Abstract

Background

Intimate partner violence (IPV) victims frequently seek medical treatment though rarely for IPV. Recommendations for health care providers (HCPs) include: IPV screening, counseling, and safety referral.

Objective

Report women’s experiences discussing IPV with HCPs.

Design

Structured interviews with women reporting IPV HCP discussions; descriptive analyses; bivariate and multivariate analyses and association with patient demographics and substance abuse.

Participants

Women from family court, community-based, inner-city primary care practice, and tertiary care-based outpatient psychiatric practice.

Key Results

A total 142 women participated: family court (N=44; 31%), primary care practice (N=62; 43.7%), and psychiatric practice (N=36; 25.4%) Fifty-one percent (n=72) reported HCPs knew of their IPV. Of those, 85% (n=61) told a primary care provider. Regarding IPV attitudes, 85% (n=61) found their HCP open, and 74% (n=53) knowledgeable. Regarding approaches, 71% (n= 51) believed their HCP advocated leaving the relationship. While 31% (n=22) received safety information, only 8% (n=6) received safety information and perceived their HCP as not advocating leaving the abusive relationship.

Conclusions

Half of participants disclosed IPV to their HCP’s but if they did, most perceived their provider advocated them leaving the relationship. Only 31% reported HCPs provided safety planning despite increased risks associated with leaving. We suggest healthcare providers improve safety planning with patients disclosing IPV.

Keywords: domestic violence, patient-physician communication, women’s health

Background

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is a major public health concern affecting approximately 24% of U.S. women in their lifetimes.1 Experiencing IPV is associated with negative mental and physical health outcomes and increased use of health care services.2–4 Ample research demonstrates significant financial costs to both the patient and the health care system.5 Primary care estimates of IPV prevalence range from 4.9–29% and up to nearly 50% in inner-city practices.4–13 Approximately 1/3 of women injured during their most recent physical assault received medical treatment, providing an opportunity for healthcare providers (HCPs) such as physicians, nurses, physician assistants, and nurse practitioners to intervene.14 However, most outpatient visits by women experiencing IPV are for non-injury-related complaints and most affected women do not spontaneously disclose their IPV thus, highlighting the need for comprehensive measures to identify IPV.15–16 IPV has been found to be under-documented in clinical settings.16 Interviews with HCPs17 and transcripts of patient-physician encounters18 have demonstrated that HCPs often have difficulty asking about IPV as well as addressing IPV when it is disclosed. These findings have generated numerous training tools and interventions to help HCPs better address IPV, but no study has demonstrated sustained improvements in addressing IPV in clinical practice.19–21 Sims et al15 reported no increase in IPV questioning after an educational intervention for trauma residents, suggesting that education alone may not increase IPV detection without profession-wide guidelines. Additionally, documenting IPV by using standard diagnostic codes may warrant caution given concerns for safety and confidentiality.22 In response to the accumulated evidence, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) of the National Academies and the Department of Health and Human Services have recommended culturally sensitive and supportive screening as well as counseling for current or past IPV for all women and adolescent girls.23

Nearly 20 years of research about IPV identification and HCP communication may have affected community practice standards. Recommendations have been based upon both preferences and outcomes reported by IPV survivors and include: referral to IPV specialists, safety planning, and providing non-judgmental support regardless of the woman’s decision to stay or leave the relationship.24–29 However, there is little knowledge outside of controlled educational interventions about the extent to which current medical practitioners follow expert recommendations, such as those issued by the IOM.

There is a paucity of literature on women’s comfort in discussing experiences of IPV with healthcare providers as well as the degree of confidence they have in their providers’ advice. McCauley et al.30 found women frequently cited fear of HCP response as a barrier to disclosure. A qualitative study of IPV survivors identified 5 dimensions of provider behaviors that facilitated patient trust: open communication, professional competency, accessible practice style, caring, and emotional equality.31 Another qualitative study of IPV survivors in emergency, primary care, and obstetric gynecological settings concluded that patient satisfaction was related to provider acknowledgment of the abuse, respect, and relevant referrals,32 and a quantitative experimental evaluation of a system change intervention to improve Emergency Department responses to IPV showed that ED’s screening about IPV had higher patient satisfaction than those who did not.33 Studies of women’s preferences regarding mandatory reporting indicate that abused women prefer to be given options about what actions to take, rather than being advised directly to leave an abusive partner.34–35 Although studies have addressed patient preferences, the degree of patient comfort and confidence in HCPs’ IPV knowledge and advice following such clinical discussions have not been reported. HCPs may not be knowledgeable regarding the risks of leaving the abusive relationship without a safety plan in place36 or the complexity of women’s decisions about leaving or staying and therefore may simply recommend leaving the relationship or respond judgmentally to a woman who expresses ambivalence about leaving.

