Summary

It is difficult to predict the compaction of Guglielmi detachable coils (GDC) after endovascular surgery for aneurysms. Therefore, we studied the relationship between the coil packing ratio and compaction in 62 patients with acute ruptured intracranial aneurysms that were small (<10 mm) had a small neck (<4 mm) and were coil-embolized with GDC-10.

We recorded the maximum prospective coil length, L, as the length that correspond with the volume of packed coils occupying 30% of the aneurysmal volume. L was calculated as L (cm) = 0.3 × a × b × c and the coil packing ratio expressed as packed coil length/L × 100, where a, b, and c are the aneurysmal height, length, and width in mm, respectively. Angiographic follow-up studies were performed at three months and one and two years after endovascular surgery.

Of the 62 patients, 16 (25.8%) manifested angiographic coil compaction (ten minor and six major compactions); the mean coil packing ratio was 51.9 ±13.4%. The mean coil packing ratio in the other 46 patients was 80.5±20.2% and the difference was statistically significant (p<0.01). In all six patients with major compaction the mean packing ratio was below 50%.

We detected 93.8% of the compactions within 24 months of coil placement. In patients with small, necked aneurysms, the optimal coil packing ratio could be identified with the formula 0.3 × a × b × c. The probability of compaction was significantly higher when the coil packing ratio was under 50%. To detect coil compaction post-embolization, follow-up angiograms must be examined regularly for at least 24 months.

Key words: aneurysm, coil packing ratio, Guglielmi detachable coil, embolization

Introduction

Although the treatment of intracranial aneurysms with Guglielmi detachable coils (GDC) is now routine, problems remain and long-term results require further study. One problem in the chronic stage after endovascular surgery is coil compaction1-4 prevent its occurrence, the necessity of tight packing has been stressed5,6.

We retrospectively examined the relationship between the coil packing ratio and coil compaction in patients who had undergone endovascular surgery using GDC to treat small ruptured aneurysms with a small neck. This relationship is considered an objective index of the coil length required to occupy a percentage of the aneurysmal lumen volume. Here we propose a simple method for determining the appropriate coil packing ratio in efforts to anticipate and prevent post-embolization coil compaction.

Material and Methods

We selected 62 patients whose aneurysmal dome had a maximum diameter of <10 mm, whose aneurysmal neck size was <4 mm, and who manifested no evidence of intraluminal thrombus on pre-operative cerebral angiograms. Our study population consisted of 17 men and 45 women ranging in age from 25 to 85 years (mean 59.9 years). GDC aneurysm occlusion was performed within 48 hr of the primary haemorrhage in 40 patients (64.5%); 22 (35.5%) were treated between three and six days post-haemorrhage.

Endovascular surgery was performed via the transfemoral approach with the patient under general anesthesia. In all patients, a Tracker-10 microcatheter with a two-tip marker (Target Therapeutics, San Jose, CA, USA) was used for endovascular catheterization; for coil packing we used GDC-10,3D, 2D, standard, soft, and ultrasoft coils. The size of each aneurysm was measured in three planes (height, length, and width) on anteroposterior- and lateral-view digital subtraction angiographs. To calculate the volume of the aneurysmal sac before embolization we used the formula

where a, b, and c are the aneurysmal height, length, and width in mm, respectively. The aneurysms were embolized by packing as densely as possible with detachable coils. Embolization was stopped when angiographically complete obliteration was achieved. We recorded the type and number of all GDCs used for aneurysm occlusion.

We considered the coils to be cylindrical and calculated their volumes with the formula V=π (p/2)2 × L × 10, where l is the coil length in cm, and p the coil diameter, based on the diameter of 0.241 mm for GDC10-soft coils and 0.254 mm for GDC10-3D, -2D, standard, and ultrasoft coils. The diameter of each type of coil is published by Boston Scientific, Target (Fremont, CA).

Optimal Coil Packing Ratio Determined by the Length of the Coil Used for Embolization

Satoh et Al.5, who used platinum coils to pack a glass-tube aneurysm model as tightly as possible, reported that 30% of the aneurysmal volume represented the maximum packed coil volume.

