Abstract

Entry of blood-borne pathogens into the spleen elicits a series of changes in cellular architecture that culminates in the systemic release of protective antibodies. Despite an abundance of work that has characterized these processes, the regulatory mechanisms that coordinate cell trafficking and antibody production are still poorly understood. Here, marginal zone (MZ) B cells responding to streptococcus in the blood were observed to migrate along splenic nerves, arriving at the red pulp venous sinuses where they become antibody-secreting cells. Electrical stimulation of the vagus nerve, which in turn regulates the splenic nerve, arrested B-cell migration and decreased antibody secretion. Thus, neural circuits regulate the first wave of antibody production following B-cell exposure to blood-borne antigen.

INTRODUCTION

Pneumococcal (PC) disease is second only to influenza as the most common cause of vaccine-preventable death in the United States. The humoral response to blood-borne Streptococcus pneumoniae is a T cell-independent response that occurs almost exclusively in the spleen. Phosphorylcholine, the immunodominant antigenic epitope in pneumococcal polysaccharide, elicits B-cell production of anti-PC antibodies required for protective immunity (1). During pneumococcal invasion, neutrophils, monocytes and dendritic cells (DC) capture and transport the bacteria to the spleen, where resident antigen-specific marginal zone B cells (MZB) and B1 cells are activated (2,3,4). These activated B cells differentiate into antibody-secreting cells, a process that involves the reexpression of syndecan-1 (CD138) and the downregulation of adhesion molecules (5,6). Finally, the antibody-secreting cells migrate along reticular fibers to the red pulp (RP) (7), where they release antibodies into the blood (8,9). MZ and B1 B cells have a preactivated phenotype and express membrane immunoglobulins mainly of the immunoglobulin M (IgM) isotype (10); thus, they can initiate a rapid antibody response to bacterial polysaccharide which is detectable in the serum as early as 48 h after infection (8). These critical steps underlying B-cell activation and migration are key to efficient secretion of antibodies, which is necessary to confer significant protection against life-threatening infections from encapsulated bacteria (11). Disruption of these mechanisms, as occurs in splenectomized individuals, young children, the elderly and in transgenic animals lacking the chemokines or integrins that participate in the activation and migration of MZ cells, are associated with significant morbidity and mortality (12–15).

Importantly, the strongest independent risk factor for invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) among immunocompetent adults is cigarette smoking (16). Smokers account for approximately half of otherwise healthy adult patients with invasive pneumococcal disease and exhibit antibody titers to pneumococcal vaccination that are attenuated by 20% to 30% (17). Cigarette smoking alters mucociliary clearance, which increases adherence of bacteria, disrupts epithelium and alters nasopharyngeal colonization (18,19). These factors are not sufficient, however, to explain the increased risk for invasive disease. Accordingly, it has been suggested that other mechanisms likely play a significant role in increasing the risk of IPD in smokers (17,20).

Cigarette smoke contains nicotine, a cholinergic agonist with strong immunomodulatory capabilities. We and others have demonstrated that nicotine signaling through the α 7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunit (α7nAChR) stimulates the cholinergic antiinflammatory pathway, a vagus neural circuit that significantly inhibits the release of TNF and other cytokines in the spleen (21). Electrical stimulation of the vagus nerve or splenic nerve downregulates cytokine production in the spleen in acute and chronic models of systemic inflammation (22,23). Moreover, cholinergic and adrenergic neurotransmitters modulate B-cell function by interacting with specific neurotransmitter receptors that modulate B-cell activation and migration responses (24,25). Accordingly, we reasoned that neural signals mediated through the α7nAChR may diminish the antibody response to PC. The data presented show that vagus nerve stimulation or administration of nicotine significantly diminished the initial antibody response against heat-killed pneumococcus, to a degree quantitatively similar to that observed in human smokers, by a mechanism that arrests B-cell migration in the MZ.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice

Female 6- to 8-wk-old Balb/C from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME, USA) were housed under pathogen-free conditions. Mice were injected intraperitoneally (i.p.) with 1 mg/kg of nicotine Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) or 40 mg/kg of 3-[(2,4-dimethoxy)benzylidene]-anabaseine dihydrochloride (DMXBA; GTS-21) (26) as a single injection or daily for up to 17 d. In some experiments, animals received a 1 mg/kg i.p. injection of mecamylamine hydrochloride (Sigma-Aldrich) 20 min before injections of nicotine.

Bacteria and Immunization/Infection

Streptococcus pneumonia strains R363 or ATCC 6303 were grown and inactivated as described previously (27). Briefly, R363 bacteria were grown to log phase in Todd Hewitt media containing 0.5% yeast extract and blood agar for 24 h at 3°C. Serotype 3 ATCC 6303 strain bacteria were grown in Trypticase soy agar with 5% defibrinated sheep blood or brain heart infusion (BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. Subsequently, the bacteria were pelleted, heat killed in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) at 56°C for 45 min and further digested in a 0.2% pepsin solution for 2 h at 37°C. The pH was neutralized with 1N NaOH. The cells were washed with PBS and the concentration was determined by measuring the optical density: 1 O.D. = 2 × 108 colony forming units (CFU)/mL. Bacteria stocks were kept at −20°C until use. Mice were injected intravenously (i.v.) (retro-orbital) with a suspension of 1 × 109 CFU/animal in 100 μL of saline and euthanized 15 min to 17 d after the bacterial challenge. For live bacteria injections, pneumococcus were injected at an approximate concentration of 1 × 105 CFU/mouse as described previously (28). Mice were euthanized 15 min after the injection.

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

PC-specific antibody titers were measured by adding serum samples to plates coated with phosphorylcholine- conjugated keyhole limpet hemocyanin (PC-KLH) 10 μg/mL in PBS overnight at 4°C. Selected serum samples were calibrated using mouse IgM of known concentration as a standard to determine the antibody concentration in μg/mL relatively, and these samples were utilized as reference in all subsequent experiments. ELISAs were performed using a 1:1000 dilution of an alkaline phosphatase (AP)-conjugated anti-mouse IgM antibody. Endpoint readings were performed using a Victor spectrophotometer (EGG-Wallac).

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Spot (ELISpot)

Enrichment of splenic B cells was accomplished by negative selection using magnetic streptavidin-coated Dynabeads (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The following biotinylated antibodies were incubated with the splenocytes for 30 min at 4°C: CD3e, CD11c, NK1.1, F4/80, CD43, CD90.2 before magnetic separation. Unbound cells were collected, washed twice with PBS and stained with anti-CD19 fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) and anti-CD138 phycoerythrin (PE) antibodies for 30 min at 4°C for cell sorting. CD19+ cells were sorted into CD138+ and CD138- populations and 1 × 105 cells were added into each well of a 96-well plate that had been coated with PC-KLH at a final concentration of 10 μg/mL in PBS overnight at 4°C, washed with PBS/0.1% Tween-20 and blocked with RPMI containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) for 1 h at 37°C. Cells were incubated overnight at 37°C. After washing with PBS/0.1% Tween-20, 100 μL/well of a 1:100 dilution of an AP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgM were added to each well and incubated for 1 h at 37°C. The plates were washed and developed using a 1 mg/mL solution of 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate disodium salt (5-BCIP) in filtered AMP buffer 0.203 g MgCl2.6H20, 0.1 mL Triton-X 405, 95.8 mL 2-amino-2-methyl-1-propanol (AMP), (pH 9.8). High resolution pictures of the plates were obtained with a digital camera and quantification of TIFF pictures was performed using the colony counting function of the Quantity One software (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA).

