Abstract

Context:

Dietary fructose induces unfavorable lipid alterations in animal models and adult studies. Little is known regarding metabolic tolerance of dietary fructose in children.

Objectives:

The aim of the study was to evaluate whether dietary fructose alters plasma lipids in children with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and in healthy children.

Design and Setting:

We performed a 2-d, crossover feeding study at the Inpatient Clinical Interaction Site of the Atlanta Clinical and Translational Science Institute at Emory University Hospital.

Participants and Intervention:

Nine children with NAFLD and 10 matched controls without NAFLD completed the study. We assessed plasma lipid levels over two nonconsecutive, randomly assigned, 24-h periods under isocaloric, isonitrogenous conditions with three macronutrient-balanced, consecutive meals and either: 1) a fructose-sweetened beverage (FB); or 2) a glucose beverage (GB) being consumed with each meal.

Main Outcome Measures:

Differences in plasma glucose, insulin, triglyceride, apolipoprotein B, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and nonesterified free fatty acid levels were assessed using mixed models and 24-h incremental areas under the time-concentration curve.

Results:

After FB, triglyceride incremental area under the curve was higher vs. after GB both in children with NAFLD (P = 0.011) and those without NAFLD (P = 0.027); however, incremental response to FB was greater in children with NAFLD than those without NAFLD (P = 0.019). For all subjects, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol declined in the postprandial and overnight hours with FB, but not with GB (P = 0.0006). Nonesterified fatty acids were not impacted by sugar but were significantly higher in NAFLD.

Conclusions:

The dyslipidemic effect of dietary fructose occurred in both healthy children and those with NAFLD; however, children with NAFLD demonstrated increased sensitivity to the impact of dietary fructose.

Pediatric nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is a chronic, obesity-associated liver disease that is the most common liver disease in children today. It is estimated to affect over 6 million children in the United States (1), and because of the obesity epidemic, its prevalence is increasing. NAFLD can result in end stage liver disease (2), but it is also associated with an increase in cardiovascular disease (CVD) and all-cause mortality (3–5).

Children with NAFLD have increased fasting triglycerides (TG) (6–9) and lower high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDLc) (8–10), a pattern strongly associated with increased CVD risk (11) and typical of insulin resistance syndromes. The presence of dyslipidemia in adolescents and children is particularly worrisome because dyslipidemia in youth predicts increased CVD risk in adulthood (12). Although children with NAFLD have not yet been followed long enough to know whether the dyslipidemia predicts increased cardiovascular events later in life, adults with NAFLD have increased mortality from cardiovascular events even after adjusting for the presence of metabolic syndrome (13). This suggests that a component of NAFLD increases atherosclerosis, independent of other known risk factors including obesity and central adiposity. Similar to other insulin-resistant states, patients with NAFLD typically have the combined pattern of dyslipidemia characterized by fasting and postprandial hypertriglyceridemia, low HDL, as well as smaller HDL and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) particles and accumulation of very LDL (VLDL) (14).

Fructose is a common nutrient in the diets of children [representing approximately 11% of calories for a typical U.S. adolescent (15)] in the United States and it has previously been reported to be associated with NAFLD severity in adults (16–18). Unlike glucose, fructose is metabolized in the liver in a first-pass process without being involved in the rate-limiting phosphofructokinase pathway. High fructose consumption has been shown to increase hepatic de novo lipogenesis within hours (19) and contributes to increased hepatic TG synthesis first via increased glycerol synthesis and second through increased formation of saturated fatty acids, primarily palmitate (20). In animal studies, a high fructose diet increases de novo lipogenesis, adiposity, plasma TG, hepatic fat content, and oxidative stress (21–24). Short-term feeding studies in adults indicate higher plasma TG levels, both fasting and postprandial when fructose is substituted for glucose (20, 25–29).

Despite the strong role of fructose consumption in hepatic steatosis and CVD risk as well as the high consumption of fructose-containing beverages (FB) among the pediatric population, studies on the effect of fructose in children are lacking. Improving our understanding of dietary contributors to cardiovascular risk could lead to a potential long-term prevention strategy of CVD in pediatric NAFLD. We hypothesized that in children with NAFLD, FB would exacerbate dyslipidemia seen in the postprandial and overnight periods and that this effect would not be seen in healthy weight, metabolically normal children. We undertook a 24-h feeding study of children with NAFLD and in matched overweight and normal weight non-NAFLD controls comparing FB to glucose beverages (GB) to assess this hypothesis.

Subjects and Methods

Study design

This was a randomized, double-blind, crossover 2-d feeding study. Two separate visits were designed to compare responses to meals with GB and to meals with isocaloric FB. This study was approved by the Emory and Children's Healthcare of Atlanta Institutional Review Board, and consent and assent (when applicable) were obtained for each subject before initiation of the study. The study was conducted at the Emory University Hospital Clinical Interaction Network site of the Atlanta Clinical and Translational Science Institute.

Subjects

A total of 20 children (age range, 11 to 18 yr) met eligibility criteria and attended both visits of the study. Subjects with NAFLD (confirmed by liver biopsy within the past 2 yr) were recruited from Emory Children's Center Liver Clinic, and non-NAFLD controls [defined as hepatic fat infiltration < 3% by magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS)] were recruited at the Emory Children's Center general pediatric clinics. Of the subjects with NAFLD, on liver biopsy, one subject had simple steatosis, seven had nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), and two had NASH with bridging fibrosis. Controls were matched by age, gender, and race/ethnicity to the children with NAFLD. Healthy controls were recruited regardless of weight and during screening were characterized as either normal weight (BMI < 85th percentile) or overweight/obese (BMI ≥ 85th percentile). Inclusion criteria included that they were healthy (without chronic illness including diabetes or need for daily medications), had normal alanine aminotransferase (ALT)/aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and negative magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for hepatic steatosis. Exclusion criteria for both groups included fever within the past 2 wk, pregnancy, inability to obtain an MRI, and renal insufficiency. One subject with NAFLD was excluded from the analysis due to incomplete blood collection.

