Abstract

OBJECTIVE:

Despite national concerns over high rates of antipsychotic medication use among youth in foster care, concomitant antipsychotic use has not been examined. In this study, concomitant antipsychotic use among Medicaid-enrolled youth in foster care was compared with disabled or low-income Medicaid-enrolled youth.

PATIENTS AND METHODS:

The sample included 16 969 youths younger than 20 years who were continuously enrolled in a Mid-Atlantic state Medicaid program and had ≥1 claim with a psychiatric diagnosis and ≥1 antipsychotic claim in 2003. Antipsychotic treatment was characterized by days of any use and concomitant use with ≥2 overlapping antipsychotics for >30 days. Medicaid program categories were foster care, disabled (Supplemental Security Income), and Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF). Multicategory involvement for youths in foster care was classified as foster care/Supplemental Security Income, foster care/TANF, and foster care/adoption. We used multivariate analyses, adjusting for demographics, psychiatric comorbidities, and other psychotropic use, to assess associations between Medicaid program category and concomitant antipsychotic use.

RESULTS:

Average antipsychotic use ranged from 222 ± 110 days in foster care to only 135 ± 101 days in TANF (P < .001). Concomitant use for ≥180 days was 19% in foster care only and 24% in foster care/adoption compared with <15% in the other categories. Conduct disorder and antidepressant or mood-stabilizer use was associated with a higher likelihood of concomitant antipsychotic use (P < .0001).

CONCLUSIONS:

Additional study is needed to assess the clinical rationale, safety, and outcomes of concomitant antipsychotic use and to inform statewide policies for monitoring and oversight of antipsychotic use among youths in the foster care system.

Keywords: foster care, antipsychotic, children, psychotropic use

WHAT'S KNOWN ON THIS SUBJECT:

Youths in foster care have higher rates of psychotropic use, singly and concomitantly, than do youths who are eligible for Medicaid through income or disability qualifications. However, concomitant antipsychotic use among youth in foster care has not been assessed.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS:

Compared with youths who qualify for Medicaid because of a disability or low income, youths in foster care are more likely to receive antipsychotics concomitantly and for longer periods of time despite the lack of evidence to support such regimens.

High rates of psychotropic use among youths in foster care is a major national concern, which has led to intense scrutiny about its appropriateness in this vulnerable population. Psychotropic prevalence for youth in foster care ranges from 14% to 30% in community settings1–4 and as high as 67% in therapeutic foster care and 77% in group homes.5 Many youth in foster care receive more than 1 psychotropic medication, with as many as 22% using ≥2 medications from the same class.6 Among youths with autism who were in foster care, 21% received ≥3 medications from different classes concomitantly for at least 30 days, compared with 10% among youths with autism and eligible for Medicaid through a disability status.7 Finally, the increase has been primarily the second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs),8–14 which carry a greater risk of metabolic adverse effects among children.15 Concerning is the expanded use of antipsychotics for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in the absence of schizophrenia, autism, or bipolar disorder for which these medications are typically prescribed.16

In light of this evidence, the question raised here is whether antipsychotics are prescribed concomitantly for youth in foster care. Antipsychotic polypharmacy has increased among adults,17–19 so it possible this is also occurring in youths. Given the lack of scientific evidence for such practice, the lack of data on the cumulative risks on child development, and the clear indications of the metabolic adverse effects with these agents, it is important to investigate concomitant antipsychotic use in this vulnerable child population. The purpose of this study was to examine concomitant antipsychotic treatment among youth in foster care compared with youth who met Medicaid eligibility for psychological, physical, and developmental impairment or financial need (ie, groups with distinctly different mental health needs). This information can aid state agencies in better understanding the challenges in delivering effective mental health care to youth placed in foster care, who typically have greater psychological impairment than youth in other Medicaid program categories. The university institutional review boards at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, the University of Pennsylvania, and the University of Maryland, Baltimore, approved this study and granted a waiver of informed consent.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Design and Sample Selection

Medicaid fee-for-service and managed care claims data from 1 Mid-Atlantic state were used for a cross-sectional study of antipsychotic use in 2003. The 637 924 continuously Medicaid-enrolled youths who were younger than 20 in 2003 constituted the population from which the study sample was selected. Continuous enrollment was defined as ≥335 of 365 days of Medicaid eligibility. The study sample was youth with (1) an inpatient or outpatient visit associated with a mental health diagnosis, and (2) a pharmacy claim for an antipsychotic medication in 2003. The criterion of at least 2 service or treatment encounters is an accurate method for identifying individuals engaged in mental health care using administrative data.20–22

Data Sources

A unique identifier not traceable to personal identifiers or Medicaid number allowed data linkage across 3 separate Medicaid data files: enrollment; medical services; and pharmacy. Enrollment files identified eligibility dates, age, gender, race, and Medicaid program category (ie, foster care, disabled). Plan type was coded as fee-for-service versus managed care. International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, psychiatric diagnostic codes obtained from health and behavioral health outpatient and inpatient claims were classified as ADHD, anxiety, autism, bipolar, conduct disorder, depression, oppositional defiant disorder, psychoses, schizophrenia, and substance abuse. Pharmacy claims for psychotropic medications were classified by major therapeutic class. The study targeted stimulants, antidepressants, antipsychotics, and mood-stabilizers. Mood-stabilizing agents used in psychiatry included select anticonvulsants (carbamazepine, valproic acid, gabapentin, lamotrigine, and oxcarbazepine) and lithium.

