Abstract

Capsaicin, the classic activator of TRPV-1 channels in primary sensory neurons, evokes nociception. Interestingly, auditory reception is also modulated by this chemical, possibly by direct actions on outer hair cells (OHCs). Surprisingly, we find two novel actions of capsaicin unrelated to TRPV-1 channels, which likely contribute to its auditory effects in vivo. First, capsaicin is a potent blocker of OHC K conductances (IK and IK,n). Second, capsaicin substantially alters OHC nonlinear capacitance, the signature of electromotility – a basis of cochlear amplification. These new findings of capsaicin have ramifications for our understanding of the pharmacological properties of OHC IK, IK,n and electromotility and for interpretation of capsaicin pharmacological actions.

Keywords: capsaicin, hair cell, inner ear, potassium channel, cochlear amplifier

1. Introduction

The mammalian cochlea contains two types of hair cells with distinct functions. Inner hair cells (IHCs)1 are responsible for sound detection and its conversion to electrical signals. Whereas, outer hair cells (OHCs)2 additionally amplify sound stimulus by increasing both the amplitude and frequency selectivity of basilar membrane (BM)3 vibration. Electrically evoked OHC mechanical activity, whose electrical signature is a nonlinear capacitance (NLC)4, is a basis of this cochlear amplification (Dallos et al., 2008; He et al., 2006; Santos-Sacchi, 2003; Santos-Sacchi et al., 2006; Zheng et al., 2003). IK and IK,n are the two major K conductances in OHCs (Housley et al., 1992; Housley et al., 2006; Mammano et al., 1996; Santos-Sacchi et al., 1988). IK activates at potentials more positive than −35 mV and its identity and role is still unclear. IK,n, which activates at hyperpolarized potentials, is carried by KCNQ4 channels and controls the resting potential of OHCs (Chambard et al., 2005; Holt et al., 2007; Kharkovets et al., 2000; Kharkovets et al., 2006; Wu et al., 2010; Xu et al., 2007). The resting potential is an important component of the driving force for OHC electromotility.

Capsaicin, the natural product of capsicum pepper, is an active ingredient of many spicy foods. Capsaicin selectively activates TRPV-1, a non-selective cation channel (NSCC)5 in primary sensory neurons, initiating nociception through its depolarizing effects. This is the classical action of capsaicin (Caterina et al., 1997; Szallasi et al., 1999). Interestingly, we showed that capsaicin reduced cochlear amplification, resulting in an elevation in the threshold of the auditory nerve compound action potential in an in vivo study (Zheng et al., 2003). Furthermore, we and others have observed TRPV-1 immunolabeling in OHCs (Ishibashi et al., 2008; Mukherjea et al., 2008; Zheng et al., 2003). From these data, we hypothesized that OHCs were the major target of capsaicin, and activation of TRPV-1 would result in OHC depolarization leading to a reduction in both receptor potential and evoked OHC motility. Therefore, it is of particular interest to understand the action of capsaicin on OHCs at the cellular level.

In this study, we whole-cell voltage clamped isolated OHCs. Surprisingly, capsaicin did not elicit characteristic TRPV-1 currents in the OHCs. Unexpectedly, we found that capsaicin is a potent blocker of OHC K conductances (IK and IK,n) and alters NLC substantially. These novel pharmacological effects of capsaicin have never been reported before and likely contribute to the drug’s detrimental action on cochlear amplification in vivo.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 OHC preparation

Adult guinea pigs (250–350 g) with positive Preyer’s reflex were anesthetized by intramuscular injection of an anesthetic mixture (60 mg/ml ketamine, 2.4 mg/ml xylazine, and 1.2 mg/ml acepromazine in saline) at a dose of 1 ml kg−1 and were then killed by decapitation. The cochleae were rapidly removed from the bulla and dissected in a Petri dish filled with a standard artificial perilymph composed of (mM): NaCl 144, KCl 4, CaCl2 1.3, MgCl2 0.9, Na2HPO4 0.7, HEPES 10 and glucose 5.6. The osmolarity of the solution was adjusted to 304 mosmol/l with glucose and the pH was adjusted to 7.40 with NaOH. All procedures were performed at room temperature. The organ of Corti dissected from the apical two cochlear turns was digested with dispase I (1.0 mg/ml) for 12 min. Dissociated OHCs, obtained by gentle titration, were placed in a Petri dish and allowed to settle onto the glass bottom. They were continuously perfused with the artificial perilymph. OHCs with lengths ranging from 72–75 μm (the upper 3rd turn, used in most of experiment unless otherwise specified) and 48–55 μm (the lower 2nd turn) were chosen for patch recordings. All procedures in this study were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Oregon Health & Science University.

2.2 Solutions for OHC recordings

All reagents were from Sigma-Aldrich. In the bath solutions, agents were added as 1000 X concentrates. Capsaicin was pre-dissolved in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO), which was used at a final concentration of 0.1% DMSO. BaCl2 and 4-AP were pre-dissolved in water. The drugs were gravity delivered at a rate of (0.35 ml min−1) through an array of parallel polyethylene tubes with an inner diameter of ~280 μm at the distal end, which was positioned ~350 μm next to the OHCs. Rapid switching of two different solutions was performed by shifting loaded tubes.

a) Solutions for current recordings

Bath solution contained (in mM): NaCl 142, KCl 5, CaCl2 1.5, MgCl2 2, Hepes 10 and D-glucose 5.6. The pH was adjusted to 7.40 with NaOH and the osmolarity to 304 mosmol/l with D-glucose. Pipette solution (mM) contained (in mM): KCl 148, CaCl2 0.5, MgCl2 2, Hepes 10 and EGTA 1. The pH was adjusted to 7.40 with KOH and the osmolarity to 298 mosmol/l with D-glucose.

b) Solutions for NLC recordings

Bath solution (mM) was NaCl 132, CaCl2 2, MgCl2 2, and Hepes 10. Pipette solution was the same except with EGTA 10. In a subset of experiments, Ca was removed from both intracellular and extracellular solutions by substituting NaCl. The extracellular solution contained 3, 10, 30, 100, 300 and 1000 μM capsaicin. The pH was adjusted to 7.20 with NaOH and the osmolarity to 300 mosmol/l with D-glucose. We have previously shown that DMSO and ethanol at the concentrations used in this report do not affect measures of NLC (Rybalchenko et al., 2003; Song et al., 2005).

