Abstract

Aims

The aim of this study was to examine the association between long-term alcohol consumption, alcohol consumption before and after myocardial infarction (MI), and all-cause and cardiovascular mortality among survivors of MI.

Methods and results

The Health Professionals Follow-up Study (HPFS) is a prospective cohort study of 51 529 US male health professionals. From 1986 to 2006, 1818 men were confirmed with incident non-fatal MI. Among MI survivors, 468 deaths were documented during up to 20 years of follow-up. Long-term average alcohol consumption was calculated beginning from the time period immediately before the first MI and updated every 4 years afterward. Cox proportional hazards were used to estimate the multivariable-adjusted hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). Compared with non-drinkers, the multivariable-adjusted HRs for all-cause mortality were 0.78 (95% CI: 0.62–0.97) for 0.1–9.9 g/day, 0.66 (95% CI: 0.51–0.86) for 10.0–29.9 g/day, and 0.87 (95% CI: 0.61–1.25) for ≥30 g/day (Pquadratic= 0.006). For cardiovascular mortality, the corresponding HRs were 0.74 (95% CI: 0.54–1.02), 0.58 (95% CI: 0.39–0.84), and 0.98 (95% CI: 0.60–1.60), Pquadratic= 0.003. These findings were consistent when restricted to pre- and post-MI alcohol assessments. In subgroup analyses, moderate alcohol consumption was inversely associated with mortality among men with non-anterior infarcts, and among men with mildly diminished left ventricular function.

Conclusion

Long-term moderate alcohol consumption is inversely associated with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality among men who survived a first MI. This U-shaped association may be strongest among individuals with less impaired cardiac function after MI and should be examined further.

Keywords: Alcohol consumption, Mortality, Myocardial infarction, Survival

Introduction

Moderate alcohol consumption is associated with lower risk of coronary heart disease (CHD) among healthy populations,1,2 and this lower risk has translated largely into reduced cardiovascular and total mortality.3–6 Given that patients who survive a first myocardial infarction (MI) are at increased risk of mortality due to reinfarction or sudden death,7,8 it is plausible to hypothesize that they would benefit from moderate alcohol consumption. Recently, several studies have suggested moderate alcohol consumption may be related to reduced mortality among individuals with established CHD, but the data have been limited and somewhat conflicting. In most,9–13 but not all studies,14–16 moderate alcohol consumption is associated with lower total and cardiovascular mortality among participants with previous MI. A recent meta-analysis supports the J-shaped relationship between alcohol consumption and mortality among patients with cardiovascular disease (CVD).17 However, no prospective studies to date have included validated measures of alcohol consumption reported before and after incident MI with long-term follow-up, and few have included detailed measures of MI characteristics and treatment. In this present study, we examined the association between long-term alcohol consumption among men who survived a first MI, their alcohol consumption before and after MI, and their subsequent risk of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality.

Methods

Study population

The Health Professionals Follow-up Study is a prospective cohort study among 51 529 US male health professionals, aged 40–75 years in 1986, who completed detailed questionnaires assessing dietary intake, lifestyle factors, and medical history at baseline. Information about health and disease is assessed biennially and information about diet is assessed every 4 years by self-administered questionnaires.18 After excluding men with previously diagnosed CVD, stroke, or cancer at baseline in 1986, we prospectively established an inception cohort study among 1818 men who had survived a first MI during follow-up from 1986 until 2006. Myocardial infarction was confirmed by study physicians blinded to participant's exposure status if it met the World Health Organization's criteria (symptoms plus either diagnostic electrocardiographic changes or elevated levels of cardiac enzymes).19,20 All participants gave written informed consent and the Harvard School of Public Health Human Subjects Committee Review Board approved the study protocol.

Assessment of alcohol consumption

Alcohol consumption was assessed every 4 years using a 131-item semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire (FFQ). Participants were asked to report their average intake of beer, white wine, red wine, and liquor in the previous year. Standard portions were specified as a glass, bottle, or can of beer, a 4 oz glass of wine, and a shot of liquor. For drinking habits for each beverage type, there were nine possible response categories ranging from ‘never’ or ‘less than once per month’ to ‘6 or more times per day’. To determine total grams of alcohol intake, we multiplied the frequency of each beverage type by the ethanol content in each portion (12.8 g for beer; 11.0 g for wine; 14.0 g for liquor), and computed the sum of the beverage-specific intakes.

Previous work in this group has validated the assessment of alcohol consumption using the FFQ method. Among 136 men from this cohort, comparisons were made between alcohol assessment using the FFQ and multiple-week diet records over the same time period (gold standard), and were shown to be highly correlated (Spearman, r = 0.86).21

Assessment of covariates

Dietary covariates were assessed every 4 years by questionnaire, and other lifestyle and medical factors were assessed every 2 years. Potential covariates included age, body mass index (BMI), marital status, smoking status, physical activity, total caloric intake, medication use, history of diabetes and hypertension, and family history of early MI. Detailed information on MI treatment and severity, including ST-segment elevation, heart failure during hospitalization, left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), creatinine levels, acute therapy (thrombolytics or angioplasty), and site of initial MI were extracted from medical records from locally treating hospitals.

