Abstract

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer deaths worldwide; approximately 85% of these cancers are non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Patients with NSCLC frequently have tumors harboring somatic mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) gene that cause constitutive receptor activation. These patients have the best clinical response to EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs). Herein, we show that fibroblast growth factor–inducible 14 (Fn14; TNFRSF12A) is frequently overexpressed in NSCLC tumors, and Fn14 levels correlate with p-EGFR expression. We also report that NSCLC cell lines that contain EGFR-activating mutations show high levels of Fn14 protein expression. EGFR TKI treatment of EGFR-mutant HCC827 cells decreased Fn14 protein levels, whereas EGF stimulation of EGFR wild-type A549 cells transiently increased Fn14 expression. Furthermore, Fn14 is highly expressed in EGFR-mutant H1975 cells that also contain an EGFR TKI-resistance mutation, and high TKI doses are necessary to reduce Fn14 levels. Constructs encoding EGFRs with activating mutations induced Fn14 expression when expressed in rat lung epithelial cells. We also report that short hairpin RNA–mediated Fn14 knockdown reduced NSCLC cell migration and invasion in vitro. Finally, Fn14 overexpression enhanced NSCLC cell migration and invasion in vitro and increased experimental lung metastases in vivo. Thus, Fn14 may be a novel therapeutic target for patients with NSCLC, in particular for those with EGFR-driven tumors who have either primary or acquired resistance to EGFR TKIs.

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer deaths worldwide. In the United States alone, there were 222,520 new cases and 157,300 deaths in 2010.1 Of lung cancers, 85% are classified as non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), which is further divided into adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and large-cell carcinoma. More recently, molecular subsets of adenocarcinomas have been identified, with specific genomic alterations initiating and maintaining the malignancy. One such genomic alteration is the overexpression and/or mutation of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR).

EGFR is overexpressed in 40% to 80% of patients with NSCLC and is correlated with disease progression and overall poor survival.2,3 Thus, EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), such as gefitinib and erlotinib, became promising therapies for patients with NSCLC. The clinical response rates for these drugs were unexpectedly low (<10% as single agents) and prompted investigation into patient subgroups that might benefit from EGFR-targeted drugs.4–6 Two seminal studies described mutations in the EGFR gene that correlated to clinical response to gefitinib.7,8 Patients with EGFR mutations were more sensitive to gefitinib and showed improved progression-free survival. Approximately 10% to 15% of the patients with NSCLC in the Western hemisphere and 30% to 50% of patients of Asian ethnicity have tumors harboring somatic mutations in the EGFR that cause constitutive activation of this receptor.6,9 Despite the success of TKIs in patients with lung tumors harboring EGFR-activating mutations, many patients develop resistance to gefitinib and erlotinib and show disease progression. Mechanisms of acquired resistance to EGFR TKI therapy, such as the secondary mutation in exon 20 (T790M),10 or amplification of other growth factor receptors, such as c-Met,11–13 have been described. In addition, K-ras mutations, which occur in 15% to 20% of NSCLCs,14 have been described as a resistance mechanism to EGFR-directed therapy in NSCLC and colon cancer.15 Thus, the molecular mechanisms that govern the progression of these lung tumors with EGFR mutations and resistance to anti-EGFR therapies remain to be elucidated.

Fibroblast growth factor–inducible 14 (Fn14; gene TNFRSF12A) is the smallest known member of the tumor necrosis factor superfamily of receptors, and its only known ligand is the multifunctional cytokine tumor necrosis factor–like weak inducer of apoptosis (TWEAK).16 The TWEAK/Fn14 signaling axis has been implicated in tumor growth and metastasis. Increased expression of Fn14 has been observed in several solid tumors, including hepatocellular carcinoma,17 glioblastoma,18,19 esophageal adenocarcinoma,20,21 and HER2+ breast cancer.22,23 In glioblastoma, Fn14 signaling modulates cell survival through regulation of NF-κB, Bcl-XL, Bcl-2 expression, and Akt2 activation.24,25 Fn14 signaling also promotes glioma and breast cell invasion through activation of Rac1 and NF-κB.19,22 Fn14 expression has been detected in NSCLC specimens,26 but little is known about the role of Fn14 in this tumor type.

In this study, we show that Fn14 is frequently highly expressed in NSCLCs and that, in NSCLC cell lines, Fn14 expression often occurs concurrently with activating EGFR mutations. We further show that Fn14 expression is induced by EGF and repressed by erlotinib, implicating the importance of EGFR signaling in regulating Fn14 expression. In an NSCLC cell line that is resistant to erlotinib because of an EGFR T790M mutation, Fn14 expression remains elevated unless a relatively high EGFR TKI dose is used. We also demonstrate that the expression of Fn14 modulates cell migration and invasion in NSCLC cells in vitro and that ectopic expression of Fn14 augments NSCLC tumor formation in an experimental metastasis assay. Together, these data suggest that Fn14 signaling contributes to NSCLC cell motility and invasion and that Fn14 may be a new potential target for NSCLC treatment.

Materials and Methods

Tumor TMA

Lung cancer samples were obtained from patients who underwent total tumor resection. Specimen blocks chosen for the TMA met the criteria of nonnecrotic, nonirradiated, or chemo-treated lung cancer tissue. NSCLC subtypes included adenocarcinoma (n = 179) and squamous cell carcinoma (n = 111). Samples were double punched (0.6 μm diameter) using an indexed manual arrayer with an attached stereomicroscope under the direction of one of the authors (G.H.), who also reviewed and verified the tumor content. IHC analysis for Fn14 was performed using the Fn14 monoclonal antibody P4A8 (Biogen Idec, Inc., Weston, MA), as previously described.19 p-EGFR analysis was performed using an antibody specific for EGFR-Y1068 (Cell Signaling Technologies, Beverly, CA). A scoring system for each chromophore, composed of staining intensity and extensiveness, captured the outcome: 0, negative; 1, weak; 2 moderate; and 3, strong.

Cell Culture

Human NSCLC cell lines H520, H2122, A549, H1703, H358, H3255, H1975, HCC2279, and HCC827 (ATCC, Manassas, VA) were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) in a 37°C, 5% CO2 atmosphere. For the EGF stimulation and erlotinib treatment experiments, cells were placed in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 0.5% FBS for 18 hours before growth factor or drug addition.

Reagents, Antibodies, and Immunoblot Analysis

Erlotinib was obtained from BioVision (Mountain View, CA). EGF was obtained from Millipore (Billerica, MA) or R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). Polyclonal Fn14 antibodies were either generated by us27 or obtained from Cell Signaling Technologies. Antibodies specific to p-EGFR (Y-1068), total EGFR, EGFR L858R mutant, and the EGFR E746-A750 deletion mutant were obtained from Cell Signaling Technologies. The α-tubulin antibody was obtained from Millipore or eBioscience (San Diego, CA), and the glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) and hemagglutinin epitope antibodies were obtained from Cell Signaling Technologies. Immunoblot analysis was performed as previously described.25

Expression of EGFR Variants and K-ras V12 in Immortalized Rat Bronchiolar Epithelial Cells

The rat bronchiolar epithelial cell line RL-65 (ATCC) was grown and maintained as previously described.28 The pBABE retroviral constructs of wild-type EGFR (Addgene 11011) and EGFR mutants (L858R-11012, L747-E749 del-11015, D770-N771 ins-11016, and D837-11014) were obtained from Addgene (Cambridge, MA) and were previously described.29 The K-ras V12 pBABE construct (9052) and the empty pBABE vector (1764) were also obtained from Addgene.org. Replication-incompetent retroviruses were produced from the EGFR constructs by transfection into the Phoenix 293T packaging cell line (Allele Biotech, San Diego, CA) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). RL-65 cells were infected with these retroviruses in the presence of 5 g/mL polybrene. At 24 hours after infection, 2 g/mL puromycin was added to media, and cells were maintained for 5 days before lysis and immunoblotting for Fn14, p-EGFR, EGFR, and GAPDH.

