Abstract

The cochlear spiral ligament is a connective tissue that plays diverse roles in normal hearing. Spiral ligament fibrocytes are classified into functional sub-types that are proposed to carry out specialized roles in fluid homeostasis, the mediation of inflammatory responses to trauma, and the fine tuning of cochlear mechanics. We derived a secondary sub-culture from guinea pig spiral ligament, in which the cells expressed protein markers of type III or “tension” fibrocytes, including non-muscle myosin II (nmII), α-smooth muscle actin (αsma), vimentin, connexin43 (cx43), and aquaporin-1. The cells formed extensive stress fibers containing αsma, which were also associated intimately with nmII expression, and the cells displayed the mechanically contractile phenotype predicted by earlier modeling studies. cx43 immunofluorescence was evident within intercellular plaques, and the cells were coupled via dye-permeable gap junctions. Coupling was blocked by meclofenamic acid (MFA), an inhibitor of cx43-containing channels. The contraction of collagen lattice gels mediated by the cells could be prevented reversibly by blebbistatin, an inhibitor of nmII function. MFA also reduced the gel contraction, suggesting that intercellular coupling modulates contractility. The results demonstrate that these cells can impart nmII-dependent contractile force on a collagenous substrate, and support the hypothesis that type III fibrocytes regulate tension in the spiral ligament-basilar membrane complex, thereby determining auditory sensitivity.

Keywords: actin, aquaporin, basilar membrane, connexin, myosin, stria vascularis

Introduction

Non-muscle myosin II (nmII) is an ATP-driven molecular motor that plays diverse roles in cell physiology. Through its association with actin filaments, nmII regulates cellular reshaping and movement, and so regulates cell migration, adhesion, polarity, and cytokinesis (Vicente-Manzanares et al. 2009). In this study, we have examined the contribution of nmII to the physiology of type III fibrocytes, which have been proposed to regulate the tension of the basilar membrane in the cochlea (Henson et al. 1984; Kuhn and Vater 1997; Naidu and Mountain 2007). The micromechanics of this collagenous structure are responsible for the sharp frequency tuning of mammalian hearing, and thus the transfer of mechanical sound stimuli into a meaningful electrical code.

Mechano-electrical transduction of auditory signals within the cochlea relies on both the highly positive endocochlear potential within scala media, and the maintenance of high endolymphatic [K+]. These mechanisms are both dependent on the function of stria vascularis, the ion-pumping epithelial body of the cochlea. Strial physiology is supported by the homeostatic function of the spiral ligament, a connective tissue lining the space between stria vascularis and the bony otic capsule. The ligament is composed of sub-populations of specialized fibrocytes, which are proposed to play distinct roles predicted by their protein expression profiles (Spicer and Schulte 1991, 1996). Certain fibrocyte sub-types express ion transport proteins, and so are likely to regulate [K+] and [Cl−] within the lateral wall perilymph (Wangemann 2006). The fibrocytes are also thought to be involved in the cochlea’s inflammatory response to trauma caused by noise, disease, and ageing (Hequembourg and Liberman 2001; Ohlemiller 2009).

Type I fibrocytes lie to the rear of stria vascularis, and are coupled to strial basal cells via gap junctions containing connexin26 (cx26) and cx30 subunits (Forge et al. 2003; Liu and Zhao 2008). They are connected via comparable gap junctions to type II fibrocytes located inferiorly to stria vascularis and behind the spiral prominence, and to type V fibrocytes located superiorly to stria vascularis. Together, these sub-types form the “connective tissue gap junction network.” This syncytium is presumed to form the basis of a K+ recirculation pathway, and has a cytoplasmic connection to intermediate cells in stria vascularis (Kelly et al. 2011). Type IV fibrocytes lie inferiorly to type II fibrocytes, but do not express cx26/cx30-containing channels (Adams 2009) and so are not thought to be coupled to the recirculation pathway. However, they may play essential roles in perilymphatic Cl− transport (Qu et al. 2007).

Type III fibrocytes line the space between types I and II fibrocytes and the bony otic capsule, and are most prevalent in the most basal (high-frequency coding) region of the cochlea. They appear not to be connected cytoplasmically to the connective tissue gap junction network (Kelly et al. 2011) but may form a separately coupled compartment via cx43-containing channels (Forge et al. 2003). Based solely on their extensive expression of contractile cytoskeletal elements, including nmII and bundles of actin filaments, they have also been termed “tension fibrocytes” (Henson et al. 1984; Henson et al. 1985; Henson and Henson 1988), and have been proposed to regulate the micromechanics of the spiral ligament-basilar membrane complex (Naidu and Mountain 2007). However, due to their inaccessibility in vivo there is little, if any, direct experimental evidence to support this hypothesis.

In the present study, we have taken an alternative approach, studying the properties of type III fibrocytes in vitro. Cells were sub-cultured from the basal region of spiral ligament from guinea pig cochlea, and classified as type III fibrocytes based on previous criteria (Henson et al. 1985; Gratton et al. 1996). They expressed specific protein markers found in type III fibrocytes in vivo, including aquaporin-1, α-smooth muscle actin, vimentin, cx43, and nmII. Within a collagen substrate the cells were capable of generating an acto-myosin dependent contractility, which appeared to be modulated by gap junctional coupling. These results provide functional support for the hypothetical role of type III fibrocytes in setting basilar membrane tension, and point to the contractile properties of nmII as a key determinant of auditory sensitivity.

Methods

Tissue culture

Young pigmented guinea pigs (150–250 g) were killed by CO2 inhalation, in accordance with the UK Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act of 1986 and the UCL Animal Ethics Committee. Cochleae were removed under sterile conditions, and transferred to ice cold Hanks Balanced Salt Solution supplemented with HEPES. All chemicals were obtained from Sigma unless stated. Dissections were performed under sterile conditions. The cochlear bone was opened using a scalpel blade, and the spiral ligament dissected out with fine forceps. The ligament from the basal turn region of the cochlea was cut into two to three longitudinal segments and placed onto collagen type-I coated 35 mm Petri dishes. To facilitate attachment a minimal amount of fibrocyte culture medium (MEM-α, supplemented with 10 % fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1 % insulin-transferrin-selenium 1 % penicillin/streptomycin/glutamine, and 0.5 % amphotericin B (Fungizone™; Invitrogen, Paisley, UK)) was dropped onto the tissue segments. Further medium was added to each well and incubated at 37°C in a 5 % CO2, 95 % air atmosphere, with fresh medium changed every 3 days. After ∼4 days in culture fibrocyte migration from tissue explants was visible. Full confluency was reached after 2–3 weeks, at which point the cells were sub-cultured. The cells were rinsed in sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and incubated with ×1 trypsin/EDTA for 5 min at 37°C to induce cell detachment. Culture medium with FBS was added to terminate the trypsin activity and cells were suspended through gentle trituration. The cell suspension was added to a 25 cm2 cell culture flask (BD Bioscience, Oxford, UK) and the total volume made up to 5 ml with culture medium. The cells were grown to near confluency before being split 1:1 into a larger 75-cm2 flask. Fresh medium was changed every 3 days and cells split 1:10 once a week or when fully confluent.

