Executive Summary

The objective of this analysis was to evaluate the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the bispectral index (BIS) monitor, a commercial device to assess the depth of anesthesia.

Conventional methods to assess depth of consciousness, such as cardiovascular and pulmonary measures (e.g., heart rate, systolic/diastolic blood pressure, mean arterial pressure, respiratory rate, and level of oxygen in the blood), and clinical signs (e.g., perspiration, shedding of tears, and limb movement) are not reliable methods to evaluate the brain status of anesthetized patients. Recent progress in understanding the electrophysiology of the brain has led to the development of cerebral monitoring devices that identify changes in electrophysiologic brain activity during general anesthesia. The BIS monitor, derived from electroencephalogram (EEG) data, has been used as a statistical predictor of the level of hypnosis and has been proposed as a tool to reduce the risk of intraoperative awareness.

Anesthesia that is too light can result in the recall of events or conversations that happen in the operation room. Patients have recalled explicit details of conversations that happened while under anesthesia. This awareness is frightening for patients and can lead to post-traumatic stress disorder. Conversely, anesthesia that is too deep can cause hemodynamic disturbances necessitating the use of vasoconstrictor agents, which constrict blood vessels, to maintain normal blood pressure and cardiac output. Overly deep anesthesia can also result in respiratory depression requiring respiratory assistance postoperatively.

Monitoring the depth of anaesthesia should prevent intraoperative awareness and help to ensure that an exact dose of anaesthetic drugs is given to minimize adverse cardiovascular effects caused by overly large doses. Researchers have suggested that cerebral monitoring can be used to assess the depth of anesthesia, prevent awareness, and speed early recovery after general anesthesia by optimizing drug delivery to each patient.

Awareness is a rare complication in general anesthesia. The risk of intraoperative awareness varies among countries, depending on their anesthetic practices. In the United States, the incidence of intraoperative awareness is 0.1% to 0.2% of patients undergoing general anesthesia. The incidence of intraoperative awareness depends on the type of surgery. Trauma patients have reported the highest incidence of intraoperative awareness (11%–43%) followed by patients undergoing cardiac surgery (1.14%) and patients undergoing Cesarean section (0.9%).

The BIS monitor, licensed by Health Canada, is the first quantitative EEG index used in clinical practice as a monitor to assess the depth of anesthesia. It consists of a sensor, a digital signal converter, and a monitor. The sensor is placed on the patient’s forehead to pick up the electrical signals from the cerebral cortex and transfer them to the digital signal converter. A BIS score quantifies changes in the electrophysiologic state of the brain during anesthesia. In patients who are awake, a typical BIS score is 90 to 100. Complete suppression of cortical activity results in a BIS score of 0, known as a flat line. Lower numbers indicate a higher hypnotic effect. Overall, a BIS value below 60 is associated with a low probability of response to commands. There are several alternative technologies to quantify the depth of anesthesia, but only the BIS and SNAP monitors are licensed in Canada. The list price of the BIS monitor is $13,500 (Cdn). The sensors cost $773 (Cdn) for a box of 25.

Because intraoperative awareness and recall happen rarely, only 1 randomized controlled trial of all the studies reviewed, was adequately powered to show the impact of BIS monitoring. This was a large prospective, randomized, double-blinded, multicentre study that was designed to investigate if BIS-guided anesthesia reduces the incidence of intraoperative awareness. The study confirmed 2 cases of intraoperative awareness in the BIS group and 11 cases in the standard practice group. This difference was statistically significant (P =.022). There were 36 reports of possible awareness that were not confirmed by the study group (20 patients in the BIS group and 16 in the standard practice group).

Additionally, the results of small randomized controlled trials and prospective cohort studies show that, overall, BIS monitoring is relatively good at indicating the state of being alert; however, its algorithm does not accurately predict an unconscious state. BIS monitoring has low sensitivity for the detection of the state of being asleep, and it may show values higher than 60 in those already asleep. Therefore, an unknown percentage of patients will not be identified as being asleep and will receive anesthetics unnecessarily.

Based on the literature review, the Medical Advisory Secretariat concludes the following:

Prevention of awareness should remain a clinical decision for anesthesiologists to make based on their experience with intraoperative awareness in their practices.

Although BIS monitoring may have a positive impact on reducing the incidence of intraoperative awareness in the general population, its negative impact on individual patients may overshadow this positive outcome.

BIS monitoring is good at indicating an “alert” state, which is why it can reduce the incidence of intraoperative awareness; however, its algorithm does not accurately predict an “asleep” state. This means an unknown percentage of patients who are already asleep will not be identified because of falsely elevated BIS values. These patients will receive unnecessary dosage of anesthetics resulting in a deep hypnotic state.

Adherence to the practice guidelines will reduce the risk of intraoperative awareness.

Objective

The objective of this analysis was to evaluate the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the bispectral index (BIS) monitor, a commercial device to assess the depth of anesthesia.

Background

Clinical Need

In clinical practice, vital signs are used to monitor the depth of anesthesia. These measures do not indicate adequacy of anaesthesia reliably, because they can be influenced by various factors unrelated to the depth of anesthesia. Conventional methods to assess depth of consciousness, such as cardiovascular and pulmonary measures (e.g., heart rate, systolic/diastolic blood pressure, mean arterial pressure, respiratory rate, and level of oxygen in the blood), and clinical signs (e.g., perspiration, shedding of tears, and limb movement) are not reliable methods to evaluate the brain status of anesthetized patients. To quantify the level of sedation and anesthesia objectively, the intuitive solution is to monitor the brain directly. However, because the brain is a complex organ and there is as yet a limited understanding of consciousness, this is not possible.

Several techniques and devices have been proposed or tested as methods to determine depth of anesthesia. Since 1939, anesthesiologists have known about changes in the electroencephalogram (EEG) that are produced by anesthetic agents. (1) Recent progress in understanding the electrophysiology of the brain has led to the development of cerebral monitoring devices that identify changes in electrophysiologic brain activity during general anesthesia.

The BIS monitor, derived from EEG data, has been used recently as a statistical predictor of the level of hypnosis. It has been proposed as a tool to reduce the risk of intraoperative awareness. (1)

Intraoperative Awareness

Awareness may occur during general anesthesia. Patients have recalled explicit details of conversations that happened while under anesthesia. This awareness is frightening for patients and can lead to post-traumatic stress disorder. (2) Researchers have suggested that cerebral monitoring can be used to assess the depth of anesthesia, prevent awareness, and speed early recovery after general anesthesia by optimizing drug delivery to each patient. (3)

When ether was first successfully introduced, and performing surgery with little or no pain consequently became possible, awareness was not an issue. Subsequent to the advent and widespread use of neuromuscular blockades, awareness under general anesthesia has become an issue, because these agents do not diminish consciousness while preventing patient movement, the most common sign of light anesthesia.

Levels of Intraoperative Awareness

Jones (4) described three levels of intraoperative awareness: conscious awareness with pain, conscious awareness without pain, and perception without conscious awareness. Explicit recall refers to the spontaneous or conscious recollection of previous experiences that may occur with or without the sensation of pain. Implicit recall, by contrast, refers to the changes in behaviour that are produced by previous experiences but without conscious recollection of these experiences.

Psychological Sequelae of Intraoperative Awareness

Awareness under general anesthesia can be frightening. Patients who report having been aware during surgery have described sensations of paralysis, pain, anxiety, helplessness, and powerlessness. (2) Feeling the endotracheal tube being placed in the trachea and being unable to signal distress and alert the anesthesiologist can create overwhelming anxiety and panic. Nonparalyzed patients, however, are less likely to experience anxiety during an episode of intraoperative awareness. (5)

Incidence of Intraoperative Awareness

Awareness is a rare complication in general anesthesia. The risk of intraoperative awareness varies among countries, depending on their anesthetic practices. In the United States, the incidence of intraoperative awareness is 0.1% to 0.2% of patients undergoing general anesthesia. (6) In Europe, a large prospective trial (7) investigated conscious awareness in 11,785 patients who underwent general anesthesia. The incidence of intraoperative awareness with explicit recall was 0.1% without the use of neuromuscular blocking agents. With these agents, it was 0.18%.

Another European study (8) reported the incidence of recall of intraoperative events and dreams during operation in nonobstetric surgeries as 0.2% and 0.9%, respectively. A study from Saudi Arabia (9) investigated the incidence of intraoperative awareness in 4,368 patients undergoing surgery. In this study, all patients were given a premedicant (a drug used before anesthesia). Anesthetic equipment with a built-in end-tidal anesthetic gas monitor was checked preoperatively. This study reported no incidence of intraoperative awareness and 100% patient satisfaction.

Research also suggests the incidence of intraoperative awareness depends on the type of surgery. A study from Finland (10) investigated awareness in 929 patients who had cardiac surgery. The incidence of definite awareness with recall was 0.5%, and the incidence of possible recall was 2.3%. A lower dose of midazolam, a sedating drug, was used in the patients who experienced awareness and recall.

In Ontario, a higher incidence of intraoperative awareness was reported in patients undergoing cardiac surgery. (11) This study investigated awareness in 837 patients who underwent cardiopulmonary bypass surgery. Seven hundred patients responded to a structured postoperative interview. The authors reported an incidence of intraoperative awareness of 1.14%.