Lentiviral Constructs and Transduction

Lentiviral constructs (pGIPZ) containing nonsilencing short hairpin RNA (shRNA) or shRNAs targeting two different regions of the Fn14 transcript (Fn14shRNA154, clone ID V3LHS_380154; Fn14shRNA156, clone ID V3LHS_380156) were obtained from Open Biosystems (Huntsville, AL). To generate the Fn14 overexpression construct, the coding sequence for Fn14 was amplified by PCR and ligated in-frame upstream of a 3XHA epitope in pcDNA3. For stable transduction, the HA epitope–tagged Fn14 fragment was excised from pcDNA3 and ligated into the lentiviral transfer vector pCDH (System Biosciences, Mountain View, CA) that contains a second transcriptional cassette for the expression of green fluorescent protein (GFP). An empty pCDH vector expressing only GFP or a nonsilencing shRNAmir vector expressing GFP was used as a control in an overexpression or knockdown experiment, respectively. Vesicular stomatitis virus-G-pseudotyped recombinant lentiviruses encoding Fn14 were produced by cotransfection of 293 packaging cells with the pCDH-Fn14 HA construct and the pPACK packaging mix (System Biosciences), according to the manufacturer's directions. Pseudotyped lentiviruses encoding shRNAs were produced by cotransfection of packaging cells with the appropriate shRNA construct and the Trans-Lentiviral Packaging Extract (Open Biosystems), according to the manufacturer's protocol. For lentiviral transduction, medium containing recombinant lentiviruses was harvested from the packaging cells at 48 hours after transfection, concentrated by polyethylene glycol precipitation and centrifugation, and added to subconfluent cultures of cells together with 8 μg/mL polybrene. Positively transduced cells were enriched by mass sorting the GFP-positive cells on a Vantage flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA).

Migration and Invasion

Migration was assessed using a 25 × 80-mm polycarbonate membrane (8 μmol/L pore) and 12-well Chemotaxis Chamber (Neuro Probe Inc., Gaithersburg, MD). Cells (5 × 104) were seeded into each of 12 wells and allowed to migrate through the membrane for 5 hours. Cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium (Invitrogen) without FBS throughout the experiment. For EGF-induced migration, EGF (50 ng/mL) was placed in the bottom chamber. All treatments were performed in triplicate. Stationary cells were removed from the top of the membrane by scraping, and the membrane was fixed in 70% methanol. The membrane was stained with DAPI and mounted on a glass slide. Cells were counted from five random fields using fluorescent microscopy.

For the invasion assays, 1 × 105 cells suspended in RPMI 1640 medium with 0.5% serum were seeded into growth factor–reduced Matrigel invasion chambers (BD Biosciences). Chambers were placed in a 24-well plate containing RPMI 1640 medium and 10% FBS. Cells were allowed to invade through the membrane for 20 hours. For EGF-induced invasion, the bottom chamber contained RPMI 1640 medium with 0.5% serum and 50 ng/mL EGF. All treatments were performed in triplicate. Cells were fixed and stained in 0.1% crystal violet in 20% methanol. Stationary cells were removed from the top of the membrane by scraping, and the membrane was mounted on a glass slide. Cells were counted from six random fields using light microscopy.

Tail Vein Injection of A549 Cells

A549 lung adenocarcinoma cells (5 × 105) stably infected with either lentiviral vector or human Fn14 with an HA epitope tag (hFn14-HA) lentivirus (n = 9 per group) were injected i.v. (tail vein) into beige mice with severe combined immunodeficiency (Taconic, Hudson, NY), as previously described.30 Six weeks after injection, mice were sacrificed and lungs were fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin. Lungs were evaluated for metastatic surface nodules by gross visualization. Tumor lesions were counted in a blinded manner using a dissecting microscope. Tissue was then embedded in paraffin and divided into sections (4 μm thick). Sections were stained with H&E using standard procedures, and immunohistochemical (IHC) staining was performed using an anti-HA antibody (Cell Signaling Technologies).

Statistics

For TMA, tests for correlation using the rank-based Kendall's τ statistic were calculated using the cor. test function in the R statistical package (http://www.r-project.org, last accessed February 11, 2011). Migration and invasion assay results were assessed using the two-sample Student's t-test. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Fn14 Is Overexpressed in Primary Human NSCLC Tumors, and High Fn14 Levels Correlate with EGFR Phosphorylation

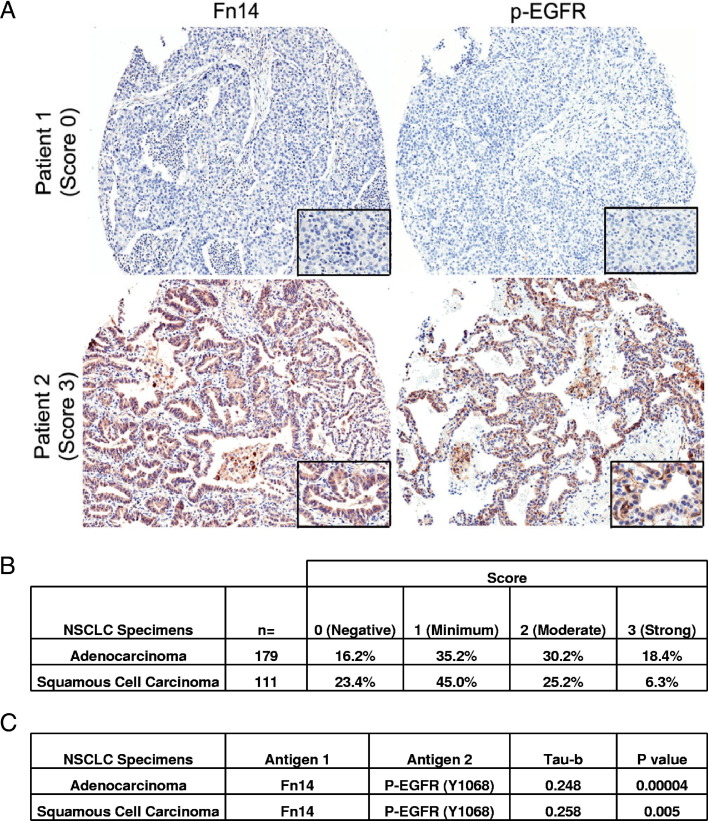

We examined, by IHC staining of a lung TMA, whether Fn14 was expressed in primary human NSCLC tumors and, if so, whether those tumors with elevated Fn14 expression had activated EGFR, as assessed by staining with a p-EGFR (Y-1068) antibody. Representative staining patterns of an Fn14-negative/p-EGFR–negative patient and an Fn14-positive/p-EGFR–positive patient are shown in Figure 1A. Fn14 showed moderate to strong staining (scores 2 and 3) in 48.6% of adenocarcinoma specimens and 31.5% of squamous cell carcinoma specimens (Figure 1B). To determine whether Fn14 protein staining correlated with activated EGFR expression, tumors were scored for both Fn14 and p-EGFR protein staining. There was a statistically significant positive correlation (P < 0.01) between Fn14 and p-EGFR expression in both adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma subtypes, as determined by the Kendall's τ rank correlation test (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

