Abstract

Increasing chronological age is the most significant risk factor for human cancer development. To examine the effects of host aging on mammary tumor growth, we used caveolin (Cav)-1 knockout mice as a bona fide model of accelerated host aging. Mammary tumor cells were orthotopically implanted into these distinct microenvironments (Cav-1+/+ versus Cav-1−/− age-matched young female mice). Mammary tumors grown in a Cav-1–deficient tumor microenvironment have an increased stromal content, with vimentin-positive myofibroblasts (a marker associated with oxidative stress) that are also positive for S6-kinase activation (a marker associated with aging). Mammary tumors grown in a Cav-1–deficient tumor microenvironment were more than fivefold larger than tumors grown in a wild-type microenvironment. Thus, a Cav-1–deficient tumor microenvironment provides a fertile soil for breast cancer tumor growth. Interestingly, the mammary tumor-promoting effects of a Cav-1–deficient microenvironment were estrogen and progesterone independent. In this context, chemoprevention was achieved by using the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitor and anti-aging drug, rapamycin. Systemic rapamycin treatment of mammary tumors grown in a Cav-1–deficient microenvironment significantly inhibited their tumor growth, decreased their stromal content, and reduced the levels of both vimentin and phospho-S6 in Cav-1–deficient cancer-associated fibroblasts. Since stromal loss of Cav-1 is a marker of a lethal tumor microenvironment in breast tumors, these high-risk patients might benefit from treatment with mTOR inhibitors, such as rapamycin or other rapamycin-related compounds (rapalogues).

Caveolin (Cav)-1 knockout (KO) mice represent an established animal model of accelerated aging.1,2 Cav-1 KO mice have a significantly reduced life span,1 and exhibit many signs of premature aging, such as increased neurodegeneration, astrogliosis, reduced synapses, and increased β-amyloid production.2 Cav-1 KO mice also exhibit other age-related pathological conditions, such as benign prostatic hypertrophy,3 glucose intolerance, insulin resistance, and other key features of metabolic syndrome, but remain lean and are resistant to diet-induced obesity.4–7 These phenotypic changes in Cav-1 KO mice have been mechanistically attributed to systemic metabolic defects.8 For example, Cav-1 KO mice show evidence of increased oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction.8,9 In fact, knockdown of Cav-1 in fibroblasts, using a small-interfering RNA approach, is sufficient to induce reactive oxygen species production and DNA damage and to drastically reduce mitochondrial membrane potential.9–11 Thus, we and others have concluded that Cav-1 KO mice are a new model for mitochondrial oxidative stress and accelerated host aging.1,2,8,9,12 Because Cav-1 is a critical regulator of nitric oxide production (via its interactions with nitric oxide synthase) and cholesterol transport, increased nitric oxide production and/or abnormal cholesterol transport have been implicated in generating mitochondrial oxidative stress in Cav-1–deficient fibroblasts.9–13

Recently, it has been proposed that oxidative stress in the tumor microenvironment may lead to accelerated host aging, with accompanying DNA damage, inflammation, and a shift toward aerobic glycolysis (due to the autophagic destruction of mitochondria).14,15 As a consequence, oxidative stress and autophagy in the tumor microenvironment produce high-energy nutrients (eg, L-lactate and ketones) that can fuel tumor growth via oxidative mitochondrial metabolism in cancer cells.8,16–22

Herein, we have used Cav-1 KO mice as a new breast cancer stromal model to assess the potential effects of oxidative stress and accelerated host aging on mammary tumor growth in vivo. Tumors grown in Cav-1–deficient mammary fat pads were significantly larger (more than fivefold) and showed increased stromal content, as predicted.

Oxidative stress is sufficient to drive myofibroblast differentiation23,24 and is known to accelerate aging.25 In accordance with these findings, we show that Cav-1–deficient cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) have increased levels of vimentin (a myofibroblast marker) and phospho-S6 (a marker of increased aging). In fact, deletion of S6-kinase is sufficient to dramatically increase life span in mice, indicating that S6-kinase activation is also a functional marker of accelerated aging.26

Mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR)/S6-kinase signaling has been directly implicated in the process of aging.27–30 In this context, rapamycin has been proposed to function as an anti-aging drug by experimentally extending life span in both normal mice and tumor-bearing mice.27,31,32 Thus, we next examined whether systemically shutting down mTOR/S6-kinase signaling was sufficient to prevent the formation of mammary tumors in a Cav-1–deficient microenvironment.

Remarkably, rapamycin treatment significantly inhibited the growth of mammary tumors in a Cav-1–deficient tumor microenvironment. Rapamycin effectively reduced the stromal content of these tumors; the levels of vimentin and phospho-S6 were also significantly decreased in Cav-1–deficient CAFs. Thus, we should consider using rapamycin (or its close relatives, the rapalogues) for the chemoprevention of recurrence in breast cancer patients who show an absence of stromal Cav-1. In direct support of this notion of chemoprevention, rapamycin and its analogues have significantly reduced the risk of developing multiple malignancies in transplant patients.33,34

Importantly, a loss of stromal Cav-1 is a powerful predictive biomarker that is associated with early tumor recurrence, lymph node metastasis, and tamoxifen resistance, driving poor clinical outcome in breast cancer patients.35–39 Similarly, a loss of stromal Cav-1 in patients with ductal carcinoma in situ is predictive of recurrence and progression to invasive breast cancer, up to 20 years in advance.40 Similar results were also obtained with triple-negative breast cancer patients.41 In TN patients, a loss of stromal Cav-1 was associated with a 5-year survival rate of <10%. In the same patient cohort, TN patients with high stromal Cav-1 had a survival rate of >75% at up to 12 years after diagnosis.41 Finally, in prostate cancer patients, a loss of stromal Cav-1 is associated with advanced prostate cancer and metastatic disease, as well as a high Gleason score, which is the current gold standard for predicting prostate cancer prognosis.42 As such, Cav-1–deficient mice are a valid model for a lethal tumor microenvironment.8

Consistent with these assertions, a loss of stromal Cav-1 is a surrogate functional marker for aging, oxidative stress, DNA damage, hypoxia, autophagy, and inflammation in the tumor microenvironment.10,11,13,21,43–46 In fact, genome-wide transcriptional profiling of laser-captured tumor stroma isolated from Cav-1–negative breast cancer patients showed the presence of multiple gene signatures associated with aging, DNA damage, inflammation, and even Alzheimer's disease brain.46 Virtually identical results were also obtained via the transcriptional profiling of bone marrow–derived stromal cells generated from young Cav-1 KO mice, further validating a strict association with accelerated aging.8,13,16,47 Thus, our current findings have important translational implications, specifically for the diagnosis and the therapeutic stratification of breast cancer patients (ie, personalized cancer medicine and/or theragnostics).

Materials and Methods

Animals

This study was conducted according to the guidelines of the NIH and the Thomas Jefferson University Institute for Animal Studies. The approval was granted by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Thomas Jefferson University. Cav-1 KO mice were generated, as previously described.48 All mice used in this study were in the FVB/N genetic background.

Materials

Mammary tumor (Met-1) cells were the generous gift of Dr. Robert D. Cardiff (University of California–Davis). Met-1 cells are a well-characterized TN mammary tumor cell line (Robert D. Cardiff, personal communication).49 Rabbit polyclonal antibodies against vimentin (R28) and phospho-S6 ribosomal protein (Ser235/236; 91B2) were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA). A mouse monoclonal antibody against minichromosal maintenance 7 (141.2) and a rabbit polyclonal antibody against Cav-1 (N-20) were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). A mouse monoclonal antibody to glyceradehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase was obtained from Fitzgerald Industries International (Acton, MA) and was used as loading control. A rabbit polyclonal antibody against CD31 (28364) was obtained from Abcam (Cambridge, MA). A mouse monoclonal antibody against nucleophosmin/B23 (Fc-61991) was obtained from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). The immunohistochemistry (IHC) visualization kit LSAB2 was obtained from Dako (Carpentaria, CA). Nuclear counterstains, such as Hoechst 33342 and hematoxylin, were obtained from Invitrogen and Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO). Horseradish peroxidase–conjugated secondary antibodies [anti-mouse (1:20,000 dilution) (Pierce Chemical, Rockford, IL) or anti-rabbit (1:20,000 dilution) (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA)] were used to visualize bound primary antibodies with the supersignal chemiluminescence substrate (Pierce Chemical). Fluorescein isothiocyanate– and tetrarhodamine isothiocyanate–conjugated secondary antibodies were obtained from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories (West Grove, PA). Placebo and rapamycin pellets (2.5 mg, 60 days, slow release) were obtained from Innovative Research of America (Sarasota, FL).

Orthotopic Injection of Met-1 Cells

Met-1 cells are a tumorigenic cell line established from a mammary adenocarcinoma derived from a female MMTV-PyMT mouse, and are, thus, syngeneic to the FVB/N strain. Met-1 cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 2 mmol/L glutamine, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin. For the injections, 6- to 8-week-old female FVB/N wild-type (WT; Cav-1+/+) and Cav-1 KO (Cav-1−/−) mice (n = 11 to 13 per group) were anesthetized with xylazine:ketamine (5 mg/kg:50 mg/kg), and a ventral incision was performed to expose the right fourth (inguinal) mammary gland. Met-1 cells (0.5 million in 50 μL of complete growth media) were then injected into the right mammary fat pad (inguinal 4) using a 26-gauge needle. The incision was subsequently closed with a 5-0 silk suture. Tumor growth was monitored during a 5-week period, and tumor size was determined by weight. To calculate tumor incidence, mice were divided into groups with tumors that weighed <0.35 g (small), 0.35 to 0.8 g (medium), and >0.8 g (large).

Rapamycin Pellet Implantation

Implantation of slow-release pellets was performed under anesthesia after the mammary fat pad injections. The site of incision was shaved and scrubbed. The skin was lifted on the lateral side of the neck of the animal, and an incision equal in diameter to that of the pellet was performed. Then, a horizontal pocket of approximately 2 cm beyond the incision site was generated to introduce the pellet with forceps. The mice were randomly assigned to groups receiving two placebo pellets or two rapamycin pellets (2.5 mg, 60 days, slow release).

Bilateral Ovariectomy Procedure

Mice underwent ovariectomy, as previously described.50 Briefly, 3- to 4-week-old female FVB/N WT and Cav-1 KO mice were anesthetized using xylazine:ketamine (5 mg/kg:50 mg/kg). A single dorsal incision, followed by ligation of the ovarian arteries and veins with a 4-0 silk suture, was performed, followed by the excision of both ovaries. The incision site was subsequently closed with a 5-0 silk suture.

Preparation and Analysis of Tissues

After the mice were sacrificed, inguinal mammary gland 4 was excised and fixed in formalin for 24 hours, paraffin embedded, and cut into sections (5 μm thick) for histological analyses and IHC staining. For blood vessel quantitation, five fields of CD31 staining per tumor were taken with a ×40 objective and the CD31-positive vessels were counted and averaged. The tumors from four to six mice were immunostained with CD31 antibody per group.

Western Blot Analysis

Western blot analysis was performed as previously described.51 Briefly, mice were euthanized and the mammary fat pad was dissected, weighed, and snap frozen in liquid nitrogen. Samples were homogenized in radioimmunoprecipitation (RIPA) assay [50 mmol/L Tris (pH 7.5), 150 mmol/L NaCl, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.5% deoxycholate, and 0.1% SDS]52 lysis buffer with complete miniprotease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN) and phosphatase inhibitor cocktails from Sigma-Aldrich. After homogenization, samples were sonicated and centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 10 minutes. Samples were separated by SDS-PAGE (12% acrylamide) and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane for probing. Subsequent wash buffers consisted of 10 mmol/L Tris (pH 8.0), 150 mmol/L NaCl, and 0.05% Tween 20. Membranes were blocked in 10 mmol/L Tris (pH 8.0), 150 mmol/L NaCl, and 0.05% Tween 20 supplemented with 5% bovine serum albumin (Sigma-Aldrich) or 5% nonfat dry milk (Carnation, Solon, OH) for 1 hour at room temperature. The membranes were subsequently incubated with a given primary antibody for 3 hours at room temperature. Primary antibodies were used at a range of 1 to 2.5 μg/mL dilution. Horseradish peroxidase–conjugated secondary antibodies were used to visualize bound primary antibodies with the supersignal chemiluminescence substrate (Pierce Chemical).

