Abstract

The loss of the H2O2 scavenger protein encoded by Prdx1 in mice leads to an elevation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and tumorigenesis of different tissues. Loss of heterozygosity (LOH) mutations could initiate tumorigenesis through loss of tumor suppressor gene function in heterozygous somatic cells. A connection between the severity of ROS and the frequency of LOH mutations in vivo has not been established. Therefore, in this study, we characterized in vivo LOH in ear fibroblasts and splenic T cells of 3–4 month old Prdx1 deficient mice. We found that the loss of Prdx1 significantly elevates ROS amounts in T cells and fibroblasts. The basal amounts of ROS were higher in fibroblasts than in T cells, probably due to a less robust Prdx1 peroxidase activity in the former. Using Aprt as a LOH reporter, we observed an elevation in LOH mutation frequency in fibroblasts, but not in T cells, of Prdx1−/− mice compared to Prdx1+/+ mice. The majority of the LOH mutations in both cell types were derived from mitotic recombination (MR) events. Interestingly, Mlh1, which is known to suppress MR between divergent sequences, was found to be significantly down-regulated in fibroblasts of Prdx1−/− mice. Therefore, the combination of elevated ROS amounts and down-regulation of Mlh1 may have contributed to the elevation of MR in fibroblasts of Prdx1−/− mice. We conclude that each tissue may have a distinct mechanism through which Prdx1 deficiency promotes tumorigenesis.

Keywords: reactive oxygen species, loss of heterozygosity, peroxiredoxin 1, mutations

1. Introduction

Reactive oxygen species (ROS), specifically, superoxide radicals (O2−), are produced as the by-products of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation and various metabolic processes. The superoxide radicals are dismutated to hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) by a family of superoxide dismutase (Sod) enzymes functional in different sub-cellular compartments [1]. H2O2 is then converted to H2O and O2 by different families of peroxidases: catalase, glutathione peroxidases (Gpxs) and peroxiredoxins (Prdxs). Prdx1 is easily over-oxidized due to its Cys51 that during catalysis exists as thiolate anion, whereas the other cysteines (Cys17, Cys80 and Cys172) remain protonated at neutral pH. The thiolate Cys51 is very unstable and highly reactive with any accessible thiol to form either a disulfide or to further oxidize to sulfinic or sulfonic acid structures [2], which are believed to possess peroxidase-inactive chaperone functions (reviewed in [3]). The switch to chaperone functionality leads to catalase activity that scavenges more of the cellular H2O2. Overall, the peroxidases sequentially maintain homeostatic amounts of H2O2, which curtails the formation of highly reactive hydroxyl (OH•) radicals (through the Fenton reaction).

Elevated amounts of intracellular ROS (oxidative stress) produced as a result of an exogenous stressor (e.g., H2O2 or irradiation) can damage DNA, protein and lipids through oxidation. At least 100 different types of oxidative DNA lesions are known to form, which include base modifications (e.g. 8-oxo-guanine (8-oxoG), thymidine glycol & 8-hydroxycytosine), single-strand breaks (SSBs), double-strand breaks (DSBs) and interstrand cross-links [4]. For example, H2O2 treatment of human T-lymphocytes led to increased Hprt mutant frequency with a majority of mutations classified as transitions at GC base pairs [5]. Additionally, oxidative DNA damage could stem from compromised ROS scavenging such as in the case of Prdx1 deficient mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) that exhibited increased ROS amounts compared to wild-type MEFs and an elevated number of 8-oxoG DNA lesions [6]. Moreover, there was also greater oxidation of hemoglobin in Prdx1 deficient erythrocytes as evidenced by the appearance of Heinz bodies and eventual hemolytic anemia. A separate study involving adult Prdx1−/− mice found increased levels of various types of oxidative DNA lesions in the brain, spleen and liver [7]. In addition to causing DNA base damage, elevated ROS could also lead to increased frequency of loss of heterozygosity (LOH) mutations primarily derived from mitotic recombination (MR) events that originated in response to the need for DNA DSB repair [8, 9].

LOH is frequently a rate-limiting step in tumorigenesis [10] and increased frequency of LOH mutations is positively correlated with increased cancer incidence such as that which is observed in Prdx1-deficient mice [6]. We have previously utilized Aprt+/− mice as a model system to study in vivo LOH [11, 12]. Cells that have undergone in vivo LOH that includes Aprt are recovered as cell colonies in vitro by virtue of their resistance to 2,6-diaminopurine (DAP). The recovered colonies can then be analyzed to determine the mutational mechanism that produced the in vivo LOH. In order to determine whether LOH is elevated in vivo by ROS, which may consequently contribute to increased tumorigenesis, we measured the spontaneous LOH mutant frequencies in ear fibroblasts and splenic T cells of Prdx1 deficient mice. We observed that while ROS amounts are increased in both fibroblasts and T cells derived from Prdx1−/− mice, they are much higher in fibroblasts than in T cells regardless of Prdx1 functional status. Correspondingly, significant elevations in Aprt LOH mutant frequencies were found only in Prdx1+/− and Prdx1−/− fibroblasts.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Mice Breeding

129XC57 Prdx1+/− and Prdx1−/− male mixed strain mice were as described [6]. These mice were backcrossed to 129 strain and C57 strain, respectively, for four generations. We utilized “speed congenics” by analyzing distribution of microsatellite markers along chromosome 8 to determine the appropriate mice for mating for the subsequent generation until pure strain 129 or C57 mice were generated. The N4 129 Prdx1+/− mice were then crossed with 129 Aprt+/− mice to generate N5 129 Prdx1+/− Aprt+/− mice. These mice were then crossed with N4 C57 Prdx1+/− mice to generate N5 129X N4 C57 hybrid Prdx1 (+/+, +/− and −/−) Aprt+/− mice.

2.2 Cell culture and calculations of Aprt mutant frequency

Ear fibroblasts and splenic T cells were derived from 3–4 month old mice as described in previous studies [11,13,14]. We recovered DAP-resistant (DAPr) clones from fibroblasts (100mm plates) and T cells (96-well plates) by culturing them in supplemented DMEM or RPMI medium (Hyclone), respectively, containing 50µg/ml DAP. DAPr colonies were picked at day 12 or day 9 after plating, for fibroblasts and T cells, respectively. At the same time, plates for colony-forming efficiency were established for fibroblasts (1×104 cells/plate) and T cells (4 cells/well) and positive colonies counted at day 11 or day 8 after plating, respectively. Colony-forming efficiency and DAPr mutant frequency calculations were done as previously described [13].

