Abstract

Small RNA regulatory pathways are used to control the activity of transposons, regulate gene expression and resist infecting viruses. We examined the biogenesis of mRNA-derived endogenous short-interfering RNAs (endo-siRNAs) in the disease vector mosquito, Aedes aegypti. Under standard conditions, mRNA-derived endo-siRNAs were produced from the bidirectional transcription of tail-tail overlapping gene pairs. Upon infection with the alphavirus, Sindbis virus (SINV), another class of mRNA-derived endo-siRNAs was observed. Genes producing SINV-induced endo-siRNAs were not enriched for overlapping partners or nearby genes, but were enriched for transcripts with long 3'UTRs. Endo-siRNAs from this class derived uniformly from the entire length of the target transcript, and were found to regulate the transcript levels of the genes from which they were derived. Strand-specific qPCR experiments demonstrated that antisense strands of targeted mRNA genes were produced to exonic, but not intronic regions. Finally, small RNAs mapped to both sense and antisense strands of exon-exon junctions, suggesting double-stranded RNA precursors to SINV-induced endo-siRNAs may be synthesized from mature mRNA templates. These results suggest additional complexity in small RNA pathways and gene regulation in the presence of an infecting virus in disease vector mosquitoes.

Keywords: endo-siRNA, Sindbis virus, RNAi, small RNA, Aedes aegypti

INTRODUCTION

Small RNA regulatory pathways represent an ancient means of controlling the expression of genes. In Drosophila, the miRNA (~22nt) pathway has become specialized to regulate the transcript levels and translational status of mRNA genes, while the piRNA (23–30nt) pathway ensures the maintenance of germline integrity in the face of transposon activity. In contrast, the short-interfering RNA (siRNA, 21 nt) pathway acts primarily to silence invading viruses or somatic transposon activity. Loss of the siRNA pathway or suppression of its activity in Drosophila results in an increase in transposon mRNA expression (Chung et al. 2008; Czech et al. 2008; Ghildiyal et al. 2008) and hypersensitivity to virus infection and pathogenicity (Berry et al. 2009; Galiana-Arnoux et al. 2006; Nayak et al. 2010; Wang et al. 2006).

The siRNA pathway can be further subdivided into endogenous (endo-siRNA) and exogenous (exo-siRNA) components based on the source of the double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) trigger. In flies, the endo-siRNA pathway is known to be triggered by dsRNA produced through the transcription of structured loci such as hairpin RNAs (Czech et al. 2008; Okamura et al. 2008b) or through the convergent transcription of overlapping genes (Czech et al. 2008; Ghildiyal et al. 2008; Okamura et al. 2008a). In the absence of a 3' partner gene, transcription of antisense strands has also been shown to produce dsRNA to mRNA-encoding genes that is capable of entering the siRNA pathway and initiating silencing (Hartig et al. 2009). Hairpin-derived (hp) siRNAs appear to be biologically active, as the major hp-siRNA derived from hp-CG4068B has been shown to repress mus308 transcripts (Czech et al. 2008; Okamura et al. 2008b). A specific biological role for endo-siRNAs derived from 3' overlapping mRNA-encoding genes (cis-NAT pairs) has not yet been found, as loss of RNAi components did not appear to alter the expression levels of endo-siRNA producing genes (Czech et al. 2008; Okamura et al. 2008a). However, several recent studies have shown that flies which lack the ability to produce endo-siRNAs are less robust than their wild-type counterparts. Such endo-siRNA deficient flies are not able to compensate for temperature perturbations during development (Lucchetta et al. 2009), and have a reduced lifespan and lower stress tolerance (Lim et al. 2011) compared to endo-siRNA producing cohorts.

Whereas in these cases the dsRNA trigger derives from nuclear transcription, the exo-siRNA pathway is triggered by cytoplasmic dsRNA derived from infecting viruses or in vitro transcribed molecules. In Drosophila, both the endo- and exo-siRNA pathways utilize dicer-2 for dsRNA cleavage and an argonaute-2-led complex (RISC) for slicing, but these pathways differ in the small dsRNA binding proteins involved in RISC loading (Hartig et al. 2009; Hartig and Forstemann 2011; Miyoshi et al. 2010; Zhou et al. 2009). Likewise, both the exo-siRNA and endo-siRNA, but not the miRNA pathway, are effectively suppressed by the expression of the Flock House virus B2 protein (Berry et al. 2009; Fagegaltier et al. 2009), which is known to antagonize the siRNA pathway by binding to both long dsRNA (preventing dicer-cleavage) and siRNA duplexes (preventing RISC-loading) (Aliyari et al. 2008; Chao et al. 2005; Lu et al. 2005). The B2 protein of the related Nodamura virus (NoV) has been shown to function in a similar manner (Aliyari et al. 2008; Johnson et al. 2004; Korber et al. 2009; Li et al. 2004).

In worms, fungi, and plants, a significant source of dsRNA also derives from the activity of one or more RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRP) gene products (Cogoni and Macino 1999; Dalmay et al. 2000; Smardon et al. 2000). While these “canonical” RdRP genes appear to share a common ancestor, this lineage appears to have been lost in most animal species, including flies and vertebrates (Zong et al. 2009) and is consistent with an observed lack of transitive RNAi in these species (Roignant et al. 2003).

Aedes aegypti mosquitoes are the natural vectors of a number of human disease agents, such as the viruses which cause dengue and yellow fever. A short generation time and sequenced genome (Nene 2007), combined with a close evolutionary relationship with a diverse array of human pathogens makes this mosquito an excellent system for studying the natural interplay between RNA viruses and the invertebrate siRNA pathway. In this paper we describe a class of endo-siRNAs that are specifically induced by Sindbis virus (SINV) infection in Ae. aegypti and target mRNA-encoding genes. SINV-induced endo-siRNAs were suppressed in the presence of the Nodamura virus (NoV) B2 protein, indicating their production through a dsRNA trigger. The biogenesis of SINV-induced endo-siRNAs was not consistent with convergent transcription, hairpin, or pseudogene models, suggesting additional complexity in the endo-siRNA pathway.

