Abstract

Objective

This article describes design elements of the Multifaceted Depression and Diabetes Program (MDDP) randomized clinical trial. The MDDP trial hypothesizes that a socioculturally adapted collaborative care depression management intervention will reduce depressive symptoms and improve patient adherence to diabetes self-care regimens, glycemic control, and quality-of-life. In addition, baseline data of 387 low-income, 96% Hispanic, enrolled patients with major depression and diabetes are examined to identify study population characteristics consistent with trial design adaptations.

Methods

The PHQ-9 depression scale was used to identify patients meeting criteria for major depressive disorder (1 cardinal depression symptom + a PHQ-9 score of ≥ 10) from two community safety net clinics. Design elements included sociocultural adaptations in recruitment and efforts to reduce attrition and collaborative depression care management.

Results

Of 1,803 diabetes patients screened, 30.2% met criteria for major depressive disorder. Of 387 patients enrolled in the clinical trial, 98% had Type 2 diabetes, and 83% had glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) levels ≥ 7%. Study recruitment rates and baseline data analyses identified socioeconomic and clinical factors that support trial design and intervention adaptations. Depression severity was significantly associated with diabetes complications, medical comorbidity, greater anxiety, dysthymia, financial worries, social stress, and poorer quality-of-life.

Conclusion

Low-income Hispanic patients with diabetes experience high prevalence of depressive disorder and depression severity is associated with socioeconomic stressors and clinical severity. Improving depression care management among Hispanic patients in public sector clinics should include intervention components that address self-care of diabetes and socioeconomic stressors.

Keywords: depression, diabetes, randomized clinical trial, collaborative care, low-income

INTRODUCTION

Among U.S. Hispanics, the prevalence of diabetes is nearly twice that among non-Hispanic whites, and diabetes is the fifth leading cause of death [1, 2]. Glycemic control is worse [3], and complications are higher than for any other ethnic group, except for Native Americans [4, 5]. Poor diabetes outcomes in Hispanics are explained, in part, by inadequate medical and self-care, as well as sociocultural factors [6, 7]. Prevalence estimates indicate that diabetes is associated with a twofold higher risk of comorbid depression compared to the general population, with rates among Hispanics as high as 33% [8–10].

Comorbid depression and diabetes may significantly worsen the course of both disorders, leading to increased socioeconomic stress, reduced functioning and quality of life, and higher complication and mortality rates [11–18]. Total health care expenditures among patients with diabetes and depression are up to 4.5 times higher than for non-depressed patients [19–21]. Depression may worsen diabetes outcomes via behavioral and biochemical mechanisms [22–24], and may decrease patients’ adherence to self-care regimens such as diet, exercise, checking blood glucose, and medication adherence [25–27]. Patients with diabetes and comorbid depression have been shown to have decreased glucose tolerance and increased insulin resistance, possibly mediated by alterations in catecholamine and serotonin pathways [28, 29]. In some but not all trials, glucose control is shown to improve with effective depression treatment [30, 31]. Greater risk of cardiovascular illness, functional disability, mortality, and health service use is found among depressed Hispanics with diabetes [22]. Among diabetic patients, depression can be persistent and severe [13, 26, 30]. Unfortunately, Hispanics are less likely to receive guideline congruent depression care [23, 24], and are at higher risk of discontinuing antidepressants during the first 30 days of treatment because of side effects or socioeconomic barriers [32].

This article: a) describes design elements of the Multifaceted Depression and Diabetes Program (MDDP) randomized clinical trial with a focus on sociocultural adaptations in recruitment, attrition management, and collaborative depression care management; and b) examines baseline data from 387 low-income, 96% Hispanic patients with major depression and diabetes to identify study population and care system characteristics that support the study design adaptations. The MDDP trial hypothesizes that reducing depressive symptoms will improve patient adherence to diabetes self-care regimens, glycemic control, and quality of life. The trial is designed to examine potential differences in study outcomes by clinic site. Clinic administrative leadership and clinical staff were engaged in designing aspects of trial implementation that best fit the needs of clinic organization and provider preferences.

METHODS

Study Site, Sample Recruitment, and Depression Screening

The study was approved by the University of Southern California–Health Sciences Institutional Review Board and conducted at two Los Angeles County Department of Health Services safety net clinics. One clinic offers a diabetes management program, with diabetes nurse educators providing care coordination, remote monitoring, telephonic communication, and patient self-management education and empowerment. Via clinic chart review, trained bilingual study recruiters identified diabetes patients. Patients provide brief verbal consent to be screened for depressive symptoms and eligible patients provide written informed consent. Randomization is determined via computer generated number from a uniform distribution (Enhanced Usual Care (EUC) ≤ 0.5; Intervention > 0.5), printed on a sheet of paper, and sealed in an envelope from which patients select one of five after baseline interview.

EUC patients receive standard clinic care and are given a patient/family focused depression educational pamphlet (Spanish or English) and a community, financial, social services, transportation, and child care resource list. EUC primary care physicians (PCPs) may prescribe antidepressants (AM) or refer patients for mental health care. Patients may seek any usually available mental health treatment. The treating PCP was informed of patients’ study participation. Clinic PCPs and nursing staff attended a depression treatment didactic session by the study psychiatrist at the beginning of the study and a refresher midway.