Fn14 expression in human NSCLC specimens and correlation with EGFR phosphorylation. A: Fn14 and p-EGFR staining on representative samples from two patients with lung adenocarcinoma (×5 objective, Aperio GL Scanner; Aperio, Vista, CA). Insets: ×40 objective. Tumor cell–specific Fn14 and p-EGFR staining in each of the tumor punches was scored by a board-certified pathologist; a score of 0 indicates a staining level equal to adjacent nontumor cells. A non-0 score indicates increased staining (1, minimum; 2, moderate; 3, strong positive). B: The percentage distribution of staining intensity of Fn14 in NSCLC patient specimens. C: A total of 290 samples were scored for Fn14 and p-EGFR expression, and the correlation between the two stains was analyzed using Kendall's τ rank correlation test.

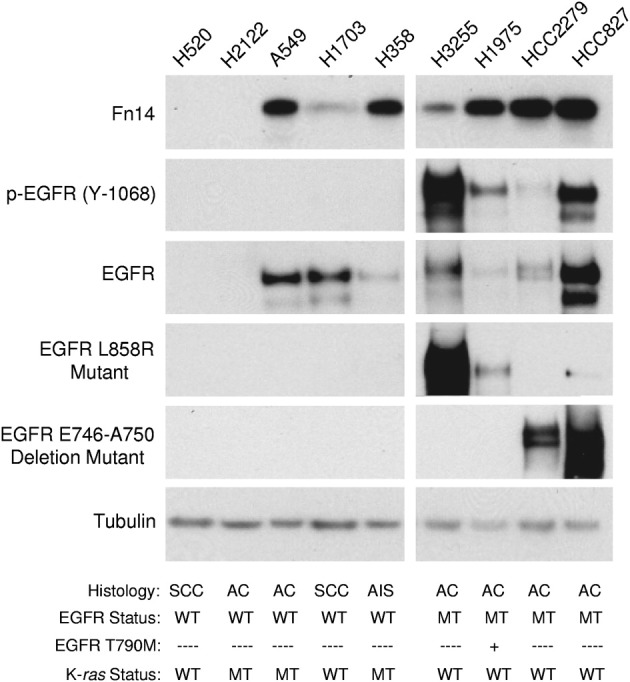

Fn14 Is Highly Expressed in EGFR- or K-ras–Mutated NSCLC Cell Lines

We assessed the protein expression of Fn14 across nine NSCLC cell lines by immunoblot analysis. Fn14 expression was detected in five of six cell lines classified as adenocarcinoma, and in an adenocarcinoma in situ cell line, but expression was much lower in the two squamous cell carcinoma cell lines (Figure 2). Relatively high levels of Fn14 often coincided with p-EGFR expression (Y-1068), driven by activating EGFR mutations (L858R and ΔE746-A750), including the H1975 cell line, which also contained a secondary mutation (T790M) known to confer resistance to EGFR TKIs. In addition, Fn14 protein was also highly expressed in two of the three cell lines (A549 and H358) with activating K-ras mutations.

Figure 2.

Fn14 expression levels in various NSCLC cell lines. Total cell lysates were prepared from various NSCLC cell lines [squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), adenocarcinoma (AC), and adenocarcinoma in situ (AIS)] and immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies: Fn14, p-EGFR (Y-1068), EGFR, EGFR L858R mutant, or EGFR E746-A750 deletion mutant. Tubulin was used as a loading control. MT, mutant; WT, wild type.

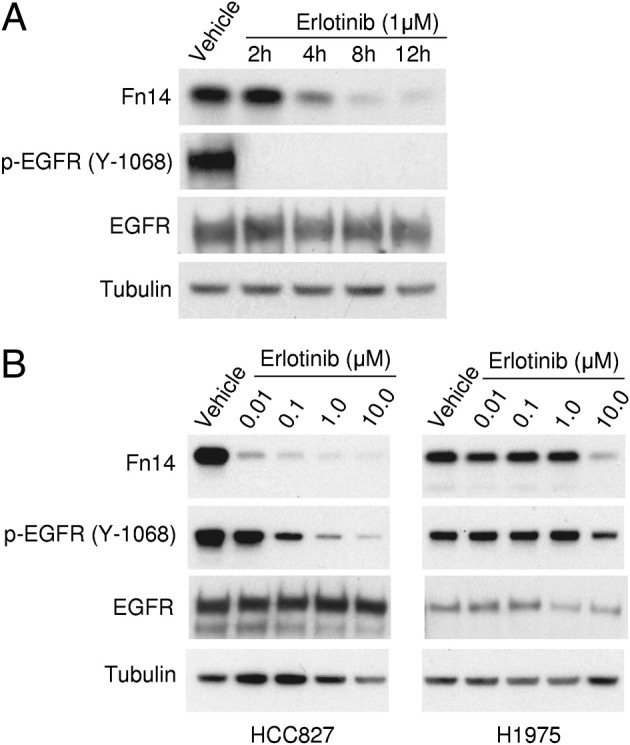

Erlotinib Suppresses Fn14 Expression

To assess whether constitutive EGFR signaling was directly triggering Fn14 expression, we used the small-molecule EGFR kinase inhibitor, erlotinib. Treatment of HCC827 cells with 1 μmol/L erlotinib inhibited EGFR activation, as detected by decreased p-EGFR protein expression (Figure 3A). In addition, erlotinib treatment decreased the level of Fn14 protein expression in a time-dependent (Figure 3A) and dose-dependent (Figure 3B) manner. Erlotinib treatment also decreased Fn14 expression in two other cell lines with activating EGFR mutations: H3255 and HCC2279 (data not shown). Treatment of the H1975 NSCLC cell line, which contains both an EGFR-activating mutation and an EGFR-TKI resistance mutation, required a 1000-fold higher erlotinib dose to decrease p-EGFR and Fn14 levels compared with HCC827 cells (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Erlotinib treatment of TKI-sensitive NSCLC cells decreases Fn14 expression. A: Serum-starved HCC827 cells containing the EGFR E746-A750–activating mutation were treated with vehicle for 12 hours or 1 μmol/L erlotinib for the indicated time periods. Cells were harvested, and total cell lysates were prepared and immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies to Fn14, p-EGFR, or total EGFR. Tubulin was used as a loading control. B: HCC827 cells containing the EGFR E746-A750–activating mutation and H1975 cells containing the EGFR L858R-activating mutation and the EGFR T790M drug-resistance mutation were serum starved and then treated with vehicle or the indicated concentration of erlotinib for 8 hours. Immunoblotting was conducted as described for A.