Study methods

For each of two visits, subjects consumed a standardized meal consisting of 700 kcal and 78 g sugar the evening before the study and then fasted for 12 h before the initial baseline measurements. Subjects arrived at the inpatient research unit at 0700 h and had an iv placed for blood draws. Blood samples were drawn at 0800 h (baseline), 1 h after breakfast, and subsequently, every 2 h until the following morning except at 0400 h to allow the children to sleep. Standardized meals (50% carbohydrates, 30% fat, and 20% protein) were prepared in the metabolic kitchen of the research unit by the research nutritionist, with 33% of total estimated daily calories (1.3 × estimated needs using calculated basal metabolic rate, using the Harris Benedict formula) provided as an isocaloric, sugar-sweetened beverage containing either glucose or fructose. Meals were typical for children and included items such as scrambled eggs, a hamburger, tater tots, and green beans. The children were randomized to either glucose (as dextrose) beverages or fructose (granulated fructose dissolved in water) beverages at visit 1 and the other sugar at visit 2. For each subject, lunch was served 4 h after breakfast, and dinner was served 8 h after breakfast. Typical meal times for a subject were 0800 h (breakfast), 1200 h (lunch), and 1600 h (dinner), after which only ad lib water was allowed. A washout period of 5–14 d was included between the two study visits. Participants were instructed not to change dietary habits during the washout period.

Imaging

Each child underwent an MRI/MRS evaluation for hepatic lipid volume, typically during the first study visit. The hepatic lipid percentage of participants was calculated by MRS using our previously described methods (30, 31). In brief, after acquisition, water and lipid magnitude spectra were analyzed by determining the area under the curve corresponding to a user-defined frequency range surrounding the corresponding water/lipid peaks (water peak, 4.6 ppm; lipid peak, 1.3, 2.0 ppm). The integrated magnitude signals at each TE were fit to exponential T2 decay curves, whereby the equilibrium signal (M0) and the relaxation rate (R2 = 1/T2) were determined by least-squares approximation. Using M0 for water and lipid, the T2-corrected hepatic lipid fraction was calculated from the formula: %Hepatic Lipid = M0lipid/(M0lipid + M0water).

Lipids and clinical measurements

Blood samples were collected in EDTA tubes, protected from light, and transported on ice to the laboratory for immediate processing. The extra samples were stored at −80 C. All lipid measurements were performed by the Emory Lipid Research Laboratory, and lab specialists were blinded to all subject information during sample processing and analysis. Total cholesterol, TG, and glucose were determined by enzymatic methods using reagents from Beckman (Beckman Diagnostics, Fullerton, CA). LDL-cholesterol (LDLc) and HDLc were determined using homogeneous enzymatic assays (Sekisui Diagnostics, Exton, PA). Nonesterified fatty acids (NEFA) were measured by colorimetric methods using reagents from Wako Chemicals (Richmond, VA). Apolipoproteins (apo), insulin, and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) were measured using immunoturbidimetric methods (Sekisui Diagnostics). ALT and AST were performed by the clinical laboratory at Emory University Hospital.

Statistical analyses

Sample size calculation was determined based on the expected difference in TG area under the curve in the NAFLD group using previously reported data (28). We estimated that n = 6 would be necessary to attain a power of 0.80 to identify a true difference in TG level in response to fructose compared with glucose. Additional subjects were enrolled because the response to TG was expected to be lower in children and to allow for potential variability caused by NAFLD. Results were expressed as mean (se). Independent two-sample t tests were used for comparison between non-NAFLD and NAFLD groups. Paired sample t tests were conducted for comparison between two separate visits, and P values < 0.05 were considered significant. Missing data imputation methods were used for the small number of missing data points (<1%). Due to the lack of a linear pattern with the time points, if a patient had a missing value at a certain time point, the average change plus the average mean of the outcome at its adjacent time points was used to replace the missing data. For variables of plasma glucose, insulin, TG, apoB, and TG/apoB ratio, comparisons of 24-h response were made using the incremental area under the curve (IAUC) using the trapezoidal method and paired analysis comparing individual time points at baseline (0 h, fasting), postprandially (9 h, postmeal assessment), and the posttest fasting (23 h, fasting). Because the response variables were measured at multiple time points throughout the 24-h period, the linear mixed model analysis was used to compare the effects of the two different beverages as well as the influence of NAFLD disease. Specifically, a random intercept model was assumed for each individual to incorporate the within-subject correlation, and those random effects represent the influence of the repeated observations from the same subject. Homeostatic model assessment for insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) was calculated from insulin and glucose at fasting state [glucose (mg/dl)*insulin (μU/ml)/405] and entered into the mixed model to test the effect of insulin resistance on response to sugars.

Results

Clinical characteristics of the study population

Clinical characteristics of the two groups are described in Table 1. Non-NAFLD controls were matched to NAFLD subjects by age, gender, and race. In the control group, five subjects had a BMI ≥ 85th percentile for weight and gender, whereas five subjects were between the 5th and 85th percentiles. At baseline, subjects with NAFLD had increased BMI z-score (P = 0.003), hepatic lipid (P < 0.001), ALT (P < 0.001), AST (P < 0.001), total cholesterol (P = 0.022), apoB (P = 0.034), insulin (P = 0.001), HOMA-IR (P = 0.015), and hs-CRP (P = 0.008), compared with the non-NAFLD controls (Table 1). Although there was some intrasubject variability in the fasting levels, baseline clinical measurements were not significantly different between the two visits for subjects.

Table 1.

Baseline anthropomorphic and metabolic characteristics of study population

| Parameter | Non-NAFLD | NAFLD | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 10 | 9 | |

| Age (yr) | 13.8 (0.7) | 13.6 (0.9) | 0.834 |

| Male, n (%) | 9 (90.0) | 8 (88.9) | 0.937 |

| Hispanic, n (%) | 7 (70.0) | 6 (66.7) | 0.876 |

| BMI z-score | 1.0 (0.3) | 2.2 (0.1) | 0.003 |

| Hepatic fat (%) | 0.6 (0.4) | 21.3 (1.8) | <0.001 |

| ALT (IU/liter) | 23.8 (5.0) | 138.4 (25.2) | <0.001 |

| AST (IU/liter) | 26.7 (1.7) | 84.5 (17.2) | <0.001 |

| TC (mg/dl) | 157.3 (5.7) | 180.1 (10.8) | 0.022 |

| TG (mg/dl) | 99.6 (16.3) | 159.1 (25.8) | 0.063 |

| HDLc (mg/dl) | 37.5 (3.3) | 36.2 (2.1) | 0.757 |

| LDLc (mg/dl) | 100.4 (4.6) | 120.7 (10.0) | 0.073 |

| NEFA (mEq/liter) | 1.2 (0.1) | 1.5 (0.2) | 0.156 |

| apoB (mg/dl) | 73.8 (3.6) | 93.3 (7.9) | 0.034 |

| Glucose (mg/dl) | 102.4 (3.6) | 99.2 (6.8) | 0.678 |

| Insulin (μU/ml) | 9.6 (3.3) | 39.5 (9.3) | 0.001 |

| hs-CRP (mg/liter) | 0.5 (0.2) | 3.1 (1.1) | 0.008 |

| HOMA-IR | 2.4 (0.7) | 9.6 (2.4) | 0.015 |

Values are expressed as mean (se), unless described otherwise. Statistical significance is considered as P < 0.05, calculated by independent two-sample t test. HOMA-IR was calculated as: (glucose*insulin)/405. Statistically significant values are in bold. TC, Total cholesterol; apoB, apolipoprotein B.

