| Haemoptysis | 22 |

| Pneumothorax | 65 |

| Chylous effusion | 28 |

Enlarged retroperitoneal, retrocrural or occasionally pelvic lymph nodes, are detected by computed tomography (CT) scanning in about 30% of patients, but are usually asymptomatic [84]. Lymphangioleiomyomas are large cystic tumours primarily occuring in the abdomen, retroperitoneum and pelvis and can been found in up to 10% of patients [4]. Associated symptoms are nausea, abdominal distension, peripheral oedema and urinary symptoms [86]. Chylous ascites due to lymphatic obstruction and associated with chylous thoracic collections is present in 10% of patients with more advanced disease [4, 84]. It has been described that meningiomas have an increased prevalence in LAM than in general population, although their relationship with LAM, TSC or therapy with progesterone is unclear. As progesterone has a mitogenic effect on meningiomas, and progesterone receptors are found in these tumours, it has been hypothesised that hormonal therapy with progesterone could have a role in formation or progression of meningiomas [87]. Finally, signs consistent with TSC, such as facial angiofibromas, periungual fibromas, nail ridging and the shagreen patch, are seen in patients with TSC-LAM. As these manifestations may be overlooked in patients with mild disease, a full evaluation may be necessary to confirm the diagnosis when there is a clinical suspicion of TSC [88], comprehensive of brain (usually with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)) and heart imaging and genetic evaluation.

RADIOLOGICAL FINDINGS

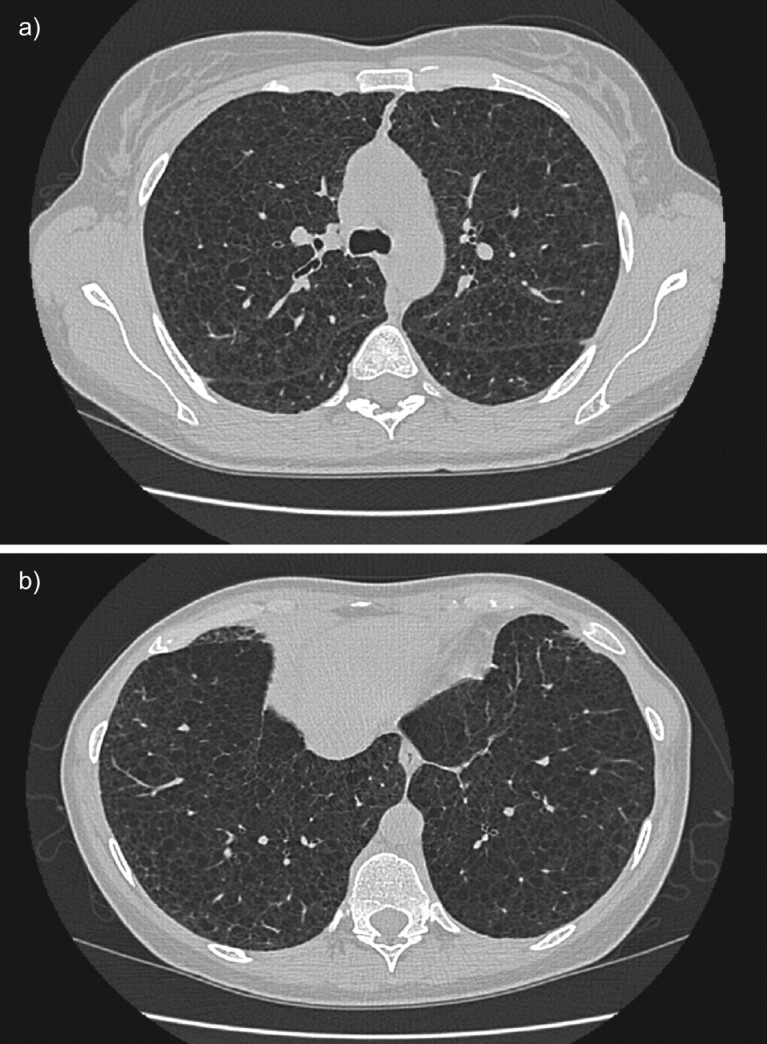

The chest radiograph often appears normal in early disease, although it may show pleural effusions or pneumothorax. In more advanced disease a reticulonodular pattern and cysts or bullae are the most common findings. (figs 5 and 6) The characteristic abnormality on lung CT scans in patients with LAM is the presence of well circumscribed, round and thin-walled cysts that are scattered in a bilateral roughly symmetric pattern, without any lobar predominance [89–91]. These cysts range in size from barely perceptible to several centimetres and in number from a few scattered cysts to near complete replacement of the lung parenchyma (fig. 7).

Figure 5.

Chest radiograph in lymphangioleiomyomatosis showing bilateral reticular changes.

Figure 6.

Chest radiograph in lymphangioleiomyomatosis showing bilateral pleural effusion and interstitial changes. Thoracentesis confirmed the presence of chylous pleural effusion.

Figure 7.

High-resolution computed tomography scans of the chest in a patient with histological diagnosis of lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Round shaped, thin-walled cysts are distributed diffusely throughout the lungs (a) without sparing of lung bases (b).