Additionally, in a survey of 3,000 patients who had general anesthesia for Cesarean section, an incidence of about 0.9% for any recall and 7% for dreaming was reported. (12) So far, trauma patients have reported the highest incidence of intraoperative awareness (11%–43%). (13)

The incidence of intraoperative awareness with explicit recall of severe pain generally is low: fewer than 1 event in 3,000. (14)

Impact of Anesthetic Techniques on Incidence of Intraoperative Awareness

Examining the anesthetic technique is important to understand the cause of awareness during anesthesia. The highest incidence of intraoperative awareness is associated with the use of receptor-mediated drugs, such as opioids, benzodiazepines, or the weak anesthetic nitrous oxide (also known as laughing gas), given alone or in combination. In contrast, volatile anesthetics such as isoflurane, enflurane, desflurane, and halothane; and potent intravenous anesthetics such as thiopental, etomidate, and propofol in appropriate concentrations successfully block perception. Volatile agents are markedly more effective than nitrous oxide at reducing awareness. Their concentration can be controlled by monitoring end-expiratory gas concentrations.

Causes of Intraoperative Awareness

The cause of awareness is usually traceable to 1 of 3 factors: (5)

Light anesthesia due to the following causes:

Specific anesthetic techniques such as the use of nitrous oxide, opioids, and muscle relaxants

Difficult intubation

Premature discontinuation of anesthetic

Myocardial depression

Cesarean section

Machine malfunction or misuse of the technique as follows:

Failure to check equipment

Vaporiser and circuit leaks

Errors in intravenous infusion

Accidental administration of muscle relaxants to patients who are awake

Increased anesthetic requirement for the following reasons:

Individual variability in anesthetic requirements

Chronic alcohol, opioid, or cocaine abuse

Prevention of Intraoperative Awareness

The AIMS (Anesthetic Incident Monitoring Study) database in Australia (15) showed that, from 8,372 incidents reported, there were 50 cases of definite awareness and 31 cases of a high probability of awareness. Each group was further subdivided into incidents with no obvious preventable cause, incidents with a clearly documented reason for awareness, and incidents caused by drug error. There were 13 cases (16%) with no obvious cause. In 36 cases (44.5%), the incidents were due to low inspired volatile concentration or inadequate hypnosis, and in 32 cases (39.5%), the incidents were due to drug error. The procedure was classed as an emergency in 25 cases. In the group of low inspired volatile concentration (n=36), 16 cases (44%) involved a failure of volatile anesthetic or nitrous oxide delivery due to equipment malfunction. Prolonged attempts at tracheal intubation contributed to 5 intraoperative awareness incidents.

The largest group of incidents was due to drug error, mostly consisting of switching 2 same-size syringes containing drugs, and thus giving patients the wrong drugs. This caused the inadvertent paralysis of patients who were awake and suggests that checking the syringes more carefully before injection would minimize this error.

Components of Anesthesia

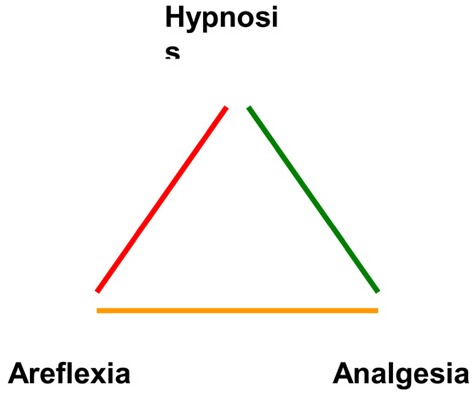

The aim of general anesthesia is to produce the following (Figure 1):

Figure 1: Components of Anesthesia.

Hypnosis (lack of awareness and recall)

Analgesia (lack of response to noxious stimuli, or pain relief)

Areflexia (lack of movement, or a quiet surgical field)

When administering general anesthesia, an anesthesia provider aims to provide a state of sedation and help the patient avoid pain. Hypnotic drugs may produce sleep and unawareness without suppressing movement. Suppression of movement in response to noxious stimuli is largely mediated by an anesthetic’s action on the spinal cord, rather than by higher brain centres. (16) Volatile agents may have a suppressing effect on the spinal cord. Hypnotic agents such as thiopental and propofol, however, may induce sleep and large changes in cortical EEG readings without having suppressing effects on the spinal cord or movement. (3) Opioid analgesics may suppress movement at doses that have only a small effect on an EEG. (17)

The hypnotic component of anesthesia differs from the analgesic component. A satisfactory anesthetic state can be obtained with a balance of hypnotic drugs (e.g., volatile or intravenous anesthetic agents) that produce hypnosis and analgesic drugs (e.g., opioids) that relieve pain and suppress movement. A well-balanced anesthesia reduces the amount of anesthetic used, the time to extubation (the removal of a previously inserted endotracheal tube), the length of stay in the recovery area, and the cost of the procedure.

Depth of Anesthesia

General anesthesia is a drug-induced loss of consciousness during which patients cannot be aroused. During anesthesia, the cardiovascular function of patients may be impaired, and they may need airway maintenance and ventilatory assistance. There is no objective scale that measures “too light” or “too deep” anesthesia. Anesthesia that is too light can result in recall of events or conversations that happen in the operation room. Conversely, anesthesia that is too deep can cause hemodynamic disturbances necessitating the use of vasoconstrictor agents, which constrict blood vessels, to maintain normal blood pressure and cardiac output. Overly deep anesthesia can result in respiratory depression requiring respiratory assistance postoperatively. Monitoring the depth of anaesthesia should prevent intraoperative awareness and help to ensure that an exact dose of anaesthetic drugs is given to minimize adverse cardiovascular effects caused by overly large doses.

Evaluation of Consciousness:

The Isolated Forearm Technique In clinical research, most of the studies that have evaluated the effectiveness of consciousness monitors to reduce the incidence of intraoperative awareness have used the Tunstall isolated forearm technique (18) to detect awareness during sedation or anesthesia. In this method, a tourniquet is used to separate the circulation of blood in the forearm from systemic circulation, and then muscle relaxants are administered. Because the muscle relaxants do not reach the hand, a patient can move his or her hand and respond to questions by squeezing the investigator’s hand. This method should be used for a short period. With longer duration, this technique becomes less reliable because anaerobic metabolism impairs neuromuscular function.

New Technology Being Reviewed: Bispectral Index Monitor

The BIS monitor is the first quantitative EEG index introduced into clinical practice as a monitor to assess the depth of anesthesia. BIS technology measures only the hypnotic component of anesthesia. It consists of a sensor, a digital signal converter, and a monitor. The sensor is placed on the patient’s forehead to pick up the electrical signals from the cerebral cortex and transfer them to the digital signal converter. BIS technology is available as a stand-alone unit, or as a modular solution integrated into the manufacturer’s monitoring system.

The BIS monitor integrates various descriptors into a single variable. During the development of the device, various subparameters of EEG activity were derived empirically from a prospectively collected database of the EEGs of anesthetized volunteers, who also provided clinically relevant endpoints. (19) This database contains information from about 1,500 anesthetic administrations (almost equal to 5,000 hours of recordings) that used a variety of anesthetic protocols. (1) EEGs were recorded onto a computer and were time-matched with clinical endpoints and, where available, drug concentrations.

During this process, the raw EEG data were inspected, and sections containing artifacts were rejected. Artifacts are electrical activities arising from sites other than the brain, such as from the body (e.g., eye movement and jaw clenching), the environment, or the equipment. Several EEG features were identified as patients went from an awake to a fully anesthetized state. Multivariate statistical models were used to derive the optimal combination of these features. This information was then transferred into a linear scale from 0 to 100.

Data from the first 2 clinical studies (20;21) were combined to form the database from which BIS version 1.1 was derived. BIS versions 2.0, 3.0, and 4.0 (the most recent) were developed later as the device was reformulated.

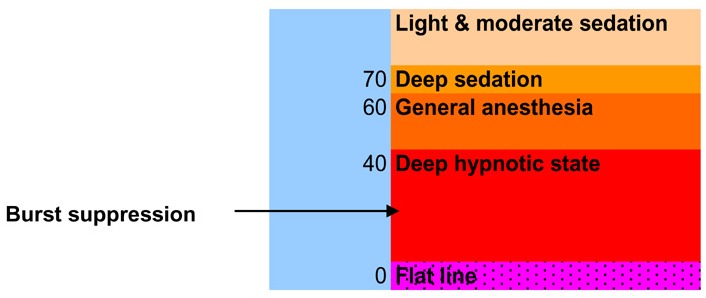

A BIS score is not a real physiologic measurement such as mm Hg. BIS values quantify changes in the electrophysiologic state of the brain during anesthesia. In patients who are awake, a typical BIS score is 90 to 100. Complete suppression of cortical activity results in a BIS score of 0, known as a flat line. BIS scores decline during sleep, (22) although not to the degree caused by high doses of anesthetics. Lower numbers indicate a higher hypnotic effect. Overall, a BIS value below 60 is associated with a low probability of response to commands. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2: Bispectral Index Scores.

Because a BIS score is a number derived from the preceding 15 to 30 seconds of EEG data, it indicates the state of the brain just before the reading. Furthermore, brain state, as measured by BIS, may change rapidly in response to strong stimulation. (3)

Alternative Technologies

Alternative technologies to quantify the depth of anesthesia include, but are not limited to, the following:

SNAP EEG monitor system

Auditory Evoked Potential (AEP) monitor

Patient State Analyzer 4000 (PSA 4000)

Narcotrend

Spectral Edge Frequency 95 (SEF 95)

Automated Responsiveness Test (ART)

Regulatory Status

From the list of EEG-based monitors, only the BIS and the SNAP monitors have been licensed by Health Canada. Table 1 shows the regulatory information for these devices.

