Abstract

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are a class of non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) and post-transcriptional gene regulators shown to be involved in pathogenesis of all types of human cancers. Their aberrant expression as tumor suppressors can lead to cancerogenesis by inhibiting malignant potential, or when acting as oncogenes, by activating malignant potential. Differential expression of miRNA genes in tumorous tissues can occur due to several factors including positional effects when mapping to cancer-associated genomic regions, epigenetic mechanisms and malfunctioning of the miRNA processing machinery, all of which can contribute to a complex miRNA-mediated gene network misregulation. They may increase or decrease expression of protein-coding genes, can target 3’-UTR or other genic regions (5'-UTR, promoter, coding sequences), and can function in various subcellular compartments, developmental and metabolic processes. Because expanding research on miRNA-cancer associations has already produced large amounts of data, our main objective here was to summarize main findings and critically examine the intricate network connecting the miRNAs and coding genes in regulatory mechanisms, their function and phenotypic consequences for cancer. By examining such interactions we aimed to gain insights for development of new diagnostic markers as well as identify potential venues for more selective tumor therapy. To enable efficient examination of the main past and current miRNA discoveries, we developed a web based miRNA timeline tool that will be regularly updated (http://www.integratomics-time.com/miRNA_timeline). Further development of this tool will be directed at providing additional analyses to clarify complex network interactions between miRNAs, other classes of ncRNAs and protein coding genes and their involvement in development of diseases including cancer. This tool therefore provides curated relevant information about the miRNA basic research and therapeutic application all at hand on one site to help researchers and clinicians in making informed decision in regards to their miRNA cancer-related research or clinical practice.

Keywords: microRNA (miRNA), cancer, oncogene, tumor suppressor, epigenetics, genetic variation, transcriptional regulation

Cancer develops through a complex multistep process involving structural and expression abnormalities of genes, including those encoding microRNAs (miRNAs) (1,2). MiRNAs are a class of non-protein coding RNAs that post-transcriptionally regulate expression of the target mRNAs. MiRNAs that have been associated with cancer are referred to as oncomiRs (3,4). The role of miRNAs in cancer was hinted early in the history of miRNA research by three important observations (5): (1) miRNAs are involved in cell proliferation and apoptosis (6,7), (2) miRNA genes are frequently located at fragile sites and cancer-associated genomic regions (CAGRs) (8), and (3) miRNA expression is deregulated in malignant tumors and tumor cell lines in comparison with normal tissues (1,9,10). However, the first direct evidence of their oncogenic activity was reported when MIR15A and MIR16-1 were found to be deleted or down-regulated in most chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) patients (11). Recent analyses of miRNA genes, their targets, processing machinery, genetic polymorphisms, and epigenetic modifications revealed that miRNA-mediated regulation in gene regulatory networks involves a far more complex system than initially expected. We therefore aimed here to present the main miRNA related discoveries in an online timeline format which will be updated regularly with new discoveries (http://www.integratomics-time.com/miRNA_timeline). A summary of the timeline is presented in Table 1. We also presented an online list of the most extensive review articles sorted according to the topic of miRNA research in cancer; e.g. (1) general, (2) polymorphisms, (3) miRNA host genes, (4) transcription factors, (5) epigenetics, etc. (http://www.integratomics-time.com/miRNA_timeline/reviews). This review and web-based tool developed should enable efficient examination of past and current miRNA-cancer publications and enable critical exploration of interaction networks involved. Curated and regularly updated information at one site will be useful for researchers and clinicians to guide their miRNA basic research and therapeutic applications in clinical practice.

Table 1.

A timeline of main miRNA discoveries.

| year | discovery | species | associated with |

reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1960s | non-protein coding transcripts (activator RNAs) regulate gene activity | eukaryotes | (Britten and Davidson 1969) | |

| 1993 | first miRNA (lin-4) discovered | C. elegans | (Lee, Feinbaum, and Ambros 1993) | |

| 2000 | discovered microRNA (MIRLET7) | C. elegans | (Reinhart et al. 2000) | |

| 2000 | RNAi "unit": 21–23 nt | Drosophila | (Zamore et al. 2000) | |

| 2001 | a large class of small RNAs (named miRNAs) are co-expressed in clusters and have potential regulatory roles |

C. elegans, invertebrates, vertebrates |

(Lau et al. 2001) (Lagos-Quintana et al. 2001) (Lee and Ambros 2001) |

|

| 2001 | Dicer in miRNA biogenesis pathway |

C. elegans, Drosophila |

(Grishok et al. 2001) (Hutvágner et al. 2001) |

|

| 2002 | miRNAs discovered in plants | plants | (Reinhart et al. 2002) (Rhoades et al. 2002) |

|

| 2002 | miRNA alterations found in cancer cells (MIR15A and MIR16-1 deleted or downregulated in most chronic lymphocytic leukemias) | Human | cancer | (Calin et al. 2002) |

| 2004 | more than 50% of miRNA genes are located in cancer-associated genomic regions or fragile sites | human | cancer | (Calin et al. 2004) |

| 2004 | miRNA as diagnostic/prognostic biomarker | human | cancer | (Takamizawa et al. 2004) |

| 2004 | co-expression of miRNAs and their host genes | mouse | (Rodriguez et al. 2004) | |

| 2005 | miRNA-target interaction relevant to cancer |

C.elegans, human |

cancer | (Johnson et al. 2005) |

| 2005 | altered expression of miRNAs affects tumor formation/growth in vivo | Human | cancer | (He et al. 2005) |

| 2005 | connection between miRNAs and the MYC oncogene | human, rat | cancer | (O'Donnell et al. 2005) |

| 2005 | inhibition of miRNA by antagomirs in mammals | mouse | (Krützfeldt et al. 2005) | |

| 2006 | molecule of the year (MIR155 and MIRLET7A2) | human | cancer | (Yanaihara et al. 2006) |

| 2006 | epigenetic regulation (DNA methylation and histone deacetylase inhibition) of miRNAs | human | cancer | (Saito et al. 2006) |

| 2007 | miRNA target sites can also occur in 5'-UTR | C. elegans | (Lytle, Yario, and Steitz 2007) | |

| 2007 | miRNAs deregulation in cancer metastasis | human | cancer | (Ma, Teruya-Feldstein, and Weinberg 2007) |

| 2007 | miRNAs can up-regulate mRNA expression and initiate the translation of proteins | human | (Vasudevan, Tong, and Steitz 2007) | |

| 2007 | miRNAs can affect epigenetic changes and cause the reactivation of silenced tumor suppressor genes | human | cancer | (Fabbri et al. 2007) |

| 2007 | miRNAs can regulate ncRNAs from the category of long ultraconserved genes (UCGs) | human | cancer | (Calin et al. 2007) |

| 2007 | miRNAs carrying hexanucleotide terminal motifs are enriched in the nucleus | (Hwang, Wentzel, and Mendell 2007) | ||

| 2008 | miRNA (MIR373) targets promoter sequences and induces gene expression | human | (Place et al. 2008) | |

| 2008 | miRNAs can transcriptionally silence gene expression | human | (Kim et al. 2008) | |

| 2008 | functional single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) in the miRNA seed region | human | cancer | (Shen et al. 2008) |

| 2008 | miRNA binding sites located within mRNA-coding sequence | (Tay et al. 2008) | ||

| 2009 | proof of concept of miRNA delivery as cancer therapy | human, mouse |

cancer | (Kota et al. 2009) |

| 2010 | miRNA as molecular decoys | human, mouse |

cancer | (Eiring et al. 2010) |

| 2010 | miRNAs predominantly cause mRNA destabilization | human, mouse |

(Guo et al. 2010) | |

| 2010 | pseudogene PTEN saturates miRNA binding sites | human | cancer | (Poliseno et al. 2010) |

| 2010 | overexpression of a single miRNA is sufficient to cause cancer | mouse | cancer | (Medina, Nolde, and Slack 2010) |

| 2011 | competing endogenous RNA (ceRNA) communicate with and regulate other RNA transcripts by competing for shared miRNAs | human | (Salmena et al. 2011) |

