Abstract

Objective

To determine if visual field (VF) loss from glaucoma is associated with greater fear of falling.

Design

Prospective observational study.

Participants

Fear of falling was compared between 83 glaucoma subjects with bilateral VF loss, and 60 control subjects with good visual acuity and without significant VF loss recruited from patients followed for suspicion of glaucoma.

Methods

Participants completed the University of Illinois at Chicago Fear of Falling Questionnaire. The extent of fear of falling was assessed using Rasch analysis.

Main Outcome Measures

Subject ability to perform tasks without fear of falling was expressed in logits, with lower scores implying less ability and greater fear of falling.

Results

Glaucoma subjects had greater VF loss than control subjects (median better-eye mean deviation (MD) of −8.0 decibels [dB] vs. +0.2 dB, p<0.001), but did not differ with regards to age, race, gender, employment status, the presence of other adults in the home, body mass index (BMI), grip strength, cognitive ability, mood, or comorbid illness (p≥0.1 for all).

In multivariable models, glaucoma subjects reported greater fear of falling as compared to controls (β= −1.20 logits; 95% Confidence Interval [CI] = −1.87 to −0.53; p=0.001), and fear of falling increased with greater VF loss severity (β= −0.52 logits per 5 dB decrement in the better eye VF MD; 95% CI = −0.72 to −0.33; p<0.001). Other variables predicting greater fear of falling included female gender (β= −0.55 logits; 95% CI = −1.03 to −0.06; p=0.03), higher BMI (β= −0.07 logits per 1 unit increase in BMI; 95% CI = −0.13 to −0.01; p=0.02), living with another adult (β= −1.16 logits; 95% CI = −0.34 to −1.99 logits; p=0.006), and greater comorbid illness (β= −0.53 logits/1 additional illness; 95% CI = −0.74 to −0.32; p<0.001).

Conclusions

Bilateral VF loss from glaucoma is associated with greater fear of falling, with an impact that exceeds numerous other risk factors. Given the physical and psychological repercussions associated with fear of falling, significant quality of life improvements may be achievable in patients with VF loss by screening for, and developing interventions to minimize, fear of falling.

INTRODUCTION

Falls are the leading cause of injury-related death in the elderly, accounting for the nearly 3 times as many deaths as motor vehicle accidents.1 Visual field (VF) loss from glaucoma is associated with a higher risk of falling,2,3 and nearly half of those with glaucoma fall over the course of a year.4 Additionally, glaucoma is associated with higher rates of injurious falls and fractures.4,5

Falls also exert a tremendous psychological impact on the individual because of a change in their perception of capability. Fear of falling is a widely used metric which captures this impact and is considered an important health outcome,6 even in individuals who have not had a recent fall.7 Several questionnaires have been used to measure fear of falling,8 and greater fear of falling is associated with decreased physical activity, loss of independence, reduction of social activity, lower quality of life, and depression.9–13

While the association of falls with visual acuity and VF loss has been examined in several studies, few studies have examined fear of falling amongst individuals with visual limitations. Additionally, many of these studies did not formally test visual function. Fear of falling was assessed prospectively in the Beaver Dam Eye Study through a single question, and individuals with a baseline best-corrected visual acuity of 20/40 or worse had a nearly 3-fold increase in incident fear of falling.14 Fear of falling in glaucoma was also assessed in a single study, though again was assessed with only a single question.15 Here, we use a previously-validated questionnaire16 to test the hypothesis that glaucoma, which is associated with worse balance and more falls, 17 is also associated with greater fear of falling.

METHODS

The study protocol was approved by the Johns Hopkins Medicine Institutional Review Board. All study participants signed written informed consent and participated in the study between July 2009 and June 2011.

Enrollment Criteria

Subjects were recruited from a convenience sample of patients receiving care at the Johns Hopkins Wilmer Eye Institute. Individuals were between age 60 and 80, and met additional criteria qualifying them for either the glaucoma suspect (control) or glaucoma group. Control subjects also satisfied all three of the following criteria: (1) a physician diagnosis of ocular hypertension or glaucoma suspect based on optic nerve and VF findings, (2) an Early Treatment of Diabetic Retinopathy Study (ETDRS) presenting acuity ≥ 20/40 in each eye, and (3) VF testing that demonstrated a mean deviation (MD) better than −5 decibels (dB) in both eyes, a MD better than −3 dB in at least 1 eye, and glaucoma hemifield test (GHT) results of “within normal limits”, “borderline”, or “general reduction of sensitivity” in both eyes. Other GHT results were accepted in VF tests classified as “low test reliability” or “excessively high false positives” as long as MD criteria were still met. Glaucoma subjects also satisfied all 3 of the following criteria: (1) a physician diagnosis of primary open angle glaucoma, primary angle closure glaucoma, pseudoexfoliation glaucoma, or pigment dispersion glaucoma based on optic nerve, VF, and anterior segment assessment, (2) a better-eye VF MD ≤-3 dB in both eyes, and (3) a GHT result of “outside normal limits”, “borderline”, or “generalized reduction of sensitivity” in both eyes. No subject was included in either group include who had: (1) ocular laser treatment in the previous week, (2) non-ocular surgery or hospitalization in the past 2 weeks, or (3) eye surgery in the past 2 months.

