Abstract

Mental health problems (MHPs) among children with perinatal HIV infection have been described prior to and during the highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) era. Yet child, caregiver and socio-demographic factors associated with MHPs are not fully understood. We examined the prevalence of MHPs among older children and adolescents with perinatal HIV exposure, including both perinatally HIV-infected (PHIV+) and perinatally HIV-exposed but uninfected (PHEU) youth. Our aims were to identify the impact of HIV infection by comparing PHIV+ and PHEU youth and to delineate risk factors associated with MHPs, in order to inform development of appropriate prevention and intervention strategies. Youth and their caregivers were interviewed with the Behavior Assessment System for Children, 2nd edition (BASC-2) to estimate rates of at-risk and clinically significant MHPs, including caregiver-reported behavioral problems and youth-reported emotional problems. The prevalence of MHPs at the time of study entry was calculated for the group overall, as well as by HIV status and by demographic, child health, and caregiver characteristics. Logistic regression models were used to identify factors associated with youth MHPs. Among 416 youth enrolled between March 2007 and July 2009 (295 PHIV+, 121 PHEU), the overall prevalence of MHPs at entry was 29% and greater than expected based on recent national surveys of the general population. MHPs were more likely among PHEU than among PHIV+ children (38% versus 25%, p < 0.01). Factors associated with higher odds of MHPs at p < 0.10 included caregiver characteristics (psychiatric disorder, limit-setting problems, health-related functional limitations) and child characteristics (younger age and lower IQ). These findings suggest that PHEU children are at high risk for MHPs, yet current models of care for these youth may not support early diagnosis and treatment. Family-based prevention and intervention programs for HIV affected youth and their caregivers may minimize long-term consequences of MHPs.

Keywords: mental health problems, children and adolescents, perinatal HIV exposure, HIV infection

Introduction

Mental health problems (MHPs) among children and adolescents (youth) with perinatal HIV infection, including attention problems, hyperactivity, anxiety, and depression, have been described prior to and during the highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) era (Brouwers et al., 1995; Brown, Lourie, & Pao, 2000; Mellins et al., 2009; Papola, Alvarez, & Cohen, 1994; Sharko, 2006). Prevalence and types of problems vary due to assessment and sampling methodologies, but rates of MHPs in both perinatally HIV-infected (PHIV+) and perinatally HIV-exposed but uninfected (PHEU) are higher than expected relative to the general US youth population (Bauman, Silver, Draimin, & Hudis, 2007; Gadow et al., 2010; Mellins et al., 2003, 2009; Nozyce et al., 2006).

Many factors may contribute to the emergence of MHPs among children born to women with HIV (Bauman, Camacho, Silver, Hudis, & Draimin, 2002; Bauman et al., 2007; Havens & Mellins, 2008). Prenatally, the fetus may be exposed to maternal immune dysregulation and antiretroviral (ARV) medications, infections (e.g., sexually transmitted diseases; cytomegalovirus) and teratogens (e.g., alcohol and illicit drugs). Postnatally, neurotoxicity associated with HIV infection, aberrant immune activation (Mekmullica et al., 2009), and intermittent or suboptimal ARV treatment may confer additional significant risks upon children who are PHIV+. Children with perinatal HIV exposure, whether or not HIV-infected, often share other risks, including family histories of substance abuse and psychiatric disorders, family loss, discrimination, poverty, inadequate housing and exposure to violence (Donenberg & Pao, 2005; Havens & Mellins, 2008; Steele, Nelson, & Cole, 2007), all of which have been associated with increased rates of MHPs during childhood and adolescence (Achenbach, Howell, Quay, & Conners, 1991; Bradley & Corwyn, 2002; McCarty, McMahon & Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group, 2003).

In this investigation, we examined the prevalence of MHPs among older children and adolescents with perinatal HIV exposure, including both PHIV+ and PHEU youth. Our aims were to identify the impact of HIV infection by comparing PHIV+ and PHEU youth and to delineate youth, caregiver and socio-demographic risk factors that contribute to MHPs.

Methods

Study population

Our analyses used cross-sectional data from the Adolescent Master Protocol (AMP) of the Pediatric HIV/AIDS Cohort Study (PHACS), a prospective, longitudinal study examining the impact of HIV infection and ARV therapy on perinatally HIV exposed youth. Fifteen AMP sites, including 14 academic medical centers and one community-based organization, enrolled PHIV+ and PHEU youth during 2007–2009. The majority of sites were located in urban settings across the United States (US), including Puerto Rico, and provided primary and tertiary care to PHIV+ youth and families; all 15 sites recruited both PHIV+ and PHEU youth. Eligibility criteria included: 1) perinatal HIV exposure; 2) ages 7 to < 16 years; and, 3) among PHIV+ participants, engaged in medical care with available ARV history. Exclusion criteria included: HIV acquired by other than maternal-child transmission (e.g., blood products, sexual contact or IV drug use) as documented in the medical record.

Procedures

Institutional Review Boards (IRB) at all participating sites and the Harvard School of Public Health approved the study. Potential participants were identified through medical chart review or case conferences by local site providers. Eligible participants were approached by primary HIV care providers or research staff and the AMP protocol was described in detail. Parent(s) or legal guardians provided written informed consent for child and caregiver participation. Youth provided assent per local IRB guidelines. Given confidentiality and HIPAA regulations, information regarding potential participants who refused enrollment was not available.

Data for this analysis were collected at the study entry and six month study visit. The mental health and psychosocial evaluations are part of a large biopsychosocial assessment protocol that included cardiology, neurology, immunology and others. To reduce undue burden for youth and caregiver, the entry evaluation included in this analysis was administered over two sessions linked to the first two study visits; youth mental health, caregiver health and demographics at study entry, and assessment of caregiver functioning at the next study visit, within six months of the entry visit (±2 months). Psychometric assessment instruments were administered by centrally trained psychologists, in English and in Spanish for those instruments with an available Spanish version, via face-to-face interviews to assure item comprehension and response completeness. Interviews were conducted separately in a private room.

