Abstract

The equine herpesvirus 1 (EHV-1) negative regulatory IR2 protein (IR2P), an early 1,165-amino acid (aa) truncated form of the 1,487-aa immediate-early protein (IEP), lacks the trans-activation domain essential for IEP activation functions but retains domains for binding DNA, TFIIB, and TBP and the nuclear localization signal. IR2P mutants of the N-terminal region which lack either DNA-binding activity or TFIIB-binding activity were unable to down-regulate EHV-1 promoters. In EHV-1-infected cells expressing full-length IR2P, transcription and protein expression of viral regulatory IE, early EICP0, IR4, and UL5, and late ETIF genes were dramatically inhibited. Viral DNA levels were reduced to 2.1% of control infected cells, but were vey weakly affected in cells that express the N-terminal 706 residues of IR2P. These results suggest that IR2P function requires the two N-terminal domains for binding DNA and TFIIB as well as the C-terminal residues 707 to 1116 containing the TBP-binding domain.

Keywords: Equine herpesvirus 1, IR2 protein, immediate-early protein, transcription down-regulation, DNA-binding domain, TFIIB-binding domain, replication inhibition, IR2P-expressing Vero cell lines

Introduction

Equine herpesvirus 1 (EHV-1), an alphaherpesvirus, is a major pathogen of equines, causing respiratory disease, neurological disorders, and spontaneous abortions in pregnant mares (Allen and Bryans, 1986; O'Callaghan et al., 1983; O'Callaghan and Osterrieder, 1999). The EHV-1 genome is comprised of 78 genes that are temporally expressed as immediate-early (IE), early, and late (Caughman et al., 1985; Gray et al., 1987a, 1987b). The coordinated transcription of EHV-1 genes is regulated by seven regulatory molecules: the sole IE protein (IEP), four early proteins [IR2P, IR4P (HSV-1 ICP22 homolog), UL5P (HSV-1 ICP27 homolog), and EICP0P (HSV-1 ICP0 homolog)], the late ETIF protein (HSV-1 αTIF homolog), and the late IR3 RNA (Ahn et al., 2007, 2010; Bowles et al., 1997, 2000; Caughman et al., 1985; Harty and O'Callaghan, 1991; Holden et al., 1992, 1994, 1995; Kim et al., 2006; Kim and O'Callaghan, 2001; Smith et al., 1992; Zhao et al., 1995).

The sole IE gene is expressed as a spliced 6-kb transcript that encodes the 1,487-aa IE protein (Harty and O'Callaghan, 1991). IEP activates transcription from early and some late viral promoters (Smith et al., 1992, 1995) and is essential for viral replication (Garko-Buczynski et al., 1998). Conversely, it down-regulates its own promoter (Kim et al., 1995; Smith et al., 1992) and the true late glycoprotein K (gK) promoter (Kim et al., 1999) by binding its cognate consensus sequence ATCGT, which overlaps the transcription initiation site of these two promoters. IEP possesses several domains essential for trans-activation including: (i) an acidic trans-activation domain (TAD; aa 3-89); (ii) a serine-rich tract (SRT; aa 181-220) that binds to the cellular protein EAP; (iii) a nuclear localization signal (NLS; aa 963-970); (iv) a DNA-binding domain (DBD; aa 422- 597); and (v) a TFIIB-binding domain (aa 407-757) (Albrecht et al., 2003; Buczynski et al., 1999, 2005; Jang et al., 2001; Kim et al., 1995, 2001; Smith et al., 1994, 1995).

The IR2 protein which is unique to EHV-1 is encoded by the IR2 gene that lies within the IE gene and is a truncated form (aa323-1,487) of the IEP (Caughman et al., 1995; Harty and O'Callaghan, 1991). Therefore, it lacks the TAD and SRT domains of the IEP but retains binding domains for DNA, TFIIB, and TBP, and the NLS. In transient transfection assays, the IR2P down-regulated luciferase reporter activity that was under the control of the sole IE promoter or early viral promoters such as EICP0, TK, IR4, and UL5 in a dose-dependent manner (Kim et al., 2006). In comparison to the IE protein, IR2P is expressed at a low level at the early stage of infection because its promoter is weak (Kim et al., 2006). Therefore, IR2P may not completely block viral gene expression in lytic infection, but instead, may function to reduce the production of IEP and early regulatory proteins and thereby favor the transition to the expression of late viral proteins required for the assembly of daughter virions.

To identify IR2P residues that mediate its negative regulatory activity, functional domains of IR2P were characterized by use of panels of IR2P deletion and point mutants and cell lines that express full-length or partial forms of IR2P. Overall, our results suggest that the negative regulatory function of IR2P requires both the DNA-binding and TFIIB-binding activities and that the IR2P domain(s) necessary for inhibition of EHV-1 replication lie within C-terminal aa 707 to 1116.

Results

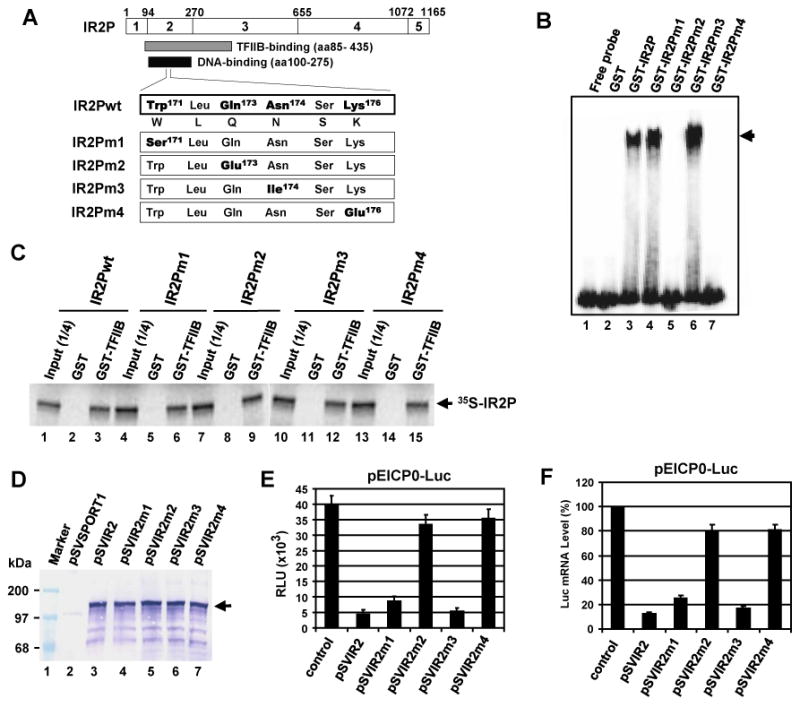

The Gln173 and Lys176 residues of the IR2P WLQN region are important for its DNA binding activity

Our previous transient tranfection assays showed that the IR2P residues 1 to 706 which contain the DBD (aa100-275), TFIIB-binding domain (aa86-435), and NLS (aa641-648) are important for negative regulatory activity (Kim et al., 2006). The WLQN region is highly conserved within alphaherpesvirus ICP4 homologs and directly involved in the DNA binding interaction (Tyler et al., 1994). Mutagenesis analysis of the WLQN region (IEPaa493-498; IR2P aa171-176) of the IEP indicated that Gln495 (IR2P Gln173) and Lys498 (IR2P Lys176) residues are important for the DNA binding activity (Kim et al., 1997). To investigate whether the DNA binding activity of IR2P is necessary for negative regulation, residues Trp171, Gln173, Asn174, and Lys176 of the WLQN region were replaced with Ser (IR2PW171S; IR2Pm1), Glu (IR2PQ173E; IR2Pm1), Ile (IR2PN174I; IR2Pm1), and Glu (IR2PK176E; IR2Pm1), respectively (Fig. 1A). The four IR2 mutants were confirmed by DNA sequencing (data not shown). IR2P binds to its cognate consensus sequence ATCGT of the EHV-1 promoters (Albrecht et al., 2005; Kim et al., 1995). To investigate whether the four IR2P mutants bind to DNA, we carried out gel shift assays in which each IR2P mutant synthesized as a GST fusion protein was examined for the ability to bind to radiolabeled IE promoter DNA (Fig. 1B). GST-wild-type (wt) IR2P and four GST-IR2P mutants were expressed and purified as described in the Material and Methods (data not shown). GST-wt IR2P, GST-IR2Pm1, and GST-IR2Pm3 bound to the IE promoter DNA (Fig. 1B, lanes 3, 4, and 6, respectively). The formation of the GST-IR2P-IE promoter DNA complex was completely blocked by addition of unlabeled excess competitor IE promoter DNA (data not shown). In contrast, GST-IR2Pm2 and GST-IR2Pm4 failed to bind to the IE DNA (Fig. 1B, lanes 5 and 7, respectively), indicating that the Gln173 and Lys176 residues of the WLQN region are important for the DNA binding activity of IR2P.

Fig. 1.

Gln173 and Lys176 of the WLQN region are important for the DNA-binding activity as well as negative regulation. (A) Site-directed mutagenesis of IR2P DNA-binding domain motif. The top diagram represents the 1,165-aa IR2P which has been divided into four regions (regions 2 to 5; Grundy et al., 1989; Kim et al., 1995). The numbers refer to the number of amino acids from the N-terminus of IR2P. The numbers refer to the number of amino acids from the N-terminus of IR2P. The residues Trp171, Gln173, Asn174, and Lys176 of the WLQN region of IR2P were replaced with Ser (IR2Pm1), Glu (IR2Pm2), Ile (IR2Pm3), and Glu (IR2Pm4), respectively. wt, wild-type. (B) The DNA-binding activity of IR2P mutants was determined by the gel mobility shift assay. The radiolabeled probe of the IE promoter region (position -16 to +22) was incubated with 100 ng of the purified GST, GST-wtIR2P, or GST-IR2P mutants. The position of complex formed by GST-IR2P is indicated with an arrow. (C) IR2P DNA-binding domain mutants interact with TFIIB. Equal amounts of radiolabeled IR2P mutants were incubated with GST or GST-TFIIB fusion and then precipitated with glutathione-Sepharose 4B beads. The precipitated pellets were resolved on SDS-7.5% PAGE gels. The bands were quantitated by PhosphorImager analysis. Marker lane: The numbers on the left represent 14C-methylated protein markers in kilodaltons. (D) The expression of IR2P mutants was determined by western blot analysis. L-M cells were transfected with 1.5 pmol of wt or mutant IR2P expression vectors. The cell lysates were extracted at 40 h after transfection, and then IR2P was detected with an anti-IEP polyclonal antibody (pAb) OC33 (Harty and O'Callaghan, 1991). The position of IR2P is indicated with an arrow. Measurement of relative firefly luciferase signal (E) and mRNA level (F). L-M cells were co-transfected with 0.12 pmol of the reporter plasmid pEICP0-Luc and 0.08 pmol of effector plasmids (control vector pSVSPORT, pSVIR2, and mutant plasmids). Reporter plasmid pICP22-SEAP which was very weakly affected by IR2P (data not shown) was used to assess transfection efficiency. The firefly luciferase signals were normalized to the internal secreted alkaline phosphatase (SEAP) transfection control. The firefly luciferase mRNA levels were measured by RT-PCR and normalized to the level for the control vector pSVSPORT1. Data are averages and are representative of three or more independent experiments. Error bars show standard deviations. RLU, relative luminescence units.

