Executive Summary

Objective

To review the evidence on the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of balloon kyphoplasty for the treatment of vertebral compression fractures (VCFs).

Clinical Need

Vertebral compression fractures are one of the most common types of osteoporotic fractures. They can lead to chronic pain and spinal deformity. They are caused when the vertebral body (the thick block of bone at the front of each vertebra) is too weak to support the loads of activities of daily living. Spinal deformity due to a collapsed vertebral body can substantially affect the quality of life of elderly people, who are especially at risk for osteoporotic fractures due to decreasing bone mass with age. A population-based study across 12 European centres recently found that VCFs have a negative impact on health-related quality of life. Complications associated with VCFs are pulmonary dysfunction, eating disorders, loss of independence, and mental status change due to pain and the use of medications. Osteoporotic VCFs also are associated with a higher rate of death.

VCFs affect an estimated 25% of women over age 50 years and 40% of women over age 80 years. Only about 30% of these fractures are diagnosed in clinical practice. A Canadian multicentre osteoporosis study reported on the prevalence of vertebral deformity in Canada in people over 50 years of age. To define the limit of normality, they plotted a normal distribution, including mean and standard deviations (SDs) derived from a reference population without any deformity. They reported a prevalence rate of 23.5% in women and a rate of 21.5% in men, using 3 SDs from the mean as the limit of normality. When they used 4 SDs, the prevalence was 9.3% and 7.3%, respectively. They also found the prevalence of vertebral deformity increased with age. For people older than 80 years of age, the prevalence for women and men was 45% and 36%, respectively, using 3 SDs as the limit of normality.

About 85% of VCFs are due to primary osteoporosis. Secondary osteoporosis and neoplasms account for the remaining 15%. A VCF is operationally defined as a reduction in vertebral body height of at least 20% from the initial measurement. It is considered mild if the reduction in height is between 20% and 25%; moderate, if it is between 25% and 40%; and severs, if it is more than 40%. The most frequently fractured locations are the third-lower part of the thorax and the superior lumbar levels. The cervical vertebrae and the upper third of the thorax are rarely involved.

Traditionally, bed rest, medication, and bracing are used to treat painful VCFs. However, anti-inflammatory and narcotic medications are often poorly tolerated by the elderly and may harm the gastrointestinal tract. Bed rest and inactivity may accelerate bone loss, and bracing may restrict diaphragmatic movement. Furthermore, medical treatment does not treat the fracture in a way that ameliorates the pain and spinal deformity.

Over the past decade, the injection of bone cement through the skin into a fractured vertebral body has been used to treat VCFs. The goal of cement injection is to reduce pain by stabilizing the fracture. The secondary indication of these procedures is management of painful vertebral fractures caused by benign or malignant neoplasms (e.g., hemangioma, multiple myeloma, and metastatic cancer).

The Technology

Balloon kyphoplasty is a modified vertebroplasty technique. It is a minimally invasive procedure that aims to relieve pain, restore vertebral height, and correct kyphosis. During this procedure, an inflatable bone tamp is inserted into the collapsed vertebral body. Once inflated, the balloon elevates the end plates and thereby restores the height of the vertebral body. The balloon is deflated and removed, and the space is filled with bone cement. Creating a space in the vertebral body enables the application of more viscous cement and at a much lower pressure than is needed for vertebroplasty. This may result in less cement leakage and fewer complications. Balloons typically are inserted bilaterally, into each fractured vertebral body. Kyphoplasty usually is done under general anesthesia in about 1.5 hours. Patients typically are observed for only a few hours after the surgery, but some may require an overnight hospital stay.

Health Canada has licensed KyphX Xpander Inflatable Bone Tamp (Kyphon Inc., Sunnyvale, CA), for kyphoplasty in patients with VCFs. KyphX is the only commercially available device for percutaneous kyphoplasty. The KyphX kit uses a series of bone filler device tubes. Each bone filler device must be loaded manually with cement. The cement is injected into the cavity by pressing an inner stylet.

In the United States, the Food and Drug Administration cleared the KyphX Inflatable Bone Tamp for marketing in July 1998. CE (Conformité European) marketing was obtained in February 2000 for the reduction of fracture and/or creation of a void in cancellous bone.

Review Strategy

The aim of this literature review was to evaluate the safety and effectiveness of balloon kyphoplasty in the treatment of painful VCFs.

INAHTA, Cochrane CCTR (formerly Cochrane Controlled Trials Register), and DSR were searched for health technology assessment reports. In addition, MEDLINE, EMBASE, and MEDLINE In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations were searched from January 1, 2000 to September 21, 2004. The search was limited to English-language articles and human studies.

The positive end points selected for this assessment were as follows:

Reduction in pain scores

Reduction in vertebral height loss

Reduction in kyphotic (Cobb) angle

Improvement in quality of life scores

The search did not yield any health technology assessments on balloon kyphoplasty. The search yielded 152 citations, including those for review articles. No randomized controlled trials (RCTs) on balloon kyphoplasty were identified. All of the published studies were either prospective cohort studies or retrospective studies with no controls. Eleven studies (all case series) met the inclusion criteria. There was also a comparative study published in German that had been translated into English.

Summary of Findings

The results of the 1 comparative study (level 3a evidence) that was included in this review showed that, compared with conservative medical care, balloon kyphoplasty significantly improved patient outcomes.

Patients who had balloon kyphoplasty reported a significant reduction in pain that was maintained throughout follow-up (6 months), whereas pain scores did not change in the control group. Patients in the balloon kyphoplasty group did not need pain medication after 3 days. In the control group, about one-half of the patients needed more pain medication in the first 4 weeks after the procedure. After 6 weeks, 82% of the patients in the control group were still taking pain medication regularly.

Adjacent fractures were more frequent in the control group than in the balloon kyphoplasty group.

The case series reported on several important clinical outcomes.

Pain: Four studies on osteoporosis patients and 1 study on patients with multiple myeloma/primary cancers used the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) to measure pain before and after balloon kyphoplasty. All of these studies reported that patients had significantly less pain after the procedure. This was maintained during follow-up. Two other studies on patients with osteoporosis also used the VAS to measure pain and found a significant improvement in pain scores; however, they did not provide follow-up data.

Vertebral body height: All 5 studies that assessed vertebral body height in patients with osteoporosis reported a significant improvement in vertebral body height after balloon kyphoplasty. One study had 1-year follow-up data for 26 patients. Vertebral body height was significantly better at 6 months and 1 year for both the anterior and midline measurements.

Two studies reported that vertebral body height was restored significantly after balloon kyphoplasty for patients with multiple myeloma or metastatic disease. In another study, the researchers reported complete height restoration in 9% of patients, a mean 56% height restoration in 60% of patients, and no appreciable height restoration in 31% of the patients who received balloon kyphoplasty.

Kyphosis correction: Four studies that assessed Cobb angle before and after balloon kyphoplasty in patients with osteoporosis found a significant reduction in degree of kyphosis after the procedure. In these studies, the differences between preoperative and postoperative Cobb angles were 3.4°, 7°, 8.8°, and 9.9°.

Only 1 study investigated kyphosis correction in patients with multiple myeloma or metastatic disease. The authors reported a significant improvement (5.2°) in local kyphosis.

Quality of life: Four studies used the Short Form 36 (SF-36) Health Survey Questionnaire to measure the quality of life in patients with osteoporosis after they had balloon kyphoplasty. A significant improvement in most of the domains of the SF-36 (bodily pain, social functioning, vitality, physical functioning, mental health, and role functioning) was observed in 2 studies. One study found that general health declined, although not significantly, and another found that role emotional declined.

Both studies that used the Oswestry Disability Index found that patients had a better quality of life after balloon kyphoplasty. In one study, this improvement was statistically significant. In another study, researchers found that quality of life after kyphoplasty improved significantly, as measured with the Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire. Yet another study used a quality of life questionnaire and found that 62% of the patients that had balloon kyphoplasty had returned to normal activities, whereas 2 patients had reduced mobility.

To measure quality of life in patients with multiple myeloma or metastatic disease, one group of researchers used the SF-36 and found significantly better scores on bodily pain, physical functioning, vitality, and social functioning after kyphoplasty. However, the scores for general health, mental health, role physical, and role emotional had not improved. A study that used the Oswestry Disability Index reported that patients’ scores were better postoperatively and at 3 months follow-up.

These were the main findings on complications in patients with osteoporosis:

The bone cement leaked in 37 (6%) of 620 treated fractures.

There were no reports of neurological deficits.

There were no reports of pulmonary embolism due to cement leakage.

-

There were 6 cases of cardiovascular events in 362 patients:

3 (0.8%) patients had myocardial infarction.

3 (0.8%) patients had cardiac arrhythmias.

There was 1 (0.27%) case of pulmonary embolism due to deep venous thrombosis.

There were 20 (8.4%) cases of new fractures in 238 patients.

For patients with multiple myeloma or metastatic disease, these were the main findings:

The bone cement leaked in 12 (9.6%) of 125 procedures.

There were no reports of neurological deficits.

Economic Analysis

Balloon kyphoplasty requires anesthesia. Standard vertebroplasty requires sedation and an analgesic. Based on these considerations, the professional fees (Cdn) for each procedure is shown in Table 1.

Balloon kyphoplasty has a sizable device cost add-on of $3,578 (the device cost per case) that standard vertebroplasty does not have. Therefore, the up-front cost (i.e., physician’s fees and device costs) is $187 for standard vertebroplasty and $3,812 for balloon kyphoplasty. (All costs are in Canadian currency.)

