Abstract

This report reviews structurally related phospholipid oxidation products that are biologically active where molecular mechanisms have been defined. Phospholipids containing polyunsaturated fatty acyl residues are chemically or enzymatically oxidized to phospholipid hydroperoxides, which may fragment on either side of the newly introduced peroxy function to form phospholipids with a truncated sn-2 residue. These truncated phospholipids not subject to biologic control of their production and, depending on the sn-2 residue length and structure, can stimulate the plasma membrane receptor for PAF. Alternatively, these chemically formed products can be internalized by a transport system to either stimulate the lipid activated nuclear transcription factor PPARγ or at higher levels interact with mitochondria to initiate the intrinsic apoptotic cascade. Intracellular PAF acetylhydrolases specifically hydrolyze truncated phospholipids, and not undamaged, biosynthetic phospholipids, to protect cells from oxidative death. Truncated phospholipids are also formed within cells where they couple cytokine stimulation to mitochondrial damage and apoptosis. The relevance of intracellular truncated phospholipids is shown by the complete protection from cytokine induced apoptosis by PAF acetylhydrolase expression. This protection shows truncated phospholipids are the actual effectors of cytokine mediated toxicity.

1. Introduction

This review describes the effects and metabolism of several oxidatively generated phospholipids where both structures and a molecular mechanism of action have been identified. The number of phospholipid structures formed after oxidation of their esterified polyunsaturated residues is diverse, and enormous [1]. It is notable that the examination, formation, structures, functions of biologically active oxidized phospholipids and their products has grown so robustly since we first reported the formation of Platelet-activating Factor (PAF)-like phospholipids formed by phospholipid oxidation in the absence of enzymatic synthesis [2]. The number of structures and the types of activities oxidatively modified phospholipids display are now elegantly summarized in recent reviews of the area by diverse and informed investigators [1, 3–6]. There also is an excellent summary of the diversity of actions and events induced by products of oxidatively modified phospholipids, including the upregulation of cellular signaling pathways, induction of varied types of stresses, formation of neoepitopes, and alteration of immune responses [4]. Oxidized phospholipids are the ligands in oxidized lipoproteins recognized by the scavenger receptor CD36 [7], they mark systemic alcoholic stress [8], and oxidized phosphatidylserine marks apoptotic cells for phagocytosis [9]. Intracellular oxidized phospholipids even specifically adduct key kringle proteins before secretion [10], revealing their presence in normal cellular metabolism. The structures and the diverse pathologic events they promote are now well summarized in a recent compendium describing the formation and actions of oxidized phospholipids [4].

The types and routes of formation of oxidized phospholipids are now understood in detail, but a detailed and precise understanding of how this myriad modified phospholipids modulate cellular and organ systems is not nearly as clear. The effects of oxidized phospholipids on intracellular second messenger systems include increased intracellular Ca+2 or cAMP, but how these and other intracellular mediators respond to oxidized phospholipids is less well understood. The goal here is to summarize three mechanisms where the structure, receptors and mechanism of action are all defined to elucidate pathways connecting oxidized phospholipids to specific events. Inciting stimuli and eventual (patho)physiologic outcomes vary, but at least several pathways now have been elucidated at molecular level. This review therefore focuses on the Platelet-activating Factor inflammatory response, PPARγ signaling, and mitochondria-dependent programmed cell death as three disparate examples of the way by which oxidized phospholipids generate biologic responses. These mechanisms are diverse, and hint that other roles and mechanisms of action of oxidized phospholipids will be equally diverse.

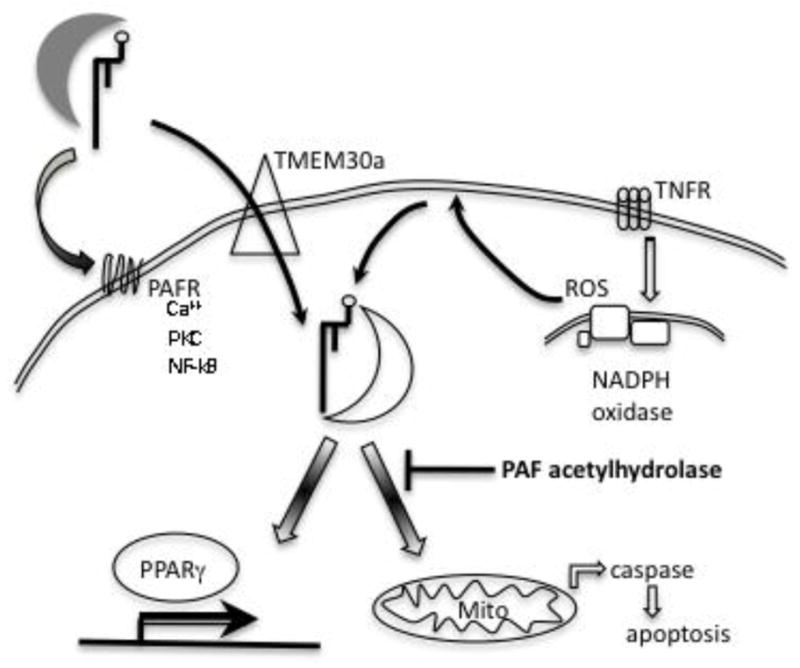

One class of oxidatively generated phospholipids structurally, and hence functionally, mimics the powerful and pleiotropic inflammatory mediator, Platelet-activating Factor (PAF). PAF, and its oxidatively formed, and unregulated, PAF-like phospholipids mimetics, acts on the single G protein coupled PAF receptor present on the surface of all cells of the innate immune system. The PAF receptor is additionally expressed on nearly all cells of the cardiovascular system. A second class of phospholipid truncation products activates the lipid-activated transcription factor PPARγ. Finally, oxidatively truncated phospholipids interact with the pro-apoptotic protein Bid to depolarize and damage mitochondria that allows cytochrome c and apoptosis-inducing factor escape to initiate the intrinsic pathway to apoptotic cell death. Since choline phospholipids are internalized in part through a TMEM30a transport system [11], extracellular oxidized phospholipids have access to intracellular targets.

Phospholipids with choline sn-3 headgroups have been examined as targets of oxidation for several reasons, historic as well as practical, but to the extent that the oxidation or remodeling of esterified fatty acyl residues provoke new biology, the nature of the head group may be inconsequential. Choline phospholipids are the abundant class of membrane and especially lipoprotein phospholipid pools, and so their oxidation is likely. Historically, the first phospholipid oxidation products with a defined mechanism of activation were those that activated the G protein coupled receptor for Platelet-activating Factor (PAF) [2], and the PAF receptor displays marked specificity for the sn-3 choline headgroup [12]. And, a practical consideration is that choline is a quaternary amine and is not derivitized by reactive aldehydes generated by reactive aldehydes generated by Hock fragmentation of esterified fatty acyl hydroperoxides. Other phospholipids are oxidized in parallel with choline phospholipids, forming homologous products. Phosphatidylserine oxidation, in particular, has a distinct and key role in mitochondrial dysfunction, apoptosis, and recognition of apoptotic cells [9]. Ethanolamine phospholipids are oxidized during platelet activation and are sites of prostanoid formation [13, 14]. To a great extent, then, the nature of the sn-3 headgroup (except in the case of PAF signaling) is likely to be immaterial, although this has yet to be explicitly determined.