The purpose of this study was to understand women’s perspectives on their experience of IPV disclosure in healthcare settings, and compare this to current expert guidelines for screening and intervention by healthcare providers.

Methods

In this study, we present the first analysis of this subsample from a larger project regarding IPV, related health care and patient attitudes (PI: Horwitz). Methods for this study are based on community-based participatory research strategies.37 The research team conducted preliminary discussions with women from a local battered women’s shelter to obtain input regarding study recruitment and methodology. These women also participated in mock structured research interviews; the research team incorporated their feedback into the study protocol and structured interview script.38

Participants and settings

Between February, 2007 and July, 2008, research assistants recruited participants from a family court, primary care practice, and a tertiary care-based outpatient psychiatric practice for a health care research project (PI Horowitz). These sites were chosen to draw a sample of women with a range of experiences in health care. We specifically included the courts to include women who might not have an identified medical home. Inclusion criteria for the study were: age greater than 18, ability to consent, and self-reported lifetime history of IPV. Participants were asked to identify one abusive relationship, either past or present, and anchor all questions being asked to that relationship.

Procedure

At both health care sites (inner city primary care practice and hospital-based psychiatric practice) primary providers were trained to screen all patients for a lifetime history of IPV using an identification tool for domestic violence that was embedded into a pre-existing practice questionnaire. Those who screened positive were invited to meet with a research assistant conducting a study regarding relationships. At the primary care practice, a poster in the patient waiting area also advertised the study.

At family court, recruiters approached potential participants in two locations: from the secure area designated for petitioners of orders of protection and from a family court reception area.

At each site, trained recruiters arranged for a private onsite interview or follow-up appointment with interested participants. Participants received a $25 cash incentive after the completed interview, a small resource card with the names and numbers of appropriate agencies to assist the patient with information about abusive relationships, and a hotline number to speak with someone as needed. Those who declined participation at any stage in the process were offered the small resource card.

Measures and analyses

The survey included questions on demographic characteristics and questions on patient interactions and discussions with HCPs on IPV.

Demographic characteristics-Participants reported their age (recoded as 18–35, 36–45, or 46–65), education (recoded as high school graduate or less, or some college or more), individual income (recoded as under $20k, or $20k or more), ethnicity (recoded as white or non-white), and substance use (yes or no to having a problem with drugs or alcohol). Substance use was included because of its associated risk with IPV.39

HCP-patient interactions regarding IPV-Based on the input of shelter participants noted above, the team developed twelve questions to assess HCP-patient driven communication regarding patients’ experiences with IPV. Participants were asked if their HCPs asked them about abuse in their intimate relationships, excluding the screen done just prior to study recruitment. They were also asked to answer questions on their HCPs’ openness, ability to help, and influence on their decision to stay or leave the abusive relationship. (See Table 2)

Table 2.

Interview responses regarding healthcare provider communication

| Question | Yes | No | No Answer |

|---|---|---|---|

| Did your healthcare provider know that physical violence or emotional abuse was occurring in your relationship? | 72 (51%) | 70 (49%) | 0 (0%) |

| If your healthcare provider had asked you about the physical violence and/or the emotional abuse in your relationship, would you have told him/her? (Asked only of participants who answered No to question 1, n=70). | 46 (66%) | 21 (30%) | 3 (4%) |

| Do you think that your healthcare provider helped you to make your decision about whether to stay or to try to leave your violent/abusive relationship? | 28 (39%) | 39 (54%) | 5 (7%) |

| Was your healthcare provider open to hearing about the violence/abuse? | 61 (85%) | 5 (7%) | 6 (8%) |

| Were you comfortable approaching him or her? | 47 (65%) | 20 (28%) | 5 (7%) |

| Do you think your healthcare provider is knowledgeable about what goes on in violent/abusive relationships? | 53 (74%) | 11 (15%) | 8 (11%) |

| Which healthcare providers knew? | -- | -- | -- |

| How did you feel about your healthcare provider knowing that physical violence and/or emotional abuse was occurring in your relationship? | -- | -- | -- |

| What was it that he/she said that was helpful to you? | -- | -- | -- |

| What was it that he/she said that was not helpful to you? | -- | -- | -- |

| Do or did you think your healthcare provider wants/wanted you to stay or to leave your violent/abusive relationship? | Leave 51(71%) |

Stay 5(7%) |

Neutral 16(22%) |

| How do you know this? | -- | -- | -- |

Data Analysis

We conducted a mixed-method analysis40 of the scribed semi-structured interviews, which we informed with selective qualitative quotes from women who found their disclosure to their HCP to be either helpful or unhelpful.

