Abstract

One defining feature of apicomplexan parasites is their special ability to actively invade host cells. Although rapid, invasion is a complicated process that requires coordinated activities of host cell attachment, protein secretion, and motility by the parasite. Central to this process is the establishment of a structure called moving junction (MJ), which forms a tight connection between invading parasite and host cell membranes through which the parasite passes to enter into the host. Although recognized microscopically for decades, molecular characterization of the MJ was only enabled by the recent discovery of components that make up this multi-protein complex. Exciting progress made during the last few years on both the structure and function of the components of the MJ is reviewed here.

Introduction

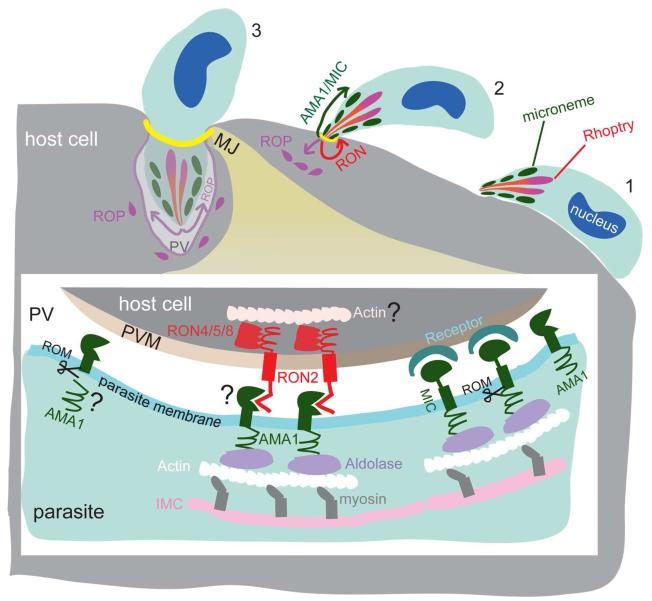

Apicomplexan parasites are obligate intracellular pathogens that represent a major cause of morbidity and mortality in humans and livestock. Important apicomplexan parasites include the malaria-causing Plasmodium spp., which collectively kill almost one million people every year; the causative agent of toxoplasmosis (Toxoplasma gondii) that chronically infects 20-30% of the world’s population; Cryptosporidium parvum, the cause of water borne diarrheal disease, as well as many other animal pathogens. One characteristic feature shared by these protozoan parasites is the presence of an apical complex consisting of specialized secretory organelles known as micronemes and rhoptries that are involved in host cell invasion [1]. Although they infect different types of host cells, apicomplexan parasites share a conserved mode of host cell invasion [2]. Sequential secretion of proteins from micronemes and rhoptries enables parasite motility, promotes close attachment to the target cell, and leads to active penetration of the host cell [2]. During invasion, the host cell membrane invaginates to enclose the parasite within the parasitophorous vacuole (PV) [3], a membrane bound compartment where the parasite replicates (Fig 1).

Fig 1.

Molecular details of the moving junction (MJ) formated during host cell invasion by apicomplexan parasites. As exemplified by Toxoplasma, the zoite loosely attaches to the target cell prior to invasion using a variety of cell surface adhesins (1). Subsequently, apical adhesion molecules such as AMA1and MIC2 are secreted from micronemes to the surface of zoite to initiate an intimate association between the apical end of the parasite and host cell (2). Invasion is initiated by formation of a moving junction (MJ) from proteins secreted from micronemes (AMA1) and the rhoptry neck (RON proteins) (2). At the same time, the contents of rhoptries (ROP) are secreted directly into the host cell, where they occupy small vesicular clusters. The parasite pushes itself through the MJ and enters into the parasitophorous vacuole (PV), which is formed by invagination of the host plasma membrane. The PV membrane (PVM) is extensively modified during invasion by secretion from rhoptries and exclusion of host proteins and (3). Lower image shows the detailed molecular interactions at the MJ. MIC proteins engage host cell surface receptors. The AMA1-RON2 interaction is thought to mediate formation of the junction. Adhesins such as MIC2 and AMA1 connect to the parasite cytoskeleton (actin, myosin, and the inner membrane complex (IMC)) through a bridging interaction with aldolase. Intramembrane proteases such as rhomboids (ROM) cleave adhesins within the membrane. Additional details are provided in the text. Areas of uncertainty or controversy are indicated by “?”.

