Abstract

Human beings have an unusual proclivity for altruistic behavior, and recent commentators have suggested that these prosocial tendencies arise from our unique capacity to understand the minds of others (i.e., to mentalize). The current studies test this hypothesis by examining the relation between altruistic behavior and the reflexive engagement of a neural system reliably associated with mentalizing. Results indicated that activity in the dorsomedial prefrontal cortex—a region consistently involved in understanding others' mental states—predicts both monetary donations to others and time spent helping others. These findings address long-standing questions about the proximate source of human altruism by suggesting that prosocial behavior results, in part, from our broader tendency for social-cognitive thought.

Introduction

One of psychology's most contentious questions is what drives human altruism, with some contending that true altruism—prosocial behavior absent any apparent personal reward—does not exist. Two main positions regarding the proximate bases of prosocial behavior have emerged. Following standard models of behavior from economics and evolutionary biology, many assume that humans act prosocially only to benefit the self; that is, by avoiding social reproach, protecting one's reputation, or ameliorating distress in response to others' suffering (for review, see Dovidio, 1984). In contrast, others argue that altruism does not solely reflect egoistic concerns but may also emanate from an inherently other-regarding source: namely, a consideration of others' subjective experiences. As argued most explicitly by Batson (1991), humans have a remarkable capacity to represent others' thoughts, feelings, and desires, and this capacity can motivate altruistic behavior (de Waal, 2008; Fletcher and Doebeli, 2009). Indeed, at a minimum, altruistic acts involve recognition and appreciation of others' thoughts, feelings, and desires.

Neuroimaging can provide positive evidence to support the hypothesis that altruism derives—at least in part—from the tendency to consider others' mental states. One of the most consistent discoveries in cognitive neuroscience is that this capacity to mentalize draws on a discrete network of brain regions, comprising the medial prefrontal cortex (MPFC), posterior aspects of the superior temporal sulcus at the temporoparietal junction (TPJ), and the precuneus/posterior cingulate (PC) (Van Overwalle and Baetens, 2009). This network is engaged by numerous tasks that involve mentalizing, including reasoning about others' mental states, attributing intentions to objects, and out-guessing others in competitive games (for review, see Gallagher and Frith, 2003; Amodio and Frith, 2006; Mitchell, 2009). If altruistic behavior is indeed supported by an appreciation of others' mental states, then these regions should play an important role in decisions to act altruistically.

Here, we test this hypothesis by examining the degree to which the reflexive engagement of brain areas associated with mentalizing predicts altruistic behavior. In two studies, participants were scanned while making judgments about other people's mental states and later had an opportunity to act altruistically toward those individuals (either by allocating money or time to help these others). In this way, we assessed whether individual differences in reflexive mentalizing predicted later altruistic behavior. Study 2 also tested this prediction for more proximal altruistic behavior, examining whether the extent of mentalizing immediately preceding opportunities to allocate money likewise predicted prosociality. To the extent that the reflexive deployment of social cognition provides a critical foundation for altruistic behavior, we expected that participants who most naturally activate neural regions associated with social-cognitive processing when considering another person should also behave most altruistically.

Materials and Methods

Study 1.

Participants (9 female, 7 male, mean age = 21.10 years) were introduced to two unfamiliar Caucasian male individuals by reading biographical information and viewing a photograph of each. The targets had different personalities, such that one target held conservative social and political views, whereas the other target held more liberal views (these differences did not affect neural correlates of altruism, and analyses from Study 1 collapse across this factor). Participants were told that these two individuals would simultaneously be scanned at other universities while performing the same tasks; in fact, these two individuals did not exist. Participants were then scanned while completing a social judgment task in which they answered questions about the opinions of these two targets and of themselves (Mitchell et al., 2006). On each trial, participants were cued with a photograph of one of the two targets or an outline of a head representing the self. The cue appeared above a question that probed various attitudes that were positive, negative, or neutral, such as “have a positive outlook on life,” “like to gossip,” or “enjoy snowboarding.” Participants judged on a 4-point scale how likely the target would be to hold each attitude. Self-judgment trials were included to support the cover story that all participants would be evaluating each other, but were not included in the analysis. Trials (n = 180) were separated into three runs of functional imaging (TR = 2000 ms; TE = 35 ms; 3.75 × 3.75 in-plane resolution; 31 axial slices, 5 mm thick; 1 mm skip); one participant completed only two runs of this task. To optimize estimation of the event-related fMRI response, trials were intermixed in a pseudorandom order and separated by a variable interstimulus interval (2–6 s) (Dale, 1999) during which participants passively viewed a fixation crosshair.