Chi-square tests were conducted to determine the associations between participant demographic and background variables and recruitment site (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographics of sample, represented by site of participation

| Demographic | N in strata | % of Respondents in Category | Family Court | Community Health Center | Behavioral health | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | % | % | |||

| Overall Sample | 142 | 31 | 43.7 | 25.4 | ||

| Race | ||||||

| Caucasian | 55 | 38.7 | 29.5 | 33.9 | 58.3 | 0.018 |

| Non-Caucasian | 87 | 61.3 | 70.5 | 66.1 | 41.7 | |

| Age | ||||||

| 18–35 | 59 | 41.5 | 65.9 | 29.0 | 33.3 | 0.001 |

| 36–45 | 45 | 31.7 | 22.7 | 41.9 | 25.0 | |

| 46–65 | 38 | 26.8 | 11.4 | 29.0 | 41.7 | |

| Educational level | ||||||

| Some college or more | 45 | 31.7 | 17 | 12 | 16 | .018 |

| High School grad or less | 97 | 63.3 | 27 | 50 | 20 | |

| Household Income* | ||||||

| ≤ $20,000 | 124 | 87.9 | 37 | 57 | 30 | .215 |

| ≥ $20,000 | 17 | 12.1 | 7 | 4 | 6 | |

| Alcohol a problem (yes) | 21 | 14.8 | 2.3 | 24.2 | 13.9 | 0.007 |

| Drugs a problem (yes) | 33 | 23.2 | 25.0 | 25.8 | 16.7 | 0.555 |

Descriptive analyses on the qualitative data were performed. For that portion of the structured interview questions that were open-ended, two individuals (one co-author and one research assistant) coded the narratives to help determine the nature of the HCP-patient communication regarding IPV. The coding was done separately and any disagreements were resolved by discussion until consensus occurred. Regarding whether the HCP directly advised the patient to stay or leave, we looked to the “How do you know?” (that your HCP wished for you to stay or leave) question (Table 2). Regarding safety advice or referral and how the HCP was helpful or unhelpful, we looked for references to that physician behavior in all the open-ended questions (Table 2).

We selected some participants’ narrative statements illustrative of the major themes regarding helpful or unhelpful HCP behaviors or statements from the structured interviews to further inform this analysis.

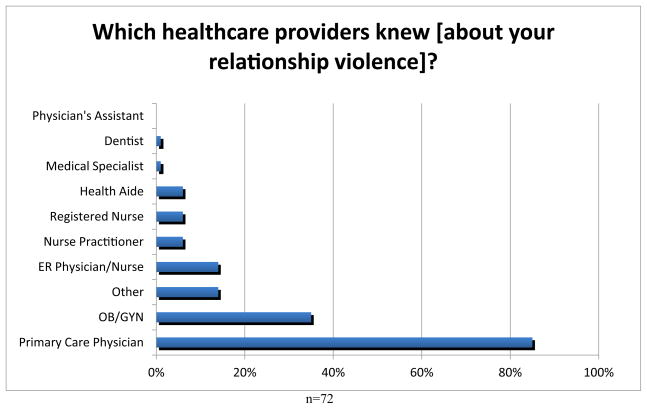

We quantified the various HCPs with whom patients discussed IPV as shown in Figure 1. To assess whether demographic characteristics were associated with HCPs asking about IPV or not, we performed multivariate logistic regression with the HCPs asking about IPV as the dependent variable and age, race, substance abuse history, and employment as independent variables on all 142 participants.

Figure 1.

Interview response percentages to question, “Which healthcare providers knew [about your relationship violence]?”

Lastly, we performed Chi square bivariate analysis with 72 participants reported discussing IPV with a HCP. We analyzed variables relating to these participants’ views of their HCPs’ attitudes, perceptions, and knowledge about the care of women in abusive relationships.

Results

Data were available from 142 of the original 150 women who took part in the health care study (we excluded 8 participants due to missing demographic data). Sixty-one percent (n=87) of the women were non-Caucasian. Participants had relatively low educational attainment with 68% (n=97) having earned a high school diploma or less and were low income with 88% (n=124) reporting an annual individual income under $20,000. Participation criteria required age range from 18 to 65 years, with 41% (n=59) between 18–35 years, 32% (n=45) between 36–45 years, and 27% (n=38) between 46–65 years.

