Abstract

Recent studies suggest that adult stem cells can cross germ layer boundaries. For example, bone marrow-derived stem cells appear to differentiate into neurons and glial cells, as well as other types of cells. How can stem cells from bone marrow, pancreas, skin, or fat become neurons and glia; in other words, what molecular and cellular events direct mesodermal cells to a neural fate? Transdifferentiation, dediffereniation, and fusion of donor adult stem cells with fully differentiated host cells have been proposed to explain the plasticity of adult stem cells. Here we review the origin of select adult stem cell populations and propose a unifying hypothesis to explain adult stem cell plasticity. In addition, we outline specific experiments to test our hypothesis. We propose that peripheral, tissue-derived, or adult stem cells are all progeny of the neural crest.

INTRODUCTION

Cells arising from a given embryonic germ layer (ectoderm, mesoderm, or endoderm) are committed to germ layer-specific developmental fates (1). Recent studies have called this dogma into question and given rise to the possibility that adult stem cells can cross germ layer boundaries. For example, under certain conditions, bone marrow-derived stem cells appear to differentiate into neurons and glial cells, as well as other types of cells (2,3). How can stem cells from bone marrow, pancreas, skin, or fat become neurons and glia (3–6)? What processes bring mesodermal cells to a neural fate? Transdifferentiation, dediffereniation, and fusion of donor adult stem cells with fully differentiated host cells have been invoked to explain plasticity of adult stem cells, as observed in culture and after transplantation into host mammals (7,8). Here we review the current literature on the origin of adult stem cells and propose a unifying hypothesis that may resolve much of the controversy surrounding adult stem cell plasticity. Also, we outline specific experiments to test our hypothesis. We propose that peripheral, tissue-derived, or adult stem cells are all progeny of the neural crest (NC).

What are NC cells?

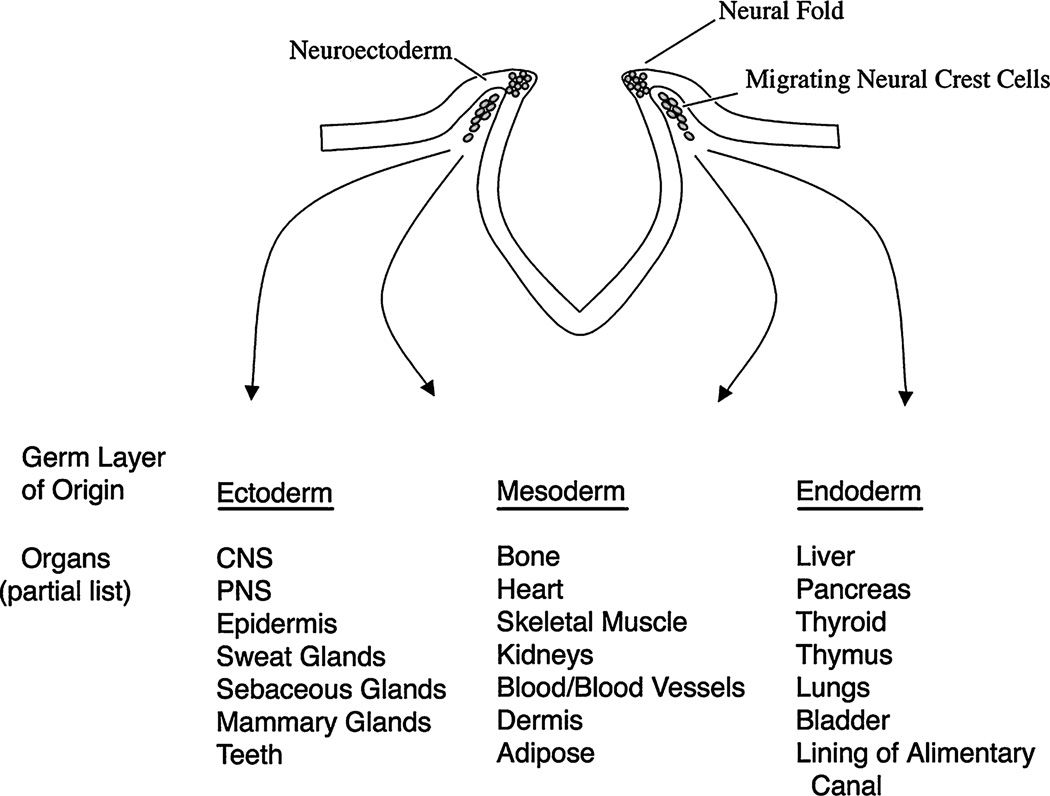

NC forms during the neural plate stage in the developing vertebrate embryo at the junction between epidermal ectoderm and presumptive neural ectoderm. Therefore, in the early vertebrate embryo, NC cells can first be found at the dorsal lip of the developing neuroectoderm. As development progresses, they migrate from the lateral margins of the neural tube and contribute to virtually every organ of the vertebrate body (Fig. 1) (9–12,47).

