Abstract

Abiotic stress, including drought, salinity, and temperature extremes, regulates gene expression at the transcriptional and posttranscriptional levels. Expression profiling of total messenger RNAs (mRNAs) from rice (Oryza sativa) leaves grown under stress conditions revealed that the transcript levels of photosynthetic genes are reduced more rapidly than others, a phenomenon referred to as stress-induced mRNA decay (SMD). By comparing RNA polymerase II engagement with the steady-state mRNA level, we show here that SMD is a posttranscriptional event. The SMD of photosynthetic genes was further verified by measuring the half-lives of the small subunit of Rubisco (RbcS1) and Chlorophyll a/b-Binding Protein1 (Cab1) mRNAs during stress conditions in the presence of the transcription inhibitor cordycepin. To discern any correlation between SMD and the process of translation, changes in total and polysome-associated mRNA levels after stress were measured. Total and polysome-associated mRNA levels of two photosynthetic (RbcS1 and Cab1) and two stress-inducible (Dehydration Stress-Inducible Protein1 and Salt-Induced Protein) genes were found to be markedly similar. This demonstrated the importance of polysome association for transcript stability under stress conditions. Microarray experiments performed on total and polysomal mRNAs indicate that approximately half of all mRNAs that undergo SMD remain polysome associated during stress treatments. To delineate the functional determinant(s) of mRNAs responsible for SMD, the RbcS1 and Cab1 transcripts were dissected into several components. The expressions of different combinations of the mRNA components were analyzed under stress conditions, revealing that both 3′ and 5′ untranslated regions are necessary for SMD. Our results, therefore, suggest that the posttranscriptional control of photosynthetic mRNA decay under stress conditions requires both 3′ and 5′ untranslated regions and correlates with differential polysome association.

In response to certain environmental stimuli, such as dehydration, high salinity, and low temperature, genes undergo various changes in expression as part of the stress tolerance response of plants. Plants, at once sessile and developmentally indeterminate, are unique in that each gene expression change must account for both long-range genetically determined programs and short-term environmental responses. As such, plants use a number of regulatory mechanisms to achieve appropriate gene expression, including the control of RNA stability (Bailey-Serres et al., 2009; Belostotsky and Sieburth, 2009).

The RNA regulatory elements that control transcript stability can reside anywhere along its sequence. Stability elements have been reported to occur within the 5′ untranslated region (UTR) of several transcripts of nucleus-encoded chloroplast proteins. The pea (Pisum sativum) and Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) Ferredoxin-1 (Fed-1) mRNAs, which stabilize upon the excitation of phytochrome, are the best characterized examples of mRNAs with 5′ UTR stability elements (Chiba and Green, 2009). Phytochrome-mediated stabilization of Fed-1 mRNA requires active translation, the 5′ UTR, and active photosynthetic electron transport (Chiba and Green, 2009). Light-mediated increases in transcript stability have also been reported for small subunit of Rubisco (RbcS) transcripts in petunia (Petunia hybrida; Sathish et al., 2007) and the light-harvesting chlorophyll-binding (Lhcb) transcripts in pea (Warpeha et al., 2007).

Unlike stabilization elements, many of the recognized destabilization sequences reside within the 3′ UTR, such as multiple overlapping AUUUA sequences or other AU-rich elements, which have been reported in mammals. Several proto-oncogene, cytokine, and transcription factor mRNAs involved in growth and differentiation are subjected to rapid decay via AU-rich elements (Vasudevan and Peltz, 2001; Bevilacqua et al., 2003; Reznik and Lykke-Andersen, 2010). The best characterized instability sequence in plants is the so-called downstream (DST) element, which has a complex structure and recognition requirements that are unique to plants (Sullivan and Green, 1996; Feldbrügge et al., 2002). The DST instability sequence was originally found within the 3′ UTR of the small auxin up RNA (SAUR) genes and has also been shown to function in tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum; Feldbrügge et al., 2002; Streatfield, 2007). Additional investigations of DST elements in Arabidopsis have revealed that unstable transcripts encoding proteins associated with circadian control possess DST elements in their 3′ UTRs (Gutierrez et al., 2002; Lidder et al., 2005; Streatfield, 2007).

Genome-wide expression profiling is an excellent experimental tool for the analysis of mRNA decay. Using complementary DNA (cDNA) microarray analysis, approximately 325 Arabidopsis transcripts have been found to be unstable, with half-lives of less than 2 h. This rapid transcript decay has been found to be associated with a group of touch- and circadian clock-controlled genes (Gutierrez et al., 2002). When the half-lives of mRNAs from Arabidopsis suspension culture cells were assessed using expression microarrays, the measurements varied from minutes to more than 24 h and revealed two mechanisms that appear to affect differential decay (Narsai et al., 2007). Conserved sequence elements were identified within both the 5′ and 3′ UTRs that correlated with stable and unstable mRNAs, with genes containing introns giving rise to more stable mRNAs than intronless genes.

Accumulating evidence indicates that mRNA decay mechanisms are often coupled to translation in plants (Chiba and Green, 2009) and other organisms (Balagopal and Parker, 2009). With respect to general determinants, the presence of a 5′-m7Gppp cap and a 3′-poly(A) tail, which contribute to mRNA stability, is even more important to ensure efficient translation (Gallie, 1996). Hence, mechanisms that remove these elements would be expected to decrease gene expression at the levels of both mRNA stability and translation. Another observation that links these functions is the stabilizing effect that the protein synthesis inhibitor cycloheximide has on a number of unstable mRNAs (Chiba and Green, 2009). This stabilization could occur because translation of a labile transacting factor, or translation of the mRNA itself, is required for rapid degradation. The role of polyribosomes (polysomes) as sites of mRNA decay is supported by reports that the decay intermediates of SRS4 (small subunit of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase in soybean [Glycine max]) and PHYA (phytochrome A in oat [Avena sativa]) mRNAs are polysome associated (Thompson et al., 1992; Higgs and Colbert, 1994) and that most in vitro decay systems are polysome based (Tanzer and Meagher, 1994; Ross, 1995). In another model system, several mutations of the pea Fed-1 gene that block translational initiation or elongation also abolish the light response of Fed-1, consistent with the model of translation being a requirement for the stabilization of Fed-1 in a light environment (Chiba and Green, 2009).

In addition to the genes that are up-regulated under stress conditions, we have here identified a comparable number of down-regulated genes in rice (Oryza sativa) plants. The latter group includes most of the photosynthetic genes involved in light and dark reactions. The mRNAs of photosynthetic genes degrade rapidly upon exposure to stress conditions, a phenomenon referred to as stress-induced mRNA decay (SMD). Experiments incorporating polysome fractionation followed by microarray analysis revealed that photosynthetic mRNAs remain polysome associated during SMD. Dissection of the photosynthetic mRNAs Rubisco Small Subunit1 (RbcS1) and Chlorophyll a/b-Binding Protein1 (Cab1) in transgenic plants has identified the 3′ UTR as the site of the regulatory mRNA elements that mediate SMD.

RESULTS

SMD of Photosynthetic Genes during Stress Conditions

We have previously identified stress-regulated genes in rice plants through expression profiling using the Rice 3′-Tiling microarray (GreenGene Biotech) and RNAs from the 14-d-old leaves of rice seedlings subjected to drought, high salt, and low temperature (Oh et al., 2009; Jeong et al., 2010). In addition to up-regulated genes, we also identified many genes that were down-regulated under stress conditions, including most of the photosynthetic genes involved in light and dark reactions. For example, mRNA levels of the light reaction genes Cab1, Plastocyanin (PCY), Cab26, OEE1, PSI-D and PSI-K and the dark reaction genes RbcS1, Rubisco Activase (RA), SEDP2ase, GAPDH, TK, and FBPase-P are rapidly reduced in response to both drought and salt stress conditions. In contrast, the mRNA levels of these genes are not reduced by cold stress. These findings were further confirmed by RNA gel-blot and real-time (RT)-PCR analyses (Fig. 1A; Supplemental Fig. S1). Thus, photosynthetic gene mRNAs appear to decay in response to different stressors (i.e. to undergo SMD).

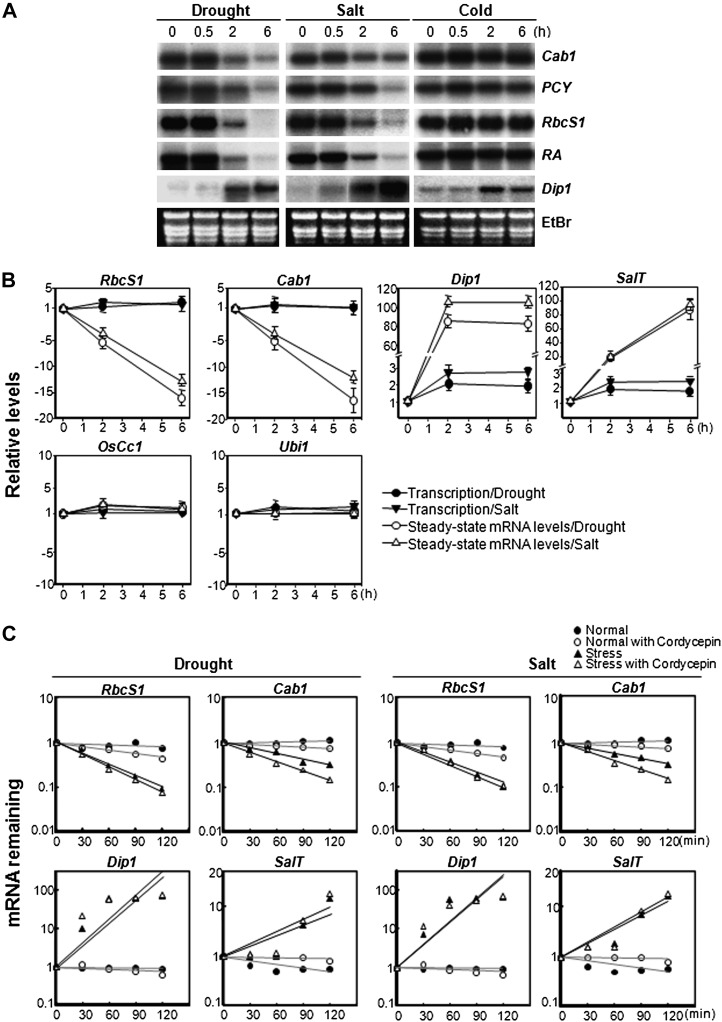

Figure 1.

