Abstract

Saccharomonospora marina Liu et al. 2010 is a member of the genus Saccharomonospora, in the family Pseudonocardiaceae that is poorly characterized at the genome level thus far. Members of the genus Saccharomonospora are of interest because they originate from diverse habitats, such as leaf litter, manure, compost, surface of peat, moist, over-heated grain, and ocean sediment, where they might play a role in the primary degradation of plant material by attacking hemicellulose. Organisms belonging to the genus are usually Gram-positive staining, non-acid fast, and classify among the actinomycetes. Here we describe the features of this organism, together with the complete genome sequence (permanent draft status), and annotation. The 5,965,593 bp long chromosome with its 5,727 protein-coding and 57 RNA genes was sequenced as part of the DOE funded Community Sequencing Program (CSP) 2010 at the Joint Genome Institute (JGI).

Keywords: aerobic, chemoheterotrophic, Gram-positive, vegetative and aerial mycelia, spore-forming, non-motile, marine bacterium, Pseudonocardiaceae, CSP 2010

Introduction

Strain XMU15T (= DSM 45390 = KCTC 19701 = CCTCC AA 209048) is the type strain of the species Saccharomonospora marina [1], one of nine species currently in the genus Saccharomonospora [2]. The strain was originally isolated from an ocean sediment sample collected from Zhaoan Bay, East China Sea, in 2005 [1]. The genus name Saccharomonospora was derived from the Greek words for sakchâr, sugar, monos, single or solitary, and spore, a seed or spore, meaning the sugar (-containing) single-spored (organism) [3]; the species epithet was derived from the Latin adjective marina, of the sea, referring to the origin of the strain [1]. S. marina and the other type strains of the genus Saccharomonospora were selected for genome sequencing in one of the DOE Community Sequencing Projects (CSP 312) at Joint Genome Institute (JGI), because members of the genus (which originate from diverse habitats, such as leaf litter, manure, compost, surface of peat, moist, over-heated grain and ocean sediment) might play a role in the primary degradation of plant material by attacking hemicellulose. This expectation was underpinned by the results of the analysis of the genome of S. viridis [4], one of the recently sequenced GEBA genomes [5]. The S. viridis genome, the first sequenced genome from the genus Saccharomonospora, contained an unusually large number (24 in total) genes for glycosyl hydrolases (GH) belonging to 14 GH families, which were identified in the Carbon Active Enzyme Database [6]. Hydrolysis of cellulose and starch were also reported for other members of the genus (that are included in CSP 312), including S. marina [1], S. halophila [7], S. saliphila [8], S. paurometabolica [9], and S. xinjiangensis [10]. Here we present a summary classification and a set of features for S. marina XMU15T, together with the description of the genomic sequencing and annotation.

Classification and features

A representative genomic 16S rRNA sequence of S. marina XMU15T was compared using NCBI BLAST [11,12] under default settings (e.g., considering only the high-scoring segment pairs (HSPs) from the best 250 hits) with the most recent release of the Greengenes database [13] and the relative frequencies of taxa and keywords (reduced to their stem [14]) were determined, weighted by BLAST scores. The most frequently occurring genera were Gordonia (63.5%), Saccharomonospora (24.1%), Actinomycetospora (4.5%), Actinopolyspora (1.8%) and Pseudonocardia (1.4%) (195 hits in total). Regarding the single hit to sequences from members of the species, the average identity within HSPs was 99.7%, whereas the average coverage by HSPs was 100.1%. Regarding the 23 hits to sequences from other members of the genus, the average identity within HSPs was 96.1%, whereas the average coverage by HSPs was 98.3%. Among all other species, the one yielding the highest score was Saccharomonospora saliphila (HM368568), which corresponded to an identity of 99.9% and an HSP coverage of 92.1%. (Note that the Greengenes database uses the INSDC (= EMBL/NCBI/DDBJ) annotation, which is not an authoritative source for nomenclature or classification. For instance, the Gordonia hits are likely to be caused by mis-annotations in INSDC). The highest-scoring environmental sequence was FN667533 ('stages composting process pilot scale municipal drum compost clone PS3734'), which showed an identity of 96.0% and a HSP coverage of 97.9%. The most frequently occurring keywords within the labels of all environmental samples which yielded hits were 'skin' (6.3%), 'forearm' (2.8%), 'soil' (2.6%), 'fossa' (2.5%) and 'volar' (2.3%) (55 hits in total). These keywords do not fit to the known habitat of strain XMU15T, because Saccharomonospora rarely occurs in environmental samples so that more distant relatives (here from human skin) distort the automatically generated list of keywords. Environmental samples which yielded hits of a higher score than the highest scoring species were not found.

