Abstract

Disruption of the circadian clock exacerbates metabolic diseases including obesity and diabetes. Here we show that histone deacetylase 3 (HDAC3) recruitment to the genome displays a circadian rhythm in mouse liver. Histone acetylation is inversely related to HDAC3 binding, and this rhythm is lost when HDAC3 is absent. Although amounts of HDAC3 are constant, its genomic recruitment in liver corresponds to the expression pattern of the circadian nuclear receptor Rev-erbα. Rev-erbα colocalizes with HDAC3 near genes regulating lipid metabolism, and deletion of HDAC3 or Rev-erbα in mouse liver causes hepatic steatosis. Thus, genomic recruitment of HDAC3 by Rev-erbα directs a circadian rhythm of histone acetylation and gene expression required for normal hepatic lipid homeostasis.

In mammals, metabolic processes in peripheral organs display robust circadian rhythms, coordinated with the daily cycles of light and nutrient availability (1, 2). Circadian misalignment causes metabolic dysfunction, and people engaged in night-shift work suffer from higher incidences of obesity, diabetes, and metabolic syndrome (3–5). The molecular basis of this is unknown, but genetic disruption of circadian clock components in mice leads to altered glucose and lipid metabolism (6–10).

Gene expression profiles in multiple metabolic organs have revealed a circadian control of the transcriptome, which might be mediated by regulation of histone acetylation (11–13) that alters the structure of the epigenome. Regulation of histone acetylation is complex, involving multiple histone acetyltransferase (HATs) and histone deacetylases (HDACs)(14). Histone deacetylase 3 (HDAC3) functions in the regulation of circadian rhythm and glucose metabolism (15). Here we report diurnal recruitment of HDAC3 to the mouse liver genome detected by chromatin immunoprecipitation with an HDAC3-specific antibody (Supp. Fig. 1) and massively parallel DNA sequencing (ChIP-seq).