VF parameters were derived from Swedish Interactive Testing Algorithm (SITA) standard 24-2 tests performed over the past 12 months on a Humphrey Field Analyzer II perimeter (Carl Zeiss Meditec, Dublin CA). The better-seeing eye was defined as the eye with the higher (less negative) mean deviation (MD). In some glaucoma patients, recent VF testing in one or both eyes was a 10-2 test. If the most recent VF test was a 10-2 in only one eye, the better-eye MD was taken from the results of the 24-2 test performed in the other eye. If the most recent VF test was a 10-2 in both eyes, the last 24-2 test was for each eye was identified, and the better-eye was defined as the eye with the higher VF MD taken from these 24-2 tests.

Evaluation of Fear of Falling

Fear of falling was evaluated using a previously validated questionnaire.16 Questionnaires were administered orally to subjects during an in-person interview. Subjects were asked about how much fear they would have if they were to perform any of 16 different tasks, regardless of whether these tasks were performed recently or not. Four possible responses were accepted for each question: “Not worried”, “A little worried”, “Moderately worried”, or “Very worried”. “Moderately worried” or “A little worried” were combined into a single category as previously described.16

Evaluation of Vision and Health

Right and left eye visual acuities were determined using a back-lit ETDRS charts at either 1 or 4 meters. Acuities were measured with subjects wearing their habitual correction, which is most likely to reflect their function in daily life. Better-eye acuity was transformed to the logarithm of the minimum angle of resolution (logMAR) for analysis.18 Eyes with visual acuities of count fingers and hand motions or worse were assigned logMAR acuities of 1.8 and 2.3 respectively, corresponding to being able to read the top line of the ETDRS chart at either 63 cm or 20 cm.19 Contrast sensitivity was evaluated under binocular conditions using Pelli-Robson charts at 1 meter, and expressed in log units as previously described.20

Standardized questionnaires were used to evaluate several variables potentially confounding the relationship between VF loss and fear of falling. Collected personal and anthropomorphic information included age, gender, race, height and weight. Comorbid illnesses were evaluated using a standardized questionnaire.21 Depressive symptoms were evaluated with the Short Form of the Geriatric Depression Scale, with symptoms defined as present with scores ≥5.22 Cognitive ability was assessed with the visually impaired version of the Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE).23

Grip strength was assessed using a Jamar hand dynamometer (Sammons Preston, Inc., Bolingbrook, IL) with strength recorded in kilograms of force. Subjects were asked to use their dominant hand to squeeze as hard as possible, and the mean of three consecutive trials was taken as the measure of grip strength. Height and weight were directly measured and used to calculate body mass index (BMI).

Both eyes were directly examined after pupillary dilation to evaluate for significant lenticular changes, defined by any of the following: (1) Nuclear sclerosis greater than grade 2 on the Wilmer Cataract Grading system,24 (2) blocked retroillumination in ≥ 4/16th of the pupil due to cortical changes,25 (3) any opacity in the central 3 mm of the posterior capsule, or (4) posterior capsular opacification (PCO) in pseudophakic eyes demonstrating changes more than the mild image displayed in Findl et al.26

Statistical Methods

Group differences were evaluated using chi squared analyses for categorical variables, and either t-test or Wilcoxon rank-sum test for continuous variables. Rasch analysis was performed using Winsteps (Winsteps, Chicago, IL) in order to estimate linear item measure scores for each task and linear person measure scores for each study participant from their responses to the individual fear of falling questions. Both item measure scores and person measure scores are expressed in a log-odds metric, or logits, along the same scale. The zero value of the scale is defined by the average challenge of the included item measures. Higher item scores reflect more difficult tasks which can be performed without fear of falling only by individuals of greater ability (those with greater person measure scores). Lower item scores represent easier tasks which only elicit fear of falling in individuals with less ability (those with lesser person measure scores).