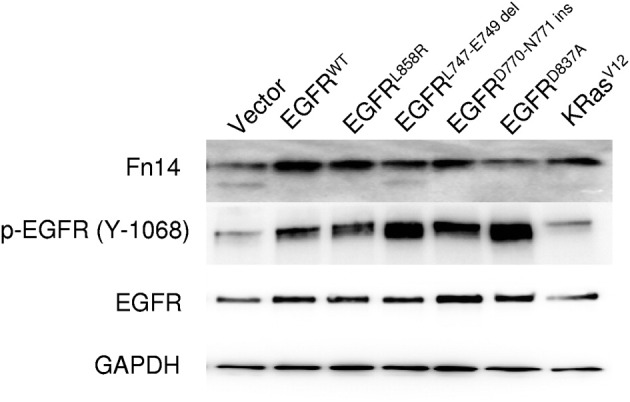

Activating EGFR Mutations Increase Fn14 Expression in Lung Epithelial Cells

To further investigate the relationship between activated EGFR and Fn14 expression, we expressed both activating and nonactivating EGFR constructs in a nontransformed, immortalized rat lung epithelial cell line (RL-65). Expression of wild-type EGFR and mutant EGFR receptors increased p-EGFR levels compared with vector control or mutant K-ras retrovirus-infected cells (Figure 4). It is likely that phosphorylation of the kinase-dead EGFR mutant (D837A) occurred either via homodimerization with endogenous EGFR or by the activity of other tyrosine kinases in the RL-65 cells. Fn14 protein expression was induced in both the wild-type and activating EGFR mutation cells; in contrast, expression of the kinase-dead EGFR mutant failed to enhance Fn14 expression. Notably, expression of a K-ras mutant (V12) in RL-65 cells also resulted in increased Fn14 expression.

Figure 4.

Ectopic expression of wild-type (WT) EGFR, activated EGFR mutants, and the K-rasV12 mutant in rat lung epithelial cells (RL-65) induces Fn14 expression. Total cellular lysates from RL-65 cells stably expressing the indicated EGFR receptors or K-rasV12 were prepared and analyzed by immunoblotting for Fn14, p-EGFR, and total EGFR. GAPDH was used as a loading control.

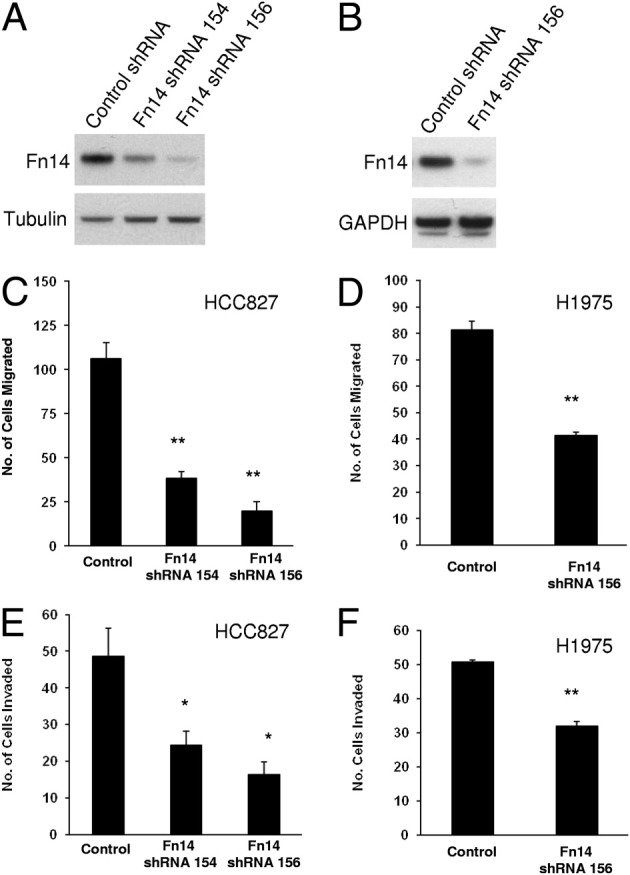

Fn14 Depletion Reduces NSCLC Cell Migration and Invasive Capacity in Vitro

We next investigated whether depletion of Fn14 expression by shRNA could suppress NSCLC cell migration and invasion. Cells stably expressing Fn14 shRNA 154 or 156, targeting the Fn14 transcript, showed a suppression of Fn14 levels in both HCC827 (Figure 5A) and H1975 (Figure 5B) cells. These cell lines were less migratory and invasive compared with control cells. Specifically, the knockdown of Fn14 by shRNA suppressed NSCLC cell migration by 64% (shRNA 154) or 81% (shRNA 156) in HCC827 cells and 50% (shRNA 156) in H1975 cells (Figure 5, C and D). The depletion of Fn14 by shRNA suppressed cell invasion by 50% (shRNA 154) or 66% (shRNA 156) in HCC827 cells and 37% (shRNA 156) in H1975 cells (Figure 5, E and F).

Figure 5.

Depletion of Fn14 expression by shRNA reduces NSCLC cell migration and invasion. A: HCC827 cells were infected with lentiviruses expressing two different Fn14 shRNAs or control nontargeting shRNA. Stable cell lines were isolated, cell lysates were prepared, and immunoblotting was conducted using the indicated antibodies to Fn14 or tubulin (loading control). B: H1975 cells were infected with lentivirus expressing the most effective Fn14 shRNA or control nontargeting shRNA. Stable cell lines were isolated, cell lysates were prepared, and immunoblotting was conducted using antibodies to Fn14 or GAPDH (loading control). C: Transwell migration assay of HCC827 cell lines expressing control shRNA or Fn14 shRNAs. D: Transwell migration assay of H1975 cell lines expressing control shRNA or Fn14 shRNA. E: Matrigel invasion assay of HCC827 cell lines expressing control shRNA or Fn14 shRNAs. F: Matrigel invasion assay of H1975 cell lines expressing control shRNA or Fn14 shRNA. For migration and invasion assays, the values shown are the mean ± SEM of triplicate chambers. Significance was assessed by the Student's t-test. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

