Abstract

Detection of pathogenic nucleic acids is essential for mammalian innate immunity. IFN-inducible protein IFI16 has emerged as a critical sensor for detecting pathogenic DNA, stimulating both type I IFN and proinflammatory responses. Despite being predominantly nuclear, IFI16 can unexpectedly sense pathogenic DNA in both the cytoplasm and the nucleus. However, the mechanisms regulating its localization and sensing ability remain uncharacterized. Here, we propose a two-signal model for IFI16 sensing. We first identify an evolutionarily conserved multipartite nuclear localization signal (NLS). Next, using FISH and immunopurification, we demonstrate that IFI16 detects HSV-1 DNA primarily in the nucleus, requiring a functional NLS. Furthermore, we establish a localization-dependent IFN-β induction mediated by IFI16 in response to HSV-1 infection or viral DNA transfection. To identify mechanisms regulating the secondary cytoplasmic localization, we explored IFI16 posttranslation modifications. Combinatorial MS analyses identified numerous acetylations and phosphorylations on endogenous IFI16 in lymphocytes, in which we demonstrate an IFI16-mediated IFN-β response. Importantly, the IFI16 NLS was acetylated in lymphocytes, as well as in macrophages. Mutagenesis and nuclear import assays showed that NLS acetylations promote cytoplasmic localization by inhibiting nuclear import. Additionally, broad-spectrum deacetylase inhibition triggered accumulation of cytoplasmic IFI16, and we identify the acetyltransferase p300 as a regulator of IFI16 localization. Collectively, these studies establish acetylation as a molecular toggle of IFI16 distribution, providing a simple and elegant mechanism by which this versatile sensor detects pathogenic DNA in a localization-dependent manner.

Keywords: proteomics, HIN200 protein, posttranslational modification, mass spectrometry, histone deacetylase

The onset of mammalian innate immunity is marked by recognition of pathogen-associated molecular patterns by a repertoire of host sensors. Cellular localizations, target specificities, and downstream signaling pathways define their functions. The IFN-inducible HIN200 protein IFI16 has recently emerged as a critical DNA sensor that stimulates innate immunity. IFI16 is required for IFN-β production on dsDNA transfection and HSV-1 infection (1). IFI16 binds dsDNA via its C-terminal HIN domains (1, 2) and associates with the endoplasmic reticulum protein STING, triggering TBK1-dependent IFN-β induction (1). Additionally, DNA-stimulated IFI16 triggers inflammasome assembly upon Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpes virus (KSHV) infection, promoting secretion of proinflammatory cytokines (3). Interestingly, another HIN200 protein, AIM2, also initiates DNA-dependent inflammasome assembly (4–7).

Although IFI16 targets and downstream pathways are starting to be defined, there are important unanswered questions regarding its cell type-dependent and dynamic subcellular localization. IFI16 is a predominantly nuclear protein (8) in lymphoid, epithelial, endothelial, and fibroblast tissues, as reviewed by Veeranki and Choubey (9). However, its cytoplasmic localization has also been reported in macrophages (1), cells essential for DNA-induced innate immunity (10). Consistent with its dual subcellular localization, recent reports suggest that IFI16 can sense pathogenic DNA in both the cytoplasm and the nucleus. Endogenous IFI16 was shown to colocalize with transfected vaccinia virus (VACV) dsDNA in the cytoplasm of differentiated THP-1 monocytes (1). In contrast, nuclear IFI16 colocalized with KSHV DNA during early infection, consequently activating inflammasome formation (3). These findings contradict the canonical notion that sensing of pathogenic DNA is solely a cytoplasmic process, suggesting that both cytoplasmic and nuclear IFI16 may participate in viral DNA surveillance. Hence, it is critical to understand the localization-dependent DNA sensing properties of IFI16. As reported for other innate sensors (e.g., Toll-like receptors), immune response may be dictated by the sensing context and cell type (11, 12). However, the precise molecular mechanisms regulating IFI16 localization remain uncharacterized. Furthermore, the roles of subcellular localization in its DNA sensing function have not been assessed.

Here, we used an integrative multidisciplinary approach to provide evidence for a two-signal model for the function of IFI16 as a pathogenic DNA sensor. We define an evolutionarily conserved multipartite nuclear localization signal (NLS) required for IFI16 sensing of HSV-1 viral DNA in the nucleus. We identify NLS acetylation as a molecular toggle of IFI16 localization and p300 as a contributing acetyltransferase. Collectively, our results provide critical insights into how IFI16 expands its range of surveillance against pathogenic DNA in a localization-dependent manner.

Results

IFI16 Has a Multipartite NLS.