Therefore, we considered the appropriate packed coil volume to be that which corresponded to 30% of the aneurysmal volume and calculated the maximum embolized coil volume as π(p/2)2 x L x 10 = 4π (a/2)(b/2)(c/2)/3 × 0.3, where L (cm) is the so-called maximum prospective coil length and p represents a GDC-10 diameter of 0.25 mm derived from the actual diameter of GDC10-soft (0.241 mm) and GDC-10-3D, 2D, standard, and ultrasoft coils (0.254 mm). Therefore,

The coil packing ratio, based on coil length, was expressed as

Although we approximated the aneurysmal volume, our results indicate that there is a relationship between the coil packing ratio and coil compaction. We determined the coil packing ratio at the end of the procedure based on the coil length used for embolization. Using the coil length necessary to occupy the aneurysmal lumen, we compared the coil packing ratio in patients who required re-embolization due to coil compaction and those who did not.

Angiographic Follow-up Studies

We obtained post-embolization follow-up cerebral angiograms at three months and one and two years and used multiple projections with selective contrast injections to define any residual lesions. To assess coil compaction, we re-inspected the angiographic appearance of each aneurysm at the end of the embolization procedure and recorded the amount of contrast material required in follow-up studies to fill the aneurysm. When the area of residual filling measured less than 2 mm, we recorded minor coil compaction; when it exceeded 2 mm, a notation of major compaction was made.

Statistical Analysis

All values are expressed as the mean ± SD of the mean. Student's t-test was used for statistical analysis and differences of p<0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

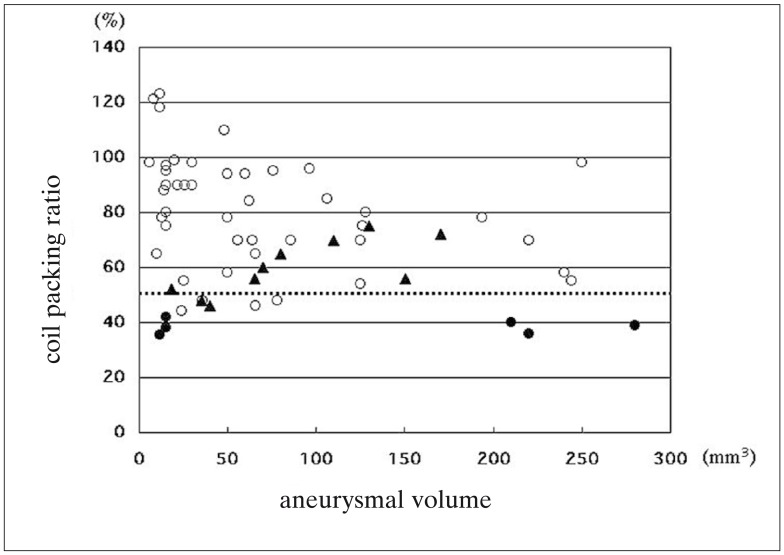

We recorded the aneurysmal size and location, the packing coil length, the maximum prospective coil length, determined as 0.3 x (abc), and coil packing ratio and plotted the relationship between the coil packing ratio and aneurysmal volume (figure 1). In all 62 patients the coil packing ratio was between 35.5 and 121.3%; in 58 (93.5%) it was below 100%.

Figure 1.

Plot graph showing the relationship between the coil packing ratio and aneurysmal volume (open circles;no compaction, black triangles;minor compaction, black circles;major compaction). The dotted line indicates a coil packing ratio of 50%

Post-embolization angiograms detected coil compaction in 16 of the 62 patients (25.8%); in six there was major- and in ten minor coil compaction. Notably, among the six patients with major compaction, three had aneurysms <50 mm3. Our data show that all patients with a coil packing ratio below 50% manifested major coil compaction (figure 1).

The mean aneurysmal volume in patients with no-, minor-, and major compaction was 68.8 ± 68.4,86.8 ± 51.3, and 125.3 ± 124.3 mm3, respectively, and there was no significant difference among the three groups.

