Abstract

The field of proteomics suffers from the immense complexity of even small proteomes and the enormous dynamic range of protein concentrations within a given sample. Most protein samples contain a few major proteins, which hamper in-depth proteomic analysis. In the human field, combinatorial hexapeptide ligand libraries (CPLL; such as ProteoMiner) have been used for reduction of the dynamic range of protein concentrations; however, this technique is not established in plant research. In this work, we present the application of CPLL to Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) leaf proteins. One- and two-dimensional gel electrophoresis showed a decrease in high-abundance proteins and an enrichment of less abundant proteins in CPLL-treated samples. After optimization of the CPLL protocol, mass spectrometric analyses of leaf extracts led to the identification of 1,192 proteins in control samples and an additional 512 proteins after the application of CPLL. Upon leaf infection with virulent Pseudomonas syringae DC3000, CPLL beads were also used for investigating the bacterial infectome. In total, 312 bacterial proteins could be identified in infected Arabidopsis leaves. Furthermore, phloem exudates of pumpkin (Cucurbita maxima) were analyzed. CPLL prefractionation caused depletion of the major phloem proteins 1 and 2 and improved phloem proteomics, because 67 of 320 identified proteins were detectable only after CPLL treatment. In sum, our results demonstrate that CPLL beads are a time- and cost-effective tool for reducing major proteins, which often interfere with downstream analyses. The concomitant enrichment of less abundant proteins may facilitate a deeper insight into the plant proteome.

Proteomics is the large-scale study of proteins and includes the exploration of all proteins present in a cell or an organism under certain conditions and at a certain time point. With each gene giving rise to not only a single protein, complex organisms are thought to produce hundreds of thousands of different proteins that additionally can undergo various posttranslational modifications. Although methods of proteomics, especially mass spectrometry (MS), are constantly improving, we are still seeing only a rather small subset of the total proteome. Another major problem inherent to all proteomic analyses is the enormous dynamic range of protein concentrations within a given sample, which can be up to 12 orders of magnitude (Corthals et al., 2000). Therefore, most protein samples contain a few high-abundance, dominating proteins and a large number of low-abundance proteins, which often fall below the detection limit of the technique used for analysis. Fractionation of samples reduces the complexity of the protein pool significantly. But high-abundance proteins still lead to masking and suppression effects during analysis with two-dimensional (2D) gel electrophoresis or MS.

Recently, a new technique has emerged that reduces the dynamic range of protein concentrations within a given sample using combinatorial hexapeptide ligand libraries (CPLL; Boschetti et al., 2007; Boschetti and Righetti, 2008a, 2008b, 2009; Fröhlich and Lindermayr, 2011). The CPLL were synthesized on beads by the split-couple-recombine method described in earlier works (Furka et al., 1991; Lam et al., 1991; Buettner et al., 1996). Use of the 20 naturally occurring amino acids theoretically resulted in 64 million different ligands, with each ligand fixed to a single bead (Thulasiraman et al., 2005; Boschetti and Righetti, 2008a). Specific binding of proteins to the CPLL is thought to depend on the physicochemical properties of the protein (e.g. conformation, hydrophobicity, and pI). The native conformation of the proteins, therefore, is preferred during treatment. The interactions between proteins and peptide ligands seem to be mainly stabilized by hydrophobic forces but also by other weak forces such as ion-ion, dipole-dipole, or hydrogen bonding (Bachi et al., 2008; Righetti and Boschetti, 2008; Keidel et al., 2010). Under capacity-restrained conditions, high-abundance protein species will saturate their ligand quickly, whereas low-abundance species will be bound completely. Unbound proteins will be removed from the matrix by washing, whereas bound proteins will be eluted from the matrix. The resulting protein solution should contain all proteins present in the original sample, albeit with a narrower dynamic range of protein concentrations.

The libraries, commercially available as ProteoMiner (Bio-Rad), have been used to reduce the dynamic range of protein concentrations in various samples, such as Escherichia coli crude extract and cell culture supernatant, human serum, and chicken egg white. Furthermore, CPLL have been used for the analysis of human urine, human bile, platelet lysate, red blood cell lysate, chicken egg white and egg yolk, or cow whey (Castagna et al., 2005; Thulasiraman et al., 2005; Guerrier et al., 2006, 2007a, 2007b; D’Ambrosio et al., 2008; Roux-Dalvai et al., 2008; Boschetti and Righetti, 2009; D’Amato et al., 2009; Farinazzo et al., 2009). In all these studies, a much larger number of proteins could be identified when using CPLL, with many of the proteins being described for the first time in the respective sample.

The completion of the Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) genome sequence revealed the presence of about 30,000 genes in this plant species. However, on the protein level, only a restricted number of different proteins can be detected. The main problem is the presence of some high-abundance proteins, which are limiting the detection of low-abundance proteins (Peck, 2005). In leaves, Rubisco accumulates up to 40% of total leaf protein (Stitt et al., 2010), and in the seed endosperm, storage proteins are present in massive amounts (Li et al., 2008). But even less extreme examples, like many housekeeping proteins, are present in sufficient amounts to hinder the analysis of low-abundance proteins. Recently, CPLL beads were used to identify leaf proteins of spinach (Spinacia oleracea). The authors performed capture of proteins at three different pH values and were able to identify 322 proteins, of which 190 could only be found in the CPLL-treated samples (Fasoli et al., 2011a). CPLL were also applied for analyses of some plant-derived products (D’Amato et al., 2010, 2011, 2012; Fasoli et al., 2010a, 2011b, 2012). However, although ProteoMiner has been on the market for 5 years, this technology has still not entered plant research.

Therefore, the overall goal of this study was the establishment of CPLL applications in plant proteomics. Protein extraction protocols were optimized for the incubation of Arabidopsis leaf proteins with CPLL. Subsequent analyses by one-dimensional (1D)-SDS-PAGE, two-dimensional fluorescence difference gel electrophoresis (2D-DIGE), and liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) showed a reduction of high-abundance proteins in CPLL-treated leaf extracts. It could also be demonstrated that CPLL allowed the identification of additional proteins that could not be detected in control samples. Currently, two protocols for the application of CPLL are available, and we compared both of them. Capture of Arabidopsis proteins by CPLL at three different pH values and elution from the beads using hot SDS/dithiothreitol (DTT) turned out to yield better results than CPLL treatment according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Following the optimized protocol, 1,192 proteins could be identified by LC-MS/MS in control samples but an additional 512 proteins were found only after the application of CPLL. Furthermore, we successfully used this technology to analyze, to our knowledge for the first time, the infectome of Pseudomonas syringae DC3000 during infection of Arabidopsis.

In an additional set of experiments, we applied ProteoMiner to liquid pumpkin (Cucurbita maxima) phloem samples. Cucurbitaceae species including pumpkin are model plants for phloem biochemistry, because exudates of the unique extrafascicular phloem (EFP) can be easily collected from cut petioles and stems (Van Bel and Gaupels, 2004; Atkins et al., 2011). A main obstacle of protein biochemistry with pumpkin phloem exudates is the high abundance (80% of total protein content) of Phloem Protein1 (PP1) and Phloem Protein2 (PP2). The use of CPLL beads caused a strong reduction in PP1/PP2 levels and facilitated the identification of 320 proteins, including 81 previously unknown phloem proteins.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Protocol I

Application of CPLL to Arabidopsis Leaf Extracts following the Manufacturer’s Instructions

Plant proteins are notoriously difficult to extract (Rose et al., 2004). This is mainly due to the low protein content of plant tissue and the low solubility of plant proteins. Furthermore, plants accumulate high levels of diverse metabolites, such as monosaccharides and polysaccharides, phenolic compounds, and oils that may interfere with downstream sample analysis. Our sample preparation protocol addressed these points by polyvinylpolypyrrolidone treatment and the use of size-exclusion columns to remove salts and secondary metabolites as well as NH4SO4 precipitation for concentrating proteins without severe denaturation.

In initial experiments, ProteoMiner was applied according to the manufacturer’s (Bio-Rad) instructions with some modifications. The ProteoMiner manual recommended the application of 10 mg of protein at concentrations of 50 mg mL−1 for incubation with the CPLL beads. However, the maximum protein concentration of Arabidopsis leaf extracts achieved with the described protocol was around 10 mg mL−1. Therefore, the suggested ratio of protein amount to bead slurry volume was maintained, but the sample volume was increased. Ten milligrams of protein per sample was mixed with 100 µL of bead slurry in a volume of 1 mL. In order to facilitate the binding of diluted proteins to the column, the incubation time was prolonged. Proteins were eluted from the beads with 8 m urea for breaking hydrogen bonds and protein denaturation. CHAPS at 2% was used to disrupt hydrophilic interactions. The average total protein yield per CPLL column was 364 µg, with a coefficient of variation (CV) of 4.7% over four extractions.

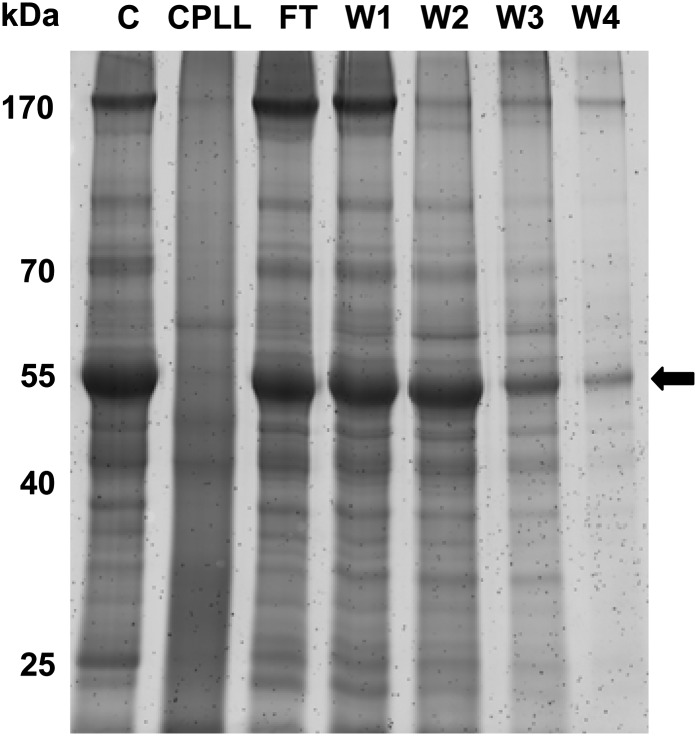

A first comparison of the protein pools of the crude extracts, washing fractions, and the CPLL eluates was done by 1D-SDS-PAGE (Fig. 1). Prominent bands representing the large and small subunits of Rubisco were highly abundant in flow-through and washing fractions but strongly reduced in the CPLL eluates. As specified in the manual, unbound proteins were largely removed after four washing steps.

