Abstract

Using targeted exome sequencing we identified mutations in NNT, an antioxidant defence gene, in patients with familial glucocorticoid deficiency. In mice with Nnt loss, higher levels of adrenocortical cell apoptosis and impaired glucocorticoid production were observed. NNT knockdown in a human adrenocortical cell line resulted in impaired redox potential and increased ROS levels. Our results suggest that NNT may have a role in ROS detoxification in human adrenal glands.

Keywords: adrenal insufficiency, oxidative stress, reactive oxygen species, familial glucocorticoid deficiency

Familial Glucocorticoid Deficiency (FGD;OMIM 202200) is a rare autosomal recessive disorder characterized by an inability of the adrenal cortex to produce cortisol in response to stimulation by adrenocorticotropin hormone (ACTH). Patients typically present within the first few months of life with symptoms related to cortisol deficiency including recurrent illnesses/infections, hypoglycaemia, convulsions, failure to thrive and shock. The disease is life-threatening if untreated. 50% of FGD cases are caused by mutations in one of three genes; MC2R, MRAP or STAR, all encoding components of the ACTH signaling - steroidogenic pathway [1-3].

To search for further causal genes in FGD we carried out SNP array genotyping using the GeneChip Human Mapping 10K Array Xba142 (Affymetrix) in 9 probands from consanguineous families with FGD of unknown aetiology. Data analysis identified a candidate region, 5p13-q12 with linkage to 3 families (maximum HLOD score of 2.34). Genotyping of microsatellite markers confirmed homozygosity in this region only in affected family members and not in parents or unaffected siblings. Targeted exome sequencing of the proband from one kindred with chromosome 5-linkage identified 717 variants from the Feb. 2009 (NCBI37/hg19) human reference sequence assembly. Application of a filtration strategy (see methods) reduced the number of variants for validation to 5 (Supplementary Table 1). Only 1 variant, (c.1598C>T;p.Ala533Val) in nicotinamide nucleotide transhydrogenase (NNT) was homozygous in the affected patient, heterozygous in his parents and absent in controls (Supplementary Figure 1A). Homozygous NNT mutations, c.600-1delG at the splice junction of intron 4/exon 5 (predicted consequence p.Tyr201PhefsX2) and c.2930T>C; p.Leu977Pro within exon 20, were discovered in the two other chromosome 5-linked families (Supplementary Figure 1B). 18 further mutations in 12 kindreds were found in homozygosity or compound heterozygosity on sequencing of 100 patients with FGD of unknown cause (Table 1 and supplementary Figures 1[C&D] and 2). These mutations were spread throughout the gene and included abolition of the initiating methionine, two further splice mutations and many mis- and nonsense changes. No NNT mutations have previously been described in humans and none of the reported variants have been annotated in any SNP or mutation database including the 1000 genomes project and the NHLBI grand opportunity exome sequencing project in which >5,000 exomes have been sequenced [see URLs].

Table 1. NNT mutations in 15 kindreds with Familial Glucocorticoid Deficiency.

| Family | Nucleotide change | Protein change | Exon (intron) | Protein domain and/or consequence | Zygosity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1a,b | c.[1598C>T];[1598C>T] | p.[Ala533Val];[Ala533Val] | 11;11 | transmembrane | homo |

| 2a | c.[600-1delG];[600-1delG] | p.[Tyr201LysfsX1*];[Tyr201LysfsX1*] | intron4/exon5 | premature truncation aa 202 | homo |

| 3a | c.[2930T>C];[2930T>C] | p.[Leu977Pro];[Leu977Pro] | 20;20 | nucleotide binding | homo |

| 4 | c.[1310C>T];[1669C>T] | p.[Pro437Leu];[Gln557X] | 10;12 | transmembrane;truncation aa 557 | compound het |

| 5 | c.[1147C>T];[1147C>T] | p.[Gln383X];[Gln383X] | 9;9 | premature truncation aa 383 | homo |

| 6 | c.[1094A>C];[1094A>C] | p.[His365Pro];[His365Pro] | 8;9 | mitochondrial matrix | homo |

| 7 | c.[2032G>A];[2585G>A] | p.[Gly678Arg];[Gly862Asp] | 14;17 | transmembrane;transmembrane | compound het |

| 8 | c.[1A>G];[1A>G] | p.[Met1?];[Met1?] | 2;2 | initiating Met>Val | homo |

| 9 | c.[1107-1110delTCAC];[3027T>G] | p.[His370X];[Asn1009Lys] | 9;19 | premature truncation aa 370;nucleotide binding | compound |

| 10 | c.[1355delA];[1355delA] | p.[Gln452ArgfsX44];[Gln452ArgfsX44 | 10;10 | fs & premature truncation aa 496 | homo |

| 11 | c.[578G>A];[578G>A] | p.[Ser193Asn];[Ser193Asn] | 4;4 | mitochondrial matrix | homo |

