Abstract

Objective

Few intervention programs assist patients and their family caregivers to manage advanced cancer and maintain their quality of life (QOL). This study examined: 1) whether patient-caregiver dyads (i.e., pairs) randomly assigned to a Brief or Extensive dyadic intervention (the FOCUS Program) had better outcomes than dyads randomly assigned to usual care, and 2) if patients' risk for distress (RFD) and other factors moderated the effect of the Brief or Extensive Program on outcomes.

Methods

Advanced cancer patients and their caregivers (N=484 dyads) were stratified by patients' baseline risk for distress (high versus low), cancer type (lung, colorectal, breast, prostate), and research site, and then randomly assigned to a Brief (3-session) or Extensive (6-session) intervention or Control. The interventions offered dyads information and support. Intermediary outcomes were: appraisals (i.e., appraisal of illness/caregiving, uncertainty, hopelessness) and resources (i.e., coping, interpersonal relationships, and self-efficacy). The primary outcome was QOL. Data were collected prior to intervention and post-intervention (3 and 6 months from baseline). The final sample was 302 dyads. Repeated Measures MANOVA was used to evaluate outcomes.

Results

Significant Group by Time interactions showed there was improvement in dyads' coping (p<.05), self-efficacy (p<.05), and social QOL (p<.01), and in caregivers' emotional QOL (p<.05). Effects varied by intervention dose. Most effects were found at 3 months only. Risk for distress accounted for very few moderation effects.

Conclusions

Both Brief and Extensive programs had positive outcomes for patient-caregiver dyads, but few sustained effects. Patient-caregiver dyads benefit when viewed as the “unit of care.”

Keywords: Oncology, cancer, randomized clinical trial, family caregiver, advanced cancer, quality of life, intervention dose, risk for distress

Introduction

Although advanced cancer has serious detrimental effects on the quality of life (QOL) of patients and their family caregivers, few interventions have been developed to help them cope with advanced disease [1-3]. We identified four randomized clinical trials (RCTs) conducted with patient-caregiver dyads [4-7] and four with caregivers alone [8-11]. Some positive intervention effects were found for patients (e.g., less hopelessness, symptom distress, and depression) [6, 7, 12], and for caregivers (e.g., less burden, higher sleep quality, and better QOL) [8, 10], but studies often had low enrollment, high attrition, and varied considerably on the dose of the intervention (i.e., 2-10 sessions).

In a time of limited resources, more research is needed on what intervention dose (brief versus extensive) is necessary to have a positive effect on outcomes for advanced cancer patients and their caregivers. Research also needs to examine if patients' level of distress (high versus low) moderates the intervention's effect on outcomes. Patients with high distress and their caregivers may benefit from an extensive program that provides more time to discuss problems and obtain professional feedback, whereas patients with low distress and their caregivers may obtain benefits from a briefer program [9, 13].

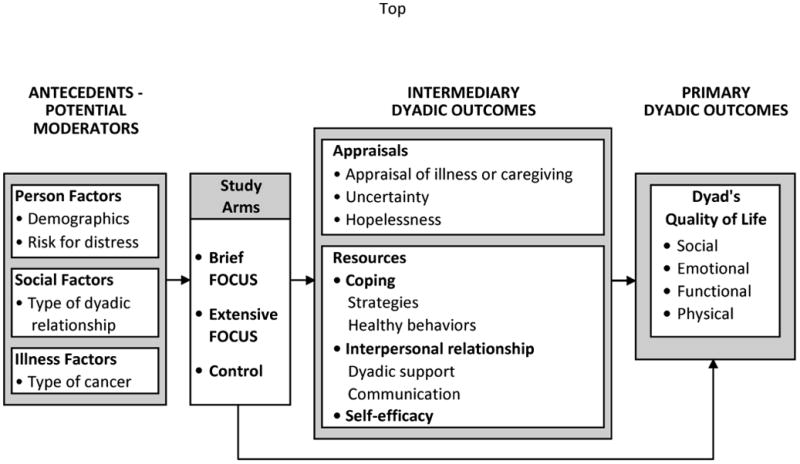

To our knowledge, no studies have examined intervention dose, risk for distress, and multiple outcomes in advanced cancer patients and their caregivers. Based on Stress-Coping Theory [14], this study had two aims: 1) to determine if patient-caregiver dyads, randomly assigned to either a Brief or Extensive dyadic intervention (i.e., the FOCUS Program), had better intermediary outcomes (i.e., less negative appraisals, increased resources), and better primary outcomes (i.e., improved QOL), than Control dyads receiving only usual care; and 2) to determine if risk for distress and other antecedent factors (e.g., gender, type of dyadic relationship, cancer type), moderated the effect of the Brief or Extensive Program on intermediary and primary outcomes (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Study model.