To investigate whether the four IR2P mutants interact with TFIIB, we performed GST-pulldown assays. WT IR2P(1-1165) and four mutants within WLQN region IR2P(1-1165)m1, IR2P(1-1165)m2, IR2P(1-1165)m3, and IR2P(1-1165)m4 were expressed by in vitro transcription/translation (IVTT) reactions. As expected, GST-TFIIB precipitated wt 35S-IR2P(1-1165), which harbors the TFIIB-binding domain (aa86-438) (Fig. 1C, lane 4), whereas GST alone did not (Fig 1C, lane 3). GST-TFIIBΔ125-174 which lacks the domain for binding to IR2P (Albrecht et al., 2003) was not able to precipitate wild-type 35S-IR2P(1-1165), indicating that TFIIB specifically interacts with IR2P(1-1165). GST-TFIIB precipitated all of the radiolabeled 35S-IR2P mutants (Fig. 1C, lanes 7, 10, 13, 16), whereas GST alone did not (Fig 1C, lanes 6, 9, 12, 15). Taken together, these results showed that the two mutants in Gln173 or Lys176 lost their DNA binding activity without affecting TFIIB-binding ability.

The DNA binding activity of the IR2P is necessary for negative regulation

The four IR2P mutants were expressed under the control of the simian virus 40 (SV40) promoter in mouse fibroblast L-M cells and confirmed by western blot analysis (Fig. 1D). In luciferase reporter assays, the two IR2P with mutations expressed in Trp171 (IR2Pm1) and Asn174 (IR2Pm3) down-regulated the EICP0 promoter by 65% and 91%, respectively, of the inhibitory activity of the wild-type (wt) IR2P (Fig. 1E, bars 3 and 5, respectively). However, the two DNA-binding mutants IR2Pm2 (Gln173) and IR2Pm4 (Lys176) lost most of their inhibitory activity of the EICP0 promoter (Fig. 1E, bars 4 and 6, respectively). IR2Pm2 and IR2Pm4 very weakly down-regulated the IE and early UL5 promoters by only 5% to 17% of the inhibitory activity of the wt IR2P (data not shown). Firefly luciferase mRNA level was measured by RT-PCR in L-M cells cotransfected with the luciferase reporter and effector plasmids. Expression of wt IR2P led to a dramatic decrease (86%) in the amount of luciferase mRNA (Fig. 1E, bar 2). However, IR2Pm2 and IR2Pm4 reduced luciferase mRNA levels only by 11% and 10%, respectively, as compared to that of the wt IR2P (Fig. 1F, bars 4 and 6, respectively), indicating that the DNA binding activity of IR2P is necessary for its negative regulation. Taken together, these results suggested that IR2P inhibits viral gene expression at the transcriptional level and that TFIIB-binding activity of IR2P alone is not sufficient for its inhibitory activity.

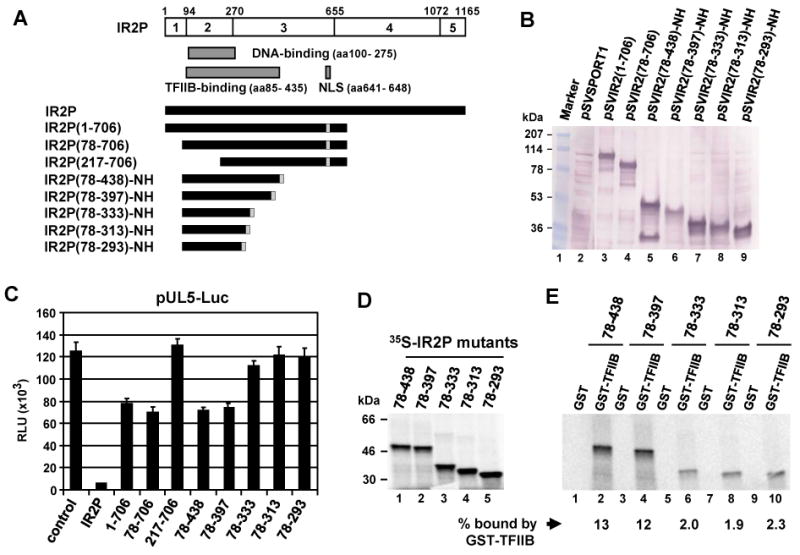

IR2P aa 334 to 397 are important for the inhibitory activity of IR2P

To define the domains of the IR2P that mediate negative regulation, a panel of IR2P deletion mutants was generated and confirmed by western blot analysis (Fig. 2A and B), and used for luciferase reporter assays (Fig. 2C). The expression of full-length IR2P and IR2P(217-706) [IEP(539-1029)] was confirmed in our previous publications (Jang et al., 2001; Kim et al., 2006). The IR2P deletion mutants were detected in the nuclear extracts, indicative of nuclear localization of the proteins (Fig. 2B). In luciferase reporter assays, IR2P(1-706) and IR2P(78-706) down-regulated the early UL5 promoter by 39% and 44%, respectively, of the inhibitory activity of the full-length IR2P (Fig. 2C, bars 3 and 4, respectively). When the N-terminal residues 78 to 216 of the DNA-binding domain (DBD) of IR2P were deleted, the inhibitory activity was reduced to the level of the control empty reporter (Fig. 2C, bar 5). The inhibitory activity of the two C-terminal deletion mutants IR2P(78-438)-NH and IR2P(78-397)-NH that contain the DBD, TFIIB-binding domain, NLS, and a hemagglutinin (HA) epitope tag was slightly reduced as compared to that of IR2P(78-706) (Fig. 2C, bars 6 and 7, respectively). IR2P(78-397) exhibited an inhibitory activity of 40% of that full-length IR2P (Fig. 2C, bar 7) whereas the inhibitory activity of IR2P (78-333) was reduced to only 14% of that of wild-type IR2P (Fig. 2C, bar 8), indicating that IR2P residues 334 to 397 are important for the inhibitory activity of IR2P. Two C-terminal deletion mutants IR2P(78-313)-NH and IR2P(78-293)-NH that contain the DBD and but only a portion of the TFIIB-binding domain completely lost their inhibitory activity (Fig. 2C, bars 9 and 10, respectively). Similar results were obtained with luciferase reporters controlled by the IE, early EICP0, or IR4 promoters (data not shown). These findings suggested that the DNA-binding activity of IR2P alone is not sufficient for its inhibitory activity.

Fig. 2.

IR2P aa 334 to 397 are required for TFIIB interaction. (A) Schematic diagram of the deletion mutants of IR2P. The numbers refer to the number of amino acids from the N-terminus of IR2P. NLS, nuclear localization signal; NH, the IEP (IR2P) NLS and HA epitope tag. (B) Western blot analysis of IR2P deletion mutants. L-M cells were transfected with 1.5 pmol of the full-length and deletion mutant plasmids of IR2P. Nuclear extracts obtained from transfected L-M cells were electrophoresed on SDS-10% PAGE gels. Western blot analysis was performed by using anti-IE monoclonal antibody (mAb) E1.1 (Caughman et al., 1995). (C) Inhibition by the IR2P deletion mutants of the early UL5 promoter. Transient transfection assays were performed as described in Fig. 1E. Luciferase reporter assay was performed at 40 h after transfection as described in Materials and methods. The firefly luciferase signals were normalized to the internal secreted alkaline phosphatase (SEAP) transfection control (see Fig. 1E). Each experiment was carried out in triplicate. Data are averages and represent three or more independent experiments. 1-706, IR2P(1-706). (D) IR2P deletion mutants were expressed by in vitro transcription/translation (IVTT) reactions as described in the Materials and Methods and analyzed by SDS-PAGE. The bands (one fourth input) were quantitated by Phosphor Imager analysis. The numbers on the left represent 14C-methylated protein markers in kilodaltons. (E) GST-pulldown assays. Equal amounts of radiolabeled IR2P deletion mutants were incubated with GST or GST-TFIIB fusion protein and then precipitated with glutathione-Sepharose 4B beads. The precipitated pellets were resolved on SDS-10% PAGE gels. The bands were quantitated by PhosphorImager analysis. The amount of each protein binding to GST-TFIIB was normalized with input of each corresponding protein (Fig. 2D) which was given as the percentage of binding.

Deletion of IR2P residues 334 to 397 impairs TFIIB-binding activity of IR2P

Our previous results showed that the IR2P residues 85 to 435 (IEP aa407-757) harbor a TFIIB-binding domain (Jang et al., 2001). To investigate whether the TFIIB-binding domain of IR2P is required for negative regulation, five IR2P deletion mutants [IR2P(78-293)-NH, IR2P(78-313)-NH, IR2P(78-333)-NH, IR2P(78-397)-NH, and IR2P(78-438)-NH] were expressed by IVTT reactions and used in GST-pulldown assays (Fig. 2D and E). The GST and GST-TFIIB fusion protein were stably expressed and purified as described previously (Jang et al., 2001). In GST-pulldown assays, GST-TFIIB precipitated 13% of input 35S-IR2P(78-438)-NH and 12% of input 35S-IR2P(78-397)-NH (Fig 2E, lanes 2 and 4, respectively), and GST was not able to bind to either of these IR2 proteins (Fig 2E, lanes 1 and 3, respectively). GST-TFIIBΔ125-174 which lacks the domain for binding to IR2P was not able to precipitate 35S-IR2P(78-438)-NH (data not shown). 35S-IR2P(78-333)-NH, 35S-IR2P(78-313)-NH, and 35S-IR2P(78-293)-NH bound weakly to GST-TFIIB as compared to that of 35S-IR2P(78-438)-NH (Fig 2E, lanes 6, 8, 10, respectively), indicating that IR2P aa 334 to 397, which are required for negative regulatory function, are important for IR2P to interact with TFIIB. Thus, these findings and those presented above (Fig. 1 and 2) reveal that both DNA binding and TFIIB binding activities are important for IR2P function.

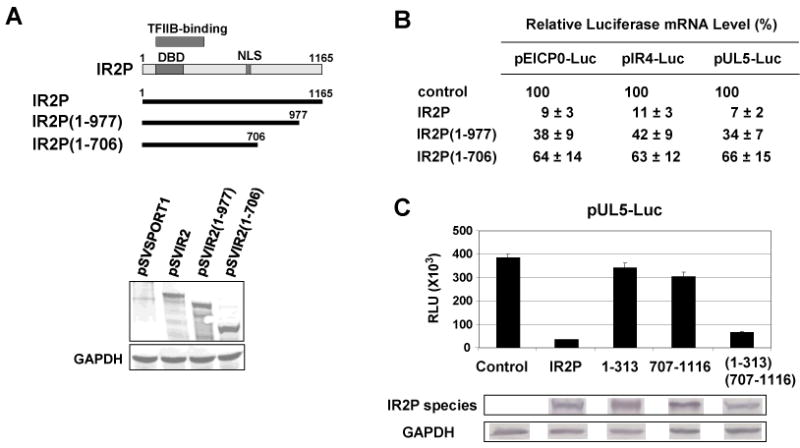

The C-terminal residues 707 to 1165 of IR2P are important for down-regulation of EHV-1 promoters

The results shown in Fig. 2C indicated that the C-terminal residues 707 to 1165 of the IR2 protein are important for inhibition of EHV-1 gene expression. To confirm these results, C-terminal deletion mutants of the IR2P were expressed (Fig. 3A) and examined for the ability to down-regulate representative EHV-1 promoters fused to the luciferase reporter (Fig. 3B). Firefly luciferase mRNA level was measured by RT-PCR in L-M cells cotransfected with luciferase reporter and effector plasmids. Expression of IR2P led to a dramatic decrease (89-93%) in the amount of luciferase mRNA (Fig. 3B). When the C-terminal portion of IR2P was deleted, luciferase mRNA levels were reduced to approximately 38% as compared to that of full-length IR2P in the case of all three promoters (Fig. 3B). However, the protein levels of GAPDH and actin were not changed in the presence of IR2P (data not shown). Taken together, these results confirmed that IR2P inhibits viral gene expression at the transcriptional level and that the C-terminus (aa 707-1116) of IR2P is required for its full inhibitory effect on EHV-1 promoters.

