Abstract

Excess exposure to Mn causes a neurological disorder known as manganism which is similar to dystonic movements associated with Parkinson’s disease. Manganism is largely restricted to occupations in which high atmospheric levels are prevalent which include Mn miners, welders and those employed in the ferroalloy processing or related industrial settings. T1 weighted MRI images reveal that Mn is deposited to the greatest extent in the globus pallidus, an area of the brain that is presumed to be responsible for the major CNS associated symptoms. Neurons within the globus pallidus receive glutamatergic input from the subthalamic nuclei which has been suggested to be involved in the toxic actions of Mn. The neurotoxic actions of Mn and glutamate are similar in that they both affect calcium accumulation in the mitochondria leading to apoptotic cell death. In this paper we demonstrate that the combination of Mn and glutamate potentiates toxicity of neuronally differentiated P19 cells over that observed with either agent alone. Apoptotic signals ROS, caspase 3 and JNK were increased in an additive fashion when the two neurotoxins were combined. The anti-glutamatergic drug, riluzole, was shown to attenuate these apoptotic signals and prevent P19 cell death. Results of this study confirm, for the first time, that Mn toxicity is potentiated in the presence of glutamate and that riluzole is an effective antioxidant which protects against both Mn and glutamate toxicity.

Keywords: manganese, glutamate, riluzole, P19 embryonic carcinoma cells, apoptosis, manganism

Introduction

Considerable progress has been made within the past several decades regarding the mechanism by which Mn induces cell death. The preponderance of the evidence suggests that cell death is mediated by oxidative stress leading to apoptosis initiated by disruption of mitochondrial function (Desole et al., 1996; Desole et al., 1997; Gunter et al., 2009; Hirata et al., 1998b; Kim et al., 2000; Schrantz et al., 1999). Evidence for apoptosis is demonstrated by the fact that many of the classical signaling pathways associated with programmed cell death are activated in cells treated with Mn. These include: increased TUNEL staining, internucleosomal DNA cleavage, activation of the JNK and p38 (stress activated protein kinase), activation of caspase-3 like activity, and caspase-3 dependent cleavage of PARP (Chun et al., 2001; Desole et al., 1996; Desole et al., 1997; Hirata et al., 1998a; Latchoumycandane et al., 2005; Roth et al., 2000; Schrantz et al., 1999). In addition, overexpression of the anti-apoptotic protein, Bcl-2, is capable of preventing Mn-stimulated toxicity (Schrantz et al., 1999).

One of the major questions which has not been adequately addressed in the literature is why cells within the globus pallidus are the primary target upon exposure to high levels of Mn. T1-weighted MRI images clearly reveal that the globus pallidus accumulates Mn to the greatest extent in individuals exposed to elevated levels of Mn (Kim, 2004; Pal et al., 1999; Uchino et al., 2007) but other areas of brain, such as the substantia nigra, also accumulate Mn (Erikson et al., 2004; Kim et al., 2002) although these regions are affected to lesser degree, if at all. Thus, additional mechanisms must prevail to account for this selectivity. Relevant to this is the fact that neurons within the globus pallidus receive glutamatergic input from neurons within the subthalamic nuclei (Plenz and Kital, 1999; Rouse et al., 2000). Several papers have demonstrated that Mn can potentiate glutamate excitotoxicity by inhibiting its uptake into astrocytes thus, leading to elevated levels of this neurotransmitter within the synapse ( Erikson and Aschner, 2002; Hazell and Norenberg, 1997). Supporting the involvement of glutamate in enhancing Mn toxicity are studies demonstrating that the glutamatergic antagonist, MK801, can alleviate the toxic actions of Mn in vivo in rats (Brouillet et al., 1993; Xu et al., 2010). Related to this is the fact that cytotoxic events provoking Mn toxicity, to a large extent, parallel similar pathways for that of glutamate, as both involve loss of mitochondrial function initiated by excess sequestration of calcium. Additionally, both Mn and glutamate stimulate several MAP kinases which have been shown to be involved in their cytotoxic actions (Baldwin et al., 1999; Grant et al., 2001; Roth, 2006; Roth et al., 2002; Stanciu and DeFranco, 2002). Because these agents share common cytotoxic mechanisms, coupled with the fact that glutamate can stimulate Mn uptake via its Ca+2 ionotropic receptor (Kannurpatti et al., 2000), it is reasonable to hypothesize that these complimentary processes may provoke an increase in the cytotoxic responses which account for pallidal neurons being more sensitive to Mn. In this paper, we demonstrate, for the first time, that apoptotic signaling mechanisms responsible for Mn toxicity are stimulated when incubations are performed in the presence of glutamate which, in a similar fashion, may account for the selectivity of Mn within the globus pallidus.

A recent paper by Deng et al. (Deng et al., 2009) reported that the anti-glutamatergic drug, riluzole, can protect against Mn toxicity in rats. Riluzole is a potent glutamate antagonist primarily used clinically for the treatment of Huntington’s disease. The primary mode of action, in vivo, is attributed to its ability to suppress glutamatergic activity by inhibiting the release of both glutamate and aspartate (Martin et al., 1993). Recent studies have also reported that riluzole can protect against disruption of the glutamate transporter by Mn (Deng et al., 2012; Yoshizumi et al., 2012). In addition, its neuroprotective actions have also been ascribed to its antioxidant properties ( Koh et al., 1999; Storch et al., 2000) as it has been shown to prevent toxicity in mouse cultured cortical neurons produced by kainic acid, NMDA and ferric ion. The mechanism, however, by which riluzole prevents Mn toxicity has not been adequately explored. In this paper, we demonstrate that riluzole can act as an potent antioxidant and, as such, is capable of suppressing cell signaling leading to Mn toxicity in retinoic acid-induced differentiated P19 cells, a cortical neuronal cell model that expresses both the NMDA and AMPA/kainate receptors (Lee et al., 2003).

