Summary

Transcription factor FoxO1 promotes hepatic glucose production. Genetic inhibition of FoxO1 function prevents diabetes in experimental animal models, providing impetus to identify pharmacological approaches to modulate its function. Altered Notch signaling is seen in tumorigenesis, and Notch antagonists are in clinical testing for cancer application. Here, we report that FoxO1 and Notch coordinately regulate hepatic glucose metabolism. Combined haploinsufficiency of FoxO1 and Notch1 markedly improves insulin sensitivity in diet-induced insulin resistance, as does liver-specific knockout of the Notch transcriptional effector, Rbp-Jk. Conversely, Notch1 gain-of-function promotes insulin resistance in a FoxO1-dependent manner and induces Glucose-6-phosphatase expression. Pharmacological blockade of Notch signaling with γ-secretase inhibitors improves insulin sensitivity following in vivo administration in lean and in obese, insulin-resistant mice. The data identify a heretofore unknown metabolic function of Notch, and suggest that Notch inhibition is beneficial to diabetes treatment, in part by helping to offset excessive FoxO1–driven hepatic glucose production.

Introduction

Type 2 diabetes is associated with obesity and insulin resistance1. The pathophysiology of the insulin–resistant state remains enigmatic, and currently available insulin sensitizers are only partially effective at improving glucose disposal in skeletal muscle and suppressing hepatic gluconeogenesis2. A more detailed knowledge of pathways that influence insulin resistance is necessary to identify new targets for the development of anti-diabetic drugs3.

Forkhead box-containing transcription factors of the FoxO subfamily are key effectors of insulin action in metabolic processes, including hepatic glucose production (HGP)4. Hepatic FoxO1 promotes transcription of glucose-6-phosphatase (G6pc) and phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (Pck1), the rate-limiting enzymes in hepatic glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis, respectively5. FoxO1 is phosphorylated by Akt, leading to its nuclear exclusion and degradation6. In insulin resistance, FoxO1 is constitutively active, leading to increased HGP and fasting hyperglycemia7. Despite the importance of FoxO1 in regulation of hepatic insulin sensitivity8, it remains a poor candidate as a drug target due to the lack of a ligand-binding domain and broad transcriptional signature.

Notch receptors mediate cell fate decisions via interactions among neighboring cells; complexity arises from the presence of four transmembrane receptors (Notch1-4), and five transmembrane ligands of the Jagged/Delta-like families9. Upon ligand-dependent activation, a series of cleavage events leads to release and nuclear entry of the Notch intracellular domain (NICD), binding and activation of transcription factor Rbp-Jk and downstream expression of Notch target genes of the Hairy enhancer of split (Hes) and Hes-related (Hey) family10. Mutations in the Notch pathway are etiologic in multiple developmental and neoplastic conditions11, such as Alagille syndrome, a human disorder characterized by cholestasis and vascular anomalies12,13. In mice, nullizygosity of Notch1, Jagged1 and Rbpj is embryonic lethal, underscoring the developmental requirement for Notch signaling9,14,15.

We have previously demonstrated that FoxO1 and Rbp-Jk directly interact, leading to corepressor clearance from and coactivator recruitment to promoters of Notch target genes, allowing differentiation of multiple cell types16. This observation provides a mechanistic foundation for the interaction between the PI 3-kinase/Akt/FoxO1 and Notch/Rbp-Jk pathways to integrate growth with differentiation. We hypothesized that a similar interaction between these pathways exists in differentiated tissue and modulates FoxO1 metabolic functions. We used loss-of-function mutations in the two pathways, as well as adenovirus-mediated gain-of-function and pharmacological inhibition to demonstrate that Notch can regulate HGP in a FoxO1-dependent manner.

Results

Foxo1 and Notch1 haploinsufficiency increase insulin sensitivity

To evaluate the physiologic relevance of Notch signaling in liver, we determined relative expression of the four Notch receptors. In wild-type (WT) mouse hepatocytes, Notch1 and Notch2 are predominantly expressed (data not shown). Notch1 activation, as reflected by cleavage at Val1744 and expression of canonical Notch targets, increased with fasting (Fig. 1a,b), in parallel with gluconeogenic genes (Supplementary Fig. 1a,b) and returned to baseline levels with refeeding. Both Notch1 and Notch2 were induced in db/db mouse liver and with high-fat diet (HFD), with increased Notch target expression (Supplementary Fig. 1c,d and data not shown). Notch1 activation during fasting and in insulin resistance parallels that of FoxO1. To investigate a functional relationship between these pathways, we generated mice with combined haploinsufficiency of the two genes (Foxo1+/−:Notch1+/−), which demonstrated reduced Notch1 and FoxO1 expression in all tissues (data not shown).

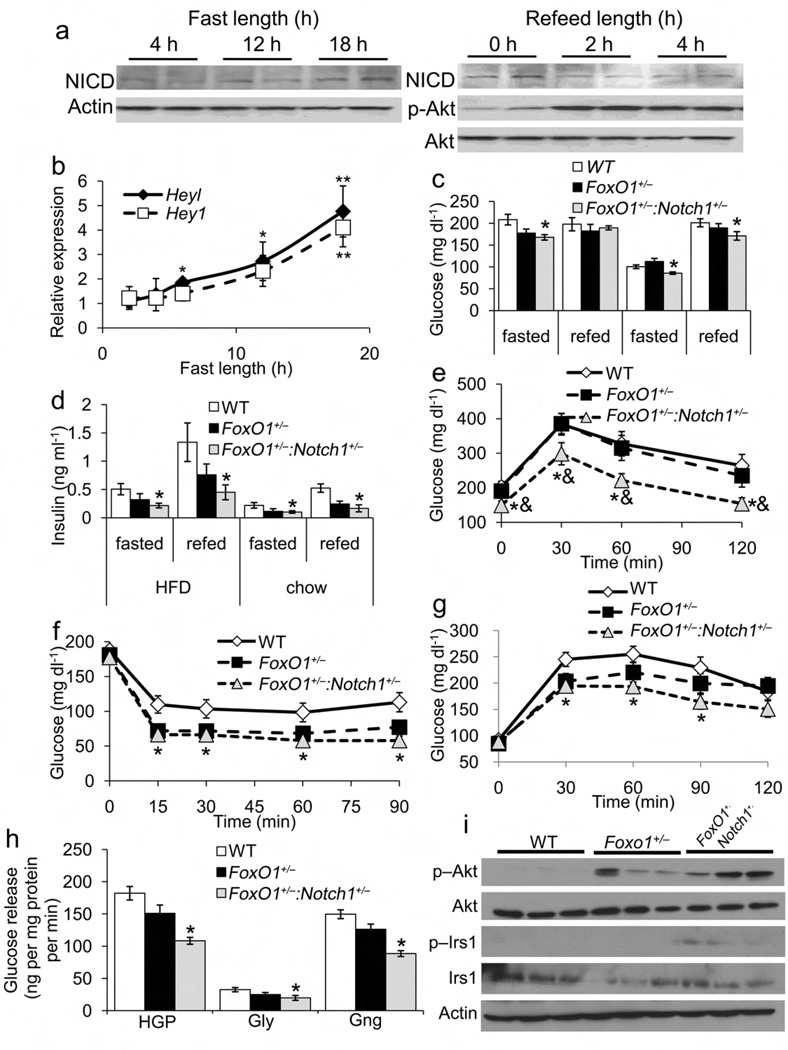

Figure 1.