After scanning, participants' willingness to act altruistically was measured through a monetary distribution task, during which they made a series of choices about how to allocate money among the targets and themselves. On each of 60 trials (order randomized), participants saw two different amounts of money (e.g., $0.10 and $0.15) and were asked to decide which of two individuals would receive the larger amount. On 40 trials, participants allocated money between self and one of the two targets, thereby providing an opportunity to act either altruistically (by allocating the smaller amount to themselves) or selfishly (by allocating the smaller amount to the other person). On an additional 20 trials, participants allocated money between the two targets, keeping with the cover story that all participants would engage in all permutations of decisions in each task (these 20 trials are included in analyses below, but excluding them produces the same pattern of findings). Participants believed their decisions would be implemented at the end of the experiment, and could allocate a maximum of $19 to the targets by consistently acting altruistically and a minimum of $13 by consistently acting selfishly. The amount of money allocated to the other targets over all trials constituted our measure of altruism in Study 1.

Study 2.

Upon arriving at the imaging center, participants (11 male, 4 female, mean age = 24.00 years) were introduced to a Caucasian male confederate, whom they were led to believe was another participant. Through an ostensibly random (but actually fixed) procedure, participants were assigned to undergo scanning while the confederate completed other, unrelated tasks. During scanning, participants completed a similar social judgment task as in Study 1, with three exceptions: (1) they judged the attitudes and opinions of the one other participant (i.e., confederate), (2) they did not make judgments of themselves, and (3) a total of 120 trials were presented across two functional runs.

Following this task, participants' altruistic behavior was measured in two different ways. Before exiting the scanner, participants completed a modified version of the monetary distribution task used in Study 1 (Zaki and Mitchell, 2011). This task comprised 210 trials presented across three functional MRI runs. Following a jittered interstimulus interval (1–6 s), participants were presented with two options (each trial's offer phase). On each trial, participants saw two different amounts of money (e.g., $1.00 and $1.50), each one above a photograph of the participant or of the confederate (taken immediately before the start of the experiment); for example, the participant might be offered a choice between $1.00 for oneself versus $1.50 for the confederate. On each trial, the participant chose between the confederate receiving the amount above his photograph versus personally receiving the amount above his or her photograph. This task differed from the task used in Study 1 in that participants allocated only one amount to one person rather than determining which person received a larger monetary amount and which person received a smaller amount. Importantly, an equivalent number of trials included a larger potential gain for the participant versus a larger potential gain for the confederate. The monetary amounts remained on the screen for a jittered interval (1.5–5.0 s) before participants were asked to indicate their choice. To designate the period during which participants were to indicate their choice, the word “Decide” appeared on the screen, after which participants were given 2 s to choose between the options (each trial's decision phase). The participant's choice then appeared as a red box surrounding the chosen option, which was displayed on the screen for the remainder of the choice period.

This task operationalized altruism in two ways. First, the total amount allocated to the other target over all trials served as a distal measure of altruism, akin to the one used in Study 1. Second, to assess more proximal altruism, we focused on the specific set of choice trials in which the confederate stood more to gain than the participant. In such trials, three participants acted altruistically on 0% of trials, and their data were removed from subsequent stages of this analysis. The remaining 12 subjects (8 male, mean age = 22.10 years) acted altruistically during an average of 44.2% of such trials. These decision types allowed us to assess altruism at a more proximal level by comparing brain activity immediately preceding altruistic decisions to brain activity immediately preceding selfish decisions (see fMRI analysis, below).