Medicaid Program Categories

Medicaid program categories defined youth who were eligible because of an existing disability (ie, Supplemental Security Income [SSI]), involvement in foster care or adoption services, or Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF). Youth in foster care may be adopted or removed/reunited with families, and thus they transition between foster care, adoption, or TANF. Moreover, those who remain longer in foster care are more likely to use mental health services23 and might be characteristically different from youths who are adopted or are reunited with their family. Medicaid program category status, therefore, might denote characteristic differences that could potentially influence antipsychotic use. To assess this, multicategory involvement of youth in foster care was grouped as foster care only, foster care/SSI, foster care/TANF, or foster care/adoption.

Binary Measures of Antipsychotic Use

Antipsychotic use during the study year was defined as binary measures of any and concomitant use. First, youths who had at least 1 claim for an antipsychotic medication during the year were coded as any use. Youths with ≥2 different antipsychotic medications during the year were classified as nonoverlapping and overlapping days of use. Concomitant use was defined as overlap of ≥2 antipsychotics for >30 days. The goal was to capture concomitant use that did not reflect cross tapering.

Continuous Measure of Antipsychotic Use

A previously used method24 was employed to establish the duration of concomitant antipsychotic use. First, days of use for each antipsychotic medication separately (ie, risperidone, quetiapine, etc) were estimated by using 2 key variables on each pharmacy claim: (1) medication-dispensing date and (2) the days of medication supplied. Days of use were organized into continuous treatment episodes for each antipsychotic medication. Continuous episodes were defined as consecutive medication claims with no more than 14 days between the end of 1 medication (ie, date dispensed + days supply) and the start of a new medication (ie, date dispensed of the next prescription).

Next, concomitant antipsychotic treatment episode days were identified when ≥2 antipsychotics were used on the same day and this occurred for >30 days. Total duration of overlap was established as well as the unique days of any antipsychotic use (ie, not double-counting days of overlap).

Statistical Analyses

We used χ2 and 1-way analysis of variance for bivariate comparisons across Medicaid program category in terms of age, gender, race, plan type (ie, fee-for-service or managed care), psychiatric diagnoses, and use of antidepressants, mood stabilizers, and stimulants. Logistic regression was used to examine the likelihood of receiving antipsychotics concomitantly as a function of Medicaid program categories. The analysis controlled for psychiatric diagnoses and other psychotropic medication use as well as age, gender, race, plan type (fee-for-service or managed care), and duration of antipsychotic treatment. Data were analyzed by using SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute, Inc, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Characteristics of the Youth Sample

Of the 637 924 youth continuously enrolled in Medicaid, 16 969 (2.7%) had a health or behavioral health visit associated with a psychiatric diagnosis and received an antipsychotic medication in 2003. Of those continuously enrolled, the sample reflects 8.4% of 18 906 in foster care only, 25.8% of 2860 in foster care/SSI, 4.9% of 10 685 in foster care/TANF, 5.1% of 12 622 in foster care/adoption, 9.7% of 78 789 in SSI, and 0.5% of 514 062 in TANF. The distribution of youth in TANF, SSI, and foster care who used mental health services is similar to other state Medicaid programs.1,25

Overall, the sample was 70% male (n = 11 842), 67% white (n = 11 424), 21% black (n = 3522), 19% aged 5 to 9 years, 44% aged 10 to 14 years, and 36% aged 15 to 19 years. Medicaid program category was distributed as follows: 52% (n = 8787) SSI; 21% (n = 3631) TANF; 14% (n = 2310) foster care only; 5% (n = 833) foster care/SSI; 4% (n = 735) foster care/TANF; and 4% (n = 673) foster care/adoption. Most (63%) were in managed care compared with 34% in fee-for-service.

Medicaid program category characteristics differed significantly (Table 1). The largest proportion of males was in foster care only, foster care/SSI, foster care/adoption, and SSI. Older adolescents were predominantly in the foster care groups, children aged 5 to 14 years were mainly in foster care/adoption, SSI, and TANF; and preschool age children were mainly in TANF. Black youths comprised 21% overall who received antipsychotic medication and 37% of the foster care-only group. White youths comprised 67% of all antipsychotic users but 71% of the SSI antipsychotic-users. The majority of children across all program categories were in managed care, but there were significantly higher proportions of youth in TANF and SSI who received managed care relative to the foster care categories (P < .0001).

TABLE 1.