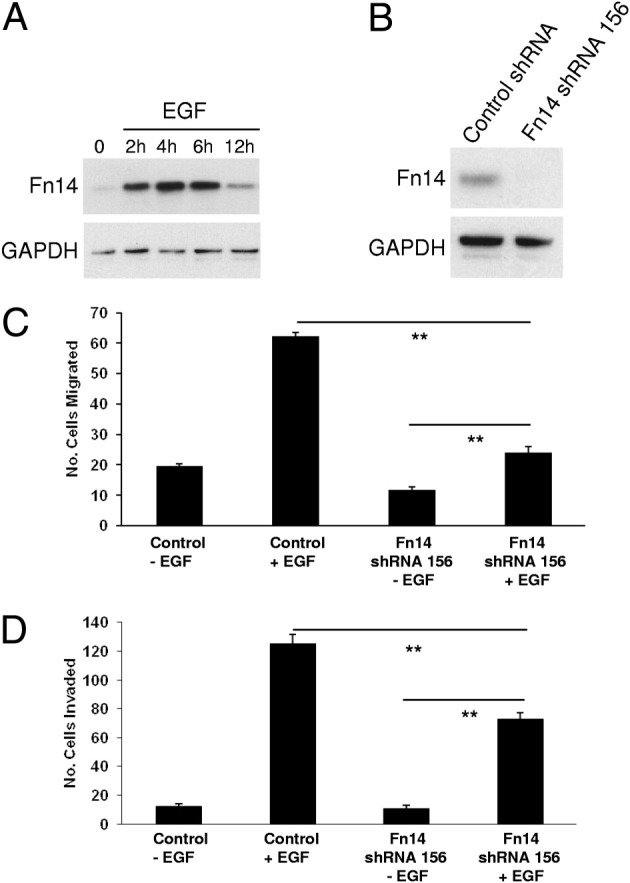

Fn14 Depletion Attenuates EGF-Induced NSCLC Cell Migration and Invasion in Vitro

Because Fn14 expression was modulated by EGFR signaling, and Fn14 influenced baseline NSCLC cell migration and invasion, we tested whether Fn14 depletion also reduced EGF-driven cell migration and invasion. We found that EGF treatment of A549 cells increased Fn14 protein expression, with maximal induction at 4 hours (Figure 6A). Next, we generated an Fn14-deficient A549 cell line using shRNA lentiviral infection, and cells infected with the shRNA 156 virus expressed low levels of Fn14 (Figure 6B). Although EGF treatment enhanced A549-control shRNA cell migration by approximately threefold, EGF treatment of the A549 Fn14 shRNA cells increased migration by only approximately twofold (Figure 6C). Similarly, EGF treatment also increased A549-control shRNA cell invasion by approximately 10-fold, whereas the knockdown of Fn14 suppressed EGF-driven cell invasion by 30% compared with A549-control shRNA cells (Figure 6D).

Figure 6.

Depletion of Fn14 reduces EGF-stimulated NSCLC cell migration and invasion. A: Serum-starved A549 cells were treated with 50 ng/mL EGF for the indicated times. Cells were harvested, and total cell lysates were prepared and immunoblotted with an antibody against Fn14. GAPDH was used as a loading control. B: A549 cells were infected with lentivirus expressing an Fn14 shRNA (156) or control nontargeting shRNA. Stable cell lines were isolated, cell lysates were prepared, and immunoblotting was conducted using the indicated antibodies against Fn14 and GAPDH (loading control). C: Transwell migration assay of A549 cells expressing control or Fn14 shRNA and either left untreated or treated with 50 ng/mL EGF. D: Matrigel invasion assay of A549 cells expressing control or Fn14 shRNA and either left untreated or treated with 50 ng/mL EGF. For migration and invasion assays, the values shown are the mean ± SEM of triplicate chambers. Significance was assessed by the Student's t-test. **P < 0.01.

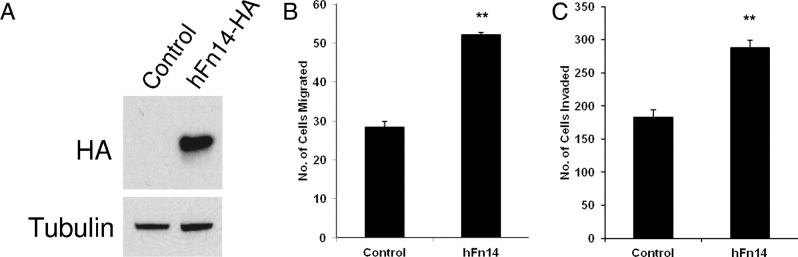

Fn14 Overexpression Enhances NSCLC Cell Motility and Invasion in Vitro

We next investigated whether Fn14 overexpression would modulate NSCLC cell motility and invasion. We infected A549 cells with control lentivirus or lentivirus encoding full-length, hFn14-HA, and stable cell lines were isolated. Fn14-HA expression in the A549 cell line was confirmed by immunoblotting (Figure 7A). Compared with the vector-infected A549 cells (control), ectopic expression of Fn14 enhanced cell migration approximately twofold (Figure 7B). The expression of Fn14 also enhanced A549 cell invasion by approximately 1.6-fold (Figure 7C).

Figure 7.

Fn14 overexpression enhances NSCLC cell migration and invasion in vitro. A: A549 cells were infected with lentivirus expressing full-length hFn14-HA or vector alone (control). Stable cell lines were isolated, cell lysates were prepared, and immunoblotting was conducted using antibodies against HA and tubulin (loading control). B: Transwell migration assay of control and Fn14-overexpressing A549 cells. C: Matrigel invasion assay of control and Fn14-overexpressing A549 cells. For migration and invasion assays, the values shown are the mean ± SEM of triplicate chambers. Significance was assessed by the Student's t-test. **P < 0.01.