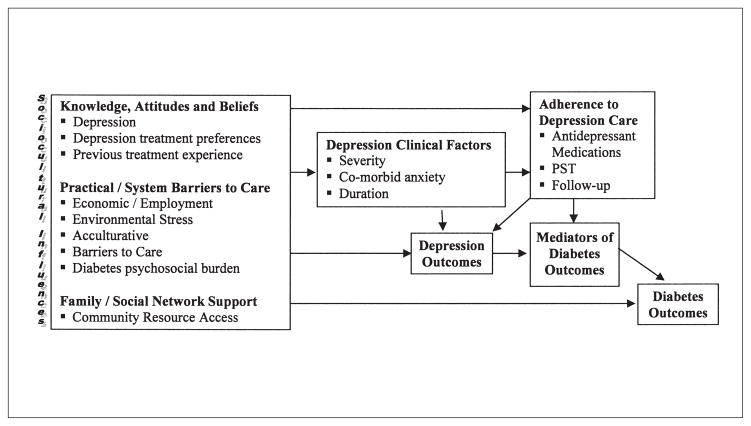

Sociocultural Framework

A guiding conceptual framework (Figure 1) assumed that patients’ health beliefs and treatment behaviors are culturally informed (with significant variation in beliefs within and across cultural groups and that these beliefs are key antecedents of health behaviors), and that culturally patterned behavior is not independent of powerful structural constraints and social contextual factors, including cost and provider concerns relevant to safety net clinics, patient literacy, and access to supportive resources. Thus, adaptations to the study design and intervention were made to accommodate needs of the trial population and to adapt to the public sector organizational practice context (Table 1). These adaptations are aimed to:

Figure 1.

Sociocultural factors and barriers in depression care management for low-income Hispanics with diabetes.

Table 1.

Study Design and Intervention Adaptations

| Recruitment and Attrition Adaptations |

|

| Provider and System Level Adaptations |

|

| Patient Level Adaptations |

|

maximize recruitment and minimize attrition;

enhance patient depression treatment engagement and adherence;

reduce individual, provider, and system barriers to depression and diabetes care via the provision of system and community resource navigation;

integrate depression and diabetes care; and

provide culturally and linguistically competent depression care.

Where feasible, data collection measures address elements presented in Figure 1. With respect to knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs regarding depression, we conducted a qualitative study of 19 patients that included focus groups and individual structured interviews [33].

The Patient Health Questionnaire depression scale (PHQ-9) was used to screen patients because it provides both a dichotomous diagnosis of major depression and a continuous severity score [34], measures a common concept of depression across racial and ethnic groups [35], and believed to be practically feasible and sustainable in real world community clinics. The PHQ-9 is a reliable depression screening tool in primary care with a demonstrated ability to identify clinical depression, make accurate diagnoses of major depressive disorder, track severity of depression over time [36–41], and monitor patient response to therapy in-person or via telephone [42]. The PHQ-9 scores the nine DSM-IV criteria as “0” (not at all) to “3” (nearly every day), with possible scores ranging from 0 to 27, with cut points of 5, 10, 15, and 20 representing the thresholds for minor, mild, moderate, and severe depressive disorder. If patients meet criteria for major depressive disorder (based on a score of ≥ 2 for one of the two cardinal depression symptoms and a PHQ-9 score of ≥ 10), a screening protocol is administered to exclude patients with current suicidal ideation, a score of 8 or greater on the AUDIT alcohol assessment [43], and recent use of lithium or antipsychotic medication.

Data Collection

The 20-item SCL-90 depression scale [44] is used as a reliable and valid measure of distress in medical populations shown to be sensitive to change in primary care studies (Cronbach alpha (α) = 0.91) [45, 46]. Two standard questions from the SCID are used to assess dysthymia [47]. The Summary of Diabetes Self-Care Activities Questionnaire was used to measure self-reported adherence (α = 0.72) [48]. Diabetes symptoms are assessed via self-report using the Whitty 9-item questionnaire, demonstrated to measure change over time with effective diabetes treatment (α = 0.79) [49]. Self-reported diabetes complications, comorbid illness, and socioeconomic stress are also assessed. Chronic Pain defined as pain present most of the time for 6 or more months over past year is assessed using a measure developed for diabetes patients [50]. Anxiety is assessed using a 6-item BSI anxiety module from the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI; α = 0.85) [51]. Socioeconomic stress is assessed using 12 items from the Hispanic Stress Inventory [52] (unemployment problems, marital/family conflicts, legal problems, caregiving problems, worries about community violence) plus questions regarding specific financial stress including difficulty in paying bills.

Glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) results (last test prior to enrollment) are abstracted from medical charts. The MOS Short-Form Health Survey (SF-12) [53] is used to assess functioning. Disability is assessed using the Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS) adapted for depression trials [54]. Scores are derived as an average of a 10-point Likert Scale (10 indicating inability to carry out work and social roles; α = 0.88).