IHC Analysis of Tissues

IHC was performed as previously described.50 Briefly, paraffin-embedded sections (5 µm thick) of fat pads (containing tumor cells) were dehydrated in xylene for 10 minutes and rehydrated in a series of graded ethanols and distilled water for 5 minutes. The slides were then incubated in a citric acid–based antigen unmasking solution with an acidic pH (Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA) using an electric pressure cooker on high pressure for 5 to 10 minutes. The slides (six to eight per group) were incubated in 3% hydrogen peroxide (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Hampton, NH) for 30 minutes at room temperature and blocked with 10% goat normal serum (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) for 1 hour at room temperature and incubated with a given primary antibody overnight at 4°C. The following day, slides were washed with PBS once and incubated with a biotinylated mouse or rabbit secondary antibody included in the IHC visualization kit (LSAB2). The remainder of the protocol was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions. The slides were counterstained using Mayer's hematoxylin. The slides were dehydrated with graded alcohols and left in xylene for 15 minutes before mounting with Permount (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The images were acquired at ×40 and ×60 magnification.

Immunofluorescence

For immunofluorescence, the same protocol as IHC was used, with the exception of the peroxidase blocking step, and the secondary antibodies used were fluorescein isothiocyanate and tetrarhodamine isothiocyanate conjugated (1:300). The slides were counterstained with Hoechst 33342 (1:1000) and mounted with Prolong Gold antifade solution (Invitrogen). The tumors were imaged with a confocal microscope (Zeiss LSM 510; Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, NY). Images were acquired with ×63 and ×100 objectives.

Statistical Analysis

All of the statistical analysis was performed using a one-way analysis of variance, followed by a Tukey-Kramer multiple comparison test, unless otherwise stated. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Mining of Transcriptional Profiling Data

The transcriptional profiles of laser-captured tumor stroma,46,53 isolated from human breast cancer patients, were re-examined for evidence of elevated mTOR/S6-kinase signaling, essentially as we previously described for other signaling pathways related to glycolysis, lysosomal degradation, and autophagy.8,47 More specifically, the data presented in Table 1 were from published DNA microarray data from Pavlides et al47 using fresh-frozen invasive breast cancer samples with their matching benign control subjected to laser microdissection to specifically isolate the stromal compartment. The data presented in Table 2 were obtained from published DNA microarray data from Witkiewicz et al46 using fresh-frozen breast cancer samples subjected to laser capture microdissection to specifically isolate the stromal RNA from Cav-1–positive (n = 4) and Cav-1–negative (n = 7) breast cancer stromal compartments.

Table 1.

Transcriptional Overexpression of S6-Kinase and Ribosomal Proteins in Tumor Stroma Isolated from Breast Cancer Patients

| Symbol | Gene description | Tumor stroma | Recurrence stroma | Metastasis stroma |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ribosomal protein S6 kinase | ||||

| Rps6kl1 | Ribosomal protein S6 kinase-like 1 | 2.59 × 10−16 | 9.39 × 10−4 | |

| Rps6kb1 | Ribosomal protein S6 kinase, polypeptide 1 | 6.12 × 10−13 | 9.76 × 10−4 | |

| Rps6ka2 | Ribosomal protein S6 kinase, polypeptide 2 | 8.69 × 10−11 | 5.82 × 10−3 | |

| Rps6kb2 | Ribosomal protein S6 kinase, polypeptide 2 | 1.10 × 10−10 | 1.37 × 10−3 | |

| Rps6ka1 | Ribosomal protein S6 kinase, polypeptide 1 | 1.43 × 10−10 | 3.12 × 10−4 | |

| Rps6ka6 | Ribosomal protein S6 kinase, polypeptide 6 | 2.60 × 10−9 | 4.52 × 10−2 | |

| Rps6ka5 | Ribosomal protein S6 kinase, polypeptide 5 | 9.60 × 10−4 | ||

| Rps6ka4 | Ribosomal protein S6 kinase, polypeptide 4 | 1.55 × 10−2 | ||

| Rps6ka3 | Ribosomal protein S6 kinase, polypeptide 3 | 3.01 × 10−2 | ||

| Ribosomal proteins | ||||

| Rpl3l | Ribosomal protein L3-like | 1.37 × 10−19 | ||

| Rps9 | Ribosomal protein S9 | 5.64 × 10−15 | 2.27 × 10−3 | |

| Rpl22 | Ribosomal protein L22 | 4.39 × 10−12 | ||

| Rpl23 | Ribosomal protein L23 | 5.40 × 10−6 | ||

| Rpl30 | Ribosomal protein L30 | 7.77 × 10−4 | ||

| Rps27l | Ribosomal protein S27-like | 3.89 × 10−2 | ||

| Rpl21 | Ribosomal protein L21 | 3.16 × 10−4 | ||

| Rps7 | Ribosomal protein S7 | 2.86 × 10−3 | ||

| Rsl1d1 | Ribosomal L1 domain-containing 1 | 1.74 × 10−2 | ||

| Rps14 | Ribosomal protein S14 | 2.45 × 10−2 | ||

| Rpl7l1 | Ribosomal protein L7-like 1 | 3.85 × 10−2 | ||

| Rps24 | Ribosomal protein S24 | 4.72 × 10−2 | ||

| Mitochondrial ribosomal proteins | ||||

| Mrp63 | Mitochondrial ribosomal protein 63 | 1.27 × 10−20 | ||

| Mrps10 | Mitochondrial ribosomal protein S10 | 9.11 × 10−20 | ||

| Mrpl20 | Mitochondrial ribosomal protein L20 | 1.25 × 10−17 | ||

| Mrpl43 | Mitochondrial ribosomal protein L43 | 1.71 × 10−17 | 1.16 × 10−2 | |

| Mrps18b | Mitochondrial ribosomal protein S18B | 4.86 × 10−17 | 1.83 × 10−3 | |

| Mrps6 | Mitochondrial ribosomal protein S6 | 9.10 × 10−14 | ||

| Mrps12 | Mitochondrial ribosomal protein S12 | 2.31 × 10−11 | 2.55 × 10−2 | |

| Mrpl38 | Mitochondrial ribosomal protein L38 | 2.36 × 10−9 | 4.20 × 10−2 | |

| Mrpl2 | Mitochondrial ribosomal protein L2 | 2.13 × 10−7 | 1.98 × 10−2 | |

| Mrps25 | Mitochondrial ribosomal protein S25 | 8.25 × 10−6 | 2.75 × 10−2 | |

| Mrps24 | Mitochondrial ribosomal protein S24 | 3.06 × 10−5 | ||

| Mrps34 | Mitochondrial ribosomal protein S34 | 3.72 × 10−2 | 3.85 × 10−2 | |

| Mrpl9 | Mitochondrial ribosomal protein L9 | 1.62 × 10−4 | 2.03 × 10−3 | |

| Mrpl55 | Mitochondrial ribosomal protein L55 | 1.61 × 10−3 | 1.43 × 10−2 | |

| Mrpl49 | Mitochondrial ribosomal protein L49 | 3.97 × 10−2 | ||

| Mrpl52 | Mitochondrial ribosomal protein L52 | 4.08 × 10−2 | ||

| Mrpl3 | Mitochondrial ribosomal protein L3 | 2.43 × 10−2 | ||

| Mrpl33 | Mitochondrial ribosomal protein L33 | 2.50 × 10−2 | ||

| Mrpl4 | Mitochondrial ribosomal protein L4 | 2.85 × 10−2 | ||

| Mrps17 | Mitochondrial ribosomal protein S17 | 3.87 × 10−2 | ||

| Mrpl12 | Mitochondrial ribosomal protein L12 | 3.95 × 10−2 | ||

| Mrps5 | Mitochondrial ribosomal protein S5 | 4.14 × 10−2 | ||

| Upstream activators of S6 kinase | ||||

| Pik3cd | PI3K catalytic δ polypeptide | 3.43 × 10−26 | 6.57 × 10−3 | |

| Pik3cg | PI3K catalytic γ polypeptide | 5.82 × 10−22 | 4.10 × 10−2 | |

| Pik3ap1 | PI3K adaptor protein 1 | 7.87 × 10−15 | 8.30 × 10−3 | |

| Pdpk1 | PI3–dependent protein kinase-1 | 8.76 × 10−14 | 8.65 × 10−4 | |

| Pik3c3 | PI3K, class 3 | 3.74 × 10−13 | ||

| Pik3c2g | PI3K, C2 domain, γ | 1.31 × 10−5 | ||

| Igf1 | Insulin-like growth factor 1 | 9.71 × 10−18 | ||

| Rragc | Ras-related GTP binding C | 2.61 × 10−18 | ||

| Rraga | Ras-related GTP binding A | 2.92 × 10−17 | ||

| Akt3 | V-akt thymoma viral oncogene homolog 3 | 2.18 × 10−13 | ||

| Rheb | RAS-homolog enriched in brain | 2.76 × 10−12 | ||

| Other mTOR downstream effectors/regulators | ||||

| Prkaa2 | Kinase, AMP-activated α2 catalytic | 9.03 × 10−25 | 1.50 × 10−4 | |

| Prkag3 | Kinase, AMP-activated γ3 noncatalytic | 3.55 × 10−12 | ||

| Prkab2 | Kinase, AMP-activated β2 noncatalytic | 1.99 × 10−8 | ||

| Prkaa1 | Kinase, AMP-activated α1 catalytic | 4.67 × 10−8 | 2.50 × 10−2 | |

| Prkag2 | Kinase, AMP-activated γ2 noncatalytic | 5.02 × 10−8 | 1.10 × 10−2 | 2.19 × 10−2 |

| Cdc42 | Cell division cycle 42 homolog | 2.46 × 10−22 | 1.36 × 10−3 | |

| Eif4ebp2 | Eif4e-binding protein 2 | 3.59 × 10−17 | ||

| Eif4ebp1 | Eif4e-binding protein 1 | 1.41 × 10−5 | ||

| Eif4e | Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E | 1.16 × 10−10 | 2.10 × 10−2 | |

| Vegfb | Vascular endothelial growth factor B | 5.13 × 10−12 | ||

| Ddit4l | DNA damage–inducible transcript 4-like | 4.76 × 10−11 | ||

| Ulk2 | Unc-51 like kinase 2 (Caenorhabditis elegans) | 6.16 × 10−11 | ||

| Ppp2r2b | Protein phosphatase2 regulatory subunit B | 1.24 × 10−8 | ||

| Ppp2r1a | Protein phosphatase2 regulatory subunit A | 4.06 × 10−3 | ||

| Ppp2r2c | Protein phosphatase2 regulatory subunit B | 2.76 × 10−3 | ||

| Ppp2r2a | Protein phosphatase2 regulatory subunit B | 3.94 × 10−2 | ||

| Hif1a | Hypoxia-inducible factor 1, α subunit | 2.10 × 10−6 | ||

P values for the overexpressed stromal gene transcripts are as shown. Data were extracted from Supplemental Tables S1–S3 found in Pavlides et al.47 See the Materials and Methods for more details. Transcripts highlighted in bold are associated with recurrence and/or metastasis.

PI3K, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase.

Table 2.

Transcriptional Overexpression of S6-Kinase and Ribosomal Proteins in Cav-1–Deficient Tumor Stroma Isolated from Breast Cancer Patients

| Symbol | Gene description | P value | Fold change (Cav-1−/Cav-1+) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ribosomal protein S6 kinase | |||

| Rps6ka3 | Ribosomal protein S6 kinase, polypeptide 3 | 0.01 | 1.90 |

| Rps6ka3 | Ribosomal protein S6 kinase, polypeptide 3 | 0.04 | 1.89 |

| Ribosomal proteins | |||

| Rps16 | Ribosomal protein S16 | 0.02 | 3.86 |

| Rps16 | Ribosomal protein S16 | 0.05 | 3.19 |

| Rps7 | Ribosomal protein S7 | 0.06 | 2.62 |

| Rps27 | Ribosomal protein S27 | 0.01 | 2.57 |

| Rps15A | Ribosomal protein S15a | 0.02 | 2.40 |

| Rps9 | Ribosomal protein S9 | 0.1 | 1.92 |

| LOC100129381 | Predicted: similar to ribosomal protein S7 | 0.04 | 1.69 |

| Rps14 | Ribosomal protein S14 | 0.04 | 1.66 |

| Rpl7l1 | Ribosomal protein L7-like 1 | 0.08 | 1.35 |

| Mitochondrial ribosomal proteins | |||

| Lactb | Mitochondrial 39S ribosomal protein L56; β-lactamase | 0.002 | 4.62 |

| Lactb | Mitochondrial 39S ribosomal protein L56; β-lactamase | 0.04 | 1.80 |

| Mrpl9 | Mitochondrial ribosomal protein L9 | 0.003 | 2.11 |

| Mrpl9 | Mitochondrial ribosomal protein L9 | 0.005 | 1.87 |

| Mrpl49 | Mitochondrial ribosomal protein L49 | 0.04 | 1.84 |

| Mrpl2 | Mitochondrial ribosomal protein L2 | 0.06 | 1.70 |

| Mrps7 | Mitochondrial ribosomal protein S7 | 0.05 | 1.48 |

| Upstream activators of S6 kinase | |||

| Akt3 | V-AKT thymoma viral oncogene homolog 3 | 0.03 | 2.62 |

| Pdpk1 | PI3–dependent protein kinase-1 | 0.007 | 2.15 |

| Mtor | Mammalian target of rapamycin (serine/threonine kinase) | 0.06 | 2.02 |

| Pik3cg | PI3K catalytic γ polypeptide | 0.1 | 1.93 |

| Pik3ap1 | PI3K adaptor protein 1 | 0.045 | 1.79 |

| Pik3c2a | PI3K class 2 α polypeptide | 0.05 | 1.50 |

| Rhebl1 | Ras homolog enriched in brain like 1 | 0.1 | 1.50 |

| Other mTOR downstream effectors/regulators | |||

| Ppp2r5c | Protein phosphatase2, regulatory subunit B′, γ | 0.02 | 3.00 |

| Prkag2 | Kinase AMP-activated γ 2 noncatalytic | 0.02 | 2.23 |

| Cdc42 | Cell division cycle 42 (GTP-binding protein 25 kd) | 0.03 | 1.81 |

| Hif1a | Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 α subunit | 0.1 | 1.39 |

| Eif4ebp2 | Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E binding | 0.1 | 1.33 |

P values and fold changes in stromal gene transcript expression are shown. Data were extracted from Supplemental Table S2 found in Witkiewicz et al.46 See the Materials and Methods for more details. Transcripts highlighted in bold overlap with the genes listed in Table 1. In some cases, more than one entry is shown for a gene transcript; these represent the results obtained with more than one probe set for a given gene transcript. The specific probe sets used are available in Supplemental Table S2 in Witkiewicz et al.46n = 4 patients with high stromal Cav-1, and n = 7 patients with absent stromal Cav-1. As a consequence, gene transcripts with a P ≤ 0.1 were included, because of the small sample size.

