Abstract

The mature αβ T cell population is divided into two main lineages defined by the mutually exclusive expression of CD4 and CD8 surface molecules (coreceptors), and differing in their MHC restriction and function. CD4 T cells are typically MHC II-restricted and helper (or regulatory) whereas CD8 T cells are typically cytotoxic. Several transcription factors are known to control the emergence of CD4 and CD8 lineages, including the zinc finger proteins Thpok and Gata3 which are required for CD4 lineage differentiation, and the Runx factors Runx1 and Runx3 which contribute to CD8 lineage differentiation. This review summarizes recent advances on the function of these transcription factors in lineage differentiation. We also discuss how the ‘circuitry’ connecting these factors could operate to match expression of lineage-committing factors Thpok and Runx3, and therefore lineage differentiation, to MHC specificity.

Setting the stage: positive selection and lineage choice

Most T lymphocytes carry T cell receptors (TCR) made of α and β chains that recognize peptide antigens bound to class I or class II MHC molecules (MHC-I or MHC-II, respectively). Peptides presented by these molecules differ in multiple respects, most notably by their origin (typically intra-cellularly synthesized molecules for MHC-I, endocytosed molecules for MHC-II). To this duality of antigen corresponds a dichotomy of T cells subsets that differ by the expression of the surface proteins CD8 and CD4, which serve as coreceptors for MHC-I and MHC-II, respectively: MHC-I restricted T cells generally express CD8 whereas MHC II-restricted T cells generally express CD4. Expression of CD4 and CD8 is mutually exclusive on mature T cells and is stably maintained throughout their post-thymic life, thus distinguishing two distinct T cell ‘lineages’. These two lineages differentiate in the thymus from a population of precursors expressing both CD4 and CD8 molecules (‘double positive’ thymocytes, DP).

The ‘choice’ between CD4 and CD8 lineages occurs after thymocytes have rearranged their TCRα and TCRβ genes, and only in those cells that undergo positive selection, i.e. whose TCR recognizes MHC ligands of appropriate avidity in the thymic epithelium (1). In addition to setting Cd4 or Cd8 expression, ‘lineage choice’ also affects the effector differentiation of T cells after antigen encounter, as CD8 effector cells are typically cytotoxic, expressing enzymes such as perforin and granzymes, whereas CD4 effector cells either help or suppress the function of other immune cells. While the characteristic outcome of lineage choice, the matching of CD4-CD8 differentiation to MHC restriction, has been elucidated more than 20 years ago (2-4), the ‘nuts- and-bolts’ have long remained enigmatic. The present review will focus on recent advances in our understanding of the transcriptional circuitry that controls CD4-CD8 lineage choice. Progress, recently discussed in depth (5), has also been made in the identification of environmental signals that direct thymocytes into either lineage; we will come back to this issue near the end of the present review.

Runx proteins and CD8 cell differentiation: an eloquent silencing

The first lead on the transcriptional control of lineage choice came from the identification of a cis-regulatory element, known as the Cd4 silencer, dictating the lineage-specificity of CD4 expression (6-8). Subsequent work led to the breakthrough finding that silencer activity, and therefore the proper control of Cd4 expression, requires its recruitment of Runx transcription factors (9).

The evolutionary conserved Runx family is involved in many differentiation processes and in mammals includes three members (Runx1-3) that act as heterodimers with the structurally unrelated molecule Cbfβ (10). The defining feature of the family, the Runt homology domain, is located near the amino-terminus of each member and mediates binding to DNA and association with Cbf β. Runx-Cbf β dimers either activate or repress transcription, depending on interactions with other factors and possibly post-translational modifications. Runx1 and Runx3, but not Runx2, have been implicated in T cell development (9, 11). Runx1 is expressed at and required for many steps of T cell differentiation (9, 12, 13), notably for the generation of DP thymocytes from their CD4−CD8− (double negative, DN) precursors and for the survival of CD4-lineage cells (9, 13). Runx3 protein is not detected in DP thymocytes or resting CD4 cells, but is up-regulated during the differentiation of CD8 cells in the thymus, and remains expressed in post thymic CD8 cells (13-15)(Fig. 1); this expression pattern strongly correlates with that of mRNAs initiated at the most upstream (distal) of the two Runx3 promoters (13, 16) (Fig. 2A). Runx3 is also expressed in Type 1 CD4 effector cells where it promotes IFNγ production (17, 18).

Figure 1. Thpok, Gata3 and Runx3 expression and function during lineage differentiation.

T cell differentiation stages are depicted on a schematic two-parameter plot of CD4 and CD8 expression. Expression levels of Gata3, Thpok and Runx3 are summarized from negative to high. Checkpoints controled by each factor are indicated (arrows). CD4-differentiating cells are shown in purple, CD8-differentiating cells in green. There is no experimental distinction yet between specification and commitment steps during CD8 lineage differentiation. Although inactivation of both Runx1 and Runx3 is required to prevent CD8 cell development, this presumably reflects functional redundancy between these factors; thus, Runx3 is indicated as the ‘check-point keeper’.

Figure 2. Runx3 and Thpok loci.

(A). Schematic representation of the Runx3 locus showing the distal and proximal promoters (arrows), and the splicing from exon 1 (distal promoter) into the coding sequence of exon 2. As a result, Runx3 proteins translated from either mRNA only differ by their amino-terminal extremity (bottom graphs, cyan and yellow coloring). Dashed lines indicate splicing. Exons are shown as boxes, with coding sequences depicted as thicker rectangles.

(B). The Thpok locus is schematically depicted. Coding sequences are in exons 2 and 3 and depicted as thick orange rectangles. Exons 1a and 1b are transcribed from alternative start sites. The proximal (3′) site is used preferentially in mature CD4 T cells, whereas the distal site is preferentially active in early thymocytes (57). Binding sites for Gata3, Runx and Thpok proteins are shown as boxes underneath the sequence. Cis-regulatory elements identified by knockout or transgenic reporter analyses are indicated at the bottom of the graph and include the silencer, part of the distal regulatory element, the general T lymphoid element (GTE), active throughout T cell development (57), and the proximal enhancer (or proximal regulatory element [PRE], Refs. 19, 57). Knockout analyses have shown that the proximal enhancer is required for sustained Thpok transcription in mature CD4-lineage thymocytes and T cells (48). Deletion of the segment encompassing both Gata3 sites (and the proximal enhancer) severely reduced Thpok transcription in BAC reporter analyses (bracket) (40). Drawings are not on scale.