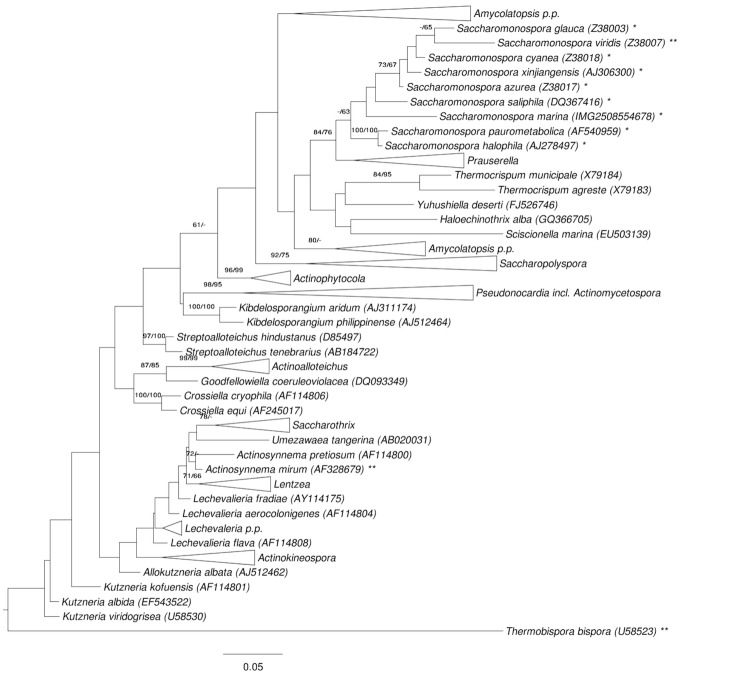

Figure 1 shows the phylogenetic neighborhood of S. marina in a 16S rRNA based tree. The sequences of the three 16S rRNA gene copies in the genome differ from each other by up to 13 nucleotides, and differ by up to 15 nucleotides from the previously published 16S rRNA sequence (FJ812357).

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic tree highlighting the position of S. marina relative to the type strains of the other species within the family Pseudonocardiaceae. The tree was inferred from 1,391 aligned characters [15,16] of the 16S rRNA gene sequence under the maximum likelihood (ML) criterion [17]. Rooting was done initially using the midpoint method [18] and then checked for its agreement with the current classification (Table 1). The branches are scaled in terms of the expected number of substitutions per site. Numbers adjacent to the branches are support values from 600 ML bootstrap replicates [19] (left) and from 1,000 maximum-parsimony bootstrap replicates [20] (right) if larger than 60%. Lineages with type strain genome sequencing projects registered in GOLD [21] are labeled with one asterisk, those also listed as 'Complete and Published' with two asterisks [4,22,23], with S. azurea missing second asterisk but published in this issue [24]. Actinopolyspora iraqiensis Ruan et al. 1994 [25] was ignored in the tree. The species was proposed to be a later heterotypic synonym of S. halophila [26], although the name A. iraqiensis would have had priority over S. halophila. This taxonomic problem will soon be resolved with regard to the genomes of A. iraqiensis and S. halophila, which were both part of CSP 312.

Table 1. Classification and general features of S. marina XMU15T according to the MIGS recommendations [27].

| MIGS ID | Property | Term | Evidence code |

|---|---|---|---|

| Current classification | Domain Bacteria | TAS [28] | |

| Phylum Actinobacteria | TAS [29] | ||

| Class Actinobacteria | TAS [30] | ||

| Subclass Actinobacteridae | TAS [30,31] | ||

| Order Actinomycetales | TAS [30-33] | ||

| Suborder Pseudonocardineae | TAS [30,31,34] | ||

| Family Pseudonocardiaceae | TAS [30,31,34-36] | ||

| Genus Saccharomonospora | TAS [32,37] | ||

| Species Saccharomonospora marina | TAS [1] | ||

| Type-strain XMU15 | TAS [1] | ||

| Gram stain | positive | TAS [1] | |

| Cell shape | variable, substrate and aerial mycelia | TAS [1] | |

| Motility | non-motile | TAS [1] | |

| Sporulation | smooth or wrinkled spores, singly, in pairs or in short chains from aerial mycelium | TAS [1] | |

