Abstract

Context:

Young reproductive-age women with irregular menses and androgen excess are at high risk for unfavorable metabolic profile; however, recent data suggest that menstrual regularity and hyperandrogenism improve with aging in affected women approaching menopause.

Objective:

The objective of the study was to determine whether women with hyperandrogenemia (HA) and a history of oligomenorrhea (Oligo) are at an elevated risk for metabolic syndrome (MetS) at the early stages of menopausal transition.

Methods:

Baseline data from 2543 participants (mean age of 45.8 yr) in the Study of Women's Health Across the Nation were analyzed. Women with a lifetime history of more than one 3-month interval of nongestational and nonlactational amenorrhea were classified as having a history of Oligo. The highest tertile of serum testosterone was used to define HA. Women with normal serum androgens and eumenorrhea were used as the reference group. Logistic regression models generated adjusted odds ratios (AOR), controlling for age, ethnicity, body mass index, smoking, and study site.

Results:

Oligo was associated with MetS only when coincident with HA [AOR of 1.93 for Oligo and HA [95% confidence interval (CI) 1.17–3.17], AOR of 1.25 for Oligo and normal androgens (95% CI 0.81–1.93)]. In contrast, HA conferred a consistently significant risk for MetS, regardless of the menstrual frequency status [AOR of 1.48 for HA and eumenorrhea (95% CI 1.15–1.90)].

Conclusions:

Our results suggest that HA but not history of Oligo is independently associated with the risk of prevalent MetS in pre- and perimenopausal women in their 40s.

In women, metabolic syndrome increases in incidence after menopause. Accurate prediction of cardiovascular risks and identification of particularly susceptible midlife women is imperative because this will focus limited public resources and avoid unnecessary increased surveillance of those unlikely to be affected. Hyperandrogenemia (HA) and oligomenorrhea (Oligo) confer the worst metabolic profile for young women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), exceeding the estimates for other phenotypes in this syndrome (1). Isolated high testosterone and low SHBG have been independently linked to the individual components comprising metabolic syndrome (MetS) among premenopausal women (2). Similarly, Oligo alone has been demonstrated as an independent risk factor for insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes as well as cardiovascular events in the Nurses' Health Study (3, 4). Importantly, menstrual regularity and HA have been shown to improve with aging in women with PCOS (5, 6), and serum androgen levels decline progressively during the late reproductive years in unselected women approaching menopause (7). The trajectory for metabolic and cardiovascular risks in perimenopausal women with history of HA and Oligo has not been examined and may differ from that of eumenorrheic, normoandrogenemic women.

Recent studies of unselected postmenopausal women have found inconsistent associations between endogenous androgens and subclinical atherosclerosis (8). Outcome studies linking coronary events in postmenopausal women with history of PCOS have been mixed, with some studies reporting an elevated risk (9) and others reporting no difference (10). The objectives of this report were to determine whether the midlife women with androgen excess and a history of menstrual irregularity are at an elevated metabolic risk and to appraise the relative contributions of HA and Oligo thereof. To address these questions, we assessed the relationship between high serum androgens and a history of Oligo with prevalence of MetS in a large multiethnic sample of U.S. women from the Study of Women's Health Across the Nation (SWAN).

Materials and Methods

Study population

SWAN is an ongoing multiethnic longitudinal study of women as they transition from premenopause to postmenopause. The study began in 1994; the details about the sampling frame and strategies have been published (11). Eligibility criteria included age 42–52 yr, at least one menstrual period and no hormone therapy within the prior 3 months, no current pregnancy or breast-feeding, intact uterus, and at least one ovary. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. All appropriate institutional review boards approved the study.

Reproductive parameters

Oligo was defined as experiencing more than one 3-month interval without a menstrual period since age 18 yr while not breast-feeding or pregnant by satisfying all of the following criteria: 1) an affirmative answer to the following question: since the age of 18 yr, have you experienced more than one time interval of 3 or more months when you did not have a menstrual period? 2) a negative answer to the following follow-up query: were you breast-feeding or pregnant every time it happened? and 3) negative answer to the following question: during the interval from age 25 to 35 yr, did you take birth control pills or other female hormones all the time without a break? Number of pregnancies and live births were evaluated as two-way categorical variables: nulliparity (any live birth vs. none) and nulligravidity (any pregnancy vs. none). Menopausal status was assessed based on menstrual bleeding: women with menses in the past 3 months with no change in regularity were classified as premenopausal; women with menses in the past 3 months with change in regularity were classified as early perimenopausal; and women without menses within the past 3 months but some menstrual bleeding within the past 12 months were classified as late perimenopausal. By inclusion criteria all women were pre- or early perimenopausal at baseline.

HA was defined by the highest tertile of the observed distribution of testosterone (T), corresponding to serum T greater than 50 ng/dl, using the strategy previously used by the Healthy Women Study (12). Additionally, because a strong association of the calculated measure of free androgen activity with cardiovascular risk factors has been demonstrated in perimenopausal women (13), we evaluated a free androgen index (FAI) that was derived as follows: 100 × T (nanograms per deciliter)/ 28.84 × SHBG (nanomoles per liter). The four-category combined descriptor of HA (yes vs. no) and Oligo (yes vs. no) was determined a priori as the independent variable of interest to allow for direct comparisons between women with both HA and Oligo vs. otherwise.

Metabolic parameters

Dichotomous variables were created for the MetS, based on the National Cholesterol Education Program III criteria (14) and for each component of MetS: 1) abdominal obesity (waist circumference greater than 80 cm for Chinese and Japanese, greater than 88 cm for Caucasians, African-Americans, and Hispanics); 2) hypertriglyceridemia (fasting triglycerides ≥150 mg/dl); 3) low high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol <50 mg/dl; 4) elevated blood pressure (average systolic blood pressure ≥130 mm Hg or average diastolic blood pressure ≥85 mm Hg or on antihypertensive medication); and 5) impaired fasting glucose (fasting glucose of 110 mg/dl or on diabetic medication). Participants were classified as having MetS if they satisfied three or more of the above criteria. The HOMA-IR models were used to estimate the insulin sensitivity with assayed levels of fasting glucose and insulin at the baseline as follows: HOMA-IR = (fasting insulin × fasting glucose)/22.5 (15).

