Abstract

Nanoscale drug delivery vehicles have been extensively studied as carriers for cancer chemotherapeutics. However the formulation of platinum chemotherapeutics in nanoparticles has been a challenge arising from their physicochemical properties. There are only few reports describing oxaliplatin nanoparticles. In this study, we derivatized the monomeric units of a polyisobutylene maleic acid copolymer with glucosamine, which chelates trans-1,2-diaminocyclohexane (DACH) platinum (II) through a novel monocarboxylato and O→Pt coordination linkage. At a specific polymer to platinum ratio, the complex self assembled into a nanoparticle, where the polymeric units act as the leaving group, releasing DACH-platinum in sustained pH-dependent manner. Sizing was done using dynamic light scatter and electron microscopy. The nanoparticles were evaluated for efficacy in vitro and in vivo. Biodistribution was quantified using inductive-coupled plasma-atomic absorption spectroscopy (ICP-AAS). The PIMA-GA-DACH-platinum nanoparticle was found to be more active than free oxaliplatin in vitro. In vivo, the nanoparticles resulted in greater tumor inhibition than oxaliplatin (equivalent to 5mg/kg platinum dose) with minimal nephrotoxicity or body weight loss. ICP-AAS revealed significant preferential tumor accumulation of platinum with reduced biodistribution to the kidney or liver following PIMA-GA-DACH-platinum nanoparticle administration as compared with free oxaliplatin. These results indicate that the rational engineering of a novel polymeric nanoparticle inspired by the bioactivation of oxaliplatin results in increased antitumor potency with reduced systemic toxicity compared with the parent cytotoxic. Rational design can emerge as an exciting strategy in the synthesis of nanomedicines for cancer chemotherapy.

Keywords: Oxaliplatin, Nanoparticle, Cancer

Platinum (Pt)-based drugs form the first or second line therapy for most types of cancer. Cisplatin, for example, is used in testicular, ovarian, lung, head and neck, and is recently being tested in triple negative breast cancer [1, 2]. However, the use of cisplatin is dose limited primarily due to nephrotoxicity [3]. Efforts in overcoming this limitation led to the development of carboplatin, where the platinum is chelated to a cyclobutane-1,1-dicarboxylato leaving group, and undergoes hydration more slowly than cisplatin [4]. Approximately two orders of magnitude higher concentrations of carboplatin are therefore required to attain DNA platination levels similar to cisplatin [5]. Furthermore, carboplatin also exhibits cross resistance with cisplatin [6]. Interestingly, another cisplatin analogue, oxaliplatin, has no cross-resistance with cisplatin, and is currently used in colorectal cancer [6, 7]. The bulky trans-1,2-diaminocyclohexane (DACH) ring of oxaliplatin adduct (Fig.1a) fills much of the DNA major groove, and as a result is more efficient than cisplatin per equal number of DNA adducts in inhibiting DNA chain elongation [8]. However, as in the case of carboplatin, the aquation of oxaliplatin to form the DNA-reactive species, ([Pt(R,R-DACH)(H2O)2]2+, is a slower process than the hydrolysis of cisplatin [5]. While the sites on the DNA to which cisplatin and oxaliplatin form adducts are identical, the latter is inherently less able to form DNA adducts as compared with cisplatin [9,10]. In a recent study, we have defined a novel monocarboxylato and O→Pt linkage as an optimal coordination environment for the leaving group that results in faster release of DNA-reactive adducts as compared with the dicarboxylato linkages between the leaving group and platinum in the case of carboplatin [11]. We hypothesized that a such modified leaving group that undergoes hydration faster than the oxalate group of oxaliplatin can result in increase in the potency of oxaliplatin while retaining the inherent advantages of the bulky trans-1,2-diaminocyclohexane (DACH) ring of oxaliplatin adduct. Furthermore, we rationalized that integrating this novel structure into a platform that enables preferential homing to the tumors could further improve the antitumor outcome.

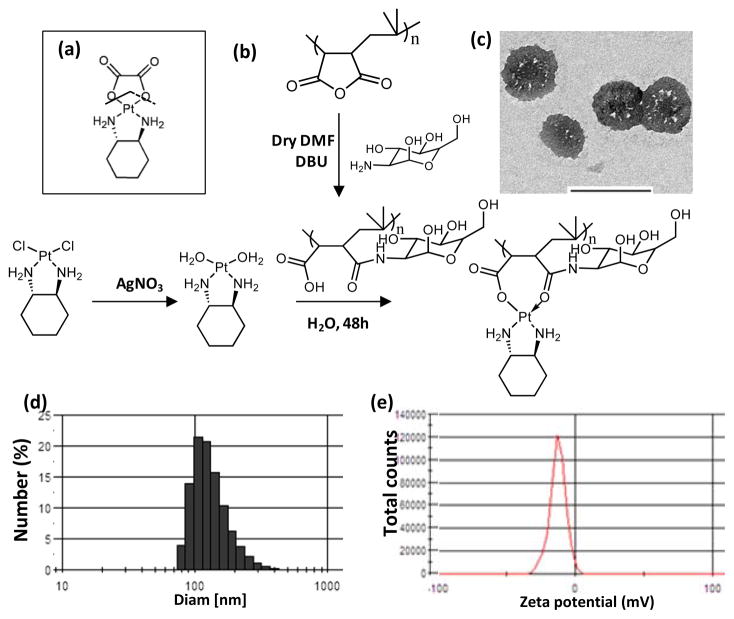

Fig 1. Structure activity-inspired engineering of oxaliplatin nanoparticle.

(a) Chemical structure of oxaliplatin. The broken lines demarcate the leaving group. (b) Scheme shows the chemical synthesis of PIMA-GA-DACH-platinum complex. Conjugation of PIMA with glucosamine, followed by complexation introduces a monocarboxylato and O→Pt coordinate linkage between the copolymer and Pt of DACH-platinum. (c) High-resolution transmission electron micrographs show the morphology of PIMA-GA-oxaliplatin nanoparticles formed. Bar= 500 nm. (d) Plot shows the size distribution of nanoparticle measured using a dynamic laser light scatter. (e) Graph shows zeta potential of a representative sample of nanoparticles suspended in double distilled water.