2. Methods

2.1 Materials

P19 embryonic carcinoma cells were purchased from A.T.C.C. and MEM alpha, neurobasal medium, B-27 serum free supplements, penicillin/ streptomycin and fetal bovine serum from Invitrogen (Gibco BRL, Grand Island, NY). Phospho-JNK antibody, anti-GAPDH antibody and secondary antibody for Western blots were obtained from Cell Signaling (Danvers, MA) and Western lightning plus substrate to develop immunoblots was from Perkin Elmer (Waltham, MA). SNAP-ID equipment was purchased from Millipore Corporation (Billerica, MA). Complete protease inhibitor cocktail and PhosphoSTOP, phosphatase inhibitor was from Roche diagnostics (Indianapolis, IN).

2.2. Cell culture conditions

P19 embryonic carcinoma cells were maintained in MEM alpha medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum and penicillin (50 U/ml) and streptomycin (50 μg/ml). Cells were grown at 37°C in humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 and subcultured every 3-4 days at approximately 70% confluency. Differentiation of the P19 cells into neuroectodermal cells (neurons and glia) was initiated by treating the cells with two rounds of 500 nM retinoic acid (RA) as previously described ( Jones-Villeneuve et al., 1983). In short, cells were plated onto a bacterial culture dish for four days in the presence of RA after which aggregates were broken down by trypsinization and moved to tissue culture dish containing neurobasal medium plus B-27 supplements in the absence of RA. The cells begin to differentiate to form neurons and glia and were subsequently treated twice with the anti-mitogen, Ara-c (5μg/ml), in order to obtain relative pure preparations of neuronal cells. Based on histological analysis of cells expressing neuronal projections, it was estimated that the final preparation was approximately 90% neurons.

2.3. Trypan blue dye exclusion

Differentiated P19 cells were treated with MnCl2 (0.3 mM), sodium glutamate (5 mM in water) and/ or riluzole (10 μM) for 18 hrs. and the cell viability was measured by trypan blue dye exclusion method. The cells were centrifuged at 100 X g and the pellet was resuspended in 1ml PBS. Equal volume of the cell suspension was mixed with trypan blue dye and incubated for 2 minutes before the cells were counted on a hemocytometer. Data is representative of four independent experiments.

2.4. Reactive oxygen species

Differentiated P19 cells were grown on six well plates and treated with MnCl2 (0.3 mM), or glutamate (5 mM) alone or both compounds in the presence and absence of riluzole (10 μM) for 2 hrs. Cells were resuspended in PBS and 2′, 7′-dichlorofluorescin diacetate (DCFH-DA) dye (Sigma chemicals, St. Louis, MO) was added directly to the cell suspension to reach a concentration of 10 μM. The cell suspension was incubated at 37°C for 15-30 minutes before they were analyzed by flow cytometry on the FL-1H channel (FACScalibur, Becton Dickinson, NJ).

2.5. Caspase assay

Differentiated P19 cells were treated with MnCl2 (0.3 mM), glutamate (5 mM) and/ or riluzole (10 μM) for 18 hrs. Cell lysates prepared in lysis buffer containing complete protease inhibitor were incubated for 30 minutes on ice and subsequently centrifuged for 10 minutes at 10,000 x g to remove particulates. Protein concentration was determined using BCA assay. Sample lysates were transferred to a 96 well plate and assayed for caspase-3 activity using the Enzchek Caspase-3 assay kit (Molecular Probes, Grand Island, NY). Z-DEVD-AMC substrate working solution was added to all the wells and incubated for 30 minutes. Fluorescence was measured using excitation at 350 nm and emission detection at 450 nm on a Fluorescence multi-well plate reader (Biotek, VT).

2.6. Western blots

Differentiated P19 cells were grown on six well plates and treated with MnCl2 (0.3 mM), glutamate (5 mM) and/ or riluzole (10 μM) for 18 hrs. Cell homogenates were prepared in lysis buffer containing 50 mM Tris HCl (pH 8.0), 2 mM EDTA, 100 mM NaCl, 1% Triton-X 100, complete protease inhibitor cocktail and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail. Lysates were incubated for 30 minutes on ice and clarified by centrifugation. Protein concentrations were determined by BCA protein assay (bicinchoninic acid; Pierce, Rockford, IL) using a Nanodrop 2000c spectrophotometer. Cell lysates (15μg of sample/lane) were electrophoresed on 12% (w/v) polyacrylamide gels and then transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane. The immuno-blotting was performed on SNAP-ID (Millipore) using rabbit polyclonal phospho-JNK antibody. Conjugated goat anti-rabbit horseradish peroxidase was used as the secondary antibody and anti-GAPDH antibody was used as a loading control. Blots were scanned and the intensity was measured using Image J software. The data is representative of four independent experiments.