Phospholipid truncation products not only interact with inflammatory receptors and lipid transfer factors—the pro-apoptotic protein Bid is in fact a phospholipid binding and transfer protein [15]—but are more soluble in the aqueous phase than their parental phospholipids sequestered in phospholipid bilayers and the monolayer of lipoprotein particles. This property alters metabolism of truncated phospholipids relative to bulk phospholipid, and alters their enzymatic metabolism, transcellular transport, and clearance from the circulatory system. Oxidatively truncated phospholipids increase in the circulation during atherosclerosis [16] and alcoholic steatohepatitis [17], and these external phospholipids are actively internalized by a choline phospholipid transport system [11]. Circulating oxidatively truncated phospholipids, and not those intercalated in lipoprotein particles, are cleared with great rapidity, with a t1/2 <30 seconds, primarily by entry into liver and kidney (below). This rapid accumulation of circulating truncated phospholipid means they enter the circulation at least as rapidly as they are cleared, elucidating an unappreciated extensive flux of truncated phospholipids through the circulation during oxidative and inflammatory stresses. This also emphasizes the point that exogenous truncated phospholipids have access to the intracellular environment and can modulate intracellular processes.

Oxidatively truncated phospholipids, but not their biosynthetic phospholipid precursors, are substrates for a class of phospholipases A2, the group VII class of PAF acetylhydrolases. These enzymes selectively recognize the sn-2 acetyl residue of PAF, but also specifically hydrolyze the fatty acyl fragment that remains esterified in the sn-2 position of the phospholipid glycerol backbone after fragmentation of the oxidized fatty acyl residue [19]. These phospholipases, then, actually are highly specific oxidized phospholipid phospholipases. Conservation of these enzymes and function over 100 million years of evolution [18] show the continuing importance of specifically removing phospholipid oxidation products to aerobic organisms.

Oxidatively truncated phospholipids are also generated within cells responding to pro-apoptotic cytokines such as TNFα, and these mobile phospholipid oxidation products in fact are required mediators of TNFα-induced cytotoxicity. The required participation of these lipids is revealed by specifically depleting oxidatively truncated phospholipids through PAF acetylhydrolase expression, which abolishes cell death [18] (Latchoumycandane et al, J Biol Chem, 2012 in press). Cytokine stimulated cells therefore generate sufficient oxidizing radicals to overwhelm normal cellular defenses to form truncated phospholipids that are the actual mediators of mitochondrial dependent cell death.

The way phospholipid truncation products form, the way oxidatively truncated phospholipids display new biologic activities, and the new way they are metabolized and transported is considered in more detail as follows.

2. Oxidized and oxidatively modified phospholipids

There is a tremendous diversity in sn-1 and sn-2 fatty acyl residues esterified in cellular phospholipids, and this diversity is multiplied by the several phosphoester headgroups esterified at the 3-position of the glycerolipid. Oxidation to new phospholipid species exponentially expands this diversity. Diversity is further broadened by the nature of the sn-1 bond, which holds unusual import for inflammation, and hence phospholipid oxidation.

The majority of glycerophospholipids remain as they are synthesized, and so contain fatty acyl residues esterified at both the sn-1 and sn-2 position of a glycerol molecule that forms the backbone of phospholipids. These are diacyl phospholipids and are defined as phosphatidylcholines, or ethanolamines, serines, etc., depending on the sn-3 headgroup. Since these are the most commonly discussed phospholipids “phosphatidylcholine” would seem to cover all the lipids with choline headgroups, but it does not. There are two other classes of choline glycerophospholipids—the term that does cover all phospholipids with this headgroup—that are relevant to phospholipid oxidation, and biologic activity.

The first class of non-phosphatidylcholines are those that contain an ether (C-O-C) bond at the sn-1 position rather than an acyl bond from the carboxylate of esterified fatty acyl residues. These are ether phospholipids formed from the condensation of a fatty aldehyde, rather than a fatty acid, at the sn-1 position. Ether phospholipids are relevant as they can support a range of functions not available to diacyl lipids [20]. These choline phospholipids are abundant in circulating white blood cells, accounting for up to half of the choline phospholipid pool of these inflammatory cells [21]. These ether choline phospholipids are essential in inflammation because these are the precursors for the potent inflammatory mediator Platelet-activating Factor (more on this below) and for arachidonate that will be metabolized to prostaglandins and leukotrienes. Diacyl phosphatidylcholine analogs of PAF are, depending on the assay, up to 1,000-fold less potent than their ether phospholipid counterparts. This is relevant because non-selective oxidation of inflammatory cell membranes attack ether phospholipid structures as well as diacyl phospholipids, and the truncation products of ether phospholipids potently induce PAF-like biologic responses by cells displaying the PAF receptor because the sensitivity of the receptor for PAF and its mimetics is so profound.

The second class of non-phosphatidylcholine choline phospholipids are also ether phospholipids, but these additionally contain a double bond at the C1 position of the fatty ether residue. These are plasmalogens, and are distinguished by the lability of their ether bond. Plasmalogens, both choline and ethanolamine, are readily oxidized, and have been proposed as membrane-associated oxygen traps [22].

3. Oxidative phospholipid truncation

Oxidized phospholipids are glycerophospholipids with one or more newly introduced oxy functions (Figure 2). These include peroxy (OO•), hydroperoxy (OOH) or hydroxy (OH) functions formed by radical or enzymatic attack on a polyunsaturated fatty acyl residue esterified in the glycerol backbone of the phospholipids. Since polyunsaturated fatty acyl residues are preferentially esterified in the sn-2 position of the three-carbon glycerol backbone, oxidized phospholipids preferentially sport oxidized acyl residues in this central position.

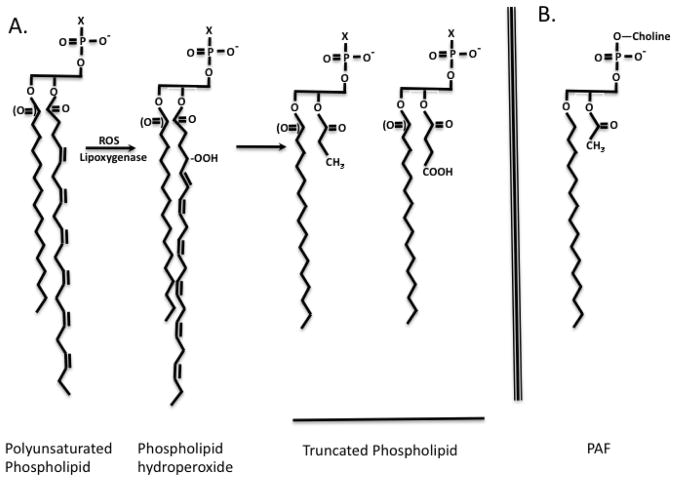

Figure 2. Oxidative phospholipid truncation.

A. Phospholipids with varying sn-1 bonds (ether or acyl) of varied sn-3 head groups (X) undergo identical oxidation of the sn-2 polyunsaturated fatty acyl residue. The abundant docosahexaenoyl ω-3 fatty acyl residue has a proximal olefinic bond between carbon atoms 4 and 5. Chemical peroxidation by reactive free radicals (ROS) preferentially reflects attack at the C4 atom, and shifts the double bond. The peroxyl radical (OO•) abstracts a hydrogen atom to form a hydroperoxide (OOH). Peroxy radicals fragment on either side of the newly introduced oxygen atom to produce methyl terminated truncated fatty acids that are one carbon atom shorter than those that fragment just distal to the peroxy radical. This longer fragment retains the molecular oxygen at the ω-end of the fragment. B. Platelet-activating Factor (PAF). PAF is phospholipid, 1-O-alkyl-2-acetyl-sn-3-glycero-3-phosphocholine recognized at subnanomolar concentrations by a single G protein coupled receptor, the PAF receptor. This receptor recognizes the sn-1 ether bond, the sn-3 choline headgroup, and especially the short sn-2 acetyl residue.