Due to its unique nature, the invasion process has attracted a large amount of investigation, and it provides an attractive target for development of anti-parasitic vaccines and/or new drugs. Invasion is a rapid process that is completed within 15-30 seconds [4]. Central to this process is the establishment of the MJ, formed by close opposition of the invading parasite and host cell membranes during invasion. Although first described more than 30 years ago in electron microscopy studies [5], the molecular nature of the MJ has been identified only recently. In this review, we will discuss our current understanding of this important structure that lies at the parasite-host interface.

Molecular makeup of the MJ

In 2005, two independent studies carried out in Toxoplasma, one looking for AMA1 associated proteins and the other searching for antigens recognized by an antibody that stained the MJ, identified rhoptry neck proteins RON2, RON4 and RON5, as well as AMA1, as key components of the MJ [6,7]. Subsequent immuno-precipitation experiments discovered another rhoptry neck protein RON8 as part of the MJ complex in Toxoplasma [8,9]. Immunofluorescence and immunoelectron microscopy revealed that RON proteins reside in the neck portion of rhoptries in parasites prior to host cell engagement [6-8]. However, at the onset of invasion, these proteins are released at the apical end of the parasite and re-localize to the host surface to form a ring-like structure through which the parasite enters the host cell [6-8]. Through interaction with RON proteins, AMA1 is also found at the MJ during invasion [6]. However, unlike the discrete ring-like localization pattern of the RON proteins, AMA1 also localizes to the entire surface of the invading parasite [6,8]. The broad distribution of AMA1 is partially due to its abundance in the cell since a Toxoplasma cell line expressing 10% of the wild type level of AMA1 [10] displayed stronger MJ localization [6].

Most of the MJ components identified in Toxoplasma are well conserved among apicomplexan parasites, with homologues easily identified in other species such as Plasmodium [11-14]. The only exception is RON8, which seems to be a coccidian-specific, thus far found only in Toxoplasma and Neospora [9]. The interactions between AMA1 and RON proteins have been confirmed experimentally in Plasmodium, and the behavior of these molecules during invasion is essentially the same as those in Toxoplasma [11-13], demonstrating the evolutionary conservation of the structure and function of the MJ.

Functional roles of MJ components during invasion

Although details regarding its function are still lacking, the MJ is thought provide anchorage to the host cell while the parasite’s actin-myosin motor powers invasion [2]. During invasion the majority of type I transmembrane proteins are excluded, while many proteins found within lipid rafts gain access to the vacuolar membrane containing T. gondii [15,16] or P. falciparum [17]. The MJ is thought to control this selective sieving process as the host cell membrane flows past the junction; however, the precise mechanism involved is not clear.

Among the MJ components, AMA1 is the best characterized to date. First identified in Plasmodium [18], AMA1 was shown to be critical for merozoite invasion of red blood cell (RBC). Monoclonal antibodies (i.e. 4G2 and 1F9) against the extracellular domain of AMA1, or a short inhibitory peptide called R1 that was isolated by phage display [19] were shown to inhibit RBC invasion [13,20-22]. However, the mechanism of this inhibition was not clear until recently when AMA1 was found to interact with RON proteins to form the MJ. As a type I transmembrane protein stored in the microneme, AMA1 is released to the parasite plasma membrane at the onset of invasion [8]. Meanwhile, the RON2/4/5 complex is inserted into the host membrane [6,7] with RON2 spanning the membrane and the remaining RON proteins residing in the host cell cytosol [8] (Fig. 1). The transfer of this protein complex into the host cell may occur at the time of secretion, when transient breaks are thought to occur in the membrane coincident with secretion of rhoptry contents [23] (Fig. 1).