Sociodemographic and lifestyle factors

Race/ethnicity was self-identified. Smoking was dichotomized as current vs. else (past or none). Education was dichotomized based on completion of high school vs. else (college or above). As a measure of socioeconomic status, the self-reported financial strain was dichotomized by the stated ability to pay for basic family needs, such as food and shelter: very difficult vs. else.

Assays

Hormone assays were conducted using an ACS-180 automated analyzer (Bayer Diagnostics Corp., Norwood, MA). Serum T concentrations were determined by chemiluminescence immunoassay. Inter- and intraassay coefficients of variation were 10.5 and 8.5%, respectively, and the lower limit of detection was 2 ng/dl. This total T assay was modified to increase precision in the low ranges found in women (16). In a validation study using gas chromatographic-mass spectrometry (GC/MS), there was excellent correlation between the SWAN total T direct chemiluminescence immunoassay and values by GC/MS with r = 0.88–0.90 for the low range of values in the present and other SWAN reports (17, 18). More recently this assay has been validated against a celite chromatography assay with an excellent correlation of the direct T measurements to T measurements derived after organic solvent extraction (19).

SHBG and dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEAS) were measured by chemiluminescent assays. Inter- and intraassay coefficients of variation for the SHBG assay were 9.9 and 6.1%, respectively, and the lower limit of detection was 2 nm. Inter- and intraassay coefficients of variation for the DHEAS assay were 11.3 and 7.6%, respectively, and the lower limit of detection was 2 μg/dl.

Analytic sample

Of the SWAN cohort of 3302 women, 269 women were excluded due to missing information for not reporting a break in for usage of birth control pills without a break or other female hormones between ages 25 and 35 yr. An additional 22 women were excluded for missing menstrual regularity data. Further exclusions were made for women without a baseline testosterone value (n = 9) or any variable used in defining the metabolic syndrome (n = 193): waist circumference, triglyceride level, hypertension status, fasting glucose or insulin therapy. Women with missing (n = 1) or abnormal TSH (greater than 5.0 μIU/ml, n = 176 or less than 0.5 μIU/ml, n = 89) were excluded as well. The final analytic sample included 2543 women, 77% of the baseline SWAN cohort.

Statistical analyses

Skewed continuous variables were compared on the log scale and then exponentiated and reported as geometric mean and their 95% confidence interval (CI). Unadjusted associations of participant characteristics by androgen/menstrual regularity status, MetS status, and the number of MetS criteria met per subject were tested using χ2 tests for categorical outcomes and t tests of the geometric mean for continuous outcomes. To test the null hypothesis of no linear trend across the increasing categories of MetS (0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, or 6), the Cochran-Armitage test statistic was used for binomial proportions and a linear model was used for continuous variables. Spearman coefficient was calculated for correlation between unadjusted total T and homeostatic model assessment insulin resistance index (HOMA-IR), waist circumference, triglycerides, and HDL. Logistic regression was used to estimate the odds ratio for MetS as a dichotomous outcome for androgen/menstrual regularity categories, adjusted for age at baseline, race/ethnicity, baseline body mass index (BMI), current smoking status, and study site. As a sensitivity analysis, the models were estimated based on the FAI rather than T. During model selection, a multiplicative interaction term was created for HA and Oligo to test for the synergy impact of this combination. The analysis was performed in SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Analysis of the study sample of 2543 women (mean age 45.8 ± 2.7 yr) by menstrual regularity and serum androgens revealed no difference in the distribution of most sociodemographic traits, reproductive history, socioeconomic status, physical activity, depression, or sleeping problems (Table 1). Approximately half of the analytic sample was classified as early perimenopausal, defined as an increase in cycle variability; no difference in menopausal status at baseline was seen by the HA/Oligo groups. Current smoking was more prevalent among women with HA (P < 0.001). Of note, few Hispanic women were classified as Oligo.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the analytical sample by menstrual regularity and serum androgensa

| Androgen status Menstrual regularity |

HA |

Normoandrogenemia |

P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oligo (n = 117) | Normal (n = 751) | Oligo (n = 208) | Normal (n = 1487) | ||

| Sociodemographic | |||||

| Age at baseline (yr) | 45.9 (45.4, 46.5) | 45.7 (45.5, 45.8) | 45.7 (45.3, 46.0) | 45.7 (45.6, 45.9) | 0.717 |

| Ethnicity (%) | <0.001 | ||||

| White | 51.3 (60) | 48.7 (366) | 48.6 (101) | 45.1 (671) | |

| Black | 37.6 (44) | 29.7 (223) | 38.0 (79) | 25.8 (383) | |

| Chinese | 1.7 (2) | 6.3 (47) | 2.4 (5) | 8.9 (132) | |

| Hispanic | 0.9 (1) | 7.1 (53) | 1.0 (2) | 9.7 (144) | |

| Japanese | 8.5 (10) | 8.3 (62) | 10.1 (21) | 10.6 (157) | |

| Education beyond high school (%) | 69.8 (81) | 77.5 (582) | 78.5 (161) | 73.4 (1077) | 0.059 |

| Physical activity score | 7.7 (7.4, 8.1) | 7.6 (7.5, 7.8) | 7.8 (7.6, 8.1) | 7.7 (7.6, 7.8) | 0.473 |

| Paying for basics: very hard (%) | 8.5 (10) | 10.0 (75) | 9.1 (19) | 9.0 (132) | 0.867 |

| Current smoking (%) | 30.8 (36) | 23.5 (175) | 14.5 (30) | 12.1 (178) | <0.001 |

| CES-D indicating depression (%) | 29.9 (35) | 23.3 (175) | 26.0 (54) | 23.9 (355) | 0.415 |

| Difficulty sleeping past 2 wk (%) | 41.9 (49) | 43.2 (323) | 45.9 (95) | 42.3 (627) | 0.787 |

| Reproductive | |||||

| Nulligravidity (%) | 12.1 (14) | 12.0 (90) | 10.1 (21) | 10.0 (148) | 0.472 |

| Age at first pregnancy (yr) | 22.5 (21.4, 23.7) | 22.6 (22.2, 23.0) | 23.1 (22.4, 23.9) | 23.1 (22.8, 23.4) | 0.206 |

| Age at last pregnancy (yr) | 31.0 (29.8, 32.2) | 30.7 (30.3, 31.2) | 31.2 (30.3, 32.2) | 30.7 (30.4, 31.1) | 0.761 |

| Nulliparity (%) | 18.8 (22) | 17.1 (128) | 16.3 (34) | 15.8 (233) | 0.777 |

| Age at first childbirth (yr) | 24.0 (22.7, 25.4) | 24.1 (23.7, 24.6) | 24.8 (24.0, 25.8) | 24.5 (24.2, 24.8) | 0.366 |

| Age at last childbirth (yr) | 30.0 (28.8, 31.4) | 30.1 (29.6, 30.6) | 30.9 (30.0, 31.8) | 30.6 (30.3, 30.9) | 0.287 |

| Premenopausal status (%) | 45.7 (53) | 52.6 (384) | 54.6 (113) | 55.5 (809) | 0.160 |

CES-D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale.