Flow Cytometry

Total splenocytes were incubated with the following anti-mouse antibodies: CD19 and Gr-1 (eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA), B220-PerCP and CXCR4-AF647 (Biolegend, San Diego, CA, USA), CD138-PE, CD11b-PE, Ly6G-FITC, IgM-APC (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA, USA), CD49d-FITC (Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA). FcR binding was prevented by incubating with a 1:500 dilution of the 2.4G2 antibodies. Analysis was performed using an LSR-II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences).

Electrical Stimulation of the Vagus Nerve

Mice were anesthetized with 100 mg/kg ketamine and 10 mg/kg xylazine intramuscular (i.m.). Vagus nerve stimulation was performed during 2.5 min as described previously. Briefly, electrical stimulation (1 V, 2 ms, 5 Hz) was performed using a stimulation module (STM100A) under the control of the AcqKnowledge software (Biopac Systems, Goleta, CA, USA) through a bipolar platinum electrode (Plastics One, Roanoke, VA, USA) laced across the isolated left cervical vagus nerve. Immediately after nerve stimulation, mice were immunized as indicated above, with 1 × 109 CFU/mouse in 100 μL of saline and euthanized 15 min later. Control mice were subjected to sham surgery in which the vagus nerve was exposed, but not manipulated.

Chemical Ablation of Catecholaminergic Nerves

6-hydroxydopamine (6-OHDA) (Sigma-Aldrich) in 0.9% NaCl containing 0.1% ascorbic acid (Sigma-Aldrich) was administered intraperitoneally on d –7 (100 μg/kg), –5 and –3 (200 μg/kg) before immunization. Control animals were injected with 0.1% ascorbic acid in 0.9% NaCl. Catecholamine depletion was confirmed by histofluorescence using the sucrose-phosphate-glycoxylic acid method as described previously (29).

Surgical Ablation of the Splenic Nerve

Mice were anesthetized with 2% isoflurane and a left lateral abdominal incision was performed. The branches of the splenic nerve, which travel along the splenic artery, were isolated and dissected using forceps. The splenic nerve was transected along the branches of the splenic artery close to the spleen hilum. Finally, the abdominal wall was closed and the immunization procedure was performed as described above 7 d after the surgical procedure, which is the time required for complete degeneration of splenic nerve endings.

Immunohistochemistry

Frozen spleen sections mounted on glass slides were fixed in acetone, rehydrated in PBS and incubated with a 1:500 dilution of an unlabeled anti-FcR antibody in PBS/0.5% BSA for 30 min. Subsequently, the sections were incubated for 1 h at room temperature with the following antibodies at a 1:100 dilution in PBS: synaptophysin, retinaldehyde dehydrogenase (RALDH), CD49d (Abcam), CD138-PE, CD1d-PE, CD31-PE, CD11c-PB and MOMA-1-FITC (BD Biosciences), B220-Pacific blue (eBioscience), specific intracellular adhesion molecule-grabbing nonintegrin receptor 1 (SIGN-R1)-biotin (Novus Biologicals, Littleton, CO, USA), laminin (Sigma-Aldrich), fibronectin- biotin (Rockland Immunochemicals, Gilbertsville, PA, USA). Slides were washed and mounted using Dako fluorescent mounting media (Dako, Carpinteria, CA, USA) and imaged using a Hamamatsu ORCA + ER digital camera attached to an Axioplan2 Zeiss upright fluorescence microscope. Image acquisition and analysis was performed using the Openlab 4.0.4 software.

Dextran Injections

Mice were injected i.v. with a solution of 1 mg/mL of FITC-conjugated 40S-Dextran (Sigma-Aldrich) along with heat-killed pneumococcus as described above, 5 min after an i.p. injection of saline or 1 mg/kg of nicotine. Mice were euthanized 1 h after injection and the spleens dissected and processed for immunohistochemistry as before.

All supplementary materials are available online at www.molmed.org.

RESULTS

Nicotine Impairs Humoral Immune Responses Via the Vagus and Splenic Nerves

It has been demonstrated clearly that vagus nerve stimulation can modulate aspects of the innate immune response. T-independent B-cell responses constitute the humoral arm of the innate response, as they occur quickly after antigen exposure and do not lead to memory cell formation. To address the question of whether neural signals alter the humoral immune response in vivo, we explored the T-independent response to intravenous heat-killed Streptococcus pneumoniae after administration of nicotine, a cholinergic agonist. Mice were injected i.p. with a daily dose of 1 mg/kg of nicotine or saline as a control, starting 1 d before exposure to Streptococcus pneumoniae (109 CFU/mouse) and continuing daily for up to 17 d. Nicotine injection resulted in a 49.5% reduction in the number of anti-PC antibody secreting cells in spleens as determined by ELISpot assay on d 6 after immunization (Figure 1A). We observed significantly lower serum antibody titers at d 3 and d 6 after immunization in animals receiving nicotine compared with saline controls (Figures 1B–C). Although less pronounced, a decrease in antibody titers was observed with doses of nicotine as low as 400 μg/mL (not shown).

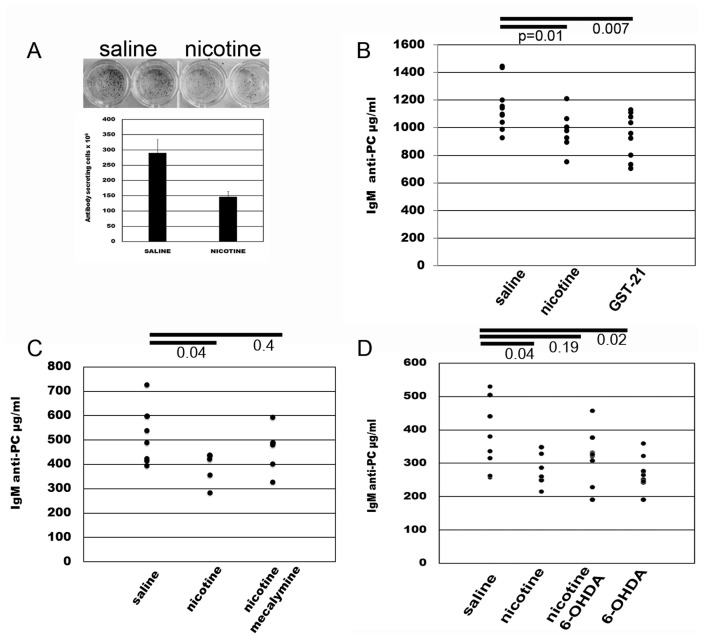

Figure 1.