Measures

Mental health functioning

The Behavior Assessment System for Children-Second Edition, (BASC-2; Reynolds & Kamphaus, 2004) is a validated, reliable multidimensional tool used to evaluate children’s and adolescents’ emotions, self-perceptions and behavioral functioning. Normative data are based on samples representative of recent US population figures. Since caregivers and youth provide unique perspectives on psychological adjustment (Achenbach, McConaughy, & Howell, 1987), we evaluated both, using the BASC-2 Self-Report of Personality (SRP) and BASC-2 Parent Rating Scale (PRS). MHPs were defined as BASC-2 Behavioral Symptoms Index (BSI) or Emotional Symptoms Index (ESI) score(s) in the “at-risk” (T-score 60–69) or “clinically significant” (T-score ≥70) range. The BSI includes scales measuring hyperactivity, aggression, depression, attention problems, atypicality and withdrawal and reflects overall level of problematic behavior observed by the parent/caregiver. The ESI includes scales measuring social stress, anxiety, depression, sense of inadequacy, self-esteem and self-reliance and identifies cumulative effects of multiple emotional difficulties reported by youth.

Internal consistency reliabilities of the BASC-2 composites and scales are high, above 0.90 for both the BSI of the parent report and the ESI of the youth self-report (BASC-2; Reynolds & Kamphaus, 2004). Reliabilities are consistent between females and males and at different age levels. High test-retest reliabilities are also reported. For the Spanish forms, the internal consistency reliabilities of the parent report composite scales are moderate to high, ranging from 0.78 to 0.93. The reliabilities for the youth self-report composite scales are moderate to high, ranging from 0.77 to 0.95.

Demographic and health information

Child and caregiver socio-demographic information was collected at study entry. Included in the analyses were: demographic characteristics (gender, age, race, ethnicity); prenatal ARV exposure; child and family psychosocial characteristics (child knowledge of HIV status, child Full Scale IQ, primary caregiver type [biological mother, other relative, non-relative], caregiver education level), and biological markers of child’s HIV disease (nadir CD4+ count, Center for Disease Control [CDC] clinical classification [Center for Disease Control, 1994], and HAART use).

Caregiver functioning

The Client Diagnostic Questionnaire (CDQ; Aidala et al., 2004) was developed and validated for English-speaking populations affected by HIV; the CDQ was also translated into Spanish and field tested among diverse Latino cultural groups, including Puerto Rican, Mexican, Dominican and Cuban. The CDQ was adapted from the PRIME-MD, a validated screening tool for assessing psychiatric disorders in primary care settings (Spitzer, Kroenke, & Williams, 1999). The CDQ provided a summary measure of caregiver psychiatric status that indicated presence or absence of any psychiatric disorder (e.g., depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder). For the diagnosis of any disorder, the sensitivity, specificity and overall accuracy of the CDQ were 91%, 78%, and 85%, respectively. Caregiver cognitive status was evaluated with the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (WASI; Wechsler, 1999), a widely used, nationally standardized, and reliable measure of intelligence for English-speaking children and adults, ages 6–89 years.

Caregiver functional status was evaluated at entry with a study-specific caregiver health questionnaire to assess health-related physical symptoms and limitations. Caregivers described their current health conditions, including HIV disease, cardiac problems, mental health problems, hypertension, diabetes and others. They answered six questions, in English or Spanish, regarding the impact of health problems on activities of daily living, such as their ability to work inside and outside the home (for example, “is there any kind of housework you cannot do because of your health?”). Number of caregiver limitations experienced (0 to ≥4) was considered in analyses.

Parent-child relationship

The Parent-Child Relationship Inventory (PCRI; Gerard, 1994), administered at the 6-month visit, was used to assess the parent-child relationship and parenting disposition. The PCRI includes seven content scales and two validity indicators (Social Desirability and Inconsistency). The PCRI was standardized on more than 1,100 parents across the United States; each content scale has a mean of 50 and standard deviation of 10. The PCRI has an overall median consistency of 0.82 across subgroups and has good test-retest reliability, with a mean autocorrelation of 0.81 for interviews administered one week apart (range 0.68–0.93) (PCRI; Gerard, 1994). Four content scales (Parent Support, Involvement, Communication, Limit-Setting) were selected a priori for analyses; problematic relationships were defined if any of the T-scores for these four scales was less than 40.

Statistical methods

MHP prevalence at study entry was calculated for the group overall, as well as by HIV status and demographic, child health and caregiver characteristics. The association of MHPs with infection status and with each covariate was examined using Fisher’s exact test or a Chi-square test as appropriate for categorical variables, and t-test for continuous variables.

One sample t-tests were used to evaluate whether mean behavioral domain T-scores significantly differed from BASC-2 norms. Logistic regression models were used to identify factors associated with MHPs. Three sets of models were developed: (1) PHIV+, (2) PHEU, and (3) combined over infection status. Variables associated with the outcome in unadjusted analyses (p ≤ 0.10) were included in the models. Due to the desire to control for a broad range of potential confounders, variables with p < 0.10 in multivariable models were defined as being associated with MHPs. In the third set of models, factors that might confound any effect of infection status on MHPs were explored. Covariates were added individually into a model that included HIV-infection status. Variables that changed the effect of HIV-infection status by ≥15% were retained in the final model. Due to collinearity, PCRI content scales identified as significant predictors were included individually in each model.

An a priori decision was made to include age in all models regardless of significance. A post hoc decision was made to explore potential interactions between infection status and gender and between caregiver type and caregiver psychiatric status, by including separate interaction terms in models and assessing their significance using likelihood ratio tests.

The missing indicator method was used for covariates with >5% of missing values so that participants with missing information could be included in the analyses (Jones, 1996). To explore the effect of missing caregiver data, we compared participants with missing and complete caregiver data on demographic, child/family psychosocial characteristics, and caregiver information. We also conducted sensitivity analyses on all three sets of models, restricted to participants with complete caregiver data. Analyses were conducted using SAS 9 software (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

Results

As of November 2009, 449 PHIV+ and 227 PHEU youth were enrolled in AMP. Of these 676 enrollees, 457 were expected to have completed their entry and 6-month study visits by the time of this analysis; 419 (92%) completed both. Exclusion of three invalid BASC-2 evaluations due to patterned or inconsistent responses resulted in a sample size of 416 youth. Table 1 presents a summary of study population demographic, health and caregiver characteristics. In the cohort, 295 (71%) were PHIV+, 52% female, and the majority were Black and non-Hispanic. Among PHIV+, 32% had detectable viral load (HIV RNA >400 copies/mL), 26% had CDC class C diagnosis, and 67% knew their HIV status.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 416 PHACS AMP study participants, overall and according to HIV infection status.