Outcome ascertainment

The primary outcome in all analyses was total mortality occurring after the first non-fatal MI followed through 30 June 2006. Deaths were identified from state vital records and the national death index or reported by the participant's next of kin or the postal system.22 Cardiovascular mortality was assessed as a secondary outcome, which included fatal MI, fatal stroke, and CHD, and was confirmed by review of medical records or autopsy reports with the permission of the next of kin. Through the end of follow-up, we confirmed 486 total deaths, of which 243 were confirmed as primary cardiovascular of origin.

Statistical analyses

We calculated average alcohol consumption from all available questionnaires from the start of each follow-up time period immediately before the first MI and subsequently updated intake every 4 years post-MI as part of the usual questionnaire follow-up cycles to best represent long-term alcohol consumption. Person-months of follow-up accumulated starting with the date of first MI until the occurrence of death or end of the study period (30 June 2006), whichever came first. The main exposure of total alcohol consumption was divided into four categories: 0, 0.1–9.9, 10.0–29.9, and ≥30 g/day. These categories were created to correspond approximately to 0, 1, 2, and >2 drinks per day.

Given the prospective nature of this inception cohort, we were uniquely able to compare pre-MI alcohol consumption with post-MI alcohol consumption among participants who reported alcohol intake on questionnaires immediately before and after their MI. In exploratory secondary analyses, we assessed whether the association between alcohol consumption and mortality among MI survivors differed by pre- or post-MI alcohol intake.

We used analysis of variance tests for continuous variables and the χ2 test for categorical variables to evaluate associations of lifestyle and clinical characteristics across alcohol categories. Cox proportional hazards analyses were used to estimate the hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). The Cox proportionality assumption was checked and met using the likelihood ratio test. The basic model adjusted for age, questionnaire follow-up cycle, and smoking (never, past, current <15 cigarettes/day, current ≥15 cigarettes/day). Multivariable models further adjusted for BMI (<21, 21–22.9, 23–24.9, 25–27.4, 27.5–29.9, ≥30 kg/m2), physical activity (quintiles), diabetes, hypertension, aspirin use, use of lipid-lowering medication, and heart failure during hospitalization. Tests for linear trend (Ptrend) were calculated using the mid-point of the categories for grams of alcohol per day and modelled as a continuous variable without the quadratic term. This value squared was used to model the quadratic trend (Pquad). All P-values presented are two-sided and P-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. All analyses were conducted using SAS software version 9 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of the 1818 men who survived incident MI, categorized by alcohol consumption. Overall, men, who consumed more alcohol, were more likely to be current smokers (P<0.001) and use aspirin (P = 0.004), and were less likely to have prevalent diabetes (<0.001).

Table 1.

Baseline lifestyle and clinical characteristics of 1818 men with incident non-fatal myocardial infarction in the Health Professionals Follow-up Study

| Alcohol consumption (g/day) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.1–9.9 | 10.0–29.9 | ≥30.0 | P-value* | |

| Lifestyle characteristicsa | |||||

| n | 515 | 719 | 420 | 164 | |

| Alcohol (g/day) | 0 | 3.1 ± 2.1 | 15.8 ± 1.3 | 42.9 ± 1.3 | <0.001 |

| Current smoker (%) | 8.3 | 10.5 | 12.0 | 20.8 | <0.001 |

| Married (%) | 82.7 | 79.3 | 81.0 | 78.0 | 0.46 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.7 ± 3.2 | 26.7 ± 3.0 | 26.6 ± 3.1 | 26.8 ± 3.1 | 0.87 |

| Diabetes (%) | 16.9 | 8.7 | 9.0 | 5.2 | <0.001 |

| Hypertension (%) | 40.8 | 39.1 | 42.0 | 38.3 | 0.70 |

| Aspirin use (%) | 50.0 | 53.0 | 61.1 | 57.8 | 0.004 |

| Lipid-lowering medication (%) | 10.5 | 14.2 | 12.8 | 12.7 | 0.28 |

| Clinical characteristics during hospitalization | |||||

| Anterior MI (%) | 24.2 | 27.0 | 25.5 | 15.9 | 0.02 |

| ST-elevation MI (%) | 37.3 | 44.6 | 36.0 | 40.5 | 0.01 |

| Heart failure during hospitalization for MI (%) | 8.4 | 8.9 | 7.0 | 5.0 | 0.36 |

| Abnormal left ventricular ejection fraction (%)b | 10.4 | 9.1 | 9.2 | 7.5 | 0.88 |

| Acute therapy (%)c | 30.7 | 35.2 | 30.7 | 31.6 | 0.23 |

aAll characteristics are age standardized. Values are mean ± standard deviation for continuous variables, except for alcohol, which is shown as log-transformed geometric mean ± standard deviation, and proportions for categorical variables.

bDefined as the left ventricular ejection fraction <40% or marked abnormal in medical records.

cDefined as acute fibrinolytic therapy or primary angioplasty.

*P-values determined by analysis of variance for continuous variables and χ2 test for categorical variables.