In addition, we included a second measure of altruistic behavior that indexed participants' willingness to help another person distinct from donating money (Bartlett and DeSteno, 2006). After exiting the scanner, participants were told that while they were being scanned, the other participant had been working on difficult problem-solving questions and that they could reduce this other person's workload by completing some of the questions for him. Participants were given a set of 50 LSAT questions and told that they could complete as few or as many as they wished. The amount of time spent working on these problems “for the other participant” served as a second measure of altruism. Participants were given a maximum of 45 min to work (three participants reached this maximum).

fMRI analysis.

fMRI data were preprocessed and analyzed using SPM (Wellcome Department of Cognitive Neurology, London, UK). Functional data were slice-time-corrected, motion-corrected, transformed into a standard anatomical space (3 mm isotropic voxels; MNI), and then spatially smoothed using an 8 mm full-width-at-half-maximum Gaussian kernel. Preprocessed images were analyzed using the general linear model (GLM), in which trials were modeled using a canonical hemodynamic response function, its temporal derivative, and additional covariates of no interest (a session mean and a linear trend). For Studies 1 and 2, random-effects analyses were conducted to identify voxels in which BOLD response during the mentalizing task significantly correlated with generosity across participants.

In Study 2, we used an additional analytic strategy to identify clusters of brain activity that immediately preceded altruistic decision-making. We estimated a GLM in which brain activity at the offer phase of the monetary distribution task was split based on later behavior during the decision phase of that trial. We then implemented a whole-brain contrast comparing activity preceding altruistic, as opposed to selfish, choices. In other words, this analysis isolated voxels in which activity was higher during the offer phase of trials that resulted in altruistic, as opposed to selfish, behavior during those same trials' decision phase.

For all analyses, significant voxels were identified using a statistical criterion of p < 0.01; clusters were required to exceed 85 voxels in extent, establishing an experiment-wide statistical threshold of p < 0.05, corrected for multiple comparisons per Slotnick and Schacter's (2004) specifications (https://www2.bc.edu/∼slotnics/scripts.htm). Subsequently, whole-brain statistical images were entered into a conjunction analysis using xjView statistical software. The intersection of suprathreshold voxels common to three measures of distal generosity (monetary donation in Studies 1 and 2, helping in Study 2) yielded a composite map that identified voxels that significantly correlated with generosity for each and all tasks. Despite colinearities in the donation and helping measures during Study 2, the alpha level of this conjunction was no greater than p < 0.02, corrected.

Finally, to calculate an unbiased estimate of the size of the relation between neural response and altruism, we examined an independent region of dorsal MPFC obtained from a standard false belief task (Saxe and Kanwisher, 2003), a well established localizer of mentalizing. An independent group of participants (6 female, 8 male; mean age = 19.80 years) in a separate scanning session read 12 stories that referred to a person's false belief (mental trials) and 12 stories that referred to outdated physical representations such as an old photograph (physical trials). Regions-of-interest were identified from the whole-brain, random-effects contrast of mental > physical. We then extracted parameter estimates associated with trials during the social judgment task in both Study 1 and Study 2, averaged across all voxels identified by the random-effects contrast. Correlation analyses subsequently determined the association between these parameter estimates and the amount of money donated on a subject-by-subject basis.

Results

Study 1

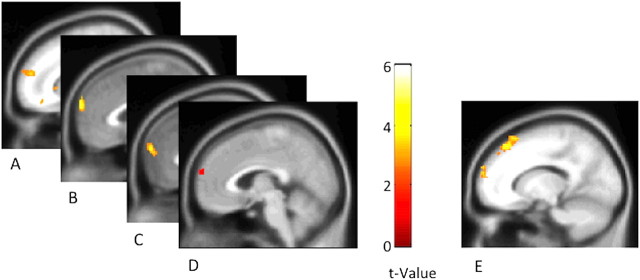

The primary analysis consisted of identifying brain regions in which BOLD response during social judgments significantly predicted subsequent generosity. We refer to this analysis as the distal analysis, as it determines how brain activation predicts distal prosocial behavior. Overall, participants donated an average of $14.10 (SD, $1.10; range, $13.00–$15.95) to the other individuals. Critically, the amount of money that a participant donated was reliably predicted by neural response during the earlier social judgment task (which occurred 20–30 min prior). A random-effects, whole-brain regression analysis identified a sizeable region of the dorsal MPFC that extended laterally (253 voxels, peak MNI coordinate: x/y/z = 26/64/24), in which greater BOLD response when thinking about others was associated with later allocating more money to those individuals (Fig. 1A; for additional regions, see Table 1). In other words, those participants who most robustly engaged the dorsal MPFC when considering the two targets were also those participants who later donated the most money to those individuals.

Figure 1.