PI3K, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase.

Results

Cav-1–Negative Mammary Stroma Accelerates Met-1 Tumor Growth in Vivo

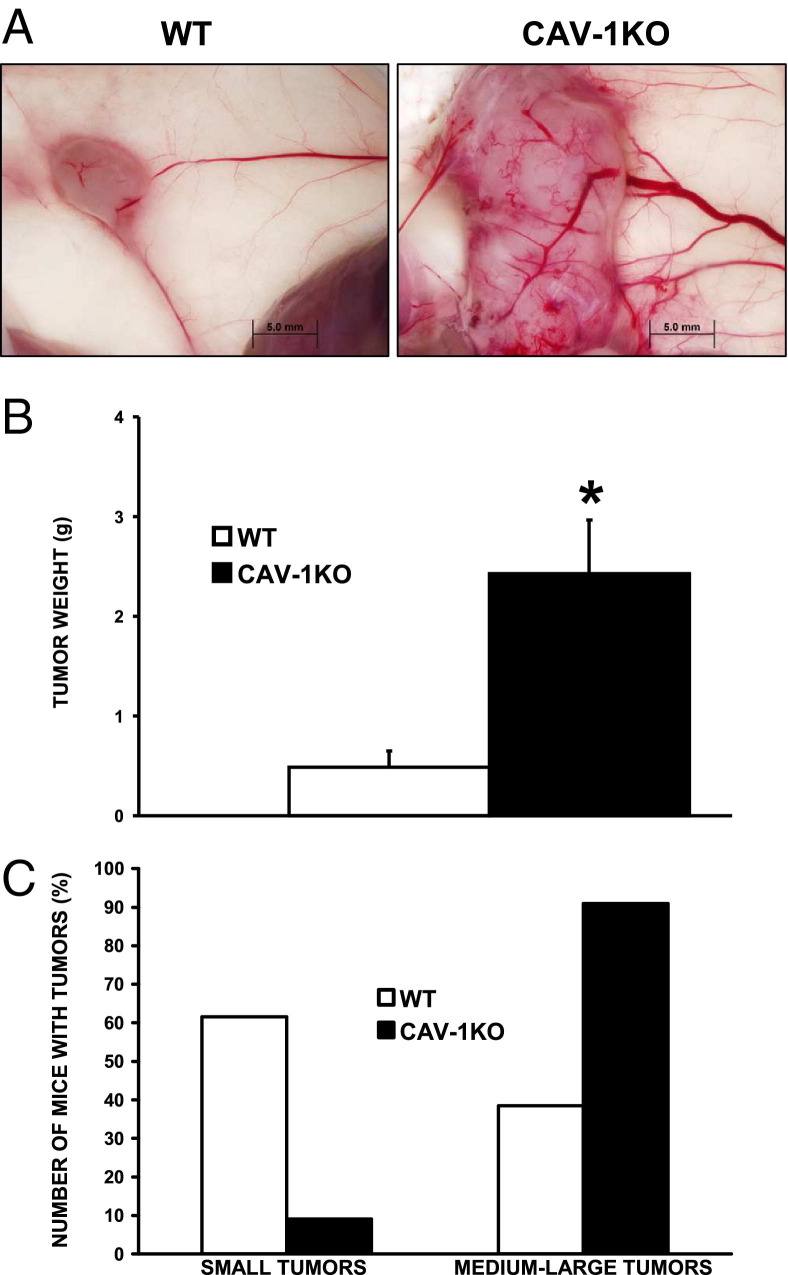

Recent reports have shown an association between reduced stromal Cav-1 and unfavorable outcome in breast cancer patients.41 To understand the mechanisms underlying this phenomenon, we injected Met-1 into WT and Cav-1 KO mouse mammary fat pads. As shown in Figure 1A, the tumors grown in Cav-1 KO mammary fat pads were significantly larger and more vascularized than those grown in their WT counterparts. Quantitatively, as shown in Figure 1B, Met-1 tumors grown in the fat pads of Cav-1 KO mice were approximately fivefold larger than those grown in WT fat pads (n = 11 and n = 13, respectively; P < 0.01). When tumor size was further examined, approximately 90% of the Cav-1 KO mice developed medium-to-large tumors compared with only approximately 40% in the WT group (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

Cav-1–negative mammary stroma increases mammary tumor growth in vivo. A: Representative images of mammary glands after orthotopic injections of Met-1 cells show accelerated tumor growth in Cav-1 KO mice. Images were acquired using an Olympus DP71 camera (Center Valley, PA) with DP manager software (MacKinney Systems, Springfield, MO) version 3.1.1.208, using a ×1.5 objective. B: Quantitative analysis of tumor weight shows an approximately fivefold increase. *P < 0.001 (n = 11 to 13 per group). Mice were injected in the right mammary fat pad, resulting in only one tumor per mouse. C: Approximately 90% of the Cav-1 KO mice developed medium-large tumors compared with only 40% in the WT group.

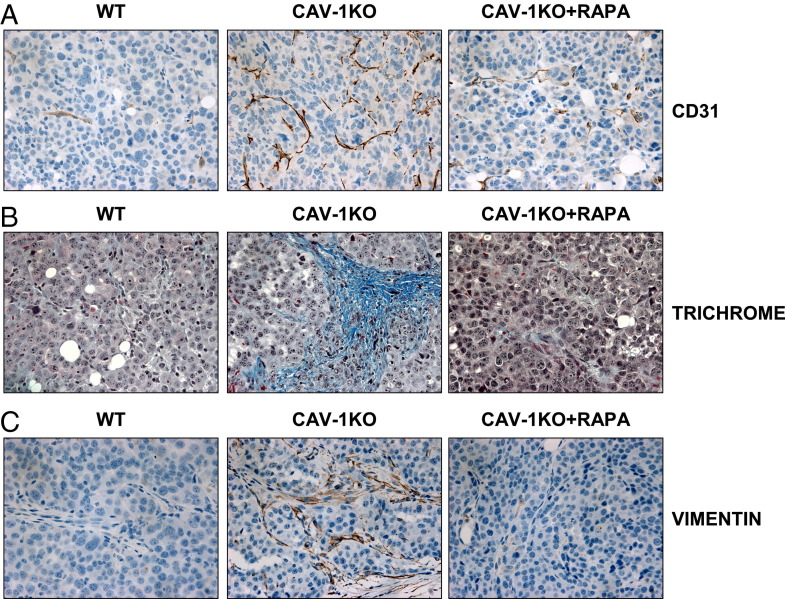

Mammary Tumors Grown in Cav-1 KO Mice Display Increased Angiogenesis and More Stromal Content

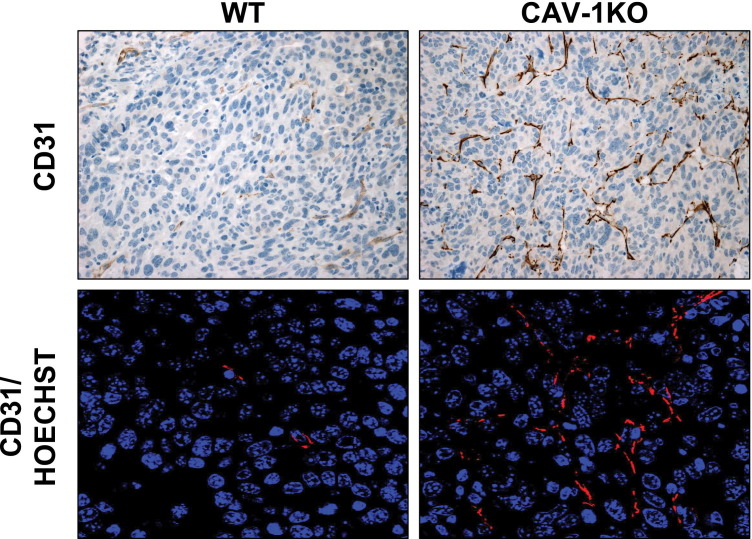

For a tumor to grow beyond approximately 2 mm in diameter, the generation of new blood vessels is necessary, a process known as angiogenesis.54 As such, we postulated that increased angiogenesis could contribute to the accelerated tumor growth observed in Cav-1 KO fat pads. In fact, tumors grown in Cav-1 KO mammary fat pads are more vascularized, as reflected by an increased abundance of CD31-positive vessels (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Cav-1–negative mammary stroma increases tumor vascularization. Representative images of CD31 staining of tumors resulting from Met-1 orthotopic injections show increased vessel formation in tumors grown in Cav-1 KO mammary fat pads. Staining shows results from IHC of CD31 (brown) with nuclear counterstain (blue) and confocal microscopy of CD31 (red) immunostaining and Hoechst (blue). Original magnification, ×40 (CD31) and ×63 (CD31/Hoechst).

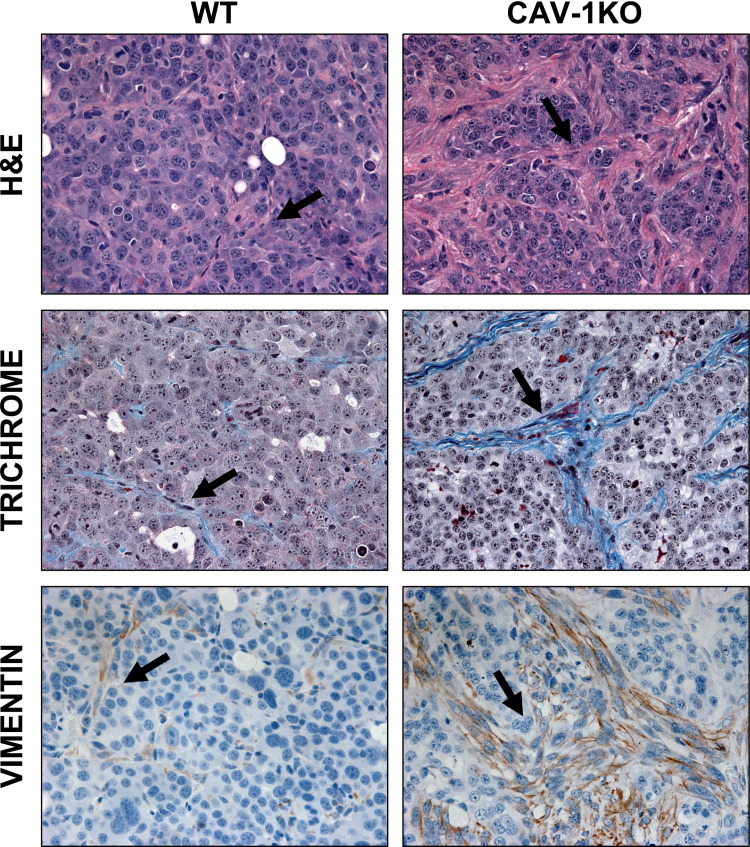

In addition to being larger and more vascularized, Cav-1 KO tumors were also significantly more stromalized (a high stroma/epithelia ratio). This is depicted in Figure 3 by increased Masson's trichrome staining (blue). An increase in collagen secretion is suggestive of the presence of fibroblasts (Figure 3).55 In fact, increased vimentin staining, a marker of myofibroblasts, was also observed in tumors grown in Cav-1 KO fat pads (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Increased amounts of stroma in tumors grown in Cav-1 KO fat pads. A complex collagen network was detected in H&E-stained tumors by an intense pink staining. Masson's trichrome stain also reveals the presence of collagen, as depicted by a blue stain. To detect the presence of fibroblasts embedded within the collagen network, tumors were immunostained with a vimentin antibody. Cav-1 KO tumors have more vimentin-positive cells. Arrows, stromal cells. Original magnification, ×60.

