Highlights

► We characterized the mutator phenotype of a very early onset rectal cancer. ► High frequency of C:G>T:A or G:C>A:T transitions at methylated CpG sites was found. ► A somatic TDG mutation was found associated with TDG expression loss in the tumor. ► 1st in vivo evidence that TDG acts against deleterious 5-methylcytosine deamination.

Keywords: TDG, Colorectal cancer, CMMR-D syndrome, MMR repair, Supermutator

Abstract

Cells with DNA repair defects have increased genomic instability and are more likely to acquire secondary mutations that bring about cellular transformation. We describe the frequency and spectrum of somatic mutations involving several tumor suppressor genes in the rectal carcinoma of a 13-year-old girl harboring biallelic, germline mutations in the DNA mismatch repair gene PMS2. Apart from microsatellite instability, the tumor DNA contained a number of C:G → T:A or G:C → A:T transitions in CpG dinucleotides, which often result through spontaneous deamination of cytosine or 5-methylcytosine. Four DNA glycosylases, UNG2, SMUG1, MBD4 and TDG, are involved in the repair of these deamination events. We identified a heterozygous missense mutation in TDG, which was associated with TDG protein loss in the tumor. The CpGs mutated in this patient's tumor are generally methylated in normal colonic mucosa. Thus, it is highly likely that loss of TDG contributed to the supermutator phenotype and that most of the point mutations were caused by deamination of 5-methylcytosine to thymine, which remained uncorrected owing to the TDG deficiency. This case provides the first in vivo evidence of the key role of TDG in protecting the human genome against the deleterious effects of 5-methylcytosine deamination.

1. Introduction

Genomic DNA is constantly exposed to endogenous and exogenous damaging agents. As failure to repair this damage leads to mutations, rearrangements and other deleterious events that can cause cellular malfunction, all living organisms have evolved efficient DNA repair pathways that safeguard their genomes. Two key guardians of genomic integrity are mismatch repair (MMR) and base excision repair (BER). MMR addresses mismatches and small insertion/deletion loops that arise during replication and that would give rise to point- and frameshift mutations if left unrepaired. BER removes predominantly aberrant DNA bases arising through hydrolysis and oxidation in non-replicating DNA.

Malfunction of both MMR and BER are associated with cancer. Heterozygous (monoallelic) germline mutations in the MMR genes MSH2, MSH6, MLH1, and PMS2 are linked to the autosomal-dominant Lynch syndrome [1], which predisposes primarily to colorectal and endometrial cancers [2]. Lynch syndrome tumors lose the wild type MMR allele through somatic mutations or LOH. However, there are also rare cases of individuals with biallelic germline mutations in one of the MMR genes. These are referred to as constitutional MMR-deficiency (CMMR-D) patients, who develop mainly childhood hematological malignancies and/or brain tumors, as well as very early onset colorectal cancers. Most CMMR-D patients display also signs reminiscent of neurofibromatosis type 1, such as café au lait spots [3].

The hallmark of MMR-deficient colorectal cancers is microsatellite instability (MSI), which is manifested as an accumulation of somatic frameshift mutations in runs of mono- or dinucleotides known as microsatellites. In these tumors, frameshift mutations are frequently found in the coding sequences of genes involved in the control of growth regulation (TGFßRII, IGF2R, BAX) or DNA repair (MSH3, MSH6), the dysregulation of which promotes tumorigenesis. Frameshift mutations were described also in APC [4], a key tumor suppressor gene in the Wnt signaling pathway, the malfunction of which has been linked to the initiation of colorectal tumorigenesis [5].

The link between BER deficiency and cancer is currently limited to the autosomal-recessive MUTYH-associated polyposis syndrome (MAP) [6,7]. In resting DNA, 8-oxoguanines (Go) are removed by OGG1, but failure to remove this aberrant base prior to replication gives rise to Go/A mispairs. MUTYH glycosylase removes the mispaired adenine and the repair polymerases insert a C opposite the Go, which provides OGG1 with a second chance at repair. Germline mutations in MUTYH result in G → T transversion mutations, which are a hallmark of MAP.

To date, no cancer-associated mutations have been identified in other BER genes. This might seem unexpected, given that spontaneous deamination of cytosine to uracil represents a frequent occurrence. However, the removal of uracil from DNA can be accomplished by at least four glycosylases: UNG2, SMUG1, MBD4 or TDG [8]. With this degree of redundancy, inactivation of a single gene would not be expected to have phenotypic consequences. In contrast, deamination of 5-methylcytosine gives rise to T/G mispairs, which have been shown to be repaired by BER to C/G with the help of MBD4 or TDG. We have been unable to detect MBD4 activity in extracts of human 293T cells depleted of TDG [9] and it thus appears likely that the latter enzyme is principally responsible for the repair of 5-methylcytosine deamination.

In this report, we describe a patient with biallelic germline PMS2 mutations who developed a very early onset rectal cancer with a particular supermutator phenotype. Intriguingly, although the analysis of the tumor DNA revealed MSI at noncoding and intronic repeats, frameshift mutations were not detected in several analyzed tumor suppressor genes. In contrast, an exceedingly high number of somatic C:G → T:A or G:C → A:T transitions were identified in these genes, many in CpG dinucleotides.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Microsatellite instability (MSI) analysis

Five quasi-monomorphic mononucleotide repeat markers, i.e. BAT-26, BAT-25, NR-21, NR-24, and MONO-27 were investigated to assess MSI employing a fluorescence-based pentaplex-PCR assay (Ingenetix, Vienna, Austria) according to the manufacturer's recommendations.

2.2. Immunohistochemical analysis of mismatch repair proteins and of the base excision repair protein TDG

Sections of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tumors were immunostained with primary monoclonal antibodies against the MMR proteins MSH2 (Ab NA27, Calbiochem), MSH6 (Ab 610919, BD), MLH1 (Ab 551091, BD), and PMS2 (Ab 556415, BD), as described previously [10]. An affinity-purified rabbit anti human TDG antibody was kindly provided by Dr. P. Schär (University of Basel, Switzerland) and tissue immunostaining was performed using the protocol described in [10]. This latter antibody was diluted 1:1500, and incubated with tissue sections overnight at 4 °C.