Interplay between microRNA and cancer genes

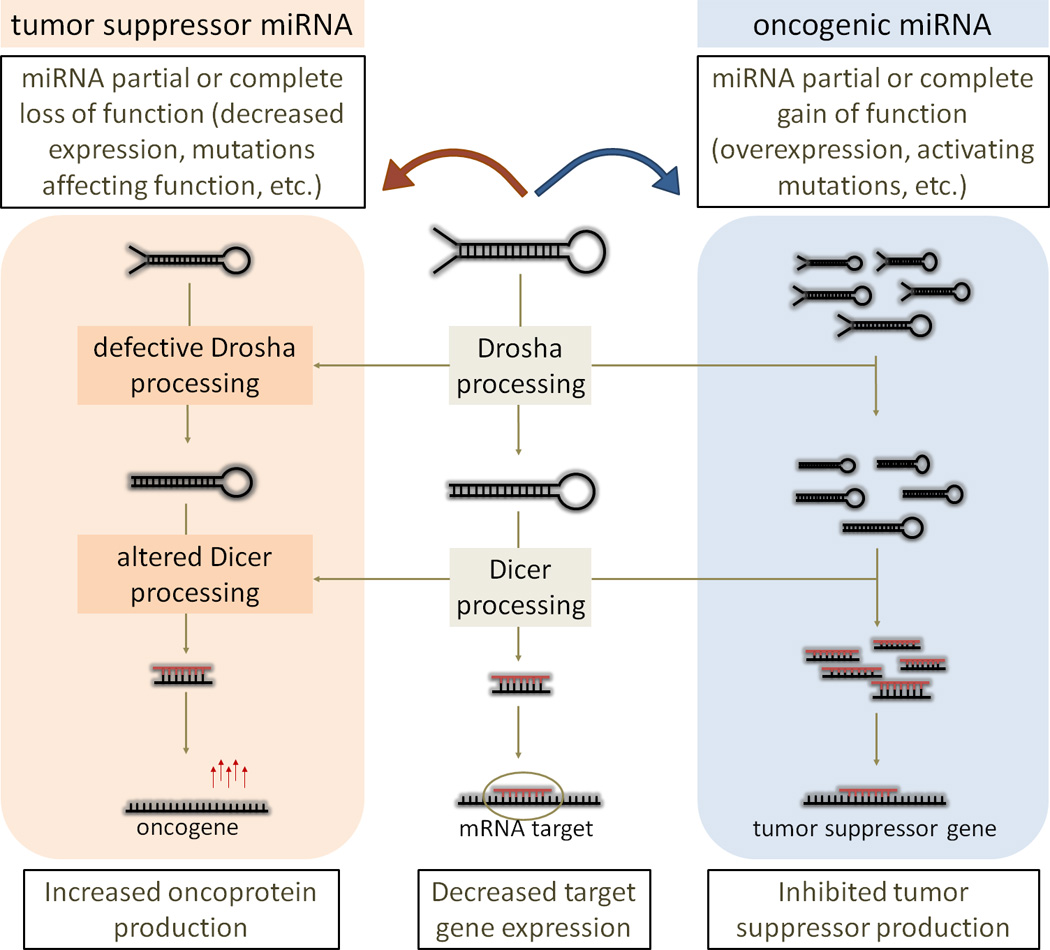

A predominant reason for cancerogenic cell transformation is a combined interaction of both tumor suppressors and oncogenes. MiRNAs can function as oncogenes, by activating malignant potential, or as tumor suppressors, by blocking the cell’s malignant potential (3,12). Modulation of miRNA biogenesis pathway can also promote tumorigenesis through increased repression of tumor suppressors and/or through incomplete repression of oncogenes (Figure 1). MiRNAs can affect all major hallmarks of malignant cells: self-sufficiency in growth signals, evasion of apoptosis, insensitivity to anti-growth signals, sustained angiogenesis, limitless replicative potential, and tissue invasion and metastasis (13,14). MiRNA deregulation can therefore contribute to oncogenesis in various ways. Two studies described a more direct relationship between a miRNA cluster MIR17HG, MYC and cancer oncogenic pathway, revealing a complex genetic circuit that regulates cell proliferation, growth, and apoptosis (15,16). Overexpression of the MIR17HG cluster was found to act with c-Myc expression to accelerate tumorigenesis in mice; therefore this cluster was suggested to be a potential non-coding oncogene (15). On the other hand, the MIRLET7 family showed tumor suppressor activity by regulating the expression of a proto-oncogene, the RAS protein, which is a membrane-associated signaling protein that regulates cell growth (17). Several studies therefore support the view that miRNAs area class of non-coding nucleic acids that can function as oncogenes or as tumor suppressors contributing to oncogenesis.

Figure 1.

Tumorigenesis promoted by modulation of miRNA biogenesis pathway.

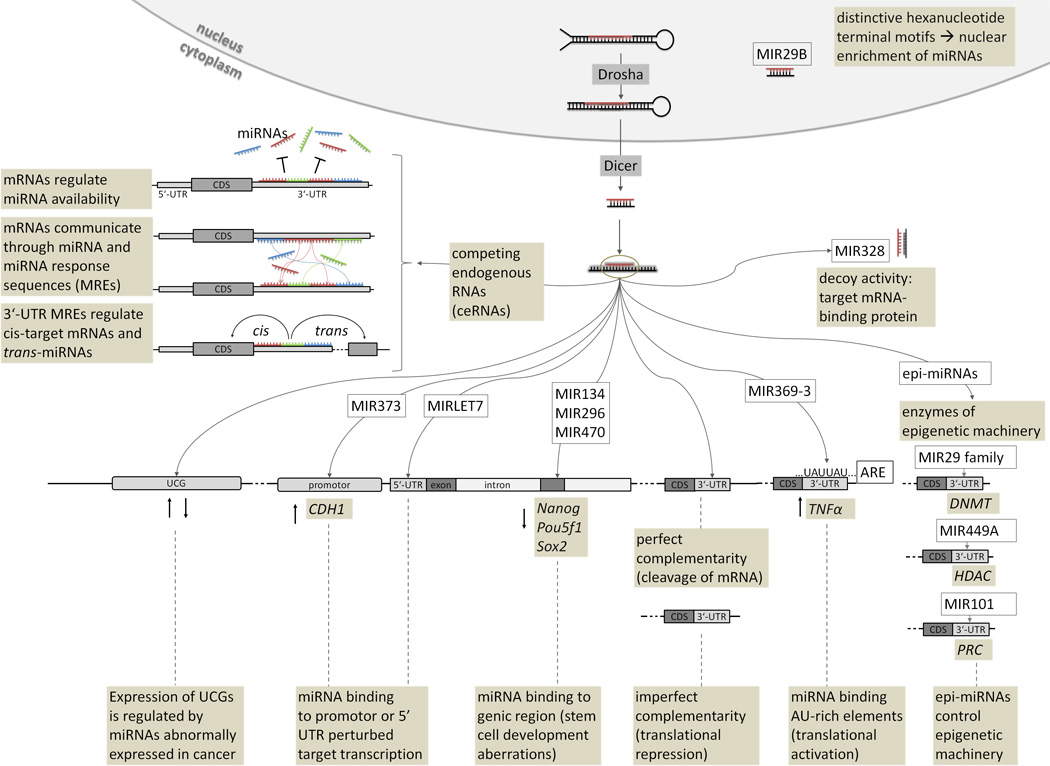

It was estimated that about one-third of human mRNAs are considered as miRNA targets (18). Vertebrate miRNAs target about 200 transcripts each and more than one miRNA might coordinately regulate a single target (19) thereby providing a basis for complex networks. Predicted targets for the differentially expressed miRNAs inhuman solid tumors have been shown to be significantly enriched for protein-coding tumor suppressors and oncogenes (20). The standard “dogma”, that miRNAs target the 3’-UTR of genes and downregulate the expression of protein-coding genes in cytoplasm, has been expanded with the following additional observations: (1) miRNAs can be localized in the nucleus (21), (2) miRNAs target other genic regions in addition to 3’-UTR (5’-UTR, promoter regions, coding regions) (22,23,24,25), and (3) miRNA upregulate translation (26,23) (Figure 2). It has been shown that human miRNA MIR369-3 targets AU-rich elements (AREs) in the target gene TNF to activate translation of proteins whose expression they normally repress during cell proliferation (26). It has also been shown that miRNAs can affect transcription at the promoter level: human MIR373 binds to the E-cadherin (CDH1) promoter and induces transcription (23). MiRNA-dependent mRNA repression also occurs through binding sites located in mRNA coding sequences (CDS), as shown for miRNAs with targets in developmentally regulated genes (24,25). In addition to miRNA-mediated gene silencing through base pairing with mRNA targets, miRNAs also interfere with the function of regulatory proteins (decoy activity) (27). In particular, MIR328 binds to poly-C binding protein 2 (PCBP2), alternatively known as heterogeneous ribonucleoprotein (hnRNP) E2, independently of the miRNA’s seed region and prevents its interaction with the target mRNA (27). Downregulation of MIR328 in chronic myelogenous leukemia allowed PCBP2 inhibition of myeloid differentiation and, as a result, led to tumor progression (Eiring et al. 2010). Other ncRNAs, such as noncoding ultraconserved genes (UCGs), have been found to be consistently altered at the genomic level in a high percentage of leukemias and carcinomas and may interact with miRNAs in leukemias (28). The findings provide support for a model in which both coding and noncoding genes are involved and cooperate in human tumorigenesis. Recently, the role of coding and non-coding RNAs has been emphasized and grouped in an unifying theory of competing endogenous RNAs (ceRNAs) that can regulate one another through their ability to compete for miRNA binding (29). The ceRNA hypothesis suggests that long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) may elicit their biological activity through the ability to act as endogenous decoys for miRNAs and that such activity would in turn affect the distribution of miRNAs on their targets (29). CeRNAs may therefore be active partners in miRNAs regulation exerting effects on their expression levels, which may have important implications in pathological conditions, such as cancer.

