Abstract

Otoacoustic emissions are an indicator of a normally functioning cochlea and as such are a useful tool for non-invasive diagnosis as well as for understanding cochlear function. While these emitted waves are hypothesized to arise from active processes and exit through the cochlear fluids, neither the precise mechanism by which these emissions are generated nor the transmission pathway is completely known. With regard to the acoustic pathway, two competing hypotheses exist to explain the dominant mode of emission. One hypothesis, the backward-traveling wave hypothesis, posits that the emitted wave propagates as a coupled fluid-structure wave while the alternate hypothesis implicates a fast, compressional wave in the fluid as the main mechanism of energy transfer. In this paper, we study the acoustic pathway for transmission of energy from the inside of the cochlea to the outside through a physiologically-based theoretical model. Using a well-defined, compact source of internal excitation, we predict that the emission is dominated by a backward traveling fluid-structure wave. However, in an active model of the cochlea, a forward traveling wave basal to the location of the force is possible in a limited region around the best place. Finally, the model does predict the dominance of compressional waves under a different excitation, such as an apical excitation.

INTRODUCTION

Decades of theoretical and experimental studies (e.g., Refs. 1, 2, 3, 4) have shown that external acoustic stimuli give rise to two types of intracochlear pressure waves, the compression wave (fluid-borne) and the so-called traveling wave (a coupled fluid-structure wave). The compression wave, or fast wave, travels at the speed of sound, propagating the length of the cochlea in tens of microseconds. The traveling wave couples the fluid to the basilar membrane (BM). This wave is also called the slow wave because of its low group velocity near the location of the peak response (the best place) for pure tone stimulation. Its group velocity is usually several hundred times slower than that of the compressional wave. Presently, there is a debate as to which type of pressure wave dominates otoacoustic emissions (OAEs) from the cochlea.5 OAEs (e.g., Refs. 6, 7, 8) are generated by an excitation within the cochlea and emitted toward the outer ear canal.9 As a physiological phenomenon, the distortion product otoacoustic emission (DPOAE) is associated with healthy ears and has clinical applications for noninvasive diagnosis of hearing pathologies.10 In order to use the DPOAE as an effective tool for understanding maladies and the mechanics of the cochlea, the dominant intracochlear wave type11, 12 and the direction of wave propagation along the BM (Ref. 13) of the emission must be characterized. In this paper, we use a theoretical model of the cochlea to study how an intracochlear force acting on the BM generates an emitted disturbance at the stapes as a means to understand the acoustic pathways for emissions from the cochlea.

Experiments have been performed to determine the dominant wave type of the DPOAE,11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17 but no agreement has been reached.5 Two contradictory hypotheses exist to explain the distortion product (DP) emission pattern: (1) the slow (traveling)11, 15, 16, 17, 18 and (2) the fast (compression)12, 13, 14, 17 wave hypotheses. The slow-wave hypothesis states that the emission is dominated by the slow traveling wave, which travels along the BM in the backward direction, as opposed to the forward wave generated by acoustic stimuli. This hypothesis is supported by measurements of emission delays,11, 16 intracochlear pressure patterns,11, 15 and fine structures in the emission spectrum.11, 18 The fast-wave hypothesis posits that the emission is dominated by the fast compressive wave, which rapidly propagates to the stapes after DPs are generated. This hypothesis has also been supported by multiple experiments, including the study of the BM response patterns13, 14 and DP round-trip calculations.12 These different experimental results and the lack of agreement reveal that the DPOAE mechanism is not completely understood. In order to analyze an experiment, assumptions regarding the DP nonlinear generation mechanism(s) and the emission process are inevitable. Of the DP generation process, the distortion product is generally hypothesized to arise from the interaction of two primary tones in a region near the best place of the higher tone.12 However, other spatial regions may also contribute to the DP emission, and the spatial extent of the nonlinearity is unknown. Of the emission process, multiple reflection sources, such as the wave-fixed component, the place-fixed component,11 or distributed roughness of structures,19 are hypothesized to affect the emission. While the generation and emission processes are difficult to experimentally separate, mathematical models can analyze them individually.

There is a long history of mathematical modeling of waves in the cochlea generated by external acoustic stimuli (e.g., Ref. 20), but the intracochlear wave pattern generated by internal force excitation has not been extensively studied. In a study closely aligned to the present paper, de Boer et al.21 used a “classical” three-dimensional model21 to predict the BM response to a localized input and to an approximation of the spatial extent of the forcing from harmonic distortions. The classical model found backward traveling waves dominate the emission. Sisto et al.22 used a one-dimensional (1D) model of the cochlear fluid coupled to a nonlinear model of the BM to study distortion product emissions. They found a negative phase slope under some choices of stapes reflectivity and of the parameters of their active model. However, these models are one duct fluid models, which do not admit all modes of fast wave propagation. Matthews and Molnar23 built a two-dimensional nonlinear BM damping model for the cochlea that coupled to the middle and external ears, and predicted the emission of a distortion component. Vetesnik et al.24 used a two-dimensional model of the cochlear fluids along with a nonlinear model of the outer hair cells (OHCs) to predict the generation of nonlinearities and their propagation from the cochlea. Each model represents the nonlinearity using differing degrees of complexity and physiological realism. In the present study, we seek to answer a somewhat simpler question, namely “how does sound leave the cochlea if the BM is excited by an internal force or pressure source?.” In this way, we avoid the complexity (and uncertainty) of the generation of the nonlinearity, allowing a greater focus on the structural acoustics of the wave propagation.

This work uses a physiologically-based cochlear model. This linear finite element model couples mechanical, electronic, and acoustical elements25 to capture the physiological and physical characteristics of the cochlea. Fluid compressibility is included in the present model. Embedded in the model is the ability to switch activity on or off, enabling the model to represent both healthy and unhealthy cochleae, corresponding to in vivo and in vitro experimental preparations, respectively. Previous results25, 26 show that the model’s predicted BM responses to acoustic stimuli match experimental measurements quite well. This model allows for both forward and backward directions of wave propagation and, since the model has two acoustic ducts, symmetric and antisymmetric waves are likewise admitted. Internal forces are prescribed on the BM at a selected longitudinal location. Because the forcing location is completely prescribed, the model can be used to unambiguously predict delays from the excitation region to the stapes or anywhere else in the cochlea. Hence, this model is not associated with any assumption regarding DP generation locations or wave propagation patterns; it focuses on the fundamental responses of the cochlea under a given internal disturbance.

MODEL DESCRIPTION

The present mathematical cochlear model is based on a mechano-electro-acoustical three-dimensional finite element model25 and includes a tectorial membrane (TM) model with longitudinal viscoelastic coupling.26 The following items summarize the model.

-

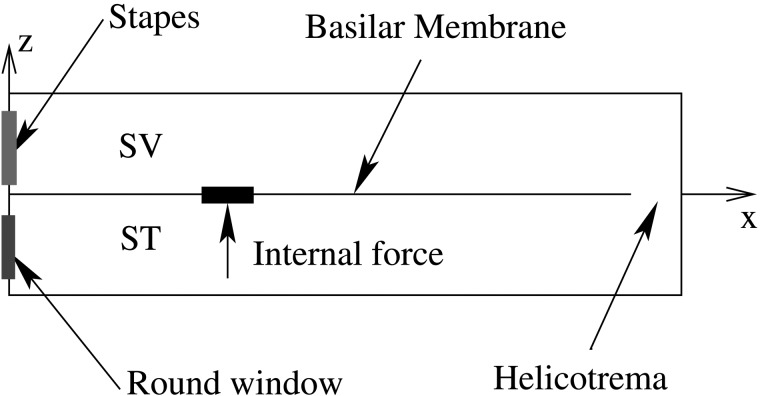

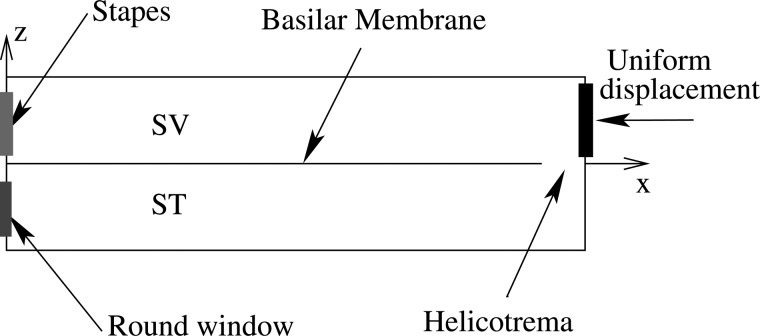

(1)The cochlea is modeled by an unwrapped rectangular box with two equivalent-size ducts that represent the scala vestibuli (SV) and the scala tympani (ST) (Fig. 1). The two ducts, connected at the apex via the helicotrema, are separated by the organ of Corti (OoC) and filled with compressible fluid. To add compressibility, the governing equation for the fluid pressure is the Helmholtz equation