Demographic Characteristics, Psychiatric Diagnoses, and Psychotropic Medications According to Medicaid Program Status Category for the 16 969 Continuously Enrolled Youths Who Received Antipsychotic Medication in 2003

| Foster Care Only (N = 2310) |

Foster Care and SSI (N = 833) |

Foster Care and TANF (N = 735) |

Foster Care and Adoption (N = 673) |

SSI (N = 8787) |

TANF (N = 3631) |

TOTAL (N = 16 969) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Gendera | ||||||||||||||

| Female | 800 | 34.6 | 262 | 31.5 | 309 | 42.0 | 207 | 30.8 | 2236 | 25.5 | 1313 | 36.2 | 5127 | 30.2 |

| Male | 1510 | 65.4 | 571 | 68.6 | 426 | 57.9 | 466 | 69.2 | 6551 | 74.6 | 2318 | 63.8 | 11 842 | 69.8 |

| Racea | ||||||||||||||

| White | 1246 | 53.9 | 579 | 69.5 | 486 | 66.1 | 398 | 59.1 | 6238 | 70.9 | 2477 | 68.2 | 11 424 | 67.3 |

| Black | 864 | 37.4 | 196 | 23.5 | 194 | 26.4 | 222 | 32.9 | 1479 | 16.8 | 567 | 15.6 | 3522 | 20.8 |

| Hispanic | 123 | 5.3 | 1 | 0.12 | 1 | 0.14 | 30 | 4.5 | 308 | 3.5 | 145 | 3.9 | 608 | 3.6 |

| Other | 77 | 3.3 | 57 | 6.8 | 54 | 7.4 | 23 | 3.4 | 762 | 8.8 | 442 | 12.2 | 1415 | 8.3 |

| Age groupa | ||||||||||||||

| <5 y | 6 | 0.26 | 2 | 0.24 | 3 | 0.41 | 1 | 0.15 | 51 | 0.58 | 45 | 1.2 | 108 | 0.64 |

| 5–9 y | 270 | 11.7 | 61 | 7.3 | 79 | 10.8 | 157 | 23.3 | 1750 | 19.9 | 1005 | 27.7 | 3322 | 19.6 |

| 10–14 y | 895 | 38.7 | 301 | 36.1 | 228 | 31.0 | 345 | 51.3 | 4061 | 46.2 | 1622 | 44.7 | 7452 | 43.9 |

| 15–19 y | 1139 | 49.3 | 469 | 56.3 | 425 | 57.8 | 170 | 25.3 | 2925 | 33.3 | 959 | 26.4 | 6087 | 35.9 |

| Plan typea | ||||||||||||||

| Managed care | 1188 | 51.4 | 411 | 49.3 | 332 | 45.2 | 422 | 62.7 | 6031 | 68.6 | 2377 | 65.5 | 10 761 | 63.4 |

| Fee-for-service | 911 | 39.5 | 332 | 39.9 | 327 | 44.5 | 239 | 35.5 | 2660 | 30.3 | 1227 | 33.8 | 5696 | 33.6 |

| Both | 211 | 9.1 | 90 | 10.8 | 76 | 10.3 | 12 | 1.8 | 96 | 1.1 | 27 | 0.7 | 512 | 3.0 |

| Psychiatric diagnoses | ||||||||||||||

| ADHDa | 1075 | 46.5 | 436 | 52.3 | 265 | 36.1 | 446 | 66.3 | 4925 | 56.1 | 1898 | 52.3 | 9045 | 53.3 |

| Anxietya | 411 | 17.8 | 121 | 14.5 | 128 | 17.4 | 97 | 14.4 | 968 | 11.0 | 470 | 12.9 | 2195 | 12.9 |

| Conduct disordera | 819 | 35.5 | 350 | 42.0 | 261 | 35.5 | 191 | 28.4 | 2058 | 23.4 | 785 | 21.6 | 4464 | 26.3 |

| Depressiona | 855 | 37.0 | 391 | 46.9 | 372 | 50.6 | 174 | 25.9 | 2557 | 29.1 | 1385 | 38.1 | 5734 | 33.8 |

| Oppositional defiant disordera | 694 | 30.0 | 317 | 38.1 | 260 | 35.4 | 159 | 23.6 | 2224 | 25.3 | 889 | 24.5 | 4543 | 26.8 |

| Substance abusea | 190 | 8.2 | 98 | 11.8 | 129 | 17.6 | 13 | 1.9 | 271 | 3.1 | 153 | 4.2 | 854 | 5.0 |

| Bipolar disordera | 469 | 20.3 | 275 | 33.0 | 171 | 23.3 | 120 | 17.8 | 1949 | 22.2 | 550 | 15.2 | 3534 | 20.8 |

| Psychosesa | 366 | 15.8 | 147 | 17.7 | 130 | 17.7 | 75 | 11.1 | 1309 | 14.9 | 479 | 13.2 | 2506 | 14.8 |

| Schizophreniaa | 161 | 6.9 | 52 | 6.2 | 41 | 5.6 | 34 | 5.1 | 454 | 5.2 | 134 | 3.7 | 876 | 5.2 |