Factors influencing the overall likelihood of fear of falling were first evaluated in age and comorbidity-adjusted linear regression models using the Rasch model estimated person measure scores (in logit units) as the dependent variable. Age was included in these preliminary analyses because of the strong association of fear of falling with older age,8 while comorbidity was included to remove skewing of model residuals and allow the use of linear regression. Multivariable analyses were conducted using reverse stepwise regression with an inclusion cutoff of p<0.1. Age, gender, race, comorbidity and the relevant metric(s) of vision loss were fixed as model covariates. Post-Rasch analyses were performed using STATA 11 (College Station, Texas).

RESULTS

Sixty control subjects and 83 glaucoma subjects enrolled in the study, and all enrolled subjects completed the fear of falling questionnaire. Control and glaucoma subjects did not significantly differ in age, racial distribution, gender, education level, employment status, or the likelihood of living alone (p>0.05 for all) (Table 1). Measures of non-visual health were also similar across groups, with glaucoma subjects demonstrating a similar BMI, grip strength, number of comorbid illnesses, frequency of depressive symptoms, and cognitive ability as compared to controls (p>0.05 for all). Glaucoma subjects had greater VF damage than controls, with a median better eye MD of −8.0 dB (Interquartile range [IQR]= −16.5 to −4.8 dB) vs. +0.2 dB for controls (IQR= −0.6 to +0.9 dB; p<0.001). Median worse eye MD was −16.7 dB for glaucoma subjects (IQR= −10.4 to −24 dB) as compared to −0.7 dB (IQR= −0.1 to −1.5 dB) for controls (p<0.001). Glaucoma subjects also had lower contrast sensitivity (median log contrast sensitivity = 1.50, IQR=1.35 to 1.75 vs. median of 1.85, IQR=1.80 to 1.95; p<0.001), and worse logMAR visual acuity in the better eye (median=0.16, IQR=0.08 to 0.34 vs. median=0.08, IQR=0 to 0.16; p<0.001). Unilateral, but not bilateral, cataract/PCO was more common amongst glaucoma subjects.

Table 1.

Characteristics of interviewed subjects by glaucoma status.

| No glaucoma (n=60) | Glaucoma (n=83) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vision | |||

| Visual field MD (better eye)* | 0.2 | −8.0 | <0.001 |

| Better-eye Acuity, logMAR* | 0.08 | 0.16 | <0.001 |

| Binocular log CS* | 1.85 | 1.50 | <0.001 |

| Sig. cataract/PCO, either eye (%) | 23.2 | 37.4 | 0.08 |

| Sig. cataract/PCO, both eyes (%) | 10.7 | 14.5 | 0.52 |

| Demographics | |||

| Age (Years) | 69.5 | 70.4 | 0.28 |

| African-American Race (%) | 20.0 | 32.5 | 0.10 |

| Female Gender (%) | 61.7 | 53.0 | 0.30 |

| Education (years) | 15.3 | 14.7 | 0.23 |

| Employed (%) | 38.3 | 42.2 | 0.65 |

| Lives alone (%) | 18.3 | 19.3 | 0.89 |

| Health | |||

| Body Mass Index | 28.5 | 28.3 | 0.79 |

| Grip strength (kg) | 27.5 | 29.3 | 0.26 |

| Comorbid illnesses (#) | 2.5 | 2.2 | 0.27 |

| Depressive symptoms (%) | 5.0 | 6.2 | 0.79 |

| MMSE-VI score | 20.8 | 20.5 | 0.39 |

Indicates median values.

MD = mean deviation, logMAR = logarithm of the minimum angle of resolution; CS = Contrast sensitivity; PCO = Posterior Capsular Opacification; Sig. = Significant; MMSE-VI = Mini-mental status examination for the visually impaired