FIG. 1.

Cells from the NC contribute across germ layers to many organs of the vertebrate body. NC cells are found early in development migrating from the dorsal lip of the developing neuroectoderm, shown here at the neural-fold stage. During development, NC cells populate a host of organs in the body derived from ectoderm, mesoderm, or endoderm. The diverse migration of NC cells provides an opportunity for them to contribute to adult stem cell populations found in many of these organs.

Abbreviations: CNS, central nervous system; PNS, peripheral nervous system.

This figure is adapted from Fig. 1 of Trainor et al. (11) and Fig. 1 (bottom) of Trainor and Krumlauf (47).

NC cells are pluripotent (10,11), and it has been proposed that this pluripotency is modified during migration to their final destination (13). Our hypothesis suggests that plasticity exhibited by NC derivatives and the widespread distribution of their progeny in the vertebrate body implicate NC as the source for adult stem or progenitor cells.

Are all peripheral, adult stem, or progenitor cells NC progeny?

An analysis of several known adult stem or progenitor cell populations provides support for a NC origin. Table 1 compares published results with the stated hypothesis for several adult stem and progenitor cell populations.

Table 1.

Stem or Progenitor Cell Population

| Criterion | SKPs | Cardiac progenitors |

Hematopoietic progenitors |

Skeletal muscle/satellite cells |

PMPs | Islet enriched |

Others (adipose/umbilicus/ Wharton’s jelly) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lineage trace | X | X | |||||

| Markers | |||||||

| Slug | X | X | X | ||||

| Snail | X | X | X | ||||

| Twist | X | X | |||||

| Wnt-1 | X | ||||||

| Musashi-1 | X | ||||||

| Pax-3 | X | X | X | ||||

| Pax-7 | X | ||||||

| Sox-9 | X | ||||||

| Sox-10 | X | ||||||

| Nestin | X | X | X | ||||

| p75 | X | X | |||||

| Retained alternative fates | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| NC contribution to organ | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Citation | (4, 14–16) | (17–20) | (21–23) | (11, 28, 30–33) | (5) | (34) | (35–48, 40, 46) |

Perhaps the system that best addresses these questions and has the most complete evidence in support of our hypothesis is the skin-derived progenitor cells, or SKPs (14). The SKPs can be isolated from hair follicles, where they are found in a unique stem cell niche (4). NC cells with β-galactosidase expression driven by the Wnt-1 promoter were used in a lineage study to demonstrate a NC origin for SKPs (15). The conclusion that SKPs are derived from NC is also supported by their expression of NC markers, including, Sox-9, Pax-3, Slug, Snail, Twist, and Nestin (4). Consistent with these results, NCs populate a dermal niche (15) and can differentiate into melanoblasts, smooth muscle cells, neurons, Schwann cells, and chondrocytes (15,16). Therefore, the origin of SKPs can be traced to NC, they express a compliment of NC markers, they are in an area populated by derivatives of the NC, and they are capable of what we refer to here as retained alternative fates (see below).

Lineage studies show a NC contribution to the heart (17), and adult cardiac muscle progenitors are derived from NC. In addition, expression of Pax-3 accompanies migration of these NC cells to the cardiac outflow tract (18). In fact, an outflow tract progenitor cell population may contribute to the cells found throughout heart (19), and recently a population of cardiac progenitors was found in the heart that expresses the NC markers Nestin, Musashi-1, and p75. These cells can contribute to smooth muscle of blood vessels and the peripheral nervous system (PNS). Also, when transplanted into the chick neural tube, they migrate along the NC dorsolateral pathway to the cardiac outflow tract (20).