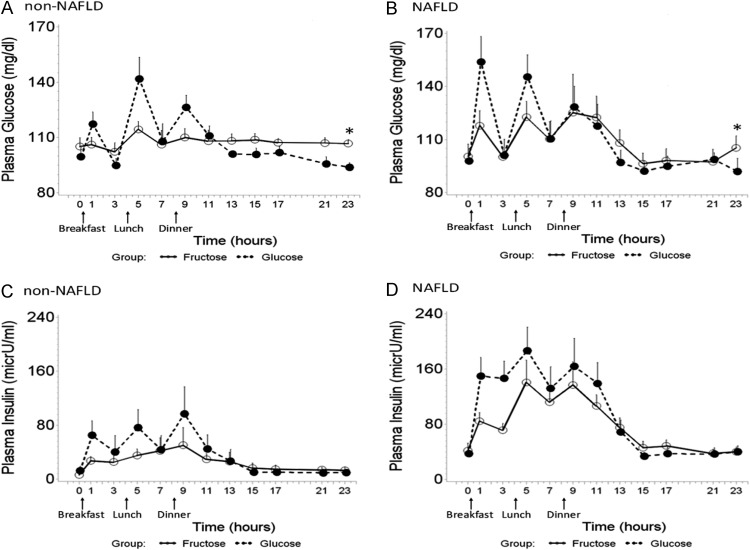

Effect on plasma glucose and plasma insulin

There was no difference in fasting plasma glucose between the two groups; however, NAFLD subjects had significantly higher insulin levels and higher HOMA-IR (Table 1), indicative of insulin resistance. The acute increases in glucose (Fig. 1, A and B) and insulin (Fig. 1, C and D) were greater after consumption of GB compared with FB for both NAFLD (P = 0.067) and non-NAFLD (P = 0.095) subjects. NAFLD patients exhibited a greater net increase, but the differences did not reach statistical significance, possibly due to the attenuated effect after dinner. At the end of the FB visit (time point of 23 h), fasting plasma glucose remained significantly higher, compared with that after 1-d GB feeding, for both NAFLD (P = 0.046) and non-NAFLD (P = 0.008) (Fig. 1, A and B). NAFLD participants had higher postprandial insulin response (24-h IAUC) compared with non-NAFLD controls during both the FB (mean ± se, 996.3 ± 189.8 vs. 451.6 ± 228.6; P = 0.028) and GB periods (mean ± se, 1444.9 ± 247.8 vs. 591.4 ± 239.9; P = 0.008). In non-NAFLD controls, postprandial insulin response (24-h IAUC) was significantly increased after GB compared with FB (mean ± se, 591.4 ± 239.9 vs. 451.6 ± 228.6; P = 0.021) (Fig. 1, C and D). There was no difference in insulin IAUC between the two periods for NAFLD subjects.

Fig. 1.

Twenty-four-hour mean plasma glucose (A and B) and insulin (C and D) concentration by consumption of three consecutive meals with FB (solid lines) and GB (dashed lines) in non-NAFLD controls (A and C) and pediatric NAFLD (B and D). Error bars stand for se. In non-NAFLD subjects, the 24-h IAUC of insulin was significantly increased after consuming GB compared with FB (mean ± se, 591.4 ± 239.9 vs. 451.6 ± 228.6; P = 0.021), but there was no significant difference in NAFLD. The 24-h IAUC of plasma insulin was significantly higher in NAFLD subjects compared with non-NAFLD controls during both fructose consumption (mean ± se, 996.3 ± 189.8 vs. 451.6 ± 228.6; P = 0.028) and glucose consumption (mean ± se, 1444.9 ± 247.8 vs. 591.4 ± 239.9; P = 0.008). Although the difference of 24-h IAUC of plasma glucose did not reach the statistical significance, at the end of FB feeding (time point of 23 h), fasting plasma glucose remained significantly higher compared with that after 1-d glucose beverage feeding, for both NAFLD (P = 0.046) and non-NAFLD (P = 0.008) (marked with asterisk).

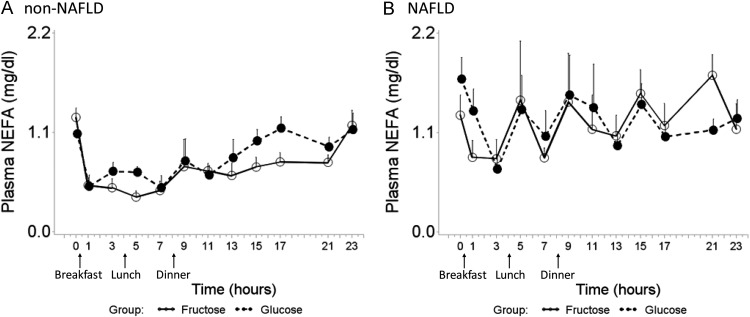

Effect on plasma NEFA

Fasting NEFA levels were not significantly different between the two groups (Table 1). In the non-NAFLD controls, NEFA levels decreased as expected after the breakfast-induced increase in plasma insulin and remained suppressed throughout the daytime hours, followed by a rise overnight during fasting (Fig. 2A). In NAFLD children, highly abnormal NEFA patterns were seen, including a lack of the expected sustained postprandial decrease (Fig. 2B) and overall increased levels compared with the healthy children (mixed model, beverage, P = 0.260; disease, P = 0.002; beverage × disease interaction, P = 0.558). No differences were seen between the FB and GB periods.

Fig. 2.

Twenty-four-hour plasma NEFA profile after consumption of FB (solid line) and GB (dashed line) in non-NAFLD controls (A) and pediatric NAFLD (B). Error bars stand for se. In NAFLD children, an overall increased level of plasma NEFA was observed compared with non-NAFLD controls, and there was no difference between FB and GB feeding period (mixed model, beverage, P = 0.260; disease, P = 0.002; beverage × disease interaction, P = 0.558).