Confocal immunofluorescence

Cells grown on glass coverslips were fixed using 4 % paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS, for 30 min at room temperature. Following several PBS washes, cells were permeabilized and blocked (0.1 % Triton-X 100 with 10 % normal goat serum in PBS) for 30 min at room temperature, and then incubated in primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. Vibratome sections of fixed cochlear tissues were prepared and treated as described elsewhere (Jagger et al. 2010). The primary antibodies were used at the following final concentrations: mouse monoclonal anti-acetylated tubulin (Sigma) 1:1,000; rabbit polyclonal anti-myosin II (non-muscle; Sigma) 1:800; rabbit polyclonal anti-aquaporin-1 (Sigma) 1:400; mouse monoclonal anti-α-smooth muscle actin (Sigma) 1:200; mouse monoclonal anti-vimentin (Sigma) 1:800; rabbit polyclonal anti-cx43 (Sigma) 1:400; mouse monoclonal anti-GM130 (BD Bioscience) 1:400; rabbit polyclonal anti-cx31 (a gift from D. Kelsell, Queen Mary University of London) (Di et al. 2001) 1:200; rabbit polyclonal anti-cx26 (a gift from W.H. Evans, University of Cardiff) (Forge et al. 2003) 1:200; rabbit polyclonal anti-cx30 (Zymed) 1:200. In control experiments primary antibodies were omitted. Following several PBS washes cells were incubated in Alexa–Fluor tagged secondary antibodies (Invitrogen) in the dark for 30 min at room temperature. Actin was stained with tetramethyl-rhodamine (TRITC) phalloidin (Sigma). Coverslips were mounted on glass slides using Vectashield with diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; Vector Laboratories, Peterborough, UK). Imaging was carried out using a laser scanning confocal microscope (LSM510; Carl Zeiss MicroImaging, Jena, Germany) as described elsewhere (Jagger and Forge 2006; Taylor et al. 2012).

Reverse Transcription-PCR analysis of connexin expression

Total RNA was isolated from fibrocytes grown to confluency in a 25-cm2 cell culture flask and from adult guinea-pig cochlea, brain, and liver (positive controls) using the RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen, Crawley, UK) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Reverse-transcribed cDNAs were generated from 1 μg of template RNA using the Omniscript RT kit (Qiagen) with oligo-dT primers (Roche, Burgess Hill, UK). Negative controls were performed by omitting the reverse transcriptase in the RT reaction. All PCR reactions were performed with a Mastercycler Gradient (Eppendorf, Histon, UK). Primers were designed from guinea-pig coding sequences for cx26 (gcx26), gcx31, and gcx43 using the Primer3 program (http://frodo.wi.mit.edu/primer3) and were purchased from Sigma. The guinea-pig cx30 coding sequence has not been published, so primers were used for detecting mouse cx30 (Forge et al. 2003). Positive controls using guinea-pig tissues showed amplification of the correct band size, thus confirming suitability of mouse cx30 primers for PCR reactions. Alignments were performed on each set of primers to exclude cross-reactivity. Details of the forward and reverse primers are shown in Table 1. PCR was performed using the Taq DNA polymerase kit (Qiagen). Briefly, 0.5– 1 μg template DNA, 200 μM of each dNTP, 0.2 μM of each primer, 1× PCR buffer, 3 mM MgCl2, and 2.5U of Taq DNA polymerase made up in nuclease-free H2O was used per reaction. Template DNA was replaced with nuclease-free H2O for negative controls. Thermal cycling was performed under the following conditions: initial denaturation at 94°C for 3 min, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 30 s, annealing at 65°C (60°C for gcx26 primers) for 60 s, extension at 72°C for 60 s and a final extension at 72°C for 10 min at the end of cycling. PCR products were electrophoresed along with a 100-bp DNA ladder (New England Biolabs, Hitchen, UK) on a 2 % agarose gel containing 0.5 μg/ml ethidium bromide for 40 min at 90 mV. DNA bands were visualized under UV light on a Jencons-PLC UVP GelDoc-It imaging system.

TABLE 1.

Primers used in RT-PCR experiments

| Primer | Oligonucleotide sequence | Product size (base pairs) | Accession no. |

|---|---|---|---|

| gcx26 | F: ACCGGAAGCATGAGAAGAAA | 226 | AB089440.1 |

| R: CAAGCATTGCATTTCACCAG | |||

| mcx30 | F: AGGAAGTGTGGGGTGATGAG | 517 | NM_008128.3 |

| R: AGGTAACACAACTCGGCCAC | |||

| gcx31 | F: TATACGTGGTGGCTGCAGAG | 232 | ENSCPOT00000010722a |

| R: TGCTCACCGTACTTCTGACG | |||

| gcx43 | F: AGGAGGAGCTCAAGGTAGCC | 164 | AY700675 |

| R: GACCGACTTGAAGAGGATGC |

F forward, R reverse, g guinea pig, m mouse

aSequence obtained from Ensemble; guinea pig release, 50 (July 2008)

Whole-cell dye injection

Coverslips were washed with artificial perilymph (in mM: 140 NaCl, 4 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 1.3 CaCl2, 10 HEPES, and 5 glucose; pH adjusted to 7.3 with NaOH). They were then placed in a recording chamber (volume, 400 μl) mounted on an upright microscope (E600FN, Nikon, Japan). Dyes were injected into cells during 10-min whole-cell patch clamp recordings, as described previously (Jagger and Forge 2006; Jagger et al. 2010; Kelly et al. 2011). Recordings were performed using a patch clamp amplifier (Axopatch 200B; Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA, USA) and a Digidata board (Axon Instruments) under the control of computer software (pClamp version 8; Axon Instruments). Continuous estimation of cell membrane capacitance (Cm) via monitoring of the electrical characteristics of the recording (membrane resistance (Rm); access resistance (Ra); membrane time constant (τ)) was carried out using the “membrane test” facility of pClamp. Patch pipettes were fabricated on a vertical puller (Narishige, Japan) from capillary glass (GC120TF-10; Harvard Apparatus, UK). Pipettes were filled with a KCl-based solution (in mM: 140 KCl, 10 NaCl, 2 MgCl2, 5 HEPES, 0.5 EGTA, and 5 glucose; pH adjusted to 7.3 with KOH). This solution was supplemented with 0.2 % neurobiotin (molecular weight, 287 Da; charge, +1; Vector Labs), and 0.2 % Lucifer yellow (di-lithium salt; 443 Da; charge, −2) or 0.2 % Fluorescein Dextran (10,000 Da; Invitrogen). Pipette solutions were filtered at 0.2 μm and centrifuged to remove small insoluble particles. Pipettes had an access resistance of 2–3 MΩ, measured in artificial perilymph. At the termination of recordings, cells were fixed immediately in 4 % PFA for 20 min at room temperature. To visualize neurobiotin, cells were incubated in Alexa555-Fluor tagged streptavidin (1:1000; Invitrogen) in 0.1 M lysine in PBS. Coverslips were mounted on glass slides using Vectashield with DAPI (Vector Labs). Confocal imaging was carried out as described above.