Pharmacological stimulation of the cholinergic antiinflammatory pathway dampens the antibody response to heat-killed pneumococcus. (A) Mice injected daily i.p. with 1 mg/kg of nicotine, 40 mg/kg/d of the α7 nicotinic receptor agonist GTS-21, or saline as a control, starting 1 d before i.v. immunization with Streptococcus pneumoniae (109 CFU/mouse). The number of specific ASCs was determined by ELISpot assay on PC-coated plates on d 6 after immunization. (B) Serum levels of anti-PC antibodies were determined by ELISA at d 6 after immunization. (C) Mice immunized with Streptococcus pneumoniae and injected with the nicotinic receptor antagonist mecamylamine at 1 mg/kg/d 20 min before each nicotine injection. Nicotine/mecalymine injections started 1 d before immunization and continued daily for 3 d. Serum was obtained at d 3 after immunization. (D) Mice were immunized with heat-killed pneumococcus after treatment with three doses of 6-hydroxydomapine (6-OHDA) injected 48 h apart from each other on d –7, –5 and –3 before immunization. Antibody levels were determined at d 3 after immunization. Data representative of two independent experiments with five mice per group. Numbers represent P values, unpaired, two-tailed Student t test. Error bars, s.d.

Nicotine is a relatively nonselective agonist for the larger class of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. To confirm the specific role of α7nAChR, we next utilized the selective α7nAChR agonist, 3-[(2,4-dimethoxy)benzylidene]-anabaseine dihydrochloride (DMXBA; GTS-21) (26). Administration of GTS-21 significantly decreased antibody titers to a magnitude similar to nicotine (see Figure 1B). Further, administration of the nicotinic receptor antagonist mecamylamine 20 min prior to nicotine dosing (see Figure 1C) significantly reversed the effect of nicotine on antibody production. Together, these results indicate that nicotinic signaling modulates innate antibody responses through α7nACh.

The cholinergic antiinflammatory pathway is a two neuron circuit (30). Action potentials originating in the vagus nerve propagate to and terminate at the celiac ganglion, where the cell bodies of the postganglionic secondary neurons reside. These give rise to the splenic nerve, the only nerve to the spleen, which is adrenergic (31). To determine the participation of the adrenergic splenic neurons in modulating the antibody response to pneumococcus, we exposed mice to three doses of 6-hydroxydopamine (6-OHDA), to chemically ablate splenic adrenergic neurons. Injections were given 48 h apart on d –7, –5 and –3 before administration of pneumococcus on d 0. The effectiveness of adrenergic neuronal ablation was established by histofluorescence (Supplementary Figure 1). Chemical ablation of splenic nerves decreased antibody titers significantly, an observation that was expected from previous work showing that adrenergic signaling maintains the integrity of an antibody response (31). Importantly, chemical splenic nerve ablation reversed the effect of nicotine on inhibiting antibody levels significantly, confirming that the cholinergic antiinflammatory pathway inhibits the antibody responses to PC (Figure 1D).

Cholinergic Stimulation Induces Accumulation of Cells in the MZ at Early Time Points

To understand the mechanism by which neural signals regulate the anti-pneumococcal antibody response, we studied early trafficking, distribution and adhesion molecule expression of leukocytes participating in the activation of B cells. Spleen sections were prepared from tissue obtained 15 min to 4 h after nicotine injection and antigen challenge. MZB are known to be retained in the MZ by adhesion of the integrins leukocyte-function adhesion molecule-1 (LFA-1), a member of the β2 family and α4β1 very late antigen-4; (VLA-4) to intracellular-adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) and vascular cell-adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1), respectively 6). In contrast, B1b cells, monocytes and neutrophils express the αMβ2 integrin ITGAM, CD11b, (Mac-1). As is the case with other leukocytes, activated MZB need to downregulate these integrins to exit the MZ (6).

Cells expressing CD49d, the α-4 subunit of VLA-4, were distributed sparsely in the RP and the outer MZ of spleens from nonimmunized mice. CD11b, the α subunit of αMβ2, showed a similar distribution in the RP with clear expression on cells in the inner MZ (MOMA-1+ area) (Figure 2A). In saline-injected mice, 15 min after antigen exposure, most CD49d+ cells were found in small clusters in the RP and, less frequently, in the MZ (~20% of the follicles). CD11b+ cells clustered in the RP and almost completely disappeared from the inner MZ upon antigen challenge. Both cell subsets were frequently observed to cluster together (Figure 2B, arrow). In contrast, in nicotine-exposed mice, CD49d+ cells accumulated in the MZ in approximately 80% of the follicles (Figures 2C, D). The clusters of CD49d+ cells were in close contact with aggregates of CD11b+ cells, but CD11b+ cells were largely single positive, suggesting the presence of two closely localized but discrete populations (see Figure 2C).

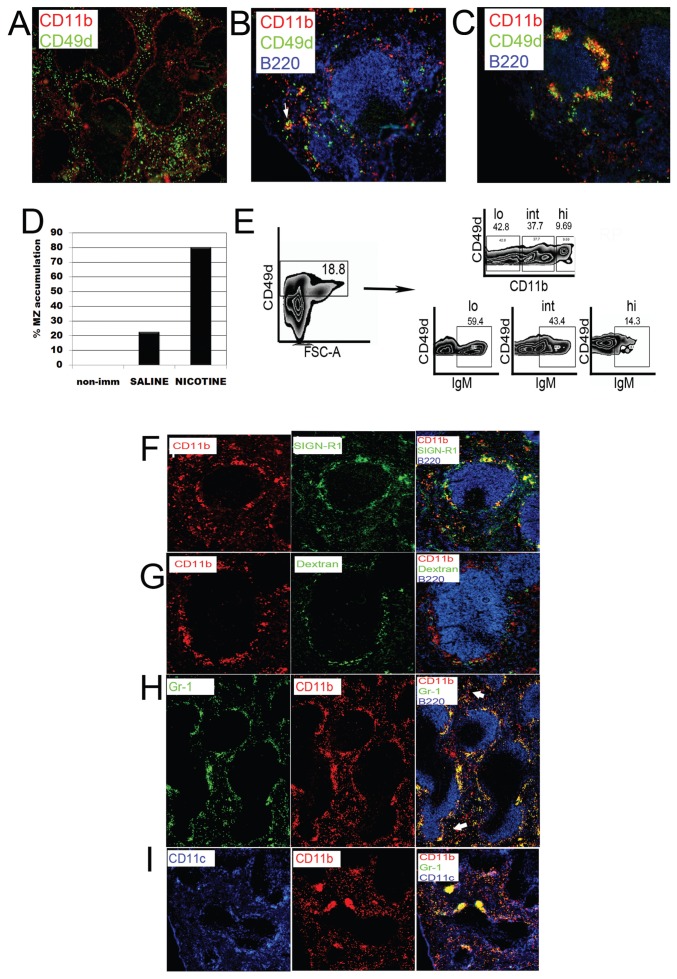

Figure 2.