RESULTS

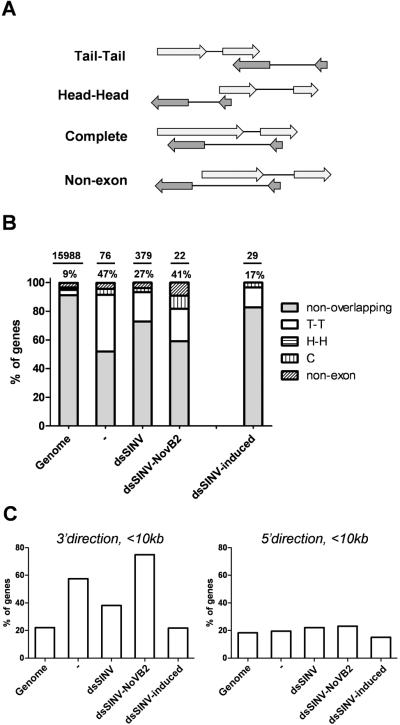

SINV induces the production of a class of endo-siRNAs

To determine if SINV infection had any effect on the endo-siRNA pathway, small RNAs from uninfected Ae. aegypti or SINV-infected Ae. aegypti were mapped to the reference genome. We obtained 1,391,941 unique-mapping 18–24 nt reads for uninfected Ae. aegypti; 1,727,318 such reads for dsSINV-infected mosquitoes; and 604,042 reads for dsSINV-NoVB2-infected mosquitoes. Of these, 26511 (1.9%), 52963 (3.1%), and 17432 (2.9%) mapped to genomic intervals annotated as being part of mRNA-encoding genes. In Drosophila, transcript-derived siRNAs are produced from genes with overlapping 3' ends. To determine if this was also the case for Ae. aegypti, we compared siRNA-producing genes with the current annotation, classifying each gene as either non-overlapping or as having one of four categories of overlap (Fig. 1A). To restrict our analysis to true siRNA-producing genes, candidate genes were required to produce at least 10 small RNA mapping reads, as well as possess a peak length of 21 nt (calculated as more than 67% of reads between 20–22 nt being exactly 21 nt). Using these criteria, we identified at least 76 genes that produced siRNAs in Ae. aegypti (Table S1 and S2). As expected, almost half of these could be classified as a form of overlapping gene, with a predominance for tail-tail overlap as in D. melanogaster (Fig. 1B, Table S1). As there are only 307 tail-tail overlapping pairs currently annotated in the Ae. aegypti genome (~3.8% of total genes), this represents a substantial enrichment and confirms that tail-tail overlapping genes are a major source of mRNA-derived endo-siRNAs in Ae. aegypti. Surprisingly, the bias towards tail-tail overlapping genes was reduced in dsSINV-infected mosquitoes, and was restored in the presence of the B2 suppressor of RNA silencing (Fig. 1B). This suggested the existence of a class of endo-siRNAs that appear only in the presence of SINV. Indeed, while 73 out of 76 endo-siRNA producing genes from uninfected mosquitoes also met our criteria in dsSINV-infected mosquitoes, we identified a subset of genes that produced more than 30 mapping reads in the presence of dsSINV, but less than 5 reads from uninfected mosquitoes (Table 1). Endo-siRNAs from these genes were suppressed in the presence of the B2 protein, suggesting that the biogenesis of these molecules was occurring through the dicer-mediated cleavage of dsRNA (Table 1). When only considering these dsSINV-induced endo-siRNA genes, the bias towards tail-tail overlapping genes shrank even further (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1. Steady-state, but not dsSINV-induced, endo-siRNAs derive primarily from overlapping gene pairs in Ae. aegypti.

(A) The four categories of overlapping gene considered in this study. (B) The percentage of each overlapping gene category was calculated for the entire Ae. aegypti mRNA gene set (genome), as well as for genes producing endo-siRNAs in uninfected (−), dsSINV-infected, or dsSINV-NoVB2-infected Ae. aegypti. Bars represent the percentage of genes annotated as non-overlapping; tail-tail (T-T); head-head (H-H); complete (C); or non-exon overlapping (non-exon). Percentages above each bar represent the sum of all four categories of overlap. Numbers above horizontal bars indicate the total number of genes used in the analysis. (C) For the genes identified as “non-overlapping”, the distance to the nearest mRNA-encoding gene on the opposing strand was calculated for both the 5' (upstream) and 3' (downstream) directions.

Table 1.

Ae. aegypti endo-siRNAs induced by dsSINV infection.

| Raw reads |

Normalized |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| - | dsSINV | dsSINV-NoVB2 | - | dsSINV | dsSINV-NoVB2 | |

| AAEL010787 | 0 | 407 | 14 | 0 | 269a | 19b |

| AAEL004865 | 0 | 378 | 12 | 0 | 250a | 17b |

| AAEL017419 * | 0 | 216 | 3 | 0 | 143a | 4b |

| AAEL010318 | 1 | 110 | 7 | 1 | 73a | 10b |

| AAEL016995 | 1 | 71 | 12 | 1 | 47a | 17b |

| AAEL008785 | 0 | 71 | 2 | 0 | 47a | 3b |

| AAEL014185 * | 0 | 66 | 2 | 0 | 44a | 3b |

| AAEL017516 | 1 | 64 | 5 | 1 | 42a | 7b |

| AAEL008257 | 1 | 61 | 2 | 1 | 40a | 3b |

| AAEL008107 | 3 | 53 | 6 | 3 | 35a | 8b |

| AAEL008103 | 0 | 53 | 6 | 0 | 35a | 8b |

| AAEL012359 | 3 | 52 | 0 | 3 | 34a | 0b |

| AAEL001420 | 3 | 52 | 5 | 3 | 34a | 7b |

| AAEL002144 | 4 | 51 | 2 | 4 | 34a | 3b |

| AAEL012736 | 2 | 50 | 6 | 2 | 33a | 8b |

| AAEL002185 | 0 | 48 | 1 | 0 | 32a | 1b |

| AAEL001421 | 1 | 46 | 4 | 1 | 30a | 6b |

| AAEL017356 | 0 | 43 | 1 | 0 | 28a | 1b |

| AAEL000066 | 0 | 41 | 5 | 0 | 27a | 7b |

| AAEL007778 | 0 | 39 | 3 | 0 | 26a | 4b |

| AAEL008054 | 1 | 36 | 4 | 1 | 24a | 6b |

| AAEL007103 | 1 | 34 | 5 | 1 | 22a | 7b |

| AAEL017144 | 0 | 34 | 0 | 0 | 22a | 0b |

| AAEL001113 | 0 | 33 | 0 | 22a | 3b | |

| AAEL017054 | 3 | 32 | 7 | 3 | 21a | 10bb |

| AAEL000032 | 3 | 32 | 6 | 3 | 21a | 8b |

| AAEL004329 | 4 | 30 | 4 | 4 | 20a | 6b |

| AAEL006498 | 0 | 30 | 4 | 0 | 20a | 6b |

| AAEL001082 | 0 | 30 | 0 | 0 | 20a | 0b |

Gene AAEL0014185 is entirely encompassed by the larger AAEL017419 on the same genomic interval in the same orientation. Thus, in this case the reads for this interval have been distributed evenly between these two potential transcripts in the region of overlap.