Recent studies revealed that previously characterized inhibitory antibodies against AMA1 or the R1 peptide block invasion by preventing the AMA1-RON interaction [13,21,24]. In the presence of these inhibitors, attachment of parasite to host surface is normal but the MJ does not form and invasion is prevented [14,22]. These data clearly demonstrate that the AMA1-RON interaction is critical for MJ formation and parasite invasion, at least for the blood stage of Plasmodium parasites. AMA1 is considered essential for Plasmodium merozoites and Toxoplasma tachyzoites as direct gene knockouts have not been obtained [10,25]. In Toxoplasma, conditional knock-down of AMA1 results in parasites that attach peripherally but are unable to invade host cells [10].

Several recent studies reported a direct interaction between AMA1 and RON2 in both Toxoplasma and Plasmodium [22,26-28], significantly advancing our understanding of the AMA1-RON interaction. Critical regions on both AMA1 and RON2 that mediate this interaction were also located through biochemical [26,28] and structural analyses [27]. This interaction is mediated by a short segment of about 50 amino acids between predicted transmembrane domains (TMD) 2 and 3 of RON2 that binds to a hydrophobic groove on the ectodomain of AMA1, where it is stabilized by hydrophobic and electrostatic interactions [27]. RON2-derived peptides that interact with AMA1 were shown to compete with the AMA1-RON2 interaction and block invasion [22,26-28]. Additionally, the inhibitory antibodies, and the R1 peptide mentioned above, were also shown to bind at or near the RON2 binding pocket on AMA1, therefore disrupting MJ formation and invasion [21,24]. All these results demonstrate that the AMA1-RON2 interaction is a crucial step in MJ formation and point to a model where the parasite inserts its own receptor (RON2) into the host cell plasma membrane and meanwhile displays a complementary ligand (AMA1) on its surface membrane to promote invasion. Interestingly, significant polymorphism occurs in both AMA1 and RON2; while the AMA1-RON2 pairing interaction is evolutionary conserved function the two proteins have co-evolved to promote species-specific interactions [26].

The specific molecular functions of RON proteins of the MJ are not well understood yet, because of their recent discovery and lack of recognizable motifs that suggest functions. RON2 is inserted into the host plasma membrane but its topology is enigmatic. Sequence analysis predicted three transmembrane helices, but experimental results suggest that the first predicted TMD probably does not span the membrane because the N-terminus of RON2 was shown to be cytoplasmic and the region between putative TMD2 and 3 was shown to be outside to interact with AMA1 [26,28]. Interestingly, the extreme C-terminus of RON2 downstream the putative TMD3 also interacts with AMA1, therefore it also needs to be extracellular [28]. To accommodate all these observations, it was proposed that RON2 spans the membrane only once with the predicted TMD2 being the only bona fide TM segment. RON4 is thought to be essential as attempts to knock it out were not successful [6]. In contrast, RON8 has been proved to be nonessential in T. gondii, although deletion of this gene severely impairs host cell attachment and invasion and also disorganizes the MJ components [29].

Challenging the role of AMA1 in the MJ

The composition of the MJ was questioned by a recent report [30], which implied that AMA1 is not part of the MJ but works independent of the RON proteins to increase invasion efficiency. When AMA1 was reduced to undetectable level using a stage-specific recombinase-mediated excision of the 3′ UTR, P. berghei sporozoites were able to invade hepatocytes normally, suggesting AMA1 is not required for sporozoite invasion. In contrast, merozoites differentiated from AMA1-depleted sporozoites failed to invade RBCs, indicating that AMA1 plays a more important role in merozoites [30]. In addition, these findings suggest that the invasion machinery may be different at the two stages of Plasmodium life cycle. Independently, RON4 was shown to be involved in Toxoplasma tachyzoites invasion and egress while AMA1 was only important for invasion [6], consistent with the idea that RON proteins can function independent of AMA1. Giovannini et al [6] also re-examined the distribution of AMA1 in Toxoplasma. Surprisingly they did not see AMA1 at the MJ of invading tachyzoites, in contrast to previous studies [6,14]. Using the conditional AMA1 knockout strain, they showed MJ can form (even though less frequently) without detectable AMA1 and those junctions that did form functioned normally during invasion. Based on these studies they proposed that AMA1, instead of being a structural component of MJ, helps the parasite to bind efficiently to the host cell and increases the frequency of successful MJ formation.