2.3. Mutation analysis in tumor tissue

DNA was extracted from fresh frozen (−70 °C) colorectal tissues using Genomic DNA Purification Kit (Gentra Systems, Minneapolis, MI, USA) according to manufacturer's recommendations. Somatic mutation analysis of the APC, KRAS, TP53, BRAF, CTNNB1, MUTYH genes, as well as examination of MSI and MLH1 promoter hypermethylation were performed as described previously [11]. The MLH1 and MSH2 genes were pre-screened for mutations by denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis (DGGE) as described in [12] and PCR fragments showing an aberrant DGGE profile were subsequently sequenced to determine the underlying mutation. The MSH6 and NF1 genes were analyzed by direct sequencing of all exons amplified directly from tumor DNA using published primers [13,14]. Equally, the BER genes, UNG2, SMUG1, MBD4 and TDG, were sequenced directly from tumor DNA (primers for amplification of BER genes are listed in Supplementary Table 1). All mutations found in tumor DNA were analyzed also in DNA from the corresponding normal mucosa to exclude their presence in the germline.

Mutant allele-specific PCR amplification [15] was used to assess whether two somatic stop mutations identified in APC exon 6 were located in trans or in cis. A forward primer (5′ GTTTCTTGTTTTATTTTAGT 3′) with the terminal 3′ nucleotide specific for the first mutation (c.646C>T, p.R216*), and a reverse primer (5′ CTACCTATTTTTATACCCAC 3′) positioned downstream of the second mutation (c.694C>T, p.R232*), were used for PCR and subsequent sequencing of the generated PCR product.

DNA from three additional CMMR-D patients (see Section 3) was isolated from paraffin-embedded tumor tissue using Puregene Tissue Kit (Gentra Systems, Minneapolis, MI, USA) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. For somatic mutation analysis in these tumors, APC (specified in Table 2) was amplified using primers published in [16], and CTNNB1 exon 3 was amplified with the following primers: forward, 5′ CAATCTACTAATGCTAATACTGTTTCG 3′; reverse, 5′ GTTCTCAAAACTGCATTCTGACTTTC 3′. The resulting PCR products were sequenced in both directions.

Table 2.

Comparison of somatic mutations found in the tumor of Patient 1 and in tumors of three unrelated PMS2−/− patients.

| Patients | MSIa | Somatic mutationsb |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| APCc (∼7000 bp) | APC-MCRd (∼700 bp) | CTNNB1e (∼300 bp) | ||

| Patient 1 | 5/5 | 8 (6x C>T/G>A, 1×T>G, 1×A>G) | 1 (1×C>T) | 1(1×C>T) |

| Patient 2 | 4/5 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Patient 3f | 5/5 | n.a. | 0 | 0 |

| Patient 4 | 0/5 | 1 (c.4666dupA) | 0 | n.a. |

MSI; microsatellite instability. n.a.; not analyzed. The number of unstable markers per analyzed markers is given.

The number of somatic mutations in the analyzed region is given (type of mutation in parenthesis).

APC; analysis of the entire coding and flanking intronic sequences of exons 1–14 and the first 5 kb of exon 15. This region contained all somatic APC mutations found in tumor DNA of Patient 1.

APC-MCR; analysis of the mutation cluster region (MCR) only, in exon 15 of APC.

CTNNB1; analysis of the critical exon 3 and flanking intronic sequences.

Only a limited amount of tumor DNA was available from Patient 3. Therefore, only the APC MCR and the CTNNB1 exon 3 were sequenced.

All cycle sequencing reactions were performed using the BigDye Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) according to manufacturer's instructions, and sequences were analyzed with the 3130 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystem, Foster City, CA, USA).

All mutations are described according to the recommendations of the Human Genome Variation Society (http://www.hgvs.org/mutnomen/). The TDG reference sequence NM_003211.4 was from GenBank. The reference sequences used for the other analyzed genes are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Somatic mutations found in tumor DNA of Patient 1.

| APC GenBank Ref.Seq NM_000038.4 | CTNNB1 GenBank Ref.Seq NM_001904.3 | NF1 GenBank Ref.Seq NM_000267.2 | MLH1 GenBank Ref.Seq NM_000249.3 | MSH6 GenBank Ref.Seq NM_000179.2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| c.646C>T, p.R216* | c.59C>T, p.A20V | c.862G>A, p.V288M | c.1490G>A, p.R497Q | c.2195G>A, p.R732Q |

| c.694C>T, p.R232* | c.1154G>A, p.R385H | c.2040C>T, p.C680C | ||

| c.730-15A>G | c.5601C>T, p.I1867I | |||

| c.1242C>T, p.R414R | c.8245C>T, p.L2749F | |||

| c.1312+4T>G | ||||

| c.3313C>T, p.R1105W | ||||

| c.4097C>T, p.A1366V | ||||

| c.4901C>T, p.P1634L |

Transitions affecting CpG dinucleotides are shown in bold.

2.4. Bisulfite genomic sequencing analysis

Methylation analysis of the TDG promoter (cancer tissue from Patient 1) and of four CpG dinucleotides located in the APC exon 6 and in the MLH1 exons 13 and 18 (cancer tissue from Patient 1 and a colonic mucosa sample from a control subject) was performed by bisulfite genomic sequencing. Sodium bisulfite conversion of genomic DNA was carried out with the EpiTect Bisulfite kit (Qiagen, Hombrechtikon, Switzerland) according to the manufacturer's instructions. PCR products were cloned using the InsTAclone PCR Cloning kit (Fermentas, St. Leon-Rot, Germany), and individual clones were subjected to sequencing. Primers used for the PCR reactions are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

2.5. Germline PMS2 and NF1 mutation analysis

Blood samples were obtained from the patient and her parents after they provided written informed consent. A previously described RNA-based mutation analysis protocol was used to identify the germline mutations in PMS2 [17]. To confirm the presence of an identified nonsense mutation at the genomic level, PMS2 exon 11 was amplified from genomic DNA with published primers [18] and subsequently sequenced. PMS2 multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MLPA) analysis was used to confirm a multi-exon deletion. MLPA was performed with SALSA kits P008-A1 and P008-B1 (MRC-Holland, Amsterdam, The Netherlands), according to the manufacturer's instructions using a set of six reference DNA samples each containing two copies of PMS2- and two copies of PMS2CL-specific sequences [19]. The identified PMS2 germline mutations are described in accordance with the recommendations of the Human Genome Variation Society (http://www.hgvs.org/mutnomen/) using NM_000535 as the reference sequence.

The NF1 germline mutation analysis included NF1 cDNA sequencing as described in [20] and MLPA analysis using SALSA kits P081-B1 and P082-B2 (MRC-Holland, Amsterdam, The Netherlands).