Overexpressed in comparison to levels in the uninfected control library (p-value of <0.01)

Underexpressed in comparison to levels in the dsSINV library (p-value of <0.01)

Underexpressed in comparison to levels in the dsSINV library (p-value of <0.05)

As the annotation of the Ae. aegypti genome is still relatively immature, we reasoned that incomplete gene models such as missing exons might help explain the large number of non-overlapping genes found to produce endo-siRNAs (~50% in uninfected mosquitoes, >80% in dsSINV-induced). To determine if this was the case, we calculated the distance from each non-overlapping, siRNA-producing gene to the nearest gene model on the opposing strand in both the 5' and 3' directions. Consistent with the importance of tail-tail pairs in endo-siRNA biogenesis, non-overlapping endo-siRNA producing genes from uninfected mosquitoes were enriched for nearby 3' partners, with almost 60% of genes having a partner located within 10 kb (Fig. 1C). As the average intron size for Ae. aegypti is close to 5 kb (Nene et al. 2007), it seems likely that much, if not all, transcript-derived endo-siRNA production in the absence of SINV can be explained via convergent transcription. However, this bias for nearby 3' partners was reduced in dsSINV-infected mosquitoes, and was completely eliminated when only dsSINV-induced siRNA producing genes were considered (Fig. 1C). This suggests a form of endo-siRNA biogenesis that is not dependent on convergent transcription occurs in the presence of dsSINV, and can be suppressed by B2 (Fig. 1C).

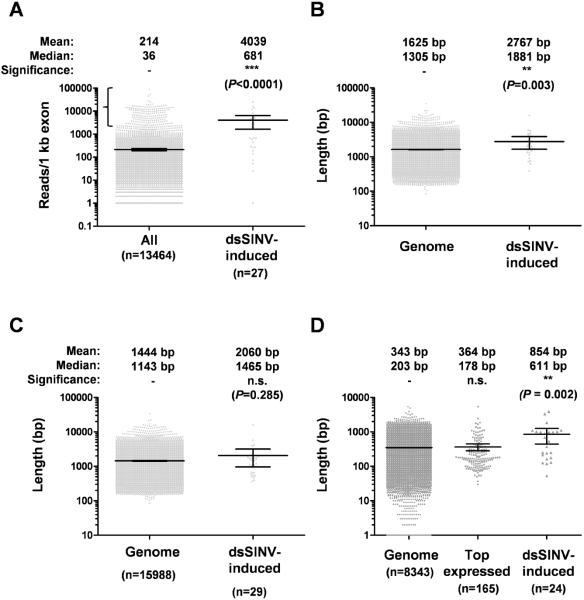

dsSINV-induced endo-siRNAs derive preferentially from abundant transcripts with long 3'UTRs

Bonizzoni et al (2011) recently performed an mRNAseq analysis on 3–5 day old Liverpool strain Ae. aegypti fed on sugar alone (our small RNA libraries derive from this same strain at 4 days post emergence). Of the 29 dsSINV-induced endo-siRNA genes identified in Table 1, 27 produced at least 1 mapping read in the Bonizzoni et al (2011) mRNAseq data. When the abundance of these gene transcripts was considered relative to all expressed genes, we observed a significant enrichment for abundant transcripts (Fig. 2A). dsSINV-induced endo-siRNA-producing genes were also found to be enriched in longer transcripts (Fig. 2B), a trend which could be explained by the length of the 3'UTR (Compare Fig. 2, panels C+D). In fact, in 11 out of 24 (45.8%) dsSINV-induced endo-siRNA genes the 3'UTR was annotated at greater than 800 bp (the remaining 5 genes did not contain a 3'UTR annotation). This contrasts with 10.8% of all genes with annotated 3'UTRs, and 10.9% of the top 200 expressed genes, indicating that this bias could not be explained by a more complete annotation due to higher sequencing coverage of ESTs. Within dsSINV-induced endo-siRNA genes, we observed a significant positive correlation between the number of endo-siRNAs produced and the length of the annotated 3'UTR, while no correlation was found between overall endo-siRNA production and transcript length (minus 3'UTR) or transcript abundance (Table 2). Thus we conclude that transcripts with long 3'UTRs are the preferred targets for the generation of dsSINV-induced endo-siRNAs.

Figure 2. dsSINV-induced, mRNA-derived endo-siRNAs derive from abundant transcripts with unusually long 3'UTRs.

(A) Normalized expression of Ae. aegypti gene transcripts (All) or transcripts corresponding to dsSINV-induced endo-siRNA genes. Horizontal bar indicates the mean; error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals. Region denoted by bracket indicates the top 200 expressed genes. Predicted length of mRNA transcripts in the current annotation (Genome) or in dsSINV-induced endo-siRNA producing genes either in total (B), without 3'UTR (C) or 3'UTR alone (D). Statistical significance was determined using the Mann Whitney test [pairwise comparisons for A, B and C], or the Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn's Multiple Comparison test [three-way comparison for D].

Table 2.

Correlation between transcript length, abundance and endo-siRNA production.

| Length 3'UTR | Endo-siRNA abundance | Transcript abundance | Transcript length (total) | Transcript length (minus 3'UTR) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Length 3'UTR |

0.498

(P=0.013) |

−0.180 (P=0.400) |

0.572

(P=0.003) |

−0.040 (P=0.852) |

|

| Endo-siRNA abundance | −0.032 (P=0.881) |

0.291 (P=0.168) |

−0.013 (P=0.953) |

||

| Transcript abundance | −0.297 (P=0.159) |

−0.229 (P=0.282) |

|||

| Transcript length (total) |

0.796

(P<0.0001) |

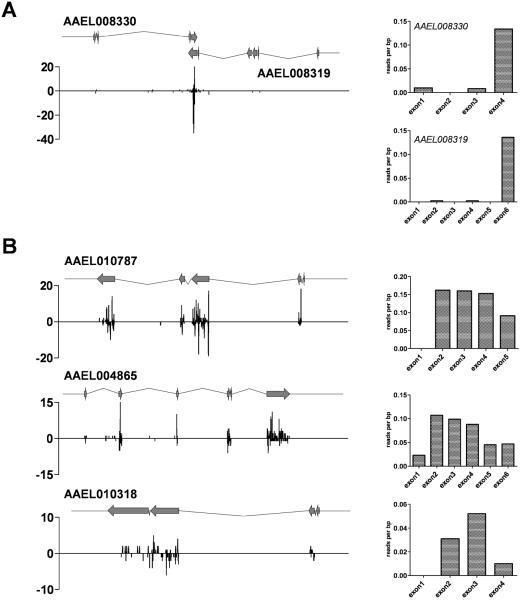

dsSINV-induced endo-siRNAs derive from the complete length of the transcript

In Drosophila, convergently transcribed genes produce siRNAs that derive specifically from the region of overlap. In fact, the presence of endo-siRNAs mapping outside of regions of annotated overlap has resulted in the revision of gene models (Okamura et al. 2008a). Similarly, examination of a ~40 kb locus encompassing the tail-tail overlapping gene pair AAEL008330-AAEL008319 shows that siRNAs map preferentially to the region of overlap, with a strong bias for siRNAs being derived from the final exon (Fig. 3A). In contrast, the distribution of unique-mapping small RNAs to three of the top four dsSINV-induced endo-siRNA producing genes (AAEL017419 was omitted from this analysis as two of its three exons are not unique in the genome) revealed that dsSINV-induced endo-siRNAs were derived uniformly from the entire transcript, with a decrease in siRNA production occurring at both the 5' and 3' ends (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3. dsSINV-induced endo-siRNAs derive from the entire mRNA.