Figure 1.

1D-SDS-PAGE of CPLL fractionation of Arabidopsis leaf proteins. Ten milligrams of leaf proteins was incubated with CPLL according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After four washing steps, proteins were eluted from the CPLL beads. Aliquots of the different fractions were separated by SDS-PAGE, and proteins were stained with Sypro Ruby. The relative masses of protein standards are indicated on the left. C, Crude leaf extract; CPLL, eluate; FT, flow through; W1 to W4, wash fractions. The position of the large subunit of Rubisco is marked with an arrow.

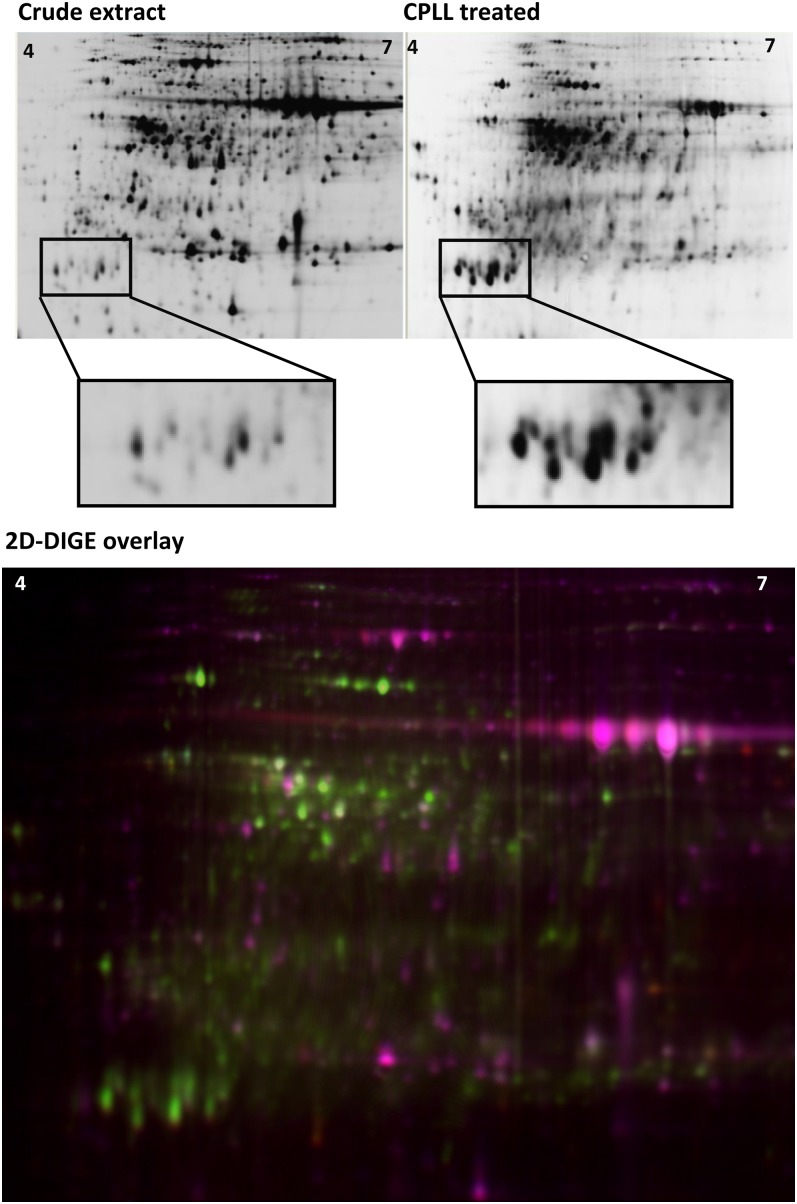

Protein crude extracts and CPLL eluates were also analyzed using the 2D-DIGE technology. 2D-DIGE enables the separation of multiple protein extracts on the same gel by labeling of each protein in the extracts using spectrally resolvable, size- and charge-matched fluorescent dyes. This method adds a highly accurate quantitative dimension to the commonly executed 2D analysis. For reducing biological variation, we used the same Arabidopsis crude extract for four parallel CPLL extractions. A strikingly different protein spot pattern could be observed between CPLL eluates and crude extracts in 2D-DIGE analysis (Fig. 2). The 2D-DIGE overlay image further illustrates the differences between the two sample types. In the Cy3-labeled CPLL sample, new spots appeared, whereas many of the intense spots present in the Cy5-labeled crude extract were missing or reduced in intensity.

Figure 2.

2D-DIGE analysis of the effect of CPLL fractionation on the Arabidopsis leaf proteome. Each 50-µg protein of crude extract and CPLL eluate was stained with two different probes and separated on the same gel by 2D-DIGE, resulting in strikingly different spot patterns. The top shows spot patterns for both samples separately (DIGE modus black/white). Boxed areas depict selected proteins enriched upon CPLL treatment. The bottom shows a 2D-DIGE fluorescent overlay image of the above CPLL-treated (green) and crude extract (red) samples. A pH gradient of 4 to 7 was used for isoelectric focusing. Results are representative of four independent 2D-DIGE experiments.

In four gel replicates, the DeCyder spot-finding algorithm found approximately 20% more spots in images depicting CPLL-captured proteins than in images of raw extract (data not shown; CV = 20.4%). A total of 305 leaf proteins were statistically significantly enriched and 400 proteins were significantly depleted in the CPLL-treated samples as compared with raw extracts (P < 0.05). Reducing the P value to P < 0.0001 still resulted in 119 enriched and 178 reduced proteins, pointing toward the high reproducibility of the method. The average CV across all matched spots on four replicate gels was 19.2%.

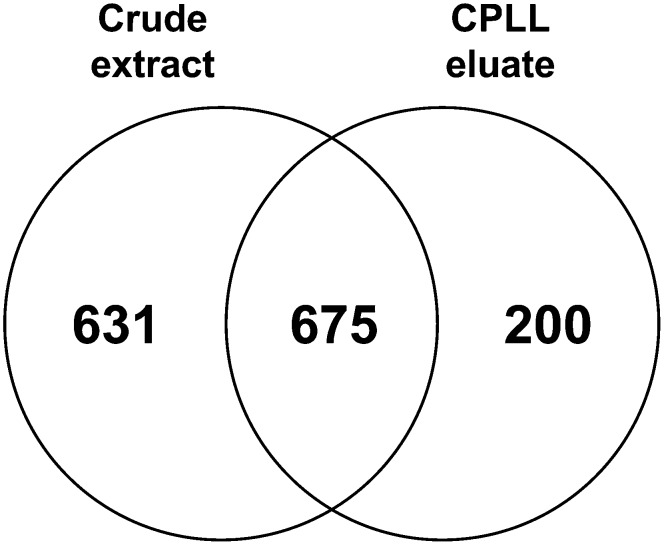

Crude extract and ProteoMiner eluate samples were subjected to LC-MS/MS analysis for protein identification. To reduce the complexity of the different samples, the proteins were separated by 1D-SDS-PAGE and the lanes were cut into 10 subfractions, which were analyzed separately by LC-MS/MS. In total, 1,489 plant proteins could be identified (Supplemental Table S1). A total of 200 proteins could be identified exclusively in the CPLL-treated sample, whereas 675 proteins were identified in both crude extract and CPLL samples. A total of 631 proteins were “lost” due to the ProteoMiner treatment and could be detected only in the crude extract (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

The effect of CPLL treatment on Arabidopsis leaf proteins. Leaf extracts were treated with CPLL according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The protein composition of the CPLL eluate was analyzed by LC-MS/MS and compared with the protein composition of the corresponding protein crude extract. A total of 1,284 unique proteins were identified in the control sample. Two hundred (15%) additional proteins could be identified by using CPLL for extraction.

Application of CPLL to Protein Extracts from Infected Leaves

In order to better assess the CPLL effect on a specific protein subpopulation within a given sample, we analyzed bacterial proteins in Arabidopsis leaves infected with virulent P. syringae DC3000. Arabidopsis plants were inoculated with virulent P. syringae DC3000 and were harvested when typical disease symptoms started to develop (approximately 24 h after inoculation). At that time point, the average bacterial concentration within infected leaves was 5 × 107 colony-forming units cm−2. The samples were subjected to CPLL technology using the ProteoMiner standard protocol (Bio-Rad). In total, 1,598 Arabidopsis and 312 bacterial proteins could be identified (Supplemental Tables S2 and S3). A total of 203 Arabidopsis proteins and 48 bacterial proteins were only found in the CPLL-treated samples, adding 15% and 18% new proteins, respectively, to the proteomes of nonfractionated crude extracts.

To our knowledge, this is the first analysis of an in planta pathogen proteome (“infectome”; Mehta et al., 2008). Approximately 5% of the P. syringae DC3000 genes encode for proteins involved in virulence (Rahme et al., 1995; Preston, 2000; Buell et al., 2003). Many of these proteins function in bacterial mobility, the nutrient transport system, reactive oxygen species detoxification, or biosynthesis of the bacterial polysaccharide capsule (Buell et al., 2003). When analyzing bacterial proteins within leaf extracts, 107 (34%) of the identified 312 P. syringae proteins were related to bacterial virulence, including enzymes from coronatine synthesis (coronafacic acid synthase subunits), alginate synthesis (alginate biosynthesis protein [AlgF], alginate lyase), transcriptional regulators (transcriptional regulator, LysR family [LysR], Cys regulon transcriptional activator [Cys regulon], transcriptional regulator AlgQ), ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters, outer membrane proteins (outer membrane porin [OprF], outer membrane protein [OmpA]), redox-related proteins (glutathione S-transferases, superoxide dismutases, thioredoxin, catalase), and flagellin. Selected bacterial proteins playing a role in P. syringae pathogenesis are shown in Table I. The complete lists of identified plant and bacterial proteins are given in Table II and Supplemental Table S1.