Methods

Participants

Patients were eligible if they were diagnosed with advanced breast, colorectal, lung or prostate cancer (i.e., Stage III or IV), and were within a six-month window of having a new advanced cancer diagnosis, progression of their advanced cancer, or change of treatment for it. Eligibility also included a life expectancy ≥ six months, age 21 or older, living within 75 miles of participating cancer centers, and having a family caregiver willing to participate. Caregivers were eligible if they were age 18 or older and identified by patients as their primary caregiver (i.e., provider of emotional and/or physical care). Family caregivers were excluded if they were diagnosed with cancer in the previous year or were receiving cancer treatment. A power analysis was conducted with PASS [15] software to determine the sample size needed to detect medium-sized differences in changes among the six subgroups (i.e., 3 arms × 2 risk levels). This indicated that a final sample of 324 patient-caregiver dyads was needed for a power of .80 at p<.05.

Procedures

Eligible dyads were informed about the study by clinic staff at four cancer centers. Dyads interested in the study were contacted by research staff, and if willing to participate, were scheduled for an initial home visit. During this visit, participants signed consent forms approved by Institutional Review Boards at the patient's cancer center and the University of Michigan (coordinating site), and then completed baseline questionnaires. Patients and caregivers completed questionnaire booklets separately, without discussion. At baseline, patients were screened for their risk for distress using the Risk for Distress Scale (RFD). Scores on the RFD ≥ 9 were designated high risk based on our previous research [16]. A stratified randomization process was used; dyads were stratified by patients' risk status (high or low), type of cancer (breast, colorectal, lung, prostate), and research site (four sites), and then randomly assigned in blocks of three to one of three arms: 1) Control condition (usual care), 2) Brief FOCUS Program, or 3) Extensive FOCUS Program.

Data were obtained at baseline prior to intervention (Time 1), following the intervention at three months after baseline (Time 2) and at six months after baseline (Time 3). The Brief and Extensive Programs were delivered in the home by primarily masters-prepared nurses during the three-month interval between baseline and Time 2 assessments. Data were collected by a separate team of research nurses blinded to dyads' group assignments.

Study Groups

Control Condition

All study participants received usual care at their cancer center, consisting of the medical treatment of cancer and symptom management. Psychosocial support was provided occasionally, but was not delivered routinely to patients or caregivers.

Experimental Condition

The original FOCUS Program was a home-based, dyadic intervention that provided information and support to cancer patients and caregivers together, as the unit of care [7, 17]. It addressed five content areas related to the acronym FOCUS: family involvement, optimistic attitude, coping effectiveness, uncertainty reduction, and symptom management. The FOCUS Program was tested in two prior RCTs with positive outcomes [7, 17]. Although prior participants reported high satisfaction with the program [18], some participants reported they would have preferred more sessions while others would have preferred fewer sessions.

To determine the optimal dose of the intervention, we revised the original five-session program into Brief and Extensive versions. The Brief FOCUS Program consisted of three contacts (two 90-minute home visits and one 30-minute phone session). The Extensive FOCUS Program consisted of six contacts (four 90-minute home visits and two 30-minute phone sessions). The content of both programs was the same, but the Brief program was condensed into 3.5 hours that required less participant and staff time. The Extensive program was 7 hours and allowed more time for discussion and review of content. Both programs were 10 weeks in duration, which enabled the initial post-intervention data collection to occur at 3 months from baseline for both experimental and control groups.

Intervention nurses received a 40-hour training program. To maintain intervention fidelity, nurses 1) completed a protocol checklist for either the Brief or Extensive program, 2) recorded the length of each session in minutes, and 3) tape-recorded randomly selected intervention sessions that were analyzed for adherence to protocols.

Fifty protocol checklists (25 brief and 25 extensive) were randomly selected and analyzed for adherence; 95% of all interventions listed in protocols were documented as implemented. The average length of the Brief (M=223 minutes, SD=65) and Extensive programs (M=348 minutes, SD=104) were significantly different (p<.001). Review of the audio-taped sessions indicated that nurses adhered to both protocol guidelines with high fidelity.

Instruments

Established instruments were used to measure study variables in Figure 1. Internal consistency reliability alphas were assessed at all three administrations and averaged (αM) (see Table 1).

Table 1. Patient and caregiver adjusted means by group over time.

|

|

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control (n = 104) |

Extensive (n = 99) |

Brief (n = 99) |

Group × Time | |||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||

| VARIABLES | (αM) | Baseline M (SD) |

3 Mo M (SD) |

6 Mo M (SD) |

Baseline M (SD) |

3 Mo M (SD) |

6 Mo M (SD) |

Baseline M (SD) |

3 Mo M (SD) |

6 Mo M (SD) |

F | |

| APPRAISAL | 0.99 a p =.46 |

|||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Appraisal | PT | 0.94 | 3.27 (0.66) |