2.7. Statistical considerations

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software. The one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with post hoc test Tukey-Bonferroni was used to determine differences in mean values between the different conditions. A p value ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3.Results

3.1. Mn/glutamate toxicity

Retinoic acid-induced neuronally differentiated mouse P19 embryonic carcinoma cells express both the NMDA and AMPA/kainate receptors and thus, serve as a good model to study the interaction between Mn and glutamate (Lee et al., 2003) independent of the presence of dopamine under the conditions employed to maintain the cells in culture (Wu et al., 2008). Accordingly, these cells were used to determine whether glutamate was capable of potentiating Mn-induced cell death. For these experiments, cells were treated with Mn or glutamate alone or in the presence of both compounds for 18 hrs. followed by trypan blue dye exclusion to assess toxicity. The concentration of Mn, 0.3 mM, chosen for these experiments has commonly been employed in other studies that have examined the cytotoxic properties of Mn in a variety of cell culture systems (El Mchichi et al., 2007; Hirata et al., 1998a; Lee et al., 2009; Roth et al., 2000; Stredrick et al., 2004; Xu et al., 2009) and was selected as it provided a level of cell death in which the combined effects with glutamate could readily be assessed. Mean values ± S.E. from four separate experiments are presented in Fig. 1. The overall percent toxicity was calculated by subtracting the measured percent toxicity minus that obtained with the DMSO-treated control (17.3%). Cell death in these control cultures may have been caused by either the use of neurobasal media (Hogins et al., 2011) or DMSO. Under these conditions, both Mn and glutamate individually generated approximately 24% toxicity providing values which effectively can be applied to assess an additive effect of the two neurotoxins. As indicated in Fig. 1, when fully differentiated P19 cells were exposed to both glutamate and Mn, there was a significant increase (p < 0.01) in toxicity of approximate 30% compared to treatment with either agent alone. Results of these experiments support the hypothesis that the cytotoxic actions of the two neurotoxins are at least partially additive.

Fig. 1.

The effect of riluzole on manganese/glutamate toxicity in neuronally differentiated P19 cells. Neuronally differentiated P19 cells were treated with Mn (0.3 mM), glutamate (G; 5 mM) and /or riluzole (R; 10 μM) for 18 hrs. Toxicity was measured by trypan blue dye exclusion assay compared to the control samples treated with only riluzole/DMSO. Data is the mean ± S.E. of at least three independent experiments; a,c,ep < 0.001 differences from vehicle only control; b,d,fp < 0.001 differences from Mn and/or glutamate treatment alone.

3.2. Riluzole protection against Mn and glutamate toxicity

Experiments were also performed to test the ability of riluzole to protect against Mn and glutamate toxicity in neuronally differentiated P19 cells. Because riluzole was by itself cytotoxic, we were limited in the concentration of riluzole we could use to examine an effect on cell survival. The cytotoxicity observed with riluzole is consistent with prior studies using various cell culture systems (Akamatsu et al., 2009; Chen et al., 2006; Estevez et al., 1995; Kaal et al., 2000; Khan et al., 2011; Storch et al., 2000). The concentration of riluzole chosen, 10 μM, has previously been reported to be protective against rat mescenphalic cell death caused by MPP+ (Storch et al., 2000) and cell toxicity using mixed mouse cortical cultures produced by 300 μM NMDA (Koh et al., 1999). As illustrated by the data in Fig. 1, the percentage of overall toxicity for P19 cells treated with riluzole in the presence of Mn, glutamate or a combination of both agents was calculated by subtracting the riluzole-only control (6.9%) from percent toxicity for incubations when riluzole was added to the media in order to exclude the direct effect of the drug on ROS formation in order to obtain a more accurate assessment of the influence of Mn and glutamate on ROS production. As indicated by the data in Fig. 1, riluzole at this concentration protected both Mn and glutamate toxicity approximately 60%. In comparison, percent protection (43.6%) by riluzole for incubations performed in the presence of both Mn and glutamate, was decreased approximately 30%. This difference may have been caused by the amplification of oxidative stress signals resulting in the decreased ability of riluzole to suppress toxicity. Nevertheless, for all three conditions, protection by riluzole was significantly different from the corresponding treatments without riluzole having p values less than 0.001. Lower concentrations of riluzole were also examined but failed to noticeably correct cellular damage caused by Mn and glutamate whereas higher concentrations produced greater toxicity.