Metabolic characterization of Foxo1+/− and Foxo1+/−:Notch1+/− mice. (a) Notch1 cleavage and (b) Notch target gene expression in livers from 8-wk-old male WT mice after increasing length of fast, or refeeding after 24hr fast. (c) Glucose and (d) insulin levels in mice fed either HFD or standard chow and fasted for 16 h, or fasted for 16 h, then refed for 2 h. (e) Intraperitoneal glucose tolerance tests (IPGTT) in HFD-fed mice following 16-h fast. (f) Insulin tolerance tests in HFD-fed mice following 4-h fast. (g) Pyruvate tolerance test in HFD-fed mice following 16-h fast. (h) Glucose production in primary hepatocytes from WT, FoxO1+/− and Foxo1+/−:Notch1+/− mice in the presence (HGP) or absence of pyruvate and lactate (glycogenolysis, Gly). The difference between these two values was assumed to reflect gluconeogenesis (Gng). (i) Western blots of insulin signaling proteins in livers from HFD-fed WT, FoxO1+/− and Foxo1+/−:Notch1+/− mice. All animals were 16-wk old. *P < 0.05 vs. WT, &P < 0.05 vs. Foxo1+/− (n = 7–8 each genotype).

Despite unchanged body mass index, body composition, food intake, and oxygen consumption (Supplementary Fig. 2a–d), Foxo1+/−:Notch1+/− mice showed decreased fasted and fed glucose and insulin levels on different diets, suggesting greater insulin sensitivity than WT or Foxo1+/− mice (Fig. 1c,d). Glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity increased in chow– (data not shown) and HFD-fed Foxo1+/−:Notch1+/− mice (Fig. 1e,f). Pyruvate tolerance tests demonstrated decreased conversion of pyruvate to glucose in Foxo1+/−:Notch1+/− mice, suggestive of decreased gluconeogenesis (Fig. 1g), confirmed by decreased glucose production in primary hepatocytes isolated from Foxo1+/−:Notch1+/− as compared to WT mice (Fig. 1h). Hepatic Akt1 and IRS1 phosphorylation was increased in Foxo1+/−:Notch1+/− mice, consistent with increased hepatic insulin sensitivity (Fig. 1i). For most parameters tested, Foxo1+/− mice demonstrated similar trends, but differences did not reach statistical significance. Notch1+/− mice did not differ significantly from WT mice in any parameter tested (data not shown).

We detected no difference in β-cell mass or glucose-stimulated insulin release between Foxo1+/−:Notch1+/− and control mice (data not shown), suggesting that metabolic changes are unrelated to β-cell function. We detected no change in serum glucagon, corticosterone or triglycerides (data not shown), but adiponectin levels were lower in Foxo1+/− and Foxo1+/−:Notch1+/− animals (Supplementary Table 1). Total body fat content was unchanged, but epididymal fat weight was increased in Foxo1+/− and Foxo1+/−:Notch1+/− animals.

Insulin sensitivity in clamped Foxo1+/−:Notch1+/− mice

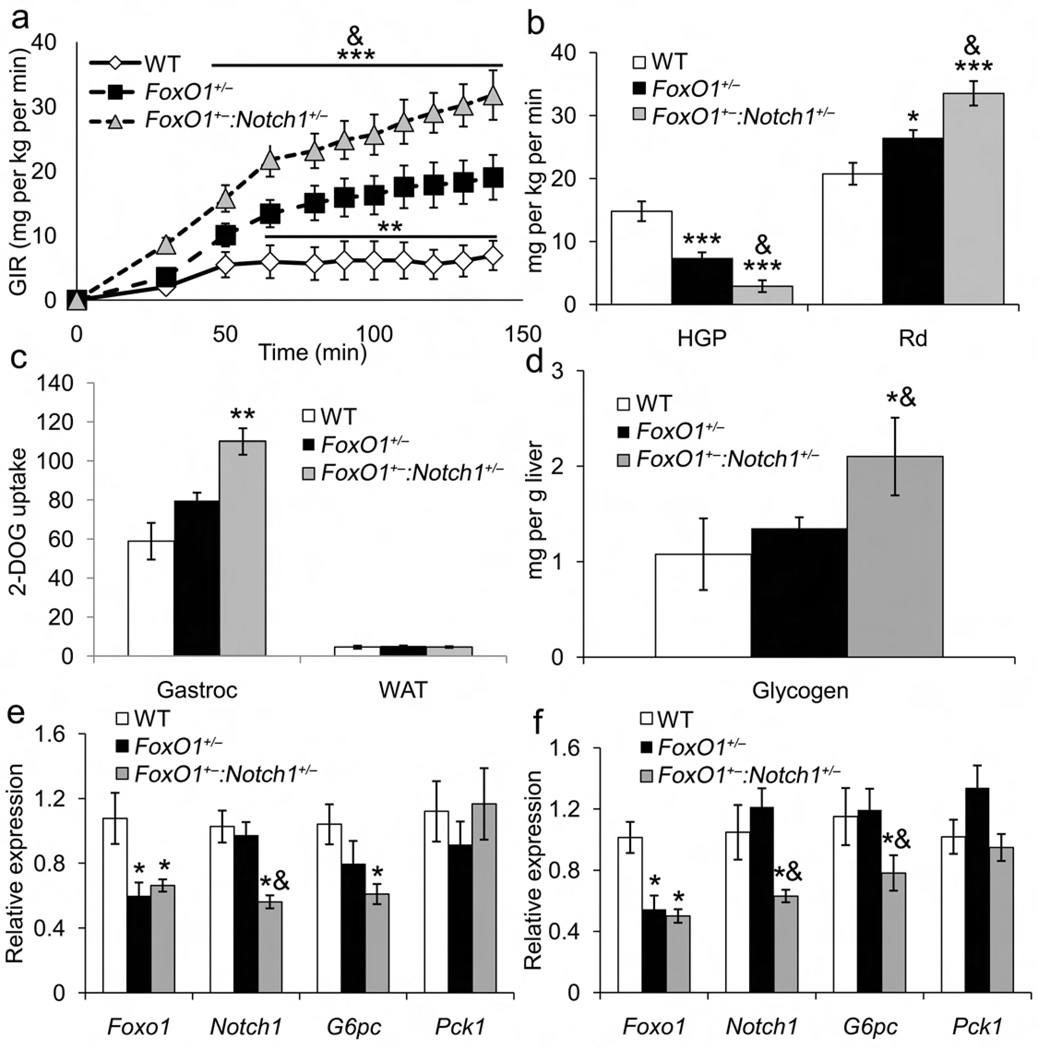

We next performed hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamps. Foxo1+/−:Notch1+/− mice required 1.6- and 4.5-fold greater glucose infusion rates than Foxo1+/− and WT mice, respectively, to maintain euglycemia (Fig. 2a). Likewise, HGP was inhibited, and glucose disposal stimulated, to a greater extent in Foxo1+/−:Notch1+/− mice than in Foxo1+/− mice, although both groups were more insulin-sensitive than WT littermates (Fig. 2b). Muscle 2-deoxyglucose uptake was higher in Foxo1+/−:Notch1+/− mice (Fig. 2c), as was glycogen synthesis (Supplementary Table 2), resulting in a twofold increase in hepatic glycogen compared to WT or Foxo1+/− mice (Fig. 2d).

Figure 2.

Hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamps and gene expression studies in Foxo1+/−:Notch1+/− mice. (a) Glucose infusion rate (GIR), (b) hepatic glucose production (HGP) and glucose disposal rate (Rd) from clamp studies in 12-wk-old, HFD-fed WT, Foxo1+/− and Foxo1+/−:Notch1+/− male mice. (c) 14C-2-deoxy-glucose (2-DOG) uptake during the final 5 min of the clamp. (d) Hepatic glycogen content in clamped livers. Gene expression in 16-wk-old, (e) chow-fed or (f) HFD-fed WT, Foxo1+/− and Foxo1+/−:Notch1+/− male mice sacrificed after a 16-h fast. All genes were normalized by 18s rRNA. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. WT; &P < 0.05 vs. Foxo1+/− (n = 7–8 each genotype).