In agreement with these expression patterns, Runx1 represses Cd4 in DN thymocytes whereas Runx3 is required for the proper silencing of Cd4 in CD8-differentiating cells (9, 13, 14). Although Runx3 disruption does not prevent CD8 cell differentiation, it results in reduced numbers of CD8 T cells, of which a substantial fraction maintains CD4 expression and therefore appear CD4+CD8+. This phenotype reflects the functional redundancy between Runx1 and Runx3, as thymocytes lacking both molecules, or the obligatory dimerization partner Cbfβ (both referred to as ‘Runx-deficient’ thereafter), fail to differentiate into CD8 cells altogether (13, 16, 19). This compensatory effect is explained in part by the increased expression of Runx1 in Runx3-deficient cells (16), suggesting that Runx3 is the physiological effector of CD8 differentiation.

How do Runx factors promote CD8 lineage choice? Not only they repress Cd4, the CD4-lineage defining gene in post-thymic cells (9, 14, 20-22), but experiments in peripheral cells indicate that they promote the expression of genes characteristic of the CD8 lineage, including those encoding cytotoxic enzymes perforin and Granzyme B, the cytokine IFNγ and the transcription factor Eomes (23, 24). Furthermore, Runx3-deficient CD8 cells have reduced CD8 expression (13), and Runx3 binds to a Cd8 enhancer specifically active in mature CD8 T cells (15). These observations indicate that Runx3 promotes expression of CD8-lineage genes in mature T cells (13, 15), and suggest that it contributes in the thymus to establish gene expression programs specific of the CD8 lineage, an activity often referred to as lineage specification (25).

The central role of Runx in CD8-lineage choice is underscored by the finding that Runx-deficient MHC I-restricted thymocytes not only fail to become CD8 cells, but in fact become CD4 T cells (16, 19). Thus, Runx activity, and the physiological player is probably Runx3, is necessary for CD8-lineage commitment. However, there is evidence that Runx is not the only activity necessary for CD8 commitment: enforced expression of Runx3 does not ‘redirect’ MHC II-restricted thymocytes into the CD8 lineage (21, 22), suggesting that CD8-lineage choice requires additional factors, expressed in MHC-I but not in MHC-II signaled cells, that would cooperate with Runx molecules. We will return to this issue in discussing the transcriptional ‘circuitry’ of lineage choice.

The identity of these factors is a critical, but as yet unanswered, question for our understanding of lineage choice. Other than Runx proteins and their known co-factors (26), the only nuclear molecule shown so far to be specifically required for CD8 cell development is the transcription factor IRF1. Although IRF1 acts in part indirectly through its ability to promote MHC-I expression by thymic stromal cells, it also promotes CD8-differentiation in a direct, thymocyte-intrinsic manner (27). The T-box protein Eomes promotes effector differentiation of mature CD8 cells, and notably expression of cytotoxic genes, but is not required for their intrathymic differentiation (28, 29). Other transcription factors, including Mazr, NF-κB and E-box binding proteins, as well as the Notch pathway, have been proposed to be involved, positively or negatively, in CD8 cell development (30-34); their role(s) in this process, and notably whether they affect lineage differentiation per se, remains to be clarified.

Making a CD4 T cell

Thpok and Gata3 are required for CD4 cell development

Two ‘CD4-differentiating’ transcription factors, Thpok (the product of a gene officially named Zbtb7b that will herein be referred to as Thpok for simplicity) and Gata3, were identified during the last few years. Thpok belongs to a large family of transcription factors, generally acting as repressors, characterized by a carboxy-terminal DNA binding domain made of multiple zinc fingers (four in Thpok) and an amino-terminal BTB-POZ domain that mediates homo- (and possibly hetero-) dimerization (35). Thpok was identified as essential for CD4 differentiation after a patient quest to identify a spontaneous mutation (‘helper-deficient’, HD) causing a disruption of mouse CD4 cell development (36, 37). The culprit proved to be a single aminoacid substitution in the second zinc finger of Thpok (38). In a separate study (39), Thpok (then named cKrox) was identified in a microarray screen for genes up-regulated during positive selection and shown by gain-of-function analyses to inhibit CD8- and promote CD4-differentiation.

Two properties of Thpok deserve emphasis. First, although Thpok is expressed in a wide variety of cells, its expression in the thymus is highly lineage-specific (38, 39): CD4 SP thymocytes (and all CD4 T cells) express Thpok, whereas DP and CD8 SP thymocytes do not. During MHC II-induced selection, Thpok is up-regulated progressively as thymocytes down-regulate CD8 (Fig. 1). Second, both loss- and gain-of-function experiments indicate that Thpok affects lineage choice but not positive selection. That is, Thpok-deficient MHC-II restricted thymocytes become CD8 instead of CD4 T cells. These analyses, initially performed in HD mice (37), were the first genetic demonstration that lineage choice and positive selection were independent, even if contemporaneous, processes. They were recently recapitulated in mice carrying a null allele of Thpok (16, 19, 40), demonstrating that lineage ‘redirection’ does not result from an aberrant activity of the mutant protein. Conversely, transgenic expression of Thpok in MHC I-restricted thymocytes prevents their CD8 differentiation and redirects them into the CD4 lineage (38, 39). The simplest interpretation of these experiments is that Thpok controls a key checkpoint after MHC II-signaled thymocytes are rescued from programmed cell death, at which point it is required for CD4 lineage commitment and its absence ‘redirects’ cells into the CD8 lineage. This Thpok-operated checkpoint occurs after the down-regulation of Cd8 expression, as Thpok-deficient MHC II-signaled thymocytes are arrested as CD4+CD8lo (16, 19, 40). Of note, both coreceptor expression and functional differentiation are mismatched to MHC specificity in ‘redirected’ thymocytes: Thpok-deficient MHC II-restricted cells express CD8 and cytotoxic markers, whereas Thpok transgenic MHC I-restricted cells express CD4 and helper markers (16, 38, 39).

Although the spotlight has recently been on Thpok, the first transcription factor identified as necessary for CD4 but not CD8 cell differentiation is Gata3, a member of a distinct zinc finger protein family (41-43). Gata3 is expressed at and required for multiple steps of T cell development, from early T lineage specification to effector differentiation of mature CD4 cells (44). Positive selection is accompanied by asymmetric changes in Gata3 expression (Fig. 1), which is low but detectable in DP thymocytes, is up-regulated in CD4-differentiating thymocytes, but goes down during CD8 differentiation (42, 45). Loss-of-function analyses, using conditional deletion of Gata3 in DP thymocytes or retroviral ‘knock-down’ shRNA transduction, showed that Gata3 is required for the development of CD4 but not of CD8 cells (41, 42).

