Abstract

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is an autoimmune disease characterized by chronic inflammation of the joints. The prolonged use of anti-inflammatory drugs and other newer drugs is associated with severe adverse reactions. Therefore, there is a need for newer anti-arthritic agents. Celastrol, a bioactive component of the Chinese herb Celastrus, possesses anti-arthritic activity as tested in the adjuvant arthritis (AA) model of rheumatoid arthritis (RA). However, the mechanism of action of Celastrol has not been fully defined. We reasoned that microarray analysis of the lymphoid cells of Celastrol-treated arthritic animals might provide vital clues in this regard. We isolated total RNA of the draining lymph node cells (LNC) of Celastrol-treated (Tc) and vehicle-treated (Tp) arthritic Lewis rats, restimulated them in vitro with the disease-related antigen, mycobacterial heat-shock protein 65 (Bhsp65), and tested it using microarray gene chips. Also tested were control arthritic rats just before any treatment (T0). Seventy six genes involved in various biological functions were differentially regulated by Bhsp65 in LNC of Tp group, and 19 genes among them were shared by the Tc group. Furthermore, a group of 14 genes was unique to Tc, indicating that Celastrol modulated not only arthritis-related genes but also those involved in other defined pathways. When Tc and Tp were compared, many of the Bhsp65-induced genes were related to the immune cells, cellular proliferation and inflammatory responses. Our results revealed 10 differentially expressed genes and 14 pathways that constituted the “Celastrol Signature”. Our results would help identify novel targets for therapeutic purposes.

Keywords: Arthritis, Celastrus, Celastrol, Inflammation, Gene expression, Microarray

1. Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic inflammatory disorder that is characterized by mononuclear cell infiltration into the joint, hyperplasia of the synovial membrane, and cartilage and bone destruction [1–3]. The pathogenesis of RA is complicated because several cell types such as immune cells, fibroblasts, osteoclasts, and chondrocytes are involved in mediating the immune pathology in the joints [4–7]. It is believed that mononuclear cell infiltration into the joint initiates local inflammation, and that the functional characteristics of these infiltrating cells determine the subsequent events and the outcome [8]. Adjuvant-induced arthritis (AA) in rats shares many features of RA in humans, and it has been used as an experiment model for research in arthritis for decades [9, 10]. The T lymphocytes from rats with AA respond to Bhsp65, which is considered to be one of the arthritis-related antigens [11–13]. The current study using the AA model is on immune cells from the draining lymph nodes, which are the primary resource for the joint-infiltrating cells in arthritic rats.

In recent years, increasing number of plant-derived herbal medicinal products are being considered for the treatment of inflammatory diseases such as RA [14–17]. Plant products are generally less toxic and better tolerated than many of the conventional drugs [18]. However, the mechanisms of action of many potentially anti-arthritic plant products are not fully defined. Celastrol is one of the bioactive components of the Chinese herb Celastrus, which belongs to the family Celastraceae. Celastrol possesses anti-oxidant and anti-inflammatory activities [19–22]. We [23] and others [24] have previously reported the anti-arthritic activity of Celastrol in the AA model, and this effect is mediated through its effect on the key pro-inflammatory cytokines, the disease-related antibodies, and the activity of MMPs. However, these processes represent only a small fraction of the pathways that might be altered by Celastrol. In this study, using the same treatment regimen with celastrol as in our previous study [23], we profiled the Bhsp65-induced gene expression and its modulation by Celastrol-treatment using transcriptome-wide microarray and pathway analysis technologies to comprehensively investigate the mechanisms involved in the anti-inflammatory and anti-arthritic activity of Celastrol.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Antigens, Chemicals and Reagents

Heat-killed Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Ra (Mtb) was purchased from Difco (Detroit, Michigan). Mycobacterial heat-shock protein 65 (Bhsp65) was prepared from pET23b-GroEL2 vector-transformed (Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO) BL21(DE3)pLysS cells (Novagen, Madison, WI) as described [25]. Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, USA). Celastrol, ((9β,13α,14β,20α)-3-hydroxy-9,13-dimethyl-2-oxo-24,25,26-trinoroleana-1(10),3,5,7-tetraen-29-oic acid), Mr = 450.6, purity>95%) isolated from Celastrus scandens was obtained from Calbiochem. Celastrol stock solution (20 mg in 0.6 ml of DMSO) was kept at −20°C until used. Celastrol working solution for arthritis treatment was prepared by dilution of 6 µl stock in 500 µl of PBS). DMSO (1.2%) in PBS served as the vehicle control as described in our previous study [23].

2.2 Induction of adjuvant arthritis (AA) and the treatment of arthritic rats with Celastrol

The experiments were performed following approval by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Maryland School of Medicine (UMB). AA was induced in a cohort (n= 9) of male Lewis rats (LEW/SsNHsd (RT.11)), 5–6 weeks old (Harlan Sprague Dawley, Indianapolis, IN), by subcutaneous injection of Mtb (2 mg/ rat) emulsified in mineral oil (Sigma-Aldrich). Thereafter, these rats were randomly assigned to 3 groups (3 rats/group). At the onset of AA (about 12 days following administration of Mtb), one group of rats was sacrificed (T0) and their draining lymph nodes (LN) (superficial inguinal, para-aortic, and popliteal) harvested for testing. The remaining two groups were given an intra-peritoneal (i.p.) injection of 500 µl of either PBS-DMSO (vehicle control group) (Tp) or Celastrol in DMSO (Tc) (experimental group) for a total of 5 days followed by harvesting of their draining lymph nodes. The lymph node cells (LNC) were then tested for gene expression profiling as described below. The dose of Celastrol used, the number of injections given to rats, and the timing of injections during the course of arthritis were based on the optimal protocol of Celastrol-induced suppression of arthritis in Lewis rats reported in our previous study [23].