Figure 2.

Cross talk between miRNAs and target.

ARE: AU-rich elements; CDS: coding sequence; CDH1: E-cadherin; DNMT: DNA methyltransferase; HDAC: histone deacetylase; Nanog: Nanog homeobox; Pou5f1: POU class 5 homeobox 1 (synonym: Oct4); PRC: polycomb repressive complex; Sox2: sex determining region Y box 2; TNFα: tumor necrosis factor alpha; UCG: ultraconserved gene.

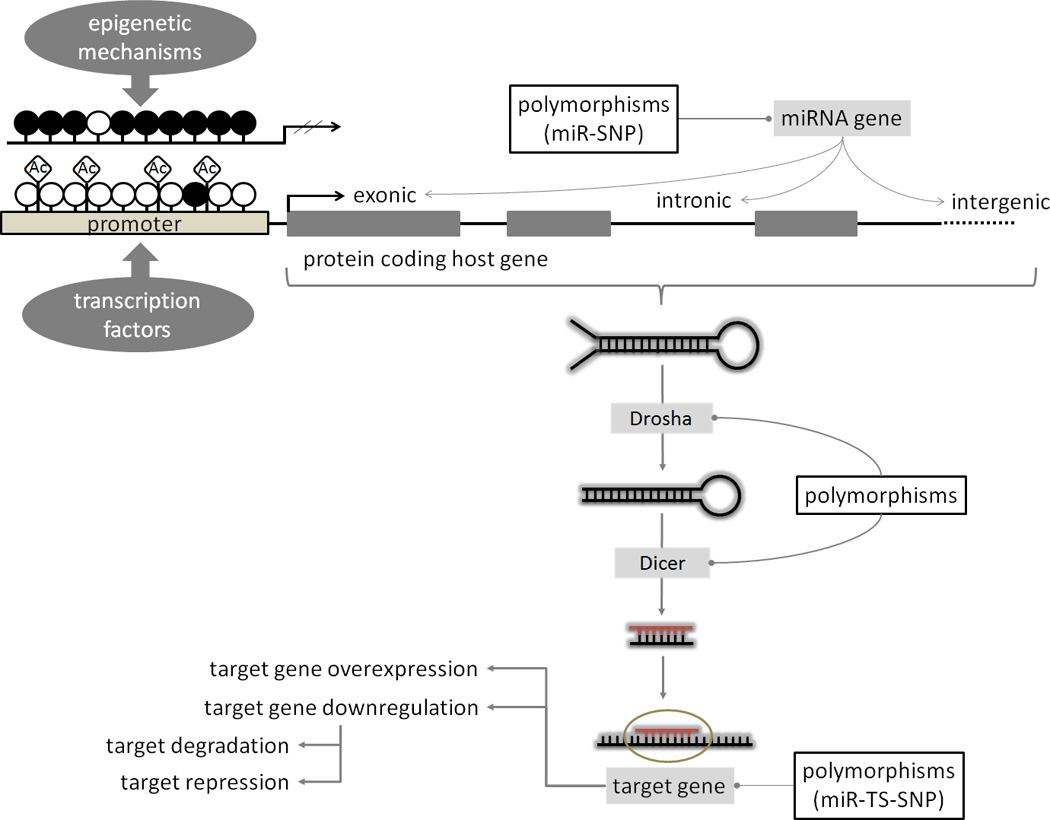

The causes of dysregulated expression can be explained by analyzing the many layers of gene network regulation, including the miRNA gene location in cancer-associated genomic regions, epigenetic mechanisms, and alterations in the miRNA processing machinery (30,31) (Figure 3). Because each miRNA has numerous targets, inherited minor variations in miRNA expression may have important consequences for the expression of various protein-coding oncogenes and tumor suppressors involved in malignant transformation. Accumulation of additional somatic abnormalities in protein-coding genes or ncRNAs, including miRNAs, is necessary for the full development of the malignant phenotype (32). The expanding field of miRNA and cancer research therefore requires the consideration of interplay that connects the regulatory mechanisms and their function into an intricate network.

Figure 3.

MiRNA biogenesis and mechanisms of regulation. MiRNA expression and regulation can be affected by transcriptional deregulation, epigenetic modifications (DNA methylation and/or histone acetylation), polymorphisms (SNPs) present in miRNA genes, their processing machinery and targets.

miR-SNP: single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the miRNA gene; miR-TS-SNP: SNPs in the miRNA target sites; Ac:acetyl groups; empty circles: unmethylated CpG sites; filled circles: methylated CpG sites

Single nucleotide polymorphisms in miRNA genes, their targets and processing machinery

Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) of miRNA precursors, their target sites, and miRNA processing machinery were reported to affect miRNA function and lead to phenotypic effects (33). When referring to SNPs occurring in miRNA genes the term “miR-SNPs” is used, and “miR-TS-SNP” for SNPs located within miRNA target binding sites (34,35) (Figure 3). Even though many miRNA sequence variations observed in cancer alter the secondary structure with no demonstrated effects on miRNA processing (36), several recent reports show that SNPs located in miRNA genes are associated with cancer susceptibility (37,35,38). It was observed that miR-SNPs can affect function by modulating the miRNA precursor transcription, processing and maturation (39), or miRNA-mRNA interaction (17). Sequence variations in the mature miRNA, especially in the seed region (miR-seed-SNP), may have an effect on miRNA target recognition (40). Human miRNAs comprising miR-seed-SNPs have been shown to be frequently located within quantitative trait loci (QTL), chromosome fragile sites, and cancer susceptibility loci (40). Because of the miRNA-target interaction, the miR-SNPs (and/or miR-seed-SNPs) and miR-TS-SNPs function in the same manner to create or destroy miRNA binding sites. Chin et al (41) demonstrated a SNP that modified the MIRLET7 binding site in the v-Ki-ras 2 Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog (KRAS) and was significantly associated with increased risk for non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Even though miR-TS-SNPs were shown to influence susceptibility to tumorigenesis (42), additional association studies and follow-up functional experiments should still be applied to provide a clearer view on the interplay of these variations in disease development. In order for the miR-TS-SNP to be functional it must have a proven association with cancer, both miRNA and its predicted target must be expressed in the tissue, and allelic changes must result in different binding of miRNA and affect expression of the target gene (43). Nevertheless, we can conclude from available published studies that “miR-SNPs” provide an additional layer of functional variability of miRNAs in cancerogenesis and that ongoing studies using next generation sequencing technology and systems biology analyses are likely to provide additional evidence for miR-SNPs-cancer associations in the near future.