Changes in steady-state mRNA and transcription activity levels under stress conditions. Total RNA was isolated from the leaf tissue of 2-week-old wild-type seedlings that were subjected to drought, high salinity, and low temperature stress for 0 to 6 h. RNA gel-blot hybridizations were then performed using the probes described in “Materials and Methods.” Dip1 (AY587109) and SalT (AK062520; Claes et al., 1990) served as stress marker genes. A, Total cellular RNA gel-blot analysis. Cab1 (AK060851) and PCY (AK070447) are involved in the light reaction of photosynthesis. RbcS1 (AK121444) and RA (AK119513) genes are involved in the dark reaction. Ethidium bromide (EtBr)-stained rRNAs served as a loading control. B, Transcription (RNA Pol II engagement) and steady-state mRNA levels were measured in leaf tissues exposed to drought and salt stress for the indicated times. Transcription of RbcS1, Cab1, Dip1, SalT, OsCc1 (Jang et al., 2002), and Ubi1 (AK121590; Kim et al., 1994) were measured using a Pol II-ChIP assay (Supplemental Fig. S2). Steady-state mRNA levels were measured by qRT-PCR analysis using cDNA synthesized using total RNAs from stress-treated leaves. Values are means ± sd of three independent q-PCR experiments and are presented relative to the results from unstressed controls with values set at 1. C, Quantification of the decrease in mRNA abundance and transcript half-life estimation. The transcript (RbcS1, Cab1, Dip1, and SalT) levels in nontransgenic plants over a time course after exposure to drought or salt stress in the presence or absence of cordycepin were measured. Those levels under normal growth conditions in the presence or absence of cordycepin were also measured. The signal for EIF-4A (AB046414) did not change significantly during the time course and was used as an internal control to normalize the mRNA levels. The half-life values were calculated as shown in Table I. Steady-state mRNA levels were measured by qRT-PCR analysis as described in B.

To investigate whether SMD occurs at the transcriptional or posttranscriptional level, we measured RNA polymerase II (Pol II) engagement, a proxy for active transcription, and steady-state mRNA levels for three different types of representative genes. These genes included the down-regulated transcripts RbcS1 and Cab1, up-regulated Dehydration Stress-Inducible Protein1 (Dip1) and Salt-Induced Protein (SalT), and also OsCc1 and Ubi1, which remain unperturbed under stress conditions. The transcription and steady-state mRNA levels of the six genes were analyzed using the RNA Pol II-chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay and the quantitative (q)RT-PCR method, respectively (Fig. 1B). Rice leaves treated with 2 and 6 h of drought or salt stress, and untreated control leaves, were used for the Pol II-ChIP and qRT-PCR experiments. The steady-state RbcS1 and Cab1 mRNA levels dropped by 12- to 15-fold, whereas their transcription remained unaltered. In contrast, the steady-state mRNA levels of Dip1 and SalT, both stress-inducible genes, were induced by 80- to 100-fold, whereas the transcription levels in each case were only modestly increased. Neither the steady-state mRNA levels nor the transcription of OsCc1 and Ubi1 was significantly altered under stress conditions, further validating their constitutive expression in seedling leaves.

To confirm the posttranscriptional controls of the down-regulated (RbcS1 and Cab1) and up-regulated (Dip1 and SalT) transcripts during drought and salt stress, their half-lives were measured in the presence of the transcription inhibitor cordycepin (Fig. 1C). Cordycepin treatments were effective in rice in blocking transcription, as evidenced by the reduced half-lives of EXPL2 (AK068088) and SEN1 (AK120910), rice homologs of Arabidopsis genes that produce very unstable mRNAs (Gutierrez et al., 2002; Lidder et al., 2005; Xu and Chua, 2009), under normal growth conditions (Supplemental Fig. S5). The half-lives of the RbcS1 and Cab1 transcripts were 123 and 239 min under normal growth conditions, respectively, whereas they decreased to 44 to 53 min under drought and salt stress conditions (Fig. 1C; Table I). Drought and salt stress caused a stabilization of the Dip1 and SalT transcripts at the posttranscriptional level (Fig. 1C). Similar posttranscriptional stabilization has been observed previously in salt stress-regulated genes such as PEPCase (Cushman et al., 1990), AtP5R (Hua et al., 2001), and SOS1 (Shi et al., 2003; Chung et al., 2008) and in abscisic acid- and water stress-regulated genes such as α-amylase/subtilisin inhibitor (BASI; Liu and Hill, 1995), le25, and his1-s (Cohen et al., 1999). Taken together, our results suggest that the SMD of RbcS1 and Cab1 as well as the control of the stress-inducible Dip1 and SalT genes are posttranscriptional events.

Table I. Half-lives of RbcS1 and Cab1 mRNAs under normal and stress conditions.

| Gene | Half-Life |

Half-Life, Decay and Transcription Combined |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal + Cordycepin | Drought + Cordycepin | Salt + Cordycepin | Drought | Salt | |

| min | |||||

| RbcS1 | 123 | 44 | 51 | 50 | 55 |

| Cab1 | 239 | 50 | 53 | 73 | 77 |

The mRNAs of Photosynthetic Genes Remain Polysome Associated during Stress Conditions

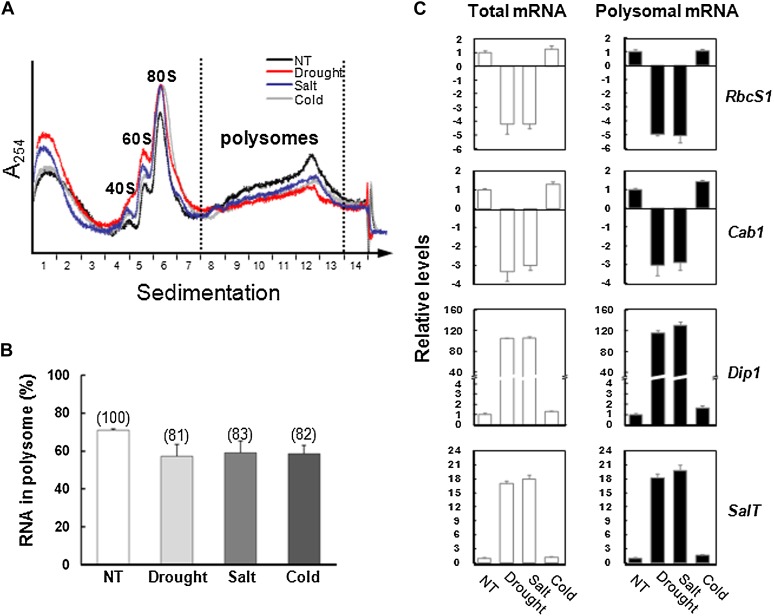

To investigate a possible correlation between SMD and translation, the levels of polysome-associated mRNAs were assessed in 14-d-old leaves after exposure to drought, salt, or cold stress conditions (Supplemental Fig. S3). To obtain polysomes, crude leaf tissue was homogenized in the presence of cycloheximide to attenuate translation elongation. The extracts were then centrifuged through Suc gradients, an absorbance (254 nm) profile was obtained, polysomal fractions (includes two or more ribosomes; fractions 8–13) were collected, and polysome-associated mRNA was extracted (Fig. 2A). Approximately 70% of the total polyadenylated mRNAs (referred to as “total mRNA”) was polysome associated under untreated conditions, but 17% to 19% of the mRNA associated with polysome (referred to as “polysomal mRNA”) became dissociated after exposure to drought, salt, or cold stress conditions (Fig. 2B). To test whether the stress-induced decline in translation affected the photosynthetic mRNA levels, RbcS1 and Cab1 transcripts, together with stress-inducible Dip1 and SalT mRNAs in polysomes, were quantified by qRT-PCR (Fig. 2C). The total mRNA levels were generally consistent with the results for polysomal mRNAs after stress treatment, suggesting that the mRNA polysomal association is important for maintaining stability (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Stress-induced changes in total and polysomal mRNA abundance as determined by qRT-PCR analyses. A, Polysome profiling. Absorbance profiles of rRNA complexes obtained from leaf tissues exposed to drought, salt, and cold stress conditions. NT, No stress treatment. To isolate polysomal components, detergent-treated extracts were subjected to centrifugation through a 1.75 m Suc cushion, followed by fractionation in a 20% to 60% (w/v) Suc gradient (Kawaguchi et al., 2004; Mustroph et al., 2009). B, Polysome mRNA levels decrease under stress conditions. The polysomal RNA content was calculated by integration of the area of the profile containing polysomes divided by the area of the profile containing subunits, monoribosomes, and polysomes (includes two or more ribosomes; fractions 8–13). Values represent means ± sd of three independent biological replicates. C, qRT-PCR analyses were performed using total and polysomal RNA from the leaf tissues of 14-d-old plants exposed to drought, salt, and cold stress for 2 h. Levels of RbcS1, Cab1, Dip1, and SalT mRNAs were assessed. All mRNA levels were normalized to an internal control gene, Ubi1 (AK121590). Values represent means ± sd (n = 3) of the relative levels of transcript accumulation compared with the corresponding nontreated control.

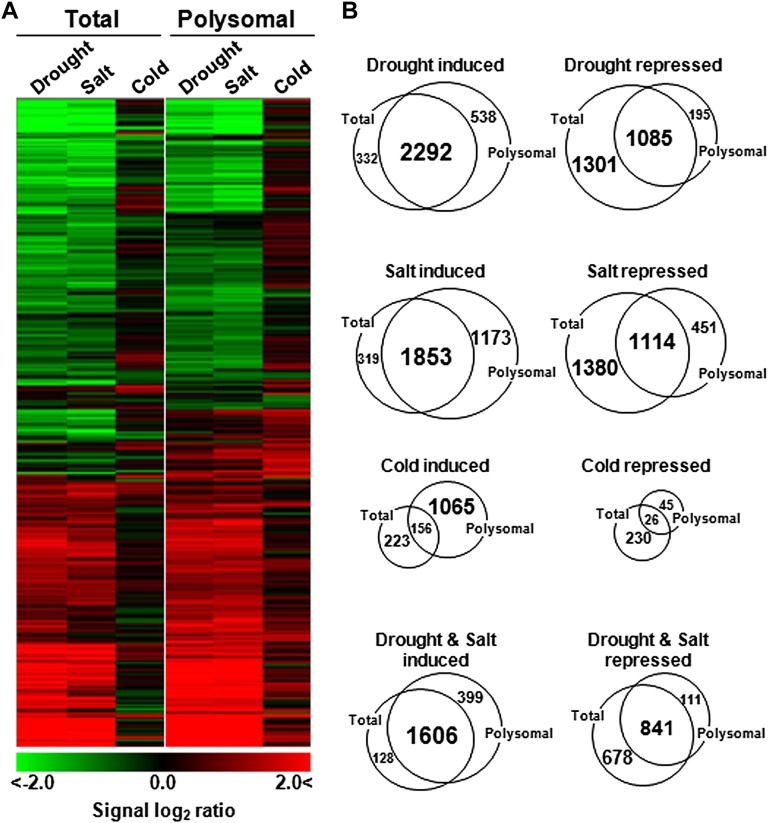

To more broadly evaluate the effects of stress on the mRNA association with polysomes (translation state), we conducted a genome-level analysis of total and polysomal mRNAs using the Rice 3′-Tiling microarray (GreenGene Biotech) that contains probes for 29,389 genes (Fig. 3). A total of 8,129 mRNAs were identified to be significantly up- or down-regulated by stress treatments (2-fold or greater; P < 0.05). The overall patterns of SMD were similar under drought and salt stress but distinct under cold stress (Fig. 3A). More specifically, 42%, 38%, and 9% of mRNAs were both subjected to SMD and polysome associated under drought, salt, and cold stress, respectively (Table II). In contrast, the levels of 8%, 15%, and 15% of mRNAs (Polysomal mRNA in Table II) dropped by more than 2-fold only in polysome fractions, with no change in their total mRNA levels upon treatment with drought, salt, and cold stress, respectively. This indicated the escape of these transcripts from the polysome under stress treatments but no loss of stability. Overall, we found from our analyses that approximately 50% of all of the mRNAs that undergo SMD remain polysome associated (Table II). More importantly, the photosynthetic genes responsible for light and dark reactions were found to be regulated via SMD in a polysome-associated manner under drought and salt but not under cold stress conditions (Table III; Supplemental Fig. S6).