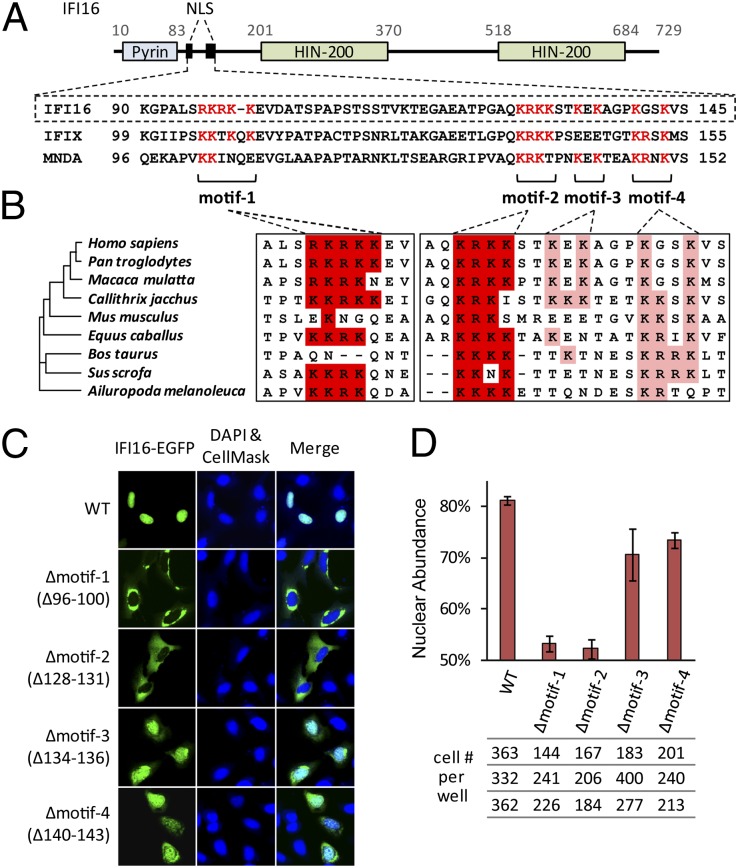

To study mechanisms regulating its localization, we first searched for IFI16 NLS motifs. A putative bipartite NLS (residues 96–135) that included two lysine/arginine-rich motifs, 96RKRKK100 (motif-1) and 128KRKK132 (motif-2), was predicted (Fig. 1A and Fig. S1A). Indeed, a peptide including motif-2, 127QKRKKSTKEKA138, was shown to mediate nuclear import of a GST-peptide fusion (13). NLS motif-1 and motif-2 are conserved among nuclear HIN200 proteins MNDA and IFIX, as well as in mammalian IFI16 homologs (Fig. 1 A and B and Fig. S1B). IFI16 also contains partial NLS motifs that we termed motif-3 and motif-4. Interestingly, in Bos taurus and Sus scrofa, motif-4 resembles a complete NLS motif and the murine counterpart can mediate nuclear localization (14). These partial motifs may be less active in primates because of amino acid substitutions. Together, these observations indicate that a multipartite NLS is a common feature of nuclear HIN200 proteins.

Fig. 1.

Nuclear localization of IFI16 requires a multipartite NLS. (A) Schematic of IFI16 and alignment of the multipartite NLS of IFI16, IFIX, and MNDA. (B) Alignment of NLS sequences of mammalian IFI16 homologs. (C) Fluorescent microscopy of IFI16-EGFP WT and NLS deletion mutants (transient transfections in U2OS cells) with 20× objective. The nucleus is stained with DAPI, and the cytoplasm is stained with CellMask. (D) Quantification of relative nuclear abundances by an Operetta screen (mean ± SD of 3 biological replicates).

Although the high degree of conservation suggests critical functions, the contributions of these motifs to nuclear import of full-length IFI16 remain elusive. To determine their functions, we constructed deletions of motif-1 (residues 96–100), motif-2 (residues 128–131), motif-3 (residues 134–136), and motif-4 (residues 140–143) in full-length IFI16 C-terminally tagged with EGFP. Following transient expression in human osteosarcoma (U2OS) cells (Fig. 1C), WT IFI16 localized predominantly to the nucleus. In contrast, both Δmotif-1 and -2 mutants had predominant cytoplasmic localizations, indicating that both motifs are nonredundant and essential for nuclear localization. By comparison, Δmotif-3 and -4 remained mostly nuclear, with minor cytoplasmic localization. These subcellular distributions were quantified using a high-throughput screen (Fig. 1D). Although dynamic range was limited by out-of-plane signal, these data recapitulated the microscopy results. Our results demonstrate that IFI16 has an evolutionarily conserved multipartite NLS consisting of two essential motifs (1, 2) and two accessory motifs (3, 4).

IFI16 Sensing of Viral DNA is Localization-Dependent.