| Temperature range | mesophile | TAS [1] | |

| Optimum temperature | 28-37°C | TAS [1] | |

| Salinity | optimum 0-3% (w/v) NaCl, tolerated up to 5% | TAS [1] | |

| MIGS-22 | Oxygen requirement | aerobic | TAS [1] |

| Carbon source | D-glucose, manose, melibiose, L-rhamnose, myo-inositol | TAS [1] | |

| Energy metabolism | chemoheterotrophic | NAS | |

| MIGS-6 | Habitat | marine, ocean sediment | TAS [1] |

| MIGS-15 | Biotic relationship | free living | TAS [1] |

| MIGS-14 | Pathogenicity | none | NAS |

| Biosafety level | 1 | NAS | |

| MIGS-23.1 | Isolation | ocean sediment | TAS [1] |

| MIGS-4 | Geographic location | Zhaoan Bay, East China Sea | TAS [1] |

| MIGS-5 | Sample collection time | December 2005 | NAS |

| MIGS-4.1 | Latitude | 24.108 | TAS [1] |

| MIGS-4.2 | Longitude | 117.294 | TAS [1] |

| MIGS-4.3 | Depth | 4 m | TAS [1] |

| MIGS-4.4 | Altitude | -4 m | TAS [1] |

Evidence codes - IDA: Inferred from Direct Assay (first time in publication); TAS: Traceable Author Statement (i.e., a direct report exists in the literature); NAS: Non-traceable Author Statement (i.e., not directly observed for the living, isolated sample, but based on a generally accepted property for the species, or anecdotal evidence). These evidence codes are from the Gene Ontology project. If the evidence code is IDA, then the property was directly observed for a living isolate by one of the authors or an expert mentioned in the acknowledgements [38].

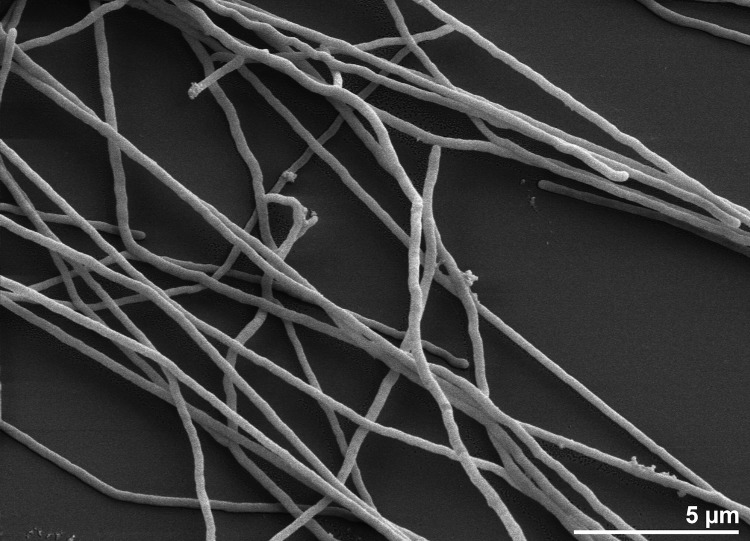

Cells of S. marina XMU15T are non-acid fast, stain Gram-positive and form an irregularly branched vegetative mycelium of 0.3 to 0.4 μm diameter (Figure 2) [1]. Non-motile, smooth or wrinkled spores were observed on the aerial mycelium, occasionally in short spore chains [1]. The growth range of strain XMU15T spans from 28-37°C, with an optimum at 28°C, and pH 7.0 on ISP 2 medium [1]. Strain XMU15T grows well in up to 5% NaCl, with an optimum at 0-3% NaCl [1]. Substrates used by the strain are summarized in the strain description [1].

Figure 2.

Scanning electron micrograph of S. marina XMU15T

Chemotaxonomy

The cell wall of strain XMU15T contains meso-diaminopimelic acid [1]; arabinose, galactose and ribose are present [1]. The fatty acids spectrum is dominated by penta- to heptadecanoic acids: iso-C16:0 (26.4%), C17:1 ω6c (16.8%), C16:0 (palmitic acid, 8.9%), C15:0 (16.2%), C17:1 ω8c (7.7%), iso-C16:1 H (6.0%) [1]. Main menaquinone is MK-9 H4 (90%) complemented by MK-8 H4 (10%) [1]; phospholipids comprised phosphatidylglycerol, diphosphatidylglycerol, and phosphatidylinisitol with a minor fraction of phosphatidylethanolamine [1].