2.3 Lymph node cell (LNC) culture and RNA extraction

A single-cell suspension of lymph node cells (LNC) prepared from the draining lymph nodes was cultured in HL-1 serum-free medium with or without Bhsp65 (5µg/ml) for 24 h. Then total RNA was extracted from LNC using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, CA) following the manufacturer's protocol and it was further purified using an RNeasy Mini Kit (QiagenValencia, CA). The concentration of the total RNA was determined with a NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer at 230, 260 and 280 nm (NanoDrop Technologies/Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, DE), and the RNA quality was assessed by automated capillary gel electrophoresis on an Agilent bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent, CA).

2.4 Oligonucleotide microarray hybridization and image acquisition

The RNA integrity number (RIN) of the RNA isolated from LNC (Bhsp65-restimulated or unstimulated) ranged from 8.1 to 9.1. Total RNA (50 ng) was used as the input for the amplification and generation of biotin-labeled fragment cRNA. Purified cRNA was then hybridized onto the bead-based array, RatRef-12 Expression BeadChip, to perform the whole genome expression profiling according to Illumina’s Direct Hybridization Assay protocol. This microarray platform contains >22,000 probes based on the NCBI RefSeq database. Hybridization, image acquisition, and collection of raw data were performed as per manufacturer’s instructions.

2.5 Gene expression profile analysis

Genome Studio version 1.6.0 was used to obtain raw Illumina expression data, which was further analyzed by Gene Spring GX. The differentially-expressed genes (DEG) were determined by unpaired t test corrected with Benjamin-Hochberg, p value <0.05, and fold change >2.0 as cut off. The experimental plan and data analysis of microarray in this study are in accordance with Minimum Information about a Microarray Experiment (MIAME) guidelines [26]. Gene Ontology (GO) analysis was conducted for DEG using the UniprotKB analytic platform.

2.6 Functional and pathways analysis by Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA)

The data was further analyzed using IPA to define the molecular processes, molecular functions and genetic networks involved in AA, as well as to examine the protective role of Celastrol against arthritis. This web-based entry tool enables the identification of the biological mechanisms, pathways and functions most relevant to the experimental datasets or genes of interest [27–29]. The genes with significant expression were identified by Gene Spring GX analysis using unpaired t test corrected with Benjamin-Hochberg, p value <0.05, and fold change >1.5 as cut off. The dataset of such genes containing information about fold change and gene symbol were uploaded onto the IPA System (http://www.ingenuity.com). For functional and canonical pathways analysis, Fischer’s exact test was used to calculate the p-value. For network analysis, the association of the network to the datasets was evaluated by scores. A score of 10 or higher was used to select highly significant biological networks. The above analysis was performed individually in “Core IPA” (the ingenuity pathways knowledge base (IPKB)). The corresponding dataset from either Celastrol-treated group or PBS-treated group was then further analyzed using “IPA Comparison”.

2.7 Quantitative real-time PCR

The expression of a selected number of differentially expressed genes (up/down-regulated) identified in microarray analysis was validated by quantitative real-time PCR (q-PCR) using the same RNA that was used for microarray analysis. Specific primers for the selected genes were designed according to the NCBI sequence database using the software Primer Expression 2.0. Column-purified total RNA (1 µg) was used for reverse transcription with iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad), and real-time PCR were performed with cDNA (1:10 dilution) as the template using specific primers (Sigma) in SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (AB Applied Biosystems, Warrington UK) on a LightCycler Instrument (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN) following the manufacturer's instructions. The relative expression level of the target mRNA in each sample was normalized to the mean HPRT levels. The results were presented as “fold change” compared to the respective baseline (LNCs cultured in medium alone) using the 2-ΔΔ Ct method [30]. Three replicates were tested for each sample. Differences between the test and control samples were assessed using student t test for nonparametric data.

3. Results

3.1 Comparative gene expression profiles of Bhsp65-restimulated LNC of arthritic rats before and after treatment with Celastrol/PBS

