Abstract

Patch-clamp recordings in single-cell expression systems have been traditionally used to study the function of ion channels. However, this experimental setting does not enable assessment of tissue-level function such as action potential (AP) conduction. Here we introduce a biosynthetic system that permits studies of both channel activity in single cells and electrical conduction in multicellular networks. We convert unexcitable somatic cells into an autonomous source of electrically excitable and conducting cells by stably expressing only three membrane channels. The specific roles that these expressed channels have on AP shape and conduction are revealed by different pharmacological and pacing protocols. Furthermore, we demonstrate that biosynthetic excitable cells and tissues can repair large conduction defects within primary 2- and 3-dimensional cardiac cell cultures. This approach enables novel studies of ion channel function in a reproducible tissue-level setting and may stimulate the development of new cell-based therapies for excitable tissue repair.

All cells express ion channels in their membranes, but cells with a significantly polarized membrane that can undergo a transient all-or-none membrane depolarization (action potential, AP) are classified as ‘excitable cells’1. The coordinated function of ion channels in excitable cells governs the generation and propagation of APs, which enable fundamental life processes such as the rapid transfer of information in nerves2 and the synchronized pumping of the heart3. For this reason, genetic or acquired alterations in ion channel function or irreversible loss of excitable cells through injury or disease (for example, stroke or heart attack) are often life threatening4,5.

Numerous ion channels (wild type (wt) or mutated) have been studied in single-cell heterologous expression systems to investigate channel structure–function relationships and link specific channel mutations found in patients to associated diseases, such as cardiac arrhythmias or epilepsy6. Typically, the potential implications of these single-cell studies for the observed tissue- or organ-level function are only speculated, often through the use of tissue-specific computational models7,8. Similarly, experimental studies of AP conduction in primary excitable tissues and cell cultures are often limited by low reproducibility, heterogeneous structure and function, a diverse and often unknown complement of endogenous channels, and the non-specific action of applied pharmaceuticals. We therefore set out to develop and validate a simplified, well-defined and reproducible excitable tissue system that would enable direct quantitative studies of the roles that specific ion channels have in AP conduction.

Extensive electrophysiological research over the last century1,9 has revealed that the initiation, shape and transfer of APs in excitable cells are regulated by an extraordinarily diverse set of ion channels, pumps and exchangers. Yet, the classic Hodgkin and Huxley bioelectric model of a giant squid axon10 and other simplified models of biological excitable media11,12 suggest that only a few membrane channels are sufficient to sustain cellular excitability and AP conduction. On the basis of these theoretical concepts, we hypothesized that a small number of targeted genetic manipulations could transform unexcitable somatic cells into an electrically active tissue capable of generating and propagating APs.

In this study, we selected a minimum set of channel genes that, upon stable expression in unexcitable cells, would yield significant hyperpolarization of membrane potential, electrical induction of an all-or-none AP response and robust intercellular electrical coupling to support uniform and fast AP conduction over arbitrarily long distances. We designed experiments to thoroughly characterize the electrophysiological properties of these genetically engineered cells including pharmacological manipulations to establish the roles of each of the expressed channels in membrane excitability and impulse conduction. Furthermore, we explored whether these cells could be used to generate biosynthetic excitable tissues with the ability to restore electrical conduction within large cm-sized gaps in primary excitable cell cultures.

Results

Experimental approach to engineering excitable cells

We tested the hypothesis that human unexcitable somatic cells can be genetically engineered to form an autonomous source of electrically excitable and conducting cells through the stable expression of three genes encoding: the inward-rectifier potassium channel (Kir2.1 or IRK1, gene KCNJ2)13, the pore-forming α-subunit of the fast voltage-gated cardiac sodium channel (Nav1.5 or hH1, gene SCN5A)14 and the connexin-43 gap junction (Cx43, gene GJA1)15. These three channels have critical roles in the generation and propagation of electrical activity in the mammalian heart16,17.

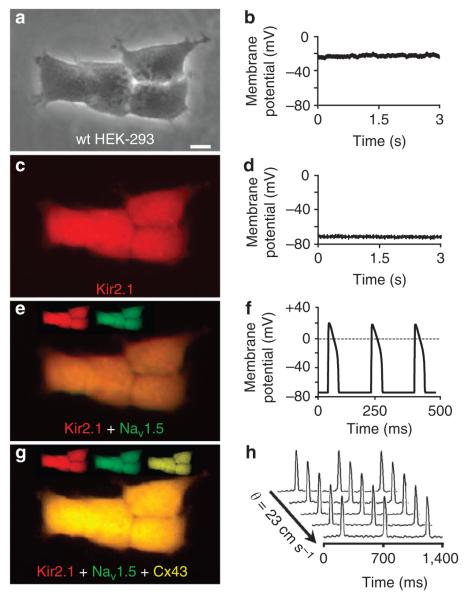

To facilitate the visual identification and monoclonal selection of stable cell lines, we constructed three bicistronic plasmids designed to express each channel (Kir2.1, Nav1.5 or Cx43) with a unique fluorescent reporter18 (mCherry, green fluorescent protein (GFP) or mOrange, respectively) and the puromycin resistance (PacR) gene (Supplementary Fig. S1). The human embryonic kidney 293 (HEK-293) cell line was utilized as a proof-of-concept unexcitable somatic cell source based on its low levels of endogenous membrane currents (for example, outwardly rectifying potassium currents19), uniform shape and growth, and extensive use as a heterologous expression system for studies of ion channel function20. Like most unexcitable cells, wt HEK-293 cells (Fig. 1a) exhibited a relatively depolarized resting membrane potential (RMP) of − 24.4 ± 0.8 mV ( ± s.e.m.; n = 10 cells; Fig. 1b). In contrast, the RMP of excitable cells is highly negative due to the action of constitutively open and/or inwardly rectifying potassium channels such as Kir2.1 (ref. 21).

Figure 1. Stable coexpression of three genes confers impulse conduction in unexcitable cells.

wt HEK-293 cells (a), like most unexcitable cells, have a relatively depolarized resting potential (b). scale bar, 10 μm. stable expression of Kir2.1-IREs-mCherry (c) introduces inward-rectifier potassium current in the cell yielding membrane hyperpolarization (d). Coexpression of nav1.5–IREs–GFP (e) introduces fast sodium current that allows firing of regenerative APs on stimulation (f). The additional expression of Cx43–IREs–morange (g) enhances cell–cell coupling and enables fast and uniform AP propagation (h) in multicellular tissues. θ, Velocity of AP propagation.

IK1 and INa expression enables AP generation

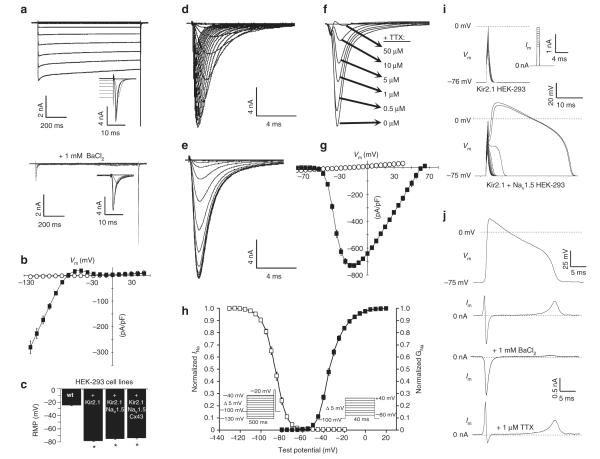

To induce significant membrane hyperpolarization in the wt HEK-293 cells, we stably transfected them with a plasmid encoding Kir2.1–IRES–mCherry and derived ‘Kir2.1 HEK-293’ monoclonal lines from cells that displayed bright mCherry fluorescence (Fig. 1c). These stable cell lines exhibited robust barium-sensitive inward-rectifier potassium current, IK1 (Supplementary Fig. S2 and Fig. 2a,b), and hyperpolarized RMP values (Fig. 2c) similar to those of primary excitable cells1. A hyperpolarized RMP is required for cellular excitability, as it allows a sufficient number of voltage-gated sodium channels to open on membrane depolarization and initiate a regenerative AP16,17. In addition, a hyperpolarized RMP, as a natural state of excitable cells, has been shown to distinctly affect the expression level and kinetics of ion channels22,23.

Figure 2. Stable expression of Kir2.1 and Nav1.5 yields membrane excitability in HEK-293 cells.

