Abstract

Objective

We examine the role of family- and individual-level protective factors in the relation between exposure to ethnic-political conflict and violence and post-traumatic stress among Israeli and Palestinian youth. Specifically, we examine whether parental mental health (lack of depression), positive parenting, children’s self-esteem, and academic achievement, moderate the relation between exposure to ethnic-political conflict/violence and subsequent post-traumatic stress (PTS) symptoms.

Method

We collected three waves of data from 901 Israeli and 600 Palestinian youths (three age cohorts: 8, 11, and 14 years old; approximately half of each gender) and their parents at 1-year intervals.

Results

Greater cumulative exposure to ethnic-political conflict/violence across the first two waves of the study predicted higher subsequent PTS symptoms even when we controlled for the child’s initial level of PTS symptoms. This relation was significantly moderated by a youth’s self-esteem and by the positive parenting received by the youth. In particular, the longitudinal relation between exposure to violence and subsequent PTS symptoms was significant for low self-esteem youth and for youth receiving little positive parenting but was non-significant for children with high levels of these protective resources.

Conclusions

Our findings show that youth most vulnerable to PTS symptoms as a result of exposure to ethnic-political violence are those with lower levels of self-esteem and who experience low levels of positive parenting. Interventions for war-exposed youth should test whether boosting self-esteem and positive parenting might reduce subsequent levels of PTS symptoms.

Keywords: Exposure to ethnic-political violence, protective factors, post-traumatic stress

The empirical literature on the effects of exposure to ethnic-political violence on youth is growing (e.g., Barber’s (2009) edited volume on Adolescents and War; special issues of Child Development [Volume 81, issue 4, 2010; Volume 67, issue 1, 1996] and the International Journal of Behavioral Development [Volume 32, issue 4, 2008]). Such exposure has deleterious impacts on youth (Betancourt et al., 2010; Cummings et al., 2010; Kithakye et al., 2010; Klasen et al., 2010; Layne et al., 2010; Qouta, Punamaki, & El Sarraj, 2008), most notably on post-traumatic stress (PTS) symptoms (Qouta et al., 2008). Yet, research also has indicated the resiliency of children exposed to ethnic-political violence (e.g., Cairns & Dawes, 1996; Garbarino & Kostelny, 1996; Punamaki, Qouta, & El Sarraj, 1997), highlighting the need to identify protective factors that might moderate the negative effects of this exposure. Because most of the empirical research has used cross-sectional designs (Barber & Schluterman, 2009), prospective studies are needed to draw more definitive causal conclusions about effects of exposure and potential protective factors on subsequent adjustment. In our 3-wave longitudinal study, we examine family (parental mental health and positive parenting strategies) and individual resources (self-esteem and academic achievement) that might protect Israeli and Palestinian youth from the potentially deleterious effects of exposure to ethnic-political conflict/violence on subsequent PTS symptoms.

Youths’ Exposure to Ethnic-Political Conflict/Violence and PTS Symptoms

Inter-ethnic and political conflicts are raging in many regions around the world, especially in the Middle East, where since the beginning of the second Intifada in September 2000 through the end of January 2011, at least 7,487 people have been killed, including 1,442 minors (B’Tselem, Israeli Information Center for Human Rights in the Occupied Territories). Exposure to extreme ethnic-political violence seems to interfere with the child’s cognitive and emotional processing of those experiences and leads to the three hallmark criteria for post-traumatic stress disorder (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; American Psychiatric Association, 2000): re-experiencing the event (e.g., intrusive memories, dreams); avoidance of stimuli associated with the events and emotional numbing; and symptoms of increased arousal (e.g., hypervigilance, irritability, sleep problems). Regarding youth in the Middle East, although a few studies have shown that the majority of youth exposed to extreme political violence in Gaza (e.g., bombardment of homes) exhibit PTSD (Qouta, Punamaki, & El Sarraj, 2003; Thabet, Tawahina, El Sarraj, & Vostanis, 2008), in general, the studies have shown only modest to moderate correlations between exposure and PTS symptoms (e.g., Abdeen, Qasrawi, Nabil, & Shaheen, 2008; Barber & Schluterman, 2009; Qouta, Punamaki, & El Sarraj, 2008; Slone, 2009; Thabet, Ibraheem, Shivram, Winter, & Vostanis, 2009; Victoroff et al., 2010), suggesting that there is remarkable resilience among youth. This has prompted researchers to stress the urgent need to identify factors that promote resiliency (Barber, 2009; Sagi-Schwartz, 2008; Seginer, 2008).

Our team’s prior experiences conducting research in the Middle East indicated that in order to assess the full range of political violence exposure and PTS symptoms among youth, we should include all three main ethnic subgroups: Palestinians living in Gaza and the West Bank; Israeli Jews; and Israeli Arabs, who make up 20% of the Israeli population. Landau et al. (2010) and Lavi and Solomon (2005) contrasted the cultural and socioeconomic differences, political attitudes, and daily life experiences of the groups. Lavi and Solomon found that Palestinian youth in Gaza were exposed to more political violence than their counterparts in Israel. Landau et al. found that Israeli Jewish youth reported higher levels of political violence exposure than Israeli Arabs, possibly because Israeli Jews are more likely to be the targets in the Palestinian-Israeli conflict. Lavi and Solomon also reported higher levels of PTS symptoms among Palestinians in Gaza compared to those in Israel, possibly due to their higher levels of violence exposure. Thus, by including all three groups, we expected to find a wider range of variability in exposure and in PTS symptoms than we would in any one group alone.

The Risk and Protective Factor Model

The risk and protective factor model of developmental psychopathology (Garmezy & Neuchterlein, 1972; Institute of Medicine, 2009; Rutter, 1990) has been the predominant framework for identifying ecological and individual factors that place children at risk for developing psychopathology and promote resilience, i.e., “the process of, capacity for, or outcome of successful adaptation despite challenging or threatening circumstances” (Masten et al., 1990, p. 426). Key studies identified common factors that promoted positive outcomes despite exposure to adverse conditions (e.g., Cowen, Wyman, Work, & Parker, 1990; Masten et al., 1990, 1999; Werner, 1993). These common factors included both family factors reflecting social support for the youth and individual and family factors that would promote the youths’ ability to cope with adverse situations. Family factors included: positive relationships between parents and their children, which included more age-appropriate and consistent discipline practices and affectional ties with the extended family. Individual factors included at least average intelligence, school adjustment, effective coping/problem-solving skills, and self-esteem.

Much of the literature on youth’s resilience to PTS comes from studies conducted on populations coping with large-scale natural disasters (e.g., LaGreca, Silverman, Lai, & Jaccard, 2010; LaGreca, Silverman, Vernberg, & Prinstein, 1996; LaGreca, Silverman, & Wasserstein, 1998; Prinsten, LaGreca, Vernberg, & Silverman, 1996; Vernberg, LaGreca, Silverman, & Prinstein, 1996). Weems and Overstreet (2009) suggested that such adverse conditions impact children’s perceptions of their physical security, self-efficacy, self-worth, and social relatedness, and their expected age-relevant role competencies (e.g., academic achievement, forming peer relationships) (Sandler, 2001; Sandler Miller, Short, & Wolchik, 1989). Protective factors seem to exert their effects in helping youth cope with the stress of disasters by restoring or supporting the child’s self-worth, security of social relations, and sense of control. At the level of the microsystem, family resources (e.g., positive parenting, parental mental health) provide support for youths that enhance their ability to cope; at the ontogenic level, factors within the child (e.g., self-esteem) can improve coping. In the literature on children’s responses to life disruptions caused by disasters, two particular family-level factors are often identified as affecting youths’ post-disaster coping and adjustment: parenting factors (e.g., monitoring, family cohesion, parenting efficacy, social support) and maternal psychological adjustment (Rowe, LaGreca, & Alexandersson, 2010; Scaramella, Sohr-Preston, Callahan, & Mirabile, 2008; Scheeringa & Zeanah, 2008; Spell et al., 2008). Individual-level factors have been shown to predict post-disaster coping and adjustment. First, pre-disaster psychological symptoms (e.g., trait anxiety, negative affect) predicted post-disaster posttraumatic stress symptoms, highlighting the importance of controlling for initial symptoms (LaGreca et al., 1998; Lengua, Long, Smith, & Meltzoff, 2005; Weems et al., 2007). In addition, academic achievement (LaGreca et al.), and self-esteem and social competence (Lengua et al.), predicted post-disaster adjustment.