The cardiac outflow tract is linked to another important stem cell population, bone marrow-derived stem cells. Hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) originate within the dorsal aorta and the surrounding mesenchyme of the mouse embryonic day-11 aorta–gonad–mesonephros (AGM) (21), an area that receives a major complement of NC cells. Also, other cells of the bone marrow can be linked to the NC, such as a circulating mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) of NC origin (22–24). Bone marrow-derived HSCs and MSCs are capable of differentiation into neural fates (25,26). In fact, a recent report demonstrates that HSCs can produce neural stem cells (27).

Some skeletal muscles arise from NC during embryonic development, and others may harbor stem or progenitor cell populations with NC origin into adulthood. In the craniofacial region, muscle can be found derived directly from NC cells (11). Adult stem or progenitor cell populations for skeletal muscle found throughout the body may be derived from NC, including satellite cells and nonsatellite cell myogenic progenitors. First, satellite cells, defined positionally as sublaminar cells and functionally as myogenic progenitors, can be isolated routinely from muscle fibers (28,29). Marker expression most often linked with satellite cells includes the NC marker Pax 3/7 (28,30). Satellite cells exhibit myogenic, osteogenic, and adipogenic differentiation (31), and nonsatellite cell myogenic progenitors differentiate into myofibers, endothelial cells, neurons, and Schwann cells (32,33).

Although controversy exists regarding the developmental source of stem or progenitor cells in the pancreas, we propose that the evidence supports a NC origin. An analysis of a heterogeneous population of cells isolated from pancreatic islets suggests a link to NC based first on marker expression (34). Furthermore, these cells can be driven toward fates consistent with a neuroectodermal origin. However, van der Kooy and colleagues (5) describe a clonal population of pancreatic multipotent precursors and conclude they are not progeny of NC because the precursors do not express the known NC markers Pax-3, Twist, Wnt-1, and Sox-10. Nonetheless, these cells express a subset of NC markers, including Snail, Slug, and p75 and can generate neurons (5). We maintain that persistent expression of subsets of NC markers is suggestive of a NC origin. The expression of Snail and Slug is consistent with the known transition from an epithelial to mesenchymal cell-type that precedes NC cell migration.

There are numerous examples that support a neural link for adult stem or progenitor cells such as progenitor populations from adipose tissue (35), umbilical cord blood (36), Wharton’s jelly (37), and deciduous teeth (38). All of these stem or progenitor cells appear able to differentiate into neurons. Moreover, support for a common origin of many adult stem or progenitor cells can be found in cases where systemic effects are monitored following changes in gene expression that may be related to NC. For example, Slug knockout mice show impaired hematopoiesis and pigmentation deficiencies (39). Also, some cases of human piebaldism, characterized by congenital depigmentated patches of skin, are associated with mutations of Slug (40), and it is suggested (40) that piebaldism in these cases results from a deficiency in Slug function during NC development.

Neural stem or progenitor cell populations found in the central nervous system (CNS) (41) may be related to the cell populations described here. However, due to the overlap in timing during early development of primordial brain and NC, a method of identification of a unique stem cell population for CNS neural stem cells is not addressed by our current hypothesis.

Testing our hypothesis

To assert that identified adult stem or progenitor cell populations originate in NC, one should define criteria for the proof of principle, and each cell population should be tested in a reproducible manner using these criteria.

We propose the following conditions to establish a NC origin for adult stem or progenitor cells.

If adult stem or progenitor cells are of NC origin, they can be traced with an appropriate lineage tracking system. A direct lineage trace between the NC and adult stem or progenitor cells in a particular tissue is the most definitive method for testing our hypothesis. In modern lineage studies, promoter-specific, fate-independent marker expression can be used to trace the developmental outcome of any cell. One such method specific for NC is the Wnt-1-Cre/R26R transgenic system, which links early Wnt-1 promoter activity, considered to be specific to NC, with persistent ROSA26 expression (42). Upon activation of Cre recombinase by early Wnt-1 expression, persistent β-galactosidase activity is maintained in all progeny. Theoretically, this makes it possible to achieve an accurate lineage trace of all NC descendents.

Adult stem or progenitor cells of NC origin will retain a ‘marker history’. A partial list of NC-related markers includes Slug, Snail, Twist, Wnt-1, Musashi-1, Pax-3, Pax-7, Sox-9, Sox-10, Nestin, and p75 (4,5,11,20,34). Expression of these markers may denote NC origin. However, by no means should marker expression alone be left as proof of NC origin, nor should absence of a given marker be taken as evidence to exclude a cell population as being of NC derivation. For example, the transcription factors Slug and Snail may be down-regulated at the end of NC migration and entry into an adult stem cell niche.