Unlike HFD-fed mice, there was no detectable difference between chow-fed Foxo1+/− and Foxo1+/−:Notch1+/− mice, likely a consequence of the sensitivity of the clamp technique, as demonstrated by negative HGP in clamped conditions (Supplementary Table 3).

To identify mechanisms of reduced HGP in Foxo1+/−:Notch1+/− mice, we analyzed G6pc and Pck1 expression. In fasted chow- (Fig. 2e) and HFD-fed cohorts (Fig. 2f), G6pc levels were lower in Foxo1+/−:Notch1+/− than Foxo1+/− and WT mice, with correspondingly decreased protein levels (data not shown). Pck1 expression was unaffected.

Liver-specific Rbp-Jκ knockout partially prevents insulin resistance

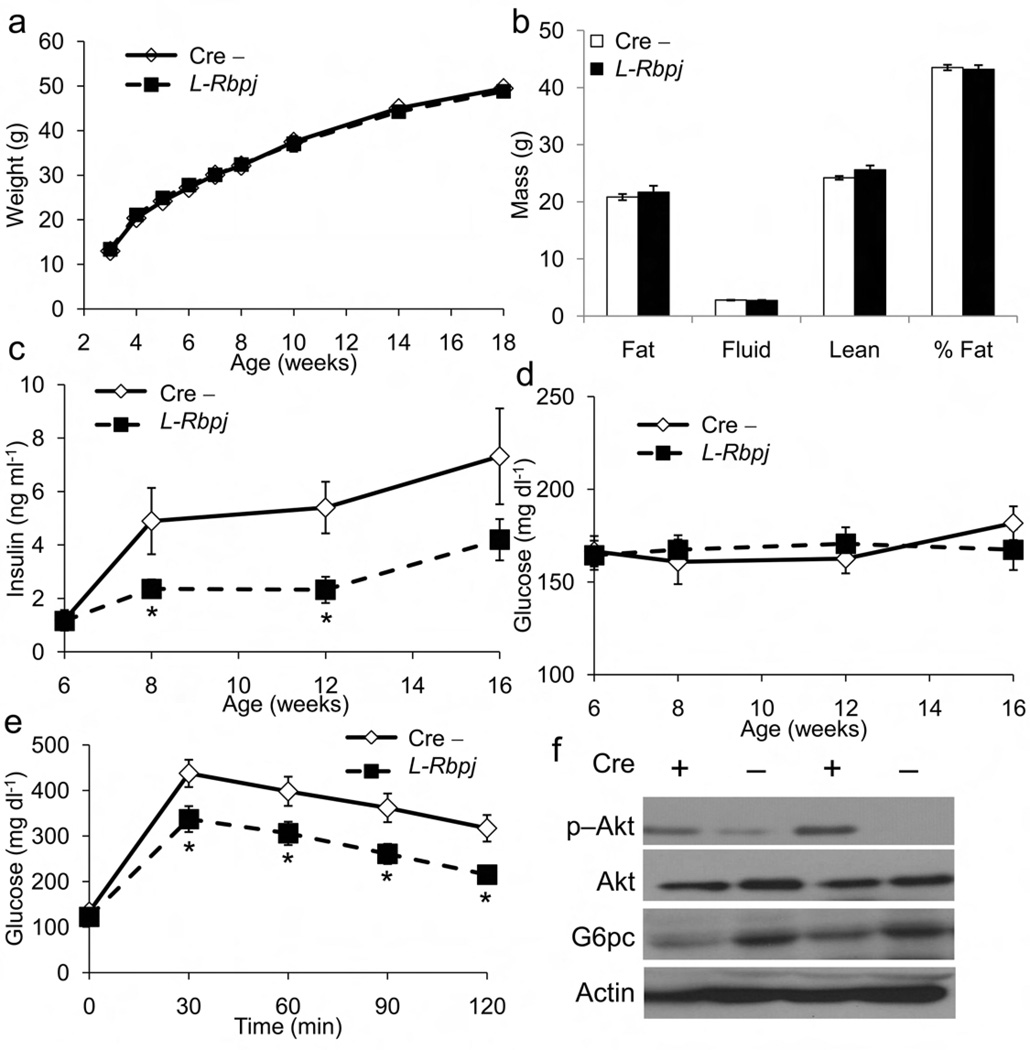

To test the hypothesis that hepatic Notch signaling affects insulin sensitivity, we generated mice lacking the Notch effector Rbp-Jκ or FoxO1 in liver, using Albumin-cre transgenic mice to delete Rbpj (L-Rbpj) or Foxo1 (L-Foxo1) “floxed” alleles, (Supplementary Fig. 3a–c)17. L-Rbpj mice showed no developmental, liver function test or histological abnormalities compared to controls (Supplementary Fig. 3d, e). With HFD, L-Rbpj mice showed normal weight gain and body composition (Fig. 3a,b), but lower insulin levels in the face of similar serum glucose (Fig. 3c,d), and improved glucose tolerance as compared to controls (Fig. 3e). Insulin tolerance tests were unaltered in L-Rbpj animals (data not shown). L-Rbpj livers showed increased Akt1 phosphorylation and lower fasted G6pc protein levels, indicative of increased hepatic insulin sensitivity (Fig. 3f). These data indicate that ablation of hepatic Notch signaling protects from diet-induced insulin resistance.

Figure 3.

Metabolic characteristics of L-Rbpj mice. (a) Growth curves, (b) body composition and ad libitum (c) insulin and (d) glucose levels of HFD-fed L-Rbpj mice and cre-negative controls (Cre−) measured every 2–4 wk. (e) IPGTT in 16-h fasted, HFD-fed Cre− and L-Rbpj mice. (f) Western blots for hepatic p−Akt, total Akt and G6pc from fasted, HFD-fed, 16-wk old Cre− and L-Rbpj (Cre +) mice. *P<0.05 vs. Cre− n = 8 each genotype).