Figure 3.

Hierarchical clustering of total and polysomal mRNA under stress conditions. A, DNA microarray experiments performed with total and polysomal mRNA from leaf tissues treated with drought, salt, and cold stress identified 8,129 of the 29,389 total genes that were up- or down-regulated, respectively, by more than 2-fold (P < 0.05) under at least one stress condition. Values represent means of three independent biological replicates. Green indicates a lower mRNA level, and red indicates a higher mRNA level relative to the nontreated control. B, Changes in total and polysomal mRNA populations after drought, salt, and cold treatments. The gene numbers in the Venn diagrams are the same as those in the microarray data set in A with a significant change in abundance in the total or polysomal mRNA population.

Table II. Changes in total and polysomal mRNA populations after drought, salt, and cold stress.

Percentage and number (in parentheses) of mRNAs were scored from microarray data sets in triplicate determinations to identify significantly increased or decreased transcripts in total or polysomal mRNA populations (2-fold or greater; P < 0.05). Overlap indicates mRNAs with a significant change in both total and polysomal mRNA populations. P values were analyzed using one-way ANOVA.

| Change | Drought |

Salt |

Cold |

Drought and Salt |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total mRNA | Overlap | Polysomal mRNA | Total mRNA | Overlap | Polysomal mRNA | Total mRNA | Overlap | Polysomal mRNA | Total mRNA | Overlap | Polysomal mRNA | |

| % (No.) | ||||||||||||

| Significant increase | 10 (332) | 73 (2,292) | 17 (538) | 10 (319) | 55 (1,853) | 35 (1,173) | 15 (223) | 11 (156) | 74 (1,065) | 6 (128) | 75 (1,606) | 19 (399) |

| Significant decrease | 50 (1,301) | 42 (1,085) | 8 (195) | 47 (1,380) | 38 (1,114) | 15 (451) | 76 (230) | 9 (26) | 15 (45) | 42 (678) | 52 (841) | 6 (111) |

Table III. Microarray data for photosynthetic genes among both total and polysomal mRNAs under drought, salt, and cold stress conditions.

Groups L1 to L7 and D1 to D5 represent genes involved in the light and dark reactions of photosynthesis, respectively (Supplemental Fig S6): L1 (PSII), L2 (plastoquinone), L3 (cytochrome b6f), L4 (plastocyanin), L5 (ferredoxin, ferredoxin-NADP reductase), L6 (PSII), L7 (ATP synthase), D1 (carboxylation of the Calvin cycle), D2 (reduction of the Calvin cycle), D3 (regeneration of the Calvin cycle), D4 (carbon output), and D5 (photorespiratory cycle).

| Group/Gene | Accession No.a | Total mRNA |

Polysomal mRNA |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drought |

Salt |

Cold |

Drought |

Salt |

Cold |

|||||||||

| Meanb | P c | Mean | P | Mean | P | Mean | P | Mean | P | Mean | P | |||

| Light reaction | ||||||||||||||

| L1 | ||||||||||||||

| PSII Cab1 (chlorophyll a/b binding protein) | Os09g0346500 | −1.1 | −2.1 | 0.00 | −2.6 | 0.00 | 1.1 | 0.93 | −2.0 | 0.00 | −2.2 | 0.00 | 1.3 | 0.18 |

| PSII type l Cab E | Os09g0296800 | −1.4 | −2.6 | 0.00 | −3.5 | 0.00 | −1.3 | 0.09 | −2.2 | 0.00 | −2.5 | 0.00 | 1.4 | 0.10 |

| PSII CP26 Lhcb5 | Os11g0242800 | −1.5 | −2.8 | 0.00 | −3.2 | 0.00 | −1.1 | 0.87 | −2.3 | 0.00 | −2.4 | 0.00 | 1.4 | 0.21 |

| PSII Cab type III | Os07g0562700 | −1.1 | −2.1 | 0.00 | −2.3 | 0.00 | −1.1 | 0.87 | −2.0 | 0.00 | −2.1 | 0.00 | 1.4 | 0.08 |

| PSII CP24 | Os04g0457000 | −1.0 | −2.0 | 0.00 | −2.0 | 0.00 | 1.1 | 0.62 | −2.0 | 0.00 | −2.0 | 0.00 | 1.3 | 0.54 |

| Oxygen-evolving complex protein PsbP | Os01g0805300 | −2.4 | −5.3 | 0.00 | −6.5 | 0.00 | −1.4 | 0.15 | −2.7 | 0.00 | −3.4 | 0.00 | 1.1 | 0.66 |

| Oxygen-evolving complex protein PsbP | Os03g0279950 | −1.3 | −2.5 | 0.00 | −3.7 | 0.00 | −1.4 | 0.27 | −2.2 | 0.00 | −2.7 | 0.00 | 1.3 | 0.86 |

| Oxygen-evolving complex protein PsbP | Os12g0564400 | −1.0 | −2.0 | 0.00 | −2.5 | 0.00 | −1.3 | 0.12 | −2.0 | 0.00 | −2.3 | 0.00 | −1.3 | 0.09 |

| PSII subunit PsbX | Os03g0343900 | −1.1 | −2.1 | 0.00 | −2.2 | 0.00 | −1.2 | 0.40 | −2.0 | 0.00 | −2.2 | 0.00 | 1.4 | 0.07 |

| PSII core complex PsbY | Os08g0119800 | −1.2 | −2.3 | 0.00 | −2.6 | 0.00 | 1.3 | 0.33 | −2.1 | 0.00 | −2.2 | 0.00 | 1.0 | 0.88 |

| PSII subunit H | Os04g0238700 | −1.2 | −2.3 | 0.00 | −2.5 | 0.00 | −1.3 | 0.30 | −2.1 | 0.02 | −2.2 | 0.00 | 1.3 | 0.19 |

| L2 | ||||||||||||||

| NAD(P)H-quinone oxidoreductase chain 2 | Os07g0467900 | −1.3 | −2.5 | 0.05 | −3.5 | 0.01 | 1.1 | 0.83 | −2.2 | 0.00 | −2.3 | 0.02 | 1.4 | 0.32 |

| NAD(P)H-quinone oxidoreductase chain 3 | Os04g0309100 | −1.4 | −2.6 | 0.00 | −2.0 | 0.01 | −1.4 | 0.33 | −2.5 | 0.00 | −2.2 | 0.01 | 1.3 | 0.85 |

| L3 | ||||||||||||||

| Cytochrome b6f subunit 7 | Os03g0765900 | −1.2 | −2.3 | 0.00 | −2.6 | 0.00 | 1.0 | 0.99 | −2.0 | 0.00 | −2.3 | 0.00 | 1.1 | 0.48 |

| L4 | ||||||||||||||

| Plastocyanin | Os03g0758500 | −1.1 | −2.1 | 0.00 | −2.0 | 0.00 | 1.4 | 0.13 | −2.1 | 0.00 | −2.1 | 0.00 | 1.3 | 0.46 |

| Plastocyanin | Os01g0281600 | −1.3 | −2.5 | 0.00 | −3.0 | 0.00 | −1.3 | 0.26 | −2.3 | 0.00 | −2.0 | 0.00 | 1.4 | 0.19 |

| Plastocyanin | Os11g0428800 | −1.2 | −2.3 | 0.00 | −2.2 | 0.00 | −1.2 | 0.59 | −2.1 | 0.00 | −2.1 | 0.00 | −1.1 | 0.30 |

| Plastocyanin | Os02g0653200 | −1.0 | −2.0 | 0.00 | −2.0 | 0.00 | 1.1 | 0.84 | −2.1 | 0.00 | −2.3 | 0.00 | 1.3 | 0.85 |

| L5 | ||||||||||||||

| Ferredoxin | Os07g0489800 | −1.6 | −3.0 | 0.00 | −2.6 | 0.00 | 1.0 | 1.00 | −2.8 | 0.00 | −2.6 | 0.00 | −1.3 | 0.06 |

| Ferredoxin I | Os04g0412200 | −1.2 | −2.4 | 0.00 | −2.3 | 0.00 | 1.4 | 0.19 | −2.1 | 0.00 | −2.4 | 0.00 | −1.1 | 0.11 |

| Ferredoxin I | Os05g0555300 | −1.2 | −2.3 | 0.00 | −2.1 | 0.00 | −1.1 | 0.79 | −2.1 | 0.00 | −2.0 | 0.00 | −1.3 | 0.34 |

| Ferredoxin-NADP+ reductase | Os06g0107700 | −1.1 | −2.2 | 0.00 | −2.6 | 0.00 | −1.4 | 0.19 | −2.1 | 0.00 | −2.5 | 0.00 | 1.4 | 0.15 |

| Ferredoxin-NADP+ reductase | Os03g0784700 | −1.2 | −2.3 | 0.00 | −2.4 | 0.00 | −1.4 | 0.33 | −2.3 | 0.00 | −2.3 | 0.00 | 1.4 | 0.12 |

| L6 | ||||||||||||||

| PSI subunit PsaA | Os01g0790950 | −1.4 | −2.6 | 0.00 | −2.3 | 0.00 | −1.1 | 0.79 | −2.3 | 0.00 | −2.2 | 0.00 | 1.4 | 0.10 |

| PSI subunit D | Os08g0560900 | −1.2 | −2.3 | 0.00 | −2.3 | 0.00 | 1.0 | 0.96 | −2.3 | 0.00 | −2.2 | 0.00 | 1.5 | 0.03 |

| PSI subunit X | Os07g0148900 | −1.2 | −2.3 | 0.00 | −2.6 | 0.00 | −1.1 | 0.71 | −2.1 | 0.00 | −2.5 | 0.00 | 1.2 | 0.17 |

| PSI subunit N | Os12g0189400 | −1.1 | −2.2 | 0.00 | −2.4 | 0.00 | 1.0 | 0.90 | −2.0 | 0.00 | −2.2 | 0.00 | 1.2 | 0.10 |

| L7 | ||||||||||||||

| ATP synthase γ-chain | Os07g0513000 | −1.4 | −2.6 | 0.00 | −3.0 | 0.00 | −1.4 | 0.17 | −2.3 | 0.00 | −2.2 | 0.00 | 1.4 | 0.25 |

| Dark reaction | ||||||||||||||

| D1 | ||||||||||||||

| RbcS1 (Rubisco small subunit) | Os12g0274700 | −1.1 | −2.1 | 0.00 | −2.5 | 0.00 | 1.1 | 0.69 | −2.7 | 0.00 | −3.0 | 0.00 | −1.2 | 0.55 |

| RbcS | Os12g0291100 | −1.0 | −2.0 | 0.00 | −2.1 | 0.00 | 1.2 | 0.48 | −2.2 | 0.00 | −2.3 | 0.00 | −1.3 | 0.29 |