| Child’s HIV infection status | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Total (N = 416) | PHIV + (N = 295) | PHIV − (N = 121) | P-value |

| Child characteristics | ||||

| Female sex | 217 (52.2%) | 164 (55.6%) | 53 (43.8%) | 0.03a |

| Black raceb | 303 (77.1%) | 223 (80.8%) | 80 (68.4%) | 0.01a |

| Hispanic ethnicityb | 97 (23.4%) | 58 (19.7%) | 39 (32.2%) | 0.01a |

| Age at evaluation < 12 years | 228 (54.8%) | 135 (45.8%) | 93 (76.9%) | <0.01a |

| Child knows HIV statusb | - | 195 (67.0%) | - | - |

| Detectable viral load at entry (>400 cp/ml) | - | 95 (32.2%) | - | - |

| CDC classification C | 77 (26.1%) | |||

| Nadir CD4 count (cells/mm3) | ||||

| <200 | - | 63 (21.4%) | - | - |

| 200–350 | - | 64 (21.7%) | - | |

| 351–500 | - | 67 (22.7%) | - | |

| >500 | - | 101 (34.2%) | - | |

| HAART before study entry | - | 278 (94.2%) | - | - |

| Child IQb | ||||

| N | 394 | 280 | 114 | |

| Mean (STD) | 86.72 (15.19) | 86.19 (15.22) | 88.01 (15.11) | 0.28c |

| Min, Max | 41, 130 | 41, 130 | 46, 120 | |

| Caregiver characteristics | ||||

| Caregiver identity | ||||

| Biological mother | 206 (49.5%) | 112 (38.0%) | 94 (77.7%) | <0.01a |

| Other relative | 110 (26.4%) | 94 (31.9%) | 16 (13.2%) | |

| Non-relative | 100 (24.0%) | 89 (30.2%) | 11 (9.1%) | |

| Single parent | 220 (52.9%) | 144 (48.8%) | 76 (62.8%) | 0.01a |

| Less than high school education | 107 (25.7%) | 76 (25.8%) | 31 (25.6%) | 0.98a |

| Income levelb | ||||

| < $20K | 207 (52.4%) | 126 (45.3%) | 81 (69.2%) | <0.01a |

| $20–40K | 111 (28.1%) | 92 (33.1%) | 19 (16.2%) | |

| >$40K | 77 (19.5%) | 60 (21.6%) | 17 (14.5%) | |

| IQ < 70b | 26 (9.3%) | 12 (6.1%) | 14 (16.9%) | <0.01a |

| Any psychiatric diagnosisb | 103 (32.0%) | 65 (28.9%) | 38 (39.2%) | 0.07a |

| ARV use during pregnancyb | 162 (45.3%) | 60 (24.5%) | 102 (90.3%) | <0.01a |

| PCRI measuresb, some or serious problem with: | ||||

| Parent support | 30 (8.8%) | 17 (7.1%) | 13 (12.9%) | 0.09a |

| Involvement | 96 (28.2%) | 71 (29.7%) | 25 (24.8%) | 0.35a |

| Communication | 85 (25.0%) | 61 (25.5%) | 24 (23.8%) | 0.73a |

| Limit-setting | 18 (5.3%) | 11 (4.6%) | 7 (6.9%) | 0.38a |

| Number of caregiver functional limitationsb | ||||

| 0 | 200 (51.7%) | 150 (54.5%) | 50 (44.6%) | 0.03a |

| 1–3 | 132 (34.1%) | 94 (34.2%) | 38 (33.9%) | |

| >4 | 55 (14.2%) | 31 (11.3%) | 24 (21.4%) | |

Chi-square test.

Some subjects were missing measurements of characteristics and are excluded from calculations of percentages; race: 23, ethnicity: 1, child knows HIV status: 4, caregiver interaction characteristics: 76, income 21, caregiver psychiatric diagnoses: 94, ARV use during pregnancy: 58, caregiver IQ: 136, number of caregiver functional limitations: 29.

T-test with equal variance.

Note: MH, mental health; HAART, highly active antiretroviral therapy; STD, standard deviation; ARV, antiretroviral; PCRI, Parent-Child Relationship Inventory.

Several characteristics differed by infection status. More PHIV+ youth than PHEU were female (56% vs. 44%, p = 0.03) and Black (81% vs. 68%, p = 0.01). PHIV+ youth were also older, from households with higher income, and had caregivers less likely to report health limitations or to have an IQ in the impaired range (Table 1). More PHEU than PHIV+ youth resided with biological mothers (78% vs. 38%, p < 0.01) and single caregivers (63% vs. 49%, p = 0.01).

Psychiatric status, parent-child relationship and cognitive status data were missing for 23%, 18% and 33% of caregivers, respectively. Reasons for missing evaluations included: caregiver refusal, insufficient time, and non-English primary language. Thirty- six BASC-2 parent reports (9%) and 15 BASC-2 self-reports (4%) were completed in Spanish; 31 (10%) CDQs were administered in Spanish by a Spanish speaking psychologist. Five CDQ evaluations (< 1%) and 12 (3%) PCRI evaluations were excluded due to invalidity.

Mental health functioning

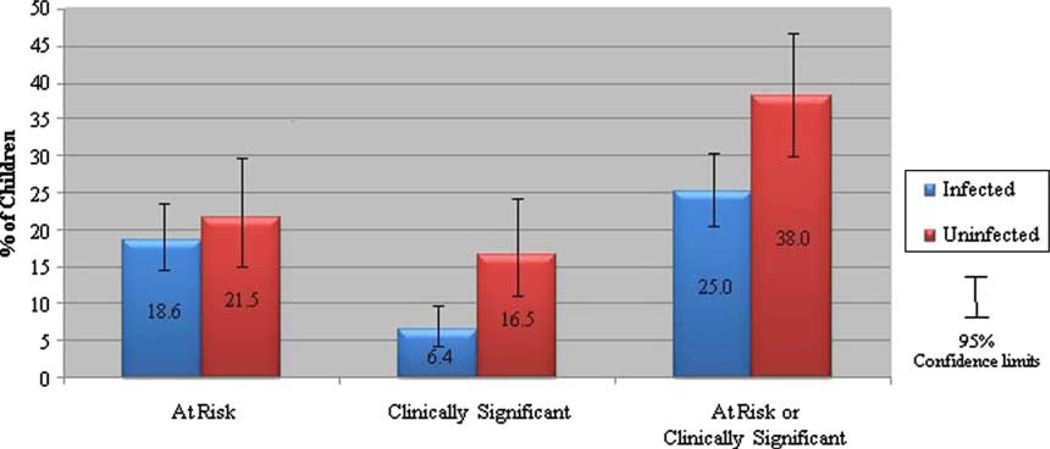

MHP prevalence was higher among PHEU children than PHIV+ children (38% versus 25%, p < 0.01, Figure 1). Caregivers reported behavioral problems, as shown by BSI scores in the at-risk or clinically significant range, for 29% of PHEU youth and 19% of PHIV+ youth (p = 0.03). Emotional problems, as shown by ESI scores in the at-risk or clinically significant range, were reported by 17% of PHEU youth and 12% of PHIV+ youth (p = 0.29).