(a) Kir2.1 + nav1.5 HEK-293 cells exhibited BaCl2-sensitive IK1. Activation of Ina also occurred at the end of several IK1 test pulses (insets). (b) steady-state IK1–V curves obtained from Kir2.1 + nav1.5 (black squares; n = 9) and wt (white circles; n = 6) HEK-293 cells. (c) Expression of IK1 yielded significant hyperpolarization of RmP (n = 10–27). Representative recordings of Ina activation (d), inactivation (e) and TTX block (f) in Kir2.1 + nav1.5 HEK-293 cells. (g) Peak Ina–V curves obtained from Kir2.1 + nav1.5 (black squares; n = 6) and wt HEK-293 (white circles; n = 6) cells. (h) Voltage dependence of Ina steady-state activation (black squares; n = 6) and inactivation (white squares; n = 6). (i) Current pulses (inset) induced an all-or-none AP response in Kir2.1 + nav1.5 but not in Kir2.1 HEK-293 cells.

(j) AP-clamp recordings in Kir2.1 + nav1.5 HEK-293 cells revealed the individual contributions of Ina and IK1 to the AP. Error bars denote mean ± s.e.m.;

*P < 0.001; #P < 0.01; and ^P < 0.05. All recordings shown were made using the same monoclonal Kir2.1 + nav1.5 HEK-293 cell line.

To generate electrically excitable cells, we introduced a voltage-gated sodium channel, Nav1.5, into a monoclonal Kir2.1 HEK-293 cell line by transfection of a plasmid encoding Nav1.5–IRES–GFP (Supplementary Fig. S1b). We then selected cells with strong GFP expression to derive monoclonal ‘Kir2.1 + Nav1.5 HEK-293’ cells (Fig. 1e) that generated large, fast-inactivating sodium current, INa (Fig. 2d-g). This current showed cardiac-specific sensitivity to block by tetrodotoxin (TTX; Fig. 2f) and characteristic voltage-dependent steady-state activation and inactivation properties14 (Fig. 2h). Importantly, much like primary excitable cells, the HEK-293 cells genetically engineered to stably express both IK1 and INa developed membrane excitability, wherein on reaching an excitation threshold by current injection, they reproducibly fired an ‘all-or-none’ AP (Figs 1f and 2i).

To dissect the contributions of IK1 and INa to an AP time course in these cells, we utilized the AP-clamp technique24 (Fig. 2j). As expected from the IK1 current–voltage relationship (Fig. 2b), outward potassium current activated above the resting potential during the AP upstroke in an attempt to maintain membrane hyperpolarization and also during AP plateau negative to − 25 mV to bring the cell back to rest. Inward INa activated only during the AP upstroke, followed by rapid inactivation (Fig. 2j).

Cx43 expression enables rapid AP propagation

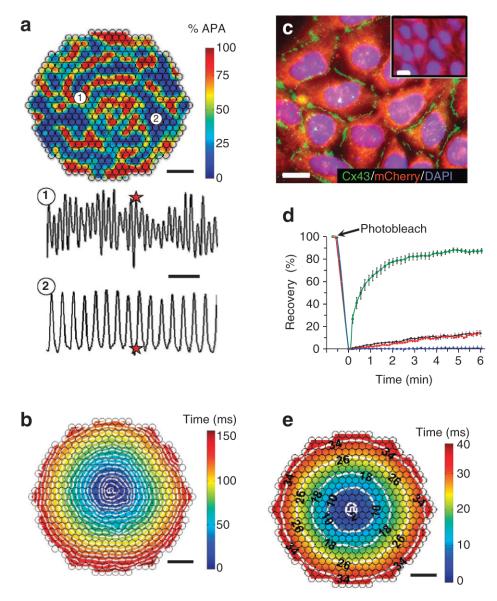

We further tested whether the excitable Kir2.1 + Nav1.5 HEK-293 cells can support active electrical conduction when cultured in confluent two-dimensional (2D) cell networks. Optical mapping of transmembrane voltage in these cultures, however, revealed either uncoordinated aperiodic electrical activity caused by slowly moving and colliding excitation waves25 or slow AP conduction (5.6 ± 0.2 cm s − 1 ( ± s.e.m.; n = 4); Fig. 3a,b). This slow or unorganized AP propagation in the Kir2.1 + Nav1.5 HEK-293 cells was supported by weak endogenous cell coupling (Supplementary Fig. S3a,b) that likely originated from expression of connexin-45 (refs 26, 27) rather than connexin-43 gap junctions (Fig. 3c, inset)27,28. Therefore, to enable rapid and uniform AP propagation in the Kir2.1 + Nav1.5 HEK-293 cells, we stably transfected the monoclonal line characterized in Figure 2 with a plasmid encoding Cx43–IRES–mOrange (Supplementary Fig. S1c).

Figure 3. Stable overexpression of Cx43 in Kir2.1 + Nav1.5 HEK-293 cells yields enhanced intercellular coupling and permits rapid AP propagation.

(a) At the start of recording, confluent isotropic 2D networks (monolayers) of monoclonal Kir2.1 + nav1.5 cells usually exhibited high-frequency unorganized electrical activity caused by numerous, slowly moving, splitting and colliding waves. shown is one instant of optically recorded transmembrane voltage. Colour bar indicates percent AP amplitude (% APA). Different sites in the monolayer (for example, 1 and 2) activated at different rates (bottom panel), demonstrating the lack of spatial synchrony in activation. Red stars denote the time at which the transmembrane voltage frame (top panel) was taken. scale bars indicate 3 mm (top panel) and 250 ms (bottom panel). (b) on successful termination of all unorganized activity by a strong field shock, low-frequency ( < 10 Hz) point stimulation from the centre (white pulse sign) yielded slow conduction through the weakly coupled Kir2.1 + nav1.5 HEK-293 cells. shown is a colour-coded map of cell activation, with white isochrone lines drawn at every 8 ms. scale bar, 3 mm. (c) Following stable Cx43 overexpression, the derived Kir2.1 + nav1.5 + Cx43 HEK-293 cells formed abundant intercellular Cx43 gap junctions (green), which were not detected in wt HEK-293 cells (inset). scale bars, 10 μm. (d) Fluorescence recovery after photobleaching shows increased functional coupling in monoclonal Kir2.1 + nav1.5 + Cx43 (Ex-293) cells (green squares; n = 7) compared with wt HEK-293 (black diamonds; n = 6) and Kir2.1 + nav1.5 HEK-293 (red triangles; n = 5) cells. Palmitoleic acid (PA) inhibited junctional coupling and fluorescence recovery (blue circles; n = 6). Error bars denote s.e.m. (e) Pacing in the centre of an Ex-293 monolayer elicited rapid and uniform AP spread (see supplementary movie 1). scale bar, 3 mm. Isochrones of cell activation (white lines) are labelled in milliseconds. small black circles in a, b, and e denote 504 optical recording sites. DAPI, 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole.

We derived ‘Kir2.1 + Nav1.5 + Cx43 HEK-293’ monoclonal cell lines with bright mOrange fluorescence (Fig. 1g) and abundant expression of Cx43 gap junctions at cell–cell interfaces (Fig. 3c). One of these excitable and well-coupled Kir2.1 + Nav1.5 + Cx43 HEK-293 monoclonal lines was named ‘Excitable-293’ (Ex-293). Functional intercellular coupling in Ex-293 cells was dramatically enhanced compared with endogenous HEK-293 coupling, as demonstrated by fluorescence recovery after photobleaching27,29 (Fig. 3d, Supplementary Fig. S3a,b and Supplementary Table S1) and dual whole-cell patch clamping30 (Supplementary Fig. S3c,d). The average gap junctional conductance in Ex-293 cell pairs (134.1 ± 14.0 nS ( ± s.e.m.; n = 12)) was comparable with that measured in isolated pairs of neonatal rat28 or adult canine31 cardiomyocytes. This Ex-293 monoclonal line, which has retained stable electrophysiological properties (Supplementary Table S2) after multiple freeze–thaw cycles and more than 40 cell passages, was further utilized for the generation and characterization of biosynthetic excitable 2D and three-dimensional (3D) cell networks.

When electrically stimulated, confluent 2D networks (monolayers) of randomly oriented Ex-293 cells supported rapid, spatially uniform AP propagation (Fig. 3e, Supplementary Fig. S4a and Supplementary Movie 1) at excitation rates of up to 26.5 Hz and basic conduction velocities (CVs) of 23.3 cm s − 1. The dependence of CV in Ex-293 monolayers on the spatial distribution of gap junctions was explored by utilizing topographical and biochemical cues (microgrooved and micropatterned substrates32) to elongate and align Ex-293 cells within confluent anisotropic networks and thin strands (Supplementary Fig. S4b,c and Supplementary Movie 1). As expected, AP conduction was found to be faster along but slower across the aligned cells, as compared with non-aligned cells (longitudinal, transverse and isotropic velocity in Supplementary Table S2), due to the directional differences in the number of gap junctions (and cell–cell contacts) per unit length3.