Notch1 induces G6pc expression in a FoxO1-dependent manner

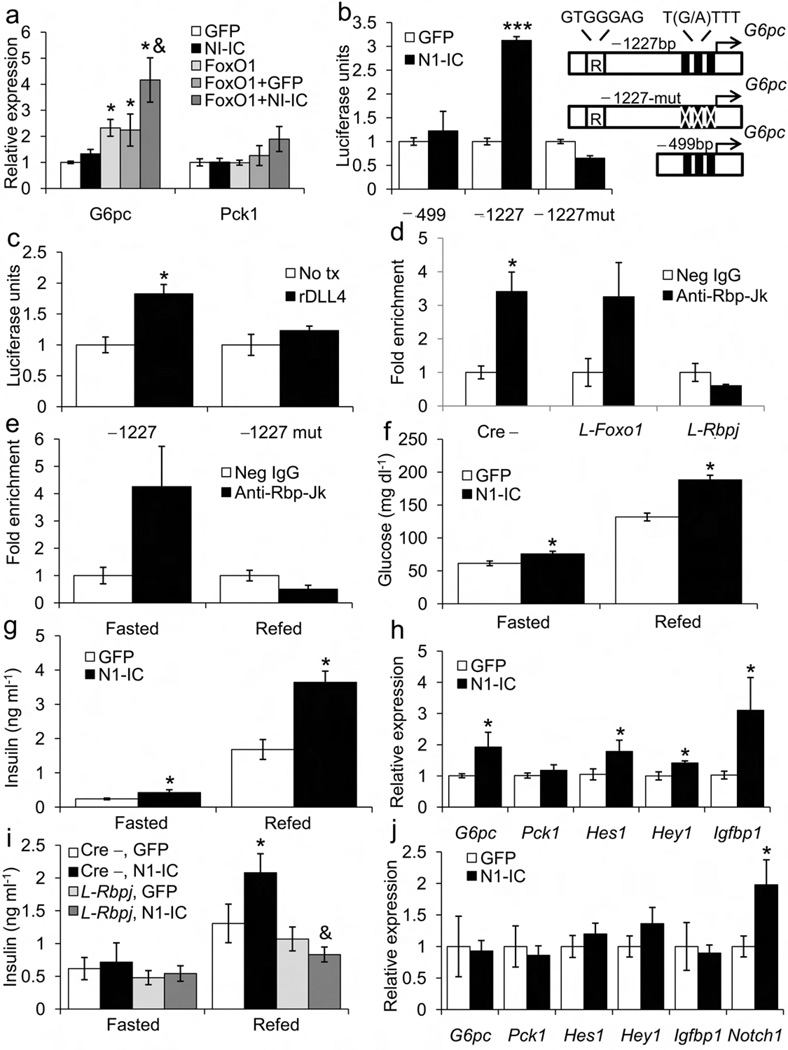

We transduced primary mouse hepatocytes with adenoviruses expressing N1-IC (constitutively active Notch1 mutant)18, FoxO1-ADA (constitutively active FoxO1 mutant)19 or GFP, and analyzed gluconeogenic gene expression. Consistent with previous studies, transduction with FoxO1-ADA increased G6pc expression19, whereas transduction with N1-IC did not. The combination of N1-IC and FoxO1-ADA synergistically induced G6pc as compared to FoxO1-ADA alone (Fig. 4a) and increased glucose release into culture medium (Supplementary Fig. 4a). We also saw synergistic induction of canonical Notch targets, but not traditional FoxO1 targets such as Pck1 or Igfbp1 (Fig. 4a, Supplemental Fig. 4b), a finding recapitulated in luciferase assays using promoters containing either Rbp-Jk (Supplemental Fig. 4c) or FoxO1 binding sites (Supplemental Fig. 4d). When co-transduced with FoxO1-ADA-DBD (DNA binding-deficient, constitutively nuclear mutant FoxO1)16, N1-IC was unable to induce G6pc (data not shown), indicating that Notch1 requires FoxO1 DNA binding to regulate G6pc.

Figure 4.

Notch1 regulation of G6Pc transcription in hepatocytes, and hepatic insulin sensitivity in vivo. (a) mRNA levels in primary hepatocytes from 12-wk-old WT male mice transduced with FoxO1-ADA (FoxO1), Notch1-IC (N1-IC) and/or GFP adenoviruses (MOI=5). (b) G6pc promoter luciferase reporter assays, following transduction with GFP or N1-IC, or (c) incubation with Delta-like ligand-4 (rDLL4). N1-IC or rDLL4 treatment-induced luciferase activity in constructs containing both Rbp-Jk (denoted with “R”) and FoxO1 binding sites (−1227bp), but not constructs lacking the sites (−499) or containing mutated FoxO1 sites (−1227-mut). Numbers refer to nucleotides upstream of transcription start site. (d) Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) at the G6pc promoter using anti-Rbp-Jk or control antibody in livers from fasted control (Cre−), L-Foxo1 and L-Rbpj mice. (e) G6pc ChIP assays from liver of WT mice fasted for 16 h or refed for 2 h following a 16-h fast. *P<0.05 vs. control IgG (n = 4). (f) Glucose and (g) insulin levels determined 7 days after N1-IC delivery in mice fasted for 16-h or refed for 2 h following a 16-h fast. (h) mRNA levels in livers of mice transduced with either N1-IC or GFP adenoviruses. (i) Insulin levels and (j) hepatic gene expression in 2-h refed L-Rbpj male mice and Cre− controls transduced with either N1-IC or GFP adenoviruses. *P < 0.05, *P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. GFP; &P < 0.05 vs. Cre− n = 5–8 each genotype).

To delineate the requirement of FoxO1 in Notch1-induced expression of G6pc, we performed luciferase assays using G6pc promoter reporter constructs. The G6pc promoter contains a conserved Rbp-Jκ binding element 1.1kb upstream of the transcriptional start site. N1-IC was able to induce luciferase activity only when we used constructs containing both Rbp-Jk as well as functional FoxO1 binding sites (Fig. 4b). We saw similar results using recombinant DLL4 that activates endogenous Notch signaling (Fig. 4c).

Rbp-Jκ binds to the G6pc promoter during fasting

Based on our luciferase data, we hypothesized that Rbp-Jκ directly binds to the G6pc promoter. Chromatin immunoprecipitation experiments showed a four-fold enrichment of Rbp-Jκ binding to a G6pc promoter sequence containing the putative Rbp-Jk element in control and L-Foxo1, but not L-Rbpj mice (Fig. 4d). No binding was seen in other regions of the G6pc promoter (data not shown). Consistent with increased hepatic Notch1 activation in the fasted state (Fig. 1a), this binding was seen only during fasting (Fig. 4e).

Gain of hepatic Notch1 function leads to insulin resistance

As adenovirus-mediated gene delivery leads to hepatocyte-predominant expression, we employed this technique to determine effects of N1-IC in liver20. Modest hepatic overexpression of Notch1 protein (Supplemental Fig. 4e) increased fasted and refed glucose and insulin levels (Fig. 4f,g), suggestive of insulin resistance. We noted increased G6pc expression in livers of mice transduced with N1-IC, as well as some (Igfbp1) but not all FoxO1 targets, (Fig. 4h), providing further evidence that Notch1 regulates hepatic gluconeogenesis by inducing G6pc.

If the N1-IC adenovirus acted in an Rbp-Jκ-dependent manner to promote HGP, one would predict that it would be unable to do so in L-Rbpj mice. Indeed, hepatic N1-IC transduction in L-Rbpj mice failed to increase plasma insulin (Fig. 4i) or expression of Notch targets and gluconeogenic genes (Fig. 4j).