Oxidatively truncated phospholipids are chemical reaction products of phospholipid (hydro)peroxides. Oxidized phospholipids, like oxidized free fatty acids [23, 24], are subject to secondary radical attack, rearrangement of the fatty acyl chain and introduction of other, often oxy, functions. Free radical reactions are not constrained by the Pauli exclusion principle and each fatty residue is the precursor of a host of reaction products. This complexity, as noted, is further complicated by the great diversity of esterified fatty acyl residues. The result is that even a single phospholipid is the precursor of a multitude of reaction products [1, 19].

Oxidation of polyunsaturated fatty acids preferentially results in isomers with the newly introduced oxygen at the outer of a series of double bonds in model systems, with reductants stabilizing and enhancing internal hydroperoxide isomers [24]. The mix of inner and outer hydroperoxide isomers is therefore dynamically responsive to the environment where they form during oxidative attack, with 12- and 15-lipoxygenases contributing to specific peroxide isomers [25]. Phospholipid (hydro)peroxides fragment adjacent to the newly introduce oxygen [24], tending to produce fragmentation products clustered around the position of the original position of the first and last olefinic bond of esterified polyunsaturated fatty acids. The proximal moiety of the fatty acyl residue remains esterified in the phospholipid, with the distal portion of the newly fragmented fatty acyl residue freed to enter the aqueous phase. This oxidative attack, then, forms phospholipids with significantly shortened sn-2 residues.

Esterified arachidonoyl (C20:4) residues with the proximal olefinic bond located between the 5th and 6th carbon atoms fragment to 4 and 5 carbon long fatty acyl remnants (reflecting fragmentation on either side of the C5 peroxy function) that remain esterified in the 2-position of the parent phospholipid. Similarly, esterified docosahexaenoyl (C22:6) residues with their proximal 4,5 olefinic bonds favors products with 3 and 4 carbon long sn-2 residues. Because fragmentation of the fatty acyl chain occurs on either side of the peroxyl site, the longer fragments (5 and 4 carbons long from C20:4 or C22:6, respectively) include the newly introduced oxygen atoms. This forms a newly made ω-oxy (C=O, COH, or COOH) function at the new end of the shortened chain. The one carbon shorter fragments derived from the same phospholipid hydroperoxide precursor by fragmentation proximal to the peroxy function do not contain the new oxygen atom, so these shorter fragments are terminated with a methyl group. These are the shortest common fragmentation products, but identical processes fragment peroxides located farther down the chain to related, longer fragmented phospholipids. Retention of double bonds and rearrangement can produce highly reactive α,β unsaturated carbonyls that are ligands for the scavenger receptor CD36 or that chemically adduct proteins. Secondary oxidative attack can shorten already oxidized sn-2 residues [26, 27], and phospholipids bearing the two-carbon acetyl residue are products of oxidative attack on full length, membrane integrated polyunsaturated phospholipids.

Fragmentation to short truncated phospholipids has several consequences, ranging from membrane disruption to conferring a new ability to productively interact with receptors and their signaling programs. Oxidative attack on esterified arachidonoyl and docosahexaenoyl residues produces phospholipids with PAF-like activity. Conversely, attack of the more common linoleoyl and linolenoyl residues, with the proximal olefinic bond between carbons 9 and 10, produces 8 and 9 carbon long truncated phospholipids with less PAF-like activity, but with more activity as PPARγ agonists and Bid-dependent agents of apoptosis.

4. Oxidized phospholipids with defined cellular targets

4.1. PAF-like activity

PAF-like phospholipids (Figure 2A) are phospholipid oxidation products bearing short sn-2 fatty acyl fragments that stimulate the receptor for Platelet-activating Factor (PAF; 1-O-alkyl-2-acetyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine). PAF (Fig. 2B) is a choline phospholipid, but a unique one. It contains an sn-1 ether bond, and additionally is marked by its novel sn-2 acetyl residue. The ether choline phospholipid precursors of PAF are common in inflammatory cells [28] that make PAF. PAF synthesis is regulated and only after stimulation is the sn-2 fatty acyl residue hydrolyzed and replaced by an acetyl residue from acetyl-Coenzyme A. PAF, then, is produced by stimulated cells and only upon activation [12].

PAF is a potent agonist for platelets, but also most other cells of the inflammatory system (e.g. polymorphonuclear leukocytes, macrophages endothelial cells, etc.), because it is the agonist for the PAF receptor expressed by these cells. The PAF receptor is a single G protein coupled receptor that recognizes the sn-1 ether bond, the short sn-2 acetyl group, and the sn-3 choline residue [12]. PAF has a wide range of inflammatory and non-inflammatory activities [29] through activation of endothelial cells that attract circulating inflammatory cells to localize and initiate the inflammatory response [30].

PAF is the single known physiologic agonist of the PAF receptor, but phospholipid truncation generates non-physiologic PAF receptor agonists with the same actions as PAF since they functionally engage the PAF receptor [2, 31]. These phospholipids are structurally distinct from PAF because they do not (generally) contain the sn-2 acetyl residue of PAF, but rather a series of short, sn-2 fatty acyl fragments. They may not even contain the ether bond of PAF, but because PAF is so very potent, even PAF analogs can activate cells at subnanomolar concentrations [32]. Short, truncated phospholipids are inflammatory, and especially so when they arise from platelets, monocytes and neutrophils that possess a significant pool of ether choline phospholipids. This means the critical roles of PAF in initiating and extending the inflammatory response can instead be initiated instead by analogs generated by unregulated chemical attack on common cellular and lipoprotein phospholipids. The pathophysiologic presence of PAF is tightly controlled by inflammatory signaling, whereas phospholipid oxidation is temporally, spatially and uncontrollably initiated through unregulated chemical events. The pro-inflammatory processes of atherosclerosis and other oxidative stress reflect the inappropriate appropriation of what should be a carefully controlled system.

Oxidized phospholipids circulate in association with lipoprotein particles [33] during atherosclerosis and are components of the lipid plaque of atherosclerotic lesions [16]. They circulate during the oxidative and inflammatory stress induced by chronic ethanol ingestion [17], and circulating oxidized phospholipids are valid markers of the risk, extent and lesion burden of atherosclerosis [34]. Shortened and fragmented phospholipid products active platelets, monocytes and polymorphonuclear lymphocytes through their PAF receptors [31, 35], linking these oxidatively modified lipids to inflammatory responses.

4.2. PPARγ agonists

Phospholipids with intermediate length sn-2 residues stimulate the transcription factor Peroxisomal Proliferator Activated Receptor gamma (PPARγ). PPARγ is a nuclear lipid-activated transcription factor, and select oxidatively truncated phospholipids [36] are ligands and agonists of PPARγ [37]. Extracellular oxidatively truncated phospholipids, after internalization, stimulate PPARγ, which in turn induces cyclooxygenase-2 expression [38]. Cyclooxygenases initiate formation of all prostaglandins and thromboxane A2, and are a key regulatory point for their production.

The primary transcription factor controlling CD36 is expression is PPARγ. This scavenger receptor recognizes and binds oxidized low-density lipoprotein [39] and apoptotic cells [40] through the oxidatively modified phospholipids embedded in the particle or cell. PPARγ is itself regulated by oxidatively truncated phospholipids [36] and CD36 is an essential element in monocyte function. PPARγ has a critical role in reverse cholesterol metabolism [41], so phospholipid oxidation stimulates turnover of the particles that contain it [42, 43].

Lysophosphatidic acid, a phospholipid lacking an sn-2 residue, is an essential intermediate in phospholipid metabolism and remodeling, that also stimulates PPARγ [44]. Hydrolysis of truncated phospholipids by phospholipases A2 produces lysophosphatidylcholines that are substrates of phospholipases D (autotaxin) of activated platelets [45]. Lysophosphatidic acid is an agonist for PPARγ when present as an extracellular circulating agonist [46] and when present as a component of cellular lipid metabolism [47].