Protective Factors for Youth Exposed to Ethnic-Political Conflict/Violence

There is less research on factors that specifically protect against the consequences of exposure to ethnic-political violence. It is important to assess whether protective factors identified in the broader literature are effective for children exposed to such an extreme stressor as ethnic-political violence. There is some reason to believe that they may lose their effectiveness. Luthar et al. (2000), for example, described how a resource (e.g., supportive parenting) may lose its effectiveness when the stressor becomes overwhelming. Family resources, for example, may lose their protective potency for youth exposed to high levels of community violence (e.g., Salzinger, Feldman, Rosario, & Ng-Mak, 2010).

Family-level factors

Evidence suggests strong support for two key family-level factors that moderate the link between exposure to political violence and psychosocial outcomes. First, a supportive, non-punitive parenting style appears to be protective. In a survey of 7,000 Palestinian youth two years after the First Intifada, Barber (1999) found that higher levels of perceived parental support were associated with positive adjustment, but higher levels of parental control were associated with negative outcomes. Punamaki et al. (1997) found that warm, supportive, and non-punitive parenting protected children exposed to military trauma from developing PTS symptoms and aggressive behavior. In one of the few longitudinal studies, Punamäki et al. (2001) assessed 86 Palestinian children during and three years after the Intifada. Children who were exposed to higher levels of violence and who reported passive responses to hypothetical scenes of Intifada-like violence had elevated PTSD outcomes; however, that association was not present for youth who perceived their mothers as non-rejecting and non-hostile.

Second, parental mental health seems to play a role in outcomes for children exposed to political violence. Laor, Wolmer, and Cohen (2001) reported on a 5-year longitudinal study of 107 Israeli children and their mothers whose homes were damaged during the Gulf War SCUD missile attack. There was a significant association between children’s internalizing and externalizing problems and their mothers’ psychological maladjustment. Qouta, Punamaki, and El Sarraj (2005) and Thabet et al. (2008) found that among Palestinians, mothers’ PTSD symptoms predicted their children’s PTSD symptoms. Within our data set, we can examine whether measures of positive parenting strategies and parental mental health moderate the effects of exposure to violence on their children.

Individual-level factors

At the individual level, few protective factors other than political ideology have been examined (e.g., Barber & Schluterman, 2009; Qouta et al., 2008), so it is unclear whether individual-level factors identified in the broader child resilience literature (e.g., academic/intellectual achievement, self-esteem; Cowen et al., 1990; Masten et al., 1999; Sandler, 2001; Werner, 1993) might also play a protective role for children exposed to political violence. Sandler (2001) suggested that “success in developmental tasks and associated competencies across the lifespan have been central to theories of resilience” (p. 29), and noted the strong connection between academic functioning and indices of mental health in youth. La Greca et al. (1998) found that children with higher academic skills over a year before exposure to Hurricane Andrew had lower levels of PTS symptoms 3 months post-hurricane. Perhaps children who are able to maintain success in academic achievement retain a sense of competence and efficacy that can counteract effects of adverse conditions. In terms of personality characteristics, Kliewer and Sandler (1992) theorized that children with higher levels of self-esteem might appraise stressors differently than children with lower levels of self-esteem (e.g., as a challenge for growth versus as a threat to their security), in turn influencing their reactions to stressors. Stress-buffering effects of self-esteem have been found for children exposed to abuse (Zimrin, 1986), interparental conflict (Neighbors, Forehand, & McVicare, 1993), and cumulative stressful events (Kliewer & Sandler, 1992). In our data set, we can examine whether academic achievement and self-esteem might protect children exposed to ethnic-political violence.

The Present Study

In the current study we report on data collected from a sample of 600 Palestinian and 901 Israeli children, equally distributed across three age cohorts (ages 8, 11, and 14), who were interviewed once a year for three consecutive years. We have reported initial empirical findings from this project. Dubow et al. (2010) and Landau et al. (2010) reported results from wave 1: exposure to ethnic-political conflict/violence was related both to aggression and PTS symptoms, even after controlling for a range of demographic and contextual factors. Boxer et al. (in press) found that political violence exposure predicted increases in violence at more proximal levels of the social ecology (e.g., school, community), but only political violence predicted subsequent aggression at peers across age groups. The present study is the only one that examines, prospectively, the role of protective factors in the relation between political violence exposure and subsequent PTS symptoms.

Based on the above theorizing, we first hypothesized that greater exposure to ethnic-political violence would be related longitudinally to higher levels of subsequent PTS symptoms independently of the level of initial PTS symptoms and demographic differences. Second, we predicted that the longitudinal relation would be moderated by both family-level (i.e., parent mental health, positive parenting) and individual-level factors (i.e., self-esteem and academic grades), such that higher levels of parental mental health, positive parenting, self-esteem, and academic achievement (grades) would attenuate the significant relation between exposure and PTS symptoms. Based on the distribution of war violence in Israel and Palestine, we also expected to observe the highest levels of exposure to violence among Palestinian youth, the next highest among Jewish Israeli youth, and the least among Arab Israeli youth; consequently, we expected that the frequency of PTS symptoms would vary among the samples in parallel with the pattern of exposure to violence.

Method

Sample

Three waves of data at one-year intervals were collected on samples of three age cohorts (ages 8, 11, and 14) of Palestinian and Israeli Arab and Jewish children (N = 1,501 at wave 1) between 2008 and 2010. The samples were drawn from the different ethnic groups and regions (e.g., Gaza versus West Bank) in order to maximize the variance in exposure to violence. At each wave, each selected child and the child’s parent were interviewed.

Palestinian sample

The Palestinian sample at wave 1 included 600 children: 200 8-year olds (101 girls, 99 boys), 200 11-year olds (100 girls, 100 boys) and 200 14-year olds (100 girls, 100 boys) and one of their parents (98% were mothers). Using census maps of the West Bank and Gaza provided by the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics, residential areas were sampled proportionally to achieve a representative sample of the general population. First, Palestinian areas were divided into two areas: West Bank (64% of the sample) and Gaza Strip (36% of the sample), and counting areas were divided according to size. One hundred counting areas were selected randomly. In each area, a sample was selected whereby 6 children would be interviewed, 3 males and 3 females divided equally over the three ages under examination. Houses in each counting area were divided to allow random selection of 6 homes. In the first home, an interview could be conducted with any one of the six types of children needed; if there was more than one child who fit the description, one was selected using Kish Household Tables. In the second home, the age/gender type of child selected in the previous home would be excluded and so the choices would become five, rather than six, and so on. Only 10% of families initially approached declined to participate. Staff from the Palestinian Center for Policy and Survey Research conducted the sampling and interviews.

Almost 100% (599/600) of the parents reported their religion as Muslim and 99% were married. One-third of the parents reported having at least a high school degree. Parents reported that on average, there were 4.89 (SD = 1.86) children in the home. These statistics are representative of the general population of Palestinians based on the 2007 census (Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics, 2008). At wave 2, 590 Palestinian children and their parents were again interviewed, for a resampling rate of 98%, and 572 Palestinian children and their parents were interviewed in wave 3 for a resampling rate of 95%. Differences in study variables related to attrition are reported in the Preliminary Analysis section of the Results.

Israeli sample

The Israeli sample included 901 children and their parents. The Arab group consisted of 450 children: 150 8-year olds (66 girls, 84 boys), 149 11-year olds (69 girls, 80 boys) and 151 14-year olds (79 girls, 72 boys) and one of their parents (68% were mothers). The Jewish group consisted of 451 children: 151 8-year olds (79 girls, 72 boys), 150 11-year olds (73 girls, 77 boys) and 150 14-year olds (94 girls, 56 boys) and one of their parents (87% were mothers).

In comparison to the level of violence in Palestine, the level of violence is relatively low in the major population centers of Israel; so, we oversampled high-risk areas. Of the Arab sample, 7% live in Jerusalem, 70% in the north (near the Lebanese border), and 23% in central Israel (low conflict area). Of the Jewish sample, 15% live in Jerusalem, 25% in the north, 23% in the south (around the Gaza Strip), 24% in the occupied West Bank, and 14% in central Israel. Families in these areas were randomly sampled three ways: (1) Recruitment by cluster sampling: Within the designated area, we randomly selected neighborhoods and streets, and the interviewers went door-to-door locating families with children fitting the sample; (2) Non-probability expansion of the sample: Interviewees were asked to recommend other families who fit the sample criteria. Each nominated family’s census data were verified, and if their demographic characteristics met the requirements, the family was included; and (3) Random dialing expansion of the sample: Random phone calls were made to households in the designated area. The respondents were asked to participate if they fit the sampling criteria.