3. Results

3.1. Unique mutational phenotype in a colorectal cancer

Within the framework of a large study of somatic mutations in colorectal tumors [11], a consecutive series of 103 anonymized, apparently sporadic colorectal cancers were examined for somatic mutations in the APC, KRAS, TP53, BRAF, CTNNB1, and MUTYH genes, LOH at the APC locus, MSI, and MLH1 promoter methylation. One rectal cancer (of a patient hereafter referred to as Patient 1) stood out from this series because of a unique mutational pattern characterized by microsatellite instability (MSI+) and nine somatic alterations, eight in APC and one in CTNNB1 (Table 1). Of note, none of the alterations in these two genes were frameshift mutations, although more than half of the mutations found in other sporadic MSI+ colorectal cancers of this series were of this type [11]. Furthermore, most (7/9) of the mutations in this rectal cancer were C:G → T:A or G:C → A:T transitions, six affecting CpG dinucleotides (Table 1). Since the tumor was MSI+ but MLH1 promoter hypermethylation – a possible underlying cause of sporadic MMR deficiency [5] – was not found, a germline mutation in one of the MMR genes was suspected to be responsible for the phenotype. We therefore carried out mutational analysis of the MMR genes MLH1, MSH2 and MSH6 in colorectal tissue DNA. (At this stage of the study, blood-derived DNA was not available, and PMS2 was not routinely investigated since its involvement in Lynch syndrome was considered rare and its sequencing was problematic [21]). This analysis uncovered three further C:G → T:A or G:C → A:T transitions (2 missense and 1 silent) at CpG dinucleotides in MLH1 and MSH6 (Table 1). However, as these mutations were absent from the DNA of non-neoplastic tissue, they were excluded as the underlying germline mutations.

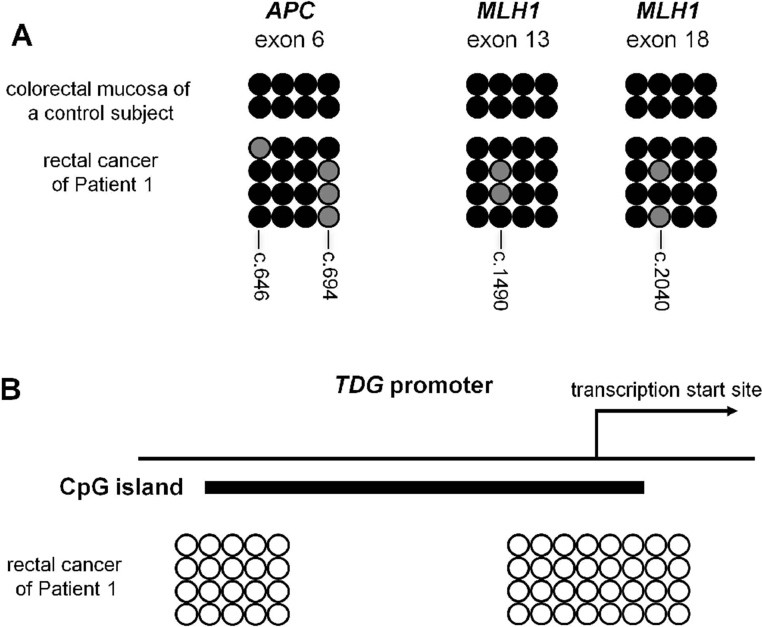

The peculiarity of this case prompted us to obtain the consent of the local ethics committee for further investigation and subsequently to request additional information from the clinicians. This showed that the tumor sample was derived from a teenage patient, who developed rectal cancer at the age of 13 years. This phenotype was reminiscent of constitutional mismatch repair deficiency (CMMR-D) syndrome that is frequently caused by biallelic PMS2 mutations. This gene was thus thoroughly investigated (see below). Meanwhile, tumor DNA was also examined for mutations in NF1, a known somatic target of CMMR-D induced mutations [22]. This revealed four additional C:G → T:A or G:C → A:T transitions, three of which were at CpG dinucleotides (Table 1). In summary, in this rectal cancer, we identified a total of 16 single-nucleotide substitutions in the ∼34,000 nucleotides sequenced from 10 different genes (exons and intron-exon boundaries). Twelve of these substitutions (75%) affected Cs at CpG dinucleotides. Of note, four CpG sites found mutated in APC exon 6 and MLH1 exons 13 and 18 were analyzed exemplarily by bisulfite genomic sequencing and were all found to be methylated in the colonic mucosa sample of a normal control (Supplemental Fig. 1A) (see Section 4).

3.2. Identification of compound heterozygous germline PMS2 mutations in Patient 1

The complete clinical history of the 13-year-old girl affected by the rectal cancer was obtained from our clinical collaborators. She was admitted to hospital because of recurrent episodes of fever, pain in the lower abdomen and diarrhea. Magnetic resonance examination revealed a pseudotumor of the left ovary. Surgical exploration revealed a voluminous abscess, along with several cysts of the left ovary. Unexpectedly, tumor infiltration of the recto-sigmoid junction and the left ovary from a rectal cancer was also identified. Unilateral adnexectomy was performed, and the histopathologic examination confirmed the infiltration of an undifferentiated carcinoma. Resection of the rectal tumor was performed one month later, and the tumor was classified as pT3N2Mx with moderate cell differentiation. Cycles of adjuvant therapy with capecitabine and oxaliplatin followed by cetuximab and irinotecan were initiated, but the treatment was interrupted after four cycles because of lack of clinical improvement. A course of palliative radiotherapy (45 Gy/15 days) was administered thereafter and tumor growth was temporarily suppressed.

The patient had no family history of colorectal cancer and did not have colorectal tumors other than the rectal cancer. However, two café au lait maculae on the lower back were identified during the follow-up by the clinical geneticist. This finding supported our suspicion of CMMR-D syndrome. Since this disorder is often associated with biallelic germline mutations of the MMR gene PMS2 [3], sections of the rectal cancer were immunostained with anti-PMS2 antibodies along with antibodies against the other MMR proteins. Immunohistochemistry showed loss of PMS2 protein in the cancer as well as in the corresponding normal mucosa, whereas MLH1, MSH2 and MSH6 were expressed normally (Fig. 1). This staining pattern is unmistakably associated with a constitutive PMS2 gene defect which was confirmed by the identification of compound heterozygosity for two deleterious germline PMS2 mutations in the patient. Direct cDNA sequencing detected heterozygous loss of exons 12, 13 and 14 (r.2007_2445del439) in PMS2 transcripts of the patient and MLPA analysis confirmed a genomic deletion affecting these three exons (c.2007-?_2445+?del). Furthermore, the c.1687C>T mutation leading to the premature stop codon p.Arg563* was identified by cDNA sequencing and confirmed by sequencing of exon 11 from genomic DNA. Analysis of parental DNA confirmed that the two pathogenic mutations were located in trans.