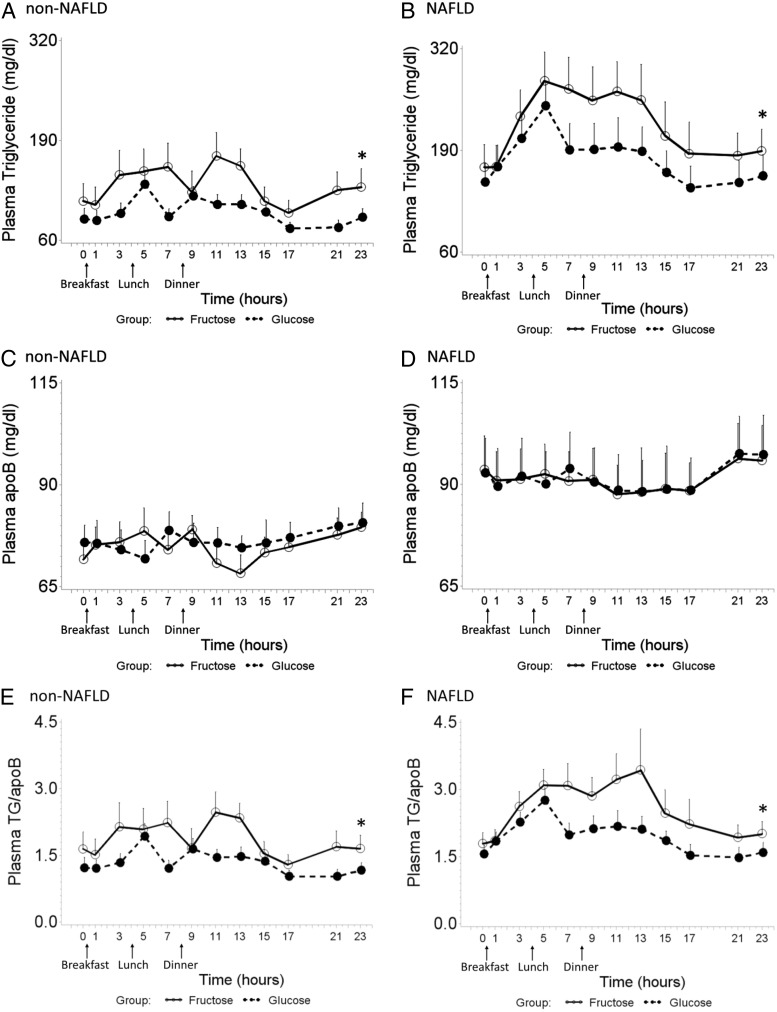

Effect on plasma TG

Children with NAFLD had higher fasting TG levels (Table 1) and had higher 24-h postprandial TG response during both FB (mean ± se, 1421.2 ± 267.1 vs. 622.4 ± 110.2; P = 0.019) and GB (mean ± se, 757.3 ± 136.5 vs. 325.7 ± 87.6; P = 0.015) periods compared with subjects without NAFLD; and the 24-h IAUC of plasma TG was significantly increased by consumption of FB in contrast to GB for both children with NAFLD (mean ± se, 1421.2 ± 267.1 vs. 757.3 ± 136.5; P = 0.011) and children without NAFLD (mean ± se, 622.4 ± 110.2 vs. 325.7 ± 87.6; P = 0.027), respectively (Fig. 3, A and B). The 24-h IAUC was not correlated with the baseline plasma TG concentration. The results of the 24-h IAUC calculation concurred with the result from mixed model (beverage, P < 0.0001; disease, P = 0.008; beverage × disease interaction, P = 0.396). When including baseline HOMA-IR into the mixed model, TG response was also affected by insulin resistance (beverage, P < 0.0001; disease, P = 0.050; HOMA-IR, P < 0.0001; beverage × disease interaction, P = 0.890). At the end of the visit (time point of 23 h), fasting plasma TG was significantly elevated after FB compared with GB for both NAFLD (P = 0.011) and non-NAFLD (P = 0.005) subjects (Fig. 3, A and B).

Fig. 3.

Twenty-four-hour TG (A and B), apoB (C and D), TG/apoB (E and F) profile during consumption of FB and GB in non-NAFLD controls (A, C, and E) and pediatric NAFLD (B, D, and F). Error bars stand for se. A and B, The 24-h IAUC of plasma TG was significantly increased by consumption of FB in contrast to GB for both children with NAFLD (mean ± se, 1421.2 ± 267.1 vs. 757.3 ± 136.5; P = 0.011) and children without NAFLD (mean ± se, 622.4 ± 110.2 vs. 325.7 ± 87.6; P = 0.027), and NAFLD exacerbated this fructose effect on plasma TG (P = 0.019). At the end of visit (time point of 23 h), fasting plasma TG the next morning was significantly elevated after FB compared with GB for both NAFLD (P = 0.011) and non-NAFLD (P = 0.005) subjects (marked with asterisk). C and D, There was no significant difference in plasma apoB under two beverage-feeding conditions within 24 h, in both non-NAFLD and NAFLD subjects. E and F, Compared with GB, FB consumption was associated with greater postprandial response in TG/apoB, for both NAFLD (P < 0.0001) and non-NAFLD (P = 0.030), and NAFLD exacerbated the effect of fructose (P = 0.018) on TG/apoB (mixed model, beverage, P < 0.0001; disease, P = 0.045; beverage × disease interaction, P = 0.025). At the end of visit (time point of 23 h), fasting plasma TG/apoB the next morning was significantly elevated after FB compared with GB for both NAFLD (P = 0.011) and non-NAFLD (P = 0.016) subjects (marked with asterisk).

Effect on plasma apoB

NAFLD subjects had higher plasma apoB at baseline compared with non-NAFLD subjects due in part to higher plasma TG and a slight elevation in LDLc (Table 1). Over the two 24-h metabolic studies, there was minimal change in plasma apoB in either group (Fig. 3, C and D). In view of the fact that there was no change in LDLc during the two periods with either group (data not shown), the postprandial TG/apoB response is assumed to indirectly reflect the change in composition of the TG-rich lipoproteins (TRL). Compared with GB, FB consumption was associated with greater postprandial response in TG/apoB, for both NAFLD (P < 0.0001) and non-NAFLD (P = 0.030) groups (Fig. 3, E and F), and NAFLD exacerbated the effect of fructose (P = 0.018), but not glucose, on TG/apoB (mixed model, beverage, P < 0.0001; disease, P = 0.045; beverage × disease interaction, P = 0.025).