There are also “downstream costs” of the procedures, based on the different adverse outcomes associated with each. This includes the risk of developing new fractures (21% for vertebroplasty vs. 8.4% for balloon kyphoplasty), neurological complications (3.9% for vertebroplasty vs. 0% for balloon kyphoplasty), pulmonary embolism (0.1% for vertebroplasty vs. 0% for balloon kyphoplasty), and cement leakage (26.5% for vertebroplasty vs. 6.0% for balloon kyphoplasty). Accounting for these risks, and the base costs to treat each of these complications, the expected downstream costs are estimated at less than $500 per case. Therefore, the expected total direct medical cost per patient is about $700 for standard vertebroplasty and $4,300 for balloon kyphoplasty.

Kyphon, the manufacturer of the inflatable bone tamps has stated that the predicted Canadian incidence of osteoporosis in 2005 is about 29,000. The predicted incidence of cancer-related vertebral fractures in 2005 is 6,731. Based on Ontario having about 38% of the Canadian population, the incidence in the province is likely to be about 11,000 for osteoporosis and 2,500 for cancer-related vertebral fractures. This means there could be as many as 13,500 procedures per year in Ontario; however, this is highly unlikely because most of the cancer-related fractures likely would be treated with medication. Given a $3,600 incremental direct medical cost associated with balloon kyphoplasty, the budget impact of adopting this technology could be as high as $48.6 million per year; however, based on data from the Provider Services Branch, about 120 standard vertebroplasties are done in Ontario annually. Given these current utilization patterns, the budget impact is likely to be in the range of $430,000 per year. This is because of the sizable device cost add-on of $3,578 (per case) for balloon kyphoplasty that standard vertebroplasty does not have.

Policy Considerations

Other treatments for osteoporotic VCFs are medical management and open surgery. In cases without neurological involvement, the medical treatment of osteoporotic VCFs comprises bed rest, orthotic management, and pain medication. However, these treatments are not free of side effects. Bed rest over time can result in more bone and muscle loss, and can speed the deterioration of the underlying condition. Medication can lead to altered mood or mental status. Surgery in these patients has been limited because of its inherent risks and invasiveness, and the poor quality of osteoporotic bones. However, it may be indicated in patients with neurological deficits.

Neither of these vertebral augmentation procedures eliminates the need for aggressive treatment of osteoporosis. Osteoporotic VCFs are often under-diagnosed and under-treated. A survey of physicians in Ontario (1) who treated elderly patients living in long-term care homes found that although these physicians were aware of the rates of osteoporosis in these patients, 45% did not routinely assess them for osteoporosis, and 26% did not routinely treat them for osteoporosis.

Management of the underlying condition that weakens the vertebral bodies should be part of the treatment plan. All patients with osteoporosis should be in a medical therapy program to treat the underlying condition, and the referring health care provider should monitor the clinical progress of the patient.

The main complication associated with vertebroplasty and balloon kyphoplasty is cement leakage (extravertebral or vascular). This may result in more patient morbidity, longer hospitalizations, the need for open surgery, and the use of pain medications, all of which have related costs. Extravertebral cement leakage can cause neurological complications, like spinal cord compression, nerve root compression, and radiculopathy. In some cases, surgery is required to remove the cement and release the nerve. The rate of cement leakage is much lower after balloon kyphoplasty than after vertebroplasty. Furthermore, the neurological complications seen with vertebroplasty have not seen in the studies of balloon kyphoplasty. Rarely, cement leakage into the venous system will cause a pulmonary embolism. Finally, compared with vertebroplasty, the rate of new fractures is lower after balloon kyphoplasty.

Diffusion – International, National, Provincial

In Canada, balloon kyphoplasty has not yet been funded in any of the provinces. The first balloon kyphoplasty performed in Canada was in July 2004 in Ontario.

In the United States, the technology is considered by some states as medically reasonable and necessary for the treatment of painful vertebral body compression fractures.

Conclusion

There is level 4 evidence that balloon kyphoplasty to treat pain associated with VCFs due to osteoporosis is as effective as vertebroplasty at relieving pain. Furthermore, the evidence suggests that it restores the height of the affected vertebra. It also results in lower fracture rates in other vertebrae compared with vertebroplasty, and in fewer neurological complications due to cement leakage compared with vertebroplasty. Balloon kyphoplasty is a reasonable alternative to vertebroplasty, although it must be reiterated that this conclusion is based on evidence from level 4 studies.

Balloon kyphoplasty should be restricted to facilities that have sufficient volumes to develop and maintain the expertise required to maximize good quality outcomes. Therefore, consideration should be given to limiting the number of facilities in the province that can do balloon kyphoplasty.

Objective

To review the evidence on the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of balloon kyphoplasty for the treatment of vertebral compression fractures (VCFs).

Background

Clinical Need: Target Population and Condition

VCFs are a common and often debilitating result of osteoporosis. They are caused when the vertebral body (the thick block of bone at the front of each vertebra) is too weak to support the loads of activities of daily living. Osteoporosis, a systemic disease characterized by a deficiency in bone mass, greatly increases the risk of these painful compression fractures. Bone mass is a major determinant of bone strength. Its decrease is the most important risk factor for osteoporotic fractures. (2) Painful osteoporotic fractures of the spine are a common cause of morbidity in the elderly. (3) They often are related to pulmonary dysfunction, (4;5) eating disorders, loss of independence, and mental status change due to pain and the use of medication. (6;7) A population-based study across 12 European centres by Silverman et al. (8) recently found that VCFs have a negative impact on health-related quality of life. They also found that the fractures that contributed most to impaired quality of life in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis were those at the vertebrae T11, T12, L1, L2, and L3.

The causes of osteoporosis may be primary or secondary. Primary osteoporosis includes age-related, or senile, osteoporosis, which affects women and men older than 70 years; and postmenopausal osteoporosis, which is associated with estrogen deficiency. (9) Secondary osteoporosis is caused by medications, endocrine disorders, chronic renal disease, hematopoietic (blood) disorders, immobilization, inflammatory arthropathy, poor nutrition, gastrointestinal disorders, and connective tissue disorders. (9) Researchers (10) have shown regular menstrual cycles in premenopausal women are essential to maintain bone density. Prolonged periods of amenorrhea can result in bone loss. Female athlete triad is a disorder defined as the combination of disordered eating, amenorrhea, and osteoporosis. It commonly affects young women active in sports. Disordered eating results in amenorrhea, bone loss, and a higher risk of fracture. Caloric deficits may predispose an athlete to premature osteoporosis, stress fractures, and reproductive disorders. (11)

Vertebral Compression Fractures

Primary osteoporosis is responsible for about 85% of VCFs. Secondary osteoporosis and neoplasms are responsible for the other 15%. (12) A VCF is operationally defined as a reduction in vertebral body height by at least 20% from the initial measurement of height. (13) It is classified as mild if the reduction in height is between 20% and 25%; moderate if the reduction is between 25% and 40%; and severe if it is 40% or more. (14) The most frequently fractured locations are the third-lower part of the thorax and the superior lumbar levels. (15) The cervical vertebrae and the upper third of the thorax are rarely involved. (16;17)

A typical bimodal pattern on the distribution of vertebral deformity has been reported. (18) This pattern shows a peak around T6–T8 and T11–L2 for females and males. Three osteoporotic fracture patterns have been described: wedge, crush, and biconcave. (13;19;20)

In a wedge fracture, the front border of the vertebra is collapsed, but the back border is almost intact. In a crush fracture, the entire vertebral body is collapsed. These 2 fracture patterns occur mostly in the mid-thoracic and thoracolumbar regions. In a biconcave fracture, the central part of the vertebral body is collapsed. This type of fracture happens more often in the lumbar region. Height loss happens with all of these, but it is more commonly associated with crush fractures. (13) The European vertebral osteoporosis study (20) found wedge compression fractures were the most common, followed by biconcave fractures.

Osteoporotic VCFs, in which the vertebral body wedges or collapses, cause kyphosis, a curved spine that causes the back to bow and leads to a hunched-back posture. Fractures in the thoracic spine increase thoracic spinal kyphosis. Fractures of the lumbar spine reduce lumbar lordosis, which results in a relative lumbar kyphosis. People with VCFs become shorter, due to the vertebral compression and from assuming a flexed or bowed posture to avoid pain. (13) Those with a history of such fractures have a higher risk of having another fracture. (21-23)

Thoracic kyphosis and a protuberant abdomen may affect the respiratory and gastrointestinal systems. Measures of forced vital capacity, and forced vital capacity in 1 second (the maximum amount of air in litres that can be forcibly and rapidly exhaled) may be lower in people with thoracic and lumbar fractures. (4;5) Leech et al. (4) showed that a single chronic thoracic fracture causes a 9% loss of forced vital capacity. (4) People may also experience early satiety and weight loss due to local kyphosis and secondary mechanical compression of the abdominal viscera. (24) Kyphosis also is associated with a loss of balance, a risk of repeated falls and new fractures, and progressive spinal deformity. (24)

Coping with chronic severe pain and disability due to spinal deformity adversely affects a person’s overall level of functioning and quality of life. Health is compromised in several ways. First, the associated lack of mobility can increase the rate of demineralization in the bones and thereby cause more fractures. Additionally, pain, depression, loss of lung capacity, loss of appetite, and medications and their adverse effects further aggravate the condition.