Long-term alcohol consumption and mortality

Moderate alcohol consumption of up to two drinks per day was significantly inversely associated with both all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in basic and adjusted models. The multivariable-adjusted HRs for total mortality were 0.78 (95% CI: 0.62–0.97) for 0.1–9.9 g/day, 0.66 (95% CI: 0.51–0.86) for 10.0–29.9 g/day, and 0.87 (95% CI: 0.61–1.25) for ≥30 g/day (P for quadratic trend = 0.006) (Table 2). Similarly, for cardiovascular mortality, the adjusted HRs were 0.74 (95% CI: 0.54–1.02) for 0.1–9.9 g/day, 0.58 (95% CI: 0.39–0.84) for 10.0–29.9 g/day, and 0.98 (95% CI: 0.60–1.60) for ≥30 g/day (P for quadratic trend = 0.003). Additional adjustments for caloric intake, omega-3 fatty acids, ST-elevation and site of initial MI, and creatinine did not appreciably attenuate the risk estimates. Although HRs were similar across alcoholic beverage types, in analyses mutually adjusted for beer, wine, and liquor, there was no significant association between specific beverage type and mortality (Table 3).

Table 2.

Long-term alcohol consumption and risks for total death and death due to cardiovascular disease among 1818 men with incident non-fatal myocardial infarction

| Long-term alcohol consumption (g/day) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.1–9.9 | 10.0–29.9 | ≥30.0 | Ptrend* | Pquad** | |

| Total deaths | 168 | 161 | 97 | 42 | ||

| Hazard ratio (95% CI)a | 1.0 | 0.75 (0.60–0.93) | 0.61 (0.47–0.79) | 0.77 (0.54–1.10) | 0.03 | 0.003 |

| Multivariable-adjusted hazard ratio (95% CI)b | 1.0 | 0.78 (0.62–0.97) | 0.66 (0.51–0.86) | 0.87 (0.61–1.25) | 0.14 | 0.006 |

| Cardiovascular deaths | 92 | 81 | 47 | 23 | ||

| Hazard ratio (95% CI)a | 1.0 | 0.71 (0.52–0.96) | 0.52 (0.36–0.75) | 0.80 (0.50–1.29) | 0.07 | 0.002 |

| Multivariable-adjusted hazard ratio (95% CI)b | 1.0 | 0.74 (0.54–1.02) | 0.58 (0.39–0.84) | 0.98 (0.60–1.60) | 0.32 | 0.003 |

aAdjusted for age at diagnosis, questionnaire follow-up cycle, and smoking.

bMultivariable adjusted further for BMI, physical activity, diabetes, hypertension, lipid-lowering medication, aspirin use, and heart failure at MI.

*P for linear trend.

**P for quadratic trend.

Table 3.

Beverage-specific long-term alcohol consumption and risks of total death among 1818 men with incident non-fatal myocardial infarction

| Long-term alcohol consumption (g/day) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.1–9.9 | 10–29.9 | ≥30 | Ptrend* | Pquad** | |

| Beer | ||||||

| Total deaths | 274 | 165 | 21 | 6 | ||

| Hazard ratio (95% CI)a | 1.0 | 1.04 (0.82–1.31) | 0.96 (0.63–1.46) | 1.09 (0.46–2.60) | 0.38 | 0.80 |

| Multivariable-adjusted hazard ratio (95% CI)b | 1.0 | 0.98 (0.77–1.24) | 0.84 (0.52–1.35) | 0.95 (0.39–2.32) | 0.29 | 0.96 |

| Wine | ||||||

| Total deaths | 250 | 185 | 30 | 1 | ||

| Hazard ratio (95% CI)a | 1.0 | 0.78 (0.62–0.97) | 0.81 (0.54–1.20) | 0.85 (0.12–6.33) | 0.16 | 0.02 |

| Multivariable-adjusted hazard ratio (95% CI)b | 1.0 | 0.93 (0.74–1.17) | 1.07 (0.71–1.62) | 1.22 (0.16–9.17) | 0.99 | 0.36 |

| Liquor | ||||||

| Total deaths | 286 | 114 | 45 | 23 | ||

| Hazard ratio (95% CI)a | 1.0 | 0.77 (0.60–0.98) | 0.83 (0.59–1.18) | 0.80 (0.51–1.26) | 0.20 | 0.24 |

| Multivariable-adjusted hazard ratio (95% CI)b | 1.0 | 0.80 (0.63–1.02) | 0.84 (0.59–1.20) | 0.89 (0.56–1.41) | 0.40 | 0.26 |

aAdjusted for age at diagnosis, questionnaire follow-up cycle, smoking, and each specific alcohol beverage type.

bMultivariable adjusted further for BMI, physical activity, diabetes, hypertension, lipid-lowering medication, aspirin use, and heart failure at MI.

*P for linear trend.