Figure 1.

Prevalence of mental health problems by HIV infection status.

The BSI and ESI have a mean of 50 in the population with a standard deviation of 10. Relative to BASC-2 norms, BSI scores were significantly elevated for both PHEU (BSI mean SS = 54.6, SD = 12.8, p < 0.01) and PHIV+ youth (BSI mean SS = 51.5, SD = 10.2, p < 0.02). ESI scores were not elevated for PHEU or PHIV+ youth (PHEU ESI mean = 49.3, SD = 10.1, p = 0.51; PHIV+ ESI mean = 49.1, SD = 9.3, p = 0.10). The BASC-2 scores of participants living in Puerto Rico or those who completed the BASC-2 in Spanish did not differ when compared to those of other participants.

No gender differences emerged in either BSI or ESI scores for the entire group. However, when stratified by infection status, PHEU males were more likely than females to have elevated BSI scores (37% versus 18%, p = 0.04), with no significant gender difference in PHIV+ youth’s BSI scores. PHIV+ females were more likely than PHIV+ males to have elevated ESI scores (18% versus 5.9%, p < 0.01). For PHEU youth, 22% of females and 10% of males had elevated ESI scores, although this difference was not statistically significant.

Unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios (ORs) for models stratified by HIV infection status are presented in Tables 2 and 3. Among PHIV+ youth (Table 2), female gender, younger age at evaluation, lower child IQ, no prenatal ARV exposure, caregiver psychiatric disorder, ≥4 caregiver functional health limitations (versus none), and caregiver limit-setting problems were associated with MHPs in unadjusted models. In a separate model excluding caregiver limitsetting problems, caregiver-child involvement problems were associated with MHPs (OR[95%CI] = 1.99 [0.98, 4.04]). All covariates except gender remained associated with MHPs in the multivariable model. No HIV disease severity indicator or use of HAART was associated with MHPs.

Table 2.

Associations between selected characteristics and the risk of mental health problems, among HIV-infected participants (N = 295).

| Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | Adjusted P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female sex | 1.81 (1.04,3.13) | 1.60 (0.87,2.94) | 0.13 |

| Age at evaluation | |||

| ≥12 years | 0.86 (0.51,1.45) | 0.58 (0.32,1.06) | 0.08 |

| Limit-setting | |||

| Unknown | 1.39 (0.72,2.68) | 1.35 (0.53,3.45) | 0.53 |

| Some/serious problem | 6.07 (1.71,21.6) | 4.22 (1.03,17.2) | 0.04 |

| No problem | Reference | ||

| Caregiver psychiatric disorder | |||

| Unknown | 1.44 (0.74,2.80) | 1.30 (0.47,3.63) | 0.62 |

| Yes | 2.60 (1.38,4.91) | 2.25 (1.10,4.62) | 0.03 |

| No | Reference | ||

| ARV use during pregnancy | |||

| Unknown | 0.88 (0.43,1.78) | 0.95 (0.44,2.02) | 0.88 |

| Yes | 0.38 (0.17,0.86) | 0.29 (0.11,0.74) | 0.01 |

| No | Reference | ||

| Caregiver functional limitations | |||

| Unknown | 0.92 (0.29,2.95) | 1.10 (0.27,4.54) | 0.89 |

| ≥4 | 2.33 (1.02,5.30) | 2.55 (0.99,6.58) | 0.05 |

| 1–3 | 1.41 (0.78,2.56) | 1.50 (0.77,2.93) | 0.24 |

| 0 | Reference | ||

| Child IQ | |||

| Mean (STD) | 0.98 (0.96,1.00) | 0.98 (0.96,1.00) | 0.04 |

Note: OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; MH, mental health; ARV, antiretroviral; STD, standard deviation.

Table 3.

Associations between selected characteristics and the risk of mental health problems, among HIV-uninfected participants (N = 121).

| Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | Adjusted P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female sex | 0.40 (0.19,0.88) | 0.37 (0.15,0.91) | 0.03 |

| Race | |||

| Unknown | 10.9 (0.99,119) | 15.8 (1.09,229) | 0.04 |

| Black | 2.82 (1.15,6.93) | 2.94 (1.03,8.36) | 0.04 |

| White/other | Reference | ||

| Age at evaluation | |||

| ≥12 years | 0.46 (0.18,1.19) | 0.33 (0.10,1.07) | 0.07 |

| Caregiver identity | |||

| Non-relative | 3.23 (0.88,11.9) | 4.75 (0.96,23.5) | 0.06 |

| Other relative | 1.11 (0.37,3.32) | 1.00 (0.27,3.75) | 1.00 |

| Biological mother | Reference | ||

| Limit-setting | |||

| Unknown | 1.59 (0.60,4.22) | 2.16 (0.60,7.80) | 0.24 |

| Some/serious problem | 4.84 (0.89,26.4) | 6.06 (0.85,43.2) | 0.07 |

| No problem | Reference | ||

| Caregiver psychiatric disorder | |||

| Unknown | 2.48 (0.92,6.71) | 1.93 (0.45,8.26) | 0.38 |

| Yes | 3.26 (1.37,7.74) | 3.61 (1.22,10.7) | 0.02 |

| No | Reference | ||

| Caregiver functional limitations | |||

| Unknown | 2.92 (0.69,12.4) | 2.32 (0.31,17.2) | 0.41 |

| ≥4 | 2.33 (0.86,6.36) | 1.84 (0.54,6.24) | 0.33 |

| 1–3 | 1.36 (0.56,3.33) | 1.20 (0.41,3.50) | 0.73 |

| 0 | Reference |

Note: OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; MH, mental health.