Patient Treatment Choice and Depression Education

Based on previous studies suggesting that the low-income, predominantly Hispanic population is likely to initially prefer psychotherapy [33, 55–57], we elected to give patients the choice of first-line treatment: Problem Solving Therapy (PST) [58] alone, AM alone, or both PST and AM. All patients are educated about the different treatment options. The initial Diabetes Depression Clinical Specialist (DDCS) visit(s) includes: a semi-structured psychiatric/psychosocial assessment; patient depression, PST, and AM education; initial treatment choice consideration; patient navigation assistance; and includes family members at patient request. Subsequent visits provide PST and/or telephone AM monitoring.

Collaborative Depression Care Management

MDDP care management adapted evidence-based components of the collaborative care model [30, 31] including:

DDCS (bilingual master’s degreed social workers) depression education and general psychosocial assessment, bi-monthly PST and AM monitoring over 4 months, and patient navigator (PN) supervision;

study psychiatrist weekly clinical supervision of the DDCS that included DDCS review of patient’s depression status (using the PHQ-9), diabetes, and other comorbid clinical status, all current medications, and patient treatment preference;

study psychiatrist recommended AM and dosage and additional psycho-tropic medications such as an anti-anxiety agent or sedative-hypnotic that was communicated by the DDCS to the PCP; and

psychiatrist availability to the DDCS and PCP via pager.

MDDP applies a written personalized structured algorithm for stepped care management (based on the IMPACT algorithm for depression in primary care) [31] to ensure patients receive depression treatment consistent with their clinical presentations and responses over time. For example, for a patient who has not had full response to treatment by 4–8 weeks, Step 2 of the algorithm is employed. The patient on AM may require medication change or augmentation or adding PST. Patients on PST alone are again educated about the option of AM and based on discussion between the study psychiatrist and the DDCS, an AM is recommended by the psychiatrist and communicated to the PCP. The patient, who has not had a full response by 8–12 weeks, proceeds to Step 3. During the weekly DDCS/psychiatrist meeting, the psychiatrist recommends either another type of AM, a combination of PST and AM if not tried at Step 2, or referral for treatment in a specialty mental health setting, facilitated by the DDCS. Treatment at this step depends on clinical status, available community resources, and patients’ willingness to accept recommended care.

Psychotherapy

PST was chosen because it has been effective in diabetes patients [40, 41] and in studies with Hispanic low-income cancer patients [57, 59, 60]. PST’s brief psycho-educational characteristics make it feasible to provide and acceptable to patients with less education. PST uses the behavioral activation components of CBT, but with less emphasis on changing cognition and greater emphasis on patient assessment of personal contextual problems and skill-building to enhance self-management skills. PST sessions ranging from 6–12 weeks are highly structured. The perception of counselor as teacher or coach in PST is compatible with preferences of Hispanic patients, particularly when therapists are sensitive to the desire for warmth and sensitivity to family relationships. The saliency of social and environmental stressors in Hispanics’ explanatory models of depression and the congruency of psychotherapy with the cultural value of desahogarse (unburdening oneself) also makes PST an appropriate treatment option for this underserved population [33]. PST implementation was specifically adapted in areas suggested by Bernal and colleagues [61], such as use of language and idioms in educational and homework materials, utilizing bilingual and bicultural staff, use of cultural common sayings (dichos) and idiomatic language in treatment sessions, recognition and knowledge of cultural values (e.g., familism, respect), adaptation of treatment concepts to be sensitive and consistent with culture and patient context, sensitivity of intervention staff to adaptive values of patient culture such as spirituality, use of patient preferences and integration of diabetes self-management in the problem-solving focus, consideration of patient’s health status in the context of socioeconomic factors, and ongoing assessment of need for PN services, including facilitating patient/PCP communication.

Acute Treatment Follow-Up

After completion of the acute phase of treatment, the patient is followed with a program to maximize maintenance treatment and prevent relapse. This includes DDCS telephone maintenance/relapse prevention and outcomes monitoring [62], community services navigation by the DDCS or PN under DDCS direction, and a maintenance open-ended PST support group in both English and Spanish. The DDCS contacts the patient monthly via telephone up to 12 months after treatment initiation to monitor depressive symptoms, provide behavioral activation support for engaging in pleasant activities and motivational support for ongoing use of PST skills and medication adherence, and invites patients to attend an open-ended PST support group. If patients report symptom relapse, the DDCS will present to the psychiatrist during the weekly supervision call. If indicated, additional PST sessions are provided and/or AM adjusted by the PCP as recommended by the psychiatrist.

DDCS Training

The DDCS received an initial didactic orientation to the needs and psychiatric and general psychosocial evaluation (such as domestic violence and family economic and care-giving problems) of low-income patients with diabetes, biologic aspects of depression, and AM use for diabetic patients from the study psychiatrist and principal investigator. The DDCS received an initial 2 weeks of formal PST training including: self-study of the PST and MDDP manuals, video, and in-person didactic sessions; observation of a skilled therapist doing an initial evaluation and two PST sessions with a diabetes patient; and treatment of 3–5 patients under close supervision by a therapist experienced in PST. Audio-taping of treatment sessions was conducted on five patients; these were reviewed by a PST expert using a Likert scale of 1 to 3 (low to high adherence) on 12 session-specific items. If there is evidence of inadequacy, further consultation and supervision is provided. Cultural competency training was provided for both the DDCS and the PN via a self-study manual.