A–C, BOLD response when judging other people correlated with money allocated to other participants in Study 1 (depicted at x = 13; A), money allocated to the other participant in Study 2 (depicted at x = 1; B), time spent helping the other participant in Study 2 (depicted at x = 0; C). D, These correlations were consistently identified in the same region of dorsal MPFC, as displayed in an exclusive conjunction of all three distal analyses (the conjunction of images in A–C; depicted at x = 4). E, BOLD response in a similar region of dorsal MPFC was also observed during more proximal choices to act altruistically, as revealed by the contrast of altruistic > selfish choices in Study 2 (depicted at x = −14).

Table 1.

Brain regions in which BOLD response consistently correlated with measures of distal generosity

| Region | x | y | z | Voxels | Cross-study correlations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study 1: Giving | |||||

| Dorsal MPFC/superior frontal gyrus | 26 | 64 | 24 | 253 | 0.32, 0.41 |

| 10 | 58 | 20 | |||

| 24 | 50 | 16 | |||

| 18 | 62 | 24 | |||

| Subgenual anterior cingulate/orbitofrontal cortex | 0 | 30 | −6 | 298 | 0.27, 0.32 |

| 2 | 38 | −12 | |||

| 0 | 46 | −4 | |||

| Parietal cortex | −46 | −68 | 48 | 1041 | 0.31, 0.03 |

| −14 | −86 | 40 | |||

| −18 | −66 | 22 | |||

| −32 | −82 | 44 | |||

| −6 | −64 | 38 | |||

| −10 | −52 | 34 | |||

| −24 | −56 | 10 | |||

| −12 | −48 | 42 | |||

| −12 | −74 | 36 | |||

| −30 | −76 | 36 | |||

| −6 | −66 | 22 | |||

| −22 | −68 | 14 | |||

| Study 2: Giving | |||||

| Dorsal MPFC | 0 | 66 | 22 | 129 | 0.40 |

| 0 | 64 | 32 | |||

| Middle frontal gyrus | −24 | 44 | 12 | 115 | 0.43 |

| −34 | 50 | 14 | |||

| Inferior temporal gyrus | −54 | −20 | −12 | 122 | 0.35 |

| −64 | −22 | −6 | |||

| Tail of caudate | 24 | −34 | 22 | 86 | 0.37 |

| 28 | −42 | 18 | |||

| Occipital cortex | −18 | −82 | 32 | 360 | 0.41 |

| −30 | −84 | 18 | |||

| −16 | −84 | 20 | |||

| Study 2: Helping | |||||

| Dorsal MPFC | 2 | 64 | 20 | 106 | 0.43 |

Note: Columns display peak voxels (followed by any additional local maxima) of regions obtained from random-effects, whole-brain regression analyses that identify regions in which BOLD response was significantly correlated with measures of generosity in the distal analysis (p < 0.01, corrected). Regions listed are those that produced moderate correlations (r > 0.30) with measures of distal generosity across studies. These cross-study correlations refer to the correlation between average BOLD response over all the voxels of the specified region and generosity measures from the alternate study. Thus, for Study 1, the rightmost column displays the correlation between BOLD response and amount of money (first value) and time (second value) donated to the target in Study 2. Similarly, for Study 2, the rightmost column displays the correlation between BOLD response and amount of money donated in Study 1. Coordinates refer to the stereotaxic space of the Montreal Neurological Institute.

Study 2

A similar correlation emerged between activity in dorsal MPFC and generosity as indexed both as amount of money allocated and time spent helping. Overall, participants donated an average of $62.02 (SD, $50.53; range, $0–$139.32) and spent an average of 23.5 min (SD, 18.3 min; range, 1–45 min) helping the other person. These two behavioral measures were significantly correlated (r(13) = 0.65, p < 0.01). Replicating Study 1, monetary donations were again predicted by dorsal MPFC response: random-effects, whole-brain regression analysis identified a region of dorsal MPFC (129 voxels, peak MNI coordinate x/y/z = 0/66/22) in which greater BOLD response when judging the other participant was associated with allocating more money to him (Fig. 1B, Table 1). In addition, activity in a similar region of dorsal MPFC (106 voxels, peak MNI coordinate x/y/z = 2/64/20) correlated with time spent helping (Fig. 1C). In other words, those participants who most robustly engaged the dorsal MPFC when thinking about another person were also those participants who later acted most generously toward that person by donating money and spending time to help him. Dorsal MPFC was the most robust and consistent region to emerge across all analyses.