Although this alternative model provides support for some of the new observations, there are several previous findings that do not fit into this model. For example, RON2-derived peptides that competitively block the AMA1-RON2 interaction inhibit MJ formation even though host cell attachment is normal [14,22,26,27]. This finding strongly argues that AMA1 and RON2 have to interact to form the MJ. To help resolve this controversy, it would be interesting to see whether MJ can form and/or function in parasites expressing AMA1 or RON2 mutants that do not bind each other, guided by recent structural models of the interaction interface between these molecules [27].

Timing of MJ assembly

Sequential discharge of contents from micronemes and rhoptries is thought to be important for MJ establishment and subsequent invasion. However, the exact timing and how these molecular events are interconnected are largely unknown. Microneme secretion in T. gondii relies on calcium [31,32] and this step precedes rhoptry protein release [33]. Interestingly, deletion of MIC8 blocks both RON and ROP secretion in Toxoplasma, consistent with the idea of sequential release of these compartments [34]. In Plasmodium, transfer of merozoites from a high [K+] medium to low [K+] medium that mimics the release of merozoites from RBC to blood plasma leads to an increase in cytoplasmic [Ca2+], which then triggers the secretion of microneme proteins such as AMA1 to the surface [35]. After successful binding of micronemal adhesins to their host receptors (such as EBA175 to Glycophorin A), basal [Ca2+] is restored and rhoptry secretion is initiated [35]. Despite the sequential nature of microneme-rhoptry secretion, depletion of AMA1 in T. gondii does not affect RON secretion but reduces the secretion of ROP-containing evacuoles into the host cell [6,10], suggesting these steps are also governed by different mechanisms. Although ROP secretion is likely downstream of RON section, it does not require junction formation as peptides that block the AMA1-RON2 interaction inhibit MJ formation but not ROP secretion [22,28]. Future studies to define how these distinct steps are governed may provide key insights that could be exploited to block MJ formation and hence cell invasion.

Transactions at the MJ

During invasion, the MJ does not move but rather forms a fixed point of reference between the host and parasite membranes, and the parasite glides through this junction as it enters the cell (Fig. 1). The MJ may thus provide a point of traction, perhaps by bridging to the host cytoskeletal system. Even though the force for invasion is thought to be driven primarily by the gliding motility of the parasite [36], Gonzalez et al [37] reported the association of host actin and actin nucleators at the MJ of invading parasites. Based on these findings, they suggested that host actin dynamics are also important for invasion [37]. Alternatively, these data may indicate that the MJ needs to be anchored to existing host actin filaments, since perturbations of actin dynamics also affect the turnover of such stable structures. In this regard, it would be interesting to determine if any of the RON proteins contain F-actin binding motifs or if they interact with actin binding proteins that affect assembly and/or turnover. RON8 is a candidate for this role in T. gondii as when over-expressed in mammalian cells, RON8 goes to the periphery of the cell [29], suggesting it may interact with the cortical cytoskeleton.

Components at the MJ may also mediate important interactions to the parasite cytoskeleton. Previous studies have shown that the C-terminal tails of the secretory adhesins MIC2 and TRAP bridge to the parasite cytoskeleton by binding to aldolase [38,39] (Fig. 1). Mutants in aldolase that disrupt this interaction are impaired in invasion [40], as are mutants in the tail of MIC2 [41] or TRAP [42]. More recently, the C-terminal tail of AMA1 has been reported to bind to aldolase in Toxoplasma and Plasmodium [22,43] (Fig. 1). AMA1 mutants that do not bind aldolase fail to complement the AMA1 conditional knockout strain suggesting this interaction is vital in vivo as well [43]; however, it has not been determined if the MJ still forms normally with these mutants. Whether these two adhesive complexes represent distinct steps in invasion or provide redundant mechanisms for powering entry past the MJ and into the host cell is presently uncertain.