Patient Navigators

PNs worked with patients under the direction of the DDCS to assist in referrals to community resources (e.g., housing, social services), locate patients who had missed clinic appointments, and facilitate clinic system and patient communication about appointments and maintain up-to-date community resource information. PN training included cultural competency, meeting of clinic staff and learning about clinic management and processes, and community resource and eligibility requirements.

RESULTS

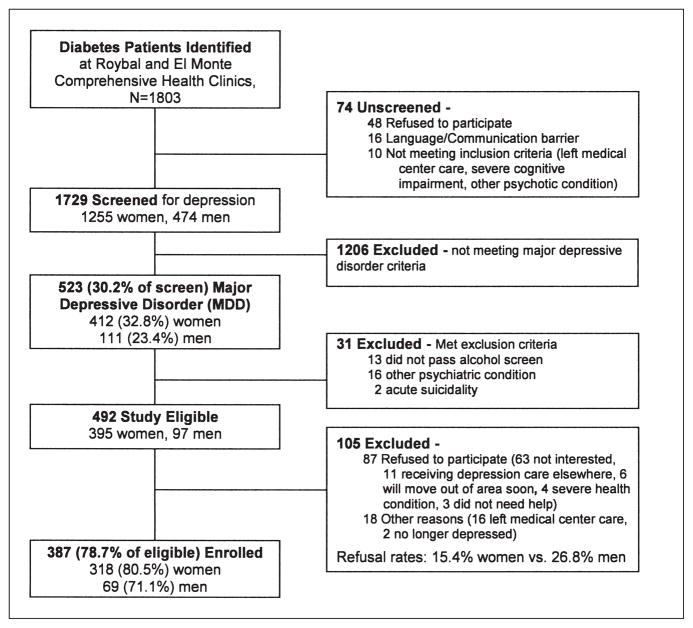

At recruitment completion (August 2005–July 2007), of 1,803 diabetes patients, 1,729 (95.8%) were successfully screened including 1,255 (72.6%) females and 474 (27.4%) males (Figure 2). Of patients screened, 412 women and 111 men met criteria for major depressive disorder (32.8% vs 23.4%, p < 0.001). Table 2 presents patient characteristics. In Table 3, clinical site differences were observed, in which significantly more patients at Roybal were taking insulin, had HbA1c levels ≤ 7.0%, reported taking psychotropic medications or receiving counseling, and had lower PHQ-9 scores. Table 4 includes results from multiple Logistic Regressions comparing odds of having moderate to severe major depression across socioeconomic, clinical, and functional characteristics with adjustment for study site, birth place, language use, age, and gender. Major depression severity was significantly associated with number of diabetes complications, medical comorbidity, greater anxiety, dysthymia, worry about medication cost and financial situation, social stress, and poorer quality of life indices.

Figure 2.

MDDP recruitment flowchart.

Table 2.

Demographic Characteristics (N = 387)

| All n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Female | 318 (82%) |

| Male | 69 (18%) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Non-Hispanic | 15 (4%) |

| Hispanic | 372 (96%) |

| Age group | |

| <=54 yrs | 184 (48%) |

| 55 yrs+ | 203 (52%) |

| Birth place | |

| Foreign born | 352 (91%) |

| U.S. born | 35 (9%) |

| Years in U.S. | |

| <10 yrs | 36 (9%) |

| 10 yrs+ | 350 (91%) |

| Language use | |

| Not English | 327 (85%) |

| English | 60 (16%) |

| Education | |

| <High school | 317 (82% |

| High school+ | 70 (18%) |

| Employment status | |

| Unemployed | 303 (78%) |

| Employed | 84 (22%) |

| Marital status | |

| Unmarried | 196 (51%) |

| Married | 191 (49%) |

| Insurance coverage | |

| Medi-Cal/Medicare | 70 (18%) |

| County care program | 231 (60%) |

| Other | 4 (1%) |

| None | 82 (21%) |

Table 3.

Site Baseline Comparison Data

| ALL N = 387 n (%) |

Roybal n = 219 n (%) |

El Monte n = 168 n (%) |

Bivariate analysis p |

Multivariate analysis p |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical Characteristics | |||||

| Diabetes treatment | |||||

| Oral medication | 268 (69.3) | 146 (66.7) | 122 (72.6) | ||

| Insulin | 54 (14.0) | 22 (10.0) | 32 (19.0) | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Insulin plus oral medication | 53 (13.7) | 45 (20.5) | 8 (4.8) | 0.56 | |

| Diet alone or none | 12 (3.1) | 6 (2.7) | 6 (3.6) | 0.76 | |

| Diabetes complications | |||||

| 0 | 65 (16.8) | 24 (11.0) | 41 (24.4) | ||

| 1 | 160 (41.3) | 88 (40.2) | 72 (42.9) | 0.49 | |

| 2 | 106 (27.4) | 72 (32.9) | 34 (20.2) | 0.33 | |

| ≥3 | 56 (14.5) | 35 (16.0) | 21 (12.5) | <0.01 | |

| HbA1c ≥ 7% | 310 (82.9) | 168 (79.2) | 142 (87.7) | 0.03 | |

| Moderate/severe depression (PHQ-9 ≥ 15) | 196 (50.6) | 99 (45.2) | 97 (57.7) | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Taking psychotropic medicationa | 61 (15.8) | 42 (19.2) | 19 (11.3) | 0.04 | |