2.3 Whole cell recordings of OHC

In regular current detection procedures, an Axopatch 1-D amplifier (Axon Instruments) was used with its low-pass filter bandwidth set to 1 kHz (four-pole Bessel). Membrane currents were recorded with a Digidata 1322A (Axon Instruments) interface and pCLAMP 8 software (Axon Instruments) at a sampling rate of 10 kHz for episodic I-V commands and with Minidigi digitizer and Axoscope 9.2 software (Axon Instruments) for simultaneous gap-free recording at a sampling rate of 50 Hz. The whole cell configuration was achieved by rupturing the cell membrane with suction after achieving a high-resistance seal (>1.5 gigohm). Stability of the patch was ascertained by monitoring gap-free recording and cell parameters (cell capacitance (Ccell), membrane resistance (Rm) and series resistance (Rs)) during the recordings. The patch pipettes were pulled in four steps from borosilicate capillaries (WPI, 1B150F-4) using a puller (P80/PC Sutter Instrument). In a regular Na+ rich bath and K+ rich pipette solution, the initial pipette resistance was 6–7 MΩ. The uncompensated Rs (MΩ) were off-line corrected with the equation Vc=Vu−I×Rs (Vc, corrected clamping voltage; Vu, uncorrected clamping voltage; I, current) in Excel sheets and Origin 7.5 (OriginLab Technical) files. In order to stabilize liquid junction potential (LJP), a salt bridge (3 M NaCl) with a ceramic tip was used as a reference electrode. The LJP (actual measurement) was 3 mV in the regular Na+ rich bath and K+ rich pipette solutions. Th LJP was corrected in the Excel sheets and Origin 7.5 (OriginLab Technical) files. Data were analyzed by clampfit 9.0 (Axon Instruments) and Origin 7.5 (OriginLab Technical).

2.4 Nonlinear capacitance measurements

OHC capacitance was measured with a continuous high-resolution (2.56 ms) two-sine voltage stimulus protocol (10mV peak at both 390.6 and 781.2 Hz), and subsequent FFT based admittance analysis as fully described previously (Santos-Sacchi et al., 1998). These small, high frequency sinusoids were superimposed on voltage ramps that spanned +/− 180 mV. All data collection and most analyses were performed with an in-house developed Window’s based whole-cell voltage clamp program, jClamp (www.scisoft.com), utilizing a Digidata 1320 board (Axon, CA). Matlab (Natick, MA) or SigmaPlot was used for fitting the Cm data.

C–V data were fit with the first derivative of a two-state Boltzmann function and a constant representing the linear capacitance (Santos-Sacchi, 1991),

| eq.1 |

where Qmax is the maximum nonlinear charge moved, Vpkcm is voltage at peak capacitance or half maximal nonlinear charge transfer, Vm is membrane potential, Clin is linear capacitance, z is apparent valence, e is electron charge, k is Boltzmann’s constant, and T is absolute temperature.

2.5 TRPV1 immunofluorescence labeling in OHCs of guinea pigs and Trpv1 −/− mice

The cochleae of guinea pigs, Trpv1 −/− mice, and the wild type control mice with the same background (Jackson Lab) were dissected and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde solution overnight. After being washed in 0.02 M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 30 min, the tissues were permeabilized in 0.5% Triton X-100 (Sigma) for 1 hour (h) and incubated in 10% goat serum and 1% bovine serum in 0.02 M PBS for 1 h. The tissues were incubated overnight in primary anti-TRPV1 (rabbit polyclonal, RA10110, Neuromics, Edina, MN, USA) diluted to 1:500 with 1% BSA-PBS. After being washed in 1% BSA-PBS for 30 min, the tissues were incubated in Alexa fluor 488 anti-rabbit IgG (diluted to 1:100) and Alexa fluor 568 phalloidin (diluted to 1:50, Invitrogen, Eugene, OR, USA) for 1 h and Hoechst (1 μg/ml, Invitrogen, Eugene, OR, USA) for 15 min. After being washed in 0.02 M PBS for 30 min, the tissues were mounted and observed on a Nikon Eclipse TE 300 inverted microscope fitted with an Olympus Fluview confocal laser microscope system. Negative controls were 1) tissue incubated with 1% BSA-PBS to replace the primary antibody, 2) tissue with the primary antibody (TRPV-1) and its blocking peptide (10−4 M) (Neuromics, Edina, MN, USA), and 3) tissues from the Trpv1 −/− mice.

2.6 Statistics

Data are presented as means ± SE from n observations. Student’s t-test (paired or non-paired as appropriate) was performed using Microsoft Excel software; p ≤ 0.05 represents a significant difference.