Fig. 3.

The C-terminal residues 707-1165 of IR2P are required for negative regulation of EHV-1 early promoters. (A) Diagram of the deletion mutants of IR2P. The top diagram represents IR2P. DBD, DNA-binding domain; NLS, nuclear localization signal. The numbers refer to the number of amino acids from the N-terminus of IR2P. Bottom panel: western blot analysis of the deletion mutants of IR2P with an anti-IEP pAb OC33. L-M cells were transfected with 1.5 pmol of the full-length IR2 or IR2 deletion mutant plasmids. As a loading control, GAPDH was detected in cell lysates by using anti-GAPDH mAb (Chemicon International, Temecula, CA). (B) Measurement of relative firefly mRNA level. L-M cells were transfected with 0.12 pmol of the reporter plasmids (pEICP0-Luc, pIR4-Luc, and pUL5-Luc) and 0.1 pmol of effector plasmids [control vector pSVSPORT1, pSVIR2, pSVIR2(1-977), and pSVIR2(1-706)]. Reporter plasmids pICP22-SEAP was used to assess transfection efficiency. The firefly luciferase signals were normalized to the internal SEAP transfection controls. The firefly luciferase mRNA levels were measured by RT-PCR and normalized to the level for the control vector pSVSPORT1. Data are averages and are representative of three or more independent experiments. (C) Luciferase reporter assays. Transient transfection assays were performed as described in Fig. 3C. RLU, relative luminescence units. Data are averages and are representative of several independent experiments. Error bars show standard deviations. Western blot analyses of the full-length and mutant forms of IR2P (bottom panel): IR2P [pSVIR2], 1-313 [pSVIR2(1-313)NH], and (1-313)(707-1165) [pSVIR2(1-313)(707-1165)NH] were detected with an anti-IE mAb E1.1 (12); 707-1116 [pSVIR2(707-1116)NH] was detected with the anti-HA mAb (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Each band was from a separate gel.

The IR2P(1-313)NH that contains the DNA-binding domain (DBD; aa 100-275), the NLS, and a HA epitope tag but lacks a functional TFIIB binding domain down-regulated the early UL5 promoter by only 11% of the inhibitory activity of the full-length IR2P (Fig. 3C, bar 3). The IR2P(707-1116)NH which contains residues 707 to 1116 of IR2P down-regulated the UL5 promoter by only 22% of the IR2P's activity (Fig. 3C, bar 4). However, the inhibitory activity of the IR2P(1-313)(707-1116)NH in which the DBD was fused to the IR2P aa 707 to 1116 was restored to 91% of the full-length IR2P's activity (Fig. 3C, bar 5), confirming that the C-terminus (aa 707-1116) of IR2P is required for its inhibitory effect on EHV-1 promoters. In GST-pulldown assays, GST-TFIIB bound weakly to both 35S-IR2P(1-313)-NH and 35S-IR2P(1-313)(707-1116)-NH (see Supplementary Fig. 1) as compared to that of 35S-IR2P(78-438)-NH (Fig. 2E), indicating that the recovery of the inhibitory activity of the IR2P(1-313)(707-1116)-NH was not due to increased TFIIB-binding activity. These results suggested that TFIIB binding is not critical for the activity of the IR2P (1-313)(707-1116) that retains the C-terminal region.

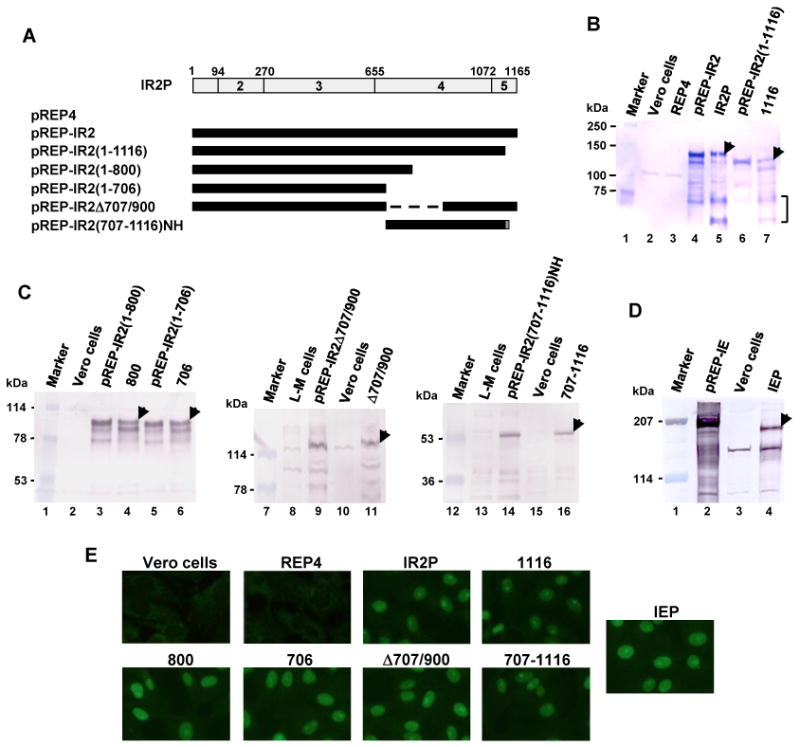

Generation of IR2P- and IEP-expressing Vero cell lines

Findings presented in Fig. 1 to 3 showed that the IR2P down-regulates the IE and early viral promoters. To investigate whether IR2P affects EHV-1 replication and to map the inhibitory regions of IR2P, six Vero cell lines that express full-length IR2P or portions of IR2P were generated by use of the Invitrogen pREP4 vector system (see Materials and Methods). The plasmid pREP4 is an episomal mammalian expression vector that uses the Rous sarcoma virus long terminal repeat (RSV LTR) enhancer/promoter for transcription of recombinant genes. Use of Vero cell lines expressing IR2P or portions of the IR2 protein overcomes the limitations of the transient transfection approach and assures that all cells express the IR2 protein. Plasmids that harbor sequences encoding the full-length IR2P(1-1165), IR2P(1-1116), IR2P(1-800), IR2P(1-706), IR2PΔ707/900, IR2P(707-1116)NH, and full-length immediate-early protein(IEP1-1487) were generated (Fig. 4A). IR2P(707-1116)NH contains the NLS and the hemagglutinin (HA) epitope tag at its C-terminus. The validity of the IR2 constructs was confirmed by DNA sequencing (data not shown), and expression of each IR2 construct in transfected mouse L-M cells generated an IR2P of the expected size (Fig. 4B to 4D). The six IR2P Vero cell lines IR2P, 1116, 800, 706, Δ707/900, and 707-1116, and control vector cell line REP4 were selected, and the synthesis of the IR2P species was confirmed by western blot analyses (Fig. 4B and C) and immunofluorescence (IF) assays (Fig. 4E). Full-length IR2P(1-1165) and IR2P(1-1116) were detected (Fig. 4B, lanes 5 and 7, respectively), and faster-migrating bands (indicated by a bracket at the right) were observed that may be proteolytic cleavage products. IR2P(1-800), IR2P(1-706), IR2PΔ707/900, and IR2P(707-1116)NH were readily detected in the respective cell lines (Fig. 4C lane 4, lane 6, lane 11, and lane 16, respectively). In the case of all six Vero cell lines, expression of each IR2 protein species was stable for prolonged passage of 20 or more subcultures (data not shown). The intracellular distribution of each IR2 protein species was assessed by indirect IF microscopy, and as expected, the full-length and the five deletion forms of IR2P were localized to the nucleus (Fig. 4E) as all harbor the NLS located at aa 641-648 within the full length IR2P (Smith et al., 1995). In IF assays of all six cell lines, more than 99% of the cells expressed the full-length or truncated IR2P. In the Vero cell line that expresses the IE protein, the full length 1,487-aa IEP was detected by western blot analysis (Fig. 4D, lane 4) and was shown to localize to the nucleus (Fig. 4E).

Fig. 4.

Generation of IR2P- and IEP-expressing Vero cell lines. (A) Schematic diagram of the deletion mutants of IR2P. The top diagram represents the 1,165-aa IR2P; the numbers 2 to 5 refer to the regions of the IEP as described by Grundy et al., 1989. The numbers 1 to 1165 refer to the number of amino acids from the N-terminus of IR2P. A dotted line represents deleted amino acid residues. NH indicates the presence of the NLS and HA epitope tag. (B, C, and D) Vero cell lines that express full-length IR2P, portions of the IR2P, or the IE protein were generated by using the Invitrogen pREP4 vector system (see Material and Methods). The eight Vero cell lines IR2P [full-length IR2P], 1116 [IR2P(1-1116)], 800 [IR2P(1-800)], 706 [IR2P(1-706)], Δ707/900 [IR2PΔ707/900], 707-1116 [IR2P(707-1116)-NLS-HA], REP4 [pREP4 control], and IEP [IEP] were selected and confirmed by western blot analyses. The IR2 proteins were detected by western blot analyses using the anti-IE peptide pAb OC33 (which also detects IR2P, Harty and O'Callaghan, 1991), the anti-HA mAb (Sigma) for IR2P(707-1116)-NLS-HA, and the anti-IEP trans-activation domain (TAD) pAb OC89 (Materials and Methods and Supplementary Fig. 3). Faster-migrating bands of lanes B5 and B7 are indicated as a bracket at the right. The arrowheads indicate the IR2P species expressed from the cell lines. Numbers to the left represent molecular weight standards (kDa) (Bio-Rad). (E) The immunofluorescence (IF) assay was performed as previously described (Kim et al., 2006). The Vero cell lines were fixed with 100% methanol for 10 min. The cells were reacted first with the anti-IE peptide pAb OC33 or the anti-HA mAb for 1 h and then reacted with a FITC-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG for 1 h and examined under a Nikon Eclipse TE300 fluorescence microscope.