**P for quadratic trend.

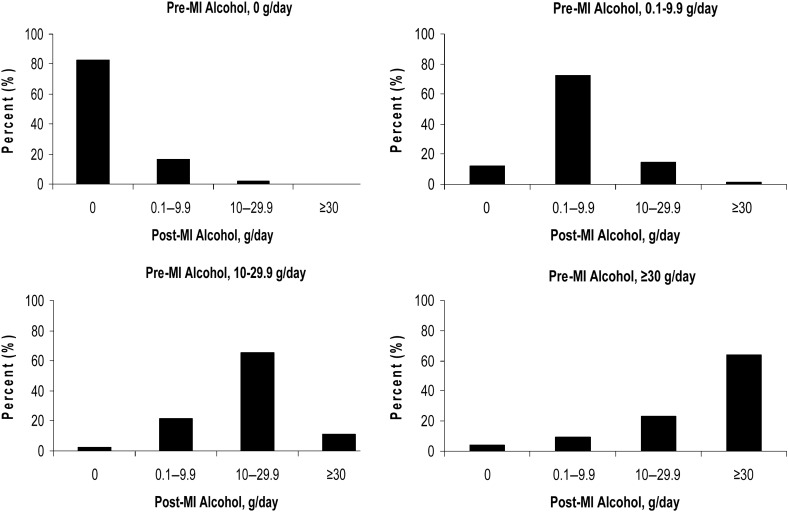

Change in alcohol consumption pre- and post-myocardial infarction

Levels of alcohol consumption before and after diagnosis of MI were highly correlated (Spearman r = 0.83), and the majority of participants did not change alcohol consumption after diagnosis of MI (Figure 1). Compared with non-drinkers, the multivariable-adjusted HRs for total mortality were 0.91 (95% CI: 0.72–1.16) for 0.1–9.9 g/day, 0.70 (95% CI: 0.52–0.93) for 10.0–29.9 g/day, and 1.00 (95% CI: 0.70–1.42) for ≥30 g/day according to pre-MI alcohol only, whereas the corresponding HRs were 0.90 (0.71–1.13), 0.70 (0.52–0.92), and 0.79 (0.53–1.17) according to post-MI alcohol only. For cardiovascular mortality, the multivariable-adjusted HRs were 0.74 (95% CI: 0.52–1.04) for 0.1–9.9 g/day, 0.78 (95% CI: 0.53–1.15) for 10.0–29.9 g/day, and 0.85 (95% CI: 0.50–1.44) for ≥30 g/day according to pre-MI alcohol only, and the corresponding HRs were 0.73 (0.53–1.01), 0.62 (0.42–0.93), and 0.77 (0.44–1.35) according to post-MI alcohol only. The nadir of the U-shaped trend for both total and cardiovascular mortality was consistently observed in the group consuming 10–29.9 g of alcohol per day according to post-MI alcohol.

Figure 1.

Alcohol consumption in relation to myocardial infarction diagnosis—percentage of participants changing alcohol consumption post-myocardial infarction diagnosis compared with their pre-myocardial infarction alcohol consumption.

In a subset of 1633 participants who reported alcohol during the questionnaire cycles immediately before and after MI diagnosis, we examined specific changes in alcohol consumption with risk of mortality without updating alcohol intake (Table 4). Compared with men who did not drink alcohol both before and after MI, consuming 10–29.9 g/day both before and after MI diagnosis was inversely associated with total mortality. In these exploratory analyses, increasing consumption from <10 g/day to 10–29.9 g/day after MI was suggestive of an inverse association with total and cardiovascular death. However, the CI included 1.0 after multivariable adjustment, consistent with the small number of cases in this subpopulation.

Table 4.

Change in alcohol consumption pattern and risks for total death and death due to cardiovascular disease among the 1633 men who reported alcohol consumption on the questionnaires immediately before and after myocardial infarction diagnosis

| Alcohol consumption (g/day) (pre-MI, post-MI) |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol consumption pattern | 0, 0 | <10, <10 | <10, 10–29.9 | <10, ≥30 | 10–29.9, <10 | 10–29.9, 10–29.9 | 10–29.9, ≥30 | ≥30, <10 | ≥30 10–29.9 | ≥30, ≥30 |

| Total deaths | 122 | 166 | 17 | 1 | 27 | 49 | 8 | 8 | 15 | 24 |

| Hazard ratio (95% CI)a | 1.0 | 0.82 (0.64–1.04) | 0.52 (0.31–0.87)* | 0.43 (0.06–3.18) | 0.71 (0.46–1.09) | 0.59 (0.42–0.83)* | 0.78 (0.37–1.64) | 1.40 (0.66–3.00) | 0.95 (0.55–1.66) | 0.73 (0.46–1.14) |

| Multivariable-adjusted hazard ratio (95% CI)b | 1.0 | 0.94 (0.73–1.20) | 0.75 (0.44–1.27) | 0.58 (0.08–4.27) | 0.80 (0.51–1.24) | 0.62 (0.43–0.88)* | 1.14 (0.53–2.44) | 2.66 (1.22–5.80)* | 1.25 (0.71–2.19) | 0.74 (0.47–1.18) |

| Cardiovascular deaths | 70 | 82 | 6 | 1 | 15 | 27 | 8 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| Hazard ratio (95% CI)a | 1.0 | 0.71 (0.50–0.99)* | 0.34 (0.15–0.79)* | 0.49 (0.06–3.93) | 0.65 (0.36–1.17) | 0.59 (0.37–0.94)* | 1.24 (0.55–2.79) | 1.82 (0.72–4.59) | 0.69 (0.29–1.64) | 0.47 (0.22–1.01) |

| Multivariable-adjusted hazard ratio (95% CI)b | 1.0 | 0.78 (0.55–1.11) | 0.45 (0.19–1.05) | 0.79 (0.10–6.23) | 0.77 (0.42–1.39) | 0.70 (0.43–1.14) | 1.35 (0.58–3.17) | 2.41 (0.91–6.39) | 0.80 (0.33–1.93) | 0.59 (0.27–1.27) |

aAdjusted for age at diagnosis, questionnaire follow-up cycle, and smoking.

bMultivariable adjusted further for BMI, physical activity, diabetes, hypertension, lipid-lowering medication, aspirin use, and heart failure at MI.

