Abstract

FtsZ, the primary cytoskeletal element of the Z ring, which constricts to divide bacteria, assembles into short, one-stranded filaments in vitro. These must be further assembled to make the Z ring in bacteria. Conventional electron microscopy (EM) has failed to image the Z ring or resolve its substructure. Here we describe a procedure that enabled us to image reconstructed, inside-out FtsZ rings by negative-stain EM, revealing the arrangement of filaments. We took advantage of a unique lipid that spontaneously forms 500 nm diameter tubules in solution. We optimized conditions for Z-ring assembly with fluorescence light microscopy and then prepared specimens for negative-stain EM. Reconstituted FtsZ rings, encircling the tubules, were clearly resolved. The rings appeared as ribbons of filaments packed side by side with virtually no space between neighboring filaments. The rings were separated by variable expanses of empty tubule as seen by light microscopy or EM. The width varied considerably from one ring to another, but each ring maintained a constant width around its circumference. The inside-out FtsZ rings moved back and forth along the tubules and exchanged subunits with solution, similarly to Z rings reconstituted outside or inside tubular liposomes. FtsZ from Escherichia coli and Mycobacterium tuberculosis assembled rings of similar structure, suggesting a universal structure across bacterial species. Previous models for the Z ring in bacteria have favored a structure of widely scattered filaments that are not in contact. The ribbon structure that we discovered here for reconstituted inside-out FtsZ rings provides what to our knowledge is new evidence that the Z ring in bacteria may involve lateral association of protofilaments.

Introduction

FtsZ is found in virtually all prokaryotes, where it is the major cytoskeleton protein involved in cell division (1,2). In vitro, FtsZ assembles into short, single-stranded protofilaments that average 120–250 nm in length (3,4). In vivo, light microscopy has shown that FtsZ assembles into a ring structure (Z ring) in the middle of the cell (5). The Z ring appears to be a continuous filament of uniform brightness, averaging two to six protofilaments wide, that encircles the ∼3000 nm circumference (2). It is unknown how these short protofilaments come together to form the Z ring. Conventional electron microscopy (EM) has not been able to resolve the substructure of the Z ring, probably because the bacterial cytoplasm is too crowded and granular for one to visualize the small number of FtsZ protofilaments. Light microscopy is limited by its 250 nm resolution.

Two major opposing models for the arrangement of protofilaments in the Z ring have been proposed. In one model, the short protofilaments in the Z ring are arranged in a scattered band at midcell, with no contacts between adjacent protofilaments. In the other model, the filaments are arranged side by side in a single layer or ribbon, connected by lateral contacts.

Several pieces of evidence support the proposal of a scattered band of filaments. First, in the presence of GTP, Escherichia coli FtsZ assembles into short, single-stranded protofilaments in vitro (3). In physiological buffers, they show little or no tendency for lateral association. Second, fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) studies showed that FtsZ subunits in the Z ring turned over with a half-time of 9 s (6). This would imply that subunits can escape from the Z ring with ease, which might be impeded if they were bound by lateral bonds. Third, photoactivated localization microscopy was used to study the Z ring in E. coli (7,8) and although individual protofilaments were not resolved, the Z ring was estimated to have a width of ∼67–110 nm, which is much wider than the 10–30 nm of a ribbon of two to six protofilaments. Fourth (and the strongest evidence to date), in a structural study of Caulobacter crescentus by electron cryotomography (9), reconstructed images revealed short, individual protofilaments widely scattered around the division site, and mostly not in contact. No complete, closed rings were observed. In this case, individual filaments were proposed to generate bending forces on the membrane (9). The filaments may communicate with each other through bends in the membrane (10).

However, several studies also support the proposal of lateral contacts in the Z ring. Unlike the single-stranded E. coli FtsZ protofilaments that formed under physiological conditions, FtsZ from several other species of bacteria, such as Thermotoga maritime, Methanococcus jannaschii, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, and Bacillus subtilis, have been shown to form assemblies that consist of lateral contacts (11–14). FtsZ plus the polycation DEAE dextran assembled ribbons of protofilaments with regular lateral bonds (15). Assembly in the presence of Ficoll or polyvinyl alcohol, which are thought to mimic the crowding conditions of the cytoplasm, caused the formation of large bundles of protofilaments. These must involve lateral associations, and additionally bonds in the third dimension (16,17). Optical diffraction analysis suggested that the bundles were composed of liquid crystal-like packing of filaments. FtsZ observed by atomic force microscopy (AFM) on mica has been interpreted as showing lateral association (18). However, an AFM study under more dilute conditions showed no evidence of lateral association (19). A rheological study indicated bundling at high concentrations of FtsZ (25 μM) without crowding agents, and the bundling was inhibited by MinC, a regulator of bacterial cell division (20).

Recent work has shown that FtsZ can form Z rings inside or outside tubular liposomes if it is tethered to the membrane (21,22). The inside-versus-outside position depends on the location of the membrane-targeting sequence (mts), a short, amphipathic helix that inserts into the lipid bilayer. FtsZ-yellow fluorescent protein (YFP)-mts (mts on the C-terminus, the normal position) assembles Z rings on the inside of tubular liposomes, whereas mts-FtsZ-YFP (mts on the N-terminus, on the opposite side of the protofilament) assembles rings that wrap around the outside of the liposomes. We refer to these as “inside-out FtsZ rings” to distinguish them from Z rings in bacteria and those reconstituted on the inside of liposomes. The Z rings inside liposomes pull the concave membrane to a smaller diameter, whereas inside-out FtsZ rings on the outside squeeze the convex surface. This suggests that the constriction force is generated by a curved conformation of FtsZ protofilaments generating a bending force on the membrane (22).