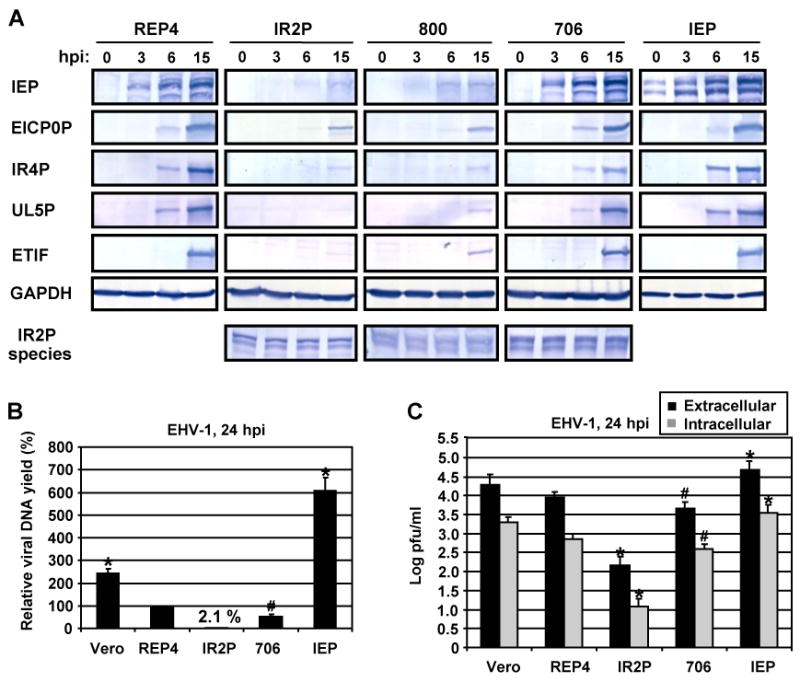

IR2P reduces viral gene expression

To investigate which IR2P species expressed in these cell lines alter viral gene expression, the six IR2P- and the IEP-expressing cell lines were infected with EHV-1 at an MOI of 5, and the expression of viral IE, early, and late regulatory genes was monitored by RT-PCR and western blot analyses. In the infected full-length IR2P cell line, mRNA levels of viral IE, early EICP0, IR4, and UL5, and late ETIF genes were reduced to approximately 3 to 6% of the control infected REP4 cell line (Table 1). In contrast, in the IE protein-expressing cell line, mRNA levels of these viral genes were increased to approximately 340 to 390% of those present in the control infected cell line, indicating that both the IE and IR2 proteins affect viral gene expression at the transcriptional level. In the infected full-length IR2P and IR2P(1-800) cell lines, synthesis of viral IE, early EICP0, IR4, and UL5, and late ETIF proteins was reduced to approximately 3% and 15% of the control infected REP4 cell line, respectively (Fig. 5A). Synthesis of these viral proteins in the IR2P(1-1116) cell line was also reduced to low levels similar to those observed for the full length IR2P cell line (data not shown). In the case of the IR2P(1-706) cell line, the synthesis of all five EHV-1 proteins was reduced (Fig. 5A). The amount of protein loaded for the 706 cell line was twice those of the control REP4 and IEP cell lines. The full-length IR2P and the deletion forms of IR2P, IR2P(1-800) and IR2P(1-706), were expressed at equivalent levels during EHV-1 infection (Fig. 5A, bottom). Expression of the IE protein by the IEP cell line was confirmed as this protein was detectable at 0 hpi (Fig. 5A). Overall, these results indicated that full-length IR2P inhibits viral gene expression and that residues 707 to 1116 of the IR2 protein are important for this inhibitory effect.

Table 1. The full-length IR2P cell line reduced mRNA levels of EHV-1 genes.

| Relative mRNA Level (%)a | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||

| Vero Cell Lines | IE | EICP0 | IR4 | UL5 | ETIF |

| REP4 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| IR2P | 5.7±0.5 | 4.2±0.3 | 3.5±0.3 | 3.8±0.3 | 3.1±0.2 |

| IEP | N/Ab | 395±37 | 368±39 | 342±25 | 382±27 |

The cell lines expressing full-length IR2P and IEP and control cell line REP4 were infected with EHV-1 KyA at an MOI of 5. Cells were harvested at 2 hpi for the IE, 5 hpi for the EICP0, IR4, and UL5, and 8 hpi for the ETIF, and mRNA levels of EHV-1 genes were measured by RT-PCR and normalized to the level for the control REP4 cell line. Data are averages and are representative of several independent experiments.

N/A, nonapplicable. IE mRNA is expressed from both EHV-1 and the IEP cell line.

Fig. 5.

IR2P reduced viral gene expression, viral DNA level, and intracellular virus yield. (A) The Vero cell lines infected with EHV-1 KyA at an MOI of 5 were harvested at 0, 3, 12, 24 hpi, and viral gene expression was analyzed by western blots. The IEP, EICP0P, IR4P, UL5P, ETIF, and IR2P were detected using anti-IEP pAb OC33, anti-EICP0P pAb (Bowles et al., 1997), anti-IR4P pAb (Holden et al., 1994), anti-UL5P pAb (Zhao et al., 1995), anti-ETIF mAb (Kim and O'Callaghan, 2001), respectively. As a loading control, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was detected in cell lysates by using anti-GAPDH mAb (Chemicon International). (B) Control Vero cells and Vero cell lines REP4, IR2P, 706, and IEP were infected with EHV-1 KyA at an MOI of 5. Total DNA was isolated at 24 h postinfection (hpi), and viral DNA yields were determined by qPCR. Each sample was assayed in triplicate. (C) Intracellular and extracellular virus titers were determined by plaque assay on RK-13 cells. Vero cells and Vero cell lines REP4, IR2P, 706, and IEP were infected with EHV-1 KyA at an MOI of 5. Intracellular virus was prepared by three freeze-thaw cycles at 24 hpi as described in the Materials and Methods. Each sample was assayed in triplicate. (B and C) Error bars indicate standard deviation. #, P<0.05 for comparison with the control REP4. *, P<0.01 for comparison with the control REP4.

Expression of IR2P reduces intracellular viral DNA

As shown in Fig. 5A and Table 1, ectopic expression of specific portions of the IR2P was capable of reducing expression of all classes of viral genes. From these results, we speculated that early regulatory IR2P would block viral DNA replication. To address this possibility, intracellular viral DNA levels were measured in EHV-1-infected Vero cell lines at 24 hpi by quantitative PCR (qPCR). The intracellular viral genomic DNA yield was significantly reduced in the full-length IR2P-expressing cell line to 2.1% (50-fold) as compared to that of the infected REP4 cell line (Fig. 5B, bar 3). In the 706 cell line, viral DNA yield was decreased by 2-fold as compared to that of the control cell line (Fig. 5B, bar 4). However, viral DNA yield was increased by 6.1-fold in the IEP cell line as compared to that of the control cell line (Fig. 5B, bar 5). The 200-bp DNA fragment of pREP4 vector backbone was amplified by qPCR in the Vero cell lines REP4, IR2P, 706, and IEP, demonstrating that the four Vero cell lines contain pREP4 plasmid DNA (data not shown). As expected, the virus yield was also reduced by 60-fold in the full-length IR2P-expressing cell line at 24 hpi as compared to that of the infected REP4 cell line (Fig. 5C, bar 6). The 706 cell line showed decreased virus yield of approximately 2-fold (Fig. 5C, bar 8) as compared to that of REP4 vector control. However, the IEP cell line showed increased virus yield of 4.8-fold (Fig. 5C, bar 10) as compared to that of the control cell line. Similar results were obtained for assays of extracellular virus yield (Fig. 5C). Interestingly, full-length IR2P-expressing cells were resistant to EHV-1-mediated cell lysis at an MOI of 5, and more than 96% of the cells were viable at 72 hpi as measured by use of the CellTiter AQ One solution (see Materials and Methods) (see Supplementary Fig. 2). In contrast, more than 95% of the cells in the REP4 control and IEP-expressing cell lines died at 72 hpi, and cytopathic changes appeared by 24 hpi and were characterized by shrinking and rounding of cells, followed by the complete lysis of the monolayer. Taken together, these results demonstrated that synthesis of the full size IR2 protein reduced the viral DNA level and virus replication to the extent that cells were protected from the cytopathic outcome of infection.

The C-terminal portion of IR2P is necessary for the inhibition of EHV-1 replication

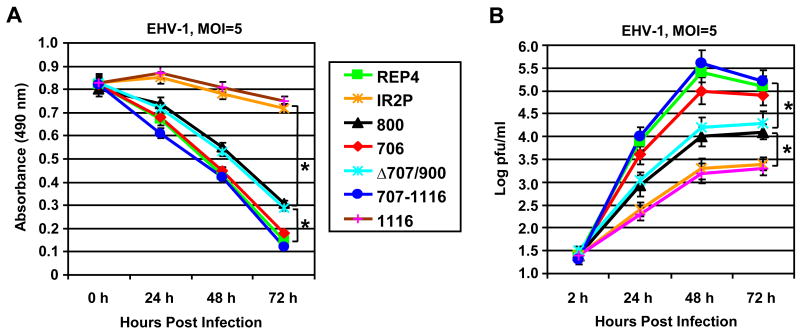

Additional virus growth assays were performed with Vero cell lines that express various portions of IR2P to map the EHV-1 inhibitory regions of IR2P. The seven Vero cell lines were infected with EHV-1 at an MOI of 5, and cell viability (Fig. 6A) and virus titer (Fig. 6B) were monitored at various times of infection. The viability assays showed that EHV-1 infection caused a progressive decrease in cell viability in the 706, 707-1116, and control REP4 cell lines in agreement with the observed CPE (data not shown). EHV-1 infection caused a moderate decrease in the viability of the 800 and Δ707/900 cell lines. In contrast, the full-length IR2P- and IR2P(1-1116)-expressing cell lines were resistant to EHV-1-mediated cell lysis at an MOI of 5, and more than 95% of the cells were viable even at 72 hpi. These results indicated that the C-terminal residues 707 to 1116 of the IR2P are necessary for its protective effect against EHV-1.

Fig. 6.

The C-terminal region of IR2P is necessary for the inhibition of EHV-1 production. The seven Vero cell lines REP4, IR2P, 1116, 800, 706, 707-1116, and Δ707/900 were infected with EHV-1 KyA at an MOI of 5. Cell viability (A) and virus titer (B) were investigated at various times of infection as described in the Materials and Methods. Each sample was assayed in triplicate. Error bars indicate standard deviation. *denote statistical significance (P<0.01).

To identify IR2P sequences necessary for the ability of IR2P to inhibit EHV-1 replication, samples of the seven Vero cell lines infected at an MOI of 5 with EHV-1 KyA were harvested at 2, 24, 48, and 72 hpi and assayed for extracellular and intracellular virus titers by plaque assay. The full-length IR2P cell line reduced virus yield by 100-fold at 48 hpi as compared to that of the empty vector REP4 cell line (Fig. 6B). The IR2P(1-1116) cell line reduced virus yield by 125-fold as compared to that of the empty vector REP4 cell line at 48 hpi (Fig. 6B), indicating that C-terminal region aa 1117-1165 is not necessary for the inhibitory effect. The 800 and Δ707/900 cell lines reduced virus yield by 16-fold and 13-fold, respectively, indicating that IR2P sequences aa 707 to 800 and aa 900 to 1116 contributed to the inhibition of EHV-1 replication. The 706 cell line reduce virus yield by only 3-fold (Fig. 6B). However, the 707-1165 cell line failed to reduce virus yield (Fig. 6B). Taken together, these results suggest that IR2P sequences aa 707 to 1116 are necessary for the inhibition of EHV-1 replication (Fig. 7).