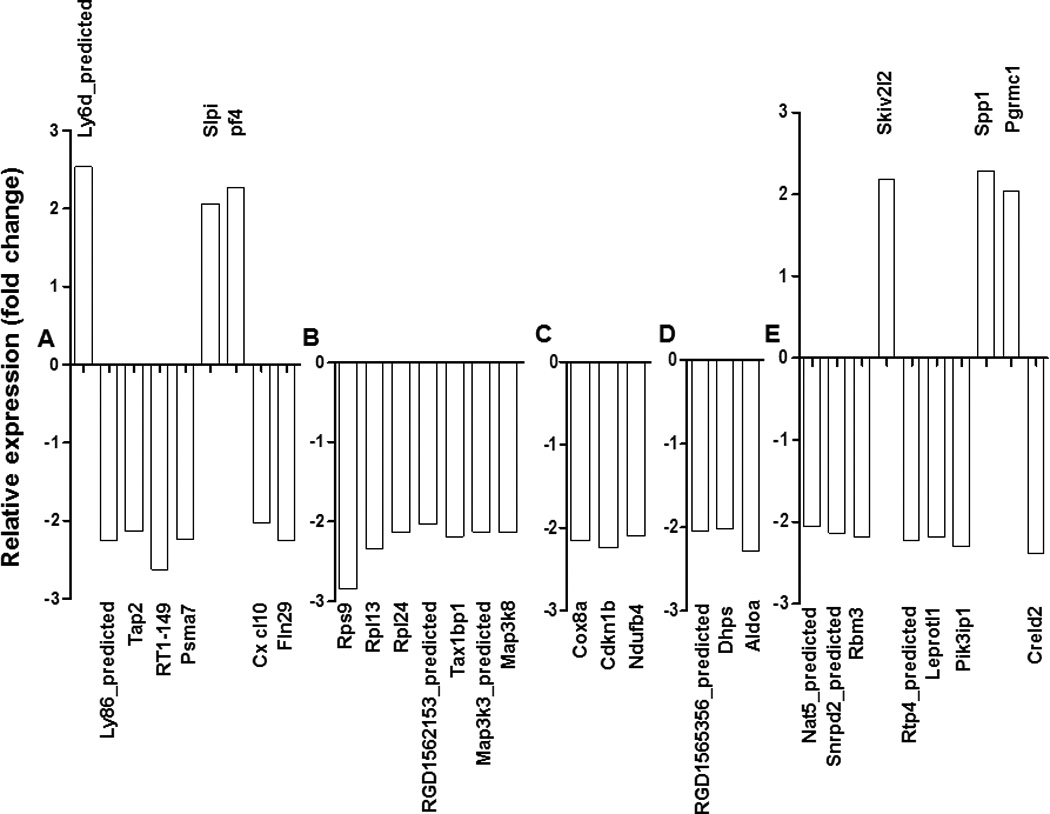

In order to compare the profiles of gene expression before and after treatment, as well as to identify changes in the expression of specific genes in response to Celastrol treatment, one group of rats was sacrificed as soon as the Mtb-immunized rats developed arthritis (T0), whereas the other groups were sacrificed after 5 days of treatment with either Celastrol (Tc) or PBS (Tp). The Bhsp65-induced gene expression of the draining LNC of the Tc/Tp group each was compared to that of T0. The results are shown in Figure 1 and Table 1.

Figure 1. The expression level of Bhps65-induced DEG identified in LNC before and after treatment with Celastrol and their categorization according to GO analysis.

A total of 32 function-defined DEG involved in immune response (A), cellular activation and proliferation (B), oxygen metabolism (C), lipid metabolism or other metabolic processes (D), and other functions (E) are shown.

Table 1.

Comparison of Bhps65-induced gene expression in LNC of rats before and after treatment with Celastrol.

| Gene function | Tc | vs | T0 |

|---|---|---|---|

| UR | DR | ||

| Immune response related | 3 | 6 | |

| Cell proliferation and apoptosis | 0 | 7 | |

| Binding activity | 1 | 3 | |

| Metabolism | 0 | 6 | |

| Not-defined | 6 | 24 | |

| Others | 3 | 4 | |

| Sub-total | 12 | 50 | |

| Total | 62 | ||

UR, upregulated; DR, downregulated; Tc, Celastrol-treatment group; Tp, PBS-treatment group T0, before treatment group. The DEGs in response to Bhsp65 restimulation of LNC were compared. The DEGs were defined using the same cut off (p< 0.05 corrected with Benjamin-Hochberg, fold change > 2.0) as that described in ‘Methods’ section. The functional categories of these DEGs were based on the main biological processes by ‘GO’ analysis. A comparison of the gene expression profile of Tp versus T0 revealed no significant change.

A comparison of the hybridization signals of mRNA from Bhsp65-restimulated LNC of Tp versus T0 group showed no significant difference, whereas that between Tc and T0 group revealed that the expression of 62 genes was significantly changed. Of these 62 genes, the expression of 12 genes was upregulated, while that of 50 genes was downregulated. Furthermore, among the 62 genes, only 32 were function-defined (6 upregulated, 26 downregulated). These genes can be categorized into 5 clusters according to their functions (Figure 1 A–E). Cluster A (Figure 1A) represents genes related to immune response (e.g., leukocyte-specific markers, components and mediators of antigen processing and presentation, chemokines, and signal transduction-related molecules). Cluster B (Figure 1B) mainly included genes involved in cellular activation and proliferation. Cluster C (Figure 1C) represents genes involved in oxygen metabolism, whereas Cluster D (Figure 1D) involves genes related to lipid metabolism or other metabolic pathways. The genes involved in extracellular matrix (ECM) remodeling, bone remodeling, receptor activity, binding activity, and other activities are given under cluster E (Figure 1E). Thus, Celastrol-treatment mainly downregulated the expressions of genes, especially the genes associated with cellular activation and proliferation, antigen processing presentation and processing, oxygen metabolism and cell-to-cell interactions.

3.2 Bhsp65-induced gene expression profiles of LNC of Celastrol-treated versus control rats

To determine the effects of Celastrol on antigen-induced changes in gene expression, we compared the profiles of gene expression in Bhsp65-restimulated LNC of Celastrol-treated (Tc) and PBS-treated (Tp) rats using Gene Spring. Out of the genes surveyed (22523 genes), a total of 76 DEG (p <0.05 and above 2 fold change) were identified in PBS-treated group, 45 of which were upregulated and 31 were downregulated. In comparison, 33 genes were differentially expressed in Celastrol-treated group, 19 of which showed enhanced expression, whereas 14 showed reduced expression (Figure 2A). The above-mentioned DEG were related to molecules involved in immune response (e.g., cytokines, chemokines/receptors, costimulatory molecules, and transcription factors), cell proliferation, cell adhesion, cell migration, ion transport, binding activity, oxidation-reduction processes, lipid metabolism, etc. (Figure 2B). The genes whose expression is altered significantly following Bhsp65 restimulation of LNC in Tc vs. Tp group are listed in Table 2 and 3. A comparison of these DEG revealed that 19 genes were common in both datasets. Most of these genes in Tc showed a similar pattern of expression as that of the genes in Tp, suggesting that Celastrol did not exert a significant effect on the expression of this set of genes (except for Cxcl10, Lpl, and Spp1).

Figure 2. Comparison of Bhsp65-induced gene expression profiles of PBS-treated and Celastrol-treated arthritic rats.

(A) heatmap of Bhsp65-induced DEGs in LNC of PBS-treated (left) and Celastrol-treated (right) rats with AA. Color bars represent the expression level of DEGs. Venn Diagrams show the numbers of DEGs individually in PBS- or Celastrol-treated group as well as the overlapping DEG in these two groups. ↑, upregulation of gene expression compared to the corresponding baseline (gene expression of LNC cultured in medium); ↓,downregulation of gene expression compared to the baseline. (B) The main functional categories of 64 (PBS-treated)/28 (Celastrol-treated) functionally well-defined DEG. Dark color shows downregulated genes, whereas light color represents the upregulated genes in each category. (The group of “non-defined genes” shown in Table 1 is not included in Figure 2B)

Table 2.