*P< 0.05.

Stratified analyses by myocardial infarction characteristics

The inverse association with moderate alcohol consumption was examined in subgroup analyses by the initial site of MI and LVEF. Among the 1298 men with available initial site of MI, moderate alcohol consumption was significantly inversely associated with mortality among men with non-anterior MIs, but not for men with anterior MIs. Compared with non-drinkers, the multivariable-adjusted HRs for total mortality were 0.66 (95% CI: 0.38–1.14) for 0.1–9.9 g/day, 0.58 (95% CI: 0.32–1.07) for 10.0–29.9 g/day, and 0.93 (95% CI: 0.37–2.33) for ≥30 g/day (P for quadratic trend = 0.09) among anterior infarcts, whereas among non-anterior infarcts, the corresponding HRs were 0.78 (95% CI: 0.56–1.10) for 0.1–9.9 g/day, 0.51 (95% CI: 0.33–0.79) for 10.0–29.9 g/day, and 0.72 (95% CI: 0.42–1.26) for ≥30 g/day (P for quadratic trend = 0.02). Additionally, among 973 men with available LVEF information, moderate alcohol consumption was inversely associated with all-cause mortality among men with normal or mildly diminished left ventricular function, but was not associated with all-cause mortality among men with diminished left ventricular function. Compared with non-drinkers, the multivariable-adjusted HRs for total mortality were 0.65 (95% CI: 0.43–0.98) for 0.1–9.9 g/day, 0.48 (95% CI: 0.29–0.79) for 10.0–29.9 g/day, and 1.13 (95% CI: 0.58–2.23) for ≥30 g/day (P for quadratic trend = 0.001) among men with normal or ≥40% LVEF, whereas the corresponding HRs among men with abnormal or <40% LVEF were 1.00 (95% CI: 0.40–2.51) for 0.1–9.9 g/day, 0.83 (95% CI: 0.26–2.64) for 10.0–29.9 g/day, and 0.97 (95% CI: 0.18–5.15) for ≥30 g/day (P for quadratic trend = 0.82). These results suggest that moderate alcohol consumption may be more beneficial for men with non-anterior infarcts or with mildly diminished ventricular function, but it should be noted that the CI overlap in these subgroups.

Discussion

In this inception cohort of male health professionals with a first MI, moderate alcohol consumption was inversely associated with total and cardiovascular mortality. This inverse association may be weaker among men with a higher risk of subsequent mortality based on initial MI severity.

Previously, the US Physicians’ Health Study reported that two to six drinks per week at baseline was associated with a 30% lower risk of total and cardiovascular mortality among men with a history of MI.11 Retrospectively recalled moderate alcohol consumption at the time of MI was associated with a reduced risk of total and cardiovascular mortality in the MI Onset Study9 and the Stockholm Heart Epidemiology Program study,10 but the estimates were not statistically significant after adjustment for potential confounders. For post-MI alcohol assessments, habitual moderate wine consumption during follow-up was associated with significantly reduced risk of cardiovascular complications in the Lyon Diet Heart Study;12 however, light-moderate alcohol consumption up to 1 year after MI was not significantly associated with mortality, angina, or hospitalizations in the Prospective Registry Evaluating Myocardial Infarction: Event and Recovery (PREMIER) study.16 This present study differs from the previous studies in several ways. In particular, our study is the first prospective study to evaluate alcohol use before MI occurrence, after incident MI, and long-term risk of mortality. These findings are consistent with results from previous studies that reported moderate alcohol consumption was beneficial among MI survivors, but we further incorporated prospective measures of and changes in alcohol intake, beverage type, detailed adjustment for potential confounders, and additional risk stratification based on MI severity.

The associations of moderate alcohol consumption with lower risk and better prognosis of CVD may work through several biological mechanisms. In a large meta-analysis, moderate alcohol consumption of 30 g/day was associated with a significant 4.0 mg/dL increase in HDL cholesterol.23 In addition to positive HDL effects, moderate alcohol consumption has been associated with improved insulin sensitivity,24 decreased fibrinogen levels,25 and decreased levels of inflammatory markers,26 such as C-reactive protein and interleukin-6. Furthermore, moderate alcohol consumption has been significantly associated with less coronary calcification among asymptomatic subjects27 as well as reduced progression of coronary atherosclerosis among MI survivors with serial angiographic measurements.28 Additionally, some of these effects may have a short latency. In healthy populations29 and in our study, participants who increased their consumption from little or none up to moderate levels had a suggestion of subsequent lower risk of mortality compared with those who stayed abstainers.

