Abstract

The current study utilized regression analyses to explore the relationships among demographic and linguistic indicators of acculturation, gender, and tobacco dependence among Spanish-speaking Latino smokers in treatment. Additionally, bootstrapping analyses were used to examine the role of dependence as a mediator of the relationship between indicators of acculturation and cessation. Indicators of time spent in the United States were related to indicators of physical dependence. Preferred media was related to a multidimensional measure of dependence. Gender did not impact the relationships between acculturation indicators and dependence. A multidimensional measure of dependence significantly mediated the relationship between preferred media language and cessation. Future research would benefit from consideration of acculturation and multidimensional measures of dependence when studying smoking cessation among Latinos, and from further examination of factors accounting for relationships among acculturation, dependence, and cessation.

Keywords: acculturation, tobacco dependence, Latinos, smoking cessation

1.0 Introduction

The adverse public health consequences of smoking among Latinos are severe, as three of the four leading causes of death among Latinos are smoking-related (i.e., cancer, heart disease, and stroke; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2009). Further, lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related deaths among Latino men, and the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths among Latina women (American Cancer Society, 2009). Coupled with the fact that Latinos are the fastest growing racial/ethnic group in the United States (U.S.; United States Census Bureau, 2007), developing a better understanding of the determinants of tobacco dependence and cessation is vital to the prevention of smoking-related chronic disease in this population.

Although there is considerable within-group variability (Howe, Wu, Ries et al., 2006), Latinos as a group have among the lowest smoking prevalence rates of all racial/ethnic groups in the U.S. (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2008). Additionally, Latino smokers tend to score lower on traditional indicators of tobacco dependence. Latinos are more likely to be non-daily smokers (Ackerson & Viswanath, 2009; Hyland, Rezaishiraz, Bauer et al., 2005; Trinidad, Pérez-Stable, Emery et al., 2009; Wortley, Husten, Trosclair et al., 2003; Zhu, Pulvers, Zhuang et al., 2007), they smoke fewer cigarettes per day (Bock, Niaura, Neighbors et al., 2005; Daza, Cofta-Woerpel, Mazas et al., 2006; Levinson, Perez-Stable, Espinoza et al., 2004; Trinidad et al., 2009), and they wait longer after waking before smoking (Daza et al., 2006) compared to non-Latino smokers. Despite their very different smoking patterns, very few randomized clinical trials of smoking cessation treatments have specifically targeted Latinos, and the few in existence demonstrate only modest overall effectiveness, with attenuating effects over time (Webb, Rodriguez-Esquivel, & Baker, 2010). A major impediment to advancing treatment efficacy among Latinos is that little is known about the processes underlying smoking cessation in this population (Fiore, Bailey, Cohen et al., 2000; Fiore, Jaén, Baker et al., 2008). Particularly understudied are the relationships between culturally relevant variables and critical determinants of smoking cessation such as tobacco dependence. The current study sought to address this gap by exploring the relationships among common indicators of acculturation, gender, tobacco dependence, and cessation among Spanish-speaking Latino smokers attempting to quit.

Acculturation refers to the behavioral and ideological changes experienced by individuals as a result of contact between two cultures (Berry, 1998, 2005), and includes an immigrant or minority individual’s adoption of U.S. customs, values, and identification with U.S. culture. Within Berry’s (2005) model of acculturation, most cultural adaptations resulting from the acculturative process, which Berry termed behavioral shifts, take place with little or no difficulty. When problematic acculturative issues arise that cannot be easily or quickly managed through behavioral shifts, this can result in a stress reaction, which Berry terms acculturative stress.

The adaptations an acculturating individual makes, or the coping response the individual has to acculturative stressors, may have implications for the relationship between acculturation and tobacco dependence. For example, studies have shown that more highly acculturated Latino smokers score higher on indicators of physical dependence compared to their lower acculturated counterparts (Marín, Pérez-Stable, & Marín, 1989; Palinkas, Pierce, Rosbrook et al., 1993) Palinkas and colleagues found that English-speaking Latino smokers were more likely to be heavy smokers (> 15 cigarettes per day) compared to Spanish-speaking Latino smokers (Palinkas et al., 1993). Marín and colleagues found that Latino smokers of high acculturative status (determined by dichotomizing scores on a short acculturation scale) smoked more cigarettes per day and waited less time before smoking their first cigarette of the day compared to their less acculturated counterparts (Marín et al., 1989). Within Berry’s model, these increases in smoking severity with greater acculturation might be interpreted as a behavioral shift in response to exposure to different cultural norms regarding smoking.

Consistent with Berry’s conceptualization of acculturative stress, associations between stressful experiences and acculturation are common among Latinos, although the direction of the association appears to differ according to the type of stressor. For example, higher acculturation is related to greater family conflict (Moyerman & Forman, 1992) but lower depressive symptomatology (Black, Markides, & Miller, 1998; Gallagher-Thompson, Tazeau, Basilio et al., 1997; Gonzalez, Haan, & Hinton, 2001; Gonzalez & Gonzalez, 2008; Masten, Penland, & Nayani, 1994; Torres & Rollock, 2007; Zamanian, Thackrey, Starrett et al., 1992). To the extent that acculturation influences important social/interpersonal factors that may be sources of stress, dependence on smoking may serve as coping mechanism among Latino smokers. Indeed, ample research and a prominent social-cognitive model of addiction highlight the major role of dependence and negative emotions in drug relapse (see Witkiewitz & Marlatt, 2004 for a review). Further, consideration of both the acculturative stress model and social-cognitive model of addiction may help explain recent findings on the relationship between acculturation and smoking cessation among Latino smokers (Castro, Reitzel, Businelle et al., 2009). In a sample of Spanish-speaking Latino smokers in treatment, Castro, et al., found high acculturation as measured by several demographic indicators predicted higher smoking cessation rates. Similar findings were recently reported among African Americans (Hooper, Baker, de Ybarra et al., 2012). Thus, in the case of smoking cessation, stressors associated with being of lower acculturative status may lead a greater likelihood of relapse.