| Rubisco activase | Os11g0707000 | −1.1 | −2.2 | 0.00 | −2.2 | 0.00 | −1.1 | 0.54 | −2.1 | 0.00 | −2.3 | 0.00 | 1.2 | 0.44 |

| Rubisco activase | Os04g0658300 | −1.1 | −2.2 | 0.00 | −2.3 | 0.00 | −1.2 | 0.43 | −2.1 | 0.00 | −2.3 | 0.00 | 1.3 | 0.39 |

| Rubisco subunit-binding protein | Os03g0293900 | −1.3 | −2.5 | 0.00 | −2.0 | 0.00 | 1.1 | 0.65 | −2.6 | 0.00 | −2.0 | 0.00 | 1.4 | 0.50 |

| Rubisco subunit-binding protein | Os09g0563300 | −1.0 | −2.0 | 0.00 | −2.0 | 0.00 | 1.1 | 0.43 | −2.1 | 0.00 | −2.0 | 0.00 | 1.0 | 0.30 |

| D2 | ||||||||||||||

| Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase | Os06g0136600 | −1.2 | −2.3 | 0.00 | −2.0 | 0.00 | −1.1 | 0.60 | −2.2 | 0.00 | −2.0 | 0.00 | 1.1 | 0.38 |

| Pyruvate kinase isozyme G | Os10g0571200 | −1.2 | −2.3 | 0.00 | −2.0 | 0.00 | −1.1 | 0.82 | −2.0 | 0.00 | −2.0 | 0.00 | 1.3 | 0.44 |

| D3 | ||||||||||||||

| Triose phosphate isomerase | Os09g0535000 | −1.5 | −2.8 | 0.00 | −2.1 | 0.00 | −1.4 | 0.16 | −2.5 | 0.00 | −2.4 | 0.00 | 1.2 | 0.90 |

| Fru-1,6-bisphosphatase | Os06g0608700 | −1.9 | −3.7 | 0.00 | −3.2 | 0.00 | 1.0 | 0.94 | −3.3 | 0.00 | −2.9 | 0.00 | 1.3 | 0.54 |

| Fru-1,6-bisphosphatase | Os06g0664200 | −1.3 | −2.5 | 0.00 | −2.3 | 0.00 | −1.3 | 0.29 | −2.0 | 0.00 | −2.1 | 0.00 | 1.2 | 0.81 |

| Pyrophosphate-Fru-6-P 1-phosphotransferase | Os06g0247500 | −1.1 | −2.2 | 0.00 | −2.0 | 0.00 | −1.1 | 0.49 | −2.0 | 0.00 | −2.1 | 0.00 | −1.4 | 0.22 |

| Fru-6-P 2-kinase/Fru-bisphosphatase | Os03g0294200 | −1.0 | −2.0 | 0.00 | −2.0 | 0.00 | 1.2 | 0.48 | −2.1 | 0.00 | −2.1 | 0.00 | 1.1 | 0.76 |

| Transketolase | Os06g0133800 | −1.0 | −2.0 | 0.00 | −2.2 | 0.00 | −1.2 | 0.40 | −2.1 | 0.00 | −2.3 | 0.00 | 1.4 | 0.17 |

| Rib-5-P isomerase | Os03g0781400 | −1.7 | −3.2 | 0.00 | −2.1 | 0.00 | 1.1 | 0.43 | −3.1 | 0.00 | −4.5 | 0.00 | −1.4 | 0.12 |

| Rib-5-P isomerase | Os02g0158300 | −1.3 | −2.5 | 0.00 | −2.1 | 0.00 | 1.1 | 0.91 | −2.9 | 0.00 | −4.0 | 0.00 | 1.2 | 0.97 |

| Phospho 2-dehydro 3-deoxyheptonate aldolase 2 | Os10g0564400 | −1.1 | −2.2 | 0.00 | −2.0 | 0.00 | −1.3 | 0.28 | −2.2 | 0.00 | −2.0 | 0.00 | 1.1 | 0.44 |

| NAD-dependent epimerase/dehydratase | Os12g0420200 | −1.4 | −2.6 | 0.00 | −2.8 | 0.00 | −1.4 | 0.07 | −2.3 | 0.00 | −2.1 | 0.00 | 1.4 | 0.07 |

| HpcH/HpaI aldolase family protein. | Os09g0529900 | −1.4 | −2.6 | 0.00 | −2.3 | 0.00 | 1.0 | 0.92 | −2.5 | 0.00 | −2.2 | 0.00 | 1.1 | 0.44 |

| D4 | ||||||||||||||

| Triose phosphate/phosphate translocator | Os08g0344600 | −1.4 | −2.6 | 0.00 | −2.6 | 0.00 | −1.4 | 0.13 | −2.0 | 0.00 | −2.0 | 0.00 | 1.2 | 0.84 |

| Phosphoglucomutase | Os10g0189100 | −1.0 | −2.0 | 0.00 | −2.1 | 0.00 | −1.3 | 0.11 | −2.0 | 0.00 | −2.1 | 0.00 | 1.3 | 0.90 |

| Fructokinase | Os08g0113100 | −1.1 | −2.1 | 0.00 | −2.3 | 0.00 | −1.1 | 0.55 | −2.3 | 0.00 | −2.1 | 0.00 | 1.4 | 0.25 |

| Phosphofructokinase | Os06g0151900 | −1.6 | −3.0 | 0.00 | −3.7 | 0.00 | 1.0 | 0.99 | −2.9 | 0.00 | −3.6 | 0.00 | 1.3 | 0.94 |

| β-Fructofuranosidase | Os01g0966700 | −1.3 | −2.5 | 0.00 | −2.8 | 0.00 | −1.4 | 0.10 | −2.6 | 0.00 | −3.2 | 0.00 | 1.3 | 0.98 |

| Plastidic α-1,4-glucan phosphorylase 2 | Os03g0758100 | −1.2 | −2.3 | 0.00 | −2.0 | 0.00 | −1.4 | 0.19 | −2.3 | 0.00 | −2.0 | 0.00 | −1.2 | 0.03 |

| Granule-bound starch synthase Ib | Os07g0412100 | −1.4 | −2.6 | 0.00 | −2.6 | 0.00 | −1.1 | 0.78 | −2.3 | 0.00 | −2.6 | 0.00 | 1.0 | 0.24 |

| Starch synthase isoform zSTSII-2 | Os02g0744700 | −1.9 | −3.7 | 0.00 | −3.5 | 0.00 | 1.1 | 0.71 | −2.4 | 0.00 | −2.1 | 0.00 | 1.4 | 0.50 |

| D5 | ||||||||||||||

| Gln synthetase | Os06g0699700 | −1.7 | −3.2 | 0.0 | −2.8 | 0.00 | 1.0 | 0.9 | −2.1 | 0.0 | −2.1 | 0.00 | 1.1 | 0.39 |

| Gln synthetase | Os05g0430800 | −1.1 | −2.1 | 0.0 | −2.0 | 0.00 | −1.3 | 0.2 | −2.1 | 0.00 | −2.0 | 0.00 | −1.1 | 0.12 |

| Ferredoxin-dependent Glu synthase | Os07g0676200 | −1.4 | −2.6 | 0.00 | −2.3 | 0.01 | −1.1 | 0.30 | −2.8 | 0.00 | −2.3 | 0.00 | 1.2 | 0.89 |

| Ferredoxin-dependent Glu synthase | Os07g0658400 | −1.3 | −2.5 | 0.00 | −2.6 | 0.00 | −1.3 | 0.38 | −2.6 | 0.00 | −2.9 | 0.00 | 1.1 | 0.30 |

Accession numbers for full-length cDNA sequences of the corresponding genes. bNumbers represent the mean fold values of three independent biological replicates. cP values were analyzed by one-way ANOVA.

The 3′ UTR of a Transcript Is a Major Determinant of SMD during Stress Conditions

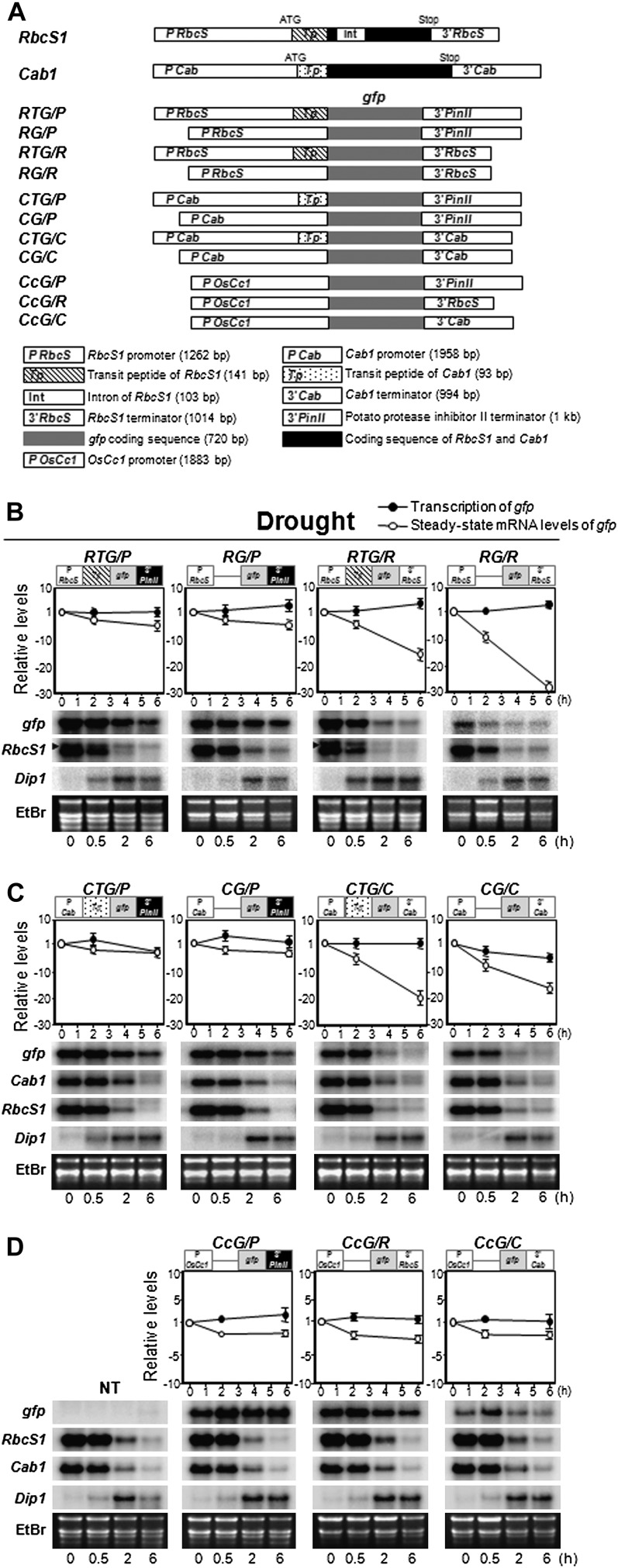

It has been reported previously that specific cis-acting mRNA elements in mammalian cells, typically found in their 5′ and 3′ UTRs, are involved in the induction of mRNA instability in response to extracellular stimuli (Shim and Karin, 2002). To define the photosynthetic mRNA regulatory elements that act in SMD, we dissected RbcS1 and Cab1 genes into three components: the upstream promoter region encompassing the 5′ UTR, the transit peptide (Tp), and the 3′ UTR (Fig. 4). For each gene, four different constructs were created containing various combinations of these three components and the GFP (gfp) coding region (Fig. 4A). Two respective Tps were linked to their own promoter, as shown by the small schemes above the graphs in Figure 4, B and C, and in Supplemental Figure S4, A and B. Transgenic rice plants expressing these constructs were generated via the Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated method, and the T3 homozygous plants were analyzed.