Migratory arrest in the marginal zone of nicotine-treated animals. Spleen sections from nonimmunized (A) saline (B) or nicotine-injected (C) animals stained for CD49d, CD11b and B220 15 min after immunization. Red pulp clusters of CD49d+ with CD11b+ cells are marked with thin arrows; marginal zone is marked with thick arrow. (D) One hundred follicles from at least three spleen sections from nonimmunized or immunized mice treated with saline or nicotine were counted to determine the number of follicles containing aggregated cells. (E) Total splenocytes were obtained from spleens of saline-injected, immunized animals and analyzed by flow cytometry. IgM expression levels were determined on CD49d+ cells according to the different levels of expression of CD11b. Data representative of three independent experiments. (F) Spleen sections of nicotine-treated animals stained for CD11b, SIGN-R1 and B220 antibody. The image on the right column was obtained by superimposing all three channels using the Openlab software, for example. (G) Fluoresceinated dextran was injected 1 h before nicotine and antigen challenge. Spleens sections were stained for CD11b and B220. (H) Spleen sections of nicotine-treated animals stained for CD11b, Gr-1 and B220. Arrows indicate CD11b+ cells that are negative for Gr-1 outside the MZ. (I) Spleen sections of nicotine-treated animals stained for CD11b, Gr-1 and CD11c. Images representative of at least five animals per group. All images are representative of three independent experiments and at least five animals per group.

To confirm that the CD49d+ cells accumulating in the MZ of nicotine-treated animals were activated B cells, we determined their expression of CD19, B220 and IgM by flow cytometry. Approximately 18.8% of total splenocytes of immunized animals were CD49d+ (Figure 2E). Among the CD49d+ cells in the population with higher forward scatter in the histogram shown on the left, more than 80% of the cells were IgM and CD19+ (not shown). These results demonstrated that nicotine mediates the retention of CD49d+ B cells in the MZ.

Histologic analysis of the spleen showed that the CD11bhi cells arrested in the MZ of nicotine-treated mice were monocytes and neutrophils that localize in close contact with marginal zone macrophages (MZM) and CD49d+ B cells (5). Few CD11b+ cells were positive for the MZM marker and pneumococcal polysaccharide receptor SIGN-R1 (Figure 2F). To confirm this observation, FITC-labeled dextran, which is phagocytized by SIGN-R1+ MZM, was administered to mice 1 h before nicotine or saline injection and antigen challenge. As shown in Figure 2G, green fluorescently labeled cells that had ingested dextran were distinct from CD11b+ cells confirming that MZM differ from these CD11b+ cells (Supplementary Figures 2C, D). Gr1+ (Ly6G+/Ly6C+) neutrophils accumulated in the MZ after nicotine administration (Figures 2H, I and Supplementary Figure 3A). Many of these ingested dextran (Supplementary Figures 2A, B), but few coexpressed CD11b (Figure 2G) Most clusters of CD11b+ cells in nicotine- injected animals were around MZM, suggesting that these are neutrophils and monocytes which are known to migrate from the RP and the blood upon antigenic challenge (32) and not CD11c+ DCs which are present in the MZ and are critical for the activation of MZB 2, (33) (see Figure 2I). Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis of splenocytes at the 15 min time point demonstrated a slightly increased number of Gr1+/CD11b+ cells in the total splenocyte gate in nicotine-treated, compared with control animals, as reported previously (Supplementary Figure 3B) although the mean fluorescence intensity was not changed significantly. Histological analysis also demonstrated that the colocalization of CD11b and Gr1 seen on histology frequently in the MZ and rarely in the RP (Figure 2H arrows) was not due to co- expression of both markers, but rather to the two cell types present in close contact (see Supplementary Figure 3B).

We wished to determine if the response to live bacteria was subject to the same regulatory mechanisms that we observed in the response to heat killed bacteria. Mice that had been injected i.v. with a live virulent strain of Streptococcus pneumoniae (strain ATCC 6303) or with the same pneumococcal strain (R363) without inactivation also exhibited migratory arrest following nicotine administration. Gr1+ cells accumulated around most follicles in nicotine-treated mice, but rarely in saline-treated mice (Supplementary Figure 4). Thus, the response to heat-killed and live organisms was comparable.

Kinetics of the Migratory Arrest

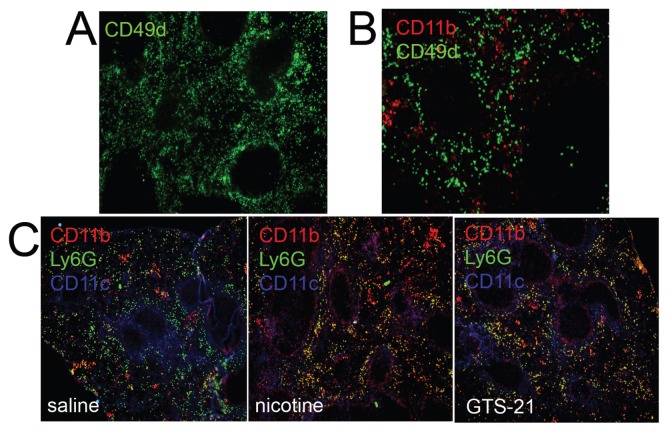

Histologic analysis suggested that the migratory arrest of B cells in the MZ, and the concomitant arrest of other leukocytes involved in their activation, might be responsible for lower numbers of activated antibody-secreting cells (ASCs) in the RP and the decreased antibody titers. We found that the lymphoid reorganization that occurs after streptococcal challenge was transient and started to disappear at approximately 4 h after nicotine and antigen injection (Figure 3A) and was absent at the time of peak antibody titers in the serum (Figures 3B, D) (6) in mice receiving a single dose of nicotine. In contrast, numerous CD11b+ cells remained accumulated in the MZ and perifollicular areas of mice receiving a daily dose of nicotine or GTS-21 even at 6 d after immunization (Figure 3C). Ly6G+ neutrophils, on the other hand, appeared similarly distributed in the RP in both control and stimulated mice at this time point (see Figure 3C).

Figure 3.

Kinetics of the migratory arrest. Spleen sections from nicotine-treated animals 4 h (A) or 6 d (B) after immunization and stained for CD49d and CD11b. (C) CD11b, Ly6G and CD49d distribution in spleen sections obtained at d 6 after immunization in saline, nicotine or GTS-21-treated animals as indicated. Images are representative of at least five animals per group from two independent experiments.