Nanoscale drug delivery vehicles have been extensively studied as carriers for bioactive compounds, and several nanocarriers for cancer chemotherapeutics are already in the clinics [12–15]. Nanoparticles can preferentially home into tumors passively through the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect that arises from leaky vasculature and impaired lymphatic drainage within the tumor [16]. However, formulation of platinum chemotherapeutics in nanoparticles has been a challenge arising from their physicochemical properties [17, 18]. For example, while a liposomal formulation of cisplatin was found to deliver higher levels of platinum to the tumor [19], it failed to exhibit clinical advantages presumably from suboptimal carrier design that required high concentrations of lipids [20]. Alternative strategies by complexing cisplatin to polymeric carriers have also been harnessed [21]. Interestingly, there are only few reports of nanoparticles of oxaliplatin for cancer chemotherapy. Recent preclinical and phase 1 studies with liposomal oxaliplatin have been reported [22,23] but the efficacy it will offer over free oxaliplatin in the clinics in the light of the experiences with cisplatin remains to be seen. In another study, Duncan and coworkers developed a hydroxypropylmethacrylamide-based polymer, where the cisplatin was linked via an ethylenediamine or an amidomalonate chelating group and a tetrapeptide linker [24]. In a subsequent version (AP5346), the same polymeric construct was used to chelate DACH-platinum [25]. In a recent study, gold nanoparticles functionalized with a thiolated polyethylene glycol capped with a carboxylate group were used to deliver oxaliplatin [26]. However, in this case the platinum was chelated to the gold nanoparticle through a dicarboxylato linkage, while in AP5346 the platinum is chelated to an amidomalonato linkage, both of which we have recently demonstrated as being more stable than an monocarboxylato and O→Pt linkage [11]. Here we demonstrate for the first time that the complexation of DACH-platinum to a novel polyisobutylene-maleic acid (PIMA)-glucosamine copolymer via the more optimal monocarboxylato and O→Pt linkage results in the self assembly into a sub 200 nm nanoparticle at a fixed Pt to polymer ratio. Furthermore, this rationale introduction of a novel complexation environment enhances the potency of oxaliplatin, and resulting in increased antitumor efficacy as well as therapeutic index in vivo, highlighting the need to integrate structure activity relationships in the design of next generation nanomedicines for cancer chemotherapy..

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents

CellTiter 96 Aqueous One Solution Cell Proliferation Assay [3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium, inner salt (MTS) assay] reagent was from Promega (Madison, WI). Commercially supplied (Sigma, Fluka AG, Aldrich Chemie GmbH) chemicals (reagent grade) were used as received. These included, dimethylformamide (DMF), glucosamine.HCl, cyclohexanediamineplatinum(II) chloride, poly(isobutylene--maleic anhydride), and triethyl amine. All polymer solutions were dialyzed in cellulose membrane tubing, (Spectra/Por 4 and Spectra/Por 6, wet tubing), with mass-average molecular mass cut-off limits of 1 KDa and 3.5–5 KDa respectively. Operations were performed against several batches of stirred deionized H2O. 1H NMR and 13C NMR were measured at 500 and 125 MHz, respectively, with a Varian-500 or a Brucker-400 spectrometer. 1H NMR chemical shifts are reported as δ values in parts per million (ppm) relative to either tetramethylsilane (0.0 ppm) or deuterium oxide (4.80 ppm). 195Pt NMR chemical shifts are reported as δ values in parts per million (ppm) relative to Na2PtCl6 (0.0 ppm). 13C chemical shifts are reported in ppm relative to DMSOd6 (39.5 ppm). Starting materials were azeotropically dried prior to reaction as required and all air- and/or moisture-sensitive reactions were conducted in flame- and/or oven-dried glassware under an anhydrous nitrogen atmosphere with standard precautions taken to exclude moisture.

Synthesis of DACH-platinum nanoparticle

To obtain PIMA-glucosamine (PIMA-GA) copolymer, poly(isobutylene-alt-maleic anhydride) (0.045 g, 0.0075 mmol) was dissolved in DMF (5 mL). In another vial DBU (0.23 mL, 1.5 mmol) was mixed with glucosamine (0.323 g dissolved in 5 mL dry DMF, 1.5 mmol) stirred at 25 °C for 3h. The vial containing poly(isobutylene-alt-maleic anhydride) was then added to glucosamine-DBU solution. The resulting reaction mixture was allowed to stir at room temperature for 48 h and then quenched by adding double distilled water (1mL). The organic solvent was evaporated under vacuum. The resulting pale yellow solid was purified by dialysis for 3 days using dialysis bag of molecular cut off of 3.5KDa to colorless solution. Lyophilization gave 104 mg of white colored PIMA-GA polymer. 1H-NMR (300 MHz, D2O) δ 8.2–8.3 (m), 7.0–7.1 (m), 5.0–5.1 (m), 3.0–3.9 (m), 2.1–2.3 (m), 1.1–1.9 (m), 0.7–1.0 (m). For aquation of DACH-platinum(II), cyclohexanediamineplatinum(II) chloride (38mg) and AgNO3 (17mg) was added to 10ml double distilled water. The resulting solution was stirred in dark at room temperature for 24h. AgCl precipitates were removed from reaction by centrifugation at 10000 rpm for 10 min. The supernatant was further purified by passing through 0.2μm filter. To engineer PIMA-GA-cyclohexanediamine platinum (II) (DACH-platinum) nanoparticles, 1ml double distilled water containing aquated DACH-platinum (0.0033 mmol) was added to PIMA-GA (0.0003 mmol) weighed in 10 mL RB flask equipped with magnetic stirrer, and then the solution was stirred at room temperature (25°C) for 48h. The PIMA-GA-DACH-platinum conjugate formed in solution was further purified by dialysis to remove unattached DACH-platinum with mass-average molecular mass cut-off limit of 1KDa. Lyophilization of the dialyzed solution resulted in light yellow colored PIMA-GA-DACH-platinum conjugate, which self assembled into nanoparticles when suspended in double distilled water.