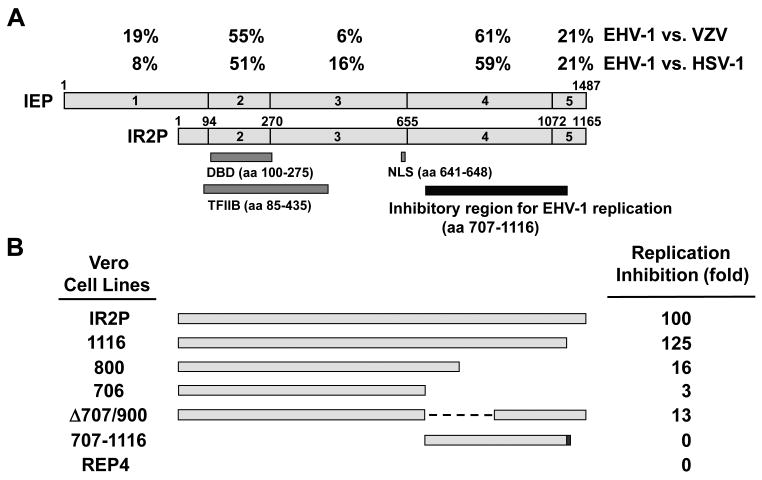

Fig. 7.

The C-terminal region of IR2P is necessary for the inhibition of EHV-1 replication. (A) Diagram represents the IEP and IR2P which have been divided into five regions (regions 1 to 5; Grundy et al., 1989; Kim et al., 1995). The numbers refer to the number of amino acids from the N-termini of IEP and IR2P. Percentages indicate homology of each region of the EHV-1 IE protein and varicella zoster virus (VZV) ORF62 and HSV-1 ICP4 (Grundy et al., 1989). (B) Replication Inhibition refers to the fold reduction in virus titer in cell lines expressing portions of IR2P as compared to the virus titer of the control REP4 cell line. Data are from Figures 5 and 6 and show fold reduction at 48 hpi.

To assess whether the inhibition of EHV-1 replication by IR2P is virus strain-specific, selected Vero cell lines were infected at an MOI of 5 with three different EHV-1 strains, attenuated KyA, pathogenic Ab4, and pathogenic RacL11, and viral DNA yield was measured at 24 and 48 hpi. In the full length IR2P-expressing cell line, the amount of EHV-1 KyA, Ab4, and RacL11 genomic DNA was reduced to 1.3%, 6.1%, and 9.6%, respectively (data not shown) at 48 hpi as compared to the level of these genomes in the infected control REP4 cell line These results indicate that IR2P inhibits EHV-1 replication regardless of virus strain.

Discussion

The data presented in this study revealed that the negative regulatory function of the IR2 protein of equine herpesvirus 1 requires both the DNA-binding and TFIIB-binding activities. The DNA-binding and TFIIB-binding domains are overlapped within IR2P region 2 (aa94-270) which corresponds to IEP region 2 (aa416-592). EHV-1 IEP region 2 shows approximately 51% and 55% amino acid identity with regions within both HSV-1 ICP4 and VZV ORF62, respectively (Fig. 7; Grundy et al., 1989), suggesting that residues within region 2 are important for the functions of these proteins.

Deletion of residues 314 to 435 of the TFIIB-binding domain (aa86-435) of IR2P resulted in considerable loss of the TFIIB-binding activity as well as complete loss of its inhibitory activity. IR2P interacts with EHV-1 early regulatory proteins EICP0P and UL5P and abrogates EICP0P- and UL5P-mediated trans-activation ability in a dose-dependent manner (Kim et al., 2003, 2006). IR2P residues 314 to 435 equate with residues within the immediate early protein that interact with TFIIB and also overlap with domains for the IEP to interact with regulatory UL5P (Albrecht et al., 2005) and EICP0P (Kim et al., 2003). These facts suggest that these residues are important for IR2P function by retarding the binding of the IEP to TFIIB and EHV-1 early regulatory proteins.

ICP4 of HSV-1 represses transcription of its own promoter and binds viral promoter DNA cooperatively with TBP and TFIIB to form a tripartite protein-DNA complex (Smith et al., 1993). ICP4 interacts with TFIIB and TBP to enhance the assembly and/or stability of the preinitiation complex (PIC) to activate transcription (Carrozza and DeLuca, 1996; Grondin and DeLuca, 2000). Thus, a direct interaction of IR2P with TFIIB, TBP, and other general transcription factors (GTFs) may occur. This would block the formation of a functional PIC because IR2P does not harbor the trans-activation domain (TAD). Our preliminary data showed that the IEP TAD interacts with TFIIA (Zhang and O'Callaghan, unpublished data). The TAD may induce a conformational change in the GTFs and this could, in turn, affect the ability of the GTFs to interact with DNA or the other GTFs. The findings in this study revealed that the DNA-binding and TFIIB-binding activities of IR2P are both required for its negative regulatory function. IR2P also interacts with TBP (Kim et al., 2006). Tripartite protein-DNA complex (IR2P-TFIIB-TBP-DNA) or protein-DNA complexes (IR2P-TFIIB-DNA or IR2P-TBP-DNA) may explain how IR2P inhibits transcription of viral promoters. The VZV major trans-activator IE62 activation domain (TAD) targets the human Mediator complex via the Med25 subunit, and this interaction appears to be essential for trans-activation by the IE62 activation domain (Yamamoto at al., 2009; Yang et al., 2008).

The data from these studies indicated that full-length IR2P(1-1165) and IR2P(1-1116)-expressing Vero cell lines are resistant to EHV-1-mediated cell lysis and inhibit EHV-1 gene expression and replication. The inhibitory activity of IR2P lacking residues 707 to 1165 on EHV-1 promoters was reduced to approximately 38% of the activity of the full-length IR2P. Unexpectedly, the IR2P(1-706) cell line which expresses an IR2P harboring the DBD, TFIIB, and NLS domains very weakly inhibit EHV-1 replication. The IR2P(1-800) cell line inhibits EHV-1 replication by only 16% of the activity of the full-length IR2P cell line (see Fig. 7). IR2P harbors more than one domain that mediates an interaction with TBP. One of the TBP-binding domains lies within the C-terminal residues 576 to 1165 of IR2P (Kim et al., 2006), which may explain the reduced inhibitory activity of IR2P lacking the C-terminal portion. These results suggested that the C-terminal residues 707 to 1165 of IR2P contribute to the inhibition of viral gene expression and may be essential for the inhibition of viral replication during the course of a productive infection.

The C-terminal region of ICP4 of HSV-1 has also been shown to be important in the trans-activation function of this major IE protein. HSV-1 expressing ICP4 lacking the C-terminal region has been described as defective for full activation of early genes, viral DNA synthesis, and expression of late genes (Cheung, 1989). ICP4 is able to form TBP- and RNA polymerase II (PolII)-containing complexes on the late gC promoter, and formation of this complex required the ICP4 DNA-binding domain and its C-terminal 524 amino acids (Sampath and DeLuca, 2008). In contrast, an ICP4 protein lacking the C-terminal 524 amino acids was able to form TBP- and RNA polymerase II (Pol II)-containing complexes on the early TK promoter (Sampath and DeLuca, 2008), suggesting that a region of ICP4 may differentiate between formation of TBP- and Pol II-containing complexes on E and L promoters. The presence of ICP4 C-terminal residues 774 to 1289 (regions 4 and 5) was important for activation in vitro and in vivo (Carrozza and DeLuca, 1996). ICP4 interaction with TFIID involves the TAFII250 molecule and the C-terminal region of ICP4, and this interaction is part of the mechanism by which ICP4 activates transcription (Carrozza and DeLuca, 1996).

The findings of this study suggested that IR2P aa 707 to 800 and aa 901 to 1116 which correspond to IEP region 4 (aa 977-1394) are important for the inhibition of EHV-1 replication. EHV-1 IEP region 4 shows approximately 60% amino acid identity with regions within both HSV-1 ICP4 and VZV ORF62 (Fig. 7; Grundy et al., 1989), indicating that residues within region 4 are important for functions of these major trans-activators. Findings from western blot and viral DNA yield assays of the IR2P-expressing cell lines suggest that IR2P C-terminal residues 707 to 1116 are required for full down-regulation of EHV-1 gene expression as well as the inhibition of viral replication. When the DBD (IR2P aa1-313) was fused to the C-terminus (IR2P aa707-1116), the inhibitory activity was restored in a more than an additive fashion relative to the activity of the single DBD and C-terminus, suggesting that the C-terminus may contain binding domains for cellular factors required for transcription. Indeed, our previous results showed that one TBP-binding domains lies within the C-terminal residues 576 to 1165 of IR2P (Kim et al., 2006). Our recent experiments showed that both IEP and IR2P interacted with Pol II (Y. Zhang, S. K. Kim, and D. J. O'Callaghan, unpublished data), suggesting that the C-terminal region of IR2P may interact with TBP and/or Pol II and other transcription factors. Unexpectedly, an IR2P harboring C-terminal residues 707 to 1116 which do not contain the DBD has some inhibitory activity (Fig. 3C, bar 4), supporting the possibility that IR2P may inhibit EHV-1 gene expression by squelching the limited supplies of cellular factors required for viral transcription.

The precise mechanism by which IR2P inhibits EHV-1 gene expression and replication is unknown. In transient transfection assays, IR2P down-regulated EHV-1 promoters (Fig. 1 to 3) and abrogated trans-activation mediated by IEP and early regulatory UL5 protein (Jang et al., 2001). In this study, the levels of EHV-1 genomic DNA, mRNA, and proteins as well as the virus yield were significantly reduced in the IR2P-expressing cell line. These results suggested that IR2P inhibits viral gene expression which leads to virus attenuation by direct interference with virus replication. In luciferase reporter assays, IR2P reduced luciferase mRNA level, demonstrating that IR2P inhibits viral gene expression at the transcriptional level. IR2P physically interacted with the general transcription factors TFIIB and TBP (Albrecht et al., 2003, Jang et al., 2001; Kim et al., 2006). On the basis of these findings, we hypothesize that IR2P functions as a dominant-negative regulator of EHV-1 gene expression by blocking IEP-binding to viral promoter sequences and/or by squelching the limited supplies of TFIIB, TBP, and/or other cell factors required for viral transcription.

IR2P may contribute to the switch from early to late gene expression in the EHV-1 gene program. Our recent work revealed that the IR3 RNA transcript that is antisense to a portion of the IE mRNA negatively regulates IE gene expression (Ahn et al., 2007, 1010). Thus the IR2P and IR3 RNA are two EHV-1-unique modulators that negatively affect the expression of the sole IE gene at the level of transcription. In addition, our most recent studies showed that the EHV-1 early UL4 protein down-regulates viral promoters and seems to function by a mechanism quite different from that of IR2P (Charvat et al., 2011). Thus, EHV-1 employs the early IR2 and UL4 proteins and the IR3 antisense transcript to modulate viral gene expression. It is possible that these EHV-1 gene products contribute to the events of lytic infection but also play more important roles in EHV-1 latency. Ongoing efforts to generate and characterize EHV-1 mutant viruses that fail to express these negative regulators should give more insight into their importance in EHV-1 biology.

Materials and Methods

Viruses and cell culture

The KyA strain of EHV-1 was propagated in suspension cultures of L-M mouse fibroblasts as previously described (O'Callaghan et al., 1968; Perdue et al., 1974). Two pathogenic Ab4 and RacL11 strains were propagated in equine NBL6 cells. Mouse fibroblast L-M, rabbit kidney RK-13, and Vero cells were maintained at 37°C in complete Eagle's Minimum Essential Medium (EMEM) supplemented with 100 U/ml of penicillin, 100 μg/ml of streptomycin, nonessential amino acids, and 5% fetal bovine serum.