Adult stem or progenitor cells of NC origin display “retained alternative fates.” Transdifferentiation describes a cell fate inconsistent with the germ layer of origin. If it is shown that adult stem or progenitor cells originate in NC, the ability to differentiate into neural and other cell types may be retained. Rather than transdifferentiation or dedifferentiation, we propose that adult stem or progenitor cell populations contain cells, derived from NC, and are capable of achieving alternative fates. For example, bone marrow cells can become neural cells. We propose that this is due to a neuroectodermal origin of the stem or progenitor cells contained within the bone marrow.

We propose that all peripheral adult stem or progenitor cells have a NC origin. Newly described and previously reported populations of stem or progenitor cells should be assessed for NC origin using the criteria described above.

What are the ramifications of this hypothesis?

First, it provides an explanation for the plasticity exhibited by adult stem or progenitor cells. Pluripotent cells of the NC escape the basal lamina, become mesenchymal, and migrate to peripheral tissue, where their progeny are found throughout the body in all adult vertebrates. The presence of NC-derived cells in so many tissues begs an explanation for the question: What selective advantage have NC cells bestowed upon the vertebrates? One proposal is that NC is the source of cells for tissue regeneration in vertebrates (43), and a goal of stem cell research is the regeneration of tissues lost to disease or injury. An understanding of the plasticity of potential donor stem or progenitor cells is important to determine the therapeutic value of a given cell type.