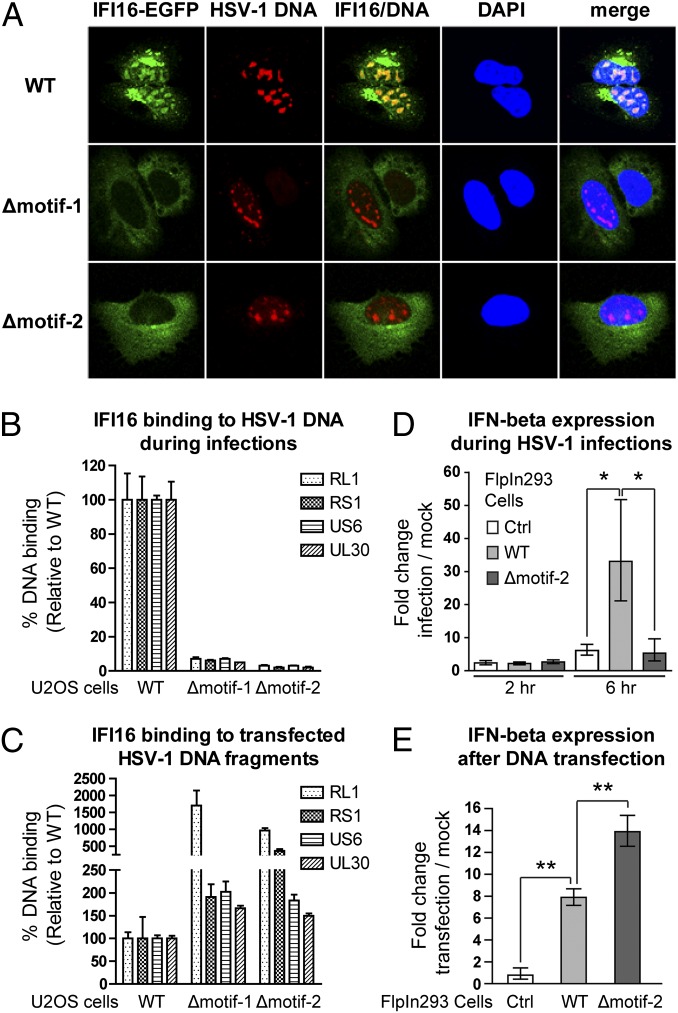

The distinct localization of the NLS mutants allowed us to test if IFI16 localization influences its sensing of various pathogens. Herpesviruses deposit and replicate their dsDNA genome in the host nucleus. Previous studies suggest that IFI16 can sense herpesvirus dsDNA in the cytoplasm (1) or nucleus (3). To determine if IFI16 localization is a critical determinant of sensing herpesvirus DNA, we infected U2OS cell lines stably expressing WT IFI16-EGFP or NLS deletion mutants (Δmotif-1 and Δmotif-2; Fig. S2) with HSV-1. Localization-dependent DNA sensing was assessed by FISH and protein-DNA coimmunopurification (co-IP). At 2 h postinfection (hpi), prominent colocalization of IFI16 and HSV-1 DNA was observed for WT IFI16-EGFP, but not for cytoplasmic NLS mutants (Fig. 2A). As reported for KSHV infection, a subset of WT IFI16 translocated into the cytoplasm (3). Consistent with the FISH data, co-IP assays showed a 10-fold increase in DNA binding level for WT IFI16-EGFP relative to NLS mutants (Fig. 2B). To exclude the possibility that NLS deletion disrupts DNA binding, a mixture of four HSV-1 DNA fragments was transfected into the same U2OS cell lines. Subsequent co-IP demonstrated that NLS mutants retained DNA-binding activity (Fig. 2C). In fact, their binding was consistently greater than that of nuclear WT IFI16, likely because transfected DNA first enters the cytoplasm and is more rapidly detected by the cytoplasmic NLS mutants. Together, these data demonstrate that WT IFI16 recognizes HSV-1 DNA primarily in the nucleus and that detection of nuclear viral DNA requires a functional NLS. To correlate this localization-dependent DNA binding with an immune response, we monitored expression of IFN-β following HSV-1 infections or DNA transfections. The U2OS cell lines described above contain a considerable level of endogenous IFI16, in addition to the EGFP-tagged IFI16. Therefore, FlpIn293 cell lines that express nuclear IFI16 or cytoplasmic Δmotif-2 were constructed. EGFP-tagged IFI16 maintained the IFN stimulatory function upon DNA transfections (Fig. S3). The 293 cells express low levels of endogenous IFI16 (Fig. S4) and are known to be poorly responsive to DNA transfections (1), thereby enabling us to study IFI16-mediated IFN response. Consistent with differential levels of DNA binding, nuclear WT IFI16 mediated the highest IFN response following HSV-1 infections at 6 hpi (Fig. 2D), whereas cytoplasmic Δmotif-2 was more responsive to transfected VACV 70mer DNA (Fig. 2E). Interestingly, for both WT and Δmotif-2, there was no significant IFN-β induction at 2 hpi. In view of the prominent IFI16 DNA binding at 2 hpi in U2OS cells (Fig. 2 A and B), the lack of IFN-β induction at 2 hpi in 293 cells could reflect a difference in the infection kinetics in different cell types. Additionally, the differences between 2 and 6 hpi may be attributable to the chronological order for DNA binding and the downstream outcome of IFN-β induction. Altogether, our results indicate that the IFI16-mediated IFN response to foreign DNA is indeed localization-dependent.

Fig. 2.

IFI16 sensing of viral DNA is localization-dependent. Cells were infected with HSV-1 for the indicated times (A, B, and D) or transfected with a mixture of four HSV-1 DNA fragments (C) or VACV 70mer DNA (E) for 3 h. (A) FISH assays demonstrate colocalization of HSV-1 genomic DNA with WT IFI16 but not with NLS mutants at 2 hpi of HSV-1 infection in U2OS cells 63× oil objective. (B) At 2 hpi, nuclear IFI16 binds more HSV-1 DNA than the NLS mutants in U2OS cells, as measured by co-IP of protein–DNA complexes and qPCR with four HSV-1 primer sets. DNA levels were normalized to isolated protein levels. (C) Cytoplasmic NLS mutants bind more transfected HSV-1 DNA fragments. (D and E) IFN-β expression following HSV-1 infection (2 and 6 hpi) or VACV 70mer transfection in FlpIn293 cells was quantified by qPCR and normalized to corresponding mock treatments. Mean ± SD, n = 3. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

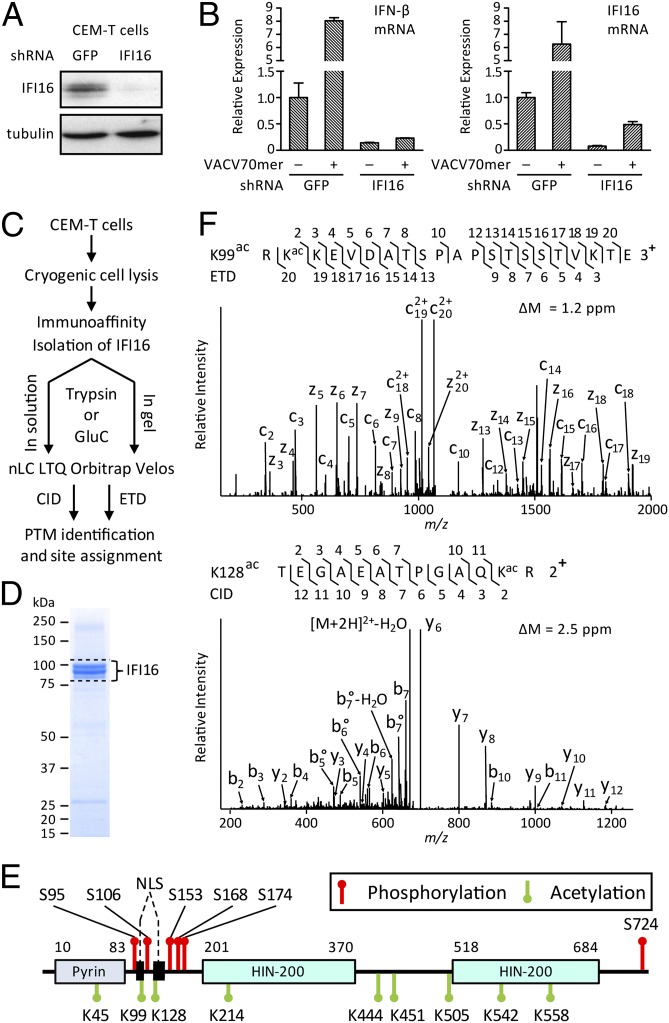

Endogenous IFI16 Is Acetylated Within NLS.