Table I. Identified proteins in infected Arabidopsis plants.

| Organism | Total | Control Only | In Both | CPLL Only |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arabidopsisa | 1,598 | 618 | 777 | 203 |

| P. syringaeb | 312 | 168 | 96 | 48 |

Number of identified Arabidopsis proteins in infected plants. bNumber of identified Pseudomonas proteins in infected plants.

Table II. Selected proteins of the P. syringae DC3000 infectome in leaf crude extracts and CPLL-treated extracts.

Arabidopsis plants were infected with P. syringae DC3000, and extracted leaf proteins were analyzed directly by LC-MS/MS or subjected to CPLL before MS analyses. MW, Molecular mass in kD.

| Function | Accession No. | MW | No. of Peptides | Hints to Involvement in Virulence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proteins identified in CPLL sample only | ||||

| Glc-1-P thymidylyltransferase | NP_790913 | 33 | 4 | Guo et al. (2012) |

| Gln synthetase | NP_795041 | 51 | 2 | Si et al. (2009) |

| Transcriptional regulator, LysR family | NP_795132 | 33 | 2 | Wharam et al. (1995) |

| RNA methyltransferase, TrmH family, group 3 | NP_794667 | 27 | 4 | Garbom et al. (2004) |

| Thr synthase | NP_791307 | 52 | 4 | Guo et al. (2012) |

| DNA topoisomerase I | NP_793294 | 97 | 2 | McNairn et al. (1995) |

| Amidophosphoribosyltransferase | NP_793585 | 56 | 3 | Guo et al. (2012) |

| Phosphate transport system protein PhoU | NP_795207 | 29 | 3 | Lamarche et al. (2008) |

| Ribose ABC transporter protein | NP_792188 | 15 | 2 | Kemner et al. (1997) |

| Acetyl-CoA carboxylase, biotin carboxylase | NP_794595 | 49 | 5 | Kurth et al. (2009) |

| ATP-dependent Clp protease, ATP-binding subunit ClpX | NP_793499 | 47 | 4 | Ibrahim et al. (2005) |

| Lysyl-tRNA synthetase | NP_791326 | 57 | 3 | Navarre et al. (2010) |

| Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase | NP_790090 | 56 | 2 | Liu et al. (2005) |

| Argininosuccinate synthase | NP_793916 | 45 | 4 | Ardales et al. (2009) |

| Coronamic acid synthetase CmaB | NP_794454 | 35 | 2 | Buell et al. (2003) |

| dTDP-Glc 4,6-dehydratase | NP_790915 | 40 | 3 | Sen et al. (2011) |

| Proteins identified in both crude extract and CPLL sample | ||||

| Coronafacic acid synthetase, dehydratase component | NP_794431 | 18 | 6/4 | Buell et al. (2003) |

| Coronafacic acid synthetase, ligase component | NP_794429 | 55 | 4/12 | Buell et al. (2003) |

| GDP-Man 6-dehydrogenase AlgD | NP_791073 | 48 | 9/11 | Buell et al. (2003) |

| Catalase/peroxidase HPI | NP_794283 | 83 | 8/2 | Jittawuttipoka et al. (2009) |

| Hfq protein | NP_794675 | 9 | 3/3 | Schiano et al. (2010) |

| Translation elongation factor P | NP_791590 | 21 | 4/2 | Navarre et al. (2010) |

| ATP-dependent Clp protease, proteolytic subunit ClpP | NP_793500 | 24 | 5/3 | Ibrahim et al. (2005) |

| Secreted protein Hcp | NP_795162 | 19 | 8/2 | Mougous et al. (2006) |

| Proteins identified in crude extract only | ||||

| Alginate biosynthesis protein AlgF | NP_791063 | 23 | 6 | Buell et al. (2003) |

| Alginate lyase | NP_791066 | 42 | 2 | Buell et al. (2003) |

| Catalase | NP_794994 | 79 | 3 | Fones and Preston (2012) |

| Flagellin | NP_791772 | 29 | 2 | Buell et al. (2003) |

| Iron ABC transporter, periplasmic iron-binding protein | NP_790164 | 37 | 3 | Rodriguez and Smith (2006) |

| Levansucrase | NP_791279 | 48 | 2 | Li et al. (2006) |

| Outer membrane porin OprF | NP_792118 | 37 | 6 | Fito-Boncompte et al. (2011) |

| Outer membrane protein OmpH, putative | NP_791368 | 19 | 5 | Fito-Boncompte et al. (2011) |

| Periplasmic glucan biosynthesis protein | NP_794893 | 71 | 5 | Buell et al. (2003) |

| Phosphate ABC transporter | NP_793052 | 37 | 8 | Buell et al. (2003) |

| Protein-export protein SecB | NP_795055 | 18 | 5 | Hueck (1998) |

| Sugar ABC transporter, periplasmic sugar-binding protein | NP_790728 | 46 | 8 | Buell et al. (2003) |

| Superoxide dismutase, iron | NP_794118 | 21 | 3 | Fones and Preston (2012) |

| Thiol:disulfide interchange protein DsbA | NP_790191 | 23 | 7 | Ha et al. (2003) |

| Transcriptional regulator AlgQ | NP_789993 | 18 | 2 | Buell et al. (2003) |

Protocol II

Application of CPLL to Arabidopsis Leaf Extracts Using Three pH Values and Hot SDS/DTT Elution

The effect of hexapeptide libraries on animal and human proteins was very pronounced, with a loss of proteins sometimes below 5% but up to 500% additional proteins captured (Di Girolamo et al., 2011). Because we identified only 15% additional leaf proteins when applying ProteoMiner according to the manufacturer’s instructions, we tried to further improve the CPLL protocol. Righetti and coworkers (Di Girolamo et al., 2011) reported that a reduction of salt in samples, capture at three pH values, and elution in boiling SDS/DTT strongly improved the efficacy of ProteoMiner in human serum. The rationale behind this study was that the relative affinity of hexapeptide libraries to proteins is defined by the experimental conditions, including pH. The use of three pH values (e.g. pH 4, 7, and 9) reduced the loss of proteins and further increased the total number of identified proteins after CPLL treatment (Fasoli et al., 2010b; Di Girolamo et al., 2011). For elution of captured proteins from the beads, boiling in 4% SDS/50 mm DTT turned out to be most efficient, with a protein recovery of more than 99% as compared with only approximately 50% by 7 m urea/2% CHAPS (Di Girolamo et al., 2011). We now adapted this optimized protocol to the extraction of low-abundance proteins from Arabidopsis leaf extracts. After protein extraction, the sample was split into three aliquots. Each fraction was subjected to size-exclusion chromatography for buffer exchange (pH 4, 7, or 9) and removal of interfering compounds such as salt, carbohydrates, and secondary metabolites. Whereas buffer exchange to pH 7 or 9 had no effect on the proteins, at pH 4 partial precipitation of some proteins could be observed. The acidic conditions are responsible for charge reversal. This breaks hydrogen bonds and results in the irreversible denaturation of proteins. Such a loss of proteins due to buffer exchange to pH 4 was also observed for spinach leaf proteins (P.G. Righetti, personal communication). After buffer exchange, samples were treated with CPLL beads and boiling SDS/DTT was used for complete elution of proteins from the CPLL beads. Nontreated samples served as pH controls.

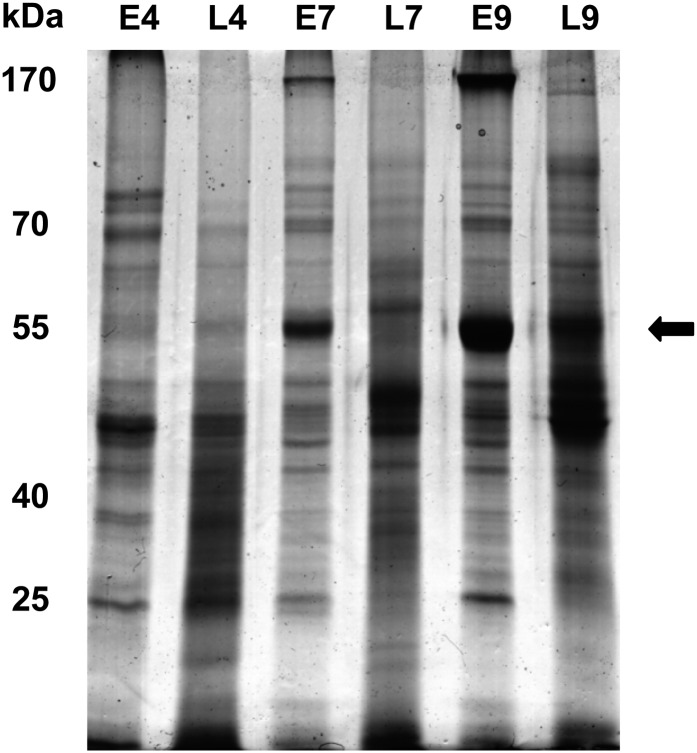

The different protein fractions of the ProteoMiner experiment were separated by 1D-SDS-PAGE. As shown in Figure 4, the amount of the large subunit of Rubisco was already strongly reduced after adjusting the leaf extract to pH 4. At pH 7 and 9, ProteoMiner treatment caused a depletion of the large Rubisco subunit and a remarkable change in protein composition. Some new bands appeared that were not visible in control extracts, probably representing moderate- to low-abundance proteins. Notably, no obvious difference between control samples at pH 7 and 9 could be observed, whereas after CPLL treatment band patterns were different between both pH values. Hence, the ProteoMiner effect seems indeed to be dependent on the pH, as reported previously for spinach leaf extracts (Fasoli et al., 2011a).

Figure 4.

Analysis of a pH-based CPLL fractionation of Arabidopsis leaf proteins by 1D-SDS-PAGE. Protein extracts were adjusted to pH 4, 7, and 9 before application of CPLL. After CPLL fractionation, 15 µg of each fraction was separated by 1D-SDS-PAGE. Proteins were stained with Sypro Ruby. The relative masses of protein standards are indicated on the left. E4, E7, and E9, Protein extract at pH 4, 7, and 9; L4, L7, and L9, corresponding CPLL-treated proteins. The position of Rubisco is marked with an arrow.