Figure 4.

Changes in transcription and steady-state mRNA levels of gfp in transgenic rice plants under drought stress conditions. A, Gene construct diagrams illustrating the various combinations of promoter, transit peptide, and 3′ UTR sequences from RbcS1 and Cab1 and the heterologous constitutive promoter of OsCc1. RbcS1 and Cab1, which are present as single copies in the rice genome (top panel), were dissected into three regions: promoter (P RbcS and P Cab), transit peptide (Tp), and 3′ UTR sequence (3′RbcS and 3′Cab). The respective DNA fragments were amplified by genomic PCR and fused to the gfp coding sequence to generate the expression vectors shown. The 3′PinII terminator sequence (An et al., 1989) was used as a negative control. B to D, Transcription and steady-state mRNA levels were measured using leaf tissues from transgenic rice plants transformed with the constructs shown in A after exposure to drought stress for the indicated times (top panels). Small schemes showing the configuration of the GFP constructs are shown above the graphs. Transcription of the gfp transgene was measured by Pol II-ChIP assays. Steady-state levels of gfp mRNA were measured by q-PCR analysis with cDNA synthesized from total RNAs of stress-treated transgenic leaves. Values are means ± sd of three independent q-PCR runs and are presented relative to results from unstressed controls with values set at 1. All mRNA levels were normalized to an internal control gene, Ubi1 (AK121590). Steady-state mRNA levels were also measured by RNA gel-blot analyses using gene-specific probes for gfp, Cab1, and Dip1 (bottom panels). For RbcS1, the probe used contained the transit peptide sequence. Thus, the slower migrating transcripts are from the RTG/P and RTG/R transgenes (Tp:gfp; indicated with arrowheads in B), whereas the faster migrating transcripts are from the endogenous RbcS1 gene (Tp:RbcS1). Total RNA was isolated from transgenic leaf tissues after exposure to drought stress for the indicated times. Nontransgenic (NT) control plants are indicated. Ethidium bromide (EtBr) staining of rRNAs served as a loading control. B, RbcS1 constructs under drought stress conditions. C, Cab1 constructs under drought stress conditions. D, OsCc1 constructs under drought stress conditions.

We next evaluated gfp transcription and the steady-state mRNA levels in transgenic plants treated with 2 and 6 h of drought or salt stress using the Pol II-ChIP and qRT-PCR methods, respectively (Fig. 4; Supplemental Fig. S4). Over the time course of stress treatments, the steady-state gfp mRNA levels varied depending upon the transgenic construct, whereas transcription from the RbcS1 and Cab1 promoters did not change (Fig. 4, B and C). The steady-state gfp mRNA levels in the P-RbcS1/Tp/gfp/3′RbcS1 (RTG/R) and P-Cab1/Tp/gfp/3′Cab1 (CTG/C) transgenic plants dropped by 18- to 20-fold, respectively, in response to drought stress. In contrast, the steady-state gfp mRNA levels in P-RbcS1/Tp/gfp/3′PinII (RTG/P) and P-Cab1/Tp/gfp/3′PinII (CTG/P) transgenic plants in which the 3′ UTR of RbcS1 and the 3′Cab1 region was replaced with the 3′ UTR of PinII, a potato (Solanum tuberosum) proteinase inhibitor II gene, were only marginally reduced upon exposure to drought. This indicated the importance of the 3′ UTR for SMD. Removal of the transit peptide sequences RbcS1-Tp from RTG/R and RTG/P and Cab1-Tp from CTG/C and CTG/P did not impact on the relative steady-state levels of gfp mRNA over the drought time course. These patterns of gfp transcription and steady-state mRNA accumulation in the transgenic plants were very similar under salt stress conditions (Supplemental Fig. S4). Changes in the steady-state mRNA levels of gfp and endogenous RbcS1 and Cab1 during the stress treatments were verified by RNA gel-blot analysis (Fig. 4, B and C; Supplemental Fig. S4). The Dip1 and/or SalT genes were used as stress-inducible controls for drought and/or salt stress treatments, respectively. Interestingly, replacement of the RbcS1 and Cab1 promoters and respective 5′ UTRs with those of the constitutively expressed OsCc1 gene yielded transgenes that no longer responded to drought or salt stress conditions (Fig. 4, A and D; Supplemental Fig. S4), suggesting a coupling between the 3′ UTRs and 5′ UTRs/promoter. The half-lives of gfp transcripts measured in the RTG/R, CTG/C, CcG/R, and CcG/C transgenic plants after exposure to drought stress conditions were in agreement with the results from qRT-PCR shown in Figure 4, suggesting again the importance of the 3′ UTR for SMD (Supplemental Fig. S7). In conclusion, the segmentation and evaluation of two photosynthetic genes in this study has revealed that both 3′ and 5′ UTRs are the major mediators of SMD.

DISCUSSION

The regulation of mRNA stability is an important process in the control of gene expression. In plant cells, as in mammalian cells, the range of mRNA half-lives spans several orders of magnitude. Unstable mRNAs might have half-lives of less than 60 min, whereas those of stable mRNAs are in the order of days, with the average being several hours (Pérez-Ortín et al., 2007; Chiba and Green, 2009). Unstable mRNAs have attracted attention because they have regulatory functions that are important for growth and development. For example, mRNAs of the transcription factors c-myc and c-fos in mammalian cells (Guhaniyogi and Brewer, 2001) and mating-type genes in yeast (Peltz and Jacobson, 1992) are known to be highly unstable. In plants, transcripts for the photo-labile phytochrome in oat (Seeley et al., 1992) and those of several auxin-inducible genes in pea (Koshiba et al., 1995) are included in this category.

Global expression profiling has been used to monitor mRNA stability under different conditions. For example, Gutierrez et al. (2002) previously examined changes in mRNA degradation in Arabidopsis using cDNA arrays in response to different environmental conditions and/or developmental stages. These investigators identified a total of 325 Arabidopsis transcripts with estimated half-lives of 2 h or less. Similar experiments performed with Arabidopsis suspension cell cultures exposed to diverse abiotic stress events further showed that mRNA half-lives can vary widely (Narsai et al., 2007). In this study, we analyzed global mRNAs that become unstable under drought, high salt, or cold stress conditions using a 135K 3′-Tiling microarray that includes all 29,389 rice genes. The results of this analysis indicate that within 2 h of drought and salt stress conditions, the levels of 2,386 and 2,494 mRNAs, respectively, dropped by more than 2-fold (Fig. 3B; Table II). An RNA Pol II-ChIP (Fig. 1B) assay was employed to measure the transcriptional activity of selected rice genes. Because in yeast to human Pol II is known to be often preloaded onto the promoter prior to activation (Yearling et al., 2011), we measured the levels of RNA Pol II binding to the coding region of six representative genes that undergo stress-induced changes in transcription. To evaluate the specific effects of different stress treatments on mRNA decay, we calibrated the general decrease in transcription under stress conditions by normalizing the ChIP-q-PCR signals to the signals of the input DNA controls. As a result, the transcriptional activity of the six representative genes including RbcS1, Cab1, Dip1, and SalT remained relatively unaltered by stress treatments. Thus, our results suggest the presence of SMD, an active mechanism that drives mRNA turnover upon exposure to stress.

SMD was particularly evident for genes involved in photosynthesis, as the mRNA levels for light and dark reaction genes were reduced more rapidly than for other genes under stress conditions (Table III; Supplemental Fig. S6). The mRNA turnover during the SMD of photosynthetic genes was verified by measuring the half-lives of RbcS1 and Cab1 during drought and salt stress conditions in the presence of the transcription inhibitor cordycepin (Fig. 1C). These half-lives dropped sharply from 123 and 239 min under normal growth conditions to 44 to 53 min, respectively, under drought and salt stress conditions (Fig. 1C; Table I), suggesting the importance of SMD in the stress-responsive regulation of photosynthesis. Photosynthesis is among the primary processes that are down-regulated under drought or salinity stress (Chaves, 1991; Munns et al., 2006; Chaves et al., 2009). Down-regulation has been attributed to consequences of decreased CO2 availability caused by diffusion limitations through the stomata and mesophyll (Flexas et al., 2004, 2007), alterations in photosynthetic metabolism (Lawlor and Cornic, 2002), or they can arise as secondary consequences of oxidative stress (Ort, 2001). When the supply of CO2 to Rubisco is impaired, the photosynthetic apparatus is predisposed to increased energy dissipation and down-regulates photosynthesis (Chaves et al., 2009). Additionally, increased levels of soluble sugars (Suc, Glc, and Fru) after moderate drought and salt stress contribute to the down-regulation of photosynthesis (Chaves and Oliveira, 2004). These changes in turn interact with hormones as part of the sugar signaling network (Rolland et al., 2006). Photosynthetic gene transcripts have been reported to decrease when the cellular sugar content is high (Stitt et al., 2007). The reaction centers of PSI and PSII in thylakoids are the major sites of reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation during photosynthesis. The photoproduction and subsequent scavenging of ROS not only protects chloroplasts from their direct effects but also relaxes the stress induced by excess photons (electrons; Asada, 2006). On the other hand, the continuation of photosynthesis during stress conditions may result in an elevation of ROS to levels sufficient to cause cell death. Retrograde (chloroplast-to-nucleus) signals, including ROS and carbohydrates from chloroplasts, regulate the expression of nuclear genes encoding photosynthetic proteins in accordance with the metabolic and developmental state of the organelle (Gray et al., 2003; Kleine et al., 2009). Thus, under stress conditions, nucleus-encoded photosynthetic mRNAs may need to turn over to enable plants to effectively cope with limited CO2 availability, unbalanced levels of soluble sugars, and increased chloroplast concentrations of ROS.