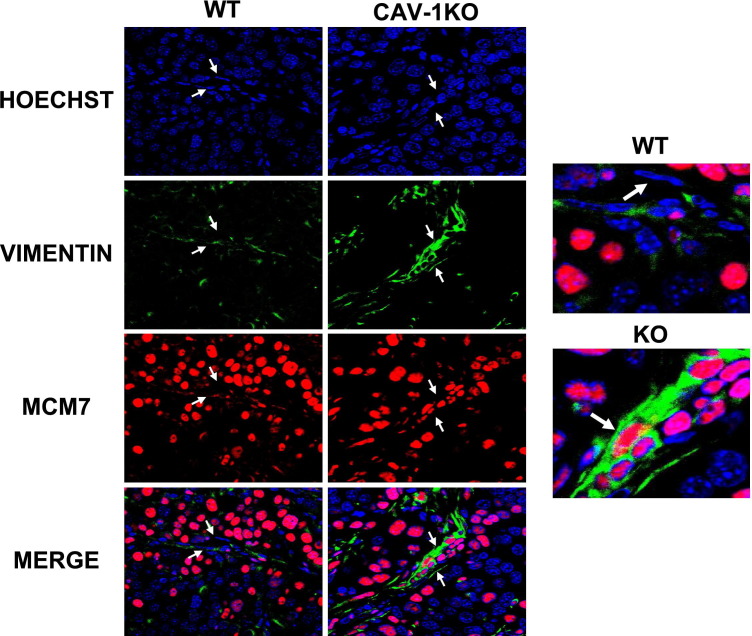

Tumor Stroma of Cav-1 KO Mice Is Hyperproliferative

The increased collagen deposition and vimentin-positive staining in Cav-1 KO fat pads suggested the presence of stromal proliferative fibroblasts. As predicted, dual labeling with a proliferation marker (MCM7) and vimentin antibody revealed that Cav-1 KO stromal cells were more proliferative (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Increased vimentin and stromal MCM7 in tumors grown in Cav-1 KO fat pads. Confocal microscopy demonstrating dual labeling of vimentin and MCM7 is shown. These results demonstrate that tumors grown in a Cav-1 KO fat pad have increased levels of proliferating fibroblasts, as shown by increased expression of nuclear MCM7 staining in vimentin-positive cells. Representative fields were taken using a ×63 oil objective. Hoechst 33342 was used as a nuclear counterstain (blue), along with vimentin (green) and MCM7 (red). Arrows, stromal cells.

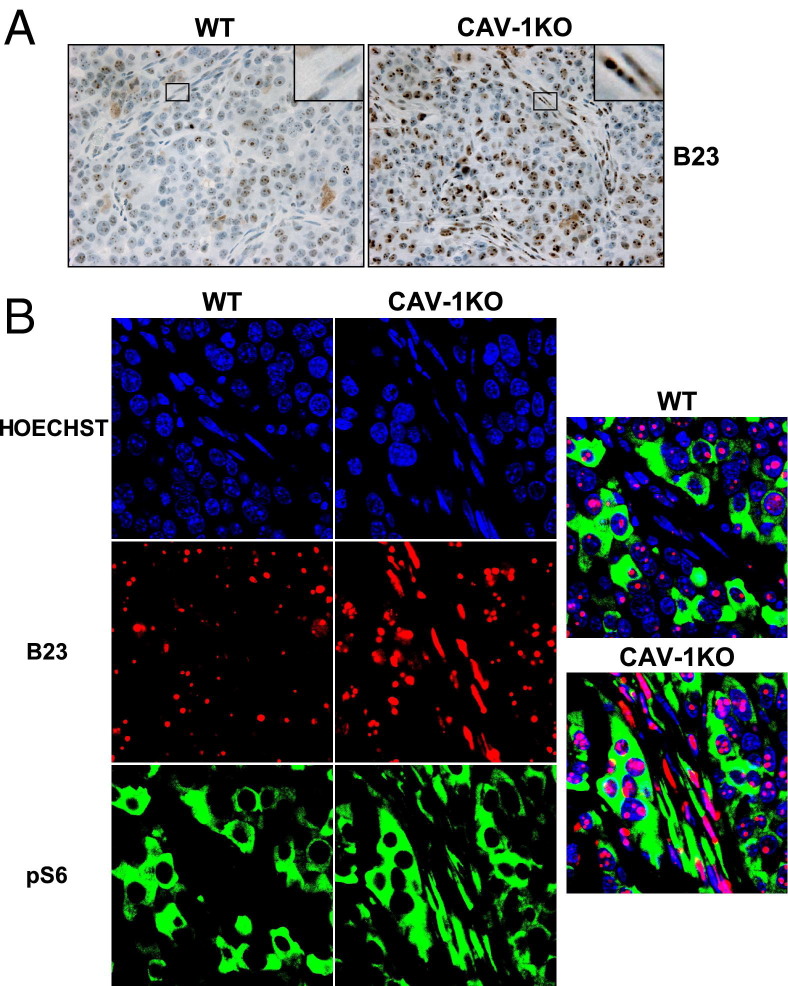

Cav-1 KO CAFs Show Hypertrophied Nucleoli and Elevated Levels of Nucleophosmin/B23

Cav-1–negative CAFs found in mammary tumors were more proliferative; thus, we predicted that they would have an increased need for protein synthesis. Our IHC results revealed that CAFs in Cav-1–negative tumors showed enhanced B23/nucleophosmin expression, a nucleolar protein involved in ribosomal biosynthesis56–58 (Figure 5, A and B).

Figure 5.

Increased levels and colocalization of nucleophosmin/B23 and phospho-S6 in tumors grown in Cav-1 KO mice. A: Cav-1 KO mice have increased levels of stromal nucleophosmin/B23, as depicted by brown staining. B: The stromal cells in Cav-1 KO tumors that are positive for nucleophosmin/B23 staining (red) are also positive for pS6 staining (green). A merged image is shown (right panel). All images were acquired using a ×100 oil objective.

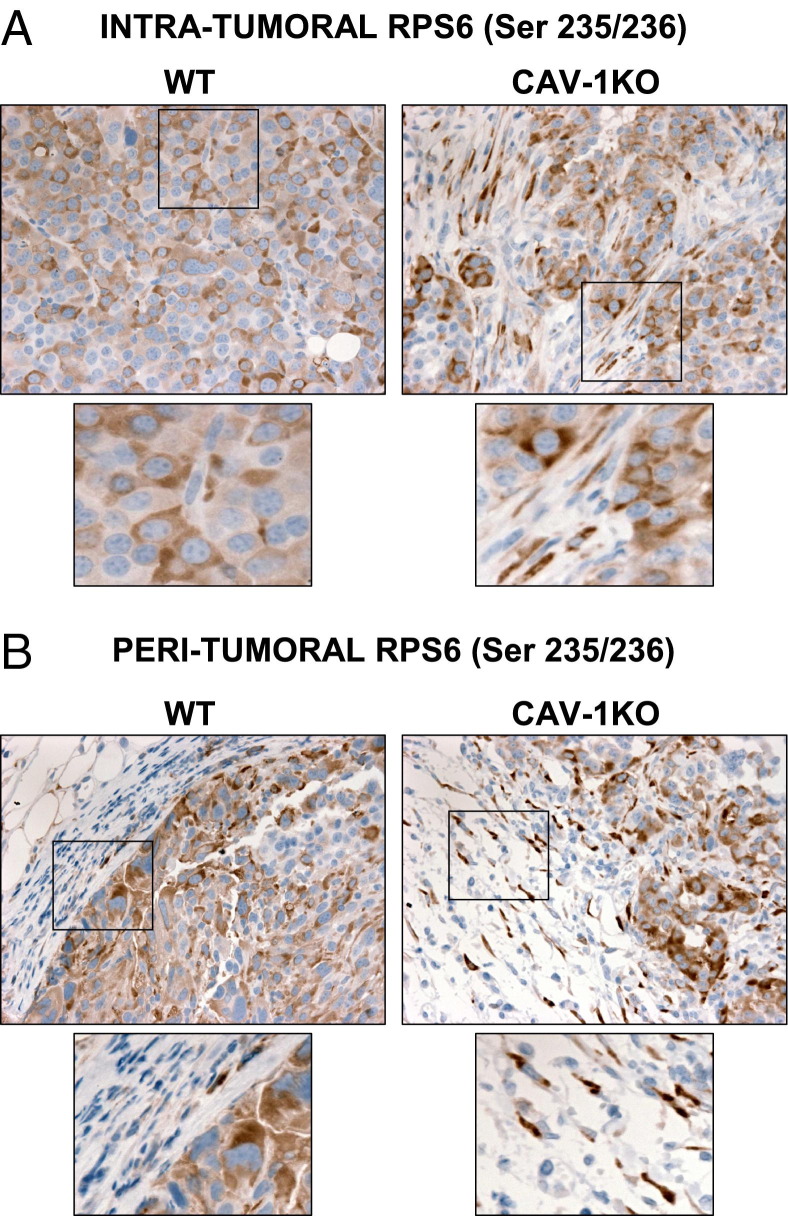

Cav-1 KO Tumor Stroma Displays an Activated mTOR Pathway

To date, few studies have examined the contribution of stromal protein synthesis machinery in tumor growth and progression. In fact, Cav-1 KO mammary tumors showed increased phosphorylation of the ribosomal protein S6 at serine 235/236 (pS6), a downstream effector of mTOR activity.59 As depicted in Figure 6, we observed an inverse relationship between Cav-1 and pS6 expression in stromal fibroblasts. Fibroblasts found both inside and outside the Cav-1 KO tumors had more pS6 compared with those in WT tumors (Figure 6, A and B). In contrast, epithelial pS6 remained unaffected by the presence of Cav-1 (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Tumors grown in Cav-1 KO mice have increased expression of stromal phospho-S6. Tumors grown in Cav-1 KO mice display increased pS6 staining (brown) in the fibroblasts embedded within the tumors (A) and in the fibroblasts surrounding the tumors (B). In contrast, WT fibroblasts express significantly less pS6 staining. Original magnification, ×40.