The MZ Migratory Arrest Is Controlled by the Cholinergic Antiinflammatory Pathway

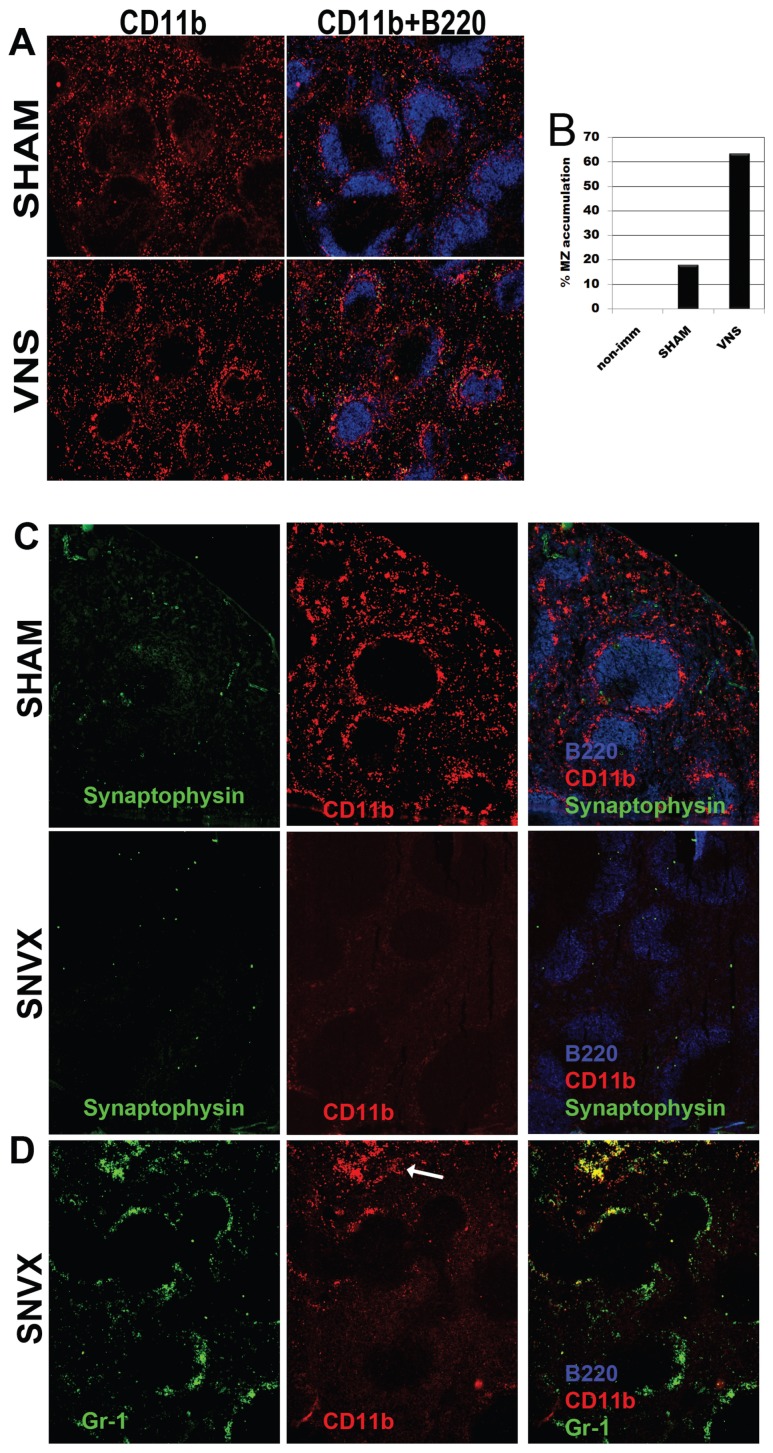

To demonstrate directly the neural mechanism for regulating migratory arrest, we next assessed cell trafficking following direct electrical stimulation of the vagus nerve, using methods that we have developed and described previously (30). We observed that vagus nerve stimulation arrested the transit of cells from the MZ significantly (Figures 4A–B). To track the anatomic basis of this neural circuit, we next performed selective surgical splenic neurectomy to denervate the spleen (30). Mice subjected to neurectomy or sham surgery were immunized 8 d later, and nicotine or saline was injected 1 d before and at the time of antigen exposure, as before. As expected CD11b+ cells accumulated in the MZ of sham-operated mice that received nicotine injections (Figure 4C SHAM). Significantly, these cells were absent from denervated regions as determined by the absence of staining for synaptophysin, a synaptic vesicle glycoprotein of neurons (Figure 4C SVNX). Further, CD11b+ cells were localized mainly in extrafollicular and subcapsular areas (Figure 4D SNVX, arrow). Together with the data that nicotine stimulates splenic nerve signals to suppress antibody titers, these results suggest that neutrally controlled expression of CD11b is a major mechanism for the retention of MZB cells and other leukocytes in the MZ. Splenic denervation downregulated CD11b expression significantly even in the absence of cholinergic stimulation (Figure 4D and Supplementary Figure 5) confirming previous reports of a tonic role for the splenic nerve in adhesion molecule expression (34) and demonstrating a connection between migration arrest and reduced antibody titers.

Figure 4.

The marginal zone cell arrest is neurally controlled. (A) The left branch of the vagus nerve was stimulated (VNS) 5 V, 2 ms, (5 Hz) for 2.5 min and mice were immunized immediately after. In sham mice the nerve was exposed but left untouched. Spleen sections obtained 15 min after immunization were stained with for CD11b and B220. (B) The number of follicles containing aggregated cells in VNS or sham-operated mice is shown. (C) Spleen sections from mice that underwent splenic neurectomy (SVNX) or from sham controls stained for CD11b, B220 and synaptophysin (top and center panels) or for CD11b, B220 and Gr-1 (lower panel) to show that CD11b+, but not Gr-1+ cells are absent from denervated areas. Images representative of 10 animals per group.

CD138+ Plasma Cells Are Associated with Nerve Fibers in the Spleen

Upon activation, MZB migrate toward the RP where they release antibodies to the blood. We therefore investigated the localization of nerve fibers to determine whether associations with ASCs (CD138+) could modulate their secretory capabilities as had been demonstrated previously (in vitro) as an additional mechanism to explain the effect of cholinergic stimulation on the antibody response. Mice were euthanized 2 to 6 d after immunization. As expected, we observed that nerve fibers in the subcapsular plexus followed the trabeculae around venous sinuses and in vascular plexuses associated with branches of the splenic artery. These follow the central arteries to the white pulp where nerve endings radiate from the perivascular nerve into the T-cell dense regions. Innervation of B-cell follicles is sparse, but nerve fibers are present along the parafollicular zones, mainly in splenic cords and, less frequently, in the marginal sinus and MZ. Few CD138+ cells were present in mice without bacterial challenge. As expected, after antigen challenge CD138+ cells were found primarily in the RP (Figures 5A, B), Interestingly, most CD138+ in extrafollicular areas were found to be associated with synaptophysin-positive structures localized along reticular fibers of the splenic cords and trabeculae, as well as in the immediate vicinity of venous sinuses of the RP which are also innervated (Figures 5C–D). Importantly, not all reticular fibers in the splenic cords were adjacent to CD138+ cells; rather, the association coincided with regions of innervation, as has been shown in other organs (35).