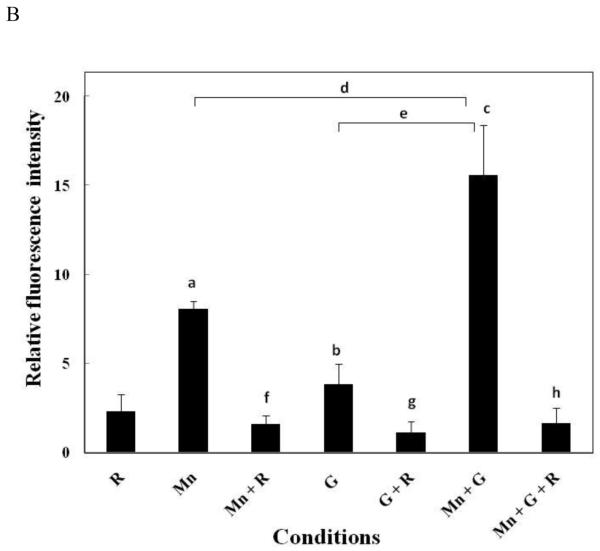

3.3. ROS generation

It is generally agreed upon that both Mn and glutamate-induced toxicity proceeds via disruption of mitochondrial function leading to formation of ROS (Gunasekar et al., 1995; Roth and Garrick, 2003). Since toxicity was greatest in cells simultaneously exposed to both Mn and glutamate, studies were carried out to examine whether the combined treatment would generate greater increases in ROS formation when compared to treatment with either agent alone. Results of these experiments illustrated in Fig. 2A and B indicate that both Mn (0.3 mM) and glutamate (5 mM) by themselves significantly increased ROS formation in neuronally differentiated P19 cells whereas the combined treatment resulted in even a greater amplification in ROS generation. For these studies, ROS generation was indicated by the spectral shift of the fluorescence curve to the right. Results were assessed at 2 hrs. instead of 18 hrs. as used for the other assays since production of ROS is an early event leading to apoptotic cell death. At 2 hours after initiating treatment, riluzole by itself produced about a two-fold increase in ROS whereas treatment with Mn increased ROS production approximately 8-fold while glutamate increased ROS formation about 4-fold (Fig. 2B). When the two agents were combined, ROS production was slightly greater than additive yielding an increase of approximately 16-fold over the control value. Although not shown, similar results were obtained after 4 hrs. of treatment with Mn and glutamate. In addition, experiments were also performed to examine the protective effects of riluzole on ROS formation in cells treated with Mn, glutamate and both agents combined. Results of these experiments expressed as an average of ROS produced for each of the conditions minus the appropriate control are presented in Fig. 2B and demonstrate that riluzole significantly suppressed ROS formation essentially back to the riluzole value which is consistent with the proposed antioxidant properties of this drug.

Fig. 2.

The fluorescence intensity of intracellular ROS was analyzed by DCFH-DA staining using flow cytometer upon treatment with Mn, glutamate and/ or riluzole in neuronally differentiated P19 cells. Neuronally differentiated P19 cells were treated for two hrs. with Mn (0.3 mM), glutamate (G; 5 mM) and/ or riluzole (R; 10μM). Results for ROS generation in treated cells were compared to the control incubations containing DMSO or riluzole. (A) Scatter plot showing the gated region of cells that were selected for analysis. Along with the histogram plots showing the spectral shift of the fluorescence curve to the right after treatment with Mn, glutamate or the two together. Decrease in the spectral shift is observed in samples incubated with riluzole. M1 represents the percentage of cells positive for the DCFH-DA dye. (B) Graphical representation of fluorescence intensities from three separate experiments. Results are presented as mean ± SE; Mn vs. controla - p < 0.05; G vs. controlb - n.s., not significant; Mn + G vs. controlc - p < 0.001; Mn vs. Mn + Gd - p < 0.001; G vs. Mn + Ge - p < 0.001; Mn vs. Mn + Rf - p < 0.05; G vs. G + Rg - n.s., not significant; Mn + G vs. Mn + G + Rh - p < 0.001. Experiments shown are the mean ± S.E. of three independent experiments.

3.4. Caspase 3 activity

In addition to ROS generation, both Mn and glutamate have also been reported to increase caspase 3 activity as part of the normal downstream apoptotic pathway (Budd et al., 2000; Roth and Garrick, 2003). Accordingly, studies were performed to determine whether the combined effect of Mn and glutamate would also stimulate caspase 3 activation beyond that measured with either agent alone. As illustrated in Fig. 3, Mn treatment alone produced an increase in caspase activity approximately 1.7-fold in neuronally differentiated P19 cells whereas glutamate treatment by itself elevated caspase activity almost 2.4 fold. The combined treatment of Mn plus glutamate produced approximately a 2.9 fold increase in caspase 3 activation again implying a partial additive effect when the two agents were combined. Because of the effect of riluzole on cell toxicity and ROS generation, studies were also conducted to determine whether it could similarly inhibit caspase 3 activation. As shown by the data in Fig. 3, riluzole was found to reduce Mn-induced caspase 3 activation essentially back to baseline under all three treatment conditions.

Fig. 3.

Effect of manganese, glutamate and/or riluzole on caspase-3 activity in neuronally differentiated P19 cells. Cells were treated with the Mn (0.3 mM), glutamate (G; 5 mM) and /or riluzole (R; 10 μM) for 18 hrs. Fifty microliters of the normalized lysate from each sample was added to the 96 well plates and incubated with 2X substrate working solution containing Z-DEVD-AMC substrate for 30 minutes at room temperature. Protein concentration for all the conditions was normalized. Fluorescence was measured using the CytofluorII™ Multiplate Reader with excitation set at 380 nm and emission set at 460 nm; Mn vs. control a - n.s., not significant; G vs. Controlb - n.s., not significant; Mn + G vs. controlc - p < 0.05; Mn vs. Mn + Rd - n.s., not significant; G vs. G + Re - p < 0.05; Mn +G vs. Mn + G + Rf - p < 0.05; Mn vs. Mn + Gh- n.s., not significant; G vs. Mn + Gg - n.s., not significant. Data shown are the mean ± S.E. of three independent experiments.