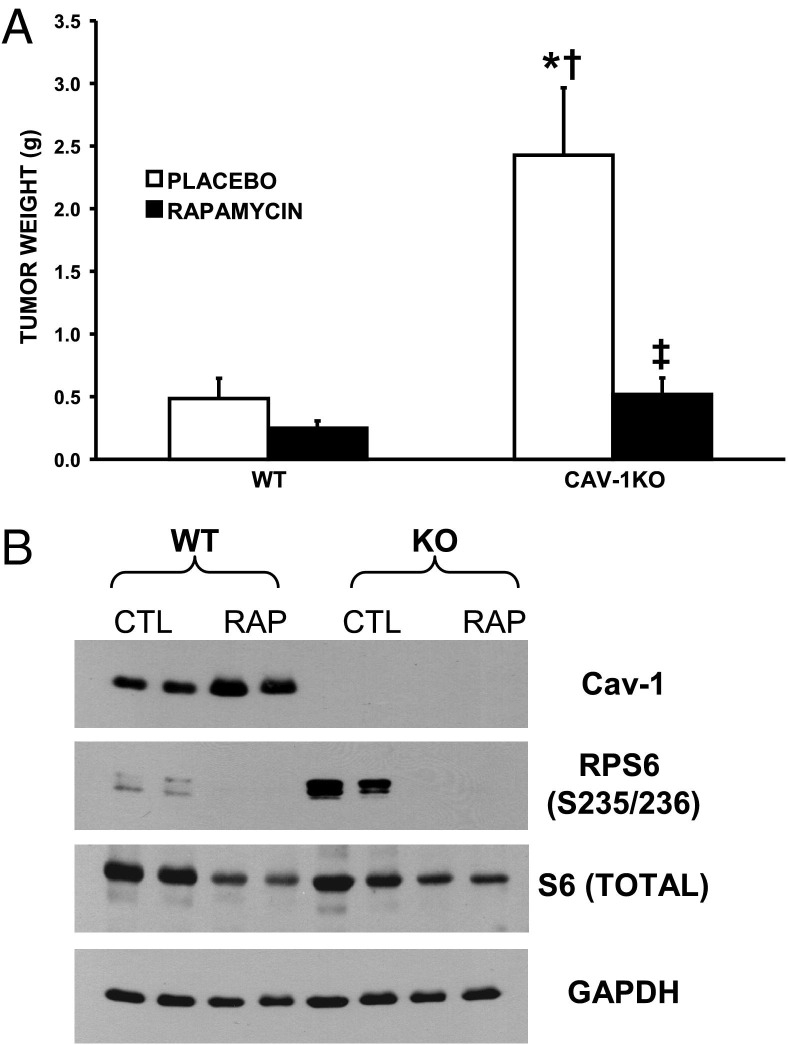

Rapamycin, an mTOR Inhibitor, Prevents the Growth of Cav-1 KO Mammary Tumors

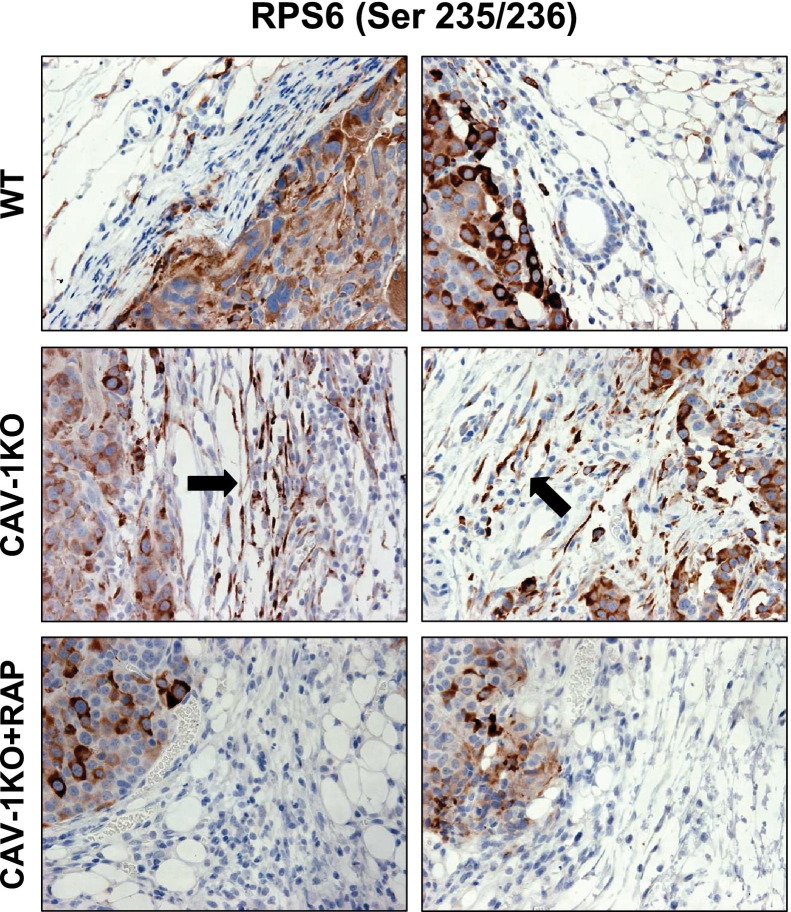

Hyperactivation of the protein synthesis machinery and increases in mTOR pathway signaling in Cav-1 KO CAFs might contribute to the accelerated growth of mammary tumors. To test this hypothesis, mice injected with Met-1 cells were treated with rapamycin (RAPA), a specific mTOR inhibitor. Remarkably, daily rapamycin treatment (2.78 μg/kg per day) for 5 weeks prevented mammary tumor growth in Cav-1 KO mice, as reflected by tumor weight (Figure 7A; n = 11 and n = 12, respectively; P < 0.001). To ensure the dose of rapamycin used was sufficient to inhibit mTOR activity, we assessed the levels of pS6, its downstream effector. As depicted in Figure 7B, although the levels of pS6 were significantly elevated in tumors grown in Cav-1 KO mice, rapamycin treatment prevented mTOR activity. This observation was also independently validated by IHC (Figure 8). Rapamycin treatment prevented tumor growth in Cav-1 KO mice and also decreased collagen deposition, vimentin staining, and angiogenesis (Figure 9, A–C).

Figure 7.

Tumors grown in Cav-1 KO fat pads are rapamycin sensitive. A: Tumor growth in Cav-1 KO mice was reduced by as much as 4.7-fold after rapamycin treatment when compared with placebo-treated mice (P < 0.001). For rapamycin treatment, 11 WT and 12 Cav-1 KO mice received rapamycin treatment, whereas 13 WT and 11 Cav-1 KO mice received placebo only. B: Western blot analysis showing the hyperactivation of pS6 and its complete inhibition by rapamycin treatment. Total S6, GAPDH, and Cav-1 are shown as control (CTL) of equal loading and to demonstrate the lack of Cav-1 in the tumor stroma of Cav-1 KO mice. *P < 0.001 vs WT-placebo; †P < 0.001 vs WT-rapamycin; ‡P < 0.001 vs Cav-1 KO-placebo.

Figure 8.

Status of stromal phospho-S6 immunostaining in mammary tumors after rapamycin treatment in WT and Cav-1 KO mice. After a 5-week treatment with rapamycin, the tumor size reverts to that of WT tumors. Mammary tumor sections were immunostained with a phospho-specific antibody directed against phospho-S6. Tumors grown in Cav-1 KO mice display increased pS6 staining (brown) in the tumor-associated fibroblasts (arrows); this staining was ablated by rapamycin treatment (Cav-1 KO + RAP) and appears as tumors grown in a WT microenvironment.

Figure 9.

Morphological characteristics of mammary tumors after rapamycin (RAPA) treatment in WT and Cav-1 KO mice. After a 5-week treatment with rapamycin, the tumor size reverts to that of WT tumors. Rapamycin significantly decreases the levels of angiogenesis (A), collagen deposition (B), and the total number of fibroblasts in the tumor stroma (C), as depicted by CD31 (A), trichrome (B), and vimentin (C) immunostains, respectively. Original magnification, ×60 objective.

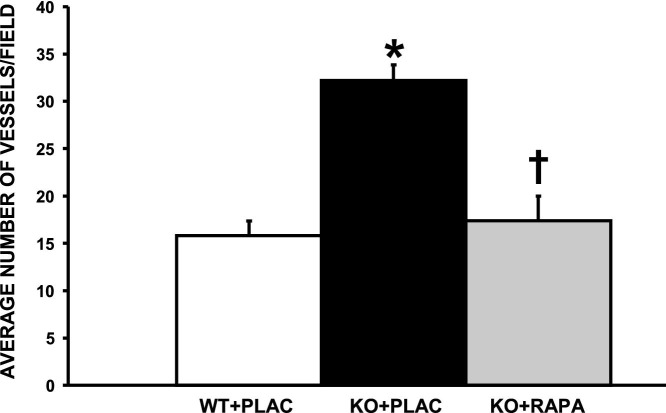

CD31-Positive Vessels Are Decreased in the Tumors of Cav-1 KO Mice Treated with Rapamycin

As depicted in Figure 9, the tumors grown in Cav-1 KO mice had increased CD31 staining, suggesting an increase in angiogenesis. To quantitatively assess the levels of angiogenesis, the number of blood vessels was counted by assessing CD31-positive vessels in each tumor before and after rapamycin treatment. Although tumors grown in Cav-1 KO fat pads had >30 blood vessels per field, the number of vessels decreased almost twofold after rapamycin treatment, reaching the levels observed in the tumors grown in WT mice (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Blood vessel quantitation in the tumors grown in WT and Cav-1 KO mice before and after rapamycin (RAPA) treatment, showing the number of blood vessels per field. A total of five fields were photographed at ×40 magnification per group and averaged. *P < 0.001 between Cav-1 KO (KO) and WT; †P < 0.001 between Cav-1 KO + placebo (PLAC) and Cav-1 KO + RAPA.

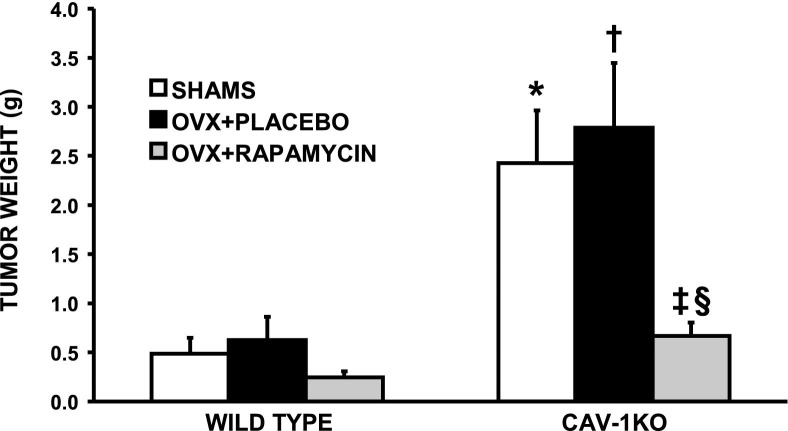

Mammary Tumor Growth in Cav-1 KO Mice Is Hormone Independent

To exclude the possibility that mammary tumors grew faster in Cav-1 KO fat pads because of differential hormonal sensitivity of the host's mammary fat pad, we performed a bilateral ovariectomy (OVX). Figure 11 shows that tumor formation was not affected by depletion of ovarian hormones in both WT and Cav-1 KO mice. The success of the ovariectomy procedure was confirmed by measuring uterine atrophy, as previously described.50 Interestingly, tumors still grew approximately 4.5-fold bigger in ovariectomized Cav-1 KO mice when compared with their WT counterparts (P < 0.01; n = 9 and n = 12, respectively). Most important, even in the absence of ovarian hormones, rapamycin successfully prevented tumor growth in Cav-1 KO mice (4.2-fold; P < 0.01 compared with Cav-1 KO/OVX-placebo). Also important, there was no significant difference between Cav-1 KO/Sham-RAPA versus Cav-1 KO/OVX-RAPA (P = 0.486).

Figure 11.

Accelerated mammary tumor growth in Cav-1 KO mice is hormone independent. Tumor weight after tumor cell injection and rapamycin treatment in OVX WT and Cav-1 KO mice is depicted. Cav-1 KO mice develop larger tumors and remain rapamycin sensitive in the absence of ovarian hormones. *P < 0.001 versus WT sham; †P < 0.001 versus WT-OVX-PLACEBO; ‡P < 0.01 versus Cav-1 KO-OVX-PLACEBO; §P < 0.05 versus Cav-1 KO sham.

Transcriptional Evidence that mTOR/S6-Kinase Signaling in the Tumor Microenvironment Is Increased in Human Breast Cancer Patients

To further assess the clinical relevance of our current findings, we next re-examined the transcriptional profiles of human tumor stroma that was isolated from a series of breast cancer patients, via laser-capture microdissection.53 These data included three complementary gene sets that were also associated with clinical outcome.47 i) The Tumor Stroma versus Normal Stroma List evaluated the transcriptional profiles of tumor stroma obtained from 53 patients with normal stroma obtained from 38 patients (containing 6777 genes).47 ii) The Recurrence Stroma List evaluated the transcriptional profiles of tumor stroma obtained from 11 patients (with tumor recurrence) with the tumor stroma of 42 patients (without tumor recurrence) (containing 3354 genes).47 iii) The Lymph-Node (LN) Metastasis Stroma List evaluated the transcriptional profiles of tumor stroma (obtained from 25 patients with LN metastasis) with the tumor stroma of 25 patients (without LN metastasis) (containing 1182 genes).47 All gene transcripts that were up-regulated in the tumor stroma of patients were all selected and assigned a P value, with a cutoff of P < 0.05.

The results of this analysis are summarized in Table 1. Many gene transcripts associated with mTOR/S6-kinase signaling, and S6-kinase itself, and other ribosomal proteins were all specifically up-regulated in the tumor stroma of human breast cancer patients. Interestingly, many mitochondrial ribosomal proteins were also up-regulated. Such a large increase in the anabolic protein synthesis machinery may be a necessary stress response to compensate for the onset of catabolic protein degradation, via autophagy and mitophagy, in the tumor stroma. Many of these overexpressed transcripts were also specifically associated with tumor recurrence and LN metastasis.

To further assess the association of mTOR/S6-kinase signaling with a Cav-1–deficient tumor stroma, we next re-examined the gene profiles obtained from human tumor stroma isolated from breast cancer patients that were separated based on the status of stromal Cav-1.46 The results of this analysis are summarized in Table 2. Importantly, many of the same mTOR/S6-kinase–related gene transcripts were specifically elevated in patients with a loss of stromal Cav-1 (highlighted in bold), as predicted. In this regard, Lactb (a mitochondrial ribosomal protein) is one of the gene transcripts that was most highly up-regulated in the stroma of patients with a loss of Cav-1. In light of these clinical data, our current results using Cav-1–deficient mice as a preclinical model may have important translational significance for human breast cancer patients.