Table 1: Consciousness Monitors Licensed by Health Canada.

| Device | Class | Licence Number | Licence Name | Company (Location) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aspect Medical System EEG Monitor A-1050 with BIS | 3 | 5677 | Aspect Medical Systems EEG monitor with BIS | Aspect Medical Systems (Newton, MA, United States) |

| Aspect Medical System EEG Monitor 2000 XP with BIS | 3 | 5677 | Aspect Medical Systems EEG monitor with BIS | Aspect Medical Systems (Newton, MA, United States) |

| Aspect Medical System EEG Monitor A-2000 with BIS | 3 | 5677 | Aspect Medical Systems EEG monitor with BIS | Aspect Medical Systems (Newton, MA, United States) |

| SNAP EEG monitor system | 3 | 62703 | SNAP EEG monitor | Viasys Healthcare Inc., Neurocare Group, Nicolet Biomedical (Madison, WI, United States) |

Literature Review on Effectiveness

Objective

The purpose of this review was to assess the safety and effectiveness of BIS monitors to guide anesthesia in patients undergoing surgery.

Questions Asked

Do BIS monitors reduce the incidence of intraoperative awareness and recall in patients undergoing general anesthesia?

Do BIS monitors reduce the recovery time for patients undergoing general anesthesia?

Based on the evidence, would there be any risk or harm to patients undergoing general anesthesia if BIS monitors were used in routine clinical practice?

Methods

The Medical Advisory Secretariat searched MEDLINE and EMBASE for citations from January 1, 2000, to April 5, 2004.

Inclusion Criteria

Studies that investigated the incidence of intraoperative awareness and recall in anesthetized patients with the use of BIS monitoring

Studies that evaluated recovery time with the use of BIS monitoring

Studies that investigated only alternative EEG-based monitors that measure the depth of anesthesia and are licensed in Canada

Exclusion Criteria

Studies that compared BIS monitors only with similar technologies that are not licensed in Canada or studies that did not contain useful clinical information

Studies that assessed the drug concentration or titrating the administration of anesthetic agents using BIS monitors

Studies that compared the cost of the drugs used during BIS monitoring

Results of Literature Search

The initial search yielded 746 citations after duplicates were removed. When the selection criteria were applied and unrelated studies were excluded, 21 published articles remained and were included in this assessment.

In addition, the results of a large Australian randomized controlled trial (RCT) (23) that was available only as an abstract at the time of this evaluation was published in the Lancet on May 29, 2004. The full results of that study are included in this evaluation but are discussed separately.

Quality of Evidence

The level of evidence was assigned according to the scale based on the hierarchy by Goodman 1985. An additional designation “g” was added for preliminary reports of studies that were presented to international scientific meetings. (See Tables 2-A and 2-B.)

Table 2-A: Quality of Evidence of Studies on the Effectiveness of Bispectral Index Monitors in Reducing the Incidence of Intraoperative Awareness.

| Study Design | Level of Evidence |

No. Eligible Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Large RCT,* systematic reviews of RCTs | 1 | 1 |

| Large RCT unpublished, but reported to an international scientific meeting | 1(g)† | |

| Small RCT | 2 | 4 |

| Small RCT unpublished, but reported to an international scientific meeting | 2(g) | |

| Non-RCT with contemporaneous controls | 3a | |

| Non-RCT with historical controls | 3b | 1 |

| Non–RCT unpublished but reported to an international scientific meeting | 3g | |

| Surveillance (database or register) | 4a | |

| Case series (multisite) | 4b | 8 |

| Case series (single site) | 4c | |

| Case series unpublished but reported to an international scientific meeting | 4(g) | |

| Total | 14 |

RCT indicates randomized controlled trial.

indicates “grey literature” (preliminary reports of studies reported to international scientific meetings).

Table 2-B: Quality of Evidence of Studies on the Effectiveness of Bispectral Index Monitors in Reducing Recovery Time.

| Study Design | Level of Evidence |

No. Eligible Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Large RCT,* systematic reviews of RCTs | 1 | 10 |

| Large RCT unpublished but reported to an international scientific meeting | 1(g)† | |

| Small RCT | 2 | 1 |

| Small RCT unpublished but reported to an international scientific meeting | 2(g) | |

| Non-RCT with contemporaneous controls | 3a | |

| Non-RCT with historical controls | 3b | 1 |

| Non–RCT unpublished but reported to an international scientific meeting | 3g | |

| Surveillance (database or register) | 4a | |

| Case series (multisite) | 4b | |

| Case series (single site) | 4c | |

| Case series unpublished but reported to an international scientific meeting | 4(g) | |

| Total | 12 |

RCT indicates randomized controlled trial.

indicates “grey literature” (preliminary reports of studies reported to international scientific meetings).

Due to the low incidence of intraoperative awareness, only RCTs that had more than 2,000 patients were considered large RCTs for the investigation of this clinical endpoint. For recovery time, RCTs that had 60 patients or more were considered large. Those that did not base their randomization on the BIS and non-BIS monitoring techniques were categorized as level 4 evidence.

Fourteen studies (24–37) reported on the incidence of intraoperative awareness and recall. This included 4 RCTs. (25, 27–28, 31) One study (25) compared the results of a BIS-monitored group of patients with an historical group of similar patients from a previous study. This study was assigned level 3-b evidence. Studies in which randomization was based on a different anesthetic regimen were assigned level 4-c evidence. (26, 29, 32–37)

Eleven studies reported on the recovery time. Ten of these (25, 27-28, 31, 38–42, 44) were RCTs, including 4 that also reported on the incidence of awareness and recall. (24, 26–27, 30) One study was a prospective cohort (43) in which patients in the first phase of the study were considered the control group. This study was assigned level 3-b evidence.

As noted, the full results of the large Australian RCT (23) are included in this evaluation but are discussed separately.

The search identified 1 citation for the SNAP EEG monitor system. This was a feasibility study to evaluate the functionality of the device in an operating room setting; therefore, it was excluded.

Awareness and Recall

Table 3 shows a summary of the findings of the studies. Most of these studies compared the BIS-monitored group with the standard practice (SP) group. Standard practice is what physicians usually do in their practice.

Table 3: Summary of Findings From Studies on Awareness and Recall.

| Study (year) and location |

Ekman et al. (2004) Sweden (24) |

Kreuer et al. (2003) Germany (25) |

Kerssens et al. (2003) The Netherlands (26) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type of study | Prospective cohort – BIS-monitored patients were compared with an historical cohort (no BIS). |

RCT Group1: Narcotrend Group 2: BIS Group 3: SP |

Prospective cohort, part of an RCT on memory function during deep sedation |

| Quality of evidence | 3-b | 2 | 4-c |

| Primary purpose | To evaluate if BIS monitoring significantly reduces the incidence of awareness | To investigate the impact of Narcotrend monitoring on recovery times and propofol consumption compared with BIS monitors or standard anesthetic practice | To investigate response to command during deep sedation (BIS score of 60–70) and the ability of BIS monitors to indicate awareness and predict recall |

| Number of patients and type of surgery | Cases: 4,945 consecutive surgical patients with BIS monitoring Controls: 7,862 similar cases from an historical group with no cerebral monitoring |

120 patients (40 patients per group) Minor orthopedic surgery expected to last at least 1 hour |

56 healthy outpatients scheduled for elective surgery |

| Mean age, years (SD) | BIS: 50 (19) SP: 49 (19) |

BIS: 43.8 (4.2) SP: 46.1 (4.5) |

37 (10) (range, 19–58) |

| Female/male | BIS: 64/36 SP: 61/39 |

Equal number of males and females in each group (40) | 25/31 |

| Premedication | Premedication: Benzodiazepine: BIS: 967 (20%) No BIS: 1818 (23%) No premedication: BIS: 2306 (47%) SP: 2113 (27%) Opioid before induction: BIS: 4383 (89%) SP: 7550 (96%) |

Yes | No |

| Anesthetic agent | Propofol/thiopental for induction: BIS: 28/71 SP: 33/66 Concomitant regional anesthesia: BIS: 664 (13%) SP: 752 (10%) |

Propofol & remifentanil | Induction: Propofol Maintenance: Target controlled of propofol and alfentanil |

| Tracheal intubation | BIS: 4926 (100%) SP: 7796 (100%) |

Yes | Yes |

| Muscle relaxant | BIS: 4729 (96%) SP: 7752 (99%) |

Yes | Yes |

| Methods | Assessment by the anesthesiologists using a visual analogue scale as follows: - To what extent BIS monitors had been used to guide anesthesia - To what extent they felt confident that the BIS monitor worked properly Patients were interviewed on 3 occasions: - Before leaving the PACU - 1–3 days after operation. - 7–14 days after operation. |

A second independent investigator recorded BIS and Narcotrend data in intervals of 5 minutes. In the SP group, both monitors were covered behind a curtain and hidden from the attending anesthesiologist. |