A limitation of the extant research on acculturation and tobacco dependence (Bock et al., 2005; Marín et al., 1989; Palinkas et al., 1993) is that tobacco dependence was assessed with single dimension indicators of physical dependence, such as the number of cigarettes consumed per day, and the amount of time lapsed after waking before smoking the first cigarette of the day. Indicators such as these have been critiqued (see Piper, Piasecki, Federman et al., 2004) for their assumption that dependence can be fully captured with a single dimension reflecting the physiological manifestation of the dependence-tolerance process (i.e., smoking heaviness). Also, cigarettes per day and other single-item indicators of dependence may be too narrow a measure of a complex construct, and thus not adequately capture other non-physical aspects of dependence (e.g., cognitive and contextual variables; Piper et al., 2004).

For Latino smokers in particular, measures of cigarette consumption may suffer from floor effects, because Latinos tend to be low-level smokers (Trinidad et al., 2009; Zhu et al., 2007). Also, indicators of physical dependence are not consistent predictors of cessation among Latino smokers (Bock et al., 2005; Perez-Stable, Sabogal, Marin et al., 1991; Reitzel, Costello, Mazas et al., 2009; Woodruff, Talavera, & Elder, 2002). Thus, physical dependence indicators might be limited in their utility among Latino smokers. However, it is possible that dependence on smoking may be better captured through non-physical aspects of tobacco dependence, but this possibility has not been previously examined. Also, the influence of acculturative variables on non-physical aspects of dependence has not been examined.

To address the limitations of unidimensional indicators of physical dependence, multidimensional measures of tobacco dependence have emerged in recent years (e.g., Etter, Le Houezec, & Perneger, 2003; Piper et al., 2004; Shiffman, Waters, & Hickcox, 2004). For example, Piper and colleagues developed the Wisconsin Inventory of Smoking Dependence Motives (WISDM; Piper, Bolt, Kim et al., 2008; Piper et al., 2004), a theoretically informed measure of 13 motives that represent underlying mechanisms of dependence. Thus, it purports to improve upon unidimensional indicators of physical dependence with a multidimensional approach to assessing dependence that incorporates physical (e.g., tolerance, craving) and non-physical (e.g., affiliative attachment, automaticity) aspects of smoking.

Acculturation is also a multidimensional construct, consisting of factors relevant to language, behaviors, knowledge, attitudes/beliefs, and identity (Cabassa, 2003; Kim & Abreu, 2001; Kim, Laroche, & Tomiuk, 2001; Schwartz & Zamboanga, 2008; Unger, Ritt-Olson, Wagner et al., 2007). However, acculturation is often measured by a single factor, such as language fluency or nativity, that is assumed to represent overall acculturation (Guilamo-Ramos, Jaccard, & Turrisi, 2004; Thomson & Hoffman-Goetz, 2009; Unger et al., 2007). The limitations of such proxy measures have been detailed (Abraido-Lanza, Armbrister, Florez et al., 2006; Cabassa, 2003; Lara, Gamboa, Kahramanian et al., 2005; Nguyen & Meese, 1999; Unger et al., 2007), including that use of a single indicator of acculturation neglects the multidimensional nature of acculturation, thus limiting examination of how different aspects of acculturation might affect the same variable of interest differently. One way to address this issue when faced with single dimension proxies is to examine multiple indicators of acculturation. For example, use of indicators such as length of time in the U.S. may be a useful proxy for the amount of one’s exposure to (and thus, familiarity with) mainstream societal practices. In contrast, indicators of language use may be a useful proxy for level of mainstream societal engagement (as opposed to mere familiarity), and language preference may be a proxy for identification (as opposed to mere engagement) with mainstream U.S. practices.

The current study sought to examine the relationship between multiple acculturation indicators and tobacco dependence among a sample of Spanish-speaking Latino smokers seeking cessation counseling. Both unidimensional and multidimensional measures of dependence were examined for relationships with gender and several indicators of acculturation. Consistent with previous research, and the conceptualization of increased smoking behavior as a behavioral shift, positive relationships between acculturation indicators and physical dependence indicators were expected. Relationships between acculturation indicators and a multidimensional measure of tobacco dependence, which includes non-physical aspects of dependence, were also examined. In line with the argument that stress associated with being of lower acculturative status may lead to greater dependence on tobacco, acculturation indicators and non-physical aspects of dependence were expected to be inversely related. Finally, mediation analysis was conducted examining tobacco dependence as a potential explanatory mechanism for the relationship between preferred media language and cessation found in previous work (Castro et al., 2009). Given an increased likelihood of cessation with increased acculturation, and that tobacco dependence decreases the likelihood of cessation (Kozlowski, Porter, Orleans et al., 1994; Piper, McCarthy, Bolt et al., 2008), it was predicted that greater preference for English-language media would be inversely associated with dependence, and lower dependence would in turn be positively associated with cessation. Finally, because previous research demonstrates an important moderating effect of gender on smoking prevalence (Bethel & Schenker, 2005) and cessation (Castro et al., 2009), the moderating effect of gender was examined.

2.0 Methods and Materials

2.1 Participants

The current study utilized data from a two-group randomized clinical trial that evaluated the efficacy of a culturally sensitive, proactive, behavioral treatment program for Spanish-speaking Latino smokers (detailed information about the clinical trial can be found in Wetter, Mazas, Daza et al., 2007). Eligibility criteria included 1) self-identification as a smoker; 2) calling the National Cancer Institute’s Cancer Information Service (CIS; 1-800-4-CANCER) to request smoking cessation help in Spanish; 3) currently living in Texas, and; 4) at least 18 of age. Participants were recruited from several locations in Texas (e.g., Houston, San Antonio, El Paso, and the Rio Grande Valley) via paid media (television, radio, newspaper, and direct mailings).

Participants were enrolled from August 2002 to March 2004. There were 355 callers during the study period. Of the 355 callers, 297 consented to participate and were enrolled (84% participation rate). Of the 58 callers who did not participate, 28 declined, 3 were ineligible, 19 were unreachable, and 8 did not complete the baseline assessment.

2.2 Procedure

Callers who agreed to participate in the study were contacted by project staff within one week of their initial call to the CIS to complete a verbal, audiotaped informed consent and a baseline assessment. Participants were randomly assigned to receive one of two telephone-based counseling protocols as part of the clinical trial. Results of the clinical trial are available elsewhere (Wetter et al., 2007). With the exception of abstinence status, all variables examined in the current study were collected at the baseline assessment.

2.3 Measures and Variables of Interest

Abstinence

Smoking abstinence was defined as a self-report of not smoking during the previous 7 days at 12 weeks after the baseline assessment. “Abstinent” was coded “1” and “not abstinent” was coded “0”.