Furthermore, osteoporotic VCFs are associated with a higher rate of death. A large prospective cohort study (25) of 9,575 women who were followed-up for more than 8 years showed that those with radiographic evidence of VCFs had higher (23% to 34%) rates of mortality. Vertebral fractures were related to a higher risk of cancer and pulmonary death. Mortality rose with the number of VCFs. The age-adjusted mortality rate was 1.23 times higher for women with 1 VCF, and 2.3 times higher for women with 5 or more VCFs. Cooper et al. (26) reported a 5-year survival rate of 61% for people with VCFs, compared to that of 76% for their age-matched peers. Unlike in hip fractures, where the survival rate returns to the baseline rate within 6 months, survival after having a VCF steadily declines with time. (26)

Incidence and Prevalence of Vertebral Compression Fractures

Only about 30% of vertebral fractures are diagnosed in clinical practice, (27;28) yet they affect about 25% of women aged 50 years and older, and 40% of women aged 80 and older. (28) The Canadian multicentre osteoporosis study (18) reported on the prevalence of vertebral deformity in Canada in people over 50 years of age. To define the limit of normality, they plotted a normal distribution, including mean and standard deviations (SDs) derived from a reference population without any deformity. Using 3 SDs from the mean as the limit of normality, they found a prevalence rate of 23.5% in women and 21.5% in men. Using 4 SDs, the prevalence was 9.3% and 7.3%, for women and men, respectively. The prevalence of vertebral deformity rose with age. For people older than 80 years, the prevalence for women and men was 45% and 36%, respectively, using 3 SDs as the limit of normality.

A 10-year population-based study (29) of 598 people from the Swedish cohort in the European vertebral osteoporosis study reported on the prevalence of vertebral deformity. They studied 213 men with a mean age of 63 years and 257 women with a mean age of 64 years that were still alive after 10 years of follow-up. The prevalences of vertebral deformity at baseline using the limits of normality to define deformity (3 SDs, 4 SDs, and 5 SDs from the mean) were 20%, 8%, and 5% for men. For women, the corresponding numbers were 29%, 11%, and 8%. Lumbar vertebral deformity (3 SDs from the mean) was found in 5% of men and 3% of women. Thoracic vertebral deformity was present in 13% of men and 20% of women.

Ethnicity is an important factor to consider when assessing the risk of osteoporotic fractures. Data from the Health Care Financing Administration (30) on 152,000 discharges that listed a diagnosis of vertebral fracture over 4 years showed that white women had the highest rates (17.1 per 10,000 people per year), followed by white men (9.9 per 10,000). For black women and men, the corresponding rates were 3.7 and 2.5 per 10,000 people per year. Among white women, the rates were 5.3 discharges per 10,000 people at 65 years, to 47.8 discharges per 10,000 people at 90 years. White men, and black women and men experienced less dramatic age-related increases. Another study showed that the risk of vertebral fractures in Hispanic-American women was about one-half of that in white women. (31)

Cost of Osteoporotic Fractures

Osteoporosis is often clinically silent until it manifests as a fracture. Indeed, a painful VCF may be the first clinical sign of osteoporosis. In 1993 in Canada, 60,000 fractures in women and 16,000 fractures in men were due to osteoporosis. (32;32) The fractures that appeared more frequently in women were those of the vertebra, wrist, and hip. The direct cost of osteoporotic fractures in 1993 was estimated at $1.3 billion (Cdn), which included $437 million for hospitalization, $15.4 million for long-term care, and $279 million for chronic care. (2)

Existing Treatments Other Than Technology Being Reviewed

Open surgery of a vertebral fracture is indicated for only a few patients (less than 0.05% of VCFs) and only after the benefits and risks have been weighed. (33) Open surgery is risky: it is associated with morbidity and implant failure in this frail patient population. (34) Therefore, nonsurgical management, including medication, bed rest, and bracing is recommended for most patients. Although many patients respond well to these interventions, some develop chronic severe pain, discomfort, and a disability that adversely affects their quality of life.

Percutaneous vertebroplasty was developed in France by Deramond et al. (35) in 1987. It was first used to treat aggressive hemangiomas, and then to treat osteolytic metastases, multiple myeloma, and osteoporotic compression fractures. (36) Recently, this minimally invasive technique, during which bone cement is injected into a vertebral body, has been used to treat VCFs due to osteoporosis, multiple myeloma, and metastatic disease. (22;37) The aim is to alleviate pain by stabilizing the fracture.

Vertebroplasty relieves pain in most patients and it prevents further vertebral collapse. Clinical results have shown immediate and sustained pain relief in 70% to 95% of patients. (37) How vertebroplasty relieves pain exactly is unknown. Several hypotheses have been put forward to explain its analgesic effect, including stabilization of microfractures and decrease in mechanical stress, thermal and chemical effects of the cement, and a neurotoxic effect of the monomer in the compound. (38) Despite the high success in pain relief seen with vertebroplasty, it does not restore vertebral body height or correct spinal alignment. Furthermore, it is associated with a higher risk of cement leakage. Complications of cement leakage include spinal cord compression, nerve root compression, and pulmonary embolism on rare occasions. Additionally, vertebroplasty may alter the normal loading behaviour of the adjacent vertebrae, and there is an increased risk of adjacent segment VCF. (37)

New Technology Being Reviewed: Balloon Kyphoplasty

Balloon kyphoplasty is a modified vertebroplasty technique. It is a minimally invasive procedure used to treat VCFs due to primary osteoporosis, secondary osteoporosis, multiple myeloma, and osteolytic metastatic disease. It aims to correct deformity due to kyphosis and to relieve pain.

It is usually done under general anesthesia in about 1.5 hours. Patients usually are observed for only a few hours after the surgery, but some require an overnight hospital stay. During the procedure, a physician makes a small incision in the patient’s back to gain access to the fractured vertebral body. A cannula is used to create a channel through which an inflatable bone tamp can be inserted. The physician then places the bone tamp into the fractured vertebral body. The balloon at the tip of the bone tamp is inflated with a radiopaque contrast medium so that it can be monitored constantly by fluoroscopy. Once inflated, the balloon pushes the cortical bones apart and restores the vertebral body to its original height while creating a space that can be filled with bone cement. This cement supports the bone and helps prevent further collapse. The balloon is deflated and removed, and the remaining cavity is filled with bone cement.

It has been suggested that creating a gap in the vertebral body during kyphoplasty allows physicians to apply more viscous cement, and at a much lower rate of pressure, than is required for vertebroplasty. (15;39;40) This may lower the risk of the cement leaking through the vertebral body wall into the spinal canal and causing neurological complications. (15;39;40) Kyphoplasty is always done under fluoroscopy or computed tomography guidance. It is technically demanding, because the surgeon must translate 2-dimensional fluoroscopic images into 3 dimensions to ensure the balloon is placed precisely. Balloons typically are inserted bilaterally into each fractured vertebral body. If the bone being treated is partially healed or has an uninjured area, it will resist the balloon’s expansion. The digital pressure gauge allows the physician to precisely monitor balloon expansion.

Regulatory Status

Health Canada has licensed the KyphX Xpander Inflatable Bone Tamp (manufactured by Kyphon Inc., Sunnyvale, CA) for balloon kyphoplasty to treat patients with VCFs. This is the only commercially available device for percutaneous kyphoplasty. The KyphX kit uses a series of bone filler device tubes. Each bone filler device must be loaded manually with cement. The cement is injected into the cavity by pressing an inner stylet.

In the United States, the Food and Drug Administration cleared the KyphX Inflatable Bone Tamp for marketing in July 1998. CE (Conformité European) marketing was obtained in February 2000 for the reduction of fracture and/or creation of a void in cancellous bone. Health Canada information for the inflatable bone tamp device and its related instruments is shown in Table 1.

Table 1: Professional Fees for Standard Vertebroplasty and Balloon Kyphoplasty.

| Standard Vertebroplasty | Balloon Kyphoplasty | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| $148.10: | Physician reimbursement for percutaneous vertebroplasty – first level per patient per day | $148.10: | Physician reimbursement for percutaneous vertebroplasty – first level per patient per day | ||

| 4 | anesthesia units | ||||

| x | |||||

| $11.77 | unit fee for anesthetists | ||||

| = $47.08: | anesthetist reimbursement alongside FSC = J016 | ||||

| $74.05: | Physician reimbursement for each additional vertebral level (maximum of 3 per patient per day) | $74.05: | Physician reimbursement for each additional vertebral level (maximum of 3 per patient per day) | ||

| 52.9%: | % of percutaneous vertebroplasties that also have J054 | 52.9%: | % of percutaneous vertebroplasties that also have J054 | ||

| $187.24: | Total professional medical fees per case | $234.32: | Total professional medical fees per case | ||

Table 1: Health Canada Licensing: The Inflatable Bone Tamp for Balloon Kyphoplasty.

| Licence Number |

Licence Name | Class | Device Name |

|---|---|---|---|

| 24649 | KYPHON INTRODUCER SETS | 2 | KYPHX ADVANCED OSTEO INTRODUCER SYSTEM |

| 24649 | KYPHON INTRODUCER SETS | 2 | KYPHX INTRODUCER TOOL KIT |

| 24649 | KYPHON INTRODUCER SETS | 2 | KYPHX OSTEO INTRODUCER SYSTEM |

| 24739 | KYPHX BONE FILLER DEVICE | 2 | KYPHX BONE FILLER DEVICE |

| 24741 | KYPHX INFLATABLE BONE TAMPS | 2 | KYPHX INFLATABLE BONE TAMPS |

| 61350 | KYPHX XPANDER INFLATION SYRINGE | 2 | KYPHX XPANDER INFLATION SYRINGE |

| 61556 | 11 GAUGE BONE BIOPSY NEEDLE | 2 | 11 GAUGE BONE ACCESS NEEDLE |

| 63337 | KYPHON MIXER | 2 | KYPHON MIXER |

| 65780 | KYPHX BONE BIOPSY DEVICES | 2 | BONE BIOPSY - STRAIGHT |

| 65780 | KYPHX BONE BIOPSY DEVICES | 2 | BONE BIOPSY - TAPERED |

| 65781 | KYPHX INFLATABLE BONE TAMPS (EXACT & ELEVATE) |

2 | KYPHX INFLATABLE BONE TAMPS |

| 66380 | KYPHX LATITUDE CURETTE - DISPOSABLE | 2 | KYPHX LATITUDE CURETTE, T-TIP - DISPOSABLE |

Literature Review on Effectiveness

Objective

The aim of this review was to evaluate the safety and effectiveness of balloon kyphoplasty to treat VCFs.