3. Results

3.1 Capsaicin blocks two types of potassium currents in OHCs, IK and IK,n

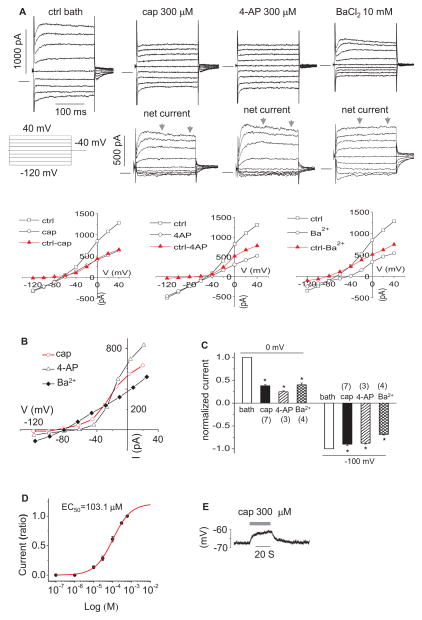

In our standard Na+ rich bath and K+ rich pipette solutions, upper 3rd turn OHCs presented two previously described K+ currents (Fig. 1A) (Housley et al., 1992); IK, a slowly developing outward current showing slight inactivation (activated above −40 mV), and IK,n, an inward current which relaxes during large hyperpolarizing steps (−120 mV). Capsaicin (300 μM) reversibly abolished IK and slightly reduced IK,n. The effects are analogous to the previously observed actions of 4-AP (300 μM) (Mammano et al., 1996) (Fig. 1A). In comparison, Ba2+ (10 mM) blocked most of IK,n, without a significant block of IK. The reversal potential (Vr) of the capsaicin sensitive current was −83.6±4.3 (n=7), which is comparable to that of the 4-AP and barium sensitive current (−70.5±0.5 (n=3) and −82.5±0.8 (n=4), respectively), suggesting a high selectivity to K+ (Fig. 1B) (The K+ equilibrium potential (EK) was −88 mV). From step protocols, average reductions in steady state outward currents at 0 mV for capsaicin, 4-AP, and Ba2+ were 62.1 %, 75.2 %, and 59.9 %, respectively (n=4–7; p<0.05; Fig. 1C). Average reductions in steady state inward currents at −100 mV for capsaicin, 4-AP, and Ba2+ were 10.1 %, 12.2 %, and 31.2 %, respectively (n=3–7; p<0.05; Fig. 1C). The capsaicin elicited reduction in the outward current was concentration-dependent with EC50=103.1 μM when held at 0 mV (Fig. 1D). Capsaicin depolarized OHCs by 4.0±0.5 mV (Fig. 1E), shifting the resting potential, which is driven by IK,n (Housley et al., 1992), from −67.9±1.5 to −63.9± 1.8 mV (n=7, p<0.05), which is consistent with a small but significant inhibition of IK,n by capsaicin.

Figure 1.

Capsaicin blocks IK and IK,n of OHCs from the upper third turn. A. representative currents (of 72 μM OHC) induced by step voltage commands following application of capsaicin (cap), 4-AP and BaCl2. Net currents (cap, 4-AP and Ba2+ sensitive current) are after subtraction from control (ctrl) currents in bath. The ctrl current in the figure is for capsaicin and the ctrl for 4-AP and BaCl2 are not shown here. The zero current is shown as a solid horizontal bar preceding the step currents. Representative I–V plots were produced for each original recordings B. representative I–V plots of net currents in A. The current for each voltage (V) is the 100 ms average bounded by the arrows. C. bar graph summary: 300 μM capsaicin, 300 μM 4-AP and 10 mM BaCl2 blocked outward currents at 0 mV and inward currents at −100 mV. Currents were normalized by the currents in ctrl bath. * P<0.05. D. dose response curve of capsaicin sensitive current at 0 mV (n=5). Current (ratio): currents normalized by the current at 600 μM capsaicin. E. representative recording of membrane potential with 300 μM capsaicin.