where k = ω/c is the wave number, in which ω is the angular frequency and c is the speed of sound in the fluid. x, y, and z are coordinates in the longitudinal, radical, and vertical directions, respectively. Equation 1 replaces the Laplace equation for the pressure as used in Ref. 25. As in Ref. 25, the model uses cross-section fluid modes in the radial direction (y) to reduce the three-dimensional problem to a series of two-dimensional problems(1)

where M is the total number of even fluid cross- section modes (in this paper, M = 3) when , in which w is the width of the duct. The intracochlear fluid couples to the BM through the linearized Euler relation. The model incorporates fluid viscosity into the damping of the TM and BM.(2) -

(2)

Acoustic stimuli are modeled as a unit force excitation on the stapes, which couples to all the SV fluid nodes at . This stimulation method differs from earlier work25 which applied a unit displacement on the stapes. Both the stapes and the round window are modeled as single mode structures interacting with the fluid. For the stiffness of the round window, we use 1.8 × 103 N/m3 (4 orders less than the value in Wit et al.27), which is essentially a pressure release condition. The stiffness of the stapes is comparable with the value in Ref. 28 with only 1 order of difference.

-

(3)

The cochlear model includes a micromechanical system that contains the BM, TM, reticular lamina (RL), OHCs, and OHC stereocilia. The BM is modeled as a locally reacting structure with one cross-section mode. The longitudinally coupled TM has two degrees of freedom (one shear and one bending) in each cross section. The OHCs with somatic motility are modeled as linearized piezoelectric materials that relate strain and transmembrane voltage to stress and current. The conductance of the OHC stereocilia changes linearly with the rotation of the stereocilia relative to the RL [see Eq. (10) in Ref. 26].

-

(4)

Although the fluid model does not differentiate between the scala media (SM) and the SV, the electrical model that does include three coupled cables is built in both cross-sectional (in the SV, the SM, and the ST) and longitudinal levels. These electrical fields also couple to the electromechanics of the OoC via OHCs and OHC stereocilia.25

-

(5)

The cochlear activity in the model is determined as follows. The mechano-electrical transducer (MET) sensitivity, a main factor dictating the cochlear amplification and stability, is the slope of the change of the conductance with respect to the stereocilia’s rotation. Excessively high sensitivity causes an unstable cochlear response, while excessively low sensitivity leads to insufficient cochlear amplification. In this model, as discussed in Meaud and Grosh,29 the MET sensitivity is a parameter which is adjusted according to the model predictions’ match to experimental data. When the most suitable value (based on experimental data) of the MET sensitivity is determined, the cochlea is labeled as “fully active,” corresponding to a healthy cochlea or responses to low level sounds. If the MET sensitivity is zero, the cochlea is passive, corresponding to an ear in a dead animal or responses to high level sounds.

Figure 1.

(Color online) Schematic of the cochlear rectangular box model and an internal force excitation on the BM.

In this paper, a known intracochlear force is used to excite the BM (Fig. 1). In this way, the origin of the energy is completely prescribed. This prescription contrasts the DPOAE experiments, in which the origin of the DP is uncertain. The forcing location is chosen at a central location along the cochlea in order to ease visualization. Unless otherwise specified, the center of the internal force locates on the BM at 6.5 mm from the base (x = 6.5 mm), where the best frequency is about 10 kHz. The uniform amplitude force has a 300 μm spatial span. Results (not illustrated) show that for such a small spatial span of the internal force, no notable difference of the normalized BM spatial responses (away from the forcing location) exists among uniform force, bell-shaped force, and even single point force excitations.

This study’s finite element mesh size is the same as that in earlier work:25 25 μm per element in the longitudinal direction (x) and 50 μm per element in the vertical direction (z). Parameters in the model come from available guinea-pig data. Most of the parameters used in this work can be found in Ramamoorthy et al.25 and Meaud and Grosh.26 Table TABLE I. gives the parameters either adjusted from or not included in the earlier work.25, 26 The steady-state cochlear response of a fixed frequency is obtained from each single-frequency simulation. In order to compute impulse responses, frequencies are swept from 200 Hz to 500 kHz or 800 kHz (depending on the temporal resolution required) with 200 Hz increments, and then the inverse Fourier transform is applied to these frequency domain data to obtain time domain results.

TABLE I.

Material properties for the cochlear model (x is in meters).

| Property | Value | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Speed of sound in the fluid | 1500 m/s | From water |

| BM width (b) | 80 μm (base) to | Based on Ref. 30 |

| 180 μm (apex) | ||

| BM thickness (h) | 7 μm (base) to | Based on Ref. 30 |

| 1.7 μm (apex) | ||

| 13 μm | Ref. 31 | |

| 40 μm | Ref. 31 | |

| Duct length (L) | 1.85 cm | Ref. 30 |

| Helicotrema length | 0.1 cm | Assumed |

| Stapes stiffness | 1.8 × 107 N/m3 | Assumed |

| Stapes damping | 5.8 × 102 N · s/m3 | Assumed |

| Round window stiffness | 1.8 × 103 N/m3 | Assumed |

| Round window damping | 5.8 × 102 N · s/m3 | Assumed |

| BM stiffness per | 4.498 × 109 (h/h0)3(b0/b)4 N/m3 | Based on Ref. 32 |

| unit area () | ||

| TM bending stiffness () | 1.233 × 104 e(−400x) N/m2 | Based on Ref. 33 |

| TM shear stiffness () | 1.233 × 104 e(−400x) N/m2 | Assumed |

| RL stiffness () | 4.008 × 103 e(−420x) N/m2 | Based on Ref. 34 |

| HB stiffness () | 1.879 × 104 e(−420x) N/m2 | Estimated from Ref. 35 |

| OHC stiffness () | 4.008 × 103 e(−420x) N/m2 | Based on Ref. 36 |

| BM viscous damping per | (0.1/b) N·s/m3 | Assumed |

| unit area () | ||

| TM bending damping per | 0.05 N·s/m2 | Assumed |

| unit length () | ||

| TM shear damping per | 0.03 N·s/m2 | Assumed |

| unit length () | ||

| Effective TM | kg/m | From Ref. 25 |

| Shear mass | kg/m3, , | |

| ψ (angle of forward | 0 | Assumed |

| inclination of the OHC) | ||

| (feed-forward distance) | 0 | Assumed |

| () N/m/mV | Based on Ref. 37 | |

| 4.0018 S/rad/m for full activity | Free parameter | |

| α (spatial decay rate | 150 m−1 | Based on Ref. 38 |

| of the maximum conductance) | ||

| 150 MΩ/m | Based on in Ref. 39 |

RESULTS

This section presents the results from numerical simulations of the cochlear model. Cochlear responses under the internal force excitation are compared to those under external acoustic stimuli because the latter is well established. Responses in temporal and spatial domains are emphasized because they can either identify wave arrival times or help to visualize the direction of wave propagation and the BM amplification. As an alternative method to determine the direction of wave propagation, the relative BM responses at two longitudinal locations in the frequency domain are calculated because these quantities can be measured under very similar experimental conditions.13 In addition, the temporal stapes displacement under an excitation from the apex will be presented to study the fast wave generation in the model.

Impulse responses

The impulse responses of the stapes due to internal force excitation on the BM are compared to the impulse responses of the BM due to acoustic stimuli at the stapes. The onset motion of the stapes or the BM determines wave arrival times.