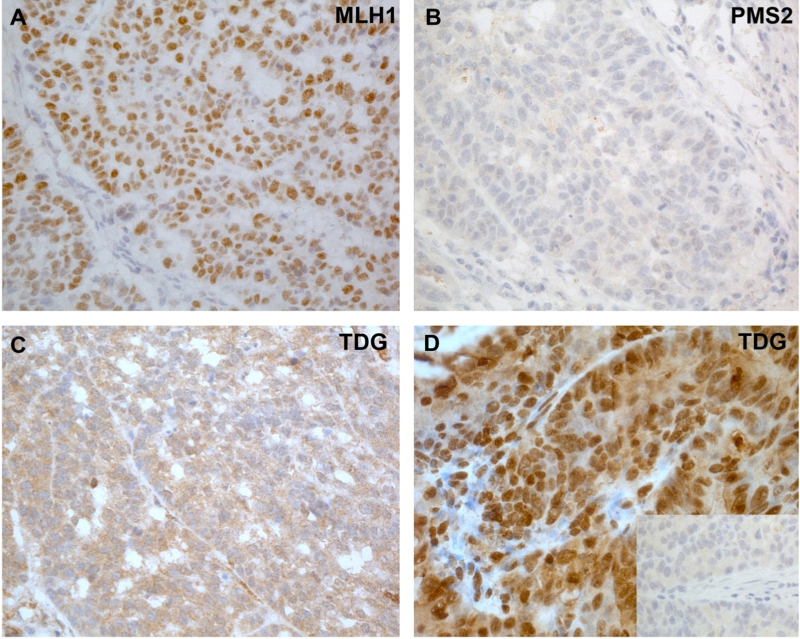

Fig. 1.

Immunohistochemical staining of colon cancers with antibodies against MLH1, PMS2 and TDG. (A–C): Colon cancer of Patient 1; (D): colon cancer from an unrelated CMMR-D patient with a homozygous germline PMS2 mutation (Patient 2). MLH1 expression in the tumor cells was normal (A), while its heterodimeric partner PMS2 was absent in the colon cancer of Patient 1 (B). PMS2 was absent also in normal stromal cells (B) and in the normal mucosa (not shown). (C) In the same cancer, expression of the DNA repair enzyme TDG was markedly reduced or completely absent in the nuclei. (The cytoplasmic staining may either represent background, or residual expression of TDG in this cellular compartment.) (D) TDG was normally expressed in the colon cancer of the unrelated CMMR-D patient (Patient 2) used as positive control. Inset: staining of this cancer with TDG pre-immune serum (negative control).

Since café au lait spots and other neurofibromatosis features in CMMR-D patients may result from postzygotic mosaic NF1 mutations detectable in blood lymphocytes [23], NF1 was also investigated by cDNA sequencing and MLPA, but this gene resulted to be wild type.

Unfortunately, the radiotherapy gave only a short remission of the disease, and the patient died 17 months later. Presently, the patient's parents are healthy in their forties. The only younger (now 13-year-old) sister has not been examined yet, but she has not manifested symptoms related to CMMR-D syndrome. The maternal father died at 53 years of age of leukemia and the paternal mother underwent hysterectomy with adnexectomy at 40 years because of cervical carcinoma (she is still alive at 61). No further cancer cases were reported in the family.

3.3. Identification of a heterozygous TDG mutation and concomitant TDG expression loss in the neoplastic tissue

The mutational phenotype (i.e., an excess of C:G → T:A or G:C → A:T transitions and absence of frameshift alterations) in the MSI+ rectal cancer of this PMS2−/− CMMR-D patient was intriguing. To our knowledge, only one case with an inferred biallelic PMS2 germline mutation and a high rate of somatic mutations has been described to date [24]. This teenage male patient presented with astrocytoma, lymphoma, three metachronous carcinomas and multiple adenomas in the colon. All analyzed tumors of this patient were MSI+ and frameshift mutations at short mononucleotide repeats were also detected in exons of TGFßRII, MSH3, MSH6 or E2F4. In addition, 11 somatic mutations in the APC and TP53 genes were detected in the three colorectal carcinomas (one in the first, four in the second and six in the third). Four of these 11 mutations were frameshifts and seven were single-nucleotide substitutions, of which three were C:G → T:A or G:C → A:T transitions and only two were at CpG dinucleotides. This case indicates that colorectal cancers in CMMR-D patients with biallelic PMS2 germline mutation may have a high frequency of somatic mutations in their tumors, but do not render evidence for a preponderance of C:G → T:A or G:C → A:T mutations seen in our patient (Patient 1). Therefore, we analyzed colorectal cancers of three additional PMS2−/− CMMR-D patients, who had been previously recruited and studied in our laboratories. Mutational analysis of APC and CTNNB1 genes was performed in their tumor DNA (Table 2).

The first patient (Patient 2) developed a colon adenocarcinoma at the age of 12 years and was a homozygous carrier of a truncating PMS2 mutation (unpublished data). The genotype and phenotype of Patient 3 were described previously [25]. Finally, we have studied the tumor tissue of a patient (Patient 4) who developed colon cancer at the age of 15. Although this tumor did not display instability at the microsatellites investigated to date, the patient is assumed to be CMMR-D due to a biallelic PMS2 germline mutation since the tumor (and the normal colorectal mucosa) showed PMS2 expression loss by immunostaining in spite of normal expression of the other three MMR proteins. Patient 4 died shortly after the cancer diagnosis, and blood was not available to perform PMS2 germline mutation analysis. Comparing the number of mutations per sequenced nucleotides in the PMS2-deficient colorectal cancers of the four CMMR-D patients, that of Patient 1 showed a far higher frequency of somatic genetic alterations (Table 2). In fact, only a single alteration, an APC frameshift mutation (c.4666dupA), was detected in the tumor of Patient 4, while no somatic sequence changes were found in tumors of Patients 2 and 3.