Acculturation indicators

Three indicators of acculturation that measure residence in the U.S. were used in the current study. Number of years in the U.S. was computed as the participant’s current age minus age of entry into the U.S. For individuals who were non-immigrants, age was used as the indicator of number of years in the U.S. Proportion of life spent in the U.S. was computed by dividing number of years spent in the U.S. by the individual’s age. Nativity, that is, whether the individual was an immigrant to the U.S. or U.S.-born, was also examined. Indicators of duration of residence in the U.S. are argued to be proxies for aspects of acculturation relevant to the amount of exposure to opportunities for cultural learning and adaptation (Thomson & Hoffman-Goetz, 2009). Number of years in the U.S. and proportion of life spent in the U.S. were continuous variables, whereas nativity was a dichotomous variable with ‘non-immigrant” coded “1” and ‘immigrant” coded “0”. Three indicators of acculturation related to language were also used in the current study: language spoken at home, language spoken at work, and preferred media language (i.e., the extent to which participants watched news and programs in English or Spanish). All language questions were rated on a five point scale. However, these five categories were collapsed into three categories because there were too few participants in some categories to make meaningful comparisons. The three categories were: “mostly/only Spanish,” “both with the same frequency,” and “mostly/only English.” Indicators of language use are argued to be proxies for functional or necessity-based cultural adaptation, whereas indicators of language preference may be proxies for cultural engagement or identification (Castro et al., 2009; Thomson & Hoffman-Goetz, 2009).

Demographics

Demographic variables included gender (male or female), partner status (partner or no partner), age, number of years of completed education, and annual household income.

Physical dependence

The number of cigarettes smoked per day and the amount of time lapsed after waking before smoking the first cigarette of the day were used as indicators of physical dependence. Time to first cigarette was coded as a dichotomous variable where “5 minutes or less” was coded “1” and “6 minutes or more” was coded “0.” The total score of the Fagerström Test of Nicotine Dependence (FTND; Heatherton, Kozlowski, Frecker et al., 1991) was also examined as an indicator of physical dependence. This is an 6-item scale designed to measure dependence on nicotine, and has been found to be significantly related to biochemical markers of dependence as well as abstinence.

Wisconsin Inventory of Smoking Dependence Motives (WISDM; Piper, Bolt et al., 2008; Piper et al., 2004)

The WISDM is a 68-item inventory designed to assess the motivational domains that underlie tobacco dependence. Participants are asked to rate each item on a scale of 1 (“not at all true of me”) to 7 (“extremely true of me”). The WISDM consists of 13 subscales and a total score. The 13 subscales are organized into two overarching factors: Primary Dependence Motives (PDM: comprised of Automaticity, Loss of Control, Craving, and Tolerance) and Secondary Dependence Motives (SDM; comprised of Affiliative Attachment, Behavioral Choice/Melioration, Cognitive Enhancement, Cue Exposure/Associative Processes, Negative Reinforcement, Positive Reinforcement, Social/Environment Goads, Taste/Sensory Properties, and Weight Control). Piper et al. (2008) found that elevated PDM scores constitute a “necessary and sufficient” measure of dependence and are highly predictive of smoking cessation, while the SDM factor has less predictive utility.

2.4 Data analysis

A series of regressions were conducted to examine the main effects of gender and each acculturation indicator on number of cigarettes per day, time to first cigarette of the day, FTND, the individual WISDM subscales, the PDM and SDM factors of the WISDM, and the total WISDM score. Logistic regressions were conducted where time to first cigarette of the day was the dependent variable. All other dependence measures were continuous, thus linear regressions were conducted for these outcome variables. Analyses were adjusted for age, education, income, and partner status in order to isolate the effects of gender and acculturation indicators over commonly reported demographic influences. These covariates were entered in step 1 of each regression, and the main effects of gender and a specific acculturation indicator were entered in step 2. The interaction of gender with each acculturation indicator was also examined for each dependence indicator and was entered in step 3. Each combination of acculturation and dependence indicator was examined in a separate regression analysis.

Previous research (Castro et al., 2009; Hooper et al., 2012) identified a significant relationship such that greater levels of acculturation resulted in an increased likelihood of smoking cessation. Since lower dependence is also negatively associated with smoking cessation, acculturation indicators should be negatively associated with dependence in order for dependence to be a mediator of the relationship between acculturation and cessation. Thus, for the analyses that revealed logical relationships between dependence and acculturation indicators, dependence was examined as a potential mediator of the relation between that acculturation indicator and cessation. A bias-corrected bootstrapping procedure with 5,000 resamples was used to test indirect effects (Preacher & Hayes, 2008). This method is preferred over the traditional “causal steps” approach to examining mediation, as the causal steps approach is considered highly conservative and does not allow for overt statistical examination of the mediation effect, whereas the method used here provides a statistical estimate and significance test of the size of the actual indirect effect (Preacher & Hayes, 2008). Mediation analyses were additionally adjusted for gender and treatment group. All analyses were conducted using a sample of 297 individuals, where those with missing data were removed on a case-wise basis for a final sample of 287. Due to the exploratory nature of this study, no correction for multiple analyses was utilized.

3.0 Results

3.1 Participant characteristics

Participant characteristics by gender are presented in Table 1. Only one significant difference was found between men and women, with women more likely to have a household income of less than $20,000 (p = .014). The ancestry or region of origin for the sample was as follows: 198 (66.7%) Mexican, 47 (15.8%) Central American, 36 (12.1%) South American, 10 (3.4%) Cuban, 3 (1.0%) Spaniard, 1 (0.3%) Puerto Rican, and 2 (0.7%) “other”.