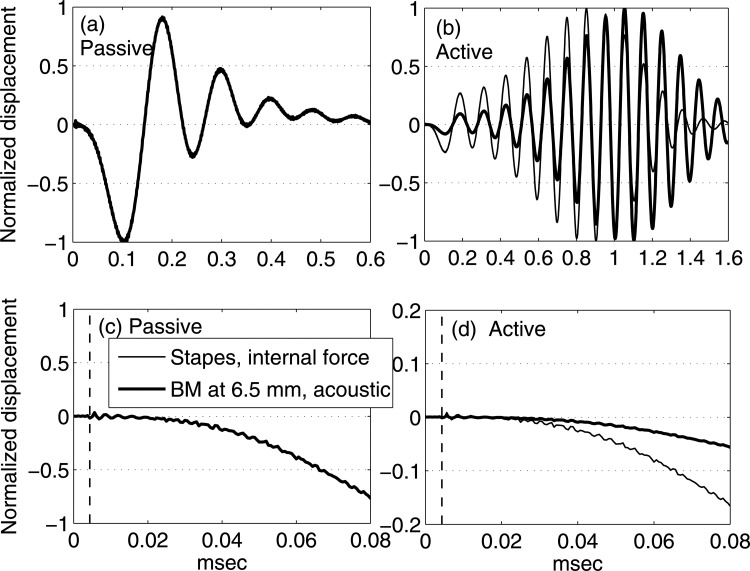

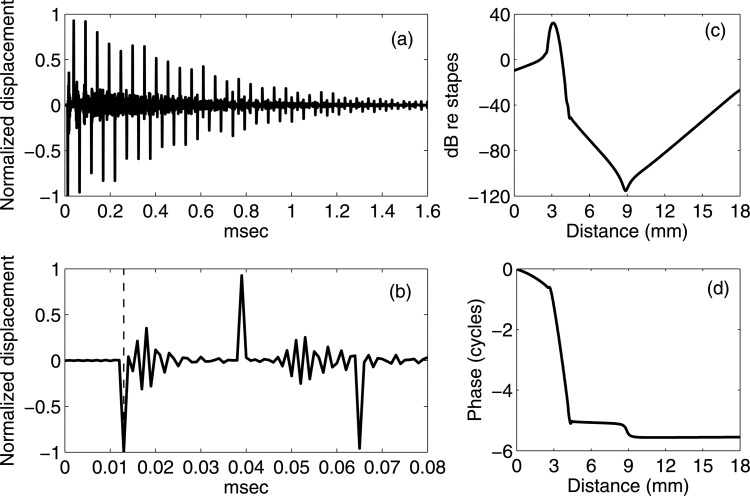

Figure 2 compares the impulse responses of the BM at 6.5 mm under the acoustic input (thick solid lines) and the impulse responses of the stapes under the internal force on the BM at 6.5 mm (thin solid lines). Each response is normalized to its own maximum value. In Figs. 2a, 2c, the BM and the stapes responses overlap, and only the BM response (thick curves) is visible. Passive responses decay after ∼0.6 msec [Fig. 2a] while active responses last for ∼1.6 msec [Fig. 2b]. Hence, the impulse responses of both the stapes (under internal excitations) and the BM (under acoustic stimuli) damp quickly in the passive cochlea and persist longer in the active cochlea. One substantive result is that the two normalized passive responses in Fig. 2a are exactly the same, and this is a consequence of structural acoustic reciprocity for a passive system (see the Appendix and Ref. 40). In the active cochlea [Fig. 2b] the two wave forms do not overlap, but the arrival times of their first few peaks, valleys, and zeros are aligned. At the time scale used for Figs. 2a, 2b, the wave form appears smooth.

Figure 2.

Impulse responses of the BM at 6.5 mm from the base under acoustic stimuli (thick solid lines) and the impulse responses of the stapes under internal force excitation (thin solid lines). Temporal resolution: 0.625 μs. Each response is normalized to its own maximum value (normalization factors: passive acoustic, 4.887 × 10−4 μm; passive internal force, 6.332 × 10−3 μm; active acoustic, 6.455 × 10−3 μm; active internal force, 2.833 × 10−3 μm). (a) Long time scale responses of the passive model. (b) Long time scale responses of the fully active model. (c) Early temporal responses of the passive model. (d) Early temporal responses of the fully active model. The thin vertical dashed lines in (c) and (d) indicate the time for sound in water to travel from the stapes to the BM at 6.5 mm, or from the BM at 6.5 mm to the stapes. The result predicts the identical normalized passive responses under two excitation methods, and same traveling-wave arrival time for active response.

As a way of determining the existence of the fast wave, the impulse response arrival times are compared to the compression wave traveling time. For the speed of sound in water, it takes about 4.3 μs for sound to travel from the stapes to the BM at 6.5 mm (or equivalently from the BM at 6.5 mm to the stapes). Figures 2c, 2d indicates this time scale with vertical dashed thin lines. Both the passive and active cases show that the stapes and the BM at 6.5 mm show small oscillations when the compression wave arrives. As can be seen in the finer time scale, the small perturbation due to the compression wave superimposes on the otherwise smooth wave form that represents the traveling-wave response. The amplitude of the perturbation is very small compared to the amplitude of the traveling-wave response.

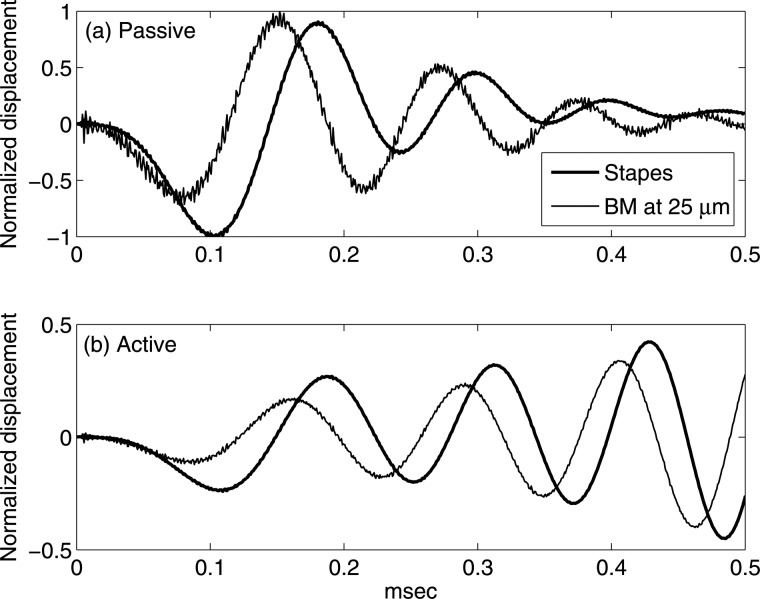

In order to analyze the cochlear basal responses as the disturbance travels on the BM, Fig. 3 compares normalized impulse responses of the stapes (thick solid lines) and the BM at 25 μm away from the stapes (thin solid lines) under internal force excitation. In Fig. 3a, similar to Fig. 2, the fast wave disturbance is a perturbation on the wave form of the traveling wave. The responses from the BM and the stapes show a similar trend, but the arrival time of the first peak of the BM at 25 μm is earlier than that of the stapes. The temporal gap between the two initial peaks of the wave forms represents the time needed for the emitted slow wave to travel from the BM at 25 μm to the stapes, which is much longer than the compression wave requires. The phenomenon is also evident in an active cochlea that the first peak/valley of the wave form of the BM at 25 μm leads the stapes [Fig. 3b].

Figure 3.

Difference between the stapes and BM responses at 25 μm under internal force excitation. Thick solid lines: responses of the stapes. Thin solid lines: responses of the BM at 25 μm away from the stapes. Temporal resolution: 0.625 μs. Each displacement is normalized to its own maximum value (normalization factors: passive stapes, 6.332 × 10−3 μm; passive BM at 25 μm, 1.661 μm; active stapes, 2.833 × 10−2 μm; active BM at 25 μm, 12.02 μm). (a) Prediction from the passive model. (b) Prediction from the fully active model. In both cases, the BM wave form leads the stapes response, indicating that the traveling wave propagates toward the base.