Genome sequencing and annotation

Genome project history

This organism was selected for sequencing as part of the DOE Joint Genome Institute Community Sequencing Program (CSP) 2010, CSP 312, “Whole genome type strain sequences of the genus Saccharomonospora – a taxonomically troubled genus with bioenergetic potential”. The genome project is deposited in the Genomes On Line Database [21] and the complete genome sequence is deposited in GenBank. Sequencing, finishing and annotation were performed by the DOE Joint Genome Institute (JGI). A summary of the project information is shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Genome sequencing project information.

| MIGS ID | Property | Term |

|---|---|---|

| MIGS-31 | Finishing quality | Permanent draft |

| MIGS-28 | Libraries used | Three genomic libraries: one 454 pyrosequence standard library, one 454 PE library (10 kb insert size), one Illumina library |

| MIGS-29 | Sequencing platforms | Illumina GAii, 454 GS FLX Titanium |

| MIGS-31.2 | Sequencing coverage | 780.0 × Illumina; 8.6 × pyrosequence |

| MIGS-30 | Assemblers | Newbler version 2.3, Velvet version 1.0.13, phrap version SPS - 4.24 |

| MIGS-32 | Gene calling method | Prodigal |

| INSDC ID | CM001439 | |

| GenBank Date of Release | February 3, 2012 | |

| GOLD ID | Gi07581 | |

| NCBI project ID | 61991 | |

| Database: IMG | 2508501012 | |

| MIGS-13 | Source material identifier | DSM 45390 |

| Project relevance | Bioenergy and phylogenetic diversity |

Growth conditions and DNA isolation

The history of strain XMU15T starts in 2005 with an isolate from ocean sediment collected from Zhaoan Bay in the East China Sea, followed by a detailed chemotaxonomic description by Liu et al. [1], and deposit of the strain in three collections in 2009: Korean Collection for Type Cultures (accession 19701), Chinese Centre for Type Cultures Collections (accession 209048) and German Collection of Microorganisms and Cell cultures, DSMZ (accession 45390). Strain XMU15T, DSM 45390, was grown in DSMZ medium 83 (Czapek Peptone Medium) [39] at 28°C. DNA was isolated from 0.5-1 g of cell paste using Jetflex Genomic DNA Purification Kit (GENOMED 600100) following the standard protocol as recommended by the manufacturer with the following modifications: extended cell lysis time (60 min.) with additional 30µl achromopeptidase, lysostaphin, mutanolysin; proteinase K was added at 6-fold the supplier recommended amount for 60 min. at 58°C. The purity, quality and size of the bulk gDNA preparation were assessed by JGI according to DOE-JGI guidelines. DNA is available through the DNA Bank Network [40].

Genome sequencing and assembly

The genome was sequenced using a combination of Illumina and 454 sequencing platforms. All general aspects of library construction and sequencing can be found at the JGI website [41]. Pyrosequencing reads were assembled using the Newbler assembler (Roche). The initial Newbler assembly consisting of 185 contigs in one scaffold was converted into a phrap [42] assembly by making fake reads from the consensus, to collect the read pairs in the 454 paired end library. Illumina GAii sequencing data (5,096.2 Mb) was assembled with Velvet [43] and the consensus sequences were shredded into 1.5 kb overlapped fake reads and assembled together with the 454 data. The 454 draft assembly was based on 95.6 Mb 454 draft data and all of the 454 paired end data. Newbler parameters are -consed -a 50 -l 350 -g -m -ml 20. The Phred/Phrap/Consed software package [42] was used for sequence assembly and quality assessment in the subsequent finishing process. After the shotgun stage, reads were assembled with parallel phrap (High Performance Software, LLC). Possible mis-assemblies were corrected with gapResolution [41], Dupfinisher [44], or sequencing cloned bridging PCR fragments with subcloning. Gaps between contigs were closed by editing in Consed, by PCR and by Bubble PCR primer walks (J.-F. Chang, unpublished). A total of 233 additional reactions were necessary to close gaps and to raise the quality of the finished sequence. Illumina reads were also used to correct potential base errors and increase consensus quality using a software Polisher developed at JGI [45]. The error rate of the completed genome sequence is less than 1 in 100,000. Together, the combination of the Illumina and 454 sequencing platforms provided 788.6 x coverage of the genome. The final assembly contained 397,729 pyrosequence and 61,582,867 Illumina reads.