Because cytoplasmic NLS mutants can sense transfected DNA, the dynamic localization of IFI16 can act to extend its range of DNA surveillance. Posttranslational modification (PTM) is a possible mean for regulating IFI16 subcellular localization (15). To identify PTMs within endogenous IFI16, we designed a targeted proteomics approach, integrating cryogenic cell lysis, rapid immunoaffinity purification, and MS (16) (Fig. 3C). Human CEM-T lymphoblast-like cells were selected for these analyses because they abundantly express IFI16 (Fig. S4A); using shRNA knockdown, we demonstrated that in lymphocytes, as in macrophages, endogenous IFI16 is required for the IFN-β response to VACV 70mer DNA (Fig. 3 A and B). Endogenous IFI16 was efficiently isolated (Fig. 3D), digested in-gel or in-solution (17, 18) with trypsin or GluC, and analyzed by nano liquid chromatography (nLC) coupled MS/MS with two complementary fragmentation techniques, collision-induced dissociation (CID) and electron transfer dissociation (ETD). An almost complete IFI16 sequence coverage was obtained (>95%; Fig. S4B), leading to high-confidence identification of six phosphorylation and nine acetylation sites (Fig. 3E, Fig. S4 C and D, and Table S1). The majority of these PTMs have not been previously reported (Table S2). Thus, we present the most comprehensive map of IFI16 phosphorylations and acetylations to date (Fig. 4C).

Fig. 3.

Endogenous IFI16 is acetylated within the NLS and mediates a type I IFN response in lymphocytes. shRNA-mediated knockdown of IFI16 (A) compromises IFN-β expression in response to VACV 70mer transfection in CEM-T lymphocytes (B). (C) Combinatorial mass spectrometric approach to identify PTMs on endogenous IFI16 from CEM-T cells. (D) Coomassie-stained SDS/PAGE shows efficient IFI16 isolation; dotted lines indicate IFI16 isoforms. (E) Map of IFI16 phosphorylations (red pins) and acetylations (green pins). (F) Identification of NLS acetylations (ac) using ETD and CID MS/MS.

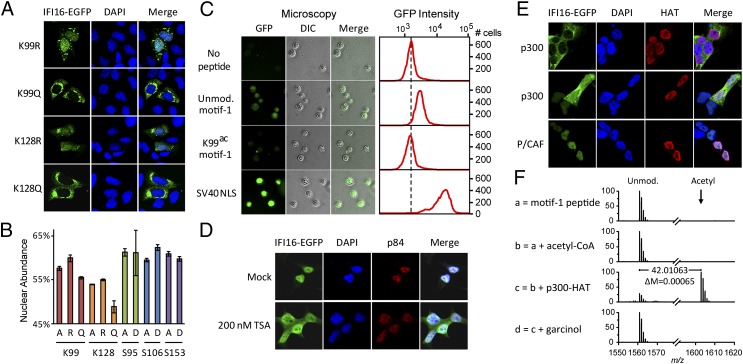

Fig. 4.

IFI16 NLS acetylation prevents nuclear import. (A) Confocal microscopy of K99 and K128 mutants 40× objective. (B) Relative nuclear abundance of IFI16 mutants quantified by an Operetta screen. (C) (Left) Direct fluorescence images illustrate the nuclear import levels for peptidyl GST-EGFP proteins. DIC, differential interference contrast microscopy. Magnification, 20× objective. (Right) Fluorescence intensity histograms of 104 nuclei measured by flow cytometry reflect import levels. The FlnIn293 IFI16-EGFP cell line was treated with trichostatin A (TSA) or mock for 6 h (D) or transfected with p300-myc or P/CAF-FLAG for 12 h (E). Localization of IFI16-EGFP, nuclear matrix protein p84, and acetyltransferases was visualized by confocal microscopy with a 63× objective. (F) IFI16 motif-1 peptide can be acetylated by the catalytic domain of p300 acetyltransferase in vitro.

Notably, all identified phosphorylations (Fig. 4E, red pins) cluster within two predicted nonstructured regions of IFI16: the linker region (S95, S106, S153, S168, and S174) and the C terminus (S724). In contrast, lysine acetylations (Fig. 4E, green pins) were distributed within Pyrin (K45) or HIN (K214, K542, and K558) domains or between HIN domains (K444, K451, and K505). Importantly, we found that the two major NLS motifs (motif-1 and motif-2) each contain acetylations at K99 and K128, respectively (Fig. 4D).

The K99 acetylation was also observed in endogenous IFI16 in THP-1 monocytes and ectopically expressed IFI16 in FlpIn293 cells (Fig. S5), indicating that NLS acetylation is a common event in multiple cell types. Because acetylation neutralizes the positive charge of the lysine, this modification may disrupt NLS binding to karyopherins of the nuclear translocation machinery (19), leading to cytoplasmic accumulation. Consistent with this hypothesis, the low levels of NLS acetylation present in CEM-T cells correlate with the minor fraction of IFI16 localized to the cytoplasm in these cells (Fig. S6A). Noteworthy, both lysine sites are highly conserved among IFI16 homologs and HIN200 family members, suggesting a common regulation of subcellular localization by acetylation.

Acetylation Within NLS Inhibits Nuclear Import.

To evaluate the impact of PTMs on NLS function, we assessed subcellular localizations of IFI16-EGFP mutants for K99 and K128 within the NLS, as well as adjacent S95, S106, and S153. Lysines were mutated to arginine (R) or glutamine (Q) to mimic the nonacetylated or acetylated state, respectively, and to nonfunctional alanine (A). Serines were mutated to nonphosphorylated A or phosphomimic aspartate (D). Localizations of these EGFP-tagged mutants were assayed by transient transfection in U2OS cells in a high-throughput screen (∼1,500 cells per sample; Fig. 4B). For both K99 and K128 sites, the relative nuclear abundances of Q and A mutants were significantly reduced compared with the R mutants, indicating that acetylation at these sites interferes with nuclear localization. Although both Q and A mutations disrupt the positive charges, Q mutants were more defective than A mutants, because the bulky side chain of Q may be less tolerated by the importin binding site. S95, S106, and S153 mutations did not significantly reduce nuclear localization, suggesting these phosphorylations have only minor roles in IFI16 localization. Consistently, confocal microscopy revealed a predominant cytoplasmic localization for acetyl-mimic mutants and partial rescue of nuclear localization for R mutants (Fig. 4A). These results indicate K99 and K128 are critical sites that have an impact on IFI16 localization.