The demographics of the sample, divided by recruitment site, is displayed in Table 1. The demographics of our participants differed by site for race, age, education, and alcohol abuse. The family court (70.5%, n=31) and primary care practice (66.1%, n=41) sites had more minority women compared to the psychiatric practice (41.7%, n=15). Family court also had a greater number of younger women (65.9%, n=29). Twenty-four percent of respondents at the primary care practice noted an alcohol problem, in contrast with only 13.9% and 2.3% at the psychiatric practice and family court sites, respectively. Differences between sites in reported drug use were not significant. Notwithstanding these differences in race, age, and alcohol abuse, we combined the samples for our subsequent analyses as they represent predominantly low income, women with histories of relationship violence.

Of the 142 female participants, fifty-one percent (n=72) reported that their HCPs knew of the abuse in their relationships (see Table 2). These HCPs included MD’s, nurses, NP’s, and PA’s. Of those participants, 65% (n=47) reported that they had been asked about IPV by a HCP, which indicates that 65% of these HCPs are following the recommended guidelines. However, in a different question only 31% (n=22) reported having volunteered information about IPV to a HCP. Eighty-five percent of the participants whose HCP knew of their abuse (n=61 total,) reported having told at least one primary care provider, including 25 who said they reported to their obstetrician-gynecologist. Of the 49% (n=70) that reported their HCPs did not know, 63% (n=44) indicated they would have disclosed if their HCPs had asked.

Logistic regression revealed that race, employment or self-reported drug use were not associated with a HCP asking about IPV. However, women aged 36–45 were almost 4 times as likely to say they had been asked (O.R. 3.99, P<.005, CI 1.53, 10.44) compared to the reference group, age 36 and under.

Of the 72 women who reported that their HCP knew about the abuse, 85% (n=61) reported their HCP was open to talking about IPV, 65% (n=47) felt comfortable approaching him/her about it, and 74% (n=53) felt their HCP was knowledgeable about the topic. (See Figure 2).

Among the 72 participants whose HCPs knew of the abuse, 71% (n= 51) reported they felt their HCPs wanted them to leave the abusive relationships and half of those (n= 27) or 37.5% of the total stated their HCP specifically advised them to leave their abusive partners (see Table 3). Twenty-five percent (n=18) of the abused women reported their HCP advised them to leave the abusive partner but did not indicate they were given any safety advice. Few participants (31%, n=22) reported safety assistance such as referral to community agencies. Only 6 women (8%) stated that HCPs offered safety advice and left the decision about leaving or staying in the abusive relationships to them. Forty-three percent (n=9) of participants recruited at site 1 reported receiving safety advice, compared with 31% (n=31) at site 3 and 21% (n=5) at site 5.

Table 3.

Responses to the question, “Do or did you think your healthcare provider wants/wanted you to stay or to leave your violent/abusive relationship?”

| Leave | Stay | Neutral | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 51 | 5 | 16 | 72 | |||

|

| ||||||

| Advised to leave | Yes | No | Total | |||

| 27 | 24 | 51 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Received safety advice | 9 | 5 | 14 | 2 | 6 | 22 |

|

| ||||||

| Did not receive safety advice | 18 | 19 | 37 | 3 | 10 | 50 |

|

| ||||||

| Advice helpful | 10 | 10 | 20 | 2 | 6 | 28 |

|

| ||||||

| Advice not helpful | 15 | 11 | 26 | 3 | 10 | 39 |

The following quotes are from participants who described the HCP as helpful:

“[My doctor] was a friend and the only one I could trust…”

“[My doctor was] compassionate, supportive. She took her time with me and spent about two hours when I broke down.”

“I felt like it helped me because [the doctor] was supporting my decision to get help…”

‘He will kill you - get out…’ [HCP statement to participant]

The following quotes are from participants who described the HCP as unhelpful:

“I felt scared that [the doctor] would report me to the police, welfare…”

“Persons in emergency brought up the situation when my husband was still there… then they asked him to leave and I was scared.”

“’All those times that you kept going back, I told you not to go back, now you are on your own.’ [HCP statement to participant] I changed doctors after that.”

“[I felt] embarrassed and unprotected. I felt like [my doctor] defended my husband.”

“I was in such denial that I didn’t want to hear any of her advice and opinions; closed ears…”

“I want to get pregnant. My OB/GYN [won’t prescribe] my meds, so I won’t get pregnant. If I leave him she will give them to me again. I have an illness that keeps me from getting pregnant.”

Discussion

In this study of 142 low-income women who have experienced IPV, half of the participants reported disclosing abuse to a HCP. Of those who disclosed IPV to a HCP, 65% did so in response to being asked; only 31% volunteered their IPV status. Among those who did not disclose to a HCP, 63% stated that they would have disclosed if they had been asked. Eighty five percent of the women who disclosed told a primary care provider. Among the women that disclosed IPV to a HCP, 71% felt that their provider wanted them to leave the relationship, with 37.5% reporting being specifically directed to leave. Among the women who disclosed to a HCP 69% were not provided safety advice. Finally, among the women who disclosed IPV to a HCP, 65–85% felt comfortable and believed their HCP to be open or knowledgeable regarding IPV. In this study, women aged 36–45 are 4 times more likely to be screened for IPV.