3.12 (0.73) |

3.11 (0.77) |

3.18 (0.71) |

2.98 (0.72) |

3.04 (0.67) |

3.22 (0.73) |

3.09 (0.77) |

3.11 (0.79) |

|

| CG | 0.89 | 2.85 (0.53) |

2.77 (0.60) |

2.76 (0.59) |

2.81 (0.56) |

2.68 (0.55) |

2.71 (0.56) |

2.89 (0.48) |

2.79 (0.54) |

2.80 (0.53) |

||

|

|

||||||||||||

| Uncertainty | PT | 0.76 | 19.99 (4.19) |

18.87 (4.77) |

18.70 (4.97) |

20.30 (4.47) |

18.18 (4.94) |

18.33 (4.76) |

19.78 (4.91) |

18.45 (5.05) |

17.95 (4.58) |

|

| CG | 0.75 | 19.42 (5.01) |

19.04 (5.21) |

18.51 (5.03) |

20.05 (4.69) |

18.47 (4.81) |

18.17 (4.82) |

20.51 (4.30) |

18.87 (4.65) |

18.73 (4.58) |

||

|

|

||||||||||||

| Hopelessness | PT | 0.88 | 4.75 (4.30) |

4.42 (4.56) |

4.91 (5.47) |

4.57 (3.83) |

3.89 (3.63) |

4.44 (4.14) |

4.39 (3.77) |

4.10 (4.04) |

4.46 (4.10) |

|

| CG | 0.84 | 4.63 (3.93) |

4.63 (3.93) |

5.02 (4.73) |

4.46 (4.26) |

4.79 (4.18) |

4.51 (3.84) |

4.81 (4.16) |

4.12 (2.91) |

4.29 (3.05) |

||

|

| ||||||||||||

| COPING |

2.15

a p =.013* |

|||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Active Coping | PT | 0.87 | 2.84 (0.56) |

2.86 (0.58) |

2.80 (0.55) |

2.83 (0.54) |

2.76 (0.63) |

2.72 (0.59) |

2.88 (0.54) |

2.88 (0.51) |

2.81 (0.57) |

1.27 p =.28 |

| CG | 0.88 | 2.56 (0.56) |

2.56 (0.56) |

2.57 (0.57) |

2.60 (0.56) |

2.65 (0.50) |

2.57 (0.54) |

2.56 (0.52) |

2.71 (0.60) |

2.68 (0.54) |

||

|

|

||||||||||||

| Avoidant Coping | PT | 0.78 |

1.54 (0.48) |

1.54 (0.52) |

1.50 (0.54) |

1.45 (0.44) |

1.36 (0.42) |

1.41 (0.47) |

1.53 (0.52) |

1.47 (0.50) |

1.48 (0.47) |

2.53 p =.039* |

| CG | 0.78 |

1.48 (0.49) |

1.52 (0.54) |

1.49 (0.53) |

1.45 (0.45) |

1.35 (0.36) |

1.41 (0.48) |

1.58 (0.48) |

1.52 (0.46) |

1.52 (0.47) |

||

|

|

||||||||||||

| Healthy Lifestyle | PT | 0.61 |

28.22 (7.09) |

27.93 (6.67) |

27.56 (6.59) |

29.41 (6.33) |

28.99 (6.54) |

29.00 (6.79) |

27.97 (7.78) |

28.63 (6.91) |

27.49 (7.86) |

2.67 p =.031* |

| CG | 0.67 |

25.73 (8.41) |

26.07 (8.17) |

25.47 (7.96) |

28.02 (6.73) |

27.98 (7.80) |

27.78 (7.65) |

25.62 (8.02) |

27.80 (8.86) |

26.57 (8.03) |

||

|

| ||||||||||||

| INTERPERSONAL RELATIONSHIPS | 1.04 a p =.41 |

|||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Communication | PT | 0.94 | 3.57 (0.71) |

3.58 (0.78) |

3.57 (0.74) |

3.59 (0.68) |

3.61 (0.67) |

3.55 (0.69) |

3.62 (0.68) |

3.61 (0.66) |

3.64 (0.64) |

|

| CG | 0.93 | 3.56 (0.67) |

3.46 (0.73) |

3.44 (0.70) |

3.54 (0.62) |

3.57 (0.63) |

3.56 (0.60) |

3.51 (0.65) |

3.50 (0.66) |

3.47 (0.69) |

||

|

|

||||||||||||

| Dyadic Support | PT | 0.84 | 4.23 (0.73) |

4.26 (0.79) |

4.21 (0.69) |

4.29 (0.66) |

4.39 (0.56) |

4.27 (0.64) |

4.30 (0.64) |

4.31 (0.59) |

4.26 (0.59) |

|

| CG | 0.87 | 3.93 (0.81) |

3.77 (0.91) |

3.87 (0.80) |

4.05 (0.73) |

4.15 (0.67) |

4.02 (0.67) |

4.01 (0.70) |

3.96 (0.74) |

3.95 (0.75) |

||

|

| ||||||||||||

| EFFICACY | NAb | |||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Self-Efficacy | PT | 0.98 |

136.24 (28.17) |

133.18 (31.56) |

131.81 (33.48) |

131.92 (28.34) |

137.15 (24.83) |

131.00 (28.30) |

131.43 (33.62) |

133.04 (28.73) |

137.62 (25.75) |

2.84 p =.024* |

| CG | 0.98 |

134.99 (28.17) |

133.47 (34.69) |

134.06 (28.87) |

133.87 (26.38) |

134.25 (28.20) |

131.78 (29.16) |

130.73 (27.47) |

129.56 (28.41) |

129.56 (29.10) |

||

|

| ||||||||||||

| QOL DOMAINS | NAb | |||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Social | PT | 0.75 |