Proteolytic processing of AMA1

Although it may not occur exclusively at the MJ, AMA1 molecules are subject to cleavage within or near their transmembrane domains (Fig. 1). In Toxoplasma, rhomboid proteases TgROM4 and/or TgROM5 are thought to be responsible for the intramembrane cleavage of TgAMA1 as well as other adhesins [44-46]. Although both proteases appear to be essential, the consequence of their cleavage of AMA1 remains controversial. Over-expression of an enzyme-dead mutant of TgROM4 led to a dominant negative phenotype that did not block invasion but prevented intracellular parasite replication, and this defect was rescued by the tail of AMA1 [46]. According to this study, the only essential function of TgROM4 is to initiate parasite replication by releasing TgAMA1 tail from the membrane [46]. If this model is correct, it should be feasible to generate a clean TgROM4 knockout in parasites that express the cleaved tail of TgAMA1. In contrast, depletion of TgROM4 or TgAMA1 in conditional knockout strains results in inhibition of cell invasion but does not affect intracellular replication [10,45]. Complementing the TgAMA1 conditional knockout strain with an AMA1 mutant that is resistant to TgROM4/5 cleavage would help resolve whether intramembrane cleavage of TgAMA1 is required for invasion and/or replication. However, one limitation using these strains is that the depletion of ROM4 or AMA1 expression in the conditional knockout system is < 100% and hence residual expression may complicate the interpretations of observed phenotypes. Therefore, additional studies are needed to resolve the controversy regarding the functional consequence of AMA1 cleavage by rhomboids in T. gondii.

In Plasmodium, cleavage of AMA1 occurs mainly outside the membrane in a sequence-independent manner at a specific distance from the membrane [47] by the subtilisin-like protease SUB2 [48]. Limited intramembrane proteolysis of PfAMA1 also occurs but this processing is not essential for invasion or intracellular development. Recently, Olivieri et al [47] presented evidence that PfAMA1 cleavage by PfSUB2 is not required for AMA1 to function in invasion. Episomal expression of a SUB2-resistant form of AMA1 supported invasion of a strain whose endogeneous AMA1 was inhibited by the strain-specific R1 peptide. Interpretation of this study is complicated by the fact that the cell contains two copies of AMA1. The SUB2-resistant form is able to mediate MJ formation, while the endogenous form does not participate in junction formation but is still susceptible to cleavage. Interestingly, PfSUB2-meditated cleavage of PfAMA1 seems to be essential in blood-stage merozoites (possibly at a step after invasion) because it was not possible to replace the endogenous PfAMA1 with a mutant that is resistant to SUB2 processing [47]. These results suggest that cleavage of AMA1 plays a critical role at some yet undetermined step after Plasmodium invasion [47].

Conclusions

The discoveries of AMA1 and RON proteins at the MJ and the elegant structural studies elucidating the interactions between AMA1 and RON2 have significantly advanced our understanding of this novel interface. Future work is needed to refine its molecular architecture in more detail, especially to determine how the RON proteins interact and what roles they play in complex formation vs. the function of the MJ. Additionally, how and when the MJ components are assembled to make the junction are also of particular interest. Not all surface AMA1 molecules are at the MJ, and it will be important to distinguish the functions AMA1 that lies at the MJ as well as outside this. A full understanding of the MJ structure and its working mechanism may lead to novel therapeutic strategies that block parasite invasion and protect from apicomplexan infection.

Highlights.

-

➢

Apicomplexan parasites actively invade their host cell using actin-based motility