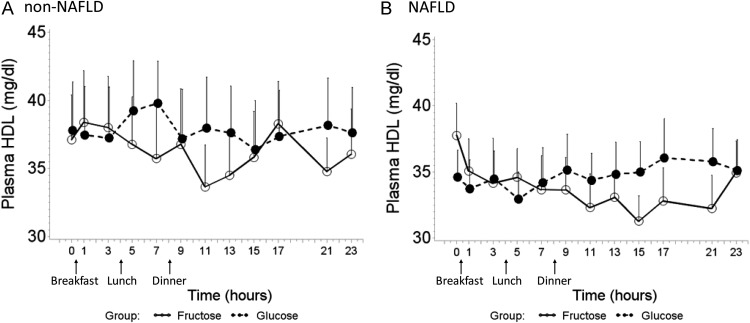

Effect on HDLc

HDLc levels were similar at baseline in NAFLD patients compared with non-NAFLD controls (Table 1). In both groups, HDLc was significantly lower after consuming FB compared with GB (Fig. 4, A and B). No difference in HDL response was found between NAFLD and non-NAFLD subjects (mixed model, beverage, P = 0.0006; disease, P = 0.478; beverage × disease interaction, P = 0.382).

Fig. 4.

HDLc trend over 24 h after consumption of FB (solid lines) and GB (dashed lines) in non-NAFLD controls (A) and pediatric NAFLD (B). Error bars stand for se. HDLc had an overall decline during consumption of FB compared with GB, and no difference in HDLc response was found between NAFLD and non-NAFLD subjects (mixed model, beverage, P = 0.0006; disease, P = 0.478; beverage × disease interaction, P = 0.382).

Discussion

Concurring with studies performed in adults (20, 27, 28, 32), we found that fructose exacerbates postprandial lipemia in children with and without NAFLD. Based on these preliminary, yet novel data, we have reached the following conclusions: 1) in the setting of nutrient-balanced meals, FB induce postprandial and overnight increases in plasma TG levels in children with and without NAFLD that does not return to baseline fasting levels by the following morning; 2) in NAFLD subjects, the marked increase in TG appears to be from an increase in size of TRL particles, as demonstrated by an increased in TG-to-apoB ratio; 3) FB result in a rapid decrease of HDLc postprandially and overnight, supporting the hypothesis that triglyceridemia results in accelerated catabolism of HDL in both children with NAFLD and healthy children; and 4) NEFA levels were not different after FB vs. GB but did appear highly abnormal in the children with NAFLD, as demonstrated by a lack of postprandial suppression of NEFA.

Hypertriglyceridemia

The effect of carbohydrates in raising plasma TG is well known, although the relative contribution of the different sugars has been debated. As early as 1961, Ahrens et al. (33) reported a fasting lipemia after a fat-free, high-carbohydrate diet. This lipemia was demonstrated by others to consist of an increase in large TG-rich VLDL, and alterations in the catabolism of VLDL explained the prolonged hypertriglyceridemia after a high-carbohydrate challenge (34, 35). Our findings are similar to the response to fructose documented by Teff et al. (27), who studied healthy women given sugar beverages with meals over a 24-h period. They demonstrated that plasma TG were significantly elevated after fructose compared with glucose several hours after each meal, and this effect persisted even 12 h after the FB (27). More recently, investigators have focused on fructose specifically and, in adults, found that it increases plasma TG in studies lasting 1 d (27), 2 wk (32), 6 d (36), 4 wk (37), and 12 wk (38) when compared with glucose feeding. Population data in adults demonstrate increased plasma TG and lower HDL in association with increased added sugar consumption, suggesting that the “high-carbohydrate effect” is sustained over time (39).

In our subjects with NAFLD, fructose increased postprandial TG and resulted in a significantly increased IAUC for TG for the 24 h. This increase may result in part from the fact that dietary fructose is less tightly regulated than glucose, bypassing the rate-limiting step in glycolysis of phosphofructokinase, resulting in increased production of acyl-CoA, a precursor in de novo lipogenesis. Although we were unable to measure VLDL-TG size directly in our study, given volume limitations in children, Chong et al. (20) demonstrated that the hypertriglyceridemia after fructose is associated with a significant increase in VLDL-TG particle size and a delay in clearance in VLDL-TG, likely from competitive inhibition. Tracer kinetic studies have indicated an increase in TG production with no change in apoB production, a further demonstration of increased VLDL particle size (35). The increase in TG-to-apoB ratio in our subjects indirectly supports these findings, although data on the TG-to-apoB ratio in isolated VLDL would have been more conclusive. In NAFLD, VLDL-TG from de novo synthesis is four to five times higher than expected compared with healthy individuals and fails to vary with fasted and fed states (40). Without a concomitant increase in VLDL apoB production, the size of secreted VLDL would be expected to be increased.

High-density lipoprotein

Clinical observation has demonstrated that there is a close relationship between hypertriglyceridemia and reduced HDL levels. Significant inverse correlations have been documented between these two lipid parameters (41, 42), and high TG/low HDLc is the typical dyslipidemia that is closely associated with insulin resistance syndromes (43), including NAFLD. TG elevation is hypothesized to affect HDL in at least two important ways: 1) decreased hydrolysis of TRL would reduce materials available as precursors for plasma HDL; and 2) increased size and number of TRL could enhance the transfer of TG from TRL to HDL by cholesteryl ester transfer protein, resulting in HDL that are relatively TG enriched and cholesterol ester depleted (42). Studies directly testing these hypotheses have demonstrated an increased fractional catabolic rate of apoA-I but not a reduction in apoA-I production rates (42), supporting the hypothesis of enhanced clearance of HDL particles. Rashid et al. (42) tested this and demonstrated that a 3–6% increase in TG content of HDL resulted in a 26% increase in the fractional catabolic rate of HDL apoA-1 (44). In our subjects, FB were followed by prolonged elevation of plasma TG and an acute decrease in HDLc levels. The acute timing of the change supports accelerated catabolism as opposed to alterations in HDL production. Although the change in HDLc was slightly less robust in the healthy subjects compared with NAFLD subjects, both groups had a significant decrease in HDLc. Others have examined HDL after longer term studies of fructose, and the results have been variable. Bantle et al. (25) studied a high-fructose diet (17% of energy) in healthy adults and did not find a significant decrease in HDL, although their data demonstrated a trend down from 54 to 50 mg/dl with continued administration of fructose. We previously evaluated cross-sectional population data and found significantly reduced HDL levels in both adults and adolescents who consumed higher amounts of added sugar (the largest source of fructose), suggestive of a chronic effect (39, 45). Interestingly, in our cross-sectional study, BMI did not modify the added sugar and HDL relationship. Similarly, in this current study, the acute changes in HDL were not affected by BMI or the level of insulin resistance.