Endo-siRNA distributions on genomic intervals for a tail-tail overlapping gene pair which produces small RNAs in the absence of dsSINV (A), or from genes which produce endo-siRNAs only upon dsSINV infection (B). Y-axis indicates the number of unique-mapping 21 nt small RNAs per 20 nt bin, with neighboring bins overlapping by 10nt. Gene structure is indicated by block arrows (exons) and bent lines (introns). Bar graphs indicate the normalized distribution of unique-mapping 21 nt small RNAs per nucleotide of exon.

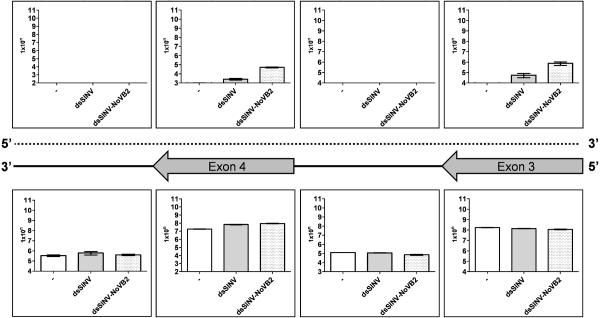

The current Ae. aegypti annotation predicts that while genes AAEL004865 and AAEL010318 appear to be non-overlapping, the top dsSINV-induced endo-siRNA producing gene, AAEL010787, has a tail-tail overlapping partner (AAEL010788). We performed 3' RACE for both genes AAEL010787 and AAEL010788 in order to confirm the extent of this overlap, and determined that the overlapping region was a meager 4 bp. However, it was possible that run-on transcription from gene AAEL010788 could be responsible for the production of the second RNA strand, allowing for the formation of dsRNA which could then enter the RNAi pathway. A prediction of this hypothesis is that on the AAEL010787, transcript-derived strand, exons and introns will have different abundances due to the accumulation of mature mRNA. In contrast, the opposing strand will not undergo splicing and thus the abundance of RNA corresponding to this strand would be expected to be equivalent over the same exonic and intronic regions. To test this idea, we designed eight strand-specific real-time qPCR assays targeting the genomic interval corresponding to gene AAEL010787 (exons 3–4, introns 3–4). As shown in Fig. 4, both assays that targeted exonic regions on the mRNA-encoding strand of AAEL010787 detected between 107–108 copies of RNA per μg of total RNA for uninfected Ae. aegypti, Ae. aegypti infected with dsSINV or dsSINV-NoVB2. As expected, intron abundances were ~1000-fold lower, indicating efficient splicing of this transcript. In uninfected Ae. aegypti, the levels of opposing strand RNA were below the level of detection for all four assays employed, consistent with a lack of endo-siRNA generation at this locus in the absence of SINV (Fig. 4). In contrast, AAEL010787-opposing strand RNA was detected in both exonic assays for dsSINV-infected and dsSINV-NoVB2 infected mosquitoes, but not from either intronic assay, even though the limits of detection were similar (Fig. 4). Abundances of AAEL010787-opposing strand RNA were about 10-fold higher in the presence of the B2 suppressor of RNAi, potentially due to ability of this protein to protect the resultant dsRNA from dicer cleavage. These data are not consistent with a model of dsRNA production through antisense transcription, and suggest an alternative method for the generation of dsRNA.

Figure 4. dsSINV-induced endo-siRNAs do not appear to derive from antisense or run-on transcription.

Each bar graph displays the quantification of the top or bottom (coding) strand transcripts corresponding to gene AAEL010787 in uninfected (−) Ae. aegypti, or in Ae. aegypti four days after infection with dsSINV or dsSINV-NoVB2 viruses. Assays corresponding to exonic (block arrows), intronic (solid lines), or antisense strand (dotted line) regions are indicated.