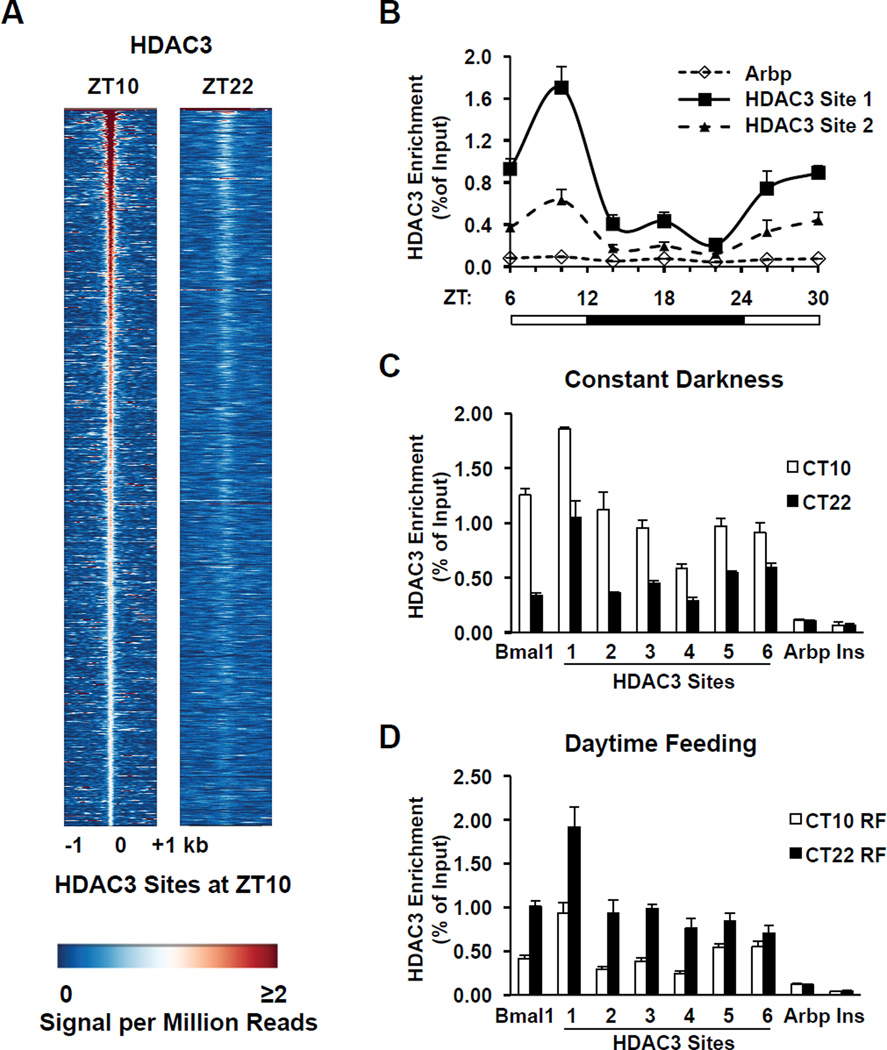

At ZT10, in the light period when mice are inactive, HDAC3 bound to over 14,000 sites in adult mouse liver (the HDAC3 ZT10 cistrome)(Supp. Fig. 2A); a majority of these binding sites were distant from transcription start sites (TSS) or present in introns (Supp. Figs. 2B and C). However, at ZT22, in the dark period when mice are active and feeding, the HDAC3 signal was dramatically reduced at ZT10 sites, with only 120 specific peaks (Fig. 1A; Supp. Figs. 2A, 2D, and 3). HDAC3 recruitment oscillated in a 24h cycle (Fig. 1B), and this rhythm was retained in constant darkness (Fig. 1C), suggesting that it was controlled by the circadian clock. The liver clock is entrained by food intake (16) and, indeed, the pattern of HDAC3 enrichment was reversed when food was provided only during the light period (Fig. 1D), further supporting the conclusion that the rhythm of HDAC3 genomic recruitment was controlled by the circadian clock.

Figure 1. Circadian rhythm of genomic HDAC3 recruitment in mouse liver.

A. Heatmap of HDAC3 binding signal at ZT10 (left) and ZT22 (right) from −1kb to +1kb surrounding the center of all the HDAC3 ZT10 binding sites, ordered by strength of HDAC3 binding at ZT10. ChIP-Seq with anti-HDAC3 antibody was performed and data were analyzed as described in Methods. Each line represents a single HDAC3 binding site and the color scale indicates the HDAC3 signal (reads encompassing each locus per million total reads). A read is a unique sequence obtained in ChIP-Seq and then aligned to the mouse genome. ZT, Zeitgeber time (light-on at ZT0, off at ZT12). B. HDAC3 recruitment at 2 selected genomic sites over a 24h cycle by ChIP-PCR. Immunoprecipitated DNA was normalized to input. Values are mean ± s.e.m. (n=4–5). C. HDAC3 diurnal genomic recruitment is maintained in constant darkness. Six HDAC3 binding sites were assessed by ChIP-PCR (n=4–5), and the Bmal1 promoter served as a positive control (23); regions close to the TSS of the Arbp and Ins genes served as negative controls. CT, Circadian time. D. The rhythm of HDAC3 recruitment is reversed by day-time feeding (n=4–5). RF, food was provided only from ZT3 to ZT11 every day for 2 weeks.