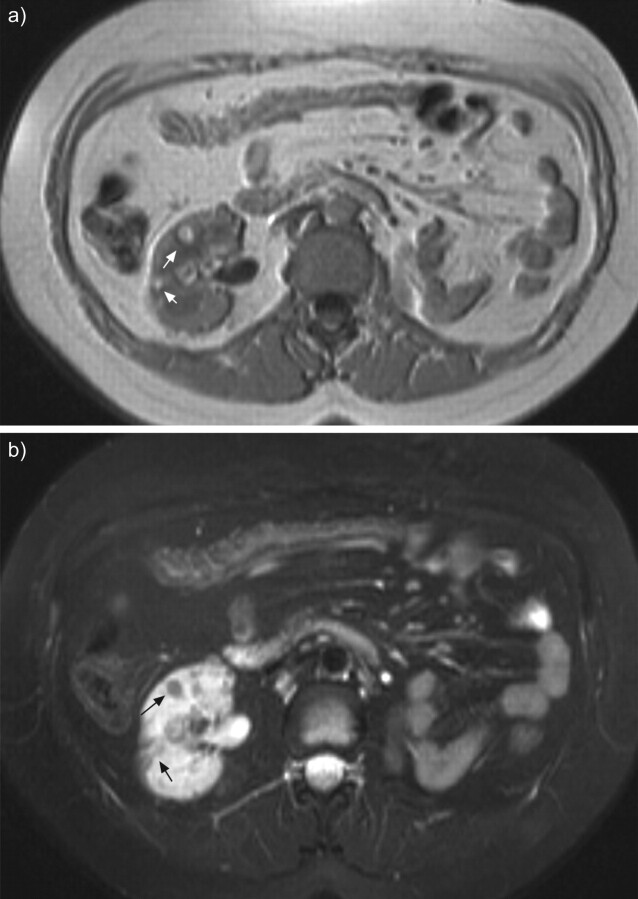

Angiomyolipoma can usually be identified by CT because of the presence of fat, which gives lesions a characteristic CT appearance. MRI may be adequate for the diagnosis when iodinated contrast is contraindicated (fig. 8) [92]. Diagnostic difficulty may arise in the small number of angiomyolipomas showing little evidence of fat; in these cases, tissue biopsy may be necessary to differentiate angiomyolipomas from renal cell carcinoma. Other extrapulmonary findings include lymphangioleiomyomas and ascites [84, 85]. Lymphangioleiomyomas are usually localised in the mediastinum, retroperitoneum, and pelvis along the axial lymphatics and can appear larger in the evening due to accumulation of chyle in the cystic structures [86].

Figure 8.

Abdominal magnetic resonance imaging of a patient with tuberous sclerosis complex lymphangioleiomyomatosis and multiple small renal angiomyolipomas (arrows) in T1-weighted images (a) and fat suppression signal sequences (b). Left nephrectomy was performed for a large angiomyolipoma.

DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA AND DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Recently, guidelines for the diagnosis, assessment and treatment of LAM have been published by the European Respiratory Society LAM task force [93]. The guidelines highlight diagnostic criteria and management including current available treatment of the disease and its complications.

Diagnostic criteria

On the basis of pathologic and clinical findings, extrapulmonary manifestations and CT scans the diagnosis of LAM can be define as definite, probable or possible [93]. According to these criteria, a characteristic lung CT in a female renders lung biopsy not necessary for a definite diagnosis if any of the following extrapulmonary manifestations is present: AML, thoracic or abdominal chylous effusion, lymphangioleiomyoma or biopsy-proven lymph node involved by LAM, and definite or probable TSC. High-resolution CT (HRCT) is the recommended imaging technique for LAM. The diagnosis of LAM is probable when a characteristic lung CT is found in a patient with compatible clinical history or when compatible CT features are present in a patient with angiomyolipoma or chylous effusion. Characteristic HRCT findings are multiple (more than 10) thin-walled round well-defined air-filled cysts with no other significant pulmonary involvement with the exception of possible features of multifocal micronodular pneumocyte hyperplasia (a hamartomatous process of the lung that exhibits multiple small nodules) in patients with TSC. When only few (more than two and fewer than 10) typical cysts are present, HRCT features are compatible with pulmonary LAM. Characteristic or compatible HRCT alone with no other suggestive clinical feature makes the diagnosis of LAM possible, but is not sufficient for a definite diagnosis.

Differential diagnosis

When all criteria for definite LAM are not satisfied, a certain diagnosis of the disease requires exclusion of the alternative causes of cystic lung disease. The primary differential diagnosis includes pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) and emphysema. The smoking history and the morphology of the cysts can be helpful in differentiating these disorders from LAM [94–96]. LCH is characterised by irregularly shaped thicker walled cysts, which involve predominantly the middle and upper lobes, and are often associated to nodular lesions. Typical lung parenchyma changes of emphysema are devoid of distinct walls. Less common diseases that should also be considered in differential diagnosis include Sjögren syndrome, lymphocytic interstitial pneumonitis, hypersensitivity pneumonitis, amyloidosis, light chain-deposition disease, low-grade leiomyosarcomas, metastatic endometrial stromal cell sarcoma [97–101], and Birt–Hogg–Dubé (BHD) syndrome, a rare tumour suppressor syndrome that is associated with spontaneous pneumothorax, skin manifestations, pulmonary cysts, and various types of renal tumours [102].

It has been reported that LAM cells express VEGF-D, a lymphangiogenic growth factor. Serum VEGF-D levels have been shown to be higher in patients with LAM than in healthy volunteers and patients with other cystic lung diseases [103]. Therefore, a serum VEGF-D level of >800 pg·mL−1 in a female with typical lung cystic changes on HRCT scan has been proven to be diagnostically specific for S-LAM and identifies LAM in females with TSC [104]. Finally, its levels have been correlated to more severe disease [105]. Thus, serum VEGF-D may be a useful biomarker for differential diagnosis and prognostic evaluation of LAM.