3.5. Increase in p-JNK

Both Mn and glutamate have previously been observed to promote activation of JNK as part of the apoptotic pathway leading to cell death (Hirata et al., 1998a; Liu et al., 2002; Tian et al., 2005) and therefore, studies were also performed to examine the combined actions of these neurotoxins on phosphorylation of this kinase. As demonstrated by the data presented in Fig. 4A and B, both Mn and glutamate treatment alone stimulated JNK activation greater than two-fold, whereas when combined, JNK phosphorylation was stimulated almost six fold again demonstrating an additive response of the two neurotoxins. As observed with ROS generation and caspase 3 activation, treatment of the neuronally differentiated P19 cells with riluzole significantly suppresses the increase in JNK phosphorylation for all three experimental conditions (Fig. 4A and B). In all cases, the magnitude of JNK activation observed was essentially equivalent to that seen with riluzole alone.

Fig. 4.

Western blots showing the effect of manganese, glutamate or riluzole or combination of the three on JNK phosphorylation in neuronally differentiated P19 cells. (A) Western blots showing the levels of phosphorylated JNK in differentiated P19 cells treated with the Mn (0.3 mM), glutamate (G; 5 mM) and /or riluzole (R; 10 μM) for 18 hrs.; GAPDH antibody was used as a loading control. (B) Graphical representation of band densities from four separate experiments. Results are presented as mean ± SE; Mn vs. controla- p < 0.05; Mn vs. Mn + Rb - n.s., not significant; G vs. controlc - p < 0.05; G vs. G + Rd - p < 0.05; Mn + G vs. controle - p < 0.001; Mn + G vs. Mn + G + Rf - p<0.001; Mn vs. Mn + Gg - p < 0.001; G vs. Mn + Gh - p < 0.05. Data shown are the mean ± S.E. of four independent experiments.

4. Discussion

Manganese is an essential divalent metal required for normal growth and development (Roth, 2006). Deficiencies of Mn in the human population do not exist as our daily consumption of foods greatly exceeds our normal requirement. In contrast, excess exposure to Mn is a major concern, although it is largely restricted to occupations in which high atmospheric levels are prevalent which include Mn miners, welders and those employed in the ferroalloy processing or related industrial settings. Besides the occupational consequence, manifestations of Mn toxicity are also seen in individuals with hepatic dysfunction as the liver is the major organ responsible for its elimination. Concern over the health effects of Mn in the atmosphere was raised with the impending use of MMT in gasoline to boost octane ratings as cities in which this gas additive was used exhibited increase levels of the metal (Zayed, 2001).

T1 weighted MRI images reveal that Mn is deposited to the greatest extent in the globus pallidus, an area of the brain that is presumed to be responsible for the major CNS associated symptoms (Kim, 2004). This is relevant to the in vivo actions of Mn since neurons in the globus pallidus receive glutamatergic input from the subthalamic nuclei (Plenz and Kital, 1999; Rouse et al., 2000). Glutamate is an excitatory neurotransmitter but in excess can lead to neuronal toxicity caused by an increase in intracellular Ca2+ initiated by binding of glutamate to its ionotropic receptor. The accumulated intracellular Ca2+ is subsequently taken up into the mitochondria via the Ca2+ uniporter where it is sequestered and provokes changes in mitochondrial membrane permeability ultimately leading to formation of ROS and possibly other intracellular cytotoxic signals (Luo et al., 1997). A similar mechanism involving mitochondrial degeneration has been proposed for the selective neurotoxic actions of Mn in neurons in the globus pallidus (Gunter et al., 2009; Spadoni et al., 2000). In addition, glutamate toxicity also involves activation of several kinases including ERK1/2, JNK and p38 (Grant et al., 2001; Wise et al., 2004). The involvement of these kinases in the toxic actions of glutamate is evidenced by the fact that inhibitors of ERK phosphorylation and p38 kinase activity prevent glutamate-induced cell death (Baldwin et al., 1999; Stanciu and DeFranco, 2002). Since studies in my lab (Roth, 2006) and others (Hirata et al., 1998a; Stanciu and DeFranco, 2002) have previously shown that Mn correspondingly stimulates phosphorylation of these kinases, it is reasonable to postulate that this process can potentially contribute to the combined cytotoxic behavior of the two toxins. Since neurons in the globus pallidus receive glutaminergic input from the subthalamic nuclei and inhibitors of the glutamate receptors suppress Mn toxicity, a similar argument can be made for the selective impairment of neurons within the globus pallidus even though P19 cells are not GABAminergic.

Strongest evidence for glutamate to participate in the toxic actions of Mn comes from the in vivo studies demonstrating that the noncompetitive NMDA receptor antagonist, MK-801, is capable of blocking lesions produced by Mn (Brouillet et al., 1993; Xu et al., 2010). This is further demonstrated by the protective actions of the anti-glutamatergic drug, riluzole, which was similarly shown to effectively prevent Mn toxicity in rats (Deng et al., 2009). There are several potential mechanisms by which Mn and glutamate can interact to promote cell death in the globus pallidus which include 1) similar cytotoxic actions of glutamate and Mn (Gunter et al., 2009; Kannurpatti et al., 2000), 2) Mn inhibition of glutamate transport leading to increase synaptic levels of glutamate (Erikson and Aschner, 2002; Hazell and Norenberg, 1997) and 3) increased uptake of Mn in pallidal neurons by activated glutamate channels (Kannurpatti et al., 2000). Although these findings suggest a link between glutamate and Mn in promoting cell death, there has never been a study that directly analyzes the consequences of the combined actions of the two neurotoxins on apoptotic signaling processes in cells.