Most of our participants who told a HCP reported having disclosed their abuse to a primary care provider. This finding demonstrates the prominent role such providers play for these patients and supports current recommendations for primary care providers to screen for and address IPV. Importantly, women seeking orders of protection sought care at the Emergency Department at twice the rate that they utilized primary health care and 40% reported delayed medical care in the past year.38 Hence HCPs may see a patient only once, further reinforcing asking all patients about IPV even at the first visit.

Another important finding in our study is that only half of our participants had disclosed IPV to a HCP; almost two thirds of those disclosed only on being asked, and that most of those who did not disclose reported that they would have disclosed if asked. These findings support the practice of routine inquiry of all patients regarding IPV as has recently been recommended by an IOM report23, a recommendation accepted by the Secretary of DHHS. Women who have disclosed their IPV experience to a HCP have been found to be more likely to report receiving an IPV intervention, which is associated with leaving the abusive relationship and improved health outcomes.41 Not inquiring of all patients ensures that IPV will be under-detected and therefore undertreated. In order to fulfill the DHHS directives, HCP’s will benefit from using evidence based guidelines to respond to women who disclose IPV upon routine inquiry.

Among our participants 69% reported that they had not received safety advice regarding IPV, while 71% reported feeling that their HCP wanted them to leave the abusive relationship. If providers feel helpless to address the needs of women experiencing IPV, they may focus on counseling the woman to leave the abusive relationship without adequately providing information about other strategies and if the woman wants to leave, ensuring safety procedures are in place. Risk of femicide is significantly increased during the year after an abused partner leaves the abuser.36 Yet only 50% of survivors of attempted femicide reported being aware of their extreme risk, hence increasing susceptibility to possibly unsafe suggestions or a lack of adequate safety planning.43 Furthermore, some abused women report fearing providers will require them to leave an abusive relationship in order to receive help was a barrier to seeking such help, supporting the importance of our results.44

A positive finding in this study is the degree of comfort and confidence that abused women reported in their HCPs, most of whom were primary care providers, and the extent to which they looked to them for help in managing this complex situation. However, there is discordance between this confidence and the finding that HCPs rarely provided safety planning and a non-judgmental approach to the question of staying or leaving the abusive relationship. Additionally, supporting patients’ autonomy to make their own choices is associated with other positive outcomes such as improvements in satisfaction, well-being, and change associated with intrinsic rather than extrinsic motivation.45–46

Our finding that participants perceived their HCP to be advocating leaving the abusive relationship raises the question of whether someone who becomes aware of a dangerous situation (physically and/or emotionally) would not reasonably want them to leave it. It also raises the question of whether those participants who were not directly advised to leave may have assumed such it because it is reasonable. The fundamental question is whether someone can be supportive of a patient making her own decision and still want her to change her situation. Research on motivation with a reasonable desire for change by a HCP regarding substance abuse and following medical recommendations helps to address these questions, Empathy, information, and support can be provided to increase autonomy and perceived competence, consequently improving health outcomes.47–49 Qualitative research among the IPV survivor population supports the notion that respectful information-sharing and support by HCPs will help break the cycle of control, degradation, and physical violence that constitutes IPV.28–31

In July 2011 the IOM recommended universal IPV screening, noting the prevalence of IPV and the need to address current and future health risks.23 Nevertheless, there has been a lack of consensus regarding the utility of screening women for IPV.50 It is possible that one reason for the lack of clear efficacy of some screening interventions relates to the difficulty HCPs have with the complex and numerous tasks that have been suggested when the patient screens positively, such as assessing mechanisms of injury and child safety.51 Clinical practice, policy, and research implications of this study would be to focus on establishing fewer HCP responses to a determination of ongoing IPV. In this study, participants reported that HCPs conveyed support as has been suggested by IPV survivors29 but did less well with safety-related suggestions. Hence focusing educational efforts on HCPs providing a referral to a trained IPV provider at a local shelter or a national toll free hotline (1-800-799-SAFE(7233)52 may be the appropriate strategy for primary care providers with multiple important tasks. Research regarding such a strategy could be important as well.

Our results suggest that patients look to their HCP for guidance and information, giving HCPs an opportunity to respectfully educate women to seek safety planning and impact their ability to make positive change. The cumulative evidence suggests that after such referrals, HCPs should support patients’ choices, and decrease the focus on leaving the abusive relationship until resources are present to help avoid potentially serious harm.