Universally, mRNA translation involves three distinct steps: initiation, elongation, and termination (Bailey-Serres, 1998). The polysomal level of an mRNA molecule reflects the efficiency of initiation and reinitiation as well as the rates of elongation and termination. The results of this study revealed that the polysome content is reduced by 17% to 19% depending upon the exposure levels to drought, high salinity, or cold stress (Fig. 2B). Similar global declines in protein synthesis were observed previously by monitoring the polysome content in response to water deficiency in soybean (Bensen et al., 1988; Mason et al., 1988), oat (Dhindsa and Cleland, 1975), maize (Zea mays; Hsiao, 1970), and tobacco (Kawaguchi et al., 2003) plants and in the seedlings of barley (Hordeum vulgare), pea, pumpkin (Cucurbita maxima), sunflower (Helianthus annuus), and safflower (Carthamus tinctorius; Rhodes and Matsuda, 1976). A partial reduction in polysome content in response to stress appears to be common among plants (Kawaguchi et al., 2004; Kawaguchi and Bailey-Serres, 2005). The analysis of polysomal mRNAs in tobacco has revealed that a subset of cellular mRNAs escape translational repression under drought conditions (Kawaguchi et al., 2003). In another previous study, two mRNA species encoding a putative lipid transfer protein and osmotin remained associated with large polysomes under drought stress conditions, whereas polysome-associated mRNAs encoding RbcS and eukaryotic initiation factor 4A decreased (Kawaguchi et al., 2003). Likewise, we found in this analysis that the mRNA levels of Dip1 and SalT, both stress-inducible genes, remained associated with polysomes even under stress conditions, whereas the polysome association of RbcS1 and Cab1 mRNAs decreased. More specifically, 42%, 38%, and 9% of mRNAs that are subjected to SMD under drought, salt, and cold stress conditions, respectively, appear to remain associated with polysomes (Table II). In contrast, 50%, 47%, and 76% of mRNAs that were found to be repressed in the total mRNA pool, but not in the polysomal pool, could either remain associated with polysomes or be degraded in a place other than polysomes. The former was revealed by our analysis of the spot intensities on microarray data sets on total and polysomal mRNA pools. Spot intensities of many of those genes, in fact, remained comparably high in both stress-treated and untreated polysomal mRNA pools, 21 genes of which are shown in Supplemental Table S2 as a representative example. Transcripts that are not associated with polysomes under stress conditions, however, could be stored in either P-bodies (Parker and Sheth, 2007) or stress granules (Anderson and Kedersha, 2008) such as translationally repressed messenger ribonucleoproteins found in eukaryotes, and subsequently degraded.

As shown previously in clusters of orthologous groups (Tatusov et al., 1997, 2003), our analysis here (Supplemental Fig. S8) revealed that transcripts in the functional categories T (signal transduction mechanisms) and O (posttranslational modification, protein turnover, chaperones) are controlled by both polysome-associated and unassociated SMD. In contrast, C (energy production and conversion) and G (carbohydrate transport and metabolism) category mRNAs are controlled mainly by polysome-independent SMD. Most of the mRNAs (8%, 15%, and 15% of mRNAs denoted as Polysomal mRNA in Table II) for which the polysomal but not the total mRNA levels were repressed upon treatment with drought, salt, and cold stress, respectively, were found to be in categories J (translation, ribosomal structure, and biogenesis), Q (secondary metabolite biosynthesis, transport, and metabolism), and T (Supplemental Fig. S8).

Translational regulation is largely determined by the characteristics of the 5′ and 3′ UTRs, including the m7Gppp cap and the poly(A) tail, the context of the AUG start codon, the presence of upstream open reading frames, specific nucleotide content, as well as primary sequence and structural elements (Wilkie et al., 2003; Kawaguchi and Bailey-Serres, 2005; Hughes, 2006; Sonenberg and Hinnebusch, 2009). SAUR transcripts, which are among the most unstable plant mRNAs, with half-lives of between 10 and 50 min, are induced within minutes of the application of auxin. The instability of SAUR mRNAs has been attributed mainly to the presence of a conserved DST element in their 3′ UTRs (Gil et al., 1994; Gil and Green, 1996). Consistent with data obtained for the SAURs, our analysis of two photosynthetic genes led to the observation that the 3′ UTR of RbcS1 and Cab1 mRNA harbors one of the important determinants of instability of these transcripts under stress conditions. In addition, the 3′ UTRs of RbcS1 and Cab1 mRNA must be coupled to their respective promoters and 5′ UTRs in order to manifest SMD. Replacement of the RbcS1 and Cab1 promoters including the 5′ UTRs with that of constitutively expressed OsCc1 abolished the SMD of the 3′ UTRs of RbcS1 and Cab1 mRNA (Fig. 4). Thus, our findings here demonstrate that in rice, the mRNAs of photosynthetic genes are destabilized upon exposure to stress conditions in a polysome-associated manner. This stress-induced mRNA decay appears to be mediated by determinants within the 3′ UTR that are augmented by the presence of the cognate promoter and 5′ UTR. These findings indicate that the posttranscriptional regulation of photosynthetic genes is a significant component of abiotic stress responses in rice and that the control of mRNA stability is an alternative strategy for improving stress tolerance in plants.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Materials and Treatments

Transgenic and nontransgenic rice (Oryza sativa ‘Nakdong’) plants were grown as follows. Sterilized seeds were germinated in Murashige and Skoog solid medium in a growth chamber in the dark at 28°C for 3 d and then in the light at 28°C for 1 d, transplanted into soil, and grown in a greenhouse (16-h-light/8-h-dark cycle) at 28°C to 30°C. Each plant was grown in a pot (4 × 4 × 5 cm3; six plants per pot) filled with rice nursery soil (Bio-Media) for 14 d after germination. Stress treatments were performed as described previously (Oh et al., 2009; Jeong et al., 2010; Redillas et al., 2011). Briefly, for drought stress, 14-d seedlings were air dried in the greenhouse under continuous light of approximately 900 to 1,000 μmol m−2 s−1. For salt stress treatments, 14-d seedlings were transferred to a 400 mm NaCl solution in the greenhouse under identical light conditions. For cold stress treatments, 14-d seedlings were exposed to 4°C in a cold chamber under continuous light of 150 μmol m−2 s−1. Before stress treatments were applied, plants had been grown in the greenhouse under continuous light of approximately 900 to 1,000 μmol m−2 s−1 in a pot for the drought stress group and in tap water for 3 d for the salt stress group for environmental adaptation. Nontreated control seedlings were grown in parallel in the greenhouse and a growth chamber under identical light conditions and harvested at time zero. After each experimental procedure, leaf tissue was rapidly harvested using liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until use.

Plasmid Construction and Rice Transformation

RbcS1 and Cab1 were dissected into three cis-acting elements: promoter (P RbcS and P Cab), transit peptide sequence (Tp), and 3′ UTRs (3′RbcS and 3′Cab). Respective DNA fragments were then isolated using genomic PCR with the primer pairs listed in Supplemental Table S1 and then fused with gfp (Chiu et al., 1996) to generate expression constructs. Plasmids were introduced into Agrobacterium tumefaciens LBA4404 by triparental mating, and embryogenic (cv Nakdong) calli from mature seeds were transformed as described previously (Jang et al., 1999). Three T3 homozygous lines were initially analyzed for each GFP construct, and one representative line was chosen for more detailed analysis.

RNA Gel-Blot Analysis

Total RNA was extracted from the leaves of transgenic and nontransgenic rice plants using Tri Reagent (Molecular Research Center). Ten micrograms of total RNA was electrophoresed on a 1.2% (w/v) agarose gel containing iodoacetamide and blotted onto a Hybond N+ nylon membrane (Amersham). Prepared membranes were hybridized with the gene-specific probes for RbcS1, Cab1, RA, PCY, Dip1, SalT, and gfp genes. Probe DNAs were labeled with [α-32P]dCTP using a random primer labeling kit (Takara) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. After hybridization, the membranes were washed in sequence with 2× SSC (0.3 m NaCl, 50 mm sodium citrate, pH 7.0) with 0.1% (w/v) SDS solution, 1× SSC with 0.1% (w/v) SDS solution, and then 0.5× SSC with 0.1% (w/v) SDS solution at 65°C for 15 min each. Membranes were then exposed to film on an intensifying plate and analyzed using a phosphoimage analyzer (FLA 3000; Fuji).

RNA Pol II-ChIP

Pol II-ChIP is a method for estimating transcriptional activity in vivo (Supplemental Fig. S2; Bowler et al., 2004; Sandoval et al., 2004; Tsuji et al., 2006; Chung et al., 2009). The antibody used in the ChIP experiments herein was anti-Pol II CTD (sc-900; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). ChIP assays were performed according to Chung et al. (2009). Rice plants (14 d old) were harvested and then immediately immersed in cross-linking buffer (0.4 m Suc, 10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 5 mm β-mercaptoethanol, and 1% formaldehyde) under a vacuum infiltrate for 15 min. Cross-linking was stopped by the addition of Gly to a final concentration of 125 mm under a vacuum. After washing the plants in cold water, the leaves were removed, frozen in liquid nitrogen, finely ground in buffer 1 (0.4 m Suc, 10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, and 5 mm β-mercaptoethanol), filtered through two layers of Miracloth (Calbiochem, EMD/Merck; http://splash.emdbiosciences.com), and then centrifuged at 2,880g for 20 min. The resulting pellet was dissolved in buffer 2 (0.25 m Suc, 10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 10 mm MgCl2, 1% Triton X-100, and 5 mm β-mercaptoethanol), centrifuged again at 14,000g for 10 min, resuspended in buffer 3 (1.7 m Suc, 10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 2 mm MgCl2, 0.15% Triton X-100, and 5 mm β-mercaptoethanol), layered on the top of an equal quantity of buffer 3, and then centrifuged at 16,000g for 60 min. Finally, the pellet (nuclei-enriched fraction) was resuspended in nuclear lysis buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 10 mm EDTA, and 1% SDS). All steps were performed at 4°C .The nuclei-enriched fractions were sheared by sonication using a Bioruptor device (Cosmo Bio) into fragments of less than 500 bp and then centrifuged. The protein concentration in the supernatant was determined using the Bradford method (Bio-Rad Laboratories). An aliquot (100 μg) of chromatin solution was used as the total input DNA. For ChIP assays, 100 μg of chromatin solution was diluted 10 times with ChIP dilution buffer (16.7 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 1.1% Triton X-100, 1.2 mm EDTA, and 167 mm NaCl). To minimize any nonspecific background, the chromatin solutions were precleared with a 1/50th volume of protein A-agarose (50% slurry, containing salmon sperm DNA and 0.1% bovine serum albumin) for 2 h at 4°C on a rotation wheel and centrifuged. The chromatin solutions were then immunoprecipitated overnight at 4°C by adding the appropriate antibodies, typically at a 1:150 dilution. Immunoprecipitates were collected after incubation with a 1/50th volume of salmon sperm DNA/protein A-agarose at 4°C for 2 h. The protein A-agarose beads bearing immunoprecipitates were then subjected to sequential washes with low-salt wash buffer (150 mm NaCl, 0.1% SDS, 1% Triton X-100, 2 mm EDTA, and 20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0), high-salt wash buffer (500 mm NaCl, 0.1% SDS, 1% Triton X-100, 2 mm EDTA, and 20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0), LiCl wash buffer (0.25 m LiCl, 1% Nonidet P-40, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 1 mm EDTA, and 10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0), and TE buffer (10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, and 1 mm EDTA), and the immunoprecipitates were eluted twice with 250 μL of elution buffer (1% SDS and 0.1 m NaHCO3) at 65°C. To reverse the cross-linking of the chromatin fractions, the eluted solutions were mixed with NaCl to a final concentration of 0.3 m and incubated at 65°C for 6 h. Finally, RNA and protein were removed by treatment with RNase A at 65°C for 1 h and with proteinase K at 45°C for 1 h, respectively. Immunoprecipitated DNAs were purified using a phenol/chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation. Purified DNA was used as a template for real-time PCR using gene-specific primers (Supplemental Table S1). The primer positions are as follows: RbcS1, 128 bp from +372 to +499; Cab1, 142 bp from +674 to +815; Dip1, 124 bp from +259 to +382; SalT, 121 bp from +264 to +384; OsCc1, 115 bp from +195 to +309; and Ubi1, 187 bp from +1,149 to +1,267. Input DNA controls were diluted 1:100 and quantified by RT-PCR. The values obtained were used to normalize the levels of DNA after immunoprecipitation. The signal intensities shown in Figures 1B and 4 and Supplemental Figure S4 are presented as ChIP-PCR signals normalized using input DNA controls.