Among PHEU youth (Table 3), male gender, Black race, younger age at evaluation, non-relative caregiver (versus biological mother), caregiver psychiatric disorder, ≥4 caregiver functional limitations, and caregiver limit-setting problems were associated with MHPs in unadjusted models. In a separate model excluding limit-setting problems, parent support problems were associated with MHPs (OR [95%CI] = 7.49 [1.46, 38.4]). All factors except caregiver functional limitations remained associated with MHPs in the multivariable model.

The adjusted ORs for a model including PHIV+ and PHEU youth are presented in Table 4. The association between HIV infection status and MHPs differed by gender; among males, PHIV+ youth had lower odds of MHPs than PHEU youth, while among females the odds were similar for PHEU and PHIV+ youth. Factors associated with higher odds of MHPs included younger age, lower child IQ, caregiver psychiatric disorder, ≥4 caregiver functional limitations, and caregiver limit-setting problems.

Table 4.

Associations between selected characteristics and the risk of mental health problems, overall sample (N = 416).

| Adjusted OR (95% CI) | Adjusted P-value | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Among infected youth: | ||

| Female vs. male | 1.61 (0.88,2.93) | 0.12 |

| Among uninfected youth: | ||

| Female vs. male | 0.48 (0.21,1.10) | 0.08 |

| Infection status | ||

| Among females: | ||

| Infected vs. uninfected | 1.26 (0.59,2.70) | 0.55 |

| Among males: | ||

| Infected vs. uninfected | 0.37 (0.18,0.78) | <0.01 |

| Age at evaluation | ||

| ≥12 years | 0.52 (0.31,0.88) | 0.01 |

| Limit-setting | ||

| Missing | 1.49 (0.72,3.07) | 0.28 |

| Some/serious problem | 3.85 (1.28,11.5) | 0.02 |

| No problem | Reference | |

| Caregiver psychiatric disorder | ||

| Missing | 1.33 (0.59,3.02) | 0.49 |

| Yes | 2.66 (1.50,4.70) | <0.01 |

| No | Reference | |

| Number of caregiver functional limitations | ||

| Missing | 1.59 (0.51,4.93) | 0.42 |

| ≥ 4 | 2.10 (1.01,4.34) | 0.05 |

| 1–3 | 1.55 (0.89,2.69) | 0.12 |

| 0 | Reference | |

| Child IQ | ||

| Mean (STD) | 0.98 (0.97,1.00) | 0.02 |

Note: OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; MH, mental health, STD, standard deviation.

In separate, unadjusted analyses, the association between caregiver psychiatric status and youth MHPs tended to be stronger for youth living with biological mothers as compared to youth living with other caregivers, although not statistically significant (OR = 4.51 versus 1.77, overall p for interaction term = 0.15).

Children missing caregiver data were more likely to be white, Hispanic, or living with their biological mother; they were less likely to have a non-relative caregiver, a caregiver with high school education, or family income greater than $40,000. Although there were differences, sensitivity analyses restricted to children with complete caregiver information yielded qualitatively similar results (data not shown).

Discussion

In a large sample of children and adolescents with perinatal HIV exposure, including both those HIV-infected and uninfected, the prevalence of MHPs was greater than expected relative to surveys of MHPs in the general US youth population (Merikangas et al., 2010; US Surgeon General, 2001). These findings are consistent with earlier investigations in which higher than average rates of MHPs were identified among children with chronic illness (Gortmaker, Walker, Weitzman, & Sobol, 1990; Hysing, Elgen, Gillberg, Lie, & Lundervold, 2007; Wallander & Varni, 1998) and, more specifically, among children with HIV infection and those who were perinatally HIV-exposed but uninfected (Bauman et al., 2002, 2007; Gadow et al., 2010; Mellins et al., 2009). MHPs place youth at increased risk for poor psychological adaptation throughout childhood, adolescence and adulthood (Reef, Diamantopoulou, van Meurs, Verhulst, & van der Ende, 2009).

In our investigation, youth MHPs were significantly associated with aspects of the caregiving environment, including caregiver psychiatric disorder. Psychiatric disorders, such as depression, disproportionately affect women (Nolen-Hoeksema, 1987), and are common among women with HIV/AIDS (Kapetanovic et al., 2009; Morrison et al., 2002; Rotheram-Borus, Lightfoot, & Shen, 1999). As a result, HIV-exposed children, whether HIV-infected or uninfected, are at increased risk for negative outcomes, including emotional and behavioral problems, poor school and social adaptation, elevated rates of internalizing behaviors, and specific risk for depression (Beardslee, Versage, & Gladstone, 1998; Cummings & Davies, 1994; Cummings, Keller, & Davies, 2005; Leve, Kim, & Pears, 2005; Pilowsky et al., 2006; Rutter & Quinton, 1984).

Mechanisms that increase risk for child maladjustment associated with maternal psychiatric disorders include heritability, innate dysfunctional neuroregulatory processes, exposure to negative maternal behavior and affect, and the context of stressful lives that are common among women with psychiatric disorders (Goodman & Gotlib, 1999). In our study, the effect of caregiver psychiatric disorder on the presence of youth MHPs tended to be stronger among children living with biological mothers, who by definition were HIV+. Although genetic and environmental risks cannot be differentiated in this study, perhaps the stress of living with HIV interacts with genetic risk to increase vulnerability to psychopathology in some youth. Alternately, caregivers with psychopathology may overestimate behavior problems, react more negatively to their children’s behavior or are less able to exert a positive socializing influence on their children’s emotional or behavioral development (Renouf & Kovacs, 1994; Zeman, Cassano, Perry-Parrish, & Stegall, 2006).

Other findings highlight the importance of the caregiver-child relationship and the caregiving environment in the psychological adjustment of PHIV+ and PHEU youth, as discussed in earlier studies (Mellins et al., 2008; Murphy, Marelich, Herbeck, & Payne, 2009). Reduced caregiver limit-setting abilities, for example, were associated with increased youth MHP risk. In the absence of consistent behavioral guidelines and support from caregivers, children may have difficulty learning and meeting parental expectations, particularly when behavioral or emotional vulnerability is already present. Caregivers’ health-related functional limitations were also associated with higher MHP risk. Children and adolescents, particularly those with a chronic illness such as HIV infection, require ongoing and consistent caregiver support, yet caregivers’ ability to complete normal parenting tasks may be compromised when they themselves experience serious health problems, as suggested by Bauman et al. (2007). The family’s ability to access mental health care, when MHPs are present, may be jeopardized as well if caregivers’ health and activities are restricted.