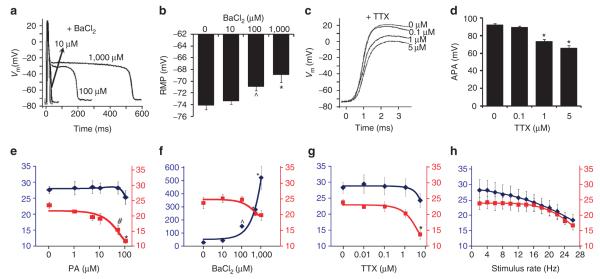

Expressed channels govern Ex-293 electrical function

We further characterized how the expressed ion channels contribute to AP conduction in Ex-293 monolayers by using specific channel blockers. At the cellular level (assessed by sharp microelectrode recordings), gradual inhibition of IK1 by increasing doses of barium chloride (BaCl2) significantly increased AP duration (APD80, Fig. 4a, Supplementary Fig. S5a), depolarized RMP (Fig. 4b) and decreased the AP upstroke velocity (Supplementary Fig. S5b), confirming the important role of IK1 in AP repolarization, maintenance of RMP, and through the maintenance of the RMP, regulation of INa availability and AP upstroke. Gradual inhibition of INa by increasing doses of TTX, on the other hand, significantly decreased AP duration (APD80, Supplementary Fig. S5c), upstroke velocity (Fig. 4c and Supplementary Fig. S5d) and amplitude (Fig. 4d) without a significant change in RMP (not shown), thereby confirming the prominent role of INa in AP depolarization, and in conjunction with its opposing action on IK1, regulation of AP duration.

Figure 4. Effects of channel blockers on the shape and conduction of APs in Ex-293 monolayers.

(a–d) Dose-dependent effects of IK1 or Ina inhibition on the shape of propagated APs, recorded by sharp microelectrodes during 1-Hz stimulation. Inhibition of IK1 by increasing doses of BaCl2 significantly prolonged AP duration (representative cell shown in a) and depolarized RmP (b; n = 11–20). The rapid AP repolarization at high doses of BaCl2 was likely contributed by the endogenous outward currents of HEK-293 cells (supplementary Fig. s2). Inhibition of Ina by increasing doses of TTX decreased AP upstroke (representative cell shown in c) and amplitude (d; n = 8–34). (e–g) Dose-dependent effects of specific channel blockers on CV (red squares) and AP duration (APD80, blue diamonds) in optically mapped Ex-293 monolayers during 1-Hz stimulation (n = 5–7). Left (blue) and right (red) y axes correspond to APD80 (ms) and CV (cm s − 1), respectively. Highest doses shown are before conduction blocks occurred. (h) Effect of increased stimulation rate on CV (red squares) and APD80 (blue diamonds). The rate was increased in 1-min steps, and data from all recording sites were averaged during the last 2 s of each step (n = 5 monolayers). Error bars denote mean ± s.e.m.; *P < 0.001; #P < 0.01; and ^P < 0.05 vs corresponding drug-free values. Additional data for the effects of channel inhibition on AP shape and conduction are shown in supplementary Figures s5 and s6.

At the tissue level (assessed by macroscopic optical mapping of transmembrane potentials), inhibition of Kir2.1, Nav1.5 or Cx43 channels by increasing doses of BaCl2, TTX or palmitoleic acid (PA), respectively, yielded gradual slowing of propagation (Fig. 4e-g) until conduction failure, thus demonstrating the critical roles of all the three expressed channels in AP conduction. Similarly, reduction of INa by stimulation at progressively increasing rates33 yielded a decrease in both CV and APD80 (Fig. 4h). Furthermore, specific modulations of Nav1.5 channel activity by lidocaine or flecainide22,34 showed distinct effects on CV and APD80 in Ex-293 monolayers during steady 10-Hz stimulation (Supplementary Fig. S6a).

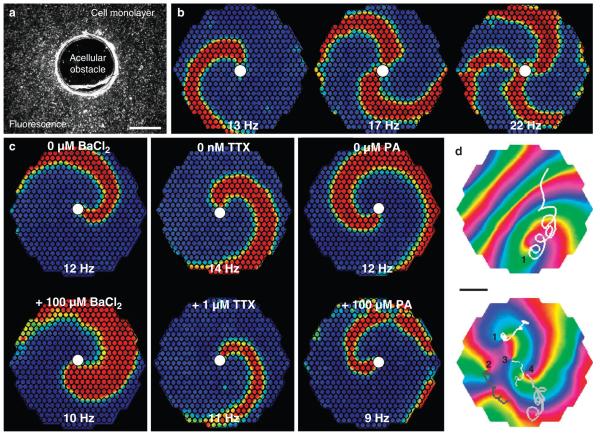

In addition to stimulated AP propagation, confluent Ex-293 monolayers supported self-sustained stationary (anchored to a small acellular obstacle, Fig. 5a–c) or freely drifting (Fig. 5d) spiral waves (Supplementary Movie 2), as is characteristic of various excitable media35 including cardiac tissue36. The average rotational rates of single anchored and freely drifting spirals were 13.8 ± 1.1 Hz ( ± s.e.m.; n = 5) and 18.8 ± 1.6 Hz ( ± s.e.m.; n = 4), respectively. The application of BaCl2, PA or different inhibitors of INa during the rotation of a stationary spiral wave slowed the rotation rate and eventually terminated all electrical activity in Ex-293 monolayers (Fig. 5c and Supplementary Fig. S6b).

Figure 5. Spiral waves in Ex-293 monolayers.

(a) Coverslips with a 1.6-mm punched central hole were used to generate monolayers with an acellular obstacle. scale bar, 1 mm. (b) short bursts of rapid point stimulation ( > 25 Hz) from the monolayer periphery yielded formation of single or multiple spiral waves that anchored to the central obstacle (white circle) and rotated at shown rates. (c) monolayers with a single stable anchored spiral were exposed to BaCl2, TTX or PA to decrease IK1, Ina or gap junctional coupling, respectively. The application of each blocker slowed spiral rotation, with BaCl2 also causing an increase in AP duration (as evidenced by an increase in spiral wave width). Higher doses of the three compounds eventually terminated the spiral activity. Frames in b and c show colour-coded optically recorded transmembrane voltage (blue to red denote rest to peak of AP), whereas small circles within these frames denote optical recording sites. (d) In the absence of a central obstacle, rapid stimulation occasionally caused the formation of single (top panel, shown in an anisotropic monolayer) or multiple (bottom panel shown in an isotropic monolayer) freely drifting spiral waves. Drift trajectories (overlay lines) of individual spiral tips (labelled by numbers) were tracked using phase map analysis and shown over a period of ~400 ms.

The colours in the phase map denote different phases of the AP, with red colour showing the AP wave front. scale bar, 4 mm. Representative movies of spiral waves are compiled in supplementary movie 2.

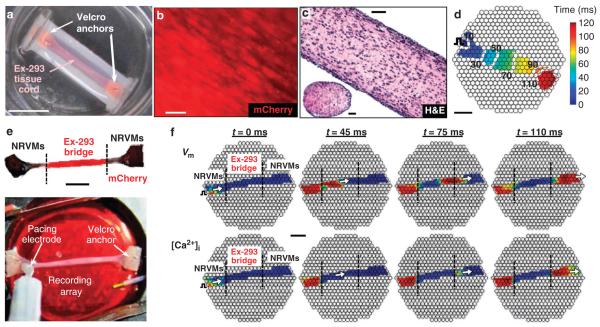

Ex-293 cells form 3D biosynthetic excitable tissues

To demonstrate our ability to generate de novo functional excitable tissues, we cultured Ex-293 cells within fibrin-based hydrogel constructs37. Using elastomeric molds and Velcro anchors, we created cm-sized 3D tissue cords (Fig. 6a). The Ex-293 cells in tissue cords compacted the hydrogel, aligned along the direction of passive tension imposed by the two Velcro anchors (Fig. 6b,c), and electrically coupled to form 3D-engineered tissues that supported uniform AP propagation (Fig. 6d and Supplementary Movie 3), with an average CV and APD80 of 18.1 ± 1.7 cm s − 1 and 33.5 ± 1.2 ms, respectively ( ± s.e.m.; n = 7 tissue cords).

Figure 6. Ex-293 cells form 3D biosynthetic excitable tissues and establish active electrical connection between remote regions in a 3D cardiac network.