Collagen lattice contractility assay

Free-floating collagen gel lattices populated with spiral ligament-derived cells were prepared as described elsewhere (Grinnell et al. 1999; Ehrlich et al. 2000; Ngo et al. 2006). Optimal gel formation was determined by varying rat tail collagen (BD Bioscience) concentrations and NaOH titration for correct pH buffering. A final concentration of 1.2 mg/ml collagen-medium mixture supplemented with ∼4 μl of 1 M NaOH per gel (600 μl) was determined to be optimal. Fully confluent cells (75 cm2 flask) were detached by trypsin and suspended in 10 ml MEMα. A small sample was taken and cell concentration estimated using a haemocytometer. The cell suspension was centrifuged at 1,200 rpm for 5 min, supernatant removed and cell pellet re-suspended in the required volume of medium. To form cell-populated gels, 2 parts cell suspension was mixed with 1 part 3.6 mg/ml rat tail collagen solution plus the appropriate volume of NaOH, yielding a final concentration of ∼1 × 105 cells/ml and 1.2 mg/ml collagen. The mixture was triturated briefly, and transferred to a 24-well plate (600 μl/well). Cell concentrations were adjusted appropriately, as stated in figure legends. The gels were allowed to polymerize for 30 min at 37°C, after which the cells were distributed uniformly throughout the gel. Once the gels had set, 600 μl of fresh medium was added to each well and a pipette tip run along the gel edge to detach it from the plastic dish. Gels were incubated at 37°C, in a 5 % CO2 humidified incubator for up to 72 h. Medium was changed every 24–48 h. Gels were imaged every 24 h with a digital camera mounted to a UVP GelDocIt imaging system (VWR International, Lutterworth, UK), using a UV-to-white light converter. Gel contraction was halted by replacing the medium with a 4 % PFA-PBS solution, incubated at room temperature for 45 min. Gel surface area was measured using Image J software (http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/). Contraction was quantified by calculating the gel surface area as a percent of initial surface area. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation. Statistical analysis was carried out using Prism 4.0 software (GraphPad Software Inc, La Jolla, CA, USA). For inhibition experiments, cells were initially re-suspended in medium containing blebbistatin or meclofenamic acid. The drugs were also added to the collagen gel mixture to ensure consistent drug concentration throughout both medium and gels. For some experiments, inhibitor-containing media were replaced with fresh complete medium after 24 h. After this time point the gels began to contract, showing that the drug effects were reversible and the cells still viable. Cell viability was confirmed further with the Vybrant® CFDA SE Cell Tracer Kit (Invitrogen).

Results

Expression of type III fibrocyte markers in cells derived from spiral ligament cultures

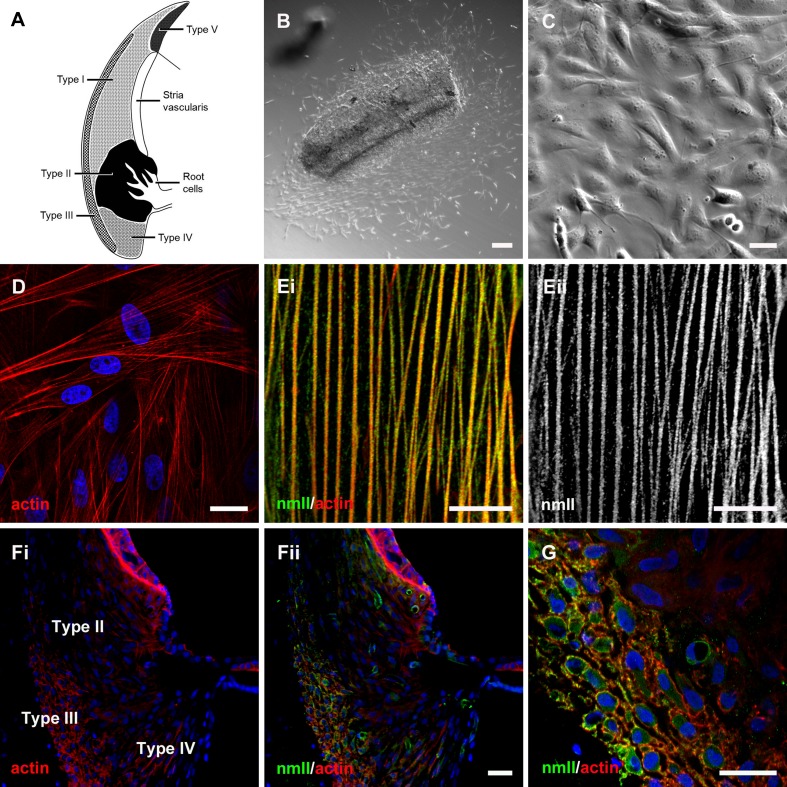

Spiral ligament fibrocytes can be classified within five distinct zones based on their immunoreactivity and their position in vivo (Spicer and Schulte 1991, 1996). This results in a schematic map of the spiral ligament showing their generalized location (Fig. 1A). Spiral ligament fibrocyte cultures have been derived from various species (Gratton et al. 1996; Suko et al. 2000; Moon et al. 2006; Qu et al. 2007), allowing their physiology to be studied in vitro. In the present study, basal turn spiral ligament was maintained in primary culture, and adherent spindle-shaped cells were observed growing out of the explants (Fig. 1B). Secondary fibrocyte cultures were then obtained from these cells after around 2–3 weeks (Fig. 1C). Fluorescent phalloidin staining revealed extensive actin stress fibers in all cells (Fig. 1D), and an anti-acetylated-tubulin antibody stained microtubules (not shown). At higher magnification, individual stress fibers could be seen to be decorated with immunofluorescence for non-muscle myosin II (nmII; Fig. 1E). Type III spiral ligament fibrocytes of mice and bats have been reported to be richly endowed with acto-myosin cytoskeletal filaments (Henson et al. 1984; Henson et al. 1985). In the basal region of vibratome sections cut from guinea pig cochlea, phalloidin staining demarcated basal cells in stria vascularis, and type III fibrocytes in spiral ligament (Fig. 1Fi). The type III fibrocytes were co-labeled with the anti-nmII antibody (Fig. 1Fii, G).

FIG. 1.

Characterization of cells cultured from spiral ligament. A Schematic representation of the cochlear lateral wall tissues, detailing the location of the fibrocyte sub-types. Type I fibrocytes are located in the spiral ligament directly behind stria vascularis; type II fibrocytes reside in a more inferior portion of the ligament, intermingled with the processes of root cells in the outer sulcus region; type III fibrocytes form a distinct strip of cells at the rear of the ligament; type IV fibrocytes are located in the most inferior portion of the ligament, below the type II cells; and type V fibrocytes are located in the supra-strial region. B Differential interference contrast (DIC) micrograph of the spiral ligament explant after 5 days in culture. Numerous migrating cells were evident. C A near-confluent secondary culture of cells. D Phalloidin staining (red) delineated actin stress fibers in cultured cells. Nuclei were counter-stained using DAPI (blue). Ei A high-magnification confocal micrograph revealed the close association between individual actin stress fibers (red) and immunofluorescence for non-muscle myosin II (nmII, green). Eii Detail of stress fiber-associated nmII immunofluorescence. Fi Within vibratome sections of the guinea pig cochlea, phalloidin noticeably labeled actin within type III fibrocytes of the spiral ligament. Fii NmII immunofluorescence within the same section was restricted to blood vessels and type III fibrocytes. G Detail of the type III fibrocyte region, showing actin/nmII co-labeling. Scale bars, B = 50, C, D, F, G = 20, E = 10 μm.