| Autisma | 36 | 1.6 | 7 | 0.84 | 2 | 0.27 | 28 | 4.2 | 803 | 9.1 | 33 | 0.91 | 909 | 5.4 |

| Psychotropic classes | ||||||||||||||

| SGA | 2256 | 97.7 | 820 | 98.4 | 719 | 97.8 | 665 | 98.8 | 8650 | 98.4 | 3604 | 99.3 | 16 714 | 98.5 |

| Antidepressanta | 1377 | 59.6 | 529 | 63.5 | 501 | 68.2 | 379 | 56.3 | 4719 | 53.7 | 1946 | 53.6 | 9451 | 55.7 |

| Mood stabilizera | 986 | 42.7 | 431 | 51.7 | 260 | 35.4 | 264 | 39.2 | 3577 | 40.7 | 873 | 24.0 | 6391 | 37.7 |

| Stimulanta | 1142 | 49.4 | 429 | 51.5 | 286 | 38.9 | 477 | 70.9 | 5085 | 57.9 | 1992 | 54.9 | 9411 | 55.5 |

| Antipsychotic use | ||||||||||||||

| Single useb | 1819 | 79 | 637 | 76 | 597 | 81 | 554 | 82 | 7062 | 80 | 3152 | 87 | 13 821 | 81 |

| Multiple usec,d | 491 | 21 | 196 | 24 | 138 | 19 | 119 | 18 | 1725 | 20 | 479 | 13 | 3148 | 19 |

| Nonconcomitant | 247 | 50.3 | 118 | 60.2 | 88 | 63.8 | 73 | 61.3 | 1129 | 65.4 | 388 | 81.0 | 2043 | 64.9 |

| Concomitant | 244 | 49.7 | 78 | 39.8 | 50 | 36.2 | 46 | 13.4 | 596 | 34.6 | 91 | 19.0 | 1105 | 35.1 |

| Concomitant dayse,f | ||||||||||||||

| 31–89 d | 151 | 61.9 | 62 | 79.5 | 38 | 76.0 | 30 | 65.2 | 395 | 66.3 | 67 | 73.6 | 743 | 67.2 |

| 90–179 d | 47 | 19.3 | 9 | 11.5 | 8 | 16.0 | 5 | 10.9 | 120 | 20.1 | 14 | 15.4 | 203 | 18.4 |

| ≥180 d | 46 | 18.8 | 7 | 9.0 | 4 | 8.0 | 11 | 23.9 | 81 | 13.6 | 10 | 11.0 | 159 | 14.4 |

SGA percentages do not equal 100% because 1% to 2% received a first-generation antipsychotic.

P < .0001.

Single versus multiple use; P < .0001.

Concomitant versus not concomitant/single use; P < .0001.

The percentage is based on the number of all multiple antipsychotic medication users.

P < .05.

The percentage is based on the number of youths with concomitant use.

Psychiatric diagnoses also differed significantly across the Medicaid program categories (P < .0001; Table 1). The most common diagnoses among the 16 969 youth who used antipsychotic medication were ADHD (53%) and depression (34%). Overall, 21% of youth had a bipolar disorder diagnosis; this ranged from 33% of youths in foster care/SSI to 15% of youths in TANF. On average, 5% of the antipsychotic-treated youth had a visit associated with a diagnosis of schizophrenia.

Antipsychotic use (16 714 of 16 969 [99%]) was almost exclusively a second-generation antipsychotic. The majority (56%) also received an antidepressant, which exceeded 60% in the foster care groups. Although 56% of the 16 969 youths received a stimulant medication, this was 71% in foster care/adoption. Just about one-third was taking a mood-stabilizer, ranging from 52% in foster care/SSI to 24% in TANF.

Concomitant Antipsychotic Treatment

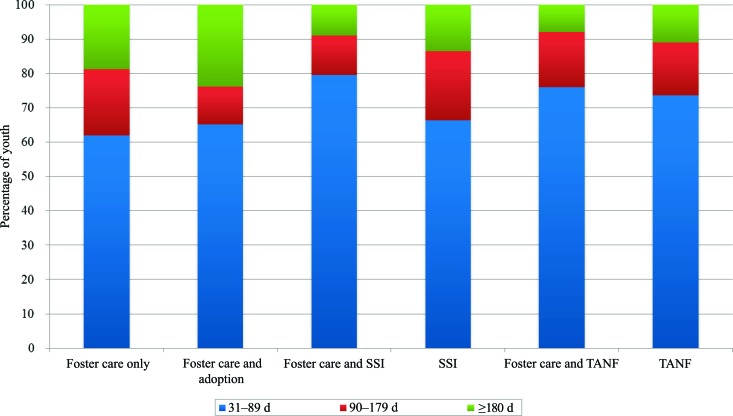

Duration of concomitant antipsychotic use differed significantly across Medicaid program categories (Table 1; Fig 1; P < .0001). More than one-third in foster care only (93 of 244 [38%]), foster care/adoption (16 of 46 [35%]), and SSI (201 of 596 [34%]) received antipsychotics concomitantly for ≥90 days compared with 21% in foster care/SSI (16 of 78), 24% in foster care/TANF (12 of 50), and 26% in TANF (24 of 91). In a bivariate analysis, plan type was associated with any concomitant use, but it was not associated with duration of concomitant use. The interaction between plan type and Medicaid program category was not significant.