2.3 Molecular Analyses of DAPr clones

DAPr mutant clones were classified into class I or class II by loss or presence of the Aprt+ allele, as described elsewhere (11). Class I clones were further characterized using microsatellite markers along chromosome 8 (D8Mit56, 271, 106, 125 and 155). Clones that exhibited LOH at distal loci, including Aprt, but remained heterozygous near the centromere were considered to be derived from mitotic recombination (MR). Class I clones with LOH at both D8Mit56 (telomeric) and D8Mit155 (centromeric) were regarded as the product of chromosomal loss (CL), and clones that did not exhibit LOH at D8Mit56 and D8Mit155 were classified as originating from either gene conversion (GC) or interstitial deletion (ID).

2.4 ROS measurements

Prior to plating the cells for the Aprt LOH studies, 1×105 concanavalin A (ConA) splenic T cells and ear fibroblasts were incubated with 5µM of 5-(and-6)-chloromethyl-2',7'-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (CM-H2DCFDA, Invitrogen™) (DCF) in the dark at 37°C for 22 minutes. Background controls included cells in medium without DCF. The cells were centrifuged, resuspended in 1X PBS, for flow cytometry analyses using the Beckman Coulter FC500 Analyzer with 10,000 cells gated for each cell type, and fluorescence (Excitation: 488nm, Emission: 525nm) measured using the FL1 channel.

2.5 RNA extraction and gene expression studies

RNA was isolated from 1×106 primary ear fibroblasts and 1×106 ConA stimulated T cells from 3–4 month old Prdx1+/+ and Prdx1−/− mice (n=3) using the Qiagen RNeasy Mini Kit using the recommended protocol with the optional DNase on-column treatment. Concentration of RNA, 260/280 and 260/230 values were measured using the ND-1000 spectrophotometer with integrity of RNA (18s and 28s bands) determined through agarose gel electrophoresis. Each RNA sample was reverse transcribed to cDNA using the TaqMan® Reverse Transcription Reagents (Applied Biosystems™). RNA expression of the genes in Table 1 was measured using the Applied Biosystems 7900HT Sequence Detection System with B-actin as the loading control. PCR conditions were: 50°C for 2 minutes, 95°C for 10 min followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15s and 60°C for 1 min. The primer sequences were designed using the Primer Express v2.0 software and each sample-primer pair was run in triplicate.

Table 1.

Sequence of RT primers of antioxidant genes used in qPCR experiments.

| Gene | Accession No. | Forward Primer | Reverse Primer |

|---|---|---|---|

| B-actin | NM_007393.3 | GACGGCCAGGTCATCACTATTG | AGTTTCATGGATGCCACAGGAT |

| Catalase | NM_009804.2 | CCATCGCCAATGGCAATTAC | AGGCCAAACCTTGGTCAGATC |

| Gpx1 | NM_008160.6 | CCGCTTTCGTACCATCGACAT | CCAGTAATCACCAAGCCAATGC |

| Mlh1 | NM_026810.2 | CGGCCAATGCTATCAAAGAGA | CCAGTGCCATTGTCTTGGATC |

| Prdx1 | NM_011034.4 | AGTCCAGGCCTTCCAGTTCACT | GGCTTGATGGTATCACTGCCAG |

| Prdx2 | NM_011563.5 | AAGGACACCACTGGCATCGAT | CACACAATTACGGCGTGTTGAA |

| Prdx5 | NM_012021.2 | GTGTTTTGTTTGGAGTCCCTGG | AATAACGCTCAGACAGGCCAC |

| Prdx6 | NM_007453.3 | TTTGAGGCCAATACCACCATC | TGCCAAGTTCTGTGGTGCA |

| Rad51 | NM_011234.4 | AGCGTCAGCCATGATGGTAGAA | TTTGCCTGGCTGAAAGCTCTC |

| Sod1 | NM_011434.1 | AAGCATGGCGATGAAAGCG | ACAACACAACTGGTTCACCGC |

2.6 Prdx1 western blot analyses

Primary ear fibroblasts and ConA stimulated T cells from 3–4 month old Prdx1+/+ mice were isolated and cultured as described in the RNA expression studies. For this study, 1×106 T cells and 1×106 ear fibroblasts suspended in 1mL of their respective medium were used for each treatment group. Different concentrations of H2O2 (0, 20µM, 50µM and 250µM) were added directly to each cell suspension and incubated for 15 minutes in a 37°C, 95% RH and 10% CO2 incubator. The suspension was then centrifuged, the pellet washed with PBS and the washed pellet resuspended in 150µL of protein extraction buffer (20mM HEPES and 0.1% Triton X-100, pH 7.4). The pellet was then centrifuged at 4000×g and the supernatant collected; protein concentration of the supernatant was determined by a standard BCA assay. 30µg of protein was analyzed for Prdx1 and Prdx1C53SO3 protein expression under non-reducing and reducing (beta-mercaptoethanol added to extraction buffer) conditions. Actin was used as a loading control. All antibodies were from Abcam.

2.7 Statistical Analyses

The Mann Whitney U-test (p<0.05) was utilized to determine significant differences between median Aprt LOH mutant frequencies. Student t-test analysis was utilized to determine significance for DCF fluorescence measurements, with p<0.05 considered significant. For the gene expression analyses, a significant change was considered to be ≥ 2-fold difference with p<0.05 as determined by the student t-test.