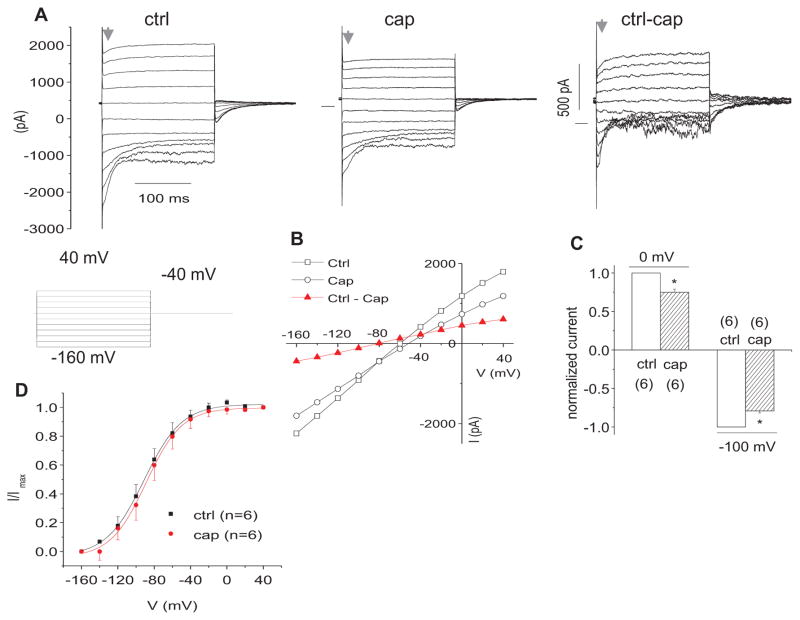

To further study the effect of capsaicin on IK,n, we used lower 2nd turn OHCs, which presented much larger IK,n, but little IK (Fig. 2A). We found that Capsaicin (300 μM) partially inhibited IK,n (Fig. 2A). The IV plot showed that capsaicin caused a current reduction in the whole range of voltage commands with Vr of capsaicin sensitive current at ~−80 mV (Fig. 2B). Average reductions in steady state inward currents for capsaicin are 25.1% (at 0 mV) and 20.9% (at −100 mV) (Fig. 2C). Figure 2D shows the effect of capsaicin (300 μM) on the steady- state activation curve of IK,n, which was determined from tail currents with the voltage protocol in Figure 2A. Capsaicin did not significantly shift the Vhalf. The Vhalf (mV) and slope factor (S) (mV) are −91.2±2.3 (n=6) and 20.8±2.1 (n=8), respectively for capsaicin treatment, versus − 88.9±2.1 (Vhalf) and 19.7±1.9 (S) for control. The Vhalf of IK,n was consistent with previous findings (Housley et al., 1992; Jagger et al., 1999b).

Figure 2.

Capsaicin blocks IK,n of OHCs from the lower 2nd turn. A. representative currents in control (ctrl) bath and following application of 300 μM capsaicin (cap). Net currents (ctrl-cap) are after subtraction from control (ctrl) currents in bath. B. representative I–V plots of the currents in A. C. bar graph summary: 300 μM cap blocked outward currents at 0 mV and inward currents at −100 mV. Currents were normalized by the currents in ctrl. * P<0.05. D. Effect of cap (0.1 mM) on steady-state activation curve of IK,n. Normalized tail current amplitudes versus prepulse potentials were fitted with a first-order Boltzmann function (n=6): I= Imax/(1+exp ((V−Vhalf)/S), where Imax is the fully activated current amplitude at the tail-current potential, Vhalf is the potential at half-maximal activation, V is prepulse potentials and S is the slope factors.

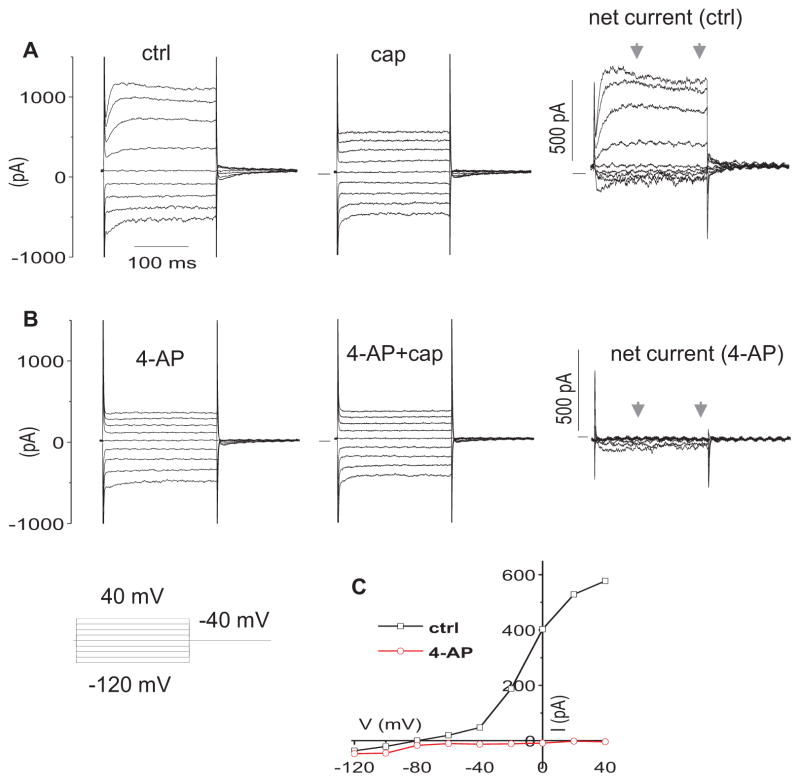

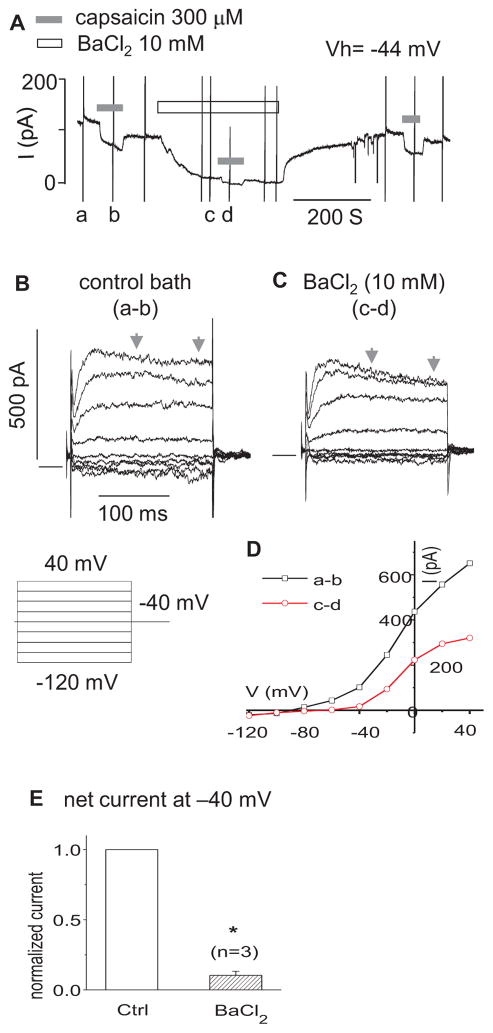

Consistent with the above findings, capsaicin sensitive currents (the upper 3rd turn OHCs) were blocked by 4-AP (300 μM) and BaCl2 (10 mM). 4-AP (300 μM) blocked all capsaicin sensitive outward currents in step protocols (n=3) (Fig. 3). In Figure 4A, when held at −44 mV (where IK,n is predominantly activated), OHCs presented a net outward current, i.e. a positive current above zero, in continuous gap-free recordings. Capsaicin (300 μM) reversibly inhibited the outward current by shifting it negatively. The shift was reduced in the presence of BaCl2 (10 mM). In step protocols (Fig 4. B, C, D, E), BaCl2 (10 mM) reduced the capsaicin sensitive current at −40 mV by 89.6% (n=3, p<0.05) and at 0 mV by 55.7 % (n=3, p<0.05).