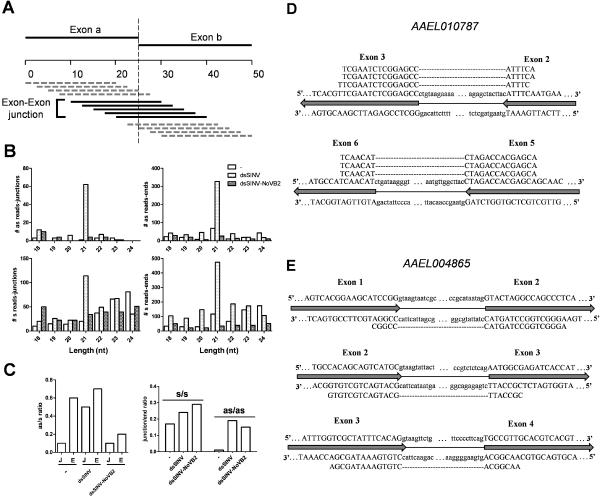

dsSINV-induced endo-siRNAs can cross splice junctions on antisense strands

To determine if small RNAs derived from antisense strands crossed exon-exon boundaries, we re-mapped our three small RNA libraries to a set of 50 bp sequences constructed from every potential splice junction in the current Ae. aegypti annotation, with the first and last 25 bp derived from each respective exon (sequences less than 50 bp due to extremely short exons were excluded). Small RNA reads that mapped with at least 6 bp on either side of the exon-exon boundary were classified as being derived from splice junctions (Brooks et al. 2011), while the remaining mapping reads were classified as coming from exon ends (Fig. 5A). For dsSINV-infected mosquitoes, 21 nt small RNAs were the predominant size class mapping to the antisense strand of both exon-exon junctions and exon ends (Fig. 5B). A similar trend was observed for sense-mapping reads, though we observed an increase in other size classes potentially representing mRNA degradation products (Fig. 5B). When the 21 nt mapping reads were compared, we observed that in uninfected Ae. aegypti, these reads mapped to both the sense and antisense strands at the ends of exons in a ratio of approximately 2:1, while 21 nt small RNAs mapping to exon-exon junctions were heavily biased towards the sense strand (Fig. 5C). In contrast, the ratio of sense to antisense small RNAs was similar between junctions and ends for dsSINV-infected mosquitoes (Fig. 5C). Likewise, the ratio of junction/end mapping reads was similar between sense and antisense mapping reads (Fig. 5C). Small RNA reads that mapped to the antisense strand across splice junctions were recovered for two of the four exon-exon junctions in gene AAEL010787 (Fig. 5D), and three out of five exon-exon junctions for gene AAEL004865 (Fig. 5E). For both of these genes, junction-mapping reads occurred in a manner roughly proportional to the length of the gene and number of potential junctions (3.3% and 1.9% of bases in genes AAEL010787 and AAEL004865 are candidates for junction mapping reads with 1.7%/2.9% of small RNAs mapping to these genes crossing exon-exon boundaries).

Figure 5. dsSINV-induced endo-siRNAs map to antisense strands of exon-exon junctions.

(A) Schematic representation of the exon-exon junction sequences used to map small RNA reads from each library, where the last 25 bp of each exon combined with the first 25 bp of the following exon for each gene in the gene set. Small RNAs with a 5' mapping position of 11–20 were counted as being derived from the exon-exon junction, with all other mapping positions considered being from the ends of their respective exons. (B) Length distribution of small RNAs mapping to the sense (s) or antisense (as) strand of exon-exon junctions or ends. (C) The ratio of sense (s) to antisense (as) and junction-mapping (J) to end-mapping (E) reads was plotted for each library for 21nt small RNAs. (D, E) Antisense small RNAs mapping to exon-exon junctions of genes AAEL010787 and AAEL004865; exons are indicated with block arrows with the corresponding bases capitalized. Introns are indicated with thin lines and lower case bases. Only the ends of introns are shown, with (…) indicating a jump in sequence. Small RNAs (shown as cDNA versions, for simplicity) mapping to the top or bottom strand of each sequence are indicated, with alignment gaps denoted by (---).

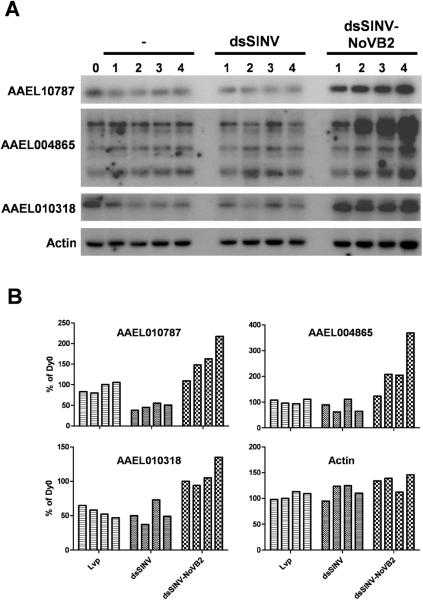

dsSINV-induced endo-siRNAs restrict transcript levels of the parent gene in an RNAi-dependant manner

In order to determine the biological relevance of dsSINV-induced endo-siRNA production, we followed the transcript levels of genes AAEL010787, AAEL004865 and AAEL010318 for four days after infection with dsSINV or dsSINV-NoVB2 (Fig. 6). Full-length transcript levels for gene AAEL010787 were reduced by about 50% in the presence of dsSINV, consistent with the idea that the induction of small RNAs targeting this gene are biologically active (Fig. 6). While the suppressive effect on AAEL004865 and AAEL010318 was less dramatic, the expression of all three genes increased substantially in the presence of the B2 suppressor of RNAi. Expression of a mosquito actin gene (Staley et al. 2010) did not change upon dsSINV infection or with the expression of the NoV-B2 suppressor, confirming the specificity of this response (Fig. 6). We conclude that the steady-state transcript levels of each of these genes are controlled by the RNAi pathway.

Figure 6. dsSINV-induced endo-siRNAs restrict the steady-state level of full-length target transcripts in an RNAi-dependant manner.

(A) Northern blot analysis was performed using total RNA derived from uninfected (−) Ae. aegypti, or Ae. aegypti infected with dsSINV or dsSINV-NoVB2 at 1, 2, 3, or 4 days post infection, as indicated. (B) Phosphorimager-based quantification of each blot, with RNA levels derived from the time of injections (Dy0) set to 100%. Where multiple isoforms are present, quantification was based on the longest isoform.

DISCUSSION

Dipteran small RNA regulatory pathways have been shown to be essential in antiviral and anti-transposon defense, as well as in modulating gene expression. Here we have presented evidence for the existence of a novel means of dsRNA production capable of targeting endogenous mRNA-encoding genes in the disease vector mosquito, Ae. aegypti. While convergently transcribed gene pairs were the primary source of mRNA-derived endo-siRNAs in uninfected mosquitoes, a novel class of mRNA-derived endo-siRNAs was detected upon infection with the alphavirus, Sindbis virus. These endo-siRNAs mapped to the entire length of the target transcripts and were found to cross exon-exon junctions on the antisense strand, the latter being suggestive of an RdRP-mediated biogenesis mechanism (Pak and Fire 2007).

Phylogenomic studies indicate that RdRP genes are not present in dipterans (Zong et al. 2009). Likewise, transitive RNAi, one of the hallmarks of RdRP activity in plants and nematodes, does not occur in Drosophila (Roignant et al. 2003). Finally, no biogenesis products which could indisputably be the result of RdRP activity have been observed in fruit flies, despite several reports detailing the sequencing of small RNA populations (Czech et al. 2008; Ghildiyal et al. 2008; Hartig et al. 2009; Okamura et al. 2008a). For example, Hartig et al (2009) were able to rule out an RdRP as a source of dsRNA in Drosophila S2 cells by noting that small RNAs derived from the white gene became scarce near exonexon boundaries, and never crossed them. A recent report (Lipardi and Paterson 2009) which challenged this notion was recently retracted (Lipardi and Paterson 2011). In mosquitoes, we have demonstrated previously that small RNAs produced from an EGFP-derived inverted repeat in transgenic Ae. aegypti do not spread to upstream or downstream locations on the target transcript, suggesting that like Drosophila, transitive RNAi does not occur in this mosquito (Adelman et al. 2008). Similarly, in this study we note that small RNAs derived from tail-tail overlapping gene pairs were restricted to the region of overlap. Considering all these factors, it seems unlikely that an endogenous RdRP is responsible for the generation of transcript-derived dsRNA in the presence of SINV, though we cannot rule this out completely.