4.1. Mn effect on apoptosis markers

As reported in this paper, both Mn and glutamate were shown to be cytotoxic to neuronally differentiated P19 cells. When the two neurotoxins were combined, cell death was enhanced as compared to treatment with either agent alone although the increase was less than additive in comparison to induction of a number of apoptotic signals measured which include ROS generation, caspase 3 activation and JNK phosphorylation. These data are consistent with both toxins functioning to independently promote apoptosis. The fact that these apoptotic signals measured are additive support the hypothesis that glutamate input into from the subthalamic nuclei may potentially stimulate the neurotoxic actions of Mn in the globus pallidus and therefore, may partially explain the selective adverse effects of Mn observed within these neurons as compared to other areas of the CNS that may also accumulate Mn.

4.2. Effect of riluzole on Mn toxicity

Consistent with the potentiation of Mn toxicity by glutamate is the recent report demonstrating that the anti-glutamatergic drug, riluzole, is capable of suppressing the neurotoxic actions of Mn in rats (Deng et al., 2009). The major mechanisms by which riluzole is presumed to function clinically is via its inhibition of glutamate release ( Martin et al., 1993) though other mechanisms have been proposed for its selective pharmacological actions (Koh et al., 1999). In the case of Mn treatment alone, as described in this manuscript, protection by riluzole against P19 cell death, clearly, cannot be caused by inhibition of glutamate release. The data presented suggest that suppression of Mn-induced cell toxicity by riluzole, most likely, can be attributed to its direct antioxidant properties as emphasized by reduced ROS levels and several downstream apoptotic signals. This is evidenced by the fact that riluzole inhibition of these Mn-induced apoptotic signals occurred in the absence of glutamate as well as in combination of both agents. The extent of protection in each case was independent of the condition employed as the degree of cell death observed was essentially the same for all treatments in the presence of riluzole. These data clearly demonstrate that inhibition of apoptotic signaling by riluzole is likely responsible for its protective actions against Mn toxicity previously reported in rat brain (Deng et al., 2009).

4.3. Conclusion

In summary, the data presented in this paper are significant in that it identifies, for the first time, shared apoptotic signaling processes between glutamate and Mn which are likely responsible for the selective neurotoxic actions of Mn in the globus pallidus. These findings help explain the preferential behavior of Mn in this area of the basal ganglia as neurons in the globus pallidus selectively receive glutamatergic input from axonal projections originating within the subthalamic nuclei. These studies further describe the suppression of the Mn-induced apoptotic signals by the anti-glutamatergic agent, riluzole, which account, at least in part, for its neuroprotective actions previously reported in rats (Deng et al., 2009). Results of these studies confirm that riluzole, independent of its effect on glutamate release, can protect against Mn toxicity by suppressing ROS activation and the subsequent down-stream oxidative stress signals.

-

>

Glutamate facilitates Mn-induced apoptosis in neuronally differentiated P19 cells.

-

>

Apoptotic signals ROS, caspase 3 and JNK increase when the two agents are combined.