22.15 (5.76) |

21.84 (5.71) |

21.90 (5.49) |

22.52 (4.31) |

22.56 (3.88) |

22.15 (4.09) |

22.53 (4.85) |

23.10 (4.00) |

22.67 (4.23) |

4.28 p =.002** |

| CG | 0.83 |

19.83 (5.97) |

20.92 (6.28) |

19.73 (5.89) |

18.87 (5.44) |

20.91 (5.10) |

20.04 (5.56) |

19.73 (5.22) |

19.55 (5.22) |

19.67 (5.24) |

||

|

|

||||||||||||

| Emotional | PT | 0.85 | 16.12 (5.49) |

17.31 (5.06) |

16.95 (5.92) |

17.40 (5.19) |

18.39 (4.69) |

17.71 (5.05) |

16.97 (5.14) |

17.84 (5.04) |

17.09 (5.01) |

0.8 c p =.52 |

| CG | 0.81 | 14.81 (5.09) |

15.01 (5.60) |

14.74 (5.42) |

14.69 (5.36) |

15.78 (5.29) |

15.59 (5.52) |

12.90 (5.18) |

14.79 (4.74) |

13.97 (4.94) |

||

|

|

||||||||||||

| Functional | PT | 0.84 | 19.25 (6.10) |

19.78 (6.11) |

18.89 (6.46) |

18.57 (5.62) |

19.42 (5.53) |

19.06 (5.71) |

18.10 (5.76) |

19.01 (5.67) |

18.01 (6.44) |

0.35 p =.84 |

| CG | 0.84 | 18.87 (5.67) |

19.04 (5.76) |

19.05 (6.10) |

19.83 (5.71) |

20.18 (5.62) |

19.11 (6.02) |

18.25 (6.00) |

18.99 (5.37) |

19.07 (5.26) |

||

|

|

||||||||||||

| Physical | PT | 0.86 | 21.38 (5.89) |

21.58 (5.69) |

21.49 (5.76) |

19.72 (5.57) |

20.56 (5.30) |

20.03 (5.77) |

19.94 (5.77) |

19.72 (5.39) |

18.88 (6.59) |

1.16 p =.33 |

| CG | 0.81 | 23.96 (4.34) |

23.99 (4.52) |

24.55 (4.17) |

24.20 (3.96) |

24.33 (3.92) |

24.33 (3.66) |

24.29 (4.14) |

23.87 (4.16) |

24.84 (3.43) |

||

|

|

||||||||||||

p<.05

p<.01

αM = Reliability

PT = Patient

CG = Caregiver

Multivariate effect

NA: Not applicable - multivariate analysis not used; only univariate effects reported

No group × time effect; there was a group × time × role effect for caregivers only

Bold = significant group × time effect

Risk for Distress and Other Moderators

The risk of developing emotional distress in the future was measured at baseline with the 77-item Risk for Distress Scale (RFD), adapted from the original Omega Clinical Screening Interview [19]. The RFD assesses demographics, health history, current concerns, and symptom distress, and provides a composite risk score that ranges from 0-23; scores ≥ 9 were considered high risk based on our prior research [16]. Other potential moderators (e.g., dyadic relationship, cancer type) were assessed in a researcher-designed questionnaire.

Appraisal Variables

Appraisal of Illness and Caregiving were assessed with the Appraisal of Illness Scale (patients) and Appraisal of Caregiving Scale (caregivers) [20]. Uncertainty was measured with a brief version of the Mishel Uncertainty in Illness Scale [21]. Hopelessness was measured with the Beck Hopelessness Scale [22]. Higher scores indicated more negative appraisals, higher uncertainty, and more hopelessness.

Resource Variables

Coping strategies were assessed with the Brief Cope [23], factor analyzed into active coping and avoidant coping strategies consistent with our previous studies [24, 25]. Healthy behaviors were measured with a researcher-developed scale to assess activities that were encouraged in the intervention (e.g., exercise, nutrition, adequate sleep).

Dyadic support was measured with a modified version of the family support subscale of the Social Support Questionnaire [26]. Communication was measured with the Lewis Mutuality and Sensitivity Scale [27], which assessed dyads' illness-related communication. Self-efficacy was assessed with the Lewis Cancer Self-efficacy Scale [27].

Higher scores on coping subscales, healthy behaviors, communication, dyadic support, and self-efficacy indicated higher levels of these factors.

Quality of Life

Quality of life was measured with the general Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT-G) (version 4), a cancer-specific instrument that assessed QOL and four domains: social, emotional, functional, and physical well-being [28]. To assess how the intervention impacted QOL, we assessed the subscales of QOL separately. Caregivers completed a slightly modified version of the FACT-G that asked caregivers to report on their own QOL [3]. Higher scores indicated better QOL.