In contrast to earlier reports, we found higher rates of MHPs among PHEU than PHIV+ youth. More than one-third of PHEU youth had MHPs, half of which were clinically significant problems. The risks associated with HIV exposure and living in a family affected by HIV have been described previously (Bauman et al., 2002, 2007; Rotheram-Borus, Lightfoot, & Shen, 1999). However, to our knowledge, this is one of few studies to report higher rates of MHPs in PHEU than PHIV+ youth. This is a concerning finding, given the growing numbers of PHEU children worldwide. Recent estimates suggest close to 9000 HIV+ women deliver annually in the US (Whitmore, Zhang, & Taylor, 2009), yet PHEU youth may not easily access the benefits of comprehensive medical and psychological care throughout childhood and adolescence, as do PHIV+ youth who are typically engaged in multidisciplinary medical care since diagnosis (Chernoff et al., 2009). It is reassuring, on the other hand, that the higher rates of MHPs among PHEU youth in the present study were not related to in utero exposure to ARVs, which remains the gold standard in preventing perinatal HIV transmission.

Among males, PHEU youth had significantly higher odds of exhibiting MHPs than did PHIV+ youth, while there were no differences by infection status among females. In addition, PHEU youth who identified as Black had almost three times the odds of MHPs, in contrast to earlier studies that demonstrated only small, statistically nonsignificant differences in prevalence of MHPs by race/ethnicity in the general population, especially if other risk factors, such as inner-city residence and poverty, were controlled (Costello, Messer, Reinherz, Cohen, & Bird, 1998). The pathways for increased MHP risk in PHEU children are multifactorial. Our findings suggest that differential associations between gender and race/ethnicity and MHPs for PHEU versus PHIV+ youth may be among factors involved, and thus warrant further investigation.

Several additional youth factors were associated with MHPs among PHIV+ and PHEU youth, including younger age and lower cognitive functioning. MHPs, such as those indicated by the BASC-2 BSI, may be present and recognized by caregivers during children’s earlier years but dissipate or change over time, as a function of improving self-regulatory processes or appropriate educational, psychological, or psychiatric intervention. The relationship between lower cognitive functioning and MHPs is well-described in the literature (Emerson & Hatton, 2007; Goodman, 1995; Rutter, Tizard, Yule, Graham, & Whitmore, 1976; Wallander, Dekker, & Koot, 2003). Such a relationship may be mediated by the role of cognitive status in determining children’s vulnerability or resilience in the presence of stressful life conditions (Luthar, 2003) or social disadvantage (Bradley & Corwyn, 2002), both of which are common among families affected by HIV. In addition, the biological bases or sequelae of cognitive disabilities may be associated with increased risk for psychopathology (Dykens, 2000). Future research should attempt to identify the relative impact and interaction of cognitive impairment, social and environmental risk, and biological factors in the development and chronicity of mental health problems in children affected by HIV.

This study is not without limitations. First, the cross-sectional design does not allow us to establish causality between child, caregiver or health factors and the presence of MHPs. Next, approximately 38% of youth had missing caregiver data with observed differences between children with completed versus missing caregiver assessments. However, in sensitivity analyses restricted to children with complete caregiver evaluations, the observed effect estimates remained substantially similar to our main analyses. Also, caregivers may have enrolled their PHEU children because of concerns about their children’s mental health, which could bias results. However, sites conducted extensive outreach and offered enrollment to PHEU children with whom they had a prior or current relationship, including siblings of HIV-infected children and PHEU children who participated in HIV screening during early childhood, living in communities demographically similar to those of HIV+ children. Even with such outreach, it remains possible that this US based cohort does not fully reflect the characteristics of all youth born to HIV+ mothers, limiting generalizability of findings to PHIV+ and PHEU youth living in the US, with access to medical care.

Nonetheless, the results of this investigation advance our understanding of the impact of HIV infection and perinatal HIV exposure, and highlight the dynamic interaction between youth and caregiver characteristics in families affected by HIV. The growing number of uninfected youth with perinatal HIV and ARV exposure provides a strong public health mandate to monitor the development of these children and routinely assess their mental health needs. Appropriate diagnosis and intervention are crucial since untreated MHPs often lead to co-morbidities, including school failure, juvenile crime, substance use, HIV infection, unintentional injuries, violence, and increased mortality, including suicide. Caregivers with psychiatric disorders should be referred for treatment, not only to reduce suffering, but also because successful caregiver intervention will prevent or diminish psychological risk among their children (McCarty, McMahon & Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group, 2003). Multi-level, family-focused and evidence-based psychological and/or psychiatric intervention services that begin early in life and address both youth and caregiver competencies and needs may be most efficacious and cost-effective (McEwen, 2008; Sanders & McFarland 2000). Collaboration with educators and schools is also essential so that children receive the educational and social support that foster development of competency and adaptation in the school and home environments.

While early diagnosis and treatment of MHPs are necessary, prevention of MHPs in families affected by HIV is also an important goal. Health care providers, psychologists, psychiatrists and social workers are positioned to lead efforts that will ultimately foster resilience and reduce intergenerational transmission of psychopathology in families affected by HIV, through culturally sensitive, individualized and targeted mentoring, parenting support, and peer and group support. A number of family-based interventions have been developed for children infected and affected by HIV and may be appropriate models that could be incorporated into health care programs that serve HIV affected adults and youth (McKay et al., 2006; Pequegnat & Szapocznid, 2000). Future prospective longitudinal investigations are necessary to elucidate causal factors associated with resilience and the onset and chronicity of MHPs in youth with perinatal HIV-exposure and HIV-infection.

Acknowledgements

We thank the children and families for their participation in the PHACS Adolescent Master Protocol (AMP), and the individuals and institutions involved in the conduct of PHACS AMP. The study was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development with co-funding from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, the National Institute on Drug Abuse, the National Institute of Mental Health, National Institute of Deafness and Other Communication Disorders, the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, and the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, through cooperative agreements with the Harvard University School of Public Health (U01 HD052102-04) (Principal Investigator: George Seage; Project Director: Julie Alperen) and the Tulane University School of Medicine (U01 HD052104-01) (Principal Investigator: Russell Van Dyke; Co-Principal Investigator: Kenneth Rich; Project Director: Patrick Davis). Data management services were provided by Frontier Science and Technology Research Foundation (PI: Suzanne Siminski), and regulatory services and logistical support were provided by Westat, Inc (PI: Mercy Swatson).