3. Results

3.1 Increased ROS amounts in ear fibroblasts and splenic T cells of Prdx1−/− mice

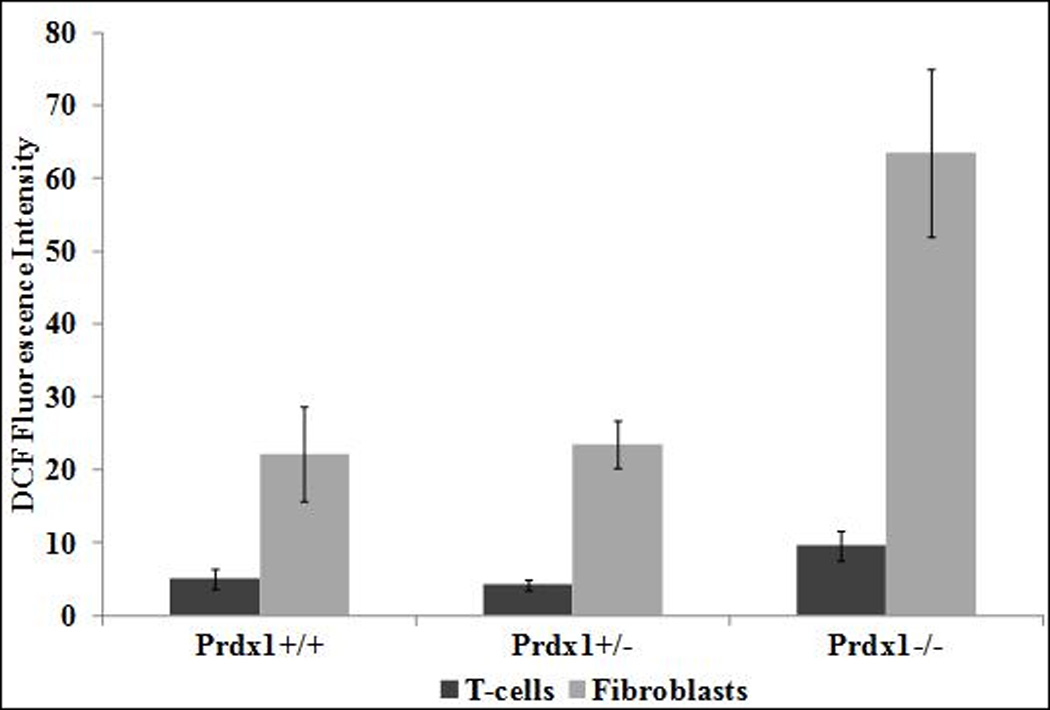

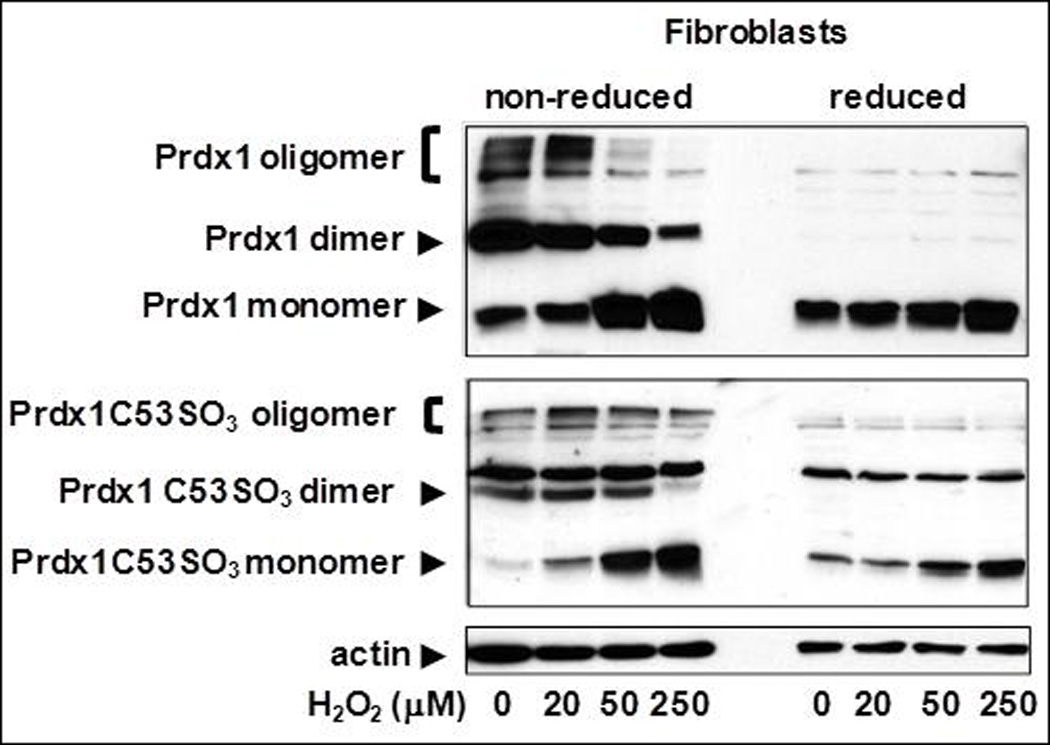

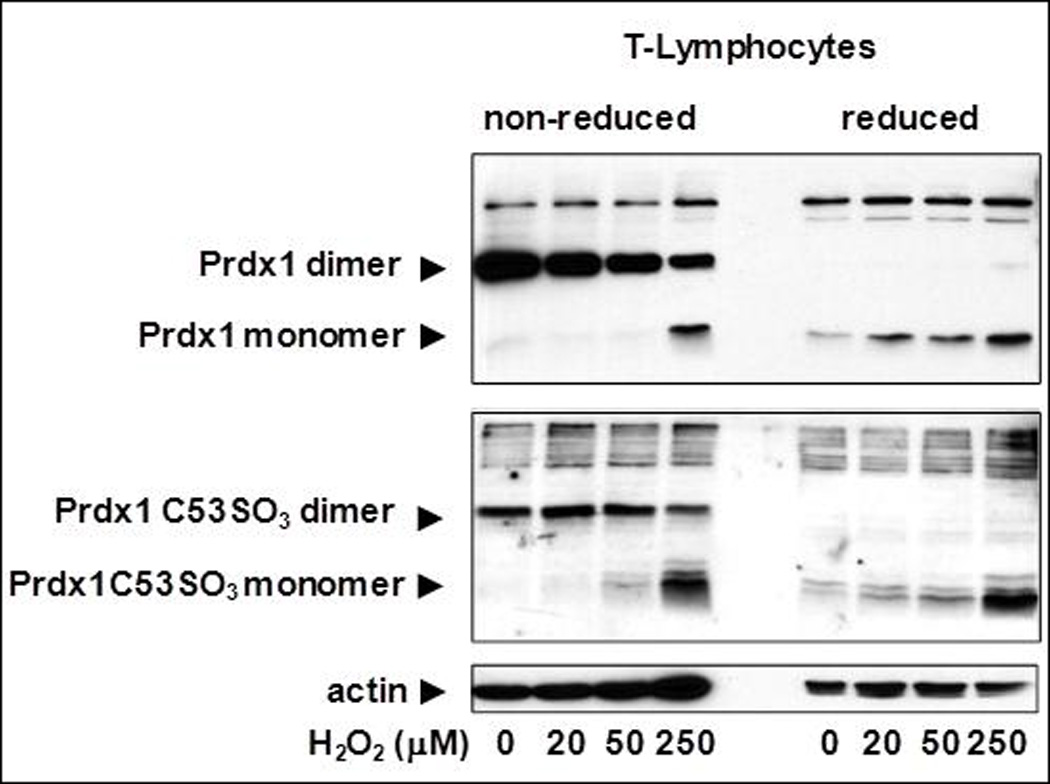

We previously showed that loss of Prdx1 in MEFs led to increased amounts of ROS [6]; therefore, we wanted to determine if it had a similar impact in splenic T cells and in ear fibroblasts. ROS amounts were quantified by measuring the amount of intracellular CMH2DCFDA that is cleaved by intracellular esterases and made fluorescent under oxidizing conditions [15]. Indeed, significantly higher amounts of ROS were observed with the complete loss of Prdx1 in both T cells and fibroblasts; ROS amounts were unaffected in Prdx1+/− T cells and Prdx1+/− fibroblasts (Figure 1A). Furthermore, the ROS amounts in fibroblasts, in general, were higher than in splenic T cells. To determine if this was due to differences in Prdx1 peroxidase activity between cell types, we examined Prdx1 protein monomer, dimer and oligomer formation in T cells and primary fibroblasts of Prdx1+/+ mice after treatment with increasing concentrations of H2O2. The reduction of H2O2 to H2O and O2 by Prdx1 requires the formation of a disulfide bridge between two monomers, resulting in a dimer. In fibroblasts, with increasing concentrations of H2O2, we found a gradual decrease in dimer formation with a corresponding increase in monomer formation (Figure 1B-top panel), which was not observed in T cells except at the highest H2O2 treatment concentration (250µM) (Figure 1C-top panel). Moreover, we observed reducible Prdx1 oligomers only in the fibroblasts, which decreased after H2O2 treatment, suggesting greater H2O2-induced overoxidation of Prdx1 in those cells compared to T cells. Along those lines, an antibody specifically detecting Prdx1 overoxidized at its catalytic cysteine revealed a greater amount of overoxidized Prdx1 in fibroblasts compared to T cells (Figures 1B and 1C-bottom panels).

Fig. 1.

(A) DCF fluorescence intensity measured by flow cytometry in T cells and fibroblasts isolated from Prdx1+/+, Prdx1+/− and Prdx1−/− mice. (B) and (C) Immunoblots of non-reduced and reduced (with beta-mercaptoethanol) protein lysates from H2O2 treated Prdx1+/+ primary ear fibroblasts splenic T cells, respectively, prepared as discussed under Materials and Methods. Normal Prdx1 (top panels) and oxidized (Prdx1C53SO3-bottom panels) protein expression. 30µg of protein was loaded per lane. * p<0.05