-

➢

Host cell attachment is mediated by proteins secreted from the apical complex

-

➢

Rhoptry neck (RON) proteins are inserted ontp the host cell membrane

-

➢

The parasite cell surface protein AMA1 binds to RON2 to form a tight junction

-

➢

Migration of the parasite past this “moving junction” results in cell entry

Acknowledgements

Supported in part from a grant from the National Institutes of Health (AI034036).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Dubremetz JF, Garcia-Reguet N, Conseil V, Fourmaux MN. Apical organelles and host-cell invasion by Apicomplexa. Int J Parasitol. 1998;28:1007–1013. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7519(98)00076-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sibley LD. How apicomplexan parasites move in and out of cells. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2010;21:592–598. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2010.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Suss-Toby E, Zimmerberg J, Ward GE. Toxoplasma invasion: The parasitophorous vacuole is formed from host cell plasma membrane and pinches off via a fusion pore. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:8413–8418. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.16.8413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morisaki JH, Heuser JE, Sibley LD. Invasion of Toxoplasma gondii occurs by active penetration of the host cell. J Cell Sci. 1995;108(Pt 6):2457–2464. doi: 10.1242/jcs.108.6.2457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aikawa M, Miller LH, Johnson J, Rabbege J. Erythrocyte entry by malarial parasites. A moving junction between erythrocyte and parasite. J Cell Biol. 1978;77:72–82. doi: 10.1083/jcb.77.1.72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alexander DL, Mital J, Ward GE, Bradley P, Boothroyd JC. Identification of the moving junction complex of Toxoplasma gondii: a collaboration between distinct secretory organelles. PLoS Pathog. 2005;1:e17. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0010017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lebrun M, Michelin A, El Hajj H, Poncet J, Bradley PJ, Vial H, Dubremetz JF. The rhoptry neck protein RON4 re-localizes at the moving junction during Toxoplasma gondii invasion. Cell Microbiol. 2005;7:1823–1833. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2005.00646.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Besteiro S, Michelin A, Poncet J, Dubremetz JF, Lebrun M. Export of a Toxoplasma gondii rhoptry neck protein complex at the host cell membrane to form the moving junction during invasion. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000309. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Straub KW, Cheng SJ, Sohn CS, Bradley PJ. Novel components of the apicomplexan moving junction reveal conserved and coccidia-restricted elements. Cell Microbiol. 2009;11:590–603. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2008.01276.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mital J, Meissner M, Soldati D, Ward GE. Conditional expression of Toxoplasma gondii apical membrane antigen-1 (TgAMA1) demonstrates that TgAMA1 plays a critical role in host cell invasion. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:4341–4349. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-04-0281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alexander DL, Arastu-Kapur S, Dubremetz JF, Boothroyd JC. Plasmodium falciparum AMA1 binds a rhoptry neck protein homologous to TgRON4, a component of the moving junction in Toxoplasma gondii. Eukaryot Cell. 2006;5:1169–1173. doi: 10.1128/EC.00040-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cao J, Kaneko O, Thongkukiatkul A, Tachibana M, Otsuki H, Gao Q, Tsuboi T, Torii M. Rhoptry neck protein RON2 forms a complex with microneme protein AMA1 in Plasmodium falciparum merozoites. Parasitol Int. 2009;58:29–35. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2008.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Collins CR, Withers-Martinez C, Hackett F, Blackman MJ. An inhibitory antibody blocks interactions between components of the malarial invasion machinery. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000273. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Riglar DT, Richard D, Wilson DW, Boyle MJ, Dekiwadia C, Turnbull L, Angrisano F, Marapana DS, Rogers KL, Whitchurch CB, et al. Super-resolution dissection of coordinated events during malaria parasite invasion of the human erythrocyte. Cell Host Microbe. 2011;9:9–20. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2010.