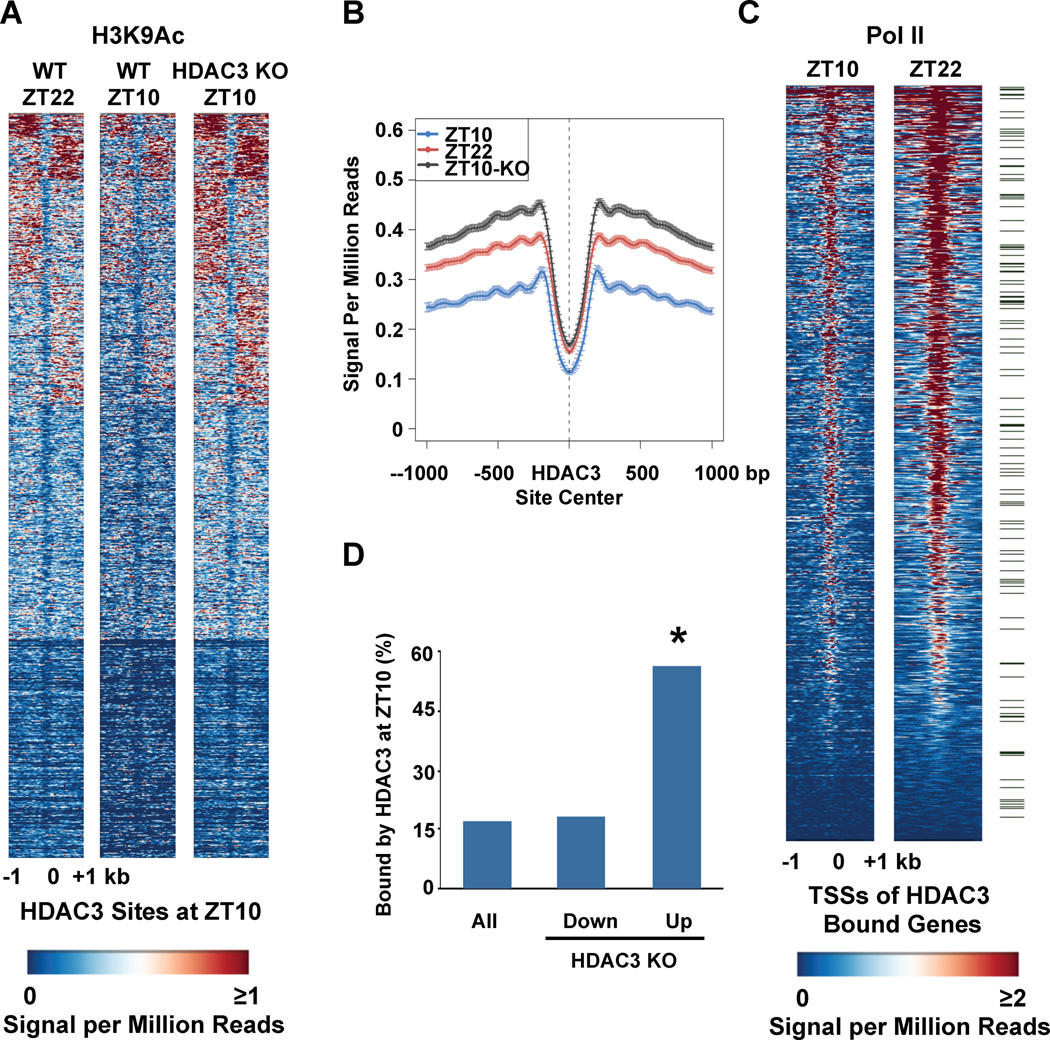

Despite its known role in histone deacetylation and transcriptional repression, HDAC3 recruitment has been reported to be associated with high histone acetylation, RNA polymerase II (Pol II) recruitment, and gene expression in human primary T cells (17). In mouse liver, HDAC3 recruitment at ZT10 was also enriched around active genes (Supp. Fig. 4A), and many of these display circadian expression patterns (18)(Supp. Fig. 4B). Thus HDAC3 may have an important role in transient regulation of these active genes by the circadian clock. Consistent with this hypothesis, we observed decreases in acetylation of histone H3 lysine 9 (H3K9) at ZT10 compared with that at ZT22, the inverse of HDAC3 recruitment to these sites (Figs. 2A and B). Deletion of hepatic HDAC3 by tail vein injection of adeno-associated virus expressing cre-recombinase (AAV-Cre) into adult C57Bl/6 mice homozygous for a floxed HDAC3 allele (HDAC3fl/fl)(Supp. Fig. 1A) led to H3K9 acetylation at ZT10 comparable to that of wild type (WT) mice at ZT22 (Figs. 2A and B). Accompanying the decreased H3K9 acetylation at ZT10 was a decrease in binding of RNA polymerase II (Pol II) at the TSS of genes with HDAC3 binding within 10kb, indicating that they were actively repressed (Fig. 2C). Indeed, the majority of genes whose transcripts were increased 1 week after HDAC3 deletion in liver displayed HDAC3 binding within 10 kb of their TSS in WT mice at ZT10 (Fig. 2D). Thus, genome-wide diurnal recruitment of HDAC3 directs a rhythm of epigenomic modification, Pol II recruitment, and gene expression.