In previous studies, the reconstituted Z rings were visualized by fluorescence light microscopy of YFP. Attempts to further examine the structure of these Z rings by negative-stain EM were unsuccessful. The liposomes used in those studies were converted into tubular shapes by shearing with the coverslip, which was difficult to reproduce on EM grids.

In the study presented here, we developed another lipid tubule system to investigate Z ring substructure. The synthetic lipid 1,2-bis(10,12-tricosadiynoyl)-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DC8,9PC or DC23PC), which has a diacetylenic group halfway down each of its 23-carbon hydrocarbon chains, spontaneously forms hollow tubes ∼0.5 μm in diameter and 1–100 μm long (23–25). The diameter is larger than the 0.25 μm resolution of the light microscope, permitting observation of rings by fluorescence microscopy. We were able to find conditions in which a large fraction of the lipid tubules assembled inside-out FtsZ rings, and we then prepared specimens for negative-stain EM. The images show that these reconstructed rings consist of ribbons of protofilaments with irregular lateral contacts between adjacent protofilaments. This protofilament arrangement does not prove or disprove either model for the structure of the Z ring, but it does to our knowledge provide new evidence favoring the lateral contact model.

Materials and Methods

Purification of membrane-targeted FtsZ

E. coli FtsZ-YFP-mts and mts-FtsZ-YFP were purified as described previously (26). For M. tuberculosis FtsZ, an mts comprising the sequence MGGRFIEEEKKGFLKRLFGGHMGAELTQASGTTSH (where the mts is underlined) was fused to the N-terminus. Expression and purification of M. tuberculosis mts-FtsZ-YFP were performed similarly, with the following exceptions: M. tuberculosis FtsZ was induced at 37°C with 0.5 mM isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) and expressed overnight. Soluble protein was cut with 20% ammonium sulfate to remove impurities, and then FtsZ was precipitated with 40% ammonium sulfate. The protein was then further purified by chromatography on a resource Q column (GE Healthcare, Pittsburgh, PA). All proteins were dialyzed into HMKCG (50 mM HEPES pH 7.7, 5 mM magnesium acetate, 300 mM potassium acetate, 50 mM potassium chloride, 10% glycerol) before experiments were conducted. The HMKCG buffer was previously optimized for Z ring formation, as described by Osawa and Erickson (27). Protein concentration was determined by absorbance of YFP at 515 nm (ε = 92,200 M−1 cm−1).

Tubule preparation

We purchased 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-(1′-rac-glycerol) (DOPG) and egg phosphatidyl choline (PC) from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL). DC8,9PC lipid was provided by Dr. Banahalli Ratna (Naval Research Laboratory, Washington, DC). Tubules were prepared by mixing DC8,9PC, DOPG, and egg PC in a 3:1:1 ratio, respectively. The lipid mixture was dried under vacuum and then resuspended in 80% methanol at 2 mg/ml total lipid. The lipids were heated (55–60°C) for 30 min. The mixture was then placed on the bench at room temperature for 30 min, and tubules formed as the suspension cooled (23,24,28). The tubules were stored at 4°C.

Light microscopy

The tubule stock for all preparations was 2 mg/ml lipid in 80% methanol. The following conditions were used to assemble inside-out FtsZ rings on the tubules: For E. coli mts-FtsZ-YFP, 10 μl HMKCG buffer (defined above) contained 3.5 μM FtsZ protein, 1 μg tubules, and 1 mM GTP (for the experiment shown in Fig. 5, the FtsZ was 1.75 μM). For M. tuberculosis mts-FtsZ-YFP, 10 μl HMK350 buffer (50 mM HEPES pH 7.7, 5 mM magnesium acetate, 350 mM potassium chloride) contained 3.5 μM FtsZ protein, 1 μg tubules, and 1 mM GTP. For E. coli FtsZ-YFP-mts, 10 μl HMK350 buffer contained 5 μM FtsZ protein, 1.6 μg tubules, and 1 mM GTP.

Figure 5.

Representative negative-stain EM images of minimal FtsZ rings formed on tubules. Protein concentration: 1.75 μM. Scale bar: 500 nm.

Reactions were observed on a glass slide with a coverslip. Differential interference contrast (DIC) and fluorescence images of tubules and membrane-targeted FtsZ were obtained with a Zeiss Axiophot microscope with 100× magnification lens (NA 1.3) and CCD camera (Coolsnap HQ; Roper, Ottobrun, Germany). Some images were obtained with a Leica microscope DMI4000B with a 100× lens (NA 1.4) and a CCD camera (Coolsnap HQ2; Roper). A filter cube optimized for YFP was used for fluorescence images. All experiments were performed at room temperature, which is below the melting temperature of the lipids. The final percentage of methanol in the samples was 4%. It did not affect protofilament assembly as detected by EM.

FRAP assay

FRAP assays were performed with a Zeiss LSM Live DuoScan confocal microscope. The fluorescence intensities in the specific areas were analyzed with ImageJ (National Institutes of Health). A recovery curve was fitted to a single exponential equation, and recovery half-times were determined as previously described (6).

EM

For negative staining, grids covered with a thin carbon film were made hydrophilic by exposure to UV light and ozone as described by Burgess et al. (29). The lamp they used is no longer available, so we substituted a Spectroline 11SC-1 Pencil shortwave UV lamp (catalog number 11-992-30; Fischer Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) and UVP Pen-Ray lamp power supply (catalog number UVP99 0055 01; Fischer Scientific). Grids were treated for 45 min and used within 4 h. A 10 μL volume of sample was applied to the UV-treated grid and stained with three drops of 2% uranyl acetate. Images were collected on a Philips EM420 equipped with a CCD camera.