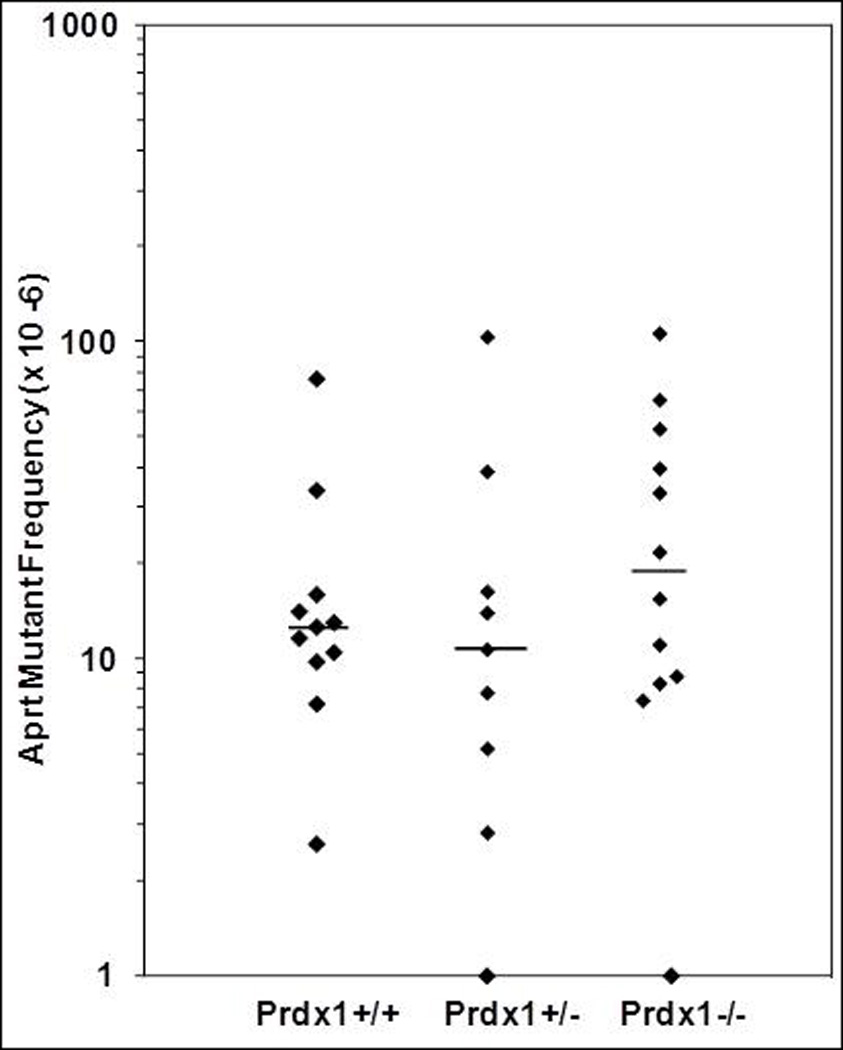

3.2 Increased LOH mutant frequency in ear fibroblasts of Prdx1−/− mice

Given the significant increase in ROS amounts observed in Prdx1−/− fibroblasts, we wanted to determine whether or not there was also a significant elevation of in vivo LOH mutant frequency as reported for in vitro LOH studies [8, 9]. There was a significant elevation (4.5-fold; p=0.01) in Aprt LOH mutant frequency in fibroblasts of Prdx1−/− mice compared to those of Prdx1+/+ mice (Figure 2A and Table 2-top panel). Surprisingly, the Prdx1+/− fibroblasts in which ROS amounts were not detectably increased also had a significant elevation (2.3-fold; p=0.04) in Aprt LOH mutant frequency; however, no LOH was observed at the Prdx1 locus in the Prdx1+/− clones (data not shown). The majority of Aprt LOH clones across all Prdx1 genotypes were designated as class I because they exhibited physical loss of the wild-type Aprt allele (Table 2-top panel). Consistent with Aprt LOH spectrums in previous reports, class I clones were derived primarily from MR as determined by chromosome 8 microsatellite marker analyses (Table 3). A small number of class I clones were derived from individual interstitial deletion/gene conversion (ID-GC) events in Prdx1+/− (4 clones) and Prdx1−/− (2 clones) fibroblasts, where each clone was independently derived from a different mouse. Additionally, six clones from one ear of a Prdx1−/− mouse exhibited LOH at all the marker loci tested (Table 3), suggesting that they may have been derived from chromosomal loss (CL). Because they were derived from a single mouse ear, they were probably sib clones.

Fig. 2.

(A) Frequency of DAPr fibroblasts in individual mouse ears where each point represents the frequency of DAPr fibroblasts from one ear. (B) Frequency of DAPr T cells from individual mouse spleens where each point represents the frequency of DAPr T cells from one spleen. The bars indicate median frequencies. Points at the x-axis intersect represent fibroblast or T-cell cultures from which no DAPr colonies were recovered.