Data Analysis

The primary analyses for this study were to compare effects by intervention group. Secondary analyses examined effects of patient's risk level, our primary moderator. Because data involved both members of the dyad, analyses were performed at the dyad level (i.e., significant intervention effects would show that the intervention benefitted the dyad as a whole). In addition, we assessed possible differences in the efficacy of the intervention between patient and caregivers by testing interactions of role (patient vs. caregiver). Other key moderators were examined for possible effects on outcomes. Chi-square and ANOVA analyses were conducted to assess for differences among intervention and control groups at baseline. If differences were detected, these variables were used as covariates in subsequent analyses.

To assess intervention efficacy, repeated measures MANOVA were conducted. Role was modeled as a within subjects effect to account for the possible correlated nature of dyad data. Overall efficacy of the intervention was evaluated by assessing the Experimental Group (Control, Brief, Extensive) × Time (baseline, 3 months, 6 months) interaction. We assessed the possible moderating effects of role (patient vs. caregiver) by exploring the Experimental Group × Time × Role interaction. We assessed the possible moderating effects of level of risk for distress (low or high) by exploring the Experimental Group × Time × Level of Risk interaction. In addition, we tested for possible Experimental Group × Time × Role × Level of Risk interaction. Possible moderation by gender, type of dyadic relationship, and cancer type was also examined. Significant interactions were followed up with simple effects to examine the nature of the interactions. In order to reduce the number of tests conducted, we used multivariate analyses and grouped outcomes that were conceptually related: appraisal variables (appraisal of illness, uncertainty, hopelessness), coping variables (active coping, avoidant coping, healthy behaviors), and interpersonal variables (social support, communication). Self-efficacy was not obviously grouped with any of the other variables so it was assessed by itself. Similarly, the primary outcome domains of QOL were assessed separately. If the overall multivariate analysis was significant, we assessed the univariate analyses to determine what was driving the significance.

Results

Sample Description

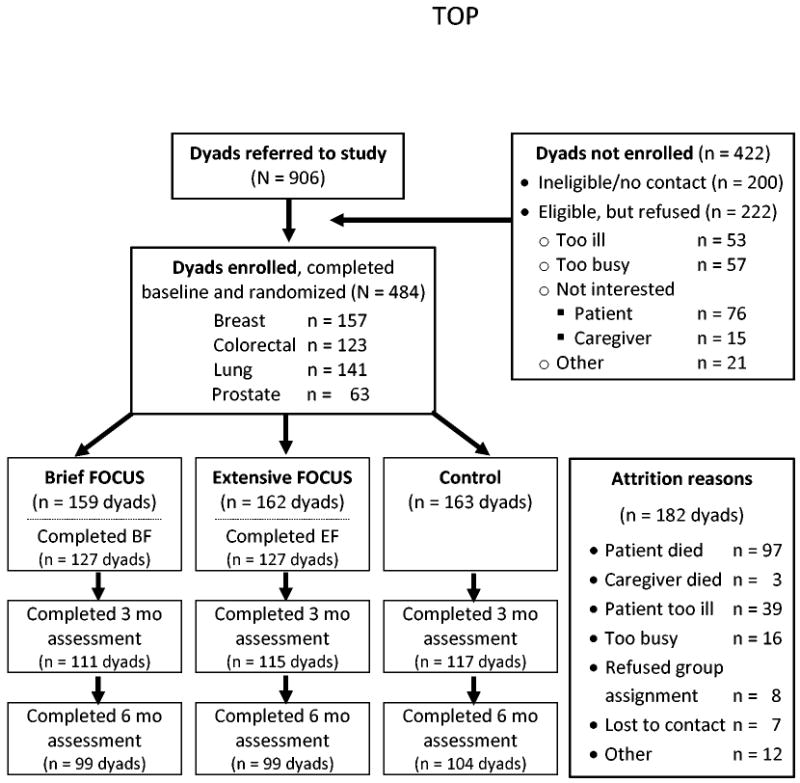

Over four years, 906 patient-caregiver dyads were referred to the study; 484 dyads completed baseline assessments (enrollment rate 68.6%), and were randomized; 343 dyads completed Time 2 assessments (70.9% retention); and 302 dyads completed Time 3 assessments (62.4% retention) (see Figure 2). At baseline, there were no significant differences in demographic (e.g., age, gender, socioeconomic status) or medical variables (e.g., cancer type, duration of advanced disease) among the three arms. There was no significant differential loss to follow-up among the three groups at 3 months (χ2(N=484; df=2)=0.05, p=.93) or 6 months, (χ2(N=484;df =2)=0.26, p=.88). No differences were found between patients or caregivers lost to follow-up and those retained in the study on demographic, medical, stratification variables, or baseline study variables (all p>.05).

Figure 2. Flow through RCT.

The average age of patients in the final sample was 60.5 years (SD=10.9; range 26-87); for caregivers, it was 56.7 (SD=12.6; range 18-88). Education averaged 14.8 years for patients and caregivers (SD=2.7; range 8-22 years). Racial composition was 82.5% Caucasian, 13.5% African-American, 1% Hispanic, 1.3% American Indian, 1.3% Asian, and 0.3% multi-racial. The majority of patients (61.4%) and caregivers (55.8%) were female. Most caregivers were spouses (74%). At baseline, approximately half of the patients were at high risk for distress (56%).