Anesthesia was induced 30 minutes before surgery to avoid noxious stimulation and confounding effects. During this presurgical period, and while a hypnotic state was maintained at a BIS score of 60–70, responses to commands were investigated. BIS readings were taken on the following occasions:- No response to command - Equivocal response - Unequivocal response Anesthesia was induced 30 minutes before surgery. Once every 50 seconds, the observer called the patient’s name to determine his/her awareness. Patients were then asked to squeeze observer’s hand during the target-controlled fusion of the anesthetic agent. Patients who squeezed once were then asked to squeeze twice. Failure to squeeze twice was considered an equivocal response, whereas squeezing twice showed an adequate (unequivocal) response indicating awareness. Investigated the incidence of recall by Interviewing the patients |

| Intraoperative measurements | BIS scores | HR, systemic arterial pressure, respiratory rate, oxygen saturation, pulse oximetry, and end-tidal concentration of anesthetic carbon dioxide. | HR, MAP, spectral edge frequency, median frequency alpha, beta, theta, and delta power |

| BIS values | All staff members were instructed to maintain BIS values between 40 and 60 and to avoid values greater than 60 during induction and maintenance. Mean BIS values:During the induction phase: 46 (SD, 11) During the maintenance phase:38 (SD, 8) |

Not reported | BIS scores were maintained between 60 and 70 after induction/intubation and before surgery. During surgery, BIS values were maintained at about 45. |

| Incidence of recall | BIS: 2 patients (0.04%) Control: 14 patients (0.18%) P <.038 (77% reduction) |

No patient had intraoperative recall. | Response to commands: No response: 887 (82%) commands(15 patients) Equivocal responses: 56 (5%) commands Unequivocal responses: 139 (13%) commands Conscious recall: Of the 37 patients (66%) with an unequivocal response to commands, 9 (25%) reported conscious recall after recovery. For those who had conscious recall: BIS: 67.6 (SD, 5.5) HR: 72.9 (SD, 16.1) MAP: 87 (SD, 15.5) For those who did not have conscious recall: BIS: 67.1 (SD, 3.7) HR: 67.4 (SD, 11.7) MAP: 89.8 (SD, 17.9) |

| Accuracy data/prediction probability | N/A | N/A | N/A |

Table 3: Summary of Findings From Studies on Awareness and Recall (cont).

| Study (year) and location |

Recart et al. (2003) United States (27) |

Puri and Murphy (2003) India (28) |

Schneider et al. (2003) Germany (29) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type of study | RCT Group 1: BIS Group 2: AEP Group 3: SP |

RCT Group 1: BIS Group 2: SP |

RCT Patients were randomized into 4 groups according to 4 different anesthetic techniques. |

| Quality of evidence | 2 | 2 | 4-c |

| Primary purpose | To evaluate the impact of intraoperative monitoring with the BIS monitors or AEP on the use of desflurane, recovery time, and patient satisfaction | To investigate the impact of BIS monitoring on the hemodynamic stability and recovery time | To measure the ability of BIS monitoring to differentiate consciousness from unconsciousness during induction and emergence from anesthesia To measure the incidence of recall in surgical patients |

| Number of patients and type of surgery | 90 healthy patients undergoing laparoscopic general surgery | 30 adult patients undergoing valve replacement or coronary artery bypass grafting | 40 adult patients undergoing elective surgery |

| Mean age, years (SD) | BIS: 47 (17) AEP: 42 (14) SP: 46 (15) |

BIS: 38.25 (14.02) SP: 32.08 (13.84) |

Group 1: 35 (range, 22–54) Group 2: 53 (range, 22–72) Group 3: 44 (range, 28–66) Group 4: 51 (range, 21–79) |

| Female/male | BIS: 21/9 SP: 20/10 |

Not reported | Group 1: 2/8 Group 2: 6/4 Group 3: 2/8 Group 4: 6/4 |

| Premedication | Midazolam | Midazolam & morphine | None |

| Anesthetic agent | Propofol, fentanyl, and desflurane | Morphine, midazolam, thiopental, isoflurane, and nitrous oxide | Groups 1 & 2: Sevoflurane and remifentanil (different doses) Groups 3 & 4: Propofol and remifentanil (different doses) |

| Tracheal intubation | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Muscle relaxant | Yes | Yes | No |

| Methods | In the SP group, the anesthesiologists were not permitted to observe BIS or AEP index values during the intraoperative period. | In the BIS group, the anesthesiologist adjusted the isoflurane concentration using BIS. In the control group, the anesthesiologist was blinded to the BIS scores. Patients were interviewed on the first day after their operations to determine any recall. Planned BIS scores: During the surgery: 45–55 Last 30 minutes: 65–75 |

Every 30 seconds after the induction of anesthesia, investigators twice asked the patients to squeeze the investigators’ hands. • At the induction stage, anesthetics were given until loss of consciousness (LOC1) • After tracheal intubation, the anesthetics were stopped until return of consciousness (ROC1) • For surgery, anesthetics were restarted until LOC2 • After surgery, anesthetics were discontinued (ROC2) Patients were interviewed in the recovery room, within 48 hours after surgery, and 2–3 weeks after surgery. |

| Intraoperative measurements | AEP, HR, BP, ECG, pulse oximetry, and capnography | HR, ECG, BP, and pulse oximetry | PSI, SEF, MF, HR, MAP, O2saturation, and CO2 |

| Mean BIS values (SD) | BIS group: 49 (13) SP group: 40 (11) |

BIS group: 75 (5.59) SP group: 67.42 (15.24) |

LOC1 & LOC2: 66 (17) ROC1 & ROC2: 79 (14) LOC1: 62 (19) LOC2: 70 (16) ROC1: 78 5) ROC2: 81 4) Range of BIS values (these are approximate; the numbers were derived from the graph): LOC1: 25100 LOC2: 3395 ROC 1: 45100 ROC2: 53100 Between anesthetic groups: BIS values in patients receiving sevoflurane with dose remifentanil were significantly different from those in patients with propofol/remifentanil (groups 3 & 4 [P <.01]) |

| Incidence of recall | At the time of discharge from the PACU, and at the 24-hour follow-up evaluation, none of the patients reported recall of any intraoperative events. | BIS: 0 SP: 1 |

No patient remembered being aware. |

| Accuracy data/prediction probability | N/A | N/A | For detection of consciousness and BIS threshold of 60: Sensitivity: 90.6% Specificity: 26.3% PPV: 55.1% NPV: 73.7% Prediction probability (Pk) For detection of consciousness in the 4 groups (mean [SEM]): Group 1: 0.684 (0.61) Group 2: 0.668 (0.061) Group 3: 0.743 (0.056) Group 4: 0.721 (0.057)* *Significantly different from group 1, P <.01 |

Table 3: Summary of Findings From Studies on Awareness and Recall (cont).

| Study (year) and location |

Lehmann et al. (2003) Germany (30) |

Wong et al. (2002) Canada (Ontario) (31) |

Chen et al. (2002) United States (32) |

Schneider et al. (2002) Germany (33) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of study | RCT Group 1: BIS 50 Group 2: BIS 40 |

RCT Group 1: BIS Group 2: SP |

Prospective cohort | Prospective cohort |

| Quality of evidence | 4-c | 2 | 4-c | 4-c |

| Primary purpose | To compare the hemodynamics, oxygenation, intraoperative awareness and recall, and costs at 2 different levels of BIS values (50 and 40) | To investigate the effect of BIS monitors on patients’ recovery profiles, level of postoperative cognitive dysfunction, and anesthetic drug requirement | To compare the sensitivity and specificity of BIS monitoring with that of PSI on the ability of these devices to predict loss of consciousness and emergence from anesthesia | To see if a BIS baseline score of 50 to 60 prevents awareness of getting an endotracheal intubation |

| Number of patients and type of surgery | 62 patients undergoing first-time coronary artery bypass grafting | 60 elderly patients undergoing elective orthopedic surgery | 20 patients scheduled for elective laparoscopic surgical procedures | 20 non-neurosurgical patients |

| Mean age, years (SD) | BIS 50: 63.9 (8.7) BIS 40: 65.1 (8.6) |

BIS: 71 (5) SP: 70 (6) |

48 (16; range, 25–72) | Responders: 40 (15) Nonresponders: 45 (17) |

| Female/male | BIS 50: 8/24 BIS 40: 9/21 |

BIS: 10/21 SP: 10/19 |

11/9 | Responders: 3/5 Nonresponders: 3/9 |

| Premedication | Flunitrazepam | None | Midazolam IV | Midazolam |

| Anesthetic agent | Midazolam and sufentanil Propofol as rescue medication for BIS values above the intended limit |

Isoflurane | Induction: Propofol and fentanyl Maintenance: Desflurane and nitrous oxide |

Premedication: Midazolam Anesthetic: Propofol and alfentanil |

| Tracheal intubation | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Muscle relaxant | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Methods | Patients were randomized into 2 groups. The dosage of sufentanil/midazolam was adjusted to achieve a BIS level of 45–55 (group BIS 50) in 32 patients, and a BIS level of 35–45 (group BIS 40) in 30 patients. Mild hypothermia was applied. The following data points were defined: T0: awake before the induction of anesthesia T1: at steady state after the induction of anesthesia T2: after sternotomy T3: 30 minutes after the start of CPB T4: 5 minutes after CPBT5: at the end of surgery On the third postoperative day, patients were asked to answer a standardized questionnaire to measure explicit recall. |

In the SP group, the anesthesiologist was blinded to the BIS values. In the BIS group, the anesthesiologist adjusted the administration of anesthetics to maintain a BIS value of 50 to 60. |