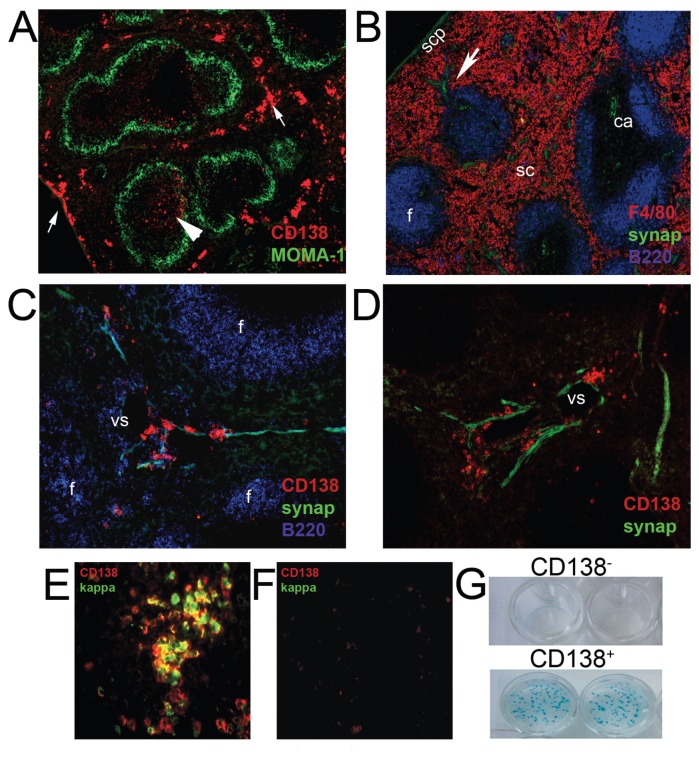

Figure 5.

CD138+ plasma cells are localized in close apposition with nerve fibers in the spleen. (A) Plasma cells were detected as syndecan-1+ (CD138) cells and the MZ, with an anti-MOMA-1 antibody in spleen sections 6 d after immunization. Most CD138+ cells were localized in parafollicular areas in the red pulp (arrows) or less frequently, inside the follicles (arrowhead). (B) Spleen sections stained for synaptophysin, F4/80 and B220. Central artery (ca), subcapsular plexus (scp), splenic cords (sc), follicle (f), trabeculae (arrowhead). (C–D) CD138+ cells were localized in close apposition with nerve fibers in perifollicular areas, follicle and surrounding venous sinuses in the red pulp. Images are representative of at least 10 animals. Spleen sections of immunized (E) or nonimmunized (F) animals at d 6 were stained for CD138 and kappa chain. Images are representative of multiple sections from at least four animals and three independent experiments. (G) CD138+ or CD138− and CD19+ cells were sorted from a B lymphocyte-enriched cell suspension obtained at d 6 after immunization. ELISpot assays were performed on PC-KLH-coated plates.

CD138+ Cells Are Antigen-Specific ASCs

We next determined that the CD138+ cells, which localized adjacent to the nerves were antigen-specific ASCs. CD138+ cells expressed immunoglobulin as determined by κ-light-chain staining (Figure 5E) and were seldom detectable in spleens of nonimmunized mice (Figure 5F). We performed ELISpot assays on B cells obtained at d 6 after immunization. CD138+ or CD138− cells sorted from a B-cell suspension were allowed to secrete antibody overnight on PC-KLH-coated plates. Only CD138+ cells were able to secrete anti-PC antibody (Figure 5G). Collectively, these results demonstrate that the CD138+ cells localized in close apposition to neurons are antigen-specific ASCs.

Nature and Localization of the Innervated Structures Associated with ASCs

CD138+ was expressed in the RP even at time points as short as 15 min after antigen challenge, in the same manner as CD1d (Figure 6A), suggesting that these cells derive from B1 and MZB cells which have a preactivated phenotype and are capable of becoming plasma cells in very short times.

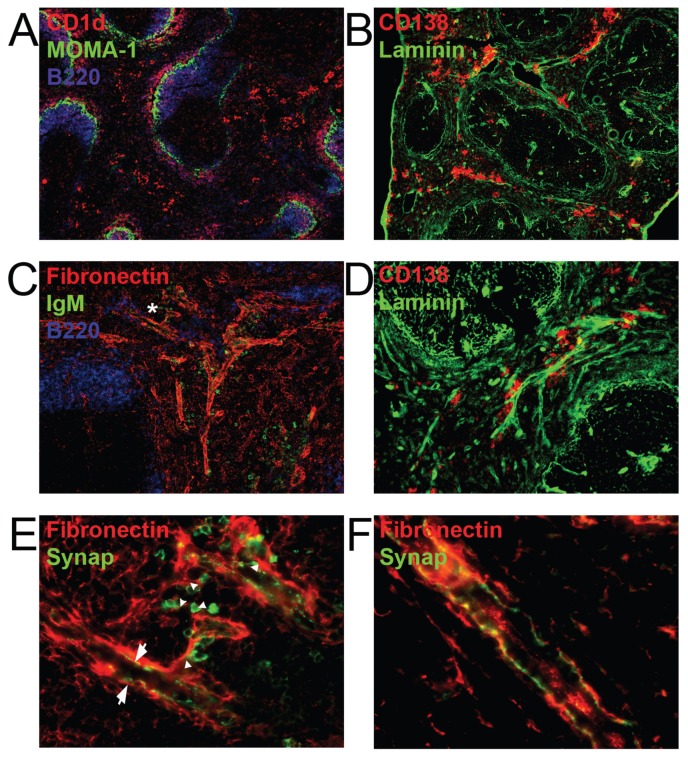

Figure 6.

Anatomical localization of innervated structures associated with ASCs. (A) Spleen sections from mice at 15 min after immunization were stained for MOMA-1, CD1d and B220. (B) Spleen sections from mice at 2 h after immunization were stained with a polyclonal anti-pan laminin antibody and CD138. (C) Spleen sections from mice euthanized 15 min after immunization stained for fibronectin, B220 and IgM. The asterisk indicates the area magnified in (E). (D) Higher magnification images (10X) reveal the clustering of CD138+ cells along laminin-containing structures detected as in b. (E) Staining was performed with a mouse monoclonal anti-synaptophysin antibody, which allowed the detection of both nerve fibers and antibody-expressing cells by utilizing a secondary FITC-conjugated anti-mouse IgM antibody (green). (F) Arrows denote IgM+ cells and arrowhead denote nerve fibers. Synaptophysin was detected with a polyclonal rabbit antibody. All images are representative of three independent experiments with at least 10 mice per group.