FIGURE 1.

Duration of concomitant antipsychotic use according to Medicaid program for 1105 youths.

The average days of antipsychotic use differed significantly across Medicaid program categories of youth with any antipsychotic use (n = 16 969) and the subsample of 1105 who used antipsychotics concomitantly (P < .0001; Table 2). The duration of antipsychotic use was ∼60 days longer for the 1105 who received antipsychotics concomitantly compared with the 16 969 who received any antipsychotic. The longest duration was among concomitant users in foster care only (277.5 ± 89 days), which was 80 days longer than in TANF (P < .0001).

TABLE 2.

Total Days of Antipsychotic Medication Use According to Medicaid Program and Subgroups of Youth With Any and Concomitant Use

| Youth Subgroups | n | Foster Care Only, Mean (SD) | Foster Care and SSI, Mean (SD) | Foster Care and TANF, Mean (SD) | Foster Care and Adoption, Mean (SD) | SSI, Mean (SD) | TANF, Mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any antipsychotic usea | 16 969 | 222.3 (110) | 185.7 (111) | 147.2 (103) | 208.9 (110) | 190.3 (108) | 134.9 (101) |

| Concomitant antipsychotic usea | 1105 | 277.5 (89) | 252.5 (87) | 213.9 (92) | 275.9 (79) | 258.3 (89) | 197.4 (94) |

| Concomitant antipsychotic user with other psychotropic classes | 1105 | ||||||

| With antidepressant | 756 | 277.1 (87) | 253.1 (88) | 218.3 (94) | 279.8 (81) | 262.9 (87) | 209.0 (90) |

| Without antidepressant | 349 | 278.5 (95) | 250.8 (85) | 198.5 (90) | 267.2 (78) | 249.2 (93) | 172.6 (97) |

| With mood stabilizer | 734 | 285.5 (89) | 262.9 (89) | 228.5 (96) | 292.2 (70) | 266.7 (86) | 212.9 (92) |

| Without mood stabilizer | 371 | 261.4 (88) | 231.6 (81) | 198.1 (88) | 238.9 (90) | 239.8 (94) | 175.7 (93) |

| With stimulant | 485 | 304.1 (72) | 263.9 (79) | 252.3 (79) | 287.9 (68) | 267.7 (84) | 211.9 (86) |

| Without stimulant | 620 | 261.7 (94) | 244.9 (92) | 197.5 (94) | 260.4 (92) | 250.2 (92) | 181.9 (99) |

P < .0001.

The odds of receiving antipsychotics concomitantly for the 16 969 youth who received antipsychotic medication in 2003 are displayed in Table 3. Concomitant use was less likely for white versus black youths (odds ratio [OR]: 0.73 [95% confidence interval (CI): 0.61–0.87]), 5–9 years old versus 15-19-year-old youth (OR: 0.72 [95% CI: 0.57–0.91]), and youth in TANF versus SSI (OR: 0.58 [95% CI: 0.46–0.74]). Controlling for other variables in the model, the likelihood of receiving antipsychotics concomitantly was no different between the foster care groups and SSI. Diagnoses of autism, bipolar, conduct disorder, psychoses, and schizophrenia and psychotropic treatment with antidepressants and mood stabilizers were significantly associated with concomitant antipsychotic use.

TABLE 3.

Factors Associated With the Odds of Concomitant Antipsychotic Treatment Among 16 969 Youths Who Received Antipsychotic Medication in 2003