A strength of this study is that women were recruited from different sites. While other papers have focused on patient responses to HCPs in primary or emergency medical settings,18, 31 ours broadens the population studied and adds to the literature by including participants recruited from two sites where biomedical care was not being obtained. Some differences by site were noted (Table 1) with regard to ethnicity and age. The family court sample was seeking an order of protection and was more likely to be younger, non-Caucasian. Whereas the psychiatric practice clinic sample was likelier to be older and Caucasian. The primary health care population was less likely to have some college education, had a lower income and was more likely to have an alcohol problem. These findings support our belief that we have assembled a diverse population. A larger sample may be needed to determine associated differences in IPV communication beyond the finding of women in the middle age range being more likely to be asked about IPV by a HCP.

Our results should be considered with caution. This study is based upon patient report. Other studies have utilized audiotape, videotape, or chart review to document actual HCP behaviors. This study focuses more on diverse patients’ perceptions of and response to community HCPs’ behaviors. Another limitation of this study is the lack of a qualitative thematic analysis of participant comments. Because such an analysis was not the purpose of this study, the depth and breadth of responses needed for such an analysis were not obtained.

Future studies could aim to test specific hypotheses regarding interactions between patient characteristics, HCP behaviors, and patient attitudes towards their HCPs. For example, do patient race, education, and income affect the likelihood that HCPs will ask about IPV? Would HCPs asking about IPV increase patient comfort and confidence and could that lead to an increase in needed health services utilization? If HCPs were trained to support patient autonomy regarding their decisions to stay or leave the abusive relationship, would this improve patient motivation to increase controllable safety behaviors? 53 These important questions have yet to be addressed.

Conclusions

Among our diverse sample of women IPV survivors, only half felt comfortable enough to disclose IPV to a HCP. Among the half that did not disclose, 63% would have done so if they’d been asked. For the half that did disclose, almost three fourths thought that their HCP wanted them to leave the relationship and only 31% received safety information. These findings contrast with over three fourths of the survivors believing their HCPs to be knowledgeable about abuse. While limited in sample size, our results have implications for provider training and for new hypotheses that can be studied in larger intervention studies.

Acknowledgments

Funding: NIMH T32 MH18911, NIMH K01MH75965-01, NIMH K01MH080660-01A2, McGowan Foundation.

Project design and implementation: Susan H. Horwitz, Ph.D., LMFT (PI for McGowan project), Michelle LaRussa-Trott, LMSW, Joan Pearson, MA, MS, LMFT, Lizette Santiago, MS, LMFT, David Skiff, Ph.D., M.Div., LMSW

Interviewers: Lorena Billone, BA, MFTT, Jessica Bougie, BA, Stacy Kolb-Tripp, MS

Statistical consultant: Harry Reis, PhD

Data entry and management: Meaghan Bernstein and Jessica Band

Manuscript review: Jacqueline Campbell, PhD., RN

This project would not have been possible without the support of many administrators, mentors, and most importantly, participants. Special thanks to the organizations, Safer and Delphi, who assisted this study in the design prior to implementation.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest in this study.

Contributor Information

Diane S. Morse, Email: diane_morse@urmc.rochester.edu, University of Rochester School of Medicine

Ross Lafleur, Email: rmlafleur@gmail.com, University of Rochester School of Medicine.

Colleen T. Fogarty, Email: colleen_fogarty@urmc.rochester.edu, University of Rochester School of Medicine

Mona Mittal, Email: mona_mittal@urmc.rochester.edu, University of Rochester School of Medicine.

Catherine Cerulli, Email: catherine_cerulli@urmc.rochester.edu, University of Rochester School of Medicine.