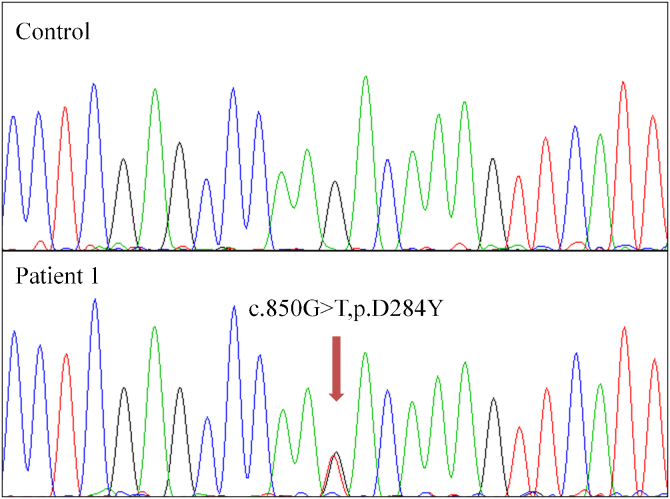

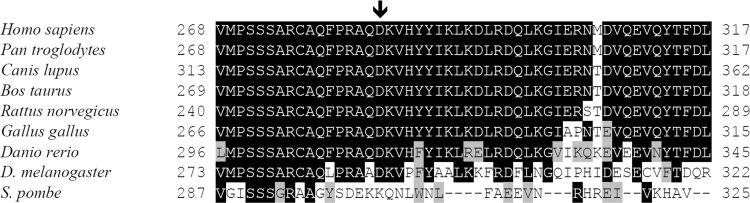

The striking preponderance of C:G → T:A or G:C → A:T transitions in the somatic mutation spectrum of the rectal cancer of Patient 1 prompted us to investigate whether a defect in one of the four uracil DNA glycosylases, UNG2, SMUG1, MBD4, and TDG could explain this observation. Mutational analysis of these genes in the tumor DNA revealed a heterozygous substitution c.850G>T in TDG, which was not present in DNA of non-neoplastic tissue (Fig. 2). This substitution resulted in a non-synonymous amino acid change (p.D284Y) within the catalytic core of the enzyme (residues 117–300). This aspartate residue appears to have a regulatory function and is not present in non-vertebrate Mug DNA glycosylases (Supplemental Fig. 2) [26]. Several in silico tools, i.e. Polyphen [27], SIFT [28] and Grantham [29], predicted this variant to be “deleterious”.

Fig. 2.

Sequencing electropherograms of TDG in the DNA of Patient 1. Upper panel: sequence of the TDG gene from non-neoplastic tissue containing solely the wild type allele. Lower panel: sequence of TDG in tumor DNA, showing the heterozygous somatic mutation p.D284Y.

Therefore, we performed immunohistochemical studies with a polyclonal anti-TDG antibody in the tumor of Patient 1 and, as a control, the tumor of CMMR-D Patient 2 (see Table 2). The immunostaining showed markedly reduced nuclear TDG staining in tumor cells of Patient 1 (Fig. 1) suggesting that the mutation leads to instability of the protein. A mutation in the second TDG allele was not found, and analysis of the microdissected tumor DNA failed to reveal LOH at the TDG locus (copy number variations at this locus were also not found using Human CGH 3 × 720 K Whole-Genome Tiling v3.0 Array). As it was recently reported that TDG inactivation may promote DNA hypermethylation [30,31], we considered the possibility that TDG haploinsufficiency may do the same, which might have resulted in silencing of the wild type allele in the neoplastic tissue. We therefore carried out bisulfite genomic sequencing analysis at the TDG promoter covering CpG sites shown to be hypermethylated in multiple myeloma cell lines [32]. However, this promoter region was found to be unmethylated in this tumor (Supplemental Fig. 1B), which implies that TDG expression from the second allele must have been lost by an alternative mechanism, possibly a second hit that escaped detection by the methods used in this study.

No alteration was found in the other three uracil DNA glycosylases, UNG2, SMUG1, MBD4, and real-time PCR analysis showed that expression levels of these genes in the tumor tissue are comparable to those in the normal mucosa of the patient (primers for real-time PCR of BER genes are listed in Supplementary Table 1).

4. Discussion

We describe here a CMMR-D patient (Patient 1) with a constitutive PMS2−/− defect, whose rectal cancer harbored, along with a high degree of MSI, an unexpectedly large number of nucleotide substitutions in five of the ten tumor suppressor genes or proto-oncogenes analyzed. The estimated rate of non-synonymous exonic mutations in this cancer (11 mutations in 28,547 bp exonic nucleotides analyzed = 385/Mb) was at least 67-fold higher than that of MSI-tumors (3.1–5.8/Mb according to a whole exome next generation sequencing study [33]) and ∼8-fold higher than that of MSI+ tumors (when considering an ∼8-times higher rate of non-frameshift mutations in MSI+ vs. MSI-tumors [34]). Moreover, we also observed a striking preponderance of C:G → T:A and G:C → A:T transitions, 86% (12/14) of which were located at CpG dinucleotides. This phenotype was observed neither in colorectal cancers of three other patients with a constitutive PMS2−/− defect, nor in sporadic colorectal cancers analyzed by next generation sequencing [33].

A high somatic APC mutation rate was previously described in colorectal cancers of an inferred CMMR-D patient [24], but the tumor mutation spectrum in this case showed no obvious bias for C:G → T:A and G:C → A:T transitions. Similarly, the NF1 mutation spectrum of several MLH1−/−, MSH2−/− or MSH6−/− colon cancer cell lines, primary colorectal cancers and mouse embryonic fibroblasts [22] differed from that found in this gene in the rectal cancer of Patient 1. Wang and colleagues found only a single G:C → A:T transition in the MSH2−/− cancer cell line LoVo at a CpG dinucleotide among 10 somatic mutations, five of which were frameshifts). We therefore conclude that the constitutional MMR malfunction in our PMS2−/− Patient 1 was not the sole DNA repair defect responsible for the supermutator phenotype observed in her rectal cancer.