Genome annotation

Genes were identified using Prodigal [46] as part of the Oak Ridge National Laboratory genome annotation pipeline, followed by a round of manual curation using the JGI GenePRIMP pipeline [47]. The predicted CDSs were translated and used to search the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) non-redundant database, UniProt, TIGRFam, Pfam, PRIAM, KEGG, COG, and InterPro databases. These data sources were combined to assert a product description for each predicted protein. Non-coding genes and miscellaneous features were predicted using tRNAscan-SE [48], RNAMMer [49], Rfam [50], TMHMM [51], and signalP [52].

Genome properties

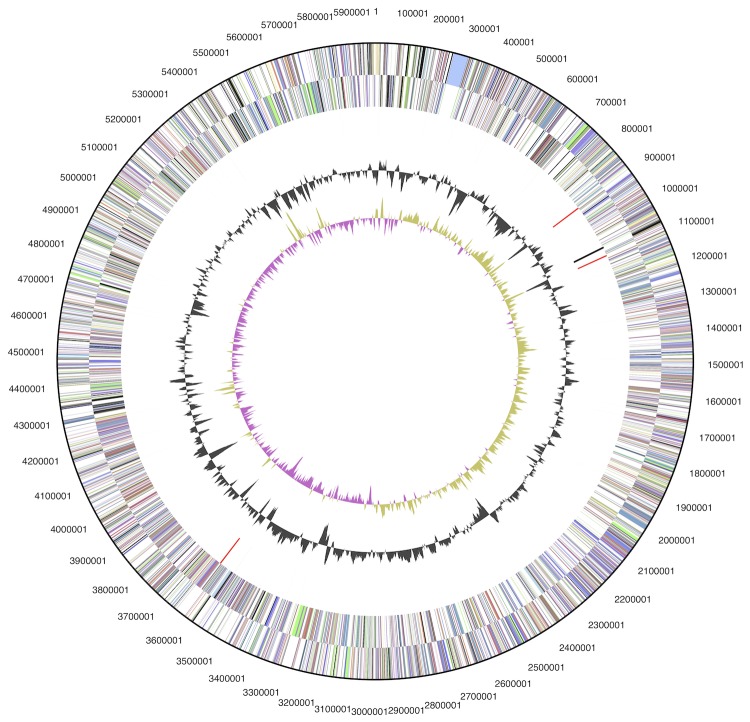

The genome consists of a 5,965,593 bp long circular chromosome with a 68.9% G+C content (Table 3 and Figure 3). Of the 5,784 genes predicted, 5,727 were protein-coding genes, and 57 RNAs; 149 pseudogenes were also identified. The majority of the protein-coding genes (75.0%) were assigned a putative function while the remaining ones were annotated as hypothetical proteins. The distribution of genes into COGs functional categories is presented in Table 4.

Table 3. Genome Statistics.

| Attribute | Value | % of Total |

|---|---|---|

| Genome size (bp) | 5,965,593 | 100.00% |

| DNA coding region (bp) | 5,364,872 | 89.93% |

| DNA G+C content (bp) | 4,112,466 | 68.94% |

| Number of replicons | 1 | |

| Extrachromosomal elements | 0 | |

| Total genes | 5,784 | 100.00% |

| RNA genes | 57 | 0.99% |

| rRNA operons | 3 | |

| tRNA genes | 47 | 0.81% |

| Protein-coding genes | 5,727 | 99.01% |

| Pseudo genes | 149 | 2.58% |

| Genes with function prediction (proteins) | 4,341 | 75.05% |

| Genes in paralog clusters | 3,491 | 60.36% |

| Genes assigned to COGs | 4,261 | 73.67% |

| Genes assigned Pfam domains | 4,426 | 76.52% |

| Genes with signal peptides | 1,159 | 20.04% |

| Genes with transmembrane helices | 1,256 | 21.72% |

| CRISPR repeats | 1 |

Figure 3.

Graphical map of the chromosome. From outside to the center: Genes on forward strand (color by COG categories), Genes on reverse strand (color by COG categories), RNA genes (tRNAs green, rRNAs red, other RNAs black), GC content, GC skew.