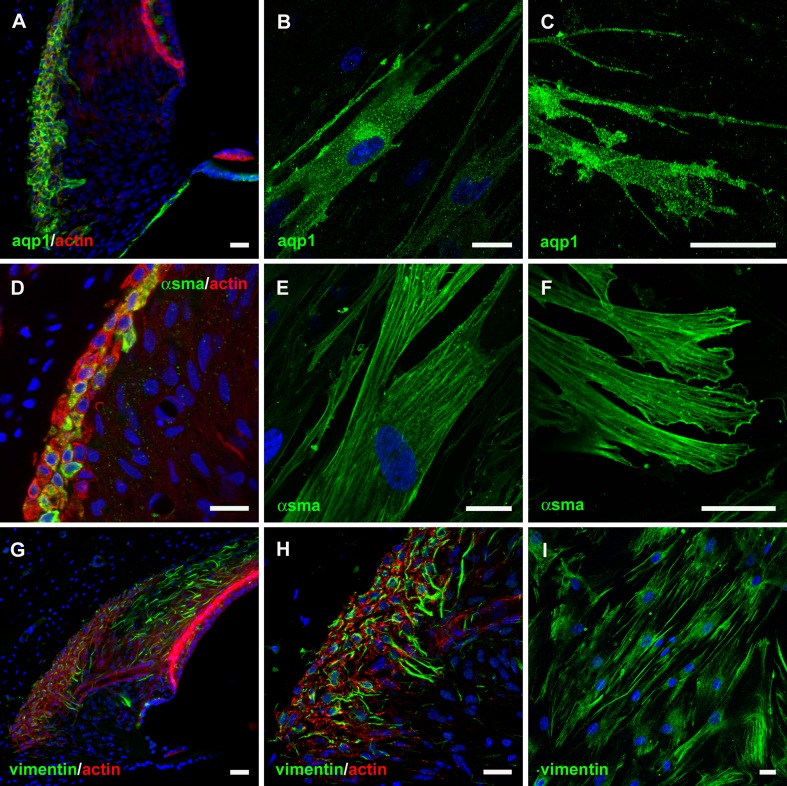

Aquaporin-1 (aqp1) has been reported as a marker of type III fibrocytes in guinea pigs (Stankovic et al. 1995), mice (Li and Verkman 2001; Huang et al. 2002), and rats (Sawada et al. 2003). In agreement with these observations, an anti-aqp1 antibody labeled type III fibrocytes, mesenchymal cells lining scala tympani, and mesenchymal cells underlying the basilar membrane of guinea pig cochlea (Fig. 2A). Aqp1 immunofluorescence was localized throughout the cytoplasm of cultured cells (Fig. 2B) and was concentrated within distal cell membrane projections (Fig. 2C). In cochlear sections, individual type III fibrocytes were also immunopositive for α-smooth muscle actin (αsma; Fig. 2D). αsma-decorated stress fibers were distributed through the cytoplasm of cultured cells (Fig. 2E), and at the adhesion points of their membrane projections (Fig. 2F). Vimentin immunofluorescence was detected within types I and III fibrocytes in guinea pig sections (Fig. 2G, H), and within numerous intracellular fibers within the cultured cells (Fig. 2I). Together, these experiments demonstrate that the cells cultured from the spiral ligament express membrane and cytoskeletal protein markers that identify them as type III fibrocytes.

FIG. 2.

Localization of type III fibrocyte-specific protein markers within cultured cells. A Within vibratome sections of the guinea pig cochlea aquaporin-1 (aqp1) immunofluorescence was restricted to type III fibrocytes and mesenchymal cells lining scala tympani. B Aqp1 immunostaining was observed within cultured cells. C Detail of aqp1 immunofluorescence within cell membrane projections. D α-smooth muscle actin (αsma) immunostaining of type III fibrocytes in the guinea pig spiral ligament. E αsma was immunolocalized to stress fibers within cultured cells. F Detail of αsma immunofluorescence in stress fibers and adhesion sites of cell membrane projections. G Vimentin immunostaining of types I and III fibrocytes in the guinea pig spiral ligament. H Detail of vimentin immunofluorescence localized to fibers within type III fibrocytes. I Vimentin was immunolocalized to fibers within cultured cells. Scale bars, 20 μm.

cx43-associated gap junctional intercellular coupling in type III fibrocytes in vitro

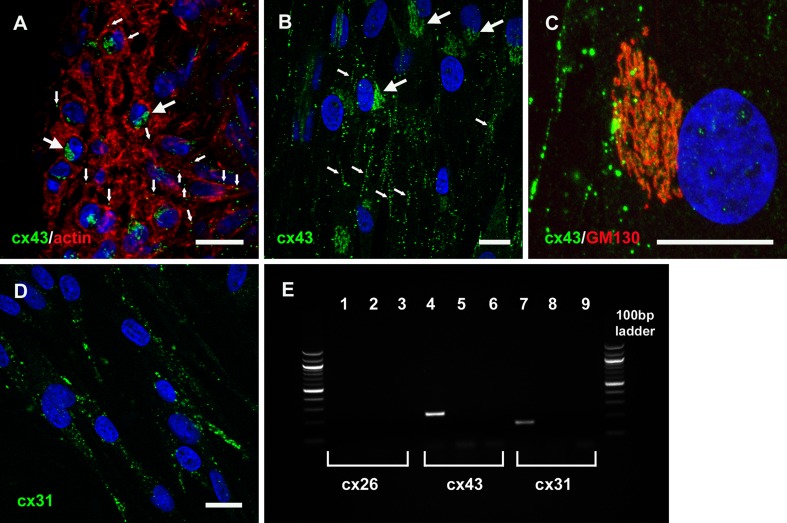

Whereas connexin 26 (cx26) and cx30 are expressed by types I, II, and V fibrocytes in vivo, cx43 has been suggested to be the major gap junction subunit expressed by type III fibrocytes (Forge et al. 2003). Accordingly, an anti-cx43 antibody labeled small intercellular puncta and larger perinuclear regions in type III fibrocytes in guinea pig cochlear sections (Fig. 3A). In all cultured cells, there were numerous cx43-labeled intercellular plaque-like structures and larger accumulations of perinuclear immunofluorescence (Fig. 3B). The perinuclear staining was co-incident with immunofluorescence for GM130 (Fig. 3C), a marker of cis-Golgi, consistent with a classical cx43 trafficking pathway (Laird 2006). The cultured cells were also labeled with a polyclonal cx31 antibody, but the immunofluorescence was restricted to intracellular puncta, with few detectable intercellular plaques (Fig. 3D). Cultures did not show labeling by anti-cx26 or anti-cx30 antibodies (not shown). The expression of RNAs for specific connexin subtypes was confirmed by RT-PCR experiments (Fig. 3E).