Face-to-face interviews were scheduled for those who agreed to participate (55% in the Jewish sample and 65% in the Arab sample). Staff from the Mahshov Survey Research Institute conducted the sampling and interviews.

Among the Israeli Arab sample, 92% of the parents were married and 55%-60% did not graduate from high school. Parents reported that on average, there were 3.17 (SD = 1.39) children in the home. Among the Israeli Jewish sample, 91% of the parents were married and over 80% had graduated from high school. Parents reported that on average, there were 3.59 (SD = 1.83) children in the home. Among Israeli Arabs, in wave 2, 386 children and their parents were re-interviewed (86%); and at wave 3, 385 were re-interviewed (86%).

Among Israeli Jews, however, the wave 2 resampling rate was only 68%, with 305 children and their parents being interviewed; and in wave 3 it was 63%, with 282 children and their parents being interviewed. The decrement in the number of participants interviewed among Israeli Jews was mostly due to “refusals.” The refusing participants reported that they did not feel the monetary reimbursement was sufficient to justify their time. In fact, due to significant exchange rate changes, the amount of money offered to each participant was significantly less in waves 2 and 3. Because Arab Israelis had much lower average incomes, the amount was perceived as sufficient by most of them. Differences in study variables related to attrition are reported in the Preliminary Analysis section below.

Consent and Interview Procedures

The project was approved by the institutional review boards of the University of Michigan (Behavioral Sciences) and the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Participants were told that the study concerned the effects of ethnic-political conflict on children and their families, assessments would take one hour, and one parent and one child would be asked to participate. The voluntary and confidential nature of the study was emphasized. The family was compensated at the region’s wave 1 equivalent rate of $25. The interviews of the parent/child were conducted in the families’ homes separately and privately; the interviewers read the surveys to the respondents, who indicated their answers which were then recorded by the interviewer.

Measures

Over the first several months of the project, we met with our collaborators at the two sites (Hebrew University and the Palestinian Center for Policy and Survey Research) to choose measures (with a focus on those used previously in the Middle East when possible) and to adapt items, as needed. The original English measures were translated and back-translated for accuracy by native-speaking teams. Next, we conducted youth focus groups in each region for each age group separately, specifically to comment on exposure to ethnic-political conflict and violence; the goal was to insure that our survey items covered the broad array of events. Finally, we conducted two rounds of pilot testing of the survey on 9 parent/child dyads (three from each age group) in each region, which included asking participants to discuss any items or response formatting that caused confusion. The items and response formatting of the measures were found to be relevant and understandable across age groups. Interviews were conducted with same-ethnicity interviewers, and the surveys were presented in appropriate native languages (i.e., Hebrew for Israeli Jews and Arabic for Palestinians and Israeli Arabs; Israeli Arabs were able to select Hebrew or Arabic) with no variation between waves of data collection.

Demographic information

Parents reported basic demographic characteristics (e.g., child age, child gender). As an index of socioeconomic status, parent education was coded as follows: 1= illiterate to 10 = doctorate or law degree, and the mean of both parents’ educational levels was computed.

Exposure to ethnic-political conflict and violence

Parents of children in the 8-year old cohort reported on their children’s exposure to political conflict and violence in each wave, whereas children in the 11- and 14-year old cohorts provided self-reports in each wave.1 The exposure to political conflict and violence scale includes 24 items adapted from Slone et al. (1999; Slone, 2009) who designed this measure for Middle East youth. Respondents indicated the extent to which the child experienced the event in the past year along a 4-point scale (0 = never to 3 = many times). The items comprise the following domains of political conflict and violence events: loss of, or injury to, a friend or family member (5 items; e.g., “Has a friend or acquaintance of yours been injured as a result of political or military violence?”); non-violent events (6 items; e.g., “How often have you spent a prolonged period of time in a security shelter or under curfew?”); self or significant others participated in political demonstrations (3 items; e.g., “How often have you known someone who was involved in a violent political demonstration?”); witnessed actual violence (4 items asked Palestinians about exposure to violence perpetrated by Israelis, and the same 4 items asked Israelis about exposure to violence perpetrated by Palestinians; e.g., “How often have you seen right in front of you Palestinians (Israelis) being held hostage, tortured, or abused by Israelis (Palestinians?”); and witnessed media portrayals of violence (6 items, worded for Palestinians to reflect violence perpetrated by Israelis, and worded for Israelis to reflect violence perpetrated by Palestinians; e.g., “How often have you seen video clips or photographs of injured or martyred Palestinians (injured or dead Israelis) on stretchers or the ground because of an Israeli (Palestinian) attack?”). There were significant correlations among the five domains of exposure to political conflict/violence, and coefficient alphas for the full 24-item index across ethnic subgroups ranged from .77-.86 (parent report for youngest cohort) and .76-.79 (self report for older two cohorts) at wave 1 and .79-.84 (parent report for youngest cohort) and .75-.84 (self report for older two cohorts) at wave 2. As in our previous reports (Dubow et al., 2010; Landau et al., 2010), we used a total score that reflects the average of the responses to all 24 items. We calculated a composite exposure score across waves 1 and 2 (r = .69, p < .01) by summing the participant’s scores.

Post-traumatic stress symptoms

Children completed 9 items from the Child Post-traumatic Stress Symptoms Index (CPTSSI; Pynoos, Frederick, & Nader, 1987). The measure has been used with children in the Middle East (e.g., Wolmer, Laor, Gershon, Mayes, & Cohen, 2000). The items follow the three major DSM criteria (American Psychiatric Association, 2000) for post-traumatic stress disorder. The scale was administered immediately after the exposure to conflict and violence items, using the following instructions: “I will read to you a list of the feelings and thoughts that kids might have when they have seen or heard about very bad, scary, violent, or dangerous things like we just asked you about. Tell me how often you had these feelings and thoughts in the past month…never (0), hardly ever (1), sometimes (2), or a lot (3).” Due to time constraints, we chose 9 of the 21 CPTSSI items, three items from each of three symptom subscales: re-experiencing the event (e.g., “You have upsetting thoughts, pictures, or sounds of what happened come into your mind when you do not want them to.”); avoidance of stimuli associated with the event (e.g., “You try not to talk about, think about, or have feelings about what happened.”); and increased arousal (e.g., “When something reminds you of what happened, you have strong feelings in your body like heart beating fast, headaches, or stomach aches.”). The participant’s score reflects the mean of his or her responses to the items. Coefficient alphas ranged from .70-.91 across ethnic subgroups and time points.

Hypothesized protective factors

In line with our theorizing, we assessed four potential protective factors in each wave. For testing the role of the protective factors in moderating the effect of exposure to violence in the first two waves on PTS symptoms in the last wave, we also created for each factor a composite wave 1 - wave 2 score by averaging across the two waves.

a) Self-esteem

We used three items from the Rosenberg Global Self-esteem scale (Rosenberg, 1965). The items were: “You feel good about yourself,” “You are able to do things as well as most other people your age,” and “Most of the time, you are happy with yourself.” Children responded to each item along a 4-point scale (0 = not at all true to 3 = definitely true). Coefficient alphas ranged from .55-.81 across ethnic subgroups at wave 1 and .62-.86 at wave 2. The scale score reflects the average of the responses to the items. Scores were averaged across waves 1 and 2 (r = .28, p < .01).

b) Academic grades

Parents responded to a single item that was deemed appropriate in each region: “What kinds of grades is your child generally getting in school right now?” (1=mostly 50′s to 5=mostly 90′s). Scores were averaged across waves 1 and 2 (r = .85, p < .01).

c) Parent mental health

Parents responded to 5 items from the depression scale of the Symptom Checklist-90 (Derogatis, 1994), indicating how much each problem “has distressed or bothered you during the past seven days, including today,” along a 4-point scale ranging from 0=not at all to 4=extremely. Sample items include: “feeling lonely,” “feeling blue,” and “feeling hopeless about the future.” Coefficient alphas ranged from .76-.81 across ethnic subgroups at wave 1 and .78-.87 at wave 2. The scale score reflects the average of the responses to the five items. Scores were averaged across waves 1 and 2 (r = .54, p < .01).

d) Positive parenting

Parents responded to the 4-item index of non-violent discipline from the Conflict Tactics Scales, Parent-Child Version (Straus, Hamby, Finkelhor, Moore, & Runyan, 1998). Sample items were: “How often in the past year have you or your spouse explained why something was wrong?”; “How often in the past year have you or your spouse taken privileges away or grounded this child?” Parents responded along a 4-point scale (1=never to 4=often). The scale score reflects the average of the responses to the four items. Because of the highly skewed nature of responses, Straus et al. (1998) treat the CTS as an index rather than a scale, and calculate either a frequency score (dichotomizing each item and taking a sum) or a chronicity score (average number of times the parent engaged in each item). We calculated chronicity scores at waves 1 and 2; scores were averaged across waves 1 and 2 (r = .31, p < .01).