3 staff anesthesiologists administered the anesthetics and monitored depth of anesthesia using standard clinical signs. BIS monitors were positioned out of their lines of sight and a second investigator ensured proper functioning of the monitors during the operation. The third investigator recorded data at specific time intervals. Each time that electrocautery was used, the incidence of its interference with the BIS monitors was recorded. State of consciousness was assessed by the ability of patients to follow commands to open their eyes and to squeeze the investigators’ hands. |

Prior to intubation, patients were tested for awareness in 1-minute intervals using the Tunstall isolated forearm technique. After at least 5 minutes of a constant BIS baseline value of 50 to 60 at unchanged infusion rates, patients were intubated. After intubation, infusion rates were kept constant for 3 minutes, then the study ended, and surgery was done. Patients were asked for recall before they left the recovery room and the next day on the ward. |

| Intraoperative measurements | HR, EEG, MAP, central venous pressure, mean pulmonary artery pressure, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure, cardiac output, and mixed venous oxygen saturation Cardiac index, stroke volume, left ventricular stroke work index, systemic vascular resistance, and pulmonary vascular resistance were calculated from standard formulas. Arterial and mixed venous blood gas analyses were done to calculate the index of oxygen delivery and the index of oxygen consumption according to standard formulas. |

HR, systolic and diastolic BP, MAP, and mental state scores | BIS, PSI, MAP, HR, oxygen saturation, end-tidal concentration of desflurane, and nitrous oxide | ECG, HR, BP < pulse oximetry, and end-tidal carbon dioxide |

| Mean BIS values (SD) | BIS 50 T0: 86 (6.3) T1: 54 (4.4) T2: 51 (4.1) T3: 54 (3.1) T4: 52 (3.9) T5: 52 (4.2) BIS 40 T0: 89 (6.4) T1: 41 (7.3) T2: 39 (5.6) T3: 39 (5.8) T4: 39 (6.3) T5: 41 (4.5) |

BIS: 53 (4) SP: 47 (7) |

Awake: 92 (10) At induction: 89 (12) Before intubation: 38(7) Before incision: 52(11) BIS monitoring differentiated between awake and anesthetized states and was a significant predictor of unconsciousness (P <.01) |

Between 50 and 60 |

| Incidence of recall | There was no explicit recall in either group. | No patient had awareness. | No patient reported recall at the 24-hour follow-up interview. | Before intubation, no patient responded to commands, and BIS scores were between 50 and 60 according to the protocol (responders: 52; nonresponders: 54). After intubation, 8 of the 20 patients showed awareness and squeezed the investigator’s hand in response to a command. No patient had recall in 2 hours in the recovery room and in 24 hours on the ward. |

| Accuracy data/prediction probability | N/A | N/A | ROC curve (area under the curve): 0.79 (SD, 0.04) |

Table 3: Summary of Findings From Studies on Awareness and Recall (cont).

| Study (year) and location |

McCann et al. (2002) United States (34) |

Yeo and Lo (2002) Singapore (35) |

Tsai et al. (2002) Taiwan (36) |

Sleigh et al. 2001 New Zealand (37) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of study | Prospective cohort | Observational | RCT | Prospective cohort |

| Quality of evidence | 4-c | 4-c | 4-c | 4-c |

| Primary purpose | To measure the incidence of recall during the intraoperative wake-up examination in patients undergoing 2 different anesthesia techniques (isoflurane [group 1] or no isoflurane [group 2]) | To examine the adequacy of the general anesthetic technique for avoiding explicit recall without the knowledge of BIS scores | To compare the effects of isoflurane or propofol supplementation on the BIS index | To compare the ability of BIS monitors to differentiate the awake and anesthetized states during the induction of general anesthesia with: • components of BIS (Beta ratio, SyncFastSlow) • SE50d • SE50d30Hz |

| Number of patients and type of surgery | 34 children and adolescents undergoing scoliosis surgery | 20 patients undergoing Cesarean section | 24 healthy patients undergoing elective Cesarean section (12 per group) | 84 patients undergoing routine surgery and 9 healthy volunteers |

| Mean age, years (SD) | 14.3 (2.8) | 31 (5.7) | Isoflurane: 33.46 (1.33) Propofol: 33.42 (1.79) |

Patient group: 57 (9) |

| Female/male | Not reported | All female | All female | Patient group: 52/32 |

| Premedication | Midazolam IV The mean dose of midazolam during the maintenance of anesthesia and before the wake-up test was significantly lower in group 1 compared with the dose in group 2. |

Ranitidine | Glycopyrrolate | Patient group: Oral: Midazolam (n=3) Intravenous: Midazolam (n=42) Fentanyl (n=67) Droperidol (n=5) |

| Anesthetic agent | Induction: fentanyl and thiopentone or propofol Maintenance: nitrous oxide, fentanyl, and isoflurane (Isoflurane was not administered in group 2.) |

Thiopentone, isoflurane, nitrous oxide, and morphine | Group 1: isoflurane, fentanyl, and droperidol Group 2: propofol, nitrous oxide, fentanyl, and droperidol |

Patient group: Induction agents: propofol (n=63), thiopentone (n=13), and etomidate (n=8) |

| Tracheal intubation | Yes (for both groups) | Yes | Yes | Patient group: Yes |

| Muscle relaxant | Yes (for both groups) | Yes | Yes | Patient group: Suxamethonium (n=7) Rocuronium (n=31) |

| Methods | Applied 2 anesthetic techniques: • Group 1 had isoflurane • Group 2 had no isoflurane BIS reading: • Before starting the wake-up test (T1) • At patient movement to command (T2) • After anesthetizing patients again after the wake-up test (T3) To minimize blood loss, controlled hypotension was used for all patients (55–65 mm Hg). During anesthesia and when patients moved to a command, the patients were told to remember a specific colour (teal). Anesthesiologists were blinded to the changes in BIS scores during the surgery. On the second postoperative day, patients were interviewed for recall, pain during surgery, and recall of the color specified at the time of the wake-up test. |

All anesthesiologists were blinded to the BIS values during the operation. Patients were interviewed in the recovery room and on the first postoperative day for recall or awareness. |

After delivery, patients were randomly assigned to 1 of the 2 anesthetic groups (isoflurane or propofol). | The clinical stages were defined as follows: Awake: start time LOC: time of loss of consciousness determined by a failure to respond to verbal commands (repeated twice) LOC 60: LOC+60 seconds Surgery: start of surgery The clinical anesthetist was blinded to the EEG monitoring. |

| Intraoperative measurements | BIS, HR, MAP, CO2, and end-tidal gas concentration | HR, MAP, ECG, pulse oximetry, end-tidal CO2, and end-tidal isoflurane concentration | HR, BP, and MAP | BIS, EMG, SEF, SE50d, SE50d30Hz, Beta ratio, SyncFastSlow, total bispectral score, and high bispectral score |

| BIS values | 37 wake-up tests were performed in 34 patients. Overall means (SD): T1: 72 (8) T2: 90 (8) (T2 vs. T1and T2, P <.001) T3: 54 (19) (T3 vs. T1, P <.001) T1: Group 1: 69.7 (7.7) Group 2: 75.6 (8) (P = .05) T2: Group 1: 88.4 (8.9) Group 2: 92.9 (5.9)(NS) T3: Group 1: 51.8 (19.9) Group 2: 58.2 (16)(NS) A significant increase in BIS score from T1 to T2 was observed in both groups (P <.001), and a significant decrease in BIS score from T2 to T3 was observed (P <.01). There were no significant differences in T2 or T3 BIS scores between the 2 groups. |

At skin incision: median, 70 At intubation, uterine incision and delivery: median, 60 (range, 52–70) |

Patients in the isoflurane group had higher cumulated mean BIS index values than the patients in the propofol group during the maintenance of anesthesia. | Awake: 97 (95–98) LOC: 94 (87–97) LOC 60: 56 (39–75) Surgery: 48 (39–67) Note: Values are medians (range, 25thto 75th percentile) |

| Incidence of recall | No patients recalled intraoperative pain. Patients did not recall intraoperative events before or after the wake-up test. All patients had a satisfactory postoperative recovery without significant morbidity. 6 patients had explicit auditory recall (17.6%). 1 patient in group 1 recalled the wake-up test but not the colour. 5 patients (2 in group 1 and 3 in group 2) recalled the specified colour. |

No patient experienced intraoperative dreams, recall, or awareness. | No patient from either group reported recall of the operative procedure. | N/A |

| Accuracy data/prediction probability | N/A | N/A | N/A | For detection of unconsciousness: Sensitivity: 61% Specificity: 98% PPV: 97% NPV: 75% ROC curve (areaunder the curve): 0.95 (SE, 0.12) |

Abbreviations: AEP indicates auditory evoked potential (awareness monitor); awareness, intraoperative awareness; BIS, bispectral index; BP, blood pressure; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; CPB, cardiopulmonary bypass; CO2, carbon dioxide; ECG, electrocardiogram; EEG, electroencephalogram; EMG, electromyogram; HR, heart rate; IV, intravenous; LOC, loss of consciousness; MAP, mean arterial blood pressure; MF, median frequency (awareness monitor); NA, not applicable; NPV, negative predictive value; NS, not significant; O2, oxygen; PACU, post anesthesia care unit; Pk, prediction probability; PPV, positive predictive value; PSI, patient state index (awareness monitor; RCT, randomized controlled trial; ROC, return of consciousness; SEF, spectral edge frequency (awareness monitor); SP, standard practice.