| 12 | c.[63delG];[1864-1G>T] | p.[Ser22ProfsX6];[Ile622AspfsX1*] | 2;14 | fs & premature truncations aa 28 & 623 | compound het |

| 13 | c.[1069A>G];[2637delA] | p.[Thr357Ala];[Met880X] | 7;18 | mitochondrial matrix;premature truncation aa 880 | compound het |

| 14 | c.[3022G>C];[3022G>C] | p.[Ala1008Pro];[Ala1008Pro] | 21;21 | nucleotide binding | homo |

| 15 | c.[1990G>A];[2293+1G>A] | p.[Gly664Arg];[Thr689LeufsX320*] | 14;15 | transmembrane;fs & premature truncation aa 984 | compound het |

kindreds 1,2 and 3 had linkage to 5p13-q12

the proband from kindred 1 was subjected to targeted exome sequencing

predicted result if exon skipped, fs=frameshift, aa=amino acid, homo=homozygous mutation, compound het=compound heterozygous mutations.

Mutation of the initiating methionine is of unknown consequence as the next methionine is at residue 132, and initiation of translation from this codon would result in a protein lacking the whole mitochondrial targeting presequence. Many of the described mutations are nonsense/frameshift and will lead to premature truncation of the protein. The remaining missense mutations, with the exception of the H365P substitution, are predicted to cause disruption to vital, highly conserved eukaryotic protein domains.

NNT, a highly conserved gene, encodes an integral protein of the inner mitochondrial membrane. Under most physiological conditions, this enzyme uses energy from the mitochondrial proton gradient to produce high concentrations of NADPH. Detoxification in mitochondria of reactive oxygen species (ROS) by glutathione peroxidases depends on this NADPH for regeneration of reduced glutathione (GSH) from oxidized glutathione (GSSG) to maintain a high GSH/GSSG ratio (Supplementary Figure 3). Arkblad et al. showed that C. elegans lacking nnt-1 either through mutation or RNAi knockdown are more susceptible to oxidative stress (OS) because of a lowered GSH/GSSG ratio [4]. Certain sub-strains of C57BL/6J mice contain a spontaneous Nnt mutation (an in-frame 5 exon deletion), and have been reported to display glucose intolerance and reduced insulin secretion [5,6]. Knockdown of NNT in human PC12 phaeochromocytoma cells results in decreased cellular NADPH, decreased GSH/GSSG ratios, increased H2O2 levels and hence impaired redox homeostasis [7].

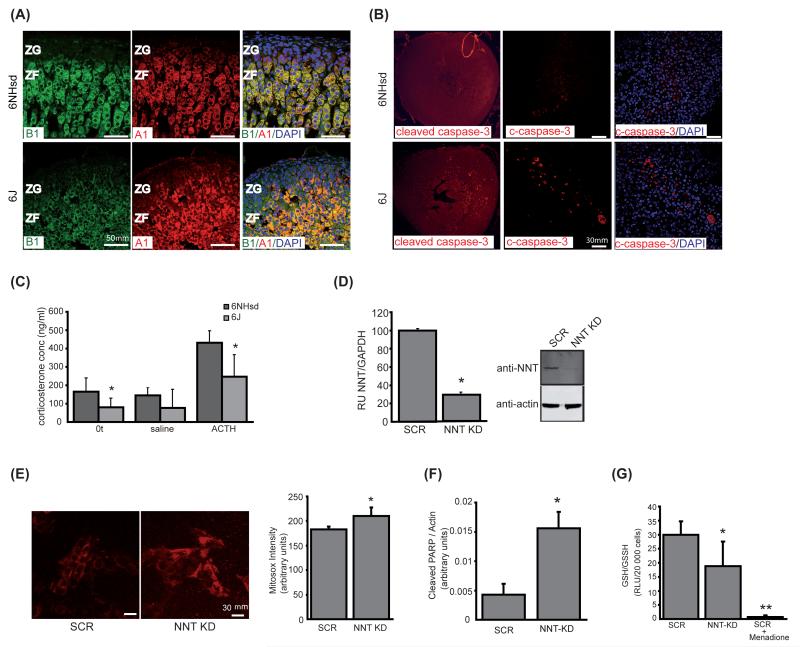

Adrenals from 3 month C57BL6/J mice carrying the Nnt mutation had slightly disorganized zonae fasciculata with higher levels of apoptosis than wild-type, C57BL6/NHsd, mice (Figures 1A & B). There were no observable differences between levels of the steroidogenic enzymes CYP11A1 and CYP11B1 between the two substrains however the mutant mice did have lower basal and stimulated levels of corticosterone than their wild-type counterparts (Figure 1A & C). Knockdown of NNT in the human adrenocortical H295R cell line by shRNA not only increased levels of mitochondrial ROS and apoptosis but also lowered the GSH/GSSG ratio (29.95±4.77 vs 18.82±8.75 in scrambled vs knockdown cells; p<0.001) implying these cells also have an impaired redox potential (Figure 1D-G and supplementary Figure 4). We found NNT to be widely expressed and most readily detectable in human adrenal, heart, kidney, thyroid and adipose tissue (Supplementary Figure 5) similar to murine expression profiles [8-10].