Synthesis of fluorescein-labeled cyclohexanediamineplatinum nanoparticles

FITC-EDA conjugate was synthesized by stirring fluorescein isothiocyanate in excess ethylene diamine at 25°C for 48 h in DMSO. Poly(isobutylene--maleic anhydride (0.006 g) was dissolved in DMF (5 mL). A solution of DBU (0.0053 mL in DMF) and glucosamine (0.0075 g dissolved in 5 mL dry DMF) was then added to the above solution. The mixture was stirred at 25°C for 1h, to which 0.0022 g FITC-EDA was added and stirred for another 48 h. The reaction mixture was quenched by adding double distilled water (1mL). The organic solvent was evaporated under vacuum. The resulting orange solid was purified by dialysis for 3 days using dialysis bag of molecular cut off of 3.5KDa. Lyophilization gave fluorescent orange PIMA-GA-FITC polymer. Double distilled water (1 ml) containing aquated DACH-platinum (0.0011 g) was added to PIMA-GA-FITC (0.004 g), and the solution was stirred at room temperature (25°C) for 48h. The PIMA-GA-FITC- DACH-platinum conjugate formed in solution was further purified by dialysis to remove unattached DACH-platinum with mass-average molecular mass cut-off limits of 1000 dalton. Lyophilization of the dialyzed solution resulted in orange colored FITC-labeled PIMA-GA-FITC-DACH-platinum conjugate that self assembled into nanoparticles.

Particle Size Measurement

Copper grids with carbon film, 300 mesh (Electron Microscopy Sciences) was briefly covered by applying a drop of 0.01% BSA for a few seconds before to let it dry. The sample was then deposited onto the grid and left until the complete drying. In a last step, a drop of 2% aqueous phosphotungstic acid (pH to 7.4) is applied onto the grid and is left still the complete drying. Transmission electron microscopy observations were performed on a JEOL JEM 200 CX microscope, achieving a lattice and a point to point resolution of 1.4 Å and 3.5 Å. The acceleration voltage was set to 120 kV. The size distribution of nanoparticles and zeta potential was additionally studied by dynamic light scattering (DLS), which was performed at 25°C on a DLS-system (Malvern Zetasizer- ZS90) equipped with a He Ne laser.

Release Kinetics Studies

Concentrated PIMA-GA- DACH-platinum conjugate (containing equivalent amounts of Pt) was re-suspended into 100 μL of double distilled water and transferred to a dialysis tube (MWCO: 1000 KDa, Spectrapor). The dialysis tube was put into a tube containing magnetic pallet and 2 mL solutions of different pH 8.5, 7.4 and 5.5. Different pH of the solutions was adjusted by mixing different ratio of 1N sodium hydroxide and 1N nitric acid in water. Cyclohexanediamine platinum release was studied by gently stirring the dialysis bag at 300 rpm using IKA stirrer at 25°C. 10 μL aliquots were taken from the solution outside of dialysis membrane bag at predetermined time intervals, and platinum content was analyzed by ICP-AAS.

In Vitro Cell Culture and Cell Proliferation Assay

4T1 breast cancer cells were cultured in RPMI, MDA-MB-231 and CP20 cells were cultured in DMEM, and SKOV-3 cells were cultured in McCoy’s 5a medium supplemented with 10% FBS, penicillin (50 unit/ml) and streptomycin (50 unit/ml). Trypsinized cells were washed twice with PBS and seeded into 96-well flat bottomed plates at a density of 4×103 cells in 100 μl of medium. The free drug or nanoparticle (normalized to equivalent amounts of Pt) was added in triplicates in each 96-well plate, and then incubated for 48 h in a 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37° C. The cells were washed and incubated with 100 μl phenol- red free medium (without FBS) containing 20 μl of the CellTiter 96 Aqueous One Solution reagents (Promega, WI, USA). After 2-h incubation in a 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37° C, the absorbance in each well was recorded at 490 nm using Epoch plate reader (Biotek instruments, Vermont, USA). The absorbance reflects the number of surviving cells. Blanks were subtracted from all data and results analyzed using GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad, San Diego, CA). Each experiment was independently repeated thrice, and data shown is mean ± SE.

Cellular Uptake Studies

4T1, CP20 and MDA-MB-231 cells were seeded on glass coverslips in 24-well plates, at a density of 50000 cells per well. When cells reached 70% confluency, they were treated with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated PIMA-GA-DACH-platinum nanoparticles for different durations (4 h, 6 h, 12 h, and 24 h). For co-localization studies, at indicated time points, the cells were washed with PBS and incubated with Lysotracker Red (Molecular Probes) at 37 °C for 30 min to allow internalization. The cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min at room temperature, washed twice with PBS and mounted on glass slides using Prolong Gold Antifade Reagent (Molecular Probes). Images were captured using a Nikon Eclipse TE2000 epifluorescence microscope equipped with filters for FITC and Rhodamine.

In Vivo 4T1 Breast Cancer Tumor Model

The 4T1 Breast cancer cells (3×105) were implanted subcutaneously in the flanks of 4-week-old BALB/c mice (weighing 20 g, Charles River Laboratories, MA). The drug therapy was started after the tumors attained volume of 50 mm3. The tumor therapy consisted of administration of free oxaliplatin or cyclohexanediamineplatinum (II) nanoparticle, with the doses normalized to equivalent amounts of Pt. The formulations were prepared and validated such that 100 μL of phosphate buffer saline contained 5 mg/kg and 15 mg/kg of DACH-Pt either as free oxaliplatin or nanoparticle (i.e. all animals received an equivalent dose of platinum (administered via tail vein injections). PBS (100 μL) administered by tail-vein injection was used as a control for drug treatment. The tumor volumes and body weights were monitored on a daily basis. The tumors were harvested immediately following sacrifice and stored in 10% formalin for further analysis. All animal procedures were approved by Harvard institutional IUCAC committee.

Histopathology and TUNEL assay

The tissues were fixed in 10% formalin and blocks were paraffin embedded, sectioned, and stained with H&E. Tumor and kidney paraffin sections were deparaffinized and stained with fluorescent terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) staining following the manufacturer’s protocol (In Situ Cell Death Detection Kit, TMR Red, Roche). Images were obtained using a Nikon Eclipse TE2000 fluorescence microscope equipped with red filter.