Mammalian expression and in vitro transcription/translation plasmids

Plasmids were constructed and maintained in Escherichia coli (E. coli) HB101 or JM109 by standard methods (Sambrook et al., 1989). Plasmids pSVIE, pSVIR2, pSVIR2(217-706) [pSVIE(539-1029)] have been described previously (Kim et al., 2003, 2006; Smith et al., 1992, 1995). Expression vector pSVSPORT1 (GIBCO-BRL, Grand Island, NY) can be used for both mammalian expression and in vitro transcription/translation. To generate plasmid pSVIR2(1-706), pSVIR2 was digested with KpnI and EcoRI, blunted with Klenow fragment, a HindIII linker (5′-ccaagcttgg-3′) was inserted, and the plasmid was designated pSVIR2-H. Plasmid pSVIR2-H was digested with XbaI, blunted with Klenow fragment, a KpnI linker (5′-gggtaccc-3′) was inserted, and the plasmid was designated pSVIR2-KH. The 3.9-kb KpnI-HindIII fragment of pSVIR2-KH was cloned into the KpnI and HindIII sites of pSVSPORT1 (GIBCO-BRL) to generate pSVIR2-H2. Fifty-five bp oligonucleotide (5-tga cta ggt agc gca aat ttc aca ata aag caa tag cat ctc tag acc caa gct t-3′) was cloned into the PvuII and HindIII sites of pSVIR2-H2 to generate pSVIR2(1-706). To generate plasmid pSVIR2(1-977), the 2.1-kb AscI-XbaI fragment of pSVIE(1-1299) was cloned into the AscI and XbaI sites of pSVIR2-RX (see pREP4 plasmids below). pSVSPORT1 was digested with HindIII and EcoRI, a synthetic linker B (coding strand: 5′-aat tGc cat ggc cca gct gac tct cga ggaattc cta-3′, noncoding strand: 5′-agc tta ggaattc ctcg aga gtc agc tgg gcc atg gc-3′) which contains an EcoRI sequence (underlined) was inserted, and the plasmid was designated pSVSPORT-L of which the cloning EcoRI site cannot be recleaved because the synthetic linker B lacks the EcoRI consensus sequence at the end of the linker B (see the capital letter; aattG). The 1.2-kb PvuII-XhoI fragment of pSVIR2-RX was cloned into the PvuII and XhoI sites of pSVSPORT-L to generate plasmid pSVIR2(707-1116). To generate plasmid pSVIR2(707-1116)NH, a synthetic linker NLS-HA (coding strand: 5′-aa ttc ccg ccc gcc cct aag cgg cgc gtg tac gac gta cca gat tac gct tac aaa ttt cac aaa taa agc aat cta gac ca-3′, noncoding strand: 5′-agc ttg gtc tag att gct tta ttt gtg aaa ttt cta agc gta atc tgg tac gtc gta cac gcg cct ctt agg ggc ggg cgg g-3′) which contains nucleotide sequences for the IEP (IR2P) nuclear localization signal (NLS) and hemagglutinin (HA) epitope tag was cloned into the EcoRI and HindIII sites of pSVIR2(707-1116). To generate plasmid pSVIR2(1-313)NH, the 950-bp IR2 DNA fragment from pSVIR2 was amplified by PCR with primers (forward primer: 5′-ccc ggt acc cac gcc atg gct tct ccg ccg ggc cgg agc cct cac-3′, reverse primer: 5′-ggg gaa ttcg ggc ccg agg gcc gcg cag acc cgg gtg ta-3′) which contain KpnI and EcoRI sites, respectively, and the fragment was cloned into the KpnI and EcoRI sites of the pSVIR2(707-1165)NH which contains nucleotide sequences for the IEP NLS and HA epitope tag. To generate plasmid pSVIR2(1-313)(707-1165)NH, the 1230-bp IR2 DNA fragment from pSVIR2 was amplified by PCR with primers (forward primer: 5′-ggg gaa ttc ctg ttc ccc gag gcc tgg cgc ccg gcg ctc acc ttc-3′, reverse primer: 5′-ccc aag ctt tca cac gcg cct ctt agg ggc ggg cgg ctc gtc gtc ggg ctc cgg cag gca-3′) which contain EcoRI and HindIII sites, respectively, and the fragment was cloned into the EcoRI and HindIII sites of the pSVIR2(1-313)NH. To generate plasmid pSVIR2m1 (pSVIR2W171S), pSVIEW493S(1-1487) was digested with StuI and a KpnI linker (5′-CCGGTACCGG-3′) was inserted. To generate plasmid pSVIR2m2 (pSVIR2Q173E), pSVIEQ495E(1-1487) was digested with StuI and a KpnI linker (5′-CCGGTACCGG-3′) was inserted. To generate plasmid pSVIR2m3 (pSVIR2N174I), pSVIEN496I(1-1487) was digested with StuI and a KpnI linker (5′-cggtaccg-3′) was inserted. To generate plasmid pSVIR2m4 (pSVIR2K176E), pSVIEK498E(1-1487) was digested with StuI and a KpnI linker (5′-cggtaccg-3′) was inserted. To generate plasmid pSVIR2(78-293)-NH, the 650-bp IR2 DNA fragment from pSVIR2 was amplified by PCR with primers (forward primer: 5′-ccg gta cca gga tgg ctt cgt gcg ccc cgg gcg tct acc agc gcg agc cg-3′, reverse primer: 5′-ccg aat tcg gcc tcg ggc tgt tgc tgg ctg gcc gcg gc-3′) which contain KpnI and EcoRI sites, respectively, and the fragment was cloned into the KpnI and EcoRI sites of the pSVSPORT1 and the plasmid was designated pSVIR2(78-293). A synthetic linker NLS-HA which contains nucleotide sequences for the IEP (IR2P) nuclear localization signal (NLS) and hemagglutinin (HA) epitope tag was cloned into the EcoRI and HindIII sites of pSVIR2(78-293) to generate plasmid pSVIR2(78-293)-NH. To generate plasmid pSVIR2(78-313)-NH, the 700-bp IR2 DNA fragment from pSVIR2 was amplified by PCR with primers (forward primer: 5′- ccg gta cca gga tgg cttc gtg cgc ccc ggg cgt cta cca gcg cga gcc g-3′, reverse primer: 5′- ccg aat tcg ggc ccg agg gcc gcg cag acc cgg gtg ta-3′) which contain KpnI and EcoRI sites, respectively, and the fragment was cloned into the KpnI and EcoRI sites of the pSVIR2(78-293)-NH. To generate plasmid pSVIR2(78-333)-NH, the 760-bp IR2 DNA fragment from pSVIR2 was amplified by PCR with primers (forward primer: 5′-ccg gta cca gga tgg ctt cgt gcg ccc cgg gcg tct acc agc gcg agc cg-3′, reverse primer: 5′-ccg aat cgg cgg acg gcc tgg gcg ccc tgg tcc ccg g-3′) which contain KpnI and EcoRI sites, respectively, and the fragment was cloned into the KpnI and EcoRI sites of the pSVIR2(78-293)-NH. To generate plasmid pSVIR2(78-397)-NH, the 960-bp IR2 DNA fragment from pSVIR2 was amplified by PCR with primers (forward primer: 5′- ccg gta cca gga tgg ctt cgt gcg ccc cgg gcg tct acc agc gcg agc cg-3′, reverse primer: 5′- ccg aat tcc agc ccg gcc ggg ttg gcg cac agc gcc tc-3′) which contain KpnI and EcoRI sites, respectively, and the fragment was cloned into the KpnI and EcoRI sites of the pSVIR2(78-293)-NH. To generate plasmid pSVIR2(78-438)-NH, the 1080-bp IR2 DNA fragment from pSVIR2 was amplified by PCR with primers (forward primer: 5′-ccg gta cca gga tgg ctt cgt gcg ccc cgg gcg tct acc agc gcg agc cg-3′, reverse primer: 5′-ccg aat tca acg gcg cgc acc gcg agg cgc agc tcg tc-3′) which contain KpnI and EcoRI sites, respectively, and the fragment was cloned into the KpnI and EcoRI sites of the pSVIR2(78-293)-NH.

pREP4 plasmids

IR2P-expressing Vero cell lines were generated by using the pREP4 vector system (Invitrogen, San Diego, CA). To generate plasmid pREP-IR2(1-1116), the 3.9-kb HindIII-EcoRI fragment of pSVIR2 was cloned into the HindIII and EcoRI sites of pcDNAI/Amp (Invitrogen), and the plasmid was designated pC-IR2. The 3.5-kb KpnI-XhoI fragment of pC-IR2 was cloned into the KpnI and XhoI sites of pREP4 to generate pREP-IR2(1-1116). To generate plasmid pREP-IR2(1-1165), the 0.5-kb XhoI fragment of pC-IR2 was cloned into the XhoI site of pREP-IR2(1-1116). To generate plasmid pREP-IR2(1-1165)-N, 24 bp synthetic oligonucleotide (5′-aagctcctctagagcccaagcttcgaattc-3′) was cloned into the HindIII and EcoRI sites of pSVIR2-KH, and the plasmid was designated pSVIR2-RX. The 3.9-kb KpnI-HindIII fragment of pSVIR2-RX was cloned into the KpnI and HindIII sites of pREP4 to generated pREP-IR2(1-1165)-N. To generate plasmid pREP-IR2(1-800), the 300-bp IR2 DNA fragment from pSVIR2 was amplified by PCR with primers (forward primer: 5′-ctc atc gac aac cag ctg ttc ccc gag gcc-3′, reverse primer: 5′-cca agc ttg ggt cta gat gct att gct tta ttt gtg aaa ttt gcg cta cct agg acc aga ggg gct cgc gcc gag agc cgc c-3′) which contain PvuII and HindIII sites, respectively, and the fragment was cloned into the PvuII and HindIII sites of the pREP-IR2(1-1165)-N. To generate plasmids pREP-IR2(1-706), the 2.2-kb KpnI-XhoI fragment of pSVIR2(1-706) was cloned into the KpnI and XhoI sites of pREP4 (Invitrogen). To generate plasmid pREP-IR2Δ707/900, the 840-bp IR2 DNA fragment from pSVIR2 was amplified by PCR with primers (forward primer: 5′-ccc agc tga ctc cgc ggg tcg cct gcg ccg tgc gc-3′, reverse primer: 5′-tgc cgg cct cga gcg gcc gct agc aag ctt-3′) which contain PvuII and HindIII sites, respectively, and the fragment was cloned into the PvuII and HindIII sites of the pREP-IR2(1-1165)-N. To generate plasmid pREP-IR2(707-1116)NH, the 1.2-kb KpnI-HindIII fragment of pSVIR2(707-1116)NH was cloned into the KpnI and HindIII sites of pREP4.

GST-fusion, luciferase reporter, and the secreted alkaline phosphatase (SEAP) plasmids

Plasmids pGST-IR2, pGSTKG-TFIIB, pGST-hTBP, pIE-Luc, pEICP0-Luc, pIR4 (EICP22)-Luc, pUL5 (EICP27)-Luc have been described previously (Jang et al., 2001; Kim et al., 2006). Plasmid pICP22-SEAP (kindly provided by S. V. Hsia, University of Maryland Eastern Shore) has been described previously (Bedadala et al., 2007). To generate plasmid pGST-IR2W493S, the 4.0-kb StuI-EcoRI fragment of pSVIEW493S(1-1487) was cloned into the SmaI and EcoRI sites of pGEX-KG (Guan and Dixon et al., 1991). To generate plasmid pGST-IR2Q495E, the 4.0-kb StuI-EcoRI fragment of pSVIEQ495E(1-1487) was cloned into the SmaI and EcoRI sites of pGEX-KG. To generate plasmid pGST-IR2N496I, the 4.0-kb StuI-EcoRI fragment of pSVIEN496I(1-1487) was cloned into the SmaI and EcoRI sites of pGEX-KG. To generate plasmid pGST-IR2K498E, the 4.0-kb StuI-EcoRI fragment of pSVIEK498E(1-1487) was cloned into the SmaI and EcoRI sites of pGEX-KG.