Table 4. Number of genes associated with the general COG functional categories.

| Code | value | %age | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| J | 173 | 3.6 | Translation, ribosomal structure and biogenesis |

| A | 3 | 0.1 | RNA processing and modification |

| K | 509 | 10.7 | Transcription |

| L | 226 | 4.7 | Replication, recombination and repair |

| B | 3 | 0.1 | Chromatin structure and dynamics |

| D | 40 | 0.8 | Cell cycle control, cell division, chromosome partitioning |

| Y | 0 | 0.0 | Nuclear structure |

| V | 68 | 1.4 | Defense mechanisms |

| T | 220 | 4.6 | Signal transduction mechanisms |

| M | 191 | 4.0 | Cell wall/membrane biogenesis |

| N | 6 | 0.1 | Cell motility |

| Z | 0 | 0.0 | Cytoskeleton |

| W | 0 | 0.0 | Extracellular structures |

| U | 52 | 1.1 | Intracellular trafficking and secretion, and vesicular transport |

| O | 152 | 3.2 | Posttranslational modification, protein turnover, chaperones |

| C | 369 | 7.7 | Energy production and conversion |

| G | 294 | 6.2 | Carbohydrate transport and metabolism |

| E | 381 | 8.0 | Amino acid transport and metabolism |

| F | 93 | 2.0 | Nucleotide transport and metabolism |

| H | 223 | 4.7 | Coenzyme transport and metabolism |

| I | 291 | 6.1 | Lipid transport and metabolism |

| P | 210 | 4.4 | Inorganic ion transport and metabolism |

| Q | 264 | 5.5 | Secondary metabolites biosynthesis, transport and catabolism |

| R | 649 | 13.6 | General function prediction only |

| S | 364 | 7.6 | Function unknown |

| - | 1,523 | 26.4 | Not in COGs |

Acknowledgements

The work conducted by the U.S. Department of Energy Joint Genome Institute was supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy under Contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231.

References

- 1.Liu Z, Li Y, Zheng LQ, Huang YJ, Li WJ. Saccharomonospora marina sp. nov., isolated from ocean sediment of the East China Sea. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2010; 60:1854-1857 10.1099/ijs.0.017038-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garrity G. NamesforLife. BrowserTool takes expertise out of the database and puts it right in the browser. Microbiol Today 2010; 37:9 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Euzéby JP. List of Bacterial Names with Standing in Nomenclature: a folder available on the internet. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1997; 47:590. 10.1099/00207713-47-2-590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pati A, Sikorski J, Nolan M, Lapidus A, Copeland A, Glavina Del Rio T, Lucas S, Chen F, Tice H, Pitluck S, et al. Complete genome sequence of Saccharomonospora viridis type strain (P101T). Stand Genomic Sci 2009; 1:141-149 10.4056/sigs.20263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wu D, Hugenholtz P, Mavromatis K, Pukall R, Dalin E, Ivanova NN, Kunin V, Goodwin L, Wu M, Tindall BJ, et al. A phylogeny-driven Genomic Encyclopaedia of Bacteria and Archaea. Nature 2009; 462:1056-1060 10.1038/nature08656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carbon Active Enzyme Database www.cazy.org

- 7.Al-Zarban SS, Al-Musallam AA, Abbas I, Stackebrandt E, Kroppenstedt RM. Saccharomonospora halophila sp. nov., a novel halophilic actinomycete isolated from marsh soil in Kuwait. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2002; 52:555-558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Syed DG, Tang SK, Cai M, Zhi XY, Agasar D, Lee JC, Kim CJ, Jiang CL, Xu LH, Li WJ. Saccharomonospora saliphila sp. nov., a halophilic actinomycete from an Indian soil. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2008; 58:570-573 10.1099/ijs.0.65449-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li WJ, Tang SK, Stackebrandt E, Kroppenstedt RM, Schumann P, Xu LH, Jiang CL. Saccharomonospora paurometabolica sp. nov., a moderately halophilic actinomycete isolated from soil in China. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2003; 53:1591-1594 10.1099/ijs.0.02633-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jin X, Xu LH, Mao PH, Hseu TH, Jiang CL. Description of Saccharomonospora xinjiangensis sp. nov. based on chemical and molecular classification. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1998; 48:1095-1099 10.1099/00207713-48-4-1095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Bascic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol 1990; 215:403-410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Korf I, Yandell M, Bedell J. BLAST, O'Reilly, Sebastopol, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 13.DeSantis TZ, Hugenholtz P, Larsen N, Rojas M, Brodie EL, Keller K, Huber T, Dalevi D, Hu P, Andersen GL. Greengenes, a chimera-checked 16S rRNA gene database and workbench compatible with ARB. Appl Environ Microbiol 2006; 72:5069-5072 10.1128/AEM.03006-05 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Porter MF. An algorithm for suffix stripping. Program: electronic library and information systems 1980; 14:130-137.