Values in the table are geometric mean (95% CI) for continuous variables or percent (n) for categorical variables.

Women with both HA and Oligo had the highest prevalence of all adverse metabolic and hormonal parameters (Table 2). Among the individual components comprising MetS, abdominal obesity was the most prevalent and abnormal fasting glucose was the least prevalent across all categories of the HA/Oligo status. Notably, the prevalence of MetS was 41.0% for the HA + Oligo group, as compared with lower rates in all others (25.7% for HA + eumenorrhea, 23.6% for normal androgens + Oligo, and 17.0% for women with normal menses and androgens, P < 0.01). Women with eumenorrhea and normal androgens had the lowest prevalence of insulin resistance and all components of MetS.

Table 2.

Anthropometric and endocrine profile of the analytical sample by menstrual regularity and serum androgensa

| Androgen status Menstrual regularity |

HA |

Normoandrogenemia |

P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oligo (n = 117) | Normal (n = 751) | Oligo (n = 208) | Normal (n = 1487) | ||

| Metabolic parameters | |||||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 30.9 (29.4, 32.6) | 28.0 (27.5, 28.4) | 27.6 (26.6, 28.6) | 26.6 (26.3, 26.9) | <0.001 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 92.7 (89.3, 96.2) | 86.1 (85.1, 87.2) | 87.2 (84.8, 89.7) | 82.9 (82.2, 83.6) | <0.001 |

| Abdominal obesity (race specific) (%) | 57.8 (67) | 45.5 (342) | 47.1 (98) | 35.9 (533) | <0.001 |

| Hypertriglyceridemia (≤150 mg/dl) (%) | 31.3 (36) | 20.1 (149) | 18.4 (38) | 16.2 (240) | <0.001 |

| Low HDL (<50 mg/dl) (%) | 52.1 (61) | 38.3 (288) | 37.5 (78) | 33.3 (495) | <0.001 |

| HTN (SBP ≥ 130 mm Hg or DBP ≥ 85 mm Hg or meds) (%) | 42.7 (50) | 34.4 (258) | 33.7 (70) | 27.4 (408) | <0.001 |

| Impaired glucose tolerance (fasting glucose ≥ 110 mg/dl or meds) (%) | 25.0 (29) | 12.7 (94) | 11.5 (24) | 9.2 (136) | <0.001 |

| MetS (%) | 41.0 (48) | 25.7 (193) | 23.6 (49) | 17.0 (253) | <0.001 |

| High SBP (≥ 130 mm Hg) (%) | 26.5 (31) | 19.8 (149) | 22.6 (47) | 16.0 (238) | 0.003 |

| High DBP (≥ 85 mm Hg) (%) | 16.4 (19) | 19.5 (146) | 16.3 (34) | 14.0 (208) | 0.010 |

| Insulin (μIU/ml) | 10.9 (9.6, 12.3) | 9.7 (9.3, 10.1) | 9.7 (8.9, 10.7) | 9.1 (8.9, 9.4) | 0.009 |

| Glucose (mg/dl) | 106.3 (100.1, 112.8) | 96.8 (95.3, 98.3) | 95.8 (92.9, 98.8) | 93.3 (92.5, 94.2) | <.001 |

| HOMA-IR indexb | 2.8 (2.4, 3.3) | 2.3 (2.2, 2.4) | 2.3 (2.0, 2.5) | 2.1 (2.0, 2.2) | <0.001 |

| Reproductive hormones | |||||

| SHBG (nm/liter) | 36.5 (32.7, 40.8) | 38.2 (36.6, 39.7) | 36.3 (32.9, 40.1) | 39.8 (38.6, 41.0) | 0.068 |

| DHEAS (μg/dl) | 132.0 (118.6, 147.1) | 138.0 (132.4, 143.9) | 87.1 (79.7, 95.1) | 95.9 (92.5, 99.3) | <0.001 |

| Estradiol (pg/ml) | 52.4 (45.8, 59.9) | 59.7 (56.5, 63.0) | 49.5 (44.8, 54.6) | 55.1 (53.0, 57.3) | 0.006 |

| TSH (μIU/ml) | 2.1 (1.9, 2.3) | 1.9 (1.8, 1.9) | 1.8 (1.6, 1.9) | 1.8 (1.8, 1.9) | 0.021 |

| T to DHEAS ratioc | 546.4 (479.2, 622.9) | 504.3 (481.1, 528.6) | 364.5 (334.4, 397.3) | 322.6 (312.1, 333.4) | |

| FAIc,d | 6.9 (6.0, 7.8) | 6.3 (6.0, 6.6) | 3.0 (2.7, 3.4) | 2.7 (2.6, 2.8) | |

| Total T (ng/dl)c | 72.2 (68.0, 76.6) | 69.6 (68.0, 71.2) | 31.7 (30.3, 33.3) | 30.9 (30.3, 31.5) | |

HTN, Hypertension; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; meds, medications.

Values in table are geometric mean (95% CI) for continuous variables or percent (n) for categorical variables.

HOMA-IR = (fasting insulin × fasting glucose)/22.5.

P values for T to DHEAS ratio, FAI, and T are omitted because the definition of HA/Oligo outcome variable includes total T.

Free Androgen Index = (100 × T)/(28.84 × SHBG).