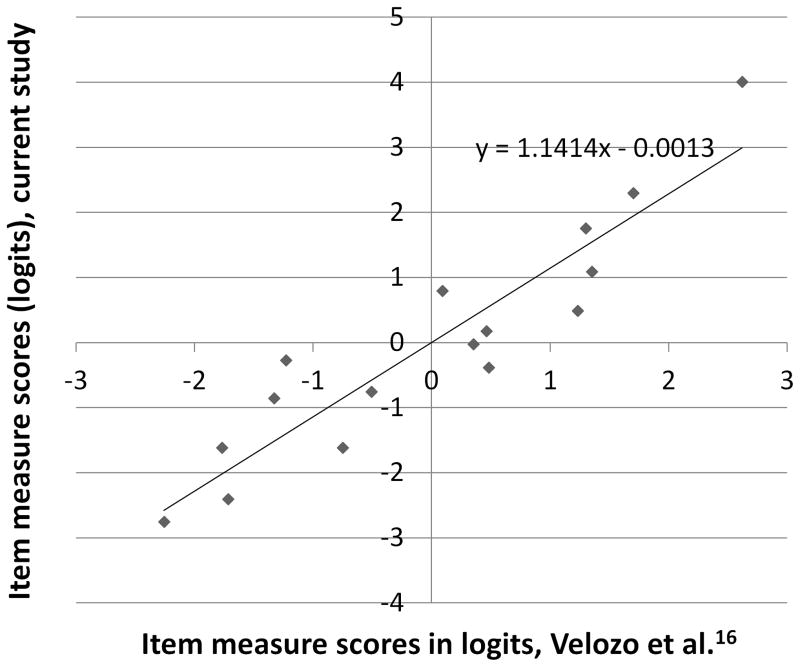

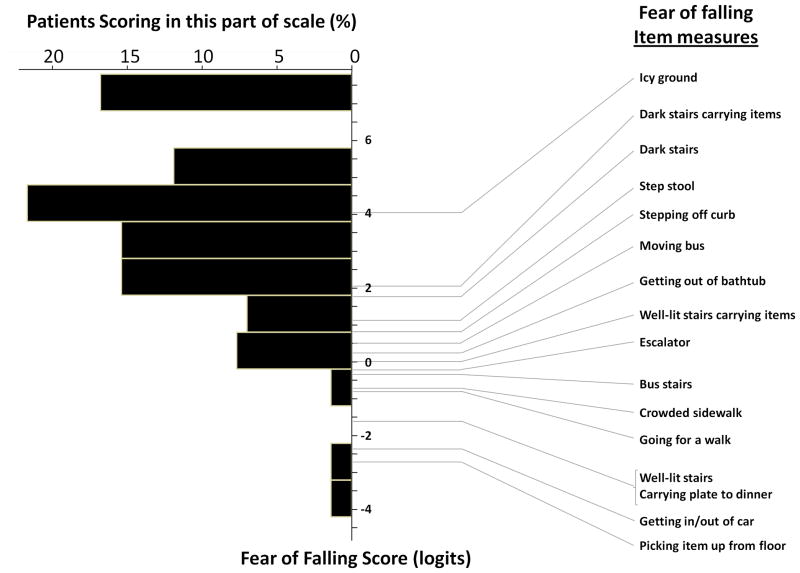

A Rasch model was constructed to estimate scores reflecting how much fear of falling was associated with each task (item measure scores), and how much fear of falling each study subject had with the tasks evaluated (person measure scores). Higher item measure scores reflect greater task difficulty, and greater fear of falling associated with that item. Higher person measure scores indicate the ability to perform more difficult tasks (i.e. those with higher item measure scores) without fear of falling. Lower person measure scores reveal that only simpler tasks (with lower item measure scores) can be performed without fear, implying greater fear of falling. Item and person measure reliabilities were 0.82 and 0.95, respectively, indicating that 82% and 95% of the variance in item and person measure scores were attributable to true differences in the items or people, and not estimation error. A high correlation (R2=0.86) was observed between the item measure scores obtained in the current study and scores derived from the original validation sample described by Velozo et al. (Figure 1).16 The item measure scores associated with the tasks evaluated, and the distribution of person measure scores with regards to these person measures is shown in Figure 2.

FIGURE 1.

Comparison of item measure scores derived from the current study and from the original validation sample.

FIGURE 2.

Distribution of fear of falling item measure and person measure scores.

Fear of falling item and person measure scores are mapped to the same scale. Lower person measure scores indicate greater fear of falling in the individual, while lower item measure scores indicate less task difficulty. Item measure scores are found at the midpoint of the modeled no fear to little/moderate fear and little/moderate to severe fear transition points.