Second, if all adult stem or progenitor cell populations originate in the NC, then any accessible adult stem cell population might be able to be used for transplant needs. For example, a strong case can be made for bone marrow stem cell transplants to replace neural cells if, as we propose, they share a neuroectodermal origin. Recent studies indicate that in some examples of neural disorders, bone marrow stem cell implants are useful as a cell-based therapy (44,45). The use of easily accessible and apparently pluripotent adult stem cells may eventually supplant the need for embryonic or fetal cells in clinical applications.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Fiona Asigbee and Dr. Jason Meyer for their help with the literature search and constructive discussions. We also thank Dr. Dawn Cornelison, University of Missouri-Columbia, for critiquing the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lawson KA. Fate mapping the mouse embryo. Int J Dev Biol. 1999;43:773–775. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jin K, Mao XO, Batteur S, Sun Y, Greenberg DA. Induction of neuronal markers in bone marrow cells: differential effects of growth factors and patterns of intracellular expression. Exp Neurol. 2003;184:78–89. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4886(03)00133-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cogle CR, Yachnis AT, Laywell ED, Zander DS, Wingard JR, Steindler DA, Scott EW. Bone marrow transdifferentiation in brain after transplantation: a retrospective study. Lancet. 2004;363:1432–1437. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16102-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fernandes KJ, McKenzie IA, Mill P, Smith KM, Akhavan M, Barnabe-Heider F, Biernaskie J, Junek A, Kobayashi NR, Toma JG, et al. A dermal niche for multipotent adult skin-derived precursor cells. Nature Cell Biol. 2004;6:1082–1093. doi: 10.1038/ncb1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Seaberg RM, Smukler SR, Kieffer TJ, Enikolopov G, Asghar Z, Wheeler MB, Korbutt G, van der Kooy D. Clonal identification of multipotent precursors from adult mouse pancreas that generate neural and pancreatic lineages. Nature Biotechnol. 2004;22:1115–1124. doi: 10.1038/nbt1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Safford KM, Rice HE. Stem cell therapy for neurologic disorders: therapeutic potential of adipose-derived stem cells. Curr Drug Targets. 2005;6:57–62. doi: 10.2174/1389450053345028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weimann JM, Johansson CB, Trejo A, Blau HM. Stable reprogrammed heterokaryons form spontaneously in Purkinje neurons after bone marrow transplant. Nature Cell Biol. 2003;5:959–966. doi: 10.1038/ncb1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Corti S, Locatelli F, Papadimitriou D, Strazzer S, Bonato S, Comi GP. Nuclear reprogramming and adult stem cell potential. Histol Histopathol. 2005;20:977–986. doi: 10.14670/HH-20.977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.LaBonne C, Bronner-Fraser M. Molecular mechanisms of neural crest formation. Ann Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1999;15:81–112. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.15.1.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Le Douarin NM, Creuzet S, Couly G, Dupin E. Neural crest cell plasticity and its limits. Development. 2004;131:4637–4650. doi: 10.1242/dev.01350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Trainor PA, Melton KR, Manzanares M. Origins and plasticity of neural crest cells and their roles in jaw and craniofacial evolution. Int J Dev Biol. 2003;47:541–553. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gilbert SF. Developmental Biology. 7th ed. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates, Inc; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Trentin A, Glavieux-Pardanaud C, Le Douarin NM, Dupin E. Self-renewal capacity is a widespread property of various types of neural crest precursor cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:4495–4500. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400629101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fuchs E, Tumbar T, Guasch G. Socializing with the neighbors: stem cells and their niche. Cell. 2004;116:769–778. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00255-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sieber-Blum M, Grim M, Hu YF, Szeder V. Pluripotent neural crest stem cells in the adult hair follicle. Dev Dyn. 2004;231:258–269. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Toma JG, McKenzie IA, Bagli D, Miller FD. Isolation and characterization of multipotent skin-derived precursors from human skin. Stem Cells. 2005;23:727–737. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2004-0134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaartinen V, Dudas M, Nagy A, Sridurongrit S, Lu MM, Epstein JA. Cardiac outflow tract defects in mice lacking ALK2 in neural crest cells. Development. 2004;131:3481–3490. doi: 10.1242/dev.01214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chan WY, Cheung CS, Yung KM, Copp AJ. Cardiac neural crest of the mouse embryo: axial level of origin, migratory pathway and cell autonomy of the splotch (Sp2H) mutant effect. Development. 2004;131:3367–3379. doi: 10.1242/dev.01197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cai CL, Liang X, Shi Y, Chu PH, Pfaff SL, Chen J, Evans S. Isl1 identifies a cardiac progenitor population that proliferates prior to differentiation and contributes a majority of cells to the heart. Dev Cell. 2003;5:877–889. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00363-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tomita Y, Matsumura K, Wakamatsu Y, Matsuzaki Y, Shibuya I, Kawaguchi H, Ieda M, Kanakubo S, Shimazaki T, Ogawa S, et al. Cardiac neural crest cells contribute to the dormant multipotent stem cell in the mammalian heart. J Cell Biol. 2005;170:1135–1146. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200504061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.de Bruijn MF, Speck NA, Peeters MC, Dzierzak E. Definitive hematopoietic stem cells first develop within the major arterial regions of the mouse embryo. EMBO J. 2000;19:2465–2474. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.11.2465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Labat ML, Milhaud G, Pouchelet M, Boireau P. On the track of a human circulating mesenchymal stem cell of neural crest origin. Biomed Pharmacother. 2000;54:146–162. doi: 10.1016/S0753-3322(00)89048-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Milhaud G. A human pluripotent stem cell in the blood of adults: towards a new cellular therapy for tissue repair. Bull Acad Natl Med. 2001;185:567–577. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.De Angelis L, Berghella L, Coletta M, Lattanzi L, Zanchi M, Cusella-De Angelis MG, Ponzetto C, Cossu G. Skeletal myogenic progenitors originating from embryonic dorsal aorta coexpress endothelial and myogenic markers and contribute to postnatal muscle growth and regeneration. J Cell Biol. 1999;147:869–878. doi: 10.1083/jcb.147.4.869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sigurjonsson OE, Perreault MC, Egeland T, Glover JC. Adult human hematopoietic stem cells produce neurons efficiently in the regenerating chicken embryo spinal cord. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:5227–5232. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501029102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bossolasco P, Cova L, Calzarossa C, Rimoldi SG, Borsotti C, Deliliers GL, Silani V, Soligo D, Polli E. Neuro-glial differentiation of human bone marrow stem cells in vitro. Exp Neurol. 2005;193:312–325. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2004.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bonilla S, Silva A, Valdes L, Geijo E, Garcia-Verdugo JM, Martinez S. Functional neural stem cells derived from adult bone marrow. Neuroscience. 2005;133:85–95. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Relaix F, Rocancourt D, Mansouri A, Buckingham M. A Pax3/Pax7-dependent population of skeletal muscle progenitor cells. Nature. 2005;435:948–953. doi: 10.1038/nature03594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bischoff R. Proliferation of muscle satellite cells on intact myofibers in culture. Dev Biol. 1986;115:129–139. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(86)90234-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gros J, Manceau M, Thome V, Marcelle C. A common somitic origin for embryonic muscle progenitors and satellite cells. Nature. 2005;435:954–958. doi: 10.1038/nature03572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Asakura A, Komaki M, Rudnicki M. Muscle satellite cells are multipotential stem cells that exhibit myogenic, osteogenic adipogenic differentiation. Differentiation. 2001;68:245–253. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-0436.2001.680412.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Qu-Petersen Z, Deasy B, Jankowski R, Ikezawa M, Cummins J, Pruchnic R, Mytinger J, Cao B, Gates C, Wernig A, et al. Identification of a novel population of muscle stem cells in mice: potential for muscle regeneration. J Cell Biol. 2002;157:851–864. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200108150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alessandri G, Pagano S, Bez A, Benetti A, Pozzi S, Iannolo G, Baronio M, Invernici G, Caruso A, Muneretto C, et al. Isolation and culture of human muscle-derived stem cells able to differentiate into myogenic and neurogenic cell lineages. Lancet. 2004;364:1872–1883. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17443-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Choi Y, Ta M, Atouf F, Lumelsky N. Adult pancreas generates multipotent stem cells and pancreatic and nonpancreatic progeny. Stem Cells. 2004;22:1070–1084. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.22-6-1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fujimura J, Ogawa R, Mizuno H, Fukunaga Y, Suzuki H. Neural differentiation of adipose-derived stem cells isolated from GFP transgenic mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;333:116–121. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.05.096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goodwin HS, Bicknese AR, Chien SN, Bogucki BD, Quinn CO, Wall DA. Multilineage differentiation activity by cells isolated from umbilical cord blood: expression of bone fat neural markers. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2001;7:581–588. doi: 10.1053/bbmt.2001.v7.pm11760145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mitchell KE, Weiss ML, Mitchell BM, Martin P, Davis D, Morales L, Helwig B, Beerenstrauch M, Abou-Easa K, Hildreth T, et al. Matrix cells from Wharton’s jelly form neurons and glia. Stem Cells. 2003;21:50–60. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.21-1-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miura M, Gronthos S, Zhao M, Lu B, Fisher LW, Robey PG, Shi S. SHED: stem cells from human exfoliated deciduous teeth. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:5807–5812. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0937635100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Perez-Losada J, Sanchez-Martin M, Rodriguez-Garcia A, Sanchez ML, Orfao A, Flores T, Sanchez-Garcia I. Zinc-finger transcription factor Slug contributes to the function of the stem cell factor c-kit signaling pathway. Blood. 2002;100:1274–1286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sanchez-Martin M, Perez-Losada J, Rodriguez-Garcia A, Gonzalez-Sanchez B, Korf BR, Kuster W, Moss C, Spritz RA, Sanchez-Garcia I. Deletion of the SLUG (SNAI2) gene results in human piebaldism. Am J Med Genet A. 2003;122:125–132. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.20345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Alvarez-Buylla A, Lim DA. For the long run: maintaining germinal niches in the adult brain. Neuron. 2004;41:683–686. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00111-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jiang X, Rowitch DH, Soriano P, McMahon AP, Sucov HM. Fate of the mammalian cardiac neural crest. Development. 2000;127:1607–1616. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.8.1607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Baranowitz SA. Regeneration, neural crest derivatives and retinoids: a new synthesis. J Theor Biol. 1989;140:231–242. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5193(89)80131-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fernandez CI, Alberti E, Mendoza Y, Martinez L, Collazo J, Rosillo JC, Bauza JY. Motor and cognitive recovery induced by bone marrow stem cells grafted to striatum and hippocampus of impaired aged rats: functional and therapeutic considerations. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2004;1019:48–52. doi: 10.1196/annals.1297.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lu P, Jones LL, Tuszynski MH. BDNF-expressing marrow stromal cells support extensive axonal growth at sites of spinal cord injury. Exp Neurol. 2005;191:344–360. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2004.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Eferl R. Functions of c-Jun in liver and heart development. J Cell Biol. 1999;145:1049–1061. doi: 10.1083/jcb.145.5.1049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Trainor P, Krumlauf R. Development. Riding the crest of the Wnt signaling wave. Science. 2002;297:781–783. doi: 10.1126/science.1075454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]