Statistical Analysis

Data were expressed as means ± S.E or SD. (minimum n=3). Statistical analysis was conducted using the GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad, San Diego, CA). The statistical differences between the groups studied were determined by ANOVA followed by Newman Keul’s Post Hoc test. p<0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSIONS

Despite the advances in the understanding of cancer biology, cytotoxic drugs that indiscriminately target any dividing cell are still widely used in cancer chemotherapy. This necessitates the development of novel strategies that can specifically target the cytotoxic agents to the tumor, thereby reduce systemic toxicity. While nanoparticles have been used as drug delivery platforms for chemotherapeutic agents and preferentially target the tumor, the emerging paradigm is the design of nanomedicines, where a single large molecule folds into a nanoparticle. In this study, we describe the rational engineering of a novel self-assembling nanoparticle formed following complexation between DACH-Pt and PIMA-GA co-polymer that exhibits increased antitumor potency with reduced systemic toxicity as compared with the parent oxaliplatin molecule.

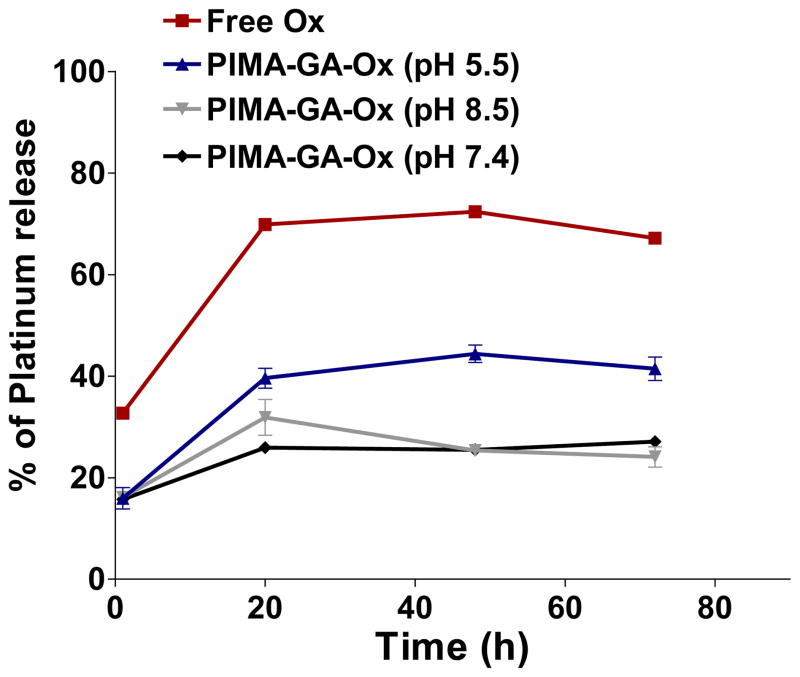

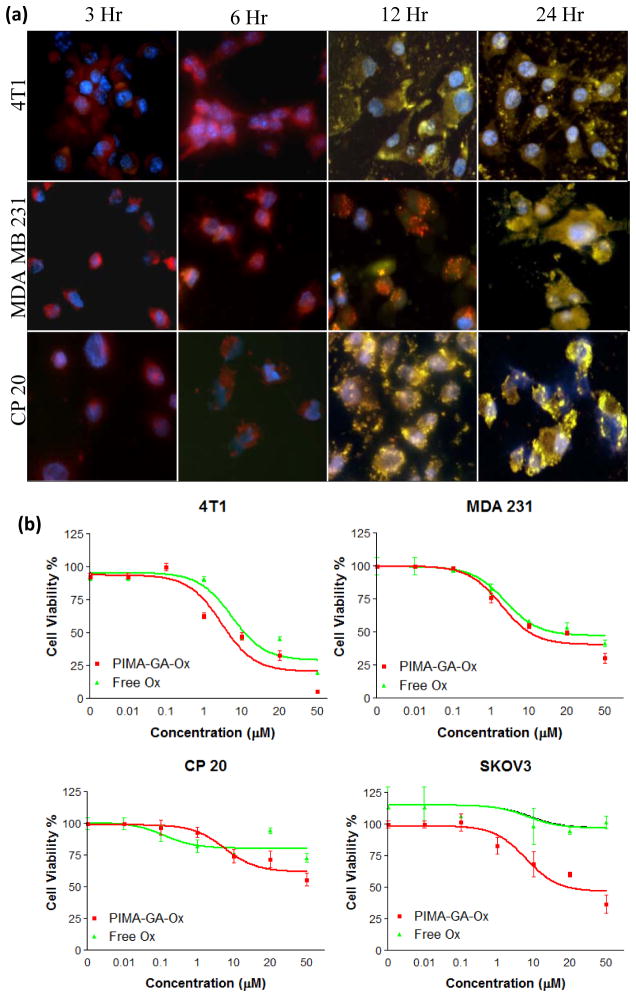

The platinum atom in oxaliplatin is complexed with a diaminocyclohexyl chelating ligand and an oxalate, the latter acting as the leaving group during bioactivation [7,27]. However, unlike cisplatin, the rate constant for aquation of oxaliplatin is reported to be 1.28 × 10−7s−1 compared with the aquation of cisplatin that has a rate constant of 8 × 10−5s−1 [28,29]. This is a critical difference as rate of aquation has been correlated with the rate at which Pt binds with DNA [4], and can explain the decrease in potency of oxaliplatin [30]. We rationalized that designing a novel hybrid polymer that acts as a more efficient leaving group instead of the oxalate can increase the efficacy, while the increase in the dimension of the molecule to the nanoscale could prevent renal clearance and avoid nephrotoxicity. We selected polyisobutylene maleic anhydride (PIMA) copolymer comprising of forty monomeric units, where each monomeric unit could chelate cyclohexanediamineplatinum (II) through dicarboxylato bonds after hydrolysis of anhydride ring. However dicarboxylato bonds with platinum are extremely stable with a rate constant for aquation equal to 7.2 × 10−7 s−1 as seen in carboplatin [4], and indeed the resulting product showed no increased efficacy (data not shown). To overcome this limitation, we next derivatized each monomeric unit of the PIMA polymer with glucosamine (GA) to create a hybrid PIMA-GA co-polymer (Fig.1b), which complexes with the Pt of cyclohexanediamineplatinum(II) through a less stable monocarboxylato and a O→Pt coordinate bond (Fig.1b). The rationale for selecting glucosamine was to increase the hydrophilicity of the resulting macromolecule, which contributes to increased circulation time of nanoparticles [15]. Additionally, glucosamine is a biocompatible molecule [31]. Interestingly, transmission electron microscopy revealed that at a ratio of 10 molecules of cyclohexanediamineplatinum(II) per polymer the complex self-assembled into a nanoparticle (referred to as PIMA-GA-DACH-platinum nanoparticle in rest of the text), predominantly in the size range of 80–250 nm as measured by dynamic laser light scattering (Fig.1c,d). While the loading at this Pt to polymer ratio is theoretically expected to be 222 μg of DACH-platinum per mg of polymer, the achievable loading was calculated to be 132.5 ± 33.23 (SD) μg/mg, resulting in a high loading efficiency of 59.64 ± 15.04 (SD)%. This is significantly higher than that reported in previous nanoformulations, suggesting complexation resulting in self-assembly is a superior approach towards nanoformulations rather than simple encapsulation strategies. Furthermore, the zeta potential was measured as -14mV indicating that the sample should be less susceptible to aggregation (Fig.1e). Additionally, as shown in Fig.2, the release of active cyclohexanediamine platinum (II) molecule from the polymer complex was found to be temporally sustained and pH-dependent, with faster release observed at an acidic pH as compared with a reference alkaline pH of 8.5 or at the physiological pH (7.4) as measured using inductive-coupled plasma atomic absorption spectrometry (Fig.2). This attains significance in the context of acidic pH that prevails in the tumor microenvironment that can contribute to intratumoral site-specific release of the active DACH-platinum. The