We also found that the inverse association of moderate alcohol consumption after MI may depend on initial MI treatment and severity. Anterior wall infarct location is associated with larger infarct size,30 reinfarction,31 subsequent heart failure,32 and greater risk of mortality,30 compared with non-anterior infarcts. Our results show that moderate alcohol consumption is beneficial among men with non-anterior infarcts. Nevertheless, maybe due to limited sample size, no statistically significant difference was found between non-anterior and anterior group and further research is needed. Additionally, impaired LVEF has been associated with poor prognosis and mortality.33,34 In our study, alcohol consumption was not associated with mortality among men with impaired LVEF. This finding was consistent with the Survival and Ventricular Enlargement (SAVE) trial,15 but not the Optimal Therapy in Myocardial Infarction with the Angiotensin II Antagonist Losartan (OPTIMAAL) trial,13 which only adjusted for age and smoking. Given that anterior MIs have been associated with greater cardiac damage and taken together with our findings based on left ventricular function, moderate alcohol consumption may not be strongly associated with better prognosis among men whose cardiac function after MI is the most severely impaired.

The well-known side effects of excessive alcohol consumption should be considered carefully when providing recommendations to individuals post-MI. For example, heavy alcohol intake decreases LVEF,35 increases blood pressure,36 and acutely inhibits fibrinolysis.37 The MI Onset Study previously reported that the apparent benefit from light drinking after MI was entirely eliminated by episodes of binge drinking.38 Our results also suggest a significant U-shaped association with the greatest benefit observed among moderate drinkers, and a suggestion of excess mortality among men who consumed more than two drinks per day post-MI. Thus, this study emphasizes the importance of alcohol in moderation. Furthermore, this study supports continued moderate alcohol consumption among men previously consuming moderate amounts of alcohol prior to MI, and among men who had better long-term prognosis based on initial MI characteristics and severity. Our findings are consistent with the recent European Society of Cardiology (ESC) recommended guidelines7,8,39 for long-term management of acute coronary syndromes that moderate alcohol consumption of 10–30 g per day in men should not be discouraged and may be beneficial for long-term prognosis after MI.

Several limitations to our study should be addressed. Measurement error often occurs when using self-reported questionnaires. However, the reproducibility and validity of the self-reported questionnaire has been well documented in this population of male health professionals,18,40 and in particular, shown to be highly correlated with the gold standard for measuring alcohol consumption.21 Nonetheless, despite the careful adjustment in multivariable models, alcohol use is associated with other life-style and health-related factors, and residual confounding may exist. Additionally, it should be noted that the treatments reflect the time-period standards at the time of MI occurrence over the last 20 years, and longer follow-up is necessary to study subgroups by more recent treatment regimens such as men with high rates of primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Finally, while we recognize this cohort of male health professionals does not represent a random sample of US men, their relative socioeconomic homogeneity can be considered a strength in reducing residual confounding from unmeasured factors related to socioeconomic status. Additional strengths of this study include the long duration of follow-up, the prospective nature of the data collection which provided unique ability to assess updated alcohol consumption truly before and after MI until the end of follow-up, detailed multivariable adjustment for lifestyle and health factors, subgroup analyses based on characteristics of the initial MI, and also the ability to compare change in alcohol consumption before and after diagnosis of MI.

Our results clearly support the hypothesis that long-term moderate alcohol consumption among individuals with prior MI may be beneficial for all-cause and cardiovascular mortality. This U-shaped association may be stronger among men with better long-term prognosis after MI and further examination is warranted to determine the suitability of moderate alcohol consumption among individuals with other severe cardiovascular conditions.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant numbers AA11181, HL35464, CA55075, and HL088372 to J.K.P.). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Ms. Lydia Liu for statistical and programming assistance.