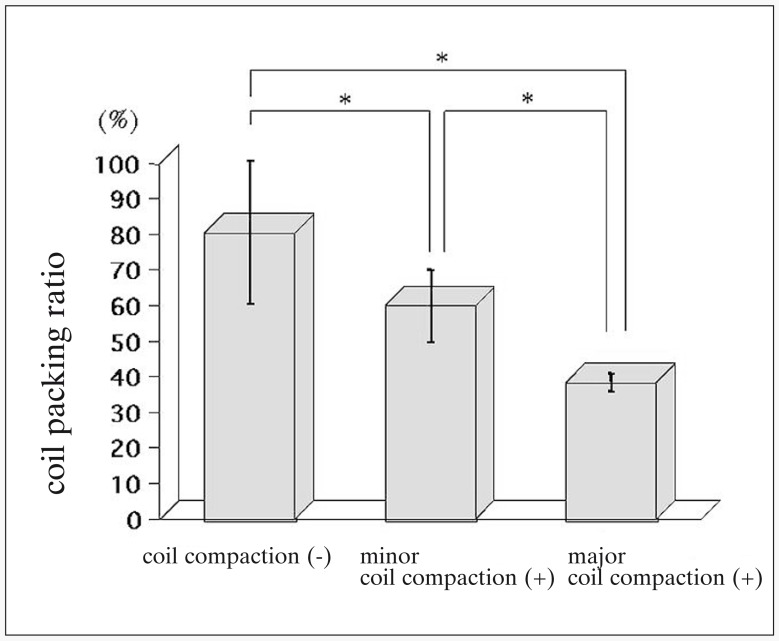

In 46 patients there was no detectable coil compaction; the mean coil packing ratio in this group was 80.5 ± 20.2%. On the other hand, the mean coil packing ratio in the 16 patients with compaction was 51.9 ± 13.4%; it was 60.0 ± 10.2% in patients with minor- and 38.4 ± 2.5% in those with major coil compaction. The coil packing ratio was significantly correlated with the degree of compaction (p<0.01, figure 2).

Figure 2.

Bar graph showing the coil packing ratio in cases without-, with minor-, and with major coil compaction. The difference among the three groups was statistically significant (*p<0.01).

Angiographic Evaluation during Long-Term Follow-up

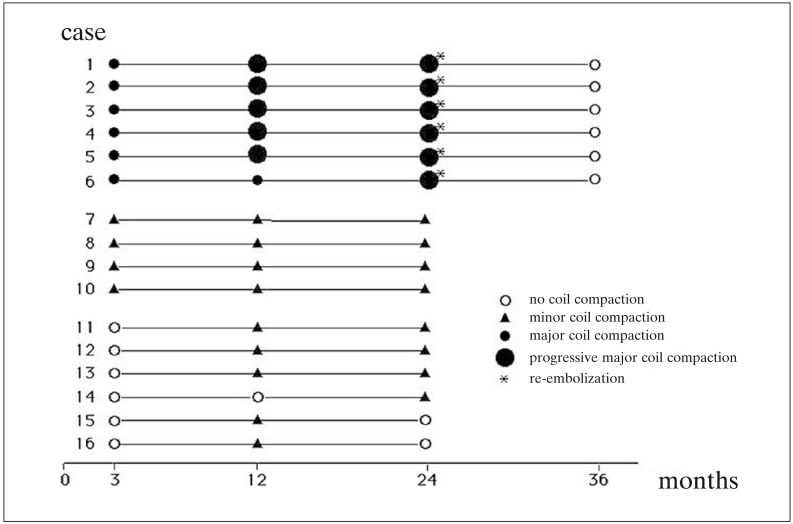

None of the 62 patients suffered rebleeding in the course of clinical follow-up; 16 manifested angiographic coil compaction and in only ten of these (62.5%) was this detected on three month follow-up angiograms (figure 3). At twelve months, 15 of the 16 patients (93.8%) had angiographic evidence of compaction. Of the six patients with major coil compaction (cases 1-6), five demonstrated progressive compaction over the course of two years. As the degree of compaction was increased in all six patients on angiograms obtained at 24 months, they underwent re-embolization at 24.9 ± 1.1 months after their first endovascular surgery.

Figure 3.