γ-secretase inhibitors reduce HGP and improve glucose tolerance

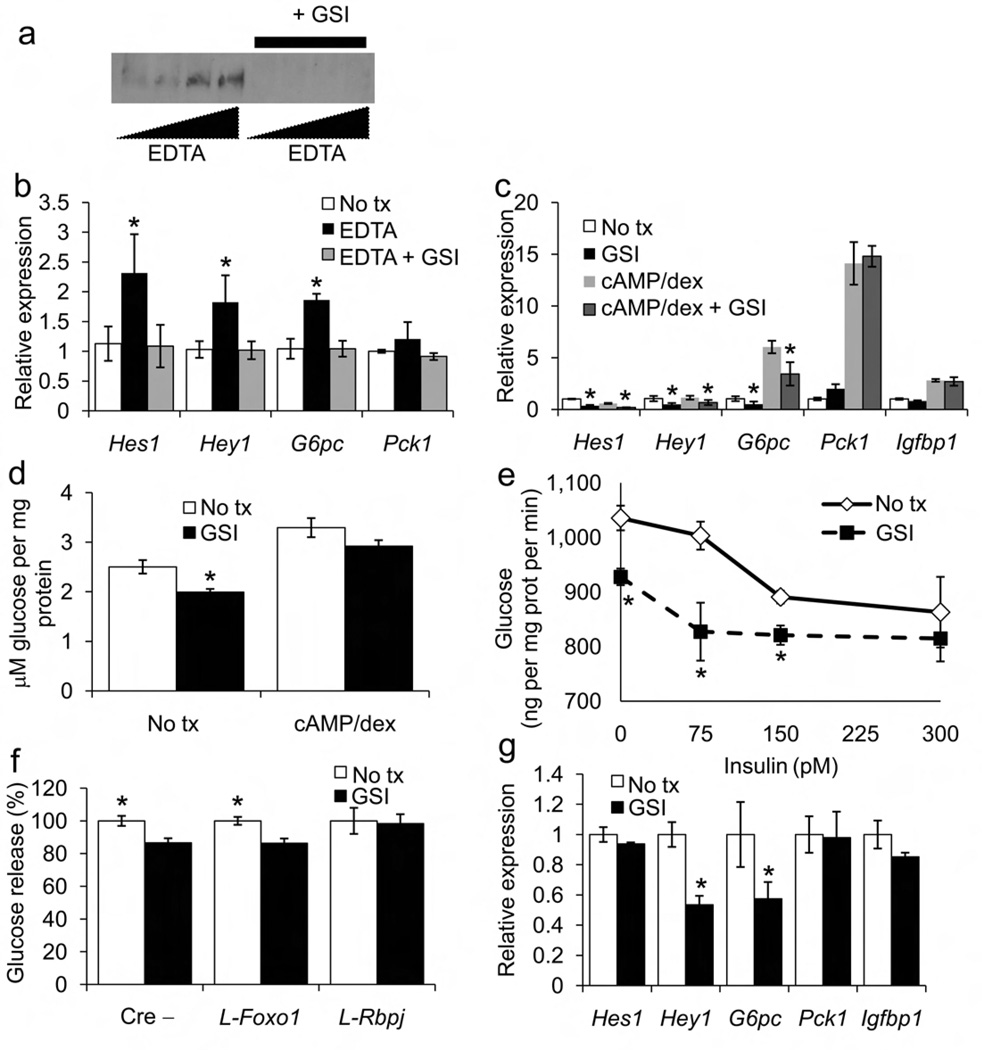

After ligand binding, Notch receptor heterodimers dissociate and undergo sequential cleavage by membrane-bound ADAM/TACE and γ-secretase complex9. Notch receptor dimerization is calcium-dependent and chelation with EDTA causes ligand-independent Notch activation 21. We activated endogenous Notch1 by treating primary hepatocytes with EDTA to generate NICD; this was prevented by co-treatment with Compound E, a cell-permeable γ-secretase inhibitor (GSI, Fig. 5a)22. EDTA treatment increased Notch target and G6pc expression in a GSI-inhibitable manner (Fig. 5b).

Figure 5.

Effects of GSI in primary hepatocytes. (a) Western blot analysis of Notch1 cleavage at Val1744 following incubation with increasing doses of EDTA in the presence or absence of GSI. (b) qPCR analysis of Notch targets in vehicle (No tx) or EDTA-treated hepatocytes in the presence or absence of GSI. (c) Gene expression and (d) glucose production in the absence (No tx) or presence of GSI. Hepatocytes were treated with cAMP and dexamethasone for 3 h to stimulate gluconeogenic gene expression and glucose output. (e) Dose-response curve for insulin inhibition of glucose production from primary hepatocytes incubated in the presence or absence of GSI. (f) Glucose production in the absence (No tx) or presence of GSI in primary hepatocytes from control (Cre−), FoxO1-deficient (L-Foxo1) and Rbp-Jκ-deficient mice (L-Rbpj). (g) GSI-dependent regulation of gene expression in hepatocytes transduced with FoxO1 shRNA adenovirus. *P<0.05 vs. No tx; &P<0.05 vs. cAMP/dexamethasone (n = 4). One experiment representative of 3 individual experiments is shown.

In the absence of EDTA, relying on physiologic Notch1 activation in serum-free conditions, GSI treatment inhibited Notch target and G6pc expression, decreased glucose production, and altered the dose-response curve of insulin to suppress glucose release (Fig. 5c–e). GSI blunted glucose output from hepatocytes derived from control and L-Foxo1, but not L-Rbpj mice, as well as from hepatocytes expressing FoxO1 shRNA, indicating that its effects are Notch-dependent, but FoxO1-independent (Fig. 5f,g)

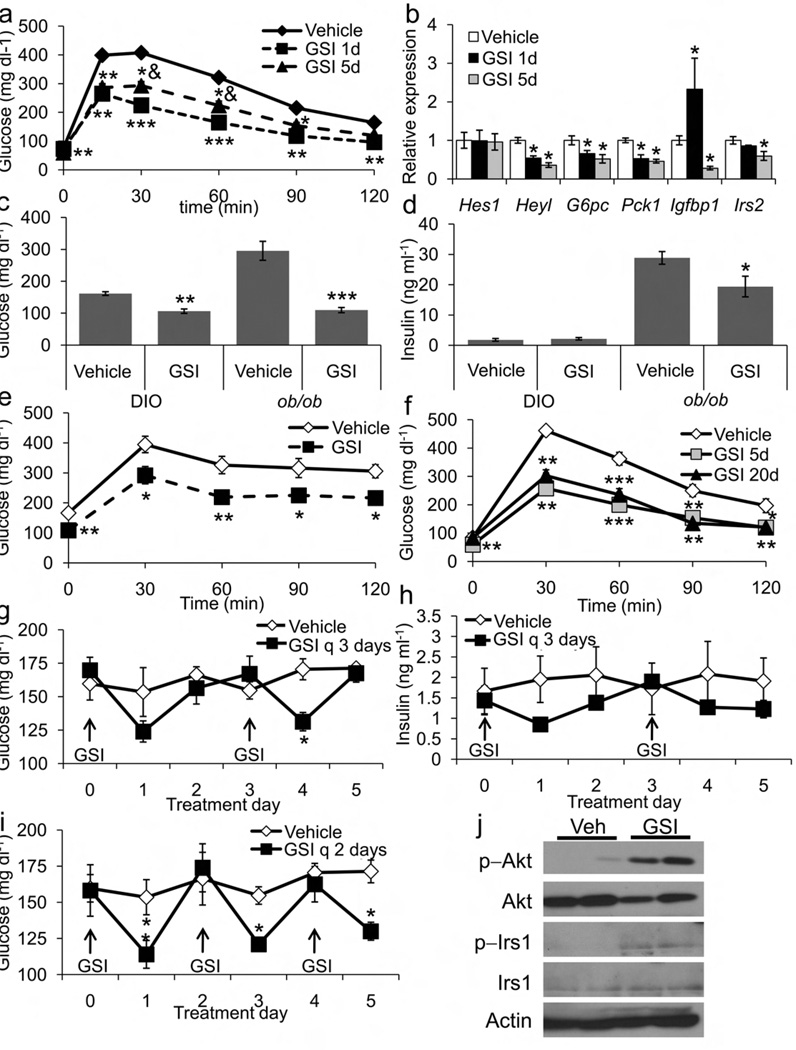

We next evaluated the in vivo effects of dibenzazepine (DBZ), a well characterized and bioavailable GSI23. Following a single dose of DBZ, WT mice demonstrated decreased fasting and refed plasma glucose levels; a 5-day course of DBZ yielded similar reductions in fasting glucose, without altered insulin levels or body weight (Supplementary Fig. 5a–c). Consistent with decreased HGP, DBZ-treated animals demonstrated markedly improved glucose tolerance (Fig. 6a, Supplementary Fig. 5d), accompanied by marked reduction in G6pc, Pck1 and other Notch- and FoxO1-specific targets (Fig. 6b). DBZ treatment resulted in transient hepatic glycogen accumulation (likely a consequence of reduced glycogenolysis), as well as mild intestinal metaplasia (Supplementary Fig. 5e, f)24. To test whether GSIs would be able to reverse the effects of chronic insulin resistance, we treated diet-induced obese (DIO) and leptin-deficient ob/ob mice with DBZ. Both cohorts showed markedly improved glucose levels (Fig. 6c) and glucose tolerance with GSI (Fig. 6e,f); ob/ob mice additionally demonstrated decreased insulin levels (Fig. 6d), suggestive of increased insulin sensitivity. Chronic, intermittent therapy with DBZ did not alter food intake, body weight or body composition (Supplementary Fig. 6a–c) but was similarly effective in improving glucose tolerance (Fig. 6g, Supplementary Fig. 6d), suggesting that GSI effects do not wane over time. Glucose and insulin measurements in the ad libitum fed state demonstrated that the hypoglycemic effect of GSI lasts ~24 h and is associated with lower insulin levels (Fig. 6g–i). Hepatic phosphorylation of Akt1 and IRS1 were increased, suggestive of increased hepatic insulin sensitivity with GSI treatment (Fig. 6j).