Given that other regions emerged as predictive of generosity across studies and given that the peak coordinate of the dorsal MPFC varied across analyses, we computed a conjunction image to determine the location of activation common to all analyses (for conjunction image of distal analyses across Studies 1 and 2, see Fig. 1D). Again, a region located squarely in the dorsal MPFC emerged, suggesting that despite variation in the precise location across studies, this region was consistent across studies and analyses in predicting altruistic behavior.

Using a separate analytic strategy, we divided monetary choice trials based on whether participants behaved selfishly or altruistically. We then contrasted brain activity immediately preceding altruistic, as opposed to selfish, behavior. We refer to this as the proximal analysis, in that it isolated brain activity predicting immediate altruistic behavior. Consistent with the other analyses, activity in a region of the dorsal MPFC (338 voxels, peak MNI coordinate x/y/z = 22/64/14) predicted altruistic behavior operationalized in this more proximate way (Fig. 1E).

We also examined a region of dorsal MPFC defined from the mentalizing localizer, in which participants alternately read stories about false beliefs (mental trials) and looked at outdated physical representations (physical trials). The contrast of mental > physical trials revealed nine regions of interest, including an extensive region of dorsal MPFC (3170 voxels; peak MNI coordinate x/y/z = 8/62/26). We examined whether activity in each of these regions was significantly correlated with generosity across participants, in the same manner as the distal analyses. That is, for all participants across Studies 1 and 2, we assessed whether activation—elicited by mentalizing about others—in the regions identified by the false belief task correlated with generosity. We computed a common index of generosity across both studies for each participant by dividing the money allocated during the monetary decision task by the total amount it was possible for the participant to allocate.

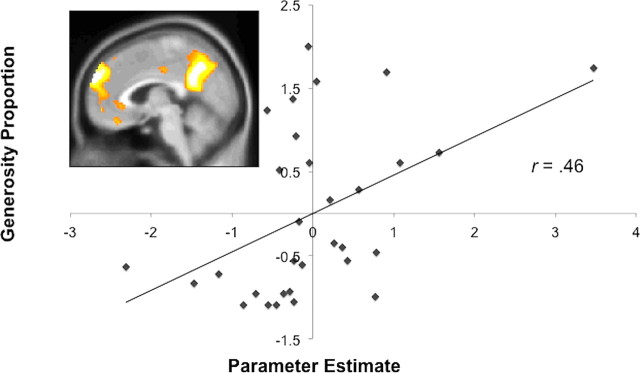

Consistent with the whole-brain analyses reported above, altruism was significantly correlated with the response of the independently defined dorsal MPFC region (r(29) = 0.46, p < 0.01; Fig. 2). When excluding one participant whose dorsal MPFC activity parameter estimate was greater than 3 SD beyond the mean, the correlation remained marginally significant (r(28) = 0.35, p < 0.06). A marginally significant correlation also emerged between generosity and activation in the PC (r(29) = 0.34, p = 0.06), but not in other regions identified by this (all ps > 0.15).

Figure 2.

A region of dorsal MPFC (depicted at x = 4) was defined from an independent sample of participants who alternately read stories about mental states and physical representations. The contrast of mental > physical trials revealed an extensive region of dorsal MPFC. The response in these voxels when judging other people correlated significantly with money that participants allocated to others across both studies. The scatterplot displays the correlation between response of this dorsal MPFC region (in standardized arbitrary units; x-axis) and generosity (standardized proportion of money donated; y-axis), r(29) = 0.46, p < 0.01 (Study 1: r(14) = 0.53, p < 0.05; Study 2: r(13) = 0.34, p = 0.22).

Discussion

The present studies demonstrate that individual differences in the reflexive engagement of a brain region consistently implicated in social cognition—the dorsal MPFC—predict altruistic behavior. Across two studies and multiple measures of altruism, we found that the response of dorsal MPFC predicted subsequent altruistic behavior toward others. Participants demonstrating the highest MPFC response during a social judgment task were also those who later donated the most money to others (Studies 1 and 2) and who later devoted the most time to help another person (Study 2). Moreover, MPFC response predicted participants' altruistic behavior both a few seconds later (Study 2) and at relatively long temporal delays of 20–30 min (Studies 1 and 2).