Figure 3.

4-AP blocks the net capsaicin currents. A. representative currents in ctrl bath and following application of 300 μM capsaicin (cap). Net currents (ctrl-cap) are after subtraction from ctrl currents in bath. B. representative currents in 4-AP (300 μM) bath and following application of 300 μM cap. Net currents (cap-sensitive currents) are after subtraction from the currents in 4-AP bath. C. representative I–V curves of net currents in A and B. The current for each V is the 100 ms average bounded by the arrows.

Figure 4.

BaCl2 partially blocks the net capsaicin currents. A. representative current in gap-free mode at holding voltage of −44 mV. The vertical spike currents, such as a, b, c and d, were caused by the I–V step voltage commands as shown in B. B. net capsaicin (300 μM) currents (a–b) in control bath. The zero current was shown as a solid horizontal bar preceding the step currents in B and C. C. net capsaicin (300 OM) currents (c–d) in the bath with 10 mM BaCl2. D. representative I–V curves of net currents in B and C. The current for each V is the 100 ms average bounded by the arrows. E. bar graph summary: the net capsaicin currents at Vh of −40 mV in the control (ctrl) and BaCl2 (10 mM) bath. The currents were normalized by the currents of ctrl. * P<0.05, n=3.

We also tested the effect of capsaicin on IK and IK,n at the concentration used in our previous in vivo study (Zheng et al., 2003). Consistent with that study, 20 μM capsaicin produced a small but significant reduction of IK and IK,n. From step protocols (shown in Fig. 1), average reductions in steady state outward currents for capsaicin (20 μM) were 8.4 % at 0 mV (p<0.05, n=10) and 6.5 % at −100 mV (p<0.05, n=10) (Fig. 5).

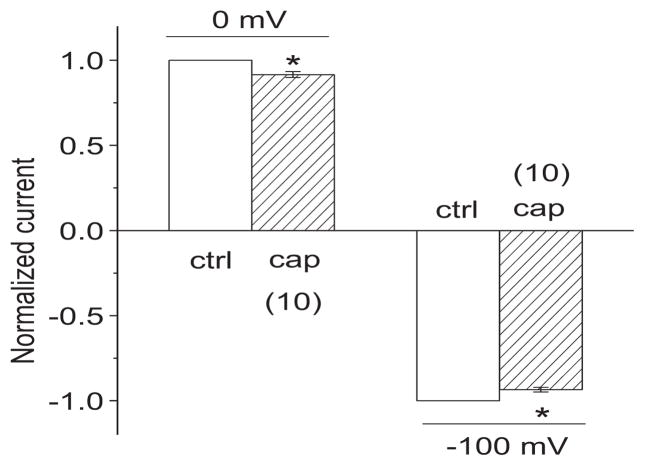

Figure 5.

Capsaicin blocks IK and IK,n at the concentration (20 μM) used in previous in vivo studies. Bar graph summary: 20 μM capsaicin (cap) (n=10) significantly blocked outward currents at 0 mV and inward currents at −100 mV with step protocols (shown in Fig. 1). Currents were normalized by the currents in ctrl bath. * P<0.05.

3.2 Capsaicin alters electromotility

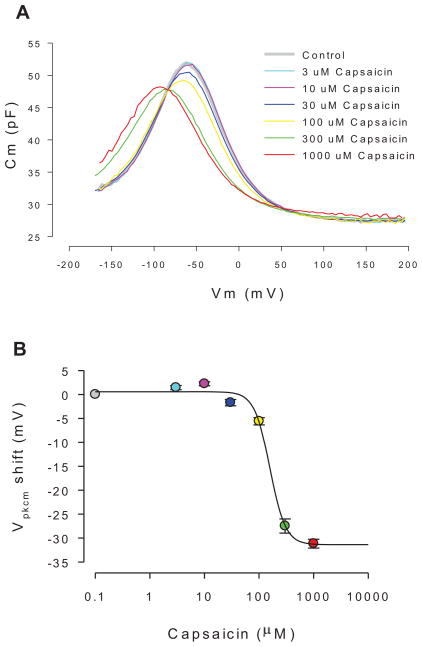

Application of extracellular capsaicin altered OHC nonlinear capacitance, the electrical signature of electromotility. Fig 6a shows the effects of increasing concentrations on the C-V function. The drug shifted Vpkcm to the left and reduced peak capacitance for concentrations over 30 μM. The shifts of Vpkcm for concentrations 30, 100, 300 and 1000 μM capsaicin perfusions were 1.67 ± 0.34, 4.98 ± 1.01, 25.03 ± 1.34 and 29.94 ± 1.16 mV, respectively (se, n=5, P<0.05). Reductions in nonlinear peak capacitance for concentrations 30, 100, 300 and 1000 μM capsaicin perfusions were 1.21 ± 0.35, 2.03 ± 0.49, 3.81 ± 0.58 and 3.39 ± 0.55 pF, respectively (se, n=5, P<0.05). No significant differences were found when cells were held at 0 or −70 mV. The concentration dependence of the Vpkcm shift is shown in Fig 6b. A Hill fit gives a half maximal shift (EC50) at 158 μM (n=8). Removing Ca2+, both extracellular and intracellular, reduced the Vpkcm shift at the two highest concentrations, namely −17.3 mV at 300 μM (p=0.04) and −22.3 mV at 1000 μM (p=0.07). This resulted in an increase in the EC50 to 204 μM. Reducing intracellular and extracellular chloride levels to 1 mM did not alter the ability of capsaicin to shift the Vpkcm.