Gata3, Thpok and CD4-lineage differentiation

A recent study compared the functions of Gata3 and Thpok during CD4 differentiation (40). Similar to Thpok, Gata3 is required before CD4 lineage commitment: that is, Gata3-deficient MHC II-restricted thymocytes can be ‘redirected’ to the CD8 lineage. However, when assessed on thymocytes with a diverse endogenous TCR repertoire, this ‘redirection’ is not as efficient as that of Thpok-deficient cells (40), probably explaining why it is observed with some but not all TCR specificities (40, 41, 46). Analyses of Thpok and Gata3 expression in thymocytes undergoing positive selection in the absence of the other molecule defined the sequence of intervention of these factors. The normal up-regulation of Gata3 was observed in Thpok-deficient MHC II-restricted thymocytes; in contrast, no Thpok was detected in Gata3-deficient thymocyt Thus, Gata3 is required for the expression, and presumably acts upstream, of Thpok (which does not exclude that Gata3 also promotes the terminal differentiation or survival of CD4 cells as originally proposed, Ref. 41).

These findings raised the tantalizing possibility that Gata3 is needed for CD4 cell differentiation simply to promote Thpok expression. However, this is not the case: enforcing Thpok expression in Gata3-deficient thymocytes (using a Thpok transgene) does not restore their CD4 differentiation (40), indicating that Thpok requires Gata3 to promote CD4 differentiation. Thus, Gata3 is required before commitment to the CD4 lineage, and serves to promote the expression of Thpok and other factors required for CD4 lineage differentiation.

Strikingly, although Gata3 is required for Thpok to promote CD4 differentiation, Gata3 is not required for Thpok to inhibit CD8 differentiation, as transgenic expression of Thpok blocked the CD8 differentiation of Gata3-deficient cells (40). Clues for the interpretation of this observation came from studies of Thpok function in post-thymic T cells. When retrovirally transduced into mature CD8 cells, Thpok represses expression of CD8 lineage genes, including those encoding CD8 and cytotoxic effectors perforin and Granzyme B (47). Conversely, conditional Thpok disruption in mature CD4 cells causes CD8 re-expression and promotes expression of Granzyme B (23). In contrast, gain- and loss-of-function analyses suggest a lesser role of Thpok in promoting expression of CD4 or CD4-lineage genes (23, 47). Another key observation comes from mice carrying an hypomorphic Thpok allele that directs expression of insufficient levels of a wild-type Thpok protein. Although such low-level Thpok expression supports the generation of CD4 SP thymocytes and T cells, these cells inappropriately express CD8-lineage genes (16, 23, 48).

It is useful at this point to come back to the distinction between ‘specification’ and ‘commitment’ (25). The idea is that lineage-specific gene expression programs are progressively ‘specified’ in response to external cues in precursors that are initially bipotent and have been ‘primed’ into a non-polarized gene expression pattern. Such lineage divergence remains reversible until the cells undergo commitment, biologically defined as the loss of alternate development fates (25). In this context, the findings summarized above suggest that the main function of Thpok is not to promote CD4-lineage gene expression but to prevent the onset of CD8-lineage gene expression, that is to promote CD4-lineage commitment, and that this committing activity would not require Gata3 (40). Conversely, the fact that Thpok fails to rescue the CD4-differentiation of Gata3-deficient thymocytes indicates that Gata3 is required for CD4 lineage specification (40).

That Thpok is not required for CD4 specification was actually established by assessing the development of thymocytes deficient for both Thpok and Cbfβ (16). These cells carry a germline Thpok disruption and delete a conditional Cbfb allele (thereby losing Runx activity altogether) in pre-DP thymocytes. Whereas Thpok-deficient MHC II-restricted thymocytes are ‘redirected’ into the CD8 lineage, double-deficient (Thpok and Runx) cells adopt a CD4 fate. Thus, Thpok is not needed to specify the CD4 lineage, but it prevents Runx-directed CD8 lineage differentiation, i.e. serves to promote CD4 commitment. The presence of CD4-lineage cells in Thpok-Runx double-deficient mice but not in Thpok single-deficient mice suggests that Runx inhibits the expression or function of one or more CD4-lineage specifying factors that direct Runx-deficient cells towards the CD4 lineage. Gata3 is an interesting candidate for this function, as analyses in peripheral T cells suggest that Runx activity represses Gata3 expression (49), and the same may be true in thymocytes.

Gata3 promotes CD4-lineage specification

The role of Gata3 in CD4-lineage specification has yet to be fully explored. There is evidence that Gata3 directly activates CD4-lineage genes, as Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) experiments documented binding of Gata3 to two distinct sites within a region of the Thpok locus important for its expression (Fig. 2B) (40). Although the contribution of each of these sites to Thpok expression is not yet known, these findings suggest that Gata3 serves as a direct activator of Thpok transcription. In addition (or alternatively) to such a direct effect on CD4-lineage genes, it is possible that Gata3 promotes the expression of genes that are not lineage specific but are nonetheless required for CD4 lineage choice, and thereby brings MHC II-restricted thymocytes to a stage where they are competent for CD4-lineage commitment. Specifically, in line with the concept that TCR signals of greater duration are required for CD4 than for CD8 differentiation (5), it is possible that Gata3 promotes the expression of genes important for TCR signal transduction. The absence of obvious TCR signaling defect in Gata3-deficient DP thymocytes (41) does not exclude this possibility, as the phenotypic manifestations of Gata3 gene disruption depend on the half-life of Gata3 molecules and of the products of their target genes, all of which are largely unknown at present. In addition, it is conceivable that thymocytes undergoing positive selection, in which expression of TCR and Gata3 are higher than in DP cells, are more stringently dependent on Gata3 for TCR signaling. Supporting such possibilities, expression of targets of TCR signaling (including TCR itself and the adhesion molecule CD69), is lower in Gata3-deficient than in Gata3-sufficient intrathymically signaled thymocytes (40, 41). Reduced TCR signaling in the absence of Gata3 would also explain the small numbers of ‘CD8-redirected’ MHC II-restricted cells in Gata3-deficient thymi, as these cells may fail to complete their differentiation in the absence of appropriate signaling.