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Charron AJ, Sibley LD. Molecular partitioning during host cell penetration by Toxoplasma gondii. Traffic. 2004;5:855–867. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2004.00228.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mordue DG, Desai N, Dustin M, Sibley LD. Invasion by Toxoplasma gondii establishes a moving junction that selectively excludes host cell plasma membrane proteins on the basis of their membrane anchoring. J Exp Med. 1999;190:1783–1792. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.12.1783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murphy SC, Samuel BU, Harrison T, Speicher KD, Speicher DW, Reid ME, Prohaska R, Low PS, Tanner MJ, Mohandas N, et al. Erythrocyte detergent-resistant membrane proteins: their characterization and selective uptake during malarial infection. Blood. 2004;103:1920–1928. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-09-3165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deans JA, Alderson T, Thomas AW, Mitchell GH, Lennox ES, Cohen S. Rat monoclonal antibodies which inhibit the in vitro multiplication of Plasmodium knowlesi. Clin Exp Immunol. 1982;49:297–309. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harris KS, Casey JL, Coley AM, Masciantonio R, Sabo JK, Keizer DW, Lee EF, McMahon A, Norton RS, Anders RF, et al. Binding hot spot for invasion inhibitory molecules on Plasmodium falciparum apical membrane antigen 1. Infect Immun. 2005;73:6981–6989. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.10.6981-6989.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hodder AN, Crewther PE, Anders RF. Specificity of the protective antibody response to apical membrane antigen 1. Infect Immun. 2001;69:3286–3294. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.5.3286-3294.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Richard D, MacRaild CA, Riglar DT, Chan JA, Foley M, Baum J, Ralph SA, Norton RS, Cowman AF. Interaction between Plasmodium falciparum apical membrane antigen 1 and the rhoptry neck protein complex defines a key step in the erythrocyte invasion process of malaria parasites. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:14815–14822. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.080770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Srinivasan P, Beatty WL, Diouf A, Herrera R, Ambroggio X, Moch JK, Tyler JS, Narum DL, Pierce SK, Boothroyd JC, et al. Binding of Plasmodium merozoite proteins RON2 and AMA1 triggers commitment to invasion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:13275–13280. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1110303108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Håkansson S, Charron AJ, Sibley LD. Toxoplasma evacuoles: a two-step process of secretion and fusion forms the parasitophorous vacuole. Embo J. 2001;20:3132–3144. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.12.3132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Collins CR, Withers-Martinez C, Bentley GA, Batchelor AH, Thomas AW, Blackman MJ. Fine mapping of an epitope recognized by an invasion-inhibitory monoclonal antibody on the malaria vaccine candidate apical membrane antigen 1. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:7431–7441. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610562200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Triglia T, Healer J, Caruana SR, Hodder AN, Anders RF, Crabb BS, Cowman AF. Apical membrane antigen 1 plays a central role in erythrocyte invasion by Plasmodium species. Mol Microbiol. 2000;38:706–718. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.02175.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *26.Lamarque M, Besteiro S, Papoin J, Roques M, Vulliez-Le Normand B, Morlon-Guyot J, Dubremetz JF, Fauquenoy S, Tomavo S, Faber BW, et al. The RON2-AMA1 interaction is a critical step in moving junction-dependent invasion by apicomplexan parasites. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1001276. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **27.Tonkin ML, Roques M, Lamarque MH, Pugniere M, Douguet D, Crawford J, Lebrun M, Boulanger MJ. Host cell invasion by apicomplexan parasites: insights from the co-structure of AMA1 with a RON2 peptide. Science. 2011;333:463–467. doi: 10.1126/science.1204988. Detailed structural information about the interactions between RON2 and AMA1 is provided by this structural study. The findings reveal the molecular basis for the interaction and help explain previous observations that inhibitory antibodies or the R1 peptide block invasion in Plasmodium.