Finally, LAM can be confused with lymphangiomatosis, a rare disease that is associated with abdominal and thoracic lymphatic smooth muscle infiltration, lymphadenopathy and lymphangiomas and can involve the lung. But as opposed to LAM, it affects both males and females and does not generate lung cysts [106].

TREATMENT

Pulmonary and abdominal complications

Conservative treatment could be the initial approach to pneumothorax. But if the air leak persists or if the pneumothorax recurs, surgical pleurodesis should be performed; as an alternative chemical pleurodesis may be performed in individual casesin [107]. Chylothorax is often difficult to treat and pleurodesis is frequently necessary, a low-fat diet and therapeutic thoracentesis may be the initial approach [79, 108]. Thoracic duct ligation has also been performed safely in LAM. Octreotide is a long-acting somatostatin analogue that slows the production of chyle through reduction in splanchnic blood flow. Although case reports and series have shown that octreotide is probably effective for the treatment of chylous complications in other diseases [109, 110], it can cause gallstones and the experience is too limited to recommend it in LAM patients.

Asymptomatic small renal AML (<4 cm) should not be treated; yearly follow-up should be performed by ultrasound, or CT or MRI when ultrasound measurements are unreliable due to technical factors. Larger asymptomatic AML at an increased risk for bleeding should be followed twice yearly to evaluate growth [93]. Symptomatic AMLs should be treated as conservatively as possible to preserve renal function. Both embolisations and nephron sparing surgery have been performed safely [79, 111]. Although no trials have compared the two strategies, embolisation may be preferred in patients with active bleeding, while nephron sparing surgery may be used when a malignant lesion is suspected [93].

A proven therapeutic intervention is not currently available for lymphangioleiomyomas.

Treatment with bronchodilators is recommended for 20% of patients who have a significant positive response to bronchodilators [112, 113]; there is no evidence that corticosteroids are helpful. Oxygen, where appropriate, pulmonary rehabilitation and prophylactic vaccinations are other important measures.

Hormonal therapy

At present no effective treatment for LAM is available. Since LAM affects predominantly pre-menopausal females and can worsen during pregnancy, and after the administration of oestrogens [114, 115], various hormonal strategies have been used in the treatment of the disease. Effects of bilateral oophorectomy are controversial, and there is no objective evidence of improvement with anti-oestrogen therapy [78, 116]. There have been reports of improvement with Gonadotrophin-releasing hormone (GnRH) analogues but other studies were inconclusive and no placebo-controlled clinical trials on GnRH analogues are available [117–121].

The use of progesterone became the standard of care after a series of case reports and clinical studies [122, 123]. A retrospective study found a nonsignificant reduction in the rate of decline in forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) and a significant reduction in the rate of decline in carbon monoxide diffusing capacity of the lung (DL,CO) in patients treated with progesterone compared with untreated patients [124]. Another retrospective study of 275 patients with LAM showed that the overall yearly rates of decline of FEV1 and DL,CO for patients who received oral or intramuscular progesterone were not significantly different from patients who were not treated with progesterone [125]. There have been no controlled trials of progesterone in patients with LAM.

In conclusion, hormone treatment should be discouraged except in individual cases with rapid progression of the disease in which progesterone may be trialled.

Future therapeutic issues

Recent progress in our understanding of the molecular pathogenesis of LAM and muscle cell biology provides a foundation for the development of new therapeutic strategies. Inhibitors of mTOR and inhibitors of MMPs and angiogenesis are the most promising areas of research.

Inhibitors of mTOR

Sirolimus is an antifungal macrolide antibiotic currently in use for the prevention of allograft rejection after solid organ transplantation. Because of its inhibitory effect of mTOR-mediated proliferation and growth of LAM cells in vitro, it has been studied as a possible treatment for LAM.

The Cincinnati Angiomyolipoma Sirolimus Trial was a pilot study involving 25 patients with AMLs, including 18 with LAM. After 1 yr receiving sirolimus, AML volume decreased by almost 50%, and airflow measurements of FEV1 and forced vital capacity increased by 5 to 10% [126]. The improvements in AML and FEV1 were reduced after therapy cessation but not back to baseline values. Interim analysis of a similar trial in seven patients with TSC and six patients with S-LAM showed analogous results regarding AML volume [127]. In both studies there were adverse events such as frequent aphthous ulcers, diarrhoea and upper respiratory infections. FEV1 response is the primary outcome of the Multicenter International LAM Efficacy of Sirolimus (MILES) Trial, a larger, randomised controlled trial which opened in 2006.

mTOR inhibitors can regulate major functional activities of osteoclasts, including the production of cathepsin-K whose expression has been recently found to be strongly present in LAM cells [70], as mentioned above. Thus, it is possible to speculate that mTOR inhibitors may exert part of their action also by limiting the destructive remodelling of lung structure.

An open-label, nonrandomised, within-subject dose escalation safety, tolerability and efficacy study of everolimus (a second generation mTOR inhibitor) in females with sporadic or TSC-LAM is ongoing.

Inhibitors of MMPs and angiogenesis

Doxycyline, an inhibitor of MMPs [128], may be an efficacious treatment of pulmonary capillary haemangiomatosis [129], a disorder in which angiogenesis is related to MMP activity. Recently, Moses et al. [130] reported a case of a patient with advanced pulmonary LAM whose FEV1 and levels of oxygen saturation at rest and on exercise significantly improved in association with reduction of urinary MMPs after treatment with doxycycline. Further studies are required to confirm this interesting observation, and a clinical trial is now ongoing in UK.