References

- 1.Criqui MH. Alcohol and coronary heart disease: consistent relationship and public health implications. Clin Chim Acta. 1996;246:51–57. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(96)06226-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rimm EB, Klatsky A, Grobbee D, Stampfer MJ. Review of moderate alcohol consumption and reduced risk of coronary heart disease: is the effect due to beer, wine, or spirits. BMJ. 1996;312:731–736. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7033.731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Friedman LA, Kimball AW. Coronary heart disease mortality and alcohol consumption in Framingham. Am J Epidemiol. 1986;124:481–489. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Keil U, Chambless LE, Doring A, Filipiak B, Stieber J. The relation of alcohol intake to coronary heart disease and all-cause mortality in a beer-drinking population. Epidemiology. 1997;8:150–156. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199703000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gaziano JM, Gaziano TA, Glynn RJ, Sesso HD, Ajani UA, Stampfer MJ, Manson JE, Hennekens CH, Buring JE. Light-to-moderate alcohol consumption and mortality in the Physicians’ Health Study enrollment cohort. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;35:96–105. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00531-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thun MJ, Peto R, Lopez AD, Monaco JH, Henley SJ, Heath CW, Jr, Doll R. Alcohol consumption and mortality among middle-aged and elderly U.S. adults. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1705–1714. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199712113372401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hamm CW, Bassand JP, Agewall S, Bax J, Boersma E, Bueno H, Caso P, Dudek D, Gielen S, Huber K, Ohman M, Petrie MC, Sonntag F, Uva MS, Storey RF, Wijns W, Zahger D, Bax JJ, Auricchio A, Baumgartner H, Ceconi C, Dean V, Deaton C, Fagard R, Funck-Brentano C, Hasdai D, Hoes A, Knuuti J, Kolh P, McDonagh T, Moulin C, Poldermans D, Popescu BA, Reiner Z, Sechtem U, Sirnes PA, Torbicki A, Vahanian A, Windecker S, Windecker S, Achenbach S, Badimon L, Bertrand M, Botker HE, Collet JP, Crea F, Danchin N, Falk E, Goudevenos J, Gulba D, Hambrecht R, Herrmann J, Kastrati A, Kjeldsen K, Kristensen SD, Lancellotti P, Mehilli J, Merkely B, Montalescot G, Neumann FJ, Neyses L, Perk J, Roffi M, Romeo F, Ruda M, Swahn E, Valgimigli M, Vrints CJ, Widimsky P. ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation: The Task Force for the management of acute coronary syndromes (ACS) in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Eur Heart J. 2011;32:2999–3054. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van de Werf F, Bax J, Betriu A, Blomstrom-Lundqvist C, Crea F, Falk V, Filippatos G, Fox K, Huber K, Kastrati A, Rosengren A, Steg PG, Tubaro M, Verheugt F, Weidinger F, Weis M. Management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with persistent ST-segment elevation: the Task Force on the Management of ST-Segment Elevation Acute Myocardial Infarction of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:2909–2945. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mukamal KJ, Maclure M, Muller JE, Sherwood JB, Mittleman MA. Prior alcohol consumption and mortality following acute myocardial infarction. JAMA. 2001;285:1965–1970. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.15.1965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Janszky I, Ljung R, Ahnve S, Hallqvist J, Bennet AM, Mukamal KJ. Alcohol and long-term prognosis after a first acute myocardial infarction: the SHEEP study. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:45–53. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Muntwyler J, Hennekens CH, Buring JE, Gaziano JM. Mortality and light to moderate alcohol consumption after myocardial infarction. Lancet. 1998;352:1882–1885. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)06351-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Lorgeril M, Salen P, Martin JL, Boucher F, Paillard F, de Leiris J. Wine drinking and risks of cardiovascular complications after recent acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2002;106:1465–1469. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000029745.63708.e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brugger-Andersen T, Ponitz V, Snapinn S, Dickstein K. Moderate alcohol consumption is associated with reduced long-term cardiovascular risk in patients following a complicated acute myocardial infarction. Int J Cardiol. 2009;133:229–232. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2007.12.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shaper AG, Wannamethee SG. Alcohol intake and mortality in middle aged men with diagnosed coronary heart disease. Heart. 2000;83:394–399. doi: 10.1136/heart.83.4.394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aguilar D, Skali H, Moye LA, Lewis EF, Gaziano JM, Rutherford JD, Hartley LH, Randall OS, Geltman EM, Lamas GA, Rouleau JL, Pfeffer MA, Solomon SD. Alcohol consumption and prognosis in patients with left ventricular systolic dysfunction after a myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:2015–2021. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.01.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carter MD, Lee JH, Buchanan DM, Peterson ED, Tang F, Reid KJ, Spertus JA, Valtos J, O'Keefe JH. Comparison of outcomes among moderate alcohol drinkers before acute myocardial infarction to effect of continued versus discontinuing alcohol intake after the infarct. Am J Cardiol. 2010;105:1651–1654. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.01.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Costanzo S, Di Castelnuovo A, Donati MB, Iacoviello L, de Gaetano G. Alcohol consumption and mortality in patients with cardiovascular disease: a meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:1339–1347. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rimm EB, Giovannucci EL, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Litin LB, Willett WC. Reproducibility and validity of an expanded self-administered semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire among male health professionals. Am J Epidemiol. 1992;135:1114–1126. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116211. discussion 1127–1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Luepker RV, Apple FS, Christenson RH, Crow RS, Fortmann SP, Goff D, Goldberg RJ, Hand MM, Jaffe AS, Julian DG, Levy D, Manolio T, Mendis S, Mensah G, Pajak A, Prineas RJ, Reddy KS, Roger VL, Rosamond WD, Shahar E, Sharrett AR, Sorlie P, Tunstall-Pedoe H. Case definitions for acute coronary heart disease in epidemiology and clinical research studies: a statement from the AHA Council on Epidemiology and Prevention; AHA Statistics Committee; World Heart Federation Council on Epidemiology and Prevention; the European Society of Cardiology Working Group on Epidemiology and Prevention; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Circulation. 