A transcriptional network promoting CD4 cell differentiation

Two other transcription factors, Myb and Tox, have been shown to promote CD4 cell differentiation. Myb, the product of the proto-oncogene c-myb, is highly expressed in DP thymocytes (unlike Gata3 or Thpok), is down-regulated during the DP to SP transition, but remains higher in CD4- than in CD8-differentiating thymocytes. Inactivation of Myb in DP thymocytes impairs CD4 but not CD8 cell development; conversely, a constitutively active form of Myb (vMyb) inhibits CD8 T cell development without ‘redirecting’ MHC-I restricted thymocytes into the CD4 lineage (50, 51). Analyses of gene expression in Myb-deficient cells indicate that Myb is important for Gata3 transcription; accordingly, transient transfection experiments and ChIP assays suggest a direct activation of the Gata3 promoter by Myb (51). Such an effect would explain why Myb is important for CD4 cell differentiation, but not the strong inhibition of CD8 cell development by vMyb, as enforced Gata3 expression only modestly inhibits CD8-lineage differentiation (Ref. 52, and K. Wildt and R.B., unpublished observations).

Tox, an HMG domain-containing nuclear protein, is required for the development of CD4 cells and acts upstream of Thpok (53). Tox disruption substantially impairs CD8 cell development, suggesting that it is important for a late positive selection step in addition to, or rather than, CD4 lineage differentiation per se. It is difficult at present to locate the checkpoint controled by Tox. The requirements for Tox, Gata3 and Thpok during the differentiation of NK T cells suggest that Tox acts upstream of Gata3 and Thpok. NK T cells recognize CD1d-bound lipid antigens through TCRαβ receptors with limited diversity (54), and normally are either CD4− CD8− or CD4+CD8−. Although the mechanisms dictating coreceptor expression by NK T cells are unclear, Tox, but not Gata3 or Thpok is required for the differentiation of NK T cells regardless of their coreceptor expression (Refs. 53, 55, and L.W. and R. B., unpublished observations). This is consistent with the idea that Tox affects a developmental step independent of, and preceding, Gata3 and Thpok upregulation and CD4-lineage differentiation. However, arrested Tox-deficient conventional thymocytes, which display a unique CD4loCD8lo surface phenotype, have up-regulated Gata3 (53), suggesting that Tox is not simply upstream of Gata3 in a linear cascade of transcription factors promoting CD4 differentiation.

While additional studies will be needed to connect Tox, Gata3 and Thpok transcription factors, recent findings have established significant links between Runx factors and Thpok, on which the rest of this review will focus.

The ‘circuitry’ of lineage choice

A negative feed back loop between Thpok and Runx3 ensures lineage choice

Two recent reports (16, 19) have laid out the concept that a cross-repression between Thpok and Runx3 acts as the keystone of lineage choice, preventing co-expression of both factors in mature thymocytes (Fig. 3). Analyses of Runx3 expression using a ‘knocked-in’ reporter allele showed that the Runx3 distal promoter, whose activity in thymocytes and resting T cells is normally CD8-lineage specific, is active in MHC II-signaled Thpok-deficient thymocytes (16). Similarly, the Runx3 distal promoter is active in mature CD4 cells generated in mice carrying hypomorphic Thpok alleles and displaying aberrant CD8-lineage gene expression (16, 23, 48). Thus, as had been proposed early on (56), Thpok represses Runx3 expression, and future studies will determine whether this activity of Thpok is direct or not.

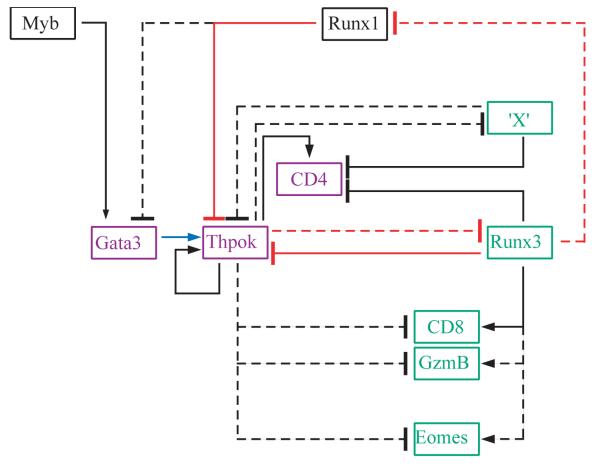

Figure 3. Transcriptional ‘circuitry’ controling CD4-CD8 lineage differentiation.

Transcription factors and selected target genes expressed in CD4-differentiating (purple) or CD8-differentiating (green) or in a non-lineage specific manner (black) are connected in a draft transcriptional regulatory network controling lineage differentiation. Connections depict a functionally relevant gene activation (arrow-ending lines) or inhibition (bar-ending lines). Plain lines indicate direct transcription factor binding validated by ChIP assays. Connections between Thpok and Runx are shown in red, and the Gata3-Thpok link in blue. Note that the repression of Gata3 by Runx1 has so far been documented in peripheral cells only. ‘X’ refers to putative transcription factors required for Runx-mediated Cd4 silencing. The antagonism by Thpok of Runx-mediated Cd4 repression involves direct binding of Thpok to the Cd4 silencer (48), presumably protecting the silencer from Runx-mediated repression, and has also been proposed (71) to involve the Thpok-mediated repression of putative ‘X’ factors that contribute with Runx proteins to repress Cd4 and Thpok expression.

Reciprocally, Runx molecules repress Thpok expression, as shown notably by the aberrant expression of Thpok in Runx-deficient DP thymocytes (19). There is evidence that this repression is direct (19), through the recruitment of Runx complexes to a silencer located 3.1 kbp upstream of the Thpok gene (Fig. 2B). The silencer, part of a Distal Regulatory Element (DRE) that displays enhancer activity in some contexts (57), was shown by transgenic reporter analyses to prevent inappropriate expression of Thpok in DP thymocytes and CD8-lineage cells (19, 57). The importance of this element was demonstrated in mice carrying a ‘knockin’ Thpok-GFP allele, from which the silencer had been deleted. GFP was expressed in both CD4 and CD8 cells, suggesting that, similar to Cd4, transcriptional repression is essential to restrict expression of Thpok to the CD4 lineage (19). ChIP analyses have identified two Runx binding sites within the silencer (19), and one study found these sites required for proper Thpok repression in CD8 cells (19). However, another study mapped ‘active sites’ of the silencer to a 80 bp ‘core’ located upstream of, and thus not including, the Runx binding sites (57). Detailed silencer mutagenesis by homologous recombination will be useful to delineate the respective contributions of these regulatory elements to Thpok expression.