Figure 6.

Insulin-sensitizing effects of dibenzazepine (GSI) treatment. (a) IPGTT and (b) hepatic gene expression in 16-h fasted, chow-fed lean mice following a single dose of GSI (GSI 1d) or 5 consecutive days of GSI treatment (GSI 5d). (c) Ad libitum glucose and (d) insulin levels in diet-induced obese (DIO) and ob/ob mice following a 5-day course of either vehicle or GSI. (e) IPGTT in ob/ob mice following a 5-day course of vehicle or GSI. (f) IPGTT, (g) ad lib glucose and (h) insulin levels in DIO mice treated with either vehicle or GSI every third day, or (i) every second day (arrows). (j) Western blots of Akt and IRS1 phosphorylation in livers isolated after 5 days treatment with either vehicle or GSI. *P<0.05, *P<0.01, ***P<0.001 vs. vehicle, &P<0.05 vs. GSI 1d (n = 6 each group).

Discussion

While the beneficial effect of FoxO1 inhibition on glucose homeostasis is recognized7,25, the role of Notch signaling in this process, and the regulation of the hepatic Notch pathway by nutritional status are novel findings of this work. Combined activation of Notch1 and FoxO1 signaling with fasting and in insulin-resistance is consistent with the hypothesis that they co-regulate key metabolic pathways. Additionally, clamp studies point to a step-wise effect from WT to Foxo1+/− to Foxo1+/−:Notch1+/− mice in suppressing hepatic glucose production and promoting muscle glucose disposal. The contribution of extra-hepatic and cell-nonautonomous mechanisms to this complex phenotype remains to be determined, but the present data provide a strong mechanistic foundation to explore the therapeutic potential of targeting the Notch pathway in diabetes.

Multiple target genes likely account for the improved hepatic insulin sensitivity of Foxo1+/−:Notch1+/− mice, due to the pleiotropic functions of the insulin/FoxO1 and Notch1/Rbp-Jκ pathways9,26. A key finding of the present work is the repression of G6pc, a known transcriptional target of FoxO120, whose expression under both basal and hormone-stimulated conditions is reduced by >90% in hepatocytes from L-Foxo1 mice (unpublished observations, U.P. & D.A.), or following acute FoxO1 inhibition through shRNA28. Mechanistically, the most parsimonious explanation is that inhibition of G6pc in Foxo1+/−:Notch1+/− mice is secondary to reduced FoxO1 function. However, we show that G6pc is a direct Notch target, and that Rbp-Jκ binds to the G6pc promoter in a FoxO1-independent manner in the fasted state, consistent with a physiologic role of hepatic Notch to regulate HGP. Additional lines of evidence strengthen this conclusion; first, combined Notch1 and FoxO1 gain-of-function synergistically induced G6pc, without affecting other FoxO1 targets (Pck1 and Igfbp1) or FoxO1 phosphorylation. Second, adenovirus-mediated N1-IC overexpression in vivo induced G6pc in an Rbp-Jκ-dependent manner. Finally, Notch inhibition with GSIs consistently decreased G6pc, but not Pck1 and Igfbp1 expression. Specificity of transcriptional regulation of G6pc could result from coordinate binding of FoxO1 and Rbp-Jκ or cooperative interactions of the two proteins, as shown for Rbp-Jκ-dependent recruitment of FoxO1 to the Hes1 promoter16. Either model is consistent with our reporter assays that show a requirement for juxtaposed FoxO1 and Rbp-Jκ cis-acting DNA elements in the promoter for G6pc induction.

An unsettled question is whether FoxO1 requires Rbp-Jκ for maximal stimulation of G6pc transcription. GSI treatment of FoxO1-deficient primary hepatocytes curtailed G6pc expression and glucose production, indicating that the effects of this inhibitor are independent of FoxO1. Additionally, Rbp-Jκ ablation improved glucose tolerance in vivo and reduced G6pc expression in hepatocytes (data not shown), suggesting that inhibition of hepatic Notch signaling can affect insulin sensitivity independent of FoxO1 levels. Nevertheless, our data in hepatocytes demonstrate the requirement for FoxO1 in G6pc induction with both ligand-dependent (recombinant DLL4) and –independent (N1-IC) activation of Notch, suggesting that both transcription factors are necessary for the full phenotype of diet-induced hepatic insulin resistance.

Foxo1+/−:Notch1+/− mice demonstrate a ~35% decrease in fasting G6pc expression, associated with ~20% decrease of glucose levels, twofold increase of hepatic glycogen, and reduced pyruvate to glucose conversion in vivo and in primary hepatocytes, suggestive of reduced gluconeogenesis and glycogenolysis. These findings dovetail with knockdown studies in which a similar decrease in G6pc levels and enzymatic activity led to a 15% reduction of glycemia and 50% increase of liver glycogen27. Foxo1+/−:Notch1+/− mice also phenocopy the decrease of G6pc expression, but not the hepatosteatosis and dyslipidemia observed in mice lacking hepatic steroid receptor coactivator-2 (ref. 28).

Decreased HGP in Foxo1+/−:Notch1+/− mice is also attributable to mechanisms independent of gluconeogenesis, such as decreased expression of sterol regulatory element binding transcription factor 1 (Srebf1) and its transcriptional targets29 (unpublished observations, U.P. & D.A.). In addition, HFD-fed FoxO1+/− and Foxo1+/−:Notch1+/− mice showed increased glycolysis in clamp studies. These pathways likely contribute to the overall phenotype of Foxo1+/−:Notch1+/− and L-Rbpj mice.

Clamp experiments also show that combined FoxO1 and Notch1 haploinsufficiency coordinately increases muscle glucose disposal, indicating that improved insulin sensitivity in these animals is not unique to the liver. Ablation of muscle FoxO1 promotes formation of fast-twitch fibers16. Should similar changes occur in FoxO1+/− and Foxo1+/−:Notch1+/− animals, they would contribute to increase glucose utilization. Foxo1+/− mice also show low adiponectin, either from direct FoxO1 transcriptional effects or from changes in visceral adiposity31,32. Given the insulin-like effects of adiponectin on HGP33,34, this decrease may partly mask the full extent of changes in HGP seen in FoxO1+/− and Foxo1+/−:Notch1+/− mice.

FoxO1 remains an elusive drug target due to its lack of ligand-binding domain, complex regulation, and broad transcriptional signature. Inhibition of Notch thus provides an alternative path to modulate FoxO1-dependent gluconeogenesis, as demonstrated by improved glucose tolerance in L-Rbpj mice. Unlike FoxOs, components of the Notch pathway have been validated as drug targets, and GSIs continue to elicit interest for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease35 and T-ALL22,36. Although there are significant limitations in the use of these compounds at this juncture, the improvement in liver glucose metabolism provides impetus to identify compounds with preferential hepatic effects, by dint of either distribution properties or preference for liver-enriched Notch receptors. It is envisioned that the availability of new Notch therapeutic agents36,37 will increase specificity and limit toxicity in targeting this pathway, thus paving the way for their use as insulin-sensitizers.