| Depression/anxiety counselingb | 49 (12.7) | 42 (19.2) | 7 (4.2) | <0.0001 | |

| Comorbid gastrointestinal disease | 54 (14.0) | 46 (21.0) | 8 (4.8) | <0.0001 | 0.03 |

| Comorbid eye disease | 59 (15.2) | 47 (21.5) | 12 (7.1) | <0.001 | |

| Comorbid arthritis | 140 (36.2) | 89 (40.6) | 51 (30.4) | 0.04 | |

| Chronic pain | 126 (32.6) | 85 (38.8) | 41 (24.4) | <0.01 | |

| Taking pain medication | 103 (26.6) | 69 (31.5) | 34 (20.2) | 0.01 | |

| Financial Stress | |||||

| No money left over at the end of month | 302 (78.0) | 202 (92.2) | 100 (59.5) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Very worried about current financial situation | 180 (46.5) | 122 (55.7) | 58 (34.5) | <0.0001 | |

| Cost concerns—hospitalization | 144 (37.2) | 120 (54.8) | 24 (14.3) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Financial situation is getting worse | 142 (36.7) | 98 (44.7) | 44 (26.2) | <0.001 | |

| Cost concerns—medication | 95 (24.5) | 66 (30.1) | 29 (17.3) | <0.01 | |

| Inability to get all prescribed medication | 37 (9.6) | 28 (12.8) | 9 (5.4) | 0.01 | |

| Have problems getting to the clinic | 83 (21.4) | 58 (26.5) | 25 (14.9) | 0.01 | |

| Social Stress Inventory | |||||

| Experiencing at least 1 or 12 stressorsc | 343 (88.6) | 207 (94.5) | 136 (81.0) | <0.0001 | |

55 patients taking SSRIs, 4 taking TCAs, 1 taking Benzodiazepine

Receiving from a doctor, social worker, or psychologist, some of whom were also among those taking psychotropic medication.

Work, unemployment, financial problems, marital/family conflicts, child/caregiving problems, cultural conflicts, legal or immigration problems, serious illness or death of family member, community violence or crime.

Table 4.

Multiple Logistic Regression Models

| Risk factors for moderate/severe major depression (PHQ-9 score 15 or more) | OR | 95% CI | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical Variables | |||

| Diabetes symptoms (range 1–5) | 2.48 | (1.79–3.43) | <.0001 |

| Diabetes complications | |||

| 1 vs. 0 | 1.78 | (0.97–3.26) | 0.06 |

| 2 vs. 0 | 1.67 | (0.86–3.25) | 0.13 |

| 3+ vs. 0 | 3.34 | (1.51–7.42) | 0.003 |

| Linear Trend test | 1.37 | (1.08–1.74) | 0.01 |

| Diabetes Self-Care Activities (mean range 0–7) | 0.97 | (0.84–1.12) | 0.67 |

| Comorbid medical illness (yes vs. no)a | 2.02 | (1.04–3.96) | 0.04 |

| Depression symptoms (SCL-20, range 0–4) | 3.70 | (2.55–5.38) | <.0001 |

| Dysthymia (yes vs. no) | 1.72 | (1.12–2.62) | 0.01 |

| Anxiety | |||

| Anxiety score (BSI, range 0–24) | 2.78 | (0.95–8.08) | 0.06 |

| Severe anxiety (BSI >= 14) | 1.13 | (1.07–1.19) | <.0001 |

| Chronic pain (yes vs. no) | 2.16 | 1.35–3.46) | 0.0013 |

| Financial Stress | |||

| Financial situation is getting worse | 2.68 | (1.68–4.26) | <.0001 |

| Very worried about current financial situation | 2.11 | (1.36–3.27) | <0.001 |

| No hope that financial situation will get better soon | 1.86 | (1.12–3.12) | 0.02 |

| Cost concerns—medication | 1.96 | (1.2 –3.22) | <0.01 |

| Social Stress Inventory | |||

| Experiencing at least 1 of 12 stressorsb | 3.12 | (1.53–6.36) | <0.01 |

| Functional Status/Quality of Life | |||

| SF-12 Summary Measures (general population mean = 50, higher = better) | |||

| MCS (Mental component score) | 0.94 | (0.91–0.97) | <.0001 |

| PCS (Physical component score) | 0.93 | (0.91–0.96) | <.0001 |

| Sheehan Disability Scale (scale 0–10) | 1.22 | (1.12–1.32) | <.0001 |

Study site, birth place, years in the U.S. language use, age, and gender were controlled in the models.

Hypertension, arthritis, eye disease, gastrointestinal disease, kidney disease, heart disease, cancer, urinary tract or prostate disease, chronic lung disease, or stroke.

Work, unemployment, financial problems, marital/family conflicts, child/care-giving problems, cultural conflicts, legal or immigration problems, serious illness or death of family member, community violence or crime.

Qualitative study results found that patients perceived depression as a serious condition linked to the accumulation of social stressors. Somatic and anxiety-like symptoms and the cultural idiom of nervios were central themes in low-income Hispanics’ explanatory models of depression. The perceived reciprocal relationships between diabetes and depression highlighted the multiple pathways by which these two illnesses impact each other and support the integration of diabetes and depression treatments. Concerns about depression treatments included fears about the addictive and harmful properties of antidepressants, worries about taking too many pills, and the stigma attached to taking psycho-tropic medications.