Spatial response

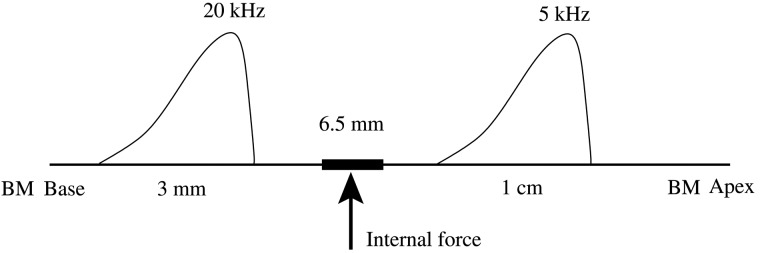

This section presents steady-state spatial responses of the BM under internal force excitation at 6.5 mm. In the spatial (longitudinal) domain, the direction of wave propagation can be visualized from the spatial dependence of phases. Two frequencies, 5 and 20 kHz, are simulated for two reasons. First, the distances between their corresponding best places (∼10 and 3 mm, respectively) and the forcing place (6.5 mm) are sufficient such that there is no interaction between the forcing and the active response near the best place. Second, the response patterns for these two frequencies are representative of the generic cases when the best place is basal (20 kHz) and apical (5 kHz) of the excitation location (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Schematic of the spatial mappings of 5 and 20 kHz along with an idealization of the BM responses. The unit internal forcing is applied on the BM at 6.5 mm from the base. The best place for 5 kHz is ∼10 mm, apical to the forcing location. The best place for 20 kHz is ∼3 mm, basal to the forcing location.

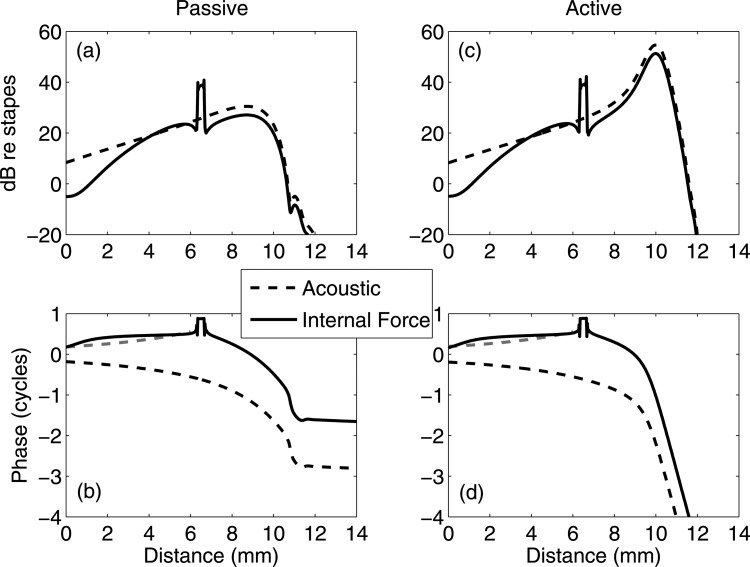

Figure 5 shows the BM responses referenced to the stapes under 5 kHz internal force excitation (solid lines). For comparison, the dashed lines show the same frequency acoustic responses, and the short dashed lines indicate mirror reflections of the phases (0–6 mm) under acoustic stimuli. In the passive cochlea [Figs. 5a, 5b], basal to the forcing place, the BM amplitude decreases as it approaches the stapes. The phase slope and value under the internal force excitation have opposite signs to those under the acoustic stimulation, but do not overlap upon mirror reflection. Apical to the forcing place, the BM amplitude peaks at the best place, just as with the acoustically induced response. The phase from the internal force excitation replicates the phase from the acoustic stimulation except that there is a one cycle offset. In the active cochlea [Figs. 5c, 5d], basal to the forcing place, both the BM amplitude and the phase are identical to the passive cochlea [the responses in Figs. 5c, 5d will overlap with those in Figs. 5a, 5b if plotted together because of the small influence of activity in this region]. Apical to the forcing place, the BM magnitude is amplified at the best place as is acoustic response, which is very similar to the passive cochlea. The active phase under the internal force excitation has more forward-traveling-wave phase accumulation compared to the passive phase, and is parallel to the phase under acoustic stimulation, with a one cycle offset as in the passive case.

Figure 5.

(Color online) BM responses at 5 kHz under acoustic and internal force inputs. The best place is around 10 mm. Both amplitudes and phases are normalized with respect to the stapes. Solid lines: responses under the BM excitation at 6.5 mm from the base. Dashed lines: Responses under acoustic stimuli. For reference, mirror reflection of the phase under acoustic stimuli for locations basal to the force (<6 mm) is shown with short dashed lines. (a) and (b) Predictions from a passive model. (c) and (d) Predictions from an active model. (a) and (c) BM amplitudes referenced to the stapes. (b) and (d) BM phases in cycles. A backward-traveling wave is predicted from the response under the internal BM excitation, while a forward-traveling wave dominates the response to acoustic stimulation.

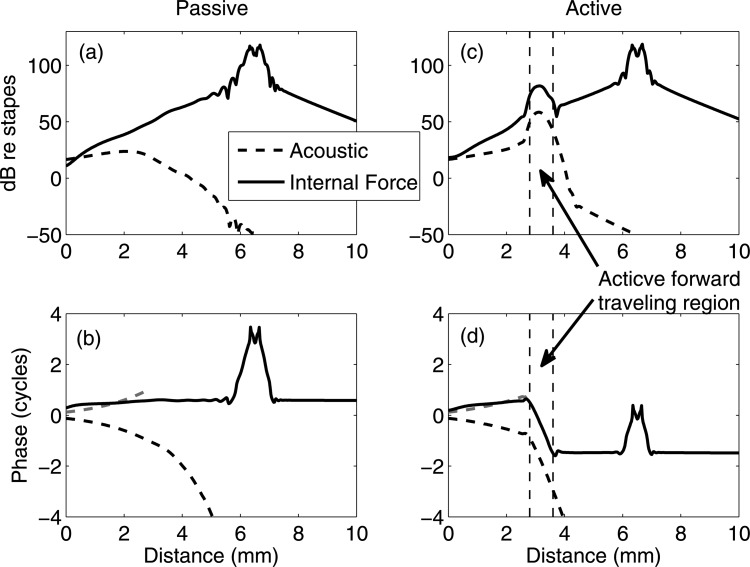

The results predicted in Fig. 6 come from the same simulation parameters in Fig. 5 except that the excitation frequency is changed to 20 kHz. Since the response apical to the excitation region is evanescent, only locations basal to the 10 mm place are plotted. In the passive cochlea [Figs. 6a, 6b], there is a monotonic decrease in the BM amplitude as the BM spatially approaches the stapes. The BM phase shows a small backward-wave slope, and is, however, almost flat. Hence, the response is dominated by the evanescent decay from the excitation region and is very different in amplitude and phase from the acoustic response (shown in dashed lines). In the active cochlea [Figs. 6c, 6d], the best place becomes visible within a restricted region (from 2.8–3.6 mm as enclosed by two vertical dashed lines), with the BM magnitude amplified and the phase accumulated as a forward traveling wave. Basal to the best place region, like Fig. 5, the phase and the slope of the phase elicited by internal force excitation have opposite signs to those under acoustic stimulation. Apical to the best place region, the phase is a constant and thus does not continue to accumulate. Hence, under the internal force excitation the forward wave pattern is limited to the best place region, and thus is a local phenomenon as opposed to the global forward wave under the acoustic stimulation. Since this best place region only appears in the active cochlea, hereafter it is defined as the “active forward-traveling-wave region.”

Figure 6.

(Color online) BM responses at 20 kHz under acoustic and internal force inputs. The best place is around 3 mm. Both amplitudes and phases are normalized with respect to the stapes. Solid lines: responses under the BM excitation at 6.5 mm from the base. Dashed lines: response under acoustic stimuli. For reference, mirror reflection of the phase under acoustic stimuli for locations basal to the best place (<2.8 mm) is shown with short dashed lines. (a) and (b) Predictions from a passive model. (c) and (d) Predictions from an active model. (a) and (c) BM amplitudes referenced to the stapes. (b) and (d) BM phases in cycles. A backward-traveling wave, along with an active forward-traveling region (enclosed by two vertical dashed lines), is predicted from the response under the internal BM excitation.