Because the hypothesized protective factor measures were not previously used in the Middle East, we conducted confirmatory factor analyses to assess whether these measures were invariant across time and ethnic subgroups. We computed a separate structural equation measurement model for each measure. We tested each model with the parameters constrained to be the same across ethnic group and time. The final measurement models constrained to be metrically invariant over time and ethnic group fit adequately with CFIs ranging from .92-.96 and RMSEAs ranging from .042-.057. Following Cheung and Rensvold (2002) we concluded that we had sufficient metric invariance to proceed with longitudinal analyses.

Statistical Analyses

For preliminary analyses, we present sample descriptive statistics of the major study variables by age group, sex, and ethnic subgroup. We also describe tests for non-normality and outliers, and attrition analyses. For the primary analyses, we treated missing data using the Full Information Maximum Likelihood (FIML) estimation procedure in Mplus (Version 6; Muthen & Muthen, 1998-2010). FIML assumes that missing data are “missing at random” (Allison, 2001). Data are called “missing at random” when whether an observation on a variable is missing is correlated with other observed variables measured at the same or other times but is probably not correlated with other unmeasured constructs. Parameter estimates based on FIML estimation methods will be unbiased to the extent that variables related to missingness can be included within the estimated analytic models (Graham & Donaldson, 1993); so these significant predictors of missingness were included. As a cross-check, we also conducted complete case analyses and analyses based on multiple imputation of missing data. The conclusions based on analyses using FIML estimation did not differ from those based on complete case analysis or multiply imputed missing values.2

For the primary analyses, we present zero-order correlations among the major study variables. Next, to examine the unique main effects of the predictors on wave 3 PTS, and the effects of the potential moderator variables, we computed a regression analysis using Mplus (Version 6; Muthen & Muthen, 1998-2010). To address non-normality of the data, we used robust maximum likelihood estimation (MLR option in Mplus) (see also La Greca et al., 2010).3 Following Aiken and West (1991) and Holmbeck (2002), we centered all variables entering into interaction terms. Any significant interaction effects were probed by examining simple slope regression lines of the relation between exposure to ethnic-political conflict/violence and wave 3 PTS (one for a high level of the moderator variable--1 SD above the centered mean, and one for a low level of the moderator--1 SD below the centered mean).

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Sample descriptive statistics

Table 1 shows the means and standard deviations for the major study variables by age cohort, sex, and ethnic subgroup. These effects of each of these demographic variables on the major study variables were tested with a set of 3-way analyses of variance. As expected, Palestinian youth experienced the highest levels of exposure to political conflict/ violence, followed by Israeli Jews, and then Israeli Arabs. Males and older children were exposed to higher levels of ethnic political conflict/violence. Also as expected, Palestinian youth experienced the highest levels of PTS symptoms, followed by Israeli Jews, and then Israeli Arabs; and females experienced higher levels of PTS symptoms than males.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics: Means (Standard Deviations) for Study Variables by Age, Sex, and Ethnic Group

| Age Cohort at W1 | Sex | Ethnic Group | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 8 | 11 | 14 | Females | Males | Pal | Isr-J | Isr-A | |

| Exposure to pol viol. (W1 & 2) (0 = never to 3 = many times; summed across waves = 0 – 6) |

1.40 (.86) | 1.18 (.79)a | 1.40 (.83)b | 1.64 (.88) c | 1.30 (.75)a | 1.51 (.94)b | 2.02 (.64)a | 1.21 (.65)b | .61 (.48)c |

| Post-traumatic stress (W1) Post-traumatic stress (W3) (0 = never, 3 = 5 or more times) |

1.11 (.62) .88 (.68) |

1.11 (.62) .91 (.69) |

1.13 (.60) .87 (.66) |

1.09 (.64) .84 (.69) |

1.17 (.62)a .95 (.70)a |

1.05 (.60)b .80 (.64)b |

1.39 (.60)a 1.15 (.70)a |

1.01 (.57)b .81 (.52)b |

.84 (.54)c .51 (.58)c |

| Self-esteem (W1 & 2) (0 = not true, 3 = definitely true) |

2.11 (.60) | 2.18 (.57)a | 2.11 (.61)b | 2.03 (.61)b | 2.11 (.60) | 2.12 (.59) | 1.84 (.57)c | 2.46 (.46)a | 2.24 (.55)b |

| Academic grades (W1 & 2) (1 = mostly 50s to 5 = mostly 90s) |

3.91 (1.06) | 4.26 (.93)a | 3.83 (1.06)b | 3.64 (1.09)c | 4.04 (1.02)a |

3.78 (1.09)b |

3.31(1.08)b | 4.38 (.66)a | 4.46 (.76)a |

| Parental depression (W1 & 2) (0 = not at all to 4 = extremely) |

.72 (.73) | .67 (.68) | .73 (.74) | .76 (.77) | .70 (.71) | .74 (.75) | 1.07 (.83)a | .48 (.48)b | .38 (.45)c |

| Positive parenting (W1 & 2) (1 = never to 4 = often) |

2.56 (.59) | 2.69 (.53)a | 2.58 (.59)b | 2.41 (.60)c | 2.48 (.57)b | 2.64 (.59)a | 2.60 (.53)a | 2.51 (.61)b | 2.56 (.63)ab |

Note. A 3-way (age × sex × ethnic group) ANOVA was computed for each variable; Ns range from 1238 (Post-traumatic Stress W2) to 1501 (Post-traumatic Stress W3) across analyses. Post-hoc multiple comparison (least significant differences) tests were computed between means of subgroups defined by age cohort, sex, and ethnic group. Within a comparison, means with different subscripts are significantly different at p < .05. W1 = wave 1. W 1 & 2 = waves 1 and 2 averaged. W3 = wave 3. Pal = Palestinians. Isr-J = Israeli Jews. Isr-A = Israeli Arabs.

Demographic differences also were found for the hypothesized moderator variables. Palestinian youth had the lowest levels of self-esteem and academic grades, and their parents reported the highest levels of depression and positive parenting. Younger children had the highest levels of self-esteem and academic grades, and their parents reported the highest levels of positive parenting. Females had higher academic grades than males, and parents of males reported higher levels of positive parenting compared to parents of females.

Non-normality and outliers

Univariate skewness values ranged from −.58 to 1.27, and univariate kurtosis values ranged from −.54 to 1.06. Regression diagnostics found 10 cases that exceeded cutoffs for high leverage and 28 cases that exceeded cut-offs for influential cases (Cook’s D). The major analyses were computed with and without these cases. The significance of the main and interaction effects did not change. The results reported here include these cases.

Attrition analyses

For the Palestinian sample, by wave 3, non-resampled children reported experiencing higher levels of exposure to ethnic-political conflict/violence at wave 2, t(587) = 2.72, p < .01; and parents of non-resampled children reported lower levels of positive parenting at wave 2, t(588) = 1.97, p < .05. For the Israeli Arabs, non-resampled children had higher exposure to political conflict/violence, t(448) =3.17, p < .01, higher symptoms of post-traumatic stress, t(447) = 3.05, p < .01, lower self-esteem, t(448) = 2.15, p < .05, lower academic grades, t(444) = 2.58, p < .05), and their parents reported higher levels of depression, t(448) = 4.01, p < .01. For Israeli Jews, attrition by wave 3 was associated with lower levels of average parental education at wave 1, t(449) = 3.31, p < .01, and lower academic achievement at wave 2, t(301) = 1.97, p < .05. However, despite these mean differences, none of the key study variables showed a substantial restriction in range due to attrition.

Correlations among the Major Study Variables

Table 2 shows that there was moderate continuity in PTS symptoms from wave 1 to wave 3 (r = .39, p < .01). Also, as predicted, higher levels of exposure to ethnic-political conflict/violence across waves 1 and 2 were associated with higher levels of PTS symptoms at wave 3 (r = .33, p < .01). Higher levels of self-esteem and academic grades were related to lower levels of PTS symptoms at wave 3 (rs = −.23 and −.20, p < .01, respectively), and higher levels of parent depression were related to higher levels of PTS symptoms at wave 3 (r = .19, p < .01).