SNPs in miRNA-processing machinery may also have profound effects on the phenotype. SNPs that affect the proteins involved in miRNA biogenesis may have deleterious effects on the miRNAome and global repression of miRNA maturation was shown to lead to tumorigenesis (44). Several studies reported that genetic polymorphisms of the proteins involved in miRNA machinery affect cancer susceptibility (45,46,47). SNPs in the GEMIN4 gene were significantly associated with altered renal cell carcinoma (45) and bladder cancer risk (46), SNP in the 3′ UTR of DICER1 was associated with an increased risk of premalignant oral lesions in individuals with leukoplakia and/or erythroplakia (47). The essential part inmiRNA variation studies is identification of SNPs located within miRNA genes, their processing machinery, and targets, with bioinformatics tools such as Patrocles (48), miRNASNiPer (40), and PolymiRTS (49). These tools intercalate and cross-reference the data from dbSNP and as such aid in the search for miRNA-related polymorphisms. Although these tools provide useful information on existence of miR-SNPs and their possible effects on target regulation, we still need more experimental data to gain insights on which miR-SNP locations and types of nucleotide substitutions have the most profound effects on cancerogenesis. Such knowledge would have diagnostic power in predicting a person's risk for cancer development based on his/her high risk miR-SNP genotype. Additionally, in people carrying low risk miR-SNP alleles that have developed primary tumors, genotyping for miR-SNPs of tumor biopsies may reveal somatic mutations that generated high risk miR-SNPs potentially aiding in the correct diagnosis of the cancer type and in therapeutic decisions.

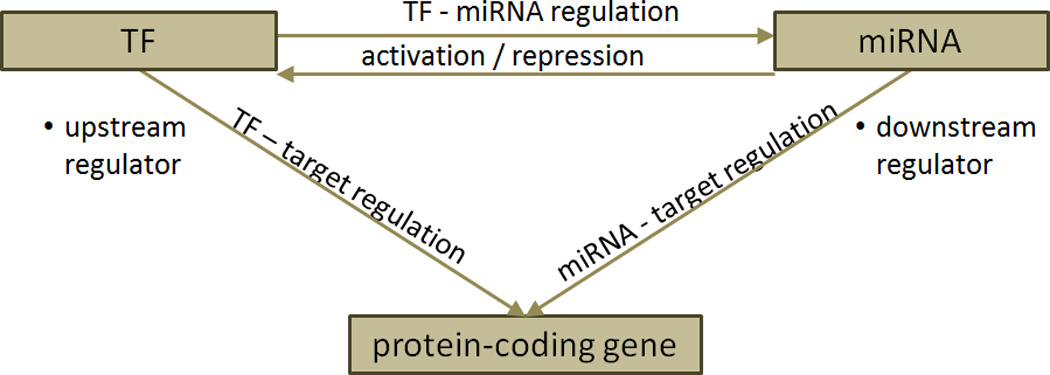

Transcription factor-miRNA regulatory network

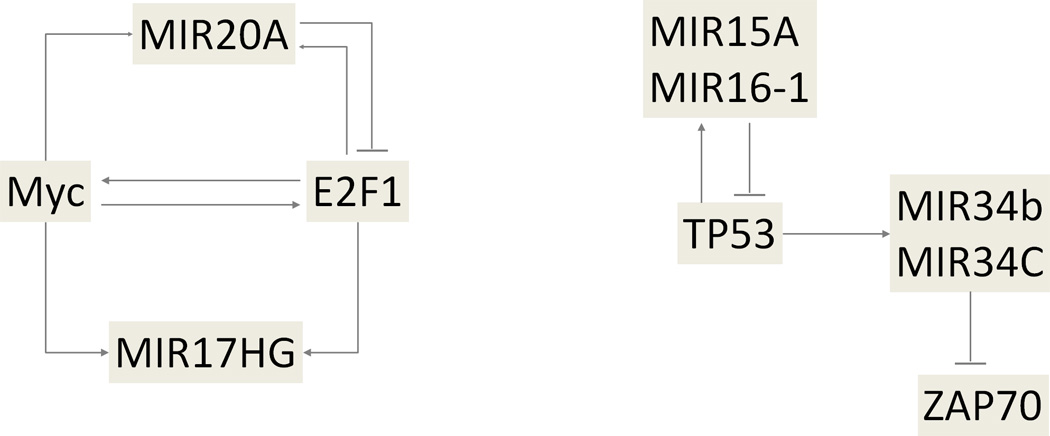

MiRNAs are transcriptional and post-transcriptional gene regulators and, like protein-coding genes, are also regulated by transcription factors (TF), another class of gene regulators that act at the transcriptional level. MiRNA genes are also linked with TFs in complex regulatory networks where they reciprocally regulate one another (50) (Figure 4a). It is estimated that up to 43% of human genes are under combined regulation at transcriptional and post-transcriptional level (51). Due to TF’s and/or miRNA’s involvement in cancer, the disruption of their co-regulation may be associated with oncogenesis. O’Donnell et al (16) found that the MIR17HG cluster is transactivated by MYC, an oncogene frequently dysregulated in cancer. Similarly, TP53, a tumor-suppressor gene whose pathway mutations have been discovered in many cancer types, was found to regulate expression of MIR34A (52). On the other hand, overexpression of MIR125B has been shown to reduce levels of TP53 protein and suppress apoptosis in human cancer cells, whereas knockdown of MIR125B elevates the level of TP53 (53).

Figure 4.

TF-miRNA regulatory network. (a) Basic network motif in transcriptional and post-transcriptional gene regulation. (b) Schematic representation of examples of regulatory circuit, including MIR17HG – MYC – E2F1 pathway (left) and the MIR15A/16-1 cluster – TP53 – MIR34B/34C cluster – ZAP70 pathway (right).

Coordinated miRNA/TF regulation engage in a wider diversity of biological processes which can have a higher specificity than regulation within only one layer of regulation (54). MiRNAs and TFs have been found to cooperate in tuning gene expression, by which miRNAs were found to preferentially target genes with transcriptional regulation complexity (55,56). In regulatory networks, miRNAs and TFs can reciprocally regulate one another and form feedback loops, or form feed forward loops in which both TFs and miRNAs regulate their target genes (Figure 4b). An example of a complex network interaction in cancer was described by O’Donnell et al (16) who found that MIR20A modulates the translation of E2F transcription factor 1 (E2F1) mRNA by binding to its 3’-UTR. Moreover, E2F1 binds to the promoter of the MIR17HG cluster, activating its transcription (16). A miRNA/protein feedback circuitry (miRNA/TP53) has been found to be associated with pathogenesis and prognosis of CLL (57). In 13q deleted CLLs theMIR15A/16-1 cluster directly targets TP53 and its downstream effectors. In leukemic cell lines and primary B-CLL cells TP53 stimulates the transcription of both MIR15A/16-1 and MIR34B/34C clusters, and the MIR34B/34C cluster directly targeted the ZAP70 kinase. This mechanism provides a novel pathogenetic model for the association of 13q deletions with the indolent form of CLL that involves miRNAs, TP53 and ZAP70 (57). Complex patterns in miRNA-TF interplay have also been computationally analyzed and the generated databases (TransmiR and dPORE-miRNA), present valuable regulatory framework for future experimental analyses (58,59). Transcription factor -miRNA regulation is therefore not confined only to the “classical” action of transcription factors on miRNA promoters and their regulation but is extended to reciprocal and mutual interactions forming a complex regulatory network.