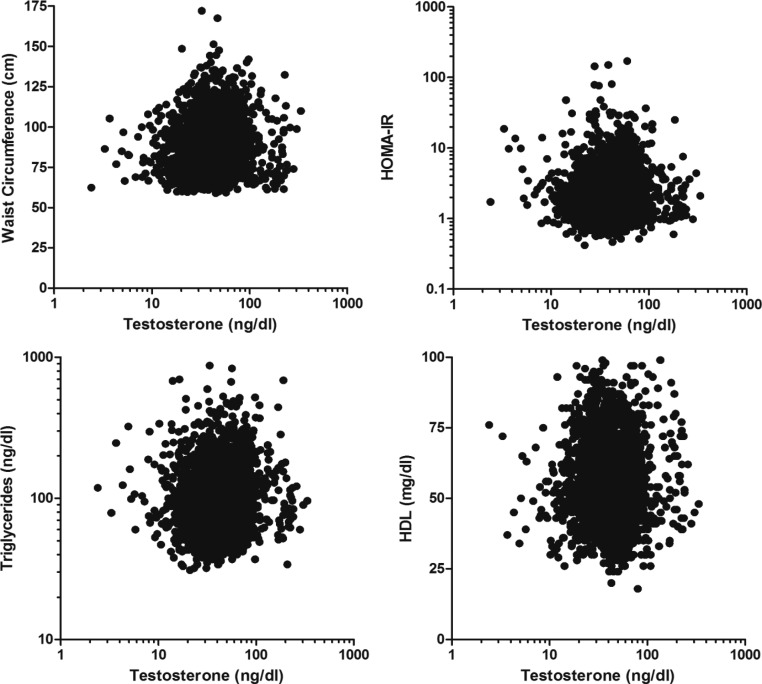

As compared with women who were MetS free, subjects with MetS were older, more likely to smoke and to report difficulty sleeping, financial strain, and experienced depressive symptoms (Tables 3 and 4). Participants with MetS were less likely to exercise and to have continued education beyond high school. Women who satisfied at least three criteria for MetS had a higher T and T to DHEAS ratio but lower SHBG and DHEAS compared with their counterparts without a MetS diagnosis. Figure 1 depicts a significant correlation between unadjusted total T and HOMA-IR, waist circumference, triglycerides, and HDL.

Table 3.

Characteristics of the analytic sample by individual components comprising MetSa

| Outcome | Number of MetS criteria met |

P value for trendb | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zero (n = 877) | One (n = 680) | Two (n = 463) | Three (n = 313) | Four (n = 154) | Five (n = 51) | ||

| Sociodemographic | |||||||

| Age at baseline (yr) | 45.4 (45.3, 45.6) | 45.8 (45.6, 46.0) | 45.8 (45.6, 46.0) | 46.0 (45.7, 46.3) | 45.7 (45.3, 46.2) | 46.3 (45.5, 47.1) | 0.002 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 22.8 (22.6, 23.0) | 26.2 (25.8, 26.6) | 31.2 (30.6, 31.8) | 33.1 (32.4, 33.9) | 35.0 (34.0, 36.0) | 36.4 (34.7, 38.2) | |

| Ethnicity (%) | |||||||

| White | 54.5 (478) | 47.2 (321) | 36.5 (169) | 40.9 (128) | 46.1 (71) | 41.2 (21) | <0.001 |

| Black | 14.6 (128) | 29.3 (199) | 43.2 (200) | 38.7 (121) | 34.4 (53) | 37.3 (19) | |

| Chinese | 10.9 (96) | 6.8 (46) | 4.8 (22) | 3.8 (12) | 3.9 (6) | 5.9 (3) | |

| Hispanic | 5.2 (46) | 7.8 (53) | 8.9 (41) | 9.9 (31) | 11.7 (18) | 13.7 (7) | |

| Japanese | 14.7 (129) | 9.0 (61) | 6.7 (31) | 6.7 (21) | 3.9 (6) | 2.0 (1) | |

| Education beyond high school (%) | 81.2 (708) | 75.8 (510) | 69.0 (316) | 72.6 (223) | 61.7 (95) | 60.0 (30) | <0.001 |

| Physical activity score | 8.1 (7.9, 8.2) | 7.4 (7.3, 7.5) | 7.1 (6.9, 7.2) | 7.0 (6.8, 7.2) | 7.0 (6.7, 7.2) | 6.7 (6.3, 7.2) | <0.001 |

| Very hard to paying for basics (%) | 5.8 (51) | 9.2 (62) | 10.8 (50) | 12.9 (40) | 15.6 (24) | 13.7 (7) | <0.001 |

| Current smoking (%) | 10.9 (95) | 17.2 (116) | 19.1 (88) | 20.1 (62) | 23.7 (36) | 29.4 (15) | <0.001 |

| CES-D indicating depression (%) | 18.9 (166) | 23.2 (158) | 29.4 (136) | 29.7 (93) | 30.5 (47) | 25.5 (13) | <0.001 |

| Difficulty sleeping past 2 wk (%) | 38.9 (341) | 44.1 (298) | 43.9 (202) | 48.2 (151) | 44.2 (68) | 45.1 (23) | 0.005 |

| Reproductive | |||||||

| Premenopausal status (%) | 58.0 (498) | 54.4 (361) | 52.1 (237) | 52.8 (161) | 51.0 (78) | 30.0 (15) | <0.001 |

| SHBG (nm/liter) | 47.5 (45.8, 49.3) | 40.9 (39.2, 42.7) | 34.2 (32.3, 36.1) | 31.5 (29.8, 33.3) | 26.6 (24.4, 29.1) | 26.8 (22.9, 31.3) | <0.001 |

| DHEAS (μg/dl) | 121.9 (117.2, 126.7) | 106.5 (100.8, 112.6) | 96.9 (91.0, 103.3) | 99.1 (92.2, 106.5) | 90.4 (79.6, 102.6) | 83.8 (66.5, 105.6) | <0.001 |

| Estradiol (pg/ml) | 62.1 (59.0, 65.4) | 53.9 (50.9, 57.1) | 56.4 (52.7, 60.3) | 48.0 (44.2, 52.0) | 48.1 (43.7, 52.9) | 49.0 (40.2, 59.6) | <0.001 |

| TSH (μIU/ml) | 1.9 (1.8, 1.9) | 1.8 (1.7, 1.9) | 1.9 (1.8, 1.9) | 1.8 (1.7, 1.9) | 1.9 (1.8, 2.1) | 1.9 (1.7, 2.1) | 0.723 |

| T/DHEAS ratio | 325.3 (312.6, 338.5) | 368.6 (349.6, 388.7) | 414.9 (389.3, 442.2) | 449.9 (417.5, 484.8) | 506.0 (449.6, 569.5) | 584.2 (451.3, 756.2) | <0.001 |

| FAI | 2.9 (2.8, 3.0) | 3.3 (3.1, 3.5) | 4.1 (3.8, 4.4) | 4.9 (4.5, 5.3) | 6.0 (5.3, 6.7) | 6.3 (5.2, 7.7) | <0.001 |

| T, ng/dl | 39.6 (38.4, 41.0) | 39.3 (37.7, 40.9) | 40.2 (38.4, 42.2) | 44.6 (41.9, 47.4) | 45.7 (41.6, 50.3) | 49.0 (43.1, 55.5) | <0.001 |

CES-D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale.