Table 2.

Cloning efficiency, mutant frequency and classification of clones derived from ear fibroblasts and T cells.

| Cell Type | Genotype | No. of ears | Cloning efficiency % (mean±s.e.) |

DAPr frequency (× 10−6)a |

No. of DAPr colonies analyzed |

% class I colonies |

Class I frequency (× 10−6)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fibroblasts | Prdx1+/+ | 15 | 1.29±0.07 | 37.9 | 16 | 75 | 28.4 |

| Prdx1+/− | 18 | 1.38±0.06 | 89.3* | 31 | 74 | 66.3 | |

| Prdx1−/− | 21 | 1.26±0.05 | 169* | 53 | 79 | 134 | |

| Cell Type | Genotype | No. of mice |

Cloning efficiency % (mean ± s.e.) |

DAPr frequency (× 10−6)a |

No. of DAPr colonies analyzed |

% class I colonies |

Class I frequency (× 10−6)b |

| T-cells | Prdx1+/+ | 11 | 5.58 ± 1.17 | 11.6 | 33 | 82 | 9.5 |

| Prdx1+/− | 9 | 7.09 ± 1.42 | 10.7 | 34 | 79 | 8.5 | |

| Prdx1−/− | 12 | 4.21 ± 1.01 | 18.4 | 37 | 89 | 16.4 | |

Median frequency.

Calculated by multiplying DAPr frequency and % class I.

p<0.05, Mann Whitney U-test. s.e.- standard error.

Table 3.

Mutational spectrum of class I clones in T-cells and fibroblasts.

| Cell Type | Genotype | Mitotic recombination |

Deletion or gene conversion |

Chromosomal loss |

Total no. of clones |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fibroblasts | Prdx1+/+ | 12 | 0 | 0 | 12 |

| Prdx1+/− | 19 | 4 | 0 | 23 | |

| Prdx1−/− | 35 | 1 | 6 | 42 | |

| T-cells | Prdx1+/+ | 26 | 4 | 0 | 30 |

| Prdx1+/− | 24 | 3 | 0 | 27 | |

| Prdx1−/− | 30 | 1 | 2 | 33 |

3.3 LOH mutant frequency in T cells unaffected with loss of Prdx1

Unlike fibroblasts, no change in Aprt mutant frequency was observed in T cells with the loss of Prdx1 (Figure 2B and Table 2-bottom panel), although there was a significant elevation in the amounts of ROS (Figure 1A). All three Prdx1 genotypes exhibited a similar distribution of class I and class II Aprt LOH clones, with a slight but insignificant increase in the frequency of class I clones from Prdx1−/− mice (<2-fold) compared to Prdx1+/+ mice (Table 2-bottom panel). The majority of Aprt LOH class I clones were derived from MR events (85% in Prdx1+/+, 89% in Prdx1+/− and 91% in Prdx1−/−) (Table 3). ID and GC events were responsible for the remaining Prdx1+/+ (4 clones) and Prdx1+/− (3 clones) class I Aprt LOH clones, each derived from a different spleen. One Prdx1−/− class I Aprt LOH clone was derived from an ID-GC event and two clones exhibited LOH at all marker loci along the length of chromosome 8 (Table 3). Again, the two clones displaying whole chromosome LOH were derived from the same spleen and therefore, are considered sib clones.