Figure 2. Orchestration of genome-wide rhythms of histone acetylation, Pol II recruitment, and gene expression by HDAC3.

A. Heatmap of the histone H3 lysine 9 acetylation (H3K9Ac) signal in WT liver at ZT22 (left), ZT10 (middle) and ZT10 in liver depleted of HDAC3 (KO) (right) from −1kb to +1kb surrounding the center of all the HDAC3 ZT10 binding sites, ordered by k means clustering of H3K9Ac signal. Each line represents a single HDAC3 binding site and the color scale indicates the H3K9Ac signal per million total reads. HDAC3 depleted liver was removed from HDAC3fl/fl mice 1 week after injection of AAV-Cre as in Methods. B. Average H3K9Ac signal from −1kb to +1kb surrounding the center of all the HDAC3 ZT10 binding sites. The Y axis represents the HDAC3 signal per million total reads. C. Heatmap of Pol II signal at ZT10 (left), and ZT22 (right) from −1kb to +1kb surrounding the TSS of genes with HDAC3 recruitment within 10 kb of the TSS, ordered by strength of Pol II binding at ZT22. Each line represents a single HDAC3 bound gene and the color scale indicates the Pol II signal per million total reads. Green marks denote 130 genes under the Gene Ontology term “Lipid Biosynthetic Process”, listed in Supp. Table 1. D. Genes up-regulated in liver depleted of HDAC3 are significantly enriched for HDAC3 binding at ZT10. Expression arrays of WT and HDAC3 KO liver were performed and analyzed as described in Methods, and the percentage of HDAC3 bound genes in each category was calculated. *p~10−156 based on hypergeometic distribution as in Methods.