Comparison of Bhps65-induced gene expression in Celastrol-treated and vehicle (PBS)-treated rats.

| Gene function | Tc | Tp | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (%) | UR | DR | Total (%) | UR | DR | |

| Immune response related | 20 (60.6) | 15 | 5 | 34 (44.7) | 25 | 9 |

| Cell proliferation and apoptosis | 1 (3.0) | 1 | 0 | 9 (11.8) | 5 | 4 |

| Binding activity | 1 (3.0) | 0 | 1 | 8 (10.5) | 4 | 4 |

| Metabolism | 6 (18.2) | 3 | 3 | 3 (3.9) | 0 | 3 |

| Not-defined | 5 (15.2) | 0 | 5 | 12 (15.9) | 5 | 7 |

| Others | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 (13.2) | 6 | 4 |

| Total | 33 (100) | 19 | 14 | 76 (100) | 45 | 31 |

UR, upregulated; DR, downregulated. Tc, Celastrol treatment; Tp, PBS treatment. The DEGs in response to Bhsp65 restimulation of LNC were compared. The gene expression of LNC cultured with Bhsp65 was compared with that of LNC in medium for each group using the cut off (p<0.05 corrected with Benjamin-Hochberg, fold change >2.0) described in Methods section. The functional categories of these DEGs were based on the main biological processes involving these genes as assessed by “GO” analysis.

Table 3.

The top DEG induced by Bhsp65 in LNC of Celastrol-/PBS-treated rats.

| Gene symbol | Gene name | Fold change (compared to baseline) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| PBS-treated | Celastrol- treated |

||

| SOCS1 | Suppressor of cytokine signaling 1 | +4.1988 | +2.7826 |

| IFNγ | Interferon gamma | +39.9306 | +4.8015 |

| IRF1 | Interferon regulatory factor 1 | ― | +2.8919 |

| IRF7 | Interferon regulatory factor 7 | +4.1538 | +2.8919 |

| IL9 | Interleukin-9 | +7.2527 | +4.5150 |

| Rgd1561292(IL22) | Interleukin-22 | +11.0297 | ― |

| CXCL10 | C-X-C motif chemokine 10 | +29.0640 | +12.5346 |

| UBD | Ubiquitin D | +10.4740 | +8.0850 |

| LPL | Lipoprotein lipase | +16.2364 | +11.9873 |

| GZMA | Granzyme A | +12.2139 | ― |

| GZMB | Granzyme B | +15.2732 | +4.0570 |

| LIF47 | Leukemia inhibitory factor 47 | ― | +7.0470 |

| C2 | Component C2 | ― | +5.4422 |

| GBP2 | Guanylate binding protein 2, interferon-inducible | +3.5005 | +3.2406 |

| IGTP | Interferon gamma induced GTPase | ― | +3.0022 |

| TAP1 | Antigen peptide transporter 1 | ― | +2.8854 |

| SPP1 | Osteopontin | −5.6245 | −13.2706 |

| CD36 | Cluster of Differentiation 36 | −4.3103 | −5.7006 |

| DRD4 | Dopamine D4 receptor | +4.7676 | ― |

The DEGs were identified with p value <0.05 and fold change above 2. ”―”, not significant when compared to the corresponding baseline expression. “+”, upregulation, “−”, downregulation. The genes in bold represent the “Celastrol Signature.”

To validate the gene expression inferred from the microarray data, the expression levels of a set of representative genes were determined by real-time PCR using the same RNA samples. The results obtained by PCR testing matched those of the gene expression profile in microarray (Figure 3, r2=0.7069, p<0.0001), thus validating the microarray-based expression observed in our study.

Figure 3. Correlation of gene expression obtained from microarray and from qPCR.

X axis, gene expression determined by RatRef-12Expression BeadChip (Illumina) hybridization; Y axis, gene expression determined by quantitative PCR. Data is represented as -fold over medium after normalization. (r2=0.7069, p <0.0001)

3.3 Functional analysis of DEG in Tp and Tc group

As shown above, Celastrol regulated many genes and pathways involved in different processes. To further examine the biological functions that might be influenced by these genes, the biofunction of the Celastrol-regulated genes was investigated by “Core IPA” in the context of biological processes, pathways and gene networks affected.

Two sets (PBS- and Celastrol-treated group) of genes based on p-value <0.05 and fold change above 1.5 were analyzed. Then, comparative analysis was performed to analyze changes in the biological states between these two datasets, and to determine the Celastrol-induced changes in LNC following Bhsp65 restimulation. The biofunctions that were most significantly regulated by Celastrol are shown in Figure 4. Many of these genes perturbed by Celastrol are related to inflammatory responses and immune functions (Suppl. Table 1).

Figure 4. Comparative Bio-function analysis of Tc and Tp groups.

Data sets were analyzed by the IPA software (Ingenuity® Systems) is expressed as a p-value (< 0.05), which was calculated using the right-tailed Fisher’s Exact Test. Figure shows the top 10 (most significant) bio-functional groups. Threshold is set at p = 0.05.

3.4 Canonical pathways analysis and comparison of Tc and Tp datasets with IPA

Global Canonical Pathway analysis was performed by comparing the two datasets, Tc and Tp. Results from IPA analysis showed that in a total 238 of pathways influenced, 69 pathways were significantly enriched among the genes induced by Bhsp65 in PBS-treated group (p < 0.05), whereas 72 pathways were enriched in Celastrol-treated group. Among these significant pathways, 30 were identified in both groups. Most of the affected shared pathways showed differences in magnitude as well as the identity of the genes involved in the pathways (Suppl. Table 2). From the datasets, 39 pathways were unique to the PBS-treated group compared to 42 that were unique to the Celastrol-treated group. Figure 5 shows the top 10 canonical pathways that were most significantly altered in each group and the comparison with the other group. We further examined 5 canonical pathways that are directly related to inflammatory and immune responses. The results are shown in Suppl. Figure 1–5 and Suppl. Table 2.