Values in table geometric mean (95% CI) for continuous variables or percent (n) for categorical variables.

Cochran-Armitage test for trend was used for trend for categorical variables; linear test for trend was used for continuous variables; P value for race is from a χ 2 but not a test for trend.

Table 4.

Characteristics of the analytical sample by MetSa

| Outcome | MetS |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No (n = 2020) | Yes (n = 543) | ||

| Sociodemographic | |||

| Age at baseline (yr) | 45.4 (45.3, 45.6) | 45.8 (45.6, 46.0) | 0.005 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 22.8 (22.6, 23.0) | 26.2 (25.8, 26.6) | <0.001 |

| Ethnicity (%) | |||

| White | 54.5 (478) | 47.2 (321) | |

| Black | 14.6 (128) | 29.3 (199) | |

| Chinese | 10.9 (96) | 6.8 (46) | |

| Hispanic | 5.2 (46) | 7.8 (53) | |

| Japanese | 14.7 (129) | 9.0 (61) | |

| Education beyond high school (%) | 81.2 (708) | 75.8 (510) | <0.001 |

| Physical activity score | 8.1 (7.9, 8.2) | 7.4 (7.3, 7.5) | <0.001 |

| Very hard to paying for basics (%) | 5.8 (51) | 9.2 (62) | <0.001 |

| Current smoking (%) | 10.9 (95) | 17.2 (116) | <0.001 |

| CES-D indicating depression (%) | 18.9 (166) | 23.2 (158) | <0.001 |

| Difficulty sleeping past 2 wk (%) | 38.9 (341) | 44.1 (298) | 0.073 |

| Reproductive | 0.002 | ||

| Premenopausal status (%) | 58.0 (498) | 54.4 (361) | <0.001 |

| SHBG (nm/liter) | 47.5 (45.8, 49.3) | 40.9 (39.2, 42.7) | <0.001 |

| DHEAS (μg/dl) | 121.9 (117.2, 126.7) | 106.5 (100.8, 112.6) | <0.001 |

| Estradiol (pg/ml) | 62.1 (59.0, 65.4) | 53.9 (50.9, 57.1) | 0.559 |

| TSH (μIU/ml) | 1.9 (1.8, 1.9) | 1.8 (1.7, 1.9) | <0.001 |

| T to DHEAS ratio | 325.3 (312.6, 338.5) | 368.6 (349.6, 388.7) | <0.001 |

| FAI | 2.9 (2.8, 3.0) | 3.3 (3.1, 3.5) | <0.001 |

| T (ng/dl) | 39.6 (38.4, 41.0) | 39.3 (37.7, 40.9) | <0.001 |

CES-D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale.

Values in table geometric mean (95% CI) for continuous variables or percent (n) for categorical variables.

Fig. 1.

Correlation of serum T with HOMA-IR and selected individual components comprising MetS. Spearman Correlation of T with waist circumference (ρ = 0.124), HOMA-IR (ρ = 0.081), triglycerides (ρ = 0.115), and HDL (ρ = −0.040), all P < 0.001.

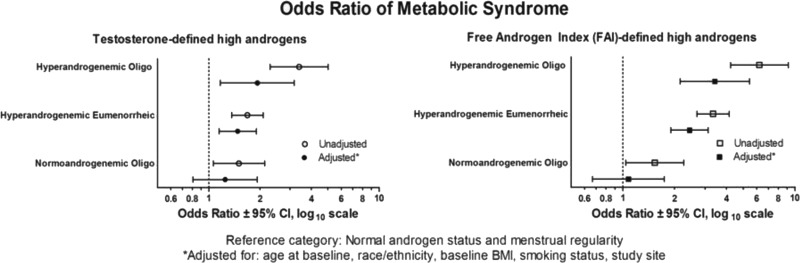

Multivariate analysis (Fig. 2) revealed that Oligo was associated with the outcome only when coincident with HA. The highest likelihood of MetS was among women with both HA and Oligo [odds ratio (OR) 1.93, 95% CI 1.17–3.17], followed by women with HA and normal menses (OR 1.48, 95% CI 1.15–1.90) and women with normal androgens and Oligo (OR 1.25, 95% CI 0.81–1.93) compared with the women with eumenorrhea and normal androgens. When the FAI was used instead of serum T for characterization of the HA group, similar results were obtained (Fig. 2). When directly tested, there was no significant interaction between HA and Oligo in any of the models estimated, indicating that the synergy of the combination of HA and Oligo was not statistically significant beyond the additive effects.

Fig. 2.

History of Oligo augments the association of hyperandrogenemia with MetS. Reference category includes normal androgen status and menstrual regularity, adjusted for age at baseline, race/ethnicity, baseline BMI, smoking status, and study site.

Discussion

In this unselected large cohort of premenopausal, ethnically diverse, midlife U.S. women, subjects exhibiting both androgen excess and a history of menstrual irregularity were at the highest risk for MetS. Multivariate analysis revealed that HA was associated with an adverse metabolic profile irrespective of menstrual history, whereas Oligo alone did not confer an elevated risk. No effect modification was present, suggesting that these two factors may exert distinct effects on metabolic health. Our study expands the findings from the Nurses' Health Study, in which women with irregular menses demonstrated a significantly increased risk for developing type 2 diabetes mellitus (3). The current report bridges a knowledge gap by depicting the prevalence of metabolic risks in multiethnic U.S. women with HA and Oligo in their 40s who are at the early stages of menopausal transition. Most published studies involved postmenopausal women (i.e. more removed from their own menstrual history and more difficult to assay T) (8, 20–22), Caucasian cohorts (23), an association with FAI but not T [secondary associations of SHBG with insulin resistance rather than an impact of HA per se (22)], or an incomplete characterization such that only menstrual history (3) or only hirsutism was available (23).