DISCUSSION

Baseline data underscore a high prevalence of major depressive disorder, but also lack of adequate treatment, highlighting the need to improve depression care management among low-income Hispanics with diabetes. The high degree of socioeconomic stress reported at baseline and its association with depression severity [33, 63] and the importance of environmental stress to patients found in our qualitative study highlight the importance of providing patient navigation and integrating socioeconomic stress and care barrier management in treating depression among low-income Hispanics. Baseline clinic site differences in receipt of depression care and HbA1c data may be attributable to the availability of diabetes nurse care management and education in one site. Trial depression outcome analyses will provide the opportunity to examine whether the trial intervention model reduces these differences.

Only one-fifth of study participants meeting criteria for MDD reported already receiving either counseling or AM suggesting that patients were not routinely screened for depression and that case finding is indicated. However, ongoing depressive symptoms among those treated could be attributable to treatment adherence (possibly due to lack of responsiveness to patient treatment preference), unaddressed economic and social stress (medication cost concern was independently associated with depression severity), and/or provider failure to monitor depressive symptoms over time and provide maintenance and relapse prevention treatment as indicated. Collaborative care approaches that use individualized stepped care algorithms to address individual patient’s treatment preferences and response and provide ongoing symptom monitoring and relapse prevention are likely to be more effective [64, 65].

Adaptations to MDDP were guided by the assumption that the delivery of quality improvements to diabetes and depression care for low-income populations in safety net clinics must consider potential interactions between economic and sociocultural factors, patient, provider, health care system needs, and clinical pathways characterizing the association between depressive symptoms and diabetes (66, 67). MDDP adaptations aimed to:

maximize recruitment and minimize attrition;

enhance patient engagement and adherence;

reduce patient, provider, and system barriers to depression and diabetes care via the provision of patient navigation;

integrate depression and diabetes care; and

provide culturally and linguistically competent depression care.

Active participation by clinic providers and organizational leadership in the design and implementation of the trial is consistent with current recognition of the need to conduct community based translational science.

Study limitations include that results may not be generalizable to more acculturated Hispanic patients as our sample was primarily composed of foreign-born, Spanish-speaking, Mexican immigrants and that the sample was primarily female. Study sites may not represent other urban or rural primary care clinics. Future studies testing collaborative care within different care systems and with culturally diverse populations providing intervention elements that are dictated by patient and care system characteristics are needed.

Acknowledgments

The authors want to thank Dr. Michael Roybal and Dr. Stanley Leong, Roybal and El Monte Clinic Directors and clinic staff who have provided critical guidance and support for the study.

Footnotes

The study is supported by R01 MH068468 from the National Institute of Mental Health, (PI, Dr. Ell).

Contributor Information

KATHLEEN ELL, University of Southern California, Los Angeles.

WAYNE KATON, University of Washington.

LEOPOLDO J. CABASSA, New York State Psychiatric Institute.

BIN XIE, University of Southern California, Los Angeles.

PEY-JIUAN LEE, University of Southern California, Los Angeles.

SUAD KAPETANOVIC, University of Southern California, Los Angeles.