Questions Asked

Is balloon kyphoplasty as or more effective than vertebroplasty at treating painful VCFs?

Is balloon kyphoplasty as or more effective than vertebroplasty at restoring vertebral body height and correcting kyphosis?

Is balloon kyphoplasty as or more effective than vertebroplasty at improving the quality of life in patients with VCFs?

Are there any risks associated with balloon kyphoplasty?

Methods

The inclusion criteria were as follows:

Studies comparing the clinical outcomes of kyphoplasty with vertebroplasty or conservative treatment

Studies reporting on the safety and efficacy of balloon kyphoplasty

The exclusion criteria were as follows:

Studies focusing on the other aspects of the procedure

Studies investigating diseases and conditions other than osteoporosis and multiple myeloma or cancer

Studies with fewer than 15 patients

The Medical Advisory Secretariat searched INAHTA, Cochrane CCTR (formerly Cochrane Controlled Trials Register), and DSR for health technology assessments. MEDLINE, EMBASE, and MEDLINE In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations were searched from January 1, 2000, to September 21, 2004. The search was limited to English-language articles and human studies.

The positive clinical outcomes of interest selected for this assessment were as follows:

Reduction in pain scores

Reduction in vertebral height loss

Reduction in kyphotic angle

Improvement in quality of life scores

The negative end points selected for this assessment were as follows:

Incidence of cement leakage

Incidence of neurological deficits

Incidence of cardiovascular events

Incidence of pulmonary complications

Results of Literature Search

No health technology assessments on balloon kyphoplasty were found. The search yielded 152 citations, including those for review articles. Nor were any randomized controlled trials (RCTs) on balloon kyphoplasty found. All of the published studies were either prospective cohort studies or retrospective studies without control groups. Eleven studies (all case series) met the inclusion criteria. There was also a comparative study published in German that had been translated into English. The results of this study are discussed separately from the other studies further in this review. Levels of evidence were assigned according to the scale based on the hierarchy by Goodman (1985). An additional designation “g” was added for preliminary reports of studies that were presented at international scientific meetings (Table 2).

Table 2: Quality of Evidence for Studies on Balloon Kyphoplasty.

| Study Design | Level of Evidence |

No. Eligible Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Large RCT,* systematic reviews of RCTs | 1 | 0 |

| Large RCT, unpublished but reported to an international scientific meeting | 1(g)† | 0 |

| Small RCT | 2 | 0 |

| Small RCT, unpublished but reported at an international scientific meeting | 2(g) | 0 |

| Non-RCT with contemporaneous controls | 3a | 1 |

| Non-RCT with historical controls | 3b | 0 |

| Non-RCT presented at international conference | 3(g) | 0 |

| Surveillance (database or register) | 4a | 0 |

| Case series (multisite) | 4b | 0 |

| Case series (single site) | 4c | 11 |

| Retrospective review, modeling | 4d | 0 |

| Case series presented at international conference | 4(g) | 0 |

RCT refers to randomized controlled trial.

g refers to grey literature.

The results of the studies on mainly patients with osteoporosis are discussed separately from those on patients with multiple myeloma or metastatic disease. As noted, all of the studies were case series. These typically included patients with fractures due to osteoporosis, malignant conditions, or both.

Most of the studies used the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) to measure pain. The VAS rates pain on a scale of 0 to 10: 0 indicates no pain and 10 indicates the worst pain.

The researchers also used the Short Form 36 (SF-36) Health Survey Questionnaire, the Oswestry Disability Index (ODI), also known as Oswestry Low Back Pain Disability Questionnaire, and the Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire (scaled from 0 to 24 with 0 representing normal function) to measure various aspects of quality of life.

To estimate the prefracture height of the treated vertebra, the height of an adjacent vertebra with the most normal morphology was measured. The height measured along the anterior and posterior wall of the vertebral body was defined as the anterior and posterior height, and a perpendicular planar in the midpoint of the anterior and posterior wall was defined as the mid-vertebral height.

Height restoration was calculated as height regained: post-treatment height minus pretreatment height.

Kyphosis was determined by measuring a Cobb angle between the inferior endplate of the superior vertebral body and the superior endplate of the inferior vertebral body adjacent to the fractured vertebra.

The literature search did not find any studies comparing balloon kyphoplasty with vertebroplasty. Therefore, the Medical Advisory Secretariat analyzed the studies on vertebroplasty separately. These findings are reported after those on kyphoplasty.

Case Series

There were 8 case series on balloon kyphoplasty in patients with osteoporosis: 6 prospective cohort studies and 2 retrospective studies. However, 4 of these (15;41-43) also included some patients who had multiple myeloma or metastatic disease. A summary of the patient characteristics and procedures for all 8 of the case series is shown in Tables 3A and 3B.

Table 3A: Studies on Balloon Kyphoplasty in Patients With Osteoporosis.

| Study, year | Crandall et al., 2004 (44) | Rhyne et al., 2004 (45) | Masala et al., 2004 (15) |

Ledlie et al., 2003 (41) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study design | Prospective | Retrospective | Prospective | Retrospective |

| Patients, n | 47 Acute fracture: 23 Chronic fracture: 24 |

52 | 16 | 96 |

| Fractures, n | 86 (40 acute, 46 chronic) | 82 | Not stated | 133 |

| Primary diagnosis, n | • Primary osteoporosis: 32 • Steroid-induced: 11 Other: 4 |

All osteoporosis | Osteoporosis: 12 Cancer: 4 (25%) • Multiple myeloma: 3 • Lung metastasis: 1 |

Osteoporosis: 90 (94%) • Primary: 89 • Steroid-induced: 1 Metastatic cancer: 6 (6%) |

| Sex, n | Female: 35 Male: 12 |

Female: 41 Male: 11 |

Female: 9 Male: 7 |

Female: 67 Male: 29 |

| Mean age, years (range) | 74 (47–91) | 74 (49–89) | 72.3 (63–82) | 76 (51–93) |

| Number of procedures | 55 | Not stated | Not stated | 104 |

| Mean duration of symptoms | Acute: 1.1 months (6–67 days) Chronic: 11 months (4 –31 months) |

31.3 weeks (1–120 weeks) |

Not stated | 2.4 months (2 days–14 months) |

| Location of fractures | T4L5 | Thoracic level: 34 Lumbar level 48 |

T8–L4 | T5–L5 |

| Mean follow-up, months (range) | 18 (6–24) | 9 (1–23) | No follow-up | 1 (n = 85) 3 (n = 73) 6 (n = 52) 12 (n = 29) |

| Instruments for measuring clinical outcomes | • VAS* for pain • Cobb angle • ODI |

• VAS for pain • Cobb angle • Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire |

• VAS for pain • Cobb angle |

• VAS for pain • Ambulatory status (questionnaire) |

ODI indicates Oswestry Disability Index; VAS, Visual Analogue Scale.

Table 3B: Studies on Balloon Kyphoplasty in Patients with Osteoporosis.

| Study, year | Coumans et al., 2003 (42) | Phillips et al., 2003 (39) | Theodorou et al., 2002 (46) |

Lieberman et al., 2001 (43) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study design | Prospective cohort | Prospective cohort | Prospective cohort | Prospective cohort |

| Patients, n | 78 | 28 | 15 | 30 |

| Reason for surgery | Painful VCF unresponsive to medical treatment |

Painful VCF refractory to medical treatment |

Painful VCF unresponsive to medical treatment |

|

| Fractures, n | Not stated | 61 Single: 9 patients Multiple: 20 patients |

24 Thoracic: 14 Lumbar: 10 |

Not stated |

| Primary diagnosis, n | Osteoporosis: 63 (80%) Multiple myeloma: 15 (20%) |

Osteoporosis | Osteoporosis: 15 | Osteoporosis: 24 (80%) Multiple myeloma: 6 (20%) |

| Sex, n | Female: 45 Male: 33 |

Not stated | Female: 11 Male: 4 |

Not stated |

| Mean age, years (range) | 71 (44–89) | 70 | 75 (41–86) | 68.6 (48–86) |

| Procedures, n | 188 | 37 | 24 | 70 |

| Mean duration of symptoms, months (range) | 7 | 3.8 (1–12) | 3.5 (0.5–12) | 5.9 (0.5–24) |

| Location of fractures | T5L5 | T6L5 | Not stated | T6L5 |

| Duration of follow-up, months | 18 | 12 (19 patients) | 6–8 | 7 (mean) |

| Instruments for measuring clinical outcomes | • VAS* • ODI • SF-36 |

• VAS • Cobb angle |

No instrument for pain measurement • Vertebral body height • Cobb angle |

• Vertebral body height measurement • SF-36 |

ODI indicates Oswestry Disability Index; VAS, Visual Analogue Scale.