(a) A 3D tissue cord made by casting a mixture of Ex-293 cells and fibrin hydrogel within a tubular mold. scale bar, 1 cm. (b) Longitudinal alignment of Ex-293 cells under passive tension inside a tissue cord. scale bar, 50 μm. (c) Longitudinal and transverse histological sections of an Ex-293 tissue cord cultured for 4 weeks and stained with haematoxylin and eosin (H&E). scale bars, 100 μm. (d) Point pacing at the periphery of an Ex-293 tissue cord (pulse sign) elicited rapid and uniform AP propagation (see supplementary movie 3). Isochrones of cell activation (white lines) are labelled in milliseconds. small black circles denote optical recording sites. scale bar, 3 mm. (e) A cocultured-3D tissue cord with peripheral nRVm regions connected by a 1.3-cm-long central Ex-293 bridge (superimposed composite images of phase contrast and mCherry fluorescence). scale bar, 5 mm. The optical recording array was placed underneath the cord (bottom panel). (f) stimulation of a proximal nRVm region (left panel) generated a wave of transmembrane voltage (Vm) that spread (as shown by white arrow) through the Ex-293 tissue bridge and into the distal nRVm region (top frames). nRVm (but not Ex-293) excitation also yielded generation of intracellular calcium ([Ca2 + ]i) transients (bottom frames). Frames show colour-coded Vm or [Ca2 + ]i optically recorded at times shown above (blue to red indicate baseline to peak signal, respectively). scale bar, 3 mm. Additional proof-of-concept examples where remote nRVm regions in 2D cultures are seamlessly connected by active AP propagation through Ex-293 cells are shown in supplementary Figure s7 and supplementary movie 4.

Ex-293 cells restore active conduction in cardiac cultures

We have previously demonstrated that unexcitable HEK-293 cells genetically engineered to express Cx43 can electrically couple with primary neonatal rat ventricular myocytes (NRVMs)27 and passively connect them (with a long delay) over distances of up to a few hundred microns32. Ex-293 cells, on the other hand, both formed Cx43 gap junctions with NRVMs (Supplementary Fig. S7a) and, through fast active propagation, seamlessly connected remote (cm apart) cardiomyocyte regions in both 2D (Supplementary Fig. S7b,c and Supplementary Movie 4) and 3D (Fig. 6e,f) NRVM networks. Thus, biosynthetic excitable cells and tissues could potentially act as actively conducting ‘fillers’ to restore fast and uniform AP propagation in diseased, slow-conducting excitable tissues.

Discussion

This study introduces a methodology for the de novo generation of actively conducting excitable tissues from unexcitable somatic cells by the stable forced expression of only three membrane channels. Specifically, through a stepwise experimental approach (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. S1), we showed that genetic engineering of: significant membrane polarization by introduction of Kir2.1 channels; rapid depolarization capacity by introduction of Nav1.5 channels; and robust intercellular coupling by overexpression of Cx43 gap junctions synergistically enabled electrical excitability and conduction in HEK-293 cells.

Previously, Hsu et al.38 transiently expressed voltage-gated sodium (Nav1.2) and potassium (Shaker H4) channels in CHO cells, but because the average RMP of these cells was − 26.8 mV, APs could be induced only under electronically applied current-clamp hyperpolarization. More recently, Cho et al.39 have transiently expressed the Kir2.1 channel and a slow bacterial sodium channel (NaChBac) in HEK-293 cells to yield slow rising and long APs in 5/31 cells, whereas Abraham et al.40 have expressed Cx43 to promote electrical coupling of skeletal myotubes and decrease their arrhythmogenic effects in cocultures with cardiomyocytes. We, on the other hand, have created stable excitable cell lines with reproducible electrical properties including fast rising (dV/dtmax≈150 V s − 1) and rapidly propagating (CV≈23 cm s − 1) APs. As these cells can be assembled into autonomous, actively conducting tissues, we were able to pharmacologically dissect the specific roles of each expressed channel in the dynamics of AP conduction and demonstrate the ability of these biosynthetic tissues to restore fast conduction within arbitrary size gaps in cardiomyocyte cultures.

Single unexcitable cells have been traditionally used in heterologous expression systems in conjunction with patch-clamp recordings to isolate and study the function of specific ion channels41. The biosynthetic excitable cells described in this study can be additionally utilized as a tissue–scale heterologous expression system to directly investigate not only specific channel activity in single cells but also AP conduction in multicellular networks fabricated from these same cells. For example, in this study, we have isolated and quantified the role of Nav1.5 in AP generation and conduction during control conditions as well as different pharmacological challenges in both single cells and cell networks. In general, biosynthetic excitable tissues as a well-defined, reproducible and versatile platform could complement studies in primary excitable cells by helping elucidate the distinct roles that specific ion channels and gap junctions, their mutations42–45 auxiliary subunits46, or accessory proteins47,48 have in tissue-level electrophysiology. Furthermore, the potential to efficiently manipulate the gene expression and spatial organization of engineered cells within biosynthetic tissues can allow for well-controlled experiments to validate and advance existing theoretical and computational models of AP conduction as well as facilitate the design of robust and reproducible cell-based biosensors49.

Importantly, we also performed proof-of-concept in vitro studies showing that biosynthetic excitable cells and tissues can establish a fast and seamless electrical connection between distant cardiomyocytes. The implantation of stem cells or somatic cells with genetically engineered electrical properties has been proposed as a potential strategy to improve compromised electrical function in the heart50–53. For example, unexcitable cells with engineered potassium channels have been applied to locally modify cardiac conduction through coupling with cardiomyocytes54. However, because of their unexcitable nature, these cells would still fail to propagate over distances larger than a few hundred microns32,55. In contrast, the use of autonomously conducting biosynthetic cells with basic electrical properties tailored to mimic those of the host tissue could allow functional repair of arbitrary size conduction defects. For example, slow tortuous conduction at the site of myocardial infarct56 could be enhanced by implanting biosynthetic excitable cells or genetically modifying endogenous fibroblasts to establish direct paths of fast AP propagation. For potential clinical use, however, highly proliferative HEK-293 cells would have to be replaced by another contact-inhibited, terminally differentiated and readily accessible cell source.

Overall, we believe that our approach not only opens the door to novel studies of electrical conduction but also, through further integration of electrophysiology, synthetic biology and tissue engineering, the development of new treatments for excitable tissue disorders.

Methods

Cloning of rat connexin-43 gene (GJA1)

Total RNA was extracted and purified from isolated NRVMs (Qiagen, RNeasy Kit). Reverse transcription with oligo(dT) primers was performed to synthesize first-strand complementary DNA (Bioline, cDNA Synthesis Kit). The cDNA was used as the template in a standard PCR reaction. PCR primers were designed based upon the published coding sequence for rat connexin-43 (GenBank no. NM_012567). The amplified PCR product was verified by nucleotide sequencing and subcloned into the pCMV5(CuO)–IRES–mOrange expression plasmid.

Generation of engineered cell lines

The human KCNJ2, SCN5A and rat GJA1 cDNAs were subcloned into a bicistronic expression vector (pCMV5(CuO)–IRES– GFP, Qbiogene). The genes encoding mCherry and mOrange18 were used to replace GFP in the KCNJ2 and GJA1 plasmids, respectively. HEK-293 cells (ATCC, CRL-1573) were cultured, transfected and selected for stable expression using previously described methods27. The Ex-293 line was established by three successive single-plasmid (Kir2.1, Nav1.5 and then Cx43) transfections, with monoclonal isolation and expression analysis before each transfection.

Whole-cell membrane current recordings

HEK-293 cells were gently trypsinized and plated onto clean glass coverslips for recording. Patch electrodes were fabricated with tip resistances of 0.8–1.8 MΩ (for INa) or 1.5–3.5 MΩ (for IK1, AP, current or dual clamp) when filled with internal patch solutions. Whole-cell currents were recorded at room temperature using the Multiclamp 700B amplifier (Axon Instruments), filtered with a 10-kHz Bessel filter, digitized at 40 kHz and stored on a computer. Data was acquired and analyzed using WinWCP software (John Dempster, University of Strathclyde). The internal and external solutions and voltage-clamp protocols for recording of INa and IK1 were similar to other published studies33,57.

Whole-cell membrane voltage and AP voltage-clamp recordings

Cell intracellular potential was recorded at room temperature in current-clamp mode (no holding current) in response to 1-ms depolarizing current steps (from 0.5 nA to 2 nA in 0.1-nA increments) in an attempt to elicit an all-or-none AP response. Extracellular bath solution (Tyrode’s) consisted of (mM) 135 NaC1, 5.4 KCl, 1.8 CaCl2, 1.0 MgCl2, 0.33 NaH2PO4, 5 HEPES and 5 glucose (pH 7.4). The membrane current during the course of AP was accessed using the AP-clamp technique24, in which a previously recorded AP waveform (measured in an excitable Ex-293 monolayer at 35 °C with a sharp electrode) was used as the stimulus protocol in whole-cell voltage-clamp mode. Recorded currents in the presence of 1 mM BaCl2 or 5 μM TTX reflected respective contributions of INa and IK1 to the AP waveform.

Dual whole-cell patch-clamp recordings

HEK-293 cell pairs that were formed in sparsely plated 2-day cultures were used for dual whole-cell measurement of gap junctional conductance, as previously described30. Patch electrodes (1.5–3.5 MΩ resistance) were filled with a CsCl-containing solution to block endogenous potassium currents. Each cell in the pair was clamped by a separate patch electrode to a 0-mV holding potential. A 20-mV depolarizing (8-s long) pulse was then applied to one of the two cells. Gap junctional conductance (Gj) was then calculated by dividing the resulting junctional current by the transjunctional voltage step ( + 20 mV) after accounting for the uncompensated series resistance in each electrode58.