Discussion

New evidence suggests a dynamic function of the surrounding tumor stroma in breast cancer pathogenesis.60–63 Cav-1, an important tumor suppressor, was recently shown to be expressed in the tumor-associated stroma.35,36 Importantly, a loss of stromal Cav-1 is a powerful predictive biomarker that is associated with early tumor recurrence, LN metastasis, and tamoxifen resistance, driving poor clinical outcome in breast cancer patients.35–39 Although these clinical data suggest that Cav-1 can serve as a predictive biomarker of disease outcome, more studies were warranted to understand the mechanisms involved.

To gain a better understanding of the prognostic value of a loss of stromal Cav-1, mammary tumor cells isolated from the MMTV-PyMT tumor model (Met-1) were injected into the mammary fat pads of WT and Cav-1 KO mice. Interestingly, a lack of Cav-1 expression in the mammary fat pad greatly accelerated tumor formation. The present results are in accordance with previous tumor transplantation experiments in Cav-1 KO fat pads, which also suggested a growth-inhibiting property of stromal Cav-1.64 Furthermore, recent xenografts and co-injection experiments showed that knockdown of Cav-1 expression in human immortalized fibroblasts was sufficient to accelerate the growth of MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells.12

A striking morphological feature of the mammary tumors grown in Cav-1 KO fat pads was the increased amount of collagen deposition and the presence of spindle-shaped fibroblasts embedded within the tumor mass (Figure 3). In contrast, tumors grown in WT mammary fat pads were almost entirely epithelial. Previous studies described the prognostic value of an abundant stroma (stroma rich) versus an epithelial-dominant tumor mass (stroma poor). For example, colon and breast tumors with abundant stroma showed an increased risk of relapse and a poor prognosis.65,66 More specifically, TN breast tumors with less stroma have a 5-year relapse-free rate of 81% compared with 56% for those with abundant stroma. Mechanistically, the prominence of collagen deposition and an increased number of fibroblasts found in the Cav-1 KO tumor stroma could be explained by increased stromal proliferation. In fact, Cav-1 KO CAFs showed increased nuclear expression of the proliferative marker MCM7 (Figure 4). These results suggest that a lack of stromal Cav-1 in tumor could promote the proliferation of fibroblasts.

Increased nucleolar prominence has been used to predict cellular transformation for years, and abnormalities in nucleolar shape have been reported in cancer as early as the 19th century.67 The nucleolus is an important cellular component involved in ribosome production. Most often, increased cellular proliferation results in an increased demand for cellular constituents, leading to increased protein synthesis, ribosome production, and nucleolar hypertrophy.68 In fact, we noticed that Cav-1 KO CAFs have more prominent nucleoli and hypothesized that they required increased protein synthesis to sustain their greater proliferative rates. Accordingly, Cav-1 KO CAFs expressed significantly more B23/nucleophosmin, a nucleolar protein necessary for ribosomal RNA transcription and processing (Figure 5).

mTOR, the mammalian target of rapamycin, is a serine/threonine kinase that is often overexpressed or activated in cancer cells and that regulates protein synthesis, cell growth, and survival. Few studies have examined the role of the mTOR pathway in CAFs and tumor growth.69 Consistent with B23/nucleophosmin overexpression, a remarkable increase in mTOR activity was observed in Cav-1 KO CAFs, as reflected by increased pS6 protein levels (Figures 6 and 7). Consistent with an activated mTOR pathway in the stroma of Cav-1–depleted mammary tumors, these tumors were highly responsive to mTOR inhibitors, such as rapamycin, as seen by the prevention of tumor growth (Figure 7). To our knowledge, although this is the first report of mTOR activation in Cav-1 KO CAFs. A recent study reported that keloids, a dermal fibroproliferative disorder of scar fibroblasts, also display hyperactivation of the mTOR pathway.70 In fact, the proliferation of keloids can be inhibited by rapamycin.70 The hyperactivation of mTOR in Cav-1 KO CAFs is not surprising because they share several similarities with keloids, such as increased proliferation, aberrant growth factor secretion, and increased extracellular matrix production and contractile proteins.71,72 Interestingly, recent reports have shown that stromal phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN), an upstream inhibitor of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, can inhibit mammary tumor development in an ErB2 breast cancer mouse model.73

Morphologically, rapamycin-treated Cav-1 KO tumors showed less collagen, had decreased tumor-associated fibroblasts, and had significantly less angiogenesis, as reflected by decreased CD31 staining; all of these characteristics predict a good clinical outcome in patients65,66,74–77 (Figure 9). Previous reports have suggested that human breast CAFs can directly promote angiogenesis through the expression of stromal cell–derived factors.78,79 Furthermore, we previously reported that a lack of Cav-1 expression in mammary fat pads is linked to increased angiogenesis. Indeed, mammary fibroblasts derived from Cav-1 KO mice revealed increased levels of angiogenesis-related gene transcripts.50,72 The decrease in angiogenesis observed after rapamycin treatment in tumors grown in Cav-1 KO mice (Figure 10) is interesting and might suggest the involvement of the stromal mTOR pathway on blood vessel formation in these Cav-1–deficient stromal tumors.

Previous reports have suggested that the anti-tumor effects of rapamycin are estrogen dependent, thus neglecting its potential therapeutic efficacy in estrogen-independent and tamoxifen-resistant breast cancer patients.80 To test whether rapamycin would retain its therapeutic potential in breast cancer patients with low stromal Cav-1 in the absence of ovarian hormones, we subjected the mice to bilateral ovariectomies. Interestingly, the accelerated tumor growth observed in Cav-1 KO mice was maintained after the ovariectomy procedure (Figure 11). These results suggest a hormone-independent role for stromal Cav-1 in breast tumor growth. More important, rapamycin also dramatically prevented tumor growth in ovariectomized Cav-1 KO mice. The present results suggest the potential clinical value of mTOR inhibitors in premenopausal and postmenopausal TN breast cancer patients with decreased stromal Cav-1, as well as in estrogen receptor–positive tamoxifen-resistant breast cancer patients.

Recent mechanistic studies have proposed that Cav-1 might constitute an important link between cancer cells and the tumor stroma.8 Metabolomics and gene profiling studies of the Cav-1 KO mammary gland have revealed signatures associated with oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and aerobic glycolysis.8 This new model proposes that a loss of Cav-1 expression is sufficient to induce oxidative stress in stromal fibroblasts. These events result in lysosome-driven degradation of organelles (autophagy or mitophagy) in CAFs, which release energy-rich nutrients. These recycled stromal nutrients can then be used by the adjacent epithelial cancer cells, resulting in net energy transfer to cancer cells and accelerated tumor growth.8,10,11,81

The phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/mTOR/S6-kinase pathway has previously been linked to oxidative stress.82–85 S6-kinase is the upstream activator of pS6 and was recently required for starvation-induced autophagy.86,87 High levels of autophagy can actually be detrimental to cells,87 and mTOR activation protects cells against high levels of autophagy.87–89 Thus, the increased mTOR/S6-kinase signaling observed in Cav-1 KO CAFs might be a compensatory response to protect fibroblasts from abnormally high levels of autophagy. Interestingly, Narita et al90 have recently come to a similar conclusion.91 They directly showed that anabolic protein synthesis, via mTOR signaling, is an important stress response in cells undergoing catabolic protein degradation via enhanced autophagy,90 and may lead to an enhanced secretory phenotype, with the increased production of IL-6 and IL-8.90 However, they did not examine the role of Cav-1 in this process or relate this metabolic phenotype to tumorigenesis.

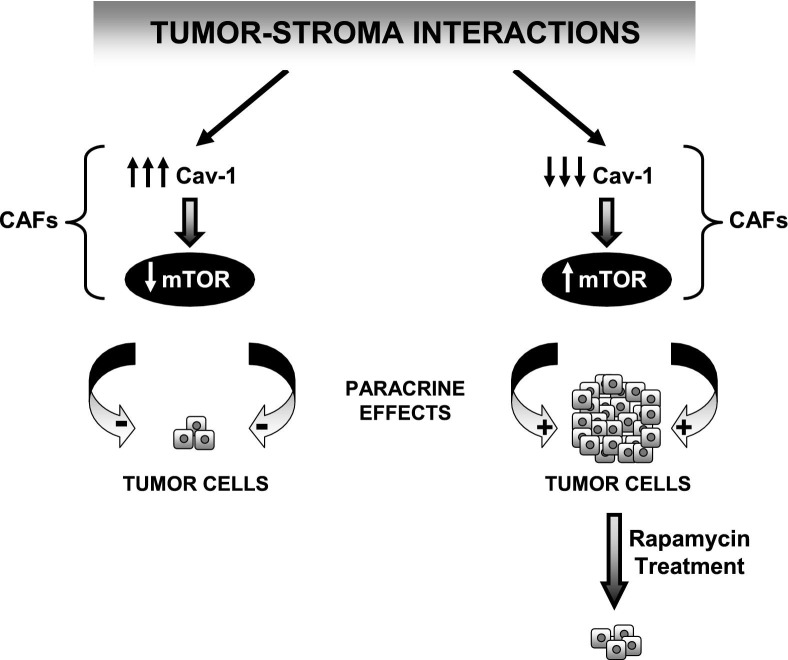

The role of the mTOR pathway in oxidative stress–induced proliferation was also previously reported. Hydrogen peroxide can induce the proliferation of lung cells that, in turn, can be inhibited by rapamycin.82 Some reports also suggest that retinoblastoma (RB) is a downstream target of mTOR in adipocytes and prostate and ovarian cancer cells.92–94 Interestingly, we previously reported dysregulation of the RB pathway by Cav-1 in human breast CAFs.71 Thus, the increased proliferative potential of Cav-1–negative CAFs surrounding breast tumors might contribute toward a worse prognosis due to mTOR-dependent oxidative stress–induced proliferation, suggesting a new axis in the stroma of breast tumors (Cav-1→mTOR→RB) (Figure 12). Whether breast cancer patients with low stromal Cav-1 expression have more CAFs, increased stromal mTOR, and an inactivated RB pathway remains to be examined.

Figure 12.

Mechanistic diagram summarizing the function of stromal Cav-1 in the mTOR pathway and tumor growth. The levels of Cav-1 expression in the CAFs dictate how tumor cells grow in the mammary fat pad. Fibroblasts lacking Cav-1 expression display significantly more mTOR activation, causing the surrounding tumor cells, through paracrine actions, to grow and develop into significantly larger tumors. This accelerated growth induced by a Cav-1–negative stroma can be specifically prevented by the pharmacological inhibition of the mTOR pathway with rapamycin.

Apart from its role in autophagy and cancer, mTOR hyperactivation was recently linked to aging.28 For instance, rapamycin treatment can increase the life span of cancer-prone mice.95 Interestingly, a loss of Cav-1 in mice results in accelerated aging and a decreased life span.1,2 Whether rapamycin treatment could increase the longevity of Cav-1 KO mice remains to be determined. The current results suggest that a Cav-1–negative tumor stroma possesses all of the characteristics of an aging organ and might contribute to poor disease outcome and shorten the life span of patients because of hyperactivated stromal mTOR signaling.

In conclusion, the present study investigated the downstream mechanisms involved in the growth-promoting effects of a Cav-1–negative tumor stroma in mammary tumors. We show that Cav-1–negative stroma provides a fertile soil for breast tumor growth. These tumors display a proliferative stroma with hyperactivated mTOR signaling. The treatment of these mice with rapamycin prevented tumor growth, an effect independent of estrogen and progesterone. Thus, our results suggest that the levels of Cav-1 in the microenvironment (Cav-1 rich versus Cav-1 poor) can directly promote the growth of breast tumors, which can be prevented by mTOR inhibitors, such as rapamycin. Breast cancer patients with low stromal Cav-1 levels have a poor prognosis. Whether mTOR inhibitors could prevent tumor growth and increase survival rates in breast cancer patients with decreased stromal Cav-1 remain to be investigated and could have a major clinical impact. In conclusion, we describe a new network between stromal Cav-1 and mTOR signaling, which can be used to design more effective treatments for breast cancer patients.

Footnotes

Supported by grants from the NIH/National Cancer Institute (R01-CA-80250, R01-CA-098779, and R01-CA-120876 to M.P.L.), the American Association for Cancer Research (M.P.L), the Department of Defense–Breast Cancer Research Program (Synergistic Idea Award) (M.P.L.), a grant from the Pennsylvania Department of Health (M.P.L.), a postdoctoral fellowship from the Susan G. Komen Breast Cancer Foundation (I.M.), and a career catalyst award from the Susan G. Komen Breast Cancer Foundation (J.-F.J.).

The Pennsylvania Department of Health disclaims responsibility for any analyses, interpretations, or conclusions.

A guest editor acted as editor-in-chief for this manuscript. No person at Thomas Jefferson University or Albert Einstein College of Medicine was involved in the peer review process or final disposition for this article.