Variation of stimulus frequencies

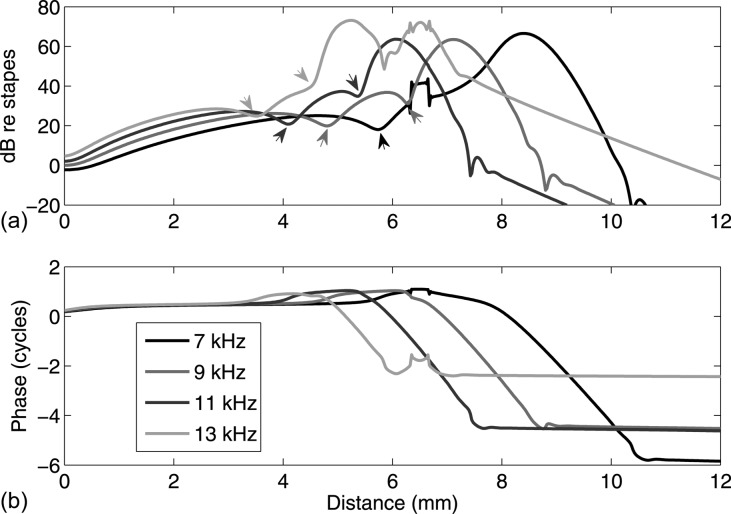

In Figs. 56, since the best places of stimulus frequencies are far away from 6.5 mm, no strong interaction is observed between the force and the BM amplification near the best place. However, interaction between the BM tuning and the internal force may occur when these two locations are overlapping or close. Figure 7 shows the active BM spatial responses referenced to the stapes under internal force excitation at 6.5 mm with different stimulus frequencies that are close to 10 kHz, the best frequency at 6.5 mm. In the amplitude panel, irregularities such as multiple peaks and notches appear basal and close to the forcing place. Notches beyond the best place, where the amplitude of the BM vibration decays quickly, are a manifestation of the interaction of the first wavenumber locus (corresponding to the traveling wave) as it cuts off with the second root locus as it cuts in.41, 42 Localized evanescent fields can be seen around the forcing location, especially for the 13 kHz case. Notches designated by arrows in Fig. 7a indicate the interaction between forward and backward waves basal to the forcing location. In the phase panel, at the very base, waves of all frequencies propagate backwards in a similar manner; at the best place of each excitation frequency, a forward traveling wave is identified; basal and close to the forcing place, irregularities in phase happen as well. Comparison between the amplitudes and the phases shows that whenever a “notch” (coming from the interaction of waves from two directions) appears in the amplitude, a corresponding half cycle jump appears in the phase. These characteristics of irregularity in the amplitude and in the phase suggest the existence of evanescent waves and the interaction of waves from two directions.

Figure 7.

(Color online) Active BM spatial responses under unit force excitation on the BM at 6.5 mm with different stimulus frequencies. The best places of 7, 9, 11, and 13 kHz excitations are, respectively, around 8.5, 7.1, 6.0, and 5.3 mm (from our active model prediction). Both BM amplitudes (a) and phases (b) are normalized to the motion of the stapes. BM amplitude “notches” from wave interaction in two directions are denoted by arrows; these notches correspond to half-cycle phase jumps. Waves basal to the forcing place are dominated by backward-traveling waves, with the appearance of a forward-traveling region if the excitation frequency is higher than the best frequencies of the forcing place (e.g., for 11 and 13 kHz).

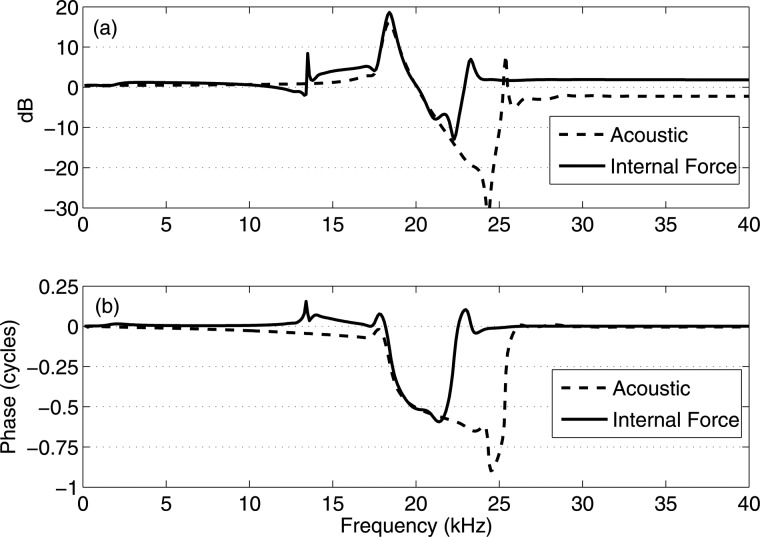

Relative response at two locations

Although temporal and steady-state spatial responses have provided much information on the emitted wave direction, it is always helpful to directly compare the steady-state motions of two nearby longitudinal locations on the BM to investigate their relative responses, as this comparison can be experimentally achieved as well.13 Figure 8 shows the relative active BM response between 3.2 and 3.0 mm (3.2 mm referenced to 3.0 mm, the best frequencies at 3.0 and 3.2 mm are 20.3 and 19.5 kHz, respectively) under the internal force excitation on the BM at 6.5 mm (solid lines). The same relative response under the acoustic stimulation is included for comparison (dashed lines). Since the relative amplitude is in a dB scale, a positive value indicates that the amplitude of the BM at 3.2 mm is higher than that at 3.0 mm; for the relative phase, a negative value indicates that the BM at 3.2 mm lags the BM at 3.0 mm and the wave propagates forward. For almost all frequencies less than 22 kHz, the relative amplitudes of the two locations due to the two excitation methods are identical (the main exception is at 13.5 kHz). Above 25 kHz, as is expected from Fig. 6c, the relative amplitude under internal force excitation is always positive. In the phase panel, below 18 kHz under internal force excitation, the wave propagates backwards from 3.2 mm to 3.0 mm as indicated by the negative relative phase, which is opposite that under acoustic stimulation. Between 18 and 22 kHz, the relative phases under two excitation methods are almost identical, showing that the locally generated active response at the best place under the internal force excitation is the same as the global forward traveling wave under the acoustic stimulation. Hence, a forward traveling wave is observed when stimulus frequencies are close to the best frequencies of 3.0 and 3.2 mm. Above 23 kHz, under the internal force excitation, the BM at 3.2 mm moves in phase with the BM at 3.0 mm, which is consistent with the flat phase apical to the “active forward-traveling wave region” in Fig. 6d.

Figure 8.

The relative active BM amplitudes (a) and phases (b) at the 3.2 mm place relative to the 3.0 mm place under a unit internal force excitation on the BM at 6.5 mm (solid lines). The same relative response under an acoustic stimulation is plotted for comparison (dashed lines). The best frequencies at 3.0 and 3.2 mm are 20.3 and 19.5 kHz (from our active model prediction), respectively. Negative phase values indicate that the wave travels forward, and conversely for positive phase.

Apex excitation

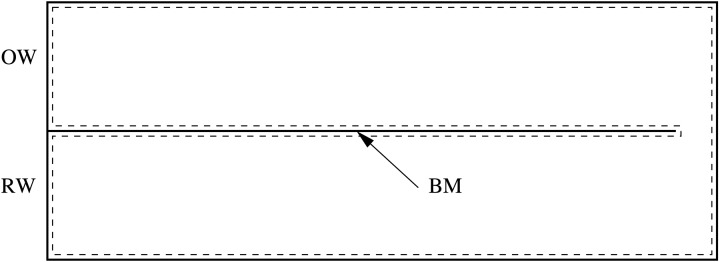

In an effort to generate non-negligible compression waves in the model, an apical displacement excitation (as shown in Fig. 9) is modeled. Here the “non-negligible” refers to a large compression wave that is able to generate a forward traveling wave from the refection at the stapes. The entire cochlear length is 19.5 mm, and sound takes 13 μs to travel from the apex to the stapes.

Figure 9.

(Color online) Schematic of the cochlear apex excitation model.

Since the cochlear model is linear, the maximum displacement of the stapes is proportional to the apex displacement input. In Fig. 10a, the time scale is chosen to show the decay of a periodic train of impulses. In Fig. 10b), a magnified view shows that the first impulse arrives at 13 μs (as indicated by the dashed line) and the successive impulses are at 26 μs intervals, the round trip time for a compressional wave.

Figure 10.