Most patients had breast cancer, followed by lung, colorectal, and prostate cancer (see Figure 2). The average time since original diagnosis was 47 months. Sixty-six percent were currently receiving chemotherapy, 23% hormones, 8% radiation, 4% surgery, and 6% followed with watchful waiting (multiple responses were possible). Patients (72%) and caregivers (66%) had co-morbid conditions, most commonly hypertension and heart problems. The groups did not differ significantly on changes in treatment or progression of disease (all ps>.05) indicating no potential confound of treatment change by condition.

Despite randomization, group differences can emerge. Therefore, we examined differences among the three groups at baseline. Baseline differences were found for patient appraisal, patient uncertainty, patient and caregiver hopelessness, patient communication, and patient and caregiver dyadic support (all ps<.05). These variables were controlled for in all subsequent analyses.

Major Study Outcomes

Table 1 provides adjusted means for patients and caregivers in the three groups at baseline, 3-month, and 6-month assessments, controlling for the variables that differed among groups at baseline. There were no differential changes among groups on appraisal variables (appraisal of illness, uncertainty, hopelessness), and interpersonal variables (communication, dyadic support). However, there was a significant Group × Time effect on coping variables, F=2.15, p=.013. Univariate analyses showed this was primarily due to effects on avoidant coping, F=2.53, p=.039, and healthy behaviors, F=2.67, p=.031. Simple effects showed that Control dyads' avoidant coping did not change significantly from baseline to 3-month or 6-month follow-ups. In contrast, dyads in the Extensive group (p=.001) and Brief group (p=.033) had a significant decrease in their use of avoidant coping from baseline to 3 months. This significant effect was maintained only for dyads in the Brief group at 6 months (p=.045). For healthy behaviors, there were no significant changes for Control or Extensive dyads at 3 or 6-month follow-ups. However, Brief dyads showed a significant increase in their use of healthy behaviors at 3-months (p=.001), but it was not maintained at 6 months.

Also, there was a significant Group × Time effect on self-efficacy, F =2.84, p=.024. Simple effects showed that Control and Brief dyads' self-efficacy did not change significantly from baseline to 3-month or 6-month follow-ups. In contrast, Extensive dyads' self-efficacy significantly increased at 3 months (p=.041), but was not maintained at 6 months.

There was a significant Group × Time effect for social QOL, F=4.28, p=.002. Simple effects showed that Control dyads had a significant decline in their social QOL at 3-months (p=.001) while Extensive and Brief dyads maintained their social QOL at 3-month or 6-month follow-ups. Table 2 summarizes the significant Group × Time effects for dyads.

Table 2. Summary of significant effects for patient-caregiver dyads.

| Group | Control | Brief | Extensive | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assessment in Months | 3 m | 6 m | 3 m | 6 m | 3 m | 6 m |

| Avoidant Coping | — | — | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | — |

| Healthy Behaviors | — | — | ↑ | — | — | — |

| Self-Efficacy | — | — | — | — | ↑ | — |

| Social QOL | ↓ | — | — | — | — | — |

| Emotional QOL | — | — | ↑a | ↑a | ↑a | ↑a |

Effects for caregivers only

Moderator Effects

We found a Group × Time × Role interaction for emotional QOL, F=2.50, p=.042. Simple effects showed that for patients there was a significant increase in emotional QOL for Control, Extensive, and Brief patients at the 3-month follow-up (all ps <.05). However, for caregivers, there was no significant change in Control caregivers' emotional QOL at 3-month and 6-month follow-ups while there was a significant increase in Extensive and Brief caregivers' emotional QOL at 3 months (all ps<.01), which was sustained to 6-month follow-ups (all ps<.05).

We also found a Group × Time × Risk interaction for the interpersonal variables, F=2.66, p=.007. Inspection of the univariate effects showed that this was driven primarily by differences in dyadic support, F=2.72, p=.029. Simple effects showed that low risk dyads' social support significantly decreased at the 3-month (p=.036) and 6-month (p=.003) follow-ups. However, this decrease was not observed in the high-risk Controls, Extensive, or Brief dyads.

We found a Group × Time × Risk × Role interaction for the interpersonal variables, F=1.99, p=.045. Inspection of the univariate effects showed that this was primarily for communication, F=2.72, p=.029. Simple effects showed no changes for patients regardless of risk level and intervention condition. However, low risk caregivers in the Control group showed a significant decrease in communication at 3-month (p=.010) and 6-month follow up (p=.014). The high-risk Controls, Extensive, and Brief caregivers did not change in their communication.

We also examined whether type of dyadic relationship (spouse versus non-spouse), cancer type (four types), and gender moderated the effect of the intervention on outcomes. No moderation effects were found.

Discussion

Intervention dose and outcomes

We examined the effects of two doses of the FOCUS intervention on outcomes for advanced cancer patients and their family caregivers. Intervention effects were limited in number and duration; most effects occurred at 3-months follow-up only, just after completion of the intervention. Nevertheless, patients and their caregivers who participated in the Brief or Extensive FOCUS Programs had more improvement on study outcomes than dyads in the Control group (see Table 2).