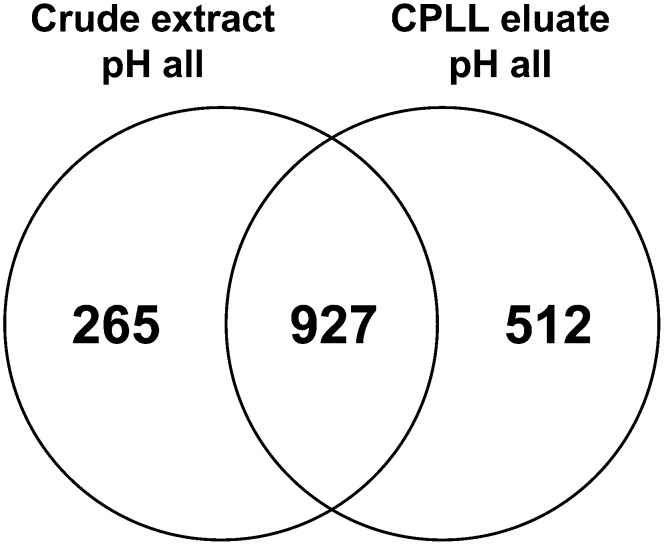

With the optimized experimental system combining three pH values, a total of 1,704 Arabidopsis leaf proteins were identified. Of these, 1,192 could be detected in control extracts and 512 (43% of control extracts) additional proteins were identified only after the application of ProteoMiner beads (Fig. 5; Supplemental Table S4). There was an overlap of 927 proteins between both data sets. A total of 265 (22%) proteins present in control samples were not found after ProteoMiner treatment, confirming that some proteins were not captured by the hexapeptide libraries or could not be eluted. In comparison with protocol I, the loss of proteins was clearly reduced and significantly more proteins were added to the proteome when protocol II was adopted. This was also true if protocol I was compared with protocol II, considering only the samples adjusted to pH 7. In this case, 15% versus 37% additional CPLL-specific proteins were identified using protocols I and II, respectively (Fig. 3; Supplemental Fig. S1). A major reason for the difference was probably the reduction of salt concentrations in samples and buffers and elution with hot SDS/DTT.

Figure 5.

Identification of Arabidopsis leaf proteins by LC-MS/MS after the application of CPLL beads at three different pH values, and elution from the beads using hot SDS/DTT. The protein composition of CPLL eluates captured at pH 4, 7, and 9 was compared with the corresponding pH controls. In total, 1,704 proteins were detected. A total of 1,192 proteins were identified in control samples, whereas 512 (43%) additional proteins were found exclusively after treatment with CPLL at three different pH values.

Interestingly, for Arabidopsis leaf extracts, ProteoMiner performed best at pH 7 and 9, whereas only 34 proteins were exclusively detected at pH 4 (data not shown). In contrast, CPLL beads were most effective at pH 4 and 7 with spinach leaf extracts, whereas there was almost no pH effect in coconut (Cocos nucifera) milk (Fasoli et al., 2011a; D’Amato et al., 2012). These results imply that for each experimental system, the most effective pH value(s) must be determined.

In spinach leaf extracts, CPLL caused 18% loss and 79% gain of proteins compared with control samples, whereas for coconut milk, the loss was 78% and the gain was 124% (Fasoli et al., 2011a; D’Amato et al., 2012). In animal and human samples, CPLL was even more effective, with up to 500% additional proteins captured by the beads (Di Girolamo et al., 2011). However, in several of these publications, appropriate pH controls were missing, because CPLL-treated samples adjusted to different pH values were only compared with crude extracts (Di Girolamo et al., 2011; Fasoli et al., 2011a, 2011b; D’Amato et al., 2012). Comparing a single pH 7 control with three ProteoMiner eluates at pH 4, 7, and 9, we obtained results very similar to those reported for spinach, namely, 16% loss and 71% gain (Supplemental Fig. S2), suggesting that ProteoMiner-specific effects were overestimated without correct pH controls.

ProteoMiner-dependent enrichment of protein functional categories was investigated by using Gene Ontology (GO) terms for comparison of the protein sets from control- and ProteoMiner-treated samples (Supplemental Table S5). As recently described for latex proteins of Hevea brasiliensis (D’Amato et al., 2010), CPLL beads captured preferentially proteins involved in translation, such as aminoacyl-tRNA ligases (e.g. molecular function GO:0004815, Asp-tRNA ligase activity; GO:0004830, Trp-tRNA ligase activity) and ribosomal or related proteins (e.g. molecular function GO:0008312, 7S RNA binding). Our data also revealed that ProteoMiner had a high affinity to proteins functioning in protein transport to cellular compartments or organelles (e.g. biological process GO:0006886, intracellular protein transport; GO:0006888, endoplasmic reticulum-to-Golgi vesicle-mediated transport; GO:0045038, protein import into chloroplast thylakoid membrane). Significantly, 15 proteins of the vesicle-mediated transport system (GO:0016192) were identified after ProteoMiner treatment, but only three proteins of this functional category were found in control samples (Supplemental Table S5).

In sum, the CPLL effect is strongly dependent on the experimental system, probably including some plant-specific complications. However, once established, it is a very useful tool for the depletion of high-abundance proteins. Additionally, the detectable proteome can be extended by about 40%, and ProteoMiner might be a valuable tool for the isolation of proteins involved in translation and (vesicle-mediated) protein transport.

Application of CPLL to Phloem Exudates from Pumpkin

Cucurbitaceae species including pumpkin are model plants for phloem biochemistry, because exudates of the unique EFP can be easily collected from cut petioles and stems (Van Bel and Gaupels, 2004; Atkins et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2012). The EFP is a unique feature of the Cucurbitaceae (Turgeon and Oparka, 2010; Atkins et al., 2011). In contrast to the fascicular phloem, the EFP does not build effective callose plugs upon wounding, which allows for the sampling of large volumes (50–200 µL plant−1) of spontaneously exuding phloem sap from cut stems and petioles (Van Bel and Gaupels, 2004; Lin et al., 2009; Turgeon and Oparka, 2010). Sugar concentrations in pumpkin phloem exudates are low, implying that the EFP of cucurbits does not function in assimilate transport but rather might be involved in defense and (systemic) signaling (Walz et al., 2004; Zhang et al., 2010). Due to the easy sampling and high protein concentrations of 25 to 50 µg µL−1, cucurbits were frequently used for studying phloem proteins (Atkins et al., 2011). However, proteomic analyses by 2D electrophoresis led to the identification of less than 100 phloem proteins (Walz et al., 2004; Cho et al., 2010; Malter and Wolf, 2011). In these studies, one major pitfall was precipitation of the redox-sensitive PP1 (phloem filament protein) and PP2 (phloem lectin) in the isoelectric focusing, which caused massive streaking and loss of spots in the second dimension (Walz et al., 2004; Malter and Wolf, 2011). These two proteins account for more than 80% of the total protein content, and their gelation during sample preparation under oxidizing conditions is a general problem in downstream applications including MS. Therefore, we tested if CPLL could be used for fast and convenient reduction of PP1/PP2 amounts as well as the enrichment of low-abundance phloem proteins overlooked to this point.

Recently, 1,121 phloem proteins were identified in a groundbreaking proteomic approach (Lin et al., 2009). Protein extracts from as much as 30 mL of pumpkin phloem exudates were fractionated by anion- and cation-exchange chromatography. Afterward, proteins were separated by 1D-SDS-PAGE and analyzed by 345 MS runs. The detected proteins most likely represent the vast bulk of the total protein pool present in pumpkin phloem exudates (Lin et al., 2009). However, tedious fractionation procedures are not feasible if only low sample volumes are available or many samples must be analyzed in parallel. Therefore, a down-scaled protocol affording minimal hands-on time and preparation steps was established for the prefractionation of pumpkin phloem samples by CPLL. A total of 120 µL of phloem exudate (3 mg of protein content), which can usually be sampled from a single 4- to 5-week-old plant, was used as starting material. Proteins were alkylated with iodoacetamide for preventing gelation of PP1 and PP2. After gel filtration, ProteoMiner beads were added and incubated for 2 h. Unbound proteins were removed by extensive washing, and the captured proteins were eluted at 95°C with Laemmli buffer containing SDS and β-mercaptoethanol.

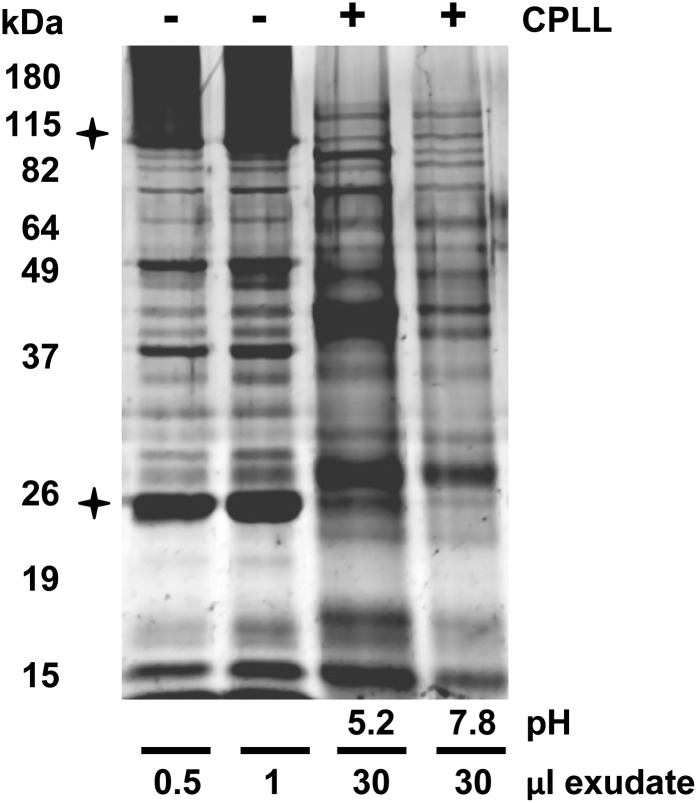

In a first experiment, two 120-µL aliquots of the same sample pool were adjusted to pH 5.2 and 7.8. A higher pH was not tested, because PP1 and PP2 precipitate at their pI values close to pH 9. After application of ProteoMiner beads, the levels of high-abundance proteins such as PP1 (95 kD) and PP2 (24 kD) were strongly reduced, whereas low- to moderate-abundance proteins were increased in band intensity, as visualized by 1D-SDS-PAGE (Fig. 6). The two pH values resulted in only minor changes in protein pattern, but the total protein amount was somewhat higher at pH 5.2. Similarly, it has been reported for coconut milk that the pH did not significantly influence the CPLL performance (D’Amato et al., 2012), although this was in contrast to our own results with Arabidopsis leaf extracts and to previous findings in spinach leaves and almond (Prunus dulcis) milk (Fasoli et al., 2011a, 2011b). The reason for these inconsistent results is unclear but might be related to plant-specific differences in secondary metabolite content (D’Amato et al., 2012). In sum, this experiment demonstrated that major phloem proteins, which might interfere with downstream analyses, were strongly depleted, whereas low- to moderate-abundance proteins were enriched.