elevated concentrations of free oxaliplatin in the release kinetics experiment was due to the fact that the free drug (in both parent and aquated forms) could leak out freely of the dialysis chamber, indicating that the DACH-Pt needs to dissociate (i.e. undergo aquation) from the polymer before it can leak out of the dialysis membrane. Furthermore, our studies using fluorescently-tagged polymer revealed co-localization of the fluorescence signals from the endolysomes and the nanoparticles (Fig.3a) demonstrating that the PIMA-GA-DACH-platinum nanoparticle are internalized by murine 4T1 cells, human breast cancer MDA-MB-231 cells as well as the human hepatocellular carcinoma CP20 cells that exhibits mutated platinum transporter. Localization in the endolysosome compartment was evident over a 24 hour period, where the pH is acidic (~5.5)[32]. This suggests that the internalization of the nanoparticle in the tumor cells would trigger the release of the activated platinum. This can offer a significant advantage over the liposomal formulations of platinum-based cytotoxics that failed to exhibit efficacy in the clinics due to limited drug release.

Fig 2. Release kinetics profile of aquated DACH-Pt from the nanoparticles with time under different pH conditions.

Free oxaliplatin or PIMA-GA-DACH-platinum conjugates (containing equivalent amounts of Pt) were dialyzed at an acidic pH (5.5) mimicking the endosomal fraction as compared with a reference alkaline pH of 8.5 or at the physiological pH (7.4). The release of active cyclohexanediamine platinum (II) molecule from the polymer complex was found to be temporally sustained and pH-dependent, with faster release observed in acidic conditions as measured using inductive-coupled plasma atomic absorption spectrometry.

Fig 3. Cellular uptake and cytotoxity assay.

(a) Murine breast cancer cells 4T1, human hepatocellular carcinoma cells CP20, and human metastatic breast cancer MDA-MB-231 cells, were treated with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated PIMA-GA-DACH-platinum nanoparticles for different durations (4 h, 6 h, 12 h, and 24 h). The cells were labeled with lysotracker red at different time-points following incubation with the nanoparticles. The merge images show co-labeling, indicating that the nanoparticles are internalized into the endolysosomes over time. (b) Graphs show the concentration-effect of different treatments on cellular viability as measured using MTS assay. Breast cancer cells, 4T1 and MDA-MB-231, hepatocellular carcinoma CP20 cells, and ovarian cancer cells SKOV3, were used for this study. X-axis shows the equivalent concentrations of platinum. Where blank polymeric controls were used, dose of polymer used was equivalent to that used to deliver that specific dose of DACH-platinum in the complexed form. PIMA-GA-Ox refers to the isomer [PIMA-GA-DACH-platinum].

We next tested the in vitro efficacy of the PIMA-GA-DACH-platinum nanoparticle in a mouse 4T1 breast cancer cell line, a human MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cell line, a human cisplatin-resistant hepatocellular carcinoma cell line (CP20), and a human ovarian SKOV3 cell line. The viability of the cells was quantified using a tetrazolium assay following 48 hours of incubation with the free drug or the PIMA-GA-DACH-platinum nanoparticle. As shown in Fig.3b, PIMA-GA-DACH-platinum nanoparticle exhibited increased potency than free oxaliplatin, with an IC50 value equivalent to 2.49 ± 0.01 μM against 4T1 cells as compared with 5.48 ± 0.01 μM. While free oxaliplatin exhibited no efficacy against SKOV3 cells, the IC50 value in the case of PIMA-GA-DACH-platinum nanoparticle was calculated to be 20.27 ± 0.2 μM and respectively. Similarly, at the highest concentrations used, PIMA-GA-DACH-platinum nanoparticle resulted in significantly higher cell kill in the case of CP20 cells as compared with the free drug, which could be justified by internalization of the nanoparticles via endocytosis (Fig.3a) bypassing the mutated Pt transporter in these cells. The MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells were equally susceptibility oxaliplatin and PIMA-GA-DACH-platinum nanoparticle, with IC50= 0.67 ± 0.14 μM (Fig.2b). The polymer alone had no effect on the viability of the cells. When viewed in the light of the release kinetics results, it is clear that within this time frame only about 50% of the active drug is released from the nanoparticle, indicating increased efficacy of the cyclohexanediamineplatinum(II) molecule when complexed with the polymer in the monocarboxylato and O→Pt coordinate conformation as compared with oxaliplatin.