As SINV also encodes its own RdRP gene, it is possible that it is this molecule, rather than an endogenously-encoded RdRP, that is responsible for the conversion of mature mRNA into dsRNA for RNAi-based processing. The SINV replication complex binds target RNA molecules and begins elongation with essential interactions occurring between the replicase and secondary structures present in both the 5' and 3' ends of the single stranded viral genome (Frolov et al. 2001). Despite the known requirements for efficient initiation mediated through the viral 3' conserved sequence element, it is possible that at some frequency the SINV replication complex is able to bind to the 3'UTR of a subset of mosquito transcripts and initiate synthesis of the complementary strand. It is possible that the long 3'UTRs typical of the RdRP-targeted genes we observed may contain structures or signals that are more likely to recruit SINV RdRP complexes. Further work is needed to determine if this is indeed the case.

It is not clear at this time whether the production of SINV-induced mRNA-derived endo-siRNAs occurs to the benefit of the infecting virus or the mosquito host. The generation of mRNA-derived dsRNA and subsequent reduction in target transcripts could potentially result in the depletion of important host factors required for viral replication. Such a scenario would offer the mosquito host added protection against SINV infection. Alternatively, SINV-directed production of endo-siRNAs may deplete one or more important antiviral activities. Indeed, the most highly targeted endo-siRNA gene we identified, AAEL010787, is orthologous to the Drosophila Dmp68/Rm62 RNA helicase gene- a known component of the Drosophila RNAi machinery (Ishizuka et al. 2002). A reduction in the steady-state levels of this protein might serve an immunosuppressive function, and investigations to determine whether the role of this gene is conserved in Ae. aegypti are ongoing.

Arbovirus infection of mosquitoes results in the up- or down-regulation of a multitude of transcripts (Sanders et al. 2005; Xi et al. 2008), though the specific mechanisms that underlie these changes are not known. Some of these transcriptional changes may result from pathogen recognition and subsequent immune activation, while others may result through the direct activation or repression of transcription by virally-encoded proteins. Our results suggest another mechanism whereby SINV infection results (either directly or indirectly) in the generation of dsRNA derived from a cohort of mosquito transcripts, resulting in repression of steady-state transcript levels. This suggests that monitoring transcriptional changes upon virus infection alone may not be sufficient to capture events where a host response is countered by virus-induced repression of transcripts.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Mosquitoes and viruses

The generation of recombinant Sindbis viruses has been described (2008). Female Ae. aegypti (Liverpool strain), were intrathoracically inoculated with 0.5 μl of a ~106 PFU/ml recombinant double subgenomic Sindbis virus TE/3'2J (dsSINV) suspension, or with a dsSINV-NovB2, that over-expresses the B2 protein of NoV. Bodies were snap frozen in liquid nitrogen at 1, 2, 3, and 4 days post injection and stored at −80°C until RNA extraction.

Northern analysis

Total RNA was extracted from whole female Ae. aegypti mosquitoes using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen; Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Five micrograms of RNA was electrophoresed in a denaturing gel and transferred to nylon membrane. Probes were generated by Reverse Transcription-Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR) using the One-Step RT-PCR kit (Qiagen; Valencia, CA) and the following gene specific primer pairs: AAEL010318F 5'-ACGTGTGCGAAGGACTGGAAATATTT-3' and AAEL010318R 5'-TACAATGGCTCGATTAACGGGAACAGAC-3', AAEL004865F 5'-AGGCCAGCCCTCAGTATGTCTGTCCC-3' and AAEL004865R 5'-CGTGACTGTTGTGAGCGTGATGTTCCGCGA-3', AAEL010787F 5'-CACATGGTTTGCTAATTAATACACTGGA-3' and AAEL010787R 5'-TGGAGCAAGTGCGCCCCGATCGTCAAAT-3', Act-2F 5'-ATGGTCGGTATGGGACAGAAGGACTC-3' and Act-8R 5'-GCTTCCATACCGAGGAACGATGGCTGG-3'. All PCR products were confirmed to be the gene of interest by sequence analysis. Probes were [α-32P]-dATP labeled through random-priming using the Amersham MegaPrime DNA labeling system (GE Healthcare; Buckinghamshire, UK). Membranes were hybridized overnight at 65°C and exposed to Kodak BioMax film or a phosphorimager cassette read by a STORM phosphorimager.

Strand-specific qPCR

Strand-specific qPCR was performed as described in Plaskon et al (2009) with the following modifications. To create strand-specific standards for intronic and exonic regions corresponding to the annotated AAEL010787 gene, primers F 5'TTTTGGATCCGAATCGCAAATAACAAACTTCAC-3' and R 5'-TTTTTCTAGAATTTAGGTGACACTATAGAAGGGGGAAGCAGAAGAGTGAGAAAAAAG-3' were used to amplify the genomic interval of interest from Ae. aegypti Liverpool strain using Platinum Pfx polymerase (Invitrogen; Carlsbad, CA). Underlined bases indicate restriction sites added for cloning. PCR products were digested with BamHI and XbaI and ligated into the BamHI/XbaI sites of pLitmus28i (New England Biolabs; Ipswich, MA). The molecular weight of the cloned AAEL010787 genomic fragment was calculated to be approximately 8.2×105 g/mol, yielding 7.3×1011 molecules per microgram of RNA. Following linearization by either XbaI for the AAEL010787 mRNA-encoding strand or XhoI for the opposite strand, in vitro transcription was performed using T7 RNA polymerase (New England Biolabs). In vitro transcribed RNA was extracted using TriReagent-RT (Molecular Research Center, Inc.; Cincinnati, OH) according to the manufacturer's instructions, precipitated in ethanol and resuspended in RNase-free water. Prior to reverse transcription, one microgram of synthesized RNA or mosquito total RNA was incubated with a tagged intron- or exon-specific primer (0.5μM; see Table S3) at 70°C for 5 minutes and then kept on ice for 2 minutes. Reverse transcription was carried out using SuperscriptII (Invitrogen) according to manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, samples were incubated at 50°C for 30 minutes followed by heat inactivation at 95°C for 15 minutes. cDNA was digested with ExonucleaseI (New England Biolabs) at 37°C for 30 minutes to remove any remaining primers, followed by a heat inactivation step at 70°C for 15 minutes.

Real-time qPCR was carried out using Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems; Foster City, CA) using primers indicated in Table S3 at a final concentration of 800μM. For each standard curve, cDNA was serially diluted to contain between 1010 and 102 molecules per microliter. Cycling conditions were as follows: 95°C for 10 min, 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 sec, 56°C for 30 sec, 72°C for 30 sec, followed by a dissociation curve consisting of 95°C for 15 sec, 60°C for 1 minute then constant fluorescence measurement during a slow ramp to 95°C (hold for 15 sec). QPCR was carried out in a StepOne Realtime PCR system (Applied Biosystems) and data was analyzed using the StepOne software v2.1 for quantitation using a standard curve (Applied Biosystems).