Figure 6.

Analysis of CPLL fractionation of pumpkin phloem proteins. Phloem crude extracts and CPLL fractions (pH 5.2 and 7.8) were separated by 1D-SDS-PAGE. Loaded CPLL eluates were equivalent to 30 µL of phloem exudate. The two major phloem proteins PP1 (96 kD) and PP2 (24 kD) are marked with stars.

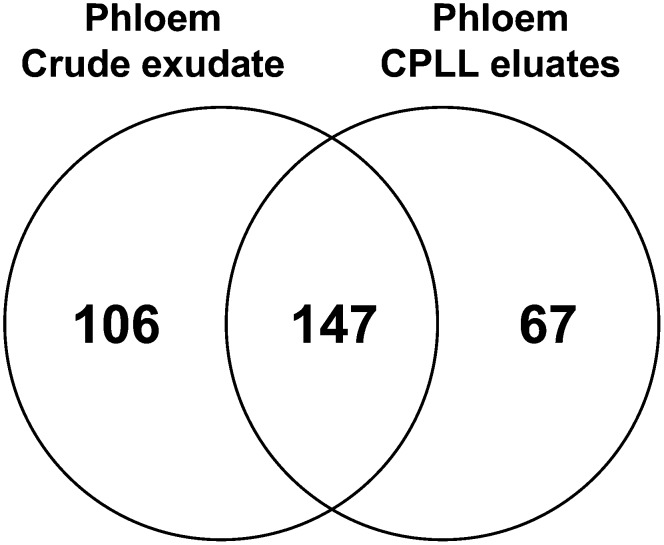

Next, we investigated the application of CPLL beads in phloem proteomics. We used 1,080 µL of ProteoMiner-treated samples and 27 µL of control phloem samples and analyzed the extracts in 36 MS runs. Thus, in comparison with Lin et al. (2009), our protocol for phloem proteomics afforded less than 4% of starting material, 10% of MS runs, and was overall more time and cost effective. While Lin et al. (2009) employed elaborate methods for an exploratory genome study, the procedure presented here is compatible with high-throughput approaches. Altogether, 320 proteins could be identified, of which 67 proteins were detected only in ProteoMiner-treated samples (Fig. 7; Supplemental Table S6). Interestingly, 106 proteins were found only in untreated control exudates. Hence, as in leaf extracts of Arabidopsis, the employment of CPLL beads caused a shift rather than an increase in the detectable proteome fraction.

Figure 7.

Comparison of the number of identified proteins in crude phloem exudates and CPLL-treated exudates of pumpkin. LC-MS/MS analyses led to the identification of 320 phloem proteins, of which 253 proteins were found in untreated control samples. However, 67 additional proteins could be exclusively detected by using CPLL beads.

After mapping 305 of the 320 phloem proteins to the cucumber (Cucumis sativus) genome for reference (www.icugi.org; version 1 of the cucumber genome; Huang et al., 2009), we found a 73% (224) overlap with pumpkin phloem proteins previously discovered by the group of W.J. Lucas (Huang et al., 2009; Lin et al., 2009; Supplemental Table S6). This result indicates that the current phloem databases might already cover most of the pumpkin extrafascicular proteins. However, 27% (81 proteins) of our data set represent new phloem proteins (Supplemental Table S6), of which 24 could only be revealed by the application of ProteoMiner beads (Table III). In the past, enucleate sieve elements forming the sieve tubes were thought to be devoid of the protein translation machinery. Our data support the notion of Lin et al. (2009) that many phloem proteins function in transcription and translation, because eight of the 24 phloem proteins captured exclusively by ProteoMiner were related to these functional categories.

Table III. New phloem proteins of pumpkin identified by utilizing CPLL technology.

MW, Molecular mass in kD.

| Function | Accession No.a |

MW | Unique Peptides | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICuGI | JGI | |||

| Transport processes | ||||

| Tubulin | Csa000342 | Cucsa.258870 | 53 | 2 |

| Adaptin | Csa000894 | Cucsa.285980 | 96 | 3 |

| Cofilin/tropomyosin-type actin-binding protein | Csa001107 | Cucsa.053580 | 17 | 3 |

| Vacuole-sorting protein SNF7 | Csa001768 | Cucsa.288610 | 25 | 2 |

| Nuclear pore complex protein Nup93 | Csa002377 | Cucsa.338210 | 54 | 3 |

| Regulator of Vps4 activity in the MVB pathway | Csa005596 | Cucsa.365760 | 65 | 2 |

| Dynamin | Csa009772 | Cucsa.237630 | 100 | 6 |

| Actin binding | Csa012435 | Cucsa.165810 | 47 | 2 |

| Snare protein synaptobrevin ykt6 | Csa016430 | Cucsa.350890 | 23 | 2 |

| Adaptin | Csa019149 | Cucsa.109670 | 99 | 3 |

| Importin, Ran-binding protein 6 | Csa019530 | Cucsa.334860 | 123 | 2 |

| Adaptin | Csa021291 | Cucsa.240490 | 98 | 6 |

| Dynamin | Csa021655 | Cucsa.280120 | 69 | 2 |

| Protein synthesis and degradation | ||||

| Apoptosis inhibitory protein 5 (AIP5) | Csa000645 | Cucsa.046470 | 38 | 2 |

| U1 small nuclear ribonucleoprotein | Csa000767 | Cucsa.048580 | 30 | 3 |

| RNA-binding protein, RNA recognition motif | Csa006440 | Cucsa.055310 | 22 | 2 |

| Translation initiation factor activity | Csa007054 | Cucsa.200090 | 30 | 2 |

| Structural constituent of ribosome | Csa007533 | Cucsa.161150 | 23 | 3 |

| Ubiquitin | Csa015756 | Cucsa.323030 | 59 | 2 |

| Ribosomal protein L16p/L10e | Csa017251 | Cucsa.228420 | 25 | 2 |

| U1 small nuclear ribonucleoprotein C | Csa019223 | Cucsa.084690 | 21 | 2 |

| Others | ||||

| Calmodulin | Csa002960 | Cucsa.094740 | 17 | 2 |

| Casein kinase | Csa009196 | Cucsa.117110 | 53 | 5 |

| Unknown | Csa020629 | Cucsa.049570 | 17 | 2 |

Moreover, 13 of the 24 phloem proteins in Table III are involved in transport processes, giving rise to the idea that, at least in the EFP of cucurbits, not only the companion cells but also sieve elements are able to synthesize, process, and transport proteins. These data also imply that membrane systems such as the Golgi apparatus and endoplasmic reticulum are present within sieve tubes. As in Arabidopsis leaf extracts, ProteoMiner was particularly effective in capturing proteins related to transport processes, including general protein transport, vesicle transport, and vacuolar targeting. Altogether, 26 of 67 proteins identified only in the CPLL fraction were related to transport processes (data not shown). An additional 25 proteins were functionally annotated to protein synthesis and degradation (data not shown).

The collection of phloem exudates from cut stems and petioles imposes the risk of contaminations from nonphloem tissues. The large subunit of Rubisco is often used for assessing such contaminations, because it is a major enzyme in tissues surrounding the phloem. In the past, only three and seven unique peptides of Rubisco were detected in phloem exudates of rape (Brassica napus) and pumpkin, respectively, suggesting that the phloem samples were essentially contamination free (Giavalisco et al., 2006; Lin et al., 2009). In our study, three unique peptides were identified in control samples, but after application of ProteoMiner, the number of unique peptides of Rubisco increased to five (Supplemental Table S6). Thus, ProteoMiner does readily enrich low-abundance contaminating proteins such as Rubisco; therefore, proteins identified by using this tool must be carefully verified for their phloem origin.

CONCLUSION

The CPLL technology is a widely used technique within the human/animal field and was recently applied to some plant-derived products such as spinach leaves from the market, coconut milk, and almond milk (Fasoli et al., 2011a, 2011b; D’Amato et al., 2012). Here, we established the CPLL technology in plant research, performing in-depth analyses of the CPLL-fractionated proteins from Arabidopsis leaf extracts and pumpkin phloem exudates by 2D-DIGE and LC-MS/MS.

The two tested experimental systems are very disparate. On the one hand, extracts from disrupted leaf cells contain mainly proteins involved in photosynthesis and carbohydrate metabolism. On the other hand, in samples from photosynthetically inactive sieve elements, many proteins are related to defense, transport, and protein synthesis. Additionally, the metabolite composition is very different between both plant systems. Therefore, it is remarkable that ProteoMiner had similar effects in both plant samples. CPLL proved to be an effective tool for diminishing high-abundance proteins such as Rubisco in leaf extracts and PP1 and PP2 in pumpkin phloem exudates. These major proteins interfere with downstream applications such as 2D electrophoresis and western-blot analysis, because they mask low-abundance proteins, and particularly PP1/PP2 tend to gelate upon oxidation. A significant feature of ProteoMiner, as revealed by 1D and 2D electrophoresis, was that spots or bands representing less abundant and previously undetectable proteins were enriched after CPLL treatment. As a consequence, this technology facilitated the identification of additional proteins by LC-MS/MS. However, the efficacy of ProteoMiner in extending the proteome was dependent on the protocol used. Following the ProteoMiner instruction manual, the 2D pattern changed considerably, but only around 15% new proteins (based on the total number of identified proteins) could be identified. However, when an optimized protocol published by the group of Righetti (Di Girolamo et al., 2011) was employed, more than 40% additional proteins could be identified with the ProteoMiner technology. Noteworthy, even with the optimized protocol, 22% of the proteins present in control extracts were lost due to CPLL treatment. Such a “loss of protein” has been observed previously (Castagna et al., 2005; Thulasiraman et al., 2005) and probably occurs due to following reasons: (1) some proteins do not have binding partners in the hexapeptide library; (2) weak interactions between hexapeptides and proteins can be broken during washing of the columns; and (3) in plant samples, secondary metabolites might interfere with the binding and elution of proteins, a problem less encountered in human/animal samples.