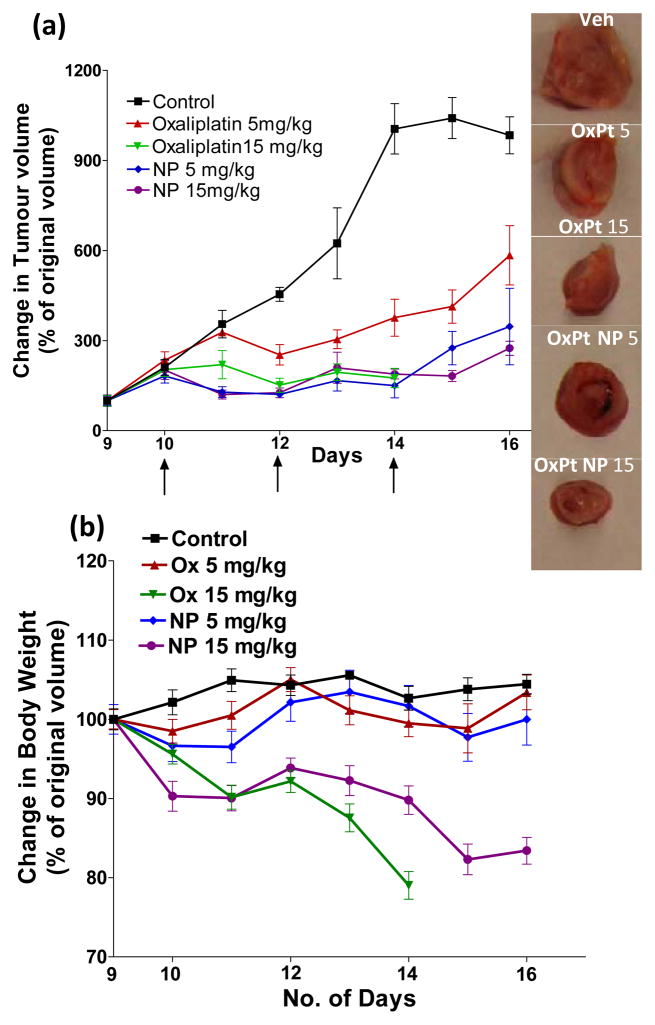

To validate the therapeutic efficacy of the nanoparticle-based treatment, we randomly sorted mice bearing established 4T1 tumors into five treatment groups, and treated each group with (i) phosphate buffer saline (PBS) control, (ii and iii) oxaliplatin (5mg/kg and 15 mg/kg), (iv-v) PIMA-GA-DACH-platinum nanoparticle (5mg and 15 mg/kg). The animals display palpable tumor by Day 9 post-implantation, which is when dosing was started and administered every alternate day for a total of three doses. The mice injected with PBS formed large tumors by day 16, and consequently, were euthanized. The animals in the other groups were also sacrificed at the same time point to evaluate the effect of the treatments on tumor pathology. As shown in Fig.4, treatment with free oxaliplatin resulted in tumor growth inhibition in a dose-dependent manner as compared with PBS control group. However, all the animals in the group that were dosed with oxaliplatin (15mg/kg) died by day 14, suggesting that this dose exceeded the maximum tolerated dose. Interestingly, at the same dose level, the group that received PIMA-GA-DACH-platinum nanoparticle had no mortality despite a loss of body weight, although the tumor inhibition was similar. Furthermore, the tumor inhibition by PIMA-GA-DACH-platinum nanoparticle (5mg/kg) was significantly greater than the inhibition exerted by the equivalent dose of free oxaliplatin, indicating that the nanoparticle increased the antitumor efficacy with reduction in toxicity. Additionally, the sustained release of activated platinum moiety from the nanoparticle could also contribute to a ‘metronomic’ effect. In recent studies, low dose cisplatin has been shown to exert a metronomic effect in hepatocellular carcinoma and human transitional cell carcinoma models, exhibiting increased apoptosis and inhibiting both tumor growth and angiogenesis [33].

Fig 4. PIMA-GA-DACH-platinum nanoparticle exerts superior anti-tumor effect with reduced systemic toxicity compared to free oxaliplatin in a 4T1 breast cancer model.

(a) Graphs show the effect of treatments on (i) tumor volume and (ii) body weight over the treatment period. The formulations were prepared and validated such that 100 μL of phosphate buffer saline contained 5 mg/kg and 15 mg/kg of DACH-Pt either as free oxaliplatin or nanoparticle (i.e. all animals received an equivalent dose of platinum (administered via tail vein injections). The animals were dosed i.v. on Day 9, 11 and 13. Data shown are mean ± SE, n=4–8. (b) Images of representative tumors from different treatment groups.