Figure 5. Comparative Canonical Pathway analysis.

Data sets were analyzed and compared by ‘IPA’. The significance is expressed as a p-value (< 0.05), which was calculated using the right-tailed Fisher’s Exact Test. Figure shows the top 10 (most significant) pathways in each group and their counterparts in the other group. P = 0.05 served as threshold.

3.5 Major network pathway analysis

For the PBS-treated group, IPA analysis revealed those DEGs that were highly relevant to 12 networks (Table 4). In comparison, DEG related to 9 networks in Celastrol-treated group were identified (Table 4). We overlapped the top 5 networks of each group’s datasets for comparative analysis to investigate molecular interactions between these molecules (Suppl. Figure 6 and 7). In PBS-treated group, 11 molecules identified by the IPA program (Suppl. Figure 6) showed connectivity to the majority of molecules within the mergence, out of which 8 showed statistical significance in the microarray data. On the other hand, in Celastrol-treated group, 9 molecules showed connectivity with other genes as analyzed by IPA (Suppl. Figure 7), but only 5 of them showed significance in the microarray data. Overall, among the network pathways, 80% were related to immunological functions.

Table 4.

Highly relevant networks in Bhsp65 restimulated LNC in PBS-treated versus Celastrol–treated rats with AA.

| Networks affected by PBSa-/Celastrolb-treatment | Number of genes involved |

Score |

|---|---|---|

| aCell Death, Inflammatory Response, DNA Replication, Recombination, and Repair | 17 | 33 |

| aInflammatory Response, Infectious Disease, Cell-To-Cell Signaling and Interaction | 16 | 29 |

| aLipid Metabolism, Molecular Transport, Small Molecule Biochemistry | 16 | 27 |

| aInflammatory Response, Cell-To-Cell Signaling and Interaction, Hematological System Development and Function | 14 | 26 |

| aCancer, Cellular Function and Maintenance, Cell Morphology | 10 | 23 |

| bCell-To-Cell Signaling and Interaction, Hematological System Development and Function, Immune Cell Trafficking | 16 | 38 |

| bInflammatory Response, Cell Death, Cell-To-Cell Signaling and Interaction | 9 | 17 |

| bGene Expression, Cardiovascular System Development and Function, Cell Death | 9 | 17 |

| bDevelopmental Disorder, Endocrine System Disorders, Genetic Disorder | 9 | 17 |

| bCell-To-Cell Signaling and Interaction, Cellular Movement, Hematological System Development and Function | 6 | 10 |

The top 5 relevant networks in Bhsp65 restimulated LNC in PBS-/Celastrol-treated rats with AA were ranked by scores in each group.

“a”, significant networks in PBS-treated group,

“b”, significant networks in Celastrol-treated group.

4. Discussion

Celastrol is a bioactive component of Celastrus, which has been utilized as a medicinal herb in traditional Chinese medicine for the treatment of arthritis for many decades [31]. Although several studies have shown that Celastrol has anti-oxidant and anti-inflammatory activity [19–21], the effect of Celastrol on the processes involved in arthritis are not fully defined. Combining the benefit of microarray, bioinformatics, and IPA database in this study, we assessed the alteration of gene expression in the draining LNC of arthritic rats treated with Celastrol and compared it with that of control rats. Also examined was Celastrol-induced interference in network interactions among cellular and molecular components and processes. The data was analyzed using four different formats, namely heat map, biofunction, pathway analysis and networks. Our results have provided insights into the pathogenesis of arthritis as well as the potential mechanisms by which Celastrol attenuated AA.

Among a total of 22,000 genes, in the PBS-treated control group, Bhsp65 restimulation affected 76 DEG. In the Celastrol-treated rats, Bhsp65 induced only 33 DEG. These results suggested that Celastrol modulated gene expression in LNC in response to Bhsp65 restimulation. Further analysis showed that Celastrol mainly regulated the genes associated with inflammatory and immune response, cell proliferation and lipid and vitamin metabolism (Table 2 and Figure 2). Biofunction analysis indicated that the most significant effect of Celastrol included the inhibition of the inflammatory response, the decrease in antigen processing and presentation, and the repression of cell-mediated and antibody-mediated immune responses. The above changes could in part explain how Celastrol mediated its anti-arthritic activity. Further, we analyzed the signaling pathways. With Celastrol treatment in vivo, the signaling pathways that were markedly inhibited include TWEAK signaling, Nur 77 signaling in T lymphocytes, IL-12 signaling and production in macrophages, IL-17 signaling, TNFR1 and TNFR2 signaling, NF-κB signaling, lymphotoxin β receptor signaling, and CD27 signaling in T lymphocytes. Also affected were signaling event relating to B cell development, aminoacyl-tRNA biosynthesis, and biosynthesis of steroids (Suppl. Table 2).

Besides influencing the inflammation- and immune response-associated signaling pathways, Celastrol blocks additional pathways involved in metabolism. Steroids mediate oxidative stress. The products of oxidative reaction such as free radicals and other reactive oxygen species (ROS) cause oxidative damage, and this in turn can cause pathological damage to a wide variety of tissues. Increased oxidative stress has been implicated in the pathogenesis of inflammatory, autoimmune and degenerative diseases. Accordingly, Celastrol exhibits anti-oxidant properties and offers beneficial effect in oxidative-stress-induced injury [19, 22, 32, 33].