Table 2.

Correlations among the Major Study Variables

| Post-traumatic stress (W 1) |

Exp. to pol. viol. (W 1 & 2) |

Self- esteem (W 1 & 2) |

Academic grades (W 1 & 2) |

Parent’s depression (W 1 & 2) |

Positive parenting (W 1 & 2) |

Post-traumatic stress (W 3) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Post-traumatic stress (W 1) | |||||||

| Exposure to political conflict/violence (W 1 & 2) | .38** | ||||||

| Self-esteem (W 1 & 2) | −.24** | −.23** | |||||

| Academic grades (W 1 & 2) | −.23** | −.43** | .32** | ||||

| Parent’s depression (W 1 & 2) | .26** | .38** | −.19** | −.31** | |||

| Positive parenting (W 1 & 2) | .05* | .07* | −.03 | −.05* | .12** | ||

| Post-traumatic stress (W 3) | .39** | .33** | −.23** | −.20** | .19** | .00 |

Note. W1 = wave 1. W 1 & 2 = waves 1 and 2 averaged. W3 = wave 3

p < .01.

p < .05.

Assessing the Longitudinal Relation between Exposure to Ethnic-Political Conflict/Violence and Subsequent PTS Symptoms and What Moderates the Relation

We computed a multiple regression analysis in Mplus that predicted wave 3 PTS symptoms from exposure to violence and the potential moderator variables (child’s self-esteem; child’s academic grades, parental depression, positive parenting) aggregated over the first two waves. Moderation was tested by examining the interaction of exposure to ethnic-political conflict/violence with each of the four hypothesized moderator variables. We also included the youth’s initial level of PTS symptoms in wave 1 as another predictor; so we would be predicting change in PTS symptoms over time. As covariates, we also included the following demographic variables (child’s sex, child’s age, average level of parents’ education, and ethnic group dummy-coded into two variables: Palestinian (1) vs. not Palestinian (0) and Israeli Arab (1) vs. not Israeli Arab (0) with Jewish (0, 0) as the reference group). (Three-way interactions of ethnic subgroup (dummy-coded) x exposure x each moderator variable were entered, but none was significant.)

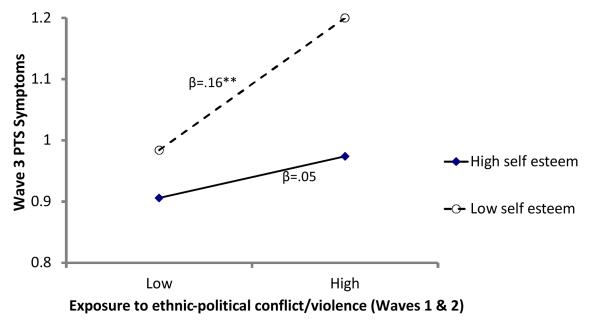

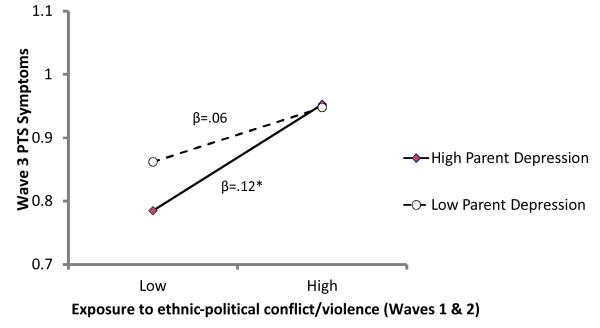

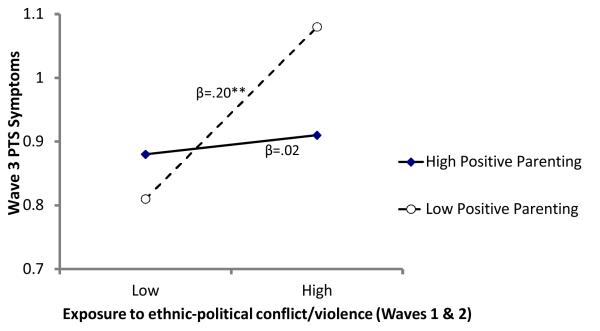

Table 3 shows that the model accounted for 26% of the variance in wave 3 PTS symptoms. There were significant main effects for wave 1 PTS symptoms (β = .23), reflecting the stability in symptoms over time. In addition, higher levels of exposure to ethnic-political violence (β = .12) and lower self-esteem (β = −.10) predicted higher levels of wave 3 PTS symptoms. There were no main effects for the other three hypothesized protective factors. Significant interactions were found for exposure to ethnic-political conflict/violence with self-esteem, parent depression, and positive parenting suggesting that each has a moderating effect over time. Figure 1 shows a risk-buffering effect for self-esteem. For youth with low self-esteem, higher levels of exposure to ethnic-political conflict/violence predicted higher levels of wave 3 PTS symptoms (β = .16). This relation was not significant for youth with high self-esteem. Figure 2 shows a risk-enhancing effect for parental depression. For youth whose parents had high levels of depression, there was a positive relation between exposure to political conflict/violence and wave 3 PTS symptoms (β = .12), but this relation was not significant for youth whose parents had low levels of depression. Figure 3 shows a risk-buffering effect for positive parenting. For youth with low levels of positive parenting, higher levels of exposure to ethnic-political conflict/violence predicted higher levels of wave 3 PTS symptoms (β = .20); this relation was not significant for youth who had high levels of positive parenting.

Table 3.

Regression Analysis Predicting Wave 3 Post-traumatic Stress Symptoms from Wave 1 Background Variables, Exposure to Ethnic-Political Conflict/Violence, and Hypothesized Protective Factors

| Predictor variables | Bd | SEe | β f |

|---|---|---|---|

| Background variables | |||

| Gendera | −.13** | .034 | −.10** |

| Age | −.02 | .008 | −.08 |

| Parents’ average education level | −.02 | .013 | −.05 |

| Ethnic dummy-code | |||

| Palestinian vs. not Palestinianb | .07 | .063 | .05 |

| Israeli Arab vs. not Israeli Arabc | −.22** | .050 | −.15** |

| Main effects | |||

| Post-traumatic stress (W 1) | .26** | .032 | .23** |

| Exposure to political conflict/violence (W 1 & 2) | .09** | .032 | .12** |

| Child’s self-esteem (W 1 & 2) | −.12** | .034 | −.10** |

| Child’s academic grades (W 1 & 2) | −.01 | .023 | −.02 |

| Parent’s depression (W 1 & 2) | −.03 | .028 | −.03 |

| Positive parenting (Waves 1 & 2) | −.03 | .032 | −.03 |

| Interactions of exposure to conflict/violence X protective factors |

|||

| Exposure X self-esteem | −.08* | .036 | −.06* |

| Exposure X academic grades | .04 | .023 | .06 |

| Exposure X parental depression | .06* | .029 | .06* |

| Exposure X positive parenting | −.13** | .035 | −.10** |

| Total R2 = .26 |

0 = female, 1 = male.

1 = Palestinian, 0 = not Palestinian.

1 = Israeli Arab, 0 = not Israeli Arab.

Unstandardized estimate.

Standard error.

Standardized estimate.

p < .01.

p < .05.

Figure 1.

Self Esteem as a Moderator of the Relation between Exposure to Ethnic-Political Conflict/Violence and Post Traumatic Stress Symptoms

Figure 2.

Parent’s Depression as a Moderator of the Relation between Exposure to Ethnic-Political Conflict/Violence and Post Traumatic Stress Symptoms

Figure 3.

Positive Parenting as a Moderator of the Relation between Exposure to Ethnic-Political Conflict/Violence and Post Traumatic Stress Symptoms

Discussion

We examined the effects of exposure to ethnic-political conflict/violence on subsequent PTS symptoms among Middle East youth. We focused on selected potential protective factors at the family- and individual-levels identified in the broader child resilience literature (e.g., Institute of Medicine, 2009, Masten et al., 1999), prior work on children’s traumatic stress reactions to non-violent traumatic events (i.e., natural disasters; LaGreca et al., 2010, 1998), and in the youth exposure to political violence literature (e.g., Qouta et al., 2005). Higher levels of exposure to ethnic-political conflict/violence predicted higher levels of later PTS symptoms, controlling for initial symptoms and several demographic variables. We also found protective effects for positive parenting and youth self-esteem.