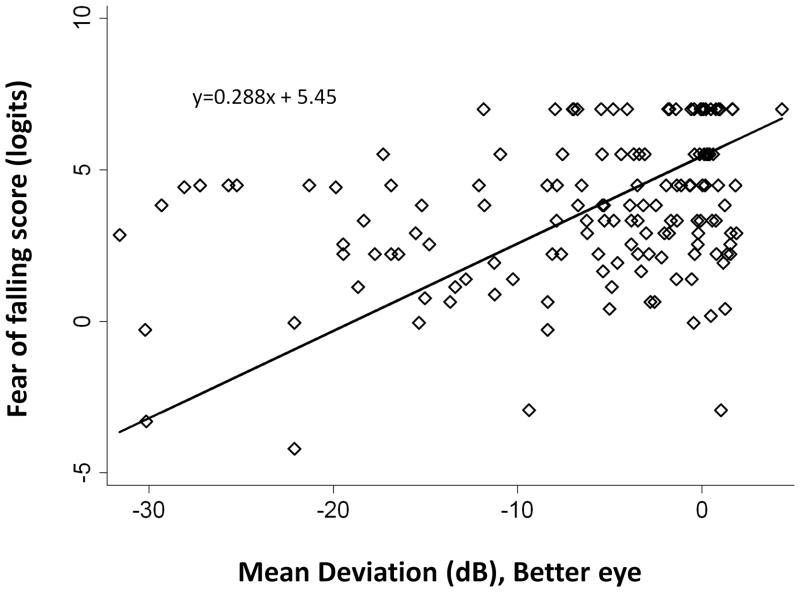

Variables predicting fear of falling person measure scores were first assessed in linear regression models adjusting for age and comorbid illness (Table 2). Glaucoma was associated with greater fear of falling (β= −1.02 logits; 95% Confidence Interval [CI]= −1.75—0.30; p=0.006), and greater fear of falling was found with more severe VF loss (Figure 3). Additional factors predicting fear of falling in models adjusting for age and comorbid illness included female gender, lower grip strength, and depressive symptoms (p<0.001 for all). Comorbid illness was also associated with greater fear of falling after adjusting for age (p<0.001).

Table 2.

Predictors of fear of falling, adjusted for age and comorbid illness

| Variable | Interval | Δ Fear of Falling score (logit units)* | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vision | |||

| Glaucoma | Present | −1.02 | 0.006 |

| VF loss MD, bettereye | 5 dB worse | −0.47 | <0.001 |

| Contrast Sensitivity | 0.1 log units worse | −0.16 | <0.001 |

| VA, better eye | 0.1 logMAR worse | −0.15 | 0.01 |

| Cataract/PCO | Present, either eye | −0.43 | 0.29 |

| Demographics | |||

| Gender | Female vs. Male | −0.73 | <0.001 |

| Employed | Yes | +0.62 | 0.12 |

| Lives alone | Yes | +0.70 | 0.14 |

| Age | 5 years older | +0.03 | 0.86 |

| Education | 4 years more | +0.38 | 0.14 |

| Race | African-American | +0.09 | 0.83 |

| Health | |||

| Grip Strength | 1 kg more force | +0.08 | <0.001 |

| Comorbidities | 1 more illness | −0.57 | <0.001 |

| Depressive symptoms | Present | −3.28 | <0.001 |

| MMSE-VI score | 5 points lower | −0.51 | 0.39 |

| Body mass index | 1 higher | −0.03 | 0.44 |

Scores are derived from Rasch analytic model. Higher scores indicate greater ability, or less fear of falling. Therefore, factors associated with a negative change in score are associated with greater fear of falling.

VF – Visual field; MD = Mean deviation; dB – decibels; VA – visual acuity; logMAR – Logarithm of the minimum angle or resolution; PCO = Posterior capsule opactification; MMSE-VI – Mini-mental state exam for the visual impaired

FIGURE 3.

Fear of falling levels by severity of visual field loss.

Lower fear of falling scores indicate greater fear of falling, evidenced by fear with easier tasks. The relationship between fear of falling scores and better-eye mean deviation is plotted as a linear relationship using bivariate regression.

Predictors of fear of falling were further investigated using multivariable linear regression models with Rasch-estimated person measure scores as the dependent variable (Table 3). Significantly more fear of falling was present in subjects with glaucoma as compared to subjects without glaucoma (β= −1.20 logits; 95% CI= −1.87 to −0.53; p=0.001). In separate multivariable models, more fear of falling occurred with greater VF damage (β= −0.52 logits per 5 dB decrement in the better-eye VF MD; 95% CI = −0.72 to −0.33; p<0.001), lower contrast sensitivity (β= −0.17 per 0.1 unit lower log contrast sensitivity; 95% CI = −0.09 to −0.25; p<0.001), and worse visual acuity (β= −0.14 logits per 0.1 logMAR increment; 95% CI = −0.25 to −0.03; p=0.02). Additional variables predictive of greater fear of falling in multivariable models included female gender, more severe comorbid illness, higher BMI and living with another (p<0.05 for all). When the presence of cataract/PCO was added to multivariable models, the association of glaucoma and greater fear of falling remained (β= −1.30, p<0.001). When severity of VF loss, contrast sensitivity, and visual acuity were all included in a single model, VF loss remained a significant predictor of fear of falling (p=0.01), while contrast sensitivity and acuity were no longer significant predictors (p>0.3 for both).

Table 3.