Next, we tested if the reduced nuclear localization of acetyl-mimics resulted from inhibited nuclear import. An in vitro nuclear import assay (Fig. S7A) was performed using synthetic acetylated and unmodified motif-1 peptides (Fig. S7B). Equivalent amounts of the synthetic peptides were covalently conjugated to GST-EGFP cargos (Fig. S7C), and the resulting peptidyl-protein conjugates were incubated with isolated HeLaS3 nuclei in the presence of cytosolic extract and ATP. As observed by fluorescence microscopy and flow cytometry (Fig. 4C), motif-1 showed significant nuclear import activity. Nuclear import of motif-1 was less prominent than that of a strong monopartite NLS (SV40 large T antigen), consistent with motif-1 being part of a multipartite NLS. Importantly, the nuclear import activity of acetylated motif-1 peptide was drastically reduced, indicating that K99 acetylation can inhibit nuclear import.

p300 Regulates the Cytoplasmic Localization of Newly Synthesized IFI16.

Because acetylation affected IFI16 nuclear import, we predicted that inhibition of deacetylase activity would block nuclear import, promoting cytoplasmic accumulation of IFI16. To monitor the nuclear import of newly synthesized IFI16, we induced the expression of IFI16-EGFP by tetracycline in the FlpIn cell line. Although treatment with the sirtuin inhibitor nicotinamide did not affect IFI16 nuclear import (Fig. S6C), treatment with the broad-spectrum histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor trichostatin A led to significant accumulation of cytoplasmic IFI16-EGFP (Fig. 4D) in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. S6B). Cytoplasmic localization was not an artifact of compromised nuclear integrity, because nuclear marker p84 was not redistributed. These data suggest that HDACs regulate IFI16 localization, further supporting acetylation as a critical determinant of IFI16 cellular distribution. We also observed that K99 in motif-1 resembles a p300 acetylation motif, with a positively charged residue at position −3 (20), and that a p300 binding motif (21) is upstream of motif-1 (Fig. S6D). To test if p300 acetyltransferase regulates IFI16 localization, we transiently overexpressed p300 or P/CAF (P300/CBP-associated factor) in the IFI16-inducible cell line and assessed IFI16 localization (Fig. 4F). Although untransfected and P/CAF-transfected cells did not alter IFI16 localization, cells transfected with p300 displayed a striking IFI16 cytoplasmic accumulation of IFI16-EGFP. Additionally, we demonstrated that the purified p300 HAT domain has the ability to acetylate K99 in vitro (Fig. 4F and Fig. S6E). These results establish a role for p300 in regulating IFI16 localization.

Discussion

Localization-Dependent DNA Sensing.

Mammalian cells use nucleic acid sensing mechanisms for detecting intracellular pathogens in multiple cellular compartments. Cytoplasmic sensors, such as RIG-I- or Nod-like receptors and AIM2, patrol the cytosolic space, whereas membrane-bound Toll-like receptors guard endosomal compartments. Accumulating evidence indicates that activation of these pattern-recognition receptors requires not only nucleic acids of appropriate chemical nature but their relevant localization, suggesting a two-signal model for innate immunity (22).

Here, we assessed the role of cellular localization in mediating the DNA sensing function of the IFN-inducible protein IFI16, an emerging DNA sensor. The results from FISH, viral DNA binding, and IFN-β expression assays demonstrated that nuclear IFI16 localization is indeed essential for sensing HSV-1 DNA in the nucleus. Our result is consistent with the observation that nuclear IFI16 detects KSHV DNA to elicit an inflammatory response (3). Moreover, we previously showed that IFI16 binds the genomic DNA of human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) (23). Although this interaction was required for transcriptional activation of the immediate early promoter, it is possible that IFI16 may also detect HCMV DNA in the nucleus to elicit innate immunity. Because these viruses represent the three subfamilies of herpesviruses, α (HSV-1), β (HCMV), and γ (KSHV), we envisage that IFI16 could be a common nuclear DNA sensor for herpesviruses (Fig. 5).

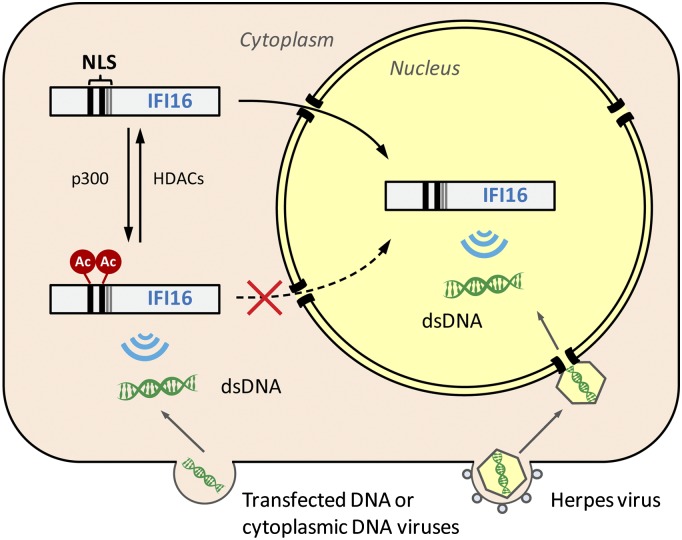

Fig. 5.

Working model for the localization-dependent sensing activity of IFI16. Detection of herpes viral DNA occurs in the nucleus, and detection of transfected DNA or cytoplasmic viral DNA occurs in the cytoplasm. A multipartite NLS is required for nuclear import. NLS acetylation impedes nuclear import of newly synthesized IFI16 and is regulated by HDACs and p300. Ac, lysine acetylation.