In the 3 RCTs (25, 27, 31) that randomized patients to either BIS monitoring or SP, no patient had intraoperative awareness or recall. In 1 RCT, (28) 1 patient in the SP group undergoing cardiac surgery had intraoperative awareness. The prospective cohort studies reported no incidence of intraoperative awareness. In a study (26) that investigated the response to command of patients in deep sedation (BIS scores of 60–70) prior to surgery, the incidence of recall was 16%. In a study (34) that did a wake-up test in patients having spinal surgery, the incidence of recall was 17.4%.

Because awareness during general anesthesia and recall of intraoperative events happen rarely, adequately powered trials are needed to show the impact of consciousness monitors on awareness in anesthetized patients. The sample size for such studies requires knowledge of the effectiveness of BIS monitors in reducing the incidence of intraoperative awareness.

According to one estimate, (38) if the incidence of intraoperative awareness in the general population is 1 in 1,000, and BIS monitoring is 90% effective at preventing intraoperative awareness, then a trial would need about 21,000 patients. If BIS monitoring is only 50% effective at preventing intraoperative awareness, however, then the required estimated sample size is about 82,000. Because the required number of patients decreases with an increase in the incidence of intraoperative awareness, it is more feasible to conduct a study that involves only patients at high risk of intraoperative awareness.

Ekman et al. (24) reported that significantly fewer patients in the BIS-monitored group had explicit recall compared with an historical control group (0.04% vs. 0.18%, P < .038). This corresponds to a 77% reduction in the incidence of intraoperative awareness in the BIS-monitored group. This finding is not surprising, because patients in this study were maintained in a deep anesthetic state, and the anesthesiologists were told to avoid BIS values over 60 during induction and maintenance. The results showed that during the maintenance phase, the mean BIS score was 38 (SD, 8). According to the BIS monitoring guidelines from the manufacturer, values below 40 indicate a deep hypnotic state and are not recommended for surgical procedures.

Kerssens et al. (26) used the isolated forearm technique and investigated patients’ response to command during deep sedation for 30 minutes before the start of surgery. At this time, the BIS values were maintained at 60 to 70. No response to command was observed to 887 commands (82%). BIS monitoring failed to discriminate between no response and equivocal response (63.2 and 64.3, respectively). Furthermore, patients with or without recall had similar mean BIS values (67.6 compared with 67.1).

Schneider et al. (33) investigated if a BIS score between 50 and 60 prevents awareness during endotracheal intubation. In this study, 8 of the 20 patients responded to a command to squeeze the investigator’s hand, but none of them experienced recall within 2 hours in the recovery room and within 24 hours on the ward. Those who responded and those who did not respond had similar BIS values. The median BIS score for responders was 52 (range, 51–58); for non-responders, it was 54 (range, 52–57). Those who did and did not respond clearly were in different hypnotic states, but BIS monitoring failed to differentiate between the levels of hypnosis in these patients. In another study by Schneider et al., (29) patients who were unconscious had BIS values higher than 60 (see Table 3). The results of this study will be discussed in detail further in this review.

McCann et al. (34) studied 34 children and adolescents undergoing scoliosis surgery. Common methods that have been used to monitor spinal cord function during this type of surgery are somatosensory evoked potentials and intraoperative wake-up tests. The authors indicated that at their centre an intraoperative wake-up test is performed routinely to monitor voluntary motor function of the lower limbs during surgery. During the wake-up test, the anesthetic depth is gradually lightened to the point that patients are able to respond to verbal commands. The controlled hypotension technique is also used during this type of surgery. This change in hemodynamic parameters makes it difficult to assess the depth of anesthesia in these children.

In McCann’s study, the mean BIS value during spinal surgery and immediately before the wake-up test was 72 (SD, 8), and a postoperative interview showed that no patient recalled intraoperative pain. Furthermore, patients who did not have isoflurane had significantly higher BIS values compared with those that had isoflurane at T1 (i.e., prior to the wake-up test during surgery); however, there was no difference in the incidence of recall between the 2 groups.

In Yeo and Lo’s study, (35) patients having Cesarean sections had median BIS values of 70 or lower. The report showed that the amount of anesthetic was adequate, because no patient had intraoperative awareness or recall.

Lehmann et al. (30) studied 62 patients undergoing first-time coronary artery bypass graft surgery at 2 levels of anesthesia. Patients were randomized into 2 groups. The aim was to achieve a BIS level of 40 to 45 in the “BIS 50” group, and a value of 35 to 45 in the “BIS 40” group. Neither group reported explicit memory during anesthesia. Significantly more propofol was used in the BIS 40 group. However, more patients in this group needed norepinephrine (a vasoconstrictor agent) during and 5 minutes after cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB; a machine that takes over the function of the heart and lungs during surgery), compared with the patients in the BIS 50 group.

Table 4 shows the predicted and observed outcomes of the reviewed studies.

Table 4: Predicted and Observed Outcomes of Bispectral Index Monitoring From the Reviewed Studies.

| Stage of Surgery | Study (year) | Predicted Outcome According to the Bispectral Index (BIS) Score | Observed Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Before surgery | Kerssens et al. (2003) (26) | With a BIS score of 60 to 70, there should be a response to a command most of the time. Patients with recall should demonstrate higher BIS values. |

No response was observed for 887 (82%) commands. The mean BIS value was 63.2 (SD, 4.9) Patients with and without recall had the same mean BIS values (67). |

| During intubation | Schneider et al. (2002) (33) | With a BIS score below 55, no patient should show an awareness reaction. Patients who have awareness reactions should have higher BIS scores compared with those who do not have awareness reactions. |

8 of 20 patients (40%) showed an awareness reaction after intubation. Those who responded and those who did not were clearly in different states of hypnosis, but the median BIS score was 52 for responders and 54 for nonresponders. This study shows that a BIS score between 50 and 60 before intubation does not guarantee that a patient will not experience awareness after intubation. Patients with and without awareness reactions had similar mean BIS values (71 and 69). |

| During surgery | Schneider et al. (2003) (29) | In unconscious patients, BIS scores should be less than 60. | The mean BIS score was 66 (SD, 17). The wide variation in BIS scores led to a wrong classification in some cases. |

| Yeo and Lo (2002) (35) | With a median BIS score of 70 at the time of skin incision, anesthesia should be light, and most of the patients should experience recall. | No patient experienced recall or awareness. | |

| McCann et al. (2002) (34) | During surgery and at the time of the intraoperative wake-up test, BIS scores should be less than 60. | The mean BIS score was 72 (SD, 8). |

SD indicates standard deviation.

Table 4 points to the limitations of BIS monitors that decrease its usefulness to guide anesthesia. In most of these studies, (26, 29, 34–35) BIS monitoring showed higher than expected values. In one study, (33) it showed lower than expected values. A consciousness monitor must have enough sensitivity to indicate reliably when a patient is awake or asleep. BIS monitors do not have adequate sensitivity to detect the state of being asleep. This could jeopardize a patient if the BIS-guided anesthesia leads to the administration of an extra dose of anesthetic agents.

Accuracy of Bispectral Index Monitoring

In a study on BIS monitoring, Schneider et al. (29) reported a sensitivity of 90.6% and a specificity of 26.3% for the detection of consciousness (proportion of those awake who were identified as awake). In another study, Sleigh et al. (37) reported a sensitivity of 61% and a specificity of 89% for the detection of unconsciousness (proportion of those asleep who were identified as asleep).

Additionally, Chen et al. (32) studied a small group of patients to compare the sensitivity and specificity of BIS monitors with the patient state index to differentiate unresponsive from responsive patients. Sensitivity was defined as fraction of unresponsive patients who were correctly identified to be unconscious and specificity was defined as fraction of responsive patients who were correctly identified as conscious. They plotted the sensitivity against 1-specificity to reflect the discriminatory power of BIS. The area under the ROC curve was 0.79 (SD, 0.04). (See Table 3.)

A diagnostic test with 100% accuracy would have an area of 1.0, and a test with an area of 0.5 shows that it performs no better than chance. Table 5 shows the reported sensitivity and specificity of BIS monitors in predicting conscious and unconscious states.

Table 5: Accuracy of Bispectral Index Monitors To Predict Consciousness and Unconsciousness.

| Study (year) Purpose |

Sensitivity % |

Specificity % |

PPV* % |

NPV* % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schneider et al. (2003) (29) For the detection of consciousness |

90.6 | 26.3 | 55.1 | 73.7 |

| Sleigh et al. (2001) (37) For the detection of unconsciousness |

61 | 98 | 97 | 75 |

PPV indicates positive predictive value; NPV, negative predictive value.

Schneider et al. (29) reported the prediction probabilities of BIS monitors with 4 different anesthetic techniques (Table 6).

Table 6: Prediction Probabilities of Bispectral Index Monitors With 4 Anesthetic Techniques (29).

| Prediction probability (Pk)) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Anesthetic Technique | Mean | SEM* |

| 1: Sevoflurane/low-dose remifentanil | 0.684 | 0.61 |

| 2: Sevoflurane/high-dose remifentanil | 0.668 | 0.061 |

| 3: Propofol/low-dose remifentanil | 0.743 | 0.056 |

| 4: Propofol/high-dose remifentanil | 0.721 | 0.057 |

| Combined | 0.685 | 0.029 |

SEM indicates standard error of the mean.