Figure 6.

Representative effects of capsaicin on OHC NLC. A. Cm-Vm plots for increasing concentrations of capsaicin. Both a decrease in peak capacitance and shift in voltage at peak capacitance result from drug exposure. B. Dose response function with standard errors, showing an IC50 of 158 μM (n=8). The data are statistically significant at 10uM and above (p<0.013), showing a biphasic response shift at low concentrations. Peak NLC reduction is significant at 30 uM and above (p<0.05).

3.3 TRPV1 immunofluorescence labeling in OHCs of guinea pigs and Trpv1 −/− mice

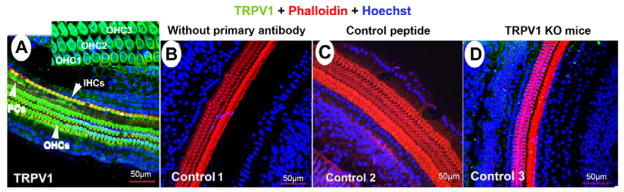

TRPV-1 labeling was found in the basolateral membrane of the OHCs and IHCs of the guinea pigs (Fig 7A) and Trpv1 +/+ mice (similar to guinea pigs, data not shown). No significant TRPV-1 labeling was found in the OHCs and IHCs in the negative controls including 1) primary antibody only (Fig 7B), 2) with control peptide (Fig 7C), and 3) the Trpv1 −/− mice (Fig 7D). TRPV-1 labeling was also found in supporting cells including pillar cells and Hensen’s cells (Fig 7A).

Figure 7.

TRPV1 immunofluorescence labeling of guinea pig and Trpv1 −/− mice. A, a representative confocal projection image showing TRPV1 immunolabelling in OHCs, IHCs and pillar cells of guinea pigs. The insert shows that TRPV1 is expressed in the basolateral membrane of OHCs. No significant labeling was found in OHCs, IHCs and PCs of negative controls incuding 1) primary antibody only (B), 2) with control peptide (C) and 3) Trpv1 −/− mice (Fig D). TRPV1 labeling of Trpv1 +/+ mice is similar to guinea pigs (data not shown).

4. Discussion

4.1 Capsaicin blocks IK and IK,n

There are several types of K currents expressed in adult guinea pig OHCs, IK and IK,n being the two major ones (Housley et al., 1992; Housley et al., 2006; Mammano et al., 1996; Santos-Sacchi et al., 1988). IK, which activates at potentials more positive than −35 mV, is most prominent in the apical turn (Housley et al., 1992) and is specifically blocked by 4-AP (Mammano et al., 1996). IK,n, which activates at hyperpolarized potentials more negative than − 40 mV, is most prominent in the basal turn and is more susceptible to barium (10 mM) (Mammano et al., 1996). IK,n is carried by KCNQ4 channels (Chambard et al., 2005; Holt et al., 2007; Kharkovets et al., 2000; Kharkovets et al., 2006) and dominates the OHC membrane conductance at the resting potential. These conductances are restricted to the basal pole of the OHC (Santos-Sacchi et al., 1997).

Our findings indicate that capsaicin is a potent IK blocker; 300 μM capsaicin, similar to 300 μM 4-AP, abolished most of the current (Fig 1). The reversal potential (Vr) of the capsaicin sensitive current (−83.6 mV) was close to that expected for a K conductance (−88 mV), suggesting most of the capsaicin sensitive current under these conditions was carried by potassium. That 4-AP completely blocked the outward capsaicin sensitive current in step protocols is another piece of evidence that capsaicin and 4-AP work similarly (Fig 3). The potency of capsaicin was slightly less than 4-AP; the outward current at 0 mV was reduced by 62.1 % for capsaicin (300 μM) and by 75.2 % for 4-AP (300 μM). Unlike IK,n (KCNQ4), the molecular identity of IK has not been successfully discovered, although some candidates have been proposed and some efforts have been made (Ashmore et al., 1986; Jagger et al., 1999a).

Capsaicin also reduced IK,n. This conclusion is supported by the following findings in the upper 3rd turn OHCs. 1) Capsaicin slightly depolarized OHCs by 4 mV. 2) At −44 mV, where IK,n is the dominant current, capsaicin caused a considerable negative shift of an outward current in gap-free recording (Fig 4A). 3) The shift caused by capsaicin was blocked by barium (10 mM). 4) In step protocols, barium (10 mM) significantly blocked the capsaicin sensitive current (Fig. 4B, C, D, and E). However, the reduction of IK,n, though statistically significant (p<0.05), was quite small for capsaicin (300 μM), with a reduction of inward current at −100 mV by 12.2 %. In comparison, barium (10 mM) reduced the inward current by 31.2 %. In the short OHCs (the lower 2nd turn) with larger IK,n, capsaicin reduced more inward current (by 20.9% at −100 mV).