4.3. Exogenous pro-apoptotic oxidized phospholipids

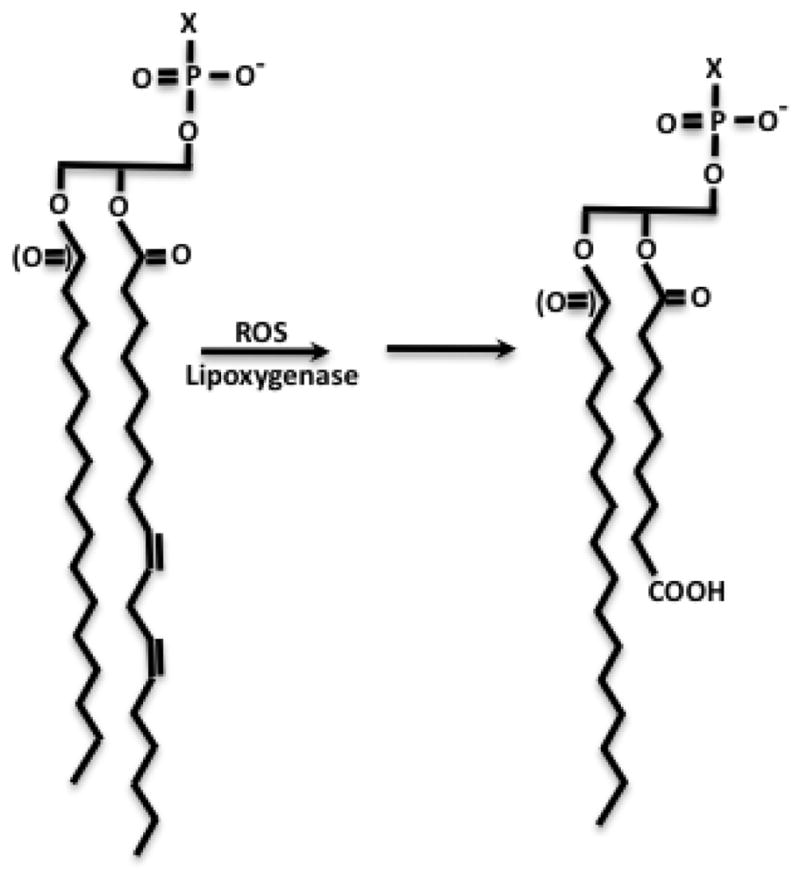

Oxidatively truncated phospholipids with intermediate length sn-2 fragments (Fig. 3) directly interact with mitochondria. This damages the organelle’s physical and functional integrity, permitting cytochrome c escape. Cytoplasmic cytochrome c is problematic because it initiates the intrinsic apoptotic cascade [48]. A common truncated phospholipid of this class contains a 9-carbon long fatty acyl fragment terminated with either an ω-terminal aldehyde or (after oxidation) a carboxylate. The fragment thus is either 9-oxo-nonoanoyl or an azelaoyl (the trivial name for a nine-carbon dicarboxylate fatty acid) residue that remains esterified in the original lysophospholipid. These products are abundant because they are derived from the most abundant esterified polyunsaturated fatty acyl residue, esterified linoleic acid, and they are the common product of a single oxidative reaction. Azelaoyl-phosphatidylcholine is both expected as a direct oxidation product of linoleoyl choline phospholipids, and can be unambiguously identified by an intramolecular rearrangement in the gas phase during mass spectrometry that produces an azelaoyl mono methyl ester [36]. Azelaoyl phosphatidylcholine is an obvious peak in the chromatogram of oxidized lipoprotein particles [36], and accumulates in the circulation of both rats and humans during chronic ethanol ingestion leading to alcoholic steatohepatitis [17].

Figure 3. Intermediate length truncated phospholipids.

Oxidation of abundant sn-2 linoleoyl (C18:2) shown here or linolenoyl (C18:3) generates truncated phospholipids with intermediate length residues, some of which are anions. Anionic residues are solvated by flipping the truncated residue from the apolar environment of a bilayer into the aqueous phase [66]. This newly introduced charge enhances solubility, but is disruptive to lipid packing.

Exogenous azelaoyl choline phospholipid is apoptotic because it is rapidly internalized, in part by a transport system described below, where it rapidly becomes associated with mitochondria [48]. Association of the truncated phospholipid with mitochondria depolarizes the organelle, allowing it to swell. This allows apoptosis-inducing factor to escape to the cytoplasm and then to the nucleus to aid DNA degradation. Mitochondrial swelling also allows cytochrome c to escape to the cytoplasm. This is deleterious because it completes the apoptosome that processes pro-caspase 9 to active caspase 9. Caspase 9 then activates pro-caspase 3, an effector protease of apoptosis, to its active form. This pathway is activated by internalization of exogenous oxidatively truncated phospholipids because irreversible inhibition of caspase 9 blocks downstream caspase 3 activation and prevents apoptosis induced by truncated phospholipids.

Mitochondrial damage is responsible for the apoptotic cascade induced by this class of truncated phospholipids because over-expression of the anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-XL, which alters the ratio of pro-and anti-apoptotic mitochondria interacting factors, blocks cytochrome c escape and apoptosis [49]. Azelaoyl phosphatidylcholine is not alone in this and its sn-1 ether species is twice as effective as this diacyl phospholipids. Additionally, phospholipids with other remnants of fragmented phospholipids esterified at the sn-2 carbon also damaged mitochondrial function and integrity.

The way that truncated phospholipids damage mitochondrial structure and function is not fully known, but the interaction between mitochondria and the relatively hydrophilic truncated phospholipid is direct. It also is continuous because depolarization of isolated mitochondria by the truncated phospholipid is readily reversed by the addition of albumin that sequestered this lipid [49]. Recovery from truncated phospholipid exposure by albumin shows the amphipathic phospholipid does not interfere with mitochondrial integrity by dissolving their membranes. Rather, phospholipid intercalation into mitochondria promotes swelling through the mitochondrial permeability transition pore because blockade of the pore with cyclosporin A interferes with the phospholipid-induced loss of the organelle’s electrochemical gradient. Furthermore, mitochondria isolated from Bcl-XL over-expressing cells were protected from truncated phospholipid depolarization, while organelles isolated from Bid−/− animals lacking this pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 family member were resistant to this depolarization. Recombinant full-length Bid restored sensitivity of mitochondria to azelaoyl-phosphatidylcholine. This then means phospholipid oxidation products physically interact with mitochondria to continually depolarize this organelle. This occurs without permanent harm to the organelle for short periods, although eventually loss of intra-organelle components compromises mitochondrial function.

Bid, although a member of the Bcl-2 family of pro- and anti-apoptotic proteins, uniquely possesses phospholipid binding and transfer activity [50] that inserts lysophospholipids into mitochondrial membranes [15]. Lysophospholipid binding alters the tertiary structure of the Bid protein, and proteolytically truncated Bid is more effective in phospholipid binding and stimulated release of cytochrome c from target mitochondria than intact Bid [51]. This connects truncated phospholipids, caspase action and Bid as members of a common pathway. We find that Bid also mobilizes water-soluble oxidatively truncated phospholipids, aiding their interaction with mitochondria [49]. Bcl-XL interferes with this Bid-dependent process, and so reduces mitochondrial damage initiated by oxidatively truncated phospholipids. Bid is a therefore a co-factor in the promotion of cellular death by truncated phospholipids, while the actual effectors of apoptosis are oxidatively truncated phospholipids.