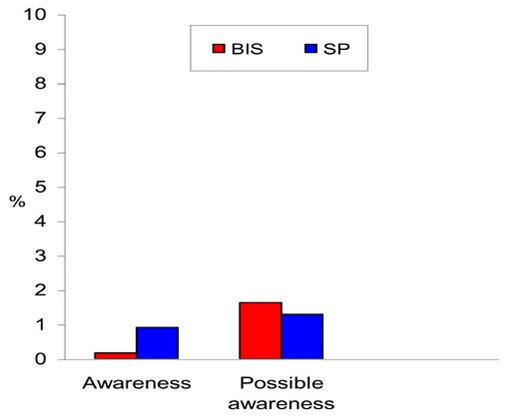

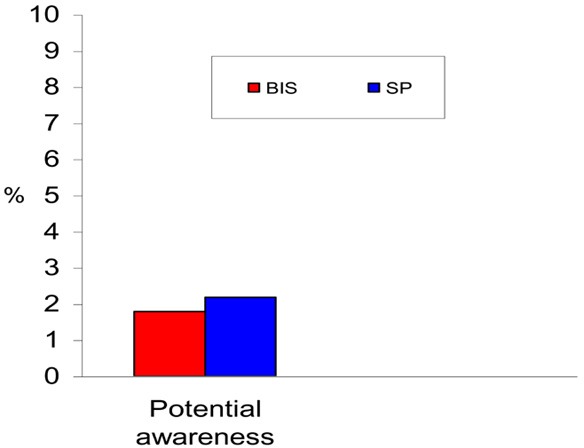

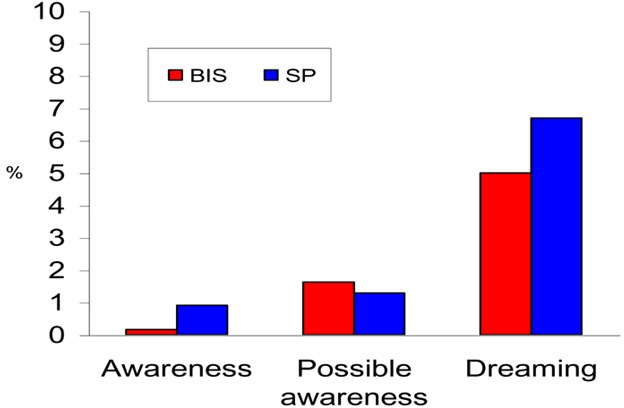

Figure 3 shows the reported data from Schneider’s study. This graph shows that BIS monitors are less able to predict the unconscious state correctly. The BIS monitors show values higher than 60 in those already asleep. Relying on these numbers, some patients would receive unnecessarily high drug doses, which would overshadow the benefit of reducing the incidence of intraoperative awareness. With the current evidence, it is not clear which population of patients or conditions show high BIS values while the patients are unconscious.

Figure 3: Individual Bispectral Index Values at Specific Events (29).

Group 1: Sevoflurane/remifentanil

Group 1: Sevoflurane/remifentanil

Group 2: Sevoflurane/remifentanil

Group 2: Sevoflurane/remifentanil

Group 3: Propofol/remifentanil

Group 3: Propofol/remifentanil

Effectiveness of Bispectral Index Monitors To Reduce Recovery Time

Ten RCTs and 1 prospective cohort study reported on the effectiveness of BIS monitoring to reduce the time to recovery. A summary of these studies is shown in Table 7.

Table 7: Summary of Findings From Studies Reporting on the Effectiveness of BIS Monitors To Reduce Recovery Time*.

| Study (year) |

Kreuer et al. (2003) (25) |

Ahmad et al. (2003) (39) |

Recart et al. (2003) (27) |

Puri and Murphy (2003) (28) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study type | RCT Group1: Narcotrend Group 2: BIS Group 3: SP |

RCT Group 1: BIS Group 2: SP |

RCT Group1: BIS Group 2: AEP Group 3: SP |

RCT Group 1: BIS Group 2: SP |

| Level of evidence | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Study population | Adult patients scheduled to have minor orthopedic surgery expected to last at least 1 hour | Patients undergoing gynecologic laparoscopy | Healthy patients undergoing laparoscopic general surgery | Patients undergoing valve replacement or coronary artery grafting under cardiopulmonary bypass |

| Number of patients | 120 (40 in each group; equal number of males and females) | 97 (49 BIS; 48 SP) | 90 | 30 adult patients undergoing valve replacement or coronary artery bypass grafting |

| Mean age, years (SD) | BIS: 43.8 (4.2) SP: 46.1 (4.5) |

BIS: 35.6 (8.7) SP: 35.4 (8.9) |

BIS: 47 (17) AEP: 42 (14) SP: 46 (15) |

BIS: 38.2 (14.0) SP: 32.1 (13.8) |

| Premedication | Yes | No | Yes | Midazolam and morphine |

| Anesthetic technique | Propofol and remifentanil | Sufentanil and sevoflurane | Propofol, fentanyl, and desflurane | Morphine, midazolam, thiopental, isoflurane, and nitrous oxide |

| Tracheal intubation | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| BIS values | Targeted BIS: 50 | Targeted BIS: 50–60 | BIS: Mean, 49 (SD, 13) SP: Mean, 40 (SD, 11) |

End of bypass: BIS: Mean, 49.7 (SD, 6) SP: Mean, 56.4 (SD, 25) |

| Recovery time | Time to eye opening, extubation, and arriving to PACU decreased significantly with the use of BIS (P <.001). In the SP group, recovery times were significantly shorter for women than for men (P = .003). In the BIS group, females and males had similar recovery times. |

The number of patients who successfully passed phase 1 recovery area was not different: BIS group: 42 (86%) SP group: 43 (90%) The mean length of stay (minutes) in the phase-2 recovery area before discharge did not differ between groups: BIS: 203 (SD, 78) SP: 200 (SD, 74) |

Extubation time was calculated as the number of minutes from stopping desflurane until the tracheal tube was removed. Extubation time: BIS: 6 (4) SP: 11 (10) (P<.05) PACU stay (minutes): BIS: 80 (47) SP: 108 (58) (P<.05) Following commands: no significant differences between groups Postoperative pain and request for analgesia: no differences between groups |

The time to recovery was defined as the time from turning off the anesthetic vaporizer to the time that a patient opened his/her eyes and obeyed a spoken command. There were no differences in the time to reach the recovery endpoint or the time to tracheal extubation between the 2 groups. |

Table 7: Summary of Findings From Studies Reporting on the Effectiveness of BIS Monitors To Reduce Recovery Time* (cont).

| Study (year) |

Basar et al. (2003) (40) |

Wong et al. (2002) (31) |

Bannister et al. (2001) (41) |

Pavlin et al. (2001) (42) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study type | RCT Group 1: BIS Group 2: SP |

RCT Group 1: BIS Group 2: SP |

RCT Group 1: BIS Group 2: SP |

RCT Over 7 months, primary caregivers were randomized to 1 of 2 groups: Group 1: BIS Group 2: Non-BIS Crossover was at 1-month intervals. |

| Level of evidence | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Study population | Patients undergoing open abdominal surgery | Elderly patients, all of whom were older than 60 years, undergoing elective orthopedic surgery | Pediatric patients undergoing inguinal hernia repair (0–3 years old) and tonsillectomy or adenoidectomy (3–18 years old) | Anesthesia providers were assigned on a monthly basis to a BIS or control group using a randomized crossover design. The final analysis had 236 men and 229 women. All of them received propofol and sevoflurane. |

Table 7: Summary of Findings From Studies Reporting on the Effectiveness of BIS Monitors To Reduce Recovery Time* (cont).

| Study (year) |

Basar et al. (2003) (40) | Wong et al. (2002) (31) | Bannister et al. (2001) (41) | Pavlin et al. (2001) (42) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of subjects | 60 (30 per group) | 60 | 202 | 18 certified registered nurses and 51 supervised residents-in-training Overall, 585 patients were studied (those scheduled for outpatient surgeries, excluding head and neck surgery). BIS monitors were installed in 18 operating rooms 3 months before the study to allow the anesthesia providers to become familiar with the devices. |

| Mean age, years (SD) | BIS: 42.1 (3.3) SP: 39 (4.5) |

BIS: 70 (6) SP: 71 (5) |

Range: 0–18 years | Men: BIS: 46 (18) Non-BIS: 52 (18) Women: BIS: 41 (13) Non-BIS: 41 (14) |

| Premedication | Diazepam & atropine | None | None for > 6 months | Not reported |

| Anesthetic technique | Thiopental, fentanyl, sevoflurane, and nitrous oxide | Isoflurane | Sevoflurane | Propofol and sevoflurane |

| Tracheal intubation | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Table 7: Summary of Findings From Studies Reporting on the Effectiveness of BIS Monitors To Reduce Recovery Time* (cont).

| Study (year) |

Basar et al. (2003) (40) |

Wong et al. (2002) (31) |

Bannister et al. (2001) (41) |

Pavlin et al. (2001) (42) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean BIS values (SD) | BIS: 44.9 (5.15) SP: 40.5 (4.53) |