Predictors of fear of falling, multivariable analysis

| Variable | Interval | Δ Fear of Falling score (logit units)* | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vision** | |||

| Glaucoma | Present | −1.20 | 0.001 |

| VF loss MD, bettereye | 5 dB worse | −0.52 | <0.001 |

| Contrast Sensitivity | 0.1 log units worse | −0.43 | <0.001 |

| VA, better eye | 0.1 logMAR worse | −0.14 | 0.02 |

| Non-vision*** | |||

| Comorbidities | 1 more illness | −0.53 | <0.001 |

| Lives alone | Yes | +1.16 | 0.006 |

| Body mass index | 1 higher | −0.07 | 0.02 |

| Gender | Female vs. Male | −0.55 | 0.03 |

| Grip Strength | 1 kg more force | +0.04 | 0.08 |

| Race | African-American | +0.45 | 0.24 |

| Age | 5 years older | −0.07 | 0.68 |

Scores are derived from Rasch analytic model. Higher scores indicate greater ability, or less fear of falling. Therefore, factors associated with a negative change in score are associated with greater fear of falling.

Coefficients for vision variables were each derived from separate multivariable models including all non-visual covariates shown.

Coefficients for non-vision variables were all derived from a single multivariable model including better-eye MD and all non-visual Variables shown

VF – Visual field; MD = Mean deviation; dB – decibels; VA – visual acuity; logMAR – Logarithm of the minimum angle or resolution; MMSE-VI – Mini-mental state exam for the visual impaired

DISCUSSION

Our study is the first to characterize fear of falling in vision loss through the use of validated questionnaire. While previous research suggested that glaucoma was not related to fear of falling on the basis of a single question, our results suggest that glaucoma is associated with greater fear of falling, and that fear of falling is more severe with greater VF loss. Fear of falling remained associated with VF loss severity even after adjusting for decreased visual acuity, suggesting that multiple forms of visual impairment may produce fear of falling.14

Previous falls are a significant risk factor for fear of falling,8 and several papers have suggested that glaucoma increases the risk of actual falls.2,3 However, most of these studies evaluated falls retrospectively, and falls were not evaluated in this cross-sectional study given that retrospective falls assessment correlates poorly with prospective fall documentation.27 One recent publication evaluated falls prospectively in a group of glaucoma patients and found that nearly one-half had fallen during a year of follow-up, with fall risk increasing significantly with the degree of VF loss.4 Additionally, fear of falling frequently occurs independently of a fall, suggesting that fear of falling is not purely a side effect of falls.28 Fear of falling is associated with avoidance of activity,9 reduction of social activity,10 and depression.11 Greater fear of falling also predicts future loss of independence12 and future decreases in quality of life measures,13 making it an important aspect of health to be addressed independent of falls.

Fear of falling is a plausible intermediary in the pathway between glaucomatous VF loss and decreased health and well-being. Glaucoma is associated with decreased balance29 and a greater likelihood of bumping into objects while walking.30 These deficits likely contribute towards fear of falling either directly or as a result of a fall. Fear of falling, in turn, may explain the slower walking speeds observed in glaucoma15,30 and lead to restriction of physical activity and travel outside the home,31,32 resulting in decreased independence and lower quality of life.33,34

Our analyses revealed several other factors associated with greater fear of falling, including female gender, decreased strength, and higher BMI. These findings corroborate the results of previous studies describing risk factors for fear of falling in the elderly population.6,8 Age has been associated with fear of falling in numerous other studies8 but was not a risk factor here, possibly because only subjects over a relative narrow range of ages were studied. Living alone was associated with less fear of falling in the current study, possibly reflecting the need for individuals with greater fear of falling to live with another for support. Finally, an increased number of comorbid illnesses was associated with greater fear of falling, though the impact of each additional comorbid illness was less than one-half the impact of glaucoma (−0.53 vs −1.20 logits). These findings suggest that the increase in fear of falling associated with bilateral glaucoma is large and clinically significant.

There is active research in the geriatrics community to develop methods for preventing falls and reducing fear of falling35 but, to our knowledge, no clinical trials have focused on reducing falls and/or fear of falling in the visually impaired. In-clinic low vision services cannot and do not address mobility extensively. Fear of falling may be addressed by orientation and mobility services, but how well these services address falls or fear of falling is unknown. Additionally, orientation and mobility services are not always available, and are likely underutilized even when available. Given the significant levels of fear of falling observed in this study, more effort is required to make decreasing fear of falling a therapeutic goal in the care of glaucoma patients, particularly among patients with advanced bilateral disease.