Sharp intracellular recordings

HEK-293 monolayers were placed into a temperature-controlled (35 °C) chamber mounted onto an inverted microscope (Nikon, Eclipse TE2000), perfused with warm Tyrode’s solution and stimulated at 1 Hz by a bipolar point electrode connected to a Grass Stimulator (Grass Technologies). Propagated APs were recorded 6 mm away from the stimulus site using a sharp intracellular electrode (50–80 MΩ tip resistance), as previously described27. Data was low-pass filtered through a 4.5-kHz Butterworth filter, sampled at 20 kHz using a Multiclamp 700B amplifier (Axon Instruments) and recorded using WinWCP or Chart software. RMP, AP amplitude, duration at 80% repolarization (APD80) and maximum upstroke velocity (dVm dt − 1) were measured using a custom-made MATLAB program59.

Fluorescence recovery after photobleaching

Functional coupling in HEK-293 cells was assessed using fluorescence recovery after photobleaching29, as described previously27. HEK-293 monolayers were loaded with Calcein AM dye (Molecular Probes, 0.5 μM, 20 min at 37 °C) and washed in phosphate-buffered saline. The target cell was photobleached with a 488-nm Argon laser and imaged every 10 s for the following 6 min using an upright confocal microscope (Zeiss, LSM 510). The time course of recovery of calcein fluorescence in the target cell (by inflow from the adjacent cells) was fit by an exponential curve using custom-made MATLAB software. The calculated recovery rate constant29 for each sample was normalized by the number of cells in direct contact with the target cell.

Fabrication of excitable 2D HEK-293 networks

Isotropic excitable HEK-293 (Ex-293) monolayers were made by plating 2.5×105 cells onto fibronectin-coated (15 μg ml − 1, Sigma) Aclar (Electron Microscopy Sciences) coverslips (22-mm diameter) and culturing to confluence. Anisotropic Ex-293 monolayers and thin strands were made by culturing cells on fibronectin-coated microgrooved films (Edmund Industrial Optics) or microcontact-printed fibronectin lines32, respectively.

Fabrication of 3D tissue constructs

Fibrin-based hydrogel solution was made using bovine fibrinogen (2 mg ml − 1, Sigma), bovine thrombin (0.4 U mg − 1 fibrinogen, Sigma) and Matrigel (10% v/v, Becton Dickinson), as previously described37. The 3D tissue cords were fabricated by casting 7×106 cells per ml hydrogel solution inside a 2.5-cm-long silicon half-tube with two Velcro felts (3M Company; St Paul, MN) pinned at the tube ends. The Velcro anchored the hydrogel and, by establishing passive tension during cell-mediated gel compaction, facilitated cell spreading and contact. Aminocaproic acid (1 mg ml − 1, Sigma) was added to the culture medium to prevent degradation of fibrin by serum plasmin. To create an NRVM tissue cord with a central Ex-293 bridge, three tips of a multichannel pipette were used to simultaneously inject Ex-293/hydrogel solution in the middle and NRVM/hydrogel solutions at the two ends of the silicon half-tube. With time in culture, NRVMs and Ex-293 cells spread, aligned and coupled while maintaining distinct spatial boundaries, as identified by fluorescence imaging for GFP, mCherry and mOrange.

Optical mapping of impulse propagation

The 2D cell networks and 3D tissue constructs were stained with a voltage-sensitive dye, Di-4 ANEPPS (10 μM, 5–7 min), or a non-ratiometric Ca2 + -sensitive dye, X-Rhod-1 (3 μM, 45 min). Transmembrane voltage and intracellular Ca2 + concentration, [Ca2 + ]i, were optically mapped with 504 optical fibres arranged into a 20-mm diameter hexagonal bundle (Redshirt Imaging), as previously described32,59. Fluorescence signals were converted to voltage by photodiodes and acquired at a 2.4-kHz sampling rate with macroscopic (750 μm) or microscopic (37.5 μm, ×20 magnification) spatial resolution. To prevent motion artefacts, cells were exposed to 10-μM blebbistatin (Sigma). An XYZ-micropositioned platinum point electrode was used to initiate electrical conduction at progressively higher pacing rates (1–30 Hz in 30-s steps)60. Data were processed, displayed and analyzed using custom-made MATLAB software. The longitudinal and transverse CV, velocity anisotropy ratio, APD80, maximum capture rate (where each stimulus was still followed by an AP response) and CV and APD80 rate dependence curves were derived, as previously described59,60.

Studies of spiral activity

Spiral waves were induced by rapid (25–30 Hz) burst pacing from the edge of a cell monolayer and optically mapped60. For anchored (anatomical) spiral wave studies, a 1.6-mm circular obstacle was punched out from the centre of a coverslip before cell seeding. Spiral rotational rate was calculated by averaging activation rate from multiple sites at the coverslip periphery. Phase map and singularity analyses (with 15-ms time delay) were used to track the tip trajectory of drifting spiral waves25,60. During perfusion of channel inhibitors, rotational rate, wave unpinning and changes in spiral wave path length were documented until termination of reentrant activity.

Pharmacological studies

TTX (Sigma), BaCl2 (Alfa Aesar) and PA (Sigma) were added to extracellular bath solution during patch clamping or optical mapping (1 Hz, 1.2× threshold stimulation in monolayers) recordings to selectively inhibit INa, IK1 and gap junctional coupling, respectively. Recordings with lidocaine (50 μM, Sigma) or flecainide (10 μM, Sigma) were performed during 40 pulses at 10-Hz stimulation. All recordings using pharmacological modulation were started 5 min after drug application.

Immunostaining

Cells were immunostained, as previously described27. Anti-sarcomeric α-actinin (Sigma, EA-53 mouse monoclonal) and anti-connexin-43 (Zymed, rabbit polyclonal) primary antibodies were applied overnight at 4 °C. Secondary Alexa Fluor 488 (chicken anti-rabbit) and Alexa Fluor 594 (chicken anti-mouse) antibodies were applied for 1 h at room temperature. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (Sigma). All fluorescent images were acquired, pseudo-coloured and processed using IPLab (BioVision Technologies), as previously described27. Tissue bundles were fixed in 4% PFA overnight, paraffin embedded, cut into 5-μm-thick transverse and longitudinal sections, stained with haematoxylin & eosin (Duke Pathology Department) and imaged using an inverted microscope (Nikon, TE2000) and NIS-Elements software (Nikon).

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± s.e.m. and were evaluated for statistical significance using linear regression or an analysis of variance (one-way, α-factor of 0.05), followed by Tukey’s post hoc test for multiple comparisons. Statistical significance was defined as ^P < 0.05, #P < 0.01 and *P < 0.001.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure S1 | Summary of experimental approach. (a) Unexcitable wild-type HEK-293 cells were transfected with the Kir2.1-IRES-mCherry plasmid and monoclonal lines were derived from cells that exhibited high mCherry fluorescence intensity. These lines also exhibited strong inward rectifying potassium current (IK1) and a hyperpolarized resting membrane potential. (b) Subsequently, the Nav1.5-IRES-GFP plasmid was transfected into a Kir2.1 HEK-293 monoclonal cell line. The derived monoclonal lines that expressed strong GFP fluorescence also exhibited robust fast inward sodium current (INa) and the ability to fire regenerative action potentials (APs) upon electrical stimulation. (c) Finally, the Cx43-IRES-mOrange plasmid was transfected into a Kir2.1+Nav1.5 HEK-293 monoclonal cell line to derive Kir2.1+Nav1.5+Cx43 HEK-293 monoclonal lines with strong mOrange fluorescence and abundant expression of Cx43 gap junctions at cell borders. Upon electrical stimulation, multicellular networks made from these lines supported fast and uniform action potential propagation. This proof-of-concept strategy demonstrates that unexcitable human cells can be converted into novel electrically excitable and conductive cell sources for the creation of functional excitable tissues.

Supplementary Figure S2 | IK1 expression in engineered HEK-293 cell lines. (a) Representative whole-cell voltage clamp IK1 recording in a HEK-293 cell stably transfected with Kir2.1 compared to wild-type (wt) HEK-293 cells. Bottom panel shows close-up of endogenous currents elicited in a wt HEK-293 cell during application of the same voltage pulse protocol (top panel). (b) Resulting steady state IK1-voltage curves obtained in wild-type and engineered HEK-293 cells (n = 6, 7, 5, and 9 for the wt, Kir2.1, Kir2.1+Nav1.5, and Kir2.1+Nav1.5+Cx43 monoclonal lines, respectively). Inset shows close-up of steady-state endogenous outward current.