Why is DNA sensing critical in the nucleus? Herpesviruses replicate their dsDNA genomes in host nuclei and are known to evade host immunity (24). After cell entry, the viral genome is protected in the cytoplasm by the capsid before nuclear deposition. Indeed, our data show that HSV-1 DNA efficiently escapes the surveillance of cytoplasmic IFI16 mutants (Fig. 2B). Consequently, the host nucleus represents the last line of defense and a critical stage for detection of herpes virus DNA.

The nucleus was previously thought to be a “forbidden” zone for sensing, because an accurate mean of discriminating viral from host DNA in a single compartment seems challenging, although models have been hypothesized (25). Our results indicated that upon HSV-1 infection, the diffused nuclear localization of IFI16 (Fig. S2) was drastically altered, becoming concentrated within viral DNA-containing nuclear bodies (Fig. 2A). This localization change may suggest a higher affinity of IFI16 for viral DNA than for host chromosomes, an observation worthy of future investigation. In summary, our results lend significant support to establishing IFI16 as a nuclear DNA sensor and contribute previously undescribed evidence for localization-dependent sensing of pathogenic nucleic acids.

Redefining the IFI16 NLS.

Although a bipartite NLS encompassing region 127–145 was previously considered as the IFI16 NLS, an extensive characterization of NLS motifs was lacking before this study. To assess the localization-dependent DNA sensing functions of IFI16, we first predicted and experimentally confirmed its complete NLS motifs, identifying an evolutionarily conserved multipartite structure. The newly identified motif-1 was equally critical for nuclear localization as the reported motif-2, whereas motif-3 and motif-4 were less important, albeit indispensable for full function. Motif-1 and motif-2 comprise a consensus bipartite NLS structure (K/R)(K/R)X10–12(K/R)3/5 (19), with a spacer (27 aa) significantly longer than the canonical length (10–12 aa). Despite their scarcity, long spacers (16–37 aa) have been documented and supported by genetic (26) and structural (19) evidence. Thus, the newly defined IFI16 NLS, along with its counterparts in mammalian homologs, showcase additional examples of multipartite NLSs.

Acetylation as a Regulator of IFI16 Subcellular Localization.

To explore possible mechanisms underlying the unexplained cytoplasmic IFI16 localization, we constructed a comprehensive map of acetylations and phosphorylations in endogenous IFI16 using combinatorial MS. Our results revealed two critical acetylation sites that negatively regulate NLS function, indicating that impeded nuclear import could be a source for cytoplasmic IFI16. Thus, these acetylations can serve as a toggle to control the destination of newly synthesized IFI16 (Fig. 5). Importantly, the IFI16 NLS acetylation exists in various cell types, including CEM-T lymphocytes and differentiated THP-1 monocytes. Because we demonstrated that IFI16 sensing ability is localization-dependent, this toggle can expand its range of DNA surveillance. The presence of cytoplasmic IFI16 in macrophages and lymphocytes is in accordance with their specialized functions in eliciting systemic host immunity as a rapid response to viral DNA. Thus, promoting cytoplasmic localization of a DNA sensor, such as IFI16, may maximize immune system sensitivity to DNA viruses. From a regulatory perspective, NLS acetylation provides a simple and elegant mechanism for fine-tuning IFI16 distribution for its DNA sensing function or other localization-dependent activities.

Based on these findings, various IFI16 distributions may be achieved by differential acetyltransferase and deacetylase activities regulating NLS acetylation. Indeed, we show that p300 overexpression or HDAC inhibition triggers cytoplasmic accumulation of IFI16. It is tempting to hypothesize that the diverse IFI16 localizations observed in different cell types are modulated by cell type-specific activity levels of regulatory enzymes. At present, the number of NLS acetylations regulating cellular localization remains surprisingly low, because, to our knowledge, less than a dozen acetylated NLSs have been reported. The actual frequency of these phenomena may be underestimated. Recent large-scale proteomic studies have generated databases of protein acetylations (27, 28), highlighting acetylation as a more widespread modification than initially thought. By analyzing these databases, we noticed several acetylations within putative NLS motifs of other proteins, such as M phase phosphoprotein 8 (KAcAKAGKAcLK) and nucleolar protein 5 (KAKAcKAKAcIKVK). Considering that NLS acetylation could exist in low stoichiometry or within low-abundance proteins, it is likely that more sites will be identified through targeted approaches. Among the limited existing examples, the impact of acetylation on NLS function seems versatile, either promoting (29–31) or preventing (32, 33) nuclear import. Together with our findings for IFI16 acetylation, these studies exemplify diverse mechanisms by which acetylation can modulate NLS function.

In contrast to acetylation, phosphorylation is commonly reported as a modulator of NLS function. IFI16 was reported to be phosphorylated at unknown sites (8, 34, 35), and few PTM sites were identified via global whole-cell studies (Table S1). Additionally, an IFI16 peptide carrying the phospho-mimetic S132D could moderately compromise nuclear import in vitro, although this phosphorylation was not reported to exist in vivo (13). Our study identified both known and previously undescribed phosphorylations on endogenous IFI16, and indicated that the NLS phosphorylation sites S95, S106, and S153 have little impact on localization. These PTMs may play other functional or structural roles, or they may participate in crosstalk with other PTMs.

In summary, we report that IFI16 is a DNA sensor that possesses multiple acetylation and phosphorylation sites, as well as an evolutionarily conserved multipartite NLS. We demonstrate that sensing of pathogenic DNA by IFI16 is consistent with a two-signal model of innate immunity, depending on localization of both the sensor and pathogenic DNA target. We determine that IFI16 cellular distribution and sensing functions are modulated by a combination of genetically encoded (NLS) and posttranslational (acetylation) mechanisms, and we identify p300 as an enzyme involved in IFI16 regulation. These observations reveal a simple and elegant acetylation-dependent mechanism that fine-tunes the range of IFI16 surveillance activity to the benefit of host innate immunity.