Another possible target for future treatment of LAM is lymphangiogenesis. Recent data on mice suggest that the crucial angiogenic factor VEGF may be important in the progression of LAM lesions [131]. Moreover, results in a series of surgical and autopsy cases of LAM showed that VEGF-C is overexpressed in LAM lesions where it is associated with the excessive growth of lymphatics [74]. VEGF-D was elevated in the serum of patients with LAM and may be a biomarker for the disease [102]. Antibody inhibitors of VEGF pathways have been developed and some are in clinical trials for different solid tumours [132–134].

Other potential targets in LAM include the farnesylated protein Rheb and growth factor receptor tyrosine kinases located upstream of the deregulated hamartin–tuberin–mTOR pathway. Imanitib, an effective tyrosine kinase inhibitor, and farnesyltransferase inhibitors targeting Rheb may be objects for further studies [53, 135, 136]. Statins, which inhibit 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzymeA (HMGCoA), have been found to inhibit the growth of TSC2-/- cells in vitro, although, to date, no therapeutic effect has been found with statins in in vivo studies of TSC disease. Furthermore a retrospective review of 335 patients with LAM showed a significantly greater yearly rate of decline of DL,CO % predicted in LAM patients on statins in comparison with their matched controls [137].

As for other rare diseases, research into LAM has been strongly limited by a relative inability to capture sufficiently large patient populations. The recently established international LAM registry is a component of a set of web-based resources, including a patient self-report data portal, aimed at accelerating research in rare diseases in a rigorous fashion and is an example of how such a collaboration between clinicians, researchers, advocacy groups and patients can create an essential community resource infrastructure, and thus accelerate rare disease research [138].

Footnotes

Provenance

Submitted article, peer reviewed.

Support Statement

J. Moss was supported by the Intramural Research Program, National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, Bethesda, MD, USA.