References

- 1.Breiding MJ, Black MC, Ryan GW. Prevalence and risk factors of intimate partner violence in eighteen U.S. states/territories, 2005. Am J Prev Med. 2008;34(2):112–118. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bonomi AE, Anderson M, Reid RJ, Rivara FP, Carrell D, Thompson RS. Medical and psychosocial diagnoses in women with a history of intimate partner violence. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(18):1692–1697. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen PH, Rovi S, Vega M, Jacobs A, Johnson MS. Relation of domestic violence to health status among hispanic women. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2009;20(2):569–582. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thompson RS, Bonomi AE, Anderson M, et al. Intimate partner violence: Prevalence, types, and chronicity in adult women. Am J Prev Med. 2006;30(6):447–457. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bonomi AE, Anderson ML, Rivara FP, Thompson RS. Health care utilization and costs associated with physical and nonphysical-only intimate partner violence. Health Services Research. 2009;44(3):1052–1067. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2009.00955.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Freund KM, Bak SM, Blackhall L. Identifying domestic violence in primary care practice. J Gen Intern Med. 1996;11(1):44–46. doi: 10.1007/BF02603485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gin NE, Rucker L, Frayne S, Cygan R, Hubbell FA. Prevalence of domestic violence among patients in three ambulatory care internal medicine clinics. J Gen Intern Med. 1991;6(4):317–322. doi: 10.1007/BF02597429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rath GD, Jarratt LG, Leonardson G. Rates of domestic violence against adult women by men partners. J Am Board Fam Pract. 1989;2(4):227–233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bullock L, McFarlane J, Bateman LH, Miller V. The prevalence and characteristics of battered women in a primary care setting. Nurse Pract. 1989;14(6):47, 50, 53–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coker AL, Smith PH, McKeown RE, King MJ. Frequency and correlates of intimate partner violence by type: Physical, sexual, and psychological battering. Am J Public Health. 2000;90(4):553–559. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.4.553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coker AL, Flerx VC, Smith PH, Whitaker DJ, Fadden MK, Williams M. Intimate partner violence incidence and continuation in a primary care screening program. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;165(7):821–827. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwk074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.El-Bassel N, Gilbert L, Witte S, et al. Intimate partner violence and substance abuse among minority women receiving care from an inner-city emergency department. Women’s Health Issues. 2003;13(1):16–23. doi: 10.1016/s1049-3867(02)00142-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Porcerelli JH, Cogan R, West PP, et al. Violent victimization of women and men: Physical and psychiatric symptoms. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2003;16(1):32–39. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.16.1.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tjaden P, Thoennes N. Full Report of the Prevalence, Incidence, and Consequences of Violence Against Women: Findings From the National Violence Against Women Survey. Washington, DC: Department of Justice, National Institute of Justice; 2000. NCJ 183781. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sims C, Sabra D, Bergey MR, et al. Detecting intimate partner violence: More than trauma team education is needed. J Am Coll Surg. 2011;212(5):867–872. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2011.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kothari CL, Rhodes KV. Missed opportunities: Emergency department visits by police-identified victims of intimate partner violence. Ann Emerg Med. 2006;47(2):190–199. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2005.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sugg NK, Inui T. Primary care physicians’ response to domestic violence. Opening Pandora’s box. JAMA. 1992;267(23):3157–3160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rhodes KV, Frankel RM, Levinthal N, Prenoveau E, Bailey J, Levinson W. “You’re not a victim of domestic violence, are you?” Provider patient communication about domestic violence. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(9):620–627. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-9-200711060-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nicolaidis C. The voices of survivors documentary: Using patient narrative to educate physicians about domestic violence. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17(2):117–124. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10713.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Edwardsen EA, Morse DS, Frankel RM. Structured practice opportunities with a mnemonic affect medical student interviewing skills for intimate partner violence. Teach Learn Med. 2006;18(1):62–68. doi: 10.1207/s15328015tlm1801_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McColgan MD, Cruz M, McKee J, et al. Results of a multifaceted intimate partner violence training program for pediatric residents. Child Abuse Negl. 2010;34(4):275–283. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rovi S, Johnson MS. More harm than good? Diagnostic codes for child and adult abuse. Violence Vict. 2003;18(5):491–502. doi: 10.1891/vivi.2003.18.5.491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Institute of Medicine of the National Academies. Clinical preventive services for women: Closing the gaps. Institute of Medicine of the National Academies; Jul 19, 2011. [Accessed 23 November 2011]. Available at http://www.iom.edu/Reports/2011/Clinical-Preventive-Services-for-Women-Closing-the-Gaps/Report-Brief.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rhodes KV, Levinson W. Interventions for intimate partner violence against women: Clinical applications. JAMA. 2003;289(5):601–605. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.5.601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gerbert B, Caspers N, Bronstone A, Moe J, Abercrombie P. A qualitative analysis of how physicians with expertise in domestic violence approach the identification of victims. Ann Intern Med. 1999;131(8):578–584. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-131-8-199910190-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Du Plat-Jones J. Domestic violence: The role of health professionals. Nurs Stand. 2006;21(14–16):44–48. doi: 10.7748/ns2006.12.21.14.44.c6392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kaur G, Herbert L. Recognizing and intervening in intimate partner violence. Cleve Clin J Med. 2005;72(5):406–9. 413–4, 417. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.72.5.406. passim. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chang JC, Decker MR, Moracco KE, Martin SL, Petersen R, Frasier PY. Asking about intimate partner violence: Advice from female survivors to health care providers. Patient Educ Couns. 2005;59(2):141–147. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2004.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Feder GS, Hutson M, Ramsay J, Taket AR. Women exposed to intimate partner violence: Expectations and experiences when they encounter health care professionals: A meta-analysis of qualitative studies. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(1):22–37. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.1.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McCauley J, Yurk RA, Jenckes MW, Ford DE. Inside “Pandora’s box”: Abused women’s experiences with clinicians and health services. J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13(8):549–555. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1998.00166.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Battaglia TA, Finley E, Liebschutz JM. Survivors of intimate partner violence speak out: Trust in the patient-provider relationship. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18(8):617–623. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.21013.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liebschutz J, Battaglia T, Finley E, Averbuch T. Disclosing intimate partner violence to health care clinicians - what a difference the setting makes: A qualitative study. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:229. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Campbell JC, Coben JH, McLoughlin E, et al. An evaluation of a system-change training model to improve emergency department response to battered women. Acad Emerg Med. 2001;8(2):131–138. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2001.tb01277.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gielen AC, O’Campo PJ, Campbell JC, et al. Women’s opinions about domestic violence screening and mandatory reporting. Am J Prev Med. 2000;19(4):279–285. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(00)00234-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sachs CJ, Koziol-McLain J, Glass N, Webster D, Campbell J. A population-based survey assessing support for mandatory domestic violence reporting by health care personnel. Women Health. 2002;35(2–3):121–133. doi: 10.1300/J013v35n02_08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Campbell JC, Webster D, Koziol-McLain J, et al. Risk factors for femicide in abusive relationships: Results from a multisite case control study. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(7):1089–1097. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.7.1089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Israel BA, Coombe CM, Cheezum RR, et al. Community-based participatory research: A capacity-building approach for policy advocacy aimed at eliminating health disparities. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(11):2094–2102. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.170506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cerulli C, Edwardsen EA, Duda J, Conner KR, Caine E. Protection order petitioners’ health care utilization. Violence Against Women. 2010;16(6):679–690. doi: 10.1177/1077801210370028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kilpatrick DG, Acierno R, Resnick HS, Saunders BE, Best CL. A 2-year longitudinal analysis of the relationships between violent assault and substance use in women. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1997;65(5):834–847. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.5.834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Creswell JW, Clark V. Designing and conducting mixed methods research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 41.McCloskey LA, Lichter E, Williams C, Gerber M, Wittenberg E, Ganz M. Assessing intimate partner violence in health care settings leads to women’s receipt of interventions and improved health. Public Health Rep. 2006;121(4):435–444. doi: 10.1177/003335490612100412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Abramsky T, Watts CH, Garcia-Moreno C, et al. What factors are associated with recent intimate partner violence? Findings from the WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:109. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nicolaidis C, Curry MA, Ulrich Y, et al. Could we have known? A qualitative analysis of data from women who survived an attempted homicide by an intimate partner. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18(10):788–794. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.21202.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fugate M, Landis L, Riordan K, Naureckas S, Engel B. Barriers to domestic violence help seeking: Implications for intervention. Violence Against Women. 2005;11(3):290–310. doi: 10.1177/1077801204271959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Williams GC, McGregor HA, King D, Nelson CC, Glasgow RE. Variation in perceived competence, glycemic control, and patient satisfaction: Relationship to autonomy support from physicians. Patient Educ Couns. 2005;57(1):39–45. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2004.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Silva MN, Vieira PN, Coutinho S, et al. Using self-determination theory to promote physical activity and weight control: A randomized controlled trial in women. J Behav Med. 2010;33(2):110–122. doi: 10.1007/s10865-009-9239-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zeldman A, Ryan RM, Fiscella K. Client motivation, autonomy support and entity beliefs: Their role in methadone maintenance treatment. J Soc Clin Psychol. 2004;23(5):675–696. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Williams GC, Niemiec CP, Patrick H, Ryan RM, Deci EL. The importance of supporting autonomy and perceived competence in facilitating long-term tobacco abstinence. Ann Behav Med. 2009;37(3):315–324. doi: 10.1007/s12160-009-9090-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Williams GC, Patrick H, Niemiec CP, et al. Reducing the health risks of diabetes: How self-determination theory may help improve medication adherence and quality of life. Diabetes Educ. 2009;35(3):484–492. doi: 10.1177/0145721709333856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.U. S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for family and intimate partner violence: Recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140(5):382–386. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-5-200403020-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hamberger LK, Ambuel B, Marbella A, Donze J. Physician interaction with battered women: The women’s perspective. Arch Fam Med. 1998;7(6):575–582. doi: 10.1001/archfami.7.6.575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. [Accessed 12 May 2011];National Domestic Violence Hotline. Available at http://www.thehotline.org/

- 53.Sheldon KM, Williams GC, Joiner T. Self-determination theory in the clinic: Motivating physical and mental health. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]