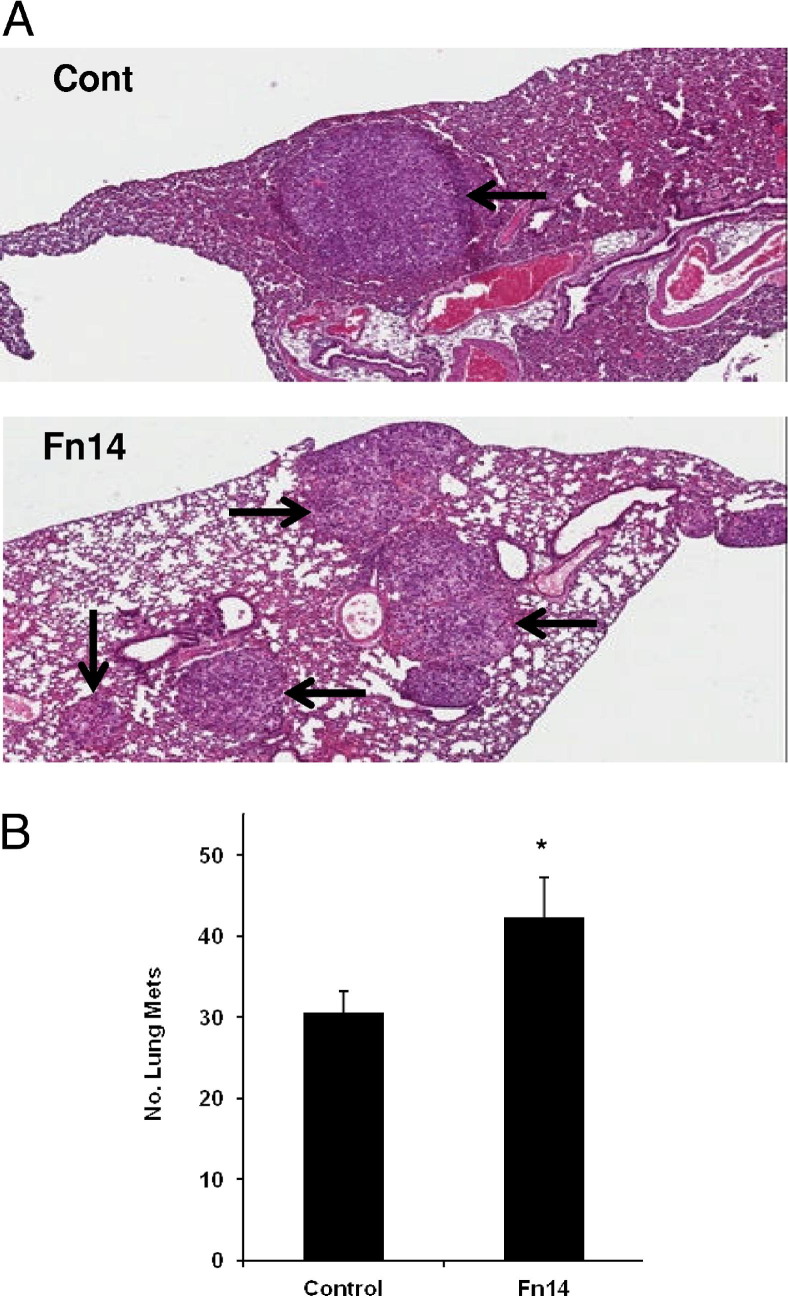

Fn14 Overexpression Enhances Experimental Metastasis in Vivo

Because our in vitro data indicated involvement of Fn14 in migration and invasion of NSCLC cells, we next tested whether overexpression of Fn14 could enhance NSCLC tumor formation in an in vivo model of experimental metastasis. Control or hFn14-HA–overexpressing A549 cells were injected into the tail vein of Beige mice with severe combined immunodeficiency. Mice were evaluated grossly for lung tumors 6 weeks after injection. H&E staining of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded sections confirmed the presence of lung tumors (Figure 8A). The number of gross lung tumors was 40% higher in mice injected with A549-hFn14-HA cells compared with A549 control cells (Figure 8B).

Figure 8.

Fn14 overexpression in NSCLC cells enhances experimental metastases in vivo. A: H&E-stained lung sections from Beige mice with severe combined immunodeficiency, injected i.v. with either control A549 or Fn14-overexpressing A549 cells. Arrows indicate tumors. B: Average number of experimental metastases in lung tumors from mice injected with control A549 or Fn14-overexpressing A549 cells (n = 9 per group). The values shown are the mean ± SEM. Significance was assessed by the Student's t-test. *P < 0.05.

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrate that Fn14 was highly expressed in human NSCLCs and correlates with the expression of phosphorylated EGFR. We also show that activation of EGFR signaling, either through EGF:EGFR binding or mutations in the EGFR kinase domain, enhance Fn14 protein expression, and that pharmacological inhibition of EGFR signaling decreases Fn14 expression. In NSCLC cells harboring an EGFR-activating mutation and the T790M EGFR mutation that reduces EGFR TKI sensitivity, Fn14 levels are elevated and only decrease after exposure to a high EGFR TKI dose. We further demonstrate that Fn14 expression levels could modulate NSCLC cell migration and invasion in vitro and experimental lung metastasis in vivo.

The Fn14 protein is highly expressed in primary human NSCLC tumors. This follows reports showing that Fn14 expression is enhanced in several human malignancies,16,26 including glioblastoma,18,19 esophageal adenocarcinoma,20,21 hepatocellular carcinoma,17 and HER2+ breast cancer.22,23 The ErbB family (ErbB1/EGFR, ErbB2/HER2, ErbB3, and ErbB4) of transmembrane proteins, especially EGFR, has been firmly established as important drivers and therapeutic targets in solid tumors.31–33 Overexpression of EGFR and ErbB2 is observed in NSCLC and confers poor prognosis and chemoresistance.34 EGFR activation is achieved through ligand binding, receptor overexpression, or receptor mutation. EGF and many other growth factors and cytokines, including fibroblast growth factors 1 and 2, platelet-derived growth factor-BB, transforming growth factor-β1, and TWEAK, can induce Fn14 gene expression.16,19,27 Thus, we determined whether Fn14 was preferentially overexpressed in NSCLC primary tumors with activated EGFR. In both adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma subtypes, Fn14 expression was significantly correlated with tyrosine phosphorylated EGFR, a marker of EGFR activation. Fn14 is also highly expressed in HER2+ breast tumors.22 The observed association between Fn14 expression and ErbB family member activation suggests that therapeutic targeting of Fn14 in tumors driven by oncogenic ErbB family members could benefit patients.

Along with receptor overexpression and EGF:EGFR engagement, activation of EGFR can occur via mutations in the EGFR kinase domain. EGFR-TK mutations occur in 10% to 15% of patients with NSCLC in the Western hemisphere and in 30% to 50% of patients of Asian ethnicity.6,7 In this study, we demonstrate that NSCLC cell lines harboring EGFRs with activating mutations have increased Fn14 expression. We further show that expressing EGFRs with TK domain mutations in immortalized rat lung epithelial cells increased Fn14 expression. We found that erlotinib exposure inhibited p-EGFR levels in three NSCLC cell lines harboring EGFR-activating mutations, with a concomitant reduction in Fn14. Although patients with activating EGFR mutations initially respond to EGFR-TKIs, subsequent resistance and relapse are common. Mechanisms of resistance include secondary mutations in EGFR10,35 and amplification of other growth factor receptors, such as c-Met.11–13 We also showed that H1975 NSCLC cells harboring an activating EGFR mutation and the T790M EGFR mutation, which reduces sensitivity to EGFR-TKIs, sustain Fn14 protein expression after exposure to erlotinib, except at high erlotinib concentrations. Thus, targeting of Fn14 may be an attractive approach to treat patients with NSCLC who are resistant to EGFR-TKI therapy.

EGF, through binding and activation of EGFR, is a well-characterized inducer of cell migration and is frequently used to stimulate lung cancer cell migration in vitro.36–38 Herein, we showed that Fn14 depletion through RNA interference reduced NSCLC cell migration and invasion driven by EGF:EGFR binding or by activating mutations in EGFR. The suppression of Fn14 does not completely abrogate EGF-induced lung cell migration or invasion, indicating that other motility mechanisms are still active in these cells. We also demonstrated that overexpression of Fn14 enhanced NSCLC cell migration and invasion in vitro and enhanced experimental lung metastasis in vivo. Thus, our data suggest that Fn14 levels can modulate NSCLC cell migration and invasion. This supports growing evidence that Fn14 is involved in control of motility and the invasive properties of cancer cells. For example, Watts and colleagues20 reported that modulation of Fn14 expression affected the invasiveness of esophageal adenocarcinoma cell lines. Also, overexpression of Fn14 induced an invasive phenotype in prostate cancer cell lines.39 In breast cancer cell lines, the ectopic expression of Fn14 enhanced invasion, whereas suppression of Fn14 through RNAi reduced breast cancer cell invasion.22 Our laboratory has previously demonstrated that Fn14 is expressed at high levels in invading glioma cells in vivo and that ectopic expression of Fn14 stimulated glioma cell invasion and migration through an Rac1-dependent mechanism in vitro.18,19 We have also demonstrated that TWEAK, the ligand for Fn14, stimulated matrix metalloproteinase 9 expression, a mediator of invasive activity, in glioma cells.40 Investigation on the mechanism(s) by which Fn14 enhances invasive phenotypes in NSCLC cells and other tumor cell lines is ongoing.