Initiating Thpok and Runx3 expression

The picture emerging from these findings is that of a negative regulatory loop connecting Thpok and Runx3, and leading to a ‘winner take all’ expression of one of these factors only (Fig. 3). Indeed, analyses with ‘knockin’ fluorescent reporter alleles suggest that there is no high-level co-expression of Thpok and Runx3 in wild-type thymocytes (16). Such a scenario, which has been proposed as a general mechanism for lineage divergence (58), raises two questions: what represses expression of these factors in DP thymocytes (in which neither is appreciably expressed), and what promotes the expression of either of them (and thereby the repression of the other) in cells that undergo positive selection.

Although cis-regulatory analyses of Thpok and Runx3 genes are not yet advanced enough to answer these questions, two important notions have emerged from analyses of the Thpok silencer (19). First, the silencer serves two successive functions, similar but not identical, during T cell development. As discussed above, it restricts Thpok expression to the CD4 lineage by preventing its up-regulation in MHC I-restricted thymocytes, an activity presumably involving Runx3. In addition, the silencer represses Thpok in pre-selection DP cells (and thereby differs from the Cd4 silencer that is inactive in DP thymocytes). This function of the silencer depends at least in part on Runx, since low level Thpok expression can be detected in Runx-deficient pre-selection DP thymocytes (19), unlike in their wild-type counterparts (38, 39). As Runx3 is not expressed in DP cells, these findings indicate that Thpok is kept in check in pre-selection thymocytes by silencer-recruited complexes, presumably nucleated around Runx1. The second notion stems from the observation that Thpok expression in silencer-deficient DP thymocytes remains much lower than in mature T cells (19). Thus, activating factors acting on additional Thpok cis-regulatory elements (Fig. 2B)(19, 48, 57) must promote Thpok transcription in cells undergoing selection.

How this circuitry operates to restrict Thpok expression to MHC II-signaled thymocytes is obviously the key question. Two distinct but non-mutually exclusive frameworks must be considered when addressing this question, depending on whether external ‘committing’ signals are delivered to MHC-II or MHC I-restricted thymocytes. First, it is possible that signals specific to MHC II-restricted thymocytes cause Thpok up-regulation (and therefore decide CD4 commitment). The simplest perspective would be that such signals up-regulate Thpok activators binding positive cis-regulatory element within the locus, and thereby overcome silencer activity. A significant obstacle to this perspective is that expression of the silencer-deficient Thpok-GFP allele is as high in CD8 as in CD4 SP Thpok-sufficient thymocytes (19). Thus, in the absence of silencer activity, similar Thpok expression levels can be reached in MHC-I and MHC II-signaled cells, and Thpok activators are not specific of MHC II-signaled cells. These findings suggest that silencer activity is dominant over Thpok activators induced by positive selection and is the key restraint on Thpok expression; they lead to a variation on this first theme, whereby signals specific to MHC II-restricted thymocytes would antagonize silencer activity and allow Thpok up-regulation (19). Such signals could conceivably target the activity of Runx1 molecules, or the expression or activity of other factors important for silencing. Along this line, Thpok molecules were shown to bind the Thpok silencer by ChIP analyses, suggesting that Thpok counteracts silencer activation and therefore contributes to a positive feed back loop promoting its own expression (48). Although this mechanism may be important for sustained Thpok expression in mature CD4 cells, it is unclear whether it contributes to initial Thpok up-regulation, as analyses with a Thpok-GFP reporter allele indicate that high-level Thpok expression in the thymus does not require expression of Thpok molecules (Refs. 16, 48, and L.W. and R.B., unpublished observations).

From the point of view of the circuitry, the reciprocal framework, namely that the lineage specificity of Thpok expression results from CD8-committing signals delivered to MHC I-restricted thymocytes, is equally possible. The idea here is that sustained silencer activation in response to such signals keeps Thpok activators in check and prevents its up-regulation in these cells. While it is possible that such signals would act by up-regulating Runx3, it is also possible that they activate the silencer by extending or increasing the repressive activity of Runx1-nucleated complexes. That second possibility would fit with the observations that the activity of the Runx3 distal promoter does not require MHC I-specific signals, as it is expressed in Thpok-deficient MHC-II restricted thymocytes, and that Thpok is kept silent in MHC I-restricted thymocytes prior to detectable Runx3 up-regulation (16).

Plugging-in environmental cues

It is time to let environmental signals enter this discussion. This has been a controversial subject, and the reader is referred to previous reviews for a full perspective on the topic (5, 56, 59, 60). Within the last few years however, a strong case has emerged the duration of TCR signaling during selection determines lineage choice, with persistent TCR signaling promoting CD4 lineage choice, and transient TCR signaling promoting CD8 lineage choice (5). The ‘kinetic signaling’ model offers an elegant rationale as to why TCR signaling would persist longer in MHC-II than in MHC-I signaled thymocytes (61, 62). It proposes that TCR signaling in DP thymocytes (regardless of MHC specificity) down-regulates expression of the Cd8 gene, and therefore of CD8 surface proteins, but not that of Cd4. In this perspective, the down-regulation of the coreceptor necessary for MHC I-induced signaling generates a signaling asymmetry that is the core engine of lineage choice (62). This basic idea is supported by analyses of T cell development in mice engineered to prematurely terminate TCR signaling or CD4 expression in response to positive selection signals (63, 64).

As previously noted (5, 65), the core ‘kinetic signaling’ concept, namely that signaling persists longer in MHC-II than in MHC I-signaled cells, fits with the idea that such persistent signals trigger Thpok expression in MHC II-restricted thymocytes. Indeed, there is evidence that TCR signaling promotes Thpok expression (57), although the absence of appropriate in vitro conditions for CD4-lineage differentiation complicates these analyses. The ‘kinetic signaling’ model also proposes that IL-7 cytokine signaling contributes to CD8-lineage choice (62). In line with this possibility, it has been proposed that IL-7 activates the Thpok silencer by inducing Runx3 (5), highlighting that the two frameworks discussed above are complementary rather than mutually exclusive.

Much remains to be done to identify intermediates between environmental signals and the core Runx-Thpok loop. The best candidate so far has been Gata3, owing to its greater up-regulation in MHC II- than MHC I-signaled thymocytes (42, 45). Furthermore, the potential positive effect of Gata3 on TCR signal transduction would place Gata3 at the center of a positive feedback loop amplifying differences in TCR signaling and converting them into qualitatively distinct outcomes (66). However, enforced expression of Gata3 in developing thymocytes does not significantly affect lineage choice (Refs. 42, 52, and K.F. Wildt and R.B, in preparation), suggesting that Gata3 is not the key ‘missing link’ between TCR signals and Thpok expression.