Nonesterified fatty acids

A surprising finding in our study was the significant increase in daylong levels of NEFA in NAFLD compared with non-NAFLD, despite similar fasting values at baseline. Elevated NEFA levels have been associated with atherogenesis (46), and increased plasma NEFA may contribute to hepatic steatosis through increased esterification of fatty acids flowing to the liver resulting in increased TG. In the healthy fasting state, plasma NEFA provides the majority of the fatty acids used to synthesize hepatic derived VLDL-TG (47). After feeding, the rate of NEFA returning from adipose tissue should decline, and total plasma level should be decreased as seen in our healthy controls. Although neither group demonstrated a differential response to fructose compared with glucose, supporting previous findings by Parks et al. (19), in the NAFLD subjects, we observed a shortening of the postprandial nadir for NEFA after breakfast, and NEFA was increased throughout the day. This is markedly different from the healthy, expected pattern. Free fatty acid dynamics may be critical to the mechanism(s) of NAFLD because increased plasma NEFA may increase the load of fatty acids on the liver and be a stimulus for the increased rate of reesterification seen in NAFLD (19). In addition, increased NEFA have been shown to cause hepatic lipotoxicity (48, 49) and have been associated with increased severity of NASH in adult patients (50). Our data confirm that NEFA flux is highly dysregulated in children with NAFLD compared with healthy controls.

Strengths and limitations

Overall, our study supports the need for longer term studies of fructose reduction in children with NALFD in particular. One limitation of our study is the short-term nature of the results. Some studies, including animal models, suggest that there may be adaptation to longer term high-carbohydrate diets that would ameliorate the dyslipidemic effects. Although it is difficult to study diet effects in children in longer term studies because of subject diet variability, we previously evaluated cross-sectional data representative of the United States and found a strong association between added sugar consumption (the primary source of fructose) and TG and HDL (39, 45). Specifically, adolescents who consumed diets high in added sugars had increased TG and lower HDL levels (45). Others have shown in a cross-sectional study of adolescents that fructose consumption was associated with increased visceral adiposity, which then predicted increased CVD risk (51). Together, these two studies suggest that the short-term alterations we demonstrated in children likely have sustained effects as well.

We were unable to assess the effect of fructose directly on the liver in the children with NAFLD. In our clinical experience, decreasing soda intake (the largest source of fructose in a typical child/adolescent diet) will substantially improve liver enzymes, and in a small pilot study of fructose reduction, we documented a trend toward improved ALT (52). Other studies have suggested associations between NAFLD and fructose by documenting increased soda consumption in those with NAFLD (17), increased uric acid levels (a marker of fructose intake) in children with NAFLD (53), and increased fibrosis with increased fructose consumption in adults with NAFLD (54).

Several other potential limitations of our study should be noted. We studied a high dose of fructose that is not likely to be consumed on a daily basis by most children. We chose the dose of 33% of total calories because in the highest consumers of added sugars among children, 33% of the diet often comes from sugars (55), although it would more likely be a blend and not pure fructose. In addition, a similar study conducted in adults found this dose to be useful in examining the short-term response to fructose (27). Further studies will be needed to test whether lower doses of fructose are tolerated in children with NAFLD. Although we controlled the meal on the night before the two visits, the usual diets of our subjects in the days before the study could be influencing their response to the study beverages. We asked subjects to continue a typical diet and not change between visits; however, variations could exist. Finally, in our healthy control group, several of the children were overweight. We enrolled overweight children as well as normal-weight children to improve the chances that we were identifying differences based on the presence of NAFLD and not just elevated BMI. We were unable to enroll all overweight matched controls because most of the overweight children screened for the study had an elevated fat percentage by MRS.

Strengths of this study include the well-controlled methodology, including controlling the meal the night before the day of the study, using same subject controls, and comparing to matched controls. Previous studies of dietary sugars in NAFLD have been cross-sectional or case-based association studies, and this is the first study that we know of examining the response to fructose and glucose in both children and in NAFLD. Additionally, previous studies of lipids in pediatric NAFLD have focused on one-time fasting levels. To our knowledge, this is the first study of lipid patterns over 24 h in children with NAFLD, and it demonstrates important dysregulation of lipid metabolism.

Conclusions

In summary, we demonstrated that dietary fructose induces a marked elevation of TG and decrease in HDL in children with NAFLD; further, although healthy children appear more tolerant of fructose, they also demonstrated the same adverse metabolic effects. Because postprandial TG elevation and HDL levels are important in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis, these findings suggest that high fructose consumption levels would likely contribute to the increased CVD risk found in NAFLD patients. Although we did not find an effect of fructose on NEFA levels, we demonstrated that NEFA is significantly dysregulated in children with NAFLD, and further research is needed to investigate the role of NEFA in pediatric NAFLD. Our data add to the evidence supporting public health recommendations for all children and adolescents to moderate intake of added sugars (the primary source of fructose). Although larger studies are needed, habitual reduction of dietary fructose may be particularly important in children with NAFLD and other insulin-resistant syndromes to potentially reduce adverse effects on lipid CVD risk factors.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all of the patients and their families for generously giving of their time. This study would not have been possible without the tireless dedication of our research coordinators, Nicholas Raviele and Xiomara Hinson.

This work was supported by a New Investigator Research Award from The Obesity Society; National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grant K23 DK080953 (to M.B.V.); NIH Grants K24 RR023356 (to T.R.Z.), ES009047, ES011195, and AG038746 (to D.P.J.); and Grant UL1 RR025008 from the NIH Clinical and Translational Science Award program, National Center for Research Resources.

The authors' responsibilities are as follows: M.B.V., designed research, supervised study, wrote parts of the manuscript, and has primary responsibility for final content; R.J., cleared and analyzed data, performed IAUC calculation, wrote parts of the manuscript; N.-A.L., provided essential reagents, supervised clinical lipids measurement, and contributed to data interpretation; M.F.E., conducted clinical lipids measurement; S.L. performed statistical analysis; and D.P.J., C.J.M., J.A.W., and T.R.Z., contributed to research design, data interpretation, and manuscript development.

Disclosure Summary: The authors of the study have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Footnotes

- ALT

- Alanine aminotransferase

- apo

- apolipoprotein

- AST

- aspartate aminotransferase

- CVD

- cardiovascular disease

- FB

- fructose-containing beverage

- GB

- glucose-containing beverage

- HDL

- high-density lipoprotein

- HDLc

- HDL cholesterol

- HOMA-IR

- homeostatic model assessment for insulin resistance

- hs-CRP

- high-sensitivity C-reactive protein

- IAUC

- incremental area under the curve

- LDL

- low-density lipoprotein

- LDLc

- LDL cholesterol

- MRI

- magnetic resonance imaging

- MRS

- magnetic resonance spectroscopy

- NAFLD

- nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

- NASH

- nonalcoholic steatohepatitis

- NEFA

- nonesterified fatty acid

- TG

- triglyceride

- TRL

- TG-rich lipoprotein

- VLDL

- very LDL.