Pain Relief

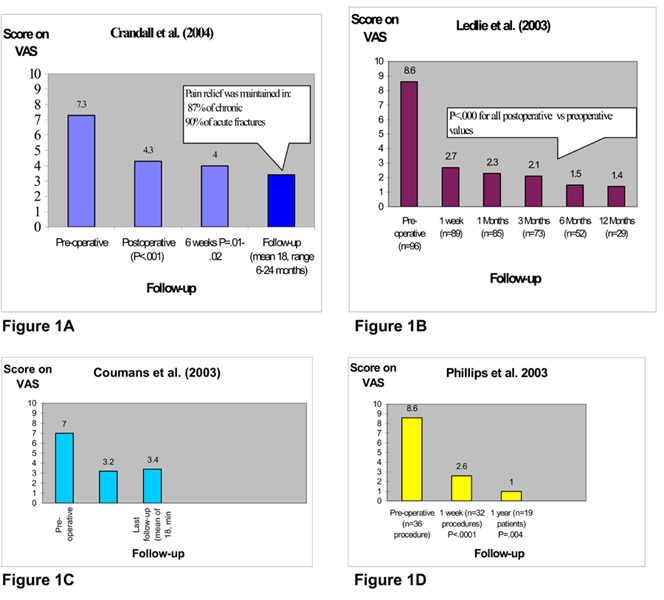

Most of the studies that measured pain with the VAS found that patients reported significant improvement in pain scores after balloon kyphoplasty. (39;41;42;44;45) (See Figures 1A to 1D for summary data on pain control.) Two studies (15;46) reported that patients’ pain scores had improved, but they did not report the P values. Lieberman et al. (43) found a significant improvement in patients’ bodily pain after balloon kyphoplasty as measured by the SF-36 questionnaire.

Figures 1A to 1D: Reported Visual Analogue Scores for Pain in Balloon Kyphoplasty Studies: Preoperative, Postoperative, and Follow-up Data (39;41;42;44).

VAS indicates Visual Analogue Scale.

Four studies had follow-up data on pain. (39;39;41;42;44) In Crandall’s study (44), 90% of acute and 87% of chronic fractures were associated with pain relief which was maintained throughout follow-up. Ledlie et al. (41) followed-up patients for up to 1 year (n = 29, 30%). In that study, (41) all of the postoperative measures were significantly improved compared with the preoperative scores. In a study by Coumans et al., (42) follow-up data on pain were available for 62% of the patients for at least 12 months (mean, 18 months). Results showed pain scores were significantly better at the last follow-up assessment. Similarly, Phillips et al. (39) reported a significant improvement in pain scores for 19 of the 28 patients (68%) that were followed-up for 1 year. Theodorou et al. (46) did not report pain scores, but noted that all of the patients experienced dramatic pain relief within hours of having the procedure and were satisfied with the treatment. They followed-up patients for 6 to 8 months (except for 1 patient, who died due to a different underlying disease), and found that all of the patients continued to be free from pain.

Figures 1A to 1D show the improvements in pain scores using VAS in the studies with follow-up data.

Rhyne et al. (45) and Masala et a. (15) reported an improvement in patients’ pain scores, but they did not provide any follow-up data (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Reported Visual Analogue Scores for Pain in Two Balloon Kyphoplasty Studies (Before and After Surgery) (15;45).

VAS refers to Visual Analogue Scale.

Height Gain

All 5 of the studies (41;43-46) that examined vertebral height gain in patients with osteoporosis after they had balloon kyphoplasty found significant gains. All 4 of the studies (39;44-46) that looked at kyphosis correction found significant improvements in kyphosis and a reduction in Cobb angle (Tables 4A and 4B).

Table 4A: Height Gain in Studies on Balloon Kyphoplasty in Patients With Osteoporosis.

| Study, year | Crandall et al., 2004 (44) |

Rhyne et al., 2004 (45) | Masala et al., 2004 (15) | Ledlie et al. 2003 (41) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vertebral height as percentage of the estimated pre-fracture height (mean) | Acute VCFs* -Preoperative: 58% -Postoperative: 86% (P< .001) Chronic VCFs -Preoperative: 56% -Postoperative: 79% (P< .001) Acute fractures were restored more effectively, resulting in a significantly greater mean vertebral height than treated chronic fractures (P = .01) |

Anterior vertebral height -Preoperative: 19.6 mm -Postoperative: 24.2 mm (P < .05) Midline vertebral height -Preoperative: 16.8 mm -Postoperative: 20.7 mm (P < .05) Posterior vertebral height -Preoperative: 25.8 mm -Postoperative: 26.1 mm (Not significant) |

Not stated | Anterior vertebral height -Preoperative: 66% -1 month: 89% (P < .0001) -6 months: 86% -1 year (n=26): 85% Midline -Preoperative: 65 -1 month: 90 (P < .0001) -6 months: 87% -1 year (n=26): 89% 1 month vs. 6 months and 1 month vs. 1 year were not different |

| Kyphosis correction | Cobb angle Acute VCFs -Preoperative: 15° -Postoperative: 8° (P < .001) Chronic VCFs -Preoperative: 15° -Postoperative: 10° (P < .001) |

Cobb angle -Preoperative: 22.5° -Postoperative: 19.1° (P < .05) |

Cobb angle -Reduced (no details) |

Not stated |

VCF indicates vetebral compression fracture.

Table 4B: Height Gain in Studies on Balloon Kyphoplasty in Patients With Osteoporosis.

| Study, year | Coumans et al., 2003 (42) | Phillips et al., 2003 (39) | Theodorou et al., 2002 (46) | Lieberman et al., 2001 (43) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vertebral height restoration compared with estimated normal height, mean | Not stated | Not stated | Preoperative: 78.6% (SD, 15.6%) Postoperative: 91.5% (SD, 11%) (P = .000) |

The absolute mean height gain was 2.9 mm (P = .001). |

| Kyphosis correction or Cobb angle | Not stated | Cobb angle: Mean (range) -Preoperative: 17.5° (2°–57°) -Postoperative: 8.7° (1°–42°) Improvement: 8.8° (0°–29°)P < .0001 |

Kyphosis: -Preoperative: 25.5° (SD, 10°) -Postoperative: 15.6° (SD, 6.7°) (P = .000) |

Not stated |

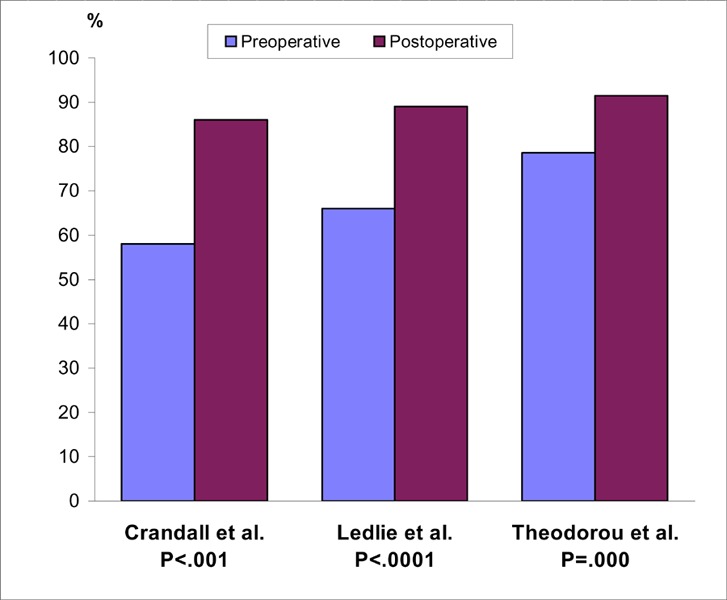

Three studies reported proportions of height restoration (Figure 3) Rhyne et al. (45) reported the difference between preoperative and postoperative vertebral height in millimetre, and Lieberman et al. (43) reported the absolute mean height gain. Crandall et al. (44) also measured interobserver variability by taking duplicate repeat measurements of all vertebrae. It was ±1 mm for measuring height and ±2° for measuring kyphosis. In Figure 3, the Y-axis shows the percentage of the estimated prefracture height of the vertebral body treated.

Figure 3: Restoration of Vertebral Body Height in Patients With Osteoporosis Across Balloon Kyphoplasty Studies (41;44;46).

Quality of Life

The findings on quality of life are summarized in Tables 5A and 5B. (39;42-45)

Table 5A: Quality of Life After Balloon Kyphoplasty in Patients with Osteoporosis.

| Study, year | Crandall et al., 2004 (44) |

Rhyne et al., 2004 (45) |

Masala et al., 2004 (15) |

Ledlie et al., 2003 (41) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quality of life/disability | Oswestry Disability Index: -60% of the patients had at least a 25% improvement in their scores |

Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire: -Preoperative: 19.3 -Postoperative: 8.1 (P < .05) |

Not stated | Not stated |

Table 5B: Quality of Life After Balloon Kyphoplasty in Patients with Osteoporosis.

| Study, year | Coumans et al., 2003 (42) | Phillips et al., 2003 (39) | Theodorou et al., 2002 (46) | Lieberman et al., 2001 (43) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quality of life/disability | SF–36 mean scores Improved (P < .005) -Bodily pain -Mental health -Social functioning Role functioning Improved (P < .05) -Physical functioning -Role emotional -Vitality Declined: -General health (not significant) Oswestry Disability Index: -Preoperative: 47 -Postoperative: 34 (P < .001) Last follow-up: 35 (P < .001) |

Quality of life questionnaire -Improved comfort: 29 of 30 respondents -Returned to normal activity: 18 of 29 patients 2 patients experienced pain relief but claimed reduced mobility after surgery |

Not stated | SF–36 mean scores Improved: -Bodily pain: from 11.6 to 58.7 (P = .0001) -Social functioning: from 28.6 to 69 (P = .0004) -Vitality: from 24.8 to 47.9 (P = .001) -Physical function: from 11.7 to 47.4 (P = .002) -Mental health: from 59.2 to 71.1 (P = .015) -Role physical: from 1.2 to 29.8 No significant improvement: -General health: Declined: Role emotional |

Acute Versus Chronic Fractures

Only 1 group of researchers looked at the clinical and radiographic outcomes of balloon kyphoplasty for acute and chronic fractures. (44) Patients with either type of fracture had a significant reduction in pain, which most of them maintained during follow-up (mean follow-up, 18 months). Vertebral height and kyphosis also improved significantly in both groups. However, the height in acute fractures was restored more effectively, which resulted in a significantly higher mean vertebral body height (P = .01). Height correction was not achieved in 20% of chronic fractures and 8% of acute fractures. Fractures treated within 10 weeks were more than 5 times as likely to be reducible (i.e., able to be restored to more than 80% of the estimated normal vertebral body height).