Importantly, in most experimental approaches, including ours, the ProteoMiner technology did not extend but rather shifted the detectable proteome. A significant increase in the detected proteome was achieved only when results of both crude extracts and ProteoMiner eluates were combined. This way, ProteoMiner increased the number of identified proteins by a maximum of 43% in the leaf experiment and 26% in the phloem experiment. In other papers, the application of CPLL beads to spinach leaves, coconut milk, and almond milk led to a 79% to 124% increase of the detectable proteomes (Fasoli et al., 2011a, 2011b; D’Amato et al., 2012). However, the authors compared three CPLL samples adjusted to different pH values (pH 4, 7, and 9) with a single nontreated control sample (pH 7). In contrast, we compared control samples and CPLL-treated samples both adjusted to pH 4, 7, and 9. Analysis of our data showed that adjustment of the samples to different pH values functions as a kind of prefractionation procedure resulting in a considerable shift in the proteome independent of ProteoMiner application. Therefore, in the past, the ProteoMiner effects on the total protein count might have been often overestimated. Only by using appropriate pH controls were we able to provide a realistic figure for the specific contribution of ProteoMiner to the proteomic investigation of Arabidopsis leaf extracts and pumpkin phloem exudates. In sum, ProteoMiner is a time- and cost-effective tool with many potential applications in plant protein biochemistry. ProteoMiner is highly effective in reducing high-abundance proteins that might interfere with downstream analyses. It can also be used as an additional easy-to-apply fractionation technique in exploratory proteomics. Targeting a single low-abundance protein of interest, the CPLL technology might be helpful for enriching such proteins, for example, if antibodies for immunoprecipitation are not available. In any case, binding of the candidate protein to hexapeptides in the library must be carefully tested. Last but not least, preferred binding of ProteoMiner beads to proteins of the vesicle transport or translation machinery could facilitate research into these cellular processes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Protein Extraction and Treatment with CPLL

For protocol I, 75 g of frozen plant material was ground under liquid nitrogen and suspended in 300 mL of extraction buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 50 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 0.1% β-mercaptoethanol, and 1× Complete protease inhibitor, EDTA free). Five percent (w/v) polyvinylpolypyrrolidone was added, and the suspension was stirred at 4°C for 30 min. After two centrifugation steps at 4°C (10 min, 4,500g and 15 min, 34,000g), protein was precipitated from the supernatant at 4°C overnight using ammonium sulfate at 95% saturation. After 15 min of centrifugation at 34,000g, the pellet was resuspended in 12 mL of phosphate-buffered saline and protease inhibitor (Complete, EDTA free; Roche). The protein solution was desalted using a PD10 size-exclusion column (GE Healthcare) according to the manual. Treatment of extracts with ProteoMiner was done according to the manual (Bio-Rad) with minor modifications. Because of a lower protein concentration than recommended, a minimum of 10 mg of protein was added to the columns in a volume of 1 mL. Incubation was done at room temperature overnight on a shaker. Complete EDTA-free protease inhibitor (2×) was used during incubation. Elution was done according to the manual with 8 m urea and 2% CHAPS. For protocol II, 5 g of frozen plant material was ground under liquid nitrogen and suspended in 10 mL of extraction buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 50 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, and 0.1% β-mercaptoethanol). The suspension was centrifuged for 15 min (34,000g, 4°C). The supernatant was subjected to buffer exchange using PD10 columns according to the manual. The PD10 columns were equilibrated and eluted using the following buffers: 25 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.0, 25 mm Tris-HCl, pH 9.0, or 25 mm acetate buffer, pH 4.0. An amount (3.5 mL) of each eluate (pH 4, 7, or 9) was extracted using the batch protocol with 50 μL of equilibrated ProteoMiner slurry. Incubation was done for 3 h at room temperature using an overhead shaker. The CPLL beads were washed two times with 5 mL of the corresponding buffer. The CPLL beads were eluted using 2× 50 μL of hot SDS-DTT solution (4% SDS, 50 mm DTT, 95°C).

2D-DIGE

Fluorescent labeling of protein was done using the Ettan DIGE System (GE Healthcare) according to the manual. Prior to labeling, protein concentration was measured and the required amount of protein (50 µg) was purified using the 2D Cleanup Kit. Four replicates of samples before and after CPLL treatment and an internal standard were labeled, including a dye swap. Isoelectric focusing was done using an IPGphor3 with Immobiline dry strips (24 cm, pH 4–7) and the standard IPGphor3 program for isoelectric focusing of gradients of pH 4 to 7. PAGE was done using an Ettan DALT 6 electrophoresis chamber according to the manufacturer’s instructions. 2D-DIGE gels were scanned using a Typhoon variable mode imager. Analysis of scanned gels was done using DeCyder software. For spot finding, matching, and statistical analysis, standard parameters recommended by the manufacturer were used. Changes in protein amounts were statistically detected by ANOVA (P < 0.05) and the application of false discovery rate correction.

Infection of Arabidopsis with Pseudomonas syringae DC3000

Four-week-old Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) ecotype Columbia plants were infected according to Katagiri et al. (2002). Briefly, the plants were grown in pots covered by a fine mesh. Plants were infected by vacuum infiltration with virulent P. syringae DC3000 at 10−6 colony-forming units mL−1 buffer (10 mm MgCl2, 0.004% Silwet). Whole rosettes were harvested 24 h after infection and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen for proteomic analyses. To determine bacterial growth, surface-sterilized leaf discs were homogenized in 1 mL of 10 mm MgCl2 and different dilutions were plated on King’s B medium. After incubating the plates at 28°C for 2 d, the colonies were counted.

CPLL Treatment and Analysis of Pumpkin Phloem Exudates

Phloem samples were collected from cut petioles and stems of 4- to 5-week-old pumpkin (Cucurbita maxima ‘Gele Centenaar’) plants as described previously (Lin et al., 2009). A total of 120 µL of pumpkin phloem exudate (25 mg protein mL−1) was mixed with the same volume of phloem buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.8, 0.1% β-mercaptoethanol; McEuen and Hill, 1982). Redox-sensitive Cys residues of PP1/PP2 were alkylated by adding 25 mm (final concentration) iodoacetamide. Afterward, β-mercaptoethanol and iodoacetamide were removed by gel filtration and proteins were collected in 120 µL of phloem buffer without β-mercaptoethanol. In one experiment, a sodium acetate buffer (100 mm sodium acetate/acetic acid, pH 5.2) was used for elution. ProteoMiner beads were applied according to the manual. The final protein amount was 3 mg at a concentration of 25 mg mL−1. After washing, proteins were eluted from beads by twice applying 50 µL of commercial 4× Laemmli buffer (Roth) at 95°C.

From every plant, 120 µL of the collected phloem sap was used for ProteoMiner experiments and 3 µL served as a control, which was reduced, alkylated, and gel filtrated but not treated with ProteoMiner beads. For SDS-PAGE, Laemmli buffer was added to control phloem exudates whereas ProteoMiner eluates were directly loaded on a 12% SDS-PAGE gel. LC-MS/MS analyses were done in triplicate. For each triplicate assay, three ProteoMiner eluates or corresponding control exudates were combined and proteins were precipitated using the 2D Cleanup Kit (GE Healthcare) and separated by SDS-PAGE. The gel was cut into six pieces per sample and analyzed by LC-MS/MS.

MS Analysis and Data Processing

For the identification of proteins, 1D-SDS-PAGE bands were cut out and samples were prepared using a MS-compatible protocol (Shevchenko et al., 1996). The digested peptides were separated by reverse-phase chromatography (PepMap, 15 cm × 75 µm i.d., 3 µm 100 Å−1 pore size; LC Packings) operated on a nano-HPLC device (Ultimate 3000; Dionex) with a nonlinear 170-min gradient using 2% acetonitrile in 0.1% formic acid in water (A) and 0.1% formic acid in 98% acetonitrile (B) as eluents with a flow rate of 250 nL min−1. The gradient settings were subsequently as follows: 0 to 140 min, 2% to 30% B; 140 to 150 min, 31% to 99% B; 151 to 160 min, hold at 99% B. The nano-HPLC device was connected to a linear quadrupole ion-trap-Orbitrap (LTQ Orbitrap XL) mass spectrometer (ThermoFisher) equipped with a nano-electrospray ionization source. The mass spectrometer was operated in the data-dependent mode to automatically switch between Orbitrap-MS and LTQ-MS/MS acquisition. Survey full-scan MS spectra (from mass-to-charge ratio 300 to 1,500) were acquired in the Orbitrap with resolution r = 60,000 at a mass-to-charge ratio of 400 (after accumulation to a target of 1,000,000 ions in the LTQ). The method used allowed sequential isolation of the most intense ions, up to 10, depending on signal intensity, for fragmentation on the linear ion trap using collisionally induced dissociation at a target value of 100,000 ions. High-resolution MS scans in the Orbitrap and tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) scans in the linear ion trap were performed in parallel. Target peptides already selected for MS/MS were dynamically excluded for 30 s. General MS conditions were as follows: electrospray voltage, 1.25 to 1.4 kV; no sheath and auxiliary gas flow. The ion selection threshold was 500 counts for MS/MS, and an activation Q value of 0.25 and activation time of 30 ms were also applied for MS/MS.