Materials and Methods

Complete materials and methods are given in SI Materials and Methods. A brief description is provided below.

Cell Culture and Construction of Stable Cell Lines.

CEM-T, U2OS, Flp-In T-REx HEK293, and HeLaS3 cells were cultured using standard procedures. U2OS cell lines stably expressing IFI16-EGFP or mutants were generated by plasmid transfection, G418 selection, and flow cytometry sorting. Flp-In T-REx HEK293-inducible cell lines were constructed according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Life Technologies).

Fluorescence Imaging and Operetta Screen.

Cells were stained with anti-GFP (laboratory of I.M.C.) and anti-p84 (Abcam) antibodies, and visualized on a Zeiss LSM 510 (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging) or Leica TCS SP5 confocal microscope (Leica Microsystems). Relative nuclear abundances of IFI16-EGFP and mutants in U2OS cells were quantified on an Operetta system (PerkinElmer).

FISH.

U2OS cell lines for IFI16-EGFP or NLS mutants were infected with HSV-1 (strain 17+) at multiplicity of infection of 5. At 2 hpi, cells were immunostained for GFP. HSV-1 genome was stained by FISH, and FISH probes were nick-translated using pBAC HSV-1 with Cy3-dCTP labeling (PerkinElmer).

Protein–DNA Complex Co-IP.

HSV-1–infected or DNA-transfected U2OS cells were cross-linked with 1% paraformaldehyde and lysed in buffer by sonication. IFI16 protein–DNA complexes were affinity-purified on magnetic beads and reverse cross-linked. Two-thirds of the sample was digested with proteinase K. DNA was purified and quantified by quantitative PCR (qPCR) with four HSV-1 primers (Table S3). One-third of the sample was digested with DNase I. Isolated IFI16 was quantified by Western blot and densitometry to normalize the qPCR data.

Isolation of Endogenous IFI16 and Enzymatic Digestion.

CEM-T cells were harvested, cryogenically disrupted, and lysed in buffer: 20 mM K-Hepes (pH 7.4), 0.1 M KoAc, 2 mM MgCl2, 0.1% Tween-20, 1 μM ZnCl2, 1 μM CaCl2, 0.6% Triton X-100, 0.2 M NaCl, and 10 μg/mL DNase I, plus protease and phosphatase inhibitor mixtures. IFI16 was affinity-purified on M-270 epoxy magnetic beads (Life Technologies) conjugated with anti-IFI16 antibodies (1:1 wt/wt of 50004 and 55328; Abcam) at 4 °C for 1 h. For in-gel digestion, IFI16 was resolved by SDS/PAGE, excised, and digested with trypsin (Promega) or endoproteinase Glu-C (Roche). Peptides were extracted in 1% formic acid (FA) and 0.5% FA/0.5% acetonitrile. For in-solution digestion, we used an optimized filter-aided sample preparation method (18).

MS.

Peptides were separated by reverse phase liquid chromatography on an Ultimate 3000 nanoRSLC system (ThermoFisher Scientific) coupled online to an LTQ Orbitrap Velos ETD mass spectrometer (ThermoFisher Scientific). MS and data-dependent MS/MS scans were acquired sequentially. Peptide fragmentation used CID or ETD. MS/MS data were searched by SEQUEST in Proteome Discoverer (ThermoFisher Scientific) against a human protein database (SwissProt) and common contaminants, plus reversed sequences (21,569 entries). SEQUEST results were refined by X!Tandem in Scaffold (Proteome Software). Peptide probabilities were calculated by Percolator in Proteome Discover and PeptideProphet in Scaffold. PTM probabilities for site localization were scored using SLoMo (36).

Nuclear Import and in Vitro Acetylation Assays.

IFI16 motif-1 peptides were synthesized as unmodified or acetylated. For nuclear import assay, GST-GFP proteins were conjugated to NLS peptides and incubated with digitonin-permeabilized HeLaS3 nuclei (SI Materials and Methods). Nuclear import was assessed by microscopy and flow cytometry. For acetylation assay, unmodified motif-1 peptide was incubated with the recombinant catalytic domain of p300 acetyltransferase (Enzo Life Sciences) and analyzed on a MALDI LTQ Orbitrap mass spectrometer (ThermoFisher Scientific) (37).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank T. Greco, J. Wang (laboratory of I.M.C.), C. DeCoste, and J. Goodhouse (Core Facilities, Princeton University) for technical support and L. Runnels (University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey-Robert Wood Johnson Medical School), B. Sodeic (Hannover Medical School), and J. Flint (Princeton University) for sharing reagents. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health National Institute on Drug Abuse Grant DP1DA026192 and Human Frontier Science Program Organization Award RGY0079/2009-C (to I.M.C.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