References

- 1. Schwimmer JB, Deutsch R, Kahen T, Lavine JE, Stanley C, Behling C. 2006. Prevalence of fatty liver in children and adolescents. Pediatrics 118:1388–1393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Feldstein AE, Charatcharoenwitthaya P, Treeprasertsuk S, Benson JT, Enders FB, Angulo P. 2009. The natural history of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in children: a follow-up study for up to 20 years. Gut 58:1538–1544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Söderberg C, Stål P, Askling J, Glaumann H, Lindberg G, Marmur J, Hultcrantz R. 2010. Decreased survival of subjects with elevated liver function tests during a 28-year follow-up. Hepatology 51:595–602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Adams LA, Lymp JF, St Sauver J, Sanderson SO, Lindor KD, Feldstein A, Angulo P. 2005. The natural history of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a population based cohort study. Gastroenterology 129:113–121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ramilli S, Pretolani S, Muscari A, Pacelli B, Arienti V. 2009. Carotid lesions in outpatients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. World J Gastroenterol 15:4770–4774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Schwimmer JB, Pardee PE, Lavine JE, Blumkin AK, Cook S. 2008. Cardiovascular risk factors and the metabolic syndrome in pediatric nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Circulation 118:277–283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Quirós-Tejeira RE, Rivera CA, Ziba TT, Mehta N, Smith CW, Butte NF. 2007. Risk for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in Hispanic youth with BMI > or =95th percentile. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 44:228–236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pacifico L, Cantisani V, Ricci P, Osborn JF, Schiavo E, Anania C, Ferrara E, Dvisic G, Chiesa C. 2008. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and carotid atherosclerosis in children. Pediatr Res 63:423–427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Manco M, Marcellini M, Devito R, Comparcola D, Sartorelli MR, Nobili V. 2008. Metabolic syndrome and liver histology in paediatric non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Int J Obes (Lond) 32:381–387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sartorio A, Del Col A, Agosti F, Mazzilli G, Bellentani S, Tiribelli C, Bedogni G. 2007. Predictors of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in obese children. Eur J Clin Nutr 61:877–883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sacks FM. 2002. The role of high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol in the prevention and treatment of coronary heart disease: expert group recommendations. Am J Cardiol 90:139–143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Magnussen CG, Niinikoski H, Juonala M, Kivimaki M, Ronnemaa T, Viikari JS, Simell O, Raitakari OT. 30 August 2011. When and how to start prevention of atherosclerosis? Lessons from the Cardiovascular Risk in the Young Finns Study and the Special Turku Coronary Risk Factor Intervention Project. Pediatr Nephrol doi: 10.1007/s00467-011-1990-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Musso G, Gambino R, Cassader M, Pagano G. 2011. Meta-analysis: natural history of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and diagnostic accuracy of non-invasive tests for liver disease severity. Ann Med 43:617–649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Talayero BG, Sacks FM. 2011. The role of triglycerides in atherosclerosis. Curr Cardiol Rep 13:544–552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Vos MB, Kimmons JE, Gillespie C, Welsh J, Blanck HM. 2008. Dietary fructose consumption among US children and adults: the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Medscape J Med 10:160. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Thuy S, Ladurner R, Volynets V, Wagner S, Strahl S, Königsrainer A, Maier KP, Bischoff SC, Bergheim I. 2008. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in humans is associated with increased plasma endotoxin and plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 concentrations and with fructose intake. J Nutr 138:1452–1455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ouyang X, Cirillo P, Sautin Y, McCall S, Bruchette JL, Diehl AM, Johnson RJ, Abdelmalek MF. 2008. Fructose consumption as a risk factor for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol 48:993–999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Abid A, Taha O, Nseir W, Farah R, Grosovski M, Assy N. 2009. Soft drink consumption is associated with fatty liver disease independent of metabolic syndrome. J Hepatol 51:918–924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Parks EJ, Skokan LE, Timlin MT, Dingfelder CS. 2008. Dietary sugars stimulate fatty acid synthesis in adults. J Nutr 138:1039–1046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chong MF, Fielding BA, Frayn KN. 2007. Mechanisms for the acute effect of fructose on postprandial lipemia. Am J Clin Nutr 85:1511–1520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bergheim I, Weber S, Vos M, Krämer S, Volynets V, Kaserouni S, McClain CJ, Bischoff SC. 2008. Antibiotics protect against fructose-induced hepatic lipid accumulation in mice: role of endotoxin. J Hepatol 48:983–992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Jürgens H, Haass W, Castañeda TR, Schürmann A, Koebnick C, Dombrowski F, Otto B, Nawrocki AR, Scherer PE, Spranger J, Ristow M, Joost HG, Havel PJ, Tschöp MH. 2005. Consuming fructose-sweetened beverages increases body adiposity in mice. Obes Res 13:1146–1156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Havel PJ. 2005. Dietary fructose: implications for dysregulation of energy homeostasis and lipid/carbohydrate metabolism. Nutr Rev 63:133–157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kunde SS, Roede JR, Vos MB, Orr ML, Go YM, Park Y, Ziegler TR, Jones DP. 2011. Hepatic oxidative stress in fructose induced fatty liver is not caused by sulfur amino acid insufficiency. Nutrients 3:987–1002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bantle JP, Raatz SK, Thomas W, Georgopoulos A. 2000. Effects of dietary fructose on plasma lipids in healthy subjects. Am J Clin Nutr 72:1128–1134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hallfrisch J, Reiser S, Prather ES. 1983. Blood lipid distribution of hyperinsulinemic men consuming three levels of fructose. Am J Clin Nutr 37:740–748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Teff KL, Elliott SS, Tschöp M, Kieffer TJ, Rader D, Heiman M, Townsend RR, Keim NL, D'Alessio D, Havel PJ. 2004. Dietary fructose reduces circulating insulin and leptin, attenuates postprandial suppression of ghrelin, and increases triglycerides in women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 89:2963–2972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Stanhope KL, Griffen SC, Bremer AA, Vink RG, Schaefer EJ, Nakajima K, Schwarz JM, Beysen C, Berglund L, Keim NL, Havel PJ. 2011. Metabolic responses to prolonged consumption of glucose- and fructose-sweetened beverages are not associated with postprandial or 24-h glucose and insulin excursions. Am J Clin Nutr 94:112–119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Stanhope KL, Schwarz