Exogenous oxidatively truncated phospholipids are present and increase over prolonged times in the circulation of apoE−/− animals prone to atherosclerosis fed a western style diet [16]. Truncated phospholipids are also a feature in the more rapidly induced oxidative and inflammatory stress induced by chronic ethanol ingestion in both an animal model [17] and humans [8, 17, 52]. The animal model of chronic (but not excessive since the alcohol level approximates 0.1% v/v) ethanol ingestion shows that truncated phospholipids accumulate in the circulation just as the liver mounts an inflammatory response. The hysteresis in circulating oxidized and truncated phospholipids show these do not correlate to the oxidative stress of ethanol catabolism, but instead correlate to an inflammatory response that becomes significant after four weeks of ethanol ingestion. Ablation of the inflammatory response by feeding the animals the small molecule taurine [53] abolished accumulation of truncated phospholipid in the blood of ethanol-fed animals [17]. Chronic inflammatory insults are therefore a sufficient stimulus to induce production and accumulation of oxidatively damaged phospholipids, which actually are only the visible portion of a massive flux of truncated phospholipids through the circulation, as developed below.

4.4. Endogenous truncated phospholipids

Phospholipid oxidation products accumulate in the external environment of vascular cells and are internalized to initiate intrinsic apoptosis, but these same oxidatively modified phospholipids are also generated within cells either by photochemical oxidation or by cellular metabolism. They are similarly cytotoxic.

Photochemical oxidation induces apoptosis and oxidatively truncated phospholipids are formed when cells are irradiated with UVB light [32]. Destruction of either the phospholipid hydroperoxide precursors of truncated phospholipids formed during this oxidative stress or their metabolism after oxidative fragmentation by over expressing PAF acetylhydrolase abolishes UVB induced cell death [54]. Much of the effect on the immune system and keratinocytes reflect the formation of PAF-like phospholipids [32] that stimulate the PAF receptor on the external aspect of the cell, but also reflect internal truncated phospholipids that act on PPARγ [37].

Oxidatively truncated phospholipids are directly formed within cells through cellular metabolism. Cells responding to TNFα or Fas Ligand stimulation activate their NADPH oxidase complex (Latchoumycandane et al, J Biol Chem, 2012 in press). This produces radicals, overwhelming cellular antioxidant defense, that peroxidize cellular phospholipids. Either blockade of NADPH oxidase activity or over-expression of the phospholipid specific glutathione peroxidase 4 that chemically reduces phospholipid hydroperoxides prevents accumulation of oxidatively truncated phospholipids. Both maneuvers also prevent cytokine induced cell death. Conversely, siRNA mediated loss of glutathione peroxidase 4 allows excessive peroxidized phospholipid formation, and it enhances cytokine cytotoxicity. Phospholipid hydroperoxides are therefore essential components of cytokine-stimulated apoptosis.

The question is whether phospholipid hydroperoxides are directly cytotoxic, or whether their involvement stems from their oxidation and fragmentation to truncated phospholipids. PAF acetylhydrolases can resolve this difficult problem because they specifically hydrolyze oxidized phospholipids (below). Over-expression of type II PAF acetylhydrolase reduces the cellular load of truncated phospholipids formed in response to TNFα, and did so without reducing the increased cellular content of phospholipid hydroperoxides. PAF acetylhydrolase expression fully protected cells from TNFα induced apoptosis, showing that peroxidized phospholipids were only cytotoxic because they are precursors of truncated phospholipids that are the actual deleterious agents.

These novel outcomes prove several issues. 1) PAF acetylhydrolase substrates—likely the oxidatively truncated phospholipids that accumulate after cytokine stimulation —are the key downstream components of cytokine-induced apoptosis. 2) Oxidized phospholipids are the actual mediators of Bid-enhanced apoptosis. Pro-apoptotic Bid binds and transports lysolipids, so the way that Bid promotes apoptosis is through increased accesses of truncated phospholipids to mitochondria. That is, Bid is a co-factor that delivers the actual apoptotic mediator to mitochondria 3) Accumulation of truncated phospholipids, whether formed endogenously from cytokine or photochemical oxidation or transported into the cell, increases the load of pro-apoptotic cellular mediators. Cytokine signaling can be augmented through uptake and mixing of exogenous truncated phospholipids with internally generated lipids. 4) The way reactive oxygen species are involved in cellular apoptosis is not direct; they are required for the formation of truncated phospholipids and it is oxidatively truncated phospholipids, rather than reactive oxygen species themselves, that are directly apoptotic. 5) The primary determinants of resistance to oxidative stress are phospholipid hydroperoxide reductive systems and/or intracellular hydrolytic enzymes that metabolize oxidized phospholipids and their truncated products.

Overall, oxidation of cellular and circulating phospholipids forms new structures with distinct and definable activities. Phospholipid precursors are sequestered in membranes and lipoproteins, but their oxidation and/or fragmentation products are relatively water-soluble. These mobile structures no longer constrained to phospholipid bilayers, with motility aided by albumin in the circulation or Bid within cells, display novel actions at external and internal receptors. Several targets of these modified phospholipids have been defined, but new activities [5] await molecular identification of their new targets in the complex and overlapping web of biologically active oxidatively modified phospholipids.

5. Metabolism

5.1 Hydrolysis

Oxidative modification of phospholipids primarily occurs at the sn-2 glycerol carbon because that is the preferred site of polyunsaturated phospholipid incorporation. Selective metabolism of oxidized phospholipids also is targeted to this site. Phospholipases A2 act on sn-2 residues, but the large number of enzymes and families [55] of phospholipases A2 do not distinguish among the multitude of different sn-2 residues. Location of the ester bond in the glycerol backbone rather than the chemical identity of the fatty acyl substrate constrains hydrolysis by this class of esterases. There are rare exceptions to this lack of identification of substrates by phospholipases A2, the arachidonoyl specific class IV phospholipase A2, and two families (class VII and VIII) of PAF acetylhydrolases. The type I PAF acetylhydrolases of class VIII phospholipases A2 specifically hydrolyze the acetyl residue of PAF, and no other substrates. In contrast the class VII enzymes hydrolyze PAF, but additionally contain an extended active site that enables them to hydrolyze truncated and oxidized phospholipids [56]. The active site cannot enclose intact, long chain phospholipids, and so these enzymes are completely specific in attacking PAF and oxidized phospholipids.

Protective hydrolysis of oxidatively damaged phospholipids is in fact the likely original, and remaining, function of these unusual phospholipases A2. Schizosaccharomyces pombe, a single celled yeast with an estimated divergence time from us of 100 million years, contains one of the smallest genomes sequenced, yet it retains a PAF acetylhydrolase. This Plg7 gene encodes a phospholipase A2 that is highly homologous to mammalian group VII enzymes and hydrolyzes PAF, as expected, but also effectively hydrolyzes truncated phospholipid [18]. This yeast does not and can not generate PAF. It does not possess any G protein coupled receptors and so does not have a PAF receptor nor does it respond to PAF, so the organism should not require a PAF acetylhydrolase. Instead, the role of Plg7 is revealed when the cells are loaded with polyunsaturated fatty acids and oxidized by a transition metal. This oxidative stress is lethal, but over-expression of Plg7p enzyme, or an intracellular mammalian group VII enzyme, protects yeast against oxidative cell death. This outcome elucidates three interconnected and critical points: oxidized phospholipids directly cause oxidative death; depletion of oxidatively damaged phospholipids by selective hydrolysis is protective during oxidant stress; and, retention of a PAF acetylhydrolase over 100 million years of evolution shows oxidized phospholipids remain a significant threat.