Online Methods

Antibodies

We purchased anti-FoxO1 (H-128, sc-11350), anti-G6pase-α (sc-33839) and anti-Rbp-Jκ (D-20, sc-8213) from Santa Cruz; anti-Akt1 (#9272), anti-phospo-IRS1 (#2388) and anti-phospho-Akt1 (#2965) from Cell Signaling; anti-IRS1 from Millipore (#06-248) and anti-Notch1 cleaved Val1744 (ab52301) from Abcam.

Experimental animals

We used intercrosses of Albumin-cre17, Rbpjflox (ref. 38), Foxo1flox (ref. 39), Foxo1+/− (ref. 40), and Notch1+/−(ref. 41) mice on C57BL/6 background to generate Foxo1+/−:Notch1+/−, albumin(cre):Rbp-Jκ flox/flox (L-Rbpj) and albumin(cre):Foxo1flox/flox (L-Foxo1) mice. Genotyping primers are listed in Supplemental Table 5. We weaned mice to either standard chow (Purina Mills #5053) or high-fat diet (18.4% calories/carbohydrates, 21.3% calories/protein and 60.3% calories/fat derived from lard; Harlan Laboratories, TD.06414). We purchased 8-wk-old C57BL6Lep/Lep (referred to as ob/ob) and 15-wk-old diet-induced obese mice from Jackson Labs.

Metabolic analyses

Assays for blood glucose (One Touch), plasma insulin (Millipore), adiponectin (Millipore), glucagon (Millipore) and triglycerides (Thermo) have been described42. We performed glucose tolerance tests after a 16-h (6PM-10AM) fast and insulin tolerance tests after a 4-h fast (8AM-12PM)8. We measured body composition by NMR (Bruker Optics), daily food intake with feeding racks (Fa. Wenzel) and energy expenditure by indirect calorimetry (TSE Systems)42. Hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp studies were performed as described43. To measure hepatic glycogen content, we homogenized frozen liver in 6% perchloric acid, adjusted to pH 6–7 with KOH followed by incubation with 1 mg/ml amyloglucosidase (Sigma) in 0.2 M acetate (pH 4.8) and quantification of glucose released (glycogen breakdown value – PCA value).

Hepatocyte isolation and glucose production

We cultured primary mouse hepatocytes as described19. We anesthetized mice with ketamine/xylazine (Sigma) and catheterized the inferior vena cava with a 23-gauge catheter (Becton Dickinson). We clamped the superior vena cava, transected the portal vein and infused 10cc HEPES-based perfusion solution followed by 100 cc type I collagenase solution (Worthington Biochemicals). We filtered cells into Percoll, plated them at 0.8×106 cells/well in 6-well dishes in Williams E with 5% FCS, then transferred them after 6 hours to medium containing 0.4% serum. At 24 h, we incubated cells in glucose-production medium (GPM, glucose- and serum-free, 3.3 g/L NaHCO3, 20 mM lactate, 2 mM pyruvate, 1% albumin). In some experiments, we incubated hepatocytes in GPM without lactate/pyruvate to assess baseline glycogenolysis, or with lactate/pyruvate to assess total glucose production. The difference between these two values was assumed to reflect gluconeogenesis44. Alternatively, we treated hepatocytes with increasing concentrations of insulin (0–300 pM, Sigma), dexamethasone (1 µM, Sigma), forskolin (10 µM, Sigma) and/or compound E (200 nM, Axxora) and analyzed glucose content in the medium (Amplex Red Glucose Oxidase kit, Invitrogen) and protein concentration in cell lysates (BCA assay, Pierce).

Quantitative RT-PCR

We isolated RNA with Trizol (Invitrogen) or RNeasy mini-kit (Qiagen), synthesized cDNA with Superscript III RT (Invitrogen), and performed qPCR with a DNA Engine Opticon 2 System (Bio-Rad) and DyNAmo HS SYBR green (New England Biolabs). mRNA levels were normalized to 18 s using the ΔΔC(t) method and are presented as relative transcript levels16. Primers are listed in Supplementary Table 4.

Adenovirus studies

FoxO1-ADA, FoxO1 shRNA, Notch1-IC and GFP adenoviruses have been described16,32. We transduced primary hepatocytes at MOI 5 to achieve 100% infection efficiency (as assessed by GFP expression). For in vivo studies, we injected 1×109 purified viral particles /g body weight via tail vein; we performed metabolic analysis on days 5–6 and sacrificed the animals at day 7 post-injection. We limited analysis to mice showing 2–5-fold Notch1 overexpression by Western blot.

Luciferase assays

We transfected Hepa1c1c7 cells with luciferase constructs containing varying lengths of G6pc promoter sequence with or without mutations as described45. Thereafter, we transduced cells with adenovirus, and analyzed them after 4 h in serum-free medium with or without recombinant 1 µg/ml DLL4 (R#00026;D Systems). In other experiments, we transfected plasmids containing synthetic FoxO1 target sequence derived from the Igfbp1 promoter to direct expression of a luciferase reporter gene, or a Rbp-Jκ reporter, both previously described18,46.

Dibenzazepine (DBZ) studies

DBZ was synthesized to >99.9% purity as assessed by LC/MS (Syncom) and suspended in a 0.5% Methocel E4M (w/v, Colorcon) and 0.1% Tween-80 (Sigma) solution23. Immediately prior to intraperitoneal injection (10 µmol/kg body weight), we sonicated DBZ for 2 min to achieve a homogeneous suspension.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation

We isolated intact chromatin and immunoprecipitated Rbp-Jk using ChIP-IT kit (Active Motif), from 12-wk-old male mice, after either a 16-h fast or 16-h fast/2-h refeed16. We minced the left hepatic lobe, rinsed it with PBS, crosslinked it with 1% formaldehyde for 10 min, treated with glycine for 5 min and subjected it to nuclear extraction. We subjected immunoprecipitated DNA to quantitative PCR with the following primers: 5′–TCCAAGAGCTGACATCCTCA–3′ (−1230 to −1211) and 5′–ACTGGATCCTAAAGTCCTGG–3′ (−1074 to −1055) to amplify the G6pc promoter. Fold enrichment was calculated by using a modified delta-Ct method and normalized to IP with negative IgG control (Sigma) antibody: Δ[C(t)IP-C(t)input 1:100].

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Supported by NIH grants DK57539 (D.A.), DK084583 (U.B.P.), DK63608 (Columbia Diabetes and Endocrinology Research Center), HL062454 (JK) and DK76169 (YaleMouse Metabolic Phenotyping Center). We thank D. Schmoll for the G6pc-luciferase constructs. We thank members of the Accili, Kitajewski and Shulman laboratories for insightful discussion of the data and acknowledge technical support from Ana Flete, Thomas Kolar and Taylor Lu. The Columbia University Institutional Animal Care and Utilization Committee has approved all animal procedures.

Competing financial interest statement

The Authors declare that they have no competing financial interest in the work described.

Author contributions

U.P. designed and performed experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript. C.J.S., A.L.B., and V.T.S. performed experiments and analyzed data. G.I.S., J.K., and D.A. designed the studies, analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript.