Although the identification of the negative feed-back loop between Thpok and Runx is a major progress in our understanding of CD4-CD8 differentiation, there is considerable evidence that this loop requires other factors to operate properly, and such factors are as many potential targets for environmental signals. First, Runx activity is not sufficient for Thpok repression: Runx binds the Thpok silencer not only in DP thymocytes and in CD8 cells but also in CD4 cells that express Thpok (19), and there is evidence that additional segments of the silencer are required for its function (57). Accordingly, and as already alluded to, Runx activity is not sufficient to prevent CD4 differentiation, as enforcing Runx1 or Runx3 expression in thymocytes does not per se impair CD4 lineage differentiation (21, 22, 67) or Thpok expression (L.W. et al., in preparation). Although Runx3-transgenic mice have reduced CD4 SP cell populations, this is due to Runx3-mediated inhibition of CD4 expression in DP thymocytes, as normal numbers of CD4 cells develop in Runx3-transgenic mice lacking the Cd4 silencer in which CD4 expression is insensitive to Runx3 (21). Altogether, these findings make a strong case that Runx activity represses Thpok and promotes CD8 commitment in cooperation with other rate-limiting factors, expressed in MHC-I but not in MHC-II signaled cells. It is possible that these factors are similar or identical to those proposed to bind the Cd4 silencer and to cooperate with Runx to repress Cd4 (68), although the composition or regulation of Cd4 and Thpok repressing complexes likely differs since Cd4 but not Thpok is expressed in DP thymocytes.

Conclusions and perspectives

The last few years have seen substantial progress in our understanding of CD4-CD8 lineage differentiation. Key transcription factors promoting CD4 (Thpok, Gata3) or CD8 (Runx3) lineage differentiation have been identified, setting the foundation for the transcriptional regulatory network controling lineage differentiation. These new findings have brought new challenges and placed older ones under a new spotlight. Among the latter is the connection between transcription factors and signals (including attributes of TCR signaling) that contribute to lineage choice, including determining whether Thpok is induced by TCR signals, as suggested by in vitro stimulation experiments (57). Another area of investigation concerns the unknown factors that promote CD8 lineage differentiation, and may contribute to the repression of Thpok or Cd4 in CD8-lineage cells and possibly to the lineage specific activity of some Cd8 enhancers (8). Perhaps most critically, the progress made in identifying DNA binding proteins that control lineage choice has yet to be matched in understanding the mechanistics of gene activation or silencing. Although conditional deletion of the Cd4 silencer indicates that Cd4 silencing is epigenetically maintained in post-thymic CD8 cells (69), it remains to be determined how the Cd4 locus evolves from reversible repression in CD8-differentiating thymocytes to epigenetic silencing in mature T cells, and more generally whether and how the transcription factors that control lineage choice in thymocytes deposit epigenetic marks that restrain gene expression in post-thymic cells (70).

Acknowledgements

We thank B.J. Fowlkes, Paul Love and Al Singer for fruitful discussions, and Jon Ashwell, S. Murty Shrinivasula, Naomi Taylor and Al Singer for reading the manuscript.

Footnotes

Research work in the authors’ laboratory is supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research, NIH.