Cochlear responses under the apex input. (a) and (b) Normalized impulse responses of the stapes under the apex excitation. Temporal resolution: 1 μs. (a) Long time scale response of the active model. (b) A copy of (a) that emphasizes short time scale response of the active model. The thin vertical dashed line in (b) indicates the time (13 μs) for sound in water to travel from the cochlear apex to the stapes. (c) and (d) The active steady-state spatial response of the BM referenced to the stapes under 20 kHz apex input. The best place is around 3 mm. (c) Amplitude in dB. (d) Phase in cycles. The motion of the stapes is induced by the compression wave, and the forward-traveling wave exists in the entire cochlea.

Figures 10c, 10d show the prediction of the active steady-state spatial response of the BM referenced to the stapes under a 20 kHz apex input. Both the amplitude in Fig. 10c and the phase in Fig. 10d show a forward-traveling wave that peaks at the 3 mm best place. The BM response in Figs. 10c, 10d is different from the active internal force response in Fig. 6 where only a small region of forward-traveling wave is found at the best place. Indeed, the spatial BM response under the apex input is almost identical to that under acoustic stimuli. The high BM amplitude in Fig. 10d near the apical region is due to the input source at the apex.

DISCUSSION

Reciprocity and traveling times

The passive impulse response at the 6.5 mm location arising from stapes excitation is identical to the impulse response of the stapes due to a localized force at the 6.5 mm location, as shown in Fig. 2a. This is a manifestation of structural acoustic reciprocity40 (see the Appendix for a derivation). The impulse response represents energy from all frequencies, and the reciprocity relation holds for time-harmonic forcing as well. Puria et al.43 performed the reciprocity experiment in human cadaver cochleae in the frequency domain and found that the forward and backward group delays were nearly identical, in accordance with the structural acoustic reciprocity relation.

Unlike the passive cochlea, the response of an active cochlea does not exhibit reciprocity under the two excitations, as seen in Fig. 2b. The deflection of the OHC stereocilia contributes to the stereocilia current but not to the force, thereby breaking the symmetric coupling between the structural and electronic elements in the model.25 However, the first few peaks, valleys, and zeros of their wave-form responses are aligned, as seen in Fig. 2, which shows that it takes very nearly the same amount of time for the BM at 6.5 mm to respond to the traveling wave under acoustic stimuli and the stapes to respond under internal BM force excitation at 6.5 mm. Therefore, the linear active cochlear model bears a symmetric traveling-wave-responding time scale with respect to two excitation methods. Note that even when hair-bundle forcing is included in the model, the coupling is still not symmetric.29

The group delay from the internal force to the stapes at the ∼10 kHz best frequency of an active cochlea (100 Hz frequency resolution) is 0.895 ms [computed from a derivative of the phase of the transfer function in the frequency domain (not shown)]. This is less than the 1.12 ms forward group delay from the acoustic stimulation to the BM at 6.5 mm (figure not shown). The group delay represents the amount of time required for the peak of the energy in a frequency band to propagate in a given distance. This energy travel time is nicely shown in Fig. 2b where the peak of the stapes-induced vibration on the BM occurs at ∼1.12 ms (just as predicted by the group delay calculation). Similarly, the peak of the vibration of the stapes due to the internal force is predicted by the group delay. Similar to common usage in signal analysis,44 Siegel et al.45 also analyzed the time scale of group delays at best frequencies and referred to it as the “center of gravity” of impulse responses. If the BM at 6.5 mm is excited by a single point force instead of a 300 μm uniform force, the backward group delay increases to 1.08 ms. This increase shows that a smaller spatial span of the internal force increases the backward group delays because the spatial locations with shorter time delays are no longer encompassed by the force. The (small) 40 μs difference between the forward 1.12 ms and the backward 1.08 ms is due to the non-reciprocal relation in the active cochlea by the MET function. Nevertheless, both the predicted backward group delay under internal force excitation and the predicted forward group delay under the acoustic stimulation, which are 200–300 times slower than the 4.3 μs compression wave traveling time, are comparable with the group-delay trend lines from experiments on guinea-pigs.46 Therefore, the emitted wave under an internal force excitation is dominated by a traveling wave.

For the passive cochlea, the predicted group delay is 0.15 ms as directly read from the peak in Fig. 2. This delay is consistent with the analytical transient time given by Peterson and Bogert [from Eq. (17) in Ref. 2] for the antisymmetric (slow) wave, which predicts 0.156 ms based on the 10 kHz best frequency at 6.5 mm. The similarity of these two solutions indicates that the largest contribution to the response in Fig. 2 comes from the slow wave.

The response to internal force excitation is dominated by backward traveling waves

One of the most straightforward ways to visualize the direction of wave propagation inside the cochlea is to obtain the spatial phase accumulation along the BM, as presented in Figs. 56. The slope of the phase indicates the dominant direction of wave propagation. As can be seen in Fig. 5, when the forcing region is basal to the best place of the stimulus frequency, a forward-traveling wave occurs with the same phase slope as an acoustically excited traveling wave. Basal to the forcing location, the solution is dominated by a backward wave even for the active case, but this wave is not a purely negative going wave as the phase is not simply the reflection of the spatial phase of the acoustically excited wave [compare the short dashed lines to the solid lines in Figs. 5b, 5d]. de Boer et al.27 used a different mathematical model and obtained the same result as ours (Fig. 2 in Ref. 21). In that model, the BM impedance was locally determined by the inverse-solution method based on experimental data. An active DP generated pressure amplitude was constructed to represent the DP force origin. Their predicted “left-going wave” and the “right-going wave” are exactly the backward (basal to the forcing place) and the forward (apical to the forcing place) waves predicted in Fig. 5, respectively. This forward or right-going wave is different from the forward wave found by Ren’s group,13 who attributed the forward wave that traveled from the stapes to the DP generation place to the dominant emitted fast wave.

In Fig. 6, the best place of the stimulus frequency is basal to the forcing place. In the passive cochlea, the almost flat phase indicates an evanescent wave emanating from the force. In the active cochlea, an evanescent disturbance reached the best place from the forcing location. This disturbance gives rise to an “active forward traveling region.” In this region, electromotility locally generates a forward traveling wave. Our model predicts that basal to the best place, this locally generated wave travels back to the stapes with a spatial phase that is almost a perfect mirror replica of the acoustically-induced forward wave.

The direction of wave propagation apical to the forcing place is not controversial; the main uncertainty lies in the region basal to the forcing place. The impulse response of the stapes and at a location 25 μm away from the stapes due to a force at 6.5 mm shows that the BM wave-form response leads the stapes response (Fig. 3). This implies that a backward traveling wave propagates along the BM. Hence, the wave motion of the BM is not induced by the stapes; otherwise, the BM would respond later than the stapes. Backward wave propagation in the region basal to the active forward-traveling region can also be seen for frequencies less than 18 kHz in Fig. 8. In Fig. 8, the phase of the nearby locations is used to infer the direction of wave propagation, as used experimentally by Ren’s group.13 The irregularities in the phase and amplitudes below 18 kHz in Fig. 8 arise from the interaction of the reverse-going evanescent wave and the locally generated forward going wave [see the notch in the spatial pattern beyond the active forward traveling region designated by the dashed vertical lines in Fig. 6c as well as the notches in Fig. 7]. These waves are not really standing waves as the reverse-going “wave” is evanescent in this case (as the excitation frequency is greater than the best frequency of the excitation location).

Forward traveling waves basal to the excitation location is possible

As discussed, the model shows that under the internal BM force excitation, the dominant emitted wave is the backward traveling wave. However, this dominant backward traveling wave does not exclude the existence of a forward traveling wave in the cochlea. One main finding in this paper is that, as predicted in Fig. 6, an active forward traveling region is locally (at the best place) possible. Figure 6 is a typical representation of the case when the forcing region does not overlap with the best place of the stimulus frequency. As shown in Fig. 7, a region of forward propagation is a robust prediction for the active model when the excitation frequency is greater than the best frequency of the forcing location. We also varied the location of the forces and found the same phenomenon. For the internally excited cochlea, changing the impedance of the stapes modifies the reflectivity of the model at the boundary. But in our model, even when the impedance of the stapes is increased or reduced by 3 orders, the predicted BM phase is almost identical to Fig. 6 (result not shown). Thus, the local active generation and the backward wave basal to the best place are intrinsic phenomena in our model. In Sisto et al.’s22 model, however, the reflection of the stapes plays an important role on the direction of wave propagation because the reflexivity of the stapes directly couples to the traveling wave in the 1D model.