Quality of life improved for both groups of patients. The researchers also measured medication use before and after balloon kyphoplasty. When the data were converted to an ordinal scale, the mean medication score fell from 5.4 (SD, 2.5) preoperatively to 3.6 (SD, 2.3) at the last follow-up assessment. The authors concluded that chronic fractures could also be treated with balloon kyphoplasty.

Phillips et al. (39) found a weak but statistically significant association between the age of the fracture and the degree of deformity correction with balloon kyphoplasty. In 26 patients who had fractures that were less than 90 days old, the correlation coefficient was 0.27 (P = .0085). In fractures older than 90 days, the age of the fracture and the degree of deformity correction were not correlated.

Complications of Balloon Kyphoplasty

Tables 6A and 6B show the complications in patients with osteoporosis after balloon kyphoplasty.

Table 6A: Complications After Balloon Kyphoplasty in Patients With Osteoporosis.

| Study, year | Crandall et al., 2004 (44) | Rhyne et al., 2004 (45) | Masala et al., 2004 (15) | Ledlie et al., 2003 (41) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complications | -Cement leaks: 0 -Neurologic: 0 -Infection: 0 -Cardiovascular: 1 (cardiac arrhythmia) -Pulmonary: 0 -Balloon rupture: 2 |

-Cement leaks: 8 of 82 levels (9.8%) -Neurologic: 0 -Infection: 0 -Pulmonary: 0 -Cerebrovascular: 0 |

-Cement leaks: 0 -Neurologic: 0 -Infection: 0 -Pulmonary: 0 |

-Cement leaks: 12 of 133 levels (9%) -Neurologic: 0 -Infection: 0 -Pulmonary embolism: 1 case 2 weeks postoperatively. No evidence of PMMA was detected in this patient’s lung on a CT scan. This patient had a history of deep venous thrombosis. -Cerebrovascular: 0 |

| New fractures | 1 patient at 6 weeks follow-up | 7 patients | No follow-up was available | 4 patients |

Table 6B: Complications After Balloon Kyphoplasty in Patients With Osteoporosis.

| Study, year | Coumans et al., 2003 (42) | Phillips et al., 2003 (39) | Theodorou et al., 2002 (46) | Lieberman et al., 2001 (43) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complications | -Cement extravasation: 5 of 188 levels (2.6%) (asymptomatic) -Neurological: 0 -Infection: 0 -Cardiovascular: 1 cardiac arrhythmia + 1 myocardial infarction due to fluid overload -Other: 0 |

-Cement extravasation: 6 of 61 levels (9.8%), asymptomatic -Cardiovascular: 1 myocardial infarction (discharged 2 days later) + 1atrial fibrillation and exacerbation of congestive heart failure -Other: 1 urinary retention (lasted for 24 hours) |

No significant complications related to the procedure were encountered. | -Cement extravasation: 6 of 70 levels (8.6%), with no clinical consequences -Neurological: 0 -Cardiovascular: 1 myocardial infarction due to fluid overload -Other: 2 patients had rib fractures related to positioning |

| New fractures | Not stated | 3 patients had fractures in adjacent vertebrae, and 2 had them in non-adjacent vertebrae | 3 patients | Not stated |

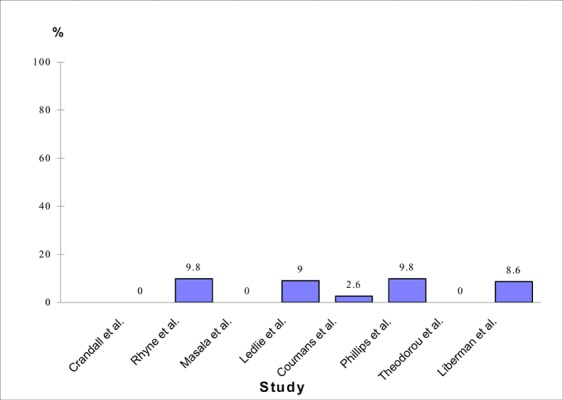

The most commonly reported complication was cement leakage. There were 37 (6%) reports of cement leakage in 620 treated fractures in patients with osteoporosis (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Rates of Cement Leakage After Balloon Kyphoplasty (15;39;41-46).

No neurological deficits were reported in any of the balloon kyphoplasty studies.

No cases of pulmonary embolism due to cement leakage were reported. Ledlie et al. (41) reported 1 case of pulmonary embolism due to deep venous thrombosis.

There were 6 (1.6%) cardiovascular events reported for 362 patients with osteoporosis. The perioperative complications were myocardial infarction (n = 3 [0.8%]); cardiac arrhythmia (n = 3 [0.8%]); and pulmonary embolism due to deep venous thrombosis (n = 1 [0.27%]).

Five studies on 238 patients with osteoporosis found 20 (8.4%) cases of new vertebral body fractures. Based on the results of this review, it is unclear if either vertebroplasty or balloon kyphoplasty is associated with a higher risk of osteoporotic fractures in the adjacent vertebrae. It has been shown that the presence of 1 or more vertebral fractures at the time baseline measurements are taken increases the risk of a new vertebral fracture by fivefold during the first year. (21) Based on level c evidence, (33) the incidence of new fractures is less than that observed with conventional medical care. Therefore, balloon kyphoplasty does not seem to increase the incidence of new fractures.

Clinical Outcomes in Patients with Multiple Myeloma

Two prospective cohort studies (47;48) and 1 retrospective study (49) investigated the clinical outcomes of balloon kyphoplasty in patients with multiple myeloma and other primary cancers. Table 7 shows the study and patient characteristics, and Table 8 shows the clinical outcomes.

Table 7: Summary of Studies on Balloon Kyphoplasty in Patients with Multiple Myeloma and Other Primary Cancers.

| Study, year | Lane et al., 2004 (47) | Dudeney et al., 2002 (48) |

Fourney et al., 2003 (49) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Study design | Prospective cohort | Prospective cohort | Retrospective |

| Patients, n | 19 | 18 | 15 |

| Reasons for surgery | Not stated | Patients had pain unresponsive to operative modalities | |

| Fractures, n | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated |

| Primary diagnosis | Multiple myeloma | Multiple myeloma | 6 myeloma 9 other primary malignancies |

| Sex | Female: 7 Male: 12 |

Not stated | Female: 7 Male: 8 |

| Mean age, years (range) | 60.4 (45–74) | 63.5 (48–79) | 62 (SD, 13) |

| Procedures, n | 46 | 55 | 32 |

| Mean duration of symptoms in months | > 3 (90% of patients) | 11 (range, 0.5–24 months) | 3.2 (range, 1week to 26 months) |

| Location of fractures | -Thoracic: 18 -Thoracolumbar: 14 -Lumbar: 14 |

T6–L5 | T6–L5 |

| Mean duration of follow-up, months | 3 | 7.4 | Median, 4.5 months (range, 1 day to 19.7 months) |

| Measures of clinical outcomes | -Oswestry Disability Index -Radiography |

-Height measurement -SF–36 |

-Visual Analogue Scale -Height measurement -Kyphosis |

Table 8: Clinical Outcomes After Balloon Kyphoplasty in Patients With Multiple Myeloma and Other Primary Cancers.

| Study, year | Lane et al., 2004 (47) | Dudeney et al., 2002 (48) | Fourney et al., 2003 (49) |

|---|---|---|---|

| VAS | Not stated | Not stated | -Preoperative: 8 -Postoperative: 2 -3 months: 2.5 -1 year: 2 All results were significant (P < .05) Note: Analgesic consumption: Reduced at 1 month, (P = .03) |

| Functional status | Oswestry Disability Index score Preoperative: 48.9 (SD, 16.6) 3 months after procedure: 32.6 (SD, 13.6) (P < .001) Patients with preoperative scores less than 28 had no significant improvement |

SF-36 improvement: -Bodily pain: from 23.2 to 55.4 (P = .008) -Physical functioning: from 21.3 to 50.6 (P = .001) -Vitality: from 31.3 to 47.5 (P = .012) -Social functioning: from 40.6 to 64.8 (P = .014) General health, mental health, role physical, and role emotional scores did not show significant improvement |

N/A |

| Vertebral height restoration | Anterior: mean, 37.8% (SD, 26.9%; P < .01) (35 of 46 levels) Mid-vertebral: mean, 53.4% (SD, 29.1%; P < .001) (42 of 46 levels) |

Height restoration measurement was possible in only 39 of the 55 levels treated. In 12 (31%) levels, there was no appreciable height restoration. In 4 (9%) levels, complete restoration occurred. In remaining 23 (60%) levels, there was a mean height restoration of 56%. |

The mean vertebral height lost before kyphoplasty was 9.7mm (SD, 5.1 mm). The mean height regained by the procedure was 4.5 mm (SD, 3.6 mm; P < .01). The mean f restored body height was 42% (SD, 21%) Mean local kyphosis: -Preoperative: 25.7 (SD, 9.7) -Postoperative: 20.5 (SD< 8.7) (P = .001) |

| Complications | Cement extravasation: 10 (26.3%) of the 38 levels that films were available Neurological: 0 |