PAF acetylhydrolase was originally purified from human plasma [57], and named based on its ability to hydrolyze the sn-2 acetyl residue of PAF. A homologous intracellular enzyme, the type II PAF acetylhydrolase, was purified and then cloned from bovine liver [58]. These enzymes, along with that of S. pombe Plg7p, constitute the class VII phospholipases A2. These enzymes hydrolyze PAF, but also are able to accommodate oxidatively damaged phospholipids in their active site. They do so with complete specificity for oxidized phospholipids because they are unable to attack biosynthetic phospholipids bearing long, unmodified sn-2 fatty acyl residues [19]. A subsequent purification of LDL-associated phospholipase A2 from human plasma, where alignment with the deposited human sequence identified it as plasma PAF acetylhydrolase [59], confirms PAF and oxidized phospholipids are the enzymes sole substrates. These enzymes are Ca++-independent, and so are present in a fully activated form with only substrate availability regulating their action.

Two other phospholipases, Ca++-independent phospholipase A2 (iPLA2) and peroxiredoxin 6, also act on oxidized phospholipids, but the role of both is complicated by their actions on normal phospholipids. Peroxiredoxin 6 is a protective antioxidant that both chemically reduces water-soluble and phospholipid hydroperoxides, and hydrolyzes phospholipids prior to their oxidative fragmentation through a second active site [60, 61].

5.2 Transport and clearance

Plasma PAF acetylhydrolase is the sole enzyme in the circulation that hydrolyzes and inactivates PAF [56], and accordingly would be expected to be the sole mechanism to control the level of circulating PAF and truncated phospholipid substrates. These events, however, are unrelated. The primary way these phospholipids are cleared from blood is through their uptake into liver and kidney [62]. Uptake is so rapid, with a half life less than 30 seconds, that not only is it difficult to accurately measure, it is far faster than circulating plasma PAF acetylhydrolase can metabolize PAF. In vivo studies also show that PAF and a truncated phospholipid compete for uptake, suggesting a common mechanism for clearance [62]. Circulating PAF acetylhydrolase instead may be more important to the metabolism of peroxidized [63] and oxidized phospholipids [64] associated with the low density lipoproteins that bind and transport plasma PAF acetylhydrolase than to water soluble PAF and truncated phospholipids.

Uptake of phospholipids into cells, let alone tissues, occurs through a largely unknown entity(ies), but clearly is distinct from the opposite one way efflux processes that enhance flow of bulk phospholipid, cholesterol and phosphatidylserine from the intracellular to the extracellular compartment. In contrast to mammalian cells, phospholipid uptake is genetically defined in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. In these single cells, uptake of PAF and short-chained phospholipids depends on a two-component system of a P4-type ATPase transporter and a second subunit, independently identified as Ros3 and Lem3 [65]. Mammalian cells express mRNA that encodes a related gene, and expression of this TMEM30a partially rescues yeast with genetically deleted Ros3 [11]. Conversely, knockdown of TMEM30a reduces PAF and truncated phospholipid uptake in mammalian cells. From this, we conclude that mammalian cells accumulate exogenous phospholipids that are sufficiently water soluble to be presented as monomeric molecules through a transport system(s) that includes TMEM30a. TMEM30a is present in endothelial cells, but we do not yet know whether it participates in the rapid clearance of oxidized phospholipids from the circulation. Oxidized phospholipids can therefore be internalized independently of intact oxidized lipoprotein particles.

6. Summary

Chemical or enzymatic oxidation of phospholipid with sn-2 polyunsaturated fatty acyl residues generates phospholipid (hydro)peroxides, with preferential oxidation of outer olefinic bonds in polyunsaturated fatty acyl residues. These oxidatively modified phospholipids are friable and subject to chemical decomposition by β-scission at the site of the peroxy function. The fragments from the ω-end of the esterified fatty acyl residue are water-soluble, but the truncated fatty acyl fragments arising from the proximal α-end of the fatty acyl residue remains esterified in the phospholipid. These truncated phospholipids range in length, depending on the location of the original double bond in the polyunsaturated fatty acyl reside, and in their solubility and disruption of phospholipid packing. These esterified fragments may or may not terminate with the newly introduced oxygen molecule, and this depends on which side of the peroxy function cleavage occurred. Defined oxidized phospholipids also have been shown to be the ligands for and agonists of CD36, reviewed separately [7].

Truncated phospholipid with short sn-2 fragments activate the innate immune system at multiple points through their mimicry of the potent inflammatory mediator PAF. Phospholipids bearing intermediate length fragments are agonists of the lipid-activated transcription factor PPARγ. Truncated phospholipids with the longer 9-carbon sn-2 fragment derived from linoleoyl and linolenoyl fragmentation interact with mitochondria in a Bid-aided way to induce the caspase cascade of intrinsic apoptosis. Oxidatively truncated phospholipids are selectively internalized in part by a transport system employing TMEM30a, but also are formed within cells responding to cytokine stimulation. Oxidized phospholipids are specifically hydrolyzed by dedicated phospholipases A2, and these PAF acetylhydrolases have been conserved since ancient times to protect cells from oxidative cell death.

Figure 1. Exogenous and cytokine-induced truncated phospholipids stimulate defined biologic processes.

External truncated choline phospholipids are transported by lipoproteins and albumin, while retaining appreciable aqueous solubility. Truncated choline phospholipids with short sn-2 residues activate the G protein coupled PAF receptor that stimulates endogenous second messenger formation. Exogenous truncated phospholipids are internalized through a TMEM30a translocation system, allowing external truncated phospholipids access to the cytoplasm. Truncated phospholipids are also generated within cells by cytokine signaling that activates NADPH oxidase. Internal truncated phospholipid associate with Bid, depolarizing mitochondria and promoting intrinsic apoptotic cellular death. Intracellular PAF acetylhydrolase specifically hydrolyzes oxidatively damaged phospholipids, and protects cells from cytokine and oxidative death.

Highlights.

Phospholipid hydroperoxides fragment to truncated phospholipids

Truncated phospholipids activate the external PAF receptor, and after internalization activate PPARγ, and depolarize mitochondria to initiate apoptosis

Cytokine signaling creates internal truncated phospholipid that are required mediators of cytokine-induced apoptosis

PAF acetylhydrolases specifically hydrolyze truncated phospholipids, protecting cells from oxidative death