Exposure to Ethnic-Political Conflict/Violence and PTS Symptoms: Descriptive Findings

Older youth, males, and as expected, Palestinian children were exposed to the highest levels of ethnic-political conflict/violence. The findings that older youth and males were exposed to higher levels of ethnic-political violence also have been reported by others (e.g., Barber & Olsen, 2009; Thabet & Vostanis, 2000) and may reflect an increase in autonomy and mobility associated with the transition to adolescence that should place older youth, especially males, into contexts where they would have greater opportunity for exposure, which may include activism and involvement in the conflict (e.g., demonstrating, distributing leaflets, protecting someone from soldiers, throwing stones) (Barber & Olsen, 2009).

Results also showed differences in exposure and PTS symptoms linked to region (Israel, Palestine) and ethnic group within region (Israeli Jews, Israeli Arabs). In particular, based on our expectation that they would have the greatest exposure to violence, Palestinian youth also displayed the highest levels of PTS symptoms. Indeed, in terms of violence exposure, during the Second Intifada, Palestinian casualties have far outnumbered Israeli casualties (B’Tselem, Israeli Information Center for Human Rights in the Occupied Territories). Within Israel, Jewish youth were exposed to higher levels of ethnic-political conflict/violence than Arab youth and also reported higher levels of PTS symptoms compared to Arab youth. The ethnic-political conflict in Israel is most clearly focused between the Palestinians and Israeli Jews, most likely accounting for the higher level of violence exposure, and perhaps resulting in higher levels of PTS symptoms, among Israeli Jews than Israeli Arabs.

Exposure to Ethnic-Political Conflict/Violence, Protective Effects, and PTS Symptoms

Barber and Schluterman’s (2009) review of the 95 empirical studies on the effects on youth of political violence exposure found that 43% of the studies used measures of PTS, and nearly all reported a positive relation between exposure and PTS. Our study is unique in its longitudinal design: exposure is related to subsequent PTS symptoms, regardless of the level of prior symptoms the child had experienced; and this finding held even after statistically controlling for age, gender, ethnic subgroup, parental educational level, self-esteem, academic achievement, parental depression, and parental positive parenting.

At the family level, positive parenting (e.g., non-physical strategies such as explaining why something was wrong, removing privileges, rewarding/praising for doing something right) served as a protective factor for children exposed to political violence probably by helping them to cope more effectively. This finding is consistent with those of extant cross-sectional studies (e.g., Barber, 1999; Garbarino & Kostelny, 1996; Laor et al., 2001; Punamäki et al., 1997; Qouta, Punamaki, Miller, & El; Sarraj, 2008). Punamaki (2009) noted that, “family can provide children with protection, consolation, and fortitude to endure dangerous and violent conditions” (p. 69). Very likely, even under conditions of high risk, children who experience positive parenting might develop feelings of security within the parent-child relationship, which in turn should be associated with more positive adjustment and coping (Cummings et al., 2010). Also consistent with other studies in the Middle East (e.g., Thabet et al., 2008; Qouta et al., 2005), parental adjustment was related to children’s symptoms. Specifically, for youth whose parents had higher levels of depressive symptoms, there was a positive relation between violence exposure and PTS symptoms.

At the individual level, youth with higher levels of self-esteem were less likely than those with lower levels of self-esteem to experience PTS symptoms when exposed to higher levels of ethnic-political conflict/violence. Following Kliewer and Sandler (1992) and Qouta et al. (2008), it is possible that children with higher levels of self-esteem cope more effectively with traumatic events. Based on the “Responses to Stress Model” of coping (Connor-Smith et al., 2000), youth with higher levels of self-esteem might more effectively match their coping strategies to the demands of uncontrollable and persistent stressors and utilize coping strategies such as disengagement (i.e., responses directed away from a stressor, e.g., distraction through seeking social support) and secondary control coping strategies (i.e., responses focused on adaptation to the problem, e.g., acceptance, cognitive restructuring). But studies have found mixed evidence for coping as a stress-buffering resource (see Grant et al., 2006). For example, LaGreca et al. (1996) found that both positive and negative coping strategies predicted higher levels of PTS symptoms 7 months post-hurricane exposure, and only negative coping (blame and anger) predicted PTS symptoms 10 months post-hurricane exposure. Dubow and Rubinlicht (2011) noted that coping is “a dynamic process that involves flexibility in strategies across the coping process, depending on the current demands of the situation.” Very likely, those individuals experiencing more distress utilize several types of coping strategies, both positive and negative, so coping and PTS may be positively related. To best assess coping with a given stressor, multiple, closely spaced measurements might be the most fruitful approach. We also note that the protective effect for self-esteem might reflect the moderate overlap between self-esteem and depression (e.g., Overholser, Adams, Lehnert, & Brinkman, 1995); that is, the result might reflect the possibility that lack of depression is the protective factor.

Children who had higher levels of academic achievement exhibited fewer PTS symptoms, but academic achievement lost its predictive ability once other variables also were included as predictors. This is probably a consequence of the fact that academic achievement is significantly correlated with two other moderators in the equation -- positively with self-esteem and negatively with parental depression. Thus the variance that could be explained by academic achievement when it is a lone predictor may have been explained by self-esteem and parental depression in the combined prediction. It is also possible that our measure of academic achievement (assessed through a single parent-report item) was not a sufficient assessment.

Limitations and Implications

We note a few limitations of the current study. Like many studies of Middle East youth, ours focused primarily on exposure to violence via witnessing rather than direct victimization. Among Palestinian children, Qouta et al. (2008) found moderate correlations between witnessing and being the victim of military violence, and both were positively related to aggression. Future studies should assess differential effects of these different modes of exposure to political violence, as well as different types of exposure (e.g., material loss, separations, threat to loved ones, harm to loved ones, traumatic bereavement, direct exposure, witnessing violence; see Layne et al., 2010, for scale development analyses of a 49-item war-trauma measure).

Second, because exposure to political conflict/violence is common throughout Palestine, we could afford to obtain a representative sample of that entire population. However, for the Israelis (Jews and Arabs), although most live in the large cities of Jerusalem and Tel Aviv, those areas are generally in low conflict areas, so a representative sample would not have allowed us to obtain sufficient numbers who were exposed to persistent conflict/violence. Consequently, our regional colleagues designed a sampling procedure to oversample high exposure areas to insure adequate representation of exposure to ethnic-political conflict and violence. Thus, the Israeli sample is not representative of the total Israeli population, so our results are not as generalizable to the Israeli population as our results for Palestine are generalizable to the Palestine population.

Third, due to time limitations in our interviews, we could examine only four protective factors (two family- and two individual-level variables). Though from a theoretical perspective we believe these are important potential moderators that needed to be investigated, Barber and Schluterman (2009) noted that other potential protective factors in the individual domain may be important for war-exposed youth (e.g., religious and ideological commitment, coping strategies). Also, we did not assess potential protective factors from the extra-familial domain (e.g., peer social support, civic engagement, extracurricular/recreational activity involvement), and we did not assess stressful life events related to the political conflict (e.g., loss of daily necessities), which exert negative effects on youth’s adjustment (Miller & Rasmussen, 2010).

Fourth, several of our measures were abbreviated versions of existing measures. Based on our local collaborators’ experience, we limited our home-based interviews to one hour, and adapted measures for this purpose. This is perhaps a trade-off in carrying out field-based research in high-risk regions. More work needs to be done to develop highly reliable and valid measures for this type of research.

Implications for Research, Practice, and Policy

Despite these limitations, the present study makes a unique contribution to the growing literature on the deleterious effects of exposure to persistent ethnic-political violence on children. Our study included three age cohorts from three ethnic groups in the Middle East. The prospective design allowed us to show that exposure to ethnic-political conflict/violence increases risk for subsequent PTS symptoms, while controlling for children’s earlier levels of symptoms. Our design also allowed us to show that this longitudinal effect of exposure to violence on PTS symptoms is diminished for children with higher self-esteem, with parents who engage in positive parenting, and with parents who are not depressed. These findings regarding protective factors that might promote resilience for youth exposed to persistent conflict/violence underscore the importance of examining whether targeting these factors in preventive interventions reduces distress among war-exposed youth. The results support calls by researchers for the development of multi-level interventions for individuals exposed to war trauma (see DeJong, 2010). As Peltonen and Punamäki (2010) observed, most published intervention studies for war-exposed youth report mixed results from programs primarily targeting children’s cognitive processes. Yet, those authors conclude that it will be critical for applied researchers and clinicians to implement and evaluate the effects of more holistic, multi-level interventions for this population. This recommendation is supported by our findings, as well as the more general prevention-intervention literature emphasizing the importance of programs that involve multiple levels of children’s social ecologies in preventing the development of psychopathology (e.g., Greenberg, Domitrovich, & Bumbarger, 2001).