Many other signaling pathways were influenced by Celastrol treatment (Table 3). Most of these signaling events are associated with pro-inflammation responses. IFN-γ and its induced product CXCL10 (IP10) were the predominant targets of Celastrol action. RA is a Th1-mediated disease and [34]. Celastrol mainly affected Th1 cell differentiation. Besides immune cells, osteoblasts, osteoclasts and chondrocytes also orchestrate the pathogenic events in autoimmune arthritis [4–7].

In PBS-treated control rats with AA, Bhsp65-induced downregulation of Osteopontin (OPN, SPP1), which play important role in bone remodeling; an increase in baculoviral IAP repeat-containing protein 3 expression (CIAP, BIRC3) would inhibit osteoclast apoptosis [35]; the upregulation of IL-1, IL-18 and IFN-γ might promote osteoclast differentiation [36–38]; and an increase in IL-1 and IL-18 could induce chondrocyte death and degradation of chondrocyte [39, 40].

Celastrol down-regulated inflammation and immune response-related signaling. This should not be interpreted to mean that Celastrol is a broad immunosuppressant. In fact, Celastrol relatively or absolutely up-regulated IFN signaling, immune cell communication, JAK and STAT signaling, cytokine-related signaling, and acute phase response signaling (Suppl. Table 2). Furthermore, Celastrol-treatment influenced signaling which could not have otherwise been predicted in control rats. For example, prolactin signaling. Celastrol might activate this signaling through STAT1 homodimers or STAT1/STAT3 heterodimers to activate IRF1 expression leading to induction of immune response. Sex hormones, especially prolactin and estrogen have been reported to have an immune stimulatory effect and to promote autoimmunity [41]. Furthermore, increased levels of prolactin display a positive correlation with active disease with joint destruction in RA [42]. However, other investigators failed to observe this specific correlation with RA [43]. Similarly, glucocorticoid (GC) receptor signaling was found to be activated only in the Celastrol-treated group. Glucocorticoids are part of the feedback mechanism in the immune system [44, 45]. Glucocorticoid receptor signaling up-regulates the expression of anti-inflammatory proteins in the nucleus (trans-activation) and represses the expression of pro-inflammatory proteins in the cytosol by preventing the translocation of other transcription factors from the cytosol into the nucleus (trans-repression), leading subsequently to inhibit immune activity and inflammation.

The precise autoantigen in RA is still unclear. According to the reactivity of antibodies present in the sera of RA patients as well as the testing of synovium-infiltrating T cells, various antigens including Bhsp65 have been implicated in the pathogenesis of RA [11, 46]. In the AA model used in the present study, arthritis is induced in LEW rats by injection of Mtb. Mtb has multiple antigens, including different Hsps (e.g., Hsps of the families Hsp60, Hsp70, Hsp10, etc.), and some of these antigens also can modulate the course of AA [47]. The Celastrol-induced changes in gene expression described above are primarily focused on Bhsp65-restimulated LNC. However, in arthritic rats immunized with Mtb, other antigens besides Bhsp65 also can induce changes in gene expression. This change in gene expression caused by different antigens will be reflected in the expression profile of LNC tested ex vivo (without further antigenic restimulation in vitro before testing). However, the major changes in gene expression observed after in vitro restimulation of LNC with Bhsp65 should be mostly specific for Bhsp65, except for a few fortuitously crossreactive epitopes that might be shared with Hsps of other family members or non-Hsp antigens. Thus, the difference in the gene expression profile of Bhsp65-restimulated LNC and ex vivo LNC would give us a reliable indication of Bhsp65-specific effects on gene expression. However, since modulation of arthritis by different antigens apparently would influence common effector pathways (e.g., cytokine responses, cell proliferation, metabolism, etc.), we anticipate that some of the changes observed in our study with Bhsp65 restimulation of LNC might also be observed when LNC are restimulated other mycobacterial Hsps or non-Hsp arthritis-related antigens.

To the best of our knowledge, the current study is the first global gene expression profiling and pathway analysis in Celastrol-treated arthritic Lewis rats compared to controls. Our results showed that Celastrol actively modulated immune responses rather than inducing global immunosuppression. Thus, Celastrol has the potential to control harmful inflammatory and other disease-related events in arthritis without compromising the host’s immune system. Our results point to the “Celastrol Signature” consisting of 10 gene sand 14 pathways (Table 3 and Suppl. Table 2) that are uniquely as well as maximally influence by Celastrol treatment leading to the suppression of AA. The “Celastrol Signature” genes are coding IFN-γ, IL-9, IL-22, LPL, GZMB, LIF47, C2, SPP1, DRD4. The “Celastrol Signature” pathways are including: role of hypercytokinemia/hyperchemokinemia in pathogenesis of influenza, activation of IRF by cytosolic pattern recognition receptor, role of JAK1 and JAK3 in γc cytokine signaling, antigen presentation pathway, aminoacyl-tRNA biosynthesis, biosynthesis of steroids, TWEAK signaling, granzyme B signaling, CD27 signaling in T lymphocytes, lymphotoxin β receptor signaling, IL-17 signaling, B cell development, prolactin signaling, glucocorticoid receptor signaling, nitrogen metabolism. Many of the targets and pathways influenced by Celastrol revealed in our study have also been found in a proteomics-based study on human lymphoblastoid cells treated with Celastrol in vitro [48] and in another study using HeLa and other cell lines [49]. In comparison, our study involves the treatment of arthritic rats by Celastrol in vivo and then testing of their draining LNC for gene expression by microarrays. Taken together, the results of these studies would help identify potential targets for the control of inflammation and arthritis.

Highlights.

Celastrol, a bioactive of Chinese herb Celastrus, possesses anti-arthritic activity.

76 differentially regulated genes were identified in Celastrol-treated rats.

14 genes were unique to Celastrol-treated arthritic rats.

Celastrol-altered genes were related to inflammation and immune responses.