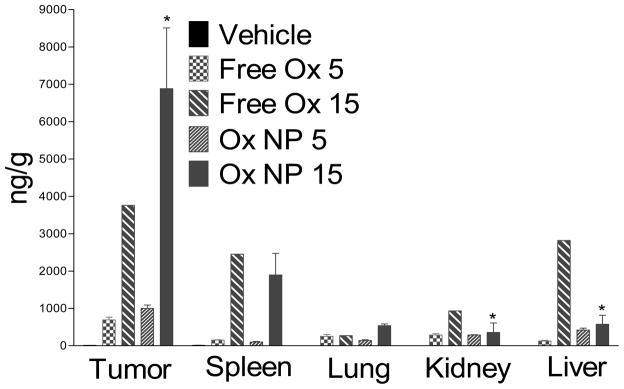

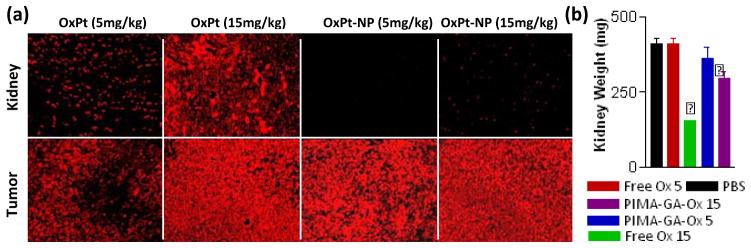

To dissect the mechanism underlying increased efficacy and reduced toxicity of the PIMA-GA-DACH-platinum nanoparticle as opposed to free oxaliplatin, we used ICP-atomic absorption spectroscopy to quantify the biodistribution of platinum in different tissues including in the tumor following necropsy. As shown in Fig.5, the concentration of platinum in the tumor following nanoparticle administration was significantly higher than achieved following administration of free oxaliplatin. In contrast, the concentrations achieved in the kidney were the reverse, where free drug resulted in greater platinum build-up as opposed to the PIMA-GA-DACH-platinum nanoparticle. This selective uptake into the tumor could arise from the increased circulation residence time as a result of the increase of hydrophilicity of the nanoparticle that could be contributed by glucosamine modification. Indeed, nanoparticles in the sub 200 nm sizes have been reported to preferentially home into the tumors, while larger nanoparticles tend to be sequestered by the reticuloendothelial system [15]. On the other hand, recent studies have revealed that nanoparticles of size greater than 5.5 nm are not cleared by the kidney [34], although polymeric nanoparticles can accumulate in kidney mesangium, with the maximal accumulation reached at 80 nm [35]. This indicates the size range of the nanoparticles obtained in this study is optimally designed to minimize kidney accumulation and maximize tumor targeting. Consistently, TUNEL-staining the tumor sections revealed a dose-dependent induction of apoptosis following treatment with free oxaliplatin, with a significantly greater effect seen with both doses of PIMA-GA-DACH-platinum nanoparticle (Fig.2c). Interestingly, while the free drug induced significant apoptosis in the kidney even at the lower concentration, this was not observed in the case of PIMA-GA-DACH-platinum nanoparticle even at the highest dose (Fig.5a). Indeed, this correlated well with the observed weights of the kidney, which revealed significant kidney toxicity at the highest dose of free drug (Fig. 5b). Additionally, we observed minimal sequestering within the RES organs, indicating that the hydrophilicity conferred by glucosamine was indeed conferring a stealth effect. However, we do anticipate that the clearance of the nanoparticles over time will occur via the hepatic clearance and through the gut. A detailed pharmacokinetic study, including blood concentration levels will be published elsewhere.

Fig 5. Biodistribution of PIMA-GA-DACH-platinum nanoparticles in vivo.

Graph shows the levels of Pt in the organs after 4T1 tumor-bearing animals were dosed thrice every alternate day starting Day 9 over duration of the experiment. The formulations were prepared and validated such that 100 μL of phosphate buffer saline contained 5 mg/kg and 15 mg/kg of DACH-Pt either as free oxaliplatin or nanoparticle (i.e. all animals received an equivalent dose of platinum (administered via tail vein injections). The Pt concentration was measured using ICP-MS, and normalized to the total weight of the tissue. Data shown are mean ± SEM (n=3–5), *P<0.05 vs free oxaliplatin-treated group (at equivalent platinum dose).

Nanoparticles are increasingly being used in cancer chemotherapy, including in delivering oxaliplatin. However, these studies harnessed stable chelation environments such as dicarboxylato or amidomalonato linkages between the platinum and the leaving group [26,36]. Here we demonstrate that the monocarboxylato and O→Pt coordinate bond confers a more optimal environment for complexation with Pt, which increases the potency of the DACH-platinum nanoparticle as compared with oxaliplatin. The increase in the molecular dimensions from an Angstrom to the nanoscale confers preferential homing and intratumoral build-up of the drug with potential to bypass the kidney, thereby overcome dose-limiting nephrotoxicity associated with platinum chemotherapeutics. With the widespread use of platinum chemotherapy in the clinics, we anticipate that a nanoscale platinum drug that exhibits increased efficacy with reduced toxicity can have a significant impact in cancer chemotherapy.

Fig 6. PIMA-GA-DACH-platinum nanoparticle exhibits lesser renal toxicity but increased tumor apoptosis compared with free oxaliplatin in vivo.

The formulations were prepared and validated such that 100 μL of phosphate buffer saline contained 5 mg/kg and 15 mg/kg of DACH-Pt either as free oxaliplatin or nanoparticle (i.e. all animals received an equivalent dose of platinum (administered via tail vein injections). Representative epifluorescence images of kidney and tumor sections following TUNEL staining for apoptosis. (d) Graphs show the effect of treatment on the weight of kidney as a marker for nephrotoxicity Data shown are mean ± SEM [n=4–6]. *P<0.05 vs free oxaliplatin-treated group (at equivalent platinum dose).

Acknowledgments

This work is funded by a Department of Defense BCRP Era of Hope Scholar Award (W81XWH-07-1-0482) and a BCRP Innovator Collaborative Award, and a NIH RO1 (1R01CA135242-01A2) to Shiladitya Sengupta. Abhimanyu Paraskar is supported by a DOD BCRP postdoctoral fellowship award (W81XWH-09-1-0728).