Fn14 gene expression is often elevated in many diverse types of tumors compared with the corresponding normal tissues,16,26 suggesting that Fn14 may be a therapeutic target for cancer therapy. In fact, Zhou and colleagues41 described an Fn14 monoclonal antibody with recombinant gelonin chemical conjugate, that suppressed the growth of several cancer cell lines in vitro and inhibited tumor growth in an in vivo model of bladder cancer. In some cases, administration of anti-Fn14 monoclonal antibodies alone can inhibit tumor growth in xenograft assays.26,42 Thus, tumor suppression through the targeting of Fn14 may prove to be a therapeutic intervention in NSCLC and other tumor types.

In conclusion, Fn14 is highly expressed in primary human NSCLCs and correlated with activation of EGFR. Consistent with this observation, most NSCLC cell lines with activating EGFR mutations express high levels of Fn14. Suppression of Fn14 reduced NSCLC migration and invasion in vitro, whereas the overexpression of Fn14 enhanced migration and invasion in vitro and experimental metastasis in vivo. Thus, Fn14 may be a therapeutic target for patients with NSCLC, in particular for those with EGFR-driven tumors who have either primary or acquired resistance to EGFR TKIs.

Acknowledgments

We thank Serdar Tuncali and Allison Cheng for technical assistance, Dr. Jennifer Michaelson (Biogen Idec, Inc.) for providing the Fn14 monoclonal antibody, and the Collaborative Bioinformatics Center at the Translational Genomics Research Institute for their efforts in statistical analysis.

Footnotes

This work was supported in part by NIH grants R01 NS055126 (J.A.W), R01 CA130940 (N.L.T.), R01 CA103956 (J.C.L.); by the Translational Genomics Research Institute Foundation and Scottsdale Healthcare Foundation (G.J.W.), St. Joseph's Foundation (Phoenix, AZ) for the Heart and Lung Institute Research Initiative (L.J.I. and R.M.B.), and T32 HL007698 (University of Maryland School of Medicine to E.C.).

N.L.T. and J.A.W. contributed equally to this work.

CME Disclosure: The authors of this article and the planning committee members and staff have no relevant financial relationships with commercial interest to disclose.

Contributor Information

Nhan L. Tran, Email: ntran@tgen.org.

Jeffrey A. Winkles, Email: jwinkles@som.umaryland.edu.