Table 1. Participant Characteristics by Gender.

| Women N=133 |

Men N=164 |

|

|---|---|---|

|

|

||

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |

|

|

||

| Age | 42.11 (10.9) | 40.37 (11.77) |

| Years of education | 10.8 (4.06) | 10.91 (3.98) |

| Number of cigarettes per day | 10.31 (8.63) | 10.36 (8.18) |

| Years in U.S. | 16.07 (12.21) | 15.36 (13.51) |

| Proportion of life in U.S. | 36.78 (24.2) | 35.78 (25.85) |

|

|

||

| N (%) | N (%) | |

|

|

||

| Yearly household income | ||

| Less than $20,000 | 82 (63.6) | 79 (49.1) |

| $20,000 or more | 47 (36.4) | 82 (50.9) |

| Partner status | ||

| Have partner | 41 (31.1) | 55 (33.5) |

| No partner | 91 (68.9) | 109 (66.5) |

| Time to first cigarette | ||

| 5 minutes or less | 24 (18.3) | 21 (13.4) |

| 6 minutes or more | 107 (81.7) | 136 (86.6) |

| Immigrant status | ||

| Immigrant | 126 (94.7) | 151 (93.2) |

| Non-immigrant | 7 (5.3) | 11 (6.8) |

| Language used at home | ||

| Only/mostly Spanish | 117 (88.0) | 151 (92.1) |

| Both equally | 8 (6.0) | 10 (6.1) |

| Only/mostly English | 8 (6.0) | 3 (1.8) |

| Language used at work | ||

| Only/mostly Spanish | 49 (65.3) | 94 (64.4) |

| Both equally | 10 (13.3) | 22 (15.1) |

| Only/mostly English | 16 (21.3) | 30 (20.5) |

| Preferred media language | ||

| Only/mostly Spanish | 96 (72.7) | 103 (63.2) |

| Both equally | 27 (20.5) | 38 (23.3) |

| Only/mostly English | 9 (6.8) | 22 (13.5) |

Note. Bold indicates significant difference, p < .05. One participant did not report age. Number of years in the U.S. and proportion of life in the U.S. could not be computed for 10 participants. Seven participants did not report income, one did not report marital status, nine did not report time to first cigarette, two did not report immigrant status, 76 did not report language spoken at work or this item was not applicable, and two did not report preferred media language.

3.2 Relationships among gender, acculturation indicators and physical dependence

Linear and logistic regression analyses were used to examine the effects of gender and acculturation indicators on FTND, number of cigarettes consumed per day, and time to first cigarette of the day. Results indicated no significant main effect of gender on any physical dependence indicator (results not shown). Additionally, there were no significant main effects of nativity or any language acculturation indicator on any physical dependence indicator (results not shown). However, analyses revealed a significant main effect of years in the U.S. and proportion of life in the U.S. on three indicators of physical dependence. Years in the U.S. was positively associated with number of cigarettes per day (t [281] =2.01, β = .14, p = .045). Proportion of life spent in the U.S. was positively associated with number of cigarettes per day (t [281] = 2.23, β = .14, p = .03) and time to first cigarette (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] = 1.02, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.001-1.03, p = .03). There were no significant interactions of gender with any of the acculturation indicators predicting the physical dependence indicators (results not shown).

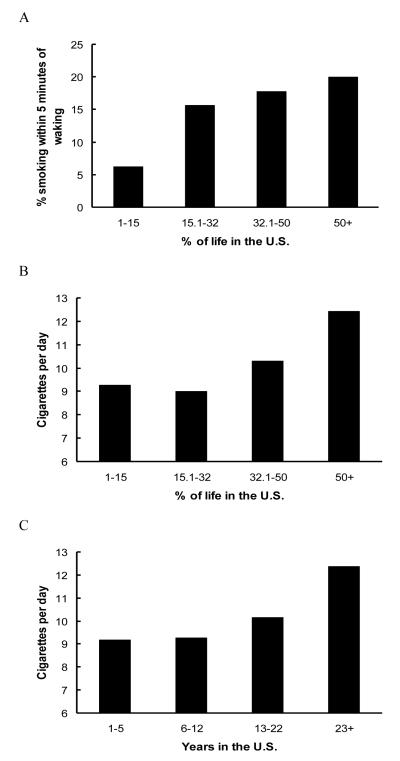

To visually depict the significant main effects, participants were divided into roughly equal quartiles of years in the U.S. and proportion of life in the U.S. Number of cigarettes per day and proportion of individuals smoking their first cigarette within five minutes of waking were calculated for each quartile. As depicted in Figure 1, cigarettes per day and proportion of individuals smoking their first cigarette within five minutes of waking increased with greater proportion of life in the U.S. Similarly, an increase in cigarettes per day was associated with spending more years in the U.S.

Figure 1.

(A, B, and C) Relationships between indicators of physical dependence and indicators of time spent in the U.S.

3.3 Relationships among gender, acculturation indicators and WISDM scores

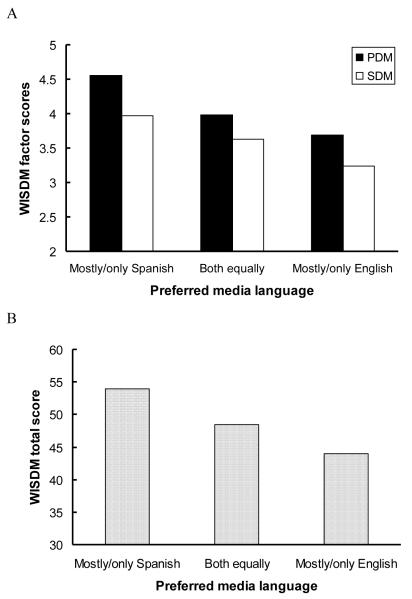

As shown in Table 2, gender was significantly associated with only two WISDM subscales. Women scored higher on Positive Reinforcement, whereas men scored higher on Social/Environmental Goads. Analyses of effect of years in the U.S., proportion of life in the U.S., nativity, language spoken at home, and language spoken at work on WISDM scales revealed no significant effects. Greater preference for English-language media was related to decreased scores on PDM, SDM, and the WISDM total score (Table 2). This association was also significant for three of the four scales that comprise PDM (Automaticity, Craving, and Loss of Control), and five of the nine scales that comprise SDM (Affiliative Attachment, Behavioral Choice, Cue Exposure/Associative Processes, Positive Reinforcement, and Negative Reinforcement).