Our study is the first to report the blocking effects of capsaicin on K conductances in cochlear hair cells. Capsaicin has been previously reported to block voltage gated K currents in a variety of different cells including Schwann cells, dorsal root ganglion cells, T cells, vertebrate axons, and some mammalian cell lines with an IC50 ranging from 23 to 158 μM (Grissmer et al., 1994). These values are comparable to our observation of 103.1 μM. More interestingly, capsaicin was found to block a KCNQ current in the vestibular type II hair cells of the gerbil (Rennie et al., 2001) and a delayed rectifier K+ current in the vestibular hair cells of frog semicircular canals (Marcotti et al., 1999). Analogous to our findings in guinea pig OHCs, the K conductance of the frog vestibular hair cells was also pharmacologically separated into two complementary components: a capsaicin-sensitive current and a barium-sensitive current (Marcotti et al., 1999).

4.2 Capsaicin alters OHC electromotility

The electrically evoked OHC mechanical response underlies mammalian cochlear amplification (Brownell, 1984; Liberman et al., 2002; Santos-Sacchi et al., 2006). Here we show that capsaicin can significantly reduce NLC and shift its operating voltage range. Changes in NLC are known to correspond to changes in electromotility (see (Kakehata et al., 1995), and shifts in the operating range are predicted to alter the cell’s mechanical gain. We show that capsaicin is not working through changes in intracellular chloride levels, which are known to be important for OHC motor function (Oliver et al., 2001; Rybalchenko et al., 2003; Santos-Sacchi, 2003; Song et al., 2005), but may work directly on the motor protein, prestin. It is the first study to report that capsaicin has a direct action on OHC electromotility.

4.3 TRPV-1 considerations

We confirmed that TRPV-1 immunolabeling is observed in normal guinea pig and mouse OHCs, IHCs, and supporting cells (pillar cells and Hensen’s cells), as previously shown by us and others (Ishibashi et al., 2008; Mukherjea et al., 2008; Zheng et al., 2003). However, immunolabeling is absent in Trpv1 −/− mice. Given these strong data, it is surprising that we did not see characteristic TRPV-1 currents in isolated OHCs at capsaicin concentrations ranging from 0.1 to 600 μM. There are a couple of possibilities for this quandary. First, it is possible that the native TRPV-1 is functional in vivo, but was inactivated during the relatively harsh OHC isolation procedure. It has been reported that isolated OHCs are loaded with more Ca2+ and Na+ and have less polarized resting potential and significantly reduced input resistance (Mammano et al., 1995). Second, it may be possible that the native TRPV-1 expressed in OHCs is non functional, similar to normal TRPLM3 (Grimm et al 2007). Consequently, in the first case, the action of capsaicin on IK, IK,n, and NLC of OHCs would have been augmented by TRPV-1 block in accounting for our previous in vivo finding of reduced amplification. To be sure, the capsaicin concentration of our in vivo study (20 μM) was found to produce a significant reduction of IK, IK,n (Fig 5) and a significant shift of NLC (Fig 6). Nevertheless, we cannot rule out that capsaicin’s action on IHCs and supporting cells may also have contributed to our in vivo findings.

In summary, we hypothesize that the reduction of IK and IK,n by capsaicin led to a depolarization of OHCs, which consequently decreased the driving force for transduction current. The resulting reduced drive for OHC electromotility in combination with the direct action of capsaicin on electromotility was likely causal in reducing cochlear amplification. The possible contributory role of supporting cells and IHCs remains under investigation.

Acknowledgments

NIH grants DC 005983, DC 000141 (ALN), DC 000273 (JSS), DC 008130 (JSS), DC 004716 (JZG).

Footnotes

inner hair cells (IHCs)

outer hair cells (OHCs)

basilar membrane (BM)

nonlinear capacitance (NLC)

non-selective cation channel (NSCC)