Understanding the natural progression of metabolic and cardiovascular risks during menopausal transition is critical because the frequency of coronary heart disease starts to increase in women after the age of 45 yr (24). Several studies demonstrated the association between elevated endogenous androgens and prevalent diabetes mellitus and other metabolic risks (9, 20). Taponen et al. (23) reported that women with self-reported Oligo and hirsutism at 31 yr of age presented with more adverse metabolic risks than either determinant alone. In agreement with our findings, Barber et al. (25) reported that Oligo without HA did not impart an unfavorable cardiovascular risk profile among 309 PCOS women in their early 30s. However, there is some circumstantial evidence to suggest that the trajectory of metabolic risks in aging women with Oligo and HA may not be linear. Contradictory relationships between endogenous androgens and atherosclerosis markers after menopause have been reported (8). Furthermore, aging women with PCOS exhibit an amelioration of symptoms with improvement in hyperandrogenism (6) and menstrual regularity (5). Thus, heightened awareness of the women with the highest susceptibility for metabolic and cardiovascular risks has potential public health implications as it allows focusing preventive measures on a subset of population at the highest risk for increased morbidity.

Our analysis relied on the T direct chemiluminescence immunoassay that has been cross-validated by a subsequent comparison with testosterone measured by RIA and GC/MS (18). This is also in concert with a recent blinded study of liquid chromatographic mass spectrometry and immunoassay methods that included a functional correlation with hirsutism score and demonstrated that select T immunoassays are comparable with liquid chromatographic mass spectrometry (26). Furthermore, although some studies have shown an association with FAI but not T with metabolic risks (24), our results have not changed when FAI was used instead of serum T for characterization of the HA group, demonstrating that we have observed an effect of HA rather than that of SHBG (13). Additionally, further assessment of the androgen profile revealed that lower DHEAS serum levels were seen in women with MetS as well as a significant trend for decreasing DHEAS with a greater number of MetS criteria. Vryonidou et al. (27) demonstrated that DHEAS was a negative predictor for premature atherosclerosis of the carotid arteries in young women with PCOS. In our study, a progressive rise of the ratio of serum T to DHEAS was significantly associated with a higher prevalence of MetS (Table 3). Opposing associations of DHEAS and T with insulin sensitivity have been reported by other groups in young PCOS women (28, 29). The period of late menopausal transition has recently been shown as a time during which a significant rise in serum DHEAS occurs, and this rise appears to be of adrenal origin (30). Taken together, these findings suggest a differential impact of adrenal and ovarian androgens in mediating metabolic health and deserve further study.

Several secondary outcomes demonstrated in our study are noteworthy. Women with HA and Oligo were more likely to smoke than their counterparts with normal androgens and regular menses. This observation warrants further attention as smoking is common, even among PCOS women seeking pregnancy (31), and is associated with a worsening androgen profile and insulin resistance (32). Thus, women with PCOS who choose to smoke may be particularly susceptible to metabolic and cardiovascular abnormalities and may benefit from a concerted public health effort. Furthermore, we report that the HA and Oligo classification was not associated with lifetime nulligravidity or nulliparity (Table 1). This finding is in agreement with a recent report from 103 PCOS women demonstrating that the family size of women with PCOS is not smaller than that of age-matched controls (33) as well as a long-term follow-up study of women with PCOS, indicating normal lifetime fecundity (34). Thus, despite their defining characteristic of oligoovulation, women with PCOS either have sufficient intermittent ovulation to achieve their desired family size or are often successful in their attempts to conceive with medical assistance. Finally, the prevalence of depression did not differ by HA/Oligo status in our cohort, suggesting that the frequency of depression is not elevated in PCOS women in their 40s. The preponderance of literature on this subject is to the contrary of our findings (35). This may represent a publication bias, or there may be a decrease in the likelihood that a woman with PCOS has depressive symptoms as she ages.

We acknowledge several limitations. As a cross-sectional study, the present report is subject to a prevalence-incidence bias because we cannot be certain that a given factor precedes an outcome. Although MetS could have possibly preexisted before development of HA and/or Oligo, this contention is not supported by the extant literature as the prevalence of MetS increases linearly with age (36), whereas serum androgen levels decline progressively during the reproductive years in unselected (7) and PCOS women alike (6). We lacked ability to evaluate the prevalence of other potential known causes for HA such as hyperprolactinemia and nonclassic congenital adrenal hyperplasia. However, these entities are infrequent causes of isolated HA in the absence of any other associated symptoms. Our available definition of Oligo is potentially subject to misclassification because women who did not have chronicity (i.e. infrequent menses that were always every 2 months apart) could have been classified as eumenorrheic; however, the fact that we found a considerable consistency in reported relationships is a testament to the internal validity of our analyses and robustness of these very simple clinical criteria. Furthermore, use of self-reported Oligo has been investigated as a potential proxy for PCOS with confirmatory endocrine studies in the Northern Finland Birth Cohort 1966 Study (37). Additionally, we did not have the ability to characterize the subjects by ovarian morphology or ovarian volume because no pelvic ultrasound evaluation was conducted in SWAN. However, several established sets of criteria for PCOS enable diagnosis of this condition, regardless of the ovarian appearance (38, 39). Furthermore, polycystic ovaries tend to resolve with age and rarely have been associated with metabolic abnormalities (40).

The current report represents a cross-sectional evaluation of the SWAN baseline visit. The true natural progression of differential metabolic risks can be ascertained only with a prospective investigation. Relative androgen excess during the menopausal transition has been shown to increase the risk of incident MetS (16). Although it is not possible to make inferences about causality in a cross-sectional study, our study provides an appropriate platform to further pursue the question of whether insulin resistance associated with MetS is the primary driver of the relationship between HA and MetS during menopausal transition. Thus, longitudinal follow-up of women with HA and Oligo will address a hitherto unanswered question: do the initially elevated metabolic and cardiovascular risks in PCOS women follow a linear trajectory parallel with chronological aging, do they plateau, or do they accelerate, as is seen in eumenorrheic women.