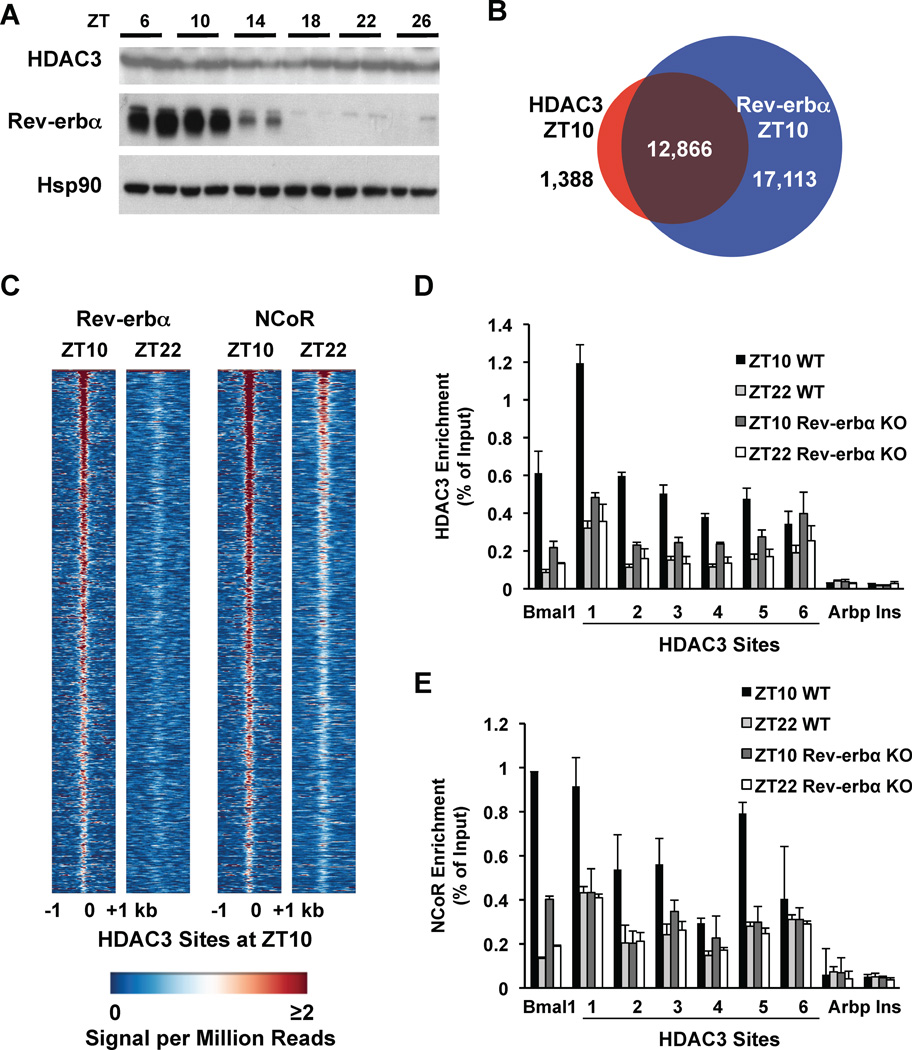

Although HDAC3 recruitment to the genome is diurnal, the abundance of HDAC3 was constant throughout the light/dark cycle (Fig. 3A). HDAC3 enzyme activity requires interaction with nuclear receptor (NR) corepressors (19), and de novo motif analysis of the HDAC3 binding sites revealed the classical motif recognized by a number of NRs (Supp. Fig. 5). The NR Rev-erbα is a transcriptional repressor that is expressed in a circadian manner (20), and the abundance of Rev-erbα protein oscillated in phase with HDAC3 recruitment (Fig. 3A). We used a Rev-erbα-specific antibody (Supp. Fig. 6A) to determine the Rev-erbα binding sites (Supp. Figs. 6B and C). At ZT10, the Rev-erbα binding sites overlapped with the majority of HDAC3 binding sites (Fig. 3B). Furthermore, Rev-erbα bound to the majority of HDAC3 ZT10 sites at ZT10 but not ZT22 (Fig. 3C). The extent of overlap of HDAC3 with Rev-erbα was surprising given that other NRs can interact with corepressors and HDAC3 (21). However, HDAC3 recruitment was diminished at many sites in Rev-erbα KO mice (Fig. 3D), consistent with a critical role for Rev-erbα, although residual HDAC3 binding suggests that other factors also contribute to its recruitment. Rev-erbα recruits HDAC3 via the nuclear receptor corepressor (NCoR) (22, 23). NCoR was recruited to HDAC3 sites with a diurnal rhythm (Fig. 3C), which was attenuated in the Rev-erbα KO mice (Fig. 3E). Moreover, HDAC3 bound together with NCoR as well as Rev-erbα at the majority of ZT10 sites (Supp. Fig 7).

Figure 3. Recruitment of HDAC3 to the genome by Rev-erbα.