Cement extravasation: 2 (4%) of 55 procedures Neurological: 0 |

Cement leakage: 0 Neurological: 0 |

| Incidence of new fractures | Not stated | Not stated | 0 |

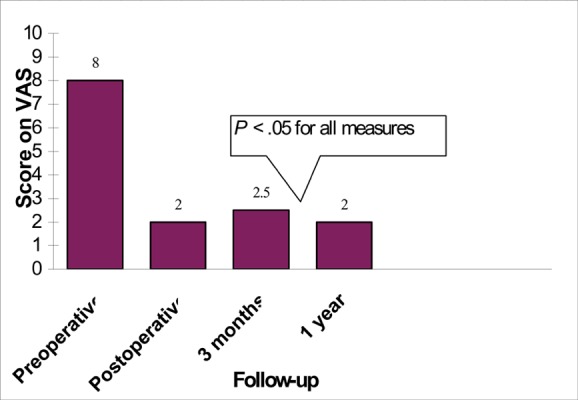

Two prospective studies (47;48) on patients with multiple myeloma found that balloon kyphoplasty was effective at relieving pain and restoring height. Lane et al. (47) used the ODI and found a significant improvement in patients’ reported pain scores at 3 months after balloon kyphoplasty. Also in this study, anterior and mid-vertebral body height increased significantly after the procedure. Dudeney et al. (48) used the SF–36 questionnaire and found that patients reported significant improvement in bodily pain scores. Some patients reported improved vertebral body height. Fourney et al. (49) reported improved VAS scores and also provided 1-year follow-up data (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Reported Visual Analogue Scores for Pain in Patients With Multiple Myeloma and Primary Cancers: Preoperative, Postoperative, and Follow-up Data (49).

The rate of cement leakage ranged from 0% to 26% in these 2 studies. There was no association between cement leakage during the procedure and neurological deficits.

Non-Randomized Prospective Clinical Trial

One prospective German-language study (33) was identified through the documentation provided for services of the health insurance in one European country. It was translated into English. Komp et al. (33) compared patients treated with balloon kyphoplasty (n = 21) with patients treated conservatively (n = 19). All of the patients had osteoporosis and a radiologically verified vertebral fracture and no neurological deficits. The mean duration of symptoms was 34 days (reported for all patients only). The mean age of patients who had kyphoplasty was 74.3 years. For those treated conservatively, it was 72.4 years. The measures used were the Visual Analogue Scale for back pain, the German versions of the North American Spine Society’s pain and neurology scales, and the ODI.

In the kyphoplasty group, 1 patient died due to causes unrelated to the therapy, and 1 patient relocated. In the conservatively treated group, 2 patients had to be hospitalized for several weeks due to stroke and pneumonia. Therefore, 36 patients were available for follow-up: 19 in the kyphoplasty group and 17 in the conservatively treated group. There were no major differences between the groups on sex, age, height, weight, and other illnesses. All patients in the kyphoplasty group were mobile on the day of the operation.

Patients who had balloon kyphoplasty reported significantly less pain postoperatively, and no patient needed pain medication after 3 days. Five patients in the control group had more vertebral fractures; after 6 months, this rose to 11 patients, who had up to 3 more fractures. None of the patients who had kyphoplasty had fractures in the adjacent vertebral bodies. Patients in this group did significantly better across all measures compared with those in the control group (Tables 9 and 10).

Table 9: Outcomes for Patients Receiving Balloon Kyphoplasty in Komp et al. (33).

| Scale | Preoperative Score |

Score at 1 week |

Score at 6 weeks |

Score at 6 months |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VAS,* mean (range) | 91(80–100) | 25 (5–-55) | 20 (0–35) | 25 (0–30) |

| NASS* pain, mean (range) | 5.4 (5–-6) | - | 1.9 (1.2-2.5) | 2 (1.4–2.4) |

| NASS neurology, mean (range) | 1.1 (1–1.2) | - | 1.1 (1–1.2) | 1.1 (1–1.3) |

| ODI,* mean (range) | 84 (70–100) | - | 22(10–44) | 24 (12–40) |

NASS indicates North American Spine Society; ODI, Oswestry Disability Index; VAS, Visual Analogue Scale.

Table 10: Outcomes for Patients Receiving Conservative Treatment in Komp et al. (33).

| Scale | Preoperative Score |

Score at 1 week |

Score at 6 weeks |

Score at 6 months |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VAS,* mean (range) | 91(75–100) | 86 (55-95) | 88 (65–100) | 83 (55–100) |

| NASS* pain, mean (range) | 5.2 (4.7–6) | - | 4.9 (4.5–5.9) | 4.8 (4.2–5.8) |

| NASS neurology, mean (range) | 1 (1–1) | - | 1.1 (1–1.3) | 1.1 (1–1.3) |

| ODI,* mean (range) | 82 (68–100) | - | 78(68–96) | 76 (72–92) |

NASS indicates North American Spine Society; ODI, Oswestry Disability Index; VAS, Visual Analogue Scale.

To date, no RCTs have been published that compare kyphoplasty with vertebroplasty. However, there have been retrospective and prospective studies on each of the procedures. Researchers generally agree that both procedures provide considerable pain relief for most patients. In one literature review, Mehbod et al. (37) found that vertebroplasty relieved pain in 70% to 95% of patients with osteoporotic VCFs.

To compare the risk of cement leakage, neurological deficits, and pulmonary embolism for the 2 procedures, the findings from this review were compared with the results of selected vertebroplasty studies. The Australian Safety and Efficacy Register of New Interventional Procedures – Surgical (ASERNIP-S) in 2003 (www.surgeons.org/asernip-s, accessed September 21, 2004) reported on the incidence of cement leakage and neurological deficits in studies on vertebroplasty. The original articles from this report were reviewed and the data were extracted to compare the incidences of cement leakage, neurological deficits, new fractures, and pulmonary embolism between balloon kyphoplasty and vertebroplasty (Table 11).

Table 11: Numbers and Rates of Complications In Vertebroplasty Studies.

| Study, Year | N/No. of Vertebrae Treated | Follow-up in Months, Mean (Range) | Cement Leakage, n/N (%) | Serious Neurological Deficit, n/N (%) | Symptomatic Pulmonary Embolism, n (%) | New Vertebral Fracture, n |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amar et al. ,(50)* 2001 |

97/258 | 14.7 (2–35) | 7/97 (7.2) | 4/97 (4.1) | 1 (1) | 21 patients |

| Barr et al., (51)* 2000 |

47/84 | 18 (2–42) | Not reported | 4/47 (8.5) | 0 | 1 |

| Cortet et al., (38) 1999 |

16/20 | 6 | 11/16 (69) | 0 | Not reported | 0 |

| Cyteval et al., (52) 1999 |

20/23 | 6 | 8/20 (40) | 1/20 (5) | 0 | 5 |

| Grados et al, (53) 2000 |

25/34 | 48 (12–84) | 7/25 (28) | 0 | 0 | 34 |

| Gaughen et al., (54)* 2002 |

48/84 | 1 | 50/84 vertebrae (59.5) |

0 | 0 | Not reported |

| Heini et al., (55) 2000 |

17/45 | Minimum of 12 | 8/45 vertebrae (18) |

0 | 0 | 2 |

| Jensen et al., (56) 1997 |

29/47 | No follow-up | 10/29 (34.5) | 1 | 0 | Not reported |

| Lin et al., (57) 2002 |

23/29 | 1.8 | 1/23 (4.3) | 1 (4.3) | 0 | Not reported |

| McGrow et al., (58)* 2002 |

100/156 | 21.5 | Not reported | 0 | 0 | Not reported |

| Peh et al., (59) 2002 |

37/48 | 11 | 21/48 vertebrae (43.7) |

0 | 0 | Not reported |

| Peters et al., (36) 2002 |

42/56 | 1.5 | 11/42 (26.1) | 5 (11.9) | 0 | 4 |

| Ryu et al., (60) 2002 |

159/347 | 3 (102 patients) | 64/159 (40.3) | 17/159 (10.7) | 0 | Not reported |

| Tsou et al., (61) 2002 |

16/17 | 1-12 | 2/16 (12.5) | 1/16 (6.2) | 0 | Not reported |

| Uppin et al.(62) 2003 |

177/400 | 10 (maximum) | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | 36 (2/3 within 30 days of the procedure) |

| Vasconcelos et al., (63)* 2002 |

137/205 | 1 week | 18/205 (8.7) procedures |

1/137 (0.73) | 0 | Not applicable |

| Wenger et al., (64) 1999 |

13/21 | 3 | 9/13 (69) | 1/13 (8) | 0 | 1 |

| Wong et al., (65) 2002 |

22/34 | 6 | 4/22 (18) | 1/22 (4.5) | 0 | Not reported |

| Zoarski et al., (66) 2002 |

30/54 | 15–18 | 1/30 (3.3) | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Total | 232/874 (26.5) | 37/953 (3.9) | 1/862 (0.1) | 107/512 (21%) |

In these studies, more than 80% of the patients had osteoporotic VCFs.

Because there were no RCTs comparing the rate of cement leakage, neurological deficits and new fractures between balloon kyphoplasty and vertebroplasty, the Medical Advisory Secretariat compared the rates in the kyphoplasty studies in this assessment with those from the vertebroplasty studies shown in Table 11. This comparison shows that studies on balloon kyphoplasty reported lower incidence of cement leakage, neurological deficits and new fractures compared to those reported by studies on vertebroplasty.