Since the Brief and Extensive programs had nearly the same number of effects, we cannot say that one intervention dose was better than the other for dyads facing advanced cancer. Instead, findings suggest that the optimal intervention dose may depend on which outcome is targeted for change. The Extensive 6-session program significantly improved dyads' self-efficacy or confidence in their ability to manage the illness and the caregiving associated with it, suggesting that longer interventions may be needed to improve self-efficacy. The Brief 3-session program, on the other hand, was sufficient to improve both caregivers' and patients' use of healthy behaviors (nutrition, exercise) during a time when caregivers often neglect their own health, while the patient's condition is deteriorating. Both the Extensive and Brief Program helped dyads cope more effectively by decreasing their use of avoidant coping (i.e., denial), which is often related to poorer adjustment to cancer [24]. Both programs also helped dyads maintain their social quality of life (i.e., support from family and friends).

We found a significant Time × Group × Role effect on emotional QOL for Brief and Extensive caregivers at 3 and 6-month follow-ups, but no change for Control caregivers. Including caregivers in the intervention made it possible for them to address their own concerns, receive support, and improve their emotional QOL. Brief and Extensive patients also had an increase in their emotional QOL, but since this improvement occurred in Control patients also, the change cannot be attributed to the interventions. It is possible that advanced cancer patients, in general, perceive more emotional support from others including clinic staff which helps to improve their emotional QOL. Their caregivers, on the other hand, seldom perceive support from others [29], and hence, appear to derive more benefit from the interventions. It is also possible that completing baseline surveys may have sensitized Control patients to address their emotional needs.

We found no intervention effects for appraisal variables (e.g., uncertainty). It may be difficult to reduce dyads' negative appraisals during advanced cancer, as the disease progresses and cure is not possible. However, in our prior RCTs with dyads facing recurrent breast cancer [7] and with couples facing newly diagnosed and advanced prostate cancer [17], we did obtain a significant improvement on appraisal variables. The lack of effect in this study may be due to the sizeable number of dyads dealing with advanced lung cancer, which is often viewed as a more threatening and rapidly progressing cancer than breast or prostate cancer. [13]

While some positive intervention effects were found, the effects on most outcomes were not sustained at 6-month follow-up. It may be more difficult to sustain intervention effects as the patient's illness progresses and demands on caregivers increase. Programs that are incorporated into standard care to provide ongoing information and support for dyads' changing needs, may be more effective in sustaining intervention effects. The lack of sustained effects may also be related to the decrease in our sample size at 6 months. By six months, 16% of the patients had died and others were too ill to complete questionnaires. Our final sample at 6-months was 302 dyads instead of our target of 324 dyads; hence our power was lower (.75-.76) than desired (.80) for these analyses, making it difficult to detect small intervention effects if they existed.

Risk Status and Outcomes

This study also examined if patients' baseline risk for distress (high or low) had a differential effect on outcomes for patient-caregiver dyads. We expected that high risk patients and their caregivers would benefit more from the Extensive program, but that was not the case. Patients' initial risk for distress moderated only two outcomes, and both pertained to interpersonal variables with participants in the Control group. Specifically, low risk dyads in the Control group reported a significant decrease in their dyadic support, and low risk Control caregivers reported a significant decrease in their dyadic communication. It is possible that low risk Control dyads perceived less of a need to offer one another support or engage in illness-related communication. In contrast, Brief and Extensive dyads may have attended to their interpersonal relationships, which was encouraged in intervention programs, and were able to maintain their dyadic support and communication, especially from the perception of the caregiver.

The limited moderation effects by risk status may suggest that just because dyads are identified at high risk for poorer outcomes, it does not necessarily mean they will obtain more benefit from a time-limited program than low-risk dyads. Patients and caregivers may need some basic personal, social and/or economic resources to benefit from a time-limited intervention (18). Since only two studies to our knowledge have examined risk status and outcomes during advanced cancer [5, 11], and neither study found intervention effects for these high risk families or caregivers in their primary analyses, the relationship between high risk status and intervention outcomes is not clear and needs further research.

There are limitations to this study. First, only patients' risk status (i.e., high versus low) were used as a stratification variable, assuming they were more likely to be assessed in practice settings. Findings may have differed if a combined patient-caregiver risk score had been used, or if patients' actual risk scores had been used (a continuous variable) instead of their high/low risk status (a categorical variable). Second, we measured risk for distress instead of current distress which may have affected findings. Third, it would have been beneficial if we had collected information on patients' performance status over time which may have helped explain study findings.

This study has implications for practice. Findings suggest that when interventions are offered to advanced cancer patients and their family caregivers together as the unit of care, both individual's coping ability, self-efficacy, and aspects of their QOL can be maintained or even improved. In current practice, only patients' needs are routinely addressed; caregivers often are left on their own to obtain information and support to deliver complex care in the home. Our findings also indicate that shorter interventions requiring less professional resources may achieve some of these outcomes.