A. Immunoblot of HDAC3 and Rev-erbα over a 24h cycle in mouse liver. Hsp90 protein levels are shown as loading control. B. The HDAC3 cistrome at ZT10 largely overlaps with the Rev-erbα cistrome at ZT10. ChIP-Seq with anti-Rev-erbα antibody was performed and analyzed as described in Methods. C. Heatmap of Rev-erbα at ZT10 and ZT22 (left) and of NCoR at ZT10 and ZT22 (right), both at HDAC3 ZT10 sites ordered as in Fig. 1A. Each line represents a single HDAC3 binding site and the color scale indicates the signal per million total reads. D, E. HDAC3 (D) and NCoR (E) recruitment to six binding sites (as in Fig. 1C) were interrogated by ChIP-PCR in liver from mice lacking Rev-erbα. The Bmal1 promoter was used as a positive control (23); regions close to the TSS of the Arbp and Ins genes served as negative controls. Values are mean ± s.e.m. (n=3).

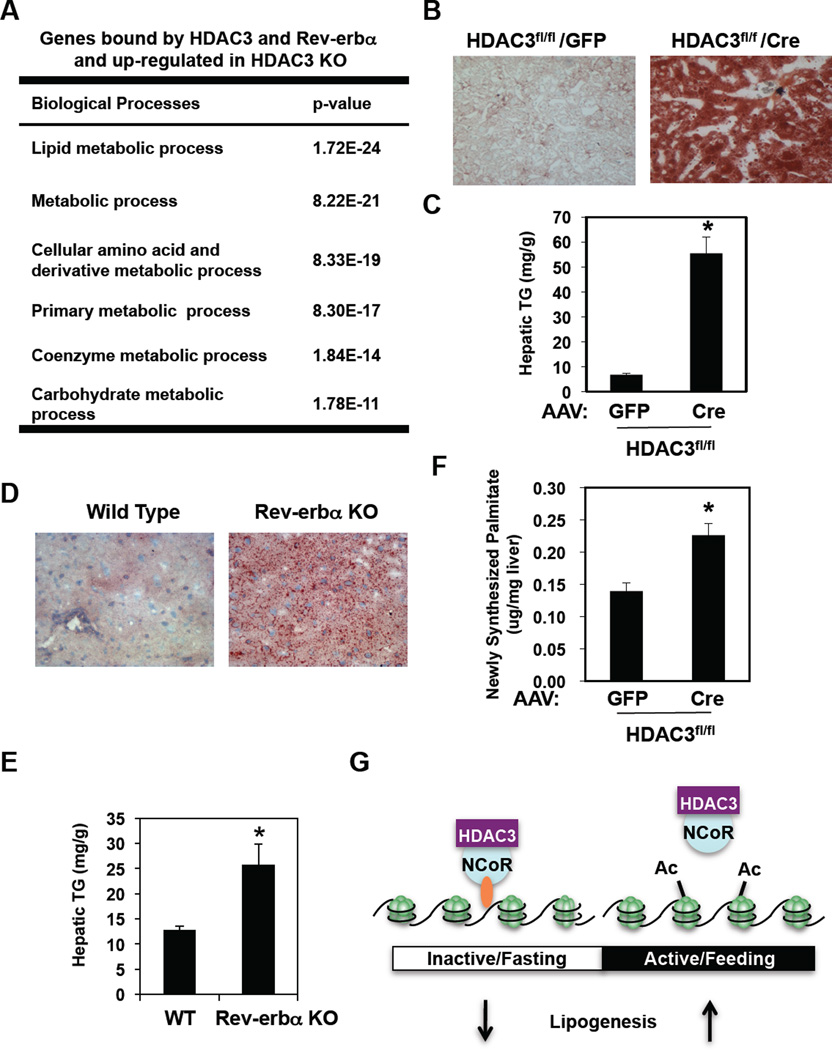

We addressed the biological role of the circadian genomic recruitment of HDAC3 in mouse liver. The set of genes bound by Rev-erbα and HDAC3, and upregulated in livers depleted of HDAC3, was enriched for genes encoding proteins that function in lipid metabolic processes (Fig. 4A). Indeed, in liver of chow fed mice in which HDAC3 was deleted for 2 weeks, Oil Red O staining for neutral lipid was dramatically increased (Fig. 4B) and liver triglyceride content was increased nearly 10-fold (Fig. 4C), with serum transaminase activity increasing only modestly (Supp. Fig. 8A). This was consistent with a fatty liver phenotype of mice depleted of hepatic HDAC3 in utero [(24) and Supp. Fig. 9].