Contributor Information

Isabelle Mercier, Email: isabelle.mercier@jefferson.edu.

Michael P. Lisanti, Email: michael.lisanti@kimmelcancercenter.org.

References

- 1.Park D.S., Cohen A.W., Frank P.G., Razani B., Lee H., Williams T.M., Chandra M., Shirani J., De Souza A.P., Tang B., Jelicks L.A., Factor S.M., Weiss L.M., Tanowitz H.B., Lisanti M.P. Caveolin-1 null (−/−) mice show dramatic reductions in life span. Biochemistry. 2003;42:15124–15131. doi: 10.1021/bi0356348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Head B.P., Peart J.N., Panneerselvam M., Yokoyama T., Pearn M.L., Niesman I.R., Bonds J.A., Schilling J.M., Miyanohara A., Headrick J., Ali S.S., Roth D.M., Patel P.M., Patel H.H. Loss of caveolin-1 accelerates neurodegeneration and aging. PLoS One. 2010;5:e15697. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Woodman S.E., Cheung M.W., Tarr M., North A.C., Schubert W., Lagaud G., Marks C.B., Russell R.G., Hassan G.S., Factor S.M., Christ G.J., Lisanti M.P. Urogenital alterations in aged male caveolin-1 knockout mice. J Urol. 2004;171:950–957. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000105102.72295.b8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Razani B., Combs T.P., Wang X.B., Frank P.G., Park D.S., Russell R.G., Li M., Tang B., Jelicks L.A., Scherer P.E., Lisanti M.P. Caveolin-1-deficient mice are lean, resistant to diet-induced obesity, and show hypertriglyceridemia with adipocyte abnormalities. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:8635–8647. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110970200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohen A.W., Razani B., Schubert W., Williams T.M., Wang X.B., Iyengar P., Brasaemle D.L., Scherer P.E., Lisanti M.P. Role of caveolin-1 in the modulation of lipolysis and lipid droplet formation. Diabetes. 2004;53:1261–1270. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.5.1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cohen A.W., Razani B., Wang X.B., Combs T.P., Williams T.M., Scherer P.E., Lisanti M.P. Caveolin-1-deficient mice show insulin resistance and defective insulin receptor protein expression in adipose tissue. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2003;285:C222–C235. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00006.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cohen A.W., Schubert W., Brasaemle D.L., Scherer P.E., Lisanti M.P. Caveolin-1 expression is essential for proper nonshivering thermogenesis in brown adipose tissue. Diabetes. 2005;54:679–686. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.3.679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pavlides S., Tsirigos A., Migneco G., Whitaker-Menezes D., Chiavarina B., Flomenberg N., Frank P.G., Casimiro M.C., Wang C., Pestell R.G., Martinez-Outschoorn U.E., Howell A., Sotgia F., Lisanti M.P. The autophagic tumor stroma model of cancer: role of oxidative stress and ketone production in fueling tumor cell metabolism. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:3485–3505. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.17.12721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bosch M., Mari M., Herms A., Fernandez A., Fajardo A., Kassan A., Giralt A., Colell A., Balgoma D., Barbero E., Gonzalez-Moreno E., Matias N., Tebar F., Balsinde J., Camps M., Enrich C., Gross S.P., Garcia-Ruiz C., Perez-Navarro E., Fernandez-Checa J.C., Pol A. Caveolin-1 deficiency causes cholesterol-dependent mitochondrial dysfunction and apoptotic susceptibility. Curr Biol. 2011;21:681–686. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.03.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martinez-Outschoorn U.E., Balliet R.M., Rivadeneira D.B., Chiavarina B., Pavlides S., Wang C., Whitaker-Menezes D., Daumer K.M., Lin Z., Witkiewicz A.K., Flomenberg N., Howell A., Pestell R.G., Knudsen E.S., Sotgia F., Lisanti M.P. Oxidative stress in cancer associated fibroblasts drives tumor-stroma co-evolution: a new paradigm for understanding tumor metabolism, the field effect and genomic instability in cancer cells. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:3256–3276. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.16.12553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martinez-Outschoorn U.E., Trimmer C., Lin Z., Whitaker-Menezes D., Chiavarina B., Zhou J., Wang C., Pavlides S., Martinez-Cantarin M.P., Capozza F., Witkiewicz A.K., Flomenberg N., Howell A., Pestell R.G., Caro J., Lisanti M.P., Sotgia F. Autophagy in cancer associated fibroblasts promotes tumor cell survival: role of hypoxia: HIF1 induction and NFkappaB activation in the tumor stromal microenvironment. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:3515–3533. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.17.12928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Trimmer C., Sotgia F., Whitaker-Menezes D., Balliet R., Eaton G., Martinez-Outschoorn U.E., Pavlides S., Howell A., Iozzo R.V., Pestell R.G., Scherer P.E., Capozza F., Lisanti M.P. Caveolin-1 and mitochondrial SOD2 (MnSOD) function as tumor suppressors in the stromal microenvironment: a new genetically tractable model for human cancer associated fibroblasts. Cancer Biol Ther. 2011;11:383–394. doi: 10.4161/cbt.11.4.14101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pavlides S., Tsirigos A., Vera I., Flomenberg N., Frank P.G., Casimiro M.C., Wang C., Fortina P., Addya S., Pestell R.G., Martinez-Outschoorn U.E., Sotgia F., Lisanti M.P. Loss of stromal caveolin-1 leads to oxidative stress, mimics hypoxia and drives inflammation in the tumor microenvironment, conferring the “reverse Warburg effect”: a transcriptional informatics analysis with validation. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:2201–2219. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.11.11848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lisanti M.P., Martinez-Outschoorn U.E., Pavlides S., Whitaker-Menezes D., Pestell R.G., Howell A., Sotgia F. Accelerated aging in the tumor microenvironment: connecting aging, inflammation and cancer metabolism with personalized medicine. Cell Cycle. 2011;10:2059–2063. doi: 10.4161/cc.10.13.16233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lisanti M.P., Martinez-Outschoorn U.E., Lin Z., Pavlides S., Whitaker-Menezes D., Pestell R.G., Howell A., Sotgia F. Hydrogen peroxide fuels aging, inflammation, cancer metabolism and metastasis: the seed and soil also needs “fertilizer.”. Cell Cycle. 2011;10:2440–2449. doi: 10.4161/cc.10.15.16870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pavlides S., Whitaker-Menezes D., Castello-Cros R., Flomenberg N., Witkiewicz A.K., Frank P.G., Casimiro M.C., Wang C., Fortina P., Addya S., Pestell R.G., Martinez-Outschoorn U.E., Sotgia F., Lisanti M.P. The reverse Warburg effect: aerobic glycolysis in cancer associated fibroblasts and the tumor stroma. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:3984–4001. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.23.10238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martinez-Outschoorn U.E., Whitaker-Menezes D., Pavlides S., Chiavarina B., Bonuccelli G., Casey T., Tsirigos A., Migneco G., Witkiewicz A., Balliet R., Mercier I., Wang C., Flomenberg N., Howell A., Lin Z., Caro J., Pestell R.G., Sotgia F., Lisanti M.P. The autophagic tumor stroma model of cancer or “battery-operated tumor growth”: a simple solution to the autophagy paradox. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:4297–4306. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.21.13817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lisanti M.P., Martinez-Outschoorn U.E., Chiavarina B., Pavlides S., Whitaker-Menezes D., Tsirigos A., Witkiewicz A., Lin Z., Balliet R., Howell A., Sotgia F. Understanding the “lethal” drivers of tumor-stroma co-evolution: emerging role(s) for hypoxia, oxidative stress and autophagy/mitophagy in the tumor micro-environment. Cancer Biol Ther. 2010;10:537–542. doi: 10.4161/cbt.10.6.13370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martinez-Outschoorn U.E., Pavlides S., Howell A., Pestell R.G., Tanowitz H.B., Sotgia F., Lisanti M.P. Stromal-epithelial metabolic coupling in cancer: integrating autophagy and metabolism in the tumor microenvironment. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2011;43:1045–1051. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2011.01.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sotgia F., Martinez-Outschoorn U.E., Pavlides S., Howell A., Pestell R.G., Lisanti M.P. Understanding the Warburg effect and the prognostic value of stromal caveolin-1 as a marker of a lethal tumor microenvironment. Breast Cancer Res. 2011;13:213. doi: 10.1186/bcr2892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Whitaker-Menezes D., Martinez-Outschoorn U.E., Lin Z., Ertel A., Flomenberg N., Witkiewicz A.K., Birbe R.C., Howell A., Pavlides S., Gandara R., Pestell R.G., Sotgia F., Philp N.J., Lisanti M.P. Evidence for a stromal-epithelial “lactate shuttle” in human tumors: mCT4 is a marker of oxidative stress in cancer-associated fibroblasts. Cell Cycle. 2011;10:1772–1783. doi: 10.4161/cc.10.11.15659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Migneco G., Whitaker-Menezes D., Chiavarina B., Castello-Cros R., Pavlides S., Pestell R.G., Fatatis A., Flomenberg N., Tsirigos A., Howell A., Martinez-Outschoorn U.E., Sotgia F., Lisanti M.P. Glycolytic cancer associated fibroblasts promote breast cancer tumor growth, without a measurable increase in angiogenesis: evidence for stromal-epithelial metabolic coupling. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:2412–2422. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.12.11989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Toullec A., Gerald D., Despouy G., Bourachot B., Cardon M., Lefort S., Richardson M., Rigaill G., Parrini M.C., Lucchesi C., Bellanger D., Stern M.H., Dubois T., Sastre-Garau X., Delattre O., Vincent-Salomon A., Mechta-Grigoriou F. Oxidative stress promotes myofibroblast differentiation and tumour spreading. EMBO Mol Med. 2010;2:211–230. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201000073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bocchino M., Agnese S., Fagone E., Svegliati S., Grieco D., Vancheri C., Gabrielli A., Sanduzzi A., Avvedimento E.V. Reactive oxygen species are required for maintenance and differentiation of primary lung fibroblasts in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. PLoS One. 2010;5:e14003. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vendelbo M.H., Nair K.S. Mitochondrial longevity pathways. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1813:634–644. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2011.01.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Selman C., Tullet J.M., Wieser D., Irvine E., Lingard S.J., Choudhury A.I., Claret M., Al-Qassab H., Carmignac D., Ramadani F., Woods A., Robinson I.C., Schuster E., Batterham R.L., Kozma S.C., Thomas G., Carling D., Okkenhaug K., Thornton J.M., Partridge L., Gems D., Withers D.J. Ribosomal protein S6 kinase 1 signaling regulates mammalian life span. Science. 2009;326:140–144. doi: 10.1126/science.1177221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blagosklonny M.V. Rapamycin and quasi-programmed aging: four years later. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:1859–1862. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.10.11872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Blagosklonny M.V. TOR-driven aging: speeding car without brakes. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:4055–4059. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.24.10310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Blagosklonny M.V. Progeria, rapamycin and normal aging: recent breakthrough. Aging (Albany NY) 2011;3:685–691. doi: 10.18632/aging.100352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kapahi P., Chen D., Rogers A.N., Katewa S.D., Li P.W., Thomas E.L., Kockel L. With TOR, less is more: a key role for the conserved nutrient-sensing TOR pathway in aging. Cell Metab. 2010;11:453–465. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2010.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harrison D.E., Strong R., Sharp Z.D., Nelson J.F., Astle C.M., Flurkey K., Nadon N.L., Wilkinson J.E., Frenkel K., Carter C.S., Pahor M., Javors M.A., Fernandez E., Miller R.A. Rapamycin fed late in life extends lifespan in genetically heterogeneous mice. Nature. 2009;460:392–395. doi: 10.1038/nature08221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bjedov I., Partridge L. A longer and healthier life with TOR down-regulation: genetics and drugs. Biochem Soc Trans. 2011;39:460–465. doi: 10.1042/BST0390460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kauffman H.M., Cherikh W.S., Cheng Y., Hanto D.W., Kahan B.D. Maintenance immunosuppression with target-of-rapamycin inhibitors is associated with a reduced incidence of de novo malignancies. Transplantation. 2005;80:883–889. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000184006.43152.8d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Blagosklonny M.V. Prevention of cancer by inhibiting aging. Cancer Biol Ther. 2008;7:1520–1524. doi: 10.4161/cbt.7.10.6663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Witkiewicz A.K., Dasgupta A., Sotgia F., Mercier I., Pestell R.G., Sabel M., Kleer C.G., Brody J.R., Lisanti M.P. An absence of stromal caveolin-1 expression predicts early tumor recurrence and poor clinical outcome in human breast cancers. Am J Pathol. 2009;174:2023–2034. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sloan E.K., Ciocca D.R., Pouliot N., Natoli A., Restall C., Henderson M.A., Fanelli M.A., Cuello-Carrion F.D., Gago F.E., Anderson R.L. Stromal cell expression of caveolin-1 predicts outcome in breast cancer. Am J Pathol. 2009;174:2035–2043. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ghajar C.M., Meier R., Bissell M.J. Quis custodiet ipsos custodies: who watches the watchmen? Am J Pathol. 2009;174:1996–1999. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.090363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Qian N., Ueno T., Kawaguchi-Sakita N., Kawashima M., Yoshida N., Mikami Y., Wakasa T., Shintaku M., Tsuyuki S., Inamoto T., Toi M. Prognostic significance of tumor/stromal caveolin-1 expression in breast cancer patients. Cancer Sci. 2011;102:1590–1596. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2011.01985.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Koo J.S., Park S., Kim S.I., Lee S., Park B.W. The impact of caveolin protein expression in tumor stroma on prognosis of breast cancer. Tumour Biol. 2011;32:787–799. doi: 10.1007/s13277-011-0181-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Witkiewicz A.K., Dasgupta A., Nguyen K.H., Liu C., Kovatich A.J., Schwartz G.F., Pestell R.G., Sotgia F., Rui H., Lisanti M.P. Stromal caveolin-1 levels predict early DCIS progression to invasive breast cancer. Cancer Biol Ther. 2009;8:1071–1079. doi: 10.4161/cbt.8.11.8874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Witkiewicz A.K., Dasgupta A., Sammons S., Er O., Potoczek M.B., Guiles F., Sotgia F., Brody J.R., Mitchell E.P., Lisanti M.P. Loss of stromal caveolin-1 expression predicts poor clinical outcome in triple negative and basal-like breast cancers. Cancer Biol Ther. 2010;10:135–143. doi: 10.4161/cbt.10.2.11983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Di Vizio D., Morello M., Sotgia F., Pestell R.G., Freeman M.R., Lisanti M.P. An absence of stromal caveolin-1 is associated with advanced prostate cancer, metastatic disease and epithelial Akt activation. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:2420–2424. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.15.9116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Martinez-Outschoorn U.E., Pavlides S., Whitaker-Menezes D., Daumer K.M., Milliman J.N., Chiavarina B., Migneco G., Witkiewicz A.K., Martinez-Cantarin M.P., Flomenberg N., Howell A., Pestell R.G., Lisanti M.P., Sotgia F. Tumor cells induce the cancer associated fibroblast phenotype via caveolin-1 degradation: implications for breast cancer and DCIS therapy with autophagy inhibitors. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:2423–2433. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.12.12048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chiavarina B., Whitaker-Menezes D., Migneco G., Martinez-Outschoorn U.E., Pavlides S., Howell A., Tanowitz H.B., Casimiro M.C., Wang C., Pestell R.G., Grieshaber P., Caro J., Sotgia F., Lisanti M.P. HIF1-alpha functions as a tumor promoter in cancer associated fibroblasts, and as a tumor suppressor in breast cancer cells: autophagy drives compartment-specific oncogenesis. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:3534–3551. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.17.12908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Martinez-Outschoorn U.E., Whitaker-Menezes D., Lin Z., Flomenberg N., Howell A., Pestell R.G., Lisanti M.P., Sotgia F. Cytokine production and inflammation drive autophagy in the tumor microenvironment: role of stromal caveolin-1 as a key regulator. Cell Cycle. 2011;10:1784–1793. doi: 10.4161/cc.10.11.15674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Witkiewicz A.K., Kline J., Queenan M., Brody J.R., Tsirigos A., Bilal E., Pavlides S., Ertel A., Sotgia F., Lisanti M.P. Molecular profiling of a lethal tumor microenvironment, as defined by stromal caveolin-1 status in breast cancers. Cell Cycle. 2011;10:1794–1809. doi: 10.4161/cc.10.11.15675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pavlides S., Tsirigos A., Vera I., Flomenberg N., Frank P.G., Casimiro M.C., Wang C., Pestell R.G., Martinez-Outschoorn U.E., Howell A., Sotgia F., Lisanti M.P. Transcriptional evidence for the “Reverse Warburg Effect” in human breast cancer tumor stroma and metastasis: similarities with oxidative stress, inflammation, Alzheimer's disease, and “Neuron-Glia Metabolic Coupling.”. Aging (Albany NY) 2010;2:185–199. doi: 10.18632/aging.100134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Razani B., Engelman J.A., Wang X.B., Schubert W., Zhang X.L., Marks C.B., Macaluso F., Russell R.G., Li M., Pestell R.G., Di Vizio D., Hou H., Jr, Kneitz B., Lagaud G., Christ G.J., Edelmann W., Lisanti M.P. Caveolin-1 null mice are viable but show evidence of hyperproliferative and vascular abnormalities. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:38121–38138. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105408200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Namba R., Young L.J., Abbey C.K., Kim L., Damonte P., Borowsky A.D., Qi J., Tepper C.G., MacLeod C.L., Cardiff R.D., Gregg J.P. Rapamycin inhibits growth of premalignant and malignant mammary lesions in a mouse model of ductal carcinoma in situ. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:2613–2621. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mercier I., Casimiro M.C., Zhou J., Wang C., Plymire C., Bryant K.G., Daumer K.M., Sotgia F., Bonuccelli G., Witkiewicz A.K., Lin J., Tran T.H., Milliman J., Frank P.G., Jasmin J.F., Rui H., Pestell R.G., Lisanti M.P. Genetic ablation of caveolin-1 drives estrogen-hypersensitivity and the development of DCIS-like mammary lesions. Am J Pathol. 2009;174:1172–1190. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Williams T.M., Hassan G.S., Li J., Cohen A.W., Medina F., Frank P.G., Pestell R.G., Di Vizio D., Loda M., Lisanti M.P. Caveolin-1 promotes tumor progression in an autochthonous mouse model of prostate cancer: genetic ablation of Cav-1 delays advanced prostate tumor development in tramp mice. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:25134–25145. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501186200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schlegel A., Arvan P., Lisanti M.P. Caveolin-1 binding to endoplasmic reticulum membranes and entry into the regulated secretory pathway are regulated by serine phosphorylation: protein sorting at the level of the endoplasmic reticulum. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:4398–4408. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005448200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Finak G., Bertos N., Pepin F., Sadekova S., Souleimanova M., Zhao H., Chen H., Omeroglu G., Meterissian S., Omeroglu A., Hallett M., Park M. Stromal gene expression predicts clinical outcome in breast cancer. Nat Med. 2008;14:518–527. doi: 10.1038/nm1764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Olewniczak S., Chosia M., Kwas A., Kram A., Domagala W. Angiogenesis and some prognostic parameters of invasive ductal breast carcinoma in women. Pol J Pathol. 2002;53:183–188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sugimoto H., Mundel T.M., Kieran M.W., Kalluri R. Identification of fibroblast heterogeneity in the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Biol Ther. 2006;5:1640–1646. doi: 10.4161/cbt.5.12.3354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lindstrom M.S., Zhang Y. Ribosomal protein S9 is a novel B23/NPM-binding protein required for normal cell proliferation. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:15568–15576. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801151200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Korgaonkar C., Hagen J., Tompkins V., Frazier A.A., Allamargot C., Quelle F.W., Quelle D.E. Nucleophosmin (B23) targets ARF to nucleoli and inhibits its function. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:1258–1271. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.4.1258-1271.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Itahana K., Bhat K.P., Jin A., Itahana Y., Hawke D., Kobayashi R., Zhang Y. Tumor suppressor ARF degrades B23, a nucleolar protein involved in ribosome biogenesis and cell proliferation. Mol Cell. 2003;12:1151–1164. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00431-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hay N., Sonenberg N. Upstream and downstream of mTOR. Genes Dev. 2004;18:1926–1945. doi: 10.1101/gad.1212704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Surowiak P., Suchocki S., Gyorffy B., Gansukh T., Wojnar A., Maciejczyk A., Pudelko M., Zabel M. Stromal myofibroblasts in breast cancer: relations between their occurrence, tumor grade and expression of some tumour markers. Folia Histochem Cytobiol. 2006;44:111–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ostman A., Augsten M. Cancer-associated fibroblasts and tumor growth: bystanders turning into key players. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2009;19:67–73. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Olumi A.F., Grossfeld G.D., Hayward S.W., Carroll P.R., Tlsty T.D., Cunha G.R. Carcinoma-associated fibroblasts direct tumor progression of initiated human prostatic epithelium. Cancer Res. 1999;59:5002–5011. doi: 10.1186/bcr138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hwang R.F., Moore T., Arumugam T., Ramachandran V., Amos K.D., Rivera A., Ji B., Evans D.B., Logsdon C.D. Cancer-associated stromal fibroblasts promote pancreatic tumor progression. Cancer Res. 2008;68:918–926. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Williams T.M., Sotgia F., Lee H., Hassan G., Di Vizio D., Bonuccelli G., Capozza F., Mercier I., Rui H., Pestell R.G., Lisanti M.P. Stromal and epithelial caveolin-1 both confer a protective effect against mammary hyperplasia and tumorigenesis: caveolin-1 antagonizes cyclin D1 function in mammary epithelial cells. Am J Pathol. 2006;169:1784–1801. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.060590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mesker W.E., Liefers G.J., Junggeburt J.M., van Pelt G.W., Alberici P., Kuppen P.J., Miranda N.F., van Leeuwen K.A., Morreau H., Szuhai K., Tollenaar R.A., Tanke H.J. Presence of a high amount of stroma and downregulation of SMAD4 predict for worse survival for stage I-II colon cancer patients. Cell Oncol. 2009;31:169–178. doi: 10.3233/CLO-2009-0478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.de Kruijf E.M., van Nes J.G., van de Velde C.J., Putter H., Smit V.T., Liefers G.J., Kuppen P.J., Tollenaar R.A., Mesker W.E. Tumor-stroma ratio in the primary tumor is a prognostic factor in early breast cancer patients, especially in triple-negative carcinoma patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;125:687–696. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-0855-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Montanaro L., Treŕe D., Derenzini M. Nucleolus, ribosomes, and cancer. Am J Pathol. 2008;173:301–310. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.070752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Thomas G. An encore for ribosome biogenesis in the control of cell proliferation. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:E71–E72. doi: 10.1038/35010581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Carraway H., Hidalgo M. New targets for therapy in breast cancer: mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) antagonists. Breast Cancer Res. 2004;6:219–224. doi: 10.1186/bcr927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ong C.T., Khoo Y.T., Mukhopadhyay A., Do D.V., Lim I.J., Aalami O., Phan T.T. mTOR as a potential therapeutic target for treatment of keloids and excessive scars. Exp Dermatol. 2007;16:394–404. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2007.00550.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mercier I., Casimiro M.C., Wang C., Rosenberg A.L., Quong J., Minkeu A., Allen K.G., Danilo C., Sotgia F., Bonuccelli G., Jasmin J.F., Xu H., Bosco E., Aronow B., Witkiewicz A., Pestell R.G., Knudsen E.S., Lisanti M.P. Human breast cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) show caveolin-1 downregulation and RB tumor suppressor functional inactivation: implications for the response to hormonal therapy. Cancer Biol Ther. 2008;7:1212–1225. doi: 10.4161/cbt.7.8.6220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sotgia F., Del Galdo F., Casimiro M.C., Bonuccelli G., Mercier I., Whitaker-Menezes D., Daumer K.M., Zhou J., Wang C., Katiyar S., Xu H., Bosco E., Quong A.A., Aronow B., Witkiewicz A.K., Minetti C., Frank P.G., Jimenez S.A., Knudsen E.S., Pestell R.G., Lisanti M.P. Caveolin-1-/- null mammary stromal fibroblasts share characteristics with human breast cancer-associated fibroblasts. Am J Pathol. 2009;174:746–761. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Trimboli A.J., Cantemir-Stone C.Z., Li F., Wallace J.A., Merchant A., Creasap N., Thompson J.C., Caserta E., Wang H., Chong J.L., Naidu S., Wei G., Sharma S.M., Stephens J.A., Fernandez S.A., Gurcan M.N., Weinstein M.B., Barsky S.H., Yee L., Rosol T.J., Stromberg P.C., Robinson M.L., Pepin F., Hallett M., Park M., Ostrowski M.C., Leone G. Pten in stromal fibroblasts suppresses mammary epithelial tumours. Nature. 2009;461:1084–1091. doi: 10.1038/nature08486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ellis L.M., Fidler I.J. Angiogenesis and metastasis. Eur J Cancer. 1996;32A:2451–2460. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(96)00389-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Campbell S.C. Advances in angiogenesis research: relevance to urological oncology. J Urol. 1997;158:1663–1674. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(01)64090-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Heimann R., Ferguson D., Powers C., Recant W.M., Weichselbaum R.R., Hellman S. Angiogenesis as a predictor of long-term survival for patients with node-negative breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1996;88:1764–1769. doi: 10.1093/jnci/88.23.1764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]