The following institutions, clinical site investigators and staff participated in conducting PHACS AMP in 2009, in alphabetical order: Baylor College of Medicine: William Shearer, Norma Cooper; Bronx Lebanon Hospital Center: Murli Purswani, Mahboobullah Baig; Children’s Diagnostic & Treatment Center: Ana Puga, Sandra Navarro; Children’s Hospital, Boston: Sandra Burchett, Nancy Karthas; Children’s Memorial Hospital: Ram Yogev, Eric Cagwin; Jacobi Medical Center: Andrew Wiznia, Marlene Burey; St. Christopher’s Hospital for Children: Janet Chen, Elizabeth Gobs; St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital: Katherine Knapp, Kim Allison; San Juan Hospital/Department of Pediatrics: Midnela Acevedo-Flores, Heida Rios; Tulane University Health Sciences Center: Margarita Silio, Cheryl Borne; University of California, San Diego: Stephen Spector, Kim Norris; University of Colorado Denver Health Sciences Center: Elizabeth McFarland, Emily Barr; University of Maryland, Baltimore: Douglas Watson, Nicole Messenger; University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey: Arry Dieudonne, Linda Bettica; University of Miami: Gwendolyn Scott, Lisa Himic, Elizabeth Willen. The conclusions and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the National Insitutes of Health or US Department of Health and Human Services.

Footnotes

Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions

This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden.

Publisher's Disclaimer: The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae, and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand, or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material.

This work was authored as part of the contributor’s official duties as an employee of the United States Government in the United States Department of Health and Human Services and is therefore a work of the United States Government. In accordance with 17 U.S.C. 105, no copyright protection is available for such works under U.S. law.

References

- Achenbach TM, Howell CT, Quay HC, Conners CK. National survey of competencies and problems among 4–16 year olds: Parent’s reports for normative and clinical samples. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1991;56(3):1–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, McConaughy SH, Howell CT. Child/adolescent behavioral and emotional problems: Implications of cross-informant correlations for situational specificity. Psychological Bulletin. 1987;101(2):213–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aidala A, Havens J, Mellins CA, Dodds S, Wetten K, Martin D, Ko P. Development and validation of the Client Diagnostic Questionnaire (CDQ): A mental health screening tool for use in HIV/AIDS service settings. Psychological Health Medicine. 2004;9:362–380. [Google Scholar]

- Bauman LJ, Camacho S, Silver EJ, Hudis J, Draimin B. Behavioral problems in school-aged children of mothers with HIV/AIDS. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2002;7:39–54. [Google Scholar]

- Bauman LJ, Silver EJ, Draimin BH, Hudis J. Children of mothers with HIV/AIDS: Unmet needs for mental health services. Pediatrics. 2007;120(5):e1141–e1147. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beardslee WR, Versage EM, Gladstone TRG. Children of affectively ill parents: A review of the past ten years. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1998;37:1134–1141. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199811000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley RH, Corwyn RF. Socioeconomic status and child development. Annual Review of Psychology. 2002;53:371–399. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brouwers P, De Carli C, Civitello L, Moss H, Wolters P, Pizzo P. Correlations between computed tomographic brain scan abnormalities and neuropsychological function in children with symptomatic human immunodeficiency virus disease. Archives of Neurology. 1995;52(1):39–44. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1995.00540250043011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown LK, Lourie KJ, Pao M. Children and adolescents living with HIV and AIDS: A review. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry. 2000;41(1):81–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Disease Control. 1994 Revised classification system for human immunodeficiency virus infection in children less than 13 years of age. MMWR. 1994;Vol. 43(No. RR-12) [Google Scholar]

- Chernoff M, Nachman S, Williams P, Brouwers P, Heston J, Hodge J IMPAACT P1055 Study Team. Mental health treatment patterns in perinatally HIV-infected youth and controls. Pediatrics. 2009;124:627–636. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello EJ, Messer SC, Reinherz HZ, Cohen P, Bird HR. The prevalence of serious emotional disturbance: A re-analysis of community studies. Journal of Child Family Studies. 1998;7:411–432. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Davies PT. Maternal depression and child development. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines. 1994;35:73–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1994.tb01133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Keller PS, Davies PT. Towards a family process model of maternal and paternal depressive symptoms: Exploring multiple relations with child and family functioning. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2005;46:479–489. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00368.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donenberg GR, Pao M. Youths and HIV/AIDS: Psychiatry’s role in a changing epidemic. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2005;44(8):728–747. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000166381.68392.02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dykens EM. Psychopathology in children with intellectual disability. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2000;41:407–417. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emerson E, Hatton C. Mental health of children and adolescents with intellectual disabilities in Britain. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;191:493–499. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.038729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadow KG, Chernoff M, Williams PL, Brouwers P, Morse E, Heston J, Nachman S. Co-occurring psychiatric symptoms in children perinatally infected with HIV and peer comparison sample. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 2010;31:116–128. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e3181cdaa20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerard AB. Parent-Child Relationship Inventory Manual. Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman R. The relationship between normal variation in IQ and common childhood psychopathology: A clinical study. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1995;4:187–196. doi: 10.1007/BF01980457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman SJ, Gotlib IH. Risk for psychopathology in the children of depressed mothers: A developmental model for understanding mechanisms of transmission. Psychological Review. 1999;106:458–490. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.106.3.458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gortmaker SL, Walker DK, Weitzman M, Sobol AM. Chronic conditions, socioeconomic risks and behavioral problems in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 1990;85(3):267–276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havens JF, Mellins CA. Psychiatric aspects of HIV/AIDS in childhood and adolescence. In: Rutter M, Bishop D, Pine D, Scott S, Stevenson J, Taylor E, Thapar A, editors. Rutter’s child and adolescent psychiatry. 5th ed. Oxford: Blackwell; 2008. pp. 945–955. [Google Scholar]

- Hysing M, Elgen I, Gillberg C, Lie SA, Lundervold AJ. Chronic physical illness and mental health in children. Results from a large-scale population study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2007;48(8):785–792. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01755.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones MP. Indicator and stratification methods for missing explanatory variables in multiple linear regression. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1996;91:222–230. [Google Scholar]