Table 2. Main Effects of Preferred Media Language and Gender on WISDM Scales.

| WISDM Scale used as dependent variable | Main effect of preferred media language |

Main effect of gender | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||

| p-value | β | p-value | β | |

|

|

|

|||

| WISDM Primary Dependence | .002 | −.184 | .46 | −.044 |

| WISDM Secondary aDependence | .005 | −.170 | .36 | −.054 |

| WISDM total | .002 | −.183 | .37 | −.053 |

| WISDM Automaticity | .008 | −.162 | .48 | −.042 |

| WISDM Craving | .001 | −.20 | .99 | .001 |

| WISDM Loss of Control | .004 | −.175 | .16 | −.084 |

| WISDM Tolerance | .07 | −.11 | .66 | −.026 |

| WISDM Affiliative Attachment | .004 | −.172 | .09 | −.101 |

| WISDM Behavioral Choice/Melioration | <.001 | −.232 | .10 | −.097 |

| WISDM Cognitive Enhancement | .07 | −.111 | .99 | .000 |

| WISDM Cue Exposure/Associative Processes |

.03 | −.13 | .44 | −.046 |

| WISDM Negative Reinforcement | .02 | −.146 | .18 | −.080 |

| WISDM Positive Reinforcement | .02 | −.143 | .048 | −.118 |

| WISDM Social-environmental Goads | .53 | −.037 | .003 | .178 |

| WISDM Taste/Sensory Processes | .14 | −.090 | .19 | −.078 |

| WISDM Weight Control | .09 | −.104 | .38 | −.053 |

Note: WISDM= Wisconsin Inventory of Smoking Dependence Motives. Analyses are controlled for age, income, education, and partner status. Analyses of the main effect of preferred media also control for gender, and analyses of the main effect of gender also control for preferred media language.

Mean scores on the WISDM PDM, SDM, and total score for each level of preferred media language is depicted in Figure 2. Scores on the WISDM PDM, SDM, and total score decreased with increasing acculturation. No interaction effect of gender and acculturation indicators predicted WISDM scores.

Figure 2.

(A and B) Relationships between WISDM scores and media language preference.

3.4 Mediation of the acculturation-cessation relationship

Although time to first cigarette and number of cigarettes per day showed significant relationships with indicators of length of residence in the U.S., the relationships were in the direction that excludes these dependence indicators as potential mediators of the relationship between acculturation and cessation (i.e., physical dependence was positively related to acculturation indicators). Additionally, previous research found that these indicators did not predict cessation in this sample (Reitzel et al., 2009). Thus, time to first cigarette and number of cigarettes per day were not examined for mediation effects. However, PDM, SDM and the WISDM total score demonstrated relationships with preferred media language in the direction that would be expected if they serve as mediators of the relation between preference for English language media and smoking cessation (i.e., PDM, SDM and the total score were negatively related to language preference). Thus, mediation analyses examining the potential mediation effects of PDM and SDM on the relationship between preferred media language and abstinence were performed.

Castro et al. previously demonstrated in this sample that greater preference for English language media was related to greater likelihood of smoking abstinence (Castro et al., 2009). Here, the potential mediators, WISDM total score, PDM and SDM were examined for their relationship with abstinence in the current sample, controlling for demographics, gender, and treatment group. These results indicated that only PDM was a significant predictor of abstinence (AOR = .83, 95% CI = .69-.99; p = .04). SDM and WISDM total score did not predict abstinence (p = .31, and p = .15, respectively). Further, PDM remained a significant predictor of abstinence after accounting for SDM (AOR = .72, 95% CI = .52-.99; p = .04).

Next, simple and multiple mediation analyses were conducted to examine the potential mediating effects of PDM and SDM. Simple mediation analyses indicated that neither PDM nor SDM were significant mediators alone (PDM indirect effect = .07, 95% CI = −.001; .20; SDM indirect effect = −.04, 95% CI = −.04; .14). Results of the multiple mediation analysis indicated that PDM had a significant unique mediating effect on the relationship between preferred media language and abstinence (indirect effect = .13, 95% CI = .005; .36), but SDM did not (indirect effect = −.07, 95% CI = −.26; .04). Although the current mediation analyses were adjusted for gender, Castro et al. found a significant effect of acculturation on cessation only among men. Therefore, mediational analyses were repeated using only the male sample. This produced identical results.

4.0 Discussion

The relationship of acculturation indicators and tobacco dependence is complex, with the direction of the association being dependent on the type of indicators of both acculturation and dependence. For example, greater acculturation as indicated by of length of residence in the U.S. was positively related to unidimensional indicators of physical dependence (i.e., number of cigarettes smoked per day and smoking within five minutes of waking). Conversely, a preference for English language media, was related to lower dependence when using a multidimensional measure of dependence. As detailed below, it may be useful to interpret these contradictory findings within the context of Berry’s (2005) model of acculturative stress, by which changes in physical dependence might be seen as behavioral shifts, whereas changes in psychological dependence may be influenced by acculturative stress. Relationships between acculturation indicators and dependence did not differ by gender, and gender had a very minimal influence on dependence indicators (i.e., men and women differed only on two WISDM subscales). A mediational model indicated that WISDM primary dependence was a significant mediator of the relationship between preferred media language and abstinence. That is, a preference for English language media predicted lower dependence that was, in turn, associated with greater success at cessation.

Consistent with previous research (Marín et al., 1989; Palinkas et al., 1993) the current study found that greater duration of exposure to U.S. society and culture (as measured by years spent in the U.S. and proportion of life spent in the U.S.) were significantly associated with increases in cigarettes per day and with increased likelihood of smoking one’s first cigarette within five minutes of waking. However, these unidimensional indicators of physical dependence were not predictive of, also consistent with previous research among Latinos (Bock et al., 2005; Perez-Stable et al., 1991; Woodruff et al., 2002). Interpreted within Berry’s model of cultural adaptation, increases in cigarette consumption and time to first cigarette may represent an acculturative behavioral shift associated with dominant culture exposure, but not necessarily an increase in tobacco dependence more broadly defined. That being said, on area fruitful area of future research in this area may be in regards to understanding how the characteristics of the acculturating individual’s environment (e.g., living in an ethnic enclave, versus not, proportion of Latinos or Spanish-only speakers in one’s neighborhood) may interact with time of residency in the U.S., and length of residency in a particular neighborhood, to influence behavioral shifts like smoking behavior.

Additionally, although significant positive relationships were found between indicators of time in the U.S. and physical dependence, it should be noted that even among those individuals with the greatest time in the U.S., the daily smoking rate was about 12 cigarettes, and less than 20% smoked their first cigarette within five minutes of waking. Thus, even the heaviest Latino smokers in this sample were relatively low level smokers. Coupled with previous findings regarding the lack of predictive utility of physical dependence indicators among Latinos with regards to abstinence (Bock et al., 2005; Perez-Stable et al., 1991; Reitzel et al., 2009; Woodruff et al., 2002) these results suggest that indicators of physical dependence alone may not be an appropriate method for inferring tobacco dependence more broadly among Latino smokers.