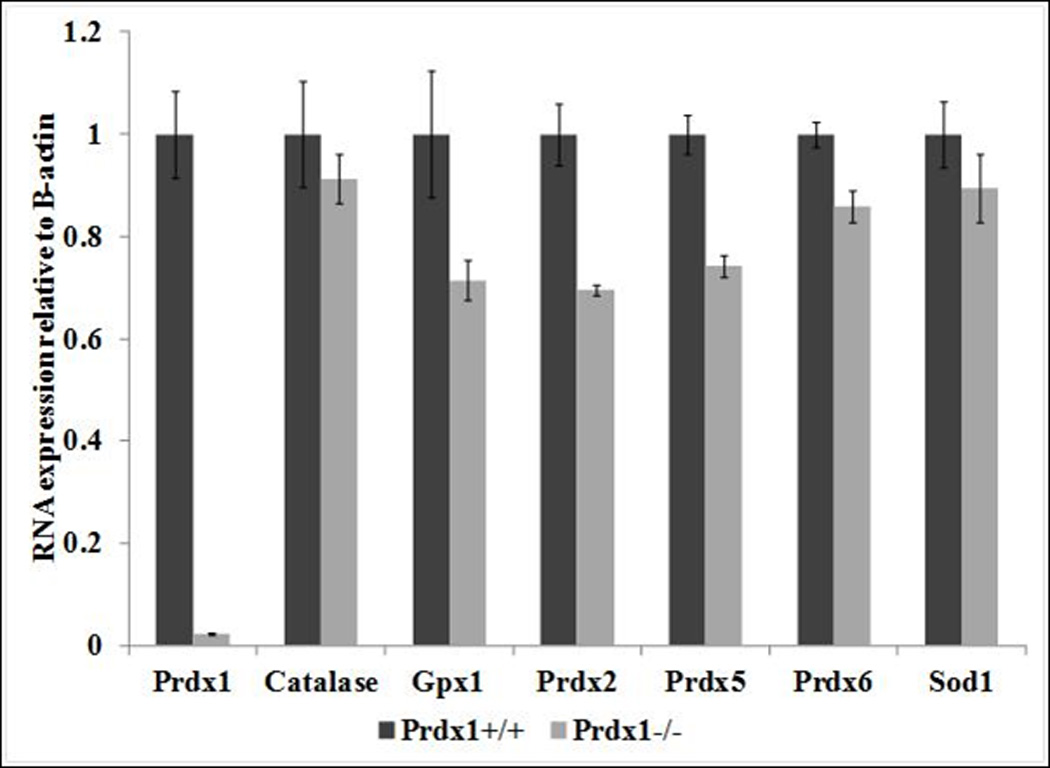

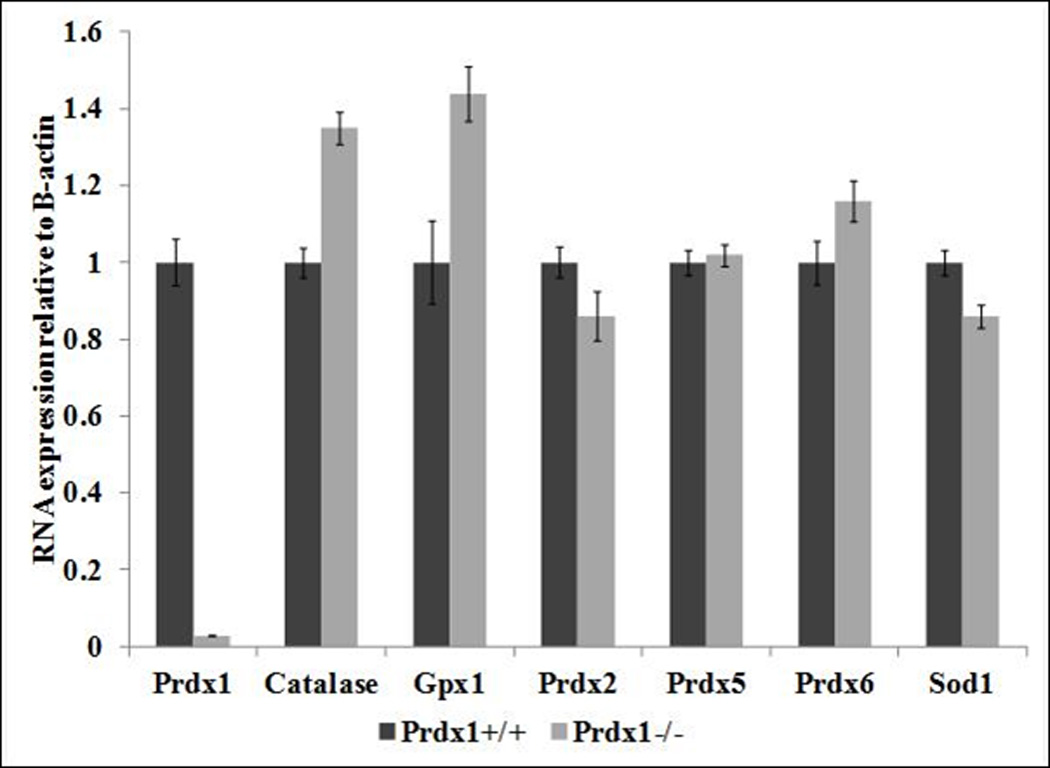

3.4 Expression of antioxidant and DNA repair genes in Prdx1−/− cells

A previous study reported that elevated ROS amounts observed in phosphatase and tensin homolog (Pten) deficient MEFs was due to down-regulation in mRNA expression of various genes that encode antioxidant proteins (Prdx1, Prdx2, Prdx5, Prdx6 and Sod1) [16]. Additionally, the Prdx1 protein binds to and protects the Pten protein from oxidation-induced inactivation, thus acting as a safeguard of Pten [17]. Therefore, we hypothesized that the loss of Prdx1 could lead to greater Pten inactivation in Prdx1−/− T cells and ear fibroblasts, which would result in transcriptional down-regulation in expression of certain antioxidant proteins [16] contributing to the elevated ROS amounts observed in those cells (Figure 1A). In addition to the genes that are regulated by Pten, we also examined the transcriptional expression of other important H2O2 scavengers, catalase and Gpx1. In both T cells and fibroblasts, the loss of Prdx1 did not lead to significant differences in transcription of genes that encode antioxidant proteins (Figure 3). Therefore, the increased ROS amounts observed in Prdx1−/− T cells and fibroblasts seems entirely due to loss of Prdx1 antioxidant functionality and independent of changes in the activity of Pten.

Fig. 3.

Relative mRNA expression of genes that encode antioxidant proteins in (A) T cells and in (B) primary fibroblasts derived from Prdx1+/+ and Prdx1−/− mice. Expression of Prdx1+/+ samples was normalized to 1.

Rad51 is a key component of DSB repair by homologous recombination. Since Pten positively regulates Rad51 expression [18]; increased inactivation of Pten with the loss of Prdx1 could lead to decreased expression of Rad51 and decreased DSB repair. The mismatch repair gene, Mlh1, is also known to effect HR mediated DSB repair by preventing recombination between divergent sequences. We have previously shown that Mlh1 deficiency led to significant elevation of mitotic recombination (MR) in ear fibroblasts [12]. Therefore, changes in transcription of either of these genes could likely have an effect on the frequency of MR mediated LOH mutant frequency. In both T cells and fibroblasts, the loss of Prdx1 had no significant effect on Rad51 expression. However, we found a significant 2-fold reduction in Mlh1 expression in Prdx1−/− fibroblasts and a slightly less reduction in Prdx1−/− T cells (1.7-fold) (Figure 4). The decrease in Mlh1 expression could contribute to the increased frequency of LOH mutants in Prdx1−/− fibroblasts.

Fig. 4.

Relative mRNA expression of Mlh1 and Rad51 in Prdx1+/+ and Prdx1−/− T cells and fibroblasts. *≥2-fold change and p<0.05. Expression of Prdx1+/+ samples was normalized to 1.

4. Discussion

We showed that the elevated ROS amounts in Prdx1−/− fibroblasts directly correlated to increased LOH mutant frequency, which we speculate is a direct consequence of an increased need for repair of DSBs through an increased accumulation of highly reactive OH• radicals [4] that occurs with the loss of Prdx1 [7]. Repair of DSBs could happen either by homologous recombination (HR) or non-homologous end-joining (NHEJ). A previous study found that mammalian cells in S-phase compared to cells in G1 phase are considerably more sensitive to the formation of DSBs induced by treatment with H2O2 [19]. It was hypothesized that the more open chromatin structure in S-phase makes DNA less protected against the attack by OH• radicals. This suggests that the repair of DSBs would rely more on HR than on NHEJ as NHEJ repair occurs primarily during the G1 phase. This could explain why the majority of the LOH mutants observed in Prdx1−/− fibroblasts were derived as a consequence of MR, a type of HR. Repair by NHEJ, which may result in deletion of several nucleotides around the DSB site, could be responsible for the interstitial deletion-gene conversion (ID-GC) events that took place in a small number of fibroblast clones.

Repair of DSBs by HR could be affected by deficiencies in other DNA repair pathways. The two-fold decrease in levels of Mlh1 mRNA expression, a key mismatch repair (MMR) gene, in Prdx1−/− fibroblasts is significant because MMR is known to suppress recombination between divergent DNA sequences, presumably to minimize inappropriate genome rearrangements as a consequence of DNA DSB repair [12, 20]. MMR stalls strand exchange during HR in the presence of mismatches, resulting in stabilized branch intermediates [21]. The down-regulation of Mlh1 in Prdx1−/− mice probably does not have a significant effect on MMR activity in T cells and its effect on the frequency of LOH mutations. Our previous study [12] found that while Mlh1 deficiency led to increased mitotic recombination (MR) in fibroblasts, it had no effect on MR in T cells. Instead, lack of Mlh1 led to increased point mutations, which was not observed in Prdx1−/− mice (data not shown). Because point mutations were not increased in Prdx1 deficient T cells (Table 3), the down-regulation of Mlh1 apparently had no effect on MMR. The transcriptional down-regulation of Mlh1 could be a consequence of increased methylation of the Mlh1 promoter [22, 23] mediated by c-Myc deregulation and activation [24, 25], which is known to occur with the loss of Prdx1 [7]. Activation of c-Myc also led to increased formation of DSBs in rat fibroblasts, due to loss of checkpoint response during G1/S, and consequently premature passage through G1 [26]. This would allow DNA DSB breaks to accumulate during S-phase, which would require repair by recombination that conserves DNA sequence.