Database Searching

All MS/MS spectra were analyzed using Mascot version 2.2.06 (Matrix Science). Mascot was set up to search The Arabidopsis Information Resource (TAIR) database (13,434,913 residues, 33,410 sequences) or the National Center for Biotechnology Information P. syringae DC3000 protein database (ftp://ftp.ncbi.nih.gov/genomes/Bacteria/Pseudomonas_syringae_tomato_DC3000/) assuming the digestion enzyme trypsin with a fragment ion mass tolerance of 1 D and a parent ion tolerance of 10 ppm. Oxidation of Met and deamidation of Arg and Gln as variable modifications were specified in Mascot as variable modifications. The genome of pumpkin has not yet been sequenced; therefore, we assembled a database for phloem proteomics including among others protein sequences derived from the complete genomes of the Cucurbitaceae species cucumber (Cucumis sativus) and Citrullus lanatus. We used OrthoMCL software version 1.4 (Li et al., 2003) with default parameters (inflation, 1.5; BLASTP e-value cutoff, 10e-05) to cluster the protein sequences annotated on the complete genome sequences of cucumber (Joint Genome Institute [JGI]; www.phytozome.net/cucumber.php, genome release 1), Arabidopsis (TAIR10 release; www.arabidopsis.org), and C. lanatus (International Cucurbit Genomics Initiative [ICuGI] genome version 1; www.icugi.org). Of the resulting 16,877 gene groups, protein sequences were extracted and a high-confidence phloem database was created containing a total of 25,657 sequences.

Additional protein sequences from the National Center for Biotechnology Information Cucurbitaceae database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?db=protein&cmd=Search&dopt=DocSum&term=txid3650[Organism%3Aexp) and 800 cucumber homologs (ICuGI accessions) of pumpkin phloem proteins from Supplemental Table S18 of Huang et al. (2009) were added. Phloem proteins identified by searching against our homemade protein database were mapped to the JGI and ICuGI cucumber genome accessions using BLASTP with an e-value cutoff of 10e-05 and required more than 90% sequence identity for at least 70% sequence coverage. With nonmapped protein sequences, an additional BLASTP search against the ICuGI genome database was performed, choosing a threshold P value of 1e-30. This way, 309 of 320 identified phloem proteins could be annotated to ICuGI identifiers, which were then used for comparison of our data with Supplemental Table S18 of Huang et al. (2009).

Criteria for Protein Identification

Scaffold (version Scaffold_2_02_03; Proteome Software) was used to validate MS/MS-based peptide and protein identifications. Peptide identifications were accepted if they could be established at greater than 95.0% probability as specified by the Peptide Prophet algorithm (Keller et al., 2002). Protein identifications were accepted if they could be established at greater than 99.0% probability and contained at least two identified peptides. Protein probabilities were assigned by the Protein Prophet algorithm (Nesvizhskii et al., 2003). Proteins that contained similar peptides and could not be differentiated based on MS/MS analysis alone were grouped to satisfy the principles of parsimony.

GO Enrichment Analysis

We downloaded GO terms for the gene annotation of Arabidopsis from TAIR. Only GO terms of the categories “molecular function” and “biological process” were evaluated. The GOstats R package from Bioconductor (http://www.bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/GOstats.html) was used for analyzing the GO terms of the 512 ProteoMiner-specific proteins and the 1,192 proteins derived from the crude extracts shown in Figure 5 and Supplemental Table S4. Supplemental Table S5 lists the GO terms that were significantly (P < 0.05) overrepresented in these protein sets as compared with the TAIR10 database.

Supplemental Data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Figure S1. pH effect on CPLL performance.

Supplemental Figure S2. pH 7 control versus CPLL capture at pH 4, 7, and 9.

Supplemental Table S1. Identified Arabidopsis proteins using CPLL, protocol 1.

Supplemental Table S2. Identified Arabidopsis proteins in infected leaves.

Supplemental Table S3. Identified P. syringae proteins in infected leaves.

Supplemental Table S4. Identified Arabidopsis proteins using CPLL, protocol 2.

Supplemental Table S5. Enriched GO terms after CPLL application.

Supplemental Table S6. Identified pumpkin phloem proteins.

Supplementary Material

Glossary

- CPLL

combinatorial hexapeptide ligand libraries

- 2D

two-dimensional

- 1D

one-dimensional

- 2D-DIGE

two-dimensional fluorescence difference gel electrophoresis

- LC-MS/MS

liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry

- DTT

dithiothreitol

- CV

coefficient of variation

- ABC

ATP-binding cassette

- EFP

extrafascicular phloem

- MS

mass spectrometry

- MS/MS

tandem mass spectrometry

- ICuGI

International Cucurbit Genomics Initiative

- TAIR

The Arabidopsis Information Resource

- JGI

Joint Genome Institute

- GO

Gene Ontology

References

- Ardales E, Moon S-J, Park DS, Sr, Byun M-O, Noh TH. (2009) Inactivation of argG, encoding argininosuccinate synthetase from Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae, is involved in bacterial growth and virulence in planta. Can J Plant Pathol 31: 368–374 [Google Scholar]