Fear of falling was studied here using a previously-developed Rasch analytic model.16 The use of Rasch analysis allowed for objective scaling of questionnaire responses, unlike other approaches which give equal weight to questions evaluating fear during tasks of varying difficulty.9,36 The questionnaire used here was originally validated for a general elderly population, but also functioned well in our study population, demonstrating good reliability with regards to both person measure and item measure scores. Additionally, the relative degree of fear of falling associated with various tasks estimated from our results agreed with those previously reported,16 suggesting that the settings in which individuals with glaucoma experience fear of falling are similar to those that elicit fear in the general elderly population. As such, the current questionnaire represents a good choice for additional studies looking at fear of falling in older adults with vision loss.

One limitation of the current study is that participation may have been biased towards individuals with greater ability. Indeed, nearly half the individuals in each study group were employed, despite a mean age of 70. While attempts were made to perform study procedures on the same day as a clinical visit, it did require either an extra trip to the clinic and/or extra time in the clinic, which may have placed a heavier burden on those with greater fear of falling, thus discouraging participation. Additionally, subjects were recruited from a large tertiary care center which individuals with fear of falling may be less likely to attend due to fears of urban driving and/or the need to walk considerable distances from the parking lot to the clinic. Also, all individuals knew about their disease, which may bias individuals with greater levels of VF loss towards reporting greater fear of falling. However, individuals in this same study also demonstrated impairment of mobility in several objective measures, including how much physical activity they performed and how much they left their home.31,32 Furthermore, controls subjects were taken from glaucoma suspects, and not individuals with normal eyes, such that all subjects knew that had some level of glaucoma. While the choice of glaucoma suspects as a control group may have led us to underestimate the impact of VF loss from glaucoma on fear of falling, the minimal amount of VF loss in the control group (mean better-eye VF MD of 0.0 dB) suggests that this bias is unlikely to be significant.

Glaucoma has a significant impact on fear of falling even at levels where individuals would not be classified as “blind”. Additionally, fear of falling is substantially higher with modest steps of disease severity, with each 5 dB decrement in the better-eye VF associated with an increase in fear of falling comparable to 1 additional comorbid illness. The social, psychological, and physical consequences of fear of falling are substantial and well-documented,6,8 suggesting that fear of falling may be an important factor linking glaucoma to decreased quality of life. Better patient care of glaucoma patients can be achieved through the development, validation, and implementation of methods to address fear of falling in this at-risk population.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: This work was supported by the Dennis W. Jahnigen Memorial Award, NIH Grant EY018595, the Research to Prevent Blindness Robert and Helen Schaub Special Scholar Award, and the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Institute on Aging. All funding organizations had no role in the design or conduct of this research.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: No conflict of interest for any author.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Injury prevention and control. Table 10. [Accessed October 19, 2011];Leading Causes of Injury Deaths by Age Group Highlighting Unintentional Injury Deaths, United States–2007. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/pdf/Unintentional_2007-a.pdf.