Measurements of mRNA Half-Lives

mRNA half-lives were determined as described previously by Lidder et al. (2005). Briefly, 2-week-old rice seedlings were transferred to tap water and grown for 2 d. Cordycepin (3′-deoxyadenosine) was added to a final concentration of 1 mm. Tissue samples were thereafter harvested over a time course and frozen in liquid nitrogen. Total RNA was isolated using Tri Reagent (Molecular Research Center) and analyzed by q-RT-PCR. Half-lives were calculated using regression lines (Sigma Plot version 10.0; www.systat.com).

Isolation of Total and Polysomal RNAs

Polysomes were isolated from crude leaf extracts as described previously by Kawaguchi et al. (2004). Briefly, a 7.5-mL packed volume of pulverized leaf tissue was hydrated in 15 mL of extraction buffer and then centrifuged at 16,000g for 20 min to remove cell debris. Total RNA was isolated from this crude extract using the Plant RNeasy kit (Qiagen) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. For polysomal mRNA isolation, the ribosome complexes in the plant extracts were concentrated by centrifugation through a 1.75 m Suc cushion and then the supernatant was further fractionated through a 20% to 60% Suc density gradient by ultracentrifugation (4°C, 170,000g, 18 h; Mustroph et al., 2009). Fourteen fractions were then obtained by use of a gradient fractionator connected to a UA-5 detector (ISCO). The quantification of polysome levels was performed as described previously using the integration of peaks from the absorbance profile data (Williams et al., 2003). Fractions 1 to 6 (monosome, Suc gradient region containing 80S monosomes, and messenger ribonucleoprotein complexes) and fractions 8 to 13 (polysomal RNA, gradient region containing disomes, and complexes of greater density) were combined. The region between the monosome and disome peaks (fraction 7) and the bottom of the gradient (fraction 14) were not used. Relative polysomal RNA contents were determined using three independent biological samples. The combined gradient fractions were mixed with an equal volume of 8 m guanidine hydrochloride and vortexed for 3 min. RNA was precipitated by the addition of 1.5 volumes of ethanol, an overnight incubation at −20°C, and centrifugation at 12,100g for 45 min in a JA-20 rotor (Beckman). The RNA pellet was then resuspended in 450 µL of RLT buffer (Qiagen) from the Plant RNeasy kit, and the RNA was recovered in accordance with the manufacturer’s protocol. The RNA was then quantified using A260 measurements, and the concentration was adjusted to 1 µg µL−1.

qRT-PCR Analysis

Total and polysomal RNAs were extracted from the leaves of transgenic and nontransgenic rice plants using the RNeasy Plant Mini kit (Qiagen). For PCR amplification, cDNA was synthesized using a First-Strand cDNA synthesis kit (Fermentas) and oligo(dT) primers. Subsequent RT-PCR was carried out with 40 ng of cDNA template and gene-specific primer pairs (Supplemental Table S1) designed with Primer Designer 4 software version 4.20 (Sci-Ed Software). qRT-PCR analysis was carried out using 2× RT-PCR Premix with EvaGreen (SolGent). Reactions were performed at 95°C for 15 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 20 s, 58°C for 40 s, and 72°C for 20 s, in a 20-μL volume mix containing 1 μL of 20× EvaGreen, 0.25 μm primers, and 40 ng of cDNA. Thermocycling and fluorescence detection were performed using a Stratagene Mx3000p Real-Time PCR machine and Mx3000P software version 2.02 (Stratagene). Melting curve analysis (55°C–95°C at a heating rate of 0.1°C s−1) was performed to RT-PCR was performed in triplicate for each cDNA sample. After amplification, the experiment was converted to a comparative quantification (calibrator) type of analysis with results analyzed using Mx3000P software version 2.02 (Stratagene). The Ubi1 (AK121590) gene was used to verify equal RNA loading for the RT-PCR analysis and as a reference in the RT-PCR. The amplified PCR products were sequenced to ensure fidelity.

Rice 3′-Tiling Microarray Analysis

Expression profiling was conducted on total and polysomal RNA using the Rice 3′-Tiling microarray manufactured by NimbleGen (http://www.nimblegen.com/). This microarray contains 29,389 genes deposited at the International Rice Genome Sequencing Project Rice Annotation Project 1 database (http://rapdb.lab.nig.ac.jp). Further information on this microarray, including statistical analysis, is available at http://www.ggbio.com (GreenGene Biotech). Four probes of 60 nucleotides were designed from each gene sequence starting at 60 bp upstream of the stop codon and incorporating 30-bp shifts in position, so that they covered a 150-bp stretch within the 3′ region of the gene. In total, 125,956 probes were designed using this methodology (average size, 60 nucleotides). The signal data obtained from the Robust Multichip Average analyses of the polysomal RNA were further adjusted based on the relative polysome content measured in three replicate experiments (nontreated = 0.71, drought = 0.57, salt = 0.59, cold = 0.58). The 8,129 mRNAs with 2-fold or greater differential expression in at least one experimental condition were selected for further analysis (P < 0.05; mRNAs displaying only present calls via a median polish algorithm). In groups of mRNAs with similar patterns of expression, the gene expression profiles induced by three different stress treatments were further compared using cluster analysis (Eisen et al., 1998).

The microarray data sets used in this study can be found at the Gene Expression Omnibus database (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) under accession number GSE32065.

Supplemental Data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Figure S1. Changes in the steady-state mRNA levels of photosynthesis-related genes under drought, salt stress, and cold treatment conditions.

Supplemental Figure S2. RNA Pol II-ChIP assay.

Supplemental Figure S3. Outline of the evaluation of total and polysomal mRNA abundance under nontreated, drought, salt, and cold stress conditions.

Supplemental Figure S4. Changes in the gfp transcription and steady-state mRNA levels in transgenic rice plants in response to salt stress.

Supplemental Figure S5. Cordycepin is effective in blocking transcription in rice plants.

Supplemental Figure S6. Groups (L1–L7 and D1–D5 from Table III) of photosynthetic genes involved in light and dark reactions.

Supplemental Figure S7. Quantification of the decrease in mRNA abundance and half-life estimations in transgenic plants.

Supplemental Figure S8. Numbers of total and polysomal mRNAs with altered expression under drought, salt, and cold stress conditions.

Supplemental Table S1. Primers used in this study for qRT-PCR, q-PCR, and semiquantitative-RT-PCR analyses and for plasmid construction.

Supplemental Table S2. Microarray data for 21 genes that were repressed in total mRNA pools but not in polysomal mRNA pools under drought, salt, and cold stress conditions.

Supplementary Material

Glossary

- SMD

stress-induced mRNA decay

- UTR

untranslated region

- DST

downstream

- RT

real-time

- q

quantitative

- qRT

quantitative real-time

- ChIP

chromatin immunoprecipitation

- Pol II

polymerase II

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- qRT

quantitative real-time

- cDNA

to be defined

References

- An G, Mitra A, Choi HK, Costa MA, An K, Thornburg RW, Ryan CA. (1989) Functional analysis of the 3′ control region of the potato wound-inducible proteinase inhibitor II gene. Plant Cell 1: 115–122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson P, Kedersha N. (2008) Stress granules: the Tao of RNA triage. Trends Biochem Sci 33: 141–150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asada K. (2006) Production and scavenging of reactive oxygen species in chloroplasts and their functions. Plant Physiol 141: 391–396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey-Serres J. (1998) Selective translation of cytoplasmic mRNAs in plants. Trends Plant Sci 4: 1360–1385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey-Serres J, Sorenson R, Juntawong P. (2009) Getting the message across: cytoplasmic ribonucleoprotein complexes. Trends Plant Sci 14: 443–453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balagopal V, Parker R. (2009) Plysomes, P bodies and stress granules: states and fates of eukaryotic mRNAs. Curr Opin Plant Biol 21: 403–408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belostotsky DA, Sieburth LE. (2009) Kill the messenger: mRNA decay and plant development. Curr Opin Plant Biol 12: 96–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bensen RJ, Boyer JS, Mullet JE. (1988) Water deficit-induced changes in abscisic acid, growth, polysomes, and translatable RNA in soybean hypocotyls. Plant Physiol 88: 289–294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bevilacqua A, Ceriani MC, Capaccioli S, Nicolin A. (2003) Post-transcriptional regulation of gene expression by degradation of messenger RNAs. J Cell Physiol 195: 356–372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowler C, Benvenuto G, Laflamme P, Molino D, Probst AV, Tariq M, Paszkowski J. (2004) Chromatin techniques for plant cells. Plant J 39: 776–789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaves MM. (1991) Effects of water deficits on carbon assimilation. J Exp Bot 42: 1–16 [Google Scholar]

- Chaves MM, Flexas J, Pinheiro C. (2009) Photosynthesis under drought and salt stress: regulation mechanisms from whole plant to cell. Ann Bot (Lond) 103: 551–560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaves MM, Oliveira MM. (2004) Mechanisms underlying plant resilience to water deficits: prospects for water-saving agriculture. J Exp Bot 55: 2365–2384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiba Y, Green PJ. (2009) mRNA degradation machinery in plants. J Plant Biol 52: 114–124 [Google Scholar]

- Chiu WL, Niwa Y, Zeng W, Hirano T, Kobayashi H, Sheen J. (1996) Engineered GFP as a vital reporter in plants. Curr Biol 6: 325–330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung J-S, Zhu J-K, Bressan RA, Hasegawa PM, Shi H. (2008) Reactive oxygen species mediate Na+-induced SOS1 mRNA stability in Arabidopsis. Plant J 53: 554–565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung PJ, Kim YS, Jeong JS, Park S-H, Nahm BH, Kim J-K. (2009) The histone deacetylase OsHDAC1 epigenetically regulates the OsNAC6 gene that controls seedling root growth in rice. Plant J 59: 764–776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claes B, Dekeyser R, Villarroel R, Van den Bulcke M, Bauw G, Van Montagu M, Caplan A. (1990) Characterization of a rice gene showing organ-specific expression in response to salt stress and drought. Plant Cell 2: 19–27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen A, Moses MS, Plant AL, Bray EA. (1999) Multiple mechanisms control the expression of abscisic acid (ABA)-requiring genes in tomato plants exposed to soil water deficit. Plant Cell Environ 22: 989–998 [Google Scholar]