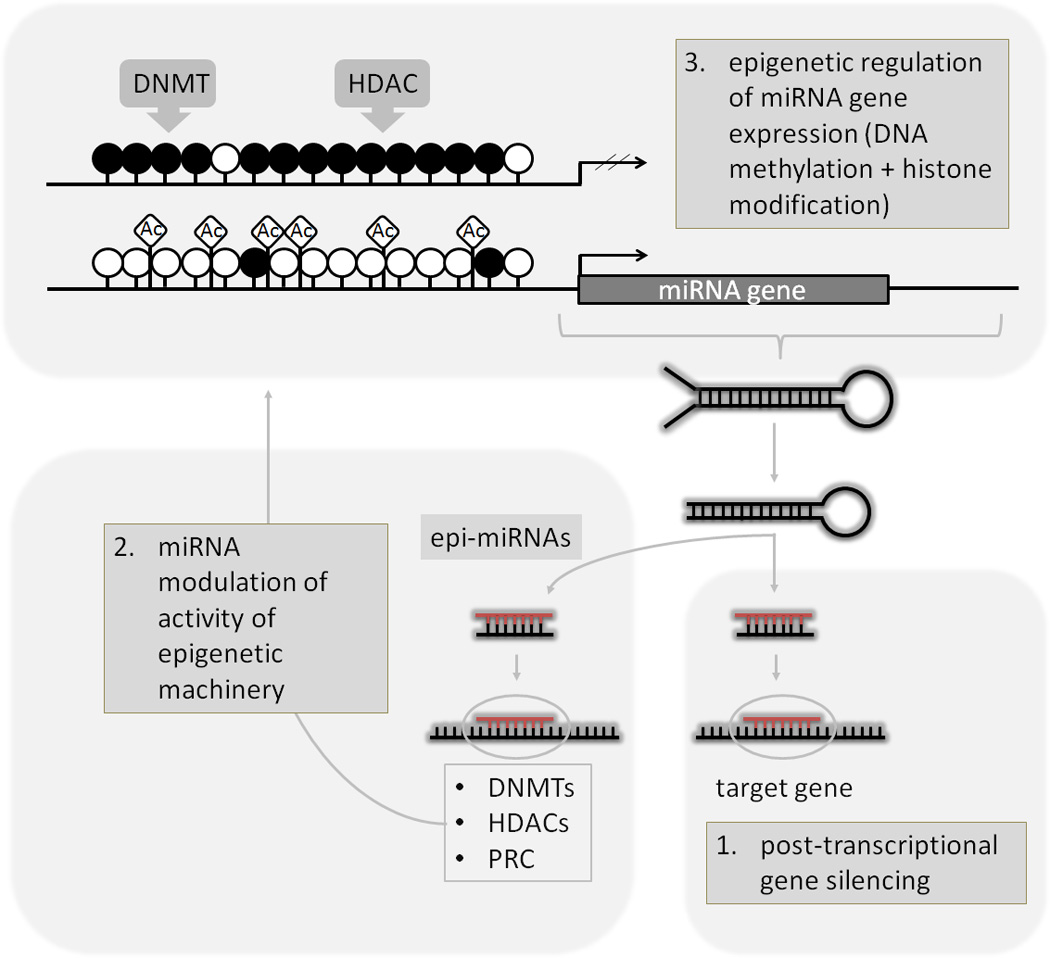

MiRNA and epigenetics in cancer

Several aspects of epigenetic regulation have been found to be associated with miRNAs: (1) they regulate target gene expression; regulation of gene expression mediated by miRNAs is frequently reported in cancer and presents one component of an interacting network of epigenetic mechanisms. (2) A subclass of miRNAs (epi-miRNAs) directly controls the epigenetic machinery through a regulatory loop by targeting its regulating enzymes. (3) MiRNA expression could be affected by CpG island hypermethylation-associated silencing in the promoter region or CpG de-methylation-associated activation of miRNA promoters (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Epigenetic concepts of miRNA regulatory network. DNMTs: DNA methyltransferases; HDACs: histone deacetylases; PRC: polycomb repressive complex; Ac:acetyl groups;empty circles: unmethylated CpG sites; filled circles: methylated CpG sites.

Several epi-miRNAs have been shown to be directly connected to the epigenetic machinery by regulating the expression of its regulatory enzymes (60,61,62). The first epi-miRNAs were identified in lung cancer in a study where MIR29 family (MIR29A, MIR29B, and MIR29C) was shown to target and downregulate de novo DNA methyltransferases (DNMT3A and DNMT3B) (60). Additionally, MIR29B has been shown to induce global DNA hypomethylation and tumor suppressor gene re-expression in acute myeloid leukemia by targeting directly DNMT3A and 3B and indirectly the DNMT (DNMT1) (63). This led to demethylation of CpG islands in the promoter regions of tumor-suppressor genes, allowing their reactivation and a loss of the cell’s tumorgenicity (60). It was also reported that MIR449A targets histone deacetylase 1 (HDAC1), a gene that is frequently overexpressed in many types of cancer, and consecutively induces growth arrest in prostate cancer (61). Also, MIR101 was shown to directly modulate the expression of enhancer of zeste homolog 2 (EZH2), a catalytic subunit of the polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2), which mediates epigenetic silencing of tumor-suppressor genes in cancer (62).

Expression of miRNA genes have also been found to be silenced in human tumors by epigenetic mechanisms, such as aberrant hypermethylation of CpG islands encompassing and/or in proximity of miRNA genes, or by histone acetylation (64). The first evidence that altered methylation status can deregulate the expression of a miRNA in cancer was reported by Saito et al (65). MIR127, embedded within a CpG island promoter, was silenced in several cancer cells, but strongly upregulated after treatment with a hypomethylating agent (DNMT inhibitor). A similar scenario was observed with MIR124A whose function can be restored by erasing DNA methylation and has functional consequences on cyclin D kinase 6 (CDK6) activity (66). On the other hand, Brueckner et al (67) observed that hypomethylation of MIRLET7A3 facilitates reactivation of the gene and elevates expression of MIRLET7A3 in human lung cancer cell lines, which resulted in enhanced tumor phenotypes. Compared with protein-coding genes, human oncomiRs were found to have an order of magnitude higher methylation frequency (64,68). Future studies of epigenetic regulation of miRNA expression coupled to downstream signaling pathways are likely to lead to development of novel drug targets in cancer therapy (68).

MiRNA expression profiles / signatures

Profiling of miRNAs is used to document their expression variability, and it was shown to be more accurate for cancer classification than by using sets of known protein-coding genes (32,69). In cancer, the loss of tumor-suppressor miRNAs enhances the expression of target oncogenes, whereas increased expression of oncogenic miRNAs can repress target tumor suppressor genes. Paired expression profiles of miRNAs and mRNAs can be used to identify functional miRNA-target relationships with high precision (70). The aberrant expression of miRNAs in cancer is characterized by abnormal levels of expression for mature and/or precursor miRNA transcripts in comparison to those in the corresponding normal tissue. Lu et al (69) observed a general down-regulation of miRNAs in tumor samples compared to normal tissue samples. It was also found that miRNA expression profiles could differentiate human cancers according to their developmental origin, with cancers of epithelial and hematopoietic origin having distinct miRNA profiles (69). The first evidence that miRNA expression could be altered in cancer came from the observation by Carlo Croce group that MIR15A/MIR16-1 gene cluster is located in a genomic region frequently deleted in CLL and that their expression is frequently downregulated or deleted in CLL (11). Afterwards, numerous studies examined aberrant miRNA expression signatures in cancer. A review analyzing 58 studies (71) revealed 70 differentially expressed miRNAs in cancers, which were reported in at least five studies. The causes of widespread alterations of miRNA expression in cancer cells include different factors, such as: the location of miRNAs at cancer-associated genomic regions (CAGR) (8), epigenetic regulation (72), and abnormalities in genes and proteins of the miRNA processing machinery (73). Since deregulated miRNA expression is an early event in tumorigenesis, measuring the levels of circulating miRNAs may also be useful for early cancer detection. Fluid-expressed miRNAs have been discussed as reliable cancer biomarkers and treatment response predictors as well as potential new patient selection criteria for clinical trials (74). Profiling of miRNA expression correlates with clinical and biological characteristics of tumors and has enabled the identification of signatures associated with diagnosis, staging, progression, prognosis, and response to treatment of human tumors (75). MiRNA fingerprinting therefore represents an additional tool in the clinical oncology.

MiRNAs as diagnostic, prognostic and therapeutic targets in cancer

Based on their regulatory function, miRNAs are important players in the oncogenic signaling pathway, which is why they should be considered in cancer diagnosis and prognosis. As already mentioned, miRNA expression profiles contain much information that could explain developmental processes in cancer, and are disrupted by different mechanisms mentioned in the previous section on miRNA expression profiles / signatures (32). A general down-regulation of miRNAs was observed in tumor samples, compared to normal tissue samples. A unique miRNA signature is associated with prognostic factors and disease progression in CLL. Mutations in miRNA transcripts are common and may have functional importance (76).

Several studies have indicated various strategies for therapeutic usage of miRNAs in cancer. Four different strategies for potential therapies were proposed (77): (1) anti-miRNA oligonucleotides (AMOs), inhibitory molecules that block the interactions between miRNA and its target mRNA by competition (78). (2) MiRNA sponges, synthetic miRNAs that contain multiple binding sites for an endogenous miRNA and prevent the interaction between miRNA and its endogenous targets (79). Ebert et al (79) have also designed these sponges with complementary seed regions, which effectively repress an entire miRNA seed family. (3) MiRNA masking refers to a sequence with perfect complementarity to the binding site for an endogenous miRNA in the target gene, which can in turn form a duplex with the target mRNA with higher affinity and blocking the access of the miRNA (80). (4) Small molecule inhibitors against specific miRNAs refer to chemicals or reagents able to specifically inhibit miRNA synthesis. One such example is azobenzene, a specific and efficient inhibitor of MIR21 biogenesis (81). Apart from aforementioned four therapeutic approaches proposed by Li et al. (77) others have proposed and demonstrated alternative strategies such as restoring activity of tumor-suppressive miRNAs to rescue its anti-tumor function, (82,83,84). Some studies also suggest that by selecting miRNAs that are highly expressed in normal tissues but lost in cancer cells can be used in the general strategy for restoring tumor suppressor miRNAs as therapy (85,86,87). Another approach to utilize miRNA in cancer therapy is in sensitizing tumors to chemotherapy (88). Due to ability of miRNAs to target signaling pathways that are frequently misregulated in cancers, studies have examined the potential of miRNAs or antagomirs to sensitize resistant cells to already known and successful cancer therapies (e.g., tamoxine, gefitinib treatments, etc.). Several promising in vitro and mouse model studies have already shown efficacy of this approach guiding now the clinical development of miRNA-based therapies for sensitization to chemotherapy.