Small RNA libraries and bioinformatic analysis

Small RNA libraries were prepared from whole female mosquitoes 96 hr after virus infection, or from uninfected mosquitoes of the same age, as described previously (Myles et al. 2008), and were sequenced on the Illumina GAII platform. Raw sequence data have been deposited at the Gene Expression Omnibus (Accession number GSE35161). Following the bioinformatic removal of linker sequence, small RNAs were mapped to the Ae. aegypti genome [vectorbase release AaegL1, (Nene et al. 2007)] using Bowtie v0.12.7 (Langmead et al. 2009). Alignments were performed in v mode and were allowed to tolerate a single mismatch; the m parameter was used along with best and strata options to restrict the output to unique-mapping reads only. Intergenic distances, overlapping status, transcript length, and exon-exon junctions were calculated based on the AaegL1.2.gff3 annotation file downloaded from vectorbase dated Apr11, 2011. For mRNAseq data, small RNA reads were mapped to the Ae. aegypti genome using Bowtie in v mode allowing for 0–2 mismatches. To normalize small RNA read counts between libraries we used the edgeR software package (http://www.bioconductor.org/) (Robinson and Oshlack 2010). Differential expression between normalized read counts was determined by analysis with the A-C statistic (Audic and Claverie 1997).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank members of the Adelman and Myles labs for technical assistance.

FUNDING The work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (AI085091 to Z.N.A, AI77726 to K.M.M.) and by the Fralin Life Science Institute at Virginia Tech.