- Kapetanovic S, Christensen S, Karim R, Lin F, Mack WJ, Operskalski E, Kovacs A. Correlates of perinatal depression in HIV-infected women. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2009;23(2):101–108. doi: 10.1089/apc.2008.0125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leve LD, Kim HK, Pears KC. Childhood temperament and family environment as predictors of internalizing and externalizing trajectories from ages 5 to 17. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2005;33:505–520. doi: 10.1007/s10802-005-6734-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luthar SS, editor. Resilience and vulnerability: Adaptation in the context of childhood adversities. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- McCarty CA, McMahon RJ Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group. Mediators of the relation between maternal depressive symptoms and child internalizing and disruptive behavior disorders. Journal of Family Psychology. 2003;17(4):545–556. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.17.4.545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen BS. Understanding the potency of stressful early life experiences in brain and body function. Metabolism Clinical and Experimental. 2008;57(Suppl. 2):S11–S15. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2008.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay M, Block M, Mellins CA, Traube D, Brackis-Cottt E, Minott D, Abrams EJ. Adapting a family-based HIV prevention program for HIV-infected preadolescents and their families: Youth, families and health care providers coming together to address complex needs. Social Work in Mental Health. 2006;5:349–372. doi: 10.1300/J200v05n03_06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mekmullica J, Brouwers P, Charurat M, Paul M, Shearer W, Mendez H, McIntosh K. Early immunological predictors of neurodevelopmental outcomes in HIV-infected children. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2009;48(3):338–346. doi: 10.1086/595885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellins CA, Brackis-Cott E, Dolezal C, Leu CS, Valentin C, Meyer-Bahlburg HFL. Mental health of early adolescents from high-risk neighborhoods: The role of maternal HIV and other contextual, self-regulation, and family factors. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2008;33(10):1065–1075. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsn004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellins CA, Brackis-Cott E, Leu C, Elkington KS, Dolezal C, Wiznia A, Abrams EJ. Rates and types of psychiatric disorders in perinatally human immunodeficiency virus-infected youth and seroreverters. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2009;50(9):1131–1138. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02069.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellins CA, Smith R, O’Driscoll P, Magder L, Brouwers P, Chase C, Matzen E. High rates of behavioral problems in perinatally HIV-infected children are not linked to HIV disease. Pediatrics. 2003;111(2):384–393. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.2.384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas KR, He J, Brody D, Fisher PW, Bourdon K, Koretz DS. Prevalence and treatment of mental disorders among US children in the 2001–2004 NHANES. Pediatrics. 2010;125(1):75–81. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison MF, Petitto JM, Ten Have T, Gettes DR, Chiappini MS, Weber AL, Evans DL. Depressive and anxiety disorders in women with HIV infection. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;159:789–796. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.5.789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy DA, Marelich WD, Herbeck DM, Payne DL. Family routines and parental monitoring as protective factors among early and middle adolescents affected by maternal HIV/AIDS. Child Development. 2009;80:1676–1691. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01361.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S. Sex differences in unipolar depression: Evidence and theory. Psychological Bulletin. 1987;101:259–282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nozyce M, Lee S, Wiznia A, Nachman S, Mofenson L, Smith M, Pelton S. A behavioral and cognitive profile of clinically stable HIV infected children. Pediatrics. 2006;117(3):763–770. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papola P, Alvarez M, Cohen HJ. Developmental and service needs of school-age children with human immunodeficiency virus infection: A descriptive study. Pediatrics. 1994;6:914–918. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pequegnat W, Szapocznid J, editors. Inside families: The role of families in preventing and adapting to HIV/AIDS. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Pilowsky DJ, Wickramaratne PJ, Rush AJ, Hughes CW, Garber J, Malloy E, Weissman MM. Children of currently depressed mothers: A STAR*D ancillary study. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2006;67(1):126–136. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n0119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reef J, Diamantopoulou S, van Meurs I, Verhulst F, van der Ende J. Child to adult continuities of psychopathology: A 24-year follow-up. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2009;120:230–238. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2009.01422.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renouf AG, Kovacs MJ. Concordance between mother’s reports and children’s self-reports of depressive symptoms: A longitudinal study. American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1994;33:208–216. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199402000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds CR, Kamphaus RW. Behavior Assessment System for Children. 2nd ed. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Rotheram-Borus M, Lightfoot M, Shen H. Levels of emotional distress among parents living with AIDS and their adolescent children. AIDS and Behavior. 1999;3:367–372. [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M, Quinton D. Parental psychiatric disorder: Effects on children. Psychological Medicine. 1984;14:853–880. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700019838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M, Tizard J, Yule W, Graham P, Whitmore K. Isle of Wight studies 1964–1974. Psychological Medicine. 1976;6:313–332. doi: 10.1017/s003329170001388x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders MR, McFarland M. Treatment of depressed mothers with disruptive children: A controlled evaluation of cognitive behavioral family intervention. Behavior Therapy. 2000;31:89–112. [Google Scholar]

- Sharko AM. DSM psychiatric disorders in the context of pediatric AIDS. AIDS Care. 2006;18(5):441–445. doi: 10.1080/09540120500213487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: The PHQ primary care study. Primary care evaluation of mental disorders. Patient health questionnaire. Journal of American Medical Association. 1999;282(18):1737–1744. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.18.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steele RG, Nelson TD, Cole BP. Psychosocial functioning in children with AIDS and HIV infection: Review of the literature from a socioecological framework. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 2007;28(1):58–69. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e31803084c6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallander JL, Varni JW. Effects of pediatric chronic physical disorders on child and family adjustment. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1998;39:29–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallander JL, Dekker MC, Koot HM. Psychopathology in children and adolescents with intellectual disability: Measurement, prevalence, course, and risk. International Review of Research in Mental Retardation. 2003;26:93–134. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence. San Antonio, TX: Harcourt Assessment; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Whitmore S, Zhang X, Taylor A. Estimated number of births to HIV–women in the US, 2006. Poster session presented at the 16th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; 2009, February; Montreal, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- US Surgeon General. Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Washington, DC: Department of Health and Human Services; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Zeman J, Cassano M, Perry-Parrish C, Stegall S. Emotion regulation in children and adolescents. Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 2006;27(2):155–168. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200604000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]