Results

DC8,9PC lipid tubules

The self-assembling DC8,9PC lipid formed a mixture of smooth tubules and helical structures, as previously reported (25,30). These were easily resolved by DIC light microscopy (Fig. 1 A) and by negative-stain EM (see Fig. 3 A). The EM showed a range of widths, with an average of 0.57 μm and lengths of 10–100 μm, which agrees with previously published data (23–25). These measurements were also consistent with the light microscopy images, in which the tubules were somewhat larger than the resolution.

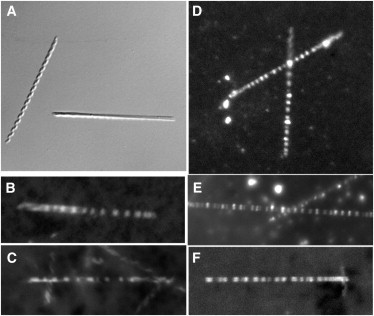

Figure 1.

Representative light microscopy images of FtsZ rings on tubules. Tubules were composed of 60% DC8,9PC, 20% DOPG, and 20% PC. Tubules were mixed with protein and GTP, and then viewed with the light microscope. (A) Tubules alone in DIC. (B and C) FtsZ-YFP-mts Z rings formed inside tubules. (D–F) Mts-FtsZ-YFP Z rings formed around the outside of tubules.

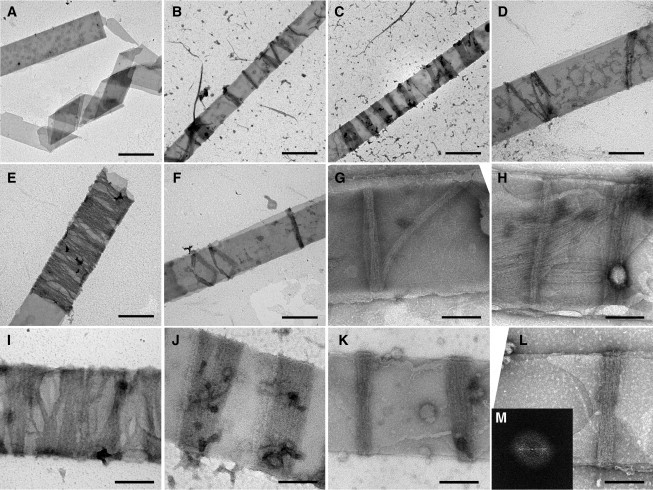

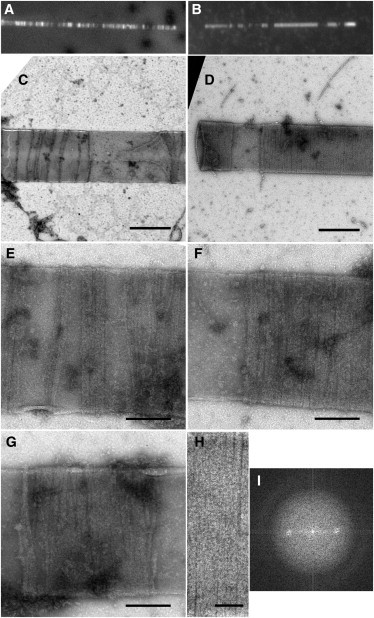

Figure 3.

Negative-stain EM images of FtsZ rings on tubules. (A) Tubules alone. Scale bar: 500 nm. (B–F) Mts-FtsZ-YFP Z rings around the outside of lipid tubules. Scale bar: 500 nm. (G and H) FtsZ-YFP-mts Z rings inside lipid tubules. Scale bar: 200 nm. (I–L) Mts-FtsZ-YFP Z rings outside lipid tubules. Scale bar: 200 nm. Representative Fourier transform of Z-ring images (M).

Next, we investigated the ability of membrane-targeted FtsZ to form inside-out FtsZ rings in the presence of DC8,9PC tubules. We found no conditions in which the protein was able to form Z rings, either inside (FtsZ-YFP-mts) or outside (mts-FtsZ-YFP) the pure DC8,9PC tubules. In our previous study, we found that optimal Z-ring assembly required some fraction of negatively charged lipid, presumably to balance the positive charges on the amphipathic helix (mts) (27). Because DC8,9PC is a neutral lipid, we tested adding a negatively charged lipid, DOPG. The addition of DOPG did not affect the diameter, length, or formation of the tubules. These mixed-lipid tubules supported the assembly of FtsZ rings. We determined that 20% DOPG was ideal for these assays, and used it for all of the experiments described below. The tubule mix also contained 20% PC and 60% DC8,9PC. The 20% charged lipid is similar to the ratio used in previous liposome studies (21,22,26).

Membrane-targeted FtsZ rings were visible with the light microscope

In initial light microscopy studies, we focused on confirming the ability of FtsZ to form FtsZ rings inside the newly developed lipid tubule system. When FtsZ-YFP-mts and GTP were added to the tubules, we were able to detect faint FtsZ rings via light microscopy (Fig. 1 B and C). These rings were difficult to image because they photobleached very quickly. This suggests that inside the tubule, the amount of free protein (not in protofilaments or the ring) was limited and therefore could not exchange with the Z ring to compensate for photobleaching.