Timing of the manifestation of coil compaction in 16 patients with major (n=6) or minor compaction (n=10) on post-embolization follow-up angiograms (open circles, no compaction;black triangles, minor compaction;black circles, major compaction; large black circles, progressive major coil compaction; asterisks identify patients who underwent re-embolization).

The ten patients with minor coil compaction (cases 7-16) were followed conservatively; over the course of 24 month follow-up, there was no evidence of progressively worsening compaction (figure 3). Case 14 was free of compaction at three and twelve months, however, an angiogram obtained at 24 months post-embolization demonstrated evidence of minor coil compaction. Cases 15 and 16 showed no compaction at three, and minor compaction at twelve months, at 24 months they demonstrated a reduction in the residual lumen of the embolized aneurysm and a notation of no compaction was made at that time.

Representative Cases

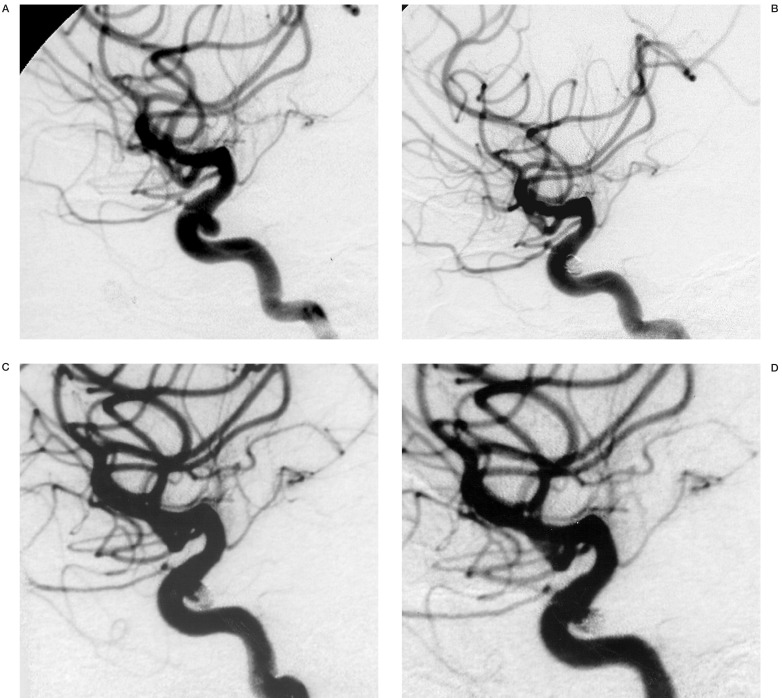

Minor Coil Compaction (figure 4)

This 58-year-old woman presented with rupture of a left ICA aneurysm. A CT scan showed marked SAH. Neurological examination revealed only severe headache; her Hunt and Hess grade was II. The aneurysm measured 4.0 × 4.0 × 4.0 mm, its orifice was 3.0 mm (figure 4A). It was occluded with four GDC-10. The total length of the coils used for embolization was 12 cm, the maximum prospective coil length was 19.2 cm (4 × 4 × 4 × 0.3), and the coil packing ratio was 62.5% (12/19.2 × 100). An angiogram obtained immediately after embolization showed no residual aneurysmal neck (figure 4B) and she was discharged home fully recovered. Although on the three month follow-up angiogram there was no evidence of coil compaction, angiographic images obtained at one and two years post-embolization demonstrated minor compaction (figure 4C,D). The open space in the aneurysmal lumen measured less than 2 mm and did not increase over the course of two year follow-up and she was not treated by re-embolization. She has remained neurologically intact there has been no angiographic change in the aneurysm over the course of 36-month follow-up.

Figure 4.

A 58-year-old woman with a ruptured left ICA aneurysm and minor coil compaction. A) Left internal carotid angiogram showing an aneurysm at the paraclinoid portion. B) Left internal carotid angiogram obtained immediately after GDC embolization demonstrating complete aneurysmal occlusion. Left internal carotid angiogram obtained one year after GDC embolization demonstrating coil compaction and a small open C. space in the aneurysm. D) Left internal carotid angiogram obtained two years after GDC embolization demonstrating no change in the open space in the aneurysm.