Acknowledgments

The Study of Women's Health Across the Nation (SWAN) has grant support from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), Department of Health and Human Services, through the National Institute on Aging, the National Institute of Nursing Research, and the NIH Office of Research on Women's Health (Grants NR004061, AG012505, AG012535, AG012531, AG012539, AG012546, AG012553, AG012554, and AG012495). The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Aging, National Institute of Nursing Research, Office of Research on Women's Health, or the NIH. Supplemental funding from The National Institute on Child and Human Development is also gratefully acknowledged. Clinical centers included the following: University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Siobán Harlow, principal (PI) 2011, MaryFran Sowers, PI 1994–2011; Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, Joel Finkelstein, PI 1999 to present; Robert Neer, PI 1994–1999; Rush University, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, IL, Howard Kravitz, PI 2009 to present; Lynda Powell, PI 1994–2009; University of California, Davis/Kaiser, Ellen Gold, PI; University of California, Los Angeles, Gail Greendale, PI; Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY, Carol Derby, PI 2011, Rachel Wildman, PI 2010–2011; Nanette Santoro, PI 2004–2010; University of Medicine and Dentistry, New Jersey Medical School, Newark, NJ, Gerson Weiss, PI 1994–2004; and the University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, Karen Matthews, PI. NIH Program Office was the National Institute on Aging, Bethesda, MD, Sherry Sherman 1994 to present; Marcia Ory 1994–2001; National Institute of Nursing Research, Bethesda, MD, Program Officers. The central laboratory was the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Daniel McConnell (Central Ligand Assay Satellite Services). The coordinating center was the University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, Kim Sutton-Tyrrell, PI 2001 to present; New England Research Institutes, Watertown, MA, Sonja McKinlay, PI 1995–2001. The Steering Committee consisted of Susan Johnson, current chair, and Chris Gallagher, former chair. We thank the study staff at each site and all of the women who participated in SWAN.

Disclosure Summary: See Appendix for full disclosure information.

A.J.P. received an unrestricted research grant from Bayer, and N.S. has stock options in Menogenix.

Footnotes

- BMI

- Body mass index

- CI

- confidence interval

- DHEAS

- dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate

- FAI

- free androgen index

- GC/MS

- gas chromatographic-mass spectrometry

- HA

- hyperandrogenemia

- HDL

- high-density lipoprotein

- HOMA-IR

- homeostatic model assessment insulin resistance index

- MetS

- metabolic syndrome

- Oligo

- oligomenorrhea

- OR

- odds ratio

- PCOS

- polycystic ovary syndrome

- SWAN

- Study of Women's Health Across the Nation

- T

- testosterone.