Figure 4. Regulation of hepatic lipid homeostasis by HDAC3.

A. Gene Ontology analysis of the HDAC3 and Rev-erbα-bound genes that were upregulated in liver depleted of HDAC3 was performed as described in Methods. B. Oil Red O staining of liver from 12 week old HDAC3fl/fl mice 2 weeks after tail vein injection of AAV-GFP or AAV-Cre. C. Hepatic triglyceride (TG) levels in mice treated as in “B”. D. Oil Red O staining of livers from 9 week old WT and mice lacking Rev-erbα (Rev-erbα KO). E. Hepatic TG levels in from livers from 9 week old WT and mice lacking Rev-erbα (Rev-erbα KO). Values are mean ± s.e.m. (n=4). *p<0.05 by student’s t-test. F. Hepatic de novo lipogenesis (DNL) in 12 week old HDAC3fl/fl mice 1 week after infection with AAV-Cre or with AAV-GFP. Hepatic DNL is measured as newly synthesized 2H labeled palmitate. Values are mean ± s.e.m. (n=7–8). *p<0.05 by student’s t-test. G. Model depicting the mechanistic links between the daily cycles of Rev-erbα expression, HDAC3 genomic recruitment, epigenomic status, and hepatic lipogenesis.

The majority of genes upregulated in liver depleted of Rev-erbα (25) were bound by HDAC3 as well as Rev-erbα at ZT10 (Supp. Fig. 10). Indeed, chow-fed C57Bl/6 mice genetically lacking Rev-erbα (26) had normal serum transaminase activity (Supp. Fig. 8B), but Oil Red O staining of liver was increased (Fig. 4D) and hepatic triglyceride content was nearly double that of WT mice (Fig. 4E). The relatively modest hepatic steatosis in the Rev-erbα deleted mice likely reflects a role for HDAC3 in mediating effects of other NRs, including Rev-erbβ whose circadian expression pattern is similar to that of Rev-erbα (27), but could also reflect a compensatory effect of Rev-erbα knockout in other tissues. Nevertheless the finding that depletion of either Rev-erbα or HDAC3 led to a fatty liver phenotype supports the conclusion that circadian Rev-erbα recruitment of HDAC3 to lipid metabolic genes plays a critical physiological role.

Rev-erbα and HDAC3 colocalized at 130 lipid biosynthetic genes at ZT10 (Supp. Table 1), and Pol II recruitment increased from ZT10 to ZT22 at the TSS of many of these genes (Fig. 2C), including Fasn, Acaca, and Thrsp, suggesting that they were directly repressed. Assessment of palmitate synthesis after injection of deuterated water revealed increased de novo lipogenesis in mice lacking hepatic HDAC3 (Fig. 4F) or in Rev-erbα KO mice (Supp. Fig. 11), thus revealing a molecular mechanism underlying the observation that hepatic lipogenesis in mice follows a diurnal rhythm (28) that is antiphase to Rev-erbα and HDAC3 recruitment to the mouse genome.

These findings demonstrate the existence of circadian changes in histone acetylation whose dysregulation has the potential to cause major perturbations in normal metabolic function. Each day, low concentrations of Rev-erbα lead to reduced HDAC3 association with the liver genome while the organism is active and feeding, altering the epigenome to permit lipid synthesis and accumulation until abundance of Rev-erbα increases HDAC3 recruitment to liver metabolic genes and halts the lipid build-up (Fig. 4G). When either Rev-erbα or HDAC3 is depleted, this cycle does not occur and fatty liver ensues. Misalignment of fasting/feeding and sleep/wake cycles with endogenous circadian cycles could disrupt the rhythm of HDAC3 association with target genes and contribute to the fatty liver observed in rotating shift workers (29) as well as people with genetic variants of molecular clock genes (30).