Figure 1.

Knockout or knockdown of NNT increases levels of mitochondrial ROS and apoptosis. A Adrenal zonation and steroidogenesis in 6NHsd and 6J mice. Wt and Nnt mutant mice showed similar patterns of CYP11A1 (red) and -B1 (green) staining, indicating no significant differences in zonation or steroidogenic capacity. The ZF cells in 6J mice however are slightly hyperplastic and disorganised being more densely packed and lacking the linear architecture seen in wt ZF. 40× magnification. B Increased apoptosis in 6J mice. Adrenals from 6J showed a higher number of caspase 3 positive cells (red) in zona fasciculata than 6NHsd. C Corticosterone levels in 6NHsd and 6J mouse serum stimulated with ACTH. Radioimmunoassay results revealed both basal and stimulated corticosterone levels were lower in 6J (p< 0.05). D Stable NNT knockdown (NNT-KD) in H295R cells. RT-PCR (i) and western blot analysis (ii) confirmed knockdown of NNT mRNA (71%) and protein (78%) levels in KD compared to SCR. E Detection of superoxide production by Mitosox. Quantitative analysis showed a significant increase (p<0.005) in superoxide production in NNT-KD relative to SCR cells. F Densitometric analysis showed a significant (p<0.001) increase in cleaved PARP between SCR and NNT-KD cells. Values are intensities of cleaved PARP relative to actin, n=12. G The GSH/GSSG ratio was lower in NNT-KD vs SCR cells (p<0.001). OS induced by the addition of 40μM menadione to the SCR cells reduced the ratio to 0.69±0.67.

These findings suggest that the impairment of adrenal steroidogenesis and development of FGD is due to defective OS responses. OS has been implicated in the pathogenesis of many disease conditions. Of particular relevance to our patients is Triple A syndrome (OMIM 231550) [11]. In this condition mutations in AAAS lead to deficiency or mislocalization of the nuclear-pore protein ALADIN resulting in impairment of the nuclear import of DNA repair and antioxidant proteins [12,13] thereby rendering the patients cells more susceptible to OS. AAAS-/- mice however show no such phenotype [14]. Nnt loss in mice has been reported to lead to impaired insulin secretion and glucose-intolerance because of OS in pancreatic beta cells [5]. Although no adrenal phenotype has previously been documented in these mice, our studies hint at a mild deficit in adrenal steroidogenesis. In conclusion our results suggest that, at least in humans, NNT is of primary importance for ROS detoxification in adrenocortical cells, highlighting the susceptibility of the adrenal cortex to this type of pathological damage. Over time patients may develop other organ pathologies related to impaired anti-oxidant defence and will therefore need careful monitoring.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Janine Altmüller for running the sample on GAIIx, Gudrun Nürnberg for doing the linkage analysis, the NHLBI GO Exome Sequencing Project and its ongoing studies which produced and provided exome variant calls for comparison: the Lung GO Sequencing Project (HL-102923), the WHI Sequencing Project (HL-102924), the Broad GO Sequencing Project (HL-102925), the Seattle GO Sequencing Project (HL-102926) and the Heart GO Sequencing Project (HL-103010).

This work has been supported by the Medical Research Council UK (New Investigator Research Grant G0801265 to LAM, Clinical Research Training Fellowship Grant G0901980 to CRH and project grant G0700767 to PK).

Footnotes

Disclosure statement: The authors have nothing to disclose.

URLs

1000 Genomes, http://www.1000genomes.org/

Exome Variant Server, NHLBI Exome Sequencing Project (ESP), Seattle, WA (URL: http://evs.gs.washington.edu/EVS/) [January 2012 accessed].

References

- 1.Clark AJ, et al. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2009;23:159–65. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2008.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Metherell LA, et al. Nat Genet. 2005;37:166–70. doi: 10.1038/ng1501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Metherell LA, et al. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2009;94:3865–71. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-0467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arkblad EL, et al. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2005;38:1518–25. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Toye A.a., et al. Diabetologia. 2005;48:675–686. doi: 10.1007/s00125-005-1680-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Freeman H, et al. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2006;34:806–10. doi: 10.1042/BST0340806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fei Y, et al. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1817:410–9. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dezso Z, et al. BMC Biol. 2008;12:6–49. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-6-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Su AI, et al. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:4465–70. doi: 10.1073/pnas.012025199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Walker JR, et al. Genome Res. 2004;14:742–9. doi: 10.1101/gr.2161804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cooray SN, et al. Endocr Dev. 2008;13:99–116. doi: 10.1159/000134828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hirano M, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:2298–303. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505598103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Storr HL, et al. Mol. Endocrinol. 2009;23:2086–94. doi: 10.1210/me.2009-0056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huebner A, et al. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:1879–87. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.5.1879-1887.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.