However, despite the advances made in the miRNA-mediated therapy, two major hurdles still remain: the first is to maintain target specificity, which is especially challenging and its effect needs to be evaluated on a proteome-wide scale to prevent unwanted gene alterations, due to partial complementary binding between miRNAs and protein-coding transcripts (77). The second hurdle is to achieve high therapeutic efficiency, which is linked with delivery efficiency. In addition to lipid- and polymer-based nanoparticles for systemic delivery, viral vectors may be also used; these approaches were found suitable for certain types of tumors and further investigations are needed for evaluation of these approaches in various tumor types (77).

Conclusions and future directions

The causes of differential expression of miRNA genes in tumorous tissues can be better understood by including multiple layers, such as their location in cancer-associated genomic regions, epigenetic mechanisms, and alterations in the miRNA processing machinery into a coordinately regulated network. The expanding field of miRNA and cancer research therefore requires the consideration of such an interplay that connects the regulatory mechanisms and their function into an intricate network. Future studies will further clarify complex interactions of short and long ncRNAs with protein coding genes and their involvement in shaping phenotypes and cancer development.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Calin GA, Croce CM. MicroRNA signatures in human cancers. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6(11):857–866. doi: 10.1038/nrc1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kanellopoulou C, Monticelli S. A role for microRNAs in the development of the immune system and in the pathogenesis of cancer. Semin Cancer Biol. 2008;18(2):79–88. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2008.01.002. Epub 2008 Jan 15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Esquela-Kerscher Aurora, Slack Frank J. Oncomirs [mdash] microRNAs with a role in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6(4):259–269. doi: 10.1038/nrc1840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liang Y, Ridzon D, Wong L, Chen C. Characterization of microRNA expression profiles in normal human tissues. BMC Genomics. 2007;8:166. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-8-166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sassen S, Miska EA, Caldas C. MicroRNA: implications for cancer. Virchows Arch. 2008;452(1):1–10. doi: 10.1007/s00428-007-0532-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brennecke J, Hipfner DR, Stark A, Russell RB, Cohen SM. bantam encodes a developmentally regulated microRNA that controls cell proliferation and regulates the proapoptotic gene hid in Drosophila. Cell. 2003;113(1):25–36. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00231-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee RC, Feinbaum RL, Ambros V. The C. elegans heterochronic gene lin-4 encodes small RNAs with antisense complementarity to lin-14. Cell. 1993;75(5):843–854. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90529-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Calin George Adrian, Sevignani Cinzia, Dan Dumitru Calin, Hyslop Terry, Noch Evan, Yendamuri Sai, Shimizu Masayoshi, Rattan Sashi, Bullrich Florencia, Negrini Massimo, Croce Carlo M. Human microRNA genes are frequently located at fragile sites and genomic regions involved in cancers. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101(9):2999–3004. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307323101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gaur A, Jewell DA, Liang Y, Ridzon D, Moore JH, Chen C, Ambros VR, Israel MA. Characterization of microRNA expression levels and their biological correlates in human cancer cell lines. Cancer Res. 2007;67(6):2456–2468. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lu C, Tej SS, Luo S, Haudenschild CD, Meyers BC, Green PJ. Elucidation of the small RNA component of the transcriptome. Science. 2005;309(5740):1567–1569. doi: 10.1126/science.1114112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Calin GA, Dumitru CD, Shimizu M, Bichi R, Zupo S, Noch E, Aldler H, Rattan S, Keating M, Rai K, Rassenti L, Kipps T, Negrini M, Bullrich F, Croce CM. Frequent deletions and down-regulation of micro- RNA genes miR15 and miR16 at 13q14 in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(24):15524–15529. doi: 10.1073/pnas.242606799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang B, Pan X, Cobb GP, Anderson TA. microRNAs as oncogenes and tumor suppressors. Dev Biol. 2007;302(1):1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. The hallmarks of cancer. Cell. 2000;100(1):57–70. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81683-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Negrini M, Nicoloso MS, Calin GA. MicroRNAs and cancer--new paradigms in molecular oncology. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2009;21(3):470–479. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.He L, Thomson JM, Hemann MT, Hernando-Monge E, Mu D, Goodson S, Powers S, Cordon-Cardo C, Lowe SW, Hannon GJ, Hammond SM. A microRNA polycistron as a potential human oncogene. Nature. 2005;435(7043):828–833. doi: 10.1038/nature03552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O'Donnell KA, Wentzel EA, Zeller KI, Dang CV, Mendell JT. c-Myc-regulated microRNAs modulate E2F1 expression. Nature. 2005;435(7043):839–843. doi: 10.1038/nature03677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnson SM, Grosshans H, Shingara J, Byrom M, Jarvis R, Cheng A, Labourier E, Reinert KL, Brown D, Slack FJ. RAS is regulated by the let-7 microRNA family. Cell. 2005;120(5):635–647. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lewis Benjamin P, Burge Christopher B, Bartel David P. Conserved Seed Pairing, Often Flanked by Adenosines, Indicates that Thousands of Human Genes are MicroRNA Targets. Cell. 2005;120(1):15–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krek A, Grün D, Poy MN, Wolf R, Rosenberg L, Epstein EJ, MacMenamin P, da Piedade I, Gunsalus KC, Stoffel M, Rajewsky N. Combinatorial microRNA target predictions. Nat Genet. 2005;37(5):495–500. doi: 10.1038/ng1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Volinia S, Calin GA, Liu CG, Ambs S, Cimmino A, Petrocca F, Visone R, Iorio M, Roldo C, Ferracin M, Prueitt RL, Yanaihara N, Lanza G, Scarpa A, Vecchione A, Negrini M, Harris CC, Croce CM. A microRNA expression signature of human solid tumors defines cancer gene targets. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(7):2257–2261. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510565103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hwang HW, Wentzel EA, Mendell JT. A hexanucleotide element directs microRNA nuclear import. Science. 2007;315(5808):97–100. doi: 10.1126/science.1136235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lytle JR, Yario TA, Steitz JA. Target mRNAs are repressed as efficiently by microRNA-binding sites in the 5' UTR as in the 3' UTR. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(23):9667–9672. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703820104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Place RF, Li LC, Pookot D, Noonan EJ, Dahiya R. MicroRNA-373 induces expression of genes with complementary promoter sequences. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(5):1608–1613. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707594105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tay Y, Zhang J, Thomson AM, Lim B, Rigoutsos I. MicroRNAs to Nanog, Oct4 and Sox2 coding regions modulate embryonic stem cell differentiation. Nature. 2008;455(7216):1124–1128. doi: 10.1038/nature07299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Forman JJ, Legesse-Miller A, Coller HA. A search for conserved sequences in coding regions reveals that the let-7 microRNA targets Dicer within its coding sequence. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(39):14879–14884. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803230105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vasudevan S, Tong Y, Steitz JA. Switching from repression to activation: microRNAs can up-regulate translation. Science. 2007;318(5858):1931–1934. doi: 10.1126/science.1149460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eiring AM, Harb JG, Neviani P, Garton C, Oaks JJ, Spizzo R, Liu S, Schwind S, Santhanam R, Hickey CJ, Becker H, Chandler JC, Andino R, Cortes J, Hokland P, Huettner CS, Bhatia R, Roy DC, Liebhaber SA, Caligiuri MA, Marcucci G, Garzon R, Croce CM, Calin GA, Perrotti D. miR-328 functions as an RNA decoy to modulate hnRNP E2 regulation of mRNA translation in leukemic blasts. Cell. 2010;140(5):652–665. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Calin GA, Liu CG, Ferracin M, Hyslop T, Spizzo R, Sevignani C, Fabbri M, Cimmino A, Lee EJ, Wojcik SE, Shimizu M, Tili E, Rossi S, Taccioli C, Pichiorri F, Liu X, Zupo S, Herlea V, Gramantieri L, Lanza G, Alder H, Rassenti L, Volinia S, Schmittgen TD, Kipps TJ, Negrini M, Croce CM. Ultraconserved regions encoding ncRNAs are altered in human leukemias and carcinomas. Cancer Cell. 2007;12(3):215–229. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Salmena L, Poliseno L, Tay Y, Kats L, Pandolfi PP. A ceRNA hypothesis: the Rosetta Stone of a hidden RNA language? Cell. 2011;146(3):353–358. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Calin GA, Croce CM. Chromosomal rearrangements and microRNAs: a new cancer link with clinical implications. J Clin Invest. 2007;117(8):2059–2066. doi: 10.1172/JCI32577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Calin GA, Croce CM. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia: interplay between noncoding RNAs and protein-coding genes. Blood. 2009;114(23):4761–4770. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-07-192740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Calin GA, Croce CM. MicroRNA-cancer connection: the beginning of a new tale. Cancer Res. 2006;66(15):7390–7394. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Georges M, Coppieters W, Charlier C. Polymorphic miRNA-mediated gene regulation: contribution to phenotypic variation and disease. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2007;17(3):166–176. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2007.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sun Guihua, Yan Jin, Noltner Katie, Feng Jinong, Li Haitang, Sarkis Daniel A, Sommer Steve S, Rossi John J. SNPs in human miRNA genes affect biogenesis and function. RNA. 2009;15(9):1640–1651. doi: 10.1261/rna.1560209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tian T, Shu Y, Chen J, Hu Z, Xu L, Jin G, Liang J, Liu P, Zhou X, Miao R, Ma H, Chen Y, Shen H. A functional genetic variant in microRNA-196a2 is associated with increased susceptibility of lung cancer in Chinese. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18(4):1183–1187. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Diederichs S, Haber DA. Sequence variations of microRNAs in human cancer: alterations in predicted secondary structure do not affect processing. Cancer Res. 2006;66(12):6097–6104. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shen J, Ambrosone CB, DiCioccio RA, Odunsi K, Lele SB, Zhao H. A functional polymorphism in the miR-146a gene and age of familial breast/ovarian cancer diagnosis. Carcinogenesis. 2008;29(10):1963–1966. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgn172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hu Z, Liang J, Wang Z, Tian T, Zhou X, Chen J, Miao R, Wang Y, Wang X, Shen H. Common genetic variants in pre-microRNAs were associated with increased risk of breast cancer in Chinese women. Hum Mutat. 2009;30(1):79–84. doi: 10.1002/humu.20837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zeng Y, Cullen BR. Efficient processing of primary microRNA hairpins by Drosha requires flanking nonstructured RNA sequences. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(30):27595–27603. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504714200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zorc M, Jevsinek Skok D, Godnic I, Calin GA, Horvat S, Jiang Z, Dovc P, Kunej T. Catalog of MicroRNA Seed Polymorphisms in Vertebrates. PLoS One. 2012;7(1):e30737. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chin LJ, Ratner E, Leng S, Zhai R, Nallur S, Babar I, Muller RU, Straka E, Su L, Burki EA, Crowell RE, Patel R, Kulkarni T, Homer R, Zelterman D, Kidd KK, Zhu Y, Christiani DC, Belinsky SA, Slack FJ, Weidhaas JB. A SNP in a let-7 microRNA complementary site in the KRAS 3' untranslated region increases non-small cell lung cancer risk. Cancer Res. 2008;68(20):8535–8540. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nicoloso MS, Sun H, Spizzo R, Kim H, Wickramasinghe P, Shimizu M, Wojcik SE, Ferdin J, Kunej T, Xiao L, Manoukian S, Secreto G, Ravagnani F, Wang X, Radice P, Croce CM, Davuluri RV, Calin GA. Single-nucleotide polymorphisms inside microRNA target sites influence tumor susceptibility. Cancer Res. 2010;70(7):2789–2798. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ryan BM, Robles AI, Harris CC. Genetic variation in microRNA networks: the implications for cancer research. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10(6):389–402. doi: 10.1038/nrc2867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kumar MS, Lu J, Mercer KL, Golub TR, Jacks T. Impaired microRNA processing enhances cellular transformation and tumorigenesis. Nat Genet. 2007;39(5):673–677. doi: 10.1038/ng2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Horikawa Y, Wood CG, Yang H, Zhao H, Ye Y, Gu J, Lin J, Habuchi T, Wu X. Single nucleotide polymorphisms of microRNA machinery genes modify the risk of renal cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(23):7956–7962. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yang H, Dinney CP, Ye Y, Zhu Y, Grossman HB, Wu X. Evaluation of genetic variants in microRNA-related genes and risk of bladder cancer. Cancer Res. 2008;68(7):2530–2537. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Clague J, Lippman SM, Yang H, Hildebrandt MA, Ye Y, Lee JJ, Wu X. Genetic variation in MicroRNA genes and risk of oral premalignant lesions. Mol Carcinog. 2010;49(2):183–189. doi: 10.1002/mc.20588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hiard Samuel, Charlier Carole, Coppieters Wouter, Georges Michel, Baurain Denis. Patrocles: a database of polymorphic miRNA-mediated gene regulation in vertebrates. Nucleic Acids Research. 2010;38(suppl 1):D640–D651. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ziebarth JD, Bhattacharya A, Chen A, Cui Y. PolymiRTS Database 2.0: linking polymorphisms in microRNA target sites with human diseases and complex traits. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011 doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yu XP, Lin J, Zack DJ, Mendell JT, Qian J. Analysis of regulatory network topology reveals functionally distinct classes of microRNAs. Nucleic Acids Research. 2008;36(20):6494–6503. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shalgi R, Lieber D, Oren M, Pilpel Y. Global and local architecture of the mammalian microRNA-transcription factor regulatory network. Plos Computational Biology. 2007;3(7):1291–1304. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0030131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tarasov V, Jung P, Verdoodt B, Lodygin D, Epanchintsev A, Menssen A, Meister G, Hermeking H. Differential regulation of microRNAs by p53 revealed by massively parallel Sequencing - miR-34a is a p53 target that induces apoptosis and G(1)-arrest. Cell Cycle. 2007;6(13):1586–1593. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.13.4436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Le MTN, Teh C, Shyh-Chang N, Xie HM, Zhou BY, Korzh V, Lodish HF, Lim B. MicroRNA-125b is a novel negative regulator of p53. Genes & Development. 2009;23(7):862–876. doi: 10.1101/gad.1767609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chen CY, Chen ST, Fuh CS, Juan HF, Huang HC. Coregulation of transcription factors and microRNAs in human transcriptional regulatory network. BMC Bioinformatics. 2011;12(Suppl 1):S41. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-S1-S41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Enright AJ, John B, Gaul U, Tuschl T, Sander C, Marks DS. MicroRNA targets in Drosophila. Genome Biol. 2003;5(1):R1. doi: 10.1186/gb-2003-5-1-r1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cui Q, Yu Z, Pan Y, Purisima EO, Wang E. MicroRNAs preferentially target the genes with high transcriptional regulation complexity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;352(3):733–738. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.11.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fabbri M, Bottoni A, Shimizu M, Spizzo R, Nicoloso MS, Rossi S, Barbarotto E, Cimmino A, Adair B, Wojcik SE, Valeri N, Calore F, Sampath D, Fanini F, Vannini I, Musuraca G, Dell'Aquila M, Alder H, Davuluri RV, Rassenti LZ, Negrini M, Nakamura T, Amadori D, Kay NE, Rai KR, Keating MJ, Kipps TJ, Calin GA, Croce CM. Association of a MicroRNA/TP53 Feedback Circuitry With Pathogenesis and Outcome of B-Cell Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. Jama-Journal of the American Medical Association. 2011;305(1):59–67. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang J, Lu M, Qiu C, Cui Q. TransmiR: a transcription factor-microRNA regulation database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:D119–D122. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp803. (Database issue) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schmeier S, Schaefer U, MacPherson CR, Bajic VB. dPORE-miRNA: Polymorphic Regulation of MicroRNA Genes. Plos One. 2011;6(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fabbri M, Garzon R, Cimmino A, Liu Z, Zanesi N, Callegari E, Liu S, Alder H, Costinean S, Fernandez-Cymering C, Volinia S, Guler G, Morrison CD, Chan KK, Marcucci G, Calin GA, Huebner K, Croce CM. MicroRNA-29 family reverts aberrant methylation in lung cancer by targeting DNA methyltransferases 3A and 3B. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(40):15805–15810. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707628104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Noonan EJ, Place RF, Pookot D, Basak S, Whitson JM, Hirata H, Giardina C, Dahiya R. miR-449a targets HDAC-1 and induces growth arrest in prostate cancer. Oncogene. 2009;28(14):1714–1724. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Friedman JM, Liang G, Liu CC, Wolff EM, Tsai YC, Ye W, Zhou X, Jones PA. The putative tumor suppressor microRNA-101 modulates the cancer epigenome by repressing the polycomb group protein EZH2. Cancer Res. 2009;69(6):2623–2629. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Garzon R, Liu SJ, Fabbri M, Liu ZF, Heaphy CEA, Callegari E, Schwind S, Pang JX, Yu JH, Muthusamy N, Havelange V, Volinia S, Blum W, Rush LJ, Perrotti D, Andreeff M, Bloomfield CD, Byrd JC, Chan K, Wu LC, Croce CM, Marcucci G. MicroRNA-29b induces global DNA hypomethylation and tumor suppressor gene reexpression in acute myeloid leukemia by targeting directly DNMT3A and 3B and indirectly DNMT1. Blood. 2009;113(25):6411–6418. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-07-170589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Weber Barbara, Stresemann Carlo, Brueckner Bodo, Lyko Frank. Methylation of Human MicroRNA Genes in Normal and Neoplastic Cells. Cell Cycle. 2007;6(9):1001–1005. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.9.4209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Saito Yoshimasa, Liang Gangning, Egger Gerda, Friedman Jeffrey M, Chuang Jody C, Coetzee Gerhard A, Jones Peter A. Specific activation of microRNA-127 with downregulation of the proto-oncogene BCL6 by chromatin-modifying drugs in human cancer cells. Cancer Cell. 2006;9(6):435–443. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lujambio Amaia, Ropero Santiago, Ballestar Esteban, Fraga Mario F, Cerrato Celia, Setién Fernando, Casado Sara, Suarez-Gauthier Ana, Sanchez-Cespedes Montserrat, Gitt Anna, Spiteri Inmaculada, Das Partha P, Caldas Carlos, Miska Eric, Esteller Manel. Genetic Unmasking of an Epigenetically Silenced microRNA in Human Cancer Cells. Cancer Research. 2007;67(4):1424–1429. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Brueckner Bodo, Stresemann Carlo, Kuner Ruprecht, Mund Cora, Musch Tanja, Meister Michael, Sültmann Holger, Lyko Frank. The Human let-7a-3 Locus Contains an Epigenetically Regulated MicroRNA Gene with Oncogenic Function. Cancer Research. 2007;67(4):1419–1423. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kunej T, Godnic I, Ferdin J, Horvat S, Dovc P, Calin GA. Epigenetic regulation of microRNAs in cancer: an integrated review of literature. Mutat Res. 2011;717(1–2):77–84. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lu J, Getz G, Miska EA, Alvarez-Saavedra E, Lamb J, Peck D, Sweet-Cordero A, Huang BJC, Babak T, Corson TW, Chua G, Khan S, Gallie BL, Hughes TR, Blencowe BJ, Frey BJ, Morris QD. Using expression profiling data to identify human microRNA targets. Nat Methods. 2007;4(12):1045–1049. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Huang JC, Babak T, Corson TW, Chua G, Khan S, Gallie BL, Hughes TR, Blencowe BJ, Frey BJ, Morris QD. Using expression profiling data to identify human microRNA targets. Nat Methods. 2007;4(12):1045–1049. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ferdin J, Kunej T, Calin GA. Non-coding RNAs: Identification of Cancer-Associated microRNAs by Gene Profiling. Technology in Cancer Research & Treatment. 2010:123–138. doi: 10.1177/153303461000900202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Esteller M. Epigenetics in cancer. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(11):1148–1159. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra072067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Melo SA, Esteller M. A precursor microRNA in a cancer cell nucleus: get me out of here! Cell Cycle. 2011;10(6):922–925. doi: 10.4161/cc.10.6.15119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Cortez MA, Bueso-Ramos C, Ferdin J, Lopez-Berestein G, Sood AK, Calin GA. MicroRNAs in body fluids--the mix of hormones and biomarkers. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2011;8(8):467–477. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2011.76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Barbarotto E, Schmittgen TD, Calin GA. MicroRNAs and cancer: profile, profile, profile. Int J Cancer. 2008;122(5):969–977. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Calin GA, Ferracin M, Cimmino A, Di Leva G, Shimizu M, Wojcik SE, Iorio MV, Visone R, Sever NI, Fabbri M, Iuliano R, Palumbo T, Pichiorri F, Roldo C, Garzon R, Sevignani C, Rassenti L, Alder H, Volinia S, Liu CG, Kipps TJ, Negrini M, Croce CM. A MicroRNA signature associated with prognosis and progression in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(17):1793–1801. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Li C, Feng Y, Coukos G, Zhang L. Therapeutic microRNA strategies in human cancer. AAPS J. 2009;11(4):747–757. doi: 10.1208/s12248-009-9145-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Weiler J, Hunziker J, Hall J. Anti-miRNA oligonucleotides (AMOs): ammunition to target miRNAs implicated in human disease? Gene Ther. 2006;13(6):496–502. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ebert MS, Neilson JR, Sharp PA. MicroRNA sponges: competitive inhibitors of small RNAs in mammalian cells. Nat Methods. 2007;4(9):721–726. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Xiao J, Yang B, Lin H, Lu Y, Luo X, Wang Z. Novel approaches for gene-specific interference via manipulating actions of microRNAs: examination on the pacemaker channel genes HCN2 and HCN4. J Cell Physiol. 2007;212(2):285–292. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Gumireddy K, Young DD, Xiong X, Hogenesch JB, Huang Q, Deiters A. Small-molecule inhibitors of microrna miR-21 function. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2008;47(39):7482–7484. doi: 10.1002/anie.200801555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kumar MS, Erkeland SJ, Pester RE, Chen CY, Ebert MS, Sharp PA, Jacks T. Suppression of non-small cell lung tumor development by the let-7 microRNA family. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(10):3903–3908. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712321105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Johnson CD, Esquela-Kerscher A, Stefani G, Byrom M, Kelnar K, Ovcharenko D, Wilson M, Wang X, Shelton J, Shingara J, Chin L, Brown D, Slack FJ. The let-7 microRNA represses cell proliferation pathways in human cells. Cancer Res. 2007;67(16):7713–7722. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Esquela-Kerscher A, Trang P, Wiggins JF, Patrawala L, Cheng A, Ford L, Weidhaas JB, Brown D, Bader AG, Slack FJ. The let-7 microRNA reduces tumor growth in mouse models of lung cancer. Cell Cycle. 2008;7(6):759–764. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.6.5834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Cimmino A, Calin GA, Fabbri M, Iorio MV, Ferracin M, Shimizu M, Wojcik SE, Aqeilan RI, Zupo S, Dono M, Rassenti L, Alder H, Volinia S, Liu CG, Kipps TJ, Negrini M, Croce CM. miR-15 and miR-16 induce apoptosis by targeting BCL2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(39):13944–13949. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506654102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Bonci D, Coppola V, Musumeci M, Addario A, Giuffrida R, Memeo L, D'Urso L, Pagliuca A, Biffoni M, Labbaye C, Bartucci M, Muto G, Peschle C, De Maria R. The miR-15a-miR-16-1 cluster controls prostate cancer by targeting multiple oncogenic activities. Nat Med. 2008;14(11):1271–1277. doi: 10.1038/nm.1880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kota J, Chivukula RR, O'Donnell KA, Wentzel EA, Montgomery CL, Hwang HW, Chang TC, Vivekanandan P, Torbenson M, Clark KR, Mendell JR, Mendell JT. Therapeutic microRNA delivery suppresses tumorigenesis in a murine liver cancer model. Cell. 2009;137(6):1005–1017. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kasinski AL, Slack FJ. Epigenetics and genetics. MicroRNAs en route to the clinic: progress in validating and targeting microRNAs for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11(12):849–864. doi: 10.1038/nrc3166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]