As such, these studies provide empirical support for recent suggestions that human altruism derives from our readiness to understand others in terms of their internal thoughts, feelings, and desires. Some perceivers appeared particularly inclined to deploy such social-cognitive processing when considering others, and these individuals also acted most altruistically by donating money or time to help another person. Of course, the current data cannot adjudicate whether this relation reflects stable individual differences across participants—such that perceivers consistently differ in their engagement in social-cognitive processing—or more context-specific factors, such as how much a participant happened to like the targets, how much time or money a participant had to give on that particular day, or whether the participant was simply in a misanthropic mood. However, regardless of the source of the variability across participants, these results support the notion that the consideration of others' mental states represents an important contributor to altruistic behavior.

Of course, MPFC activation has been implicated in a number of cognitive processes other than thinking about the mind of others (for review, see Mitchell, 2009), and such many-to-one mappings of psychological function to neuroanatomical structure require careful interpretation to avoid the pitfalls of reverse inference (Poldrack, 2006). However, the problems associated with reverse inference are mitigated by experimental contexts that strongly isolate the cognitive process in question. Here, the interpretation of MPFC activation as an index of social cognition is supported both by the inherently social nature of the judgment task (that asked participants to consider the opinions and attitudes of others), as well as by the use of a well characterized functional localizer that has been used repeatedly to identify regions specific for mentalizing (Saxe and Kanwisher, 2003). In addition, the extensive literature supporting a role for the MPFC in social cognition and our strong a priori predictions of the role of this region in predicting altruistic behavior support the interpretation of MPFC response as an index of processes strongly related to social cognition. However, as for all scientific findings, these conclusions will benefit from experimental verification.

Interestingly, the dorsal MPFC emerged as the most reliable predictor of altruistic behavior, but our analyses suggest that other regions might also contribute to this behavior as well. Specifically, the analysis using the mentalizing localizer revealed that, in addition to MPFC, PC showed a marginally significant relation with giving. This may be unsurprising given that the PC is often active during mentalizing, is a key region of the default network, and may be functionally coupled to the MPFC (Andrews-Hanna et al., 2010). Moreover, failure to find more consistent effects of the PC or TPJ is consistent with previous findings suggesting the central role of the MPFC in mentalizing (Gallagher and Frith, 2003) and ancillary roles for the PC (Mar, 2011) and TPJ (Decety and Lamm, 2007; Mitchell, 2008). Table 1 also displays additional regions that predict generosity across studies and measures. For example, the response of orbitofrontal cortex also correlated with levels of altruistic behavior, consistent with other work demonstrating a role for this region in charitable giving (Moll et al., 2006). However, as also evidenced in Table 1, no region predicted generosity with the same consistency or with the same strength as the dorsal MPFC, and it is for this reason that the present research focuses primarily on this region. Future work should more conclusively address other regions' roles in supporting altruistic behavior.

The current studies follow several recent demonstrations of a relation between empathy and the dorsal MPFC. For example, individual differences in self-reported empathy correlate with dorsal MPFC activation when passively viewing photos of people (Wagner et al., 2011) and dorsal MPFC activation predicts accuracy in judging others' mental states (Zaki et al., 2009). Other studies have reported correlations between brain regions involved in social cognition and self-reported altruism and willingness to help (Tankersley et al., 2007; Mathur et al., 2010), although no measures of real-time altruistic behavior were included in this earlier research. In addition, other research has demonstrated MPFC activation when participants make costly donations to family members (Telzer et al., 2011) or that such activation predicts comforting behavior to someone who was excluded socially (Masten et al., 2011). The current studies extend these results by suggesting that the relation between social cognition and prosociality does not depend on first provoking strongly empathic responses by presenting an emotionally evocative event or individual such as a family member. In this way, our findings suggest that it is not empathic concern per se that increases prosociality, but rather the natural tendency to consider others' mental states even in relatively neutral contexts.

Footnotes

This work was supported by a grant from the Templeton Foundation for Positive Neuroscience. A.W. was supported by a National Research Service Award from the National Institutes of Health. We thank T. J. Eisenstein, E. Jolly, B. McShane, J. Schirmer, D. Johnson, J. M. Contreras, and K. Parreno for assistance.