References

- 1.Starr TK, Jameson SC, Hogquist KA. Positive and negative selection of T cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2003;21:139–176. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Teh HS, Kisielow P, Scott B, Kishi H, Uematsu Y, Bluthmann H, von Boehmer H. Thymic major histocompatibility complex antigens and the alpha beta T-cell receptor determine the CD4/CD8 phenotype of T cells. Nature. 1988;335:229–233. doi: 10.1038/335229a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sha WC, Nelson CA, Newberry RD, Kranz DM, Russell JH, Loh DY. Selective expression of an antigen receptor on CD8-bearing T lymphocytes in transgenic mice. Nature. 1988;335:271–274. doi: 10.1038/335271a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaye J, Hsu ML, Sauron ME, Jameson SC, Gascoigne NR, Hedrick SM. Selective development of CD4+ T cells in transgenic mice expressing a class II MHC-restricted antigen receptor. Nature. 1989;341:746–749. doi: 10.1038/341746a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Singer A, Adoro S, Park JH. Lineage fate and intense debate: myths, models and mechanisms of CD4-versus CD8-lineage choice. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:788–801. doi: 10.1038/nri2416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sawada S, Scarborough JD, Killeen N, Littman DR. A lineage-specific transcriptional silencer regulates CD4 gene expression during T lymphocyte development. Cell. 1994;77:917–929. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90140-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Siu G, Wurster AL, Duncan DD, Soliman TM, Hedrick SM. A transcriptional silencer controls the developmental expression of the CD4 gene. EMBO J. 1994;13:3570–3579. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06664.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Taniuchi I, Ellmeier W, Littman DR. The CD4/CD8 lineage choice: new insights into epigenetic regulation during T cell development. Adv Immunol. 2004;83:55–89. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(04)83002-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Taniuchi I, Osato M, Egawa T, Sunshine MJ, Bae SC, Komori T, Ito Y, Littman DR. Differential requirements for Runx proteins in CD4 repression and epigenetic silencing during T lymphocyte development. Cell. 2002;111:621–633. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01111-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Speck NA, Gilliland DG. Core-binding factors in haematopoiesis and leukaemia. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:502–513. doi: 10.1038/nrc840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Collins A, Littman DR, Taniuchi I. RUNX proteins in transcription factor networks that regulate T-cell lineage choice. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:106–115. doi: 10.1038/nri2489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lorsbach RB, Moore J, Ang SO, Sun W, Lenny N, Downing JR. Role of RUNX1 in adult hematopoiesis: analysis of RUNX1-IRES-GFP knock-in mice reveals differential lineage expression. Blood. 2004;103:2522–2529. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-07-2439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Egawa T, Tillman RE, Naoe Y, Taniuchi I, Littman DR. The role of the Runx transcription factors in thymocyte differentiation and in homeostasis of naive T cells. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1945–1957. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Woolf E, Xiao C, Fainaru O, Lotem J, Rosen D, Negreanu V, Bernstein Y, Goldenberg D, Brenner O, Berke G, Levanon D, Groner Y. Runx3 and Runx1 are required for CD8 T cell development during thymopoiesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:7731–7736. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1232420100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sato T, Ohno S, Hayashi T, Sato C, Kohu K, Satake M, Habu S. Dual functions of Runx proteins for reactivating CD8 and silencing CD4 at the commitment process into CD8 thymocytes. Immunity. 2005;22:317–328. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Egawa T, Littman DR. ThPOK acts late in specification of the helper T cell lineage and suppresses Runx-mediated commitment to the cytotoxic T cell lineage. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:1131–1139. doi: 10.1038/ni.1652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Djuretic IM, Levanon D, Negreanu V, Groner Y, Rao A, Ansel KM. Transcription factors T-bet and Runx3 cooperate to activate Ifng and silence Il4 in T helper type 1 cells. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:145–153. doi: 10.1038/ni1424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Naoe Y, Setoguchi R, Akiyama K, Muroi S, Kuroda M, Hatam F, Littman DR, Taniuchi I. Repression of interleukin-4 in T helper type 1 cells by Runx/Cbf beta binding to the Il4 silencer. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1749–1755. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Setoguchi R, Tachibana M, Naoe Y, Muroi S, Akiyama K, Tezuka C, Okuda T, Taniuchi I. Repression of the transcription factor Th-POK by Runx complexes in cytotoxic T cell development. Science. 2008;319:822–825. doi: 10.1126/science.1151844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Telfer JC, Hedblom EE, Anderson MK, Laurent MN, Rothenberg EV. Localization of the domains in Runx transcription factors required for the repression of CD4 in thymocytes. J Immunol. 2004;172:4359–4370. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.7.4359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grueter B, Petter M, Egawa T, Laule-Kilian K, Aldrian CJ, Wuerch A, Ludwig Y, Fukuyama H, Wardemann H, Waldschuetz R, Moroy T, Taniuchi I, Steimle V, Littman DR, Ehlers M. Runx3 Regulates Integrin {alpha}E/CD103 and CD4 Expression during Development of CD4-/CD8+ T Cells. J Immunol. 2005;175:1694–1705. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.3.1694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kohu K, Sato T, Ohno S, Hayashi K, Uchino R, Abe N, Nakazato M, Yoshida N, Kikuchi T, Iwakura Y, Inoue Y, Watanabe T, Habu S, Satake M. Overexpression of the Runx3 transcription factor increases the proportion of mature thymocytes of the CD8 single-positive lineage. J Immunol. 2005;174:2627–2636. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.5.2627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang L, Wildt KF, Castro E, Xiong Y, Feigenbaum L, Tessarollo L, Bosselut R. The zinc finger transcription factor Zbtb7b represses CD8-lineage gene expression in peripheral CD4+ T cells. Immunity. 2008;29:876–887. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cruz-Guilloty F, Pipkin ME, Djuretic IM, Levanon D, Lotem J, Lichtenheld MG, Groner Y, Rao A. Runx3 and T-box proteins cooperate to establish the transcriptional program of effector CTLs. J Exp Med. 2009;206:51–59. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rothenberg EV. Stepwise specification of lymphocyte developmental lineages. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2000;10:370–379. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(00)00098-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yarmus M, Woolf E, Bernstein Y, Fainaru O, Negreanu V, Levanon D, Groner Y. Groucho/transducin-like Enhancer-of-split (TLE)-dependent and -independent transcriptional regulation by Runx3. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:7384–7389. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602470103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Penninger JM, Mak TW. Thymocyte selection in Vav and IRF-1 gene-deficient mice. Immunol Rev. 1998;165:149–166. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1998.tb01237.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pearce EL, Mullen AC, Martins GA, Krawczyk CM, Hutchins AS, Zediak VP, Banica M, DiCioccio CB, Gross DA, Mao CA, Shen H, Cereb N, Yang SY, Lindsten T, Rossant J, Hunter CA, Reiner SL. Control of effector CD8+ T cell function by the transcription factor Eomesodermin. Science. 2003;302:1041–1043. doi: 10.1126/science.1090148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Intlekofer AM, Banerjee A, Takemoto N, Gordon SM, Dejong CS, Shin H, Hunter CA, Wherry EJ, Lindsten T, Reiner SL. Anomalous type 17 response to viral infection by CD8+ T cells lacking T-bet and eomesodermin. Science. 2008;321:408–411. doi: 10.1126/science.1159806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bilic I, Koesters C, Unger B, Sekimata M, Hertweck A, Maschek R, Wilson CB, Ellmeier W. Negative regulation of CD8 expression via Cd8 enhancer-mediated recruitment of the zinc finger protein MAZR. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:392–400. doi: 10.1038/ni1311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Laky K, Fowlkes BJ. Notch signaling in CD4 and CD8 T cell development. Curr Opin Immunol. 2008;20:197–202. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2008.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Laky K, Fowlkes BJ. Presenilins regulate alphabeta T cell development by modulating TCR signaling. J Exp Med. 2007;204:2115–2129. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jones ME, Zhuang Y. Acquisition of a functional T cell receptor during T lymphocyte development is enforced by HEB and E2A transcription factors. Immunity. 2007;27:860–870. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jimi E, Strickland I, Voll RE, Long M, Ghosh S. Differential role of the transcription factor NF-kappaB in selection and survival of CD4+ and CD8+ thymocytes. Immunity. 2008;29:523–537. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bilic I, Ellmeier W. The role of BTB domain-containing zinc finger proteins in T cell development and function. Immunol Lett. 2007;108:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2006.