| OR | 95% CI | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics | |||

| Male | 0.93 | 0.81–1.08 | .3616 |

| Female (reference) | |||

| White | 0.73 | 0.61–0.87 | .0004 |

| Other race | 1.09 | 0.86–1.39 | .4873 |

| Black (reference) | |||

| <5 y | — | — | .9591 |

| 5–9 y | 0.72 | 0.57–0.91 | .0058 |

| 10–14 y | 0.88 | 0.76–1.03 | .1031 |

| 15–19 y (reference) | |||

| Fee-for-service | 0.98 | 0.85–1.14 | .8019 |

| Managed care (reference) | |||

| Medicaid program group | |||

| Foster care | 1.18 | 0.99–1.40 | .0687 |

| Foster care/adopt | 0.95 | 0.69–1.33 | .7802 |

| Foster care/SSI | 1.12 | 0.86–1.46 | .4062 |

| Foster care/TANF | 1.12 | 0.81–1.55 | .4791 |

| TANF | 0.58 | 0.46–0.74 | <.0001 |

| SSI (reference) | |||

| Psychiatric diagnoses | |||

| ADHD | 0.97 | 0.83–1.13 | .6600 |

| Anxiety | 1.11 | 0.93–1.33 | .2405 |

| Autism | 1.52 | 1.16–2.00 | .0028 |

| Bipolar | 1.26 | 1.10–1.49 | .0013 |

| Conduct disorder | 1.43 | 1.26–1.66 | <.0001 |

| Depression | 0.99 | 0.87–1.16 | .9687 |

| Oppositional defiant disorder | 1.01 | 0.87–1.17 | .8867 |

| Psychoses | 1.98 | 1.65–2.37 | <.0001 |

| Schizophrenia | 1.86 | 1.46–2.35 | <.0001 |

| Substance abuse | 1.03 | 0.80–1.35 | .7734 |

| Psychotropic medication | |||

| Antidepressant | 1.41 | 1.22–1.63 | <.0001 |

| Mood stabilizer | 2.05 | 1.77–2.38 | <.0001 |

| Stimulant | 0.85 | 0.73–0.99 | .0346 |

| Duration of antipsychotic use | 1.006 | 1.005–1.007 | <.0001 |

DISCUSSION

This is the first study, to our knowledge, that examined concomitant antipsychotic use among subgroups of youth in foster care. After controlling for psychiatric diagnoses, other psychotropic use and demographic factors, youth who entered foster care were as likely to receive antipsychotics concomitantly for over 30 days as were disabled youth who typically have conditions for which antipsychotics are indicated. Antipsychotics have been used concomitantly for adults with schizophrenia,26 but the rare prevalence among youths is not an explanation for the observed patterns. The data reveal that youths receive antipsychotics concomitantly primarily for conduct disorders. Of note, white youth were 27% less likely to receive concomitant antipsychotic treatment compared with black youths. Although the use patterns in the present study are concerning, better data on the clinical rationale, treatment outcomes, and safety are needed to assess the appropriateness and therapeutic benefit of such regimens.

There might be a number of clinical decisions for using antipsychotics concomitantly that are not captured in administrative data. For one, youths whose symptoms persist might require a higher dose. However, if unable to tolerate the adverse effects at the higher dose, a second agent with a different adverse effect profile might be prescribed to achieve a therapeutic effect and minimize the adverse effect burden. Second, concomitant use might have been for treatment of sleep problems, which would not have been detected in the claims data. Finally, a proportion might lack a reasonable clinical rationale. Unfortunately, it was not possible to determine which proportion of the prescribing is this latter group.

Nonetheless, concomitant antipsychotic use is not empirically supported. The evidence that does exist has been limited mainly to clozapine augmentation in treatment resistant patients.27 Antipsychotic polypharmacy typically has demonstrated greater adverse effects with only marginal benefits.27 The long-term use of concomitant antipsychotic medication carries important policy and practice implications given that approximately one-half of youth who enter the child welfare system have some emotional or behavioral problem,28 but only 55% receive mental health services that align with national standards.29

The mounting evidence of the increased risk associated with these agents has heightened public concern about antipsychotic prescribing in pediatrics, and specifically adverse metabolic effects15,30–33 and the adequacy of monitoring and oversight.34 Correll et al31 compared antipsychotic dose in a pediatric sample of new SGA users on changes in weight and metabolic parameters. Dose was not significantly associated with weight gain, but olanzapine (>10 mg per day) and risperidone (>1.5 mg per day) were significantly related to increases in total cholesterol.31 However, risperidone was the only SGA with a sufficient sample size to produce robust dose effect findings. There are no data on interactions, but given different receptor profiles it is a possibility, and the cP450 enzyme might have an important role. The incidence of weight gain, type 2 diabetes, and dyslipidemia among children and adolescents has been reported to be 2.3 to 5.3 times greater among those who receive multiple antipsychotics.15 It is without question, given this evidence, that routine monitoring should be enforced. However, more than half of youths in foster care do not receive a medication evaluation.35 Of youth in the New York State Medicaid program who were prescribed an antipsychotic in the first quarter of 2008, 74% did not have a metabolic screening.36

The present findings would be of interest to state child welfare and Medicaid agencies and could be used to guide antipsychotic monitoring programs and policies. For one, treatment with ≥2 antipsychotics concomitantly should trigger a full clinical review.37 Identifying groups most vulnerable to concomitant use might help agencies better allocate resources to target the highest risk group. It might be that programs are developed to address the specific needs of different risk groups in which preauthorization is needed for children below a certain age and prospective adverse effect monitoring is implemented when treatment continues for longer than 6 months. Moreover, an integrated data system that is shared among child welfare and Medicaid agencies would enrich prospective monitoring and encourage better communication across agencies. Antipsychotic monitoring programs could have a substantial impact on financial costs associated with current pharmacy expenses as well as future costs resulting from complications of weight gain and metabolic adverse effects.