- Atkins CA, Smith PM, Rodriguez-Medina C. (2011) Macromolecules in phloem exudates: a review. Protoplasma 248: 165–172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachi A, Simó C, Restuccia U, Guerrier L, Fortis F, Boschetti E, Masseroli M, Righetti PG. (2008) Performance of combinatorial peptide libraries in capturing the low-abundance proteome of red blood cells. 2. Behavior of resins containing individual amino acids. Anal Chem 80: 3557–3565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boschetti E, Lomas L, Citterio A, Righetti PG. (2007) Romancing the “hidden proteome,” Anno Domini two zero zero seven. J Chromatogr A 1153: 277–290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boschetti E, Righetti PG. (2008a) Hexapeptide combinatorial ligand libraries: the march for the detection of the low-abundance proteome continues. Biotechniques 44: 663–665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boschetti E, Righetti PG. (2008b) The ProteoMiner in the proteomic arena: a non-depleting tool for discovering low-abundance species. J Proteomics 71: 255–264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boschetti E, Righetti PG. (2009) The art of observing rare protein species in proteomes with peptide ligand libraries. Proteomics 9: 1492–1510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buell CR, Joardar V, Lindeberg M, Selengut J, Paulsen IT, Gwinn ML, Dodson RJ, Deboy RT, Durkin AS, Kolonay JF, et al. (2003) The complete genome sequence of the Arabidopsis and tomato pathogen Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100: 10181–10186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buettner JA, Dadd CA, Baumbach GA, Masecar BL, Hammond DJ. (1996) Chemically derived peptide libraries: a new resin and methodology for lead identification. Int J Pept Protein Res 47: 70–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castagna A, Cecconi D, Sennels L, Rappsilber J, Guerrier L, Fortis F, Boschetti E, Lomas L, Righetti PG. (2005) Exploring the hidden human urinary proteome via ligand library beads. J Proteome Res 4: 1917–1930 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho WK, Chen XY, Rim Y, Chu H, Kim S, Kim SW, Park ZY, Kim JY. (2010) Proteome study of the phloem sap of pumpkin using multidimensional protein identification technology. J Plant Physiol 167: 771–778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corthals GL, Wasinger VC, Hochstrasser DF, Sanchez JC. (2000) The dynamic range of protein expression: a challenge for proteomic research. Electrophoresis 21: 1104–1115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Amato A, Bachi A, Fasoli E, Boschetti E, Peltre G, Sénéchal H, Righetti PG. (2009) In-depth exploration of cow’s whey proteome via combinatorial peptide ligand libraries. J Proteome Res 8: 3925–3936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Amato A, Bachi A, Fasoli E, Boschetti E, Peltre G, Sénéchal H, Sutra JP, Citterio A, Righetti PG. (2010) In-depth exploration of Hevea brasiliensis latex proteome and “hidden allergens” via combinatorial peptide ligand libraries. J Proteomics 73: 1368–1380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Amato A, Fasoli E, Kravchuk AV, Righetti PG. (2011) Mehercules, adhuc Bacchus! The debate on wine proteomics continues. J Proteome Res 10: 3789–3801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Amato A, Fasoli E, Righetti PG. (2012) Harry Belafonte and the secret proteome of coconut milk. J Proteomics 75: 914–920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Ambrosio C, Arena S, Scaloni A, Guerrier L, Boschetti E, Mendieta ME, Citterio A, Righetti PG. (2008) Exploring the chicken egg white proteome with combinatorial peptide ligand libraries. J Proteome Res 7: 3461–3474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Girolamo F, Boschetti E, Chung MC, Guadagni F, Righetti PG. (2011) “Proteomineering” or not? The debate on biomarker discovery in sera continues. J Proteomics 74: 589–594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farinazzo A, Restuccia U, Bachi A, Guerrier L, Fortis F, Boschetti E, Fasoli E, Citterio A, Righetti PG. (2009) Chicken egg yolk cytoplasmic proteome, mined via combinatorial peptide ligand libraries. J Chromatogr A 1216: 1241–1252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fasoli E, Aldini G, Regazzoni L, Kravchuk AV, Citterio A, Righetti PG. (2010a) Les maîtres de l’orge: the proteome content of your beer mug. J Proteome Res 9: 5262–5269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fasoli E, D'Amato A, Citterio A, Righetti PG. (2012) Ginger Rogers? No, ginger ale and its invisible proteome. J Proteomics 75: 1960–1965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fasoli E, D’Amato A, Kravchuk AV, Boschetti E, Bachi A, Righetti PG. (2011a) Popeye strikes again: the deep proteome of spinach leaves. J Proteomics 74: 127–136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fasoli E, D’Amato A, Kravchuk AV, Citterio A, Righetti PG. (2011b) In-depth proteomic analysis of non-alcoholic beverages with peptide ligand libraries. I. Almond milk and orgeat syrup. J Proteomics 74: 1080–1090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fasoli E, Farinazzo A, Sun CJ, Kravchuk AV, Guerrier L, Fortis F, Boschetti E, Righetti PG. (2010b) Interaction among proteins and peptide libraries in proteome analysis: pH involvement for a larger capture of species. J Proteomics 73: 733–742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fito-Boncompte L, Chapalain A, Bouffartigues E, Chaker H, Lesouhaitier O, Gicquel G, Bazire A, Madi A, Connil N, Véron W, et al. (2011) Full virulence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa requires OprF. Infect Immun 79: 1176–1186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fones H, Preston GM. (2012) Reactive oxygen and oxidative stress tolerance in plant pathogenic Pseudomonas. FEMS Microbiol Lett 327: 1–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fröhlich A, Lindermayr C. (2011) Deep insights into the plant proteome by pretreatment with combinatorial hexapeptide ligand libraries. J Proteomics 74: 1182–1189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furka A, Sebestyén F, Asgedom M, Dibó G. (1991) General method for rapid synthesis of multicomponent peptide mixtures. Int J Pept Protein Res 37: 487–493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garbom S, Forsberg A, Wolf-Watz H, Kihlberg BM. (2004) Identification of novel virulence-associated genes via genome analysis of hypothetical genes. Infect Immun 72: 1333–1340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giavalisco P, Kapitza K, Kolasa A, Buhtz A, Kehr J. (2006) Towards the proteome of Brassica napus phloem sap. Proteomics 6: 896–909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerrier L, Claverol S, Finzi L, Paye F, Fortis F, Boschetti E, Housset C. (2007a) Contribution of solid-phase hexapeptide ligand libraries to the repertoire of human bile proteins. J Chromatogr A 1176: 192–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerrier L, Claverol S, Fortis F, Rinalducci S, Timperio AM, Antonioli P, Jandrot-Perrus M, Boschetti E, Righetti PG. (2007b) Exploring the platelet proteome via combinatorial, hexapeptide ligand libraries. J Proteome Res 6: 4290–4303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerrier L, Thulasiraman V, Castagna A, Fortis F, Lin SH, Lomas L, Righetti PG, Boschetti E. (2006) Reducing protein concentration range of biological samples using solid-phase ligand libraries. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci 833: 33–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo W, Cui YP, Li YR, Che YZ, Yuan L, Zou LF, Zou HS, Chen GY. (2012) Identification of seven Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzicola genes potentially involved in pathogenesis in rice. Microbiology 158: 505–518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ha UH, Wang Y, Jin S. (2003) DsbA of Pseudomonas aeruginosa is essential for multiple virulence factors. Infect Immun 71: 1590–1595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S, Li R, Zhang Z, Li L, Gu X, Fan W, Lucas WJ, Wang X, Xie B, Ni P, et al. (2009) The genome of the cucumber, Cucumis sativus L. Nat Genet 41: 1275–1281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hueck CJ. (1998) Type III protein secretion systems in bacterial pathogens of animals and plants. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 62: 379–433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim YM, Kerr AR, Silva NA, Mitchell TJ. (2005) Contribution of the ATP-dependent protease ClpCP to the autolysis and virulence of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Infect Immun 73: 730–740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jittawuttipoka T, Buranajitpakorn S, Vattanaviboon P, Mongkolsuk S. (2009) The catalase-peroxidase KatG is required for virulence of Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris in a host plant by providing protection against low levels of H2O2. J Bacteriol 191: 7372–7377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katagiri F, Thilmony R, He S. (2002) The Arabidopsis thaliana-Pseudomonas syringae interaction. The Arabidopsis Book 1: e0039, doi/10.1199/tab.0039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keidel EM, Ribitsch D, Lottspeich F. (2010) Equalizer technology: equal rights for disparate beads. Proteomics 10: 2089–2098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller A, Nesvizhskii AI, Kolker E, Aebersold R. (2002) Empirical statistical model to estimate the accuracy of peptide identifications made by MS/MS and database search. Anal Chem 74: 5383–5392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemner JM, Liang X, Nester EW. (1997) The Agrobacterium tumefaciens virulence gene chvE is part of a putative ABC-type sugar transport operon. J Bacteriol 179: 2452–2458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurth DG, Gago GM, de la Iglesia A, Lyonnet BB, Lin TW, Morbidoni HR, Tsai SC, Gramajo H. (2009) ACCase 6 is the essential acetyl-CoA carboxylase involved in fatty acid and mycolic acid biosynthesis in mycobacteria. Microbiology 155: 2664–2675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam KS, Salmon SE, Hersh EM, Hruby VJ, Kazmierski WM, Knapp RJ. (1991) A new type of synthetic peptide library for identifying ligand-binding activity. Nature 354: 82–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamarche MG, Wanner BL, Crépin S, Harel J. (2008) The phosphate regulon and bacterial virulence: a regulatory network connecting phosphate homeostasis and pathogenesis. FEMS Microbiol Rev 32: 461–473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G, Nallamilli BR, Tan F, Peng Z. (2008) Removal of high-abundance proteins for nuclear subproteome studies in rice (Oryza sativa) endosperm. Electrophoresis 29: 604–617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Schenk A, Srivastava A, Zhurina D, Ullrich MS. (2006) Thermo-responsive expression and differential secretion of the extracellular enzyme levansucrase in the plant pathogenic bacterium Pseudomonas syringae pv. glycinea. FEMS Microbiol Lett 265: 178–185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Stoeckert CJ, Jr, Roos DS. (2003) OrthoMCL: identification of ortholog groups for eukaryotic genomes. Genome Res 13: 2178–2189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin MK, Lee YJ, Lough TJ, Phinney BS, Lucas WJ. (2009) Analysis of the pumpkin phloem proteome provides insights into angiosperm sieve tube function. Mol Cell Proteomics 8: 343–356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu P, Wood D, Nester EW. (2005) Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase is an acid-induced, chromosomally encoded virulence factor in Agrobacterium tumefaciens. J Bacteriol 187: 6039–6045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malter D, Wolf S. (2011) Melon phloem-sap proteome: developmental control and response to viral infection. Protoplasma 248: 217–224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEuen AR, Hill HAO. (1982) Superoxide, hydrogen peroxide, and the gelling of phloem sap from Cucurbita pepo. Planta 154: 295–297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNairn E, Ni Bhriain N, Dorman CJ. (1995) Overexpression of the Shigella flexneri genes coding for DNA topoisomerase IV compensates for loss of DNA topoisomerase I: effect on virulence gene expression. Mol Microbiol 15: 507–517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta A, Brasileiro AC, Souza DS, Romano E, Campos MA, Grossi-de-Sá MF, Silva MS, Franco OL, Fragoso RR, Bevitori R, et al. (2008) Plant-pathogen interactions: what is proteomics telling us? FEBS J 275: 3731–3746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mougous JD, Cuff ME, Raunser S, Shen A, Zhou M, Gifford CA, Goodman AL, Joachimiak G, Ordoñez CL, Lory S, et al. (2006) A virulence locus of Pseudomonas aeruginosa encodes a protein secretion apparatus. Science 312: 1526–1530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarre WW, Zou SB, Roy H, Xie JL, Savchenko A, Singer A, Edvokimova E, Prost LR, Kumar R, Ibba M, et al. (2010) PoxA, yjeK, and elongation factor P coordinately modulate virulence and drug resistance in Salmonella enterica. Mol Cell 39: 209–221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nesvizhskii AI, Keller A, Kolker E, Aebersold R. (2003) A statistical model for identifying proteins by tandem mass spectrometry. Anal Chem 75: 4646–4658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peck SC. (2005) Update on proteomics in Arabidopsis: where do we go from here? Plant Physiol 138: 591–599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preston GM. (2000) Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato: the right pathogen, of the right plant, at the right time. Mol Plant Pathol 1: 263–275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahme LG, Stevens EJ, Wolfort SF, Shao J, Tompkins RG, Ausubel FM. (1995) Common virulence factors for bacterial pathogenicity in plants and animals. Science 268: 1899–1902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Righetti PG, Boschetti E. (2008) The ProteoMiner and the FortyNiners: searching for gold nuggets in the proteomic arena. Mass Spectrom Rev 27: 596–608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez GM, Smith I. (2006) Identification of an ABC transporter required for iron acquisition and virulence in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Bacteriol 188: 424–430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose JK, Bashir S, Giovannoni JJ, Jahn MM, Saravanan RS. (2004) Tackling the plant proteome: practical approaches, hurdles and experimental tools. Plant J 39: 715–733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roux-Dalvai F, Gonzalez de Peredo A, Simó C, Guerrier L, Bouyssié D, Zanella A, Citterio A, Burlet-Schiltz O, Boschetti E, Righetti PG, et al. (2008) Extensive analysis of the cytoplasmic proteome of human erythrocytes using the peptide ligand library technology and advanced mass spectrometry. Mol Cell Proteomics 7: 2254–2269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiano CA, Bellows LE, Lathem WW. (2010) The small RNA chaperone Hfq is required for the virulence of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis. Infect Immun 78: 2034–2044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sen M, Shah B, Rakshit S, Singh V, Padmanabhan B, Ponnusamy M, Pari K, Vishwakarma R, Nandi D, Sadhale PP. (2011) UDP-glucose 4,6-dehydratase activity plays an important role in maintaining cell wall integrity and virulence of Candida albicans. PLoS Pathog 7: e1002384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shevchenko A, Wilm M, Vorm O, Mann M. (1996) Mass spectrometric sequencing of proteins silver-stained polyacrylamide gels. Anal Chem 68: 850–858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Si Y, Yuan F, Chang H, Liu X, Li H, Cai K, Xu Z, Huang Q, Bei W, Chen H. (2009) Contribution of glutamine synthetase to the virulence of Streptococcus suis serotype 2. Vet Microbiol 139: 80–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stitt M, Lunn J, Usadel B. (2010) Arabidopsis and primary photosynthetic metabolism: more than the icing on the cake. Plant J 61: 1067–1091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thulasiraman V, Lin S, Gheorghiu L, Lathrop J, Lomas L, Hammond D, Boschetti E. (2005) Reduction of the concentration difference of proteins in biological liquids using a library of combinatorial ligands. Electrophoresis 26: 3561–3571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turgeon R, Oparka K. (2010) The secret phloem of pumpkins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 13201–13202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Bel AJE, Gaupels F. (2004) Pathogen-induced resistance and alarm signals in the phloem. Mol Plant Pathol 5: 495–504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walz C, Giavalisco P, Schad M, Juenger M, Klose J, Kehr J. (2004) Proteomics of cucurbit phloem exudate reveals a network of defence proteins. Phytochemistry 65: 1795–1804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wharam SD, Mulholland V, Salmond GPC. (1995) Conserved virulence factor regulation and secretion systems in bacterial pathogens of plants and animals. Eur J Plant Pathol 101: 1–13 [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B, Tolstikov V, Turnbull C, Hicks LM, Fiehn O. (2010) Divergent metabolome and proteome suggest functional independence of dual phloem transport systems in cucurbits. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 13532–13537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C, Yu X, Ayre BG, Turgeon R. (2012) The origin and composition of cucurbit “phloem” exudate. Plant Physiol 158: 1873–1882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.