We also examined mts-FtsZ-YFP for assembly of inside-out FtsZ rings around the outside of tubules. Here the photobleaching should be minimized, because free FtsZ in solution can easily exchange with protofilaments in the ring, as confirmed by FRAP (see below). When mts-FtsZ-YFP and GTP were mixed with tubules, rings were clearly visible via light microscopy (Fig. 1, D–F). The constant brightness of the rings and lack of photobleaching suggest that the FtsZ rings were wrapping around the outside of the tubules and were able to exchange with FtsZ in solution. These FtsZ rings typically appeared as sharp bands, suggesting a width of <0.25 μm, and were sufficiently separated to be resolved in the light microscope. Larger fluorescent patches were sometimes seen, indicating either an abnormally wide FtsZ ring or closely packed individual rings (Fig. 1 F).

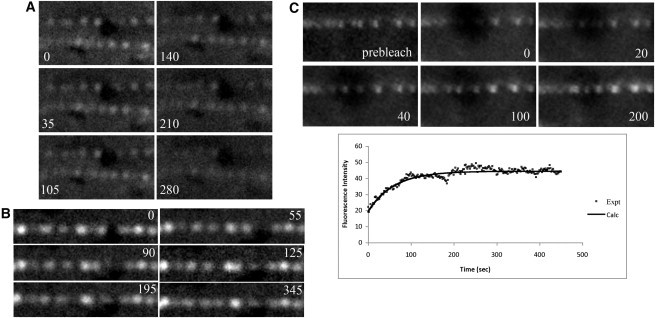

Inside-out FtsZ rings on lipid tubules are dynamic structures

To verify that these reconstituted FtsZ rings on DC8,9PC lipid tubules were similar to Z rings previously reconstituted on tubular liposomes and to Z rings in E. coli cells, we examined several Z-ring properties. First, the rings only formed in the presence of GTP (or GMPCPP), suggesting that filament assembly is required to form a ring. When a limiting amount of GTP was present (100 μM), the rings disappeared over time (Fig. 2 A, and Movie S1 in the Supporting Material). Second, light microscopy studies showed that the inside-out FtsZ rings were able to slide back and forth on the tubules (Fig. 2 B and Movie S2), suggesting that these rings were dynamic, as in previous reconstitutions. Third, FRAP assays revealed a recovery half-time of ∼45 s for these rings (Fig. 2 C and Movie S3), which was similar to the ∼30 s half-time measured for Z rings on the inside or outside of tubular liposomes (22,26). Although there was some movement of the FtsZ rings during recovery, the fluorescence mostly returned to the same rings, meaning that it involved exchange of subunits between the FtsZ ring and solution, and not the migration of existing rings into the bleached areas. The exponential nature of the recovery is also consistent with exchange. Overall, the data suggest that inside-out FtsZ rings that form on DC8,9PC lipid tubes behave similarly to rings that are reconstituted on the outside of tubular liposomes in vitro (26). The exchange is slower in both in vitro systems than the 9 s half-time observed in E. coli (6).

Figure 2.

Mts-FtsZ-YFP Z rings were dynamic. (A) A time-lapse series of fluorescence images of the disappearance of FtsZ rings associated with the exhaustion of GTP. (B) Time-lapse series of fluorescence images of FtsZ ring movement. (C) Time-lapse series of fluorescence images of the FRAP assay. Plotted below is the intensity of photobleached region over time. Recovery half-time: ∼45 s. All times listed in seconds.

Having determined the optimal conditions for ring assembly by light microscopy, we then examined the lipid tubules by negative-stain EM to determine the substructure of the rings.

Arrangement of filaments on lipid tubules

Negative-stain EM of FtsZ-YFP-mts, which presumably formed Z-ring-like structures inside the lipid tubules, was challenging, but some convincing images were found (Fig. 3, G and H). The rings appeared as ribbons of protofilaments ∼50 nm wide. Given that FtsZ protofilaments are ∼5 nm wide, these Z rings contained ∼10 protofilaments. The rings were mostly perpendicular to the axis of the tube (although one in Fig. 3 G is running diagonally), and were consistent with a closed circular structure, although the top and bottom were mostly superimposed. Also visible on some tubes were longitudinal filament arrays (Fig. 3 H). We believe these longitudinal filaments were on the outside of the tubules due to the point of membrane attachment, as was shown in a previous study (26). Due to the problems with photobleaching in the light microscope and the infrequency of FtsZ-YFP-mts Z rings in negative-stain EM, the remaining studies were conducted with mts-FtsZ-YFP, which forms inside-out FtsZ rings wrapping around the outside of tubules.

For mts-FtsZ-YFP, negative-stain EM showed numerous rings around the outside of the lipid tubules (Fig. 3, B–F and I–L). In similarity to the C-terminal mts, these rings appeared closed and were mostly perpendicular to the length of the tubule. Inside-out FtsZ rings were much more abundant than the C-terminal Z rings and covered large sections of each tubule, most likely due to increased protein accessibility (Fig. 3, B–D). The spacing between rings was varied, suggesting that the rings formed independently of each other.

The predominant structures observed in the negatively stained images were ribbons of protofilaments, with a width mostly narrower than the 250 nm resolution of the light microscope, and spacing consistent with the light microscopy images. We identified these as reconstituted, inside-out FtsZ rings. Occasionally a ring appeared to be tilted, showing the continuity of the ring as a complete circle (Fig. 3 F). In most cases, the Z rings appeared as a single band perpendicular to the length of the tubule, suggesting that the top and bottom surfaces were superimposed. Extended patch-like structures were observed on some lipid tubules (Fig. 3 E). These patches appeared to be a wrapping of ribbons of filaments around a tubule, with small, uneven gaps and a width up to 1–2 μm (Fig. 3, E and I). These could also be interpreted as multiple, closely packed FtsZ rings.