- Cushman JC, Michalowski CB, Bohnert HJ. (1990) Developmental control of Crassulacean acid metabolism inducibility by salt stress in the common ice plant. Plant Physiol 94: 1137–1142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhindsa RS, Cleland RE. (1975) Water stress and protein synthesis. I. Differential inhibition of protein synthesis. Plant Physiol 55: 778–781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisen MB, Spellman PT, Brown PO, Botstein D. (1998) Cluster analysis and display of genome-wide expression patterns. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 14863–14868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldbrügge M, Arizti P, Sullivan ML, Zamore PD, Belasco JG, Green PJ. (2002) Comparative analysis of the plant mRNA-destabilizing element, DST, in mammalian and tobacco cells. Plant Mol Biol 49: 215–223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flexas J, Bota J, Loreto F, Cornic G, Sharkey TD. (2004) Diffusive and metabolic limitations to photosynthesis under drought and salinity in C(3) plants. Plant Biol (Stuttg) 6: 269–279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flexas J, Diaz-Espejo A, Galmés J, Kaldenhoff R, Medrano H, Ribas-Carbo M. (2007) Rapid variations of mesophyll conductance in response to changes in CO2 concentration around leaves. Plant Cell Environ 30: 1284–1298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallie DR. (1996) Translational control of cellular and viral mRNAs. Plant Mol Biol 32: 145–158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gil P, Green PJ. (1996) Multiple regions of the Arabidopsis SAUR-AC1 gene control transcript abundance: the 3′ untranslated region functions as an mRNA instability determinant. EMBO J 15: 1678–1686 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gil P, Liu Y, Orbović V, Verkamp E, Poff KL, Green PJ. (1994) Characterization of the auxin-inducible SAUR-AC1 gene for use as a molecular genetic tool in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 104: 777–784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray JC, Sullivan JA, Wang JH, Jerome CA, MacLean D. (2003) Coordination of plastid and nuclear gene expression. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 358: 135–144, discussion 144–145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guhaniyogi J, Brewer G. (2001) Regulation of mRNA stability in mammalian cells. Gene 265: 11–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez RA, Ewing RM, Cherry JM, Green PJ. (2002) Identification of unstable transcripts in Arabidopsis by cDNA microarray analysis: rapid decay is associated with a group of touch- and specific clock-controlled genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99: 11513–11518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgs DC, Colbert JT. (1994) Oat phytochrome A mRNA degradation appears to occur via two distinct pathways. Plant Cell 6: 1007–1019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao TC. (1970) Rapid changes in levels of polyribosomes in Zea mays in response to water stress. Plant Physiol 46: 281–285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua XJ, Van de Cotte B, Van Montagu M, Verbruggen N. (2001) The 5′ untranslated region of the At-P5R gene is involved in both transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulation. Plant J 26: 157–169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes TA. (2006) Regulation of gene expression by alternative untranslated regions. Trends Genet 22: 119–122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang I-C, Choi W-B, Lee K-H, Song SI, Nahm BH, Kim J-K. (2002) High-level and ubiquitous expression of the rice cytochrome c gene OsCc1 and its promoter activity in transgenic plants provides a useful promoter for transgenesis of monocots. Plant Physiol 129: 1473–1481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang I-C, Nahm BH, Kim J-K. (1999) Subcellular targeting of green fluorescent protein to plastids in transgenic rice plants provides a high-level expression system. Mol Breed 5: 453–461 [Google Scholar]

- Jeong JS, Kim YS, Baek K-H, Jung H, Ha SH, Do Choi Y, Kim M, Reuzeau C, Kim J-K. (2010) Root-specific expression of OsNAC10 improves drought tolerance and grain yield in rice under field drought conditions. Plant Physiol 153: 185–197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawaguchi R, Bailey-Serres J. (2005) mRNA sequence features that contribute to translational regulation in Arabidopsis. Nucleic Acids Res 33: 955–965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawaguchi R, Girke T, Bray EA, Bailey-Serres J. (2004) Differential mRNA translation contributes to gene regulation under non-stress and dehydration stress conditions in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J 38: 823–839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawaguchi R, William AJ, Bray EA, Bailey-Serres J. (2003) Water-deficit-induced translational control in Nicotiana tabacum. Plant Cell Environ 26: 211–229 [Google Scholar]

- Kim YM, Kim JK, Hwang YS. (1994) Isolation and characterization of a rice full- length cDNA clone encoding a polyubiquitin. Plant Physiol 106: 791–792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleine T, Voigt C, Leister D. (2009) Plastid signalling to the nucleus: messengers still lost in the mists? Trends Genet 25: 185–192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koshiba T, Ballas N, Wong LM, Theologis A. (1995) Transcriptional regulation of PS-IAA4/5 and PS-IAA6 early gene expression by indoleacetic acid and protein synthesis inhibitors in pea (Pisum sativum). J Mol Biol 253: 396–413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawlor DW, Cornic G. (2002) Photosynthetic carbon assimilation and associated metabolism in relation to water deficits in higher plants. Plant Cell Environ 25: 275–294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lidder P, Gutiérrez RA, Salomé PA, McClung CR, Green PJ. (2005) Circadian control of messenger RNA stability: association with a sequence-specific messenger RNA decay pathway. Plant Physiol 138: 2374–2385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J-H, Hill RD. (1995) Post-transcriptional regulation of bifunctional α-amylase/subtilisin inhibitor expression in barley embryos by abscisic acid. Plant Mol Biol 29: 1087–1091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason HS, Mullet JE, Boyer JS. (1988) Polysomes, messenger RNA, and growth in soybean stems during development and water-deficit. Plant Physiol 86: 725–733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munns R, James RA, Läuchli A. (2006) Approaches to increasing the salt tolerance of wheat and other cereals. J Exp Bot 57: 1025–1043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustroph A, Juntawong P, Bailey-Serres J. (2009) Isolation of plant polysomal mRNA by differential centrifugation and ribosome immunopurification methods. Methods Mol Biol Plant Syst Biol 553: 109–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narsai R, Howell KA, Millar AH, O’Toole N, Small I, Whelan J. (2007) Genome-wide analysis of mRNA decay rates and their determinants in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell 19: 3418–3436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh SJ, Kim YS, Kwon CW, Park HK, Jeong JS, Kim J-K. (2009) Overexpression of the transcription factor AP37 in rice improves grain yield under drought conditions. Plant Physiol 150: 1368–1379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ort DR. (2001) When there is too much light. Plant Physiol 125: 29–32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker R, Sheth U. (2007) P bodies and the control of mRNA translation and degradation. Mol Cell 25: 635–646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peltz SW, Jacobson A. (1992) mRNA stability: in trans-it. Curr Opin Cell Biol 4: 979–983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Ortín JE, Alepuz PM, Moreno J. (2007) Genomics and gene transcription kinetics in yeast. Trends Genet 23: 250–257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redillas MC, Kim YS, Jeong JS, Strasser RJ, Kim J-K. (2011) The use of JIP test to evaluate drought-tolerance of transgenic rice overexpressing OsNAC10. Plant Biotechnol Rep 5: 169–176 [Google Scholar]

- Reznik B, Lykke-Andersen J. (2010) Regulated and quality-control mRNA turnover pathways in eukaryotes. Biochem Soc Trans 38: 1506–1510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes PR, Matsuda K. (1976) Water stress, rapid polyribosome reductions and growth. Plant Physiol 58: 631–635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolland F, Baena-Gonzalez E, Sheen J. (2006) Sugar sensing and signaling in plants: conserved and novel mechanisms. Annu Rev Plant Biol 57: 675–709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross J. (1995) mRNA stability in mammalian cells. Microbiol Rev 59: 423–450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandoval J, Rodríguez JL, Tur G, Serviddio G, Pereda J, Boukaba A, Sastre J, Torres L, Franco L, López-Rodas G. (2004) RNAPol-ChIP: a novel application of chromatin immunoprecipitation to the analysis of real-time gene transcription. Nucleic Acids Res 32: e88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sathish P, Withana N, Biswas M, Bryant C, Templeton K, Al-Wahb M, Smith-Espinoza C, Roche JR, Elborough KM, Phillips JR. (2007) Transcriptome analysis reveals season-specific rbcS gene expression profiles in diploid perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne L.). Plant Biotechnol J 5: 146–161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeley KA, Byrne DH, Colbert JT. (1992) Red light-independent instability of oat phytochrome mRNA in vivo. Plant Cell 4: 29–38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi H, Lee BH, Wu SJ, Zhu JK. (2003) Overexpression of a plasma membrane Na+/H+ antiporter gene improves salt tolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana. Nat Biotechnol 21: 81–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shim J, Karin M. (2002) The control of mRNA stability in response to extracellular stimuli. Mol Cells 14: 323–331 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonenberg N, Hinnebusch AG. (2009) Regulation of translation initiation in eukaryotes: mechanisms and biological targets. Cell 136: 731–745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stitt M, Gibon Y, Lunn JE, Piques M. (2007) Multilevel genomics analysis of carbon signalling during low carbon availability: coordinating the supply and utilisation of carbon in a fluctuating environment. Funct Plant Biol 34: 526–549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streatfield SJ. (2007) Approaches to achieve high-level heterologous protein production in plants. Plant Biotechnol J 5: 2–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan ML, Green PJ. (1996) Mutational analysis of the DST element in tobacco cells and transgenic plants: identification of residues critical for mRNA instability. RNA 2: 308–315 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanzer MM, Meagher RB. (1994) Faithful degradation of soybean rbcS mRNA in vitro. Mol Cell Biol 14: 2640–2650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatusov RL, Fedorova ND, Jackson JD, Jacobs AR, Kiryutin B, Koonin EV, Krylov DM, Mazumder R, Mekhedov SL, Nikolskaya AN, et al. (2003) The COG database: an updated version includes eukaryotes. BMC Bioinformatics 4: 41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatusov RL, Koonin EV, Lipman DJ. (1997) A genomic perspective on protein families. Science 278: 631–637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson DM, Tanzer MM, Meagher RB. (1992) Degradation products of the mRNA encoding the small subunit of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase in soybean and transgenic petunia. Plant Cell 4: 47–58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuji H, Saika H, Tsutsumi N, Hirai A, Nakazono M. (2006) Dynamic and reversible changes in histone H3-Lys4 methylation and H3 acetylation occurring at submergence-inducible genes in rice. Plant Cell Physiol 47: 995–1003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasudevan S, Peltz SW. (2001) Regulated ARE-mediated mRNA decay in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell 7: 1191–1200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warpeha KM, Upadhyay S, Yeh J, Adamiak J, Hawkins SI, Lapik YR, Anderson MB, Kaufman LS. (2007) The GCR1, GPA1, PRN1, NF-Y signal chain mediates both blue light and abscisic acid responses in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 143: 1590–1600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkie GS, Dickson KS, Gray NK. (2003) Regulation of mRNA translation by 5′- and 3′-UTR-binding factors. Trends Biochem Sci 28: 182–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams AJ, Werner-Fraczek J, Chang IF, Bailey-Serres J. (2003) Regulated phosphorylation of 40S ribosomal protein S6 in root tips of maize. Plant Physiol 132: 2086–2097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J, Chua N-H. (2009) Arabidopsis decapping 5 is required for mRNA decapping, P-body formation, and translational repression during postembryonic development. Plant Cell 21: 3270–3279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yearling MN, Radebaugh CA, Stargell LA. (2011) The transition of poised RNA polymerase II to an actively elongating state is a “complex” affair. Genet Res Int 2011: Article 206290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.