10 genes and 14 pathways constituted the “Celastrol Signature”.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants R01AT004321 from the National Institutes of Health (Bethesda, MD, USA). We thank Jing Yin and Li Tang for their help with microarray hybridization and signal readout.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Feldmann M, Brennan FM, Maini RN. Rheumatoid arthritis. Cell. 1996 May 3;85(3):307–310. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81109-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gorman CL, Cope AP. Immune-mediated pathways in chronic inflammatory arthritis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2008 Apr;22(2):221–238. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lipsky PE. Rheumatoid arthritis. In: Fauci EB A, Kasper D, Hauser S, longo D, Jameson J, Loscalzo J, editors. Harrison's Principles of Intenrnal Medicine. 17 ed. New York: McGraw Hill New York, NY, USA; 2008. pp. 2083–2092. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bartok B, Firestein GS. Fibroblast-like synoviocytes: key effector cells in rheumatoid arthritis. Immunol Rev. Jan;233(1):233–255. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2009.00859.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Firestein GS. The T cell cometh: interplay between adaptive immunity and cytokine networks in rheumatoid arthritis. J Clin Invest. 2004 Aug;114(4):471–474. doi: 10.1172/JCI22651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pratt AG, Isaacs JD, Mattey DL. Current concepts in the pathogenesis of early rheumatoid arthritis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2009 Feb;23(1):37–48. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2008.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sato K, Takayanagi H. Osteoclasts, rheumatoid arthritis, and osteoimmunology. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2006 Jul;18(4):419–426. doi: 10.1097/01.bor.0000231912.24740.a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ziff M. Pathways of mononuclear cell infiltration in rheumatoid synovitis. Rheumatol Int. 1989;9(3–5):97–103. doi: 10.1007/BF00271865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bendele AM, Chlipala ES, Scherrer J, Frazier J, Sennello G, Rich WJ, et al. Combination benefit of treatment with the cytokine inhibitors interleukin-1 receptor antagonist and PEGylated soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor type I in animal models of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis and rheumatism. 2000 Dec;43(12):2648–2659. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200012)43:12<2648::AID-ANR4>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schoft LRAK, Jaffee BD. Rat models of arthritis: similarities, differences, advantages, and disadvantages in the identification of novel therapeutics. 2006:1–34. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang MN, Yu H, Moudgil KD. The involvement of heat-shock proteins in the pathogenesis of autoimmune arthritis: a critical appraisal. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2010 Oct;40(2):164–175. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2009.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moudgil KD, Chang TT, Eradat H, Chen AM, Gupta RS, Brahn E, et al. Diversification of T cell responses to carboxy-terminal determinants within the 65-kD heat-shock protein is involved in regulation of autoimmune arthritis. J Exp Med. 1997 Apr 7;185(7):1307–1316. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.7.1307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yu H, Yang YH, Rajaiah R, Moudgil KD. Nicotine-induced differential modulation of autoimmune arthritis in the Lewis rat involves changes in interleukin-17 and anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies. Arthritis and rheumatism. 2011 Apr;63(4):981–991. doi: 10.1002/art.30219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cameron M, Gagnier JJ, Little CV, Parsons TJ, Blumle A, Chrubasik S. Evidence of effectiveness of herbal medicinal products in the treatment of arthritis. Part 2: Rheumatoid arthritis. Phytother Res. 2009 Dec;23(12):1647–1662. doi: 10.1002/ptr.3006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Canter PH, Lee HS, Ernst E. A systematic review of randomised clinical trials of Tripterygium wilfordii for rheumatoid arthritis. Phytomedicine. 2006 May;13(5):371–377. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2006.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tao X, Younger J, Fan FZ, Wang B, Lipsky PE. Benefit of an extract of Tripterygium Wilfordii Hook F in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Arthritis and rheumatism. 2002 Jul;46(7):1735–1743. doi: 10.1002/art.10411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Soeken KL, Miller SA, Ernst E. Herbal medicines for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2003 May;42(5):652–659. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keg183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kala CPDP, Sajwan BS. Developing the medicinal plants sector in northern India: challenges and opportunities. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2006;2:32. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sassa H, Takaishi Y, Terada H. The triterpene celastrol as a very potent inhibitor of lipid peroxidation in mitochondria. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1990 Oct 30;172(2):890–897. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(90)90759-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Allison AC, Cacabelos R, Lombardi VR, Alvarez XA, Vigo C. Celastrol, a potent antioxidant and anti-inflammatory drug, as a possible treatment for Alzheimer's disease. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2001 Oct;25(7):1341–1357. doi: 10.1016/s0278-5846(01)00192-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim DH, Shin EK, Kim YH, Lee BW, Jun JG, Park JH, et al. Suppression of inflammatory responses by celastrol, a quinone methide triterpenoid isolated from Celastrus regelii. Eur J Clin Invest. 2009 Sep;39(9):819–827. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2009.02186.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jaquet V, Marcoux J, Forest E, Leidal KG, McCormick S, Westermaier Y, et al. NADPH oxidase (NOX) isoforms are inhibited by celastrol with a dual mode of action. Br J Pharmacol. 2011 Sep;164(2b):507–520. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01439.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Venkatesha SH, Yu H, Rajaiah R, Tong L, Moudgil KD. Celastrus-derived celastrol suppresses autoimmune arthritis by modulating antigen-induced cellular and humoral effector responses. J Biol Chem. 2011 Apr 29;286(17):15138–15146. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.226365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cascao R, Vidal B, Raquel H, Neves-Costa A, Figueiredo N, Gupta V, et al. Effective treatment of rat adjuvant-induced arthritis by celastrol. Autoimmun Rev. 2012 Mar 3; doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2012.