JM, Keim NL, Griffen SC, Bremer AA, Graham JL, Hatcher B, Cox CL, Dyachenko A, Zhang W, McGahan JP, Seibert A, Krauss RM, Chiu S, Schaefer EJ, Ai M, Otokozawa S, Nakajima K, Nakano T, Beysen C, Hellerstein MK, Berglund L, Havel PJ. 2009. Consuming fructose-sweetened, not glucose-sweetened, beverages increases visceral adiposity and lipids and decreases insulin sensitivity in overweight/obese humans. J Clin Invest 119:1322–1334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sharma P, Martin DR, Pineda N, Xu Q, Vos M, Anania F, Hu X. 2009. Quantitative analysis of T2-correction in single-voxel magnetic resonance spectroscopy of hepatic lipid fraction. J Magn Reson Imaging 29:629–635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Pineda N, Sharma P, Xu Q, Hu X, Vos M, Martin DR. 2009. Measurement of hepatic lipid: high-speed T2-corrected multiecho acquisition at 1H MR spectroscopy—a rapid and accurate technique. Radiology 252:568–576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Stanhope KL, Bremer AA, Medici V, Nakajima K, Ito Y, Nakano T, Chen G, Fong TH, Lee V, Menorca RI, Keim NL, Havel PJ. 2011. Consumption of fructose and high fructose corn syrup increase postprandial triglycerides, LDL-cholesterol, and apolipoprotein-B in young men and women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 96:E1596–E1605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ahrens EH, Jr, Hirsch J, Oette K, Farquhar JW, Stein Y. 1961. Carbohydrate-induced and fat-induced lipemia. Trans Assoc Am Physicians 74:134–146 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ginsberg HN, Le NA, Melish J, Steinberg D, Brown WV. 1981. Effect of a high carbohydrate diet on apoprotein-B catabolism in man. Metabolism 30:347–353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Melish J, Le NA, Ginsberg H, Steinberg D, Brown WV. 1980. Dissociation of apoprotein B and triglyceride production in very-low-density lipoproteins. Am J Physiol 239:E354–E362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Couchepin C, Lê KA, Bortolotti M, da Encarnaçao JA, Oboni JB, Tran C, Schneiter P, Tappy L. 2008. Markedly blunted metabolic effects of fructose in healthy young female subjects compared with male subjects. Diabetes Care 31:1254–1256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lê KA, Faeh D, Stettler R, Ith M, Kreis R, Vermathen P, Boesch C, Ravussin E, Tappy L. 2006. A 4-wk high-fructose diet alters lipid metabolism without affecting insulin sensitivity or ectopic lipids in healthy humans. Am J Clin Nutr 84:1374–1379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Stanhope KL, Havel PJ. 2008. Fructose consumption: potential mechanisms for its effects to increase visceral adiposity and induce dyslipidemia and insulin resistance. Curr Opin Lipidol 19:16–24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Welsh JA, Sharma A, Abramson JL, Vaccarino V, Gillespie C, Vos MB. 2010. Caloric sweetener consumption and dyslipidemia among US adults. JAMA 303:1490–1497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Donnelly KL, Smith CI, Schwarzenberg SJ, Jessurun J, Boldt MD, Parks EJ. 2005. Sources of fatty acids stored in liver and secreted via lipoproteins in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J Clin Invest 115:1343–1351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Calabresi L, Franceschini G, Sirtori M, Gianfranceschi G, Werba P, Sirtori CR. 1990. Influence of serum triglycerides on the HDL pattern in normal subjects and patients with coronary artery disease. Atherosclerosis 84:41–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Rashid S, Watanabe T, Sakaue T, Lewis GF. 2003. Mechanisms of HDL lowering in insulin resistant, hypertriglyceridemic states: the combined effect of HDL triglyceride enrichment and elevated hepatic lipase activity. Clin Biochem 36:421–429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ginsberg HN. 1996. Diabetic dyslipidemia: basic mechanisms underlying the common hypertriglyceridemia and low HDL cholesterol levels. Diabetes 45(Suppl 3):S27–S30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lamarche B, Uffelman KD, Carpentier A, Cohn JS, Steiner G, Barrett PH, Lewis GF. 1999. Triglyceride enrichment of HDL enhances in vivo metabolic clearance of HDL apo A-I in healthy men. J Clin Invest 103:1191–1199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Welsh JA, Sharma A, Cunningham SA, Vos MB. 2011. Consumption of added sugars and indicators of cardiovascular disease risk among US adolescents. Circulation 123:249–257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Balletshofer BM, Rittig K, Volk A, Maerker E, Jacob S, Rett K, Häring H. 2001. Impaired non-esterified fatty acid suppression is associated with endothelial dysfunction in insulin resistant subjects. Horm Metab Res 33:428–431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Parks EJ, Krauss RM, Christiansen MP, Neese RA, Hellerstein MK. 1999. Effects of a low-fat, high-carbohydrate diet on VLDL-triglyceride assembly, production, and clearance. J Clin Invest 104:1087–1096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Yamaguchi K, Yang L, McCall S, Huang J, Yu XX, Pandey SK, Bhanot S, Monia BP, Li YX, Diehl AM. 2007. Inhibiting triglyceride synthesis improves hepatic steatosis but exacerbates liver damage and fibrosis in obese mice with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology 45:1366–1374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Feldstein AE, Werneburg NW, Canbay A, Guicciardi ME, Bronk SF, Rydzewski R, Burgart LJ, Gores GJ. 2004. Free fatty acids promote hepatic lipotoxicity by stimulating TNF-α expression via a lysosomal pathway. Hepatology 40:185–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Nehra V, Angulo P, Buchman AL, Lindor KD. 2001. Nutritional and metabolic considerations in the etiology of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Dig Dis Sci 46:2347–2352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Pollock NK, Bundy V, Kanto W, Davis CL, Bernard PJ, Zhu H, Gutin B, Dong Y. 2012. Greater fructose consumption is associated with cardiometabolic risk markers and visceral adiposity in adolescents. J Nutr 142:251–257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Vos MB, Weber MB, Welsh J, Khatoon F, Jones DP, Whitington PF, McClain CJ. 2009. Fructose and oxidized low-density lipoprotein in pediatric nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a pilot study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 163:674–675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Vos MB, Colvin R, Belt P, Molleston JP, Murray KF, Rosenthal P, Schwimmer JB, Tonascia J, Unalp A, Lavine JE. 2012. Correlation of vitamin E, uric acid, and diet composition with histologic features of pediatric NAFLD. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 54:90–96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Abdelmalek MF, Suzuki A, Guy C, Unalp-Arida A, Colvin R, Johnson RJ, Diehl AM. 2010. Increased fructose consumption is associated with fibrosis severity in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology 51:1961–1971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Welsh JA, Sharma AJ, Grellinger L, Vos MB. 2011. Consumption of added sugars is decreasing in the United States. Am J Clin Nutr 94:726–734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]