FIG. 3.

Characterization of connexin expression in cultured fibrocytes. A Connexin43 (cx43) immunofluorescence (green) was detected within phalloidin-labeled type III fibrocytes in vibratome sections of the guinea pig cochlea. Immunolabeling was restricted to small intercellular puncta (small arrows), and larger perinuclear aggregations (large arrows). Nuclei were counter-stained using DAPI (blue). B In cultured cells, cx43 immunofluorescence was also detected within intercellular puncta (small arrows) and also within larger diffuse perinuclear aggregations (large arrows). C The diffuse perinuclear staining was co-incident with GM130 immunofluorescence (red), a marker of cis-Golgi. D cx31 immunofluorescence was detected within extensive cytoplasmic puncta. Scale bars, 20 μm. E PCR characterization of connexin expression in cultured spiral ligament fibrocytes. There was no evidence of cx26 mRNA expression, but both cx43 and cx31 mRNA were detected. Lanes 1, 4, and 7 show + primer; lanes 2, 5, and 8 show no reverse transcriptase controls; lanes 3, 6, and 9 show water-only controls.

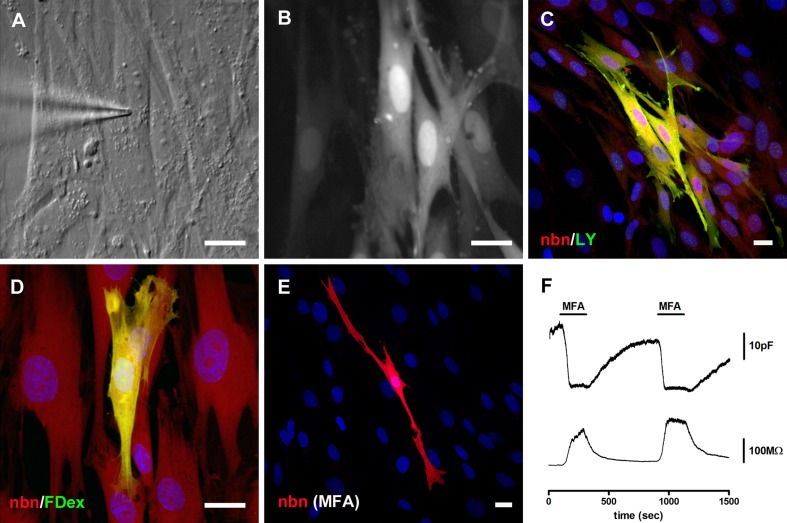

Gap junctional intercellular communication (GJIC) was assessed in dye-coupling experiments (Jagger and Forge 2006; Kelly et al. 2011). Tracer dyes of different molecular size and charge were introduced into single cells using the whole-cell patch clamp technique (Fig. 4A, B). Following fixation and processing, neurobiotin and Lucifer yellow were both detected in several cells (Fig. 4C; n = 6 experiments). In separate experiments, fluorescein dextran (molecular weight, ∼10 kDa) did not transfer between cells (Fig. 4D; n = 5), confirming that neurobiotin and Lucifer yellow had most likely transferred between cells via gap junctions and not via cytoplasmic bridges. In experiments in which cells were pre-treated with meclofenamic acid (MFA), a water-soluble blocker of cx43-containing gap junctions (Pan et al. 2007; Liu et al. 2010; Wang et al. 2010), there was no spread of neurobiotin (Fig. 4E; n = 4). During separate whole-cell recordings from small groups of cells in non-confluent cultures, transient exposure to MFA caused a reversible decrease of the estimated membrane capacitance, co-incident with an increase of the cell membrane resistance (Fig. 4F; n = 4), suggesting a reversible inhibition of gap junctions. Together, these experiments confirmed that there was functional GJIC between cultured cells, and that this communication could be modulated by MFA.

FIG. 4.

Meclofenamic acid-sensitive gap junctional coupling. A DIC video-micrograph taken during a whole-cell patch clamp dye injection into a cultured cell. B Post-recording epi-fluorescence video-micrograph showing the resulting intercellular transfer of Lucifer yellow (LY). C Post-fixation confocal projection of neurobiotin (nbn, red) and LY (green) distributions. Both dyes spread to numerous cells surrounding the injected cell. Nuclei were counterstained using DAPI (blue). D Whilst neurobiotin (red) spread to adjacent cells, Fluorescein dextran (FDex, molecular weight 10 kDa; green) was retained within the injected cell. E There was no spread of neurobiotin between cells pre-treated with 100 μM meclofenamic acid (MFA). Scale bars, 20 μm. F During a patch clamp recording from a small group of cells, estimated cell membrane capacitance (upper panel) was reduced reversibly by bath applied MFA. Cell membrane resistance (lower panel) was increased reversibly during the MFA application.

Contractility of type III fibrocytes is dependent on myosin II and gap junctional coupling

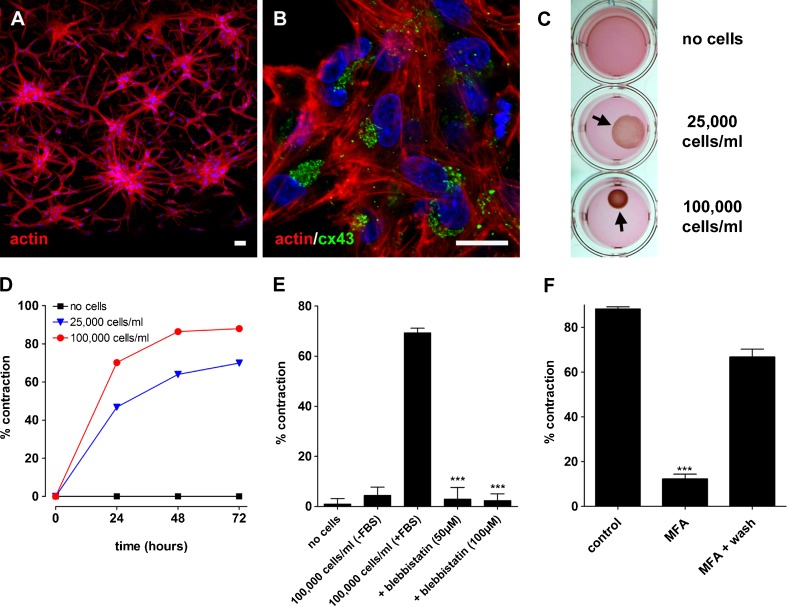

The ability of cultured type III fibrocytes to generate coordinated contractility was assessed with an assay used commonly to investigate the physiology of myofibroblasts (Grinnell et al. 1999; Ehrlich et al. 2000; Ngo et al. 2006). Cultured cells populating collagen lattice gels were able to survive and generate contraction over several days. The cells became organized into inter-connected islands within 24 h (Fig. 5A). The phalloidin labeling delineated elongated cells with multiple cell membrane processes, and showed that each contained numerous actin stress fibers. Cells continued to express nmII, αsma, and aqp1 whilst in the collagen lattice (not shown). The cells also continued to express cx43 in the characteristic pattern seen in vivo and within confluent cultures (Fig. 5B). The area of collagen lattice gels decreased with increasing numbers of cells incorporated, to a maximal density of approximately 100,000 cells/ml (Fig. 5C, D). The maximum contraction was achieved following around 2 days in vitro (Fig. 5D). There were minimal changes in area over 3 days for lattices without cells added, or for those maintained in the absence of FBS (Fig. 5E). The change of gel area mediated by the cells was reduced significantly by the addition of 50–100 μM blebbistatin (Fig. 5E), a specific inhibitor of nmII function (Limouze et al. 2004). The effects of blebbistatin were partially reversible on washout. A cell-viability assay revealed that the effects of blebbistatin did not deleteriously affect the cells within the lattice, with cells retaining a characteristic elongated shape with numerous projections (not shown). MFA also effected a reversible reduction of contractility in the cell-populated gels (Fig. 5F), suggesting that the coordinated contraction is modulated by GJIC. An assay of cell viability did not reveal any deleterious effects of MFA.