-

>

The anti-glutamatergic drug, riluzole, inhibits the apoptotic signals and cell death.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported in part by NIEHS grants R21ES015762 and RC1 ES0810301. We acknowledge the assistance of the Flow Cytometry Facility in the School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, University at Buffalo.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Akamatsu K, Shibata MA, Ito Y, Sohma Y, Azuma H, Otsuki Y. Riluzole induces apoptotic cell death in human prostate cancer cells via endoplasmic reticulum stress. Anticancer Res. 2009;29:2195–2204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin M, Mergler D, Larribe F, Belanger S, Tardif R, Bilodeau L, Hudnell K. Bioindicator and exposure data for a population based study of manganese. Neurotoxicology. 1999;20:343–353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brouillet EP, Shinobu L, McGarvey U, Hochberg F, Beal MF. Manganese injection into the rat striatum produces excitotoxic lesions by impairing energy metabolism. Exp Neurol. 1993;120:89–94. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1993.1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budd SL, Tenneti L, Lishnak T, Lipton SA. Mitochondrial and extramitochondrial apoptotic signaling pathways in cerebrocortical neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:6161–6166. doi: 10.1073/pnas.100121097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen WC, Cheng HH, Huang CJ, Chou CT, Liu SI, Chen IS, Hsu SS, Chang HT, Huang JK, Jan CR. Effect of riluzole on Ca2+ movement and cytotoxicity in Madin-Darby canine kidney cells. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2006;25:461–469. doi: 10.1191/0960327106het641oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chun HS, Lee H, Son JH. Manganese induces endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress and activates multiple caspases in nigral dopaminergic neuronal cells, SN4741. Neurosci Lett. 2001;316:5–8. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(01)02341-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng Y, Xu Z, Xu B, Tian Y, Xin X, Deng X, Gao J. The protective effect of riluzole on manganese caused disruption of glutamate-glutamine cycle in rats. Brain Res. 2009;1289:106–117. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng Y, Xu Z, Xu B, Xu D, Tian Y, Feng W. The Protective Effects of Riluzole on Manganese-Induced Disruption of Glutamate Transporters and Glutamine Synthetase in the Cultured Astrocytes. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s12011-012-9365-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desole MS, Sciola L, Delogu MR, Sircana S, Migheli R. Manganese and 1-methyl-4-(2′-ethylpheny1)-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine induce apoptosis in PC12 cells. Neurosci Lett. 1996;209:193–196. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(96)12645-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desole MS, Sciola L, Delogu MR, Sircana S, Migheli R, Miele E. Role of oxidative stress in the manganese and 1-methyl-4-(2′-ethylphenyl)-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine-induced apoptosis in PC12 cells. Neurochem Int. 1997;31:169–176. doi: 10.1016/s0197-0186(96)00146-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Mchichi B, Hadji A, Vazquez A, Leca G. p38 MAPK and MSK1 mediate caspase-8 activation in manganese-induced mitochondria-dependent cell death. Cell death and differentiation. 2007;14:1826–1836. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erikson K, Aschner M. Manganese causes differential regulation of glutamate transporter (GLAST) taurine transporter and metallothionein in cultured rat astrocytes. Neurotoxicology. 2002;23:595–602. doi: 10.1016/s0161-813x(02)00012-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erikson KM, Syversen T, Steinnes E, Aschner M. Globus pallidus: a target brain region for divalent metal accumulation associated with dietary iron deficiency. J Nutr Biochem. 2004;15:335–341. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2003.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estevez AG, Stutzmann JM, Barbeito L. Protective effect of riluzole on excitatory amino acid-mediated neurotoxicity in motoneuron-enriched cultures. Eur J Pharmacol. 1995;280:47–53. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(95)00186-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant ER, Errico MA, Emanuel SL, Benjamin D, McMillian MK, Wadsworth SA, Zivin RA, Zhong Z. Protection against glutamate toxicity through inhibition of the p44/42 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway in neuronally differentiated P19 cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 2001;62:283–296. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(01)00665-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunasekar PG, Kanthasamy AG, Borowitz JL, Isom GE. NMDA receptor activation produces concurrent generation of nitric oxide and reactive oxygen species: implication for cell death. J Neurochem. 1995;65:2016–2021. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1995.65052016.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunter TE, Gavin CE, Gunter KK. The case for manganese interaction with mitochondria. Neurotoxicology. 2009;30:727–729. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2009.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazell AS, Norenberg MD. Manganese decreases glutamate uptake in cultured astrocytes. Neurochem Res. 1997;22:1443–1447. doi: 10.1023/a:1021994126329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirata Y, Adachi K, Kiuchi K. Activation of JNK pathway and induction of apoptosisby manganese in PC12 cells. J Neurochem. 1998a;71:1607–1615. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.71041607.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirata Y, Adachi K, Kiuchi K. Phosphorylation and activation of p70 S6 kinase by manganese in PC12 cells. Neuroreport. 1998b;9:3037–3040. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199809140-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogins J, Crawford DC, Zorumski CF, Mennerick S. Excitotoxicity triggered by neurobasal culture medium. PLoS One. 2011;6:e25633. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones-Villeneuve EM, Rudnicki MA, Harris JF, McBurney MW. Retinoic acid-induced neural differentiation of embryonal carcinoma cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1983;3:2271–2279. doi: 10.1128/mcb.3.12.2271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaal EC, Vlug AS, Versleijen MW, Kuilman M, Joosten EA, Bar PR. Chronic mitochondrial inhibition induces selective motoneuron death in vitro: a new model for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurochem. 2000;74:1158–1165. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.741158.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kannurpatti SS, Joshi PG, Joshi NB. Calcium sequestering ability of mitochondria modulates influx of calcium through glutamate receptor channel. Neurochem Res. 2000;25:1527–1536. doi: 10.1023/a:1026602100160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan AJ, Wall B, Ahlawat S, Green C, Schiff D, Mehnert JM, Goydos JS, Chen S, Haffty BG. Riluzole enhances ionizing radiation-induced cytotoxicity in human melanoma cells that ectopically express metabotropic glutamate receptor 1 in vitro and in vivo. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:1807–1814. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JH, Mun YJ, Chun HJ, Jeon KS, Kim YO, Woo WH. Effect of biphenyl dimethyl dicarboxylate on the humoral immunosuppression by ethanol. Int J Immunopharmacol. 2000;22:905–913. doi: 10.1016/s0192-0561(00)00053-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y. High signal intensities on T1-weighted MRI as a biomarker of exposure to manganese. Ind Health. 2004;42:111–115. doi: 10.2486/indhealth.42.