The authors declare no financial conflicts of interest.

References

- Amodio DM, Frith CD. Meeting of minds: the medial frontal cortex and social cognition. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7:268–277. doi: 10.1038/nrn1884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews-Hanna JR, Reidler JS, Sepulcre J, Poulin R, Buckner RL. Functional-anatomic fractionation of the brain's default network. Neuron. 2010;65:550–562. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett MY, DeSteno D. Gratitude and prosocial behavior. Psychol Sci. 2006;17:319–325. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01705.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batson CD. The altruism question: toward a social-psychological answer. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Dale AM. Optimal experimental design for event-related fMRI. Hum Brain Mapp. 1999;8:109–114. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0193(1999)8:2/3<109::AID-HBM7>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decety J, Lamm C. The role of the right temporoparietal junction in social interaction: how low-level computational processes contribute to meta-cognition. Neuroscientist. 2007;13:580–593. doi: 10.1177/1073858407304654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Waal FB. Putting the altruism back into altruism: the evolution of empathy. Annu Rev Psychol. 2008;59:279–300. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.59.103006.093625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dovidio JF. Helping behavior and altruism: an empirical and conceptual overview. In: Berkowitz L, editor. Advances in experimental social psychology. New York: Academic; 1984. pp. 361–427. [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher JA, Doebeli M. A simple and general explanation for the evolution of altruism. Proc Biol Sci. 2009;276:13–19. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2008.0829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher HL, Frith CD. Functional imaging of “theory of mind.”. Trends Cogn Sci. 2003;7:77–83. doi: 10.1016/s1364-6613(02)00025-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mar RA. The neural bases of social cognition and story comprehension. Annu Rev Psychol. 2011;62:103–134. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-120709-145406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masten CL, Morelli SA, Eisenberger NI. An fMRI investigation of empathy for ‘social pain’ and subsequent prosocial behavior. Neuroimage. 2011;55:381–388. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.11.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathur VA, Harada T, Lipke T, Chiao JY. Neural basis of extraordinary empathy and altruistic motivation. Neuroimage. 2010;51:1468–1475. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell JP. Activity in right temporo-parietal junction is not selective for theory-of-mind. Cereb Cortex. 2008;18:262–271. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhm051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell JP. Social psychology as a natural kind. Trends Cogn Sci. 2009;13:246–251. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2009.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell JP, Macrae CN, Banaji MR. Dissociable medial prefrontal contributions to judgments of similar and dissimilar others. Neuron. 2006;50:655–663. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.03.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moll J, Krueger F, Zahn R, Pardini M, de Oliveira-Souza R, Grafman J. Human fronto-mesolimbic networks guide decisions about charitable donation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:15623–15628. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604475103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poldrack RA. Can cognitive processes be inferred from neuroimaging data? Trends Cogn Sci. 2006;10:59–63. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2005.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxe R, Kanwisher N. People thinking about thinking people: the role of the temporo-parietal junction in “theory of mind.”. Neuroimage. 2003;19:1835–1842. doi: 10.1016/s1053-8119(03)00230-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slotnick SD, Schacter DL. A sensory signature that distinguishes true from false memories. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:664–672. doi: 10.1038/nn1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tankersley D, Stowe CJ, Huettel SA. Altruism is associated with an increased neural response to agency. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:150–151. doi: 10.1038/nn1833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Telzer EH, Masten CL, Berkman ET, Lieberman MD, Fuligni AJ. Neural regions associated with self control and mentalizing are recruited during prosocial behaviors towards the family. Neuroimage. 2011;58:242–249. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Overwalle F, Baetens K. Understanding others' actions and goals by mirror and mentalizing systems: a meta-analysis. Neuroimage. 2009;48:564–584. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner DD, Kelley WM, Heatherton TF. Individual differences in the spontaneous recruitment of brain regions supporting mental state understanding when viewing natural social scenes. Cereb Cortex. 2011;21:2788–2796. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhr074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaki J, Mitchell J. Equitable decision making is associated with neural markers of subjective value. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:19761–19766. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1112324108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaki J, Weber J, Bolger N, Ochsner K. The neural basis of empathic accuracy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:11382–11387. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902666106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]