Statement of Interest

None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kitaichi M, Nishimura K, Itoh H, et al. Pulmonary lymphangiomyomatosis: a report of 46 patients including a clinicopathologic study of prognostic factors. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1995; 151: 527–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Urban T, Lazor R, Lacronique J, et al. Pulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis: a study of 69 patients. Groupe d'Etudes et de Recherche sur les Maladies “Orphelines” Pulmonaires (GERM“O”P). Medicine (Baltimore) 1999; 78: 321–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chu SC, Horiba K, Usuki J, et al. Comprehensive evaluation of 35 patients with lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Chest 1999; 115: 1041–1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johnson SR, Tattersfield AE. Clinical experience of lymphangioleiomyomatosis in the UK. Thorax 2000; 55: 1052–1057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ryu JH, Moss J, Beck GJ, et al. The NHLBI Lymphangioleiomyomatosis Registry: characteristics of 230 patients at enrollment. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006; 173: 105–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Costello LC, Hartman TE, Ryu JH. High frequency of pulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis in women with tuberous sclerosis complex. Mayo Clin Proc 2000; 75: 591–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Franz DN, Brody A, Meyer C, et al. Mutational and radiographic analysis of pulmonary disease consistent with lymphangioleiomyomatosis and micronodular pneumocyte hyperplasia in women with tuberous sclerosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001; 164: 661–668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moss J, Avila NA, Barnes PM, et al. Prevalence and clinical characteristics of lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM) in patients with tuberous sclerosis complex. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001; 164: 669–671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sparagana SP, Roach ES. Tuberous sclerosis complex. Curr Opin Neurol 2000; 13: 115–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Juvet SC, McCormack FX, Kwiatkowski DJ, et al. Molecular pathogenesis of lymphangioleiomyomatosis: lessons learned from orphans. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2006; 38: 398–408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Taveira-DaSilva AM, Moss J. Lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Cancer Control 2006; 13: 276–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhe X, Schuger L. Combined smooth muscle and melanocytic differentiation in lymphangioleiomyomatosis. J Histochem Cytochem 2004; 52: 1537–1542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matsumoto Y, Horiba K, Usuki J, et al. Markers of cell proliferation and expression of melanosomal antigen in lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 1999; 21: 327–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Finlay G. The LAM cell: what is it, where does it come from, and why does it grow? Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2004; 286: L690–L693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brentani MM, Carvalho CR, Saldiva PH, et al. Steroid receptors in pulmonary lymphangiomyomatosis. Chest 1984; 85: 96–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Logginidou H, Ao X, Russo I, et al. Frequent estrogen and progesterone receptor immunoreactivity in renal angiomyolipomas from women with pulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Chest 2000; 117: 25–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barberis M, Monti GP, Ziglio G, et al. Oestrogen and progesterone receptors detection in pulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1996; 153: 271. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pea M, Bonetti F, Zamboni G, et al. Melanocyte-marker-HMB-45 is regularly expressed in angiomyolipoma of the kidney. Pathology 1991; 23: 185–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Avila NA, Dwyer AJ, Rabel A, et al. Sporadic lymphangioleiomyomatosis and tuberous sclerosis complex with lymphangioleiomyomatosis: comparison of CT features. Radiology 2007; 242: 277–285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bissler JJ, Kingswood JC. Renal angiomyolipomata. Kidney Int 2004; 66: 924–934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kwiatkowski DJ. Tuberous sclerosis: from tubers to mTOR. Ann Hum Genet 2003; 67: 87–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Crooks DM, Pacheco-Rodriguez G, DeCastro RM, et al. Molecular and genetic analysis of disseminated neoplastic cells in lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2004; 101: 17462–17467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karbowniczek M, Astrinidis A, Balsara BR, et al. Recurrent lymphangiomyomatosis after transplantation: genetic analyses reveal a metastatic mechanism. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2003; 167: 976–982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yu J, Astrinidis A, Henske EP. Chromosome 16 loss of heterozygosity in tuberous sclerosis and sporadic lymphangiomyomatosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001; 164: 1537–1540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sato T, Seyama K, Fujii H, et al. Mutational analysis of the TSC1 and TSC2 genes in Japanese patients with pulmonary lymphangileiomyomatosis. J Hum Genet 2002; 47: 20–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smolarek TA, Wessner LL, McCormack FX, et al. Evidence that lymphangiomyomatosis is caused by TSC2 mutations: chromosome 16p13 loss of heterozygosity in angiomyolipomas and lymph nodes from women with lymphangiomyomatosis. Am J Hum Genet 1998; 62: 810–815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carsillo T, Astrinidis A, Henske EP. Mutations in the tuberous sclerosis complex gene TSC2 are a cause of sporadic pulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2000; 97: 6085–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Knudson AG, Jr. Mutation and cancer: statistical study of retinoblastoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1971; 68: 820–823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van Slegtenhorst M, de Hoogt R, Hermans C, et al. Identification of the tuberous sclerosis gene TSC1 on chromosome 9q34. Science 1997; 277: 805–808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.The European Chromosome 16 Tuberous Sclerosis Consortium. Identification and characterization of the tuberous sclerosis gene on chromosome 16. Cell 1993; 75: 1305–1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rosner M, Freilinger A, Hengstschlager M. Proteins interacting with the tuberous sclerosis gene products. Amino Acids 2004; 27: 119–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lamb RF, Roy C, Diefenbach TJ, et al. The TSC1 tumour suppressor hamartin regulates cell adhesion through ERM proteins and the GTPase Rho. Nat Cell Biol 2000; 2: 281–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Haddad LA, Smith N, Bowser M, et al. The TSC1 tumor suppressor hamartin interacts with neurofilament-L and possibly functions as a novel integrator of the neuronal cytoskeleton. J Biol Chem 2002; 277: 44180–44186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van Slegtenhorst M, Nellist M, Nagelkerken B, et al. Interaction between hamartin and tuberin, the TSC1 and TSC2 gene products. Hum Mol Genet 1998; 7: 1053–1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maheshwar MM, Sandford R, Nellist M, et al. Comparative analysis and genomic structure of the tuberous sclerosis 2 (TSC2) gene in human and pufferfish. Hum Mol Genet 1996; 5: 131–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dan HC, Sun M, Yang L, et al. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt pathway regulates tuberous sclerosis tumor suppressor complex by phosphorylation of tuberin. J Biol Chem 2002; 277: 35364–35370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Inoki K, Li Y, Zhu T, et al. TSC2 is phosphorylated and inhibited by Akt and suppresses mTOR signalling. Nat Cell Biol 2002; 4: 648–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ma L, Chen Z, Erdjument-Bromage H, et al. Phosphorylation and functional inactivation of TSC2 by Erk implications for tuberous sclerosis and cancer pathogenesis. Cell 2005; 121: 179–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li Y, Inoki K, Vacratsis P, et al. The p38 and MK2 kinase cascade phosphorylates tuberin, the tuberous sclerosis 2 gene product, and enhances its interaction with 14–3-3. J Biol Chem 2003; 278: 13663–13671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Roux PP, Ballif BA, Anjum R, et al. Tumor-promoting phorbol esters and activated Ras inactivate the tuberous sclerosis tumor suppressor complex via p90 ribosomal S6 kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2004; 101: 13489–13494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Soucek T, Pusch O, Wienecke R, et al. Role of the tuberous sclerosis gene-2 product in cell cycle control. J Biol Chem 1997; 272: 29301–29308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lamb RF, Roy C, Diefenbach TJ, et al. The TSC1 tumour suppressor hamartin regulates cell adhesion through ERM proteins and the GTPase Rho. Nat Cell Biol 2000; 2: 281–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Johnson MW, Emelin JK, Park SH, et al. Co-localization of TSC1 and TSC2 gene products in tubers of patients with tuberous sclerosis. Brain Pathol 1999; 9: 45–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fukuda T, Kobayashi T, Momose S, et al. Distribution of Tsc1 protein detected by immunohistochemistry in various normal rat tissues and the renal carcinomas of Eker rat: detection of limited colocalization with Tsc1 and Tsc2 gene products in vivo. Lab Invest 2000; 80: 1347–1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Johnson MW, Kerfoot C, Bushnell T, et al. Hamartin and tuberin expression in human tissues. Mod Pathol 2001; 14: 202–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Catania MG, Johnson MW, Liau LM, et al. Hamartin expression and interaction with tuberin in tumor cell lines and primary cultures. J Neurosci Res 2001; 63: 276–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schmelzle T, Hall MN. TOR, a central controller of cell growth. Cell 2000; 103: 253–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Barbet NC, Schneider U, Helliwell SB, et al. TOR controls translation initiation and early G1 progression in yeast. Mol Biol Cell 1996; 7: 25–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Garami A, Zwartkruis FJ, Nobukuni T, et al. Insulin activation of Rheb, a mediator of mTOR/S6K/4E-BP signaling, is inhibited by TSC1 and 2. Mol Cell 2003; 11: 1457–1466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Inoki K, Li Y, Xu T, et al. Rheb GTPase is a direct target of TSC2 GAP activity and regulates mTOR signaling. Genes Dev 2003; 17: 1829–1834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Saucedo LJ, Gao X, Chiarelli DA, et al. Rheb promotes cell growth as a component of the insulin/TOR signaling network. Nat Cell Biol 2003; 5: 566–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang Y, Gao X, Saucedo LJ, et al. Rheb is a direct target of the tuberous sclerosis tumour suppressor proteins. Nat Cell Biol 2003; 5: 578–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Li Y, Inoki K, Guan KL. Biochemical and functional characterizations of small GTPase Rheb and TSC2 GAP activity. Mol Cell Biol 2004; 24: 7965–7975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nellist M, Sancak O, Goedbloed MA, et al. Distinct effects of single amino-acid changes to tuberin on the function of the tuberin-hamartin complex. Eur J Hum Genet 2005; 13: 59–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dan HC, Sun M, Yang L, et al. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt pathway regulates tuberous sclerosis tumor suppressor complex by phosphorylation of tuberin. J Biol Chem 2002; 277: 35364–35370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Inoki K, Li Y, Zhu T, et al. TSC2 is phosphorylated and inhibited by Akt and suppresses mTOR signalling. Nat Cell Biol 2002; 4: 648–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ma L, Chen Z, Erdjument-Bromage H, et al. Phosphorylation and functional inactivation of TSC2 by Erk implications for tuberous sclerosis and cancer pathogenesis. Cell 2005; 121: 179–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Li Y, Inoki K, Vacratsis P, et al. The p38 and MK2 kinase cascade phosphorylates tuberin, the tuberous sclerosis 2 gene product, and enhances its interaction with 14-3-3. J Biol Chem 2003; 278: 13663–13671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Inoki K, Zhu T, Guan KL. TSC2 mediates cellular energy response to control cell growth and survival. Cell 2003; 115: 577–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Finlay GA, York B, Karas RH, et al. Estrogen-induced smooth muscle cell growth is regulated by tuberin and associated with altered activation of platelet-derived growth factor receptor-beta and ERK-1/2. J Biol Chem 2004; 279: 23114–23122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Simoncini T, Hafezi-Moghadam A, Brazil DP, et al. Interaction of oestrogen receptor with the regulatory subunit of phophastidylinositol-3-OH kinase. Nature 2000; 407: 538–541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Flores-Delgado G, Anderson KD, Warburton D. Nongenomic estrogen action regulates tyrosine phosphatase activity and tuberin stability. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2003; 199: 143–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yu J, Astrinidis A, Howard S, et al. Estradiol and tamoxifen stimulate LAM-associated angiomyolipoma cell growth and activate both genomic and nongenomic signaling pathways. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2004; 286: L694–L700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.York B, Lou D, Panettieri RA, Jr, et al. Cross-talk between tuberin, calmodulin, and estrogen signaling pathways. FASEB J 2005; 19: 1202–1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yu JJ, Robb VA, Morrison TA, et al. Estrogen promotes the survival and pulmonary metastasis of tuberin-null cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2009; 106: 2635–2640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Crawford HC, Matrisian LM. Tumor and stromal expression of matrix metalloproteinases and their role in tumor progression. Invasion Metastasis 1994; 14: 234–245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Matsui K, Takeda K, Yu ZX, et al. Downregulation of estrogen and progesterone receptors in the abnormal smooth muscle cells in pulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis following therapy: an immunohistochemical study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000; 161: 1002–1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Matsui K, Takeda K, Yu ZX, et al. Role for activation of matrix metalloproteinases in the pathogenesis of pulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2000; 124: 267–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hayashi T, Fleming MV, Stetler-Stevenson WG, et al. Immunohistochemical study of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and their tissue inhibitors (TIMPs) in pulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM). Hum Pathol 1997; 28: 1071–1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chilosi M, Pea M, Martignoni G, et al. Cathepsin-K expression in pulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Mod Pathol 2009; 22: 161–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bromme D, Okamoto K, Wang BB, et al. Humancathepsin O2, a matrix protein-degrading cysteine protease expressed in osteoclasts. Functional expression of human cathepsin O2 in Spodoptera frugiperda and characterization of the enzyme. J Biol Chem 1996; 271: 2126–2132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Merrilees MJ, Hankin EJ, Black JL, et al. Matrix proteoglycans and remodelling of interstitial lung tissue in lymphangioleiomyomatosis. J Pathol 2004; 203: 653–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kumasaka T, Seyama K, Mitani K, et al. Lymphangiogenesis in lymphangioleiomyomatosis: its implication in the progression of lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Am J Surg Pathol 2004; 28: 1007–1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kumasaka T, Seyama K, Mitani K, et al. Lymphangiogenesis mediated shedding of LAM cell clusters as a mechanism for dissemination in lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Am J Surg Pathol 2005; 29: 1356–1366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Travis WD, Usuki J, Horiba K, et al. Histopathologic studies on lymphangioleiomyomatosis. In: Moss J, ed. LAM and other Diseases Characterized by Smooth Muscle Proliferation New York, Marcel Dekker, Inc., 1999; pp. 171–217. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Juvet SC, McCormack FX, Kwiatkowski DJ, et al. Molecular pathogenesis of lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2007; 36: 398–408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Taveira-Dasilva AM, Stylianou MP, Hedin CJ, et al. Bone mineral density in lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005; 171: 61–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Taylor JR, Ryu J, Colby TV, et al. Lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Clinical course in 32 patients. N Engl J Med 1990; 323: 1254–1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ryu JH, Doerr CH, Fisher SD, et al. Chylothorax in lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Chest 2003; 123: 623–627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bissler JJ, Kingswood JC. Renal angiomyolipomata. Kidney Int 2004; 66: 924–934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.L'Hostis H, Deminiere C, Ferriere JM, et al. Renal angiomyolipoma: a clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and follow-up study of 46 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 1999; 23: 1011–1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Bernstein SM, Newell JD, Jr, Adamczyk D, et al. How common are renal angiomyolipomas in patients with pulmonary lymphangiomyomatosis? Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1995; 152: 2138–2143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Maziak DE, Kesten S, Rappaport DC, et al. Extrathoracic angiomyolipomas in lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Eur Respir J 1996; 9: 402–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Avila NA, Kelly JA, Chu SC, et al. Lymphangioleiomyomatosis: abdominopelvic CT and US findings. Radiology 2000; 216: 147–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Matsui K, Tatsuguchi A, Valencia J, et al. Extrapulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM): clinicopathologic features in 22 cases. Hum Pathol 2000; 31: 1242–1248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Avila NA, Bechtle J, Dwyer AJ, et al. Lymphangioleiomyomatosis: CT of diurnal variation of lymphangioleiomyomas. Radiology 2001; 221: 415–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Moss J, DeCastro R, Patronas NJ, et al. Meningiomas in lymphangioleiomyomatosis. JAMA 2001; 286: 1879–1881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Roach ES, DiMario FJ, Kandt RS, et al. Tuberous Sclerosis Consensus Conference: recommendations for diagnostic evaluation. National Tuberous Sclerosis Association. J Child Neurol 1999; 14: 401–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Merchant RN, Pearson MG, Rankin RN, et al. Computerized tomography in the diagnosis of lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Am Rev Respir Dis 1985; 131: 295–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Avila NA, Chen CC, Chu SC, et al. Pulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis: correlation of ventilation-perfusion scintigraphy, chest radiography, and CT with pulmonary function tests. Radiology 2000; 214: 441–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Avila NA, Kelly JA, Dwyer AJ, et al. Lymphangioleiomyomatosis: correlation of qualitative and quantitative thin-section CT with pulmonary function tests and assessment of dependence on pleurodesis. Radiology 2002; 223: 189–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Helenon O, Merran S, Paraf F, et al. Unusual fat-containing tumors of the kidney: a diagnostic dilemma. Radiographics 1997; 17: 129–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Johnson SR, Cordier JF, Lazor R, et al. European Respiratory Society guidelines for the diagnosis and management of lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Eur Respir J 2010; 35: 14–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Koyama M, Johkoh T, Honda O, et al. Chronic cystic lung disease: diagnostic accuracy of high-resolution CT in 92 patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2003; 180: 827–835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Harari S, Paciocco G. An integrated clinical approach to diffuse cystic lung diseases. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis 2005; 22: Suppl. 1, S31–S39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Paciocco G, Uslenghi E, Bianchi A, et al. Diffuse cystic lung diseases: correlation between radiologic and functional status. Chest 2004; 125: 135–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Jeong YJ, Lee KS, Chung MP, et al. Amyloidosis and lymphoproliferative disease in Sjogren syndrome: thin-section computed tomography findings and histopathologic comparisons. J Comput Assist Tomogr 2004; 28: 776–781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Johkoh T, Muller NL, Pickford HA, et al. Lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia: thin-section CT findings in 22 patients. Radiology 1999; 212: 567–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Silva CI, Churg A, Muller NL. Hypersensitivity pneumonitis: spectrum of high-resolution CT and pathologic findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2007; 188: 334–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Colombat M, Stern M, Groussard O, et al. Pulmonary cystic disorder related to light chain deposition disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006; 173: 777–780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Aubry MC, Myers JL, Colby TV, et al. Endometrial stromal sarcoma metastatic to the lung: a detailed analysis of 16 patients. Am J Surg Pathol 2002; 26: 440–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Ayo DS, Aughenbaugh GL, Yi ES, et al. Cystic lung disease in Birt–Hogg–Dube syndrome. Chest 2007; 132: 679–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Young LR, Inoue J, McCormack FX. Diagnostic potential of serum VEGF-D for lymphangioleiomyomatosis. N Engl J Med 2008; 358: 199–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Young LR, Vandyke R, Gulleman PM, et al. Serum vascular endothelial growth factor-D prospectively distinguishes lymphangioleiomyomatosis from other diseases. Chest 2010; 138: 674–681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Glasgow CG, Avila NA, Lin JP, et al. Serum vascular endothelial growth factor-D levels in patients with lymphangioleiomyomatosis reflect lymphatic involvement. Chest 2009; 135: 1293–1300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Faul JL, Berry GJ, Colby TV, et al. Thoracic lymphangiomas,lymphangiectasis, lymphangiomatosis, and lymphatic dysplasia syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000; 161: 1037–1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Almoosa KF, Ryu JH, Mendez J, et al. Management of pneumothorax in lymphangioleiomyomatosis: effects on recurrence and lung transplantation complications. Chest 2006; 129: 1274–1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Almoosa KF, McCormack FX, Sahn SA. Pleural disease in lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Clin Chest Med 2006; 27: 355–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Kalomenidis I. Octreotide and chylothorax. Curr Opin Pulm Med 2006; 12: 264–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Demos NJ, Kozel J, Scerbo JE. Somatostatin in the treatment of chylothorax. Chest 2001; 119: 964–966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Hsu TH, O'Hara J, Mehta A, et al. Nephron-sparing nephrectomy for giant renal angiomyolipoma associated with lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Urology 2002; 59: 138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Taveira-DaSilva AM, Hedin C, Stylianou MP, et al. Reversible airflow obstruction, proliferation of abnormal smooth muscle cells, and impairment of gas exchange as predictors of outcome in lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001; 164: 1072–1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Taveira-DaSilva AM, Steagall WK, Rabel A, et al. Reversible airflow obstruction in lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Chest 2009; 136: 1596–1603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Brunelli A, Catalini G, Fianchini A. Pregnancy exacerbating unsuspected mediastinal lymphangioleiomyomatosis and chylothorax. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 1996; 52: 289–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Yano S. Exacerbation of pulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis by exogenous oestrogen used for infertility treatment. Thorax 2002; 57: 1085–1086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Eliasson AH, Phillips YY, Tenholder MF. Treatment of lymphangioleiomyomatosis: a meta-analysis. Chest 1989; 96: 1352–1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Rossi GA, Balbi B, Oddera S, et al. Response to treatment with an analog of luteinizing-hormone-releasing hormone in a patient with pulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Am Rev Respir Dis 1991; 143: 174–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Medeiros P, Jr, Kairalla RA, Pereira CAC, et al. GnRH analogs X progesterone-lung function evolution in two treatment cohort groups in lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM). Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2003; 167: A953. [Google Scholar]