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dave VP, Allman D, Keefe R, Hardy RR, Kappes DJ. HD mice: a novel mouse mutant with a specific defect in the generation of CD4(+) T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:8187–8192. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.14.8187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Keefe R, Dave V, Allman D, Wiest D, Kappes DJ. Regulation of lineage commitment distinct from positive selection. Science. 1999;286:1149–1153. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5442.1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.He X, He X, Dave VP, Zhang Y, Hua X, Nicolas E, Xu W, Roe BA, Kappes DJ. The zinc finger transcription factor Th-POK regulates CD4 versus CD8 T-cell lineage commitment. Nature. 2005;433:826–833. doi: 10.1038/nature03338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sun G, Liu X, Mercado P, Jenkinson SR, Kypriotou M, Feigenbaum L, Galera P, Bosselut R. The zinc finger protein cKrox directs CD4 lineage differentiation during intrathymic T cell positive selection. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:373–381. doi: 10.1038/ni1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang L, Wildt KF, Zhu J, Zhang X, Feigenbaum L, Tessarollo L, Paul WE, Fowlkes BJ, Bosselut R. Distinct functions for the transcription factors GATA-3 and ThPOK during intrathymic differentiation of CD4(+) T cells. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:1122–1130. doi: 10.1038/ni.1647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pai SY, Truitt ML, Ting C, Leiden JM, Glimcher LH, Ho IC. Critical Roles for Transcription Factor GATA-3 in Thymocyte Development. Immunity. 2003;19:863–875. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00328-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hernandez-Hoyos G, Anderson MK, Wang C, Rothenberg EV, Alberola-Ila J. GATA-3 expression is controlled by TCR signals and regulates CD4/CD8 differentiation. Immunity. 2003;19:83–94. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00176-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhu J, Min B, Hu-Li J, Watson CJ, Grinberg A, Wang Q, Killeen N, Urban JFJ, Guo L, Paul WE. Conditional deletion of Gata3 shows its essential function in T(H)1-T(H)2 responses. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:1157–1165. doi: 10.1038/ni1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ho IC, Tai TS, Pai SY. GATA3 and the T-cell lineage: essential functions before and after T-helper-2-cell differentiation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:125–135. doi: 10.1038/nri2476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hendriks RW, Nawijn MC, Engel JD, van DH, Grosveld F, Karis A. Expression of the transcription factor GATA-3 is required for the development of the earliest T cell progenitors and correlates with stages of cellular proliferation in the thymus. Eur J Immunol. 1999;29:1912–1918. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199906)29:06<1912::AID-IMMU1912>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ho IC, Pai SY. GATA-3 - not just for Th2 cells anymore. Cell Mol Immunol. 2007;4:15–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jenkinson SR, Intlekofer AM, Sun G, Feigenbaum L, Reiner SL, Bosselut R. Expression of the transcription factor cKrox in peripheral CD8 T cells reveals substantial postthymic plasticity in CD4-CD8 lineage differentiation. J Exp Med. 2007;204:267–272. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Muroi S, Naoe Y, Miyamoto C, Akiyama K, Ikawa T, Masuda K, Kawamoto H, Taniuchi I. Cascading suppression of transcriptional silencers by ThPOK seals helper T cell fate. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:1113–1121. doi: 10.1038/ni.1650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Komine O, Hayashi K, Natsume W, Watanabe T, Seki Y, Seki N, Yagi R, Sukzuki W, Tamauchi H, Hozumi K, Habu S, Kubo M, Satake M. The Runx1 transcription factor inhibits the differentiation of naive CD4+ T cells into the Th2 lineage by repressing GATA3 expression. J Exp Med. 2003;198:51–61. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bender TP, Kremer CS, Kraus M, Buch T, Rajewsky K. Critical functions for c-Myb at three checkpoints during thymocyte development. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:721–729. doi: 10.1038/ni1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Maurice D, Hooper J, Lang G, Weston K. c-Myb regulates lineage choice in developing thymocytes via its target gene Gata3. EMBO J. 2007;26:3629–3640. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nawijn MC, Ferreira R, Dingjan GM, Kahre O, Drabek D, Karis A, Grosveld F, Hendriks RW. Enforced expression of GATA-3 during T cell development inhibits maturation of CD8 single-positive cells and induces thymic lymphoma in transgenic mice. J Immunol. 2001;167:715–723. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.2.715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Aliahmad P, Kaye J. Development of all CD4 T lineages requires nuclear factor TOX. J Exp Med. 2008;205:245–256. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bendelac A, Savage PB. The biology of NKT cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2007;25:297–336. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kim PJ, Pai SY, Brigl M, Besra GS, Gumperz J, Ho IC. GATA-3 regulates the development and function of invariant NKT cells. J Immunol. 2006;177:6650–6659. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.10.6650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.He X, Kappes DJ. CD4/CD8 lineage commitment: light at the end of the tunnel? Curr Opin Immunol. 2006;18:135–142. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2006.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.He X, Park K, Wang H, He X, Zhang Y, Hua X, Li Y, Kappes DJ. CD4-CD8 lineage commitment is regulated by a silencer element at the ThPOK transcription-factor locus. Immunity. 2008;28:346–358. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ferrell JEJ. Self-perpetuating states in signal transduction: positive feedback, double-negative feedback and bistability. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2002;14:140–148. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(02)00314-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Germain RN. T-cell development and the CD4-CD8 lineage decision. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:309–322. doi: 10.1038/nri798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Laky K, Fowlkes B. Receptor signals and nuclear events in CD4 and CD8 T cell lineage commitment. Curr Opin Immunol. 2005;17:116–121. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2005.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Singer A. New perspectives on a developmental dilemma: the kinetic signaling model and the importance of signal duration for the CD4/CD8 lineage decision. Curr Opin Immunol. 2002;14:207–215. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(02)00323-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Brugnera E, Bhandoola A, Cibotti R, Yu Q, Guinter TI, Yamashita Y, Sharrow SO, Singer A. Coreceptor reversal in the thymus: signaled CD4+8+ thymocytes initially terminate CD8 transcription even when differentiating into CD8+ T cells. Immunity. 2000;13:59–71. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)00008-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Liu X, Bosselut R. Duration of TCR signaling controls CD4-CD8 lineage differentiation in vivo. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:280–288. doi: 10.1038/ni1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sarafova SD, Erman B, Yu Q, Van LF, Guinter T, Sharrow SO, Feigenbaum L, Wildt KF, Ellmeier W, Singer A. Modulation of coreceptor transcription during positive selection dictates lineage fate independently of TCR/coreceptor specificity. Immunity. 2005;23:75–87. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hedrick SM. Thymus lineage commitment: a single switch. Immunity. 2008;28:297–299. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ling KW, van Hamburg JP, de Bruijn MJ, Kurek D, Dingjan GM, Hendriks RW. GATA3 controls the expression of CD5 and the T cell receptor during CD4 T cell lineage development. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37:1043–1052. doi: 10.1002/eji.200636485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hayashi K, Abe N, Watanabe T, Obinata M, Ito M, Sato T, Habu S, Satake M. Overexpression of AML1 transcription factor drives thymocytes into the CD8 single-positive lineage. J Immunol. 2001;167:4957–4965. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.9.4957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Taniuchi I, Sunshine MJ, Festenstein R, Littman DR. Evidence for distinct CD4 silencer functions at different stages of thymocyte differentiation. Mol Cell. 2002;10:1083–1096. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00735-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zou YR, Sunshine MJ, Taniuchi I, Hatam F, Killeen N, Littman DR. Epigenetic silencing of CD4 in T cells committed to the cytotoxic lineage. Nat Genet. 2001;29:332–336. doi: 10.1038/ng750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Krangel MS. T cell development: better living through chromatin. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:687–694. doi: 10.1038/ni1484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wildt KF, Sun G, Grueter B, Fischer M, Zamisch M, Ehlers M, Bosselut R. The transcription factor zbtb7b promotes CD4 expression by antagonizing runx-mediated activation of the CD4 silencer. J Immunol. 2007;179:4405–4414. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.7.4405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]