When does the non-negligible compression wave exist?

A non-negligible compressional wave will be generated in our model when some form of volumetric energy is injected into the cochlea. For instance, acoustically excited stapes motion generates a fast wave;21 displacement excitation at the apex (as shown in Fig. 9) gives rise to both a pronounced fast wave [see Figs. 10a, 10b] and a forward traveling wave [see Figs. 10c, 10d]. Our results show that localized forcing of the BM does not strongly couple to a compressional mode in the two cochlear channels. Indeed, forcing the BM in our model mainly couples to a pressure difference in the SV and ST (where there is a pressure jump across the boundary), generating a motion that is nearly orthogonal to the fast wave which has a constant pressure profile in the cochlear cross section. Spatial plots of intracochlear pressure show that, indeed, acoustic stimulation gives rise to symmetric pressure that is of the same order of magnitude of the traveling-wave pressure, and the symmetric pressure is negligible under internal force excitation (results not shown). We also investigated the influence of the relative impedance of the stapes and the round window on the compression wave by adjusting the two impedances. When the two impedances are the same, no compression wave exists in the cochlea under internal BM force excitation (results not shown), which further confirmed that localized forcing of the BM is not essentially associated with volumetric energy injection.

In order to explore alternative means for exciting pronounced fast waves in the cochlea, we used point acoustic sources at the 6.5 mm location. If a single pressure source is placed in the SV, this pressure input acts as a net fluid volume source that launches a compression wave in the cochlea (the compression wave was verified by calculating the temporal response of the intracochlear pressure, and a similar result to Fig. 10 is obtained), resulting in a forward-traveling wave on the BM. The direction of propagation of this wave is strongly influenced by the impedance of the stapes and the round window (result not shown), a result consistent with Sisto et al.’s22 result. However, if a dipole pressure source is present (i.e., one positive pressure node in the SV and one negative pressure node in the ST), the fluid volume change is canceled and no compression wave is generated. In the latter case, the dominant emitted wave is still the slow backward-traveling wave (result not shown).

Implications on the DPOAE

When two primary tones (f1, f2) are presented to the cochlea, DPOAEs are generated at frequencies corresponding to algebraic combinations of the two primaries, notably 2f1 − f2, 2f2 − f1 with f2 > f1. It is often hypothesized that the DP is generated near the f2 best place12 as the amplitudes of the two primaries maximally overlap in this region. In the experiments from Ren’s group reported in Ref. 13, the BM vibration at two nearby locations on the BM (separated by 196 μm) was measured at the 2f1 − f2 DP frequency in response to acoustic stimulus at the two primaries. For 2f1 − f2 frequencies below the best frequency of the most apical measurement location, we would expect a positive phase slope indicating a backward traveling wave. As indicated by the dashed lines in Figs. 2(B) and 2(D) in Ref. 13, the measured phase instead showed a negative phase slope for emissions at these frequencies, indicating the dominance of a forward traveling wave. If the DP generation site 2f1 − f2 is near the f2 best place, then the forcing location is basal to the best place for that frequency (as 2f1 − f2 < f2). This replicates the situation shown in Fig. 5, where for a localized force, backward traveling waves are predicted to dominate. The intention of this paper is not to simulate the forcing from a DP. However, if the region of forcing was extended to the base (as a uniform force), then forward traveling waves are predicted by our model. The forcing at the DP frequency arising from the nonlinear interaction of the primaries is likely more complicated (with variable phases and amplitudes). Sisto et al.22 were able to control the width of the region of the DP force generation in a nonlinear cochlear model by varying the model parameters. They found that forward propagation waves could be generated by the DP if the activity was sufficiently broad and the reflectivity of the stapes was realistic. Although the model of Sisto et al.22 is incomplete as it does not admit fast waves in the same way as a more complete two-duct model does (either an elegant post-processing step, as in Yoon et al.3 or our more straightforward approach would be needed to include this effect), it nicely points out that when activity is present, an internal force can generate forward traveling waves. Our model predicts such a situation when the best place of the stimulus frequency is apical to the force (see Fig. 5).

In this work, the calculated group delays in an active cochlear model show that the backward delay from the forcing place to the stapes is similar to that from the stapes to the forcing place under acoustic stimuli. Therefore, the predicted intracochlear round trip delay is approximately twice the forward group delay. However, Ren et al.’s12 measurement showed that the intracochlear round trip delay was even less than the forward delay at the f2 best place. The interpretation was: The DP generation place was slightly basal to the f2 best place (the hypothesized DP generation place) so that the actual forward delays was less than what was expected, and the emitted wave was the compression wave. Our model shows that without volumetric energy, no remarkable compression wave will be generated. But our model does show that if the forcing place spreads a wide range, the backward delay is reduced. Hence, Ren et al.’s round trip measurement may indicate a more complicated DP source than it is hypothesized, e.g., it may spread wide basal to the f2 best place (as consistent with what was discussed above as hypothesized by Sisto et al.22) Indeed, the notion of a more basal DP generation region has now been widely hypothesized.12, 16, 47 Alternatively, some, as yet unidentified, source of volumetric change in the cochlear structures could also give rise to a fast wave.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant No. NIH-NIDCD-04084.

APPENDIX: DERIVATION OF THE RECIPROCITY IN THE PASSIVE COCHLEA

The following derives the reciprocity of two excitation methods in the passive case. The goal is to show that the response at point B (here would be the stapes) due to an excitation at point A (here would be the BM at 6.5 mm) is the same as the response at point A if point B is excited in the same way. The physical boundary of this problem is shown in Fig. 11. The superscript “(1)” denotes any quantities that are associated with acoustic stimuli (force on the stapes), and “(2)” denotes any quantities associated with the internal force excitation on the BM.

Figure 11.

Schematic showing the boundary (denoted by dashed lines) of the intracochlear fluid.

Under acoustic stimuli, the following relations hold

| (A1) |

| (A2) |

| (A3) |

where ν is the velocity, p is the pressure, and ρ is the density of the intracochlear fluid. Each Z is a self-adjoint operator. Loosely, you can think of this as the impedance, although a lossless elastic dynamic operator will also satisfy the relationship (e.g., for displacement fields u and v). Subscripts “BM,” “ow,” and “rw” represent quantities that are associated with the BM, the oval window, and the round window, respectively. Fext is the external force from acoustic stimuli. is the pressure difference across the BM. is the mode shape of the round window.

Similarly, under the internal force excitation, the following relations hold

| (A4) |

| (A5) |

| (A6) |

where fBM is the internal force per unit area applied on the BM.

The governing equations of the intracochlear fluid under the two states are

| (A7) |

Multiply the first equation by p(2) and the second by p(1), and subtract the two to find

| (A8) |

Integrate Eq. A8 over the whole fluid domain and apply the divergence theorem to get

| (A9) |

where n is in the outward-normal direction of the fluid surface. After applying Eqs. A1, A2, A3, A4, A5, A6 along with the rigid boundary conditions at the other walls, Eq. A9 becomes