Apart from the extended patches, the rings mostly varied in width from 50 to 250 nm (Fig. 3, B and C, J–L), which equates to 10–50 protofilaments. This result, in similarity to the C-terminal mts images, suggests that there is no predetermined width for an FtsZ ring. However, a remarkable observation is that each individual ring maintained a constant width as it encircled the tubule. The EM images showed that the rings were evenly stained, suggesting that they had a constant thickness in the radial direction, most likely one subunit thick. The variable intensity of the rings in the light microscope would then correspond to the variable width of the ribbons. Fourier transform analysis of the rings sometimes showed an equatorial reflection at ∼4.8 nm, indicating a 4.8 nm average spacing of adjacent protofilaments (Fig. 3 M).

To further probe the substructure of the rings, we performed thin-section EM using a methodology previously applied to FtsZ polymers stabilized by DEAE dextran (31). We were able to find lipid tubules in cross and longitudinal sections, but we could not reliably identify FtsZ rings and we never saw structures that rivaled the resolution of the negative stain. However, the cross sections did give us a more accurate measure of the diameter of the tubules, which was 363 ± 38 nm (Fig. S1). The 571 ± 66 nm width of the tubules measured in negative stain is half the circumference of the tubules in thin section, suggesting that the tubules are flattened in negative stain.

Dilution of membrane-targeted FtsZ does not affect ring structure

In vivo, E. coli FtsZ is attached to the membrane via FtsA and ZipA (32). Unfortunately, the ratio of FtsA/ZipA to FtsZ in the Z ring is unknown. It is possible that not all FtsZ in the Z ring is tethered to the membrane. To mimic the in vivo situation, we diluted the membrane-targeted FtsZ with wild-type protein.

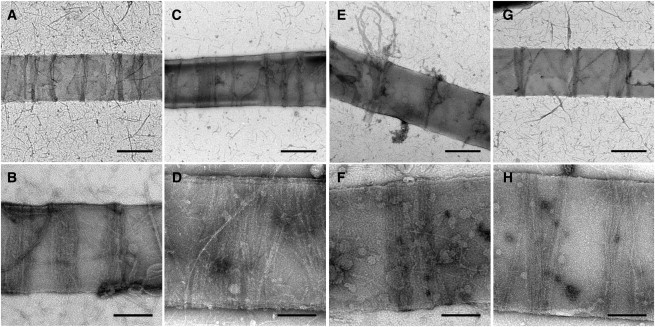

We prepared rings on the lipid tubules using different ratios of mts-FtsZ-YFP and wild-type FtsZ (Fig. 4). Because the mts was diluted, the number of tubule attachment points per ring was also diluted, which led to some images of rings falling off tubules (Fig. 4 E). With the 1:1 ratio, the rings were similar to mts-FtsZ-YFP rings in width (Fig. 4, A and B). In the 1:3 and 1:5 ratio samples, thinner rings were also observed (Fig. 4, C–H). With the 1:3 ratio, the rings ranged from 45 to 150 nm in width, whereas with the 1:5 ratio, the width range was slightly smaller (60–110 nm). These width differences could be caused by the reduced number of tethers per protofilament. However, all of the rings still consisted of multiple filaments, suggesting that the ribbon formation is a characteristic of the FtsZ ring and is independent of the mts and YFP. Similarly to pure mts-FtsZ-YFP rings, the diluted rings were mostly perpendicular to the length of the tubule and were scattered across the entire length of the tubule. Even though there were some spaces in the ribbons, most filaments appeared in lateral contact with their neighbors.

Figure 4.

Negative-stain EM of mixed mts/wt FtsZ rings on tubules: (A and B) 1:1 mts/wt, (C–F) 1:3 mts/wt, and (G and H) 1:5 mts/wt. Scale bar: 500 nm (A, C, E, and G) and 200 nm (B, D, F, and H).

We also tested the effect of lowering the total membrane-targeted FtsZ concentration to 1.75 μM, only slightly above the ∼1 μM critical concentration for protofilament assembly. Rings were still observed under these conditions by light microscopy and negative-stain EM (Fig. 5, A and B). EM images showed a ribbon structure, with most rings three to 10 protofilaments wide (much smaller than at the higher concentration). The thinnest rings identified were ∼15 nm, which would equate to three protofilaments. The majority of the rings were closed circles perpendicular to the length of the tubules, but some consisted of an arc of filaments (Fig. 5 A), suggesting the initial formation of a new ring. At 0.75 μM mts-FtsZ-YFP, thin rings assembled that were similar to those at 1.75 μM, but they were less frequent. Because this is below the critical concentration for assembly in solution, it suggests that FtsZ may be concentrated by tethering to the membrane.

M. tuberculosis FtsZ formed inside-out FtsZ rings around DC8,9PC lipid tubules

To verify that the results described here were not specific to E. coli, we decided to test an FtsZ from another bacterial species, M. tuberculosis, which has 53% sequence identity over the conserved core. Because the N-terminal mts worked best for E. coli, this mts was cloned into the N-terminus of M. tuberculosis FtsZ-YFP and the construct was examined for Z-ring assembly. M. tuberculosis FtsZ assembles one-stranded, short filaments above pH 7, but at pH 6.5 it assembles long, two-stranded filaments (12). We tested assembly at both pH values and found identical ring structures. This suggests that the two-stranded structure is neither essential nor inhibitory for ring assembly. Results are shown for pH 7.7 (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

M. tuberculosis mts-FtsZ-YFP Z rings on tubules detected via light microscopy (A and B) or negative-stain EM (C–G). Closer view of the FtsZ ring by negative-stain EM (H) and its Fourier transform (I). Scale bar: 500 nm (C and D), 200 nm (E–G), and 100 nm (H).