The MMR system processes DNA base–base mismatches and small insertion–deletion loops arising during DNA replication through the concerted action of the four essential MMR proteins MSH2, MSH6, MLH1 and PMS2 [35]. This system acts as a backup of the proofreading activity of DNA polymerases and, by directing the repair process to the nascent strand, improves the fidelity of DNA replication by up to two orders of magnitude [36]. Because insertion–deletion loops are not addressed by the polymerase proofreading activity, the impact of MMR loss is easily detected as MSI in the DNA of MMR-deficient cells. Importantly, in Lynch syndrome patients, MSI is present only in tumor cell DNA, due to somatic inactivation of the wild type allele [37]. In contrast, CMMR-D patients are born with a biallelic, germline inactivation of one of the MMR genes, and therefore have a MMR defect in all cells [38,39]. Indeed, in a previous study [40], frameshifts in microsatellites were found more frequently in the DNA of non-neoplastic tissues of a PMS2−/− deficient individual than in the corresponding normal tissues of a heterozygous PMS2+/− individual and a PMS2+/+ control subject.

In contrast to MMR, BER functions predominantly in non-replicating DNA [41]. The repair process is initiated by one of several DNA glycosylases, which are highly substrate-specific. In the case of cytosine deamination, the product of the reaction, uracil, can be removed from DNA by one of four enzymes: UNG2, SMUG1, MBD4 or TDG. UNG2 is the major effector of uracil repair, whereas SMUG1 is believed to act as a broad-specificity back-up, especially in non-replicating chromatin [42,43].

5-Methylcytosine deaminates to thymine and it has been postulated that methylated CpGs are mutagenic hotspots because thymines arising through deamination cannot be distinguished from other thymines in DNA. However, 5-methylcytosine deamination generates a T/G mispairs in DNA and it could be shown that these are efficiently reverted to C/G by BER [44,45], which is initiated by TDG [46]. A decade later, MBD4, a second enzyme capable of removing T from T/G mispairs was identified [47,48]. The identification of an apparently pathogenic somatic mutation in TDG that is linked with substantially lower levels of the protein in the tumor of Patient 1, and the striking predominance of C:G → T:A and G:C → A:T transitions at CpG dinucleotides in the tumor DNA strongly supports the hypothesis that TDG is the key enzyme protecting our genome from mutagenesis at methylated CpGs. When we studied the methylation status of some of the CpGs found to be mutated in the tumor of Patient 1 in a colonic mucosa sample of a normal individual, cytosines in all the investigated CpG sites were found to be methylated. Thus, it is highly likely that the observed point mutations were caused by deamination of 5-methylcytosine to thymine, which remained uncorrected owing to the TDG deficiency in this tumor.

Aberrant activation of the Wnt signaling pathway is one of the key early events in the transformation of colonic epithelium, and APC mutations are among the most common aberrations detected in colorectal cancers (reviewed in [49]). The tumor DNA of Patient 1 was no exception in this regard: it contained eight somatic APC alterations, two of which (c.646C>T, p.R216* and c.694C>T, p.R232*) were clearly pathogenic and on different alleles (as determined by mutant allele-specific PCR amplification and subsequent sequencing of the generated PCR product (data not shown) and as confirmed by bisulfite genomic sequencing analysis of APC exon 6 (see Supplemental Fig. 1A). Like most mutations identified in the rectal tumor of Patient 1, they were C:G → T:A transitions, and thus might have arisen as a result of TDG deficiency, assuming that, within the context of this tumor, TDG inactivation preceded that of APC. This does not seem unreasonable, given that the TDG mutation was a G → T transversion, a characteristic footprint of oxidative DNA damage and/or MMR deficiency, rather than a C → T transition typical of deamination.

This is to our knowledge the first study describing a somatic mutation of TDG in a human tumor. This mutational event was presumably selected for during early tumorigenesis in cells with a high mutation rate caused by a constitutive MMR defect, but, since TDG was not inactivated in tumors of three other CMMR-D patients, the loss of this enzyme is likely not an obligate step in the malignant transformation of the colonic epithelium of such patients. However, TDG inactivation might have contributed to the aggressive phenotype of the rectal tumor in Patient 1, given that a loss of this activity renders the tumor DNA more prone to acquire mutations at CpG sites. In any case, this tumor offered the unique opportunity to study TDG loss in vivo. Our finding that TDG loss leads to C → T transitions at methylated CpGs in vivo demonstrates that this enzyme indeed protects our genomes against deleterious effects of 5-methylcytosine deamination, as predicted more than 20 years ago [45].

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

We thank Primo Schär for kindly providing a polyclonal anti-TDG antibody and Ritva Haider for performing the IHC analyses. The work was supported by the project (Ministry of Health, Czech Republic) for conceptual development of research organization 00064203 (University Hospital Motol, Prague,Czech Republic). The generous support by the Austrian Science Fond [“Fonds zur Förderung der wissenschaftlichen Forschung” (FWF), grant no. P21172-B12 to AW and KW], the Swiss National Science Foundation (grants no. 310030B-133123 to JJ and 31003A-122186 to GM), and the Cancer League Switzerland (grant no. KFS-02739-02-2011 to MM) is also gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.dnarep.2012.04.004.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary Fig. I.

Bisulfite genomic sequencing at CpG sites of APC and MLH1 coding regions (A) and at the CpG island encompassing the TDG transcription start site (B). Each row of circles shows the methylation status of a cloned target sequence. Open circles: unmethylated CpG; black or gray filled circles: methylated or mutated CpGs, respectively. In panel A, the positions of the APC and MLH1 CpG dinucleotides that underwent somatic transitions in the tumor of Patient 1 are indicated below the columns of circles. Note that the two APC mutations are found in different clones, indicating that they are located in trans which was also confirmed by allele-specific PCR (see Section 4).

Supplementary Fig. II.

Evolutionary conservation of TDG. Alignment of the amino acid sequence of TDG from different organisms flanking the position of the somatic mutation p.D284Y identified in Patient 1. Identical amino acids are in black boxes, similar ones in grey boxes. The site of the mutation is indicated by an arrow.