Although increased Aprt LOH frequency was detected in the ear fibroblasts of Prdx1+/− mice, it was not accompanied by increased intracellular amounts of ROS (Figure 1A). Thus, an increase in the amounts of ROS may not fully account for the increased LOH in fibroblasts of Prdx1+/− and Prdx1−/− mice. It has been previously reported that Prdx1+/− MEFs had significantly increased Ras mediated transformation in comparison to Prdx1+/+ MEFs [7]. Therefore, we may speculate that increased c-Myc activation in Prdx1+/− fibroblasts lead to a compromise in G1/S checkpoint response, which in turn produced more DSBs. In Prdx1−/− fibroblasts, the increased activation of c-Myc may act synergistically with increased ROS amounts to promote LOH mutations that are mediated by HR. Another possibility is that cellular compartmentalization of limited amounts of the Prdx1 protein in Prdx1+/− fibroblasts may produce functional Prdx1 insufficiency in the nucleus relative to other cellular compartments. Thus, ROS levels could be increased in the nucleus but would be lower elsewhere in the cell, producing the observed average value for the entire cell.

Unlike our observations in Prdx1−/− fibroblasts, there was no correlation between elevated amounts of ROS and increased MR-mediated LOH mutant frequency in Prdx1−/− T cells. This disparity could be attributed to the much lower amounts of ROS in Prdx1−/− T cells relative to Prdx1−/− fibroblasts; ~4-fold lower ROS amounts were observed in Prdx1+/+ T cells relative to Prdx1+/+ fibroblasts (Figure 1A). Fibroblasts have reduced Prdx1 activity when compared to T cells, as evidenced by the greater formation of Prdx1 oligomers, monomers and the reduced formation of Prdx1 dimers compared to T cells when both are exposed to increasing amounts of H2O2 (Figures 1B and 1C). It has been shown that the extent of Prdx1 dimer formation is directly correlated to its catalytic activity because the Prdx1 catalytic cycle involves the formation of a disulfide bridge between the oxidized NH2-terminal Cys51-SOH on one monomer with the COOH-terminal Cys172-SH on the other monomer, resulting in dimer formation [27]. The cycle is completed with the reduction of the cysteines to –SH by thioredoxin (Trx) [28]. However, Cys51-SOH could be further oxidized to Cys51-SO2H before the formation of the disulfide bridge between Cys51 and Cys172; the over-oxidized Cys51 cannot bond with Cys172-SH [29] and thus results in inactivation of Prdx1 activity. In order to minimize this inactivation, cells have a sulfiredoxin protein that reduces Cys51-SO2H to Cys51-SOH [27]. Therefore, sulfiredoxin activity could be lower in fibroblasts compared to T cells, leading to a greater overoxidation of Prdx1 in fibroblasts compared to T cells. Another possibility is decreased thioredoxin (Trx) enzyme activity in T cells compared to fibroblasts. Recently it has been described that the extent of H2O2-induced overoxidation of the Prdx catalytic cysteine is directly correlated with thioredoxin activity. It is therefore likely that over-oxidation of the catalytic Prdx cysteine occurs during catalysis by binding of Trx to Prdx-disulfides, where the reduction process renders the reduced Cys51-SH to de-stabilization and over-oxidation in the presence of H2O2, by inhibiting the “sequestration” of reduced Cys51 in the active-site pocket [29]. Our observation of Prdx1 dimer formation is an indirect but most likely an accurate measurement of Prdx1 activity as was previously shown [17]. Overall, the complex cellular mechanism involved in Prdx1 scavenging likely play a role on the severity of ROS experienced by the different cells.

It was suggested that ROS exposure must reach a certain threshold in order to significantly promote DNA damage that would lead to LOH [9]. It was shown that only the higher dosages of H2O2 treatment (300–600µM) led to a significant 2–6 fold increase in MR mediated LOH frequency while no increase in LOH frequency was observed with a 200µM H2O2 treatment [9]. Lower amounts of ROS in T cells compared to fibroblasts and an absence of an effect with Mlh1 down-regulation may explain why there was no significant increase in LOH frequency in Prdx1−/− T cells. The cell-type specific effect of a decrease in Mlh1 expression in the absence of Prdx1 illustrates the complexity of mechanisms governing tumorigenesis in different tissues.

A possible mechanism underlying lymphoma formation in Prdx1 deficient mice could be de-regulation of c-Myc transcriptional regulation. The Prdx1 protein binds to the MBII region of the c-Myc protein [7], a region important for the transcriptional regulation of genes critical in the promotion of the cellular transformation (cell growth/proliferation and cell-cycle regulation) that is a key step in lymphomagenesis [30].

Our study indicated that increased in vivo ROS amounts may promote mutations in a cell type specific manner. This differential effect could be caused by differences in antioxidant defense and the relative robustness of the DNA repair machinery. Future studies would involve elucidating these differences through gene expression, protein interaction and enzyme activity assays in both fibroblasts and T cells with and without treatment of an exogenous stressor. Overall, our results suggest that the mechanism underlying the increased tumor predisposition in Prdx1-deficient mice may vary depending on tissue type.

Highlights.

Significant elevation in ROS levels in Prdx1−/− T cells and ear fibroblasts

Reduced Prdx1 peroxidase activity in fibroblasts compared to T cells

Significant elevation in LOH mutant frequency only in Prdx1 deficient fibroblasts

Significant reduction in Mlh1 expression in Prdx1−/− fibroblasts

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Jennifer Schulte for performing the Prdx1 western blot analyses. This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health [grant numbers ES011633, P30ES05022].