Consultation and oversight of psychotropic prescribing to youth in child welfare is variable and not systematic in many US states. Few states have implemented psychotropic medication review or consultation by a health care professional, and others have established databases to track informed consent and to review prescribing practices across placement settings, region, and clinicians.34 Such databases, when linked to state mental health data and outcomes, are ideal for assisting state agencies in providing coordinated oversight to monitor the appropriateness and quality of care for youth in state custody.

The study has several limitations. More recent data were not available, and it is possible that the study might underestimate current practice in concomitant use. Nonetheless, the present study of within therapeutic class use (ie, ≥2 antipsychotics) is a first step and offers a unique contribution to the field. Moreover, it was not possible to know if a youth did not receive antipsychotic medications because he did not need them or he could not access services. The cross-sectional nature of the study cannot imply causality. Given the geographical locale focused on 1 large state Medicaid program, the findings might not generalize to national patterns. The general trends reported here are consistent with other epidemiologic studies, and thus provide some evidence that these data are similar to other Medicaid populations. Child welfare enrollment files were not used to identify youth in foster care. Case identification from Medicaid files might overrepresent youth with longer duration of foster care involvement and those who use more mental health services.23 However, those who remain in foster care longer and use the most mental health services are the subset of most concern. Although no one method is perfect, Medicaid program category codes can be more easily reproduced by investigators who wish to replicate the study. Moreover, the continuously enrolled population is likely the most impaired subset of youth, and care patterns might be quite different for those who lose eligibility for various reasons. Small cell sizes resulting from the age by foster care group stratification limit robust subgroup analyses. Dosing was not assessed to determine if concomitant use was associated with lower daily doses. Others have reported that increases in antipsychotic use have not corresponded with increases in daily doses.12 Antipsychotic duration is not a measure of compliance or consumption. Finally, the lack of information on illness severity, treatment decisions, and clinical outcomes prohibits conclusions about the appropriateness of treatment.

CONCLUSIONS

The growing complexity of antipsychotic medication use among youths calls for research on the effect of dosing and drug-drug interactions on weight gain and metabolic adverse effects. Longitudinal data are needed to determine if antipsychotic polypharmacy is preceded by failure of an adequate trial of monotherapy. Temporal associations among system-level policies, family factors, and youth factors and how this influences the use of complex psychotropic regimens will be important questions for future research. Fortunately, there is a national interest in establishing better oversight of psychotropic use among youth in foster care. Hopefully this will lead to better care coordination, less inappropriate prescribing, and better mental health care for youth in child welfare.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The work was supported by National Institute of Mental Health grant MH65306 (to Dr dosReis).

All authors made substantial intellectual contribution to the conception and design of the study, contributed to the writing and revising of the manuscript for its intellectual content, and approved the final version; Drs dosReis and Rothbard and Ms Noll contributed to acquisition of data; and Drs dosReis, Rubin, Riddle, and Rothbard, Ms Noll, and Ms Yoon contributed to analysis and interpretation.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: Dr Riddle was an expert witness in a legal matter that involved Teva Pharmaceuticals; the other authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