Similarly to the E. coli construct, M. tuberculosis mts-FtsZ-YFP formed fluorescent bands on the tubules (Fig. 6, A and B), which we identify as inside-out FtsZ rings. Negative-stain EM showed ribbon structures similar to those of E. coli. The M. tuberculosis rings appeared closed, perpendicular to the length of the tubule, and irregularly spaced along the length of the tubule (Fig. 6, C–H). They appeared to be ribbons of protofilaments of variable width from one ring to another, but remarkably constant in width for each individual ring. In addition, Fourier transform analysis of the M. tuberculosis rings revealed an equatorial reflection at ∼4.8 nm (Fig. 6 I), the same as for E. coli rings.

Discussion

Our ultimate goal is to obtain high-resolution EM images of the Z ring in bacteria. With one exception (9) (addressed below), this goal has eluded investigators, largely because the Z ring in most bacterial species averages only two to six protofilaments in width (2) and thus are lost in the granular cytoplasm. An alternative strategy is to reconstitute Z rings in vitro from purified FtsZ and liposomes. In a previous study, we succeeded in reconstituting FtsZ rings inside tubular liposomes by providing an amphipathic helix membrane tether at the C-terminus (21). We later reconstituted inside-out Z rings on the outside of tubular liposomes by switching the membrane tether to the N-terminus, which is on the opposite side of the protofilament (22). We interpreted these reconstituted Z rings as models of the biological Z rings in bacteria. The main difference is that the FtsZ protofilaments in the reconstituted FtsZ rings are tethered directly to the membrane, whereas in natural Z rings they are tethered indirectly through FtsA and ZipA. In addition to self-assembly of structures that resembled real Z rings according to several criteria, these reconstituted FtsZ rings, both inside and outside, generated a constriction force on the membrane.

Although we have no proof that the reconstituted, inside-out FtsZ rings imaged here reflect the structure of natural Z rings in bacterial cells, they do share several important structural and dynamic features: 1), they are mostly thinner than the 250 nm resolution of the light microscope. 2), they are separated by distances much greater than 250 nm; 3), they encircle the liposome perpendicular to the long axis, but occasionally open or tilt into a helix; 4), they move back and forth along the axis of the liposome (although this movement is more limited in vivo by the Min and Noc system); 5), they exchange subunits with a half-time of 9 s in vivo or 30–45 s in vitro; and 6), they generate a constriction force on the membrane (this is only really demonstrated for the reconstituted Z rings, but deduced to apply in vivo). Of course, it is possible that the structure of these reconstituted Z rings (in particular the arrangement of protofilaments) is different from that of natural Z rings. However, at the light-microscope level, the structure and dynamics seem very similar, and we believe that the ribbon structure of the inside-out FtsZ rings imaged here by EM is likely relevant to Z rings in vivo.

There was one significant difference between the inside-out FtsZ rings on DC8,9PC tubules and those assembled previously on tubular PC liposomes. The rings on the DC8,9PC tubules showed no constrictions. This may be due to the rigidity of the DC8,9PC tubules. Rigidity is suggested by the narrow range of diameters, as opposed to the broad range of diameters for tubular and spherical liposomes. Previous authors have commented on the apparent rigidity of these tubules (23,33).

The rings reconstituted on the DC8,9PC tubules provided the first sample for successful negative-stain EM. The ribbon structures seen in these images suggest that this might also apply to Z rings reconstituted inside and outside tubular liposomes, and to the actual Z rings in bacteria. The thinnest Z rings obtained (15 nm wide) correspond to ∼3 protofilaments. This is comparable to the Z-ring width of 2–6 protofilaments determined in bacterial cells (2).

Additional support for the notion that an in vivo Z ring has a narrow ribbon structure comes from a study by Diestra et al. (34), who used a gold-labeled metallothionein to examine the localization of several E. coli proteins by EM. One of the proteins was AmiC, a structural protein associated with the Z ring. They found that in dividing E. coli cells, AmiC localized into distinct aggregates at the site of the septal ring. These aggregates were only 15–20 nm wide, which would correspond to a ribbon Z ring of two to four protofilaments. Note that these Z rings were from E. coli cells that were rapidly frozen and fixed by freeze substitution in methanol.

In the primary competing structural model for the Z ring, short protofilaments are scattered in a narrow zone but do not make lateral contact. The primary support for this model comes from an electron cryotomography study of Caulobacter crescentus (9). In that study, some images showed ribbons of protofilaments, especially in cells overexpressing wild-type FtsZ or a hyperstable mutant, G109S. However, most of the identified structures were isolated, short protofilaments with no lateral contacts to other protofilaments. The arc-like protofilaments were scattered along the constriction site, oriented mostly circularly, but they did not form a continuous ring.

Two groups have used super-resolution light microscopy (photoactivation light microscopy) to image the Z ring in bacteria (7,8). In both studies, the FtsZ-FP was used as a dilute label and thus could not resolve individual protofilaments. However, both groups reported the width of the Z ring to be wider than the 10–30 nm expected for a ribbon of two to six protofilaments (2). Fu et al. (7) reported a width of 110 nm. However, they imaged cells that were fixed with paraformaldehyde, which has never been demonstrated as a high-resolution fixative. Formaldehyde fixation becomes ineffective for complexes with a half-time of <5 s (35), which is close to the 9 s half-time for FtsZ turnover in the Z ring. Biteen et al. (8) reported an average width of 67 nm for Z rings in live cells. This is only slightly larger than the width of a ribbon convoluted with their ∼20 nm resolution. The measured width may have been exaggerated by lateral movements of the Z ring during the 15 s imaging time.