FIG. 5.

Contraction of a collagen substrate is dependent on non-muscle myosin II and gap junctional coupling. A Phalloidin staining of cultured cells populating a collagen lattice gel after 72 h in vitro. The edge of the gel is located at the lower limit of the micrograph. B Connexin43 (cx43) immunofluorescence after 72 h in vitro. Scale bars, 20 μm. C Photographs demonstrating the effect of increasing cell density on the contraction of collagen lattice gels. Gels did not contract without any cells suspended and so continued to fill the whole well area (top panel). Gels contracted by ∼40 % when 25,000 cells/ml were suspended (middle panel) and ∼70 % when 100,000 cells/ml were suspended (lower panel). The contracted gels are denoted by arrows. D Time course of collagen lattice contractions shown in (C). E Quantification of contraction under experimental conditions. Gels did not contract without cells added (n = 5), or at 100,000 cells/ml without fetal bovine serum (FBS) added (n = 5). The contraction mediated by 100,000 cells/ml (+FBS; n = 5) was reduced significantly by the addition of 50 μM blebbistatin (***p < 0.001; unpaired t test; n = 5) or 100 μM blebbistatin (p < 0.001; n = 5) to the lattice. F The contraction mediated by 100,000 cells/ml (with FBS; n = 5) was reduced significantly by the addition of 100 μM MFA (***p < 0.001; unpaired t test; n = 5). Contractility was partially recovered following washout of MFA.

Discussion

Contractile type III fibrocytes can be derived from the cultured spiral ligament

The spiral ligament presents a significant challenge to physiologists striving to decipher the mechanisms underlying cochlear homeostasis. There is a complexity in the number of cell types within this specialized connective tissue, and they are embedded within extracellular matrix that restricts access to recording techniques such as patch clamp. Cochlear slice preparations from rats have enabled patch recordings from fibrocytes in situ (Furness et al. 2009; Kelly et al. 2011), but these have been restricted within the postnatal period up to the onset of hearing. Similarly, a slice preparation of the adult guinea pig lateral wall enabled characterization of the electrophysiological properties of root cells whose cell bodies are located within the epithelial outer sulcus region (Jagger et al. 2010), but our attempts to record directly from ligament fibrocytes using this preparation have met with limited success. In the present study we took the alternative approach of deriving a cell culture of type III fibrocytes. We demonstrate that cells in this culture generate coordinated contractions dependent on nmII, and that they can communicate via gap junctions, an intercellular signaling mechanism which modulates the contractility.

Cultured cell-lines present perhaps the best available approach to characterize the physiology of mature spiral ligament fibrocytes. Cultures of type I fibrocytes have been used to study ion channel physiology (Liang et al. 2004; Shen et al. 2004; Liang et al. 2005) and the secretion of chemokines (Moon et al. 2006). A culture of type IV fibrocytes from rat spiral ligament has been derived to study chloride channels (Qu et al. 2007). To our knowledge, there have been no previous reports of type II or V fibrocyte cultures, although these subtypes would be difficult to distinguish in vitro. Similarly, cultures of type III fibrocytes have not been reported. The cell-line derived in the present study displayed physical characteristics closely matching those of type III fibrocytes in vivo. Most notably, these included the presence of prominent stress fibers (Henson et al. 1985; Kuhn and Vater 1997) that we determined contained αsma both in vivo and in vitro. The cells also expressed recognized type III fibrocyte markers such as nmII (Henson et al. 1985), aqp1 (Stankovic et al. 1995; Li and Verkman 2001; Huang et al. 2002; Sawada et al. 2003), and cx43 (Forge et al. 2003). The cells could generate prolonged contractility within a collagenous substrate, assumed to be a primary property of type III fibrocytes in vivo (Henson et al. 1984; Naidu and Mountain 2007). The physical properties of the type III fibrocyte compartment should vary along the tonotopic axis of the spiral ligament. These cells are most numerous in the basal region of the cochlea (Henson and Henson 1988), and it is in this region that they are most heavily endowed with acto-myosin cytoskeletal elements. This suggests that type III fibrocyte contractility contributes mostly to high frequency sound-coding. It is important to note, however, that aqp1-labelled “bone-lining” cells can be found in all turns of the guinea pig cochlea (Stankovic et al. 1995), suggesting that type III fibrocytes make some contribution to normal hearing in all tonotopic locations.

The ubiquity of aqp1 expression within type III fibrocytes raises questions as to its role in normal hearing, particularly as aqp1-null mice have been reported to have normal hearing sensitivity (Li and Verkman 2001), at least to 12 kHz tones. Aqp1 has been implicated recently in diverse cell migratory mechanisms such as wound healing and tumor spreading (Papadopoulos et al. 2008), and aqp1 localized within the membrane of lamellipodia is suggested to facilitate local water influx resulting in membrane protrusion (Saadoun et al. 2005). This mechanism works in concert with nmII-dependent force generation to focus tension at key adherence points, thus supporting cell migration (Papadopoulos et al. 2008). Aquaporins facilitate regulated water permeability in various sensory and non-sensory tissues, a process which may be crucial for the maintenance of normal tissue mechanics and the ionic balance of fluids. Aqp1 is expressed by cells in the trabecular meshwork of the eye, where it is associated with the regulation of aqueous humor volume and intra-ocular pressure (Verkman 2003; Lin et al. 2007). Cells in this meshwork also express cx43, αsma, nmII, and vimentin (Kimura et al. 2000; Zhang and Rao 2005; Lin et al. 2007; Inoue et al. 2010). These properties suggest parallels in the functions mediated by the trabecular meshwork and the continuous helical strip formed by type III fibrocytes. We suggest that in addition to nmII-dependent basilar membrane tensioning in the basal region (Naidu and Mountain 2007), type III fibrocytes may also act via aqp1 to regulate hydrostatic pressure within the whole spiral ligament.

Contractility in type III fibrocytes is modulated by gap junctional coupling

GJIC is necessary for numerous processes in cochlear development and normal hearing function (Jagger and Forge 2006; Jagger et al. 2010; Kelly et al. 2011). Following hair cell transduction, K+ is buffered within the epithelial gap junction network formed by supporting cells and root cells (Jagger and Forge 2006; Jagger et al. 2010). K+ secreted from the processes of root cells may be sequestered into type II fibrocytes via ion pumps and co-transporters (Spicer and Schulte 1991, 1996), and then distributed back to the stria via the connective tissue gap junction network comprising types I, II, and V fibrocytes. These gap junctions, like those in the epithelial network, consist of only cx26 and/or cx30 subunits (Forge et al. 2003; Liu and Zhao 2008).