In contrast, scores on a multidimensional, motives-based measure of dependence generally decreased with increasing preference for English language media. Three of the four scales that comprise PDM (Craving, Automaticity and Loss of Control) and five of the nine scales that comprise SDM (Affiliative Attachment, Behavioral Choice, Cue Exposure, Positive Reinforcement, Negative Reinforcement) were negatively associated with language preference. These findings are consistent with Castro et al.’s (2009) findings that more highly acculturated Latino smokers had higher cessation rates than their lower-acculturated counterparts. Interpreted within Berry’s (2005) conceptualization of acculturative stress, stressors may decline with higher levels of cultural engagement or identification (as measured by language preference), and that may reduce dependence on tobacco. Consistent with explanation, mediation analysis found that media language preference had an indirect effect on cessation through primary dependence motives.

This is among the first explanatory models of cultural influences on smoking cessation among Latinos. However, it raises additional questions, such as, why Latino smokers with greater preference for English experience less dependence? One possibility is that more acculturated Latinos may have access to more psychological resources (e.g., social support) that help them to manifest less dependence on smoking, and these factors together may contribute to successful cessation. Alternatively, greater acculturation is associated with fewer depressive symptoms (Black et al., 1998; Gallagher-Thompson et al., 1997; Masten et al., 1994; Torres & Rollock, 2007; Zamanian et al., 1992), English-language speaking pressures, and pressure toward acculturation (Schwartz & Zamboanga, 2008). The lessening of these pressures may lead to less dependence on smoking. Although current findings can be interpreted consistent with the acculturative stress model, the current study is limited in that measures of acculturative stress were not available to directly test the acculturative stress model. Thus, future research would benefit from expansion of the mediational model tested here to include acculturative stress, as well as other social and intrapersonal influences on cessation.

Conclusions regarding the current mediation analyses are tempered by the fact that no acculturation indicator other than media preference was significantly related to the multidimensional measure of tobacco dependence. Thus, this result could be a chance finding. However, given that the direction of the relationship was consistent with predictions, and tobacco dependence was found to be a significant mediator of the relationship between language preference and cessation, this finding merits further study. More generally, the results suggest that a multidimensional, motives-based approach to measuring dependence might better capture dependence among Spanish-speaking smokers compared to unidimensional, physiologically-based measures. Use of a more comprehensive measure of dependence (that considers both physical and non-physical aspects) better predicts cessation among Latinos compared to single item indicators of physical dependence (e.g., cigarettes per day). Use of a multidimensional measure is encouraged in future research.

Gender had a minimal impact on dependence, and no interactions of gender and acculturation indicators predicted dependence. No differences emerged between men and women on indicators of physical dependence. Women scored higher on the WISDM Positive Reinforcement scale, and men scored higher on the WISDM Social/Environmental Goads scale. However, there were no differences between men and women on the two higher order factors of the WISDM or the WISDM total score. This suggests that the current inferences regarding acculturation and dependence apply similarly to men and women. However, given that acculturation affects major smoking outcomes (e.g., prevalence and cessation) differently for Latino men and women, the relevant mechanisms underlying such differential effects remain to be identified. Future research might continue to address this question by examining gender and acculturation as they relate to other mechanisms underlying smoking (e.g., self-efficacy, social support).

The current study has several limitations. The study was the first to examine the association of cultural variables with multiple dimensions of tobacco dependence. As such, there were a number of novel findings that require replication, particularly as no correction for multiple statistical tests was used. This study used demographic indicators of acculturation, rather than a comprehensive acculturation scale, and such proxies may less effectively tap into an individual’s level of adoption and internalization of mainstream practices, culture, and values. Just as the current study benefited from a multidimensional measure of dependence, research on acculturation among Latino smokers would benefit from use of a more comprehensive multidimensional measure of acculturation. This study examined self-report of abstinence and lacked biochemical verification. However one meta-analysis found that self-report of abstinence is nevertheless quite reliable, with sensitivity and specificity of 87.5% and 89.2%, respectively (Patrick, Cheadle, Thompson et al., 1994),and another review concluded that analyses of estimated misclassification of smoking status is generally small and rarely changes conclusions (Velicer, Prochaska, Rossi, et al., 1992). The relative homogeneity in acculturation level (low acculturated, Spanish-speaking smokers seeking counseling in Spanish) limits the generalizability of the findings. Similarly, current findings are limited to individuals who were interested in quitting smoking. Last, due to the small sample size of subgroups by country or region of ancestry, analyses examining Latino subgroups could not be done. Given known differences in the smoking prevalence rates of Latino subgroups, future research examining determinants of smoking should be particularly sensitive to the issue of generalizability across Latino subgroups.

5.0 Conclusions

In sum, the current study found that indicators of time in the U.S. were related to indicators of physical dependence, while an indicator of language preference was related to a multidimensional measure of dependence motives. The direction of these effects were different, with greater time in the U.S. associated with smoking more cigarettes per day and less time to the first cigarette of the day, and greater preference for English language media associated with less dependence on a multidimensional measure. Mediational analyses suggest dependence may be an important mechanism underlying the relationship between preferred media language and cessation. Future research is needed to replicate and further explicate these relationships.

Highlights.

Physiological dependence relates to time spent in the United States.

Psychological dependence relates to preference for English language media.

Acculturation may affect smoking cessation indirectly by affecting nicotine dependence.

Indicators of physical and non-physical dependence are differentially related to various facets of acculturation.

Multidimensional approaches to the measurement of both nicotine dependence and acculturation are necessary to understand what appears to be a complex relationship between these variables.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the Minority Health Research and Education Program of the Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board, the American Cancer Society (MRSGT-10-104-01-CPHPS), and the National Cancer Institute (K01 CA157689, K07 CA121037, two CURE Supplements to R25 CA57730). This research is supported in part by the National Institutes of Health through The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center’s Cancer Center Support Grant CA016672. This study was approved by The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center Institutional Review Board.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures

The authors do not have any conflicts of interest pertaining to this work.