References

- 1.Jemal A., Siegel R., Xu J., Ward E. Cancer statistics, 2010. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;60:277–300. doi: 10.3322/caac.20073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.da Cunha Santos G., Shepherd F.A., Tsao M.S. EGFR mutations and lung cancer. Annu Rev Pathol. 2011;6:49–69. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-011110-130206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sharma S.V., Bell D.W., Settleman J., Haber D.A. Epidermal growth factor receptor mutations in lung cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:169–181. doi: 10.1038/nrc2088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gazdar A.F. Epidermal growth factor receptor inhibition in lung cancer: the evolving role of individualized therapy. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2010;29:37–48. doi: 10.1007/s10555-010-9201-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pao W., Chmielecki J. Rational, biologically based treatment of EGFR-mutant non-small-cell lung cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10:760–774. doi: 10.1038/nrc2947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sequist L.V., Bell D.W., Lynch T.J., Haber D.A. Molecular predictors of response to epidermal growth factor receptor antagonists in non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:587–595. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.3585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maemondo M., Inoue A., Kobayashi K., Sugawara S., Oizumi S., Isobe H., Gemma A., Harada M., Yoshizawa H., Kinoshita I., Fujita Y., Okinaga S., Hirano H., Yoshimori K., Harada T., Ogura T., Ando M., Miyazawa H., Tanaka T., Saijo Y., Hagiwara K., Morita S., Nukiwa T., North-East Japan Study Group Gefitinib or chemotherapy for non-small-cell lung cancer with mutated EGFR. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:2380–2388. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0909530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paez J.G., Janne P.A., Lee J.C., Tracy S., Greulich H., Gabriel S., Herman P., Kaye F.J., Lindeman N., Boggon T.J., Naoki K., Sasaki H., Fujii Y., Eck M.J., Sellers W.R., Johnson B.E., Meyerson M. EGFR mutations in lung cancer: correlation with clinical response to gefitinib therapy. Science. 2004;304:1497–1500. doi: 10.1126/science.1099314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shigematsu H., Lin L., Takahashi T., Nomura M., Suzuki M., Wistuba I.I., Fong K.M., Lee H., Toyooka S., Shimizu N., Fujisawa T., Feng Z., Roth J.A., Herz J., Minna J.D., Gazdar A.F. Clinical and biological features associated with epidermal growth factor receptor gene mutations in lung cancers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:339–346. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pao W., Miller V.A., Politi K.A., Riely G.J., Somwar R., Zakowski M.F., Kris M.G., Varmus H. Acquired resistance of lung adenocarcinomas to gefitinib or erlotinib is associated with a second mutation in the EGFR kinase domain. PLoS Med. 2005;2:e73. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bean J., Brennan C., Shih J.Y., Riely G., Viale A., Wang L., Chitale D., Motoi N., Szoke J., Broderick S., Balak M., Chang W.C., Yu C.J., Gazdar A., Pass H., Rusch V., Gerald W., Huang S.F., Yang P.C., Miller V., Ladanyi M., Yang C.H., Pao W. MET amplification occurs with or without T790M mutations in EGFR mutant lung tumors with acquired resistance to gefitinib or erlotinib. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:20932–20937. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710370104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Engelman J.A., Zejnullahu K., Mitsudomi T., Song Y., Hyland C., Park J.O., Lindeman N., Gale C.M., Zhao X., Christensen J., Kosaka T., Holmes A.J., Rogers A.M., Cappuzzo F., Mok T., Lee C., Johnson B.E., Cantley L.C., Janne P.A. MET amplification leads to gefitinib resistance in lung cancer by activating ERBB3 signaling. Science. 2007;316:1039–1043. doi: 10.1126/science.1141478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lutterbach B., Zeng Q., Davis L.J., Hatch H., Hang G., Kohl N.E., Gibbs J.B., Pan B.S. Lung cancer cell lines harboring MET gene amplification are dependent on Met for growth and survival. Cancer Res. 2007;67:2081–2088. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Looyenga B.D., Cherni I., Mackeigan J.P., Weiss G.J. Tailoring tyrosine kinase inhibitors to fit the lung cancer genome. Transl Oncol. 2011;4:59–70. doi: 10.1593/tlo.10241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Siddiqui A.D., Piperdi B. KRAS mutation in colon cancer: a marker of resistance to EGFR-I therapy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:1168–1176. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0811-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Winkles J.A. The TWEAK-Fn14 cytokine-receptor axis: discovery, biology and therapeutic targeting. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008;7:411–425. doi: 10.1038/nrd2488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feng S.L., Guo Y., Factor V.M., Thorgeirsson S.S., Bell D.W., Testa J.R., Peifley K.A., Winkles J.A. The Fn14 immediate-early response gene is induced during liver regeneration and highly expressed in both human and murine hepatocellular carcinomas. Am J Pathol. 2000;156:1253–1261. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64996-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tran N.L., McDonough W.S., Donohue P.J., Winkles J.A., Berens T.J., Ross K.R., Hoelzinger D.B., Beaudry C., Coons S.W., Berens M.E. The human Fn14 receptor gene is up-regulated in migrating glioma cells in vitro and overexpressed in advanced glial tumors. Am J Pathol. 2003;162:1313–1321. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63927-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tran N.L., McDonough W.S., Savitch B.A., Fortin S.P., Winkles J.A., Symons M., Nakada M., Cunliffe H.E., Hostetter G., Hoelzinger D.B., Rennert J.L., Michaelson J.S., Burkly L.C., Lipinski C.A., Loftus J.C., Mariani L., Berens M.E. Increased fibroblast growth factor-inducible 14 expression levels promote glioma cell invasion via Rac1 and nuclear factor-kappaB and correlate with poor patient outcome. Cancer Res. 2006;66:9535–9542. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Watts G.S., Tran N.L., Berens M.E., Bhattacharyya A.K., Nelson M.A., Montgomery E.A., Sampliner R.E. Identification of Fn14/TWEAK receptor as a potential therapeutic target in esophageal adenocarcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2007;121:2132–2139. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang S., Zhan M., Yin J., Abraham J.M., Mori Y., Sato F., Xu Y., Olaru A., Berki A.T., Li H., Schulmann K., Kan T., Hamilton J.P., Paun B., Yu M.M., Jin Z., Cheng Y., Ito T., Mantzur C., Greenwald B.D., Meltzer S.J. Transcriptional profiling suggests that Barrett's metaplasia is an early intermediate stage in esophageal adenocarcinogenesis. Oncogene. 2006;25:3346–3356. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Willis A.L., Tran N.L., Chatigny J.M., Charlton N., Vu H., Brown S.A., Black M.A., McDonough W.S., Fortin S.P., Niska J.R., Winkles J.A., Cunliffe H.E. The fibroblast growth factor-inducible 14 receptor is highly expressed in HER2-positive breast tumors and regulates breast cancer cell invasive capacity. Mol Cancer Res. 2008;6:725–734. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-08-0005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Michaelson J.S., Cho S., Browning B., Zheng T.S., Lincecum J.M., Wang M.Z., Hsu Y.M., Burkly L.C. Tweak induces mammary epithelial branching morphogenesis. Oncogene. 2005;24:2613–2624. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fortin S.P., Ennis M.J., Savitch B.A., Carpentieri D., McDonough W.S., Winkles J.A., Loftus J.C., Kingsley C., Hostetter G., Tran N.L. Tumor necrosis factor-like weak inducer of apoptosis stimulation of glioma cell survival is dependent on Akt2 function. Mol Cancer Res. 2009;7:1871–1881. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-09-0194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tran N.L., McDonough W.S., Savitch B.A., Sawyer T.F., Winkles J.A., Berens M.E. The tumor necrosis factor-like weak inducer of apoptosis (TWEAK)-fibroblast growth factor-inducible 14 (Fn14) signaling system regulates glioma cell survival via NFkappaB pathway activation and BCL-XL/BCL-W expression. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:3483–3492. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409906200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Culp P.A., Choi D., Zhang Y., Yin J., Seto P., Ybarra S.E., Su M., Sho M., Steinle R., Wong M.H., Evangelista F., Grove J., Cardenas M., James M., Hsi E.D., Chao D.T., Powers D.B., Ramakrishnan V., Dubridge R. Antibodies to TWEAK receptor inhibit human tumor growth through dual mechanisms. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:497–508. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meighan-Mantha R.L., Hsu D.K., Guo Y., Brown S.A., Feng S.L., Peifley K.A., Alberts G.F., Copeland N.G., Gilbert D.J., Jenkins N.A., Richards C.M., Winkles J.A. The mitogen-inducible Fn14 gene encodes a type I transmembrane protein that modulates fibroblast adhesion and migration. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:33166–33176. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.46.33166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roberts P.E., Phillips D.M., Mather J.P. A novel epithelial cell from neonatal rat lung: isolation and differentiated phenotype. Am J Physiol. 1990;259:L415–L425. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1990.259.6.L415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Greulich H., Chen T- H., Feng W., Jänne P.A., Alvarez J.V., Zappaterra M., Bulmer S.E., Frank D.A., Hahn W.C., Sellers W.R., Meyerson M. Oncogenic transformation by inhibitor-sensitive and -resistant EGFR mutants. PLoS Med. 2005;2:e313. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Backhus L.M., Sievers E., Lin G.Y., Castanos R., Bart R.D., Starnes V.A., Bremner R.M. Perioperative cyclooxygenase 2 inhibition to reduce tumor cell adhesion and metastatic potential of circulating tumor cells in non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2006;132:297–303. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2005.10.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cai Z., Zhang H., Liu J., Berezov A., Murali R., Wang Q., Greene M.I. Targeting erbB receptors. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2010;21:961–966. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2010.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kruser T.J., Wheeler D.L. Mechanisms of resistance to HER family targeting antibodies. Exp Cell Res. 2010;316:1083–1100. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2010.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yarden Y., Sliwkowski M.X. Untangling the ErbB signalling network. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:127–137. doi: 10.1038/35052073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sharma S.V., Settleman J. ErbBs in lung cancer. Exp Cell Res. 2009;315:557–571. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2008.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kobayashi S., Boggon T.J., Dayaram T., Janne P.A., Kocher O., Meyerson M., Johnson B.E., Eck M.J., Tenen D.G., Halmos B. EGFR mutation and resistance of non-small-cell lung cancer to gefitinib. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:786–792. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa044238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xie Z., Peng J., Pennypacker S.D., Chen Y. Critical role for the catalytic activity of phospholipase C-gamma1 in epidermal growth factor-induced cell migration. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;399:425–428. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.07.098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pillai S., Rizwani W., Li X., Rawal B., Nair S., Schell M.J., Bepler G., Haura E., Coppola D., Chellappan S. ID1 facilitates the growth and metastasis of non-small cell lung cancer in response to nicotinic acetylcholine receptor and epidermal growth factor receptor signaling. Mol Cell Biol. 2011;31:3052–3067. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01311-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li Z., Dong Q., Wang Y., Qu L., Qiu X., Wang E. Downregulation of Mig-6 in nonsmall-cell lung cancer is associated with EGFR signaling. Mol Carcinog. 2011 doi: 10.1002/mc.20815. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/mc.20815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Huang M., Narita S., Tsuchiya N., Ma Z., Numakura K., Obara T., Tsuruta H., Saito M., Inoue T., Horikawa Y., Satoh S., Habuchi T. Overexpression of Fn14 promotes androgen independent prostate cancer progression through MMP-9 and correlates with poor treatment outcome. Carcinogenesis. 2011;32:1589–1596. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgr182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Winkles J.A., Tran N.L., Berens M.E. TWEAK and Fn14: new molecular targets for cancer therapy? Cancer Lett. 2006;235:11–17. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2005.03.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhou H., Marks J.W., Hittelman W.N., Yagita H., Cheung L.H., Rosenblum M.G., Winkles J.A. Development and characterization of a potent immunoconjugate targeting the Fn14 receptor on solid tumor cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2011;10:1276–1288. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-11-0161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Michaelson J.S., Amatucci A., Kelly R., Su L., Garber E., Day E.S., Berquist L., Cho S., Li Y., Parr M., Wille L., Schneider P., Wortham K., Burkly L.C., Hsu Y.M., Joseph I.B. Development of an Fn14 agonistic antibody as an anti-tumor agent. MAbs. 2011;3:362–375. doi: 10.4161/mabs.3.4.16090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]