The nature of GJIC in fibrocyte cultures has not been studied extensively. Despite the apparent importance of cx26 and cx30 within fibrocytes in vivo, there is little evidence that they are expressed by those cells in vitro. Gap junctions were reported to be absent from type I fibrocyte cultures (Gratton et al. 1996), with the authors suggesting this may be a consequence of the culture conditions used. Also, in patch clamp studies cells have been dissociated using trypsin/EDTA-containing media (Shen et al. 2004; Liang et al. 2005), a treatment that further discourages gap junction formation. As might be expected, gap junctions were not observed in type IV fibrocyte cultures (Qu et al. 2007). Cells in near-confluent cultures described here were inter-connected via functional gap junctions. cx26 and cx30 were absent, but there was immunofluorescence for cx31 and cx43. cx43 was localized in a pattern consistent with normal trafficking and functional GJIC (Laird 2006). cx31 immunofluorescence was restricted to apparently cytoplasmic sites, with few if any gap junction plaques being detected. cx31 has been described previously in type II fibrocytes (Xia et al. 2000; Forge et al. 2003), an observation we confirmed in guinea pig sections (data not shown). We also observed intracellular cx31 immunofluorescence in type III fibrocytes but not within intercellular plaque-like arrangements. It seems unlikely therefore that cx31 and cx43 form heteromeric gap junction channels in type III fibrocytes, and we conclude that functional GJIC here occurred via homomeric cx43 channels.

Dye transfer within cultures was inhibited by MFA, a reversible blocker of cx43-containing channels in various tissues (Harks et al. 2001; Pan et al. 2007; Liu et al. 2010; Wang et al. 2010). This agent has been reported to modulate inter-kinetic nuclear migration (INM), via its inhibition of gap junctional signaling and the resultant regulation of the cytoskeleton (Liu et al. 2010). INM has also been shown to be regulated directly by cx43-dependent gap junctional coupling (Pearson et al. 2005). Here, MFA caused a reversible inhibition of contraction in cell-populated collagen lattices, suggesting that cx43-mediated GJIC may be essential for the coordination of force generation. cx43-dependent contraction has also been reported in dermal fibroblast-populated collagen gels (Ehrlich et al. 2000), leading to speculation that cx43 may be important in the organization of extracellular collagen fibers in vivo. In the spiral ligament, type III fibrocytes are proposed to exert effects on basilar membrane tension by interacting with extracellular collagen-containing anchoring fibers that extend between the hyaline attachment zone of the basilar membrane and the otic capsule (Henson and Henson 1988; Dreiling et al. 2002; Naidu and Mountain 2007). We propose that the gain of this nmII-dependent tensioning process is set via cx43-dependent GJIC between type III fibrocytes. The generation of tension and fluid volume regulation by type III fibrocytes in situ remains to be demonstrated directly, but adaptations of the cell-populated collagen lattice technique may provide further insights into the micromechanical properties of the spiral ligament-basilar membrane complex.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (grant BB/D009669/1 to DJJ and AF) and Deafness Research UK (grant 358.CAR.DJ to DJ). JJK was supported by a Deafness Research UK Studentship (grant 403.EIP.DM). DJJ was supported by a Royal Society University Research Fellowship (grant 516002.K5746.KK). We thank Victoria Tovell (Institute of Ophthalmology, UCL) for helpful advice on the collagen lattice technique and cell viability assay.