Supplementary Figure S3 | Functional assessment of intercellular coupling in engineered HEK-293 cells. (a) Representative recordings of fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) in monoclonal HEK-293 cell lines. Confluent monolayers of Kir2.1+Nav1.5 or Kir2.1+Nav1.5+Cx43 (“Ex-293”) cells were loaded with Calcein dye (green) and single cells (indicated by white arrows) were selectively photobleached using a confocal microscope and Argon laser. (b) After 6 minutes, fluorescence only slightly recovered in Kir2.1+Nav1.5 cells (n = 6) revealing weak endogenous intercellular coupling. In contrast, Cx43 expressing Ex-293 cells exhibited significant fluorescence recovery (n = 7) which was completely abolished by the application of the gap junction blocker palmitoleic acid (PA) (n = 6). (c) Two abutting Ex-293 cells (labelled 1 and 2) were individually voltage-clamped in whole-cell mode. (d) Initially, both cells were held at 0 mV. Cell 1 was then depolarized by a 20 mV voltage step (Vm 1) while Cell 2 remained clamped at 0 mV (Vm 2), eliciting a current response Im 1 (in Cell 1) and a transjunctional current response Im 2 (in Cell 2). Block of gap junctional coupling by the application of 500 μM palmitoleic acid (PA) abolished the flow of transjunctional current (bottom trace). Measured average gap junctional conductance in Ex-293 cell pairs was 134.1 ± 14.0 nS (mean ± s.e.m., n = 15).

Supplementary Figure S4 | Action potential propagation in Ex-293 cell monolayers. (a) Point stimulation (pulse sign) in isotropic monolayers with randomly oriented Ex-293 cells yielded a circular propagation pattern as shown by a frame of transmembrane voltage during 25 Hz stimulation (blue to red denotes rest to peak of action potential) and by the corresponding isochrone map of activation (isochrone lines labelled in ms). (b) In comparison, Ex-293 cells grown on a substrate containing parallel microgrooves elongated and aligned along the grooves (red arrow, top panel) to form anisotropic monolayers. Point stimulation in these cell networks yielded faster action potential propagation along rather than across the aligned cells, thus creating an elliptical activation pattern. (c) Ex-293 cells within 150 μm wide micropatterned strands preferentially aligned along the strand and exhibited faster action potential propagation than cells in isotropic monolayers. Propagation in strands was recorded at 20x magnification. Small circles in propagation maps denote 504 optical recordings sites. Representative movies of action potential propagation in different 2-D networks of Ex-293 cells are compiled in Supplementary Movie 1.

Supplementary Figure S5 | Dose-dependent effects of IK1 and INa inhibition on the shape of propagated action potentials in Ex-293 cells. Ex-293 monolayers were paced at 1 Hz stimulation rate and AP of individual cells were recorded by sharp microelectrodes. (a,b) Inhibition of IK1 by increasing doses of BaCl2 prolonged AP duration at 80% repolarization (APD80, a), and decreased maximum upstroke velocity ((dVm/dt)max, b). (c,d) Inhibition of INa by increasing doses of TTX decreased APD80 (c) and maximum upstroke velocity ((dVm/dt)max, d). Error bars denote mean ± s.e.m.; n = 7–20; *P < 0.001; #P < 0.01; ^P < 0.05 vs. corresponding drug-free values.

Supplementary Figure S6 | Pharmacological inhibition of INa modulates action potential conduction and spiral activity in Ex-293 cell monolayers. (a) Effect of Nav1.5 channel inhibitors lidocaine and flecainide on APD80 and CV during 10 Hz stimulation (n = 3-5 coverslips). APD80 and CV in drug-free control monolayers remained relatively unaffected by the stimulation. Application of 50 μM lidocaine yielded a reduction of APD80 and CV to values that remained stable during the 10 Hz stimulation (linear regression, P = 0.94 and 0.43 for APD80 and CV, respectively). In contrast, application of 10 μM flecainide yielded not only an initial reduction of APD80 and CV, but also a rapid, use-dependent decrease in APD80 and CV during consecutive stimulus pulses (linear regression, P < 0.0001 for both APD80 and CV), until conduction block eventually occurred. Error bars were removed for enhanced clarity of trend. (b) Anchored spiral wave activity in Ex-293 monolayers during perfusion with sodium channel inhibitors. White lines denote spiral tip trajectories tracked for 2 seconds. Prior to the addition of the inhibitors, the rotating wave was continuously attached to the obstacle. During drug perfusion, spiral rotational rate was slowed by increased spiral tip meandering due to multiple detachments from the central obstacle. Spiral activity was eventually terminated (as captured in top and bottom frame) by permanent detachment of the spiral, followed by spiral drift and annihilation against the monolayer boundary (at the end of tracked tip trajectory). Frames in b show colour-coded optically recorded transmembrane voltage (blue to red denote rest to peak of action potential) while small circles within these frames denote the 504 optical recording sites.

Supplementary Figure S7 | Ex-293 cells enable fast electrical conduction between distant regions of 2-D cardiac networks. (a) 2-D co-cultures of neonatal rat ventricular myocytes, NRVMs (red), and Ex-293 cells (unstained) exhibited abundant heterocellular (white arrows) and homocellular (yellow arrows) Cx43 gap junctions (green). (b) Two isolated NRVM regions (islands) connected by a 2.5 cm long “S”-shaped bridge made of either wt HEK-293 (control) or Ex-293 cells. Action potential propagation initiated at one NRVM island (pulse sign) is blocked at the entrance to the wild-type HEK-293 bridge (middle panel), but seamlessly continued through the Ex-293 bridge into the remote NRVM island (right panel, see Supplementary Movie 4). (c) A circular (1 cm in diameter) central acellular gap within NRVM monolayers was filled with a “tissue graft” made of either wild-type (wt) HEK-293 or Ex-293 cells. Upon point stimulation (pulse sign) in the NRVM region, action potential propagation traveled around rather than through the wt HEK-293 graft. In contrast, the use of the excitable Ex-293 graft enabled smooth and direct propagation through the entire monolayer. Note shorter action potential duration of the Ex-293 cells compared to the NRVMs as evidenced by the shorter wave width (at t = 57 ms) and faster repolarization (at t = 76 ms) in the graft area. The Ex-293 grafts seamlessly restored conduction within NRVM cultures at all stimulation rates that could be sustained by NRVMs (up to ~10 Hz, not shown). Small black circles in b and c denote 504 optical recording sites.

Supplementary Table S1: FRAP results of intercellular coupling

Supplementary Table S2: Biophysical properties of the Ex-293 cell line

Acknowledgments

We thank N. Badie and J. Scull for assistance with optical mapping setup and software; L. McSpadden for FRAP analysis software; J. Dempster for WinWCP software; S. Hinds for assistance with tissue engineering experiments; Z.S. Zhang for advice with patch-clamp experiments; L. Satterwhite and A. Krol for NRVM isolation; R. Abraham for Kir2.1 cDNA; A.O. Grant and V. Neplioueva for Nav1.5 cDNA; R. Tsien for mCherry and mOrange cDNA; as well as D. Gauthier and L. Satterwhite for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by predoctoral fellowships from the National Science Foundation and the American Heart Association to R.D.K. and research grants to N.B. from the American Heart Association (AHA 0530256N) and National Institutes of Health (HL106203, HL104326, HL083342 and HL095069).

Footnotes

Author contributions R.D.K. and N.B. designed the project. R.D.K. performed experiments. R.D.K. and N.B. analyzed results and cowrote the manuscript.