Footnotes

Parents of children in the 8 year-old cohort provided reports of their children’s exposure to ethnic-political conflict in each wave, but children in the older cohorts (11 and 14 year-olds in wave 1) provided self-reports. We followed this strategy because our Institutional Review Board had concerns about the 8 year-olds’ emotional reactions to reporting on their own exposure. Also, given time constraints on interviews with young children, having parents report on these items decreased the length of the interview for 8 year-olds. To examine the comparability of children’s and parents’ reports of children’s exposure to political conflict/violence, we administered the measures to both children and parents of the youngest cohort in wave 3 and found them to be highly correlated (r = .68).

Following La Greca et al. (2010), as an alternative to FIML to estimate missing data, we replicated the correlation and regression analyses using a multiple imputation procedure in Mplus, generating 10 imputed data sets. This procedure did not affect the significance of the correlations or the regression results.

As an alternative approach to dealing with non-normality, we used the bootstrapping procedure in AMOS, requesting 200 bootstrapped samples and bias-corrected confidence intervals for each of the parameter bootstrap estimates. This procedure did not affect the conclusions based on the robust maximum likelihood estimation results.

References

- Abdeen Z, Qaswari R, Nabil S, Shaheen M. Psychological reactions to Israeli occupation: Findings from the national study of school-based screening in Palestine. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2008;32:290–297. [Google Scholar]

- Aiken LA, West SG. Testing and interpreting interactions in multiple regressions. Sage; Newbury Park, CA: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Allison PD. Missing data. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. Fourth edition: Text revision Author; Washington, D.C.: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Barber BK. Political violence, family relations, and Palestinian youth functioning. Journal of Adolescent Research. 1999;14:206–230. [Google Scholar]

- Barber BK, editor. Adolescents and war: How youth deal with political violence. Oxford University Press; NY: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Barber BK, Schluterman JM. An overview of the empirical literature on adolescents and political violence. In: Barber BK, editor. Adolescents and war: How youth deal with political violence. Oxford University Press; NY: 2009. pp. 35–61. [Google Scholar]

- Betancourt TS, Borisova II, Williams TP, Brennan RT, Whitfield TH, De La Soudiere M, Williamson J, Gilman SE. Sierra Leone’s former child soldiers: A follow-up study of psychosocial adjustment and community reintegration. Child Development. 2010;81:1077–1095. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01455.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boxer P, Huesmann LR, Dubow EF, Landau S, Gvirsman S, Shikaki K, Ginges J. Exposure to violence across the social ecosystem and the development of aggression: A test of ecological theory in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Child Development. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01848.x. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [Accessed in May, 2009];B’Tselem: Israeli Information Center for Human Rights in the Occupied Territories. 2009 at http://www.btselem.org//english/statistics/casualties.asp.

- Cairns E, Dawes A. Children: Ethnic and political violence – a commentary. Child Development. 1996;67:129–139. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1996.tb01715.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung GW, Rensvold RB. Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling. 2002;9:233–255. [Google Scholar]

- Connor-Smith JK, Compas BE, Wadsworth ME, Thomsen AH, Saltzman H. Responses to stress in adolescence: Measurement of coping and involuntary responses to stress. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:976–992. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowen EL, Wyman PA, Work W, Parker GM. The Rochester Child Resilience Study: Overview and summary of first year findings. Development and Psychopathology. 1990;2:193–212. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Schermerhorn AC, Merrilees CE, Goeke-Morey MC, Shirlow P, Cairns E. Political violence and child adjustment in Northern Ireland: Testing pathways in a social-ecological model including single- and two-parent families. Developmental Psychology. 2010a;46:827–841. doi: 10.1037/a0019668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Merrilees CE, Schermerhorn AC, Goecke-Morey MC, Shirlow P, Cairns E. Testing a social ecological model for relations between political violence and child adjustment in Northern Ireland. Development and Psychopathology. 2010b;22:405–418. doi: 10.1017/S0954579410000143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeJong JTVM. A public health framework to translate risk factors related to political violence and war into multi-level preventive interventions. Social Science & Medicine. 2010;70:71–79. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.09.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Jong JTVM, Komproe IH, Van Ommeren M, El Masri M, Araya M, Khaled N, van de Put W, Somasundaram D. Lifetime events and posttraumatic stressdisorder in 4 postconflict settings. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2001;286:555–562. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.5.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis LR. Symptom Checklist-90-R (SCL-90-R): Administration, scoring and procedures manual. 3rd Ed National Computer Systems; Minneapolis, MN: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Dubow EF, Boxer LR, Huesmann LR, Shikaki K, Landau S, Gvirsman S, Ginges J. Exposure to conflict and violence across contexts: Relations to adjustment among Palestinian children. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2010;39:103–116. doi: 10.1080/15374410903401153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubow EF, Huesmann LR, Boxer P. A social-cognitive-ecological framework for understanding the impact of exposure to persistent ethnic-political violence on children’s psychosocial adjustment. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2009;12:113–126. doi: 10.1007/s10567-009-0050-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubow EF, Rubinlicht M, Brown BB, Prinstein MJ, editors. Encyclopedia of adolescence. Vol. 3. Academic Press; San Diego: 2011. Coping; pp. 109–118. [Google Scholar]

- Garbarino J, Kostelny K. The effects of political violence on Palestinian children’s behavior problems: A risk accumulation model. Child Development. 1996;67:33–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garbarino J, Kostelny K, Dubrow N. What children can tell us about living in danger. American Psychologist. 1991;46:376–383. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.46.4.376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garmezy N, Neuchterlein K. Invulnerable children: The fact and fiction of competence and disadvantage. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1972;42:328–329. [Google Scholar]

- Graham JW, Donaldson SI. Evaluating interventions with differential attrition: The importance of nonreponse mechanisms and use of follow-up data. Journal of Applied Psychology. 1993;78:119–128. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.78.1.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant KE, Compas BE, Thurm AE, McMahon SD, Gipson PY, Campbell AJ, Krochock K, Westerholm RI. Stressors and child and adolescent psychopathology: Evidence of moderating and mediating effects. Clinical Psychology Review. 2006;26:257–283. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg MT, Domitrovich C, Bumbarger B. The prevention of mental disorders in school-aged children: Current state of the field. Prevention & Treatment. 2001 Mar;4(1) [np]. doi: 10.1037/1522-3736.4.1.41a. [Google Scholar]

- Hallis D, Slone M. Coping strategies and locus of control as mediating variables in the relation between exposure to political life events and psychological adjustment in Israeli children. International Journal of Stress Management. 1999;6:105–123. [Google Scholar]

- Holmbeck GN. Post-hoc probing of significant moderational and meditational effects in studies of pediatric populations. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2002;27:87–96. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/27.1.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine . Preventing mental, emotional, and behavioral disorders among young people: Progress and possibilities. The National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kithakye M, Morris AS, Terranova AM, Myers SS. The Kenyan political conflict and children’s adjustment. Child Development. 2010;81:1114–1128. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01457.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klasen F, Oettingen G, Daniels J, Post M, Hoyer C, Adam H. Posttraumatic resilience in former Ugandan child soldiers. Child Development. 2010;81:1096–1113. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01456.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kliewer W, Sandler IH. Locus of control and self-esteem as moderators of stress-symptom relations in children and adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1992;20:393–411. doi: 10.1007/BF00918984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaGreca AM, Silverman WK, Lai B, Jaccard J. Hurricane-related exposure experiences and stressors, other life events, and social support: Concurrent and prospective impact on children’s persistent posttraumatic stress symptoms. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2010;78:794–805. doi: 10.1037/a0020775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Greca AM, Silverman WK, Vernberg EM, Prinstein MJ. Symptoms of posttraumatic stress in children after Hurricane Andrew: A prospective study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1996;64:712–723. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.4.712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Greca AM, Silverman WK, Wasserstein SB. Children’s predisaster functioning as a predictor of posttraumatic stress following Hurricane Andrew. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66:883–892. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.6.883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landau SF, Gvirsman SD, Huesmann LR, Dubow EF, Boxer P, Ginges J, Shikaki K. The effects of exposure to violence on aggressive behavior: The case of Arab and Jewish children in Israel. In: Österman K, editor. Indirect and Direct Aggression. Peter Lang; Berlin, Germany: 2010. pp. 321–343. [Google Scholar]