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y, Kim JM, Kim JW, Yoo CI, Lee CR, Lee JH, Kim HK, Yang SO, Chung HK, Lee DS, Jeon B. Dopamine transporter density is decreased in parkinsonian patients with a history of manganese exposure: what does it mean? Mov Disord. 2002;17:568–575. doi: 10.1002/mds.10089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh JY, Kim DK, Hwang JY, Kim YH, Seo JH. Antioxidative and proapoptotic effects of riluzole on cultured cortical neurons. J Neurochem. 1999;72:716–723. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0720716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latchoumycandane C, Anantharam V, Kitazawa M, Yang Y, Kanthasamy A, Kanthasamy AG. Protein kinase Cdelta is a key downstream mediator of manganese-induced apoptosis in dopaminergic neuronal cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;313:46–55. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.078469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee ES, Sidoryk M, Jiang H, Yin Z, Aschner M. Estrogen and tamoxifen reverse manganese-induced glutamate transporter impairment in astrocytes. J Neurochem. 2009;110:530–544. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06105.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee YH, Lin CH, Hsu LW, Hu SY, Hsiao WT, Ho YS. Roles of ionotropic glutamate receptors in early developing neurons derived from the P19 mouse cell line. J Biomed Sci. 2003;10:199–207. doi: 10.1007/BF02256055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu HN, Giasson BI, Mushynski WE, Almazan G. AMPA receptor-mediated toxicity in oligodendrocyte progenitors involves free radical generation and activation of JNK, calpain and caspase 3. J Neurochem. 2002;82:398–409. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.00981.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Y, Bond JD, Ingram VM. Compromised mitochondrial function leads to increased cytosolic calcium and to activation of MAP kinases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:9705–9710. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.18.9705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin D, Thompson MA, Nadler JV. The neuroprotective agent riluzole inhibits release of glutamate and aspartate from slices of hippocampal area CA1. Eur J Pharmacol. 1993;250:473–476. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(93)90037-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pal PK, Samii A, Calne DB. Manganese neurotoxicity: a review of clinical features,imaging and pathology. Neurotoxicology. 1999;20:227–238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plenz D, Kital ST. A basal ganglia pacemaker formed by the subthalamic nucleus and external globus pallidus. Nature. 1999;400:677–682. doi: 10.1038/23281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth JA. Homeostatic and toxic mechanisms regulating manganese uptake, retention, and elimination. Biol Res. 2006;39:45–57. doi: 10.4067/s0716-97602006000100006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth JA, Feng L, Walowitz J, Browne RW. Manganese-induced rat pheochromocytoma (PC12) cell death is independent of caspase activation. J Neurosci Res. 2000;61:162–171. doi: 10.1002/1097-4547(20000715)61:2<162::AID-JNR7>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth JA, Garrick MD. Iron interactions and other biological reactions mediating the physiological and toxic actions of manganese. Biochem Pharmacol. 2003;66:1–13. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(03)00145-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth JA, Horbinski C, Higgins D, Lein P, Garrick MD. Mechanisms of manganese-induced rat pheochromocytoma (PC12) cell death and cell differentiation. Neurotoxicology. 2002;23:147–157. doi: 10.1016/s0161-813x(01)00077-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouse ST, Marino MJ, Bradley SR, Awad H, Wittmann M, Conn PJ. Distribution and roles of metabotropic glutamate receptors in the basal ganglia motor circuit: implications for treatment of Parkinson’s disease and related disorders. Pharmacol Ther. 2000;88:427–435. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(00)00098-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrantz N, Blanchard DA, Mitenne F, Auffredou MT, Vazquez A, Leca G. Manganese induces apoptosis of human B cells: caspase-dependent cell death blocked by bcl-2. Cell Death Differ. 1999;6:445–453. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spadoni F, Stefani A, Morello M, Lavaroni F, Giacomini P, Sancesario G. Selective vulnerability of pallidal neurons in the early phases of manganese intoxication. Exp Brain Res. 2000;135:544–551. doi: 10.1007/s002210000554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanciu M, DeFranco DB. Prolonged nuclear retention of activated extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase promotes cell death generated by oxidative toxicity or proteasome inhibition in a neuronal cell line. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:4010–4017. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104479200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storch A, Burkhardt K, Ludolph AC, Schwarz J. Protective effects of riluzole on dopamine neurons: involvement of oxidative stress and cellular energy metabolism. J Neurochem. 2000;75:2259–2269. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0752259.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stredrick DL, Stokes AH, Worst TJ, Freeman WM, Johnson EA, Lash LH, Aschner M, Vrana KE. Manganese-induced cytotoxicity in dopamine-producing cells. Neurotoxicology. 2004;25:543–553. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2003.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian H, Zhang QG, Zhu GX, Pei DS, Guan QH, Zhang GY. Activation of c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase 3 is mediated by the GluR6.PSD-95.MLK3 signaling module following cerebral ischemia in rat hippocampus. Brain Res. 2005;1061:57–66. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchino A, Noguchi T, Nomiyama K, Takase Y, Nakazono T, Nojiri J, Kudo S. Manganese accumulation in the brain: MR imaging. Neuroradiology. 2007;49:715–720. doi: 10.1007/s00234-007-0243-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise K, Manna S, Barr J, Gunasekar P, Ramesh G. Activation of activator protein-1 DNA binding activity due to low level manganese exposure in pheochromocytoma cells. Toxicol Lett. 2004;147:237–244. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2003.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu LY, Wang Y, Jin B, Zhao T, Wu HT, Wu Y, Fan M, Wang XM, Zhu LL. The role of hypoxia in the differentiation of P19 embryonal carcinoma cells into dopaminergic neurons. Neurochem Res. 2008;33:2118–2125. doi: 10.1007/s11064-008-9728-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu B, Xu ZF, Deng Y. Effect of manganese exposure on intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis and expression of NMDA receptor subunits in primary cultured neurons. Neurotoxicology. 2009;30:941–949. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2009.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Z, Jia K, Xu B, He A, Li J, Deng Y, Zhang F. Effects of MK-801, taurine and dextromethorphan on neurotoxicity caused by manganese in rats. Toxicol Ind Health. 2010;26:55–60. doi: 10.1177/0748233709359275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshizumi M, Eisenach JC, Hayashida K. Riluzole and gabapentinoids activate glutamate transporters to facilitate glutamate-induced glutamate release from cultured astrocytes. Eur J Pharmacol. 2012;677:87–92. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2011.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zayed J. Use of MMT in Canadian gasoline: health and environment issues. Am J Ind Med. 2001;39:426–433. doi: 10.1002/ajim.1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]