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at http://www.nature.com/naturecommunications

Competing financial interests: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Reprints and permission information is available online at http://npg.nature.com/reprintsandpermissions/

References

- 1.Hille B. Ion Channels of Excitable Membranes. Sinauer; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Catterall WA. The molecular basis of neuronal excitability. Science. 1984;223:653–661. doi: 10.1126/science.6320365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kleber AG, Rudy Y. Basic mechanisms of cardiac impulse propagation and associated arrhythmias. Physiol. Rev. 2004;84:431–488. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00025.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kass RS. The channelopathies: novel insights into molecular and genetic mechanisms of human disease. J. Clin. Invest. 2005;115:1986–1989. doi: 10.1172/JCI26011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lloyd-Jones D, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics--2010 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2010;121:e46–e215. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ashcroft FM. From molecule to malady. Nature. 2006;440:440–447. doi: 10.1038/nature04707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tan HL, et al. A sodium-channel mutation causes isolated cardiac conduction disease. Nature. 2001;409:1043–1047. doi: 10.1038/35059090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barela AJ, et al. An epilepsy mutation in the sodium channel SCN1A that decreases channel excitability. J. Neurosci. 2006;26:2714–2723. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2977-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aidley DJ. The Physiology of Excitable Cells. Cambridge University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hodgkin AL, Huxley AF. A quantitative description of membrane current and its application to conduction and excitation in nerve. J. Physiol. 1952;117:500–544. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1952.sp004764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fitzhugh R. Impulses and physiological states in theoretical models of nerve membrane. Biophys. J. 1961;1:445–466. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3495(61)86902-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zykov VS, Winfree AT. Simulation of Wave Processes in Excitable Media. Manchester University Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kubo Y, Baldwin TJ, Jan YN, Jan LY. Primary structure and functional expression of a mouse inward rectifier potassium channel. Nature. 1993;362:127–133. doi: 10.1038/362127a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gellens ME, et al. Primary structure and functional expression of the human cardiac tetrodotoxin-insensitive voltage-dependent sodium channel. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1992;89:554–558. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.2.554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fishman GI, Moreno AP, Spray DC, Leinwand LA. Functional analysis of human cardiac gap junction channel mutants. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1991;88:3525–3529. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.9.3525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nerbonne JM, Kass RS. Molecular physiology of cardiac repolarization. Physiol. Rev. 2005;85:1205–1253. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00002.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grant AO. Cardiac ion channels. Circ. Arrhythm. Electrophysiol. 2009;2:185–194. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.108.789081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shaner NC, et al. Improved monomeric red, orange and yellow fluorescent proteins derived from Discosoma sp. red fluorescent protein. Nat. Biotechnol. 2004;22:1567–1572. doi: 10.1038/nbt1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yu SP, Kerchner GA. Endogenous voltage-gated potassium channels in human embryonic kidney (HEK293) cells. J. Neurosci. Res. 1998;52:612–617. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19980601)52:5<612::AID-JNR13>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thomas P, Smart TG. HEK293 cell line: a vehicle for the expression of recombinant proteins. J. Pharmacol. Toxicol. Methods. 2005;51:187–200. doi: 10.1016/j.vascn.2004.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dhamoon AS, Jalife J. The inward rectifier current (IK1) controls cardiac excitability and is involved in arrhythmogenesis. Heart Rhythm. 2005;2:316–324. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2004.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grant AO, Chandra R, Keller C, Carboni M, Starmer CF. Block of wild-type and inactivation-deficient cardiac sodium channels IFM/QQQ stably expressed in mammalian cells. Biophys. J. 2000;79:3019–3035. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76538-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim T, et al. The biochemical activation of T-type Ca2+ channels in HEK293 cells stably expressing alpha1G and Kir2.1 subunits. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004;324:401–408. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.09.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ibarra J, Morley GE, Delmar M. Dynamics of the inward rectifier K+ current during the action potential of guinea pig ventricular myocytes. Biophys. J. 1991;60:1534–1539. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(91)82187-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gray RA, Pertsov AM, Jalife J. Spatial and temporal organization during cardiac fibrillation. Nature. 1998;392:75–78. doi: 10.1038/32164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Butterweck A, Gergs U, Elfgang C, Willecke K, Traub O. Immunochemical characterization of the gap junction protein connexin45 in mouse kidney and transfected human HeLa cells. J. Membr. Biol. 1994;141:247–256. doi: 10.1007/BF00235134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McSpadden LC, Kirkton RD, Bursac N. Electrotonic loading of anisotropic cardiac monolayers by unexcitable cells depends on connexin type and expression level. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2009;297:C339–351. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00024.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Toyofuku T, et al. Direct association of the gap junction protein connexin-43 with ZO-1 in cardiac myocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:12725–12731. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.21.12725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abbaci M, et al. Gap junctional intercellular communication capacity by gap-FRAP technique: a comparative study. Biotechnol. J. 2007;2:50–61. doi: 10.1002/biot.200600092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.del Corsso C, et al. Transfection of mammalian cells with connexins and measurement of voltage sensitivity of their gap junctions. Nat. Protoc. 2006;1:1799–1809. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yao JA, et al. Remodeling of gap junctional channel function in epicardial border zone of healing canine infarcts. Circ. Res. 2003;92:437–443. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000059301.81035.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Klinger R, Bursac N. Cardiac cell therapy in vitro: reproducible assays for comparing the efficacy of different donor cells. IEEE Eng. Med. Biol. Mag. 2008;27:72–80. doi: 10.1109/MEMB.2007.913849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carboni M, Zhang ZS, Neplioueva V, Starmer CF, Grant AO. Slow sodium channel inactivation and use-dependent block modulated by the same domain IV S6 residue. J. Membr. Biol. 2005;207:107–117. doi: 10.1007/s00232-005-0805-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu H, Atkins J, Kass RS. Common molecular determinants of flecainide and lidocaine block of heart Na+ channels: evidence from experiments with neutral and quaternary flecainide analogues. J. Gen. Physiol. 2003;121:199–214. doi: 10.1085/jgp.20028723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Winfree AT. Spiral waves of chemical activity. Science. 1972;175:634–636. doi: 10.1126/science.175.4022.634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Davidenko JM, Pertsov AV, Salomonsz R, Baxter W, Jalife J. Stationary and drifting spiral waves of excitation in isolated cardiac muscle. Nature. 1992;355:349–351. doi: 10.1038/355349a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bian W, Liau B, Badie N, Bursac N. Mesoscopic hydrogel molding to control the 3D geometry of bioartificial muscle tissues. Nat. Protoc. 2009;4:1522–1534. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hsu H, et al. Slow and incomplete inactivations of voltage-gated channels dominate encoding in synthetic neurons. Biophys. J. 1993;65:1196–1206. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(93)81153-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cho HC, Kashiwakura Y, Azene E, Marban E. Conversion of non-excitable cells to self-contained biological pacemakers. Circulation. 2005;112:II–307. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Abraham MR, et al. Antiarrhythmic engineering of skeletal myoblasts for cardiac transplantation. Circ. Res. 2005;97:159–167. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000174794.22491.a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rudy B, Iverson LE, Conn PM. Ion Channels. Academic Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chandra R, Starmer CF, Grant AO. Multiple effects of KPQ deletion mutation on gating of human cardiac Na+ channels expressed in mammalian cells. Am. J. Physiol. 1998;274:H1643–1654. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1998.274.5.H1643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Clancy CE, Tateyama M, Liu H, Wehrens XH, Kass RS. Non-equilibrium gating in cardiac Na+ channels: an original mechanism of arrhythmia. Circulation. 2003;107:2233–2237. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000069273.51375.BD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bendahhou S, et al. Defective potassium channel Kir2. trafficking underlies Andersen-Tawil syndrome. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:51779–51785. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310278200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gollob MH, et al. Somatic mutations in the connexin 40 gene (GJA5) in atrial fibrillation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006;354:2677–2688. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dhar Malhotra J, et al. Characterization of sodium channel alpha- and beta-subunits in rat and mouse cardiac myocytes. Circulation. 2001;103:1303–1310. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.9.1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Xie LH, John SA, Ribalet B, Weiss JN. Phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) regulation of strong inward rectifier Kir2.1 channels: multilevel positive cooperativity. J. Physiol. 2008;586:1833–1848. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.147868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Petitprez S, et al. SAP97 and dystrophin macromolecular complexes determine two pools of cardiac sodium channels Nav1.5 in cardiomyocytes. Circ. Res. 2011;108:294–304. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.228312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rider TH, et al. A B cell-based sensor for rapid identification of pathogens. Science. 2003;301:213–215. doi: 10.1126/science.1084920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Choi YH, et al. Cardiac conduction through engineered tissue. Am. J. Pathol. 2006;169:72–85. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.051163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Roell W, et al. Engraftment of connexin 43-expressing cells prevents post-infarct arrhythmia. Nature. 2007;450:819–824. doi: 10.1038/nature06321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gepstein L. Cell and gene therapy strategies for the treatment of postmyocardial infarction ventricular arrhythmias. Ann. N Y Acad. Sci. 2010;1188:32–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05080.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cho HC, Marban E. Biological therapies for cardiac arrhythmias: can genes and cells replace drugs and devices? Circ. Res. 2010;106:674–685. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.212936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yankelson L, et al. Cell therapy for modification of the myocardial electrophysiological substrate. Circulation. 2008;117:720–731. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.671776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Miragoli M, Gaudesius G, Rohr S. Electrotonic modulation of cardiac impulse conduction by myofibroblasts. Circ. Res. 2006;98:801–810. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000214537.44195.a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.de Bakker JM, et al. Slow conduction in the infarcted human heart. ‘Zigzag’ course of activation. Circulation. 1993;88:915–926. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.88.3.915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.de Boer TP, et al. Inhibition of cardiomyocyte automaticity by electrotonic application of inward rectifier current from Kir2.1 expressing cells. Med. Biol. Eng. Comput. 2006;44:537–542. doi: 10.1007/s11517-006-0059-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Van Rijen HV, Wilders R, Rook MB, Jongsma HJ. Dual patch clamp. Methods Mol. Biol. 2001;154:269–292. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-043-8:269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Badie N, Bursac N. Novel micropatterned cardiac cell cultures with realistic ventricular microstructure. Biophys. J. 2009;96:3873–3885. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.02.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bursac N, Aguel F, Tung L. Multiarm spirals in a two-dimensional cardiac substrate. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:15530–15534. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400984101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure S1 | Summary of experimental approach. (a) Unexcitable wild-type HEK-293 cells were transfected with the Kir2.1-IRES-mCherry plasmid and monoclonal lines were derived from cells that exhibited high mCherry fluorescence intensity. These lines also exhibited strong inward rectifying potassium current (IK1) and a hyperpolarized resting membrane potential. (b) Subsequently, the Nav1.5-IRES-GFP plasmid was transfected into a Kir2.1 HEK-293 monoclonal cell line. The derived monoclonal lines that expressed strong GFP fluorescence also exhibited robust fast inward sodium current (INa) and the ability to fire regenerative action potentials (APs) upon electrical stimulation. (c) Finally, the Cx43-IRES-mOrange plasmid was transfected into a Kir2.1+Nav1.5 HEK-293 monoclonal cell line to derive Kir2.1+Nav1.5+Cx43 HEK-293 monoclonal lines with strong mOrange fluorescence and abundant expression of Cx43 gap junctions at cell borders. Upon electrical stimulation, multicellular networks made from these lines supported fast and uniform action potential propagation. This proof-of-concept strategy demonstrates that unexcitable human cells can be converted into novel electrically excitable and conductive cell sources for the creation of functional excitable tissues.