References

- 1.Aaltonen L.A., Peltomaki P., Leach F.S., Sistonen P., Pylkkanen L., Mecklin J.P., Jarvinen H., Powell S.M., Jen J., Hamilton S.R. Clues to the pathogenesis of familial colorectal cancer. Science. 1993;260:812–816. doi: 10.1126/science.8484121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lynch H.T., de la Chapelle A. Hereditary colorectal cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003;348:919–932. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra012242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wimmer K., Etzler J. Constitutional mismatch repair-deficiency syndrome: have we so far seen only the tip of an iceberg? Hum. Genet. 2008;124:105–122. doi: 10.1007/s00439-008-0542-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huang J., Papadopoulos N., McKinley A.J., Farrington S.M., Curtis L.J., Wyllie A.H., Zheng S., Willson J.K., Markowitz S.D., Morin P., Kinzler K.W., Vogelstein B., Dunlop M.G. APC mutations in colorectal tumors with mismatch repair deficiency. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1996;93:9049–9054. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.17.9049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kinzler K.W., Vogelstein B. Lessons from hereditary colorectal cancer. Cell. 1996;87:159–170. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81333-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Al-Tassan N., Chmiel N.H., Maynard J., Fleming N., Livingston A.L., Williams G.T., Hodges A.K., Davies D.R., David S.S., Sampson J.R., Cheadle J.P. Inherited variants of MYH associated with somatic G:C → T:A mutations in colorectal tumors. Nat. Genet. 2002;30:227–232. doi: 10.1038/ng828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheadle J.P., Sampson J.R. MUTYH-associated polyposis—from defect in base excision repair to clinical genetic testing. DNA Repair. 2007;6:274–279. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2006.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gallinari P., Jiricny J. A new class of uracil-DNA glycosylases related to human thymine-DNA glycosylase. Nature. 1996;383:735–738. doi: 10.1038/383735a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fischer F., Baerenfaller K., Jiricny J. 5-Fluorouracil is efficiently removed from DNA by the base excision and mismatch repair systems. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1858–1868. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Truninger K., Menigatti M., Luz J., Russell A., Haider R., Gebbers J.O., Bannwart F., Yurtsever H., Neuweiler J., Riehle H.M., Cattaruzza M.S., Heinimann K., Schar P., Jiricny J., Marra G. Immunohistochemical analysis reveals high frequency of PMS2 defects in colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:1160–1171. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.01.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vasovcak P., Pavlikova K., Sedlacek Z., Skapa P., Kouda M., Hoch J., Krepelova A. Molecular genetic analysis of 103 sporadic colorectal tumours in czech patients. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e24114. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu Y., Nystrom-Lahti M., Osinga J., Looman M.W., Peltomaki P., Aaltonen L.A., de la Chapelle A., Hofstra R.M., Buys C.H. MSH2 and MLH1 mutations in sporadic replication error-positive colorectal carcinoma as assessed by two-dimensional DNA electrophoresis. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 1997;18:269–278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Han S.S., Cooper D.N., Upadhyaya M.N. Evaluation of denaturing high performance liquid chromatography (DHPLC) for the mutational analysis of the neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) gene. Hum. Genet. 2001;109:487–497. doi: 10.1007/s004390100594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu Y., Berends M.J., Mensink R.G., Kempinga C., Sijmons R.H., van Der Zee A.G., Hollema H., Kleibeuker J.H., Buys C.H., Hofstra R.M. Association of hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer-related tumors displaying low microsatellite instability with MSH6 germline mutations. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1999;65:1291–1298. doi: 10.1086/302612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Old J.M. Detection of mutations by the amplification refractory mutation system (ARMS) In: Mathew Ch.G., editor. Protocols in Human Molecular Genetics. The Humana Press Inc.; 1992. pp. 77–84. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miyoshi Y., Ando H., Nagase H., Nishisho I., Horii A., Miki Y., Mori T., Utsunomiya J., Baba S., Petersen G. Germ-line mutations of the APC gene in 53 familial adenomatous polyposis patients. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1992;89:4452–4456. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.10.4452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Etzler J., Peyrl A., Zatkova A., Schildhaus H.U., Ficek A., Merkelbach-Bruse S., Kratz C.P., Attarbaschi A., Hainfellner J.A., Yao S., Messiaen L., Slavc I., Wimmer K. RNA-based mutation analysis identifies an unusual MSH6 splicing defect and circumvents PMS2 pseudogene interference. Hum. Mutat. 2008;29:299–305. doi: 10.1002/humu.20657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van der Klift H.M., Tops C.M., Bik E.C., Boogaard M.W., Borgstein A.M., Hansson K.B., Ausems M.G., Gomez G.E., Green A., Hes F.J., Izatt L., van Hest L.P., Alonso A.M., Vriends A.H., Wagner A., van Zelst-Stams W.A., Vasen H.F., Morreau H., Devilee P., Wijnen J.T. Quantification of sequence exchange events between PMS2 and PMS2CL provides a basis for improved mutation scanning of Lynch syndrome patients. Hum. Mutat. 2010;31:578–587. doi: 10.1002/humu.21229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.A. Wernstedt, E. Valtorta, F. Armelao, R. Togni, S. Girlando, M. Baudis, K. Heinimann, L. Messiaen, N. Staehli, J. Zschocke, G. Marra, K. Wimmer, Improved MPLA analysis identifies a deleterious PMS2 allele generated by recombination with crossover between PMS2 and PMS2CL, Genes Chromosomes and Cancer (2012) (in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Messiaen L., Wimmer K. Mutation analysis of the NF1 gene by cDNA-based sequencing of the coding region. In: Cunha K.S.G., Geller M., editors. Advances in Neurofibromatosis Research. Nova Science Publisher; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 21.De Vos M., Hayward B.E., Picton S., Sheridan E., Bonthron D.T. Novel PMS2 pseudogenes can conceal recessive mutations causing a distinctive childhood cancer syndrome. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2004;74:954–964. doi: 10.1086/420796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang Q., Montmain G., Ruano E., Upadhyaya M., Dudley S., Liskay R.M., Thibodeau S.N., Puisieux A. Neurofibromatosis type 1 gene as a mutational target in a mismatch repair-deficient cell type. Hum. Genet. 2003;112:117–123. doi: 10.1007/s00439-002-0858-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alotaibi H., Ricciardone M.D., Ozturk M. Homozygosity at variant MLH1 can lead to secondary mutation in NF1, neurofibromatosis type I and early onset leukemia. Mutat. Res. 2008;637:209–214. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2007.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miyaki M., Nishio J., Konishi M., Kikuchi-Yanoshita R., Tanaka K., Muraoka M., Nagato M., Chong J.M., Koike M., Terada T., Kawahara Y., Fukutome A., Tomiyama J., Chuganji Y., Momoi M., Utsunomiya J. Drastic genetic instability of tumors and normal tissues in Turcot syndrome. Oncogene. 1997;15:2877–2881. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kratz C.P., Niemeyer C.M., Juttner E., Kartal M., Weninger A., Schmitt-Graeff A., Kontny U., Lauten M., Utzolino S., Radecke J., Fonatsch C., Wimmer K. Childhood T-cell non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, colorectal carcinoma and brain tumor in association with cafe-au-lait spots caused by a novel homozygous PMS2 mutation. Leukemia. 2008;22:1078–1080. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2405008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cortazar D., Kunz C., Saito Y., Steinacher R., Schar P. The enigmatic thymine DNA glycosylase. DNA Repair (Amst.) 2007;6:489–504. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2006.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ramensky V., Bork P., Sunyaev S. Human non-synonymous SNPs: server and survey. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:3894–3900. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkf493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ng P.C., Henikoff S. Predicting deleterious amino acid substitutions. Genome Res. 2001;11:863–874. doi: 10.1101/gr.176601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grantham R. Amino acid difference formula to help explain protein evolution. Science. 1974;185:862–864. doi: 10.1126/science.185.4154.862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cortazar D., Kunz C., Selfridge J., Lettieri T., Saito Y., MacDougall E., Wirz A., Schuermann D., Jacobs A.L., Siegrist F., Steinacher R., Jiricny J., Bird A., Schar P. Embryonic lethal phenotype reveals a function of TDG in maintaining epigenetic stability. Nature. 2011;470:419–423. doi: 10.1038/nature09672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cortellino S., Xu J., Sannai M., Moore R., Caretti E., Cigliano A., Le C.M., Devarajan K., Wessels A., Soprano D., Abramowitz L.K., Bartolomei M.S., Rambow F., Bassi M.R., Bruno T., Fanciulli M., Renner C., Klein-Szanto A.J., Matsumoto Y., Kobi D., Davidson I., Alberti C., Larue L., Bellacosa A. Thymine DNA glycosylase is essential for active DNA demethylation by linked deamination-base excision repair. Cell. 2011;146:67–79. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Peng B., Hurt E.M., Hodge D.R., Thomas S.B., Farrar W.L. DNA hypermethylation and partial gene silencing of human thymine- DNA glycosylase in multiple myeloma cell lines. Epigenetics. 2006;1:138–145. doi: 10.4161/epi.1.3.2938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sjoblom T., Jones S., Wood L.D., Parsons D.W., Lin J., Barber T.D., Mandelker D., Leary R.J., Ptak J., Silliman N., Szabo S., Buckhaults P., Farrell C., Meeh P., Markowitz S.D., Willis J., Dawson D., Willson J.K., Gazdar A.F., Hartigan J., Wu L., Liu C., Parmigiani G., Park B.H., Bachman K.E., Papadopoulos N., Vogelstein B., Kinzler K.W., Velculescu V.E. The consensus coding sequences of human breast and colorectal cancers. Science. 2006;314:268–274. doi: 10.1126/science.1133427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Timmermann B., Kerick M., Roehr C., Fischer A., Isau M., Boerno S.T., Wunderlich A., Barmeyer C., Seemann P., Koenig J., Lappe M., Kuss A.W., Garshasbi M., Bertram L., Trappe K., Werber M., Herrmann B.G., Zatloukal K., Lehrach H., Schweiger M.R. Somatic mutation profiles of MSI and MSS colorectal cancer identified by whole exome next generation sequencing and bioinformatics analysis. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e15661. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kunkel T.A., Erie D.A. DNA mismatch repair. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2005;74:681–710. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.74.082803.133243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jiricny J. The multifaceted mismatch-repair system. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2006;7:335–346. doi: 10.1038/nrm1907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Peltomaki P. Deficient DNA mismatch repair: a common etiologic factor for colon cancer. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2001;10:735–740. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.7.735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vilkki S., Tsao J.L., Loukola A., Poyhonen M., Vierimaa O., Herva R., Aaltonen L.A., Shibata D. Extensive somatic microsatellite mutations in normal human tissue. Cancer Res. 2001;61:4541–4544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang Q., Lasset C., Desseigne F., Frappaz D., Bergeron C., Navarro C., Ruano E., Puisieux A. Neurofibromatosis and early onset of cancers in hMLH1-deficient children. Cancer Res. 1999;59:294–297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Agostini M., Tibiletti M.G., Lucci-Cordisco E., Chiaravalli A., Morreau H., Furlan D., Boccuto L., Pucciarelli S., Capella C., Boiocchi M., Viel A. Two PMS2 mutations in a Turcot syndrome family with small bowel cancers. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2005;100:1886–1891. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.50441.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kunz C., Saito Y., Schar P. DNA Repair in mammalian cells: Mismatched repair: variations on a theme. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2009;66:1021–1038. doi: 10.1007/s00018-009-8739-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kavli B., Sundheim O., Akbari M., Otterlei M., Nilsen H., Skorpen F., Aas P.A., Hagen L., Krokan H.E., Slupphaug G. hUNG2 is the major repair enzyme for removal of uracil from U:A matches, U:G mismatches, and U in single-stranded DNA, with hSMUG1 as a broad specificity backup. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:39926–39936. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207107200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pettersen H.S., Sundheim O., Gilljam K.M., Slupphaug G., Krokan H.E., Kavli B. Uracil-DNA glycosylases SMUG1 and UNG2 coordinate the initial steps of base excision repair by distinct mechanisms. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:3879–3892. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brown T.C., Jiricny J. A specific mismatch repair event protects mammalian cells from loss of 5-methylcytosine. Cell. 1987;50:945–950. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90521-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wiebauer K., Jiricny J. In vitro correction of G.T mispairs to G.C pairs in nuclear extracts from human cells. Nature. 1989;339:234–236. doi: 10.1038/339234a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Neddermann P., Gallinari P., Lettieri T., Schmid D., Truong O., Hsuan J.J., Wiebauer K., Jiricny J. Cloning and expression of human G/T mismatch-specific thymine-DNA glycosylase. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:12767–12774. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.22.12767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bellacosa A. Role of MED1 (MBD4) gene in DNA repair and human cancer. J. Cell Physiol. 2001;187:137–144. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hendrich B., Hardeland U., Ng H.H., Jiricny J., Bird A. The thymine glycosylase MBD4 can bind to the product of deamination at methylated CpG sites. Nature. 1999;401:301–304. doi: 10.1038/45843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cattaneo E., Baudis M., Buffoli F., Bianco M.A., Zorzi F., Marra G. Springer Science + Business Media, LLC; 2010. Pathways and Crossroads to Colorectal Cancer, Pre-invasive Disease: Pathogenesis and Clinical Management. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.