References

- Adams JC. Immunocytochemical traits of type IV fibrocytes and their possible relations to cochlear function and pathology. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol. 2009;10:369–382. doi: 10.1007/s10162-009-0165-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di WL, Rugg EL, Leigh IM, Kelsell DP. Multiple epidermal connexins are expressed in different keratinocyte subpopulations including connexin 31. J Invest Dermatol. 2001;117:958–964. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-202x.2001.01468.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreiling FJ, Henson MM, Henson OW., Jr The presence and arrangement of type II collagen in the basilar membrane. Hear Res. 2002;166:166–180. doi: 10.1016/S0378-5955(02)00314-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrlich HP, Gabbiani G, Meda P. Cell coupling modulates the contraction of fibroblast-populated collagen lattices. J Cell Physiol. 2000;184:86–92. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(200007)184:1<86::AID-JCP9>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forge A, Becker D, Casalotti S, Edwards J, Marziano N, Nevill G. Gap junctions in the inner ear: comparison of distribution patterns in different vertebrates and assessement of connexin composition in mammals. J Comp Neurol. 2003;467:207–231. doi: 10.1002/cne.10916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furness DN, Lawton DM, Mahendrasingam S, Hodierne L, Jagger DJ. Quantitative analysis of the expression of the glutamate-aspartate transporter and identification of functional glutamate uptake reveal a role for cochlear fibrocytes in glutamate homeostasis. Neuroscience. 2009;162:1307–1321. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratton MA, Schulte BA, Hazen-Martin DJ. Characterization and development of an inner ear type I fibrocyte cell culture. Hear Res. 1996;99:71–78. doi: 10.1016/S0378-5955(96)00080-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grinnell F, Ho CH, Lin YC, Skuta G. Differences in the regulation of fibroblast contraction of floating versus stressed collagen matrices. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:918–923. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.2.918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harks EG, Roos AD, Peters PH, Haan LH, Brouwer A, Ypey DL, Zoelen EJ, Theuvenet AP. Fenamates: a novel class of reversible gap junction blockers. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2001;298:1033–1041. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henson MM, Henson OW., Jr Tension fibroblasts and the connective tissue matrix of the spiral ligament. Hear Res. 1988;35:237–258. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(88)90121-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henson MM, Henson OW, Jr, Jenkins DB. The attachment of the spiral ligament to the cochlear wall: anchoring cells and the creation of tension. Hear Res. 1984;16:231–242. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(84)90112-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henson MM, Burridge K, Fitzpatrick D, Jenkins DB, Pillsbury HC, Henson OW., Jr Immunocytochemical localization of contractile and contraction associated proteins in the spiral ligament of the cochlea. Hear Res. 1985;20:207–214. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(85)90025-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hequembourg S, Liberman MC. Spiral ligament pathology: a major aspect of age-related cochlear degeneration in C57BL/6 mice. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol. 2001;2:118–129. doi: 10.1007/s101620010075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang D, Chen P, Chen S, Nagura M, Lim DJ, Lin X. Expression patterns of aquaporins in the inner ear: evidence for concerted actions of multiple types of aquaporins to facilitate water transport in the cochlea. Hear Res. 2002;165:85–95. doi: 10.1016/S0378-5955(02)00288-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue T, Pecen P, Maddala R, Skiba NP, Pattabiraman PP, Epstein DL, Rao PV. Characterization of cytoskeleton-enriched protein fraction of the trabecular meshwork and ciliary muscle cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51:6461–6471. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-5318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jagger DJ, Forge A. Compartmentalized and signal-selective gap junctional coupling in the hearing cochlea. J Neurosci. 2006;26:1260–1268. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4278-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jagger DJ, Nevill G, Forge A. The membrane properties of cochlear root cells are consistent with roles in potassium recirculation and spatial buffering. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol. 2010;11:435–448. doi: 10.1007/s10162-010-0218-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JJ, Forge A, Jagger DJ. Development of gap junctional intercellular communication within the lateral wall of the rat cochlea. Neuroscience. 2011;180:360–369. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura S, Suzuki K, Sagara T, Nishida T, Yamamoto T, Kitazawa Y. Regulation of connexin phosphorylation and cell-cell coupling in trabecular meshwork cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;41:2222–2228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn B, Vater M. The postnatal development of F-actin in tension fibroblasts of the spiral ligament of the gerbil cochlea. Hear Res. 1997;108:180–190. doi: 10.1016/S0378-5955(97)00051-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laird DW. Life cycle of connexins in health and disease. Biochem J. 2006;394:527–543. doi: 10.1042/BJ20051922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Verkman AS. Impaired hearing in mice lacking aquaporin-4 water channels. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:31233–31237. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104368200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang F, Hu W, Schulte BA, Mao C, Qu C, Hazen-Martin DJ, Shen Z. Identification and characterization of an L-type Cav1.2 channel in spiral ligament fibrocytes of gerbil inner ear. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2004;125:40–46. doi: 10.1016/j.molbrainres.2004.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang F, Schulte BA, Qu C, Hu W, Shen Z. Inhibition of the calcium- and voltage-dependent big conductance potassium channel ameliorates cisplatin-induced apoptosis in spiral ligament fibrocytes of the cochlea. Neuroscience. 2005;135:263–271. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.05.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limouze J, Straight AF, Mitchison T, Sellers JR. Specificity of blebbistatin, an inhibitor of myosin II. J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 2004;25:337–341. doi: 10.1007/s10974-004-6060-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin S, Lee OT, Minasi P, Wong J. Isolation, culture, and characterization of human fetal trabecular meshwork cells. Curr Eye Res. 2007;32:43–50. doi: 10.1080/02713680601107058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu YP, Zhao HB. Cellular characterization of connexin26 and connnexin30 expression in the cochlear lateral wall. Cell Tissue Res. 2008;333:395–403. doi: 10.1007/s00441-008-0641-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Hashimoto-Torii K, Torii M, Ding C, Rakic P. Gap junctions/hemichannels modulate interkinetic nuclear migration in the forebrain precursors. J Neurosci. 2010;30:4197–4209. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4187-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon SK, Park R, Lee HY, Nam GJ, Cha K, Andalibi A, Lim DJ. Spiral ligament fibrocytes release chemokines in response to otitis media pathogens. Acta Otolaryngol. 2006;126:564–569. doi: 10.1080/00016480500452525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naidu RC, Mountain DC. Basilar membrane tension calculations for the gerbil cochlea. J Acoust Soc Am. 2007;121:994–1002. doi: 10.1121/1.2404916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngo P, Ramalingam P, Phillips JA, Furuta GT. Collagen gel contraction assay. Methods Mol Biol. 2006;341:103–109. doi: 10.1385/1-59745-113-4:103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohlemiller KK. Mechanisms and genes in human strial presbycusis from animal models. Brain Res. 2009;1277:70–83. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.02.079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan F, Mills SL, Massey SC. Screening of gap junction antagonists on dye coupling in the rabbit retina. Vis Neurosci. 2007;24:609–618. doi: 10.1017/S0952523807070472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papadopoulos MC, Saadoun S, Verkman AS. Aquaporins and cell migration. Pflugers Arch. 2008;456:693–700. doi: 10.1007/s00424-007-0357-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson RA, Luneborg NL, Becker DL, Mobbs P. Gap junctions modulate interkinetic nuclear movement in retinal progenitor cells. J Neurosci. 2005;25:10803–10814. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2312-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu C, Liang F, Smythe NM, Schulte BA. Identification of ClC-2 and CIC-K2 chloride channels in cultured rat type IV spiral ligament fibrocytes. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol. 2007;8:205–219. doi: 10.1007/s10162-007-0072-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saadoun S, Papadopoulos MC, Hara-Chikuma M, Verkman AS. Impairment of angiogenesis and cell migration by targeted aquaporin-1 gene disruption. Nature. 2005;434:786–792. doi: 10.1038/nature03460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawada S, Takeda T, Kitano H, Takeuchi S, Okada T, Ando M, Suzuki M, Kakigi A. Aquaporin-1 (AQP1) is expressed in the stria vascularis of rat cochlea. Hear Res. 2003;181:15–19. doi: 10.1016/S0378-5955(03)00131-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Z, Liang F, Hazen-Martin DJ, Schulte BA. BK channels mediate the voltage-dependent outward current in type I spiral ligament fibrocytes. Hear Res. 2004;187:35–43. doi: 10.1016/S0378-5955(03)00345-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spicer SS, Schulte BA. Differentiation of inner ear fibrocytes according to their ion transport related activity. Hear Res. 1991;56:53–64. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(91)90153-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spicer SS, Schulte BA. The fine structure of spiral ligament cells relates to ion return to the stria and varies with place-frequency. Hear Res. 1996;100:80–100. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(96)00106-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stankovic KM, Adams JC, Brown D. Immunolocalization of aquaporin CHIP in the guinea pig inner ear. Am J Physiol. 1995;269:C1450–C1456. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1995.269.6.C1450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suko T, Ichimiya I, Yoshida K, Suzuki M, Mogi G. Classification and culture of spiral ligament fibrocytes from mice. Hear Res. 2000;140:137–144. doi: 10.1016/S0378-5955(99)00191-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor RR, Jagger DJ, Forge A. Defining the cellular environment in the organ of Corti following extensive hair cell loss: a basis for future sensory cell replacement in the cochlea. PLoS One. 2012;7:e30577. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verkman AS. Role of aquaporin water channels in eye function. Exp Eye Res. 2003;76:137–143. doi: 10.1016/S0014-4835(02)00303-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vicente-Manzanares M, Ma X, Adelstein RS, Horwitz AR. Non-muscle myosin II takes centre stage in cell adhesion and migration. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:778–790. doi: 10.1038/nrm2786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Veruki ML, Bukoreshtliev NV, Hartveit E, Gerdes HH. Animal cells connected by nanotubes can be electrically coupled through interposed gap-junction channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:17194–17199. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1006785107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wangemann P. Supporting sensory transduction: cochlear fluid homeostasis and the endocochlear potential. J Physiol. 2006;576:11–21. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.112888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia AP, Ikeda K, Katori Y, Oshima T, Kikuchi T, Takasaka T. Expression of connexin 31 in the developing mouse cochlea. Neuroreport. 2000;11:2449–2453. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200008030-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M, Rao PV. Blebbistatin, a novel inhibitor of myosin II ATPase activity, increases aqueous humor outflow facility in perfused enucleated porcine eyes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:4130–4138. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-0164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]