*This Direct Submission article had a prearranged editor.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1203447109/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Unterholzner L, et al. IFI16 is an innate immune sensor for intracellular DNA. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:997–1004. doi: 10.1038/ni.1932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yan H, et al. RPA nucleic acid-binding properties of IFI16-HIN200. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1784:1087–1097. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2008.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kerur N, et al. IFI16 acts as a nuclear pathogen sensor to induce the inflammasome in response to Kaposi Sarcoma-associated herpesvirus infection. Cell Host Microbe. 2011;9:363–375. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2011.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fernandes-Alnemri T, Yu JW, Datta P, Wu J, Alnemri ES. AIM2 activates the inflammasome and cell death in response to cytoplasmic DNA. Nature. 2009;458:509–513. doi: 10.1038/nature07710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hornung V, et al. AIM2 recognizes cytosolic dsDNA and forms a caspase-1-activating inflammasome with ASC. Nature. 2009;458:514–518. doi: 10.1038/nature07725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roberts TL, et al. HIN-200 proteins regulate caspase activation in response to foreign cytoplasmic DNA. Science. 2009;323:1057–1060. doi: 10.1126/science.1169841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bürckstümmer T, et al. An orthogonal proteomic-genomic screen identifies AIM2 as a cytoplasmic DNA sensor for the inflammasome. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:266–272. doi: 10.1038/ni.1702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Choubey D, Lengyel P. Interferon action: Nucleolar and nucleoplasmic localization of the interferon-inducible 72-kD protein that is encoded by the Ifi 204 gene from the gene 200 cluster. J Cell Biol. 1992;116:1333–1341. doi: 10.1083/jcb.116.6.1333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Veeranki S, Choubey D. Interferon-inducible p200-family protein IFI16, an innate immune sensor for cytosolic and nuclear double-stranded DNA: Regulation of subcellular localization. Mol Immunol. 2012;49:567–571. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2011.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bauer M, Heeg K, Wagner H, Lipford GB. DNA activates human immune cells through a CpG sequence-dependent manner. Immunology. 1999;97:699–705. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1999.00811.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim YM, Brinkmann MM, Paquet ME, Ploegh HL. UNC93B1 delivers nucleotide-sensing toll-like receptors to endolysosomes. Nature. 2008;452:234–238. doi: 10.1038/nature06726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barbalat R, Ewald SE, Mouchess ML, Barton GM. Nucleic acid recognition by the innate immune system. Annu Rev Immunol. 2011;29:185–214. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-031210-101340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Briggs LJ, et al. Novel properties of the protein kinase CK2-site-regulated nuclear-localization sequence of the interferon-induced nuclear factor IFI 16. Biochem J. 2001;353:69–77. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ding B, Lengyel P. p204 protein is a novel modulator of ras activity. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:5831–5848. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709680200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Veeranki S, Choubey D. Interferon-inducible p200-family protein IFI16, an innate immune sensor for cytosolic and nuclear double-stranded DNA: Regulation of subcellular localization. Mol Immunol. 2011;49:567–571. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2011.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cristea IM, Williams R, Chait BT, Rout MP. Fluorescent proteins as proteomic probes. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2005;4:1933–1941. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M500227-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Greco TM, Yu F, Guise AJ, Cristea IM. Nuclear import of histone deacetylase 5 by requisite nuclear localization signal phosphorylation. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2011;10 doi: 10.1074/mcp.M110.004317. M110.004317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tsai YC, Greco TM, Boonmee A, Miteva Y, Cristea IM. Functional Proteomics Establishes the Interaction of SIRT7 with Chromatin Remodeling Complexes and Expands Its Role in Regulation of RNA Polymerase I Transcription. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2012;11:60–76. doi: 10.1074/mcp.A111.015156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Conti E, Kuriyan J. Crystallographic analysis of the specific yet versatile recognition of distinct nuclear localization signals by karyopherin alpha. Structure. 2000;8:329–338. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(00)00107-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thompson PR, Kurooka H, Nakatani Y, Cole PA. Transcriptional coactivator protein p300. Kinetic characterization of its histone acetyltransferase activity. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:33721–33729. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104736200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.O’Connor MJ, Zimmermann H, Nielsen S, Bernard HU, Kouzarides T. Characterization of an E1A-CBP interaction defines a novel transcriptional adapter motif (TRAM) in CBP/p300. J Virol. 1999;73:3574–3581. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.5.3574-3581.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fontana MF, Vance RE. Two signal models in innate immunity. Immunol Rev. 2011;243:26–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2011.01037.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cristea IM, et al. Human cytomegalovirus pUL83 stimulates activity of the viral immediate-early promoter through its interaction with the cellular IFI16 protein. J Virol. 2010;84:7803–7814. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00139-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Paludan SR, Bowie AG, Horan KA, Fitzgerald KA. Recognition of herpesviruses by the innate immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11:143–154. doi: 10.1038/nri2937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hornung V, Latz E. Intracellular DNA recognition. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10:123–130. doi: 10.1038/nri2690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Robbins J, Dilworth SM, Laskey RA, Dingwall C. Two interdependent basic domains in nucleoplasmin nuclear targeting sequence: Identification of a class of bipartite nuclear targeting sequence. Cell. 1991;64:615–623. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90245-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim SC, et al. Substrate and functional diversity of lysine acetylation revealed by a proteomics survey. Mol Cell. 2006;23:607–618. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Choudhary C, et al. Lysine acetylation targets protein complexes and co-regulates major cellular functions. Science. 2009;325:834–840. doi: 10.1126/science.1175371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Spilianakis C, Papamatheakis J, Kretsovali A. Acetylation by PCAF enhances CIITA nuclear accumulation and transactivation of major histocompatibility complex class II genes. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:8489–8498. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.22.8489-8498.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Santos-Rosa H, Valls E, Kouzarides T, Martínez-Balbás M. Mechanisms of P/CAF auto-acetylation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:4285–4292. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pickard A, Wong PP, McCance DJ. Acetylation of Rb by PCAF is required for nuclear localization and keratinocyte differentiation. J Cell Sci. 2010;123:3718–3726. doi: 10.1242/jcs.068924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.di Bari MG, et al. c-Abl acetylation by histone acetyltransferases regulates its nuclear-cytoplasmic localization. EMBO Rep. 2006;7:727–733. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Johnson-Saliba M, Siddon NA, Clarkson MJ, Tremethick DJ, Jans DA. Distinct importin recognition properties of histones and chromatin assembly factors. FEBS Lett. 2000;467:169–174. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)01142-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Johnstone RW, Kershaw MH, Trapani JA. Isotypic variants of the interferon-inducible transcriptional repressor IFI 16 arise through differential mRNA splicing. Biochemistry. 1998;37:11924–11931. doi: 10.1021/bi981069a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu C, et al. MyoD-dependent induction during myoblast differentiation of p204, a protein also inducible by interferon. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:7024–7036. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.18.7024-7036.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bailey CM, et al. SLoMo: Automated site localization of modifications from ETD/ECD mass spectra. J Proteome Res. 2009;8:1965–1971. doi: 10.1021/pr800917p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Luo Y, Li T, Yu F, Kramer T, Cristea IM. Resolving the composition of protein complexes using a MALDI LTQ Orbitrap. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2010;21:34–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2009.08.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.