JEFFRY GUTERMAN, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, and Los Angeles County Department of Health Services.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Health disparities experienced by Hispanics: United States. MMWR. 2004;53(40):935–937. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Umpierrez GE, Gonzalez A, Umpierrez D, Pimentel D. Diabetes mellitus in the Hispanic/Latino population: An increasing health care challenge in the United States. American Journal of Medical Science. 2007;334(4):274–282. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e3180a6efe3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kirk JK, Passmore LV, Bell RA, et al. Disparities in A1C levels between Hispanic and non-Hispanic white adults with diabetes: A meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(2):240–246. doi: 10.2337/dc07-0382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burke JP, Williams K, Haffner SM, et al. Elevated incidence of type 2 diabetes in San Antonio, Texas compared to that of Mexico City, Mexico. Diabetes Care. 2001;24(9):1573–1578. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.9.1573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.West SK, Klein R, Rodriguez J, et al. Diabetes and diabetic retinopathy in a Mexican-American population: Proyecto VER. Diabetes Care. 2001;24(7):1204–1209. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.7.1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Duru OK, Mangione CM, Steers NW, et al. The association between clinical care strategies and the attenuation of racial/ethnic disparities in diabetes care: The Translating Research into Action for Diabetes (TRIAD) Study. Medical Care. 2006;44(12):1121–1128. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000237423.05294.c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harris MI. Racial and ethnic differences in health care access and heath outcomes for adults with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2001;24(3):454–459. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.3.454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nichols GA, Brown JB. Unadjusted and adjusted prevalence of diagnosed depression in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(3):744–749. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.3.744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li C, Ford ES, Strine TW, Mokdad AH. Prevalence of depression among U.S. adults with diabetes: Findings from the 2006 behavioral risk factor surveillance system. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(1):105–107. doi: 10.2337/dc07-1154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ali S, Stone MA, Peters JL, Davies MJ, Khunti K. The prevalence of co-morbid depression in adults with Type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Medicine. 2006;23:1165–1173. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2006.01943.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pineda OAE, Stewart SM, Galindo L, Stephens J. Diabetes, depression, and metabolic control in Latinas. Cultural Diversity Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2007;13(3):225–231. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.13.3.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Groot M, Anderson R, Freedland KE, et al. Association of depression and diabetes complications: A meta-analysis. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2001;63(4):619–630. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200107000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lustman PJ, Anderson RJ, Freedland KE. Depression and poor glycemic control: A meta-analysis review of the literature. Diabetes Care. 2000;23(7):934–942. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.7.934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Egede LE. Diabetes, major depression, and functional disability among U.S. adults. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(2):421–428. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.2.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lanting LC, Joung I, Mackenbach JP, Lamberts SW, Boostma AH. Ethnic differences in mortality, end-stage complications, and quality of care among diabetic patients. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(9):2280–2288. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.9.2280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clouse RE, Lustman PJ, Freedland KE, et al. Depression and coronary heart disease in women with diabetes. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2003;65:376–383. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000041624.96580.1f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Katon WJ, Rutter C, Simon G, et al. The association of co-morbid depression with mortality in patients with Type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(11):2668–2672. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.11.2668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Richardson LK, Egede LE, Mueller M. Effect of race/ethnicity and persistent recognition of depression on mortality in elderly men with Type 2 diabetes and depression. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(5):880–881. doi: 10.2337/dc07-2215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ciechanowski PS, Katon WJ, Russo JE. Depression and diabetes: Impact of depressive symptoms on adherence, function and costs. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2000;160(21):3278–3285. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.21.3278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Egede L, Zheng D, Simpson K. Co-morbid depression is associated with increased health care use and expenditures in individuals with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2002;25(3):464–470. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.3.464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Katon WJ, Russo JE, Von Korff M, Lin EHB, Ludman E, Ciechanowski PS. Long-term effects on medical costs of improving depression outcomes in patients with depression and diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2008 doi: 10.2337/dc08-0032. (online) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Musselman DL, Betan E, Larsen H, Phillips LS. Relationship of depression to diabetes Types 1 and 2: Epidemiology, biology, and treatment. Biological Psychiatry. 2003;54(3):317–329. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00569-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pinto-Meza A, Fernandez A, Serrano-Blanco A, Haro JM. Adequacy of antidepres-sant treatment in Spanish primary care: A naturalistic six-month follow-up study. Psychiatric Services. 2008;59(1):78–83. doi: 10.1176/ps.2008.59.1.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Egede LE. Major depression in individuals with chronic medical disorders: Prevalence, correlates and association with health resource utilization, lost productivity and functional disability. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2007;29(5):409–416. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2007.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sclar DA, Robison LM, Skaer TL. Ethnicity/race and the diagnosis of depression and use of antidepressants by adults in the United States. International Clinical Psychopharmacy. 2008;23(2):106–109. doi: 10.1097/YIC.0b013e3282f2b3dd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sarkar U, Piette JD, Gonzales R, et al. Preferences for self-management support: Findings from a survey of diabetes patients in safety-net health systems. Patient Educational Counseling. 2008;70(1):102–110. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2007.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gonzalez JS, Safren SA, Cagliero E, et al. Depression, self-care, and medication adherence in type 2 diabetes: Relationships across the full range of symptom severity. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(9):2222–2227. doi: 10.2337/dc07-0158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goodnick PJ. Use of antidepressants in treatment of co-morbid diabetes mellitus and depression as well as in diabetic neuropathy. Annals of Clinical Psychiatry. 2001;13(1):31–41. doi: 10.1023/a:1009012815127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gross R, Olfson M, Gameroff MJ, et al. Depression and glycemic control in Hispanic primary care patients with diabetes. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2005;20(5):460–466. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.30003.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Katon WJ, Von Korff M, Lin EH, et al. The pathways study: A randomized trial of collaborative care in patients with diabetes and depression. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2004;61(10):1042–1049. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.10.1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Katon WJ, Unützer J, Fan JW, et al. Cost-effectiveness and net benefit of enhanced treatment of depression for older adults with diabetes and depression. Diabetes Care. 2006;29(2):265–270. doi: 10.2337/diacare.29.02.06.dc05-1572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Borowsky SJ, Rubenstein LV, Meredith LS, et al. Who is at risk of nondetection of mental health problems in primary care? Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2000;15(6):381–388. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.12088.