- 15.Lee C, Grasso C, Sharlow MF. Multiple sequence alignment using partial order graphs. Bioinformatics 2002; 18:452-464 10.1093/bioinformatics/18.3.452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Castresana J. Selection of conserved blocks from multiple alignments for their use in phylogenetic analysis. Mol Biol Evol 2000; 17:540-552 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stamatakis A, Hoover P, Rougemont J. A rapid bootstrap algorithm for the RAxML web servers. Syst Biol 2008; 57:758-771 10.1080/10635150802429642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hess PN, De Moraes Russo CA. An empirical test of the midpoint rooting method. Biol J Linn Soc Lond 2007; 92:669-674 10.1111/j.1095-8312.2007.00864.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pattengale ND, Alipour M, Bininda-Emonds ORP, Moret BME, Stamatakis A. How many bootstrap replicates are necessary? Lect Notes Comput Sci 2009; 5541:184-200 10.1007/978-3-642-02008-7_13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Swofford DL. PAUP*: Phylogenetic Analysis Using Parsimony (*and Other Methods), Version 4.0 b10. Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liolios K, Chen IM, Mavromatis K, Tavernarakis N, Kyrpides NC. The genomes on line database (GOLD) in 2009: Status of genomic and metagenomic projects and their associated metadata. Nucleic Acids Res 2010; 38:D346-D354 10.1093/nar/gkp848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Land M, Lapidus A, Mayilraj S, Chen R, Copeland A, Glavina Del Rio T, Nolan M, Lucas S, Tice H, Cheng JF, et al. Complete genome sequence of Actinosynnema mirum type strain (101T). Stand Genomic Sci 2009; 1:46-53 10.4056/sigs.21137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liolios K, Sikorski J, Jando M, Lapidus A, Copeland A, Glavina Del Rio T, Nolan M, Lucas S, Tice H, Cheng JF, et al. Complete genome sequence of Thermobispora bispora type strain (R51T). Stand Genomic Sci 2010; 2:318-326 10.4056/sigs.962171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Klenk HP, Held B, Lucas S, Lapidus A, Copeland A, Hammon N, Pitluck S, Goodwin LA, Han C, Tapia R, et al. Genome sequence of the soil bacterium Saccharomonospora azurea type strain (NA-128T). Stand Genomic Sci 2012; (this issue). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ruan SJ, Al-Tai AM, Zhou ZH, Qu LH. Actinopolyspora iraqiensis sp. nov., a new halophilic actinomycete isolated from soil. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1994; 44:759-763 10.1099/00207713-44-4-759 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tang SK, Wang Y, Klenk HP, Shi R, Lou K, Zhang YJ, Chen C, Ruan JS, Li WJ. Actinopolyspora alba sp. nov. and Actinopolyspora erythraea sp. nov., isolated from a salt field, and reclassification of Actinopolyspora iraqiensis Ruan et al. 1994 as a heterotypic synonym of Saccharomonospora halophila. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2011; 61:1693-1698 10.1099/ijs.0.022319-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Field D, Garrity G, Gray T, Morrison N, Selengut J, Sterk P, Tatusova T, Thomson N, Allen MJ, Angiuoli SV, et al. The minimum information about a genome sequence (MIGS) specification. Nat Biotechnol 2008; 26:541-547 10.1038/nbt1360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Woese CR, Kandler O, Wheelis ML. Towards a natural system of organisms. Proposal for the domains Archaea and Bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1990; 87:4576-4579 10.1073/pnas.87.12.4576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Garrity GM, Holt JG. The Road Map to the Manual. In: Garrity GM, Boone DR, Castenholz RW (eds), Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, Second Edition, Volume 1, Springer, New York, 2001, p. 119-169. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stackebrandt E, Rainey FA, Ward-Rainey NL. Proposal for a new hierarchic classification system, Actinobacteria classis nov. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1997; 47:479-491 10.1099/00207713-47-2-479 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhi XY, Li WJ, Stackebrandt E. An update of the structure and 16S rRNA gene sequence-based definition of higher ranks of the class Actinobacteria, with the proposal of two new suborders and four new families and emended descriptions of the existing higher taxa. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2009; 59:589-608 10.1099/ijs.0.65780-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Skerman VBD, McGowan V, Sneath PHA. Approved Lists of Bacterial Names. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1980; 30:225-420 10.1099/00207713-30-1-225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Buchanan RE. Studies in the nomenclature and classification of bacteria. II. The primary subdivisions of the Schizomycetes. J Bacteriol 1917; 2:155-164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Labeda DP, Goodfellow M, Chun J, Zhi X-Y, Li WJ. Reassessment of the systematics of the suborder Pseudonocardineae: transfer of the genera within the family Actinosynnemataceae Labeda and Kroppenstedt 2000 emend. Zhi et al. 2009 into an emended family Pseudonocardiaceae Embley et al. 1989 emend. Zhi et al. 2009. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2011; 61:1259-1264 10.1099/ijs.0.024984-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.List Editor Validation List no. 29. Validation of the publication of new names and new combinations previously effectively published outside the IJSB. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1989; 39:205-206 10.1099/00207713-39-2-205 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Embley MT, Smida J, Stackebrandt E. The phylogeny of mycolate-less wall chemotype IV Actinomycetes and description of Pseudonocardiaceae fam. nov. Syst Appl Microbiol 1988; 11:44-52 10.1016/S0723-2020(88)80047-X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nonomura H, Ohara Y. Distribution of actinomycetes in soil. X. New genus and species of monosporic actinomycetes in soil. J Ferment Technol 1971; 49:895-903 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, Botstein D, Butler H, Cherry JM, Davis AP, Dolinski K, Dwight SS, Eppig JT, et al. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Nat Genet 2000; 25:25-29 10.1038/75556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.List of growth media used at DSMZ. http://www.dsmz.de/catalogues/catalogue-microorganisms/culture-technology/list-of-media-for-microorganisms.html