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Yoshizumi M, Tsuchiya K, Tamaki T. Signal transduction of reactive oxygen species and mitogen-activated protein kinases in cardiovascular disease. J. Med. Inv. 2001;48:11–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Claiborne A, Yeh JI, Mallett TC, Luba J, Crane EJ, Charrier V, Parsonage D. Protein-sulfenic acids: diverse roles for an unlikely player in enzyme catalysis and redox regulation. Biochem. 1999;38:15407–15416. doi: 10.1021/bi992025k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Neumann CA, Cao J, Manevich Y. Peroxiredoxin 1 and its role in cell signaling. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:4072–4078. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.24.10242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cadet J, Berger M, Douki T, Ravanat JL. Oxidative damage to DNA: formation, measurement, and biological significance. Rev. Phys. Biochem. Pharm. 1997;131:1–87. doi: 10.1007/3-540-61992-5_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Díaz-Llera S, Podlutsky A, Osterholm AM, Hou SM, Lambert B. Hydrogen peroxide induced mutations at the HPRT locus in primary human T-lymphocytes. Mut. Res. 2000;469:51–61. doi: 10.1016/s1383-5718(00)00058-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Neumann CA, Krause DS, Carman CV, Das S, Dubey DP, Abraham JL, Bronson RT, Fujiwara Y, Orkin SH, Van Etten RA. Essential role for the peroxiredoxin Prdx1 in erythrocyte antioxidant defence and tumour suppression. Nature. 2003;424:561–565. doi: 10.1038/nature01819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Egler RA, Fernandes E, Rothermund K, Sereika S, de Souza-Pinto N, Jaruga P, Dizdaroglu M, Prochownik EV. Regulation of reactive oxygen species, DNA damage, and c-Myc function by peroxiredoxin 1. Oncogene. 2005;24:8038–8050. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Turker MS, Gage BM, Rose JA, Elroy D, Ponomareva ON, Stambrook PJ, Tischfield JA. A novel signature mutation for oxidative damage resembles a mutational pattern found commonly in human cancers. Cancer Res. 1999;59:1837–1839. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Turner DR, Dreimanis M, Holt D, Firgaira FA, Morley AA. Mitotic recombination is an important mutational event following oxidative damage. Mut. Res. 2003;522:21–26. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(02)00194-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Knudson AG. Mutation and cancer: statistical study of retinoblastoma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1971;68:820–823. doi: 10.1073/pnas.68.4.820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shao C, Deng L, Henegariu O, Liang L, Raikwar N, Sahota A, Stambrook PJ, Tischfield JA. Mitotic recombination produces the majority of recessive fibroblast variants in heterozygous mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1999;96:9230–9235. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.16.9230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shao C, Deng L, Chen Y, Kucherlapati R, Stambrook PJ, Tischfield JA. Mlh1 mediates tissue-specific regulation of mitotic recombination. Oncogene. 2004;23:9017–9024. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shao C, Deng L, Henegariu O, Liang L, Stambrook PJ, Tischfield JA. Chromosome instability contributes to loss of heterozygosity in mice lacking p53. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2000;97:7405–7410. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.13.7405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meng Q, Skopek TR, Walker DM, Hurley-Leslie S, Chen T, Zimmer DM, Walker VE. Culture and propagation of Hprt mutant T-lymphocytes isolated from mouse spleen. Env. Mol. Mut. 1998;32:236–243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yuan L, Inoue S, Saito Y, Nakajima O. An evaluation of the effects of cytokines on intracellular oxidative production in normal neutrophils by flow cytometry. Exp. Cell. Res. 1993;209:375–381. doi: 10.1006/excr.1993.1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huo YY, Li G, Duan RF, Gou Q, Fu CL, Hu YC, Song BQ, Yang ZH, Wu DC, Zhou PK. PTEN deletion leads to deregulation of antioxidants and increased oxidative damage in mouse embryonic fibroblasts. Free Rad. Bio. Med. 2008;44:1578–1591. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cao J, Schulte J, Knight A, Leslie NR, Zagozdzon A, Bronson R, Manevich Y, Beeson C, Neumann CA. Prdx1 inhibits tumorigenesis via regulating PTEN/AKT activity. EMBO J. 2009;28:1505–1517. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shen WH, Balajee AS, Wang J, Wu H, Eng C, Pandolfi PP, Yin Y. Essential role for nuclear PTEN in maintaining chromosomal integrity. Cell. 2007;128:157–170. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.11.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frankenberg-Schwager M, Becker M, Garg I, Pralle E, Wolf H, Frankenberg D. The role of non-homologous DNA end joining, conservative homologous recombination, and single-strand annealing in the cell cycle-dependent repair of DNA double-strand breaks induced by H2O2 in mammalian cells. Rad. Res. 2008;170:784–793. doi: 10.1667/RR1375.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harfe BD, Jinks-Robertson S. DNA mismatch repair and genetic instability. Ann. Rev. Gen. 2000;34:359–399. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.34.1.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jiricny J. The multifaceted mismatch-repair system. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Bio. 2006;7:335–346. doi: 10.1038/nrm1907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Herman JG, Umar A, Polyak K, Graff JR, Ahuja N, Issa JP, Markowitz S, Willson JK, Hamilton SR, Kinzler KW, Kane MF, Kolodner RD, Vogelstein B, Kunkel TA, Baylin SB. Incidence and functional consequences of hMLH1 promoter hypermethylation in colorectal carcinoma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1998;95:6870–6875. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.12.6870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kane MF, Loda M, Gaida GM, Lipman J, Mishra R, Goldman H, Jessup JM, Kolodner R. Methylation of the hMLH1 promoter correlates with lack of expression of hMLH1 in sporadic colon tumors and mismatch repair-defective human tumor cell lines. Cancer Res. 1997;57:808–811. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brenner C, Deplus R, Didelot C, Loriot A, Viré E, De Smet C, Gutierrez A, Danovi D, Bernard D, Boon T, Pelicci PG, Amati B, Kouzarides T, de Launoit Y, Di Croce L, Fuks F. Myc represses transcription through recruitment of DNA methyltransferase corepressor. EMBO J. 2005;24:336–346. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gartel AL. A new mode of transcriptional repression by c-myc: methylation. Oncogene. 2006;25:1989–1990. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Felsher DW, Bishop JM. Transient excess of MYC activity can elicit genomic instability and tumorigenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1999;96:3940–3944. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.7.3940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jeong W, Park SJ, Chang TS, Lee DY, Rhee SG. Molecular mechanism of the reduction of cysteine sulfinic acid of peroxiredoxin to cysteine by mammalian sulfiredoxin. J. Bio. Chem. 2006;277:14400–14407. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511082200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wood ZA, Schröder E, Robin Harris J, Poole LB. Structure, mechanism and regulation of peroxiredoxins. Trends Bio. Sci. 2003;28:32–40. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(02)00003-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang KS, Kang SW, Woo HA, Hwang SC, Chae HZ, Kim K, Rhee SG. Inactivation of human peroxiredoxin I during catalysis as the result of the oxidation of the catalytic site cysteine to cysteine-sulfinic acid. J Bio. Chem. 2002;277:38029–38036. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206626200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marinkovic D, Marinkovic T, Kokai E, Barth T, Möller P, Wirth T. Identification of novel Myc target genes with a potential role in lymphomagenesis. Nuc. Acids Res. 2004;32:5368–5378. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]