Several studies have demonstrated the ability of FtsZ to assemble into two-dimensional sheets and three-dimensional bundles when stabilized by DEAE dextran (15), divalent cations (36), 1 M sodium glutamate plus calcium (37), or crowding agents (16,17,38), or when absorbed onto mica (18). In most cases, the lateral association appears to be loose and irregular, rather than forming a regular lattice as in the microtubule wall.

In the physiological buffer conditions we used here, the FtsZ polymers remained as single protofilaments in solution. This suggests that any lateral associations are too weak to condense the protofilaments into sheets and bundles. When the protofilaments attach to the membrane, however, their effective concentration is enormously enhanced, and even weak binding may be sufficient to promote lateral association. Related to this, Andrews and Arkin (39) presented a generalized treatment for predicting the structure of filaments tethered to the bacterial membrane. A filament with no twist, and planar bending in one direction only, would tend to align in a ring perpendicular to the long axis of the cylinder, which seems to fit with FtsZ. Hörger et al. (40) extended this analysis and showed that lateral association would enhance the tendency to form rings rather than spirals.

FtsZ protofilaments have two curved conformations: a highly curved 23 nm diameter, and an intermediate curved 200 nm diameter (2). Yet when assembled free in solution, under most conditions, protofilaments appear to be straight and relatively rigid, with a persistence length recently measured to be 1.15 μm (4). If a straight protofilament were to bind to the lipid tubule, it would preferentially align parallel to the axis. Yet the protofilament ribbons on the DC8,9PC tubes wrap circularly, mostly perpendicular to the axis, and sometimes at a small helical angle. These protofilaments have apparently switched to a curved conformation.

Little is known about the switch from a straight to a curved conformation (2). In several solution conditions, straight protofilament bundles coexist with toroids (intermediate curved bundles) (17,41). This suggests that they have approximately the same free energy in solution and are separated by a higher-energy transition state. The intermediate curved conformation seems to be enhanced when protofilaments are adsorbed to mica (18,19). Similarly, lateral contacts between protofilaments in bundles may induce the switch to the curved conformation in toroids. (In the study by Turner et al. (4), where all filaments were straight, they were suspended in buffer over holes in the carbon film and made no lateral contact with any surface.) In the case of FtsZ rings on the DC8,9PC tubules, the curved conformation might be induced by the initial tethering to the membrane or after lateral association of protofilaments in the ribbon.