REFERENCES

- Adelman ZN, Anderson MA, Morazzani EM, Myles KM. A transgenic sensor strain for monitoring the RNAi pathway in the yellow fever mosquito, Aedes aegypti. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2008;38:705–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2008.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Afonina I, Ankoudinova I, Mills A, Lokhov S, Huynh P, Mahoney W. Primers with 5' flaps improve real-time PCR. Biotechniques. 2007;43:770, 772, 774. doi: 10.2144/000112631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aliyari R, Wu Q, Li HW, Wang XH, Li F, Green LD, Han CS, Li WX, Ding SW. Mechanism of induction and suppression of antiviral immunity directed by virus-derived small RNAs in Drosophila. Cell Host Microbe. 2008;4:387–97. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Audic S, Claverie JM. The significance of digital gene expression profiles. Genome Res. 1997;7:986–95. doi: 10.1101/gr.7.10.986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry B, Deddouche S, Kirschner D, Imler JL, Antoniewski C. Viral suppressors of RNA silencing hinder exogenous and endogenous small RNA pathways in Drosophila. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5866. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonizzoni M, Dunn WA, Campbell CL, Olson KE, Dimon MT, Marinotti O, James AA. RNA-seq analyses of blood-induced changes in gene expression in the mosquito vector species, Aedes aegypti. BMC Genomics. 2011;12:82. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-12-82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks AN, Yang L, Duff MO, Hansen KD, Park JW, Dudoit S, Brenner SE, Graveley BR. Conservation of an RNA regulatory map between Drosophila and mammals. Genome Res. 2011;21:193–202. doi: 10.1101/gr.108662.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao JA, Lee JH, Chapados BR, Debler EW, Schneemann A, Williamson JR. Dual modes of RNA-silencing suppression by Flock House virus protein B2. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2005;12:952–7. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung WJ, Okamura K, Martin R, Lai EC. Endogenous RNA interference provides a somatic defense against Drosophila transposons. Curr Biol. 2008;18:795–802. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cogoni C, Macino G. Gene silencing in Neurospora crassa requires a protein homologous to RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. Nature. 1999;399:166–9. doi: 10.1038/20215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czech B, Malone CD, Zhou R, Stark A, Schlingeheyde C, Dus M, Perrimon N, Kellis M, Wohlschlegel JA, Sachidanandam R, Hannon GJ, Brennecke J. An endogenous small interfering RNA pathway in Drosophila. Nature. 2008;453:798–802. doi: 10.1038/nature07007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalmay T, Hamilton A, Rudd S, Angell S, Baulcombe DC. An RNA-dependent RNA polymerase gene in Arabidopsis is required for posttranscriptional gene silencing mediated by a transgene but not by a virus. Cell. 2000;101:543–53. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80864-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagegaltier D, Bouge AL, Berry B, Poisot E, Sismeiro O, Coppee JY, Theodore L, Voinnet O, Antoniewski C. The endogenous siRNA pathway is involved in heterochromatin formation in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:21258–63. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809208105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frolov I, Hardy R, Rice CM. Cis-acting RNA elements at the 5' end of Sindbis virus genome RNA regulate minus- and plus-strand RNA synthesis. RNA. 2001;7:1638–51. doi: 10.1017/s135583820101010x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galiana-Arnoux D, Dostert C, Schneemann A, Hoffmann JA, Imler JL. Essential function in vivo for Dicer-2 in host defense against RNA viruses in drosophila. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:590–7. doi: 10.1038/ni1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghildiyal M, Seitz H, Horwich MD, Li C, Du T, Lee S, Xu J, Kittler EL, Zapp ML, Weng Z, Zamore PD. Endogenous siRNAs derived from transposons and mRNAs in Drosophila somatic cells. Science. 2008;320:1077–81. doi: 10.1126/science.1157396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartig JV, Esslinger S, Bottcher R, Saito K, Forstemann K. Endo-siRNAs depend on a new isoform of loquacious and target artificially introduced, high-copy sequences. EMBO J. 2009;28:2932–44. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartig JV, Forstemann K. Loqs-PD and R2D2 define independent pathways for RISC generation in Drosophila. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:3836–51. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishizuka A, Siomi MC, Siomi H. A Drosophila fragile X protein interacts with components of RNAi and ribosomal proteins. Genes Dev. 2002;16:2497–508. doi: 10.1101/gad.1022002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson KL, Price BD, Eckerle LD, Ball LA. Nodamura virus nonstructural protein B2 can enhance viral RNA accumulation in both mammalian and insect cells. J Virol. 2004;78:6698–704. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.12.6698-6704.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korber S, Shaik Syed Ali P, Chen JC. Structure of the RNA-binding domain of Nodamura virus protein B2, a suppressor of RNA interference. Biochemistry. 2009;48:2307–9. doi: 10.1021/bi900126s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langmead B, Trapnell C, Pop M, Salzberg SL. Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biol. 2009;10:R25. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-3-r25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li WX, Li H, Lu R, Li F, Dus M, Atkinson P, Brydon EW, Johnson KL, Garcia-Sastre A, Ball LA, Palese P, Ding SW. Interferon antagonist proteins of influenza and vaccinia viruses are suppressors of RNA silencing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:1350–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308308100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim DH, Oh CT, Lee L, Hong JS, Noh SH, Hwang S, Kim S, Han SJ, Lee YS. The endogenous siRNA pathway in Drosophila impacts stress resistance and lifespan by regulating metabolic homeostasis. FEBS Lett. 2011;585:3079–85. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2011.08.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipardi C, Paterson BM. Identification of an RNA-dependent RNA polymerase in Drosophila involved in RNAi and transposon suppression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:15645–50. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904984106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Lipardi C, Paterson BM. Retraction for Lipardi and Paterson, “Identification of an RNA-dependent RNA polymerase in Drosophila involved in RNAi and transposon suppression”. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:15010. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1111383108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu R, Maduro M, Li F, Li HW, Broitman-Maduro G, Li WX, Ding SW. Animal virus replication and RNAi-mediated antiviral silencing in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 2005;436:1040–3. doi: 10.1038/nature03870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucchetta EM, Carthew RW, Ismagilov RF. The endo-siRNA pathway is essential for robust development of the Drosophila embryo. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7576. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyoshi K, Miyoshi T, Hartig JV, Siomi H, Siomi MC. Molecular mechanisms that funnel RNA precursors into endogenous small-interfering RNA and microRNA biogenesis pathways in Drosophila. RNA. 2010;16:506–15. doi: 10.1261/rna.1952110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myles KM, Wiley MR, Morazzani EM, Adelman ZN. Alphavirus-derived small RNAs modulate pathogenesis in disease vector mosquitoes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:19938–43. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803408105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nayak A, Berry B, Tassetto M, Kunitomi M, Acevedo A, Deng C, Krutchinsky A, Gross J, Antoniewski C, Andino R. Cricket paralysis virus antagonizes Argonaute 2 to modulate antiviral defense in Drosophila. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17:547–54. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nene V, Wortman JR, Lawson D, Haas B, Kodira C, Tu ZJ, Loftus B, Xi Z, Megy K, Grabherr M, Ren Q, Zdobnov EM, Lobo NF, Campbell KS, Brown SE, Bonaldo MF, Zhu J, Sinkins SP, Hogenkamp DG, Amedeo P, Arensburger P, Atkinson PW, Bidwell S, Biedler J, Birney E, Bruggner RV, Costas J, Coy MR, Crabtree J, Crawford M, Debruyn B, Decaprio D, Eiglmeier K, Eisenstadt E, El-Dorry H, Gelbart WM, Gomes SL, Hammond M, Hannick LI, Hogan JR, Holmes MH, Jaffe D, Johnston JS, Kennedy RC, Koo H, Kravitz S, Kriventseva EV, Kulp D, Labutti K, Lee E, Li S, Lovin DD, Mao C, Mauceli E, Menck CF, Miller JR, Montgomery P, Mori A, Nascimento AL, Naveira HF, Nusbaum C, O'Leary S, Orvis J, Pertea M, Quesneville H, Reidenbach KR, Rogers YH, Roth CW, Schneider JR, Schatz M, Shumway M, Stanke M, Stinson EO, Tubio JM, Vanzee JP, Verjovski-Almeida S, Werner D, White O, Wyder S, Zeng Q, Zhao Q, Zhao Y, Hill CA, Raikhel AS, Soares MB, Knudson DL, Lee NH, Galagan J, Salzberg SL, Paulsen IT, Dimopoulos G, Collins FH, Birren B, Fraser-Liggett CM, Severson DW. Genome sequence of Aedes aegypti, a major arbovirus vector. Science. 2007;316:1718–23. doi: 10.1126/science.1138878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamura K, Balla S, Martin R, Liu N, Lai EC. Two distinct mechanisms generate endogenous siRNAs from bidirectional transcription in Drosophila melanogaster. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2008a;15:581–90. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamura K, Chung WJ, Ruby JG, Guo H, Bartel DP, Lai EC. The Drosophila hairpin RNA pathway generates endogenous short interfering RNAs. Nature. 2008b;453:803–6. doi: 10.1038/nature07015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pak J, Fire A. Distinct populations of primary and secondary effectors during RNAi in C. elegans. Science. 2007;315:241–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1132839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plaskon NE, Adelman ZN, Myles KM. Accurate strand-specific quantification of viral RNA. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7468. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson MD, Oshlack A. A scaling normalization method for differential expression analysis of RNA-seq data. Genome Biol. 2010;11:R25. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-3-r25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roignant JY, Carre C, Mugat B, Szymczak D, Lepesant JA, Antoniewski C. Absence of transitive and systemic pathways allows cell-specific and isoform-specific RNAi in Drosophila. RNA. 2003;9:299–308. doi: 10.1261/rna.2154103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders HR, Foy BD, Evans AM, Ross LS, Beaty BJ, Olson KE, Gill SS. Sindbis virus induces transport processes and alters expression of innate immunity pathway genes in the midgut of the disease vector, Aedes aegypti. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2005;35:1293–307. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2005.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smardon A, Spoerke JM, Stacey SC, Klein ME, Mackin N, Maine EM. EGO-1 is related to RNA-directed RNA polymerase and functions in germ-line development and RNA interference in C. elegans. Curr Biol. 2000;10:169–78. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00323-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staley M, Dorman KS, Bartholomay LC, Fernandez-Salas I, Farfan-Ale JA, Lorono-Pino MA, Garcia-Rejon JE, Ibarra-Juarez L, Blitvich BJ. Universal primers for the amplification and sequence analysis of actin-1 from diverse mosquito species. J Am Mosq Control Assoc. 2010;26:214–8. doi: 10.2987/09-5968.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang XH, Aliyari R, Li WX, Li HW, Kim K, Carthew R, Atkinson P, Ding SW. RNA interference directs innate immunity against viruses in adult Drosophila. Science. 2006;312:452–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1125694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xi Z, Ramirez JL, Dimopoulos G. The Aedes aegypti toll pathway controls dengue virus infection. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:e1000098. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou R, Czech B, Brennecke J, Sachidanandam R, Wohlschlegel JA, Perrimon N, Hannon GJ. Processing of Drosophila endo-siRNAs depends on a specific Loquacious isoform. RNA. 2009;15:1886–95. doi: 10.1261/rna.1611309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zong J, Yao X, Yin J, Zhang D, Ma H. Evolution of the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRP) genes: duplications and possible losses before and after the divergence of major eukaryotic groups. Gene. 2009;447:29–39. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2009.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.