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cabassa LJ, Hansen MC, Palinkas LA, Ell K. Azúcar y nervios: Explanatory models and treatment experiences of Hispanics with diabetes and depression. Social Science and Medicine. 2008;66(12):2413–2424. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.01.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: The PHQ primary care study. Primary care evaluation of mental disorders. Patient Health Questionnaire. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1999;282(18):1737–1744. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.18.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huang FY, Chung H, Kroenke K, et al. Using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 to measure depression among racially and ethnically diverse primary care patients. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2006;21(6):547–552. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00409.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2001;16(9):606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Löwe B, Spitzer RL, Gräfe K, et al. Comparative validity of three screening questionnaires for DSM-IV depressive disorders and physicians’ diagnoses. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2004;78(2):131–140. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(02)00237-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Löwe B, Kroenke K, Herzog W, et al. Measuring depression outcome with a brief self-report instrument: Sensitivity to change of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) Journal of Affective Disorders. 2004;81(1):61–66. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0327(03)00198-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Löwe B, Gräfe K, Zipfel S, et al. Diagnosing ICD-10 depressive episodes: Superior criterion validity of the Patient Health Questionnaire. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics. 2005;73(6):386–390. doi: 10.1159/000080393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wittkampf KA, Naeije L, Schene AH, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of the mood module of the Patient Health Questionnaire: a systematic review. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2007;29(5):388–395. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2007.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cameron IM, Crawford JR, Lawton K, et al. Psychometric comparison of PHQ-9 and HADS for measuring depression severity in primary care. British Journal of General Practice. 2008;58(1):32–36. doi: 10.3399/bjgp08X263794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Simon GE, Ludman EJ, Tutty S, et al. Telephone psychotherapy and telephone care management for primary care patients starting antidepressant treatment: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2004;292(8):935–942. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.8.935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.World Health Organization. Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test— “English.” Vinson DC, Galliher JM, et al. Comfortably engaging: Which approach to alcohol screening should we use? Annals of Family Medicine. 2004;2(5):398–404. doi: 10.1370/afm.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Derogatis L, Lipman RS, Rickels K, et al. The Hopkins Symptom Checklist (HSCL): A measure of primary symptom dimensions. Modern Problems in Pharmacopsychiatry. 1974;7:79–110. doi: 10.1159/000395070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Katon W, Von Korff M, Lin E, et al. Collaborative management to achieve treatment guidelines: Impact of depression in primary care. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1995;273:1026–1031. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Katon W, Robinson P, Von Korff M, et al. A multifaceted intervention to improve treatment of depression in primary care. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1996;53(10):924–932. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830100072009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, et al. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis 1 Disorders (SCID) Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press Inc; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Toolbert DJ, Hampson SE, Russell E. The summary of diabetes self-care activities measure: Results from 7 studies and a revised scale. Diabetes Care. 2000;23(7):943–950. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.7.943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Whitty P, Steen N, Eccles M, et al. A new self-completion outcome measure for diabetes: Is it responsive to change? Quality Life Research. 1997;6(5):407–413. doi: 10.1023/a:1018443628933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Krein SL, Heisler M, Piette JD, Makki M, Kerr EA. The effect of chronic pain on diabetes patients’ self-management. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(1):65–70. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Derogatis LR, Melisaratos N. The Brief Symptom Inventory: An introductory report. Psychology and Medicine. 1983;13(3):595–505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cervantes RC, Padilla AM, Salgado de Snyder N. The Hispanic stress inventory: A culturally relevant approach to psychosocial assessment. Psychological Assessment. 1991;3(3):438–447. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ware JE, Sherbourne CD. The MOS-36 item short-form health survey (SF-36) Medical Care. 1992;30(6):473–481. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sullivan M, Katon W, Russo J, Dobie R, Sakai C. A randomized trial of nortriptyline for severe chronic tinnitus: Effects on depression, disability, and tinnitus symptoms. Archives of Internal Medicine. 1993;153(19):2251–2259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cooper-Patrick L, Powe NR, Jenckes MW, et al. Identification of patient attitudes and preferences regarding treatment of depression. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 1997;12(7):431–438. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1997.00075.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dwight-Johnson M, Sherbourne CD, Liao D, et al. Treatment preferences among depressed primary care patients. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2000;15(8):527–534. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.08035.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dwight-Johnson M, Ell K, Jiuan-Lee P. Can collaborative care address the needs of low-income Latinas with co-morbid depression and cancer? Results from a randomized pilot study Psychosomatics. 2005;46(3):224–232. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.46.3.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nezu A, Nezu C, Perri MG. Problem-solving therapy for depression: Theory, research and clinical guidelines. New York: Wiley; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gilmer TP, Walker C, Johnson ED, Philis-Tsimikas A, Unützer J. Improving treatment of depression among Latinos with diabetes using Project Dulce and IMPACT. Diabetes Care. 2008 doi: 10.2337/dc08-0307. (online) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ell K, Xie B, Quon B, et al. Collaborative care management of depression among low-income patients with cancer: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2009;26(27):4488–4496. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.6371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bernal G, Bonilla J, Bellido C. Ecological validity and cultural sensitivity for outcome research: Issues for the cultural adaptation and development of psychosocial treatments with Hispanics. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1995;23(1):67–82. doi: 10.1007/BF01447045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Katon W, Rutter C, Ludman EJ, et al. A randomized trial of relapse prevention of depression in primary care. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2001;58(3):241–247. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.3.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ell K, Xie B, Wells A, et al. Economic stress among low-income women with cancer: Effects on quality of life. Cancer. 2008;112(3):616–625. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Miranda J, Chung JY, Green BL, et al. Treating depression in predominantly low-income young minority women: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2003;290(1):57–65. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.1.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jarjoura D, Polen A, Baum E, et al. Effectiveness of screening and treatment for depression in ambulatory indigent patients. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2004;19(1):78–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.21249.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Washington DL, Bowles J, Saha S, et al. Transforming clinical practice to eliminate racial-ethnic disparities in healthcare. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2008;23:685–891. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0481-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Golden SH, Lazo M, Carnethon M, et al. Examining a bidirectional association between depressive symptoms and diabetes. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2008;299(23):2751–2759. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.23.2751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]