References

- 1.Accili D. Lilly lecture 2003: the struggle for mastery in insulin action: from triumvirate to republic. Diabetes. 2004;53:1633–1642. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.7.1633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kahn SE, et al. Glycemic durability of rosiglitazone, metformin, or glyburide monotherapy. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2427–2443. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa066224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim-Muller JY, Accili D. Cell biology. Selective insulin sensitizers. Science. 2011;331:1529–1531. doi: 10.1126/science.1204504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haeusler RA, Kaestner KH, Accili D. FoxOs function synergistically to promote hepatic glucose production. J Biol Chem. 2010 doi: 10.1074/jbc.C110.175851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nakae J, et al. Regulation of insulin action and pancreatic beta-cell function by mutated alleles of the gene encoding forkhead transcription factor Foxo1. Nat Genet. 2002;32:245–253. doi: 10.1038/ng890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nakae J, Park BC, Accili D. Insulin stimulates phosphorylation of the forkhead transcription factor FKHR on serine 253 through a Wortmannin-sensitive pathway. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:15982–15985. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.23.15982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Altomonte J, et al. Inhibition of Foxo1 function is associated with improved fasting glycemia in diabetic mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2003;285:E718–E728. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00156.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Matsumoto M, Pocai A, Rossetti L, Depinho RA, Accili D. Impaired regulation of hepatic glucose production in mice lacking the forkhead transcription factor Foxo1 in liver. Cell Metab. 2007;6:208–216. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fortini ME. Notch signaling: the core pathway and its posttranslational regulation. Dev Cell. 2009;16:633–647. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dufraine J, Funahashi Y, Kitajewski J. Notch signaling regulates tumor angiogenesis by diverse mechanisms. Oncogene. 2008;27:5132–5137. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weinmaster G, Kopan R. A garden of Notch-ly delights. Development. 2006;133:3277–3282. doi: 10.1242/dev.02515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zong Y, et al. Notch signaling controls liver development by regulating biliary differentiation. Development. 2009;136:1727–1739. doi: 10.1242/dev.029140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Loomes KM, et al. Bile duct proliferation in liver-specific Jag1 conditional knockout mice: effects of gene dosage. Hepatology. 2007;45:323–330. doi: 10.1002/hep.21460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xue Y, et al. Embryonic lethality and vascular defects in mice lacking the Notch ligand Jagged1. Hum Mol Genet. 1999;8:723–730. doi: 10.1093/hmg/8.5.723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oka C, et al. Disruption of the mouse RBP-J kappa gene results in early embryonic death. Development. 1995;121:3291–3301. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.10.3291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kitamura T, et al. A Foxo/Notch pathway controls myogenic differentiation and fiber type specification. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:2477–2485. doi: 10.1172/JCI32054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Postic C, Magnuson MA. DNA excision in liver by an albumin-Cre transgene occurs progressively with age. Genesis. 2000;26:149–150. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1526-968x(200002)26:2<149::aid-gene16>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Das I, et al. Notch oncoproteins depend on gamma-secretase/presenilin activity for processing and function. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:30771–30780. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309252200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nakae J, Kitamura T, Silver DL, Accili D. The forkhead transcription factor Foxo1 (Fkhr) confers insulin sensitivity onto glucose-6-phosphatase expression. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:1359–1367. doi: 10.1172/JCI12876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang J, et al. Effects of adenovirus-mediated liver-selective overexpression of protein tyrosine phosphatase-1b on insulin sensitivity in vivo. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2001;3:367–380. doi: 10.1046/j.1463-1326.2001.00173.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rand MD, et al. Calcium depletion dissociates and activates heterodimeric notch receptors. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:1825–1835. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.5.1825-1835.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wolfe MS. gamma-Secretase in biology and medicine. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2009;20:219–224. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2008.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Es JH, et al. Notch/gamma-secretase inhibition turns proliferative cells in intestinal crypts and adenomas into goblet cells. Nature. 2005;435:959–963. doi: 10.1038/nature03659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Milano J, et al. Modulation of notch processing by gamma-secretase inhibitors causes intestinal goblet cell metaplasia and induction of genes known to specify gut secretory lineage differentiation. Toxicol Sci. 2004;82:341–358. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfh254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Samuel VT, et al. Targeting foxo1 in mice using antisense oligonucleotide improves hepatic and peripheral insulin action. Diabetes. 2006;55:2042–2050. doi: 10.2337/db05-0705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Accili D, Arden KC. FoxOs at the crossroads of cellular metabolism, differentiation, and transformation. Cell. 2004;117:421–426. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00452-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang A, et al. Functional silencing of hepatic microsomal glucose-6-phosphatase gene expression in vivo by adenovirus-mediated delivery of short hairpin RNA. FEBS Lett. 2004;558:69–73. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(03)01499-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chopra AR, et al. Absence of the SRC-2 coactivator results in a glycogenopathy resembling Von Gierke's disease. Science. 2008;322:1395–1399. doi: 10.1126/science.1164847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Horton JD, Goldstein JL, Brown MS. SREBPs: activators of the complete program of cholesterol and fatty acid synthesis in the liver. J Clin Invest. 2002;109:1125–1131. doi: 10.1172/JCI15593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim JJ, et al. FoxO1 haploinsufficiency protects against high-fat diet-induced insulin resistance with enhanced peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma activation in adipose tissue. Diabetes. 2009;58:1275–1282. doi: 10.2337/db08-1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nakae J, et al. Forkhead transcription factor FoxO1 in adipose tissue regulates energy storage and expenditure. Diabetes. 2008;57:563–576. doi: 10.2337/db07-0698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nakae J, et al. The forkhead transcription factor Foxo1 regulates adipocyte differentiation. Dev Cell. 2003;4:119–129. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00401-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Berg AH, Combs TP, Du X, Brownlee M, Scherer PE. The adipocyte-secreted protein Acrp30 enhances hepatic insulin action. Nat Med. 2001;7:947–953. doi: 10.1038/90992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pajvani UB, et al. Structure-function studies of the adipocyte-secreted hormone Acrp30/adiponectin. Implications fpr metabolic regulation and bioactivity. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:9073–9085. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207198200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Woo HN, Park JS, Gwon AR, Arumugam TV, Jo DG. Alzheimer's disease and Notch signaling. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;390:1093–1097. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.10.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Purow B. Notch inhibitors as a new tool in the war on cancer: a pathway to watch. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2009;10:154–160. doi: 10.2174/138920109787315060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moellering RE, et al. Direct inhibition of the NOTCH transcription factor complex. Nature. 2009;462:182–188. doi: 10.1038/nature08543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fujikura J, et al. Notch/Rbp-j signaling prevents premature endocrine and ductal cell differentiation in the pancreas. Cell Metab. 2006;3:59–65. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Paik JH, et al. FoxOs Are Lineage-Restricted Redundant Tumor Suppressors and Regulate Endothelial Cell Homeostasis. Cell. 2007;128:309–323. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.12.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hosaka T, et al. Disruption of forkhead transcription factor (FOXO) family members in mice reveals their functional diversification. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:2975–2980. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400093101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Krebs LT, et al. Notch signaling is essential for vascular morphogenesis in mice. Genes Dev. 2000;14:1343–1352. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Plum L, et al. The obesity susceptibility gene Cpe links FoxO1 signaling in hypothalamic pro-opiomelanocortin neurons with regulation of food intake. Nat Med. 2009;15:1195–1201. doi: 10.1038/nm.2026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lin HV, et al. Divergent regulation of energy expenditure and hepatic glucose production by insulin receptor in agouti-related protein and POMC neurons. Diabetes. 2010;59:337–346. doi: 10.2337/db09-1303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Collins QF, et al. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG), a green tea polyphenol, suppresses hepatic gluconeogenesis through 5'-AMP-activated protein kinase. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:30143–30149. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702390200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schmoll D, et al. Regulation of glucose-6-phosphatase gene expression by protein kinase Balpha and the forkhead transcription factor FKHR. Evidence for insulin response unit-dependent and -independent effects of insulin on promoter activity. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:36324–36333. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003616200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kitamura YI, et al. FoxO1 protects against pancreatic beta cell failure through NeuroD and MafA induction. Cell Metab. 2005;2:153–163. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.