| (A10) |

If fBM(x) is a δ-function applied at x = x0, which is defined as

| (A11) |

then Eq. A10 shows the reciprocity

| (A12) |

References

- Olson E. S., “Intracochlear pressure measurements related to cochlear tuning,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 110, 349–367 (2001). 10.1121/1.1369098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson L. C. and Bogert B. P., “A dynamical theory of the cochlea,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 22, 369–381 (1950). 10.1121/1.1906615 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon Y. J., Puria S., and Steele C. R., “Intracochlear pressure and derived quantities from a three-dimensional model,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 122, 952–966 (2007). 10.1121/1.2747162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zinn C., Maier H., Zenner H. P., and Gummer A. W., “Evidence for active, nonlinear, negative feedback in the vibration response of the apical region of the in-vivo guinea-pig cochlea,” Hear. Res. 142(1–2), 159–183 (2000). 10.1016/S0378-5955(00)00012-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson M., “Interferometry data challenge prevailing view of wave propagation in the cochlea,” Phys. Today 61(4), 26–27 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Cooper N. P. and Rhode W. S., “Mechanical responses to two-tone distortion products in the apical and basal turns of the mammalian cochlea,” J. Neurophysiol. 78(1), 261–270 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemp D. T., “Simulated acoustic emissions from within the human auditory system,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 64, 1386–1391 (1978). 10.1121/1.382104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhode W. S. and Cooper N. P., “Two-tone suppression and distortion production on the basilar-membrane in the hook region of cat and guinea-pig cochleae,” Hear. Res. 66(1), 31–45 (1993). 10.1016/0378-5955(93)90257-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smoorenburg G. F., “Combination tones and their origin,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 52, 615–632 (1972). 10.1121/1.1913152 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gorga M. P., Neely S. T., Ohlrich B., Hoover B., Redner J., and Peters J., “From laboratory to clinic: A large scale study of distortion product otoacoustic emissions in ears with normal hearing and ears with hearing loss,” Ear Hear. 18(6), 440–455 (1997). 10.1097/00003446-199712000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong W. and Olson E. S., “Supporting evidence for reverse cochlear traveling waves,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 123, 222–240 (2008). 10.1121/1.2816566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren T. Y., He W. X., Scott M., and Nuttall A. L., “Group delay of acoustic emissions in the ear,” J. Neurophysiol. 96, 2785–2791 (2006). 10.1152/jn.00374.2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He W., Fridberger A., Porsov E., Grosh K., and Ren T., “Reverse wave propagation in the cochlea,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105(7), 2729–2733 (2008). 10.1073/pnas.0708103105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Boer E., Zheng J., Porsov E., and Nuttall A. L., “Inverted direction of wave propagation (IDWP) in the cochlea,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 123(3), 1513–1521 (2008). 10.1121/1.2828064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong W. and Olson E. S., “Local cochlear damage reduces local nonlinearity and decreases generator-type cochlear emissions while increasing reflector-type emissions,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 127, 1422–1431 (2010). 10.1121/1.3291682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meenderink S. W. F. and van der Heijden M., “Reverse cochlear propagation in the intact cochlea of the gerbil: Evidence for slow traveling waves,” J. Neurophysiol. 103, 1448–1455 (2010). 10.1152/jn.00899.2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren T. Y., “Reverse propagation of sound in the gerbil cochlea,” Nat. Neurosci. 7(4), 333–334 (2007). 10.1038/nn1216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talmadge C. L., Tubis A., Long G. R., and Tong C., “Experimental confirmation of the two-source interference model for the fine structure of distortion product otoacoustic emissions,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 105(6), 275–292 (1999). 10.1121/1.424584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zweig G. and Shera C. A., “The origin of periodicity in the spectrum of evoked otoacoustic emissions,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 98(4), 2018–2047 (1995). 10.1121/1.413320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Boer E., “Mechanics of the cochlea: Modeling efforts,” in The Cochlea, edited by Dallos P., Popper A., and Fay R. (Springer-Verlag, New York, 1996), pp. 258–317. [Google Scholar]

- de Boer E., Nuttall A. L., and Shera C. A., “Wave propagation patterns in a ‘classical’ three-dimensional model of the cochlea,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 121(1), 352–362 (2007). 10.1121/1.2385068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sisto R., Moleti A., Botti T., Bertaccini D., and Shera C. A., “Distortion products and backward-traveling waves in nonlinear active models of the cochlea,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 129(5), 3141–3152 (2011). 10.1121/1.3569700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews J. W. and Molnar C. E., “Modeling intracochlear and ear canal distortion product 2f1-f2,” in Peripheral Auditory Mechanisms, edited by Allen J. B., Hall J. L., Hubbard A., Neely S. T., and Tubis A. (Springer-Verlag, Berlin, 1985), pp. 258–266. [Google Scholar]

- Vetesnik A., Nobili R., and Gummer A., “How does the inner ear generate distorsion product otoacoustic emissions?,” J. Otorhinolaryngol. Relat. Spec. 68, 347–352 (2006). 10.1159/000095277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramamoorthy S., Deo N. V., and Grosh K., “A mechano-electro-acoustical model for the cochlea: Response to acoustic stimuli,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 121(5), 2758–2773 (2007). 10.1121/1.2713725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meaud J. and Grosh K., “The effect of tectorial membrane and basilar membrane longitudinal coupling in cochlear mechanics,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 127(3), 1411–1421 (2010). 10.1121/1.3290995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wit H. P., Thalen E. O., and Albers F. W. J., “Dynamics of inner ear pressure release, measured with a double-barreled micropipette in the guinea pig,” Hear. Res. 132, 131–139 (1999). 10.1016/S0378-5955(99)00048-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosowski J. J., “Models of external and middle ear function,” in Auditory Computation, edited by Hawkins H., McMullen T., Popper A., and Fay R. (Springer-Verlag, New York, 1996), Chap. 2, pp. 15–61. [Google Scholar]

- Meaud J. and Grosh K., “Coupling active hair bundle mechanics, fast adaptation, and somatic motility in a cochlear model,” Biophys. J. 100(11), 2576–2585 (2011). 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.04.049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez C., “Dimensions of the cochlea (guinea pig),” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 24(5), 519–523 (1952). 10.1121/1.1906929 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Raphael Y. and Altschuler R. A., “Structure and innervation of the cochlea,” Brain Res. Bull. 60, 397–422 (2003). 10.1016/S0361-9230(03)00047-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gummer A. W., Johnstone B. M., and Armstrong N. J., “Direct measurement of basilar membrane stiffness in guinea pig,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 70(5), 1298–1309 (1981). 10.1121/1.387144 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zwislocki J. J. and Cefaratti L. K., “Tectorial membrane ii: Stiffness measurement in vivo,” Hear. Res. 42 (2–3), 211–228 (1989). 10.1016/0378-5955(89)90146-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallos P., “Organ of corti kinematics,” J. Assoc. Res. Otolaryngol. 4(3), 416–421 (2003). 10.1007/s10162-002-3049-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strelioff D. and Flock A., “Stiffness of sensory-cell hair bundles in the isolated guinea-pig cochleas,” Hear. Res. 15(1), 19–28 (1984). 10.1016/0378-5955(84)90221-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He D. Z. Z. and Dallos P., “Properties of voltage-dependant somatic stiffness of cochlear outer hair cells,” J. Assoc. Res. Otolaryngol. 01, 64–81 (2000). 10.1007/s101620010006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwasa K. H. and Adachi M., “Force generation in the outer hair cell of the cochlea,” Biophys. J. 73, 546–555 (1997). 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78092-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng J. F., Deo N., Zou Y., Grosh K., and Nuttall A. L., “Chlorpromazine alters cochlear mechanics and amplification: In vivo evidence for a role of stiffness modulation in the organ of corti,” J. Neurophysiol. 97(2), 994–1004 (2007). 10.1152/jn.00774.2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strelioff D., “Computer-simulation of generation and distribution of cochlear potentials,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 54(3), 620–629 (1973). 10.1121/1.1913642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyamshev L. M., “A question in connection with the principle of reciprocity in acoustics,” Sov. Phys. Dokl. 4, 406–409 (1959). [Google Scholar]

- Parthasarathi A. A., “Numerical modeling and electro-acoustic stimulus response analysis for cochlear mechanics,” PhD thesis, University of Michigan, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Watts L., “The mode-coupling Liouville-Green approximation for a two-dimensional cochlear model,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 108(5), 2266–2271 (2000). 10.1121/1.1310194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puria S., O’Connor K., Yamada H., Shimizu Y., Popelka G., and Steele C., “Do otoacoustic emissions travel in the cochlea via slow or fast waves?,” in 32nd MidWinter Meeting on Association for Research in Otolaryngology, February 14–19, 2009.

- Papoulis A., Signal Analysis (McGraw-Hill, New York, 1984), pp. 66, 123. [Google Scholar]

- Siegel J. H., Cerka1 A. J., Recio-Spinoso A., Temchin A. N., van Dijk P., and Ruggero M. A., “Delays of stimulus-frequency otoacoustic emissions and cochlear vibrations contradict the theory of coherent reflection filtering,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 118(4), 2434–2443 (2005). 10.1121/1.2005867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruggero M. A., “Comparison of group delays of 2f1-f2 distortion product otoacoustic emissions and cochlear travel times,” ARLO 5(4), 142–147 (2004). 10.1121/1.1771711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin G. K., Stagner B. B., and Lonsbury-Martin B. L., “Evidence for basal distortion-product otoacoustic emission components,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 127(5), 2955–2972 (2010). 10.1121/1.3353121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]