- 40.Gemeinholzer B, Dröge G, Zetzsche H, Haszprunar G, Klenk HP, Güntsch A, Berendsohn WG, Wägele JW. The DNA Bank Network: the start from a German initiative. Biopreserv Biobank 2011; 9:51-55 10.1089/bio.2010.0029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.The DOE Joint Genome Institute www.jgi.doe.gov

- 42.Phrap and Phred for Windows. MacOS, Linux, and Unix. www.phrap.com

- 43.Zerbino DR, Birney E. Velvet: algorithms for de novo short read assembly using de Bruijn graphs. Genome Res 2008; 18:821-829 10.1101/gr.074492.107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Han C, Chain P. Finishing repeat regions automatically with Dupfinisher. In: Proceeding of the 2006 international conference on bioinformatics & computational biology. Arabnia HR, Valafar H (eds), CSREA Press. June 26-29, 2006: 141-146. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lapidus A, LaButti K, Foster B, Lowry S, Trong S, Goltsman E. POLISHER: An effective tool for using ultra short reads in microbial genome assembly and finishing. AGBT, Marco Island, FL, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hyatt D, Chen GL, Locascio PF, Land ML, Larimer FW, Hauser LJ. Prodigal Prokaryotic Dynamic Programming Genefinding Algorithm. BMC Bioinformatics 2010; 11:119. 10.1186/1471-2105-11-119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pati A, Ivanova N, Mikhailova N, Ovchinikova G, Hooper SD, Lykidis A, Kyrpides NC. GenePRIMP: A Gene Prediction Improvement Pipeline for microbial genomes. Nat Methods 2010; 7:455-457 10.1038/nmeth.1457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lowe TM, Eddy SR. tRNAscan-SE: a program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Res 1997; 25:955-964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lagesen K, Hallin PF, Rødland E, Stærfeldt HH, Rognes T, Ussery DW. RNammer: consistent annotation of rRNA genes in genomic sequences. Nucleic Acids Res 2007; 35:3100-3108 10.1093/nar/gkm160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Griffiths-Jones S, Bateman A, Marshall M, Khanna A, Eddy SR. Rfam: an RNA family database. Nucleic Acids Res 2003; 31:439-441 10.1093/nar/gkg006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Krogh A, Larsson B, von Heijne G, Sonnhammer ELL. Predicting transmembrane protein topology with a hidden Markov model: Application to complete genomes. J Mol Biol 2001; 305:567-580 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bendtsen JD, Nielsen H, von Heijne G, Brunak S. Improved prediction of signal peptides: SignalP 3.0. J Mol Biol 2004; 340:783-795 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.05.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]