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ashmore JF, Meech RW. Ionic basis of membrane potential in outer hair cells of guinea pig cochlea. Nature. 1986;322:368–71. doi: 10.1038/322368a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownell WE. Microscopic observation of cochlear hair cell motility. Scan Electron Microsc. 1984:1401–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caterina MJ, Schumacher MA, Tominaga M, Rosen TA, Levine JD, Julius D. The capsaicin receptor: a heat-activated ion channel in the pain pathway. Nature. 1997;389:816–24. doi: 10.1038/39807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambard JM, Ashmore JF. Regulation of the voltage-gated potassium channel KCNQ4 in the auditory pathway. Pflugers Arch. 2005;450:34–44. doi: 10.1007/s00424-004-1366-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallos P, Wu X, Cheatham MA, Gao J, Zheng J, Anderson CT, Jia S, Wang X, Cheng WHY, Sengupta S, He DZZ, Zuo J. Prestin-based outer hair cell motility is necessary for mammalian cochlear amplification. Neuron. 2008;58:333–339. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.02.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grissmer S, Nguyen AN, Aiyar J, Hanson DC, Mather RJ, Gutman GA, Karmilowicz MJ, Auperin DD, Chandy KG. Pharmacological characterization of five cloned voltage-gated K+ channels, types Kv1.1, 1.2, 1.3, 1.5, and 3.1, stably expressed in mammalian cell lines. Mol Pharmacol. 1994;45:1227–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He DZ, Zheng J, Kalinec F, Kakehata S, Santos-Sacchi J. Tuning in to the amazing outer hair cell: membrane wizardry with a twist and shout. J Membr Biol. 2006;209:119–34. doi: 10.1007/s00232-005-0833-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt JR, Stauffer EA, Abraham D, Geleoc GS. Dominant-negative inhibition of M-like potassium conductances in hair cells of the mouse inner ear. J Neurosci. 2007;27:8940–51. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2085-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Housley GD, Ashmore JF. Ionic currents of outer hair cells isolated from the guinea-pig cochlea. J Physiol (Lond) 1992;448:73–98. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Housley GD, Marcotti W, Navaratnam D, Yamoah EN. Hair cells--beyond the transducer. J Membr Biol. 2006;209:89–118. doi: 10.1007/s00232-005-0835-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishibashi T, Takumida M, Akagi N, Hirakawa K, Anniko M. Expression of transient receptor potential vanilloid (TRPV) 1, 2, 3, and 4 in mouse inner ear. Acta Otolaryngol. 2008;128:1286–1293. doi: 10.1080/00016480801938958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jagger DJ, Ashmore JF. The fast activating potassium current, I(K,f), in guinea-pig inner hair cells is regulated by protein kinase A. Pflugers Arch. 1999a;427:368–371. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(99)00128-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jagger DJ, Ashmore JF. Regulation of ionic currents by protein kinase A and intracellular calcium in outer hair cells isolated from the guinea-pig cochlea. Pflugers Arch. 1999b;437:409–416. doi: 10.1007/s004240050795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakehata S, Santos-Sacchi J. Membrane tension directly shifts voltage dependence of outer hair cell motility and associated gating charge. Biophys J. 1995;68:2190–7. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(95)80401-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kharkovets T, Hardelin JP, Safieddine S, Schweizer M, El-Amraoui A, Petit C, Jentsch TJ. KCNQ4, a K+ channel mutated in a form of dominant deafness, is expressed in the inner ear and the central auditory pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:4333–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.8.4333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kharkovets T, Dedek K, Maier H, Schweizer M, Khimich D, Nouvian R, Vardanyan V, Leuwer R, Moser T, Jentsch TJ. Mice with altered KCNQ4 K+ channels implicate sensory outer hair cells in human progressive deafness. Embo J. 2006;25:642–52. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberman MC, Gao J, He DZ, Wu X, Jia S, Zuo J. Prestin is required for electromotility of the outer hair cell and for the cochlear amplifier. Nature. 2002;419:300–4. doi: 10.1038/nature01059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mammano F, Ashmore JF. Differential expression of outer hair cell potassium currents in the isolated cochlea of the guinea-pig. J Physiol. 1996;496 (Pt 3):639–46. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mammano F, Kros CJ, Ashmore JF. Patch clamped responses from outer hair cells in the intact adult organ of Corti. Pflugers Arch. 1995;430:745–50. doi: 10.1007/BF00386170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcotti W, Russo G, Prigioni I. Inactivating and non-activating delayed rectifier K+ currents in hair cells of frog crista ampullaris. Hear Res. 1999;135:113–23. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(99)00097-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjea D, Jajoo S, Whitworth D, Bunch JR, Turner JG, Rybak LP, Ramkumar V. Short interfering RNA against transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 attenuates cisplatin-induced hearing loss in the rat. J Neurosci. 2008;28:13056–13065. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1307-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver D, He DZ, Klocker N, Ludwig J, Schulte U, Waldegger S, Ruppersberg JP, Dallos P, Fakler B. Intracellular anions as the voltage sensor of prestin, the outer hair cell motor protein. Science. 2001;292:2340–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1060939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rennie KJ, Weng T, Correia MJ. Effects of KCNQ channel blockers on K(+) currents in vestibular hair cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2001;280:C473–80. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2001.280.3.C473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rybalchenko V, Santos-Sacchi J. Cl- flux through a non-selective, stretch-sensitive conductance influences the outer hair cell motor of the guinea-pig. J Physiol. 2003;547:873–91. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.036434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos-Sacchi J. Reversible inhibition of voltage-dependent outer hair cell motility and capacitance. J Neurosci. 1991;11:3096–3110. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-10-03096.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos-Sacchi J. New tunes from Corti’s organ: the outer hair cell boogie rules. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2003;13:459–68. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(03)00100-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos-Sacchi J, Dilger JP. Whole cell currents and mechanical responses of isolated outer hair cells. Hear Res. 1988;35:143–50. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(88)90113-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos-Sacchi J, Huang GJ, Wu M. Mapping the distribution of outer hair cell voltage-dependent conductances by electrical amputation. Biophys J. 1997;73:1424–9. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78174-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos-Sacchi J, Kakehata S, Takahashi S. Effects of membrane potential on the voltage dependence of motility-related charge in outer hair cells of the guinea-pig. J Physiol. 1998;510 (Pt 1):225–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.225bz.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos-Sacchi J, Song L, Zheng J, Nuttall AL. Control of mammalian cochlear amplification by chloride Anions. J Neurosci. 2006;26:3992–3998. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4548-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song L, Seeger A, Santos-Sacchi J. On membrane motor activity and chloride flux in the outer hair cell: lessons learned from the environmental toxin tributyltin. Biophys J. 2005;88:2350–62. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.053579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szallasi A, Blumberg PM. Vanilloid (Capsaicin) receptors and mechanisms. Pharmacol Rev. 1999;51:159–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu T, Lv P, Kim HJ, Yamoah EN, Nuttall AL. Effect of salicylate on KCNQ4 of the guinea pig outer hair cell. J Neurophysiol. 2010;103:1969–1977. doi: 10.1152/jn.01057.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu T, Nie L, Zhang Y, Mo J, Feng W, Wei D, Petrov E, Calisto LE, Kachar B, Beisel KW, Vazquez AE, Yamoah EN. Roles of alternative splicing in the functional properties of inner ear-specific KCNQ4 channels. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:23899–23909. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702108200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng J, Dai C, Steyger PS, Kim Y, Vass Z, Ren T, Nuttall AL. Vanilloid receptors in hearing: altered cochlear sensitivity by vanilloids and expression of TRPV1 in the organ of corti. J Neurophysiol. 2003;90:444–55. doi: 10.1152/jn.00919.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]