BIS: 53 (4) SP: 47 (7) |

BIS, 0–6 months: 35.7 (9.6). BIS was unexpectedly problematic in titrating anesthetic in infants younger than 6 months. Despite the reductions in anesthetic dosage, BIS values remained below the minimum target of 40. Maintenance BIS in this age group was 35.7 (9.6), despite a significantly smaller than anticipated end-tidal sevoflurane concentration. BIS 6 months–3 years: 54.8 (9.1) BIS, 3–18 years: 47.2 (10.1) SP, 0–6 months: 36.2 (11.8) SP, 6 months–3 years: 50 (14.1) SP, 3–18 years: 39.6 (11.5) |

BIS: 47 |

Table 7: Summary of Findings From Studies Reporting on the Effectiveness of BIS Monitors To Reduce Recovery Time* (cont).

| Study (year) |

Basar et al. (2003) (40) | Wong et al. (2002) (31) | Bannister et al. (2001) (41) | Pavlin et al. (2001) (42) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recovery time | There were no significant differences between groups in the time to open eyes on command (P= .12) and the time to motor response after being given a command (P =.09). | There was a trend toward faster discharge from the PACU in the BIS group, but this did not reach statistical significance. The mean time to orientation was faster in the BIS group (9.5 [SD, 3] vs. 13.1 [SD, 4], (P<.001). | 0–6 months: Because of the difficulties associated with achieving target BIS values, early discontinuation of anesthetic agents was required; therefore, the measurements are not valid. 6 months– 3 years: No differences in recovery measures. 3–18 years: Patients in the BIS group were ready for discharge from the PACU significantly earlier than those in the SP group (P<.05). Time differences varied from 25% to 40%. | Total mean recovery duration, minutes (SD) Men: BIS: 147 (56) SP: 166 (73) (P<.035) Women: BIS: 166 (61) SP: 156 (59) (P =.24) Conclusion: Overall, there were no significant trends during the study for mean BIS values, mean end-tidal sevoflurane concentrations, or duration of recovery. The authors noted this suggests there were no significant changes in the management of patients over time within the institution. |

Table 7: Summary of Findings From Studies Reporting on the Effectiveness of BIS Monitors To Reduce Recovery Time* (cont).

| Study (year) |

Nelskyla et al. (2001) (43) |

Guignard et al. (2001) (44) |

Pavanti et al. (2001) (45) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Study type | RCT This study hypothesized that BIS-guided anesthesia lowers the incidence and severity of postoperative nausea and vomiting and improves the time to recovery and home readiness. |

Prospective and controlled non-RCT done in 2 phases as follows: Phase 1 had 41 patients (SP) Phase 2 had 39 patients (BIS-guided anesthesia) |

RCT In the BIS group, the anesthetics were given according to a BIS value rate of 40 to 60. In the SP group, the anesthetics were given based on the anesthesiologist’s decision |

| Level of evidence | 1 | 3 | 1 |

| Study population | Women scheduled for gynecologic laparoscopy (excluding tubal ligations) | Patients undergoing various surgical procedures (hernia repair, thyroidectomy, gynecological procedures, cholecystectomy, transurethral prostatectomy, colectomy, and venous stripping) | Patients undergoing abdominal surgery |

| Number of subjects | 62 (BIS, 32; SP, 30) | 80 | 90 (45 per group) |

| Mean age, years (SD) | BIS: 32 (6) SP: 32 (6) |

BIS: 55 (14) SP: 49 (14) |

Mean: ranged from 42 to 48 |

| Premedication | Glycopyrrolate | None | Diazepam |

| Anesthetic technique | Propofol, sevoflurane, and nitrous oxide | Sufentanil, isoflurane, and propofol | Remifentanil and sevoflurane |

| Tracheal intubation | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| BIS values | Median BIS during surgery: BIS: 54 (range, 49–61) SP: 55 (range, 30–65) |

BIS: Between 40 and 60 during surgery and 60-70 during the last 15 minutes before surgery ended | Range: 40–60 |

Table 7: Summary of Findings From Studies Reporting on the Effectiveness of BIS Monitors To Reduce Recovery Time* (cont).

| Study (year) |

Nelskyla et al. (2001) (43) |

Guignard et al. (2001) (44) |

Pavanti et al. (2001) (45) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recovery time | There were no differences between groups in time to extubation, opening of eyes, following orders, and home readiness. Time to orientation was shorter in the BIS group (6 minutes) than in the SP group (8 minutes; P< .05). The median BIS values during surgery were similar (BIS, 54; SP, 55).† |

The time in minutes from the end of surgery until awakening and tracheal extubation was not different between the 2 groups. Time to awakening: BIS: 8.5 (SD, 5) SP: 9.4 (6) Time to extubation: BIS: 9.2 (5.5) SP: 10.3 (6.3) |

In the BIS group the time from cessation of anesthetics to orientation decreased significantly. The time to extubation and eye opening was not different between the 2 groups. |

AEP indicates auditory evoked potential (awareness monitor); BIS, bispectral index; PACU, post anesthesia care unit; RCT, randomized controlled trial; SD, standard deviation; SP, standard practice.

This is an important consideration when interpreting the presented data.

Eleven studies, (25, 27–28, 31, 39–44) including 10 RCTs, (25, 27–28, 31, 39–42, 45) measured recovery time after anesthesia with and without BIS monitoring. Five RCTs reported no significant differences in recovery time between the BIS group and the SP group. (28, 31, 39-40, 43) Wong et al. (31) reported a significantly faster time to orientation in the BIS group compared with the SP group. However, in this study, the mean BIS score was lower in the SP group (SP, 47) than in the BIS group (BIS, 53). Nelskyla et al. (43) reported shorter orientation times for the BIS group, but the median BIS values during surgery were similar (BIS, 54; SP, 55).

Kruerer et al. (25) found that the time to eye opening, extubation, and arrival at the PACU decreased significantly with the use of BIS monitors. Pavanti et al. (45) reported that the time from cessation of anesthetics to orientation decreased significantly, but there were no differences between the BIS and SP groups for time to extubation or eye opening.

Another RCT (27) found only time to extubation and duration of PACU stay were significantly shorter in the BIS group. One RCT (42) showed that there was no difference in the incidence of phase-1 bypasses between the 2 groups. In this study, recovery time was similar for females, but was significantly shorter for males in the BIS group. The authors noted that overall there was no significant change in the management of patients over time. In 1 RCT of children, (41) recovery time was not different between BIS and SP groups for patients aged 6 months to 3 years, but it was significantly shorter in the BIS group for patients aged 3 to 18 years. Finally, 1 prospective cohort study (44) reported no difference in recovery time between the BIS and SP groups.

Bi-Aware Trial

The Bi-Aware trial (23) was a prospective, randomized, double-blinded, multicentre study that was designed to investigate if BIS-guided anesthesia reduces the incidence of intraoperative awareness. An estimate of sample size was based on an anticipated large reduction in the incidence of intraoperative awareness in the BIS group from 1% to 0.1%. Patients at high risk of intraoperative awareness were selected in order to increase the number of outcome events (i.e., awareness cases). The incidence of intraoperative awareness with BIS monitoring was presumed to be 0.04%, based on the data of reported incidence from the manufacturer.

Almost half (45%) of the patients in the study had high-risk cardiac surgery or off-pump coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Fifty two percent of all of the patients were transferred to the intensive care unit (BIS: n=639; SP: n= 633). The authors received unrestricted funding from the manufacturer. Table 8 on the next page shows a summary of the results of this trial.

Table 8: Summary of Results From the Bi-Aware Trial*.

| Study (year) |

Myles et al. (2004) (23) |

|---|---|

| Type of study | RCT (with an intention-to- treat analysis) |

| Level of evidence | 1 |

| Purpose and outcome measures | Purpose: To see if BIS-guided anesthesia reduces the incidence of intraoperative awareness Outcome measures: Awareness, recovery times, hypnotic drug administration, incidence of marked hypotension, anxiety and depression, patient satisfaction, major complications (myocardial infarction, stroke, acute renal failure, and sepsis), and 30-day mortality |

| Number of patients and type of surgery | 2,463 adult patients who had at least 1 of these risk factors for intraoperative awareness:

6 patients in the SP group received BIS monitoring mistakenly, and 14 patients randomized to the BIS group were not monitored. All of these patients were included in their allocated groups for all analyses; none had awareness. |

| Mean age, yrs (SD) | BIS: 58.1 (16.5) SP: 57.5 (16.9) |

| Female/male, n | BIS: 473/752; SP: 454/784 |

| Premedication, % | BIS: 55; SP: 57 |

| Anesthetic agent | Midazolam, propofol, and thiopentone (the technique was the same in the groups) |

| Tracheal intubation | Not reported |

| Muscle relaxant | Yes |

| Methods | For patients randomized to the SP group, the monitor was not turned on. For patients randomized to the BIS group, the delivery of anesthesia was adjusted to maintain a BIS score of 40–60 from the start of intubation to the time of wound closure. Postoperative interviews were scheduled 3 times: after recovery from general anesthesia (2–6 hours after surgery), 24–36 hours after surgery, and 30 days after surgery. All potential awareness episodes were coded independently by 3 experienced anesthetists who were members of the independent endpoint adjudication committee. Potential awareness cases were coded as awareness, possible awareness, or no awareness. Confirmed awareness was defined as a unanimous coding of awareness or 2 members coding as awareness and the third coding as possible awareness. Possible awareness was defined as 1 or more coding of awareness or possible awareness. |

| BIS values | The time-averaged BIS reading throughout the procedure was 44.5. |