One remarkable feature of our reconstituted FtsZ rings is the constant width of each individual ring. Different rings vary in width from 15 nm to as much as 250 nm, but the width remains constant around each individual ring. This is consistent with the observation by light microscopy that Z rings in cells and liposomes have a relatively constant brightness: when viewed as characteristic two dots on the edges, if the Z ring is bright, both dots are bright, and if it is dim, both dots are dim (2,21). This suggests that nucleation of a new protofilament on the side of a ribbon is a rare event, and that once initiated, elongation of the protofilament is highly favored over additional lateral growth.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Susan Hester for her assistance with the thin-section EM.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant GM66014.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Adams D.W., Errington J. Bacterial cell division: assembly, maintenance and disassembly of the Z ring. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2009;7:642–653. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Erickson H.P., Anderson D.E., Osawa M. FtsZ in bacterial cytokinesis: cytoskeleton and force generator all in one. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2010;74:504–528. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00021-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Romberg L., Simon M., Erickson H.P. Polymerization of Ftsz, a bacterial homolog of tubulin. is assembly cooperative? J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:11743–11753. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009033200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Turner D.J., Portman I., Turner M.S. The mechanics of FtsZ fibers. Biophys. J. 2012;102:731–738. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2012.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ma X., Ehrhardt D.W., Margolin W. Colocalization of cell division proteins FtsZ and FtsA to cytoskeletal structures in living Escherichia coli cells by using green fluorescent protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:12998–13003. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.23.12998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anderson D.E., Gueiros-Filho F.J., Erickson H.P. Assembly dynamics of FtsZ rings in Bacillus subtilis and Escherichia coli and effects of FtsZ-regulating proteins. J. Bacteriol. 2004;186:5775–5781. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.17.5775-5781.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fu G., Huang T., Xiao J. In vivo structure of the E. coli FtsZ-ring revealed by photoactivated localization microscopy (PALM) PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e12682. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Biteen J.S., Goley E.D., Moerner W.E. Three-dimensional super-resolution imaging of the midplane protein FtsZ in live Caulobacter crescentus cells using astigmatism. ChemPhysChem. 2012;13:1007–1012. doi: 10.1002/cphc.201100686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li Z., Trimble M.J., Jensen G.J. The structure of FtsZ filaments in vivo suggests a force-generating role in cell division. EMBO J. 2007;26:4694–4708. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shlomovitz R., Gov N.S. Membrane-mediated interactions drive the condensation and coalescence of FtsZ rings. Phys. Biol. 2009;6:046017. doi: 10.1088/1478-3975/6/4/046017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buske P.J., Levin P.A. The extreme C-terminus of the bacterial cytoskeletal protein FtsZ plays a fundamental role in assembly independent of modulatory proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:10945–10957. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.330324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen Y., Anderson D.E., Erickson H.P. Assembly dynamics of Mycobacterium tuberculosis FtsZ. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:27736–27743. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703788200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lu C., Stricker J., Erickson H.P. FtsZ from Escherichia coli, Azotobacter vinelandii, and Thermotoga maritima—quantitation, GTP hydrolysis, and assembly. Cell Motil. Cytoskeleton. 1998;40:71–86. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0169(1998)40:1<71::AID-CM7>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oliva M.A., Huecas S., Andreu J.M. Assembly of archaeal cell division protein FtsZ and a GTPase-inactive mutant into double-stranded filaments. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:33562–33570. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303798200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Erickson H.P., Taylor D.W., Bramhill D. Bacterial cell division protein FtsZ assembles into protofilament sheets and minirings, structural homologs of tubulin polymers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:519–523. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.1.519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.González J.M., Jiménez M., Rivas G. Essential cell division protein FtsZ assembles into one monomer-thick ribbons under conditions resembling the crowded intracellular environment. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:37664–37671. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305230200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Popp D., Iwasa M., Maéda Y. FtsZ condensates: an in vitro electron microscopy study. Biopolymers. 2009;91:340–350. doi: 10.1002/bip.21136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mingorance J., Tadros M., Vélez M. Visualization of single Escherichia coli FtsZ filament dynamics with atomic force microscopy. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:20909–20914. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503059200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hamon L., Panda D., Pastré D. Mica surface promotes the assembly of cytoskeletal proteins. Langmuir. 2009;25:3331–3335. doi: 10.1021/la8035743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dajkovic A., Lan G., Lutkenhaus J. MinC spatially controls bacterial cytokinesis by antagonizing the scaffolding function of FtsZ. Curr. Biol. 2008;18:235–244. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.01.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Osawa M., Anderson D.E., Erickson H.P. Reconstitution of contractile FtsZ rings in liposomes. Science. 2008;320:792–794. doi: 10.1126/science.1154520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Osawa M., Erickson H.P. Inside-out Z rings—constriction with and without GTP hydrolysis. Mol. Microbiol. 2011;81:571–579. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07716.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yager P., Schoen P.E. Formation of tubules by a polymerizable surfactant. Mol. Cryst. Liq. Cryst. 1984;106:371–381. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yager P., Schoen P.E., Singh A. Structure of lipid tubules formed from a polymerizable lecithin. Biophys. J. 1985;48:899–906. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(85)83852-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mishra B.K., Garrett C.C., Thomas B.N. Phospholipid tubelets. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:4254–4259. doi: 10.1021/ja040191w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Osawa M., Anderson D.E., Erickson H.P. Curved FtsZ protofilaments generate bending forces on liposome membranes. EMBO J. 2009;28:3476–3484. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Osawa M., Erickson H.P. Tubular liposomes with variable permeability for reconstitution of FtsZ rings. Methods Enzymol. 2009;464:3–17. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(09)64001-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thomas B.N., Safinya C.R., Clark N.A. Lipid tubule self-assembly: length dependence on cooling rate through a first-order phase transition. Science. 1995;267:1635–1638. doi: 10.1126/science.267.5204.1635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Burgess S.A., Walker M.L., Knight P.J. Use of negative stain and single-particle image processing to explore dynamic properties of flexible macromolecules. J. Struct. Biol. 2004;147:247–258. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2004.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Georger J.H. Helical and tubular microstructures formed by polymerizable phosphatidylcholines. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1987;109 6169–6165. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lu C., Reedy M., Erickson H.P. Straight and curved conformations of FtsZ are regulated by GTP hydrolysis. J. Bacteriol. 2000;182:164–170. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.1.164-170.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pichoff S., Lutkenhaus J. Tethering the Z ring to the membrane through a conserved membrane targeting sequence in FtsA. Mol. Microbiol. 2005;55:1722–1734. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04522.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Plant A.L., Benson D.M., Trusty G.L. Probing the structure of diacetylenic phospholipid tubules with fluorescent lipophiles. Biophys. J. 1990;57:925–933. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(90)82612-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Diestra E., Fontana J., Risco C. Visualization of proteins in intact cells with a clonable tag for electron microscopy. J. Struct. Biol. 2009;165:157–168. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2008.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schmiedeberg L., Skene P., Bird A. A temporal threshold for formaldehyde crosslinking and fixation. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e4636. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yu X.-C., Margolin W. Ca2+-mediated GTP-dependent dynamic assembly of bacterial cell division protein FtsZ into asters and polymer networks in vitro. EMBO J. 1997;16:5455–5463. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.17.5455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Beuria T.K., Krishnakumar S.S., Panda D. Glutamate-induced assembly of bacterial cell division protein FtsZ. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:3735–3741. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205760200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Popp D., Iwasa M., Robinson R.C. Suprastructures and dynamic properties of Mycobacterium tuberculosis FtsZ. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:11281–11289. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.084079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Andrews S.S., Arkin A.P. A mechanical explanation for cytoskeletal rings and helices in bacteria. Biophys. J. 2007;93:1872–1884. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.102343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hörger I., Velasco E., Tarazona P. FtsZ bacterial cytoskeletal polymers on curved surfaces: the importance of lateral interactions. Biophys. J. 2008;94:L81–L83. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.128363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Srinivasan R., Mishra M., Balasubramanian M.K. The bacterial cell division protein FtsZ assembles into cytoplasmic rings in fission yeast. Genes Dev. 2008;22:1741–1746. doi: 10.1101/gad.1660908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.