- Laor N, Wolmer L, Cohen DJ. Mothers’ functioning and children’s symptoms 5 years after a SCUD missile attack. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;158:1020–1026. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.7.1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavi T, Solomon Z. Palestinian youth of the Intifada: PTSD and future orientation. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2005;44:1176–1183. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000177325.47629.4c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Layne CM, Olsen JA, Baker A, Legerski J, Isakson B, Pašalić A, Duraković-Belko E, D̄apo N, Ćampara N, Arslanagić B, Saltzman WR, Pynoos RS. Unpacking trauma exposure risk factors and differential pathways of influence: Predicting post-war mental distress in Bosnian adolescents. Child Development. 2010;81:1053–1076. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01454.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luthar S, Cicchetti D, Becker B. The construct of resilience: A critical evaluation and guidelines for future work. Child Development. 2000;71:543–562. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney A, Donnelly WO, Boxer P, Lewis T. Marital and severe parent-to-adolescent physical aggression in clinic-referred families: Mother and adolescent reports on co-occurrence and links to child behavior problems. Journal of Family Psychology. 2003;17:3–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS, Best KM, Garmezy N. Resilience and development: Contributions from the study of children who overcome adversity. Development and Psychopathology. 1990;2:425–444. [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS, Hubbard JL, Gest SD, Tellegen A, Garmezy N, Ramirez M. Competence in the context of adversity: Pathways to resilience and maladaptation from childhood to late adolescence. Development and Psychopathology. 1999;11:143–169. doi: 10.1017/s0954579499001996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller KE, Rasmussen A. War exposure, daily stressors, and mental health in conflict and post-conflict settings: Bridging the divide between trauma-focused and psychosocial frameworks. Social Science & Medicine. 2010;70:7–16. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User’s Guide. Sixth Edition Muthén & Muthén; Los Angeles, CA: 1998-2010. [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors B, Forehand R, McVicar D. Resilient adolescents and interparental conflict. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1993;63:462–471. doi: 10.1037/h0079442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overholser JC, Adams DM, Lehnert KL, Brinkman DC. Self-esteem deficits and suicidal tendencies among adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1995;34:919–929. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199507000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics . Census final results in the West Bank: Summary (Population and Housing) Ramallah; Author: [Retrieved November 11, 2008]. Aug, 2008. from http://www.pcbs.gov.ps/Portals/_PCBS/Downloads/book1487.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Peltonen K, Punamäki R. Preventive interventions among children exposed to trauma of armed conflict: A literature review. Aggressive Behavior. 2010;36:95–116. doi: 10.1002/ab.20334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prinstein MJ, La Greca AM, Vernberg EM, Silverman WK. Children’s coping assistance: How parents, teachers, and friends help children cope after a natural disaster. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1996;25:463–475. [Google Scholar]

- Punamäki R, Qouta S, El Sarraj E. Resiliency factors predicting adjustment after political violence among Palestinian children. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 1997;25:256–267. [Google Scholar]

- Punamäki R, Qouta S, El Sarraj E. Resiliency factors predicting psychological adjustment after political violence among Palestinian children. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2001;25:256–267. [Google Scholar]

- Pynoos RS, Frederick C, Nader K. Life threat and post-traumatic stress in school age children. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1987;37:629–636. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1987.01800240031005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qouta S, Punamaki R, El Sarraj E. Prevalence and determinants of PTSD among Palestinian children exposed to military violence. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2003;12:265–272. doi: 10.1007/s00787-003-0328-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qouta S, Punamaki RL, El Sarraj E. Mother-child expression of psychological distress in acute war trauma. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2005;10:135–156. [Google Scholar]

- Qouta S, Punamäki RL, Miller T, El Sarraj E. Does war beget child aggression? Military violence, gender, age, and aggressive behavior in two Palestinian samples. Aggressive Behavior. 2008;34:231–244. doi: 10.1002/ab.20236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qouta S, Punamäki RL, El Sarraj E. Child development and mental health in war and military violence: The Palestinian experience. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2008;32:310–321. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg M. Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton University Press; Princeton, N.J.: 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Rowe CL, La Greca AM, Alexandersson A. Family and Individual factors associated with substance involvement and PTS symptoms among adolescents in Greater New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina. Journal of Clinical and Consulting Psychology. 2010;78:806–817. doi: 10.1037/a0020808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M. Psychosocial resilience and protective mechanisms. In: Rolf J, Masten AS, Cicchetti D, Nuechterlein KH, Weintraub S, editors. Risk and protective factors in the development of psychopathology. Cambridge University Press; New York: 1990. pp. 181–214. [Google Scholar]

- Sagi-Schwartz A. The well-being of children living in chronic war zones: The Palestinian-Israeli case. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2008;32:322–336. [Google Scholar]

- Salzinger S, Feldman RS, Rosario M, Ng-Mak DS. Role of parent and peer relationships and individual characteristics in middle school children’s behavioral outcomes in the face of community violence. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2010;21:395–407. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00677.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandler I. Quality and ecology of adversity as common mechanisms of risk and resilience. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2001;29:19–61. doi: 10.1023/A:1005237110505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandler IN, Miller P, Short J, Wolchik S. Social support as a protective factor for children in stress. In: Belle D, editor. Children’s social networks and social supports. Wiley; NY: 1989. pp. 277–307. [Google Scholar]

- Scaramella LV, Sohr-Preston SL, Callahan KL, Mirabile SP. A test of the family stress model on toddler-aged children’s adjustment among Hurricane Katrina impacted and non-impacted low-income families. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2008;37:530–541. doi: 10.1080/15374410802148202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheeringa MS, Zeanah CH. Reconsideration of harm’s way: Onset and comorbidity patterns of disorders in preschool children and their caregivers following Hurricane Katrina. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2008;37:508–518. doi: 10.1080/15374410802148178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seginer R. Future orientation in times of threat and challenge: How resilient adolescents construct their future. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2008;32:272–282. [Google Scholar]

- Slone M. Growing up in Israel: Lessons on understanding the effects of political violence on children. In: Barber BK, editor. Adolescents and war: How youth deal with political violence. Oxford University Press; NY: 2009. pp. 81–104. [Google Scholar]

- Slone M, Lobel T, Gilat I. Dimensions of the political environment affecting children’s mental health. Journal of Conflict Resolution. 1999;43:78–91. [Google Scholar]

- Spell AW, Kelly ML, Wang J, Self-Brown S, Davidson KL, Pellegrin A, Palcic JL, Meyer K, Paasch V, Baumeister A. The moderating effects of maternal psychopathology on children’s adjustment post-Hurricane Katrina. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2008;37:553–563. doi: 10.1080/15374410802148210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Hamby SL, Finkelhor D, Moore DW, Runyan D. Identification of child maltreatment with the Parent-Child Conflict Tactics Scales: Development and psychometric data for a national sample of American parents. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1998;22:249–270. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(97)00174-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terranova AM, Boxer P, Morris AS. Factors influencing the course of posttraumatic stress following a natural disaster: Children’s reactions to Hurricane Katrina. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2009;30:344–355. [Google Scholar]

- Thabet AA, Ibrahim AN, Shivram R, Winter E,W, Vostanis P. Parenting support and PTSD in children of a war zone. International Journal of Social Psychiatry. 2009;55:226–237. doi: 10.1177/0020764008096100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thabet AA, Tawahina AA, El Sarraj E, Vostanis P. Exposure to war trauma and PTSD among parents and children in the Gaza strip. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2008;17:191–199. doi: 10.1007/s00787-007-0653-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thabet AA, Vostanis P. Post-traumatic stress disorder reactions in children of war: A longitudinal study. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2000;24:291–298. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(99)00127-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vernberg EM, La Greca AM, Silverman WK, Prinstein M. Predictors of children’s post-disaster functioning following hurricane Andrew. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1996;105:237–248. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.105.2.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Victoroff J, Qouta S, Adelman JR, Celinska B, Stern N, Wilcox R, Sapolsky RM. Support for religio-political aggression among teenaged boys in Gaza: Part I: Psychological findings. Aggressive Behavior. 2010;36:219–231. doi: 10.1002/ab.20348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weems CF, Overstreet S. An ecological-needs-based perspective of adolescent and youth emotional development in the context of disaster: Lessons from Hurricane Katrina. In: Cherry KE, editor. Lifespan perspectives on natural disasters. Springer; NY: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Weems CF, Pina AA, Costa NM, Watts SE, Taylor LK, Cannon MF. Pre-disaster trait anxiety and negative affect predict posttraumatic stress in youth after Hurricane Katrina. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75:154–159. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.1.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]