Acknowledgments

I deeply appreciate all the members of the laboratory who have participated in this area over the years. I also greatly appreciate the aid and insights of many and valuable colleagues. This work was supported by NIH grants AA17748 and HL92747.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Domingues MR, Reis A, Domingues P. Mass spectrometry analysis of oxidized phospholipids. Chem Phys Lipids. 2008;156:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.chemphyslip.2008.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smiley PL, Stremler KE, Prescott SM, Zimmerman GA, McIntyre TM. Oxidatively fragmented phosphatidylcholines activate human neutrophils through the receptor for platelet-activating factor. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:11104–11110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith WL, Murphy RC. Oxidized lipids formed non-enzymatically by reactive oxygen species. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:15513–15514. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R800006200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bochkov VN, Oskolkova OV, Birukov KG, Levonen AL, Binder CJ, Stockl J. Generation and biological activities of oxidized phospholipids. Antioxidant redox signal. 2010;12:1009–1059. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Greig FH, Kennedy S, Spickett CM. Physiological effects of oxidized phospholipids and their cellular signaling mechanisms in inflammation. Free radical biology & medicine. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.10.481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spickett CM, Fauzi NM. Analysis of oxidized and chlorinated lipids by mass spectrometry and relevance to signalling. Biochem Soc Trans. 2011;39:1233–1239. doi: 10.1042/BST0391233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hazen SL. Oxidized phospholipids as endogenous pattern recognition ligands in innate immunity. J Biol Chem. 2008 doi: 10.1074/jbc.R700054200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adachi J, Matsushita S, Yoshioka N, Funae R, Fujita T, Higuchi S, Ueno Y. Plasma phosphatidylcholine hydroperoxide as a new marker of oxidative stress in alcoholic patients. J Lipid Res. 2004;45:967–971. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M400008-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tyurin VA, Tyurina YY, Kochanek PM, Hamilton R, DeKosky ST, Greenberger JS, Bayir H, Kagan VE. Oxidative lipidomics of programmed cell death. Methods Enzymol. 2008;442:375–393. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(08)01419-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Edelstein C, Pfaffinger D, Yang M, Hill JS, Scanu AM. Naturally occurring human plasminogen, like genetically related apolipoprotein(a), contains oxidized phosphatidylcholine adducts. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1801:738–745. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2010.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen R, Brady E, McIntyre TM. Human TMEM30a Promotes Uptake of Anti-tumor and Bioactive Choline Phospholipids into Mammalian Cells. J Immunol. 2011;186:3215–3225. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Prescott SM, Zimmerman GA, Stafforini DM, McIntyre TM. Platelet-activating factor and related lipid mediators. Annu Rev Biochem. 2000;69:419–445. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thomas CP, Morgan LT, Maskrey BH, Murphy RC, Kuhn H, Hazen SL, Goodall AH, Hamali HA, Collins PW, O’Donnell VB. Phospholipid-esterified Eicosanoids Are Generated in Agonist-activated Human Platelets and Enhance Tissue Factor-dependent Thrombin Generation. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:6891–6903. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.078428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maskrey BH, Bermudez-Fajardo A, Morgan AH, Stewart-Jones E, Dioszeghy V, Taylor GW, Baker PR, Coles B, Coffey MJ, Kuhn H, O’Donnell VB. Activated platelets and monocytes generate four hydroxyphosphatidylethanolamines via lipoxygenase. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:20151–20163. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611776200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goonesinghe A, Mundy ES, Smith M, Khosravi-Far R, Martinou JC, Esposti MD. Pro-apoptotic Bid induces membrane perturbation by inserting selected lysolipids into the bilayer. Biochem J. 2005;387:109–118. doi: 10.1042/BJ20041389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Podrez EA, Poliakov E, Shen Z, Zhang R, Deng Y, Sun M, Finton PJ, Shan L, Febbraio M, Hajjar DP, Silverstein RL, Hoff HF, Salomon RG, Hazen SL. A novel family of atherogenic oxidized phospholipids promotes macrophage foam cell formation via the scavenger receptor CD36 and is enriched in atherosclerotic lesions. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:38517–38523. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205924200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang L, Latchoumycandane C, McMullen MR, Pratt BT, Zhang R, Papouchado BG, Nagy LE, Feldstein AE, McIntyre TM. Chronic alcohol exposure increases circulating bioactive oxidized phospholipids. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:22211–22220. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.119982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Foulks JM, Weyrich AS, Zimmerman GA, McIntyre TM. A yeast PAF acetylhydrolase ortholog suppresses oxidative death. Free radical biology & medicine. 2008;45:434–442. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.04.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stremler KE, Stafforini DM, Prescott SM, McIntyre TM. Human plasma platelet-activating factor acetylhydrolase. Oxidatively fragmented phospholipids as substrates. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:11095–11103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gorgas K, Teigler A, Komljenovic D, Just WW. The ether lipid-deficient mouse: tracking down plasmalogen functions. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1763:1511–1526. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.08.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mueller HW, O’Flaherty JT, Greene DG, Samuel MP, Wykle RL. 1–0-alkyl-linked glycerophospholipids of human neutrophils: Distribution of arachidonate and other acyl residues in the ether-linked and diacyl species. J Lipid Res. 1984;25:383–388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zoeller RA, Morand OH, Raetz CR. A possible role for plasmalogens in protecting animal cells against photosensitized killing. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:11590–11596. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Frankel EN. Volatile lipid oxidation products. Prog Lipid Res. 1982;22:1–33. doi: 10.1016/0163-7827(83)90002-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Frankel EN. Chemistry of free radical and singlet oxidation of lipids. Progr Lipid Res. 1984;23:197–221. doi: 10.1016/0163-7827(84)90011-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burger F, Krieg P, Marks F, Furstenberger G. Positional- and stereo-selectivity of fatty acid oxygenation catalysed by mouse (12S)-lipoxygenase isoenzymes. Biochemical J. 2000;348(Pt 2):329–335. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tsoukatos DC, Arborati M, Liapikos T, Clay KL, Murphy RC, Chapman MJ, Ninio E. Copper-catalyzed oxidation mediates PAF formation in human LDL subspecies. Protective role of PAF:acetylhydrolase in dense LDL. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1997;17:3505–3512. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.17.12.3505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen X, Zhang W, Laird J, Hazen SL, Salomon RG. Polyunsaturated phospholipids promote the oxidation and fragmentation of gamma-hydroxyalkenals: formation and reactions of oxidatively truncated ether phospholipids. J Lipid Res. 2008;49:832–846. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M700598-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mueller HW, O’Flaherty JT, Wykle RL. Ether lipid content and fatty acid distribution in rabbit polymorphonuclear neutrophil phospholipids. Lipids. 1982;17:72–77. doi: 10.1007/BF02535178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Souza DG, Pinho V, Soares AC, Shimizu T, Ishii S, Teixeira MM. Role of PAF receptors during intestinal ischemia and reperfusion injury. A comparative study between PAF receptor-deficient mice and PAF receptor antagonist treatment. Br J Pharmacol. 2003;139:733–740. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carveth HJ, Shaddy RE, Whatley RE, McIntyre TM, Prescott SM, Zimmerman GA. Regulation of platelet-activating factor (PAF) synthesis and PAF-mediated neutrophil adhesion to endothelial cells activated by thrombin. Semin Thromb Hemost. 1992;18:126–134. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1002417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marathe GK, Zimmerman GA, Prescott SM, McIntyre TM. Activation of vascular cells by PAF-like lipids in oxidized LDL. Vascul Pharmacol. 2002;38:193–200. doi: 10.1016/s1537-1891(02)00169-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marathe GK, Johnson C, Billings SD, Southall MD, Pei Y, Spandau D, Murphy RC, Zimmerman GA, McIntyre TM, Travers JB. Ultraviolet B radiation generates platelet-activating factor-like phospholipids underlying cutaneous damage. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:35448–35457. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503811200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marathe GK, Davies SS, Harrison KA, Silva AR, Murphy RC, Castro-Faria-Neto H, Prescott SM, Zimmerman GA, McIntyre TM. Inflammatory platelet-activating factor-like phospholipids in oxidized low density lipoproteins are fragmented alkyl phosphatidylcholines. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:28395–28404. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.40.28395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tsimikas S, Kiechl S, Willeit J, Mayr M, Miller ER, Kronenberg F, Xu Q, Bergmark C, Weger S, Oberhollenzer F, Witztum JL. Oxidized phospholipids predict the presence and progression of carotid and femoral atherosclerosis and symptomatic cardiovascular disease: five-year prospective results from the Bruneck study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:2219–2228. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen R, Chen X, Salomon RG, McIntyre TM. Platelet activation by low concentrations of intact oxidized LDL particles involves the PAF receptor. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2009;29:363–371. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.178731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Davies SS, Pontsler AV, Marathe GK, Harrison KA, Murphy RC, Hinshaw JC, Prestwich GD, Hilaire AS, Prescott SM, Zimmerman GA, McIntyre TM. Oxidized alkyl phospholipids are specific, high affinity peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma ligands and agonists. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:16015–16023. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100878200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang Q, Southall MD, Mezsick SM, Johnson C, Murphy RC, Konger RL, Travers JB. Epidermal peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma as a target for ultraviolet B radiation. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:73–79. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409795200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pontsler AV, St Hilaire A, Marathe GK, Zimmerman GA, McIntyre TM. Cyclooxygenase-2 is induced in monocytes by PPARgamma and oxidized alkyl phospholipids from oxidized LDL. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:13029–13036. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109546200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rahaman SO, Lennon DJ, Febbraio M, Podrez EA, Hazen SL, Silverstein RL. A CD36-dependent signaling cascade is necessary for macrophage foam cell formation. Cell Metab. 2006;4:211–221. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Greenberg ME, Sun M, Zhang R, Febbraio M, Silverstein R, Hazen SL. Oxidized phosphatidylserine-CD36 interactions play an essential role in macrophage-dependent phagocytosis of apoptotic cells. J Exp Med. 2006;203:2613–2625. doi: 10.1084/jem.20060370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Malur A, Baker AD, McCoy AJ, Wells G, Barna BP, Kavuru MS, Malur AG, Thomassen MJ. Restoration of PPARgamma reverses lipid accumulation in alveolar macrophages of GM-CSF knockout mice. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2011;300:L73–80. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00128.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ricote M, Huang J, Fajas L, Li A, Welch J, Najib J, Witztum JL, Auwerx J, Palinski W, Glass CK. Expression of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARgamma) in human atherosclerosis and regulation in macrophages by colony stimulating factors and oxidized low density lipoprotein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:7614–7619. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.13.7614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Babaev VR, Yancey PG, Ryzhov SV, Kon V, Breyer MD, Magnuson MA, Fazio S, Linton MF. Conditional knockout of macrophage PPARgamma increases atherosclerosis in C57BL/6 and low-density lipoprotein receptor-deficient mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:1647–1653. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000173413.31789.1a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McIntyre TM, Pontsler AV, Silva AR, St Hilaire A, Xu Y, Hinshaw JC, Zimmerman GA, Hama K, Aoki J, Arai H, Prestwich GD. From the Cover: Identification of an intracellular receptor for lysophosphatidic acid (LPA): LPA is a transcellular PPARgamma agonist. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:131–136. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0135855100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Samadi N, Bekele R, Capatos D, Venkatraman G, Sariahmetoglu M, Brindley DN. Regulation of lysophosphatidate signaling by autotaxin and lipid phosphate phosphatases with respect to tumor progression, angiogenesis, metastasis and chemo-resistance. Biochimie. 2011;93:61–70. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2010.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang C, Baker DL, Yasuda S, Makarova N, Balazs L, Johnson LR, Marathe GK, McIntyre TM, Xu Y, Prestwich GD, Byun HS, Bittman R, Tigyi G. Lysophosphatidic acid induces neointima formation through PPARgamma activation. J Exp Med. 2004;199:763–774. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stapleton CM, Mashek DG, Wang S, Nagle CA, Cline GW, Thuillier P, Leesnitzer LM, Li LO, Stimmel JB, Shulman GI, Coleman RA. Lysophosphatidic acid activates peroxisome proliferator activated receptor-gamma in CHO cells that over-express glycerol 3-phosphate acyltransferase-1. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e18932. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen R, Yang L, McIntyre TM. Cytotoxic phospholipid oxidation products. Cell death from mitochondrial damage and the intrinsic caspase cascade. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:24842–24850. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702865200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chen R, Feldstein AE, McIntyre TM. Suppression of mitochondrial function by oxidatively truncated phospholipids is reversible, aided by bid, and suppressed by Bcl-XL. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:26297–26308. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.018978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Esposti MD, Erler JT, Hickman JA, Dive C. Bid, a widely expressed proapoptotic protein of the Bcl-2 family, displays lipid transfer activity. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:7268–7276. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.21.7268-7276.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Crimi M, Astegno A, Zoccatelli G, Esposti MD. Pro-apoptotic effect of maize lipid transfer protein on mammalian mitochondria. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2006;445:65–71. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2005.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Adachi J, Asano M, Yoshioka N, Nushida H, Ueno Y. Analysis of phosphatidylcholine oxidation products in human plasma using quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Kobe J Med Sci. 2006;52:127–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chen X, Sebastian BM, Tang H, McMullen MM, Axhemi A, Jacobsen DW, Nagy LE. Taurine supplementation prevents ethanol-induced decrease in serum adiponectin and reduces hepatic steatosis in rats. Hepatology. 2009;49:1554–1562. doi: 10.1002/hep.22811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Marques M, Pei Y, Southall MD, Johnston JM, Arai H, Aoki J, Inoue T, Seltmann H, Zouboulis CC, Travers JB. Identification of platelet-activating factor acetylhydrolase II in human skin. J Invest Dermatol. 2002;119:913–919. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2002.01859.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Six DA, Dennis EA. The expanding superfamily of phospholipase A(2) enzymes: classification and characterization. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1488:1–19. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(00)00105-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.McIntyre TM, Prescott SM, Stafforini DM. The emerging roles of PAF acetylhydrolase. J Lipid Res. 2009;50(Suppl):S255–259. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R800024-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Stafforini DM, Prescott SM, McIntyre TM. Human plasma platelet-activating factor acetylhydrolase. Purification and properties. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:4223–4230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hattori K, Adachi H, Matsuzawa A, Yamamoto K, Tsujimoto M, Aoki J, Hattori M, Arai H, Inoue K. cDNA cloning and expression of intracellular platelet-activating factor (PAF) acetylhydrolase II. Its homology with plasma PAF acetylhydrolase. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:33032–33038. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.51.33032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tew DG, Southan C, Rice SQ, Lawrence MP, Li H, Boyd HF, Moores K, Gloger IS, Macphee CH. Purification, properties, sequencing, and cloning of a lipoprotein-associated, serine-dependent phospholipase involved in the oxidative modification of low-density lipoproteins. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1996;16:591–599. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.16.4.591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fisher AB. Peroxiredoxin 6: A bifunctional enzyme with glutathione peroxidase and phospholipase A2 activities. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2010 doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kim SY, Chun E, Lee KY. Phospholipase A(2) of peroxiredoxin 6 has a critical role in tumor necrosis factor-induced apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 2011;18:1573–1583. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2011.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Liu J, Chen R, Marathe GK, Febbraio M, Zou W, McIntyre TM. Circulating Platelet-Activating Factor Is Primarily Cleared by Transport, Not Intravascular Hydrolysis, by Lipoprotein-Associated Phospholipase A2/PAF Acetylhydrolase. Circ Res. 2010;108:469–477. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.228742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kriska T, Marathe GK, Schmidt JC, McIntyre TM, Girotti AW. Phospholipase action of platelet-activating factor acetylhydrolase, but not paraoxonase-1, on long fatty acyl chain phospholipid hydroperoxides. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:100–108. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608135200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Stafforini DM, Sheller JR, Blackwell TS, Sapirstein A, Yull FE, McIntyre TM, Bonventre JV, Prescott SM, Roberts LJ., 2nd Release of free F2-isoprostanes from esterified phospholipids is catalyzed by intracellular and plasma platelet-activating factor acetylhydrolases. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:4616–4623. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M507340200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Nichols JW. Internalization and trafficking of fluorescent-labeled phospholipids in yeast. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2002;13:179–184. doi: 10.1016/s1084-9521(02)00046-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Greenberg ME, Li XM, Gugiu BG, Gu X, Qin J, Salomon RG, Hazen SL. The lipid whisker model of the structure of oxidized cell membranes. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:2385–2396. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707348200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]