- 119.de la Fuente J, Parámo C, Román F, et al. Lymphangioleiomyomatosis: unsuccessful treatment with luteinizing-hormone-releasing hormone analogues. Eur J Med 1993; 2: 377–378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Zahner J, Borchard F, Fischer H, et al. Successful therapy of a post-partum lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Case report and literature review. Schweiz Med Wochenschr 1994; 124: 1626–1632. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Harari S, Cassandro R, Chiodini I, et al. Effect of a gonadotrophin-releasing hormone analogue on lung function in lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Chest 2008; 133: 448–454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.McCarty KS, Mossler JA, McLelland R, et al. Pulmonary lymphangiomyomatosis responsive to progesterone. N Engl J Med 1980; 303: 1461–1465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Sieker HO, McCarty KS, Jr. Lymphangiomyomatosis: a respiratory illness with an endocrinologic therapy. Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc 1987; 99: 57–67. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Johnson SR, Tattersfield AE. Decline in lung function in lymphangioleiomyomatosis: relation to menopause and progesterone treatment. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1999; 160: 628–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Taveira-Dasilva AM, Stylianou MP, Hedin CJ, et al. Decline in lung function in patients with lymphangioleiomyomatosis treated with or without progesterone. Chest 2004; 126: 1867–1874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Bissler JJ, McCormack FX, Young LR, et al. Sirolimus for angiomyolipoma in tuberous sclerosis complex or lymphangioleiomyomotosis. N Engl J Med 2008; 358: 140–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Davies DM, Johnson SR, Tattersfield AE, et al. Sirolimus therapy in tuberous sclerosis or sporadic Lymphangioleiomyomatosis. N Engl J Med 2008; 358: 200–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Schneider BS, Maimon J, Golub LM, et al. Tetracyclines inhibit intracellular muscle proteolysis in vitro. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1992; 188: 767–772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Ginns LC, Roberts DH, Mark EJ, et al. Pulmonary capillary hemangiomatosis with atypical endotheliomatosis: successful antiangiogenic therapy with doxycycline. Chest 2003; 124: 2017–2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Moses MA, Harper J, Folkman J. Doxycycline treatment for lymphangioleiomyomatosis with urinary monitoring for MMPs. N Engl J Med 2006; 354: 2621–2622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.El-Hashemite N, Walker V, Kwiatkowski DJ. Estrogen enhances whereas tamoxifen retards development of Tsc mouse liver hemangioma: a tumor related to renal angiomyolipoma and pulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Cancer Res 2005; 65: 2474–2481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Mendel DB, Laird AD, Smolich BD, et al. Development of SU5416, a selective small molecule inhibitor of VEGF receptor tyrosine kinase activity, as an anti-angiogenesis agent. Anticancer Drug Des 2000; 15: 29–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Mross K, Drevs J, Muller M, et al. Phase I clinical and pharmacokinetic study of PTK/ZK, a multiple VEGF receptor inhibitor, in patients with liver metastases from solid tumours. Eur J Cancer 2005; 41: 1291–1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Jones-Bolin S, Zhao H, Hunter K, et al. The effects of the oral, pan-VEGF-R kinase inhibitor CEP-7055 and chemotherapy in orthotopic models of glioblastoma and colon carcinoma in mice. Mol Cancer Ther 2006; 5: 1744–1753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Fritz G, Kaina B. Rho GTPases: promising cellular targets for novel anticancer drugs. Curr Cancer Drug Targets 2006; 6: 1–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Gau CL, Kato-Stankiewicz J, Jiang C, et al. Farnesyltransferase inhibitors reverse altered growth and distribution of actin filaments in Tsc-deficient cells via inhibition of both rapamycin-sensitive and -insensitive pathways. Mol Cancer Ther 2005; 4: 918–926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.El-Chemaly S, Taveira-Da Silva A, Stylianou MP, et al. Statins in lymphangioleiomyomatosis: a word of caution. Eur Respir J 2009; 34: 513–520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Nurok M, Eslick I, Carvalho CR, et al. The international LAM registry: a component of an innovative web-based clinician, researcher, and patient-driven rare disease research platform. Limphat Res Biol 2010; 8: 81–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]