ASCs were localized either near venous sinuses or aligned along laminin and fibronectin-containing fibrous structures that run along the reticular network of the splenic cords and the trabeculae (Figures 6B–D). Fibrous structures that had IgM+ cells associated with them were innervated. The characteristic varicose configuration of nerves was found alongside the strands of fibronectin (Figures 6E–F). These structures were only occasionally associated with vascular elements (Supplementary Figure 6). This finding suggests that migrating lymphocytes, as well as those in contact with the vasculature for antibody secretion, are in close contact with splenic neurons that can exert a regulatory influence on the activation of MZB cells.

DISCUSSION

In the present work, we provide evidence that neural signals can diminish the antibody response to Streptococcus pneumoniae. This is mediated by signaling through the cholinergic antiinflammatory pathway, and can be replicated using specific α7nAChR agonists or direct electrical stimulation of neurons. Moreover, pharmacological antagonists, and chemical or surgical ablation of the pathway restore antibody titers to normal levels in animals exposed to nicotine. The effect is evident as soon as specific antibodies start to be detected in the blood of immunized animals suggesting an alteration in early steps of the response.

Significant alterations in the splenic architecture were observed early after antigen challenge. We observed a marked accumulation of B cells, neutrophils, monocytes and DC in the MZ of spleens from stimulated compared with control mice. This accumulation is in part explained by the increased influx of cells into the spleen upon cholinergic stimulation as reported recently (34). However, resident and newly arrived cells were found to remain in the MZ of stimulated mice at time points at which the majority of cells were already in the RP and perifollicular areas in control animals. The phenomenon was demonstrated to be under neural control because electrical stimulation of the vagus nerve induced migratory arrest, which was abrogated by surgical ablation of the splenic nerve. The arrested cells express the adhesion molecule CD11b and cluster around CD49d+ cells. Surgical ablation of the splenic nerve profoundly alters the distribution of CD11b+ cells in the spleen, resulting in their accumulation in the RP even in saline-injected animals demonstrating that the homeostatic regulation in the spleen is under neural control as reported previously (34). Importantly, the arrest of MZ cells occurs in response to both killed bacteria and to live bacteria. This immobilization of ASCs accounts at least in part for the decreased antibody response, though we cannot assess the antibody response in mice given live bacteria, as the bacterial challenge is lethal.

ASCs that have migrated successfully to the RP often are associated with reticular fibers in the RP that are known to guide their migration toward vessels where they secrete antibodies (9). We found that these conduits are innervated frequently which permits direct exposure of migrating cells to neurotransmitters. This observation demonstrates a second potential mechanism for the regulation of antibody secretion by the nervous system. A physical association between ASCs and nerve fibers has been shown in the intestine where neurotransmitters have been proposed to regulate antibody secretion of ASCs that migrate toward nerve fibers upon activation (35). Our observations in the spleen are in line with those findings suggesting that nerve signals participate in the regulation of the humoral immune response in several organs by similar mechanisms. The nature of the neurotransmitter released upon vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) in the spleen was not determined directly, but norepinephrine is the predominant neurotransmitter released by splenic nerves (36) and this neurotransmitter is capable of altering B-cell function in vitro (24,25,37,38).

A recent report demonstrates, in striking similarity to our findings, that immune cells cluster around nerves in developing lymph nodes and that vagus nerve stimulation induces the expression of chemokines via retinoic acid (RA) (39). RA is a potent inducer of adhesion molecule expression and a regulator of leukocyte trafficking by this mechanism (40,41). Our preliminary results suggest that RALDH, the enzyme responsible for the metabolism of vitamin A to RA is expressed in the cells that accumulate in the MZ cells of cholinergically stimulated animals along with adhesion molecules known to be required for their retention in the MZ (6). Inhibition of this pathway with disulfiram reduces the number of cellular aggregates surrounding the follicles of nicotine-injected immunized animals suggesting a contribution of the RA pathway to the alteration in leukocyte trafficking observed in these animals, and the modulation of RA synthesis by neural input (unpublished data).

Of clinical significance, a 20% to 30% decrease in the antibody titers to pneumococcal immunization, similar to the decrease we observed in nicotine-treated animals has been described in human smokers (17,42,43). Among immunocompetent adults, the strongest independent risk factor for invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) is cigarette smoking (16) and the Center for Disease Control (CDC) has recommended the pneumococcal vaccine for smokers (44). Due to the importance of anti-PC antibodies in the protection from pneumococcal infections, our data support a model in which decreased antibody responses due to nicotine stimulation are at least in part responsible for the increased susceptibility of smokers to IPD, and direct damage to the airway by cigarette smoke may be less important than previously thought.

While a single electrical stimulation of the vagus nerve in mice caused migratory arrest, it was not sufficient to alter the antibody titers measured 3 or 6 d after stimulation (not shown). Thus, altered humoral responses require repeated stimulation of the vagus nerve. In humans, however, the effect of tobacco smoke exposure on serum concentration of antibodies, although temporary, persists for several months after cessation of smoking. It is plausible to consider that, for chronic smokers, ongoing exposure to nicotine persistently inhibits cell migration leading to decreased antibody responses.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, neural signaling regulates the development of humoral immunity by modulating cell trafficking and lymphoid architecture reorganization. It has been shown previously that neural signals control egress of immune cells from the bone marrow (45). These data extend the paradigm to show that cell migration within secondary lymphoid organs is also controlled by neural signals. Most significantly, antibody secretion is therefore a neurally controlled event. There are important implications to these data, as it may be possible to modify antibody output to therapeutic advantage by targeting these mechanisms.

Supplemental Data

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by funding from the NIH (B Diamond and KJ Tracey). P Mina-Osorio was supported by a fellowship from the Arthritis Foundation. We thank Stella Stefanova for assistance with the B-cell sorting experiments and Eva Bertini for assistance with pneumococcal growth and inactivation.

Footnotes

Online address: http://www.molmed.org

DISCLOSURE

The authors declare they have no competing interests as defined by Molecular Medicine, or other interests that might be perceived to influence the results and discussion reported in this paper.