References

- Abraido-Lanza AF, Armbrister AN, Florez KR, Aguirre AN. Toward a Theory-Driven Model of Acculturation in Public Health Research. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96(8):1342–1346. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.064980. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2005.064980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ackerson L, Viswanath K. Communication inequalities, social determinants, and intermittent smoking in the 2003 Health Information National Trends Survey. Preventing Chronic Disease. 2009;6(2):A40. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Cancer Society . Cancer Facts & Figures for Hispanics/Latinos 2009-2011. Atlanta, GA: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Berry JW. Acculturative stress. In: Organista PB, Chun KM, Marin G, editors. Readings in ethnic psychology. Taylor & Frances/Routledge; Florence, KY: 1998. pp. 117–122. [Google Scholar]

- Berry JW. Acculturation: Living successfully in two cultures; Int J Intercult Rel Special Issue: Conflict, negotiation, and mediation across cultures: Highlights from the fourth biennial conference of the International Academy for Intercultural Research; 2005; pp. 697–712. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2005.07.013. [Google Scholar]

- Bethel JW, Schenker MB. Acculturation and smoking patterns among Hispanics: A review. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2005;29:143–148. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black SA, Markides KS, Miller TQ. Correlates of depressive symptomatology among older community-dwelling Mexican Americans: the Hispanic EPESE. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 1998;53(4):S198–208. doi: 10.1093/geronb/53b.4.s198. doi: 10.1093/geronb/53B.4.S198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bock BC, Niaura RS, Neighbors CJ, Carmona-Barros R, Azam M. Differences between Latino and non-Latino White smokers in cognitive and behavioral characteristics relevant to smoking cessation. Addictive Behaviors. 2005;30(4):711–724. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.08.017. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabassa LJ. Measuring acculturation: Where we are and where we need to go. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2003;25(2):127–146. doi: 10.1177/0739986303025002001. [Google Scholar]

- Castro Y, Reitzel LR, Businelle MS, Kendzor DE, Mazas CA, Li Y, et al. Acculturation differentially predicts smoking cessation among Latino men and women. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 2009;18(12):3468–3475. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0450. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Cigarette Smoking Among Adults--United States, 2007. Morbity & Mortality Weekly Report. 2008;57(45):1221–1226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Vital Statistics System. Deaths, Percent of Total Deaths, and Death Rates for the 15 Leading Causes of Death in 5-year Age Groups, by Hispanic Origin, Race for Non-Hispanic Population and Sex: United States, 1999-2006. 2009 Nov 12; Retrieved February 17, 2010, from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/dvs/LCWK4_2006.pdf.

- Daza P, Cofta-Woerpel L, Mazas C, Fouladi RT, Cinciripini PM, Gritz ER, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in predictors of smoking cessation. Substance Use & Misuse. 2006;41(3):317–339. doi: 10.1080/10826080500410884. doi: 10.1080/10826080500410884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etter J-F, Le Houezec J, Perneger TV. A self-administered questionnaire to measure dependence on cigarettes: the cigarette dependence scale. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28(2):359–370. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300030. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiore MC, Bailey WC, Cohen SJ, Dorfman SF, Goldstein MG, Gritz ER, et al. Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: Clinical Practice Guideline. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Public Health Service; Rockville, MD: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Fiore MC, Jaén CR, Baker TB, Bailey WC, Benowitz NL, Curry SJ, et al. Clinical Practice Guideline. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Rockville, MD: 2008. Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: 2008 Update. [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher-Thompson D, Tazeau YN, Basilio L, Hansen H, Polich T, Menendez A, et al. The relationship of dimensions of acculturation to self-reported depression in older, Mexican-American women. Journal of Clinical Geropsychology. 1997;3(2):123–137. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez HM, Haan MN, Hinton L. Acculturation and the Prevalence of Depression in Older Mexican Americans: Baseline Results of the Sacramento Area Latino Study on Aging. Journal of the American Geriatics Society. 2001;49(7):948–953. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49186.x. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49186.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez P, Gonzalez GM. Acculturation, optimism, and relatively fewer depression symptoms among Mexican immigrants and Mexican Americans. Psychological Reports. 2008;103(2):566–576. doi: 10.2466/pr0.103.2.566-576. doi: 10.2466/PR0.103.6.566-576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorber SC, Schofield-Hurwitz S, Hardt J, Levasseur G, Tremblay M. The accuracy of self-reported smoking: A systematic review of the relationship between self-reported and cotinine-assessed smoking status. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2009;11(1):12–24. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntn010. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntn010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guilamo-Ramos V, Jaccard J, Johansson M, Turrisi R. Binge drinking among Latino youth: Role of acculturation-related variables. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2004;18:135–142. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.18.2.135. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.18.2.135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerstrom KO. The Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence: a revision of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire. British Journal of Addiction. 1991;86(9):1119–1127. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooper MSW, Baker EA, de Ybarra DR, McNutt M, Ahluwalia JS. Acculturation predicts 7-day smoking cessation among treatment-seeking African-Americans in a group intervention. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2012;43:74–83. doi: 10.1007/s12160-011-9304-y. doi: 10.1007/s12160-011-9304-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howe HL, Wu X, Ries LAG, Cokkinides V, Ahmed F, Jemal A, et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975-2003, featuring cancer among U.S. Hispanic/Latino populations. Cancer. 2006;107(8):1711–1742. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22193. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyland A, Rezaishiraz H, Bauer J, Giovino GA, Cummings KM. Characteristics of low-level smokers. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2005;7(3):461–468. doi: 10.1080/14622200500125369. doi: 10.1080/14622200500125369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim BSK, Abreu JM. Acculturation measurement: Theory, current instruments, and future directions. In: Ponterotto JG, Casas JM, Suzuki A, Alexander CM, editors. Handbook of multicultural counseling. Sage; Thousand Oaks: 2001. pp. 394–424. [Google Scholar]

- Kim C, Laroche M, Tomiuk MA. A measure of acculturation for Italian Canadians: Scale development and construct validation. Int J Intercult Rel. 2001;25(6):607–637. doi: 10.1016/S0147-1767%2801%2900028-1. [Google Scholar]

