Thiamine is a water-soluble vitamin that plays a pivotal role in carbohydrate metabolism. In acute deficiency, pyruvate accumulates and is metabolized to lactate, and chronic deficiency may cause polyneuropathy and Wernicke encephalopathy. Classic symptoms include mental status change, ophthalmoplegia, and ataxia but are present in only a few patients [1]. Critically ill patients are prone to thiamine deficiency because of preexistent malnutrition, increased consumption in high-carbohydrate nutrition, and accelerated clearance in renal replacement. In retrospective [2] and prospective [3,4] studies, a substantial prevalence of thiamine deficiency has been described in both adult (10% to 20%) and pediatric (28%) patients. Thiamine deficiency may become clinically evident in any type of malnutrition that outlasts thiamine body stores (2 to 3 weeks), including alcoholism, bariatric surgery, or hyperemesis gravidarum, and results in high morbidity and mortality if untreated [1].

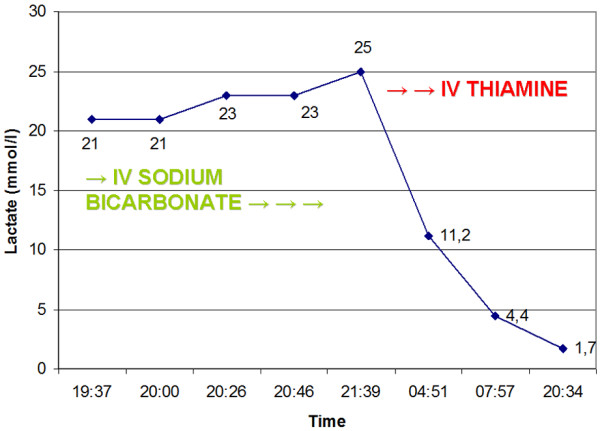

We report the case of a 56-year-old man with profound lactic acidosis that resolved rapidly after thiamine infusion. He was admitted because of a decreased level of consciousness (Glasgow Coma Scale score of 6). Vital signs, including blood pressure, heart rate, and oxygen saturation, were normal. Besides reporting regular alcohol consumption, relatives reported recent progressive weakness and 5-kg weight loss. Laboratory findings on admission were remarkable for moderate hypoglycemia and metabolic acidosis - pH of 6.87, base excess of -29.5, partial pressure of carbon dioxide (pCO2) of 14 mm Hg - with a high anion gap (37 mmol/L) that was attributed to severe hyperlactatemia (21 mmol/L). After intravenous glucose administration, the patient was transferred to the intensive care unit, where he received sodium bicarbonate and 1,500 mL of lactate-free isotonic crystalloids. Within the next few hours, lactate levels increased further while pH slowly improved. Clinically, thiamine deficiency was suspected after other causes of hyperlactatemia, such as hypoxia and hepatic failure, were excluded. After administration of 300 mg of intravenous thiamine, hyperlactatemia normalized rapidly (Figure 1). Unfortunately, the patient suffered persistent neurocognitive deficits.

Figure 1.

Lactate levels during the first 24 hours. IV, intravenous.

Thiamine deficiency may cause unspecific neurologic symptoms. Glucose administration or feeding may aggravate depletion. Thiamine deficiency is an underdiagnosed cause of lactic acidosis, although treatment is safe, inexpensive, and readily available. Current guidelines on parenteral nutrition recommend a daily intravenous dose of 100 to 300 mg of thiamine during the first 3 days in the intensive care unit when deficiency is a possibility (grade B) [5]. In conclusion, although its clinical significance has been known for decades, thiamine deficiency remains an under-recognized condition. Intensivists should have an increased awareness of this problem and a low threshold to infuse high-dose thiamine. Future prospective studies to define the optimal dose and duration of treatment are warranted.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests and that the data presented have not been published previously, except in abstract form.

Contributor Information

Karin Amrein, Email: karin.amrein@yahoo.de.

Werner Ribitsch, Email: werner.ribitsch@medunigraz.at.

Ronald Otto, Email: Ronald.Otto@medunigraz.at.

Harald C Worm, Email: harald.worm@aon.at.

Rudolf E Stauber, Email: rudolf.stauber@medunigraz.at.

Acknowledgements

We thank Steven Amrein for critical review of the manuscript.

References

- Sechi G, Serra A. Wernicke's encephalopathy: new clinical settings and recent advances in diagnosis and management. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6:442–455. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70104-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruickshank AM, Telfer AB, Shenkin A. Thiamine deficiency in the critically ill. Intensive Care Med. 1988;14:384–387. doi: 10.1007/BF00262893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lima LF, Leite HP, Taddei JA. Low blood thiamine concentrations in children upon admission to the intensive care unit: risk factors and prognostic significance. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;93:57–61. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.29078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnino MW, Carney E, Cocchi MN, Barbash I, Chase M, Joyce N, Chou PP, Ngo L. Thiamine deficiency in critically ill patients with sepsis. J Crit Care. 2010;25:576–581. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2010.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer P, Berger MM, Van den Berghe G, Biolo G, Calder P, Forbes A, Griffiths R, Kreyman G, Leverve X, Pichard C. ESPEN. ESPEN Guidelines on Parenteral Nutrition: intensive care. Clin Nutr. 2009;28:387–400. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2009.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]