Research challenges that remain include the following: identifying ways to help high risk patients and their caregivers, targeting interventions to address dyadic needs as well individual needs of patients and caregivers, determining how to implement dyadic interventions in practice settings, finding ways to sustain positive intervention effects, and developing modes of delivery (e.g., the Internet) that will enable more patients and caregivers to benefit from psychosocial interventions at a lower cost.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by NCI (R01CA107383) with additional funds from Fashion Footwear Charitable Foundation of NY/QVC Presents Shoes on Sale™ and the University of Michigan Comprehensive Cancer Center, Office of Research and Sponsored Programs, and School of Nursing

Footnotes

The authors have no conflict of interests pertaining to any aspect of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Frost MH, et al. Physical, psychological and social well-being of women with breast cancer: the influence of disease phase. Psycho-Oncol. 2000;9(3):221–31. doi: 10.1002/1099-1611(200005/06)9:3<221::aid-pon456>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hagedoorn M, et al. Distress in couples coping with cancer: A meta-analysis and critical review of role and gender effects. Psychol Bull. 2008;134(1):1–30. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.134.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Northouse LL, et al. Quality of life of women with recurrent breast cancer and their family members. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20(19):4050–4064. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.02.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Keefe FJ, et al. The self-efficacy of family caregivers for helping cancer patients manage pain at end-of-life. Pain. 2003;103:157–162. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(02)00448-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kissane DW, et al. Family focused grief therapy: A randomize controlled trial in palliative care and bereavement. Am J of Psychiatry. 2006;163(7):1208–1218. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.7.1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McCorkle R, et al. The effects of home nursing care for patients during terminal illness on the bereaved's psychological distress. Nurs Res. 1998;47(1):2–10. doi: 10.1097/00006199-199801000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Northouse L, et al. Effects of a family intervention on the quality of life of women with recurrent breast cancer and their family caregivers. Psycho-Oncol. 2005;14:478–491. doi: 10.1002/pon.871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carter PA. A brief behavioral sleep intervention for family caregivers of persons with cancer. Cancer Nurs. 2006;29(2):95–103. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hudson PL, Aranda S, Hayman-White K. A psycho-educational intervention for family caregivers of patients receiving palliative care: A randomized controlled trial. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2005;30(4):329–341. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2005.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McMillan SC, Small BJ, Weitzner M, Schonwetter R, Tittle M, Moody L, Haley W. Impact of coping skills intervention with family caregivers of hospice patients with cancer. Cancer. 2006;106:214–222. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Walsh K, et al. Reducing emotional distress in people caring for patients receiving specialist palliative care. Br J of Psychiatry. 2007;190:142–147. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.023960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McMillan SC, Small BJ. Using the COPE intervention for family caregivers to improve symptoms of hospice homecare patients: A clinical trial. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2007;34:313–321. doi: 10.1188/07.ONF.313-321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zabora J, et al. The Prevalence of Psychological Distress by Cancer Site. Psycho-Oncology. 2001;10:19–28. doi: 10.1002/1099-1611(200101/02)10:1<19::aid-pon501>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lazarus RS, Folkman S, editors. Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer; New York: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hintz JL. PASS 2000 User's Guide. Kaysville, Utah: Number Cruncher Statistical Systems; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Northouse LL, et al. Living with prostate cancer: Patients' and spouses' psychosocial status and quality of life. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:4171–4177. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.6503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Northouse LL, et al. Randomized clinical trial of a family intervention for prostate cancer patients and their spouses. Cancer. 2007;110:2809–2818. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harden J, Falahee M, Bickes J, Schafenacker A, Walker J, Mood D, Northouse L. Factors associated with prostate cancer patients' and their spouses' satisfaction with a family intervention. Cancer Nurs. 2009;32:482–492. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e3181b311e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Worden JW. Psychosocial screening of cancer patients. J Psychosoc Oncol. 1983;1:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oberst MT. Appraisal of Illness Scale: Manual for Use. Detroit: Wayne State University; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mishel M, Epstein D. Uncertainty in Illness Scales: Manual. Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beck AT, et al. The measurement of pessimism: the hopelessness scale. J Consult & Clin Psychol. 1974;42(6):861–5. doi: 10.1037/h0037562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carver CS. You want to measure coping but your protocol's too long: Consider the Brief COPE. Int J of Behavio Med. 1997;4(1):92–100. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm0401_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kershaw T, et al. Longitudinal analysis of a model to predict quality of life in prostate cancer patients and their spouses. Ann Behav Med. 2008;36:117–128. doi: 10.1007/s12160-008-9058-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kershaw T, et al. Coping strategies and quality of life in women with advanced breast cancer and their family caregivers. Psychol Health. 2004;19:139–155. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Northouse LL. Social support in patients' and husbands' adjustment to breast cancer. Nurs Res. 1988;37(2):91–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lewis FM. Family Home Visitation Study Final Report. National Cancer Institute, National Intitutes of Health; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cella D, et al. The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy Scale:Development and validation of the general measure. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11(3):570–579. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.3.570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bishop MM, et al. Late effects of cancer and hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation on spouses or partners compared with survivors and survivor-matched controls. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1403–1411. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.5705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]