References

- 1.Kelland L. The resurgence of platinum-based cancer chemotherapy. Nature Rev Cancer. 2007;7:573–584. doi: 10.1038/nrc2167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leong CO, et al. The p63/p73 network mediates chemosensitivity to cisplatin in a biologically defined subset of primary breast cancers. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:1370–80. doi: 10.1172/JCI30866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Madias NE, Harrington JT. Platinum nephrotoxicity. Am J Med. 1978;65:307–14. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(78)90825-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Knox RJ, Friedlos F, Lydall DA, Roberts JJ. Mechanism of cytotoxicity of anticancer platinum drugs: evidence that cis-diamminedichloroplatinum(II) and cis-diammine-(1,1-cyclobutanedicarboxylato) platinum(II) differ only in the kinetics of their interaction with DNA. Cancer Res. 1986;46:1972–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kasparová D, Vrána O, Kleinwächter V, Brabec V. The effect of platinum derivatives on interfacial properties of DNA. Biophys Chem. 1987;28:191–7. doi: 10.1016/0301-4622(87)80089-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rixe O, Ortuzar W, Alvarez M, Parker R, Reed E, Paull K, Fojo T. Oxaliplatin, tetraplatin, cisplatin, and carboplatin: spectrum of activity in drug-resistant cell lines and in the cell lines of the National Cancer Institute's Anticancer Drug Screen panel. Biochem Pharmacol. 1996;52:1855–65. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(97)81490-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Raymond E, Chaney SG, Taamma A, Cvitkovic E. Oxaliplatin: a review of preclinical and clinical studies. Ann Oncol. 1998;9:1053–71. doi: 10.1023/a:1008213732429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spingler B, Whittington DA, Lippard SJ. 2.4 A crystal structure of an oxaliplatin 1,2-d(GpG) intrastrand cross-link in a DNA dodecamer duplex. Inorg Chem. 2001;40:5596–602. doi: 10.1021/ic010790t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Woynarowski JM, Chapman WG, Napier C, Herzig MC, Juniewicz P. Sequence- and region-specificity of oxaliplatin adducts in naked and cellular DNA. Mol Pharmacol. 1998;54:770–7. doi: 10.1124/mol.54.5.770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Woynarowski JM, Faivre S, Herzig MC, Arnett B, Chapman WG, Trevino AV, Raymond E, Chaney SG, Vaisman A, Varchenko M, Juniewicz PE. Oxaliplatin-induced damage of cellular DNA. Mol Pharmacol. 2000;58(5):920–7. doi: 10.1124/mol.58.5.920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Paraskar AS, Soni S, Chin KT, Chaudhuri P, Muto KW, Berkowitz J, Handlogten MW, Alves NJ, Bilgicer B, Dinulescu DM, Mashelkar RA, Sengupta S. Harnessing structure-activity relationship to engineer a cisplatin nanoparticle for enhanced antitumor efficacy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:12435–40. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1007026107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Basu S, Harfouche R, Soni S, Chimote G, Mashelkar RA, Sengupta S. Nanoparticle-mediated targeting of MAPK signaling predisposes tumor to chemotherapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:7957–61. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902857106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sengupta S, Tyagi P, Velpandian T, Gupta YK, Gupta SK. Etoposide encapsulated in positively charged liposomes: pharmacokinetic studies in mice and formulation stability studies. Pharmacol Res. 2000;42:459–64. doi: 10.1006/phrs.2000.0714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ferrari M. Cancer nanotechnology: opportunities and challenges. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:161–71. doi: 10.1038/nrc1566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moghimi SM, et al. Long-circulating and target-specific nanoparticles: theory to practice. Pharmacol Rev. 2001;53:283–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yuan F, Dellian M, Fukumura D, Leunig M, Berk DA, Torchilin VP, Jain RK. Vascular permeability in a human tumor xenograft: molecular size dependence and cutoff size. Cancer Res. 1995;55:3752–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Avgoustakis K, et al. PLGA-mPEG nanoparticles of cisplatin: In vitro nanoparticle degradation, in vitro drug release and in vivo drug residence in blood properties. J Controlled Release. 2002;79:123–135. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(01)00530-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fujiyama J, et al. Cisplatin incorporated in microspheres: Development and fundamental studies for its clinical application. J Controlled Release. 2003;89:397–408. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(03)00131-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boulikas T, Stathopoulos GP, Volakakis N, Vougiouka M. Systemic Lipoplatin infusion results in preferential tumor uptake in human studies. Anticancer Res. 2005;25:3031–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seetharamu N, Kim E, Hochster H, Martin F, Muggia F. Phase II study of liposomal cisplatin (SPI-77) in platinum-sensitive recurrences of ovarian cancer. Anticancer Res. 2010;30:541–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haxton KJ, Burt HM. Polymeric drug delivery of platinum-based anticancer agents. J Pharm Sci. 2009;98:2299–316. doi: 10.1002/jps.21611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stathopoulos GP, Boulikas T, Kourvetaris A, Stathopoulos J. Liposomal oxaliplatin in the treatment of advanced cancer: a phase I study. Anticancer Res. 2006;26:1489–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang C, Liu HZ, Lu WD, Fu ZX. PEG-liposomal oxaliplatin potentialization of antitumor efficiency in a nude mouse tumor-xenograft model of colorectal carcinoma. Oncol Rep. 2011;25:1621–8. doi: 10.3892/or.2011.1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gianasi E, Wasil M, Evagorou EG, Keddle A, Wilson G, Duncan R. HPMA copolymer platinates as novel antitumour agents: in vitro properties, pharmacokinetics and antitumour activity in vivo. Eur J Cancer. 1999;35:994–1002. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(99)00030-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rice JR, Gerberich JL, Nowotnik DP, Howell SB. Preclinical efficacy and pharmacokinetics of AP5346, a novel diaminocyclohexane-platinum tumor-targeting drug delivery system. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:2248–54. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brown SD, Nativo P, Smith JA, Stirling D, Edwards PR, Venugopal B, Flint DJ, Plumb JA, Graham D, Wheate NJ. Gold nanoparticles for the improved anticancer drug delivery of the active component of oxaliplatin. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:4678–84. doi: 10.1021/ja908117a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Raymond E, Faivre S, Woynarowski JM, Chaney SG. Oxaliplatin: mechanism of action and antineoplastic activity. Semin Oncol. 1998;25:4–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Davies MS, Berners-Price SJ, Hambley TW. Slowing of cisplatin aquation in the presence of DNA but not in the presence of phosphate: improved understanding of sequence selectivity and the roles of monoaquated and diaquated species in the binding of cisplatin to DNA. Inorg Chem. 2000;39:5603–13. doi: 10.1021/ic000847w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gao WG, Pu SP, Liu WP, Liu ZD, Yang YK. The aquation of oxaliplatin and the effect of acid. Yao Xue Xue Bao. 2003;38:223–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Powles T, Perry J, Shamash J. A Comparison of the Platinum Analogues in Bladder Cancer Cell Lines. Urol Int. 2007;79:67–72. doi: 10.1159/000102917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee KY, Ha WS, Park WH. Blood compatibility and biodegradability of partially N-acylated chitosan derivatives. Biomaterials. 1995;16:1211–6. doi: 10.1016/0142-9612(95)98126-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Song CW. Cancer Drug Discovery and Development: Cancer Drug Resistance, ed B Teicher. Humana Press; Totowa, NJ: 2006. Influence of tumor pH on therapeutic response; pp. 21–42. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shen FZ, Wang J, Liang J, Mu K, Hou JY, Wang YT. Low-dose metronomic chemotherapy with cisplatin: can it suppress angiogenesis in H22 hepatocarcinoma cells? Int J Exp Pathol. 2010;91:10–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2613.2009.00684.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Choi HS, Liu W, Misra P, Tanaka E, Zimmer JP, Itty Ipe B, Bawendi MG, Frangioni JV. Renal clearance of quantum dots. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25:1165–70. doi: 10.1038/nbt1340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Choi CH, Zuckerman JE, Webster P, Davis ME. Targeting kidney mesangium by nanoparticles of defined size. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:6656–61. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1103573108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sood P, Thurmond KB, 2nd, Jacob JE, Waller LK, Silva GO, Stewart DR, Nowotnik DP. Synthesis and characterization of AP5346, a novel polymer-linked diaminocyclohexyl platinum chemotherapeutic agent. Bioconjug Chem. 2006;17:1270–9. doi: 10.1021/bc0600517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]