Expression and purification of GST fusion proteins

The expression and purification of GST-fusion proteins has been described elsewhere (Kim et al., 1995). The bacterial strains Escherichia coli BL21(DE3)pLysE (Novagen, Madison, WI) was employed for induction of GST-fusion protein synthesis. The methods for desalting and for ascertaining the concentration of the purified GST-fusion proteins were described elsewhere (Albrecht et al., 2003; Jang et al., 2001).

In vitro transcription/translation reactions

In vitro transcription/translation (IVTT) reactions were performed with the TNT SP6 High Yield Wheat Germ Master Mix (Promega, Madison, WI) according to the manufacturer's directions. 35S-labeled proteins were synthesized by including [35S]methionine (40 μCi/ml; specific activity, 1,175 Ci/mmol; New England Nuclear Corporation, Boston, MA) in the IVTT reactions. Synthesis of the 35S-labeled proteins was verified by SDS-PAGE analysis and autoradiography.

GST-pulldown assays

GST-pulldown assays that employed 35S-labeled polypeptides were performed as detailed previously (Kim et al., 2003). Briefly, 2 μg of either GST alone or the indicated GST fusion protein were mixed with 35S-labeled proteins in 700 μ1 of NETN buffer. The 35S-labeled proteins precipitated by the GST fusion protein were analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by autoradiography and visualization using the Storm phosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics) or the Molecular Imager FX system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA).

Gel shift assays

The IE promoter region (position -16 to +22) was end-labeled with [γ-32P]ATP as previously detailed (Kim et al., 1995). DNA binding assays were conducted as previously described (Kim et al., 1995). The standard DNA binding reaction mixture contained 0.5 to 1 ng of radiolabeled DNA fragments (2×104 cpm/ng), 0.1 μg of poly(dI-dC) as a nonspecific competitor, and 1 to 10 μ1 of purified proteins in 20 μ1 of DNA binding buffer (20 mM Hepes-KOH [pH 7.9], 0.5 mM dithiothreitol, 10% glycerol, 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.025% NP-40, 25 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2). After 20 min at 22°C, 5 μ1 of loading buffer (200 mM Hepes-KOH [pH 7.5], 50% (vol/vol) glycerol, 0.02% bromophenol blue) was added, and the sample was subjected to electrophoresis at 22°C for 2 h at 200 V on a 3% polyacrylamide gel with 0.5 X Tris-Borate-EDTA running buffer.

Luciferase reporter assays

The luciferase reporter assay was performed as previously described (Kim et al., 2006). Briefly, L-M cells were seeded at 50% confluency in 24 well plates, and transfected with 0.12 pmol of reporter vector and 0.08 pmol of effectors. Six μ1 of lipofectin (Invitrogen) were mixed with 300 μ1 of Opti-MEM medium and incubated for 45 min at room temperature. The effector and reporter vectors were mixed with 300 μ1 of Opti-MEM medium, and the total amount of DNA was adjusted to the same amount with pSVSPORT1 DNA. The solutions were combined and incubated at room temperature for 15 min, and one-third volume was transferred into each of three wells of L-M cells. After a further 5 h, the cells were re-fed with fresh medium. At 40 h posttransfection, luciferase activity was measured by using a luciferase assay kit (Promega, Madison, WI) and a Polarstar Optima plate reader (BMG LABTECH Inc., Cary, NC).

The secreted alkaline phosphatase (SEAP) assays

SEAP activity in culture medium was determined by a chemiluminescence method using a Great Escape SEAP kits (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA). In brief, 10-μL samples were mixed with 30 μ1 of dilution buffer and incubated at 65°C for 30 minutes. Forty microliters of assay buffer containing L-homoarginine was then added. After 5 min at room temperature, the samples were exposed to 40 μ1 of chemiluminescent substrate CSPD (disodium 3-[4-methoxyspiro{1.2-dioxetane-3,2′-(5′-chloro)tricyclo(3.3.1.1)-decan}4-yl]phenyl phosphate) (1.25 mM) or 3 μ1 of fluorescent substrate 4-methylumbelliferyl phosphate (Clontech). Chemiluminescence was measured with a Polarstar Optima plate reader after a 20 min incubation at room temperature.

Generation of anti-IEP trans-activation domain (TAD) polyclonal antibody

Antibody generation has been described elsewhere (Albrecht et al., 2004; Charvat et al., 2011). Briefly, four New Zealand White rabbits (approximately 3 kg per rabbit) were each immunized intramuscularly in a hind leg with 500 μg of either purified GST-IEP TAD (aa1-88) fusion protein (OC88 and OC89). The primary inoculum was emulsified in Freund's complete adjuvant, and after 4-8 weeks, booster immunizations emulsified in incomplete Freund's adjuvant were administered every 14 days for a total of four booster injections for each rabbit. Before each booster injection, small quantities of serum were drawn from each rabbit to test antibody titers before the final bleed was performed. The anti-IEP TAD antibodies were purified using protein A agarose beads (Pierce, Rockford, IL) according to the manufacturer's directions. The working dilution in western blot assays was 1:6,000 or greater (see Supplementary Fig. 3).

Western blot analysis

Preparation of cytoplasmic and nuclear extracts of transfected cells and western blot analysis were performed as previously described (Kim et al., 2006). Blots were incubated with an anti-IE pAb OC33 for 1 h. The blots were washed three times for 10 min each in TBST and incubated with secondary antibody (anti-rabbit IgG [Fc]-alkaline phosphatase [AP] conjugate [Promega]) for 1 h. Proteins were visualized by incubating the membranes containing blotted protein in AP conjugate substrate (AP conjugate substrate kit, Bio-Rad) according to manufacturer's directions.

Generation of IR2P-expressing Vero cell lines

Plasmid pREP4 is an episomal mammalian expression vector that uses the Rous sarcoma virus long terminal repeat (RSV LTR) enhancer/promoter for transcription of recombinant genes inserted into the multiple cloning site. The Epstein-Barr Virus replication origin (oriP) and nuclear antigen (encoded by the EBNA-1 gene) are carried by this plasmid to permit extrachromosomal replication in human, primate, and canine cells. pREP4 also carries the hygromycin B resistance gene for stable selection in transfected cells. IR2P- and IEP-expressing Vero cell lines were generated by using the pREP4 vector system (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Vero cells were transfected with seven recombinant pREP4 plasmids [pREP-IR2(1-1165), pREP-IR2(1-1116), pREP-IR2(1-800), pREP-IR2(1-706), pREP-IR2Δ707/900, pREP-IR2(707-1116)NH, and PREP-IE] and pREP4 control plasmid (Fig. 3A). Twenty-four hours after transfection, the cells were washed and refed with fresh medium. At 48 h after transfection, the cells were split into fresh medium containing hygromycin B (Invitrogen) at 250 μg/ml and plated at a 25% confluence. The cells were fed with selective medium every 3 days until hygromycin-resistant foci could be identified. Colonies were picked and expanded in 48-well plates. These cell lines were selected by IF and western blot analyses and were maintained in medium containing 50 μg/ml hygromycin.

Vero cell line viability assays

IR2P- and IEP-expressing Vero cell lines were infected with EHV-1 KyA at the indicated multiplicity of infection (MOI) and assayed for cytopathic effect (CPE) and virus titer at 72 h postinfection (hpi). Changes in cell morphology were evaluated by a Nikon Eclipse TE300 fluorescence microscope. Cell viability was measured by CellTiter AQ One solution (Promega). 2×104 Vero cells expressing full-length IR2P or portions of IR2P were added to the wells of a 96-well plate. After 24 h incubation at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere, assays were performed by adding 20 μ1 of CellTiter 96 AQ one solution reagent directly to culture 96 wells, and after incubation for 1 h the absorbance at 490nm was determined with a 96-well plate reader. The cell culture media were harvested at 2, 24, 48, and 72 hpi, and virus titers were determined by plaque assay on RK-13 cells. After viability assays of the Vero cell lines were carried out, the Vero cells were fixed with 10% formalin solution (Fisher Scientific, Kalamazoo, MI) and stained with crystal violet.

Plaque assays

Intracellular and extracellular EHV-1 virus titers were determined on RK-13 cells. To prepare intracellular virus, infected cell monolayers were rinsed 3X with fresh medium, scraped into 3 ml (the same volume of the original medium), and subjected to three freeze-thaw cycles. Serial dilutions of samples from each passage were used to inoculate fresh RK-13 (EHV-1) monolayers. Infected monolayers were incubated in medium containing 1.5% methylcellulose. Plaques were quantitated after 2-4 days by fixing with 10% formalin solution (Fisher Scientific) and staining with 0.5% crystal violet.

Quantitative PCR

Vero cells and IR2P- or IEP-expressing Vero cell lines were infected with EHV-1 at an MOI of 5. Cells were harvested at 24 hpi, and total DNA was extracted from infected cell using DNeasy blood & tissue Mini kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA). Quantitative PCR (qPCR) was performed using the IQ™ 5 multicolor real-time PCR detection system with iQ SYBR green supermix according to the instructions of the manufacturer (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). The comparative CT method for relative quantitation (2-ΔΔCT) was used with human glyceraldehydes-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) as the endogenous housekeeping gene. The primers used in qPCR were as follows: GAPDH-F (5′-gggtttatggaggtcctcttgtgt-3′) and GAPDH-R (5′- acccagtcctcccggtgacattta-3′) for GAPDH, UIE-F (5′-ctccgaggcccgcttcgacctagc-3′) and UIE-R (5′-agcagaggcggaaaagatgttgag-3′) for EHV-1 genomic DNA, REP-F (5′-ggcgaaaagcggggcttcggttgt-3′) and REP-R (5′-cgtaccaccttacttccaccaatc-3′) for pREP4. Each sample was assayed in triplicate.