Discussion

We selected patients with small-necked, small aneurysms for our study, because complete aneurysm occlusion was reportedly obtained in 85% of small (<4 mm) and only 15% of wide-necked aneurysms7. We deliberately de-selected large aneurysms because of their tendency to have a wide neck 8 and because large aneurysms (>10 mm) require the use of larger coils (e.g. GDC-18). As it is difficult to calculate the optimal coil packing ratio when differently-sized coils are used, we chose patients with aneurysms smaller than 10 mm who could be treated with GDC-10.

The relationship between the coil packing ratio and post-embolization coil compaction has been investigated5,6. Satoh et Al.5, who examined embolization rates using aneurysm models made of glass tubes, showed that the maximum embolized volume was 32.0 - 33.3%, even when the aneurysms were packed as tightly as possible with platinum coils. Thus, most of the aneurysmal cavity was not filled with coils. The clotting process, which interferes with the introduced coils, plays a role inside the aneurysmal sac, which becomes progressively occupied by coils and fresh clot. For our study we selected aneurysms whose size did not exceed 10 mm, and aimed at obtaining a packed coil volume that represented 30% of the aneurysmal volume. We determined the optimal coil density based on the coil length required for coil packing using the formula 0.3 × (abc) and in our series, the coil packing ratio ranged between 35.5 and 121.3%; in 93.5% of our patients, it was under 100%.

We found that the incidence of coil compaction was significantly higher in aneurysms whose embolized volume after the first procedure was below 50%. We detected coil compaction within three months of embolization in only ten of 16 patients (62.5%); in 15 of these (93.8%) compaction was evident at 12 months. We found that four of ten patients with minor coil compaction manifested no angiographic changes at 3, 12, and 24 months after their initial endovascular treatment; in two patients there was a reduction in the residual lumen of the embolized aneurysm at 24 months and they required no further treatment. On the other hand, in five of six patients with major compaction we noted a tendency for its enlargement on follow-up angiograms and they underwent a 2nd embolization procedure 24 months after the first. In such cases, the length of angiographic follow up must not be shorter than two years.

Conclusions

We introduced the formula 0.3 × (abc) to determine optimal coil density based on the coil packing length of GDC-10 used to embolize small aneurysms with narrow necks. We found that the incidence of coil compaction was significantly higher in aneurysms with a coil packing ratio lower than 50%. Follow-up angiograms must be obtained for at least 24 months to detect coil compaction.

References

- 1.Bavinzski G, Richling B, et al. Endosaccular occlusion of basilar artery bifurcation aneurysms using electrically detachable coils. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1995;134:184–189. doi: 10.1007/BF01417687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Redekop GJ, Durity FA, et al. Management-related morbidity in unselected aneurysms of the upper basilar artery. J Neurosurg. 1997;87:836–842. doi: 10.3171/jns.1997.87.6.0836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Turjman F, Massoud TF, et al. Predictors of aneurysmal occlusion in the period immediately after endovascular treatment with detachable coils: a multivariate analysis. Am J Neuroradiol. 1998;19:1645–1651. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Uda K, Goto K, et al. Embolization of cerebral aneurysms using Guglielmi detachable coils - problems and treatment plans in the acute stage after subarachnoid haemorrhage and long-term efficiency. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 1998;38:143–152. doi: 10.2176/nmc.38.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Satoh K, Matsubara S, et al. Intracranial aneurysm embolization using interlocking detachable coils. Interventional Neuroradiology. 1997;3(Suppl 2):125–128. doi: 10.1177/15910199970030S226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tamatani S, Ito Y, et al. Evaluation of the stability of aneurysms after embolization using detachable coils: correlation between stability of aneurysms and embolized volume of aneurysms. Am J Neuroradiol. 2002;23:762–767. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fernandez-Zubillaga A, Guglielmi G, et al. Endovascular occlusion of intracranial aneurysms with electrically detachable coils: correlation of aneurysm neck size and treatment results. Am J Neuroradiol. 1994;15:815–820. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Viñuela F, Duckwiler G, et al. Guglielmi detachable coil embolization of acute intracranial aneurysm: perioperative anatomical and clinical outcome in 403 patients. J Neurosurg. 1997;86:475–482. doi: 10.3171/jns.1997.86.3.0475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]