- 2.Lamoureux EL, Chong E, Wang JJ, et al. Visual impairment, causes of vision loss, and falls: the Singapore Malay Eye Study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49:528–33. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haymes SA, Leblanc RP, Nicolela MT, et al. Risk of falls and motor vehicle collisions in glaucoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:1149–55. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Black AA, Wood JM, Lovie-Kitchin JE. Inferior field loss increases rate of falls in older adults with glaucoma. Optom Vis Sci. 2011;88:1275–82. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0b013e31822f4d6a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Colon-Emeric CS, Biggs DP, Schenck AP, Lyles KW. Risk factors for hip fracture in skilled nursing facilities: who should be evaluated? Osteoporos Int. 2003;14:484–9. doi: 10.1007/s00198-003-1384-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Legters K. Fear of falling. Phys Ther. 2002;82:264–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jorstad EC, Hauer K, Becker C, et al. Measuring the psychological outcomes of falling: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:501–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53172.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scheffer AC, Schuurmans MJ, van Dijk N, et al. Fear of falling: measurement strategy, prevalence, risk factors and consequences among older persons. Age Ageing. 2008;37:19–24. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afm169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lachman ME, Howland J, Tennstedt S, et al. Fear of falling and activity restriction: the survey of activities and fear of falling in the elderly (SAFE) J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 1998;53:P43–50. doi: 10.1093/geronb/53b.1.p43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tinetti ME, Mendes de Leon CF, Doucette JT, Baker DI. Fear of falling and fall-related efficacy in relationship to functioning among community-living elders. J Gerontol. 1994;49:M140–7. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.3.m140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arfken CL, Lach HW, Birge SJ, Miller JP. The prevalence and correlates of fear of falling in elderly persons living in the community. Am J Public Health. 1994;84:565–70. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.4.565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yardley L, Smith H. A prospective study of the relationship between feared consequences of falling and avoidance of activity in community-living older people. Gerontologist. 2002;42:17–23. doi: 10.1093/geront/42.1.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cumming RG, Salkeld G, Thomas M, Szonyi G. Prospective study of the impact of fear of falling on activities of daily living, SF-36 scores, and nursing home admission. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2000;55:M299–305. doi: 10.1093/gerona/55.5.m299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klein BE, Moss SE, Klein R, et al. Associations of visual function with physical outcomes and limitations 5 years later in an older population: the Beaver Dam Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 2003;110:644–50. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(02)01935-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Turano KA, Rubin GS, Quigley HA. Mobility performance in glaucoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1999;40:2803–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Velozo CA, Peterson EW. Developing meaningful fear of falling measures for community dwelling elderly. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2001;80:662–73. doi: 10.1097/00002060-200109000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ramulu P. Glaucoma and disability: which tasks are affected, and at what stage of disease? Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2009;20:92–8. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0b013e32832401a9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bailey IL, Bullimore MA, Raasch TW, Taylor HR. Clinical grading and the effects of scaling. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1991;32:422–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lange C, Feltgen N, Junker B, et al. Resolving the clinical acuity categories “hand motion” and “counting fingers” using the Freiburg Visual Acuity Test (FrACT) Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2009;247:137–42. doi: 10.1007/s00417-008-0926-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Elliott DB, Bullimore MA, Bailey IL. Improving the reliability of the Pelli-Robson contrast sensitivity test. Clin Vis Sci. 1991;6:471–5. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Turano KA, Broman AT, Bandeen-Roche K, et al. SEE Project Team. Association of visual field loss and mobility performance in older adults: Salisbury Eye Evaluation Study. Optom Vis Sci. 2004;81:298–307. doi: 10.1097/01.opx.0000134903.13651.8e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Montorio I, Izal M. The Geriatric Depression Scale: a review of its development and utility. Int Psychogeriatr. 1996;8:103–12. doi: 10.1017/s1041610296002505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Busse A, Sonntag A, Bischkopf J, et al. Adaptation of dementia screening for vision-impaired older persons: administration of the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) J Clin Epidemiol. 2002;55:909–15. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(02)00449-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.West SK, Munoz B, Schein OD, et al. Racial differences in lens opacities: the Salisbury Eye Evaluation (SEE) Project. Am J Epidemiol. 1998;148:1033–9. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.West SK, Munoz B, Wang F, Taylor H. Measuring progression of lens opacities for longitudinal studies. Curr Eye Res. 1993;12:123–32. doi: 10.3109/02713689308999480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Findl O, Buehl W, Menapace R, et al. Comparison of 4 methods for quantifying posterior capsule opacification. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2003;29:106–11. doi: 10.1016/s0886-3350(02)01509-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cummings SR, Nevitt MC, Kidd S. Forgetting falls: the limited accuracy of recall of falls in the elderly. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1988;36:613–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1988.tb06155.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Suzuki M, Ohyama N, Yamada K, Kanamori M. The relationship between fear of falling, activities of daily living and quality of life among elderly individuals. Nurs Health Sci. 2002;4:155–61. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-2018.2002.00123.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Black AA, Wood JM, Lovie-Kitchin JE, Newman BM. Visual impairment and postural sway among older adults with glaucoma. Optom Vis Sci. 2008;85:489–97. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0b013e31817882db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Friedman DS, Freeman E, Munoz B, et al. Glaucoma and mobility performance: the Salisbury Eye Evaluation Project. Ophthalmology. 2007;114:2232–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ramulu PY, Hochberg C, Maul E, et al. Objective quantification of travel away from home in glaucoma using a cellular tracking device. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. In press. AQ: cite as unpublished or provide confirmation from journal. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ramulu PY, Maul E, Hochberg C, et al. Real-world assessment of physical activity in glaucoma using an accelerometer. Ophthalmology. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.01.013. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Freeman EE, Munoz B, West SK, et al. Glaucoma and quality of life: The Salisbury Eye Evaluation. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:233–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.04.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McKean-Cowdin R, Wang Y, Wu J, et al. Los Angeles Latino Eye Study Group. Impact of visual field loss on health-related quality of life in glaucoma: the Los Angeles Latino Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:941–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.08.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kwok BC, Mamun K, Chandran M, Wong CH. Evaluation of the Frails’ Fall Efficacy by Comparing Treatments (EFFECT) on reducing fall and fear of fall in moderately frail older adults: study protocol for a randomised control trial. [Accessed January 19, 2012];Trials [serial online] 2011 12:155. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-12-155. Available at: http://www.trialsjournal.com/content/12/1/155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tinetti ME, Richman D, Powell L. Falls efficacy as a measure of fear of falling. J Gerontol. 1990;45:239–43. doi: 10.1093/geronj/45.6.p239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]