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Durai M, Kim HR, Moudgil KD. The regulatory C-terminal determinants within mycobacterial heat shock protein 65 are cryptic and cross-reactive with the dominant self homologs: implications for the pathogenesis of autoimmune arthritis. J Immunol. 2004 Jul 1;173(1):181–188. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.1.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brazma A, Hingamp P, Quackenbush J, Sherlock G, Spellman P, Stoeckert C, et al. Minimum information about a microarray experiment (MIAME)-toward standards for microarray data. Nat Genet. 2001 Dec;29(4):365–371. doi: 10.1038/ng1201-365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dia VPdM EG. Differential gene expression of RAW 264.7 macrophages in response to the RGD peptide lunasin with and without lipopolysaccharide stimulation. Peptides. 2011 Oct;32(10):1979–1988. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2011.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li CJ, Li RW, Wang YH, Elsasser TH. Pathway analysis identifies perturbation of genetic networks induced by butyrate in a bovine kidney epithelial cell line. Funct Integr Genomics. 2007 Jul;7(3):193–205. doi: 10.1007/s10142-006-0043-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li CJL, Kahl RW, Elsasser S, H T. Alpha-Tocopherol Alters Transcription Activities that Modulates Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha (TNF-alpha) Induced Inflammatory Response in Bovine Cells. Gene Regul Syst Bio. 2012;6:1–14. doi: 10.4137/GRSB.S8303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001 Dec;25(4):402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tong L, Moudgil KD. Celastrus aculeatus Merr. suppresses the induction and progression of autoimmune arthritis by modulating immune response to heat-shock protein 65. Arthritis Res Ther. 2007;9(4):R70. doi: 10.1186/ar2268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Godkar PB, Gordon RK, Ravindran A, Doctor BP. Celastrus paniculatus seed oil and organic extracts attenuate hydrogen peroxide- and glutamate-induced injury in embryonic rat forebrain neuronal cells. Phytomedicine. 2006 Jan;13(1–2):29–36. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2003.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sassa H, Kogure K, Takaishi Y, Terada H. Structural basis of potent antiperoxidation activity of the triterpene celastrol in mitochondria: effect of negative membrane surface charge on lipid peroxidation. Free Radic Biol Med. 1994 Sep;17(3):201–207. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(94)90075-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miltenburg AM, van Laar JM, de Kuiper R, Daha MR, Breedveld FC. T cells cloned from human rheumatoid synovial membrane functionally represent the Th1 subset. Scand J Immunol. 1992 May;35(5):603–610. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.1992.tb03260.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roux SBJP. Osteoclast Apoptosis in Rheumatic Diseases Characterized by a High Level of Bone Resorption (Osteoporosis, Rheumatoid Arthritis, Myeloma and Paget’s Disease of Bone) Current Rheumatology Reviews. 2009;5:98–110. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Braun T, Zwerina J. Positive regulators of osteoclastogenesis and bone resorption in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 13(4):235. doi: 10.1186/ar3380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kamolmatyakul S, Chen W, Li YP. Interferon-gamma down-regulates gene expression of cathepsin K in osteoclasts and inhibits osteoclast formation. J Dent Res. 2001 Jan;80(1):351–355. doi: 10.1177/00220345010800011001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Udagawa N, Horwood NJ, Elliott J, Mackay A, Owens J, Okamura H, et al. Interleukin-18 (interferon-gamma-inducing factor) is produced by osteoblasts and acts via granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor and not via interferon-gamma to inhibit osteoclast formation. J Exp Med. 1997 Mar 17;185(6):1005–1012. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.6.1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Inoue H, Hiraoka K, Hoshino T, Okamoto M, Iwanaga T, Zenmyo M, et al. High levels of serum IL-18 promote cartilage loss through suppression of aggrecan synthesis. Bone. 2008 Jun;42(6):1102–1110. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2008.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim D, Song J, Kim S, Chun CH, Jin EJ. MicroRNA-34a regulates migration of chondroblast and IL-1beta-induced degeneration of chondrocytes by targeting EphA5. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. Dec 2;415(4):551–557. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.10.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shelly SBM, Orbach H. Prolactin and autoimmunity. Autoimmun Rev. 2011 Dec 2; doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2011.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fojtikova MTSJ, Filkova M, Lacinova Z, Gatterova J, Pavelka K, Vencovsky J, Senolt L. Elevated prolactin levels in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: association with disease activity and structural damage. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2011 Nov-Dec;28(6):849–854. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dostal C, Fojtikova M, Lacinova Z, Cerna M, Moszkorzova L, Zvarova J, et al. Prolactin response to stress in patients with systemic lupus erythematodes (SLE), rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and in healthy controls. Vnitr Lek. 2007 Dec;53(12):1265–1268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Flammer JRRI. Minireview: Glucocorticoids in autoimmunity: unexpected targets and mechanisms. Mol Endocrinol. 2011 Jul;25(7):1075–1086. doi: 10.1210/me.2011-0068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang Y, Ma YY, Song XL, Cai HY, Chen JC, Song LN, et al. Upregulations of glucocorticoid-induced leucine zipper by hypoxia and glucocorticoid inhibit proinflammatory cytokines under hypoxic conditions in macrophages. J Immunol. 2012 Jan 1;188(1):222–229. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Corrigall VM, Panayi GS. Autoantigens and immune pathways in rheumatoid arthritis. Crit Rev Immunol. 2002;22(4):281–293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kim EY, Moudgil KD. The determinants of susceptibility/resistance to adjuvant arthritis in rats. Arthritis Res Ther. 2009;11(4):239. doi: 10.1186/ar2755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hansen J, Palmfeldt J, Vang S, Corydon TJ, Gregersen N, Bross P. Quantitative proteomics reveals cellular targets of celastrol. PLoS One. 2011;6(10):e26634. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang WB, Feng LX, Yue QX, Wu WY, Guan SH, Jiang BH, et al. Paraptosis accompanied by autophagy and apoptosis was induced by celastrol, a natural compound with influence on proteasome, ER stress and Hsp90. J Cell Physiol. 2012 May;227(5):2196–2206. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]