- SGA

- second-generation antipsychotic

- ADHD

- attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder

- SSI

- Supplemental Security Income

- TANF

- Temporary Assistance for Needy Families

- OR

- odds ratio

- CI

- confidence interval

REFERENCES

- 1. dosReis S, Zito JM, Safer DJ, Soeken KL. Mental health services for youths in foster care and disabled youths. Am J Public Health. 2001;91(7):1094–1099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Raghavan R, Zima BT, Andersen RM, Leibowitz AA, Schuster MA, Landsverk J. Psychotropic medication use in a national probability sample of children in the child welfare system. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2005;15(1):97–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zima BT, Bussing R, Crecelius GM, Kaufman A, Belin TR. Psychotropic medication treatment patterns among school-aged children in foster care. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 1999;9(3):135–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zito JM, Safer DJ, Zuckerman IH, Gardner JF, Soeken K. Effect of Medicaid eligibility category on racial disparities in the use of psychotropic medications among youths. Psychiatr Serv. 2005;56(2):157–163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Breland-Noble AM, Elbogen EB, Farmer EMZ, Wagner HR, Burns BJ. Use of psychotropic medications by youths in therapeutic foster care and group homes. Psychiatr Serv. 2004;55(6):706–708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zito JM, Safer DJ, Sai D, et al. Psychotropic medication patterns among youth in foster care. Pediatrics. 2008;121(1). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/121/1/e157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rubin DM, Feudtner C, Localio R, Mandell DS. State variation in psychotropic medication use by foster care children with autism spectrum disorder. Pediatrics. 2009;124(2). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/124/2/e305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Olfson M, Crystal S, Huang C, Gerhard T. Trends in antipsychotic drug use by very young, privately insured children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;49(1):13–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Olfson M, Blanco C, Liu L, Moreno C, Laje G. National trends in the outpatient treatment of children and adolescents with antipsychotic drugs. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63(6):679–685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cooper WO, Arbogast PG, Ding H, Hickson GB, Fuchs DC, Ray WA. Trends in prescribing of antipsychotic medications for US children. Ambul Pediatr. 2006;6(2):79–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Patel NC, Sanchez RJ, Johnsrud MT, Crismon ML. Trends in antipsychotic use in a Texas Medicaid population of children and adolescents, 1996–2000. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2002;12(3):221–229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Domino ME, Swartz MS. Who are the new users of antipsychotic medications? Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59(5):507–514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Constantine R, Tandon R. Changing trends in pediatric antipsychotic use in Florida's Medicaid program. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59(10):1162–1168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kalverdijk LJ, Tobi H, van den Berg PB, et al. Use of antipsychotic drugs among Dutch youths between 1997 and 2005. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59(5):554–560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Correll CU. Multiple antipsychotic use associated with metabolic and cardiovascular adverse events in children and adolescents. Evid Based Ment Health. 2009;12(3):93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Crystal S, Olfson M, Huang C, Pincus H, Gerhard T. Broadened use of atypical antipsychotics: safety, effectiveness, and policy challenges. Health Aff (Millwood). 2009;28(5):w770–w781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Centorrino F, Fogarty KV, Sani G, Salvatore P, Cimbolli P, Baldessarini RJ. Antipsychotic drug use: McLean Hospital, 2002. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2005;20(5):355–358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ganguly R, Kotzan JA, Miller LS, Kennedy K, Martin BC. Prevalence, trends, and factors associated with antipsychotic polypharmacy among Medicaid-eligible schizophrenia patients, 1998–2000. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(10):1377–1388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gilmer TP, Dolder CR, Folsom DP, Mastin W, Jeste DV. Antipsychotic polypharmacy trends among Medicaid beneficiaries with schizophrenia in San Diego County, 1999–2004. Psychiatr Serv. 2007;58(7):1007–1010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lurie N, Popkin M, Dysken M, Moscovice I, Finch M. Accuracy of diagnoses of schizophrenia in Medicaid claims. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1992;43(1):69–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Walkup JT, Boyer CA, Kellermann SL. Reliability of Medicaid claims files for use in psychiatric diagnoses and service delivery. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2000;27(3):129–139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lessler JT, Harris BSH. Medicaid as a Source for Postmarketing Surveillance Information, Final Report. Volume I: Technical Report Research Triangle Park, NC: Research Triangle Institute; 1984 [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rubin DM, Pati S, Luan X, Alessandrini EA. A sampling bias in identifying children in foster care using Medicaid data. Ambul Pediatr. 2005;5(3):185–190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. dosReis S, Zito JM, Buchanan RW, Lehman AF. Antipsychotic dosing and concurrent psychotropic treatments for Medicaid-insured individuals with schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2002;28(4):607–617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Halfon N, Berkowitz G, Klee L. Mental health service utilization by children in foster care in California. Pediatrics. 1992;89(6 pt 2):1238–1244 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Covell NH, Jackson CT, Evans AC, Essock SM. Antipsychotic prescribing practices in Connecticut's public mental health system: rates of changing medications and prescribing styles. Schizophr Bull. 2002;28(1):17–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Goren JL, Parks JJ, Ghinassi FA, et al. When is antipsychotic polypharmacy supported by research evidence? Implications for QI. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2008;34(10):571–582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Burns BJ, Phillips SD, Wagner HR, et al. Mental health need and access to mental health services by youths involved with child welfare: a national survey. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;43(8):960–970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Raghavan R, Inoue M, Ettner SL, Hamilton BH, Landsverk J. A preliminary analysis of the receipt of mental health services consistent with national standards among children in the child welfare system. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(4):742–749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Correll CU, Carlson HE. Endocrine and metabolic adverse effects of psychotropic medications in children and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45(7):771–791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Correll CU, Manu P, Olshanskiy V, Napolitano B, Kane JM, Malhotra AK. Cardiometabolic risk of second-generation antipsychotic medications during first-time use in children and adolescents. JAMA. 2009;28 (16):1765–1773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Fedorowicz VJ, Fombonne E. Metabolic side effects of atypical antipsychotics in children: a literature review. J Psychopharmacol. 2005;19(5):533–550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ray WA, Chung CP, Murray KT, Hall K, Stein CM. Atypical antipsychotic drugs and the risk of sudden cardiac death. N Engl J Med. 2009;15 (3):225–235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Naylor MW, Davidson CV, Ortega-Piron DJ, Bass A, Gutierrez A, Hall A. Psychotropic medication management for youth in state care: consent, oversight, and policy considerations. Child Welfare. 2007;86(5):175–192 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Zima BT, Bussing R, Crecelius GM, Kaufman A, Belin TR. Psychotropic medication use among children in foster care: Relationship to severe psychiatric disorders. Am J Public Health. 1999;89(11):1732–1735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Essock SM, Covell NH, Leckman-Westin E, et al. Identifying clinically questionable psychotropic prescribing practices for Medicaid recipients in New York state. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60(12):1595–1602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Crismon ML, Argo T. The use of psychotropic medication for children in foster care. Child Welfare. 2009;88(1):71–100 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]