2003;108:2543–2549. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000100560.46946.EA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rose GA, Blackburn H. WHO Monograph Series No. 58. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1982. Cardiovascular survey methods. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Giovannucci E, Colditz G, Stampfer MJ, Rimm EB, Litin L, Sampson L, Willett WC. The assessment of alcohol consumption by a simple self-administered questionnaire. Am J Epidemiol. 1991;133:810–817. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rich-Edwards JW, Corsano KA, Stampfer MJ. Test of the national death index and equifax nationwide death search. Am J Epidemiol. 1994;140:1016–1019. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rimm EB, Williams P, Fosher K, Criqui M, Stampfer MJ. Moderate alcohol intake and lower risk of coronary heart disease: meta-analysis of effects on lipids and haemostatic factors. BMJ. 1999;319:1523–1528. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7224.1523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kiechl S, Willeit J, Poewe W, Egger G, Oberhollenzer F, Muggeo M, Bonora E. Insulin sensitivity and regular alcohol consumption: large, prospective, cross sectional population study (Bruneck study) BMJ. 1996;313:1040–1044. doi: 10.1136/bmj.313.7064.1040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jensen T, Retterstol LJ, Sandset PM, Godal HC, Skjonsberg OH. A daily glass of red wine induces a prolonged reduction in plasma viscosity: a randomized controlled trial. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2006;17:471–476. doi: 10.1097/01.mbc.0000240920.72930.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pai JK, Hankinson SE, Thadhani R, Rifai N, Pischon T, Rimm EB. Moderate alcohol consumption and lower levels of inflammatory markers in US men and women. Atherosclerosis. 2006;186:113–120. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2005.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vliegenthart R, Oei HH, van den Elzen AP, van Rooij FJ, Hofman A, Oudkerk M, Witteman JC. Alcohol consumption and coronary calcification in a general population. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:2355–2360. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.21.2355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Janszky I, Mukamal KJ, Orth-Gomer K, Romelsjo A, Schenck-Gustafsson K, Svane B, Kirkeeide RL, Mittleman MA. Alcohol consumption and coronary atherosclerosis progression—the Stockholm Female Coronary Risk Angiographic Study. Atherosclerosis. 2004;176:311–319. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2004.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.King DE, Mainous AG, III, Geesey ME. Adopting moderate alcohol consumption in middle age: subsequent cardiovascular events. Am J Med. 2008;121:201–206. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2007.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stone PH, Raabe DS, Jaffe AS, Gustafson N, Muller JE, Turi ZG, Rutherford JD, Poole WK, Passamani E, Willerson JT, Sobel BE, Robertson T, Braunwald E, Group M. Prognostic significance of location and type of myocardial infarction: independent adverse outcome associated with anterior location. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1988;11:453–463. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(88)91517-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Busk M, Kristensen SD, Rasmussen K, Kelbaek H, Thayssen P, Madsen JK, Abildgaard U, Krusell LR, Mortensen LS, Thuesen L, Andersen HR, Nielsen TT. Clinical reinfarction according to infarct location and reperfusion modality in patients with ST elevation myocardial infarction. A DANAMI-2 long-term follow-up substudy. Cardiology. 2009;113:72–80. doi: 10.1159/000171069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.O'Connor CM, Hathaway WR, Bates ER, Leimberger JD, Sigmon KN, Kereiakes DJ, George BS, Samaha JK, Abbottsmith CW, Candela RJ, Topol EJ, Califf RM. Clinical characteristics and long-term outcome of patients in whom congestive heart failure develops after thrombolytic therapy for acute myocardial infarction: development of a predictive model. Am Heart J. 1997;133:663–673. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(97)70168-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Emond M, Mock MB, Davis KB, Fisher LD, Holmes DR, Jr, Chaitman BR, Kaiser GC, Alderman E, Killip T., III Long-term survival of medically treated patients in the Coronary Artery Surgery Study (CASS) Registry. Circulation. 1994;90:2645–2657. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.90.6.2645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pfeffer MA, Braunwald E, Moye LA, Basta L, Brown EJ, Jr, Cuddy TE, Davis BR, Geltman EM, Goldman S, Flaker GC, Klein M, Lamas GA, Packer M, Rouleau J, Rouleau JL, Rutherford J, Wertheimer JH, Hawkins CM Investigators obotS. Effect of captopril on mortality and morbidity in patients with left ventricular dysfunction after myocardial infarction. Results of the survival and ventricular enlargement trial. N Engl J Med. 1992;327:669–677. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199209033271001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kelbaek H, Gjorup T, Brynjolf I, Christensen NJ, Godtfredsen J. Acute effects of alcohol on left ventricular function in healthy subjects at rest and during upright exercise. Am J Cardiol. 1985;55:164–167. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(85)90320-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Seppa K, Sillanaukee P. Binge drinking and ambulatory blood pressure. Hypertension. 1999;33:79–82. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.33.1.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van de Wiel A, van Golde PM, Kraaijenhagen RJ, von dem Borne PA, Bouma BN, Hart HC. Acute inhibitory effect of alcohol on fibrinolysis. Eur J Clin Invest. 2001;31:164–170. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2362.2001.00773.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mukamal KJ, Maclure M, Muller JE, Mittleman MA. Binge drinking and mortality after acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2005;112:3839–3845. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.574749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bassand JP, Hamm CW, Ardissino D, Boersma E, Budaj A, Fernandez-Aviles F, Fox KA, Hasdai D, Ohman EM, Wallentin L, Wijns W. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J. 2007;28:1598–1660. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Feskanich D, Rimm EB, Giovannucci EL, Colditz GA, Stampfer MJ, Litin LB, Willett WC. Reproducibility and validity of food intake measurements from a semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire. J Am Diet Assoc. 1993;93:790–796. doi: 10.1016/0002-8223(93)91754-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]