Acknowledgments

We thank B. Vennström for providing Rev-erba knockout mice, M. Brown and members of the Lazar lab for helpful discussions, D. Zhuo for technical assistance, the Penn IDOM Metabolism Resource (J. Millar) for help with de novo lipogenesis experiments, the Functional Genomics Core (J. Schug and K. Kaestner) and the Viral Vector Core (J. Johnston) of the Penn Diabetes Endocrinology Research Center (NIH DK19525) for deep sequencing and virus preparation, the Morphology Core (J. Katz and G. Swain) (NIH DK49210) for tissue preparation and staining, and the Penn Bioinformatics Core (J. Tobias) and Microarray Core (D. Baldwin) for gene expression analysis. Supported by NIH DK45586, DK43806, and RC1DK08623 (to MAL) and NIH HG4069 (to XSL).

Footnotes

ChIP-seq and microarray data have been deposited in GEO (GSE25937).

REFERENCES

- 1.Green CB, Takahashi JS, Bass J. Cell. 2008 Sep 5;134:728. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.08.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maury E, Ramsey KM, Bass J. Circ Res. 2010 Feb 19;106:447. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.208355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scheer FA, Hilton MF, Mantzoros CS, Shea SA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009 Mar 17;106:4453. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808180106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pietroiusti A, et al. Occup Environ Med. 2010 Jan;67:54. doi: 10.1136/oem.2009.046797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Bacquer D, et al. Int J Epidemiol. 2009 Jun;38:848. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyn360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marcheva B, et al. Nature. 2010 Jul 29;466:627. doi: 10.1038/nature09253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Turek FW, et al. Science. 2005 May 13;308:1043. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lamia KA, Storch KF, Weitz CJ. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008 Sep 30;105:15172. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806717105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eckel-Mahan K, Sassone-Corsi P. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009 May;16:462. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rudic RD, et al. PLoS Biol. 2004 Nov;2:e377. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Panda S, et al. Cell. 2002 May 3;109:307. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00722-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Etchegaray JP, Lee C, Wade PA, Reppert SM. Nature. 2003 Jan 9;421:177. doi: 10.1038/nature01314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Doi M, Hirayama J, Sassone-Corsi P. Cell. 2006 May 5;125:497. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Strahl BD, Allis CD. Nature. 2000 Jan 6;403:41. doi: 10.1038/47412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alenghat T, et al. Nature. 2008 Dec 18;456:997. doi: 10.1038/nature07541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Damiola F, et al. Genes Dev. 2000 Dec 1;14:2950. doi: 10.1101/gad.183500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang Z, et al. Cell. 2009 Sep 4;138:1019. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hughes ME, et al. PLoS Genet. 2009 Apr;5:e1000442. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guenther MG, Barak O, Lazar MA. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:6091. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.18.6091-6101.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Preitner N, et al. Cell. 2002 Jul 26;110:251. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00825-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goodson M, Jonas BA, Privalsky MA. Nucl Recept Signal. 2005;3:e003. doi: 10.1621/nrs.03003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zamir I, et al. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1996;16:5458. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.10.5458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yin L, Lazar MA. Mol Endocrinol. 2005 Jun;19:1452. doi: 10.1210/me.2005-0057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Knutson SK, et al. EMBO J. 2008 Apr 9;27:1017. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kornmann B, Schaad O, Bujard H, Takahashi JS, Schibler U. PLoS Biol. 2007 Feb;5:e34. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chomez P, et al. Development. 2000 Apr;127:1489. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.7.1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu AC, et al. PLoS Genet. 2008 Feb;4:e1000023. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hems DA, Rath EA, Verrinder TR. Biochem J. 1975 Aug;150:167. doi: 10.1042/bj1500167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brunt EM. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010 Apr;7:195. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2010.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sookoian S, Castano G, Gemma C, Gianotti TF, Pirola CJ. World J Gastroenterol. 2007 Aug 21;13:4242. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i31.4242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]