RT- PCR

Total RNA was prepared using RNeasy Mini kit (QIAGEN, CA). One step SYBR green real-time RT-PCR amplification was carried out with IQ™ multicolor real-time PCR detection system with iScript one step RT-PCR kit using SYBR Green according to the instructions of the manufacturer (Bio-Rad, CA). RT conditions were as follows: 10 min at 50°C and 5 min at 95°C, followed by 40 cycles of PCR for 20 sec at 95°C for denaturation, 60 sec at 60°C for annealing and extension. For the melting curve analysis: After 40 reaction cycles, the temperature ramp was programmed from 55 to 95 °C in increments of 0.5 °C, waiting 10 sec before each acquisition. The primers used in RT-PCR were as follows: IE RT-F (5′-atctccatctcatcgtcgtcctcgt-3′) and IE RT-R (5′-ttcgtcgctgtcgctgtcgt-3′) for IE. EICP0 RT-F (5′-tctgctacgtgtgtattacgcgct-3′) and EICP0 RT-R (5′-gtcaaagtccacgctcacctttgt-3′) for EICP0. IR4 RT-F (5′- agagcagcgtttcggagtttagc-3′) and IR4 RT-R (5′-ttcgctgctagaccactttccagt-3′) for IR4. UL5 RT-F (5′-agcccatggaggacgaaatgagta-3′) and UL5 RT-R (5′-aacaacactctttggtgggttgcc-3′) for UL5. ETIF RT-F (5′-caagtttaaacaggtggtgcgcga-3′) and ETIF RT-R (5′-tgaagcgagacgaacacaccttga-3′) for ETIF. GAPDH-F (5′-acatcaagaaggtggtgaagcagg-3′) and GAPDH-R (5′- acaaagtggtcgttgagggcaatg-3′) for human GAPDH. GAPDH-m-F (5′-atcactgccactcagaagactgt-3′) and GAPDH-m-R (5′-accagtggatgcagggatgatgtt-3′) for mouse GAPDH. luc-F (5′-aattctttatgccggtgttgggcg-3′) and luc-R (5′-gctgcgaaatgcccatactgttga-3′) for firefly luciferase. Each sample was assayed in triplicate.

Supplementary Material

Research Highlights.

We examine the functional domains of IR2P that mediates negative regulation. > IR2P inhibits at the transcriptional level. > DNA-binding mutant or TFIIB-binding mutant fails to inhibit. > C-terminal aa 707 to 1116 are required for full inhibition. > Inhibition requires the DNA-binding domain, TFIIB-binding domain, and C-terminus.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mrs. Suzanne Zavecz for excellent technical assistance and Martin Muggeridge for critical reading of the manuscript.

This research was supported by NIH AI22001, by Agriculture and Food Research Initiative Competitive Grant 2008-35204-04438 from the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture, and by NIH center grant P20-RR018724 from the National Center for Research Resources.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ahn BC, Breitenbach JE, Kim SK, O'Callaghan DJ. The EHV-1 IR3 gene that lies antisense to the sole immediate-early (IE) gene is trans-activated by the IE protein and is poorly expressed to a protein. Virology. 2007;363:13–25. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2007.01.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahn BC, Zhang Y, O'Callaghan DJ. The equine herpesvirus 1 (EHV-1) IR3 transcript downregulates expression of the IE gene and the absence of IR3 gene expression alters EHV-1 biological properties and virulence. Virology. 2010;402:327–337. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2010.03.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht RA, Jang HK, Kim SK, O'Callaghan DJ. Direct interaction of TFIIB and the IE protein of equine herpesvirus 1 is required for maximal trans-activation function. Virology. 2003;316:302–312. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2003.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht RA, Kim SK, O'Callaghan DJ. The EICP27 protein of equine herpesvirus 1 is recruited to viral promoters by its interaction with the immediate-early protein. Virology. 2005;333:74–87. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2004.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen GP, Bryans JT. Molecular Epizootiology, pathogenesis, and prophylaxis of equine herpesvirus 1 infections. Prog Vet Microbiol Immunol. 1986;2:78–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedadala GR, Pinnoji RC, Hsia SC. Early growth response gene 1 (Egr-1) regulates HSV-1 ICP4 and ICP22 gene expression. Cell Res. 2007;17(6):546–555. doi: 10.1038/cr.2007.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowles DE, Holden VR, Zhao Y, O'Callaghan DJ. The ICP0 protein of equine herpesvirus 1 is an early protein that independently transactivates expression of all classes of viral promoters. J Virol. 1997;71:4904–4914. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.7.4904-4914.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowles DE, Kim SK, O'Callaghan DJ. Characterization of the trans-activation properties of equine herpesvirus 1 EICP0 protein. J Virol. 2000;74:1200–1208. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.3.1200-1208.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buczynski KA, Kim SK, O'Callaghan DJ. Characterization of the transactivation domain of the equine herpesvirus type 1 immediate-early protein. Virus Res. 1999;65:131–140. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1702(99)00116-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buczynski KA, Kim SK, O'Callaghan DJ. Initial characterization of 17 viruses harboring mutant forms of the immediate early gene of equine herpesvirus 1. Virus Genes. 2005;31:229–239. doi: 10.1007/s11262-005-1801-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrozza MJ, DeLuca NA. Interaction of the viral activator protein ICP4 with TFIIB through TAF250. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:3085–3093. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.6.3085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caughman GB, Lewis JB, Smith RH, Harty RN, O'Callaghan DJ. Detection and intracellular localization of equine herpesvirus 1 IR1 and IR2 gene products by using monoclonal antibodies. J Virol. 1995;69:3024–3032. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.5.3024-3032.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caughman GB, Staczek J, O'Callaghan DJ. Equine herpesvirus type 1 infected cell polypeptides: evidence for immediate-early/early/late regulation of viral gene expression. Virology. 1985;145:49–61. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(85)90200-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charvat RA, Breitenbach JE, Ahn BC, Zhang Y, O'Callaghan DJ. The UL4 protein of equine herpesvirus 1 is not essential for replication or pathogenesis and inhibits gene expression controlled by viral and heterologous promoters. Virology. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2011.01.025. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung AK. DNA nucleotide sequence analysis of the immediate-early gene of pseudorabies virus. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:4637–4646. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.12.4637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garko-Buczynski KA, Smith RH, Kim SK, O'Callaghan DJ. Complementation of a replication-defective mutant of equine herpesvirus type 1 by a cell line expressing the immediate-early protein. Virology. 1998;248:83–94. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray WL, Baumann RP, Robertson AT, Caughman GB, O'Callaghan DJ, Staczek J. Regulation of equine herpesvirus type 1 gene expression: characterization of immediate early, early, and late transcription. Virology. 1987a;158:79–87. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(87)90240-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray WL, Baumann RP, Robertson AT, O'Callaghan DJ, Staczek J. Characterization and mapping of equine herpesvirus type 1 immediate-early, early, and late transcripts. Virus Res. 1987b;8:233–244. doi: 10.1016/0168-1702(87)90018-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grondin B, DeLuca NA. Herpes simplex virus type 1 ICP4 promotes transcription preinitiation complex formation by enhancing the binding of TFIID to DNA. J Virol. 2000;74:11504–11510. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.24.11504-11510.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grundy FJ, Baumann RP, O'Callaghan DJ. DNA sequence and comparative analysis of the equine herpesvirus type 1 immediate-early gene. Virology. 1989;172:223–236. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(89)90124-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan KL, Dixon JC. Eukaryotic proteins expressed in Escherichia coli: an improved thrombin cleavage and purification procedure of fusion proteins with glutathione S-transferase. Anal Biochem. 1991;192:262–267. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(91)90534-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harty RN, O'Callaghan DJ. An early gene maps within and is 3′ co-terminal with the immediate early gene of equine herpesvirus 1. J Virol. 1991;65:3829–3838. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.7.3829-3838.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holden VR, Caughman GB, Zhao Y, Harty RH, O'Callaghan DJ. Identification and characterization of the ICP22 protein of equine herpesvirus type 1. J Virol. 1994;68:4329–4340. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.7.4329-4340.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holden VR, Harty RN, Yalamanchili RR, O'Callaghan DJ. The IR3 gene of equine herpesvirus type 1: a unique gene regulated by sequences within the intron of the immediate-early gene. DNA Seq. 1992;3:143–152. doi: 10.3109/10425179209034010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holden VR, Zhao Y, Thompson Y, Caughman GB, Smith RH, O'Callaghan DJ. Characterization of the regulatory function of the ICP22 protein of equine herpesvirus type 1. Virology. 1995;210:273–282. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang HK, Albrecht RA, Buczynski KA, Kim SK, Derbigny WA, O'Callaghan DJ. Mapping the sequences that mediate interaction of the equine herpesvirus 1 immediate-early protein and human TFIIB. J Virol. 2001;75:10219–10230. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.21.10219-10230.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SK, Ahn BC, Albrecht RA, O'Callaghan DJ. The unique IR2 protein of equine herpesvirus 1 negatively regulates viral gene expression. J Virol. 2006;80:5041–5049. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.10.5041-5049.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SK, Bowles DE, O'Callaghan DJ. The γ2 late glycoprotein K promoter of equine herpesvirus 1 is differentially regulated by the IE and EICP0 proteins. Virology. 1999;256:173–179. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.9608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SK, Buczynski KA, Caughman GB, O'Callaghan DJ. The equine herpesvirus 1 immediate-early protein interacts with EAP, a nucleolar-ribosomal protein. Virology. 2001;279:173–184. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SK, Holden VR, O'Callaghan DJ. The ICP22 protein of equine herpesvirus 1 cooperates with the IE protein to regulate vial gene expression. J Virol. 1997;71:1004–1012. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.2.1004-1012.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SK, Jang HK, Albrecht RA, Derbigny WA, Zhang Y, O'Callaghan DJ. Interaction of the equine herpesvirus 1 EICP0 protein with the immediate-early (IE) protein, TFIIB, and TBP may mediate the antagonism between the IE and EICP0 proteins. J Virol. 2003;77:2675–2685. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.4.2675-2685.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SK, O'Callaghan DJ. Molecular Characterization of the equine herpesvirus 1 ETIF promoter region and translation initiation site. Virology. 2001;286:237–247. doi: 10.1006/viro.2001.0988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SK, Smith RH, O'Callaghan DJ. Characterization of DNA binding properties of the immediate-early gene product of equine herpesvirus type 1. Virology. 1995;213:46–56. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Callaghan DJ, Cheevers WP, Gentry GA, Randall CC. Kinetics of cellular and viral DNA synthesis in equine abortion (herpes) virus infection L-M cells. Virology. 1968;36:104–114. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(68)90120-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Callaghan DJ, Gentry GA, Randall CC. Comprehensive virology. Vol. 2. Plenum Publishing Corp.; New York: 1983. The equine herpesviruses. (2). [Google Scholar]

- O'Callaghan DJ, Osterrieder N. Equine herpesviruses. In: Webster RG, Granoff A, editors. Encyclopedia of virology. 2nd. Academic Press; San Diego: 1999. pp. 508–515. [Google Scholar]

- Perdue ML, Kemp MC, Randall CC, O'Callaghan DJ. Studies of the molecular anatomy of the L-M strain of equine herpesvirus type 1: protein of nucleocapsid and intact virion. Virology. 1974;59:201–216. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(74)90216-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. 2nd. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; Cold Spring Harbor, NY: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Sampath P, DeLuca NA. Binding of ICP4, TATA-binding protein, and RNA polymerase II to herpes simplex virus type 1 immediate-early, early, and late promoters in virus-infected cells. J Virol. 2008;82:2339–2349. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02459-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith CA, Bates P, Rivera-Gonzalez R, Gu B, DeLuca NA. ICP4, the major transcriptional regulatory protein of herpes simplex virus type 1, forms a tripartite complex with TATA-binding protein and TFIIB. J Virol. 1993;67:4676–4687. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.8.4676-4687.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith RH, Caughman GB, O'Callaghan DJ. Characterization of the regulatory functions of the equine herpesvirus 1 immediate-early gene product. J Virol. 1992;66:936–945. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.2.936-945.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith RH, Holden VR, O'Callaghan DJ. Nuclear localization and transcriptional activation activities of truncated versions of the immediate-early gene product of equine herpesvirus 1. J Virol. 1995;69:3857–3862. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.6.3857-3862.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]