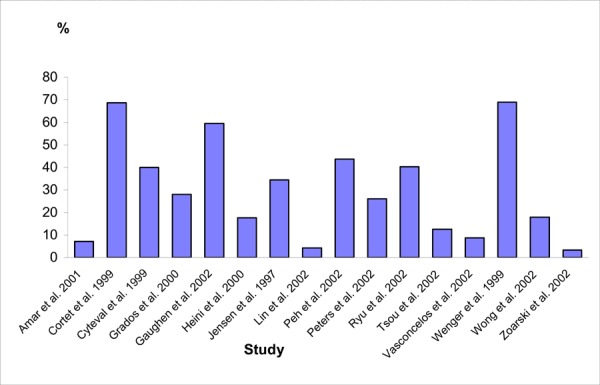

Figure 6 shows the rates of cement leakage across the vertebroplasty studies (in which more than 80% of the patients had osteoporosis).

Figure 6: Rate of Cement Leakage in Vertebroplasty Studies.

Summary of Medical Advisory Secretariat Review

Findings from the 1 comparative study (33) (level 3a evidence) in this review showed that balloon kyphoplasty significantly improved patients’ outcomes compared with conservative medical care.

Patients who had balloon kyphoplasty reported a significant reduction in pain that was maintained during follow-up (6 months), whereas pain scores did not change in the control group.

Patients who had balloon kyphoplasty did not need pain medication after 3 days. In the control group, about one-half of the patients needed more pain medication in the 4 weeks after the procedure. After 6 weeks, 82% of the patients in the control group were still taking pain-relief medication regularly.

Adjacent fractures happened more frequently in patients who received conservative medical treatment than in those who had balloon kyphoplasty.

The case series reported on several important clinical outcomes. These are summarized below.

Pain

Four studies on patients with osteoporosis and 1 study on patients with multiple myeloma or primary cancers used the VAS to measure pain preoperatively and postoperatively. All of these studies reported that patients had significantly lower pain scores after balloon kyphoplasty, which were maintained during follow-up. (39;41;42;44;49)

Likewise, 2 other studies (15;45) on patients with osteoporosis used the VAS to measure pain and found a significant improvement in pain scores; however, they did not provide follow-up data.

Vertebral body height

For patients with osteoporosis, all 5 of the studies that assessed vertebral body height reported a significant improvement after balloon kyphoplasty. (41;43-46) Ledlie et al. (41) provided 1-year follow-up data for 26 patients. They found a significant improvement in vertebral body height at 6 months and 1 year for both the anterior and midline measurements.

For patients with multiple myeloma or metastatic disease, 2 studies found that vertebral body height was significantly restored after balloon kyphoplasty. (47;49) In another study, (48) the researchers reported complete height restoration in 9% of patients, a mean 56% height restoration in 60% of patients, and no appreciable height restoration in 31% of the patients who received balloon kyphoplasty.

Kyphosis correction

Four studies on patients with osteoporosis that assessed Cobb angles before and after balloon kyphoplasty reported a significant reduction in the degree of kyphosis after the procedure. (39;44-46) In these studies, the differences between preoperative and postoperative Cobb angles were 3.4°, 7°, 8.8°, and 9.9°.

Only 1 study (49) investigated kyphosis correction in patients with multiple myeloma or metastatic disease. The authors of this study reported a significant improvement (5.2°) in local kyphosis.

Quality of life

Four studies used the SF-36 to measure quality of life in patients with osteoporosis. In 2 of these studies, (42;43) there was significant improvement in most of the domains of the SF-36 (bodily pain, social functioning, vitality, physical functioning, mental health, and role functioning). Coumans et al. (42) found that general health declined, although not significantly, and Lieberman et al. (43) found that role emotional declined.

The studies that used the ODI found that the quality of life of patients improved after they had balloon kyphoplasty. In the study by Coumans et al., (42) the improvement was statistically significant. Similarly, Rhyne et al. (45) reported that patients’ quality of life improved significantly after they had kyphoplasty, as measured by the Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire. Finally, Phillips et al. (39) used a quality of life questionnaire and found that 62% of the patients that had received balloon kyphoplasty had returned to normal activities, whereas 2 patients had reduced mobility.

For patients with multiple myeloma or metastatic disease, Dudeney et al. (48) found that scores on the SF-36 scale in the domains of bodily pain, physical functioning, vitality, and social functioning improved significantly. Scores on general health, mental health, role physical, and role emotional did not improve.

Lane et al. (47) used the ODI to measure quality of life and reported a significant improvement in scores postoperatively and at 3 months follow-up.

Summary of Complications

For patients with osteoporosis:

The bone cement leaked in 37 (6%) of 620 treated fractures.

There were no reports of neurological deficits.

There were no reports of pulmonary embolism due to cement leakage.

-

There were 6 cases of cardiovascular events in 362 patients:

3 (0.8%) patients had myocardial infarction;

3 (0.8%) patients had cardiac arrhythmias

There was 1 (0.27%) case of pulmonary embolism due to deep venous thrombosis.

There were 20 (8.4%) cases of new fractures in 238 patients.

For patients with multiple myeloma or metastatic disease:

The bone cement leaked in 12 (9.6%) of 125 procedures.

There were no reports of neurological deficits.

Economic Analysis

Budget Impact Analysis

Balloon kyphoplasty requires anesthesia. Standard vertebroplasty requires sedation and an analgesic. Based on these considerations, the professional fees (Cdn) for each procedure is shown in Table 12.

Table 12: Professional Fees for Standard Vertebroplasty and Balloon Kyphoplasty.

| Standard Vertebroplasty | Balloon Kyphoplasty | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| $148.10: | Physician reimbursement for percutaneous vertebroplasty – first level per patient per day (physician service code = J016) | $148.10: | Physician reimbursement for percutaneous vertebroplasty – first level per patient per day (physician service code = J016) | ||

| 4 | anesthetist units | ||||

| x | |||||

| $11.77 | unit fee for anesthetists | ||||

| = 47.08: | anesthetist reimbursement alongside (physician service code = J016) | ||||

| $74.05: | Physician reimbursement for each additional vertebral level (maximum of 3 per patient day) (physician service code = J054) | $74.05: | Physician reimbursement for each additional vertebral level (maximum of 3 per patient day) (physician service code = J054 | ||

| 52.9%: | % of percutaneous vertebroplasties that also have J054 | 52.9%: | % of percutaneous vertebroplasties that also have J054 | ||

| $187.24: | Total professional medical fees per case | $234.32: | Total professional medical fees per case | ||

Balloon kyphoplasty has a sizable device cost add-on of $3,578 (the device cost per case) that standard vertebroplasty does not have. Therefore, the up-front cost (i.e., physician’s fees and device costs) is $187 for standard vertebroplasty and $3,812 for balloon kyphoplasty. (All costs are in Canadian currency.)

Downstream Costs

There are differences in adverse outcomes associated with each procedure, which has an impact on downstream costs. Along with the risk of developing new fractures (21% for vertebroplasty vs. 8.4% for balloon kyphoplasty), there is a risk of neurological complications (3.9% for vertebroplasty vs. 0% for balloon kyphoplasty), pulmonary embolism (0.1% for vertebroplasty vs. 0% for balloon kyphoplasty), and cement leakage (26.5% for vertebroplasty vs. 6.0% for balloon kyphoplasty). Accounting for these risks, and the base costs to treat each of these complications, the expected downstream costs are estimated at less than $500 per case. Therefore, the expected total direct medical cost per patient is about $700 for standard vertebroplasty and $4,300 for balloon kyphoplasty.

Kyphon, the manufacturer of the inflatable bone tamps has stated that the predicted Canadian incidence of osteoporosis in 2005 is about 29,000. The predicted incidence of cancer-related vertebral fractures in 2005 is 6,731. Based on Ontario having about 38% of the Canadian population, the incidence in the province is likely to be about 11,000 for osteoporosis and 2,500 for cancer-related vertebral fractures. This means there could be as many as 13,500 procedures per year in Ontario; however, this is highly unlikely because most of the cancer-related fractures likely would be treated with medication. Given a Given a $3,6001 incremental direct medical cost associated with balloon kyphoplasty, the budget impact of adopting this technology could be as high as $48.6 million per year; however, based on data from the Provider Services Branch, about 120 standard vertebroplasties are done in Ontario annually. Given these current utilization patterns, the budget impact is likely to be in the range of $430,000 per year. This is because of the sizable device cost add-on of $3,578 (the device cost per case) for balloon kyphoplasty that standard vertebroplasty does not have.

Appraisal

Policy Considerations

Patient Outcomes – Medical, Clinical

Other treatments for osteoporotic VCFs are medical management and open surgery. In cases without neurological involvement, the medical treatment of osteoporotic VCFs comprises bed rest, orthotic management, and pain medication. However, these treatments are not free of side effects. Bed rest over time can result in more bone and muscle loss, and can speed the deterioration of the underlying condition. Medication can lead to altered mood or mental status. Surgery in these patients has been limited because of its inherent risks and invasiveness, and the poor quality of osteoporotic bones. However, it may be indicated in patients with neurological deficits.

Neither of these vertebral augmentation procedures eliminates the need for aggressive treatment of osteoporosis. Osteoporotic VCFs are often under-diagnosed and under-treated. A survey of physicians in Ontario (1) who treated elderly patients living in long-term care homes found that although these physicians were aware of the rates of osteoporosis in these patients, 45% did not routinely assess them for osteoporosis, and 26% did not routinely treat them for osteoporosis.

Management of the underlying condition that weakens the vertebral bodies should be part of the treatment plan. All patients with osteoporosis should be in a medical therapy program to treat the underlying condition, and the referring health care provider should monitor the clinical progress of the patient.