- Kozlowski LT, Porter CQ, Orleans CT, Pope MA, Heatherton T. Predicting smoking cessation with self-reported measures of nicotine dependence: FTQ, FTND, and HSI. Drug & Alcohol Dependence. 1994;34(3):211–216. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(94)90158-9. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(94)90158-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lara M, Gamboa C, Kahramanian MI, Morales LS, Bautista DEH. Acculturation and Latino health in the United States: a review of the literature and its sociopolitical context. Annu Rev Publ Health. 2005;26:367–397. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144615. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levinson AH, Perez-Stable EJ, Espinoza P, Flores ET, Byers TE. Latinos report less use of pharmaceutical aids when trying to quit smoking. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2004;26(2):105–111. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2003.10.012. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2003.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marín G, Pérez-Stable EJ, Marín BV. Cigarette smoking among San Francisco Hispanics: the role of acculturation and gender. American Journal of Public Health. 1989;79(2):196–198. doi: 10.2105/ajph.79.2.196. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.79.2.196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masten WG, Penland EA, Nayani EJ. Depression and acculturation in Mexican-American women. Psychological Reports. 1994;75(3, Pt 2):1499–1503. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1994.75.3f.1499. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1994.75.3f.1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyerman DR, Forman BD. Acculturation and adjustment: A meta-analytic study. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1992;14(2):163–200. doi: 10.1177/07399863920142001. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen HH, Meese LA, Stollak GE. Toward a more complex understanding of acculturation and adjustment. Journal of Cross Cultural Psychology. 1999;30:5–27. doi: 10.1177/0022022199030001001. [Google Scholar]

- Palinkas LA, Pierce J, Rosbrook BP, Pickwell S, Johnson M, Bal DG. Cigarette smoking behavior and beliefs of Hispanics in California. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 1993;9(6):331–337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick DL, Cheadle A, Thompson DC, Dieher P, Koepsell T, Kinne S. The validity of self-reported smoking: A review and meta-analysis. American Journal of Public Health. 1994;84(7):1086–1093. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.7.1086. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.84.7.1086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Stable EJ, Sabogal F, Marin G, Marin BV, Otero-Sabogal R. Evaluation of “Guia para Dejar de Fumar,” a self-help guide in Spanish to quit smoking. Public Health Rep. 1991;106(5):564–570. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piper ME, Bolt DM, Kim S-Y, Japuntich SJ, Smith SS, Niederdeppe J, et al. Refining the tobacco dependence phenotype using the Wisconsin Inventory of Smoking Dependence Motives. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2008;117(4):747–761. doi: 10.1037/a0013298. doi: 10.1037/a0013298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piper ME, McCarthy DE, Bolt DM, Smith SS, Lerman C, Benowitz N, et al. Assessing dimensions of nicotine dependence: An evaluation of the Nicotine Dependence Syndrome Scale (NDSS) and the Wisconsin Inventory of Smoking Dependence Motives (WISDM) Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2008;10(6):1009–1020. doi: 10.1080/14622200802097563. doi: 10.1080/14622200802097563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piper ME, Piasecki TM, Federman EB, Bolt DM, Smith SS, Fiore MC, et al. A multiple motives approach to tobacco dependence: the Wisconsin Inventory of Smoking Dependence Motives (WISDM-68) Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 2004;72(2):139–154. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.2.139. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.2.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavioral Research Methods. 2008;40(3):879–891. doi: 10.3758/brm.40.3.879. doi: 10.3758/BRM.40.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reitzel LR, Costello TJ, Mazas CA, Vidrine JI, Businelle MS, Kendzor DE, et al. Low-level smoking among Spanish-speaking Latino smokers: relationships with demographics, tobacco dependence, withdrawal, and cessation. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2009;11(2):178–184. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntn021. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntn021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Zamboanga BL. Testing Berry’s model of acculturation: A confirmatory latent class approach. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2008;14(4):275–285. doi: 10.1037/a0012818. doi: 10.1037/a0012818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Waters A, Hickcox M. The nicotine dependence syndrome scale: a multidimensional measure of nicotine dependence. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2004;6(2):327–348. doi: 10.1080/1462220042000202481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson MD, Hoffman-Goetz L. Defining and measuring acculturation: a systematic review of public health studies with Hispanic populations in the United States. Social Science & Medicine. 2009;69(7):983–991. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.05.011. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres L, Rollock D. Acculturation and depression among Hispanics: The moderating effect of intercultural competence. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2007;13(1):10–17. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.13.1.10. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.13.1.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trinidad DR, Pérez-Stable EJ, Emery SL, White MM, Grana RA, Messer KS. Intermittent and light daily smoking across racial/ethnic groups in the United States. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2009;11(2):203–210. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntn018. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntn018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unger JB, Ritt-Olson A, Wagner K, Soto D, Baezconde-Garbanati L. A comparison of acculturation measures among Hispanic/Latino adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2007;34(6):555–565. doi: 10.1007/s10964-007-9184-4. [Google Scholar]

- United States Census Bureau Minority Population Tops 100 Million. 2007 Retrieved February 17, 2010, from http://www.census.gov/Press-Release/www/releases/archives/population/010048.html.

- Velicer WF, Prochaska JO, Rossi JS, Snow MG. Assessing outcome in smoking cessation studies. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;111(1):23–41. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.111.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb MS, Rodriguez-Esquivel D, Baker EA. Smoking cessation interventions among Hispanics in the United States: A systematic review and mini meta-analysis. American Journal of Health Promotion. 2010;25(2):109–118. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.090123-LIT-25. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.090123-LIT-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wetter DW, Mazas C, Daza P, Nguyen L, Fouladi RT, Li Y, et al. Reaching and treating Spanish-speaking smokers through the National Cancer Institute’s Cancer Information Service. A randomized controlled trial. Cancer. 2007;109(2 Suppl):406–413. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22360. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witkiewitz K, Marlatt GA. Relapse prevention for alcohol and drug problems: that was Zen, this is Tao. American Psychologist. 2004;59(4):224–235. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.4.224. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.4.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodruff SI, Talavera GA, Elder JP. Evaluation of a culturally appropriate smoking cessation intervention for Latinos. Tobacco Control. 2002;11(4):361–367. doi: 10.1136/tc.11.4.361. doi: 10.1136/tc.11.4.361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wortley PM, Husten CG, Trosclair A, Chrismon J, Pederson LL. Nondaily smokers: a descriptive analysis. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2003;5(5):755–759. doi: 10.1080/1462220031000158753. doi: 10.1080/1462220031000158753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamanian K, Thackrey M, Starrett RA, Brown LG, Lassman DK, Blanchard A. Acculturation and depression in Mexican-American elderly. Clinical Gerontologist. 1992;11(3-4):109–121. doi: 10.1300/J018v11n03_08. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu S-H, Pulvers K, Zhuang Y, Baezconde-Garbanati L. Most Latino smokers in California are low-frequency smokers. Addiction. 2007;102(Suppl 2):104–111. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01961.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01961.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]