- *28.Tyler JS, Boothroyd JC. The C-terminus of Toxoplasma RON2 provides the crucial link between AMA1 and the host-associated invasion complex. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1001282. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001282. Together with reference 26, these two studies provide evidence for the topology of RON2 in the host cell membrane and define the specific domains that interact with AMA1 at the MJ.

- 29.Straub KW, Peng ED, Hajagos BE, Tyler JS, Bradley PJ. The moving junction protein RON8 facilitates firm attachment and host cell invasion in Toxoplasma gondii. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002007. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *30.Giovannini D, Spath S, Lacroix C, Perazzi A, Bargieri D, Lagal V, Lebugle C, Combe A, Thiberge S, Baldacci P, et al. Independent roles of apical membrane antigen 1 and rhoptry neck proteins during host cell invasion by apicomplexa. Cell Host Microbe. 2011;10:591–602. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2011.10.012. This report challenges the current model that AMA1-RON2 interaction at the MJ is important for invasion by showing that Plasmodium sporozoites invade cells in the apparent absence of AMA1. They also dispute the previous claim that AMA1 is located at the MJ and question whether this interface is required for invasion in T. gondii.

- 31.Carruthers VB, Sibley LD. Mobilization of intracellular calcium stimulates microneme discharge in Toxoplasma gondii. Mol. Microbiol. 1999;31:421–428. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01174.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lourido S, Shuman J, Zhang C, Shokat KM, Hui R, Sibley LD. Calcium-dependent protein kinase 1 is an essential regulator of exocytosis in Toxoplasma. Nature. 2010;465:359–362. doi: 10.1038/nature09022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carruthers VB, Sibley LD. Sequential protein secretion from three distinct organelles of Toxoplasma gondii accompanies invasion of human fibroblasts. Eur J Cell Biol. 1997;73:114–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kessler H, Herm-Gotz A, Hegge S, Rauch M, Soldati-Favre D, Frischknecht F, Meissner M. Microneme protein 8--a new essential invasion factor in Toxoplasma gondii. J Cell Sci. 2008;121:947–956. doi: 10.1242/jcs.022350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Singh S, Alam MM, Pal-Bhowmick I, Brzostowski JA, Chitnis CE. Distinct external signals trigger sequential release of apical organelles during erythrocyte invasion by malaria parasites. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000746. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dobrowolski JM, Sibley LD. Toxoplasma invasion of mammalian cells is powered by the actin cytoskeleton of the parasite. Cell. 1996;84:933–939. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81071-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gonzalez V, Combe A, David V, Malmquist NA, Delorme V, Leroy C, Blazquez S, Menard R, Tardieux I. Host cell entry by apicomplexa parasites requires actin polymerization in the host cell. Cell Host Microbe. 2009;5:259–272. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2009.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Buscaglia CA, Coppens I, Hol WGJ, Nussenzweig V. Site of interaction between aldolase and thrombospondin-related anonymous protein in Plasmodium. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2003;14:4947–4957. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-06-0355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jewett TJ, Sibley LD. Aldolase forms a bridge between cell surface adhesins and the actin cytoskeleton in apicomplexan parasites. Mol Cell. 2003;11:885–894. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00113-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Starnes GL, Coincon M, Sygusch J, Sibley LD. Aldolase is essential for energy production and bridging adhesin-actin cytoskeletal interactions during parasite invasion of host cells. Cell Host Microbe. 2009;5:353–364. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2009.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Starnes GL, Jewett TJ, Carruthers VB, Sibley LD. Two separate, conserved acidic amino acid domains within the Toxoplasma gondii MIC2 cytoplasmic tail are required for parasite survival. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:30745–30754. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606523200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sultan AA, Thathy V, Frevert U, Robson KJ, Crisanti A, Nussenzweig V, Nussenzweig RS, Menard R. TRAP is necessary for gliding motility and infectivity of plasmodium sporozoites. Cell. 1997;90:511–522. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80511-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sheiner L, Santos JM, Klages N, Parussini F, Jemmely N, Friedrich N, Ward GE, Soldati-Favre D. Toxoplasma gondii transmembrane microneme proteins and their modular design. Mol Microbiol. 2010 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07255.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brossier F, Jewett TJ, Sibley LD, Urban S. A spatially localized rhomboid protease cleaves cell surface adhesins essential for invasion by Toxoplasma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:4146–4151. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407918102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *45.Buguliskis JS, Brossier F, Shuman J, Sibley LD. Rhomboid 4 (ROM4) affects the processing of surface adhesins and facilitates host cell invasion by Toxoplasma gondii. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000858. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000858. This report demonstrates that ROM4 is important for processing surface adhesins and that when its expression is supressed in T. gondii, motility is altered and invasion impaired.

- *46.Santos JM, Ferguson DJ, Blackman MJ, Soldati-Favre D. Intramembrane cleavage of AMA1 triggers Toxoplasma to switch from an invasive to a replicative mode. Science. 2011;331:473–477. doi: 10.1126/science.1199284. The paper revealed the surprsing finding that over-expression of dominant negative ROM4 had no effect on cell invasion but blocked intracellular replication of T. gondii. This report further suggested that ROM4 processing of AMA1 to release its cytoplasmic tail is essential to initiate replication.

- *47.Olivieri A, Collins CR, Hackett F, Withers-Martinez C, Marshall J, Flynn HR, Skehel JM, Blackman MJ. Juxtamembrane shedding of Plasmodium falciparum AMA1 Is sequence independent and essential, and helps evade invasion-inhibitory antibodies. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002448. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002448. This work demonstrates that the site of PfSUB2-mediated juxtamembrane cleavage of PfAMA1 is independent of the sequence but primarily determined by the distance from the membrane and that such cleavage plays a critical role after invasion of Plasmodium.

- 48.Harris PK, Yeoh S, Dluzewski AR, O’Donnell RA, Withers-Martinez C, Hackett F, Bannister LH, Mitchell GH, Blackman MJ. Molecular identification of a malaria merozoite surface sheddase. PLoS Pathog. 2005;1:241–251. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0010029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]