References

- 1. Jovanovic VP, Carmina E, Lobo RA. 2010. Not all women diagnosed with PCOS share the same cardiovascular risk profiles. Fertil Steril 94:826–832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Haffner SM, Valdez RA. 1995. Endogenous sex hormones: impact on lipids, lipoproteins, and insulin. Am J Med 98:40S–47S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Solomon CG, Hu FB, Dunaif A, Rich-Edwards J, Willett WC, Hunter DJ, Colditz GA, Speizer FE, Manson JE. 2001. Long or highly irregular menstrual cycles as a marker for risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus. JAMA 286:2421–2426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Solomon CG, Hu FB, Dunaif A, Rich-Edwards JE, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC, Speizer FE, Manson JE. 2002. Menstrual cycle irregularity and risk for future cardiovascular disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 87:2013–2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Elting MW, Korsen TJM, Rekers-Mombarg LT, Schoemaker J. 2000. Women with polycystic ovary syndrome gain regular menstrual cycles when ageing. Hum Reprod 15:24–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Winters SJ, Talbott E, Guzick DS, Zborowski J, McHugh KP. 2000. Serum testosterone levels decrease in middle age in women with the polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril 73:724–729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Davison SL, Bell R, Donath S, Montalto JG, Davis SR. 2005. Androgen levels in adult females: changes with age, menopause, and oophorectomy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 90:3847–3853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ouyang P, Vaidya D, Dobs A, Golden SH, Szklo M, Heckbert SR, Kopp P, Gapstur SM. 2009. Sex hormone levels and subclinical atherosclerosis in postmenopausal women: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis 204:255–261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Shaw LJ, Bairey Merz CN, Azziz R, Stanczyk FZ, Sopko G, Braunstein GD, Kelsey SF, Kip KE, Cooper-Dehoff RM, Johnson BD, Vaccarino V, Reis SE, Bittner V, Hodgson TK, Rogers W, Pepine CJ. 2008. Postmenopausal women with a history of irregular menses and elevated androgen measurements at high risk for worsening cardiovascular event-free survival: results from the National Institutes of Health-National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute sponsored Women's Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 93:1276–1284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 10. Pierpoint T, McKeigue PM, Isaacs AJ, Wild SH, Jacobs HS. 1998. Mortality of women with polycystic ovary syndrome at long-term follow-up. J Clin Epidemiol 51:581–586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sowers MF, Crawford S, Sternfeld B, Morgenstein D, Gold E, Greendale G, Evans D, Neer R, Matthews K, Sherman S, Lo A, Weiss G, Kelsey J. 2000. SWAN: a multi-center, multi-ethnic, community-based cohort study of women and the menopausal transition. In: Lobo RA, Kelsey J, Marcus R, eds. Menopause: biology and pathobiology. San Diego: Academic Press; 175–188 [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kuller LH, Gutai JP, Meilahn E, Matthews KA, Plantinga P. 1990. Relationship of endogenous sex steroid hormones to lipids and apoproteins in postmenopausal women. Arteriosclerosis 10:1058–1066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sutton-Tyrrell K, Wildman RP, Matthews KA, Chae C, Lasley BL, Brockwell S, Pasternak RC, Lloyd-Jones D, Sowers MF, Torréns JI, Investigators ftS 2005. Sex hormone-binding globulin and the free androgen index are related to cardiovascular risk factors in multiethnic premenopausal and perimenopausal women enrolled in the Study of Women Across the Nation (SWAN). Circulation 111:1242–1249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. 2002. Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) final report. Circulation 106:3143–3421 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Katsuki A, Sumida Y, Gabazza EC, Murashima S, Furuta M, Araki-Sasaki R, Hori Y, Yano Y, Adachi Y. 2001. Homeostasis model assessment is a reliable indicator of insulin resistance during follow-up of patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 24:362–365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Santoro N, Torrens J, Crawford S, Allsworth JE, Finkelstein JS, Gold EB, Korenman S, Lasley WL, Luborsky JL, McConnell D, Sowers MF, Weiss G. 2005. Correlates of circulating androgens in mid-life women: the study of women's health across the nation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 90:4836–4845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sowers MF, Zheng H, McConnell D, Nan B, Karvonen-Gutierrez CA, Randolph JF., Jr 2009. Testosterone, sex hormone-binding globulin and free androgen index among adult women: chronological and ovarian aging. Hum Reprod 24:2276–2285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. McConnell D, Sowers M, Chen J, Lasley BL. Assessment of circulating androgens in mid-aged women: direct immunoassay for testosterone correlates with GCMS and RIA. Program of the 89th Annual Meeting of The Endocrine Society, Toronto, Canada, 2007 (Abstract 852253) [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chen J, Sowers MR, Moran FM, McConnell DS, Gee NA, Greendale GA, Whitehead C, Kasim-Karakas SE, Lasley BL. 2006. Circulating bioactive androgens in midlife women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 91:4387–4394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Patel SM, Ratcliffe SJ, Reilly MP, Weinstein R, Bhasin S, Blackman MR, Cauley JA, Sutton-Tyrrell K, Robbins J, Fried LP, Cappola AR. 2009. Higher serum testosterone concentration in older women is associated with insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome, and cardiovascular disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 94:4776–4784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Oh JY, Barrett-Connor E, Wedick NM, Wingard DL. 2002. Endogenous sex hormones and the development of type 2 diabetes in older men and women: the Rancho Bernardo study. Diabetes Care 25:55–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Golden SH, Ding J, Szklo M, Schmidt MI, Duncan BB, Dobs A. 2004. Glucose and insulin components of the metabolic syndrome are associated with hyperandrogenism in postmenopausal women: the atherosclerosis risk in communities study. Am J Epidemiol 160:540–548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Taponen S, Martikainen H, Järvelin MR, Sovio U, Laitinen J, Pouta A, Hartikainen AL, McCarthy MI, Franks S, Paldanius M, Ruokonen A. 2004. Metabolic cardiovascular disease risk factors in women with self-reported symptoms of oligomenorrhea and/or hirsutism: Northern Finland Birth Cohort 1966 Study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 89:2114–2118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lerner DJ, Kannel WB. 1986. Patterns of coronary heart disease morbidity and mortality in the sexes: a 26-year follow-up of the Framingham population. Am Heart J 111:383–390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Barber TM, Wass JAH, McCarthy MI, Franks S. 2007. Metabolic characteristics of women with polycystic ovaries and oligo-amenorrhoea but normal androgen levels: implications for the management of polycystic ovary syndrome. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 66:513–517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Legro RS, Schlaff WD, Diamond MP, Coutifaris C, Casson PR, Brzyski RG, Christman GM, Trussell JC, Krawetz SA, Snyder PJ, Ohl D, Carson SA, Steinkampf MP, Carr BR, McGovern PG, Cataldo NA, Gosman GG, Nestler JE, Myers ER, Santoro N, Eisenberg E, Zhang M, Zhang H. 2010. Total testosterone assays in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: precision and correlation with hirsutism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 95:5305–5313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Vryonidou A, Papatheodorou A, Tavridou A, Terzi T, Loi V, Vatalas IA, Batakis N, Phenekos C, Dionyssiou-Asteriou A. 2005. Association of hyperandrogenemic and metabolic phenotype with carotid intima-media thickness in young women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 90:2740–2746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chen MJ, Chen CD, Yang JH, Chen CL, Ho HN, Yang WS, Yang YS. 2011. High serum dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate is associated with phenotypic acne and a reduced risk of abdominal obesity in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Hum Reprod 26:227–234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Buffington CK, Givens JR, Kitabchi AE. 1991. Opposing actions of dehydroepiandrosterone and testosterone on insulin sensitivity—in vivo and in vitro studies of hyperandrogenic females. Diabetes 40:693–700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lasley BL, Crawford SL, Laughlin GA, Santoro N, McConnell DS, Crandall C, Greendale GA, Polotsky AJ, Vuga M. 2011. Circulating dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate levels in women who underwent bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy during the menopausal transition. Menopause 18:494–498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Legro RS, Myers ER, Barnhart HX, Carson SA, Diamond MP, Carr BR, Schlaff WD, Coutifaris C, McGovern PG, Cataldo NA, Steinkampf MP, Nestler JE, Gosman G, Guidice LC, Leppert PC. 2006. The Pregnancy in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Study: baseline characteristics of the randomized cohort including racial effects. Fertil Steril 86:914–933 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Cupisti S, Häberle L, Dittrich R, Oppelt PG, Reissmann C, Kronawitter D, Beckmann MW, Mueller A. 2010. Smoking is associated with increased free testosterone and fasting insulin levels in women with polycystic ovary syndrome, resulting in aggravated insulin resistance. Fertil Steril 94:673–677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pall M, Stephens K, Azziz R. 2006. Family size in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril 85:1837–1839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hudecova M, Holte J, Olovsson M, Sundström Poromaa I. 2009. Long-term follow-up of patients with polycystic ovary syndrome: reproductive outcome and ovarian reserve. Hum Reprod 24:1176–1183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Månsson M, Holte J, Landin-Wilhelmsen K, Dahlgren E, Johansson A, Landén M. 2008. Women with polycystic ovary syndrome are often depressed or anxious—a case control study. Psychoneuroendocrinology 33:1132–1138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Park YW, Zhu S, Palaniappan L, Heshka S, Carnethon MR, Heymsfield SB. 2003. The metabolic syndrome: prevalence and associated risk factor findings in the U.S. population from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–1994. Arch Intern Med 163:427–436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Taponen S, Martikainen H, Järvelin MR, Laitinen J, Pouta A, Hartikainen AL, Sovio U, McCarthy MI, Franks S, Ruokonen A. 2003. Hormonal profile of women with self-reported symptoms of oligomenorrhea and/or hirsutism: Northern Finland birth cohort 1966 study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 88:141–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Zawadzki JK, Dunaif A. 1992. Diagnostic criteria for polycystic ovary syndrome: towards a rational approach. In: Dunaif A, Givens JR, Haseltine FP, Merriam GR, eds. Polycystic ovary syndrome. Oxford, UK: Blackwell; 59–69 [Google Scholar]

- 39. Azziz R, Carmina E, Dewailly D, Diamanti-Kandarakis E, Escobar-Morreale HF, Futterweit W, Janssen OE, Legro RS, Norman RJ, Taylor AE, Witchel SF. 2009. The Androgen Excess and PCOS Society criteria for the polycystic ovary syndrome: the complete task force report. Fertil Steril 91:456–488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Johnstone EB, Rosen MP, Neril R, Trevithick D, Sternfeld B, Murphy R, Addauan-Andersen C, McConnell D, Pera RR, Cedars MI. 2010. The Polycystic Ovary Post-Rotterdam: a common, age-dependent finding in ovulatory women without metabolic significance. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 95:4965–4972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]