REFERENCES

- 1.Briles DE, et al. Antiphosphocholine antibodies found in normal mouse serum are protective against intravenous infection with type 3 streptococcus pneumoniae. J Exp Med. 1981;153:694–705. doi: 10.1084/jem.153.3.694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balazs M, Martin F, Zhou T, Kearney J. Blood dendritic cells interact with splenic marginal zone B cells to initiate T-independent immune responses. Immunity. 2002;17:341–52. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00389-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Humphrey JH. Splenic macrophages: antigen presenting cells for T1–2 antigens. Immunol Lett. 1985;11:149–52. doi: 10.1016/0165-2478(85)90161-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martin F, Oliver AM, Kearney JF. Marginal zone and B1 B cells unite in the early response against T-independent blood-borne particulate antigens. Immunity. 2001;14:617–29. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00129-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karlsson MC, et al. Macrophages control the retention and trafficking of B lymphocytes in the splenic marginal zone. J Exp Med. 2003;198:333–40. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lu TT, Cyster JG. Integrin-mediated long-term B cell retention in the splenic marginal zone. Science. 2002;297:409–12. doi: 10.1126/science.1071632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gaschler GJ, et al. Bacteria challenge in smoke-exposed mice exacerbates inflammation and skews the inflammatory profile. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;179:666–75. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200808-1306OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oliver AM, Martin F, Kearney JF. IgMhighCD21high lymphocytes enriched in the splenic marginal zone generate effector cells more rapidly than the bulk of follicular B cells. J Immunol. 1999;162:7198–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saito H, et al. Reticular meshwork of the spleen in rats studied by electron microscopy. Am J Anat. 1988;181:235–52. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001810303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martin F, Kearney JF. B-cell subsets and the mature preimmune repertoire. Marginal zone and B1 B cells as part of a “natural immune memory”. Immunol. Rev. 2000;175:70–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Horton J, Ogden ME, Williams S, Coln D. The importance of splenic blood flow in clearing pneumococcal organisms. Ann Surg. 1982;195:172–6. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198202000-00009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen Y, et al. Defective microarchitecture of the spleen marginal zone and impaired response to a thymus-independent type 2 antigen in mice lacking scavenger receptors MARCO and SR-A. J Immunol. 2005;175:8173–80. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.12.8173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cyster JG. Homing of antibody secreting cells. Immunol Rev. 2003;194:48–60. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2003.00041.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guinamard R, Okigaki M, Schlessinger J, Ravetch JV. Absence of marginal zone B cells in Pyk-2-deficient mice defines their role in the humoral response. Nat Immunol. 2000;1:31–6. doi: 10.1038/76882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nie Y, et al. The role of CXCR4 in maintaining peripheral B cell compartments and humoral immunity. J Exp Med. 2004;200:1145–56. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nuorti JP, et al. Cigarette smoking and invasive pneumococcal disease. Active Bacterial Core Surveillance Team. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:681–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200003093421002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holt PG. Immune and inflammatory function in cigarette smokers. Thorax. 1987;42:241–9. doi: 10.1136/thx.42.4.241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Riise GC, Larsson S, Andersson BA. Bacterial adhesion to oropharyngeal and bronchial epithelial cells in smokers with chronic bronchitis and in healthy nonsmokers. Eur Respir J. 1994;7:1759–64. doi: 10.1183/09031936.94.07101759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thorley AJ, Tetley TD. Pulmonary epithelium, cigarette smoke, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2007;2:409–28. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stampfli MR, Anderson GP. How cigarette smoke skews immune responses to promote infection, lung disease and cancer. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:377–84. doi: 10.1038/nri2530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tracey KJ. The inflammatory reflex. Nature. 2002;420:853–9. doi: 10.1038/nature01321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pavlov VA, et al. Selective alpha7-nicotinic acetylcholine receptor agonist GTS-21 improves survival in murine endotoxemia and severe sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:1139–44. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000259381.56526.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang H, et al. Cholinergic agonists inhibit HMGB1 release and improve survival in experimental sepsis. Nat Med. 2004;10:1216–21. doi: 10.1038/nm1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kohm AP, Sanders VM. Norepinephrine and beta 2-adrenergic receptor stimulation regulate CD4+ T and B lymphocyte function in vitro and in vivo. Pharmacol Rev. 2001;53:487–525. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Skok M, Grailhe R, Changeux JP. Nicotinic receptors regulate B lymphocyte activation and immune response. Eur J Pharmacol. 2005;517:246–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kem WR, et al. Hydroxy metabolites of the Alzheimer’s drug candidate 3-[(2,4-dimethoxy) benzylidene]-anabaseine dihydrochloride (GTS-21): their molecular properties, interactions with brain nicotinic receptors, and brain penetration. Mol Pharmacol. 2004;65:56–67. doi: 10.1124/mol.65.1.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McDaniel LS, Scott G, Kearney JF, Briles DE. Monoclonal antibodies against protease-sensitive pneumococcal antigens can protect mice from fatal infection with Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Exp Med. 1984;160:386–97. doi: 10.1084/jem.160.2.386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Paterson GK, Blue CE, Mitchell TJ. Role of interleukin-18 in experimental infections with Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Med Microbiol. 2005;54:323–6. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.45873-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.De la Torre JC. An improved approach to histofluorescence using the SPG method for tissue monoamines. J. Neurosci. Methods. 1980;3:1–5. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(80)90029-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rosas-Ballina M, et al. Splenic nerve is required for cholinergic antiinflammatory pathway control of TNF in endotoxemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:11008–13. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803237105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Livnat S, Felten SY, Carlson SL, Bellinger DL, Felten DL. Involvement of peripheral and central catecholamine systems in neural-immune interactions. J Neuroimmunol. 1985;10:5–30. doi: 10.1016/0165-5728(85)90031-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kesteman N, Vansanten G, Pajak B, Goyert SM, Moser M. Injection of lipopolysaccharide induces the migration of splenic neutrophils to the T cell area of the white pulp: role of CD14 and CXC chemokines. J Leukoc Biol. 2008;83:640–7. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0807578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Swirski FK, et al. Identification of splenic reservoir monocytes and their deployment to inflammatory sites. Science. 2009;325:612–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1175202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huston JM, et al. Cholinergic neural signals to the spleen down-regulate leukocyte trafficking via CD11b. J Immunol. 2009;183:552–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0802684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hisajima T, Kojima Y, Yamaguchi A, Goris RC, Funakoshi K. Morphological analysis of the relation between immunoglobulin A production in the small intestine and the enteric nervous system. Neurosci Lett. 2005;381:242–6. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.02.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rosas-Ballina M, Tracey KJ. Cholinergic control of inflammation. J Intern Med. 2009;265:663–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2009.02098.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kin NW, Sanders VM. It takes nerve to tell T and B cells what to do. J Leukoc Biol. 2006;79:1093–104. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1105625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Franco R, Pacheco R, Lluis C, Ahern GP, O’Connell PJ. The emergence of neurotransmitters as immune modulators. Trends Immunol. 2007;28:400–7. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2007.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van de Pavert SA, et al. Chemokine CXCL13 is essential for lymph node initiation and is induced by retinoic acid and neuronal stimulation. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:1193–9. doi: 10.1038/ni.1789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mora JR, Iwata M, von Andrian UH. Vitamin effects on the immune system: vitamins A and D take centre stage. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:685–98. doi: 10.1038/nri2378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mebius RE. Vitamins in control of lymphocyte migration. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:229–30. doi: 10.1038/ni0307-229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Andersen P, Pedersen OF, Bach B, Bonde GJ. Serum antibodies and immunoglobulins in smokers and nonsmokers. Clin Exp Immunol. 1982;47:467–473. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gulsvik A, Fagerhoi MK. Smoking and immunoglobulin levels. Lancet. 1979;1:449. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(79)90934-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Poland GA, Schaffner W. Immunization guidelines for adult patients: an annual update and a challenge. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:53–4. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-1-200901060-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Katayama Y, et al. Signals from the sympathetic nervous system regulate hematopoietic stem cell egress from bone marrow. Cell. 2006;124:407–21. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.10.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.