Supplementary Figure S2 | IK1 expression in engineered HEK-293 cell lines. (a) Representative whole-cell voltage clamp IK1 recording in a HEK-293 cell stably transfected with Kir2.1 compared to wild-type (wt) HEK-293 cells. Bottom panel shows close-up of endogenous currents elicited in a wt HEK-293 cell during application of the same voltage pulse protocol (top panel). (b) Resulting steady state IK1-voltage curves obtained in wild-type and engineered HEK-293 cells (n = 6, 7, 5, and 9 for the wt, Kir2.1, Kir2.1+Nav1.5, and Kir2.1+Nav1.5+Cx43 monoclonal lines, respectively). Inset shows close-up of steady-state endogenous outward current.

Supplementary Figure S3 | Functional assessment of intercellular coupling in engineered HEK-293 cells. (a) Representative recordings of fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) in monoclonal HEK-293 cell lines. Confluent monolayers of Kir2.1+Nav1.5 or Kir2.1+Nav1.5+Cx43 (“Ex-293”) cells were loaded with Calcein dye (green) and single cells (indicated by white arrows) were selectively photobleached using a confocal microscope and Argon laser. (b) After 6 minutes, fluorescence only slightly recovered in Kir2.1+Nav1.5 cells (n = 6) revealing weak endogenous intercellular coupling. In contrast, Cx43 expressing Ex-293 cells exhibited significant fluorescence recovery (n = 7) which was completely abolished by the application of the gap junction blocker palmitoleic acid (PA) (n = 6). (c) Two abutting Ex-293 cells (labelled 1 and 2) were individually voltage-clamped in whole-cell mode. (d) Initially, both cells were held at 0 mV. Cell 1 was then depolarized by a 20 mV voltage step (Vm 1) while Cell 2 remained clamped at 0 mV (Vm 2), eliciting a current response Im 1 (in Cell 1) and a transjunctional current response Im 2 (in Cell 2). Block of gap junctional coupling by the application of 500 μM palmitoleic acid (PA) abolished the flow of transjunctional current (bottom trace). Measured average gap junctional conductance in Ex-293 cell pairs was 134.1 ± 14.0 nS (mean ± s.e.m., n = 15).

Supplementary Figure S4 | Action potential propagation in Ex-293 cell monolayers. (a) Point stimulation (pulse sign) in isotropic monolayers with randomly oriented Ex-293 cells yielded a circular propagation pattern as shown by a frame of transmembrane voltage during 25 Hz stimulation (blue to red denotes rest to peak of action potential) and by the corresponding isochrone map of activation (isochrone lines labelled in ms). (b) In comparison, Ex-293 cells grown on a substrate containing parallel microgrooves elongated and aligned along the grooves (red arrow, top panel) to form anisotropic monolayers. Point stimulation in these cell networks yielded faster action potential propagation along rather than across the aligned cells, thus creating an elliptical activation pattern. (c) Ex-293 cells within 150 μm wide micropatterned strands preferentially aligned along the strand and exhibited faster action potential propagation than cells in isotropic monolayers. Propagation in strands was recorded at 20x magnification. Small circles in propagation maps denote 504 optical recordings sites. Representative movies of action potential propagation in different 2-D networks of Ex-293 cells are compiled in Supplementary Movie 1.

Supplementary Figure S5 | Dose-dependent effects of IK1 and INa inhibition on the shape of propagated action potentials in Ex-293 cells. Ex-293 monolayers were paced at 1 Hz stimulation rate and AP of individual cells were recorded by sharp microelectrodes. (a,b) Inhibition of IK1 by increasing doses of BaCl2 prolonged AP duration at 80% repolarization (APD80, a), and decreased maximum upstroke velocity ((dVm/dt)max, b). (c,d) Inhibition of INa by increasing doses of TTX decreased APD80 (c) and maximum upstroke velocity ((dVm/dt)max, d). Error bars denote mean ± s.e.m.; n = 7–20; *P < 0.001; #P < 0.01; ^P < 0.05 vs. corresponding drug-free values.

Supplementary Figure S6 | Pharmacological inhibition of INa modulates action potential conduction and spiral activity in Ex-293 cell monolayers. (a) Effect of Nav1.5 channel inhibitors lidocaine and flecainide on APD80 and CV during 10 Hz stimulation (n = 3-5 coverslips). APD80 and CV in drug-free control monolayers remained relatively unaffected by the stimulation. Application of 50 μM lidocaine yielded a reduction of APD80 and CV to values that remained stable during the 10 Hz stimulation (linear regression, P = 0.94 and 0.43 for APD80 and CV, respectively). In contrast, application of 10 μM flecainide yielded not only an initial reduction of APD80 and CV, but also a rapid, use-dependent decrease in APD80 and CV during consecutive stimulus pulses (linear regression, P < 0.0001 for both APD80 and CV), until conduction block eventually occurred. Error bars were removed for enhanced clarity of trend. (b) Anchored spiral wave activity in Ex-293 monolayers during perfusion with sodium channel inhibitors. White lines denote spiral tip trajectories tracked for 2 seconds. Prior to the addition of the inhibitors, the rotating wave was continuously attached to the obstacle. During drug perfusion, spiral rotational rate was slowed by increased spiral tip meandering due to multiple detachments from the central obstacle. Spiral activity was eventually terminated (as captured in top and bottom frame) by permanent detachment of the spiral, followed by spiral drift and annihilation against the monolayer boundary (at the end of tracked tip trajectory). Frames in b show colour-coded optically recorded transmembrane voltage (blue to red denote rest to peak of action potential) while small circles within these frames denote the 504 optical recording sites.

Supplementary Figure S7 | Ex-293 cells enable fast electrical conduction between distant regions of 2-D cardiac networks. (a) 2-D co-cultures of neonatal rat ventricular myocytes, NRVMs (red), and Ex-293 cells (unstained) exhibited abundant heterocellular (white arrows) and homocellular (yellow arrows) Cx43 gap junctions (green). (b) Two isolated NRVM regions (islands) connected by a 2.5 cm long “S”-shaped bridge made of either wt HEK-293 (control) or Ex-293 cells. Action potential propagation initiated at one NRVM island (pulse sign) is blocked at the entrance to the wild-type HEK-293 bridge (middle panel), but seamlessly continued through the Ex-293 bridge into the remote NRVM island (right panel, see Supplementary Movie 4). (c) A circular (1 cm in diameter) central acellular gap within NRVM monolayers was filled with a “tissue graft” made of either wild-type (wt) HEK-293 or Ex-293 cells. Upon point stimulation (pulse sign) in the NRVM region, action potential propagation traveled around rather than through the wt HEK-293 graft. In contrast, the use of the excitable Ex-293 graft enabled smooth and direct propagation through the entire monolayer. Note shorter action potential duration of the Ex-293 cells compared to the NRVMs as evidenced by the shorter wave width (at t = 57 ms) and faster repolarization (at t = 76 ms) in the graft area. The Ex-293 grafts seamlessly restored conduction within NRVM cultures at all stimulation rates that could be sustained by NRVMs (up to ~10 Hz, not shown). Small black circles in b and c denote 504 optical recording sites.

Supplementary Table S1: FRAP results of intercellular coupling

Supplementary Table S2: Biophysical properties of the Ex-293 cell line